Abstract

Sex as a biological variable appears to contribute to the multifactorial etiology of Alzheimer’s disease. We tested sex-based interactions between cerebrovascular function and APOE4 genotype on resistance and resilience to brain pathology and cognitive executive dysfunction in cognitively-normal older adults. Female APOE4 carriers had higher amyloid-β deposition, yet achieved similar cognitive performance to males and female noncarriers. Further, female APOE4 carriers with robust cerebrovascular responses to exercise possessed lower amyloid-β. These results suggest a unique cognitive resilience and identify cerebrovascular function as a key mechanism for resistance to age-related brain pathology in females with high genetic vulnerability to Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: Cardiovascular system, ultrasound, amyloid, Apolipoproteins E, female, cognition, hemodynamics, cerebrovascular circulation, aging

1. Introduction

The brain’s capacity for resilience (ability to cope) and resistance (ability to avoid) to age-related pathologic changes may explain why some people are less susceptible to the development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related dementia.[1] Older age, ApolipoproteinE e4 (APOE4), and female chromosomal sex are the greatest risk factors for the development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and associated cognitive impairment.[2] Cerebrovascular health is also becoming increasingly recognized as playing a key role in AD and neurodegenerative disease processes leading to age-related brain pathology and cognitive dysfunction, potentially acting to promote resistance to the development of brain pathology.[3–7] Differences in cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome risk as a function of aging and APOE genotype have been documented.[2,8] Additionally, sex plays a key role in cardiovascular disease severity [9] and the risk for cerebrovascular disease, with the female sex showing protective effects throughout most of the lifespan, which may be mediated by the beneficial effects of estrogen on vascular health [10]. Yet, how sex may interact with APOE4 genotype and cerebrovascular health to influence an individual’s resilience and resistance to the development of cognitive dysfunction and brain pathology with aging remains poorly understood. Recently, findings from our laboratory revealed that older adults who carry the APOE4 allele have greater brain amyloid-β deposition,[11] a hallmark of AD,[7] yet those APOE4 carriers who possessed the highest cerebrovascular function achieved the highest levels of cognitive performance on an executive function task.[11] Older adults tend to show a blunted cerebral blood flow response during moderate-intensity aerobic exercise [3,12] that has been linked to poor vascular health and slower cognition.[12] In the present study, we aim to investigate whether sex as a biological variable moderates interactions between APOE4 and cerebrovascular function on brain pathology and cognitive executive function, an early and sensitive indicator of cognitive impairment [13–15], in preclinical older adults. Here we test the central hypothesis that cognitively-normal female older adults who carry the APOE4 allele would have the highest levels of amyloid-β deposition, yet show the strongest positive effect of cerebrovascular function on brain health.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The present study performs a novel analyses in the same well-characterized participant cohort (n=71) reported in Palmer et al (2022), building upon this previous whole dataset analyses [11]. Inclusion criteria were (1)age 65–90 years, (2)clinically normal cognition, and (3)physical ability to exercise. Exclusion criteria were (1)insulin-dependent diabetes, (2)peripheral neuropathy, (3)active coronary artery disease (angina, myocardial infarction) within 2 years, (4)congestive heart failure, (5)the presence of an APOE2 allele(s). The University of Kansas Institutional Review Board approved this protocol (IRB#:STUDY00001444). All participants provided written informed consent.

2.2. Aerobic exercise bout on a recumbent stepper

Transcranial doppler ultrasound (TCD) was used to assess cerebral blood flow during a bout of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise on a recumbent stepper previously described in detail.[11,16–18] Briefly, participants were familiarized with exercise on the recumbent stepper (NuStep T5XR), in which they worked at a resistance load to achieve a target 40–60% age-predicted heart rate reserve.[3,17] TCD was continuously recorded during an 8-minute rest period followed by moderate-intensity exercise, in which the participant maintained steady-state exercise in the target heart rate zone for 8 minutes.

