Abstract

This systematic review aims at offering a comparative analysis of the leading reasons for encounters (RFEs) of patients presenting to primary care facilities. A systemic search was carried out using MEDLINE/PUBMED, CINAHL, Google Scholar, LILACS, and PROQUEST to identify the studies relevant to RFEs in primary health care in June 2020. Fifteen studies met the eligibility criteria which included originality, published between 2015 and 2020, listed two to five RFEs at a primary health care facility, and included patients with acute and/or chronic conditions. The mean total RFEs recorded were 6753.07 (Standard deviation = 17446.38, 95% Confidence Interval 6,753.0667 ± 8,829.088 [± 130.74%]). The most common RFE chapters recorded were Respiratory and Digestive chapters. The patients recorded fever as the most frequently reported RFE while cough was ranked as most common. The physicians reported hypertension as the most frequently reported and most common RFE. The most frequently physician and patient reported RFEs to the primary health care are hypertension and fever. Respiratory and Digestive were the most frequently reported chapters. The findings are useful for the proper implementation of services, facilities, and equipment utilized in Trinidad and Tobago primary health care.

Keywords: Clinic visit, primary health care, reasons for encounters, systematic review, Trinidad and Tobago

Introduction

Aims

This qualitative systematic review seeks to provide a global comparative analysis of the major reasons for encounters (RFEs) with patients presenting to primary care facilities.

Background and rationale

The reasons why patients visit primary health care facilities are critical to understanding the disease burden and identifying society’s health care needs. This helps the policymakers plan health care services, design medical education curricula, and identify health research priorities relevant to the country’s needs. Understanding the reasons for encounters can enhance the delivery of health care services, therefore, improving the patients’ quality and outcome of care.[1] The primary care physicians can use these findings to formulate more targeted prevention campaigns and treatment interventions, thereby, increasing the standard of care.

Access to the literature regionally relative to the study is limited. ‘Patient Satisfaction at Health Centers in Trinidad and Tobago’ (1996) identifies the top five reasons for primary care visit as antenatal care (34.5%), hypertension (16.3%), diabetes (12.8%), hypertension and heart disease (11.0%), diabetes and hypertension (9.2%).[2] Thus, the primary goal of this systematic review was to provide a broad and current view of the use of primary care, to determine the most frequently reported RFEs, and to generate a list of the most common RFEs reported by patients and physicians.

Material and Methods

Ethics

This systematic review was approved by the University of the West Indies Ethics Committee on January 30, 2020. [Refer to Supplemental G]. Ref: CREC-SA.0093/11/2019.

Study Design

Study description

This study is a systematic review seeking to provide a global comparative analysis of the top RFEs presented by patients to primary health care (PHC) facilities. It was conducted as per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA). The research problem ‘What are the main reasons for the use of primary health care facilities?’ was formulated using the patient/population, intervention, comparison and outcomes model (PICOS) model. The PRISMA 2020 checklist—PRISMA statement was used and a PRISMA 2020 flow diagram was constructed for the search strategy. Fifteen studies that met the inclusion criteria were incorporated. Based on the results of similar studies, it is expected that the top five RFEs will include hypertension, diabetes, blood pressure check-ups, family planning, and cancer screening.

Data sources

Five databases (MEDLINE/PUBMED, CINAHL, Google Scholar, LILACS, and PROQUEST) were searched in June 2020. A particular vocabulary including Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and text words including all applicable synonyms focusing on “primary health care,” “reasons for use of primary health care,” “reasons for encounter,” and “utilization of primary care” were utilized via the Boolean Search. [Refer to Supplemental A for Database Search Strategy].

Study selection

Studies were eligible if they were original, published between 2015 and 2020, conducted in a PHC setting, had a minimum outcome of two to five RFEs in a PHC facility, and included acute and chronic patients.

The studies were excluded if the publications were from the same source, were not in English, focused solely on mental health, substance abuse, and social issues, and published before 2015. Editorials were excluded.

One researcher screened abstracts of articles from the databases to ensure relevance to the research problem. Two researchers reviewed the full-text articles to ensure compatibility with the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Three researchers extracted data which included RFEs at the PHC facility. The risk of bias and quality of each study was appraised using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies via a rating system.

Data analysis

All RFE were analyzed and recoded into international classification of primary care-2 (ICPC-2) classification. The data in the form of RFEs were categorized into the following three categories, according to the recorded data within the respective studies: RFE chapters, patient-reported RFEs, and physician-reported RFEs. The RFE chapters included RFEs that were reported as ICPC-2 chapters. The patient-reported RFEs were the patients’ reasons for visiting a PHC facility and physician-reported RFEs included the diagnoses made by the physician. Thirteen studies were included within all three categories. The remaining two studies were not included in the data analysis but were still included in this systematic review as they provided relevant information.

The data were analyzed as the ‘most frequently reported’ and ‘most commonly ranked.’ ‘Most frequently’ reported the most frequent RFE without consideration of its rank. ‘Most commonly’ analyzed RFEs by both its frequency and rank. Furthermore, the frequency of RFEs reported was shown in the form of bar charts for each category. The RFE chapters were further analyzed separately under Physician- and Patient-reported RFEs [Refer to Supplemental E]. Lastly, patient-reported RFEs and Physician-reported RFEs were compared. The first six RFEs within each category were ranked to formulate a list of the most common RFEs.

Quality assessment

The quality was assessed with consideration of the risk of biases. The quality assessment tool, NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies, was utilized. Each study was given a score out of 14. Higher scores indicated a higher quality and lower risk of bias. The PRISMA 2020 checklist was used to ensure the recommended criteria were met [Refer to Supplemental I for PRISMA 2020 Checklist].

Results

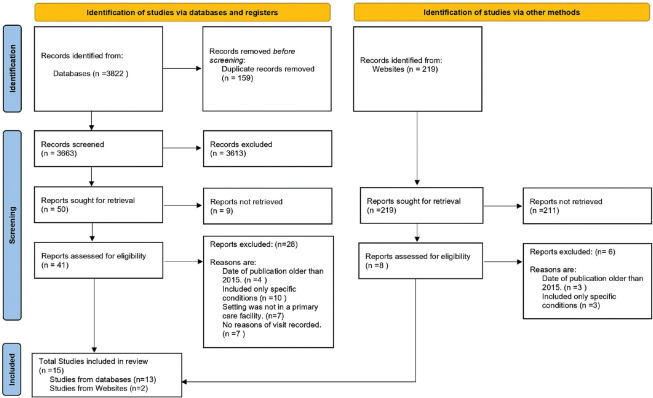

A total of 4,041 studies were identified; 3,822 were searched from databases and 219 from journal websites. A total of 3,882 studies were screened which resulted in 49 studies being assessed for eligibility; 34 studies were excluded since they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Thus, 15 studies passed the eligibility criteria and were included see [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Prisma 2020 flow chart showing the study selection of the included studies in this systematic review

Treatment of Results

Study characteristics

The characteristics were compared for the 15 studies included in this review.

