Abstract

Background:

Disease burden in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) is difficult to estimate. We evaluated whether peritoneal cell-free tumor DNA can be used as a measure of disease burden.

Methods:

Malignant ascites or peritoneal lavage fluids were collected from patients with PC under approved IRB protocol. Cell-free DNA was extracted from peritoneal fluid. Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) was performed using a commercially available KRAS G12/G13 screening kit. Mutant allele frequency (MAF) was calculated based on the numbers of KRAS wild-type and mutant droplets. Clinicopathological, treatment and outcome data were abstracted and correlated with MAF of cell-free KRAS mutant DNA.

Results:

Cell-free KRAS mutant DNA was detected in 15/37 (40%) malignant peritoneal fluids with a MAF of 0.1% to 26.2%. While peritoneal cell-free KRAS mutant DNA was detected in all the patients with KRAS mutant tumors (N=10), 3/16 (19%) patients with KRAS wild-type tumors also had peritoneal cell-free KRAS mutant DNA. We also found that 71% (5/7) of patients with disease amenable to cytoreductive surgery (CRS) had a MAF of < 1% (median: 0.5%, range: 0.1-4.7%), while 75% (6/8) of patients with unresectable disease had a MAF of > 1% (median: 4.4%, range: 0.1-26.2%).

Conclusions:

This pilot proof-of-principle study suggests that peritoneal cell-free tumor DNA detected by ddPCR may enable prediction of disease burden and a measure of disease amenable to CRS in patients with PC.

Keywords: Cell-free tumor DNA, Droplet digital PCR, KRAS mutation, Peritoneal carcinomatosis, Peritoneal carcinomatosis index score

Introduction

Peritoneal carcinomatosis is associated with poor prognosis and shortened long-term survival. It is challenging to estimate the burden of disease in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Most imaging studies underestimate the extent of disease due to limitations in detection of peritoneal disease.1,2 These methods are also not reproducible and lack reliability and inter-rater consistency. Available treatments for peritoneal carcinomatosis include systemic chemotherapy, cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC).

Circulating cell-free tumor DNA (ctDNA) is released from necrotic and apoptotic tumor cells in the body and can be detectable in blood.3-5 ctDNA is increased in many cancers and can provide insights into therapeutic responses to treatments.6-8 Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is the most commonly used platform to detect ctDNA; however, droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) has a greater sensitivity for detection of mutant DNA copies of specific gene and may be more cost effective.9 These methods provide the opportunity for liquid biopsy via a minimally invasive approach to enable detection of tumor-specific mutations.10-12 KRAS mutations are common in many cancers, including metastatic colorectal cancer and pancreatic cancer, and have important prognostic and predictive implications.9,13-16 High quantities of KRAS mutant ctDNA reflects disease burden in some cancers13,15,17,18 and also can provide insights into the mutational landscape in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis.19-21

The goals of this study were to provide pilot data toward testing of the following hypotheses: 1) KRAS mutations can be detected in peritoneal fluids obtained from patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis using ddPCR; 2) high mean allele frequency (MAF) of cell-free KRAS mutant DNA will correlate with high surgical and radiologic peritoneal cancer index (PCI) scores; and 3) high MAF will be associated with nonresectable disease and shortened overall survival.

Materials and Methods

Patient population and sample collection.

Patients with peritoneal surface malignancies were approached and consented under an IRB-approved protocol (Gastrointestinal Molecular Epidemiology Resource, IRB#201202743) at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics between 2016 and 2019. Clinical data including patient demographics, clinicopathological, treatment, and outcome data, were abstracted from the electronic medical records (EMR). Tumor KRAS mutational status was abstracted from pathology reports based on Sanger DNA sequencing methods and tumor molecular profiling data based on NGS methods available on EMR. Malignant ascites fluids were collected using suction device during surgery or percutaneous drainage catheter during ultrasound-guided paracentesis. In patients with minimal ascites fluids, peritoneal lavage was performed and fluid was collected using suction device during surgery after instilling 100-300 ml of sterile saline into the peritoneal cavity during initial surgical exploration.

Radiologic and surgical peritoneal cancer index scoring.

