Abstract

Background

Previous studies on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of health-care workers have relied on self-reported screening measures to estimate the point prevalence of common mental disorders. Screening measures, which are designed to be sensitive, have low positive predictive value and often overestimate prevalence. We aimed to estimate prevalence of common mental disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among health-care workers in England using diagnostic interviews.

Methods

We did a two-phase, cross-sectional study comprising diagnostic interviews within a larger multisite longitudinal cohort of health-care workers (National Health Service [NHS] CHECK; n=23 462) during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the first phase, health-care workers across 18 NHS England Trusts were recruited. Baseline assessments were done using online surveys between April 24, 2020, and Jan 15, 2021. In the second phase, we selected a proportion of participants who had responded to the surveys and conducted diagnostic interviews to establish the prevalence of mental disorders. The recruitment period for the diagnostic interviews was between March 1, 2021 and Aug 27, 2021. Participants were screened with the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) and assessed with the Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised (CIS-R) for common mental disorders or were screened with the 6-item Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-6) and assessed with the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) for PTSD.

Findings

The screening sample contained 23 462 participants: 2079 participants were excluded due to missing values on the GHQ-12 and 11 147 participants due to missing values on the PCL-6. 243 individuals participated in diagnostic interviews for common mental disorders (CIS-R; mean age 42 years [range 21–70]; 185 [76%] women and 58 [24%] men) and 94 individuals participated in diagnostic interviews for PTSD (CAPS-5; mean age 44 years [23–62]; 79 [84%] women and 15 [16%] men). 202 (83%) of 243 individuals in the common mental disorders sample and 83 (88%) of 94 individuals in the PTSD sample were White. GHQ-12 screening caseness for common mental disorders was 52·8% (95% CI 51·7–53·8). Using CIS-R diagnostic interviews, the estimated population prevalence of generalised anxiety disorder was 14·3% (10·4–19·2), population prevalence of depression was 13·7% (10·1–18·3), and combined population prevalence of generalised anxiety disorder and depression was 21·5% (16·9–26·8). PCL-6 screening caseness for PTSD was 25·4% (24·3–26·5). Using CAPS-5 diagnostic interviews, the estimated population prevalence of PTSD was 7·9% (4·0–15·1).

Interpretation

The prevalence estimates of common mental disorders and PTSD in health-care workers were considerably lower when assessed using diagnostic interviews compared with screening tools. 21·5% of health-care workers met the threshold for diagnosable mental disorders, and thus might benefit from clinical intervention.

Funding

UK Medical Research Council; UCL/Wellcome; Rosetrees Trust; NHS England and Improvement; Economic and Social Research Council; National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at the Maudsley and King's College London (KCL); NIHR Protection Research Unit in Emergency Preparedness and Response at KCL.

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, health-care systems across the world have been subject to considerable strain, which in turn has stimulated global efforts to understand how this has affected health-care workers. In addition to stressors common to all, including the risk of infection, social isolation, and difficulties obtaining child care, clinical and non-clinical health-care workers have faced distinct stressors such as overwork, increased patient mortality, staffing difficulties, inadequate personal protective equipment, potential moral injury (ie, distress experienced due to a conflict between one's personal morals and actions observed or undertaken), and the need to adapt working practices to manage infection risk. Numerous studies estimating the prevalence of mental disorders among health-care workers have been conducted since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 An umbrella review of evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic and previous viral outbreaks demonstrated highly heterogeneous estimates of prevalence of mental disorders.1 Pooled prevalence estimates of anxiety and depression were commonly used, but varied substantially (9–90% for anxiety; 5–65% for depression). Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was less commonly assessed, with prevalence estimates between 7 and 37%.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Numerous studies have examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health and wellbeing of health-care workers. We used a 2021 review of reviews consisting of 13 systematic reviews and one umbrella review of meta-analyses examining the prevalence of mental disorders in health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. This review included studies published up to June 2, 2021; we did an additional systematic search of PubMed Central and MEDLINE for articles published between June 2 and Nov 12, 2021, using the same search parameters and inclusion criteria as the review. The search terms used were “healthcare”, “burnout”, “mental health”, “COVID-19”, and “SARS-CoV-2”, in addition to the controlled vocabulary of the database, and studies were included if they were English language publications that contained a quantitative analysis investigating the prevalence of anxiety, depression, burnout syndrome, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sleep disorders, and other mental health outcomes in health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our additional search identified nine additional reviews. Included reviews had a wide global reach and sampled a range of health-care worker populations, often focusing on front-line staff. The reviews provided estimates of several mental disorders: most commonly anxiety and depression and less frequently PTSD. Prevalence estimates of all three disorders varied widely (9–90% for anxiety, 5–65% for depression, and 7–37% for PTSD). Reviews also examined a range of stress-related and sleep-related difficulties. The individual studies described in the reviews were typically cross-sectional and employed a range of screening tools to assess PTSD, depression, and anxiety, and were commonly administered through self-report online surveys.

Added value of this study

The diagnostic interviews used in this study provide a more accurate estimate of prevalence than previous studies using screening tools, since cutoff scores on screening tools favour sensitivity over specificity. Using a two-phase epidemiological design as a practical methodological approach to generate accurate estimates of the prevalence of common mental disorders and PTSD in a population of health-care workers broadly representative of the National Health Service workforce in England in terms of ethnicity, age, sex, and clinical role, we found the prevalence of depression was 13·7%, generalised anxiety disorder was 14·3%, and PTSD was 7·9%. The combined prevalence of depression and generalised anxiety disorder was 21·5%.