Table 1 data determined that 2017 was the most frequent year of publication for eligible studies. The included studies were cross-sectional studies conducted in a PHC setting and measured RFEs as part of the reported outcomes.

Table 1.

Showing Comparison of Included Studies

| Study | Years of Data Collection | Duration of Data Collection | Method of Data collection | Country of Origin | Total Patient Population | Total Number of RFEs*/ Diagnoses/Processes Recorded | Total Visits | Age Range | Quality Score (/14) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adar et al. 2017[3] | August - November 2014 | 4 months | Analytical observational survey and questionnaire | Israel | 327 | N/A | 327 | 18-50 | 11 |

| Chueiri et al. 2020[4] | July - December 2016 | N/A | Interviews and questionnaires | Brazil | 6160 | 8046 RFEs | N/A | 18+ | 12 |

| Frese et al. 2016[5] | October, 1999 - September, 2000 | 1 year | Case recordings | Germany | 2866 | 4426 RFEs | N/A | 65+ | 9 |

| Liu et al. 2017[6] | 2014 | N/A | Electronic Medical Records | China | N/A | 13705 RFEs 15,460 Diagnoses | 10,000 | 27-65 | 9 |

| Meynard et al. 2015[7] | February 2009 - November 2010 | N/A | Questionnaire | Switzerland | 594 | N/A | N/A | 15-24 | 11 |

| Molony et al. 2015[8] | October 2010 - October 2014 | N/A | Electronic Medical Records | Ireland | 5210 | 70,489 RFEs | 52,572 | 0-80+ | 12 |

| Nyundo et al. 2020[9] | August - October, 2014 | 3 month | Questionnaire | Kenya | 628 | N/A | 715 | 18-24 | 9 |

| Olagundoye et al. 2016[10] | 2014 | 3 months | Patient Medical Records | Nigeria | N/A | 915 RFEs 546 Diagnoses 1221 Processes | 401 | Mean Age: 39 | 9 |

| Otovwe & Elizabeth. 2017[11] | N/A | N/A* | Semi Structured Questionnaire | Nigeria | 340 | N/A | N/A | 15-74 | 11 |

| Pati et al. 2017[12] | N/A | N/A | Interviews and questionnaires | India | 1649 | N/A | N/A | 18-70+ | 10 |

| Raknes & Hunskaar. 2017[13] | 2014 and 2015 | N/A | Electronic Medical Records | Norway | 177,053 | N/A | N/A | Mean Age: 36 | 11 |

| Salvi et al. 2015[14] | 2011 | 3 months | Questionnaire | India | 204,912 | N/A | N/A | 0-60+ | 11 |

| Seeger et al. 2019[15] | June- July 2017 | N/A | Questionnaire | Germany | 892 | 1112 RFEs | N/A | 0-70+ | 11 |

| Stegink et al. 2019[16] | 2011 | N/A | Electronic Medical Records | Scotland, UK | 507,934 | N/A | 782,281 | 18-70+ | 11 |

| Swain et al. 2017[17] | May - October 2014 | 7 weeks | Patient Medical Records | India | 2249 | 2603 RFEs 2023 Symptoms & Diagnoses | 2449 | 18-70+ | 7 |

N/A* - Not Available. RFEs*- Reasons for encounter.

Most studies collected data from 2014 with the earliest period being 1999–2000 while the most recent was 2017. The duration of sampling ranged from 7 weeks to 1 year.

The sample sizes were conducted by measuring the total patient population, the total number of RFEs/diagnoses/processes, and/or total visits (by patients). The included studies utilized at least one sample size measurement, a combination of two, or all three.

The mean total patient population was 60720.93 (SD = 135673.88, 95% CI: 60,720.9333 ± 68,660.455 [± 113.08%]). The highest total patient population was 5,07,934 whereas the lowest was 327 patients. The mean total RFEs was 6753.07 RFEs (SD = 17446.38, 95% CI: 6,753.0667 ± 8,829.088 [± 130.74%]), the highest total RFEs was 70,489 RFEs, and the lowest was 915 RFEs. Total diagnoses and total processes were reported along with total RFEs in the respective studies but were not reported in all the studies that included total RFEs. Therefore, for total diagnoses, only three studies included this sample population at 15,460, 546, and 2,023 diagnoses, respectively while for total processes, only one study reported 1,221 processes. The mean total visits were 56,583 visits (SD = 194389.58, 95% CI:.56,583 ± 98,374.699 [± 173.86%]), the highest total visits being 782,281, and the lowest 327 visits.

Ten studies included broad-age ranges while three studies contained specific age groups. Frese et al. 2016[5] were specific to the elderly, Meynard et al. 2015[7] were specific to the teenagers and young adults, and Nyundo et al. 2020[9] were specific to the young adults aged 18–24. Five studies included children within their sample population and no study was exclusive to children. Two studies did not state an age range but included the mean age.

All studies were rated out of 14 [Table 1] to determine the overall quality of each. The highest quality appraisal score was 12 and the lowest score was 7. The mean quality score was 10.26 (SD = 1.34, 95% CI: 10.2667 ± 0.678 [± 6.61%]).

The inconsistency in the quality score is related to the heterogeneity within the studies as the sample size, measurement of sample size, methods of data collection, years of data collection, and duration of data collection varied. Heterogeneity was observed within the reported outcomes since the total number of RFE classifications and age ranges in each study varied. Notwithstanding, homogeneity was observed as all the studies were consistently within a moderate-to-strong quality range, were of a cross-sectional study design, were conducted in primary care facilities, and reported RFEs.

Synthesis of evidence

The RFEs within the studies were grouped into three categories: RFE chapters, patient-reported RFEs, and physician-reported RFE. All RFEs were recoded using the ICPC-2 codes [refer to Supplemental D] and were analyzed by frequency among the 15 studies and by their ranking. None of the four categories contained all 15 studies, however, every study was represented in the results because each was featured in at least one category [refer to Supplemental B].