A board-certified radiologist (MR) reviewed computed tomography abdominopelvic scans obtained immediately prior to the fluid collection for radiologic PCI scoring. Surgical PCI score was obtained at the time of the initial operation by a board-certified surgical oncologist (CHFC).22

Sample preparation and droplet digital PCR.

Freshly collected peritoneal fluids were centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C to remove cells and debris. Supernatants were stored at −80°C until use. Cell free DNA was isolated from peritoneal fluids using QIAamp DNA Blood Midi kit (QIAGEN) and quantified using NanoDrop (ThermoFisher). Using the ddPCR™ KRAS G12/13 screening kit (BioRad), 50 ng of DNA was mixed with 10 μl of 2x ddPCR™ Supermix for Probes (no dUTP), 1 μl of 20x multiplex primers/probes (FAM + HEX) and 10 U of MseI for a 20 μl reaction. After vortex thoroughly, 20 μl of the reaction mix was loaded into the sample well of the QX200 Droplet Generator cartridge and mixed with 70 μl of Droplet Generation Oil. Droplets were then generated per manufacturer’s protocol. Droplets were then transferred to a 96-well plate for PCR reaction (10 minutes at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds and annealing/extension at 55°C for 1 minute, and followed by 10 minutes at 98°C). The 96-well plate was then analyzed using QX200 Droplet Reader and the data analyzed using QuantaSoft software. Samples with less than 10,000 droplets generated were excluded for analysis. HEX (KRAS WT) or FAM (KRAS mutant) positive droplets were enumerated. MAF was calculated by FAM-positive droplets/(FAM-positive + HEX-positive droplets) x 100%.

Outcome measures and statistical analysis.

Follow up was the interval between the date of fluid collection and the last date of clinical follow up or death. Associations of MAF with patient survival after fluid collection were assessed with Kaplan Meier curves and log-rank tests. Continuous variables were analyzed using unpaired two-tailed Student t-tests. Linear regression was used for analyzing correlation. P-values > 0.05 were considered significant. Figures and statistical analysis were done using Prism 8 (Graphpad Software).

Results

The mean age of the cohort was 54-years-old (Supplemental Table 1). 57% of the patients were male and 43% were female. 54% (20/37) of patients underwent pre-collection chemotherapy or immunotherapy. 84% (31/37) of patients underwent surgical exploration at the time of peritoneal fluid collection, where 28 of the 31 patients had surgical PCI scores documented. For overall therapy, 49% (18/37) received treatment with chemotherapy alone, and 41% (15/37 patients in each group) had CRS +/− HIPEC, while 11% (4/37) had no treatment. Appendiceal cancer predominated at 41% (15/37), followed by colon cancer primary at 27% (10/37). 57% of patients remained alive and 43% were deceased at median follow up of 5.4 months.

Detection of peritoneal ctDNA in patients with peritoneal surface malignancies.

Of 37 patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis, 26 patients (70%) had tumor KRAS status. Sixteen of them were wild-type; 10 were mutant; 11 were unknown (Supplemental Table 1). We tested whether cell-free KRAS mutant DNA could be detected in the peritoneal fluids in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis using ddPCR. Of these 37 patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis, 40% (15/37) were positive for KRAS mutant DNA in peritoneal fluid while 60% were negative. KRAS mutant DNA was detected in all patients with KRAS tumors (N=10) and in 19% (3/16) with KRAS wild-type tumors (Table 1). Two of 11 tumors with unknown KRAS status were also positive for cell-free KRAS mutant DNA. This finding suggests the presence of tumor heterogeneity.

Table 1:

Patients with positive KRAS mutant ctDNA by ddPCR

| Subject ID |

Age | Sex | Primary Site |

Histology Type1 |

KRAS Status2 |

Surgical PCI3 |

Radiologic PCI4 |

ddPCR MAF (%) |

Pre-collection treatment5 |

Surgery6 | Post-collection treatment5 |

Follow up (Months)7 |

Status at last follow up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI0585 | 56 | F | Colon | AD | WT | 13 | 2 | 0.075 | FOLFIRI | CRS-HIPEC | FOLFOX+Bev | 18.2 | Dead |

| GI0611 | 52 | M | Colon | MAD | G12V | 33 | 10 | 4.350 | None | DL | FOLFOX/FOLFIRI+Bev | 17.2 | Dead |

