Significance Statement

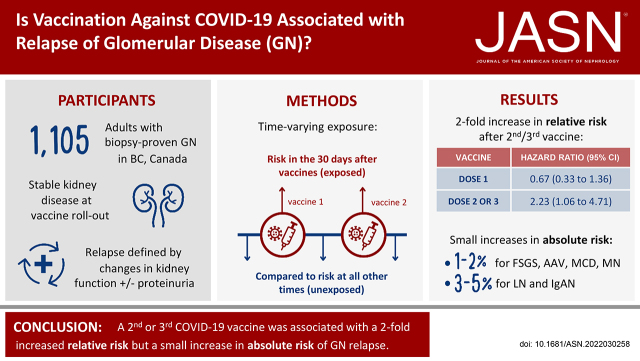

Several reports have described glomerular disease relapse after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination, but without proper controls, determining whether this association is real or due to chance is not possible. In this population-level cohort of 1105 adult patients with stable glomerular disease, a first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine was not associated with relapse risk; however, receiving a subsequent vaccine dose was associated with a two-fold higher risk of relapse. The increase in absolute risk associated with vaccination was low (1%–5%), and the majority of affected patients did not require a change in immunosuppression or biopsy. These results represent the first accurate assessment of the relative and absolute risks of glomerular disease flare associated with COVID-19 vaccination and underscore the favorable risk-benefit profile of vaccination in patients with glomerular disease.

Keywords: clinical epidemiology, glomerular disease, COVID-19, vaccination, recurrence, glomerulonephritis

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Although case reports have described relapses of glomerular disease after COVID-19 vaccination, evidence of a true association is lacking. In this population-level analysis, we sought to determine relative and absolute risks of glomerular disease relapse after COVID-19 vaccination.

Methods

In this retrospective population-level cohort study, we used a centralized clinical and pathology registry (2000–2020) to identify 1105 adult patients in British Columbia, Canada, with biopsy-proven glomerular disease that was stable on December 14, 2020 (when COVID-19 vaccines first became available). The primary outcome was disease relapse, on the basis of changes in kidney function, proteinuria, or both. Vaccination was modeled as a 30-day time-varying exposure in extended Cox regression models, stratified on disease type.

Results

During 281 days of follow-up, 134 (12.1%) patients experienced a relapse. Although a first vaccine dose was not associated with relapse risk (hazard ratio [HR]=0.67; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.33 to 1.36), exposure to a second or third dose was associated with a two-fold risk of relapse (HR=2.23; 95% CI, 1.06 to 4.71). The pattern of relative risk was similar across glomerular diseases. The absolute increase in 30-day relapse risk associated with a second or third vaccine dose varied from 1%–2% in ANCA-related glomerulonephritis, minimal change disease, membranous nephropathy, or FSGS to 3%–5% in IgA nephropathy or lupus nephritis. Among 24 patients experiencing a vaccine-associated relapse, 4 (17%) had a change in immunosuppression, and none required a biopsy.

Conclusions

In a population-level cohort of patients with glomerular disease, a second or third dose of COVID-19 vaccine was associated with higher relative risk but low absolute increased risk of relapse.

Since the widespread rollout of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccination in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, there have been numerous case reports of relapsing glomerular disease in the days to weeks after administration of a COVID-19 vaccine. The majority of published reports have described patients with IgA nephropathy or minimal change disease,1 but there have also been sporadic reports in patients with membranous nephropathy,2 antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis3 and antiglomerular basement membrane disease.4 Although most affected patients appear to have had a favorable clinical course over short-term follow-up, some have required intensification of immune therapies, and others have experienced a decline in their kidney function.5 This has led to concerns regarding the safety of COVID-19 vaccines among patients with glomerular disease.

The benefits of COVID-19 vaccination are indisputable, given consistent evidence of their efficacy from large-scale clinical trials and real-world data demonstrating their effectiveness in reducing the morbidity and mortality from COVID-19 globally.6–8 This is particularly relevant to patients with glomerular disease who may have reduced kidney function and/or are receiving immunosuppressive therapies, both of which are recognized risk factors for developing severe complications of COVID-19.9–12 However, the risks associated with vaccination specific to patients with glomerular disease are currently unknown. Although there was an observed temporal relationship between vaccination and disease flare in published case reports, without appropriately controlling for the baseline risk of relapse in glomerular diseases, it cannot be determined whether this association is causal or due to chance. There are currently no data that accurately describe the relative or absolute risk of disease relapse after COVID-19 vaccination in patients with glomerular disease. Without these critical pieces of information, patients and their health care providers face the difficult task of weighing the proven benefits of vaccination against the theoretical risk of experiencing a disease relapse.