RFE chapters comprised ICPC-2 chapters of RFEs exclusively since seven studies already used this classification. Overall, 14 RFE chapters [Figure A1 (395.1KB, tif) - refer to Supplemental E] were reported. The respiratory and digestive chapters, present in all seven studies, were most frequently reported [Figure A1 (395.1KB, tif) - refer to Supplemental E], while general/unspecified was most frequently ranked the most common, despite being the third most frequently reported RFE chapter [Table A4 - refer to Supplemental E].

The following category is the patient-reported RFEs category. It included the first six RFEs that were reported by patients and was ranked from most to least common.

Overall, 41 patient-reported RFEs were found in 11 studies. Fever was the most frequently reported RFE, followed by cough. While pregnancy, health maintenance/prevention, abdominal pain, and chest pain general were third [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Bar chart displaying RFEs frequency as reported by patients

Patient-reported RFEs from the 11 studies were ranked from most to least common [Table A5 - refer to Supplemental E]. Cough, appearing in two studies, was most frequently ranked as the most common RFE. Fever although, most frequently reported, was ranked as most common in only one study.

Five studies contained RFEs in the Physician-reported RFEs category. The first ten physician-reported RFEs were compared and ranked from most common RFE to least common.

In all five studies, hypertension was the most frequently reported, followed by diabetes, and upper respiratory tract infection [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Bar Chart displaying the frequency of physician-reported RFEs in five studies

The first 10 physician-reported RFEs in each study were ranked from the most to least common [Table A6 - refer to Supplemental E]. Hypertension was the most frequently reported RFE and the most often ranked as the most common in all five studies. Malaria was the only other physician-reported RFE ranked most common in its respective study.

Discussion

Summary of the review

Respiratory and digestive were the RFE chapters which were most frequently reported in this review, while general/unspecified chapters were ranked as the most common. Patients most frequently reported fever followed by cough while physicians most frequently reported hypertension, followed by diabetes and upper respiratory tract infection.

Strengths and limitations of the study and methodology

The main limitation to our study was a paucity of published literature that satisfied the inclusion criteria. Hence, we included studies from countries without universal health coverage, creating a lack of homogeneity.

Heterogeneity in the total number of RFEs precluded the formulation of a common RFE listing. Such a list would require consideration of the frequency of RFEs reported and their individual rankings within the studies. A table comparing the top RFEs of the five physician-reported studies and 11 patient-reported studies was generated. There is the possibility of selection bias due to the selective availability of published data in the studies included. This review derived strength from the comprehensive search strategy adopted for identification of the included studies and application of a robust method of evidence synthesis. This review compared the differences between the RFE data for clinicians versus patient-reported data and the ICPC-2 chapters commonly reported. Data on the leading RFEs can be used to improve health care services and outcomes.

Comparison with other studies

A comparative Danish study, showing change over 16 years in RFE, found that general (23.8%), musculoskeletal (14.3%), respiratory (9.9%), psychological (8.6%), and skin (8.3%) reasons generally did not change over this period and were still the most common reasons for visits.[18] Respiratory (23.9%), general/unspecified (21.8%), and skin (16.4%) reasons were also found to be the main RFEs in an Australian study.[19]

A systematic review in 2018 comparably determined that the most common RFEs were dominated by symptomatic conditions with cough being equivalently ranked the most common patient-reported RFE.[20] URTI and hypertension were ranked the two most common physician-reported RFEs. Similarly, in our review, patients reported symptomatic conditions like cough, fever, abdominal pain, general symptoms, and headache [refer to results- Table 2] most commonly. The physicians reported that hypertension was the most common diagnosis followed by diabetes and URTI [refer to results- Table 2]. Our data highlight that patients more commonly visit primary care for symptomatic reasons, while the diagnoses made are more commonly chronic non-communicable diseases.

Table 2.

Comparison of the ranking of the first 6 Patient Reported RFEs from 11 studies and Physician Reported RFEs from 5 studies showing only the first 10 RFEs.

| RANK # | Patient Reported RFEs | AVERAGE RANK | Frequency in the 11 Studies(out of 11) | RANK # | Physican Reported RFEs | AVERAGE RANK | Frequency in the 5 Studies (out of 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cough | 2.09 | 4 | 1 | Hypertension* | 5.8 | 5 |

| 2 | Fever | 1.64 | 5 | 2 | Diabetes | 2.2 | 4 |

| 3 | Medical Script/request/renewal/inject | 1 | 2 | 3 | Upper respiratory Tract Infection | 2 | 4 |

| 3 | Health maintenance/prevention | 1 | 3 | 4 | Hypertension complicated* | 1.4 | 2 |

| 3 | Gastro-intestinal disease | 1 | 2 | 5 | Malaria | 1.2 | 1 |

| 4 | Abdominal Pain | 0.73 | 3 | 6 | Allergic Rhinitis | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | Preventative Immunisation | 0.73 | 2 | 6 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | Malaria | 0.73 | 2 | 7 | Visual disturbance/other | 0.8 | 1 |

| 5 | General symptom | 0.64 | 2 | 7 | Lipid Disorder | 0.8 | 2 |

| 6 | Headache | 0.55 | 1 | 8 | Acute Bronchitis/Bronchiolitis | 0.6 | 1 |

Hypertension*- includes Hypertension complicated in Lui et al. 2017. K86/K87*- ICPC-2 code in Lui et al. 2017 included both Hypertension complicated and uncomplicated, however all other studies only coded for hypertension uncomplicated. Hypertension Complicated*- In addition to being reported in Olagundoye et al. 2016, both hypertension* and hypertension complicated were ranked together in Lui et al. 2017.

Comparatively, a Canadian cross-sectional study examined the changes in the top 25 reasons for primary care visits during the COVID-19 pandemic.[21] It revealed that anxiety, diabetes, and hypertension remained the top three reasons for the visits both pre-pandemic and during the pandemic. These findings intersect with the top two physician-reported RFEs of hypertension and diabetes in this review, suggesting that non-communicable lifestyle diseases continue to make up a significant percentage of RFEs.

Implications of the review for research

Our findings indicate the need for more far-reaching PHC studies, as little literature exists on this topic within the Caribbean. Future research should aim to develop locally relevant, reliable criteria, and standards to compare performance to patient views and identify quality gaps. This review is narrative but a meta-analysis on this research scope would be essential to gaining a greater insight for effective policy changes and recommendations.