2.3. Cerebrovascular assessment and analyses

Left middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity (MCAv) was recorded using a 2-MHz TCD probe (RobotoC2MD, Multigon Industries). Custom MATLAB software (The Mathworks Inc.) using an analog-to-digital data acquisition unit (NI-USB-6212, National Instruments) acquired MCAv (500 Hz), continuously recorded heart rhythm, mean arterial pressure (Finometer, Finapres Medical Systems), and end tidal CO2 via nasal capnograph (BCI Capnocheck Sleep 9004 Smiths Medical) synchronized across the cardiac cycle.[3,16,17,19] Data were visually inspected and discarded when R-to-R intervals were >5 Hz or changes in peak MCAv exceeded 10 cm/s in a single cardiac cycle. Trials with <85% samples were discarded. Experimenters had no knowledge of Aβ level, cognition, or APOE genotype. Mean MCAv was calculated over the 8-minute rest and 8-minute moderate-intensity exercise bout. Cerebrovascular response (CVR) was quantified as the difference between mean MCAv during exercise and rest conditions.[3] In a large cohort of older adults (n=203), Lake et al. (2022) report an age-typical increase in CVR during moderate-intensity exercise of 4.4cm/s (8.6%) [20], a measure with good day-to-day reproducibility [21]. Our primary paper with this participant cohort reported an intra-trial coefficient of variation for the 8-minute mean MCAv during rest (8.0%) and during the 8 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise (9.1%) [11].

2.4. Structural neuroimaging of amyloid-β (Aβ) deposition

A GE Discovery ST-16 PET/CT scanner was used to obtain Florbetapir PET images at 50 minutes after administration of intravenous florbetapir 18F-AV45 (370 MBq). Two 5-minute PET brain frames were summed and attenuation corrected.[22] Standard procedures were used to determine global Aβ deposition using the global standardized update value ratio (SUVR).[23]

2.5. APOE genotyping

Using whole blood samples and methods described previously,[22,24] individuals were classified as APOE4 carrier in the presence of 1 or 2 APOE4 alleles (i.e. E3/E4, E4/E4) and noncarriers in the presence of 2 APOE3 alleles (i.e. E3/E3). Because APOE2 appears to be neuroprotective and is associated with reduced risk for AD,[25] all individuals who possessed 1 or 2 APOE2 alleles were excluded.

2.6. Demographic and clinical information

All participants completed the Uniform Data Set (UDS) neuropsychological test battery and the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale employed by the United States Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center network[26] consisting of in-person clinical and cognitive testing. CDR testing was performed by a trained clinician and the neuropsychological test battery by a trained psychometrist. A consensus diagnostic conference reviewed and finalized all clinical and cognitive data and participant cognitive status.[27] The present analysis includes only participants who were rated cognitively-normal (i.e.CDR=0). Demographic information, including age, sex, and race (white/non-white) were assessed by participant self-report (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| ALL (n=71) | Female (n=48) | Male (n=23) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 71 ± 5 | 71 ± 6 | 71 ± 5 | p=.987 |

| Race, white (%) | 68 (96%) | 45 (94%) | 23 (100%) | |

| Non-white (%) | 3 (4%) | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| HTN (≥140/90) | 16 | 9 | 7 | |

| HTN medication | (Y) 24 | (Y) 12 | (Y) 11 | |

| Cholesterol (Total, HDL) | 184±24, 32±15 | 200±38, 67±18 | 167±32, 48±12 | |

| ASCVD Risk Score | 17.2±4.9 | 13.7±9.8 | 20.6±8.3 | p=.007 |

| Workload (W/kg) | 0.80±0.27 | 0.74±0.29 | 0.93±0.18 | p=.004 |

| APOE4 carrier | (+) = 21/71 | (+) = 14/48 | (+) = 7/23 | p=.813 |

| Aβ Deposition | 1.09 ± 0.17 [0.86 to 1.6] |

1.09 ± 0.18 [0.86 to 1.6] |

1.1 ± 0.18 [0.92 to 1.6] |

p=.701 |

| CVR | 5.55 ± 5.29 | 5.38 ± 5.54 | 5.87 ± 4.83 | p=.719 |

| Stroop ratio | 0.52 ± 0.12 | 0.51 ± 0.12 | 0.54 ± 0.13 | p=.458 |

Aβ = amyloid-β; CVR = cerebrovascular response to moderate-intensity aerobic exercise; Aβ = amyloid-β; [Range]; W= Watts at moderate intensity exercise workload; kg BW = kilograms of body weight; ASCVD Risk Score= Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Score; (+)=APOE4 carrier; (Y)=Yes; HTN=hypertension. Values are depicted as mean ± SD.

