Abstract

Purpose:

Evaluate differences in Medicare reimbursements between men and women ophthalmologists between 2013 and 2019.

Design:

Retrospective cohort study

Subjects:

Ophthalmologists between 2013 and 2019 receiving Medicare reimbursements

Methods:

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Physician and Other Supplier Public Use File was used to determine total reimbursements and number of services submitted by ophthalmologists between 2013 and 2019. Reimbursements were standardized to account for geographic differences in Medicare reimbursement per service. Data from the American Community Survey (ACS) were used to determine zip-code-level socioeconomic characteristics (unemployment, poverty, income, and education) for the location of each physician’s practice. A multivariable linear regression model was used to evaluate differences in annual reimbursements by gender, accounting for calendar year, years of experience, total number of services, ACS zip-code data, and proportion of procedural services.

Main Outcome Measures:

Annual Medicare reimbursement, utilization of billing codes (e.g., outpatient office visits and eye examinations, diagnostic testing, laser and surgery)

Results:

Among 20,281 ophthalmologists who received Medicare reimbursements between 2013 and 2019, 15,451 (76%) were men. The most common billing codes submitted were for outpatient visits and eye examinations (13.8 million charges/year), diagnostic imaging of the retina (5.6 million charges/year), intravitreal injections (2.9 million charges/year) and removal of cataract with insertion of lens (2.4 million charges/year). Compared to men, women ophthalmologists received lower median annual reimbursements ($94,734.21, IQR 30,944.52–195,701.70 for women vs. $194,176.90, IQR 76,380.76–355,790.80 for men, p<0.001) and billed for a lower annual number of services (1,228, IQR 454–2,433 vs. 2,259, IQR 996–4,075, respectively p<0.001). After adjustment for covariates, women ophthalmologists billed for 1015 fewer services (95% confidence interval 1001–1029, p<0.001), and received $20,209.12 less in reimbursements than men (95% confidence interval −21,717.57 to −18,700.66, p<0.001).

Conclusions:

Women ophthalmologists billed for a lower number of services and received less in reimbursement from Medicare than men over time and across all categories of billing codes. Disparities persisted after controlling for physician and practice characteristics.

Keywords: Disparities, women ophthalmologists, Medicare, CMS, reimbursements

Precis

Women ophthalmologists billed for a lower number of services and received less in reimbursement from Medicare than men over time and across most categories of billing codes. Disparities in reimbursement persisted after controlling for physician and practice characteristics.

Introduction

The gender-based pay gap in medicine has been well-documented across all specialties, including in ophthalmology. These disparities span careers and subspecialties. In medical school, letters of recommendation for ophthalmology residency have been reported to have gender-based differences, with more emphasis on female applicants’ work ethic, rather than ability or talent compared to male applicants.1 In residency, gender-based differences in case volumes have been reported with female residents performing fewer cataract operations and total procedures compared to their male counterparts.2 After completing training, gender-based disparities in salary, case volume, and academic contributions persist.3–10 Women ophthalmologists are reported to earn significantly less in their first year of clinical practice, perform fewer cataract surgeries, and receive lower NIH funding compared to men.3,6,7,9 Some studies have also reported gender differences in Medicare reimbursements amongst ophthalmologists, even after controlling for physician experience.5,6

While few prior studies have evaluated gender differences in Medicare reimbursements in ophthalmology5,6, none have comprehensively evaluated differences in reimbursement and billing patterns by service category or procedure type. Furthermore, no prior study has accounted for the proportion of procedural services and physician practice zip-code socioeconomic indicators in assessing gender-based differences in total reimbursements. Finally, prior studies have included a short timeframe to study differences in Medicare reimbursements (e.g., 2–4 years) or do not study geographic variation in reimbursements.

To address these limitations, we designed a study to evaluate gender differences in Medicare billing patterns and total reimbursement between men and women ophthalmologists between 2013 and 2019, accounting for potential confounders including physician practice characteristics and zip-code socioeconomic indicators.