Implications for the health care system and policymaker

The top patient RFEs being URTIs and cold and flu is evidence of the need for more robust patient education on proper hand hygiene and seasonal flu vaccination which can decrease the burden on the health care system. The top physician-reported RFEs included non-communicable lifestyle diseases such as hypertension and diabetes. According to an article by the Trinidad Guardian entitled ‘Govt spends millions to treat diabetics in T&T’ (2018), the government spent “$296 million on diabetics in 2007.”[22] A 2010 report by Dr Kenwyn Nicholls entitled “The Diabetes Epidemic in T&T” found that between 102,000 and 145,000 people were suffering from diabetes. Additionally, Trinidad and Tobago are among the 11 caribbean community (CARICOM) nations with high rates of childhood obesity, with 24.9% of the children aged 5–19 being obese or overweight.[23] This reinforces the need for more aggressive prevention campaigns locally aimed at decreasing the prevalence as well as risk factors.

Moreover, primary care physicians are on the frontline of PHC. Patients’ RFEs can influence their health-seeking behaviors. Therefore, understanding the most common RFEs allows the physician to better address and encourage patient compliance to manage these conditions.

Conclusion

This investigation of 15 cross-sectional sectional studies, comprising 11 countries, found several clinical presentations from different broad categories. In the categories mentioned, there was a significant overlap of specific conditions, prompting a thorough analysis of the individual categories. Respiratory and Digestive were the most frequently reported chapters. The physicians most frequently and commonly reported hypertension, whereas, the patients most frequently reported fever while cough was ranked the most common RFE. The study shows the need for focused investigations by primary care researchers into common conditions that burden the region. This study’s findings are important in providing insight on the global comparative analysis of top RFEs presented by the patients to PHC facilities and should have implications for guidance on the equipment, services, and facilities utilized.

Recommendations

Trinidad and Tobago should heed Pan American Health Organization’s (PAHO’s) recommendations on the marketing of food and non-alcoholic beverages to children and implement formal laws prohibiting such advertisements.[24] Front-of-Package Warning Labeling Policy, Laws, and Regulations in the form of mandatory front-of-package nutritional warnings should be used to reduce the demand for and offer of processed and ultra-processed food products.[25]

Improve health education and disease prevention efforts by targeting preventable communicable and non-communicable diseases.

Commission further research to generate a locally relevant list of RFEs which can, in turn, influence policy decisions.

Key Points Summary

This systematic review examined the most common RFEs in PHC. The most common RFEs reported by patients were cough and fever while the most commonly reported RFEs by physicians were hypertension and diabetes. Understanding the most common RFEs is of great importance to the family physicians as it is a blueprint for acquiring the knowledge and skills required to treat the most common health concerns of their clientele.

Disclosures

Ethics

Ethical approval to conduct this study was obtained from the University of the West Indies Ethics Committee on January 30, 2020. [Refer to Supplemental G] Ref: CREC-SA.0093/11/2019.

Data availability statement

N/A.

Key messages

The most common patient’s RFEs were fever and cough.

The most common RFEs reported by physicians were hypertension and diabetes.

The patients visited primary health facilities for symptomatic reasons.

Public education on healthy practices can mitigate the spread of common conditions.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was funded by departmental resources.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Data- Investigating the leading reasons for Primary Health Care encounters and its implications for healthcare in Trinidad and Tobago. A Systematic Review.

Table of Contents:

Title: Page #

Supplemental A: Search Strategy .................................................................................................. 2

Supplemental B: List of included Studies categorized under an RFE category. .......................... 4

Supplemental C: ICPC-2 Coding of RFE Chapters ...................................................................... 6

Supplemental D: ICPC-2 Coding for RFEs ................................................................................... 8

Supplemental E: List of Charts related to the Results and Analysis Section of this Systematic

Review. ........................................................................................................................................... 13

Supplemental F: Letter of Approval of Submission from Principal Research Investigator ...... 18

Supplemental G: Letter of Ethical Approval from UWI ethics committee. ............................... 19

Supplemental H: Similarity Report. ............................................................................................ 20

Supplemental I: PRISMA 2020 Checklist for Systematic Review. .............................................. 22

Supplemental A: Search Strategy

MEDLINE

National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)[Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information; [1988] – [cited 2020 June 01]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

1 ((primary care) OR (primary health care)) OR (medical care) (1,155,789)

2 exp primary health care (1,081)

3 1 AND 2 (1,155,789)

4 ((((((reason*) OR (why)) OR (condition)) OR (cause*)) OR (disorder)) OR (disease*)) OR (illness*) (11,285, 901)

5 ((utilization) OR (visit*)) OR (consultation) (3,877,881)

6 (reasons for encounter) OR (reasons for visit) (17,242)

7 AND 4 AND 5 AND 6

8 ((common) OR (frequen*)) OR (prevalen*) (3,571,781)

9 ((("patient acceptance of health care"[MeSH Terms]) OR ("patient acceptance of health care/statistics and numerical data"[MeSH Terms])) OR ("patient acceptance of health care/epidemiology"[MeSH Terms])) OR ("patient acceptance of health care/trends"[MeSH Terms]) (150,914)

10 7 AND 8 AND 9 (364)

11 7 AND 8 OR 10 (2,543)

CINAHL DATABASE

Searched June 08, 2020.

LILACS DATABASE:

Searched: June, 09 2020.

(primary care OR primary health care OR medical care) AND (reasons OR why OR conditions OR disorder OR disease OR illness) AND (utilization OR visit OR consultation) AND (common OR frequen$ OR prevalen$) (190)

PROQUEST DATABASE:

Searched: June, 09, 2020.

ti("primary health care" AND "primary care") OR ("medical care") AND (reasons OR why OR causes OR conditions OR disorders OR diseases OR illness) AND (utilization OR visits OR consultation) AND (common OR frequen* OR prevalen*) AND "reasons for encounter" AND "reasons for visit" (25)

GOOGLE SCHOLAR:

Searched: June, 09, 2020.

(reasons OR causes) AND (visits OR consultations OR utilization) AND (primary care OR primary health care OR medical care) AND (common OR frequen* OR prevalen*)

Supplemental B: List of included Studies categorized under an RFE category.

Table A1.

