Abstract

Background:

A rabies outbreak in dogs occurred on February 22, 2021, in the Samtse Municipality, Bhutan. A rapid response team (RRT) was activated comprising of human and animal health teams to investigate and contain this outbreak. An assessment of the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) on rabies was elicited during this period to develop evidence-based education material.

Methods:

A face-to-face KAP questionnaire was administered to a volunteer member of 55 households in two communities (Norbuling and Xing Workshop areas) following the rabies outbreak in the Samtse Municipality from March 15 to 22, 2021. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the demographic characteristics. The associations between the KAP scores were assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient.

Results:

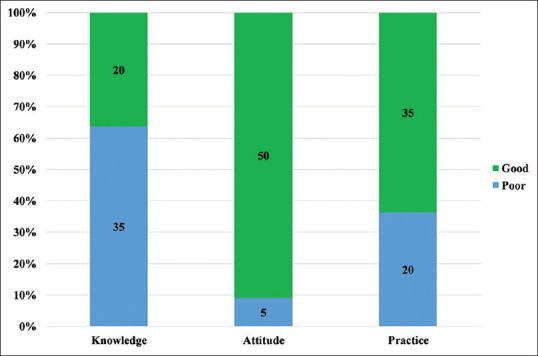

Of the 55 respondents, 63.6% (35) had poor knowledge, 90.9% (50) and 63.6% (35) reported good attitude and practice toward rabies. Three (5.5%) participants had not heard about rabies. The other misconceptions were that rabies can be prevented with antibiotics (67.3%, 37), dressing the bite wounds (20.0%, 11), and seeking treatment from the local healer (5.5%, 3). Correct knowledge was reported on excessive salivation as the sign of the rabid animal (58.2% 32), rabies prevention through vaccination (81.8%, 45), and seeking medical care on the same day (94.5%, 52). Eighty-nine percent (49) vaccinated their dogs and domestic animals annually, 100% received post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) after an animal bite, 78.2% (43) washed the animal bite wounds with soap and water, and 9.1% (5) would consult the local healer for animal bites. A majority (78.2%, 43) of them agreed that rabies is a serious public health problem in the Samtse Municipality and 49.1% (27) agreed that the public was adequately informed about rabies. A positive correlation was observed between the knowledge-practice scores (r = 0.3983, P value = 0.0026), and attitude-practice scores (r = 0.4684, P value < 0.001).

Conclusion:

The poor knowledge of rabies in this study needs to be addressed urgently. The main misconceptions included were that rabies is not fatal, dressing animal bite wounds, and seeking dog and animal bite care from local healers. Health education should focus on these misconceptions.

Keywords: Attitude, Bhutan, knowledge, outbreak, practice, rabies, Samtse

Introduction

Rabies is a zoonotic, fatal, and progressive neurological infection caused by the rabies virus (RABV) of the genus Lyssavirus and family Rhabdoviridae.[1] In up to 99% of the cases, domestic dogs are responsible for the rabies virus transmission to humans.[2] Yet, rabies can affect both domestic and wild animals. It is spread to people through bites or scratches, usually via saliva.[3,4] It is estimated that globally canine rabies causes approximately 59,000 deaths in humans with over 3.7 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and 8.6 billion USD (economic losses annually).[5] Over 95% of the mortality happens in Asia and Africa, where canine rabies is enzootic.[6] Globally, rabies deaths are rarely reported and children between the ages of 5 and 14 years are frequent victims.[7] Treating a rabies exposure, where the average cost of rabies post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is US$ 40 in Africa and US$ 49 in Asia, can be a catastrophic financial burden on the affected families whose average daily income is around US$ 1–2 per person.[7]

Frequent outbreaks of rabies in animals occurred throughout Bhutan until 1992.[8] However, with the launch of mass dog vaccination and population control, the incidence of rabies in the interior parts of the country has been controlled.[9] At present, animal rabies is confined to the south of the country including Samtse which borders India.[10,11,12] However, sporadic dog rabies outbreaks occur in rabies-free districts due to the incursion from the rabies endemic districts.[13,14] Rabies in humans is reported infrequently in Bhutan.[8,9,15]

On February 22, 2021, a suspected rabid dog, a juvenile male stray dog bit many dogs: 16 strays and 11 pet dogs in the Norbuling and Xing Workshop areas under the Samtse Municipality. It died on the same day and the rapid field test was positive for rabies (personal communication). All stray and pet dogs who were bitten by the rabid dog were quarantined for 45 days and observed daily twice for any behavioral changes and other rabies signs. These dogs were provided with PEP during the quarantine. None of the dogs showed signs of rabies or died of rabies. A multisectoral rapid response team (RRT) from the health and livestock agencies visited the outbreak area to investigate and initiate a control program.