Methods

Physician reimbursement and billing data were extracted from the publicly available CMS Physician and Other Supplier Public Use Files (PUF) between 2013 and 2019. These data files include information on services provided to Medicare Part B beneficiaries by physicians and other healthcare providers. Each provider is assigned a unique National Provider Identifier (NPI), and all services are identified using Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes. Providers in this file were included if they were MD or DO ophthalmologists between 2013 and 2019. Ophthalmologist gender was self-reported and coded as M or F, referred to in this study as “man” or “woman.” Data on year of graduation was derived from the National Downloadable File, linked to the Physician and Other Supplier PUF using NPIs and was available for 76% of ophthalmologists. Services were categorized as procedural and non-procedural (non-procedural services were defined as those having HCPCS codes 99201–99499, 92002, 92004, 92012, 92014, and procedural services were defined as all other HCPCS codes). In addition, billing codes were further grouped into the following categories based on the type of service provided: outpatient eye examination or office visit, diagnostic imaging and testing, inpatient, emergency department, or nursing facility encounter, cataract surgery, injection, laser procedure, extraorbital procedural (strabismus or oculoplastics), vitreoretinal surgery, glaucoma surgery, and cornea or ocular surface procedure surgery (Table 1). Services with HCPCS codes beginning in J or Q were excluded. Provider zip-codes were converted to zip-code tabulation areas (ZCTA) in order to identify socioeconomic characteristics of each ophthalmologist’s practice location using data from the American Community Survey (ACS).11 Socioeconomic characteristics used in this study include zip-code-level median household income, percent unemployment, percent poverty and percent of the population with no college education.12 The study did not require institutional review board review as all data are publicly available and so do not constitute human subjects research.

Table 1:

Categories of HCPCS codes charged by ophthalmologists to Medicare between 2013 and 2019.

| Billing code category | HCPCS codes |

|---|---|

| Outpatient eye examination or office visit | 92014, 92012, 92004, 99213, 99214, 99204, 99212, 99203, 92002, 92225, 92020, 99215, 92060, 99205, 99286, 99202, 99211, 92071, 92100, 92140, 99354, 92283, 92226, 99201 |

| Diagnostic imaging and testing | 92083, 92134, 92133, 92250, 92136, 76514, 76519, 76510, 76511, 76513, 76516, 92235, 92285, 76512, 92025, 92082, 92081, 92132, 92275, 95930, 92240, 92242, 92145, 92287, 92273, 93886, 93892, 93890, 92284, 0509T |

| Inpatient, emergency department or nursing facility encounter | 99223, 99222, 99221, 99308, 99283, 99305, 99309, 99232, 99284, 99306, 99231, 99304, 99307, 99233 |

| Cataract surgery | 66984, 66982, 66986, 66711, 66825 |

| Injection | 67028, 64612, 67515, 68200 |

| Laser procedure | 66821, 65855, 67228, 67210, 66761, 67145, 67040, 66710, 67031, 67220, 67039, 66762 |

| Extraorbital procedure (oculoplastics and strabismus) | 67820, 68761, 15823, 67840, 67904, 68840, 67917, 68810, 68801, 67800, 67900, 67810, 14060, 67924, 68815, 11440, 67950, 67966, 15260, 67875, 68720, 67903, 68760, 67908, 31231, 67311, 15732, 67825, 67911, 68700, 11441, 67314, 67921, 67335, 14040, 37609, 15004, 67850, 11100, 68040, 67916, 67914, 68440, 67961 |

| Glaucoma surgery | 0191T, 66180, 66170, 65820, 66172, 66183, 0376T, 0449T, 0474T, 65850, 0192T |

| Vitreoretinal surgery | 67042, 67108, 67036, 67041, 67113, 67105, 67221 |

| Cornea or ocular surface procedure | 65756, 65778, 66250, 65210, 67255, 65222, 65400, 65205, 68320, 68326, 65435, 65430, 65757, 65755, 65426, 65780, 68110, 68530, 65772 |

The following outcomes were measured in this study: total number of services and total annual reimbursements (representing the amount paid by Medicare after geographic standardization to account for differences in payment rates for individual services across geographic areas).13