List of Studies Included in this systematic review as categorized under three categories for analysis: RFE Chapters, Patient-Reported RFEs and Physician- Reported RFEs.

| RFE Chapters | Patient-Reported RFEs | Physician-Reported RFEs |

|---|---|---|

| A chart review of morbidity patterns among adult patients attending primary care setting in urban Odisha,India: An International Classification of Primary Care experience. | A chart review of morbidity patterns among adult patients attending primary care setting in urban Odisha,India: An International Classification of Primary Care experience. | A chart review of morbidity patterns among adult patients attending primary care setting in urban Odisha,India: An International Classification of Primary Care experience. |

| International Classification of Primary Care -2 Coding of primary care data at the general out patient’s clinic of general hospital, Lagos, Nigeria. | Reasons for encounter by different levels of urgency in out-of-hours emergency primary health care in Norway: a cross sectional study | International Classification of Primary Care -2 Coding of primary care data at the general out patient’s clinic of general hospital, Lagos, Nigeria. |

| 70,489 primary care encounters: retrospective analysis of morbidity at a primary care centre in Ireland | International Classification of Primary Care -2 Coding of primary care data at the general out patient’s clinic of general hospital, Lagos, Nigeria. | Symptoms and medical conditions in 204 912 patients visiting primary health-care practitioners in India: a 1-day point prevalence study (the POSEIDON study) |

| Statistical complexity of reasons for encounter in high users of out of hours primary care: analysis of a national service | 70,489 primary care encounters: retrospective analysis of morbidity at a primary care centre in Ireland | Patient’s Utilization of Primary Care: A Profile of Clinical and Administrative Reasons for Visits in Israel |

| Symptoms and medical conditions in 204 912 patients visiting primary health-care practitioners in India: a 1-day point prevalence study (the POSEIDON study) | Utilization of Primary Health Care Services in Jaba Local Government Area of Kaduna State Nigeria | Reasons for encounter and health problems managed by general practitioners in the rural areas of Beijing, China: A cross-sectional study |

| Cross-sectional study in an out-of-hours primary care centre in northwestern Germany - patient characteristics and the urgency of their treatment | Reasons for encounter and health problems managed by general practitioners in the rural areas of Beijing, China: A cross-sectional study | This has been omitted purposefully |

| Reasons for encounter and health problems managed by general practitioners in the rural areas of Beijing, China: A cross-sectional study | Statistical complexity of reasons for encounter in high users of out of hours primary care: analysis of a national service | |

| This has been omitted purposefully This has been omitted purposefully |

Linking health facility data from young adults aged 18-24 years to longitudinal demographic data | |

| Patient’s Utilization of Primary Care: A Profile of Clinical and Administrative Reasons for Visits in Israel | ||

| Reasons for elderly patients GP visits: results of a cross- sectional study |

Supplemental C: ICPC-2 Coding of RFE Chapters

Table A2.

List of ICPC-2 Coding for ICPC-2 Chapters recorded in systematic review. The ICPC-2 codes in systematic review were the recoded terms used in this study where as the ICPC-2 codes in the Individual Studies were codes that each included study utilized.

| ICPC-2 Code Name Given in this Systematic Review. | ICPC-2 Code Name Given in Individual Studies. |

|---|---|

| General/Unspecified | General, General and Unspecified, General/Unspecified |

| Digestive | Gastrointestinal, Digestive |

| Respiratory | Respiratory |

| Musculoskeletal | Musculoskeletal |

| Cardiovascular | Circulatory, Cardiovascular |

| Neurological | Neurological, Neurology |

| Female Genital | Female Genitalia, Female Genital, Female genital system and breast |

| Male Genital | Male Genitalia, Male Genital, Male Genital System |

| Eye | Eye |

| Skin | Skin |

| Ear | Ear |

| Pregnancy, Childbearing, Family Planning | Pregnancy, Childbearing, Family Planning pregnancy childbirth, family planning |

| Endocrine/Metabolic and Nutritional | Endocrine, Endocrine/Metabolic and Nutritional, Endocrine, Metabolic, Nutritional, |

| Urological | Urology, Urological, Urogenital |

| Psychological | Psychological |

| Blood, Blood Forming Organs and Immune Mechanism | Blood, Blood Forming Organs and Immune Mechanism, Blood, Blood forming organs, Lymphatics, Spleen blood, blood forming organs, spleen |

| Social Problems | Social Problems |

| Process Codes | Process Codes |

Supplemental D: ICPC-2 Coding for RFEs

The following includes the RFEs included in this Systematic Review:

Table A3.

List of the recoded ICPC-2 codes used in this Systematic Review to replace the ICPC-2 terms utilized in the included studies.

| ICPC-2 Code Name Given in this Systematic Review. | ICPC-2 Code. | ICPC-2 Code Name Given in Individual Studies. |

|---|---|---|

| Pain general | A01 | Pain general/ multiple sites Body ache |

| Fever | A03 | Fever Treatment of other fever |

| General Weakness/ Tiredness | A04 | General weakness/tiredness Weakness/Tiredness (general) Weakness and tiredness Fatigue Weakness/Tiredness |

| Chest pain general | A11 | Chest Pain Chest pain/symptom/condition |

| General symptom | A29 | General symptom/complaint other Other noninfectious General Disease NOS General symptom |

| Administrative Procedure | A32 | Administrative Procedure |

| Blood Test | A34 | Blood Test |

| Preventative Immunisation | A44 | Preventive-immunisation/Medication Immunization Preventative Immunisation |

| Medical Script/ request/renewal/inject | A50 | Medical Renewal General/unspecified medicat- script/reqst/renew/inject Medication Medical Script/request/renewal/inject |

| Results/Tests/Procedures | A60 | Results/exams/tests General/unspecified results/tests/procedures Results/Tests/Procedures |

| Tuberculosis | A70 | Tuberculosis |

| Malaria | A73 | Malaria Treatment |

| Viral Disease Other | A77 | Viral Disease |

| No Disease | A97 | Safety No Disease |

| Health maintenance/ prevention | A98 | Blood pressure check up Health maintenance/ prevention |

| Abdominal pain | D01 | Abdominal Pain/ cramp Abdominal pain abdominal pain/cramps general Generalized abdominal pain/cramps |

| Heart Burn | D03 | Heart Burn |

| Gastro-intestinal disease | D70 | Gastrointestinal Tract Gastro-intestinal disease GIT complaints |

| Gastroenteritis presumed infection | D73 | Gastro enteritis presumed |

| Peptic ulcer other | D86 | Peptic Ulcer |

| Stomach function disorder | D87 | Stomach function disorder |

| Shortness of breath/ dyspnea | R02 | Shortness of breath/ dyspnea |

| Cough | R05 | Cough |

| Sneezing/nasal congestion | R07 | Sneezing/nasal congestion |

| Throat Symptoms | R21 | Throat Symptoms Throat symptom/complaint Throat symptom/condition Symptoms/complaint throat |

| Respiratory symptom/ condition | R29 | Respiratory symptom/condition Respiratory Symptom |

| Upper respiratory tract Infection | R74 | Upper respiratory tract Upper respiratory Infection |