Implications of all the available evidence

Self-report screening surveys conducted among health-care workers during the pandemic have overestimated the prevalence of mental disorders. However, the findings from diagnostic interviews suggest a considerable number of health-care workers have a diagnosable mental disorder (eg, depression, generalised anxiety disorder, or PTSD) that might benefit from a clinical intervention.

This evidence is largely based on online surveys using screening tools for mental disorders. Generally, a screening tool is a brief measure that identifies so-called caseness, on the basis of mental health symptoms, characteristics, or traits. Typically, a cutoff score is used as an indicator of probable mental disorder or clinically significant symptoms.2 This method allows for relatively rapid and low-cost data collection with large samples. However, many of the validated screening tools widely used in mental health research favour sensitivity over specificity and therefore have low positive predictive value,3 and thus are likely to overestimate the true prevalence of mental disorders.4

Diagnostic interviews, in which trained interviewers use structured tools to assess patients by operationalising diagnostic criteria, are considered the gold standard for identification of mental disorders.5 These assessments are more resource intensive and in general more extensive than screening tools. A two-phase epidemiological survey design6 enables efficient and accurate estimation of prevalence by using surveys to screen for disorder in a sample of participants from a target population, followed by structured diagnostic interviews administered to a proportion of participants who completed the screening measure and were selected according to their response on the initial survey.

Considering the wide variation in estimates of prevalence of mental disorders among health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, obtaining an accurate understanding of the burden caused by mental illness in this population is important to plan for the scale and nature of clinical resources required, and to help direct preventative approaches. In this study, we aimed to estimate the prevalence of clinically diagnosable common mental disorders and PTSD among health-care workers in England during the COVID-19 pandemic using diagnostic interviews.

Methods

Study design and participants

We nested a two-phase cross-sectional survey within National Health Service (NHS) CHECK, a prospective cohort study examining the health and wellbeing of health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Full details of this study are outlined in a protocol paper.7 Briefly, in the first phase we recruited health-care workers across 18 NHS Trusts to a longitudinal study assessing the psychosocial impact of the pandemic. An NHS Trust is an organisational unit within the NHS of England and Wales, generally serving either a geographical area or offering specialist services. Baseline assessments were done using online surveys between April 24, 2020, and Jan 15, 2021. We included both acute and mental health NHS Trusts. In the second phase, we selected a proportion of participants who had responded to the surveys and conducted diagnostic interviews to establish the prevalence of mental disorders.

The recruitment period for the diagnostic interviews was between March 1, 2021, and Aug 27, 2021. We identified eligible participants through a database of NHS CHECK participants who had completed the baseline assessment for NHS CHECK and who had given permission to be contacted about further research. At the baseline assessment, participants filled in validated screening tools for mental disorders: the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) to screen for common mental disorders (including depression and anxiety) and the 6-item Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-6) to screen for PTSD. Consistent with previous studies, we oversampled cases for the diagnostic interviews, compared with non-cases, whereby 50% of invited interviewees met probable caseness on the GHQ-12 or PCL-6 administered at baseline.6, 8 The other 50% of invited interviewees did not meet probable caseness on either of these screening tools.

We used the same method to separately recruit two samples of health-care workers until the desired sample size for each of the diagnostic interviews was reached; one sample was assessed for prevalence of common mental disorders and one for prevalence of PTSD. Eligible participants were stratified by NHS Trust and probable caseness on the basis of the baseline scores derived from the GHQ-12 and PCL-6. To ensure that the sample reflected the characteristics of the main NHS CHECK sample, we recruited the same proportion of participants from each NHS Trust, inviting a random selection of health-care workers who had completed the GHQ-12 and PCL-6 baseline assessments from each NHS Trust. However, over the course of the recruitment period certain groups of interest were less responsive, in particular health-care workers from ethnic minority backgrounds. Therefore, to ensure that the diagnostic interview samples reflected the characteristics of the main NHS CHECK sample (ie, NHS Trust, clinical role, age, sex, and ethnicity) and to ensure generalisability of the study to the wider health-care worker population, we targeted underrepresented groups for inclusion in the interview samples, randomly selecting from a list of health-care workers with these required characteristics. Potentially eligible participants were emailed an invitation to participate and an information sheet; individuals who responded confirming interest could book an interview slot via an online calendar, and subsequently completed a consent form. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Health Research Authority (20/HRA/210, IRAS: 282686) and the Research and Development department of each local Trust.

Procedures

NHS CHECK baseline assessment data from the PCL-69 were used to identify participants with or without probable PTSD, whereby a score of 14 or higher was considered to indicate caseness. The GHQ-12,10 scored 0–0-1–1, was used to identify individuals with or without probable common mental disorders, whereby a score of 4 or higher was considered to indicate caseness.11, 12 The GHQ has strong psychometric properties compared with other such tools, and since anxiety and depression are generally the most prevalent mental disorders, using the scores on the GHQ as an indicator for probable common mental disorders is valid.10, 11, 13

The past-month version of the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for the DSM-5 (CAPS-5)14 was used to assess participants for PTSD during the diagnostic interview. The CAPS-5 is a structured interview tool comprising 30 items across seven criteria referring to symptoms in the previous month. Diagnostic status for each participant was determined according to the CAPS-5 manual and consistent with DSM-5 rules, accounting for the presence of symptoms across each criterion, duration of symptoms, the extent to which symptoms are trauma related, and overall impairment and distress. The CAPS-5 has been shown to have good psychometric properties.15

The Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised (CIS-R)16 was used to assess participants for common mental disorders during the diagnostic interview. The CIS-R is a structured assessment tool that assesses 14 symptom groups related to common mental disorders in modules that branch according to responses. All modules of the tool were administered, although only the depression and anxiety modules were used in the analysis for this study. Diagnostic status for each participant was determined according to the CIS-R manual,17 using an algorithm to calculate status in accordance with ICD-10 rules for diagnosis of mild-to-severe depression and generalised anxiety disorder. The CIS-R has been shown to have good psychometric properties5 and has been used previously with a population of UK health-care workers to validate the GHQ-12.11

Diagnostic interviews conducted during phase two of the survey were done over the telephone or Microsoft Teams videoconferencing software with one of three study researchers (HRS, SH, or ES), each of whom had completed training in administering the CIS-R and CAPS-5 tools. Interviews typically lasted between 20 min and 1 h. Interviewers recorded interviewees' responses using Qualtrics survey software and interviews were audio recorded in case of a need for verification. Participants who completed the interview received a £25 gift voucher in recognition of time volunteered for the study.