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA (Version 16.1, College Station, TX). Medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) were calculated for total number of services and total CMS reimbursements by year and gender. Median values were compared using Wilcoxon Rank Sum Tests. Multivariable linear regression models were used to compare total annual reimbursement (adjusted for reimbursement year, total number of services, years of experience, ACS data, and proportion of reimbursement from procedural services) and total annual number of services (adjusted for year, total number of services, years of experience, ACS data and proportion of reimbursement from procedural services). P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Among 20,281 ophthalmologists who received Medicare reimbursements between 2013 and 2019, 15,451 (76%) were men. The most common billing codes submitted were for established patient eye examinations (HCPCS codes 92012, 92014; 13.8 million charges/year), diagnostic imaging of the retina (HCPCS code 92134; 5.6 million charges/year), intravitreal injections (HCPCS code 67028; 2.9 million charges/year) and cataract surgery (HCPCS codes 66982, 66984; 2.4 million charges/year). The states with the highest number of ophthalmologists were California (2,345 ophthalmologists, 11.3%), New York (1,851 ophthalmologists, 8.9%) and Florida (1,433 ophthalmologists, 6.9%). The states with the lowest number of ophthalmologists were Wyoming (13 ophthalmologists, 0.06%), Arkansas (28 ophthalmologists, 0.14%) and North Dakota (41 ophthalmologists, 0.2%).