We sought to address this important knowledge gap by evaluating the population-level incidence of glomerular disease relapse after COVID-19 vaccination among adult patients with glomerular disease in British Columbia, Canada. By capturing all patients with biopsy-confirmed glomerular disease in a centralized provincial database with linkage to both longitudinal laboratory data and vaccination status, we were uniquely positioned to model time-varying vaccine exposure in order to quantify the absolute and relative risk of glomerular disease relapse after COVID-19 vaccination accurately.

Methods

Study Design

This was a retrospective population-level cohort study of adult patients ≥18 years old with glomerular disease diagnosed on a native kidney biopsy in British Columbia between January 1, 2000, and December 14, 2020. The following glomerular disease types were included: (1) minimal change disease, (2) FSGS, (3) membranous nephropathy, (4) IgA nephropathy, (5) lupus nephritis, (6) ANCA-GN, and (7) C3 glomerulonephritis. Histologic features and clinical data provided at the time of biopsy were used to exclude patients with an identifiable underlying cause (infection, drugs, other glomerular disease, or systemic autoimmune disease); thus, cases were restricted to those with a higher likelihood of immune etiology. In those with multiple biopsies during the study period, the main underlying glomerular disease at risk of relapse was adjudicated by the study team using manual review of patient-level data. The index date was December 14, 2020, because this was the first day that COVID-19 vaccines became available in British Columbia. Patients were included in the analytic cohort if they satisfied the biopsy criteria and, on the index date, were alive and without kidney failure and were not experiencing a current or recent disease relapse as defined in Supplemental Table 1. The criteria used to define a recent relapse were chosen to exclude patients with worsening or poorly controlled disease before the index date or those who were recently treated with immunosuppression for a disease flare but to include patients whose disease was stable (with or without a complete remission) and who remained at risk of a vaccine-induced disease flare. In addition, patients were excluded if they did not have at least two measurements of proteinuria and kidney function in the 12 months before the index date (if these were required to define a recent relapse). Approval for this study was granted by the research ethics board of the University of British Columbia with waived patient consent.

Data Sources

Patients meeting the inclusion criteria were identified from the British Columbia Glomerulonephritis Registry as previously described,13 which is contained within the provincial information system managed by BC Renal (a government-funded provincial health services organization responsible for the provincial delivery of care to patients with kidney disease, www.bcrenalagency.ca). This database captures all kidney biopsies performed in British Columbia using a standardized coding framework, patient demographics, comorbidities, and laboratory and medication data, along with dialysis and kidney transplantation events, and was linked to a provincial registry of mandatory reporting for COVID-19 vaccinations and PCR COVID-19 test results.

Variable Definitions

Laboratory data at baseline were taken as the closest value preceding the index date. Proteinuria was from 24-hour urine collections; when these were not available, daily urinary protein excretion was estimated from spot urine protein or albumin-creatinine ratios on the basis of established methods, as done previously.14–16 GFR was estimated from provincially standardized creatinine measurements using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration formula.17 Kidney failure was defined as the first occurrence of permanent dialysis or kidney transplantation. The primary outcome was glomerular disease relapse after the index date on the basis of changes in eGFR and proteinuria on the basis of definitions provided in Supplemental Table 2. These disease-specific definitions were chosen to be consistent with clinically relevant thresholds, international guidelines on glomerular diseases and AKI, and clinical trials.18–20 A secondary outcome using a more conservative definition of disease relapse was obtained by manual review of patient-level data by the study team while blinded to vaccine exposure status to select outcome events that were confirmed by repeat laboratory measurements or on the basis of the magnitude of change of laboratory measurements.