| GI0701 | 61 | F | Appendix | GCC | G12D | 23 | 0 | 0.512 | None | CRS-HIPEC | FOLFOX+Bev | 25.1 | Alive |

| GI0764 | 63 | M | Appendix | GCC | WT | 29 | 8 | 2.957 | FOLFOX+Bev | CRS-HIPEC | None | 13.3 | Dead |

| GI0767 | 37 | F | Jejunum | AD | G12D | 13 | 6 | 4.680 | CAPOX | CRS-HIPEC | CAPOX+Bev | 19.5 | Alive |

| GI0791 | 62 | F | Colon | AD | G12V | 2 | 4 | 0.101 | 5FU+Bev | CRS | FOLFOX+Bev | 17.0 | Alive |

| GI0812 | 51 | F | Pancreas | MAD | G12D | NA | 9 | 4.593 | None | None | Partial CRS | 4.9 | Dead |

| GI0825 | 54 | M | Appendix | AD-SRC | G12V | NA | 14 | 4.350 | FOLFOX/Cis/Reg | None | None | 1.1 | Dead |

| GI0828 | 69 | M | Pancreas | MAD | UNK | 8 | 12 | 0.327 | None | DL | Gem+Pac+Ascorbate | 4.3 | Alive |

| GI0830 | 64 | F | Pancreas | AD | UNK | NA | 17 | 7.995 | FOLFIRINOX/Gem+Pac | None | None | 0.6 | Dead |

| GI0877 | 59 | M | Unknown | AD | G12V | NA | 10 | 0.112 | FOLFOX | None | None | 1.1 | Dead |

| GI0955 | 40 | F | Ileum | AD | WT | 24 | 12 | 0.163 | FOLFOX+Bev | CRS-HIPEC | Cap/5FU | 4.6 | Alive |

| GI1050 | 60 | F | Pancreas | MAD | G12D | 21 | 16 | 2.735 | None | DL | Gem+Pac/FOLFIRINOX | 5.4 | Dead |

| GI1107 | 47 | F | Colon | AD | G12V | 7 | 1 | 0.725 | FOLFOX | CRS | None | 3.4 | Alive |

| GI1130 | 46 | F | Appendix | MAD | G12D | 39 | 6 | 26.246 | FOLFOX/FOLFIRI/HIPEC | DLI | None | 1.3 | Dead |

AD: Adenocarcinoma, AD-SRC: Adenocarcinoma with signet ring cells, GCC: Goblet cell carcinoma, MAD: Mucinous adenocarcinoma

KRAS Status: Wild-type (WT), mutant (G12V, G12D), unknown (UNK)

Peritoneal Carcinomatosis Index (PCI) during surgical exploration. NA: Not available (for patients without surgery)

Radiologic Peritoneal Carcinomatosis Index (PCI) was estimated using pre-collection CT scans by a board-certified radiologist

Treatment within 6 months of collection. 5FU: 5-Flurouracil; Bev: Bevacizumab; Cap: Capecitabine; CAPOX: Capecitabine, oxaliplatin; Cis: Cisplatin; CRS: Cytoreductive surgery; FOLFIRI: 5FU, leucovorin, irinotecan; FOLFOX: 5FU, leucovorin, oxaliplatin; FOLFIRINOX: 5FU, leucovorin, irinotecan, oxaliplatin; Gem: Gemcitabine; Pac: Nab-Paclitaxel; Reg: Regorafenib.

Surgery at the time of fluid collection. CRS: Cytoreductive surgery; DL: Diagnostic laparoscopy/laparotomy; DLI: Diverting loop ileostomy; HIPEC: Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

Follow up: Time interval between fluid collection and last follow-up or death.

Peritoneal ctDNA correlates with disease burden, but not survival.

We hypothesized that MAF would be associated with higher disease burden. In patients with detectable peritoneal cell-free KRAS mutant DNA, 71% (5/7) of patients with disease amenable to CRS had MAF less than 1%, while 75% (6/8) of patients with unresectable disease had MAF greater than 1% (Table 1). Thus, MAF of less than 1% may predict disease amenable to CRS in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis.