Primary health workers, family physicians, and livestock officials are the frontline workers in dealing with animal bites and rabies from domestic animals. Therefore, understanding the community knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) on rabies are important in devising appropriate educational messages and responses. Therefore, to understand the community’s KAP on rabies and explore insights from the affected community, a quick questionnaire survey was conducted among the residents of the Norbuling and Xing Workshop areas under the Samtse Municipality, Bhutan.

Materials and Methods

Study area

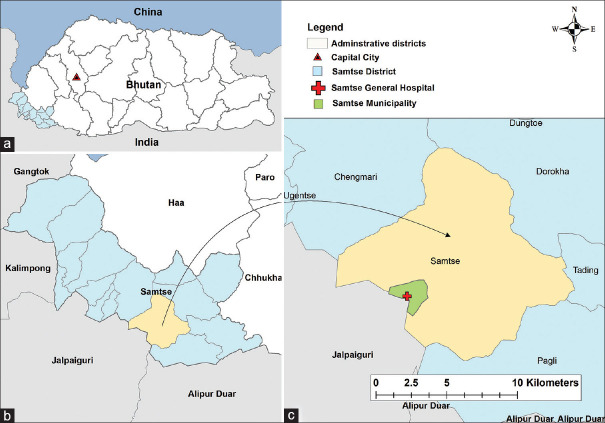

Samtse district is in the southwest of Bhutan and shares borders with the Haa and Chukha districts in the north and east, Alipurduar and Jalpaiguri districts of West Bengal in the south, and Kalimpong district of West Bengal and Gangtok district of Sikkim in the west [Figure 1]. The Samtse Municipality is the district headquarter of the Samtse district with a population of 5,396 in 2017[16] with a total area of 4.8 sq. m. In addition, most people of the Samtse district traveling to other parts of Bhutan have to travel through the Samtse Municipality and India through the Integrated Check Post of Samtse. The survey was conducted in the Norbuling and Xing Workshop areas. These areas were purposively selected because a rabid dog was identified in these areas on February 22, 2021, and stray and pet dogs were bitten by it.

Figure 1.

Map of (a) Bhutan, (b) Samtse district, and (c) Samtse Municipality, Bhutan

Survey methodology

A rapid cross-sectional study was conducted in two areas of the Samtse Municipality. A face-to-face KAP questionnaire was administered to one household member in all the 55 households in the area. The questionnaire was divided into four parts: (i) sociodemographic characteristics; (ii) knowledge domain; (iii) attitude domain, and (iv) practice domain.

The first part included the sociodemographic characteristics including age, sex, education level, occupation, household income, household members, children (<12 years), number and types of pets, number and types of livestock, history of bits, PEP, and source of information. The knowledge domain consisted of 10 questions including whether they have heard about rabies, signs of rabid animals, the transmitters and routes of rabies transmission, prevention of rabies, control of dog-mediated rabies, and home management of the animal bite wounds. Four questions were on attitude and it was referred to a person’s opinion or thoughts or viewpoint toward a given situation or scenario.[17] The six practice questions were on vaccination of dogs and domestic animals, PEP following an animal bite, wound management, seeking care from the local healer, social response, and management of pet animals.

Data analysis

The knowledge domain had 10 questions and each correct question was scored “1” and “0” for incorrect or do not know responses. Bloom’s cutoff of 80% (≥25.6) was used to determine good knowledge.[18] The attitude domain (four questions) was measured on an ordinal scale using a three-point Likert scale (2 = agree, 1 = don’t know, 0 = no). The practice domain (six questions) was measured using a five-point Likert scale: strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree. The neutral carried 0 scores while positive attitudes such as agree and strongly agree carried a score of “1” and “2”. While negative attitudes such as disagree and strongly disagree were given “-1” and “- 2”, respectively. In the case of negatively quoted questions, reverse scoring was used. The participants’ average attitude (>4.0) and practice (>6.0) score was set as a cutoff value for the good attitude and practice toward rabies.[18,19]

Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were used to describe the demographic characteristics. Pearson’s correlation was carried out for the scores of knowledge with attitude and practice and the scores of attitude and practice, to measure the relationship between them.[20] The P-level < 0.05 was considered significant. The data were entered in a Microsoft Excel Worksheet (Microsoft Cooperation) and analyzed using Stata version 16 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) software. The study map was developed with ArcMap 10.5.1 (ESRI, Redlands, CA).