Among 71 total participants, there were no differences between female and male participants in cognitive performance, age, Aβ, proportion of APOE4(+) or CVR (Table 1). As expected, male participants performed exercise at a greater normalized workload compared to females and had a higher ASCVD score.

Cognitive executive function performance

Participants were presented with three conditions: 1) Stroop word reading, where color words were printed in black ink, 2) Stroop color naming, in which rectangular color patches were shown, and 3) Stroop interference, in which participants ignored the word and stated the incongruent color of the ink. The raw number of correct responses was recorded during a 45-second trial for each condition. We calculated response inhibition performance as the Stroop ratio:[28]

2.7. Statistical analyses

Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Levene’s tests tested normality and heterogeneity of variance, respectively. We tested the interactive sex-by-genotype effect on each Aβ and cognitive performance using a two-way analysis of variance. We tested the interactive sex-by-CVR effect on Aβ in each APOE4 carriers and noncarriers using a two-way moderated multiple linear regression analysis. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 27 with an a priori level of significance set to 0.05.

RESULTS

Among 71 total participants (Table 1) complete datasets were available, except one participant did not complete Stroop testing and was excluded from cognitive analyses.

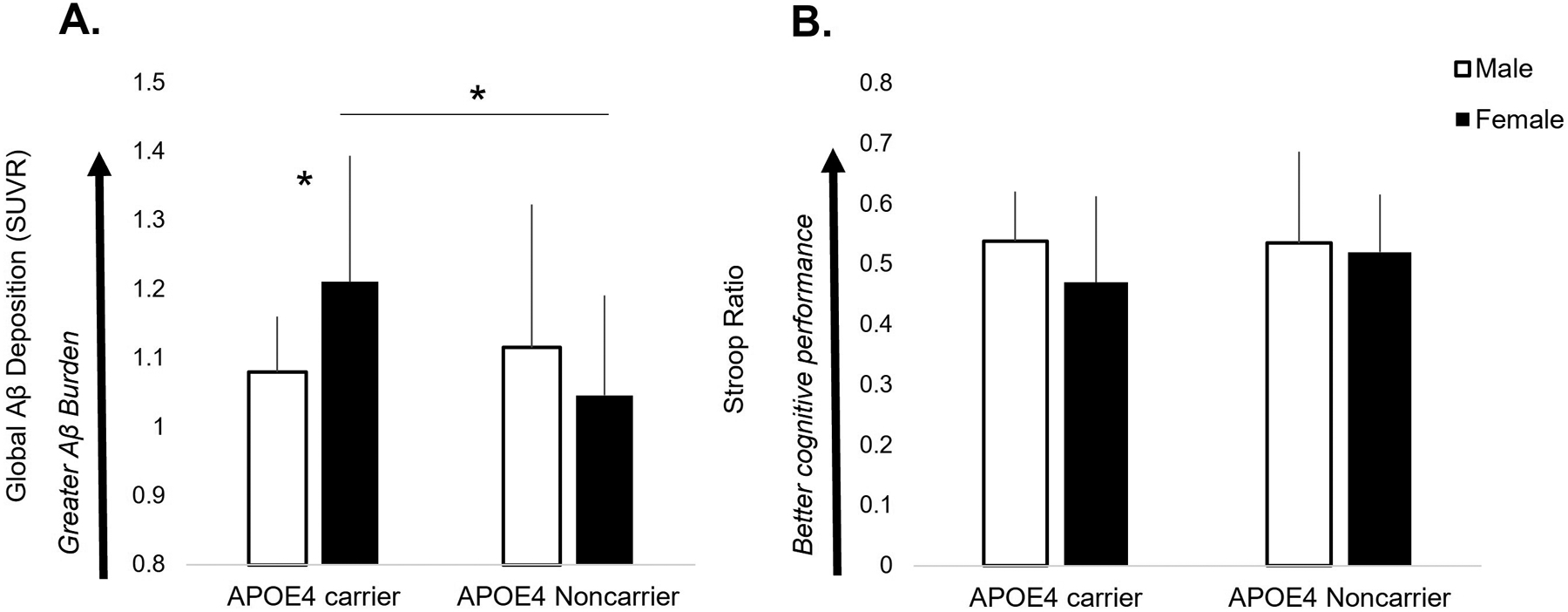

Sex interacts with APOE4 genotype on brain pathology but not cognitive function

The model significantly predicted brain pathology (F3,71=3.34, p=.024), in which there was a sex-by-APOE4 interaction (t= −2.14, p=.036) on Aβ deposition. Post-hoc analysis revealed this interaction was driven by greater Aβ in female APOE4 carriers, who showed greater Aβ compared to male APOE4 carriers (p=.037) and female noncarriers (p=.006) (Figure 1A). No differences were found between male and female noncarriers (p=.225), or between male APOE4 carriers and noncarriers (p=.565).

Figure 1.

Global amyloid-β (Aβ) deposition (A) and cognitive executive function performance (B) in male and female APOE4 carriers and noncarriers. A sex-by-genotype interaction revealed that female APOE4 carriers possessed higher levels of Aβ compared to males (p=.037) and female noncarriers (p=.006) (A). There were no interactive effects or group differences in Stroop ratio, in which all older adult subgroups achieved similar levels of cognitive performance (B).

In contrast, the model did not predict cognitive performance (F3,70=0.95, p=.419), in which we found no interactive sex-by-APOE4 effect (t= 0.83, p=.410) on the Stroop ratio, indicating similar cognitive executive function across male and female participants and APOE4 carrier types (Figure 1B).