| Laryngitis/tracheitis | R77 | Laryngitis/tracheitis |

| Pneumonia | R81 | Lower respiratory tract infections/pneumonia |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | R95 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| Allergic Rhinitis | R97 | Allergic Rhinitis |

| Back and neck complaint | L01,L02 | Back and neck problems Neck/back symptom/condition |

| Back complaint | L02 | Back complaint Back Symptom Chronic Back Ache Back symptom/complaint Back symptoms/complaints |

| Lower Back Symptoms | L03 | LBA Symptoms Low back complaint excluding radiation |

| Shoulder complaint | L08 | Shoulder Symptoms Shoulder symptoms/complaints |

| Lower Limbs Complaint | L14 | Leg/thigh symptom/complaint Leg/thigh symptoms/complaints Lower limbs symptom/injury/condition Orthopedic complaints pertaining to limbs |

| Knee Complaint | L15 | Knee Symptoms Knee symptoms/complaints |

| Muscle Pain | L18 | Muscle Pain |

| Osteoarthritis other | L89,L90, L91 | Arthritis/joint swellings Arthritis Osteoarthrites* |

| Osteoporosis | L95 | Osteoporosis |

| Prescription refill for hypertension | K50 | Prescription refill for hypertension |

| Ischemic Heart disease* | K76,K77 | Ischemic Heart disease Ischemic Heart Disease with and without Angina |

| Ischemic Heart disease | K76 | Ischemic Heart disease |

| Congestive heart failure | K77 | Congestive heart failure |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | K78 | Atrial fibrillation/flutter |

| Hypertension | K86 | Hypertension uncomplicated Hypertension |

| Hypertension* | K86,K87 | Hypertension* (both Hypertension uncomplicated and Hypertension complicated) |

| Hypertension complicated | K87 | Hypertension complicated |

| Cerebrovascular disease* | K89,K90, K91 | Cerebrovascular disease* |

| Headache | N01 | Head/face symptom/condition Headache Headache (excluding n02 n89 r09) |

| Vertigo/Dizziness | N17 | Vertigo/Dizziness Vertigo/dizziness (excluding h82) |

| Family Planning | Y14 | Family Planning |

| Visual disturbance/other | F05 | visual disturbance/other Visual impairment |

| Eye problems | F29 | Eye problems |

| Conjunctivitis Infectious | F70 | Conjunctivitis Infectious |

| Refractive Error | F91 | Refractive Error |

| Ear, Nose and Throat | H29,R06, R21 | Ear, Nose and Throat |

| Pregnancy | W78 | Pregnancy |

| Diabetes | T90,T89,W85 | Diabetes |

| Prescription refill for diabetes | T50 | Prescription refill for diabetes |

| Hypothyroidism | T86 | Hypothyroidism |

| Lipid Disorder | T93 | Lipid disorder Dyslipidemia |

| Skin itching/rash | S07 | Skin itching/rash |

| Skin Problems | S29 | Skin problems Skin Symptom Skin symptom/complaint other |

| Skin Infection Other | S76 | Skin Infection |

| Dermatitis/atopic eczema | S87 | Eczema |

| Cystitis/urinary infection other | U71 | Cystitis/urinary infection other Urinary tract infection |

| Depression | P76 | Depression |

| Anemia | B80 | Anemia Anaemia other/unspecified |

Supplemental E: List of Charts related to the Results and Analysis Section of this Systematic Review.

Figure A1 (395.1KB, tif) : The Frequency of RFE Chapters included in the 7 studies which utilized RFE Chapters to categorize the most common RFEs.

The Frequency of RFE Chapters reported in 7 included studies. Note that Respiratory and Digestive Chapters are the most frequent ICPC-2 Chapters reported in the studies included this data as they were reported in all 7 included studies.

Table A4: Ranking of the RFE chapters in the 7 studies which were utilized.

Table A4.

Ranking of RFE Chapters reported in 7 included studies. General/Unspecified was the most frequently ranked as the most common RFE Chapter, followed by Respiratory and Skin.

| Swain et al. 2017 | Olaprndoye et al. 2016 | Molony et al. 2015 | Salvi et al. 2015 | Seeger et al. 2019 | Meynard et al. 2015 | Liu et al. 2017 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFE Chapters | RANK | RFE Chapters | RANK | RFE Chapters | RANK | RFE Chapters | RANK | RFE Chapters | RANK | RFE Chapters | RANK | RFE Chapters | RANK |

| General/Unspecified | 1 | General/Unspecified | 1 | General/Unspecified | 1 | Respiratory | 1 | Skin | 1 | General/Unspecified | 1 | Respiratory | 1 |

| Digestive | 2 | Eye | 2 | Respiratory | 2 | Digestive | 2 | Musculoskeletal | 2 | Respiratory | 2 | Cardiovascular | 2 |

| Musculokeletal | 3 | Neurological | 3 | Musculoskeletal | 3 | Cardiovascular | 3 | Respiratory | 3 | Musculokeletal | 3 | Musculoskeletal | 3 |

| Neurological | 4 | Digestive | 4 | Skin | 4 | Skin | 4 | Digestive | 4 | Psychological | 4 | Nutritional | 4 |

| Respiratory | 5 | Musculoskeletal | 4 | Digestive | 5 | Nutritional | 5 | Urological | 5 | Skin | 5 | Digestive | 5 |

| Female Genital | 6 | Respiratory | 5 | Psychological | 6 | Blood. Blood foiming organs, Lymphatics, Spleen | 6 | Process codes | 6 | Digestive | 6 | General/unspecified | 6 |

Table A5: Comparison of ranking of 11 studies which were utilized Patient-Reported RFEs.

Table A5.

Ranking of the most common Patient Reported RFEs among 11 included studies. Cough was the most frequently ranked as the most common RFE by Patients. Patients reported frequently RFEs as symptoms experienced

| Top 6 Ranked Most Common Patient Reported RFEs Among 11 Studies | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swain et al. 2017 | Olagundoye et al. 2016 | Molony et al. 2015 | Otovwe and Elizabeth 2017 | Chueiri et al. 2020 | Liu et al. 2017 | ||||||

| Patient Reported RFE | Rank | Patient Reported RFE | Rank | Patient Reported RFE | Rank | Patient Reported RFE | Rank | Patient Reported RFE | Rank | Patient Reported RFE | Rank |

| Fever | 1 | Headache | 1 | Medical Script/ request/renewal/inject | 1 | Preventative Immunisation | 1 | Results/Tests/Pro cedures | 1 | Cough | 1 |

| Heart Burn | 2 | Fever | 2 | Cough | 2 | Malaria | 2 | Medical Script/ request/renewal/inject | 2 | Prescription refill for hypertension | 2 |

