To the Editor: In a prospective cohort study involving health care workers that was described previously,1 we evaluated the humoral response and vaccine effectiveness of a fourth dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine (Pfizer–BioNTech) against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) during a 6-month follow-up period in which omicron (mostly BA.1 and BA.2) was the predominant variant in Israel.2 The absence of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection was verified by SARS-CoV-2 testing and serologic follow-up testing (see Table S1 and the Supplementary Methods in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org). The humoral response (as assessed by the measurement of IgG and neutralizing antibodies) after receipt of the fourth vaccine dose was compared with that after receipt of the second and third doses. Vaccine effectiveness was assessed by comparing infection rates among participants who had received a fourth vaccine dose during various time periods (days 7 through 35, days 36 through 102, or days 103 through 181 after receipt of the fourth dose) with infection rates among those who had received three doses. Participants were to have received the third vaccine dose at least 4 months earlier. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was used, with adjustment for age, sex, and professional role; calendar time was used as the time scale to account for differences in the prevalence of infection over time (details are provided in the Supplementary Appendix). No participants died or were lost to follow-up.

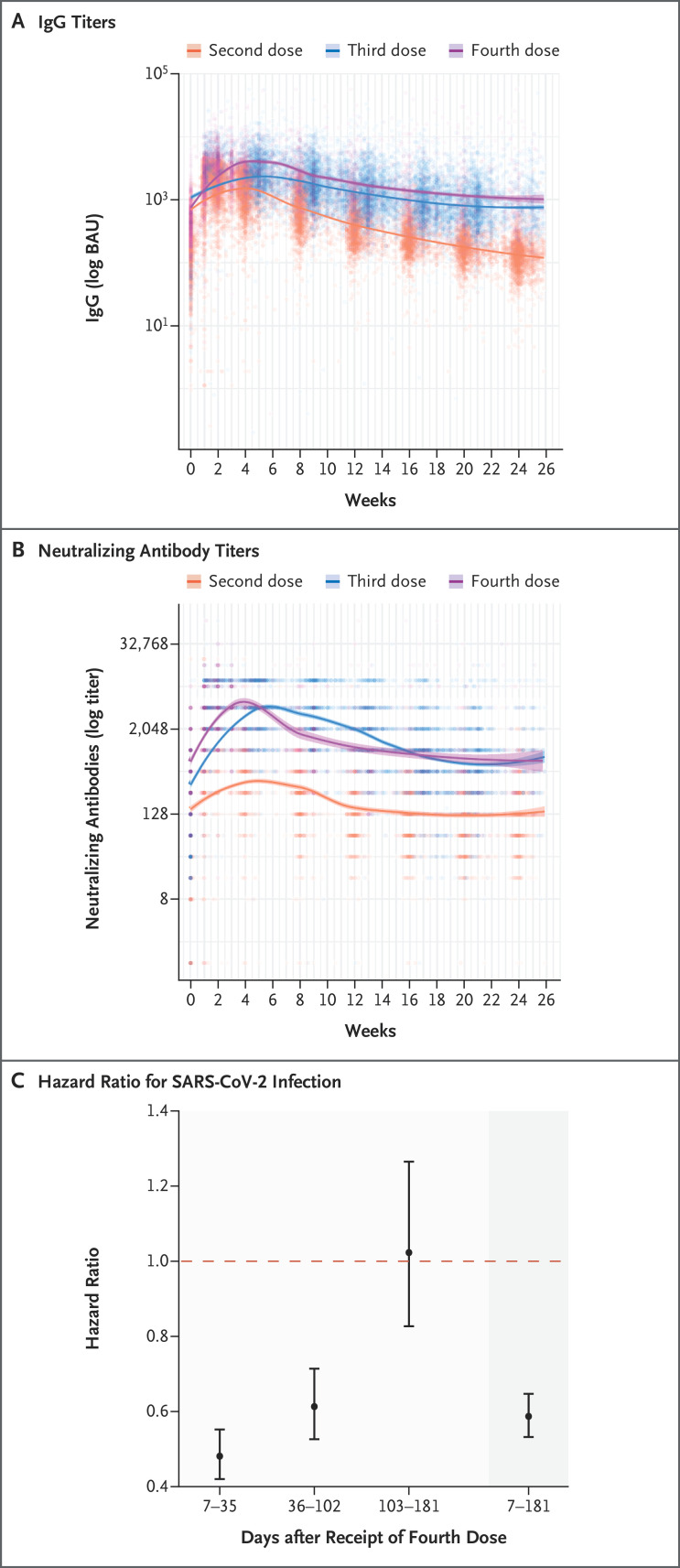

Among the participants who had not had previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, 6113 were included in the analysis of humoral response and 11,176 in the analysis of vaccine effectiveness (Fig. S1 and Tables S2 and S3). Antibody response peaked at approximately 4 weeks, waned to levels seen before the fourth dose by 13 weeks, and stabilized thereafter. Throughout the 6-month follow-up period, the adjusted weekly levels of IgG and neutralizing antibodies were similar after receipt of the third and fourth doses and were markedly higher than the levels seen after receipt of the second dose (Figure 1A and 1B and Table S4).