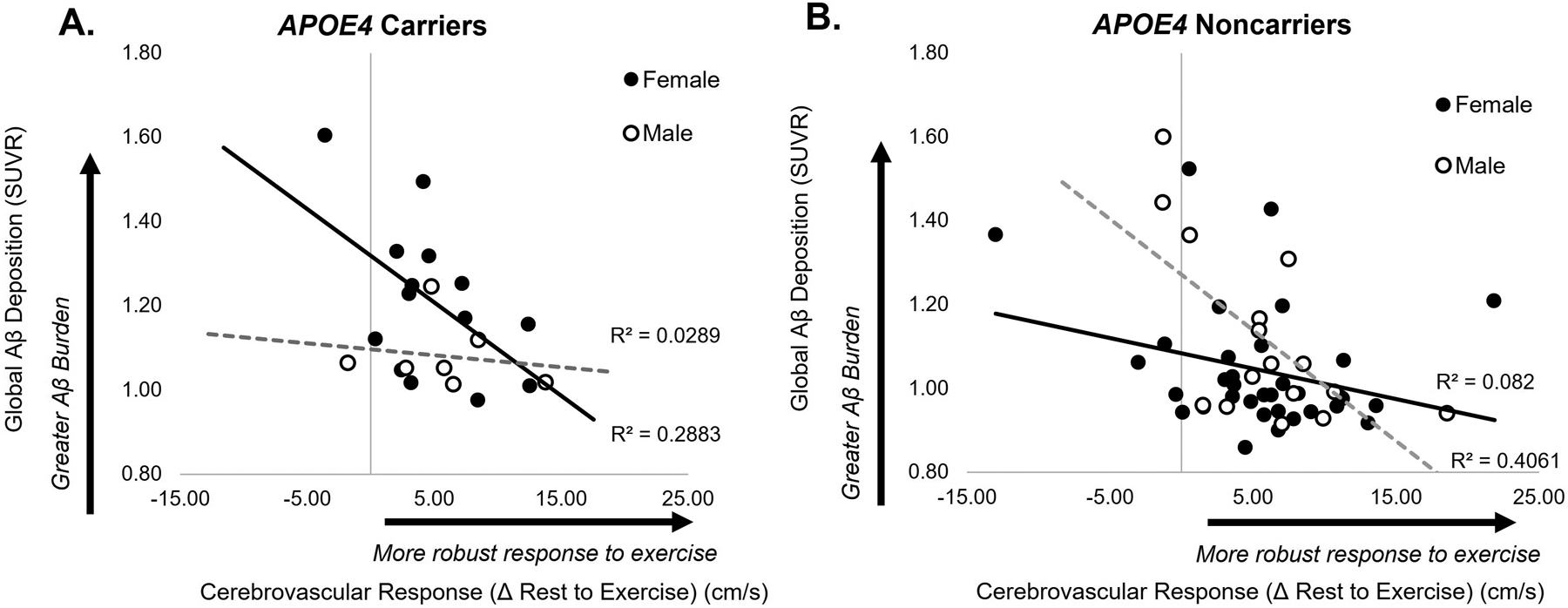

Sex differentially moderates the relationship between CVR and Aβ deposition in APOE4 carriers and noncarriers

The model significantly predicted brain pathology in both APOE4 carriers (F3,20=3.08, p=.043) and noncarriers (F3,49=3.64, p=.017) (Figure 2). In APOE4 carriers, females showed a stronger negative relationship between CVR and Aβ (r=−.54, p=.048) compared to males (r=−.17, p=.716) (Figure 2A), in which females with low CVR had higher Aβ deposition and males showed no effect. In noncarriers, males showed a stronger negative relationship (r=−.64, p=.008) between CVR and Aβ compared to females, who showed a similar pattern that did not reach our a priori level of statistical significance (r=−.29, p=.09) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Association between cerebrovascular response to exercise (CVR) and amyloid-β (Aβ) deposition in APOE4 carriers (A) and noncarriers (B). Higher CVR was associated with lower levels of Aβ deposition in female APOE4 carriers (r=−.54, p=.048), while showing no relationship in male APOE4 carriers (r=−.17, p=.716) (A). Similarly, CVR and Aβ were negatively associated in male noncarriers (r=−.64, p=.008), and showed a similar pattern in female noncarriers (r=−.29, p=.09) (B).

DISCUSSION

Findings of the present study provide initial evidence for a unique resilience to cognitive dysfunction and differential mechanisms of resistance to the development of brain pathology between male and female older adults. Our results suggest that these sex-based differences in brain resilience and resistance are influenced by individual APOE4 genotype and cerebrovascular health. These results shed new light on recent findings from our laboratory that showed a magnified positive effect of cerebrovascular health on Aβ deposition in APOE4 carriers with elevated compared to non-elevated levels of Aβ deposition;[11] here, our results implicate sex as a biological variable contributing to the interactive effect between APOE4 genotype and Aβ deposition in older adult individuals. In the present study we found that, despite possessing higher levels of Aβ compared to males and their female noncarrier counterparts, female APOE4 carriers were able