Results

Demographic characteristics of the respondents

A total of 55 respondents from 55 households were interviewed and 60% (33) were males. The average age of the participants was 34.3 years (range 20–74 years). Nearly half (47.3%, 26) of participants were in the age group of 20–30 years. Fifty-six percent (31) completed secondary education and 32.7% (18) were business persons. Nearly half (43.6%, 24) of the respondents were in the income level range of between Nu 11,000 and 20,000 (USD1 = Nu 71.50). Thirty-five percent (19) owned pets with dogs (52.6%, 10) being the commonest. They also owned other livestock including hens and cows. Friends and relatives were the commonest sources of information (70.9%, 39), followed by the veterinary public health officials (52.7%, 29) and BBS TV (47.3%, 26). Less than half (20) of the study respondents had a history of animal bite at least once in their lifetime, and 80.0% (16) availed of PEP for rabies. However, four respondents never received PEP after the bite [Table 1].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study population in Samtse Municipality, Bhutan

| Variables | Categories | Number | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 22 | 40.0 | |

| Male | 33 | 60.0 | |

| Age group | |||

| 20-30 | 26 | 47.3 | |

| 31-40 | 15 | 27.2 | |

| 41-50 | 8 | 14.6 | |

| 51+ | 6 | 10.9 | |

| Education | |||

| No formal schooling | 8 | 14.6 | |

| Non-formal education | 2 | 3.6 | |

| Primary school | 6 | 10.9 | |

| Secondary school | 31 | 56.4 | |

| Graduate | 8 | 14.6 | |

| Occupation | |||

| Private company | 10 | 18.2 | |

| Business | 18 | 32.7 | |

| Housewife | 6 | 10.9 | |

| Armed force | 4 | 7.3 | |

| Others | 17 | 30.9 | |

| Income (Nu)* | |||

| 5,000-10,000 | 17 | 30.9 | |

| 11,000-20,000 | 24 | 43.6 | |

| 21,000-30,000 | 8 | 14.6 | |

| 31,0000+ | 6 | 10.9 | |

| Household members | |||

| One | 3 | 5.4 | |

| 2 to 4 | 31 | 56.4 | |

| 5+ | 21 | 38.2 | |

| Under 12 years | |||

| 0 | 29 | 52.7 | |

| 1 | 11 | 20.0 | |

| 2+ | 15 | 27.3 | |

| Pets | |||

| No | 36 | 65.5 | |

| Yes | 19 | 34.5 | |

| Pet types (n=19) | |||

| Cat | 6 | 31.6 | |

| Dog | 10 | 52.6 | |

| Dog & Cat | 3 | 15.8 | |

| Livestock | |||

| No | 45 | 81.8 | |

| Yes | 10 | 18.2 | |

| Livestock types | |||

| None | 45 | 81.8 | |

| Hen | 7 | 12.7 | |

| Cow | 1 | 1.8 | |

| Cow & hen | 2 | 3.6 | |

| Past bites | |||

| No | 35 | 63.6 | |

| Yes | 20 | 36.4 | |

| Bite site (n=20) | |||

| Leg | 12 | 60.0 | |

| Hand | 6 | 30.0 | |

| Thigh | 2 | 10.0 | |

| PEP | |||

| No | 4 | 20.0 | |

| Yes | 16 | 80.0 | |

| Source of information | |||

| Kuensel | 18 | 32.7 | |

| BBS TV | 26 | 47.3 | |

| BBS Radio | 16 | 29.1 | |

| Friends/relatives | 39 | 70.9 | |

| Government officials | 29 | 52.7 | |

| All of the above | 13 |

*USD1~Nu 71.50; PEP- post-exposure prophylaxis

Respondent’s knowledge about rabies

The knowledge level was poor with 63.6% (35) scoring less than 25.6 points (<80% of the total score) [Figure 1] with a mean score of 24.5 (standard deviation [SD] = 4.1). Three participants (5.5%) had not heard about rabies. More than half (58.2%, 32) of the respondents identified excessive salivation as the common sign of a rabid animal. Whereas, other rabid signs in an animal including lazy and dull (14.5%, 8), eating abnormal things (20.0%, 11), and abnormal walking (14.5%, 8) were less commonly identified. Most participants reported that dogs (87.3%, 48), wild dogs (67.3%, 37), and cats (60.0%, 33) can transmit rabies. Three