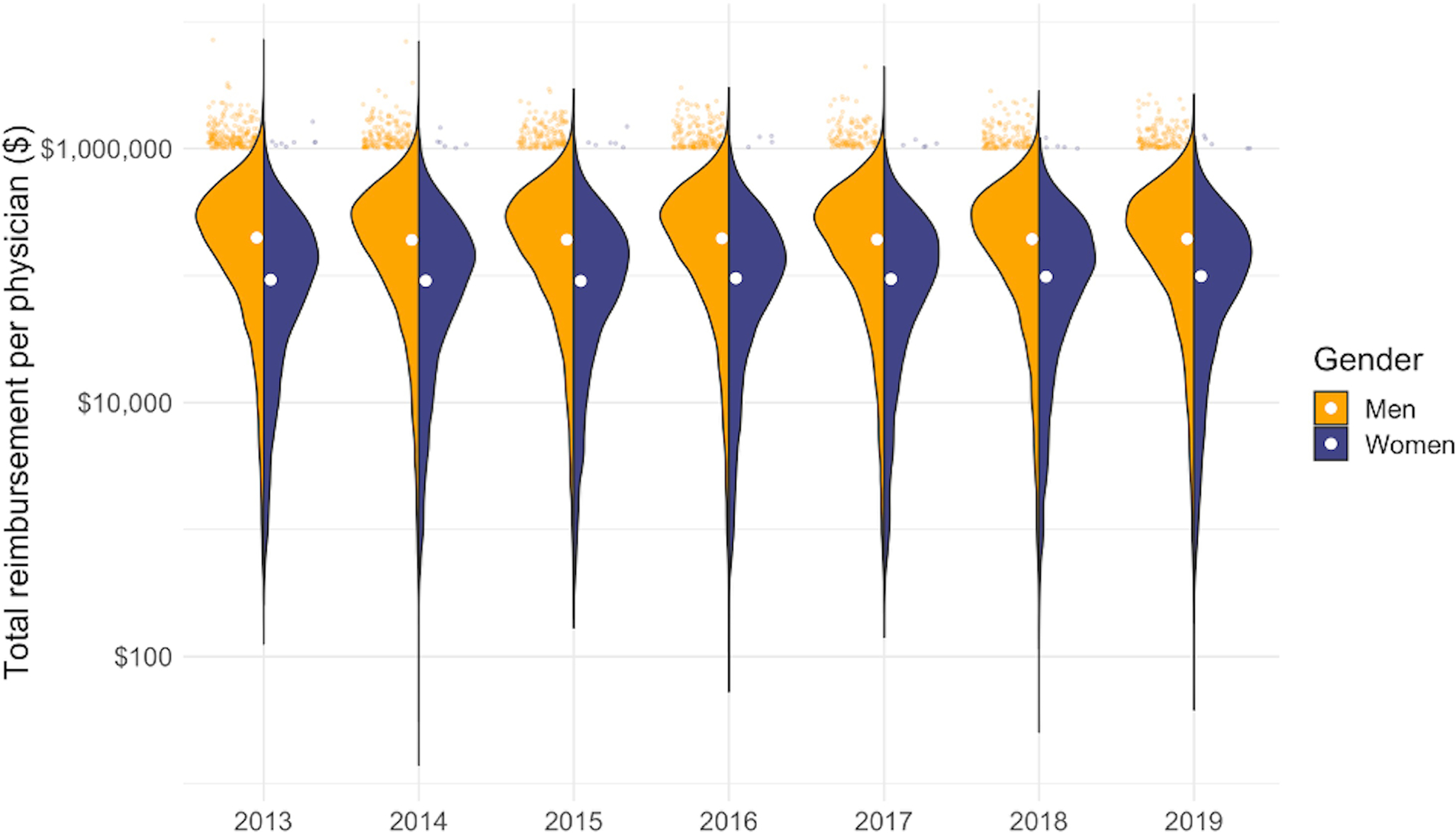

Compared to men, women ophthalmologists had fewer median years of experience (12, IQR 10–22 for women vs. 21, IQR 11–30 for men, p<0.001), billed for a lower median annual number of services (1,228, IQR 454–2,433 for women vs. 2,259, IQR 996–4,075 for men, respectively p<0.001), had a lower annual number of unique billing codes (12, IQR 8–15 for women vs. 14, IQR 10–18 for men, p<0.001), and a lower percentage of procedural services (48.1%, IQR 29.2–60.3 for women vs. 54.6%, IQR 38.5–66.1 for men, p<0.001). Women ophthalmologists received less in median annual reimbursement than men ($94,734.21, IQR 30,944.52–195,701.70 for women vs. $194,176.90, IQR 78,380.76–355,790.80 for men, p<0.001). While median annual reimbursement to women increased among women between 2013 and 2019, from $92,589.34 (IQR 30,073.89–196,450.90) to $99,137.19 (IQR 31,724.60–202,459.90), it remained consistently lower compared to men for all years. There was a small concomitant decrease in annual reimbursements to men from $198,675.00 (IQR 81,550.36–367,461.90) to $194,923.50 (IQR 78,684.22–355,689.40, (Figure 1) during the study period. Across all seven years, the total median reimbursement to women was $454,104.20 (IQR 105,184.60–1,087,882.00) or 43% of the total median reimbursement to men ($1,058,862.00, IQR 322,438.80–2,184,176.00). While 76% of ophthalmologists in our sample were men, they comprised 94% of ophthalmologists with annual reimbursements in the 90th percentile and above, and 97% of ophthalmologists with annual reimbursements in the 99th percentile and above.

Figure 1:

Distribution of annual reimbursements among men and women ophthalmologists by year

Footnote: Split violin plot showing the distribution of total reimbursement for each year and gender. The scatter plots at the top display physicians who are reimbursed in the top 1%. The white circles represent median reimbursement for that year and gender.

In a multivariable linear regression model adjusting for years of experience, number of services, service year, percent procedural services, and socioeconomic characteristics in physician location of practice, women billed for 1,015 fewer services annually than men (95% confidence interval 1001–1029, p<0.001, Table 2). Women also received $20,209.12 less than men in total annual reimbursement (95% confidence interval 18,700.66–21,717.57, p <0.001, Table 3), in a model adjusted for number of services, years of experience, service year, percent procedural services, and socioeconomic characteristics in physician location of practice.

Table 2:

Results of a multivariable linear regression model comparing annual number of services by gender, adjusted for physician and practice characteristics

| Predictor | Number of services | 95% confidence interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 0 (Ref) | - | - |

| Female | −1,015 | 1,001, 1,029 | <0.001 |

| Years of experience | 24 | 23, 24 | <0.001 |

| Service year | 6 | 3, 9 | <0.001 |

| Procedural codes (%) | 58 | 58, 59 | <0.001 |

| Socioeconomic characteristics of practice location | |||

| Mean household income ($) | 0 | 0, 0 | <0.001 |

| Unemployment (%) | 30 | 27, 32 | <0.001 |

| Poverty (%) | −24 | −25, −23 | <0.001 |

| No college education (%) | 19 | 19, 19 | <0.001 |

Table 3:

Results of a multivariable linear regression model comparing annual reimbursement by gender, adjusted for physician and practice characteristics

| Predictor | Reimbursement ($) | 95% confidence interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 0 (Ref) | - | - |

| Female | −20,209.12 | −21,717.57, −18,700.66 | <0.001 |

| Total number of services | 61.42 | 61.21, 61.64 | <0.001 |

| Years of experience | 320.93 | 267.49, 374.36 | <0.001 |

| Service year | −4,261.60 | −4,615.51, −3,907.69 | <0.001 |

| Procedural codes (%) | 2,036.69 | 2,004.99, 2,068.39 | <0.001 |

| Socioeconomic characteristics of practice location | |||

| Mean household income ($) | −0.13 | −0.17, −0.09 | <0.001 |

| Unemployment (%) | −1,415.63 | −1,684.49, −1,146.77 | <0.001 |

| Poverty (%) | −497.92 | −599.51, −396.34 | <0.001 |

| No college education (%) | 673.69 | 624.13, 723.24 | <0.001 |

Women ophthalmologists received less in Medicare reimbursements in most US states, (Figure 2), with the exception of South Dakota, where women received a median of $346,199.60 in annual reimbursements (IQR 255,522.00–579,348.10) compared to $288,435.10 (IQR 110,748.10–452,319.90) received by men. The states with the greatest differences in median annual reimbursements were Delaware, where women ophthalmologists received $205,233.20 less in median annual reimbursements than men, and Alabama, where women received $173,155.90 less in median annual reimbursements than men. In New Mexico and Minnesota, there were no statistically significant differences in median annual reimbursements by gender.

Figure 2:

Gender differences in median annual reimbursements by state

Footnote: States with less than 50 ophthalmologists (Wyoming, Alaska, North Dakota, and Vermont) were excluded from this figure. The more orange the state is colored, the greater the median reimbursement for men is compared to median reimbursement for women.

Men ophthalmologists were reimbursed more than women ophthalmologists in all billing code categories (Figure 3). The greatest disparities were seen in injections, with women ophthalmologists receiving $15,418.26 (46.3%) less in median annual reimbursements than men (p<0.001), outpatient visits and eye examinations, ($37,270.56 [43.2%] less; p<0.001), and cataract surgery ($32,197.31 [42.7%] less; p<0.001). The smallest disparity was seen in extraorbital and strabismus procedures, with women earning $497.84 (10.2%) less in reimbursement than men (p<0.001) (Figure 3). Similarly, men ophthalmologists charged for a greater annual number of services in all billing code categories compared to women ophthalmologists (Figure 4). The greatest difference in annual number of services was seen in injections, with women claiming 195 (46.9%) fewer services than men (p<0.001), cataract surgeries (66 [43.4%] fewer services; p<0.001), and outpatient visits and eye examinations (498 [40.4%] fewer services; p<0.001). The smallest difference was seen inpatient encounters, with women claiming 3 (11.5%) fewer services than men (p=0.003). Gender differences in the number of services for eye examinations and evaluation and management codes for outpatient visits were also evaluated. The greatest gender differences were found in the most commonly used codes for both new and established patient visits: 92004, 99204, 92014, 99213, with women ophthalmologists billing for fewer services (Figures S1–S2, available at https://www.aaojournal.org).

Figure 3:

Distribution of annual reimbursements among men and women ophthalmologists by billing code category

Split violin plot showing the distribution of total reimbursement for each billing code category and gender. The scatter plots at the top display physicians who are reimbursed in the top 1%. The white circles represent median reimbursement for that year and billing code category.

Figure 4:

Distribution of annual number of services among men and women ophthalmologists by billing code category

Footnote: Split violin plot showing the distribution of total number of services for each billing code category and gender. The scatter plots at the top display physicians with the number of services billed in the top 1%. The white circles represent median number of services for that year and billing code category.

In separate multivariable linear regression models evaluating differences in reimbursement for each billing code category, women ophthalmologists received lower reimbursements in most categories after controlling for number of services, years of experience, year of service, and the ACS socioeconomic variables (Table 4). The greatest difference was seen in cataract surgeries, from which women received $32,855.20 less in annual reimbursements on average than men (95% CI −34,707.03 to −31,003.37). Women received higher reimbursements than men when considering only diagnostic imaging and testing codes ($1,247.92 more in reimbursements vs. men, 95% CI 923.99 to 1,571.85, p<0.001), and no significant differences in reimbursements were seen in the glaucoma and cornea surgery categories.