Statistical Analyses

Time from the index date to the first occurrence of the primary outcome, censored at death, date of last follow-up, or the end of the study period (September 21, 2021) was modeled using extended Cox regression models, stratified on type of glomerular disease to account for disease-specific differences in baseline risk of relapse. The primary exposure of interest was COVID-19 vaccination status, treated as a time-varying variable. All patients were unexposed to vaccination on the index date. Each individual’s vaccination status was updated over time. Once an individual received a vaccine, they were considered exposed for 30 days from the date of vaccination. At all other times, they were considered unexposed. The comparator was therefore unexposed time periods contributed by all at-risk patients. COVID-19 vaccine exposure was considered to continue for 30 days after vaccine administration to account for the delayed onset of disease relapse as reported in prior studies.1,5 The risk of relapse was evaluated in both a univariable model and a multivariable model that included variables that were considered to be potentially associated with vaccine uptake or relapse risk. To determine whether the relapse risk associated with vaccine exposure differed according to type of glomerular disease, a model was constructed that included an interaction term between disease type and COVID-19 vaccine exposure. These analyses were repeated with the exposure modified to reflect first versus second or third doses of COVID-19 vaccine, and to reflect the type of COVID-19 vaccine as BNT162b2 (BioNTech Pfizer) versus MRNA-1273 (Moderna) versus ChAdOx1 (AstraZeneca). The absolute change in the 30-day risk of disease flare associated with vaccine administration at any given time point during follow-up was derived from the Cox regression models and plotted on a daily basis from day 43 (the first date a second dose of vaccine was administered in the cohort) to day 210 (30 days after the median time to second vaccine dose in the cohort). Further details are provided in the Supplemental Methods.

Five sensitivity analyses were performed as follows: (1) the time window used to define vaccine exposure was increased from 30 to 45 days to account for more delayed onset relapses; (2) the analysis was repeated using the secondary outcome; (3) the primary analysis was repeated among those who received at least one vaccine dose; (4) the primary analysis was repeated among those who received at least two vaccine doses; and (5) the relative rate of relapse associated with vaccine exposure was assessed using an alternative study design called a self-controlled case series that was conducted only in patients who experienced a disease relapse. This method compares the risk of relapse during the 30-day vaccine exposure window with all time periods unexposed to vaccination within the same individual, thus eliminating confounding (measured or unmeasured) for patient-level time-invariant variables.21 Further details about this method are provided in the Supplemental Material.

Categorical variables are reported as frequency (percentage) and continuous variables as median (interquartile range). The analysis was performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

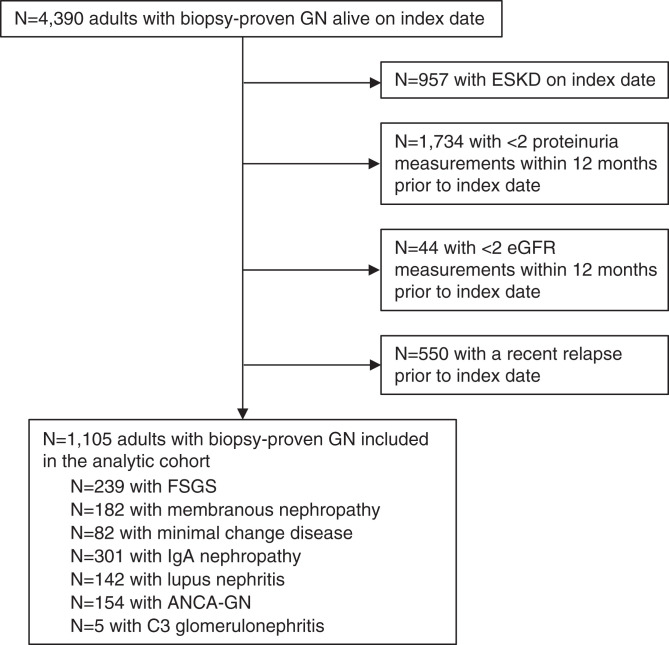

The analytic cohort comprised 1105 patients, including 301 with IgA nephropathy, 239 with FSGS, 182 with membranous nephropathy, 154 with ANCA-GN, 142 with lupus nephritis, and 82 with minimal change disease (Figure 1). Characteristics of the cohort are provided in Table 1. During 281 days of follow-up, 1016 (92%) patients received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose, and 986 (89%) patients received two or three doses. The most common types of vaccines were BNT162b2 (BioNTech Pfizer; 67%) and MRNA-1273 (Moderna; 30%). Among patients who received at least two vaccine doses, 859 (87%) received two doses of the same type, 97 (10%) received one MRNA-1273 and one BNT162b2 dose, and 30 (3%) received ChAdOx1 (AstraZeneca) with either MRNA-1273 or BNT162b2. COVID-19 infection occurred in 16 patients, of whom 14 cases were before the first vaccine dose and none within 30 days after a vaccine dose.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of case ascertainment. After applying the exclusion criteria, a total of 1,105 patients with stable biopsy-proven glomerulonephritis (GN) were included.