The primary outcome was population prevalence of common mental disorders and PTSD.

Statistical analysis

We aimed to recruit 94 participants to take part in the CAPS-5 and 250 participants for the CIS-R interviews. For CIS-R, the required sample size was derived via a simulation study. The simulation study repeated all stages of the two-stage design including: (1) simulating caseness of the screening measure based on descriptive statistics for existing NHS CHECK respondents; (2) drawing subsamples of varying sizes; (3) simulating caseness from diagnostic interviews based on expert opinion and previous studies;11, 18 and (4) conducting the two-stage procedure where we weighted the interview sample (using raking weights) to estimate population prevalence and 95% CIs. These steps were repeated (1000 times) to provide estimates of the uncertainty of the prevalence estimate under differing scenarios.

We used descriptive statistics to describe outcome scores overall and by age group, sex, ethnic group, and clinical role. We compared the profile of the NHS CHECK screening sample with the diagnostic interview samples and with the target population of NHS staff at all participating Trusts in NHS CHECK.

We used a two-phase design to estimate the population prevalence of common mental disorders and PTSD.6, 8 First, we calculated the prevalence of probable common mental disorders and PTSD using the screening tools (GHQ-12 and PCL-6). The prevalence of a combined measure of any mental disorder was calculated based on screening positive on at least one of the screening measures (GHQ-12 or PCL-6). Second, we calculated the prevalence using diagnostic interviews (CIS-R for generalised anxiety disorder or depression and the CAPS-5 for PTSD). We also calculated a combined caseness measure (generalised anxiety disorder and depression) by combining the prevalence of both outcomes on the CIS-R. Third, to estimate population prevalence, we post-stratified caseness from the diagnostic interviews using information from the screening measures (GHQ-12 or PCL-6 prevalence) and applied a finite population correction based on total population size (n=21 383).19

The prevalence of each outcome after diagnostic interviews (CIS-R for generalised anxiety disorder or depression and the CAPS-5 for PTSD) are presented as proportions and 95% CIs. To account for differences between the screening cohort and the target population, all estimates were weighted. Missing values were excluded from the estimation of the point prevalences and associated CIs.

Survey weights were derived to account for differences between the baseline NHS CHECK cohort and the target population (NHS staff at all participating Trusts in NHS CHECK) by age (≤30, 31–40, 41–50, 51–60, and ≥61 years), sex (female or male), ethnic group (White, Black, Asian, Mixed, and Other), and clinical role (clinical or non-clinical). Information on these characteristics in the population were provided by human resources departments for each participating NHS Trust. Weights were derived by (1) harmonising information on the variables (age, sex, ethnicity, and clinical role) from the administrative records with corresponding variables from the survey; (2) imputing missing information in these variables among survey respondents using k-nearest neighbours (k=5) with the VIM package for R; (3) generating weights using iterative proportional fitting (ie, raking) with the survey package for R (version 4.1.0); (4) trimming extreme weights, such that individual weights greater than WT were fixed at WT, where WT equals the median weight plus five times the IQR. Two procedures were used: (1) post-stratification to estimate prevalence in the larger screening sample based on prevalence in the diagnostic interviews sample; (2) application of survey weights to the screening sample to correct for differences between this sample and the target population. These two procedures (post-stratification and survey weighting) were combined to give a final, weighted estimate of prevalence in the population.

The screened point prevalence of each of the outcomes was tabulated after the weighted continuous outcome scores were dichotomised by predetermined cutoffs (≥4 for GHQ-12 and ≥14 for PCL-6) and survey set using Stata statistical software (version 16.0). Survey setting enabled valid inference to be made from the screening sample to the population risk, taking into account clustering at the NHS Trust level; this was done by using the individual level weights and then post-stratifying using the NHS Trust sizes.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

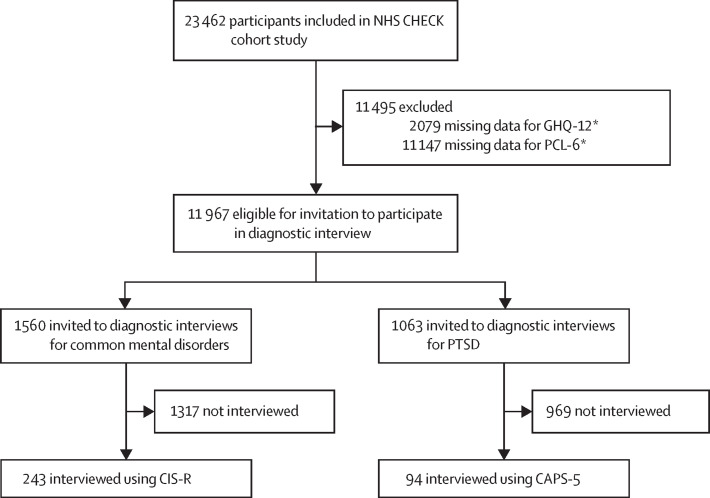

The screening sample contained 23 462 participants (of a possible population of 152 228 [overall response rate to NHS CHECK 15·4%]): 2079 participants were excluded due to missing values on the GHQ-12 and 11 147 participants due to missing values on the PCL-6. 243 individuals participated in diagnostic interviews for common mental disorders (CIS-R) and 94 individuals participated in diagnostic interviews for PTSD (CAPS-5; overall response rate to diagnostic interviews 12·9%; figure ). Individuals who were missing GHQ-12 or PCL-6 values were more likely to be non-White than White (11·50% vs 6·76% for GHQ-12; 62·34% vs 44·06% for PCL-6; data not shown). No marked differences were identified among individuals with missing values versus those without missing values in terms of age, role, or sex.