| Vertigo /Dizziness | 3 | Pain general | 3 | Health maintenance/ prevention | 3 | Fever | 3 | Health maintenance/ prevention | 3 | Throat symptoms | 3 |

| Muscle Pain | 4 | Visual disturbance | 4 | Blood Test | 4 | Health maintenance/ prevention | 4 | Pregnancy | 4 | Prescription refill for diabetes | 4 |

| Lower Back Symptoms | 5 | Abdominal pain | 5 | Preventative Immunisation | 5 | Pregnancy | 5 | Hypertension | 5 | Sneezing/nasal congestion | 5 |

| General Weakness/ Tiredness | 6 | Cough | 6 | Administrative Procedure | 6 | Family Planning | 6 | Back complaint | 6 | Fever | 6 |

| Nvundo et al. 2020 | Adar et al. 2017 | Frese et al. 2016 | Stegiak et al. 2019 | Raknes and Hunskaar. 2017 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Reported RFE | Rank | Patient Reported RFE | Rank | Patient Reported RFE | Rank | Patient Reported RFE | Rank | Patient Reporter RFE | Rank |

| Pregancy | 1 | Upper respiratory tract Infection | 1 | Cough | 1 | GastiD-intesiinal disease | 1 | Respiratory symptom/ condition | 1 |

| Family planning | 2 | Gastrointestinal diseas | 2 | Back complaint | 2 | Ear. Nose and Throat | 2 | General symptom | 2 |

| Respiratory infection | 3 | Back and neck com plair | 3 | Shoulder com plaint | 3 | Musculoskeletal complaint other | 3 | Abdominal pain | 3 |

| Malaria | 4 | Skin problems | 4 | Knee complaints | 4 | Chest Pain general | 4 | Lower Limbs Complaint | 4 |

| General symptom | 5 | Abdominal pain | 5 | Shortness of breath/ dyspnea | 5 | No disease | 5 | Chest pain general | 5 |

| Skin problems | 6 | Lower Limbs Complaint | 5 | General Weakness/ Tiredness | 6 | Neurological Symptom Other | 6 | Fever | 5 |

Figure A2 (608KB, tif) : Pie chart showing the ICPC-2 Chapters that account for the Patientreported RFEs.

Patient Reported RFEs further categorized as ICPC-2 Chapters. The most common ICPC-2 Chapter as reported by patients were General/Unspecified, followed by Musculoskeletal and Respiratory Chapters.

Table A6: Ranking of Physician-reported RFEs utilized in 5 Studies.

Table A6.

Ranking of Physician Reported RFEs from 5 included studies. Hypertension was most frequently ranked by physicians as the most common RFE. Note that physicians reported RFEs as diagnoses.

| Top 10 Ranked Most Common Physician Reported RFE Among 5 Studies | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swain et al. 2017 | Olagundoye et al. 2016 | Sahi et al. 2015 | Adar et al. 2017 | Liu et al. 2017 | |||||

| Physician Reported RFE | RANK | Physician Reported RFE | RANK | Physician Reported RFE | RANK | Physician Reported RFE | RANK | Physician Repo | RANK |

| Hypertension | 1 | Malaria | 1 | Hypertension | 1 | Hypertension | 1 | Hypertension* | 1 |

| Allergic Rhinitis | 2 | Hypertension | 2 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2 | Diabetes | 2 | Upper respirator | 2 |

| Upper respirator)’ Tract Infection | 3 | Visual disturbance, other | 3 | Upper respirator}’ Tract Infection | 3 | Uipid Disorder | 3 | Diabetes | 3 |

| Acute Bronchitis, Bronchiolitis | 4 | Peptic ulcer other | 4 | Anaemia | 4 | Hypothyroidism | 4 | Ischaemic heart disease* | 4 |

| Viral Disease Other | 5 | Upper respirator}" Tract Infection | 5 | Diabetes | 5 | Depression | 5 | Cerebrovascula r disease* | 5 |

| Gastro intestinal disease | 6 | Hypertension complicated | 6 | Pneumonia | 6 | Asthma | 6 | Osteoarthritis* | 6 |

| Diabetes | 7 | Cystitis, urinary infection other | 6 | Osteoarthritis other | 7 | Osteoporosis | 6 | Lipid disorder | 7 |

| Gastroenteritis presumed infection | 8 | General symptoms | 6 | Dermatitis, atopic eczema | 8 | Ischemic Heart disease | 7 | No disease | 8 |

| Skin Infection Other | 9 | Conjunctivitis Infectious | 7 | Skin itching, rash | 9 | Atrial fibrillation flutter | 7 | Stomach function disorder | 9 |

| Cystitis, urinary infection other | 9 | Refractive error | 7 | Tuberculosis | 10 | Congestive heart failure | 7 | Laryngitis;trach eitis | 10 |

*- Includes all ICPC-2 codes related to the RFE.

Figure A3 (532.8KB, tif) : ICPC-2 Chapters that account for the Physician-Reported RFEs.

Physician Reported RFEs further categorized as ICPC-2 Chapters. Overall, Physicians diagnosed Respiratory as the most common ICPC-2 chapter followed by Cardiovascular.

Supplemental F: Letter of Approval of Submission from Principal

Research Investigator.

Supplemental G: Letter of Ethical Approval from UWI ethics committee.

Supplemental H: Similarity Report.

Supplemental I: PRISMA 2020 Checklist for Systematic Review.

PRISMA 2020 Checklist for Investigating the leading reasons for Primary Health Care encounters and its implications for healthcare in Trinidad and Tobago. A Systematic Review.