participants reported that wild birds can transmit rabies and 20.0% (11) of the respondents reported that rabies cannot be prevented. However, 67.3% (37) responded that rabies can be prevented by antibiotics. Nearly all (52) knew that they should visit the hospital on the same day of the animal bite. Seven percent (4) reported that no action is required if the pet/livestock bites another animal or human being. Nearly 82.0% (45) of the participants thought that dog-medicated rabies can be controlled through vaccination of dogs and education of the public on rabies. Only 34.5% (19) reported that restricting the movement of pet dogs can prevent dog-mediated rabies. The correct home management of dog bites was washing the bite site- 67.3% (37), applying antiseptic- 45.5% (25), and applying 70% alcohol- 18.2% (10). Wrong home management of dog bite wounds was dressing in 20.0% (11), applying salt 12.7% (7), and consulting local healers (5.5%, 3) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Knowledge of rabies, symptoms in animals, and treatment of animal bites in Samtse Municipality, Bhutan

| Questions | Response | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Have heard about rabies? | |||

| Yes | 52 | 94.5 | |

| No | 3 | 5.5 | |

| Signs of rabid animals. | |||

| Dropping tail | 17 | 30.9 | |

| Excessive salivation | 32 | 58.2 | |

| Aggressive and red eyes | 22 | 40.0 | |

| Laziness and dullness | 8 | 14.5 | |

| Eats abnormal things | 11 | 20.0 | |

| Abnormal walk | 8 | 14.5 | |

| Animals that can transmit rabies. | |||

| Dog | 48 | 87.3 | |

| Cat | 33 | 60.0 | |

| Livestock | 18 | 32.7 | |

| Bats | 25 | 45.5 | |

| Wild dogs | 37 | 67.3 | |

| Wild cats | 29 | 52.7 | |

| Wild birds | 3 | 5.5 | |

| Rodents | 20 | 36.4 | |

| How can you get rabies? | |||

| Bites | 52 | 94.5 | |

| Scratch | 39 | 70.9 | |

| Lick intact skin | 29 | 52.7 | |

| Drink milk of rabid cow | 31 | 56.4 | |

| Seeing rabid animal | 2 | 3.6 | |

| Contact with urine of the rabid animal | 50 | 90.9 | |

| Can rabies be prevented? | |||

| Yes | 44 | 80.0 | |

| No | 11 | 20.0 | |

| How can rabies be prevented? | |||

| Antibiotics | 37 | 67.3 | |

| PEP | 40 | 72.7 | |

| Vaccinate animals | 45 | 81.8 | |

| Control dog population | 30 | 54.5 | |

| When to visit hospital after the animal bite? | |||

| Same day | 52 | 94.5 | |

| >1 day | 3 | 5.5 | |

| If your pet/livestock bites a man or an animal, what would you do? | |||

| No action | 4 | 7.3 | |

| Look after the animal | 20 | 36.4 | |

| Isolate animal | 32 | 58.2 | |

| How can dog-medicated rabies be controlled in humans? | |||

| Vaccinate dogs | 45 | 81.8 | |

| Restrict dog | 19 | 34.5 | |

| Education of public | 45 | 81.8 | |

| Control stray dog population | 37 | 67.3 | |

| PEP | 43 | 78.2 | |

| Home management of dog/animal bites. | |||

| Washing of bite site | 37 | 67.3 | |

| Dress the bite site | 11 | 20.0 | |

| Apply salt | 7 | 12.7 | |

| No action | 15 | 27.3 | |

| Apply 70% alcohol | 10 | 18.2 | |

| Apply antiseptic | 25 | 45.5 | |

| Consult local healers | 3 | 5.5 |

PEP- post-exposure prophylaxis

Respondent’s attitude about rabies

More than 90.9% (50) had a good attitude [Figure 2] with a mean of 6.6 (SD = 1.8). Three participants did not know it was fatal. More than 78.2% (43) agreed that rabies was a public health problem and only 49.1% (27) agreed that the public was adequately informed about rabies. About 81.1% (45) agreed that stray dogs were a problem in the Samtse Municipality [Table 3].

Figure 2.