Figure.

Overview of participants invited to the diagnostic interviews

NHS=National Health Service. GHQ-12=12-item General Health Questionnaire. PCL-6=6-item Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder checklist. PTSD=post-traumatic stress disorder. CAPS-5=Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for the DSM-5. CIS-R=Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised. *Not mutually exclusive; some individuals were missing data for both the GHQ-12 and PCL-6.

The demographic compositions of the screening sample, of the two diagnostic interview samples (common mental disorders and PTSD), and of all NHS staff at the participating NHS Trusts are shown in table 1 . The two diagnostic interview samples were relatively similar to the screening sample: the majority of the samples were White, female, and clinical staff, with larger proportions of younger participants than older participants, and a larger proportion of staff earning an annual salary of more than £30 000. The composition of the common mental disorders sample was similar to the screening sample with regard to clinical setting (eg, Accident and Emergency, intensive care unit [ICU], or other), but the PTSD sample contained a larger proportion of individuals who worked in ICUs than the screening sample. People from a White ethnic background were over-represented in the interview samples compared with the composition of all NHS staff across the 18 participating NHS Trusts. Of the PSTD diagnostic interview sample, 36 (38·30%) of 94 met criteria for caseness on the PCL-6 at baseline, and 132 (54·32%) of 243 individuals in the common mental disorders diagnostic interview sample met criteria for caseness on the GHQ-12 at baseline.

Table 1.

Demographic baseline characteristics of the study samples

|

NHS CHECK screening sample*(n= 23 462) |

Depression and anxiety diagnostic interview sample (n=243) | PTSD diagnostic interview sample (n=94) | NHS CHECK baseline human resources data (n=152 228) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Proportion of participants with no missing data, % | ||||

| Age, years | |||||

| ≤30 | 4464 (19·03%) | 20·23% | 53 (21·81%) | 16 (17·02%) | 32 777 (21·53%) |

| 31–40 | 5084 (21·67%) | 23·05% | 53 (21·81%) | 17 (18·09%) | 39 272 (25·80%) |

| 41–50 | 5771 (24·60%) | 26·16% | 64 (26·34%) | 27 (28·72%) | 36 417 (23·92%) |

| 51–60 | 5400 (23·02%) | 24·48% | 66 (27·16%) | 30 (31·91%) | 33 591 (22·07%) |

| ≥61 | 1342 (5·72%) | 6·08% | 6 (2·47%) | 3 (3·19%) | 10 010 (6·58%) |

| Missing | 1401 (5·97%) | .. | 1 (0·41%) | 1 (1·06%) | 161 (0·11%) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 4300 (18·33%) | 18·72% | 58 (23·87%) | 15 (15·96%) | 40 599 (26·67%) |

| Female | 18 673 (79·59%) | 81·28% | 185 (76·13%) | 79 (84·04%) | 111 629 (73·33%) |

| Missing | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White† | 19 732 (84·10%) | 85·62% | 202 (83·13%) | 83 (88·30%) | 107 373 (70·53%) |

| Black‡ | 1004 (4·28%) | 4·36% | 12 (4·94%) | 3 (3·19%) | 12 348 (8·11%) |

| Asian§ | 1527 (6·51%) | 6·63% | 16 (6·58%) | 5 (5·32%) | 18 190 (11·95%) |

| Mixed | 566 (2·41%) | 2·46% | 10 (4·12%) | 2 (2·13%) | 3254 (2·14%) |

| Other | 217 (0·92%) | 0·94% | 3 (1·23%) | 1 (1·06%) | 3906 (2·57%) |

| Missing | 416 (1·77%) | .. | .. | .. | 7157 (4·70%) |

| Main role | |||||

| Clinical | 14 730 (62·78%) | 63·74% | 166 (68·31%) | 64 (68·09%) | 110 424 (72·54%) |

| Non-clinical | 8378 (35·70%) | 36·26% | 77 (31·69%) | 30 (31·91%) | 40 721 (26·75%) |

| Missing | 354 (1·51%) | .. | .. | .. | 1083 (0·71%) |

| Setting | |||||

| Accident and emergency | 335 (1·44%) | 1·58% | 6 (2·47%) | 3 (3·19%) | NA |

| ICU or critical care | 839 (3·39%) | 3·74% | 9 (3·70%) | 29 (30·85%) | NA |

| Other hospital | 13 446 (54·39%) | 59·91% | 132 (54·32%) | 37 (39·36%) | NA |

| Community | 6717 (27·17%) | 29·93% | 86 (35·39%) | 21 (22·34%) | NA |

| Non-patient-facing | 1088 (4·40%) | 4·85% | 9 (3·70%) | 4 (4·26%) | NA |

| Missing | 2276 (9·21%) | .. | 1 (0·41%) | .. | NA |

| Pay grade¶ | |||||

| ≤£30 000 (AfC pay scale ≤5) | 7336 (29·68%) | 37·06% | 67 (27·57%) | 21 (22·34%) | NA |