| Section and Topic | Item # | Checklist item | Location where item is reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE | Pg. 1 | ||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. | Pg. 2,3 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | Pg. 4 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | Pg. 4,5 |

| METHODS | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | Pg. 6,7 |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | Pg. 6 |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. | Pg. 6 |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Pg. 6,7 |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Pg. 7,8,9 |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g. for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | Pg. 7,8,9 |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g. participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | Pg. 8,9 | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Pg. 9 |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g. risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | N/A |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g. tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). | Pg. 6 |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. | Pg. 7,8 | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | Pg. 8 | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | Pg. 7,8. | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g. subgroup analysis, meta-regression). | N/A | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results. | N/A | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | Pg. 9 |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | Pg. 8 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. | Pg. 10 |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | Pg. 10 | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | Pg. 11 |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | Pg. 11 |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | Pg. 11, 12, 13 |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | Pg. 11, 1314 |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | Pg. 14-20 | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | Pg. 13,14 | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | N/A | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | Pg. 13,14 |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | N/A |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | Pg. 21, 22 |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | Pg. 22, 23, 24 | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | Pg. 22, 23, 24 | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | Pg. 24, 25, 26 | |

| OTHER INFORMATION | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | N/A |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | N/A | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | N/A | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | Pg. 28 |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | Pg. 29 |

| Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. | Pg. 29 |

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

References

- 1.olde Hartman TC, van Ravesteijn H, Lucassen P, van Boven K, van Weel-Baumgarten E, van Weel C. Why the 'reason for encounter'should be incorporated in the analysis of outcome of care. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e839–41. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X613269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh H, Mustapha N, Haqq ED. Patient satisfaction at health centers in Trinidad and Tobago. Public Health. 1996;110:251–5. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3506(96)80112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adar T, Levkovich I, Castel OC, Karkabi K. Patient's utilization of primary care: A profile of clinical and administrative reasons for visits in Israel. J Prim Care Community Health. 2017;8:221–7. doi: 10.1177/2150131917734473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chueiri PS, Gonçalves MR, Hauser L, Wollmann L, Mengue SS, Roman R, et al. Reasons for encounter in primary health care in Brazil. Fam Pract. 2020;37:648–54. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmaa029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frese T, Mahlmeister J, Deutsch T, Sandholzer H. Reasons for elderly patients GP visits: Results of a cross-sectional study. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:127–32. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S88354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Y, Chen C, Jin G, Zhao Y, Chen L, Du J, Lu X. Reasons for encounter and health problems managed by general practitioners in the rural areas of Beijing, China: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0190036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meynard A, Broers B, Lefebvre D, Narring F, Haller DM. Reasons for encounter in young people consulting a family doctor in the French speaking part of Switzerland: A cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:159. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0375-x. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0375-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molony D, Beame C, Behan W, Crowley J, Dennehy T, Quinlan M, et al. 70,489 primary care encounters: Retrospective analysis of morbidity at a primary care center in Ireland. Ir J Med Sci. 2016;185:805–11. doi: 10.1007/s11845-015-1367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nyundo C, Doyle AM, Walumbe D, Otiende M, Kinuthia M, Amadi D, et al. Linking health facility data from young adults aged 18-24 years to longitudinal demographic data: Experience from The Kilifi health and demographic surveillance system. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;2:51. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.11302.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olagundoye OA, van Boven K, van Weel C. International classification of primary care-2 coding of primary care data at the general out-patients'clinic of General Hospital, Lagos, Nigeria. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016;5:291–7. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.192341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otovwe A, Elizabeth S. Utilization of primary health care services in Jaba Local Government Area of Kaduna State Nigeria. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2017;27:339–50. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v27i4.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pati S, Swain S, Metsemakers J, Knottnerus JA, van den Akker M. Pattern and severity of multimorbidity among patients attending primary care settings in Odisha, India. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raknes G, Hunskaar S. Reasons for encounter by different levels of urgency in out-of-hours emergency primary health care in Norway: A cross-sectional study. BMC Emerg Med. 2017;17:19. doi: 10.1186/s12873-017-0129-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salvi S, Apte K, Madas S, Barne M, Chhowala S, Sethi T, et al. Symptoms and medical conditions in 204?912 patients visiting primary health care practitioners in India: A 1-day point prevalence study (the POSEIDON study) Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e776–84. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seeger I, Kreienmeyer L, Hoffmann F, Freitag MH. Cross-sectional study in an out-of-hours primary care center in northwestern Germany-patient characteristics and the urgency of their treatment. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20:41. doi: 10.1186/s12875-019-0929-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stegink S, Elliott AM, Burton C. Statistical complexity of reasons for encounter in high users of out of hours primary care: Analysis of a national service. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:108. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-3938-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swain S, Pati S, Pati S. A chart review of morbidity patterns among adult patients attending primary care setting in urban Odisha, India: An international classification of primary care experience. J Family Med Prim Care. 2017;6:316–22. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.220029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moth G, Olesen F, Vedsted P. Reasons for encounter and disease patterns in Danish primary care: Changes over 16 years. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2012;30:70–5. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2012.679230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon M, Henderson K, Tapley A, Scott J, Thomson A, Spike N, et al. Problems managed by Australian general practice trainees: Results from the ReCenT (Registrar clinical encounters in training) study. Educ Prim Care. 2014;25:140–8. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2014.11494264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finley CR, Chan DS, Garrison S, Korownyk C, Kolber MR, Campbell S, et al. What are the most common conditions in primary care? Systematic review. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:832–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stephenson E, Butt DA, Gronsbell J, Ji C, O'Neill B, Crampton N, et al. Changes in the top 25 reasons for primary care visits during the COVID-19 pandemic in a high-COVID region of Canada. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0255992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paul, Anna-Lisa Govt spends millions to treat diabetics in T&T. The Trinidad and Tobago Guardian. Nov 11, 2018. Available from: https://www.guardian.co.tt/news/govt-spends-millions-to-treat-diabetics-in-tt-6.2.711572.d81f490222 .

- 23.Nicholls K. The diabetes epidemic in Trinidad &Tobago: Attacking a burdensome disease with conventional weapons. White paper. 2010. Available from: http://www.docs-archive.com/view/766d00e5c7c28db89294aa2d77764114/THE-DIABETES-EPIDEMIC-IN-TRINIDAD-%26-TOBAGO.pdf .

- 24.Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Recommendations from a Pan American Health Organization Expert Consultation on the Marketing of Food and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children in the Americas. Iris Paho [Serial on the Internet] 2011. [Last accessed on 2021 Dec]. ISBN 978-92-75-11638-8. Available from: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/3594 .

- 25.Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Front of Packaging Labeling: As a policy tool for the prevention of non-communicable diseases in the Americas. Iris Paho [Serial on the Internet]. 2020 Sep. PAHO/NMH/RF/20-0033. [Last accessed on 2021 Dec]. Available from: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/52740 .

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The Frequency of RFE Chapters reported in 7 included studies. Note that Respiratory and Digestive Chapters are the most frequent ICPC-2 Chapters reported in the studies included this data as they were reported in all 7 included studies.

Patient Reported RFEs further categorized as ICPC-2 Chapters. The most common ICPC-2 Chapter as reported by patients were General/Unspecified, followed by Musculoskeletal and Respiratory Chapters.

Physician Reported RFEs further categorized as ICPC-2 Chapters. Overall, Physicians diagnosed Respiratory as the most common ICPC-2 chapter followed by Cardiovascular.

Data Availability Statement

N/A.