to achieve similar levels of cognitive executive function performance (Figure 1). The ability to effectively cope with elevated levels of Aβ to preserve normal cognition and achieve equal cognitive performance to those with nonelevated Aβ suggests that females who carry the APOE4 allele may possess a unique resilience to cognitive dysfunction with aging.[1] Further, female APOE4 carriers with higher cerebrovascular function possessed lower levels of Aβ (Figure 2A), suggesting that higher cerebrovascular health may contribute to increased resistance to brain pathology in these individuals during the preclinical stages of disease. These initial findings identify cerebrovascular function as a potential target for future precision-based efforts for the preservation of brain health, particularly in female older adults who carry the APOE4 allele and are at high genetic risk for AD.[2]

The differential effect of cerebrovascular function on brain pathology in male and female APOE4 carriers may reveal important information about sex-related bioenergetic differences that influence the role of cerebrovascular health in pathological brain disease processes. The unique “dual reliance” of the APOE4 brain on both glucose and ketone bodies for fuel[29] may be detrimental in the aging female brain post-menopause. Estrogen depletion post-menopause may attenuate glucose metabolism,[30,31] which may be synergistically exacerbated with age-related declines in cardiovascular health and associated metabolic function.[32] In the present study, the negative relationship between CVR and Aβ deposition in female APOE4 carriers (Figure 2A) may support a beneficial compensatory role of cerebrovascular health for resistance to deleterious post-menopausal bioenergetic changes that compound with the dual metabolic reliance of this known risk allele.[29],[33] Given that aerobic exercise can improve both cerebrovascular health[34–36] and glucose metabolic function,[37] findings of this study identify aerobic exercise intervention as a potentially effective strategy to target improved brain health and cognitive function in female older adults who possess this known risk allele during the early preclinical stages of age-related disease processes.