Knowledge, attitude, and practice scores of the study participants, Samtse Municipality, Bhutan

Table 3.

Attitude response toward rabies in Samtse Municipality, Bhutan

| Question | Response | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Is rabies a public health problem? | |||

| No | 1 | 1.8 | |

| Yes | 43 | 78.2 | |

| Don’t know | 11 | 20.0 | |

| Is rabies fatal? | |||

| No | 3 | 5.5 | |

| Yes | 43 | 78.2 | |

| Don’t know | 9 | 14.3 | |

| Are public adequately informed about rabies? | |||

| No | 5 | 9.1 | |

| Yes | 27 | 49.1 | |

| Don’t know | 23 | 41.8 | |

| Is the stray dog a problem in Samtse Municipality? | |||

| No | 4 | 7.3 | |

| Yes | 45 | 81.8 | |

| Don’t know | 6 | 10.9 |

Respondent’s practice about rabies

A good practice toward rabies was reported by 63.6% (35) of the respondents [Figure 2] with a mean of 8.2 (SD = 3.2). Sixty-six percent (36) vaccinated their domestic animals including dogs annually. Most of them (85.5%, 47) strongly agreed to get PEP after animal bites and 78.2% (43) of them washed the bite site with soap and water. Of the study participants, 9.1% (5) agreed or strongly agreed to seek the help of the local healers after an animal bite. Around 30.9% (17) of the respondents strongly agreed to keep their pets away from stray dogs and 89.1% (49) of them vaccinated their pets annually [Table 4].

Table 4.

Practice response toward rabies in Samtse Municipality, Bhutan

| Question | Response | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| I vaccinate my dogs and domestic animal annually. | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 1 | 1.8 | |

| Disagree | 1 | 1.8 | |

| Neutral | 4 | 7.3 | |

| Agree | 13 | 23.6 | |

| Strongly Agree | 36 | 65.5 | |

| I get post-exposure vaccination after an animal bite. | |||

| Strong Disagree | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Disagree | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Neutral | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Agree | 8 | 14.5 | |

| Strongly Agree | 47 | 85.5 | |

| I wash animal bite wounds with soap and water. | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 1 | 1.8 | |

| Disagree | 1 | 1.8 | |

| Neutral | 10 | 18.2 | |

| Agree | 10 | 18.2 | |

| Strongly Agree | 33 | 60.0 | |

| I go to a local healer after an animal bite. | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 35 | 63.6 | |

| Disagree | 13 | 23.6 | |

| Neutral | 2 | 3.6 | |

| Agree | 3 | 5.5 | |

| Strongly Agree | 2 | 3.6 | |

| If I see rabies suspected dog/animals, I report to concerned officials (livestock officer). | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 3 | 5.4 | |

| Disagree | |||

| Neutral | 2 | 3.6 | |

| Agree | 14 | 25.5 | |

| Strongly Agree | 36 | 65.5 | |

| I keep my pet animals in a secure place away from stray dogs. | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 1 | 1.8 | |

| Disagree | 7 | 12.7 | |

| Neutral | 16 | 29.1 | |

| Agree | 14 | 25.5 | |

| Strongly Agree | 17 | 30.9 |

Correlation between the knowledge, attitude, and practice scores

A positive correlation was observed between the knowledge-practice score (r = 0.3983, P value = 0.0026) and attitude-practice score (r = 0.4684, P value < 0.001), respectively [Table 5].

Table 5.

Correlation between knowledge, attitude, and practice scores

| Variables | Correlation coefficient | P |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge- Practice | 0.3983 | 0.0026* |

| Knowledge-Attitude | 0.1944 | 0.155 |

| Attitude-Practice | 0.4684 | <0.001* |

*significant at P<0.05

Discussion

In this study, the overall knowledge was poor, but there was a good attitude and practice toward rabies. The common misconceptions were that rabies is treatable and not fatal, preventing rabies with antibiotics, dressing animal bite wounds, and consulting local healers for animal bites. A high proportion of the participants vaccinated their dogs and domestic animals annually and all received PEP for animal bites and more than two-thirds washed animal bites with soap and water. Correct knowledge was reported on the signs of the rabid animal as excessive salivation, rabies prevention through vaccination, and seeking medical care on the same day. A positive correlation was observed between knowledge-practice and attitude-practice.