Table 1.

Description of the analytic cohort on the index date

| Characteristics | Analytic Cohort |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 1105 |

| Duration of follow-up (d) | 281 (281–281) |

| Glomerular disease type | |

| ANCA-GN | 154 (14) |

| C3 glomerulonephritis | 5 (0.5) |

| FSGS | 239 (22) |

| IgA nephropathy | 301 (27) |

| Lupus nephritis | 142 (13) |

| Class III | 39 (27) |

| Class IV | 44 (31) |

| Class V | 17 (12) |

| Class III/IV+V | 28 (20) |

| Other | 14 (10) |

| Minimal change disease | 82 (7) |

| Membranous nephropathy | 182 (16) |

| Age (yr) | 59.8 (46.6–70.6) |

| Men | 522 (47) |

| Proteinuria (g/d) | 0.4 (0.1–1.1) |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 51 (32–78) |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 116 (82–167) |

| Albumin (g/L) | 42 (40–44) |

| Immunosuppressive medication use on index date | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine | 194 (18) |

| Tacrolimus or cyclosporine | 109 (10) |

| Cyclophosphamidea | 10 (1) |

| Prednisone | 111 (10) |

| Rituximaba | 28 (3) |

| Time from biopsy to index date (yr) | 5.3 (2.6–10.9) |

| Worsening disease activity between 1 and 2 years before the index dateb | 58 (5.2) |

| COVID-19 infectionc | |

| Before index date | 5 (0.5) |

| After index date | 16 (1) |

| COVID-19 vaccination status | |

| Received at least one dose | 1016 (92) |

| Received exactly one dose | 30 (3) |

| Received two or three doses | 986 (89) |

| Type of COVID-19 vaccine (% of total doses received) | |

| BNT162b2 (BioNTech Pfizer) | 1517 (67) |

| MRNA-1273 (Moderna) | 689 (30) |

| ChAdOX1 (AstraZeneca) | 76 (3) |

| Time from index date to first dose (months) | 3.9 (3.5–4.6) |

| Time from first to second dose (months) | 2.3 (2–2.6) |

| Experienced primary outcome (% relapse for each disease category) | |

| Overall cohort | 134 (12.1) |

| ANCA-GN | 14 (9.1) |

| FSGS | 19 (7.9) |

| IgA nephropathy | 45 (14.9) |

| Lupus nephritis | 30 (21.1) |

| Minimal change disease | 7 (8.5) |

| Membranous nephropathy | 18 (9.9) |

| Experienced secondary outcome (% relapse for each disease category) | |

| Overall cohort | 101 (9.1) |

| ANCA-GN | 8 (5.2) |

| FSGS | 18 (7.5) |

| IgA nephropathy | 35 (11.6) |

| Lupus nephritis | 18 (12.7) |

| Minimal change disease | 7 (8.5) |

| Membranous nephropathy | 14 (7.7) |

Data reported as count (frequency) or median (interquartile range).

Intravenous cyclophosphamide and rituximab use includes administration within 6 months before the index date.

On the basis of applying the criteria from Supplemental Table 1 on December 14, 2019 (1 year before the index date), which use a 1-year prior window period from December 14, 2018, to December 14, 2019, to ascertain worsening disease activity. Note that inclusion criteria for this analysis were based on the criteria in Supplemental Table 1 to exclude patients with worsening disease activity in the 1-year period before the index date.

COVID-19 infection is on the basis of positive PCR results from a nasopharyngeal swab.