Although not aligned with our a priori hypotheses, male noncarriers demonstrated a similar negative relationship between CVR and Aβ deposition to female APOE4 carriers (Figure 2A). As cerebrovascular function is becoming increasingly recognized in the pathogenesis of AD,[3–7] these results may be consistent with previous studies that have identified an interesting paradox of sex differences in AD risk that appear to be driven, in part, by a sex-by-APOE4 “gene dose” effect.[2] Notably, the lack of relationship between CVR and Aβ in APOE4 carrier males raises the notion that, in the presence of higher genetic cardiovascular risk with this high-risk allele, the positive effects of exercise observed in male noncarriers and female APOE4 carriers who demonstrated a unique exercise-mediated resistance to brain pathology may be attenuated in this male subgroup. Alternatively, differences in structural brain abnormalities (e.g. white matter hyperintensities) between subgroups may illuminate mechanisms underpinning these interesting findings. Here, our results motivate larger future studies to test whether differences in male and female homo- versus heterozygote APOE4 carrier status may explain these interesting subgroup effects of cerebrovascular health on brain pathology.

Limitations

The preliminary nature, small sample size, and limited range of Aβ and CVR in the present study, particularly that of the APOE4 carrier group, is an important consideration and warrants larger mechanistic studies with more robust sample sizes. Generalizability and reproducibility are significantly limited by the underrepresentation of non-white races in the present study due to lower recruitment in these segments of community-dwelling older adults, indicating greater outreach efforts are needed. The present study illuminates differences between Aβ deposition in female and male APOE4 carriers, raising the possibility that relationships between CVR and Aβ in female APOE4 carriers could occur collaterally with elevated Aβ rather than direct effects of sex, as previously described in our detailed analyses of this dataset [11]. Future studies expanding inclusion criteria to include older individuals with cognitive impairment, and potentially greater Aβ deposition, may equalize the differences in levels of Aβ deposition between sexes in the APOE4 carrier group and help to delineate isolated and interactive effects of sex and elevated levels of Aβ. Participants possessed the absence of clinical syndrome and had no presence of stroke or brain pathology; however, participants were not excluded based on other structural MR-abnormalities. Future follow-up analyses utilizing a more sensitive and sophisticated neuroimaging approach could detect other structural brain abnormalities that may elucidate mechanisms contributing to the present results in this preclinical cohort, in particular the relationship between cerebrovascular response to exercise and global Aβ deposition in noncarrier males. Sex differences in ASCVD risk profile [38] are expected, but we cannot rule out that greater ASCVD risk score in male participants may have influenced the results.