Despite regular mass education on rabies by the government, the knowledge level was poor among the study participants as opposed to other studies in Bhutan.[21,22,23] Therefore, it is imperative to start regular education on rabies prevention in the district. Studies in the other parts of the world have shown that rabies awareness increased following an education campaign.[24] The misconceptions identified in this study included that rabies cannot be prevented, wild birds can transmit rabies, dressing animal bites, rabies can be prevented using antibiotics, and seeking local healers for animal bites. It is plausible this false knowledge could have originated from friends and relatives because two-thirds of the participants’ sources of information were friends and relatives as in another study on rabies from other parts of Bhutan, where neighbors were the most common source of information.[25]

The study participants showed a good attitude and practice toward rabies as in the other studies.[8,18,23] However, a small percent of the participants thought that the public was not adequately informed about rabies. Therefore, mass education on rabies should be undertaken immediately because the Samtse Municipality is in a high-risk area for rabies. Rabies continues to be a serious public health problem in Bhutan as highlighted by the participants. This is due to a large number of stray dogs in the country, estimated to be around 48,379.[26,27] The government spends approximately Nu 9.3 million (USD 142,000) on PEP each year for 7,000 dog bites.[8,9]

Some participants sought help from the local healers for animal bites as reported in the other studies.[28] This could be due to a strong cultural influence in Bhutan which is involved in all facets of most Bhutanese lives. Therefore, educating the local healers on rabies and animal bites should be considered as was done in Vietnam[29] so they refer dog and animal bites to the hospital for the appropriate management and encourage the vaccination of domestic animals.

There was a serious misconception that rabies was not fatal. Some participants had not heard about rabies. Such misconception could potentially delay seeking post-exposure care including PEP. In this study, 20% did not get PEP after an animal bite. Delaying or not receiving PEP could result in serious outcomes including death. In 2020, there was one human death due to probable rabies in the Samtse district.[30] In addition, the risk of rabies spillover to the Samtse district from India is high due to the porous border and the Indian state of West Bengal being endemic for rabies.[31,32] Therefore, the public should be educated that rabies is fatal and should seek care after a bite from animals including dogs. This will significantly help in achieving the national and international goals of rabies elimination by 2030[33] through regularly vaccinating pets and seeking appropriate post-exposure care.

The first aid measures (e.g., washing bite wounds with soap and water) and seeking medical care is important for rabies prevention in humans since most people in developing countries die of rabies due to failure to seek medical care in time.[34] In this study, all participants sought medical care for animal bites. A similar finding was reported in another part of Bhutan.[21] Compared to other developing countries, the health-seeking behavior of people in Bhutan for PEP is high.[9,15,26,35] This can be partly explained due to free health care services in the country including PEP as enshrined in the constitution of Bhutan.

Most participants identified excessive salivation as the commonest sign of rabies. Other signs of rabies including dropping tail, aggressive and red eyes, laziness and dullness, abnormal walking, and eating abnormal things were less commonly reported. The knowledge of the signs of rabies is important for prompt preventive action. Studies have shown that knowledge influenced the attitude toward the disease.[17,36] Therefore, the public should be informed of the correct signs of rabies during mass education and campaigns.

The correlation analysis results showed a positive correlation between knowledge-practice and attitude-practice. Similar findings were reported in other studies.[32,37,38] This suggests that good knowledge and attitude toward rabies can lead to good practices. Knowledge affects the individual’s behavior and a higher knowledge level reinforces healthier behaviors.[39] Therefore, increasing the knowledge level of rabies among the population of the Samtse district can further improve the attitude and practice.

Limitations of the study

The study results should be interpreted considering the following limitations. First, due to the convenience sampling method, recruitment bias may have occurred. Second, a small sample size could not support the stratification of KAP into three groups. Third, the results may not sufficiently represent the whole population of the Samtse district and could not be generalized to Bhutan. Despite these limitations, this is the first KAP study in the Samtse Municipality and identified knowledge gaps, misconceptions, and improper practice in the study area. The misconceptions and knowledge gaps identified in this study should be reinforced during the community awareness and health education by the public and livestock officials in the Samtse Municipality.

Conclusion

In conclusion, knowledge about rabies was poor with misconception on the non-fatal nature of rabies, dressing of animal bite wounds, and that rabies can be prevented by using antibiotics and seeking care from local traditional healers. Therefore, educating the community about rabies should be started in earnest with the involvement of local traditional healers through existing advocacy channels such as BBS TV and radio. An important educational message should include the fatal nature of rabies, the risk of transmission of rabies by other domestic animals, and getting PEP following an animal bite. Lastly, it is recommended to undertake a study with an adequate sample size to understand the KAP level and covariates of KAP on rabies in the Samtse Municipality and Samtse district.