| >£30 000 (AfC pay scale ≥6 including medical pay scales) | 12 461 (50·41%) | 62·94% | 153 (62·96%) | 62 (65·96%) | NA |

| Missing | 4924 (19·92%) | .. | 23 (9·47%) | 11 (11·70%) | NA |

| GHQ-12 | |||||

| Screen positive | 11 290 (48·12%) | 52·80% | 132 (54·32%) | NA | NA |

| Screen negative | 10 093 (43·02%) | 47·20% | 111 (45·68%) | NA | NA |

| Missing | 2079 (8·86%) | .. | .. | NA | NA |

| PCL-6 | |||||

| Screen positive | 2908 (12·39%) | 23·61% | NA | 36 (38·30%) | NA |

| Screen negative | 9407 (40·09%) | 76·39% | NA | 58 (61·70%) | NA |

| Missing | 11 147 (47·51%) | .. | NA | .. | NA |

Data are n (%). NHS=National Health Service. PTSD=post-traumatic stress disorder. ICU=intensive care unit. NA=not applicable. AfC=Agenda for change. GHQ-12=12-item General Health Questionnaire. PCL-6=6-item Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder checklist.

Full NHS CHECK baseline cohort.

White English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish, or British.

Black, African, Caribbean, or Black British.

Asian or British Asian.

The prevalence of GHQ caseness in the screening sample was 52·8% (95% CI 51·7–53·8; table 2 ). Using the CIS-R questionnaire as a gold standard, the population validated prevalence of generalised anxiety disorder was estimated to be 14·3% (10·4–19·2) and of depression was estimated to be 13·7% (10·1–18·3). The combined population validated prevalence of generalised anxiety disorder and depression derived from the CIS-R questionnaire was 21·5% (16·9–26·8). The prevalence of PTSD (using the PCL-6 outcome measure) in our screening sample was 25·4% (24·3–26·5), whereas the population validated prevalence using the CAPS-5 questionnaire as a gold standard was estimated to be 7·9% (4·0–15·1). The screening prevalence of any mental disorder was 53·9% (52·9–54·9).

Table 2.

Weighted point prevalences of screening and diagnostic measures

| Scale | Cohort | Prevalence, % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common mental disorders | GHQ-12 | Screening | 52·8% (51·7–53·8) |

| PTSD | PCL-6 | Screening | 25·4% (24·3–26·5) |

| Any mental disorder (PTSD or common mental disorders) | PCL-6 or GHQ-12 | Screening | 53·9% (52·9–54·9) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | CIS-R | Diagnostic interview | 14·3% (10·4–19·2) |

| Depression | CIS-R | Diagnostic interview | 13·7% (10·1–18·3) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder or depression | CIS-R | Diagnostic interview | 21·5% (16·9–26·8) |

| PTSD | CAPS-5 | Diagnostic interview | 7·9% (4·0–15·1) |

Sample was weighted to ensure it was representative with respect to age, sex, ethnicity, and clinical role. Participants with missing values in outcome scores were excluded for each calculation of the outcome. GHQ-12=12-item General Health Questionnaire. PTSD=post-traumatic stress disorder. PCL-6=6-item Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder checklist. CAPS-5=Clinician-Administered PTSD scale for DSM-5. CIS-R=Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised.

Discussion

As part of a large health and wellbeing survey of health-care workers in England during the pandemic, we used a two-stage epidemiological survey design in which health-care workers completed both self-report screening measures using standard cutoffs and diagnostic interviews for mental disorders (eg, depression, generalised anxiety disorder, and PTSD). The prevalence of these mental disorders within our sample was higher when using a screening tool (GHQ-12 or PCL-6) than when using a diagnostic interview tool (CIS-R or CAPS-5). For common mental disorders, the screening prevalence was 52·8% whereas when using the diagnostic interview, the population validated prevalence was 14·3% for generalised anxiety disorder and 13·7% for depression. The combined prevalence of depression and generalised anxiety disorder was 21·5%. For PTSD, the screening prevalence was 25·4%, whereas the population validated prevalence of PTSD using the diagnostic interview was 7·9%. These findings suggest that the screening tools with commonly used cutoff scores, utilised by many studies, substantially overestimate the prevalence of mental disorders.

Our estimated population prevalences of common mental disorders and PTSD at the population level were substantially lower than estimates from other UK studies of health-care workers (eg, front-line health-care workers, social care staff, and ICU staff) using self-report screening tools23, 24 and studies that included samples with sizeable groups of non-front-line health-care workers.25, 26 Lower prevalence estimates when using diagnostic interviews are consistent with previous pre-pandemic studies that have found screening tools overestimate prevalence.27, 28 Studies of mental disorder in health-care workers using screening tools are likely to have over-labelled distress as diagnosable disorder, which is an important distinction regarding treatment decisions and service planning. Non-professional, team-based interventions and support are preferable for managing distress symptoms, with professional care from mental health professionals being more suitable for individuals with a diagnosable disorder.29, 30 Overestimating the prevalence of mental disorders is unhelpful, with the risk of over-treatment and inappropriate medicalisation of distress.31, 32

To the best of our knowledge, this is the only study done during the COVID-19 pandemic to use a two-phase epidemiological design to estimate the prevalence of depression, generalised anxiety disorder, and PTSD in health-care workers in England. One published study by Wild and colleagues33 of UK health-care workers used diagnostic interviewing to estimate prevalence of PTSD (44%) and depression (39%) in a sample of 103 front-line health-care workers in England, only interviewing individuals who scored above clinical cutoffs on the PTSD Checklist for DSM-534 and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 screening tools using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5.35 The study did not calculate the true population prevalence and prevalence estimates were markedly higher than those found in our study, which might be explained by the use of different diagnostic tools, differences in sample characteristics, and the use of convenience sampling. The sample used by Wild and colleagues consisted primarily of front-line ambulance staff and nurses, recruited from four NHS Hospitals and Ambulance Trusts, limiting generalisability to the wider population of health-care workers. The authors found that most participants diagnosed with PTSD reported an index event that happened before the COVID-19 pandemic, whereas major depressive disorder symptoms seemed to have developed over the course of the pandemic.33 We were unable to explore time of onset for the mental health outcomes of interest or the index event for PTSD in this study.