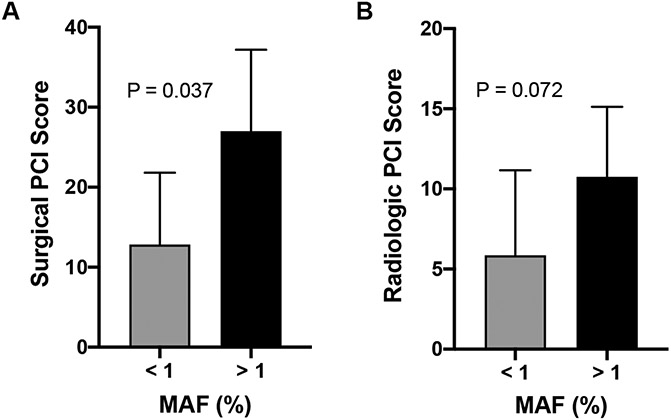

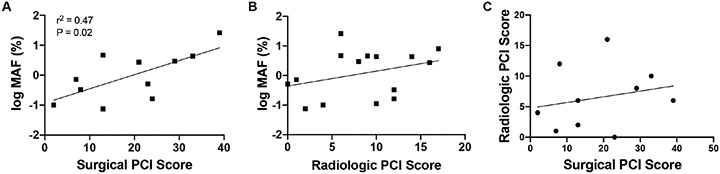

Next, we tested whether a high surgical or radiological PCI score would predict high MAF. Peritoneal malignancies with MAF greater than 1% had a significantly higher surgical PCI score (Mean ± SEM: 27 ± 4.6,) compared to those with MAF of less than 1% (12.8 ± 3.7) (Figure 1a, P=0.037). Radiologic PCI scores trended higher in peritoneal fluids with MAF greater than 1% (10.8 ± 1.5 vs. 5.9 ± 2.0), but did not reach statistical significance (Figure 1b, P=0.072). Additionally, radiologic PCI scores had a more limited range, suggesting potential to underestimate disease burden. Surgical PCI score correlated significantly with MAF and had a moderate positive association (Figure 2a, P=0.02), while radiologic PCI score demonstrated no association or correlation with MAF (Figure 2b). There was also no direct relationship between radiologic and surgical PCI score (Figure 2c). This is not surprising since radiologic PCI tend to underestimate the disease burden in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. This suggests that radiologic PCI score has a limited ability to detect disease burden and thus may not be an accurate measure.

Figure 1: Relationship between MAF and PCI scores.

A) Patients with MAF > 1% had significantly higher surgical PCI scores (27 vs. 13, P = 0.037). B) Patients with MAF > 1% tended to have higher radiological PCI scores (11 vs. 6, P = 0.072).

Figure 2: Correlations between MAF, surgical PCI scores and radiological PCI scores.

A) Correlation between log MAF and surgical PCI scores (R2 = 0.47, P = 0.020). B) Correlation between log MAF and radiological PCI scores (R2 = 0.11, P = 0.225). C) Correlation between surgical and radiological PCI scores (R2 = 0.05, P = 0.536).

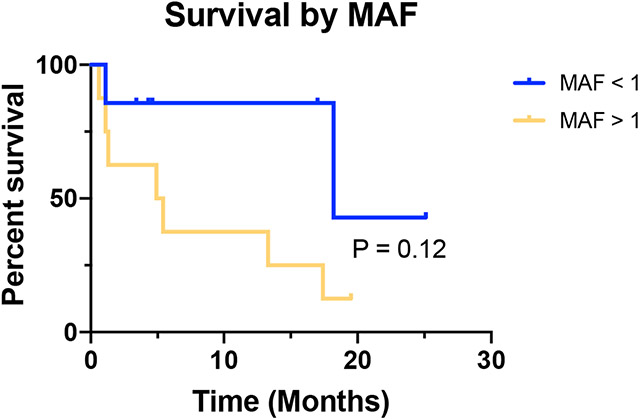

We hypothesized that higher MAF would be associated with worse survival. However, there was no significant effect of MAF on overall survival after peritoneal fluid collection (Figure 3). Notably, our sample size was small and our patient population was very heterogenous. Thus, it is possible that this effect could become significant if more patients with similar disease type were included in our study, since there appears to be a separation between groups by MAF.