Ethical approval and Consent to participate

The data was collected during an outbreak response by the RRT, so no ethical approval was necessary. However, verbal consent from the participants was obtained before the interview.

Ethical approval

Since this survey was conducted as part of emergency response during the outbreak and no ethical approval was necessary.[21,40] A volunteer (anyone interested to respond) from each household was informed about the purpose of the study in the language of the participants. The participants were allowed to ask questions or raise any concerns about the study. After they were thoroughly satisfied with our responses, verbal consent was obtained before the interview. All data collected in this study were de-identified (no personal information) and confidentiality was maintained during the study and after the study. The data were maintained in the password-secured folder on the computer with access only to the researchers.

Key messages

The knowledge of the study participants was unsatisfactory but reported a good attitude and practice. The main misconceptions included were that rabies was not fatal, dressing of animal bite wounds, antibiotics prevented rabies, and seeking local traditional healers for animal bites. The positive practice included vaccinating their dogs and domestic animals annually, receiving PEP for animal bites, and washing animal bites with water and soap. The misconceptions and knowledge gaps identified in this study should be reinforced and educated by the treating physicians and public health workers in the Samtse Municipality.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions

KL and KW were involved in the conception and design of this study. KL undertook the collection of the data and interpretation of the results. KL and KW analyzed and drafted the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study did not receive any funding.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the study participants. We would like to also thank Dr Chendu (vet) for sharing his write-up summary on the outbreak response from the veterinary perspective.

References

- 1.WHO. WHO expert consultation on rabies. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher CR, Streicker DG, Schnell MJ. The spread and evolution of rabies virus: Conquering new frontiers. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16:241–55. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2018.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunker K, Mollentze N. Rabies virus. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26:886–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sparkes J, Fleming PJ, Ballard G, Scott-Orr H, Durr S, Ward MP. Canine rabies in Australia: A review of preparedness and research needs. Zoonoses Public Health. 2015;62:237–53. doi: 10.1111/zph.12142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hampson K, Coudeville L, Lembo T, Sambo M, Kieffer A, Attlan M, et al. Estimating the global burden of endemic canine rabies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. WHO. Expert consultation on rabies: Second report. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabies. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rabies . [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penjor K, Tenzin T, Jamtsho RK. Determinants of health seeking behavior of animal bite victims in rabies endemic South Bhutan: A community-based contact-tracing survey. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:237. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6559-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tenzin, Wangdi K, Ward MP. Human and animal rabies prevention and control cost in Bhutan, 2001-2008: The cost-benefit of dog rabies elimination. Vaccine. 2012;31:260–70. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tenzin, Dhand NK, Ward MP. Anthropogenic and environmental risk factors for rabies occurrence in Bhutan. Prev Vet Med. 2012;107:21–6. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tenzin, Dhand NK, Ward MP. Patterns of rabies occurrence in Bhutan between 1996 and 2009. Zoonoses Public Health. 2011;58:463–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2011.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kole AK, Roy R, Kole DC. Human rabies in India: A problem needing more attention. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:230. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.136044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tenzin, Dhand NK, Dorjee J, Ward MP. Re-emergence of rabies in dogs and other domestic animals in eastern Bhutan, 2005-2007. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139:220–5. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810001135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tenzin, Sharma B, Dhand NK, Timsina N, Ward MP. Reemergence of rabies in Chhukha district, Bhutan, 2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1925–30. doi: 10.3201/eid1612.100958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tenzin, Dhand NK, Gyeltshen T, Firestone S, Zangmo C, Dema C, et al. Dog bites in humans and estimating human rabies mortality in rabies endemic areas of Bhutan. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.37th ed. Thimphu, Bhutan: 2018. NSB. 2017 Population &Housing Census of Bhutan. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monje F, Erume J, Mwiine FN, Kazoora H, Okech SG. Knowledge, attitude and practices about rabies management among human and animal health professionals in Mbale District, Uganda. One Health Outlook. 2020;2:24. doi: 10.1186/s42522-020-00031-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banik R, Rahman M, Sikder MT, Rahman QM, Pranta MUR. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to the COVID-19 pandemic among Bangladeshi youth: A web-based cross-sectional analysis. Z Gesundh Wiss. 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10389-020-01432-7. doi: 10.1007/s10389-020-01432-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olum R, Chekwech G, Wekha G, Nassozi DR, Bongomin F. Coronavirus disease-2019: Knowledge, attitude, and practices of health care workers at Makerere University Teaching Hospitals, Uganda. Front Public Health. 2020;8:181. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sivagurunathan C, Umadevi R, Balaji A, Rama R, Gopalakrishnan S. Knowledge, attitude, and practice study on animal bite, rabies, and its prevention in an urban community. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10:850–8. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1674_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tenzin T, Namgyal J, Letho S. Community-based survey during rabies outbreaks in Rangjung town, Trashigang, eastern Bhutan, BMC Infect Dis. 2016;2017;17:281. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2393-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lungten L, Rinchen S, Tenzin T, Phimpraphai W, de Garine-Wichatitsky M. Knowledge and perception of rabies among school children in rabies endemic areas of South Bhutan. Trop Med Inf Dis. 2021;6:28. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed6010028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christopher PM, Cucunawangsih C, Adidharma A, Putra I, Putra DGS. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding rabies among community members: A cross-sectional study in Songan Village, Bali, Indonesia. Int Marit Health. 2021;72:26–35. doi: 10.5603/IMH.2021.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barroga TRM, Basitan IS, Lobete TM, Bernales RP, Gordoncillo MJN, Lopez EL, et al. Community awareness on rabies prevention and control in Bicol, Philippines: Pre- and post-project implementation. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2018;3:16. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed3010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rinchen S, Tenzin T, Hall D, van der Meer F, Sharma B, Dukpa K, et al. A community-based knowledge, attitude, and practice survey on rabies among cattle owners in selected areas of Bhutan. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rinzin K, Tenzin T, Robertson I. Size and demography pattern of the domestic dog population in Bhutan: Implications for dog population management and disease control. Prev Vet Med. 2016;126:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2016.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tenzin, Dhand NK, Ward MP. Human rabies post exposure prophylaxis in Bhutan, 2005-2008: Trends and risk factors. Vaccine. 2011;29:4094–101. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bihon A, Meresa D, Tesfaw A. Rabies: Knowledge, attitude and practices in and around South Gondar, North West Ethiopia. Diseases. 2020;8:5. doi: 10.3390/diseases8010005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Traditional Healers –A key player in One Health Rabies Eradication. Available from: http://www.fao.org/in-action/ectad-vietnam/news/detail/en/c/385176/