Figure 1. Six-Month Follow-up of Immunogenicity and Vaccine Effectiveness after a Fourth BNT162b2 Vaccine Dose.

Panels A and B show IgG and neutralizing antibody titers, respectively, up to 26 weeks after the second, third, and fourth doses of the BNT162b2 (Pfizer–BioNTech) vaccine. Locally weighted scatterplot smoothing is overlaid. Panel C shows the vaccine effectiveness against any severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection 7 to 35 days, 36 to 102 days, 103 to 181 days, and 7 to 181 days (representing the full study period [darker-shaded area]) after the fourth vaccine dose (administered at least 4 months after receipt of the third dose) as compared with the effectiveness of three vaccine doses. Vaccine effectiveness (measured as 1 minus the hazard ratio) is estimated from a Cox proportional hazards regression model, with adjustment for age, sex, and professional role. Calendar time was used as the time scale to further adjust for differing infection prevalence over time. A dashed horizontal line is shown at a hazard ratio of 1, which indicates no effect. 𝙸 bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. BAU denotes binding antibody units.

The cumulative incidence curve is shown in Figure S2, and vaccine effectiveness is shown in Figure 1C. Receipt of the fourth BNT162b2 vaccine dose conferred more protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection than that afforded by the receipt of three vaccine doses (with receipt of the third dose having occurred at least 4 months earlier) (overall vaccine effectiveness, 41%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 35 to 47). Time-specific vaccine effectiveness (which, in our analysis, compared infection rates among participants who had not yet been infected since vaccination) waned with time, decreasing from 52% (95% CI, 45 to 58) during the first 5 weeks after vaccination to −2% (95% CI, −27 to 17) at 15 to 26 weeks.

The study has several limitations. First, although our cohort consisted of a diverse population that included older-adult volunteers, a cohort consisting of health care workers may not be representative of the general population. Furthermore, only health care workers who had not had previous SARS-CoV-2 infection were included, which further limited generalizability. Second, possible confounding of unrecognized hybrid immunity may have remained, despite thorough history-taking and serologic assessment. Third, the decision to receive the fourth dose could be linked to health-seeking behaviors that were not well-captured in our data, thus possibly resulting in additional residual confounding. Fourth, we were unable to estimate effectiveness against severe outcomes of infection owing to the absence of such outcomes in our study cohort; a third dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine has been shown to confer durable protection against such outcomes.3 Previous studies have shown increased effectiveness of a fourth dose against severe outcomes during short-term follow-up,4,5 but whether this additional effectiveness wanes similarly to the protection against infection has yet to be determined.

In this prospective cohort study, a third dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine led to an improved and sustained immunologic response as compared with two doses, but the additional immunologic advantage of the fourth dose was much smaller and had waned completely by 13 weeks after vaccination. This finding correlated with waning vaccine effectiveness among recipients of a fourth dose, which culminated in no substantial additional effectiveness over a third dose at 15 to 26 weeks after vaccination. These results suggest that the fourth dose, and possibly future boosters, should be timed wisely to coincide with disease waves or to be available seasonally, similar to the influenza vaccine. Whether multivalent booster doses will result in longer durability remains to be seen.

Supplementary Appendix

Disclosure Forms

This letter was published on November 9, 2022, at NEJM.org.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Levin EG, Lustig Y, Cohen C, et al. Waning immune humoral response to BNT162b2 Covid-19 vaccine over 6 months. N Engl J Med 2021;385(24):e84-e84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kliker L, Zuckerman N, Atari N, et al. COVID-19 vaccination and BA.1 breakthrough infection induce neutralising antibodies which are less efficient against BA.4 and BA.5 omicron variants, Israel, March to June 2022. Euro Surveill 2022;27:2200559-2200559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barda N, Dagan N, Cohen C, et al. Effectiveness of a third dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine for preventing severe outcomes in Israel: an observational study. Lancet 2021;398:2093-2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magen O, Waxman JG, Makov-Assif M, et al. Fourth dose of BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide setting. N Engl J Med 2022;386:1603-1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bar-On YM, Goldberg Y, Mandel M, et al. Protection by a fourth dose of BNT162b2 against omicron in Israel. N Engl J Med 2022;386:1712-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.