Table 4.

Results of Multivariate Linear Regression Models Comparing Annual Reimbursement by Sex in Each Billing Code Category

| Billing Code Category | Estimate ($) | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outpatient eye examination or office visit | −6305.93 | −6722.62 to −5889.24 | <0.001 |

| Diagnostic imaging and testing | 1247.92 | 923.99–1571.85 | <0.001 |

| Cataract surgery | −32 855.20 | −34 707.03 to −31 003.37 | <0.001 |

| Injection | −263.65 | −486.86 to −40.43 | 0.02 |

| Laser procedure | −2132.30 | −2454.08 to −1810.52 | <0.001 |

| Extraorbital procedure (oculoplastics and strabismus) | −1998.83 | −2744.69 to −1252.97 | <0.001 |

| Glaucoma surgery | 750.11 | −174.41 to 1674.64 | 0.11 |

| Vitreoretinal surgery | −4733.43 | −6093.74 to −3373.13 | <0.001 |

| Cornea or ocular surface procedure | 2852.34 | −5853.79 to 149.11 | 0.06 |

All models were adjusted for year of service, years of experience, number of services, and socioeconomic characteristics.

To confirm the finding that differences in reimbursement persisted after controlling for number of services, differences in reimbursement per service were evaluated for the following commonly billed codes: new patient comprehensive eye examinations (HCPCS code 92004) and cataract surgeries (HCPCS code 66984). For each eye examination, women ophthalmologists were reimbursed a median of $100.45 (IQR 93.19–106.77), while men received $100.53 (IQR 94.56–106.26; p=0.003). In a regression model evaluating the average difference in reimbursement per code in a given year and zip-code, women received $0.47 (95% CI 0.28, 0.66) less in reimbursement on average per eye exam code (p<0.001). Conversely, women were reimbursed more per cataract surgery, receiving a median of $506.40 (IQR 491.69–513.21) compared to $503.29 (IQR 471.99–511.29) received by men (p<0.001). In a given year and zip-code, women received $14.23 (95% CI 12.20, 16.27) more in reimbursement, on average, for each cataract surgery (p<0.001). To evaluate differences in reimbursement per service for all billing codes, a mixed effects regression model was carried out, grouped by HCPCS code, billing year and zip-code. On average, women received $0.23 (95% CI 0.04, 0.42) less in reimbursement than men for a given HCPCS code, in a given year and geographic location (p=0.02).

Discussion

Medicare billing patterns varied by gender, with women billing for a fewer number of services using a lower number of unique billing codes, and subsequently received lower annual reimbursements than men. These disparities in billing patterns persisted, even after controlling for physician and practice characteristics and varied in magnitude across the United States. Importantly, we found that men accounted for a higher proportion of top earners compared to their share of the study population.

Our finding that women billed for a fewer number of services and received less in reimbursement is consistent with previous literature, both in ophthalmology and in other specialties.5,6,14,15 There are many possible reasons for this observed disparity. For one, we found that median number of outpatient visits and outpatient service reimbursements for women are less than for men. Jefferson et al. found that there is some evidence that female physicians use more partnership-building behaviors during patient visits and spend, on average, 2.24 minutes longer with patients per consultation than their male colleagues, though these findings are limited by the quality of studies included in their meta-analysis.16 Similarly, Ganguli et al. found that female primary care physicians spend 16% more time with a patient, compared to their male counterparts.17 This finding remained significant after controlling for physician experience, indicating that women ophthalmologists, regardless of experience, may be spending more time with each patient during outpatient visits, thus seeing fewer patients.

Importantly, we found that differences in reimbursement persisted after controlling for the number of services. To confirm this finding, we carried out additional analyses evaluating differences in reimbursement per service. While women received more per service for some services, such as cataract surgeries, overall, we found that women were reimbursed less on average per service in a given year and geographic location. These findings suggest that the number of services billed is not the only driver of differences in total reimbursement, and that while Medicare itself does not discriminate by gender in reimbursement per service, other differences in billing patterns such as billing code complexity and patient co-insurance, as well as practice setting, may contribute to differences in reimbursement.