Figure 3: Overall survival based on MAF.

Kaplan Meier curves with survival data for MAF greater or less than 1%. Median overall survivals were 18.2 months and 5.2 months for MAF < 1% (blue line) and MAF > 1% (yellow line), respectively (P = 0.12).

Discussion

We have found that cell-free KRAS mutant DNA can be detected in peritoneal fluids and that KRAS wild-type tumors can also have KRAS mutant DNA detected by ddPCR, suggesting tumor heterogeneity that is not detected by tumor DNA sequencing using either Sanger or NGS methods with solid tumor biopsy samples.23,24 Discrepancy between mutational status detected in liquid biopsies compared to tumor biopsies may be due to sampling bias from tumor biopsy or tumor cellularity, while liquid biopsies rely on tumor shedding. In our study, all patients with KRAS mutant tumors had a positive KRAS mutant ctDNA and approximately 20% of patients with KRAS wild-type tumors also had a positive KRAS mutant ctDNA. Thus, ctDNA testing for KRAS mutation in liquid biopsy may be more sensitive to mutational testing than in tumor tissues, as reported in other studies.25,26

Alternatively, the detection of cell-free KRAS mutant DNA in patients with wild-type tumors could also be due to clonal selection after systemic therapy, particularly for patients receiving anti-EGFR therapy, such as panitumumab. In our cohort, 10 of the 16 patients with wild-type KRAS tumor status received systemic therapy, including 2 with panitumumab, 3 with bevacizumab and 1 with pembrolizumab, prior to the testing of peritoneal cell-free DNA for KRAS mutants. While none of the 6 patients without prior chemotherapy had positive KRAS mutant DNA detected by ddPCR, 3 of the 10 patients who received prior systemic therapy including 2 with bevacizumab had mutant KRAS DNA detected in their peritoneal fluid. This finding suggests the theory of clonal selection of the heterogenous tumors with systemic treatment is plausible. A larger cohort with pre- and post-treatment ctDNA testing will however be required to evaluate this hypothesis.

Studies are being undertaken to monitor ctDNA serially as patients undergo therapeutic intervention to better understand the disease state. Interestingly, monitoring of KRAS status in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma during chemotherapy supports increases in MAF concordant to disease burden and longer progression-free survival with loss of KRAS mutant status during chemotherapy.15,27 Similar findings were also present in metastatic colorectal cancer.19 Additionally, mutant KRAS ctDNA may correlate with high numbers of regulatory T cells and poor survival in pancreatic cancer.21

There are multiple methods available to detect ctDNA. ddPCR carries advantages of being more sensitive to detect a specific mutation compared to NGS28 and is more cost effective, but ddPCR is more restricted to specific hotspot mutations. Liquid biopsy and ctDNA testing are less invasive approach to obtain information on tumor disease status than testing a tumor biopsy sample. Furthermore, detection of ctDNA in blood or plasma is believed to have limited sensitivity for patients with isolated peritoneal disease. This is where peritoneal fluid ctDNA may have clinical utility. Most liquid biopsies are performed using serum or plasma which has a short half-life of ctDNA of 2.5 hours;17,29,30 however, ctDNA in peritoneal fluid has a longer half-life and better detection rates.31,32 Thus, peritoneal fluid ctDNA is more likely to reflect the true burden of peritoneal disease. In this study, cell-free KRAS mutant DNA detected by ddPCR in peritoneal fluid may serve as a predictor of disease burden and a measure of disease amenable to CRS in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. MAF obtained from ddPCR correlated with surgical PCI score, and low MAF values were associated with disease amenable to CRS (71% of patients with MAF less than 1% achieved complete cytoreduction and 75% of patients with MAF greater than 1% did not). Thus, peritoneal ctDNA testing may serve as a biomarker to assess disease burden and indicate resectability in peritoneal carcinomatosis. However, ddPCR bears some technical limitations including single-gene testing and genes with limited mutational hotspots. These limitations can be overcome by customizing ctDNA testing based on known tumor mutational profiles, as demonstrated conceptually by other studies.33,34