A major strength of our study was that our sample was weighted using administrative data to improve the representativeness of survey respondents to the target population in terms of ethnicity, age, sex, and clinical role. Although the response rate to the NHS CHECK cohort was only 15·4%, we believe it is the highest reported response rate when compared with similar studies that had a known, identifiable, and inclusive target population. The characteristics of our NHS CHECK sample are broadly comparable with NHS workforce statistics at the national level regarding ethnicity, age, sex, and clinical role.36 We also included both clinical and non-clinical staff in recognition of the burden that all health-care workers have faced during the pandemic. Acute and mental health NHS Trusts were included in NHS CHECK cohort, therefore exposures to some of the challenges associated with the pandemic would have been experienced differently, for example, by clinical staff working in an ICU, or emergency department, when compared with staff working on an acute psychiatric inpatient unit. Our research could be used in conjunction with findings from other studies that identify which particular groups of health-care workers might be at an increased risk of mental disorders, similar to previous work published by the NHS CHECK team,18 which showed that nurses, younger health-care workers, women, and individuals exposed to morally injurious events were at increased risk. The prevalence estimates reported in these studies are likely to be overestimations due to the use of screening tools; however, the identification of risk groups would remain valid.

Our study was limited by several factors. The study was based on participants from 18 NHS Trusts who had completed the screening tools (GHQ-12 and PCL-6) at baseline. Although the sampling procedures were designed to provide a representative sample of health-care workers within each participating site, we did not include a random sample of English hospitals. We also had a relatively low response rate to the diagnostic interview study (12·9%), and participants were self-selected responders to an already self-selected sample from our cohort study.7 Previous research has shown that people with mental disorders are less likely to take part in research, and this might have led to an underestimation of our prevalence estimates.37 Furthermore, individuals from minority ethnic backgrounds were less likely to have completed the PCL-6 or GHQ-12 during the NHS CHECK baseline assessment, possibly resulting in a selection bias, despite targeted recruitment efforts to increase the number of participants from a minority ethnic background for the diagnostic interviews. It is important to note that the confidence interval for the population prevalence estimate of PTSD was wide due to a small sample size, resulting in a less precise prevalence estimate. A larger number of participants had missing values on the PCL-6 than the GHQ-12 since the PCL-6 was only included in the second, optional part of the baseline questionnaire instead of the first, compulsory part of the baseline questionnaire. We offered a short and long version of this baseline questionnaire taking into consideration pressures of working in a health-care setting during the pandemic and participant burden.

A further limitation that applies to all studies that focus on health-care workers alone is the possibility of a contextual bias or framing effect, which applies to studies that focus on any specific workforce, such as health-care workers, teachers, police, military personnel, and others.38 In such studies, prevalence estimates of mental disorders are higher than occupation-specific prevalences extracted from larger true population studies in which occupation is collected as an incidental variable. This has been supported by more research on the impact of COVID-19, where population studies reported lower prevalence estimates in health-care workers than did surveys of health-care workers specifically. Use of diagnostic interviews might reduce this systematic bias by providing a more rigorous assessment of mental disorder, but this is unlikely to eliminate bias completely. Furthermore, no data were available from assessment points before the COVID-19 pandemic, thus we are unable to draw conclusions as to whether the prevalence of common mental disorders and PTSD in this population has changed since the start of the pandemic; the study was also not sufficiently powered to examine differences between subgroups (such as clinical and non-clinical staff, type of NHS Trust, or clinical speciality) due to careful consideration about what was feasible within the time and resources available. A larger study could support or refute the risk factors highlighted in previous research.39 We did not directly assess individuals' need for treatment and cannot be certain what proportion of individuals might benefit from formal treatment. Another limitation was the time lag between the baseline assessment of NHS CHECK for common mental disorders and PTSD and the diagnostic interview study (mean 265 days [SD 8]). Symptoms for some participants might have naturally eased over time, whereas other participants could have developed symptoms of a mental disorder. The longitudinal data of NHS CHECK indicate that despite slight variations in the screening prevalence of common mental disorders and PTSD, depending on the timing of the follow-up assessments, these prevalences remained relatively stable.40 Taken together, we believe that our results indicate a true overestimation of common mental disorders and PTSD prevalence when using screening measures compared with diagnostic interviews.

In summary, we found that previous self-report prevalence estimates of common mental disorders and PTSD in health-care workers in England during the pandemic are likely to have been overestimated. However, our data show that 21·5% of health-care workers meet criteria for a diagnosable mental disorder. Although evidence suggests that health-care workers operating in challenging environments will often work through potentially traumatic events without the need for clinical intervention,41 considering the known association between diagnosable mental disorders and poor workplace functioning, we suggest that it might be helpful to provide treatment promptly for health-care workers with diagnosable mental disorders.42 This approach is likely to both benefit health-care workers themselves and ensure quality of care for patients by maintaining a well functioning workforce. More broadly, researchers seeking to assess psychiatric symptoms using self-report screening tools in novel contexts should carefully consider cutoff scores on screening tools, and ideally complete further validation work to correctly calibrate measures to be appropriately sensitive. It can be unhelpful to report results from self-report tools since they might cause alarm and inappropriate allocation of scarce resources. Additionally, the variation in important prognostic indicators (past mental illness, urbanicity of clinical service provision, length of clinical contact) needs to be investigated if timely resources and treatments are to be provided to a population with high prevalence of mental distress. Further longitudinal research should be carried out to ascertain whether estimates of common mental disorders and PTSD among health-care workers exist before they start their role, are sustained during employment, or decrease over time.