We found significant unadjusted gender differences in all billing code categories. In adjusted models where women receive more in reimbursement than men (e.g., diagnostic imaging, cornea or ocular surface procedures), the differences in reimbursement were small, ranging from $1,247 to $2,852. In domains where men receive more reimbursement than women, the differences were larger, ranging from $263 to $32,855. We also found significant disparity between men and women ophthalmologists’ billing and reimbursement of intravitreal injections and vitreoretinal surgery. Amongst the retina subspecialty, only 20% of practice retina specialists are women, though this number is expected to increase, given that 25% of vitreoretinal surgical fellowship applicants from 2014–2018 were women.8,18–20 It is possible that this observed difference in reimbursement is because intravitreal injections and vitreoretinal surgery are predominantly provided retina specialists who are predominantly men.

Among HCPCS codes for outpatient visits and eye examinations, the association between physician gender and billing code complexity was difficult to assess, given that eye examination and outpatient visit codes are reimbursed differently in different geographic regions, and that not all ophthalmologists in our sample used all of these codes. Other variables contributing to variations in the use of eye examination and outpatient visit codes are unknown and could not be accounted for.

We saw considerable geographic variation in gender disparities in the difference of mean total Medicare reimbursement, ranging from North Dakota where the median reimbursement for women is $54,764 more than men to Delaware where the median reimbursement for women is $205,233 less than men. This wide range of differences in reimbursement between men and women physicians in different states likely represents the cumulative effects of physician density, gender perceptions, and government or health system policies. More research to understand what is driving greater disparity in certain states may help us identify possible solutions to increase payment parity among men and women ophthalmologists.

We found that while 76% of ophthalmologists in our sample were men, 96% of ophthalmologists who are reimbursed in the top 1% are men. This proportional difference may be partially explained by experience; while physicians entering ophthalmology have reached gender parity, there are a higher proportion of male ophthalmologists among physicians with more experience.7 Physicians with more experience have stronger referral networks and more clinical volume. However, previous studies have shown that female ophthalmologists earn significantly less than their male colleagues from their first year of practice, even after controlling for demographic, educational, and practice type variables.3 There are several theories for why these disparities exist, including less effective salary negotiation and implicit gender biases of lower competence, among others.21 These biases and disparities lead to compounding effects with time, which may explain our finding that a disproportionate number of men colleagues are “top-earners.”

Our study has several strengths. We utilized a large and comprehensive database to study differences in reimbursement by service category and accounted for several important patient and practice characteristics. However, it is also subject to some limitations. First, our data do not include any other sources of physician income, including reimbursement from private insurers or out-of-pocket costs. These other data are not public and cannot be included in this analysis. Furthermore, while our data include some physician and practice characteristics such as practice zip-code and years of experience, other characteristics, such as rates of co-insurance, surgical referral patterns, access to parental leave, practice in an urban area, and physician race and age, were not available. Therefore, other sources of disparities in reimbursement remain unknown. Future research in this area with a more comprehensive dataset may lead to more nuanced findings, revealing potential policies and solutions for the observed disparities in Medicare reimbursement.

Our study demonstrates that between 2013 and 2019, women ophthalmologists billed Medicare for fewer services and received lower reimbursement than men over time and across most categories of billing codes. On average, women ophthalmologists make 43% of what men make which after extrapolation equates to a disparity of $3.5 million over a 40-year-career. These disparities in reimbursement persisted even after controlling for physician and practice characteristics. Given that Medicare does not discriminate by gender in its reimbursement of ophthalmologist services, other sources of reimbursement disparities likely exist but remain unknown. More research is required to elucidate the impact of intersectionality with other physician and practice characteristics and the possible effect of mitigating policies on these disparities.

Supplementary Material

Financial support:

This work was supported in part by the NIH K23 Career Development Award (K23EY032634) (NZ) and Research to Prevent Blindness Career Development Award (NZ). The funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: MVB has consulted with Carl Zeiss Meditec and Topcon and has received lecture fees from Carl Zeiss Meditec.