- 30.Lhendup K, Dorji T. Probable rabies in a child in a Bhutanese town bordering India, 2020. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2021;9:2050313x211019786. doi: 10.1177/2050313X211019786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mo HFW. National Health Profile 2019- 14th Issue. (Welfare MoHaF ed. Government of India: New Delhi, India. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chinnaian S, Ramachandran U, Arumugam B, Ravi R, Sekaran G. Knowledge, attitude, and practice study on animal bite, rabies, and its prevention in an urban community. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10:850–8. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1674_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. WHO. WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies: Second Report. Organization WHO ed. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knobel DL, Cleaveland S, Coleman PG, Fèvre EM, Meltzer MI, Miranda ME, et al. Re-evaluating the burden of rabies in Africa and Asia. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:360–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rana MS, Jahan AA, Kaisar SMG, Siddiqi UR, Sarker S, Begum MIA, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions about rabies among the people in the community, healthcare professionals and veterinary practitioners in Bangladesh. One Health. 2021;13:100308. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mascie-Taylor CG, Karim R, Karim E, Akhtar S, Ahmed T, Montanari RM. The cost-effectiveness of health education in improving knowledge and awareness about intestinal parasites in rural Bangladesh. Econ Hum Biol. 2003;1:321–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ali A, Ahmed EY, Sifer D. A study on knowledge, attitude and practice of rabies among residents in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Vet J. 2013;17:19–35. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Premashthira S, Suwanpakdee S, Thanapongtharm W, Sagarasaeranee O, Thichumpa W, Sararat C, et al. The impact of socioeconomic factors on knowledge, attitudes, and practices of dog owners on dog rabies control in Thailand. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:699352. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.699352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vandamme E. Concepts and challenges in the use of Knowledge-Attitude-Practice surveys: Literature review. Department of Animal Health. Institute of Tropical Medicine. 2009;1:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 40.WHO. Guidance for Managing Ethical Issues in Infectious Disease Outbreaks. 2016 [Google Scholar]