CONCLUSION

Our findings provide preliminary evidence for unique mechanisms of resilience to cognitive dysfunction and resistance to brain pathology between male and female older adults. These preliminary findings identify cerebrovascular health as a potential effective target for future precision-medicine approaches to increase resistance to brain pathology and provide resiliency for the preservation of cognitive function in female older adults with high genetic vulnerability to Alzheimer’s disease during the early, preclinical stages of age-related disease processes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development and the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health [P30 AG072973, P30AG035982, R01 AG043962, UL1TR000001], the American Heart Association [16GRNT30450008 (SB)], the Georgia Holland Endowment Fund, the Frank and Evangeline Thompson (JMB), and the Leo and Anne Albert Charitable Trust. Amyloid measurement infrastructure was supported by Ann and Gary Dickinson Family Charitable Foundation, John and Marny Sherman, Brad and Libby Bergman. Partial scan costs were supported by a grant from Lilly Pharmaceuticals. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or any other funding agency.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- [1].Bocancea DI, van Loenhoud AC, Groot C, Barkhof F, van der Flier WM, Ossenkoppele R (2021) Measuring Resilience and Resistance in Aging and Alzheimer Disease Using Residual Methods: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Neurology 97, 474–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Riedel BC, Thompson PM, Brinton RD (2016) Age, APOE and sex: Triad of risk of Alzheimer’s disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 160, 134–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sisante J-FV, Vidoni ED, Kirkendoll K, Ward J, Liu Y, Kwapiszeski S, Maletsky R, Burns JM, Billinger SA (2019) Blunted cerebrovascular response is associated with elevated beta-amyloid. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 39, 89–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lorius N, Locascio JJ, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Viswanathan A, Marshall GA (2015) Vascular disease and risk factors are associated with cognitive decline in the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 29, 18–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Solis E, Hascup KN, Hascup ER (2020) Alzheimer’s Disease: The Link Between Amyloid-β and Neurovascular Dysfunction. J Alzheimers Dis 76, 1179–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sweeney MD, Kisler K, Montagne A, Toga AW, Zlokovic BV (2018) The role of brain vasculature in neurodegenerative disorders. Nature Neuroscience 21, 1318–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zlokovic BV, Deane R, Sallstrom J, Chow N, Miano JM (2005) Neurovascular pathways and Alzheimer amyloid beta-peptide. Brain Pathol 15, 78–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dore GA, Elias MF, Robbins MA, Elias PK, Nagy Z (2009) Presence of the APOE epsilon4 allele modifies the relationship between type 2 diabetes and cognitive performance: the Maine-Syracuse Study. Diabetologia 52, 2551–2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Regitz-Zagrosek V (2006) Therapeutic implications of the gender-specific aspects of cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 5, 425–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Robison LS, Gannon OJ, Salinero AE, Zuloaga KL (2019) Contributions of sex to cerebrovascular function and pathology. Brain Res 1710, 43–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Palmer JA, Kaufman CS, Vidoni ED, Honea RA, Burns JM, Billinger SA (2022) Cerebrovascular response to exercise interacts with individual genotype and amyloid-beta deposition to influence response inhibition with aging. Neurobiology of Aging. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Alwatban MR, Liu Y, Perdomo SJ, Ward JL, Vidoni ED, Burns JM, Billinger SA (2020) TCD Cerebral Hemodynamic Changes during Moderate-Intensity Exercise in Older Adults. Journal of Neuroimaging 30, 76–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hutchison KA, Balota DA, Duchek JM (2010) The Utility of Stroop Task Switching as a Marker for Early Stage Alzheimer’s Disease. Psychol Aging 25, 545–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kirova A-M, Bays RB, Lagalwar S (2015) Working memory and executive function decline across normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. Biomed Res Int 2015, 748212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Coelho FG de M, Stella F, de Andrade LP, Barbieri FA, Santos-Galduróz RF, Gobbi S, Costa JLR, Gobbi LTB (2012) Gait and risk of falls associated with frontal cognitive functions at different stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn 19, 644–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ward JL, Craig JC, Liu Y, Vidoni ED, Maletsky R, Poole DC, Billinger SA (2018) Effect of healthy aging and sex on middle cerebral artery blood velocity dynamics during moderate-intensity exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 315, H492–H501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Billinger SA, Craig JC, Kwapiszeski SJ, Sisante J-FV, Vidoni ED, Maletsky R, Poole DC (2017) Dynamics of middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity during moderate-intensity exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 122, 1125–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Witte E, Liu Y, Ward JL, Kempf KS, Whitaker A, Vidoni ED, Craig JC, Poole DC, Billinger SA (2019) Exercise Intensity and Middle Cerebral Artery Dynamics in Humans. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 262, 32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Perdomo SJ, Ward J, Liu Y, Vidoni ED, Sisante JF, Kirkendoll K, Burns JM, Billinger SA (2020) Cardiovascular disease risk is associated with middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity in older adults. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J 31, 38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lake SL, Guadagni V, Kendall KD, Chadder M, Anderson TJ, Leigh R, Rawling JM, Hogan DB, Hill MD, Poulin MJ (2022) Aerobic exercise training in older men and women-Cerebrovascular responses to submaximal exercise: Results from the Brain in Motion study. Physiol Rep 10, e15158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Weston ME, Barker AR, Tomlinson OW, Coombes JS, Bailey TG, Bond B (2022) The effect of exercise intensity and cardiorespiratory fitness on the kinetic response of middle cerebral artery blood velocity during exercise in adults. Journal of Applied Physiology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Vidoni ED, Morris JK, Watts A, Perry M, Clutton J, Sciver AV, Kamat AS, Mahnken J, Hunt SL, Townley R, Honea R, Shaw AR, Johnson DK, Vacek J, Burns JM (2021) Effect of aerobic exercise on amyloid accumulation in preclinical Alzheimer’s: A 1-year randomized controlled trial. PLOS ONE 16, e0244893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Liu Y, Perdomo SJ, Ward J, Vidoni ED, Sisante JF, Kirkendoll K, Burns JM, Billinger SA Vascular Health is Associated with Amyloid-β in Cognitively Normal Older Adults. J Alzheimers Dis 70, 467–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kaufman CS, Morris JK, Vidoni ED, Burns JM, Billinger SA (2021) Apolipoprotein E4 Moderates the Association Between Vascular Risk Factors and Brain Pathology. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mahley RW (2016) Apolipoprotein E: from cardiovascular disease to neurodegenerative disorders. J Mol Med (Berl) 94, 739–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Monsell SE, Dodge HH, Zhou X-H, Bu Y, Besser LM, Mock C, Hawes SE, Kukull WA, Weintraub S, Neuropsychology Work Group Advisory to the Clinical Task Force (2016) Results From the NACC Uniform Data Set Neuropsychological Battery Crosswalk Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 30, 134–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Graves RS, Mahnken JD, Swerdlow RH, Burns JM, Price C, Amstein B, Hunt SL, Brown L, Adagarla B, Vidoni ED (2015) Open-source, Rapid Reporting of Dementia Evaluations. J Registry Manag 42, 111–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Stroop J (1935) Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol 643–62. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wu L, Zhang X, Zhao L (2018) Human ApoE Isoforms Differentially Modulate Brain Glucose and Ketone Body Metabolism: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease Risk Reduction and Early Intervention. J Neurosci 38, 6665–6681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Klosinski LP, Yao J, Yin F, Fonteh AN, Harrington MG, Christensen TA, Trushina E, Brinton RD (2015) White Matter Lipids as a Ketogenic Fuel Supply in Aging Female Brain: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. EBioMedicine 2, 1888–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mishra A, Wang Y, Yin F, Vitali F, Rodgers KE, Soto M, Mosconi L, Wang T, Brinton RD (2022) A tale of two systems: Lessons learned from female mid-life aging with implications for Alzheimer’s prevention & treatment. Ageing Res Rev 74, 101542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Anderson EJ, Lustig ME, Boyle KE, Woodlief TL, Kane DA, Lin C-T, Price JW, Kang L, Rabinovitch PS, Szeto HH, Houmard JA, Cortright RN, Wasserman DH, Neufer PD (2009) Mitochondrial H2O2 emission and cellular redox state link excess fat intake to insulin resistance in both rodents and humans. J Clin Invest 119, 573–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Heffernan AL, Chidgey C, Peng P, Masters CL, Roberts BR (2016) The Neurobiology and Age-Related Prevalence of the ε4 Allele of Apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s Disease Cohorts. J Mol Neurosci 60, 316–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kaufman Carolyn S., Honea RA, Pleen J, Lepping RJ, Watts A, Morris JK, Billinger SA, Burns JM, Vidoni ED (2021) Aerobic exercise improves hippocampal blood flow for hypertensive Apolipoprotein E4 carriers. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 41, 2026–2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Whitaker AA, Alwatban M, Freemyer A, Perales-Puchalt J, Billinger SA (2020) Effects of high intensity interval exercise on cerebrovascular function: A systematic review. PLOS ONE 15, e0241248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Thomas BP, Yezhuvath US, Tseng BY, Liu P, Levine BD, Zhang R, Lu H (2013) Life-long aerobic exercise preserved baseline cerebral blood flow but reduced vascular reactivity to CO2. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI 38, 1177–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Guan Y, Yan Z (2022) Molecular Mechanisms of Exercise and Healthspan. Cells 11, 872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, Himmelfarb CD, Khera A, Lloyd-Jones D, McEvoy JW, Michos ED, Miedema MD, Muñoz D, Smith SC, Virani SS, Williams KA, Yeboah J, Ziaeian B (2019) 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 140, e596–e646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]