Meeting presentation: The Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Annual Meeting, Denver, CO, May 3rd, 2022.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lin F, Oh SK, Gordon LK, Pineles SL, Rosenberg JB, Tsui I. Gender-based differences in letters of recommendation written for ophthalmology residency applicants. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):476. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1910-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gong D, Winn BJ, Beal CJ, et al. Gender Differences in Case Volume Among Ophthalmology Residents. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(9):1015–1020. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.2427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jia JS, Lazzaro A, Lidder AK, et al. Gender Compensation Gap for Ophthalmologists in the First Year of Clinical Practice. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(7):971–980. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weeks WB, Wallace AE. Gender Differences in Ophthalmologists’ Annual Incomes. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(9):1696–1701.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad S, Ramulu P, Akpek E, Deobhakta A, Klawe J. Gender-Specific Trends in Ophthalmologist Medicare Collections. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2020;214:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy AK, Bounds GW, Bakri SJ, et al. Differences in Clinical Activity and Medicare Payments for Female vs Male Ophthalmologists. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(3):205. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.5399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng PW, Ahluwalia A, Adelman RA, Chow JH. Gender Differences in Surgical Volume among Cataract Surgeons. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(5):795–796. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.09.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reyes-Capo DP, Yannuzzi NA, Chan RVP, Murray TG, Berrocal AM, Sridhar J. GENDER DIFFERENCES IN SELF-REPORTED PROCEDURAL VOLUME AMONG VITREORETINAL FELLOWS. Retina. 2021;41(4):867–871. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Svider PF, D’Aguillo CM, White PE, et al. Gender Differences in Successful National Institutes of Health Funding in Ophthalmology. Journal of Surgical Education. 2014;71(5):680–688. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalavar M, Watane A, Balaji N, et al. Authorship Gender Composition in the Ophthalmology Literature from 2015 to 2019. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(4):617–619. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.08.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.UDS Mapper. Zip Code to ZCTA Crosswalk. https://udsmapper.org/zip-code-to-zcta-crosswalk/

- 12.Berkowitz SA, Traore CY, Singer DE, Atlas SJ. Evaluating Area-Based Socioeconomic Status Indicators for Monitoring Disparities within Health Care Systems: Results from a Primary Care Network. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(2):398–417. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Physician & Other Practitioners - by Provider and Service Data Dictionary. https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-physician-other-practitioners/medicare-physician-other-practitioners-by-provider-and-service

- 14.Raber I, Al Rifai M, McCarthy CP, et al. Gender Differences in Medicare Payments Among Cardiologists. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(12):1432. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.3385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felfeli T, Canizares M, Jin YP, Buys YM. Pay Gap among Female and Male Ophthalmologists Compared with Other Specialties. Ophthalmology. 2022;129(1):111–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jefferson L, Bloor K, Birks Y, Hewitt C, Bland M. Effect of physicians’ gender on communication and consultation length: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2013;18(4):242–248. doi: 10.1177/1355819613486465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganguli I, Sheridan B, Gray J, Chernew M, Rosenthal MB, Neprash H. Physician Work Hours and the Gender Pay Gap — Evidence from Primary Care. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1349–1357. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa2013804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel SH, Truong T, Tsui I, Moon JY, Rosenberg JB. Gender of Presenters at Ophthalmology Conferences Between 2015 and 2017. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2020;213:120–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sridhar J, Kuriyan AE, Yonekawa Y, et al. Representation of Women in Vitreoretinal Meeting Faculty Roles from 2015 through 2019. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;221:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yannuzzi NA, Smith L, Yadegari D, et al. ANALYSIS OF THE VITREORETINAL SURGICAL FELLOWSHIP APPLICANT POOL: Publication Misrepresentations and Predictors of Future Academic Output. Retina. 2020;40(10):2026–2033. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanfey H, Crandall M, Shaughnessy E, et al. Strategies for Identifying and Closing the Gender Salary Gap in Surgery. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2017;225(2):333–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen YW, Westfal ML, Chang DC, Kelleher CM. Underemployment of Female Surgeons? Annals of Surgery. 2021;273(2):197–201. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.