Data sharing

Data will be available to researchers who provide a justified hypothesis and structured statistical analysis plan addressing a legitimate research question that is approved by the NHS CHECK Senior Research Team and after the signing of a data sharing agreement. Only deidentified participant data will be provided.

Declaration of interests

SAMS is supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and an NIHR Advanced Fellowship. MH has received funding from the Innovative Medicines Initiative for the RADAR-CNS programme, a public-private pre-competitive consortium in mHealth, and his university received research funding from Janssen, Biogen, UCB, MSD, and Lundbeck. PM is supported by the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration (ARC; West) and the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol, Weston NHS Foundation Trust, and the University of Bristol. NG has been an unpaid member of two NHS England expert advisory groups; and owns the company March on Stress, which is a psychological health consultancy providing mental health training to a wide range of organisations including the NHS. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Medical Research Council (MR/V034405/1), UCL/Wellcome (ISSF3/H17RCO/C3), the Rosetrees Trust (M952), NHS England and Improvement, and the Economic and Social Research Council (ES/V009931/1). This report is independent research supported by the NIHR ARC North Thames. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Institute for Health and Care Research or the Department of Health and Social Care. We wish to acknowledge the National Institute of Health Research Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) National NHS and Social Care Workforce Group, with the following ARCs: East Midlands, East of England, South West Peninsula, South London, West, North West Coast, Yorkshire and Humber, and North East and North Cumbria. They enabled the set-up of the national network of participating hospital sites and aided the research team to recruit effectively during the COVID-19 pandemic. The NHS CHECK consortium includes the following site leads: Sean Cross, Amy Dewar, Chris Dickens, Frances Farnworth, Adam Gordon, Charles Goss, Jessica Harvey, Nusrat Husain, Peter Jones, Damien Longson, Richard Morriss, Jesus Perez, Mark Pietroni, Ian Smith, Tayyeb Tahir, Peter Trigwell, Jeremy Turner, Julian Walker, Scott Weich, and Ashley Wilkie. The NHS CHECK consortium includes the following co-investigators and collaborators: Peter Aitken, Anthony David, Rosie Duncan, Cerisse Gunasinghe, Stephani Hatch, Daniel Leightley, Isabel McMullen, Martin Parsons, Dominic Murphy, Catherine Polling, Alexandra Pollitt, Danai Serfioti, Chloe Simela, and Charlotte Wilson Jones.

Contributors

DL, EC, IM, SG, MJD, IB, MH, RRai, RRaz, NG, SAMS, and SW conceptualised the study and secured funding. HS, SH, and ES recruited and interviewed participants. DW managed the database, HRS and RB completed project administration, HRS, DL, EC, IB, and DW curated the data, and DL, EC, IB, and RG analysed the data. DL, HRS, RG, and SAMS interpreted the findings. HRS and RG created the first draft of the manuscript. HRS, DL, SD, EC, RG, SH, ES, IM, RB, DW, SG, PM, MD, IB, SM, MH, RRaz, RRai, NG, SAMS, and SW critically revised and approved the manuscript. DW, DL, HRS, and RG had full access to all the data in the study. HRS, RG, SAMS, NG, and SW had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

References

- 1.Chirico F, Ferrari G, Nucera G, Szarpak L, Crescenzo P, Ilesanmi O. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, burnout syndrome, and mental health disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid umbrella review of systematic reviews. J Health Soc Sci. 2021;6:209–220. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levis B, Yan XW, He C, Sun Y, Benedetti A, Thombs BD. Comparison of depression prevalence estimates in meta-analyses based on screening tools and rating scales versus diagnostic interviews: a meta-research review. BMC Med. 2019;17:65. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1297-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thombs BD, Kwakkenbos L, Levis AW, Benedetti A. Addressing overestimation of the prevalence of depression based on self-report screening questionnaires. CMAJ. 2018;190:E44–E49. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levis B, Benedetti A, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores do not accurately estimate depression prevalence: individual participant data meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;122:115–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordanova V, Wickramesinghe C, Gerada C, Prince M. Validation of two survey diagnostic interviews among primary care attendees: a comparison of CIS-R and CIDI with SCAN ICD-10 diagnostic categories. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1013–1024. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunn G, Pickles A, Tansella M, Vázquez-Barquero JL. Two-phase epidemiological surveys in psychiatric research. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:95–100. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamb D, Greenberg N, Hotopf M, et al. NHS CHECK: protocol for a cohort study investigating the psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.06.08.21258551. published online June 15. (preprint). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deming WE. An essay on screening, or on two-phase sampling, applied to surveys of a community. Int Stat Rev. 1977;45:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang AJ, Stein MB. An abbreviated PTSD checklist for use as a screening instrument in primary care. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldberg DP. A user's guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Nelson Publishing Company Limited; Windsor: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hardy GE, Shapiro DA, Haynes CE, Rick JE. Validation of the General Health Questionnaire-12: using a sample of employees from England's health care services. Psychol Assess. 1999;11:159–165. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holi MM, Marttunen M, Aalberg V. Comparison of the GHQ-36, the GHQ-12 and the SCL-90 as psychiatric screening instruments in the Finnish population. Nord J Psychiatry. 2003;57:233–238. doi: 10.1080/08039480310001418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel V, Araya R, Chowdhary N, et al. Detecting common mental disorders in primary care in India: a comparison of five screening questionnaires. Psychol Med. 2008;38:221–228. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weathers FW, Bovin MJ, Lee DJ, et al. The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychol Assess. 2018;30:383–395. doi: 10.1037/pas0000486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weathers FW, Ruscio AM, Keane TM. Psychometric properties of nine scoring rules for the clinician-administered posttraumatic stress disorder scale. Psychol Assess. 1999;11:124–133. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis G, Pelosi AJ, Araya R, Dunn G. Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: a standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol Med. 1992;22:465–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700030415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NHS Digital Adult psychiatric morbidity survey 2014. http://doc.ukdataservice.ac.uk/doc/8203/read8203.htm