This study was limited by small sample size and single-institution setting. Another major limitation was the lack of tumor KRAS status in 11 (30%) cases in this study. Two of these “unknown” cases were pancreatic cancers. Obtaining KRAS mutation status or tumor mutation profiling had not been routine during the study period at our institution. These two cases were most likely KRAS mutants since approximately 90% of pancreatic cancer has KRAS mutations.35 The remaining 9 cases either had tissue blocks at outside hospitals or patients were deceased, making requesting tumor KRAS status very difficult. The question on tumor heterogeneity would have been better evaluated if the tumor KRAS mutation status was available for the remaining cases. Also, this pilot study only includes single-gene testing and a single time-point for ctDNA testing. The heterogenous patient population and different pre-collection treatments ultimately had a significant impact on survival analysis. A larger cohort of more homogenous patient population with a more standardized fluid collection method and available surgical PCI scores will be needed to validate the use of peritoneal ctDNA testing. Future studies will also monitor ctDNA using multiple common mutational hotspots of several genes to gain better understanding of the tumor mutational landscape for each patient through the course of various treatments.

Supplementary Material

Synopsis:

Cell-free KRAS mutant DNA can be detected in peritoneal fluids of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis using droplet digital PCR method. Its mutant allele frequency can be a predictive biomarker for peritoneal disease burden.

Acknowledgments:

This study was supported by the Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center through funds from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number P30 CA086862 for supporting the Molecular Epidemiology Resource Core. AGK was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number T35 HL007485. AMM was supported by the National Institutes of Health Free Radical and Radiation Biology T32 CA078586 training grant. HRS was supported by the Iowa Center for Research by Undergraduates Fellowship Awards.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Author PMK: Consultancy/Advisory board (Taiho, Ipsen, Foundation Medicine, Natera); Honoraria (AstraZeneca, Foundation Medicine, Natera). Foundation Medicine, a company focusing on genomics and ctDNA in blood/tissue, is not directly related to the submitted work, but related to ctDNA testing. Natera, a company focusing on ctDNA for stage II/III colorectal cancer, is not directly related to the submitted work, but it is related to the field of liquid biopsies. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.de Bree E, Koops W, Kroger R, van Ruth S, Witkamp AJ, Zoetmulder FA. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal or appendiceal origin: correlation of preoperative CT with intraoperative findings and evaluation of interobserver agreement. J Surg Oncol. 2004;86(2):64–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasqual EM, Bertozzi S, Bacchetti S, et al. Preoperative assessment of peritoneal carcinomatosis in patients undergoing hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy following cytoreductive surgery. Anticancer Res. 2014;34(5):2363–2368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stroun M, Anker P, Lyautey J, Lederrey C, Maurice PA. Isolation and characterization of DNA from the plasma of cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1987;23(6):707–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diehl F, Schmidt K, Choti MA, et al. Circulating mutant DNA to assess tumor dynamics. Nat Med. 2008;14(9):985–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francis G, Stein S. Circulating Cell-Free Tumour DNA in the Management of Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(6):14122–14142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamakawa T, Kukita Y, Kurokawa Y, et al. Monitoring gastric cancer progression with circulating tumour DNA. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(2):352–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murtaza M, Dawson SJ, Tsui DW, et al. Non-invasive analysis of acquired resistance to cancer therapy by sequencing of plasma DNA. Nature. 2013;497(7447):108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawson SJ, Tsui DW, Murtaza M, et al. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA to monitor metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1199–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buscail L, Bournet B, Cordelier P. Role of oncogenic KRAS in the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shoda K, Masuda K, Ichikawa D, et al. HER2 amplification detected in the circulating DNA of patients with gastric cancer: a retrospective pilot study. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18(4):698–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Mattos-Arruda L, Olmos D, Tabernero J. Prognostic and predictive roles for circulating biomarkers in gastrointestinal cancer. Future Oncol. 2011;7(12):1385–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwaederle M, Chattopadhyay R, Kato S, et al. Genomic Alterations in Circulating Tumor DNA from Diverse Cancer Patients Identified by Next-Generation Sequencing. Cancer Res. 2017;77(19):5419–5427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boysen AK, Wettergren Y, Sorensen BS, Taflin H, Gustavson B, Spindler KG. Cell-free DNA levels and correlation to stage and outcome following treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer. Tumour Biol. 2017;39(11):1010428317730976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spindler KL, Pallisgaard N, Andersen RF, Jakobsen A. Changes in mutational status during third-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer--results of consecutive measurement of cell free DNA, KRAS and BRAF in the plasma. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(9):2215–2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perets R, Greenberg O, Shentzer T, et al. Mutant KRAS Circulating Tumor DNA Is an Accurate Tool for Pancreatic Cancer Monitoring. Oncologist. 2018;23(5):566–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hadano N, Murakami Y, Uemura K, et al. Prognostic value of circulating tumour DNA in patients undergoing curative resection for pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(1):59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baumgartner JM, Raymond VM, Lanman RB, et al. Preoperative Circulating Tumor DNA in Patients with Peritoneal Carcinomatosis is an Independent Predictor of Progression-Free Survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(8):2400–2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brychta N, Krahn T, von Ahsen O. Detection of KRAS Mutations in Circulating Tumor DNA by Digital PCR in Early Stages of Pancreatic Cancer. Clin Chem. 2016;62(11):1482–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spindler KL, Pallisgaard N, Vogelius I, Jakobsen A. Quantitative cell-free DNA, KRAS, and BRAF mutations in plasma from patients with metastatic colorectal cancer during treatment with cetuximab and irinotecan. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(4):1177–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan G, Zhang K, Yang X, Ding J, Wang Z, Li J. Prognostic value of circulating tumor DNA in patients with colon cancer: Systematic review. PloS one. 2017;12(2):e0171991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng H, Luo G, Jin K, et al. Kras mutation correlating with circulating regulatory T cells predicts the prognosis of advanced pancreatic cancer patients. Cancer Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Portilla AG, Shigeki K, Dario B, Marcello D. The intraoperative staging systems in the management of peritoneal surface malignancy. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98(4):228–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(10):883–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Normanno N, Rachiglio AM, Lambiase M, et al. Heterogeneity of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA mutations in metastatic colorectal cancer and potential effects on therapy in the CAPRI GOIM trial. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(8):1710–1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sclafani F, Chau I, Cunningham D, et al. KRAS and BRAF mutations in circulating tumour DNA from locally advanced rectal cancer. Scientific reports. 2018;8(1):1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watanabe F, Suzuki K, Tamaki S, et al. Longitudinal monitoring of KRAS-mutated circulating tumor DNA enables the prediction of prognosis and therapeutic responses in patients with pancreatic cancer. PloS one. 2019;14(12):e0227366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugimori M, Sugimori K, Tsuchiya H, et al. Quantitative monitoring of circulating tumor DNA in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2020;111(1):266–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demuth C, Spindler KG, Johansen JS, et al. Measuring KRAS Mutations in Circulating Tumor DNA by Droplet Digital PCR and Next-Generation Sequencing. Transl Oncol. 2018;11(5):1220–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung K, Fleischhacker M, Rabien A. Cell-free DNA in the blood as a solid tumor biomarker--a critical appraisal of the literature. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411(21-22):1611–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ako S, Nouso K, Kinugasa H, et al. Utility of serum DNA as a marker for KRAS mutations in pancreatic cancer tissue. Pancreatology. 2017;17(2):285–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swisher EM, Wollan M, Mahtani SM, et al. Tumor-specific p53 sequences in blood and peritoneal fluid of women with epithelial ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3 Pt 1):662–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haupts A, Roth W, Hartmann N. [Liquid biopsy in colorectal cancer : An overview of ctDNA analysis in tumour diagnostics]. Pathologe. 2019;40(Suppl 3):244–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riva F, Bidard FC, Houy A, et al. Patient-Specific Circulating Tumor DNA Detection during Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin Chem. 2017;63(3):691–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galbiati S, Damin F, Ferraro L, et al. Microarray Approach Combined with ddPCR: An Useful Pipeline for the Detection and Quantification of Circulating Tumour dna Mutations. Cells. 2019;8(8):769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pishvaian MJ, Bender RJ, Halverson D, et al. Molecular Profiling of Patients with Pancreatic Cancer: Initial Results from the Know Your Tumor Initiative. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(20):5018–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.