- 18.Lamb D, Gnanapragasam S, Greenberg N, et al. Psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on 4378 UK healthcare workers and ancillary staff: initial baseline data from a cohort study collected during the first wave of the pandemic. Occup Environ Med. 2021;78:801–808. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2020-107276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pickles A, Dunn G, Vázquez-Barquero JL. Screening for stratification in two-phase (‘two-stage’) epidemiological surveys. Stat Methods Med Res. 1995;4:73–89. doi: 10.1177/096228029500400106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Office for National Statistics Employee earnings in the UK: 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/annualsurveyofhoursandearnings/2020

- 21.NHS England Agenda for change–pay rates. 2020. https://www.healthcareers.nhs.uk/working-health/working-nhs/nhs-pay-and-benefits/agenda-change-pay-rates

- 22.British Medical Association Pay scales for junior doctors in England. https://www.bma.org.uk/pay-and-contracts/pay/junior-doctors-pay-scales/pay-scales-for-junior-doctors-in-england

- 23.Dykes N, Johnson O, Bamford P. Assessing the psychological impact of COVID-19 on intensive care workers: a single-centre cross-sectional UK-based study. J Intensive Care Soc. 2022;23:132–138. doi: 10.1177/1751143720983182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greene T, Harju-Seppänen J, Adeniji M, et al. Predictors and rates of PTSD, depression and anxiety in UK frontline health and social care workers during COVID-19. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2021;12:1882781. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.1882781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilleen J, Santaolalla A, Valdearenas L, Salice C, Fusté M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health and well-being of UK healthcare workers. BJPsych Open. 2021;7:e88. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wanigasooriya K, Palimar P, Naumann DN, et al. Mental health symptoms in a cohort of hospital healthcare workers following the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. BJPsych Open. 2021;7:e24. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rucci P, Gherardi S, Tansella M, et al. Subthreshold psychiatric disorders in primary care: prevalence and associated characteristics. J Affect Disord. 2003;76:171–181. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terhakopian A, Sinaii N, Engel CC, Schnurr PP, Hoge CW. Estimating population prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder: an example using the PTSD checklist. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21:290–300. doi: 10.1002/jts.20341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.WHO . Guidelines on mental health at work. World Health Organisation; Geneva: 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brooks SK, Dunn R, Amlôt R, Rubin GJ, Greenberg N. Protecting the psychological wellbeing of staff exposed to disaster or emergency at work: a qualitative study. BMC Psychol. 2019;7:78. doi: 10.1186/s40359-019-0360-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brooks SK, Rubin JG, Greenberg N. Traumatic stress within disaster exposed occupations: overview of the literature and suggestions for the management of traumatic stress in the workplace. Br Med Bull. 2019;129:25–34. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldy040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tracy DK, Tarn M, Eldridge R, Cooke J, Calder JDF, Greenberg N. What should be done to support the mental health of healthcare staff treating COVID-19 patients? Br J Psychiatry. 2020;217:537–539. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wild J, McKinnon A, Wilkins A, Browne H. Post-traumatic stress disorder and major depression among frontline healthcare staff working during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Clin Psychol. 2021;61:859–866. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.US Department of Veterans Affairs PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp

- 35.American Psychiatric Association Structured clinical interview for DSM-5. https://www.appi.org/products/structured-clinical-interview-for-dsm-5-scid-5#:~:text=The%20Structured%20Clinical%20Interview%20for%20DSM%2D5%20(SCID%2D5,5%20classification%20and%20diagnostic%20criteria

- 36.NHS Digital NHS workforce statistics-March 2019 (including supplementary analysis on pay by ethnicity) https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-workforce-statistics/nhs-workforce-statistics---march-2019-provisional-statistics

- 37.Knudsen AK, Hotopf M, Skogen JC, Overland S, Mykletun A. The health status of nonparticipants in a population-based health study: the Hordaland Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:1306–1314. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goodwin L, Ben-Zion I, Fear NT, Hotopf M, Stansfeld SA, Wessely S. Are reports of psychological stress higher in occupational studies? A systematic review across occupational and population based studies. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sirois FM, Owens J. Factors associated with psychological distress in health-care workers during an infectious disease outbreak: a rapid systematic review of the evidence. Front Psychiatry. 2021;11:589545. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.589545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lamb D, Gafoor R, Scott H, et al. Mental health of healthcare workers in England during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal cohort study. medRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.06.16.22276479. published online June 16. (preprint). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greenberg N, Wessely S, Wykes T. Potential mental health consequences for workers in the Ebola regions of west Africa—a lesson for all challenging environments. J Ment Health. 2015;24:1–3. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2014.1000676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hodkinson A, Zhou A, Johnson J, et al. Associations of physician burnout with career engagement and quality of patient care: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2022;378:e070442. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-070442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available to researchers who provide a justified hypothesis and structured statistical analysis plan addressing a legitimate research question that is approved by the NHS CHECK Senior Research Team and after the signing of a data sharing agreement. Only deidentified participant data will be provided.