During the follow-up period, 134 (12.1%) patients developed a disease relapse on the basis on the primary outcome definition, which varied between 7.9% of patients with FSGS and 21.1% of patients with lupus nephritis (Table 1). Disease relapse was ascertained based on creatinine and proteinuria measurements over time (Supplemental Table 2). Among the 1105 patients in the cohort, the frequency of creatinine or proteinuria testing was 0.85 measurements per patient month. Among those who received at least one vaccine dose during follow-up, a similar proportion of patients had a laboratory test performed within 30 days before vaccination and within 30 days after vaccination (41.6% versus 43.5%; P=0.39), suggesting that testing frequency was not correlated with vaccination status. Supplemental Table 3 compares the characteristics of patients who experienced a disease relapse with those patients who did not. Patient characteristics at the time of relapse are shown in Table 2. Proteinuria increased at the time of relapse in all types of glomerular disease, whereas eGFR at the time of relapse was more variable, being most prominently reduced in patients with ANCA-GN and minimal change disease. Of those who relapsed, 24 (18%) patients had a COVID-19 vaccine exposure within 30 days before relapse. The secondary outcome, defined using a more conservative definition for disease relapse on the basis of manual review of patient-level data, occurred in 101 (9.1%) patients. Patient characteristics at the time of relapse on the basis of the secondary outcome are shown in Table 2 and were similar to those using the primary outcome. An exception was patients with lupus nephritis, in whom eGFR was more prominently reduced at the time of relapse using the secondary outcome definition.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients who experienced a disease relapse on the basis of the primary and secondary outcome definitions

| Characteristics | Relapse on the Basis of Primary Outcome | Relapse on the Basis of Secondary Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| In overall cohort | ||

| Number of patients | 134 | 101 |

| Proteinuria at baseline (g/d) | 0.6 (0.3–1.7) | 0.7 (0.4–1.8) |

| Proteinuria at relapse (g/d) | 2.1 (1.1–4.1) | 3.3 (1.3–4.1) |

| eGFR at baseline (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 51 (32–79) | 49 (32–75) |

| eGFR at relapse (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 47 (29–77) | 46 (30–75) |

| Relapse was within 30 days of COVID-19 vaccine | 24 (18) | 21 (21) |

| In patients with ANCA-GN | ||

| Number of patients | 14 | 8 |

| Proteinuria at baseline (g/d) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) |

| Proteinuria at relapse (g/d) | 0.6 (0.6–0.9) | 0.6 (0.6–0.9) |

| eGFR at baseline (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 43 (26–67) | 51 (28–78) |

| eGFR at relapse (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 37 (20–62) | 44 (29–86) |

| Relapse was within 30 days of COVID-19 vaccine | 3 (21) | 2 (25) |

| In patients with FSGS | ||

| Number of patients | 19 | 18 |

| Proteinuria at baseline (g/d) | 2.0 (0.8–2.5) | 2.0 (0.8–2.4) |

| Proteinuria at relapse (g/d) | 4.1 (3.9–4.6) | 4.1 (3.9–4.4) |

| eGFR at baseline (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 35 (25–55) | 35 (25–55) |

| eGFR at relapse (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 34 (18–47) | 34 (18–47) |

| Relapse was within 30 days of COVID-19 vaccine | 3 (16) | 3 (17) |

| In patients with IgA nephropathy | ||

| Number of patients | 45 | 35 |

| Proteinuria at baseline (g/d) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 0.9 (0.5–1.3) |

| Proteinuria at relapse (g/d) | 1.6 (1.2–2.5) | 1.7 (1.2–2.7) |

| eGFR at baseline (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 44 (31–64) | 44 (31–74) |

| eGFR at relapse (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 40 (24–61) | 45 (30–70) |

| Relapse was within 30 days of COVID-19 vaccine | 7 (15) | 6 (17) |

| In patients with lupus nephritis | ||

| Number of patients | 30 | 18 |

| Proteinuria at baseline (g/d) | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) |

| Proteinuria at relapse (g/d) | 1.1 (0.7–1.5) | 1.5 (0.9–1.9) |

| eGFR at baseline (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 76 (43–100) | 69 (32–85) |

| eGFR at relapse (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 77 (33–100) | 58 (29–79) |

| Relapse was within 30 days of COVID-19 vaccine | 4 (14) | 3 (17) |

| In patients with membranous nephropathy | ||

| Number of patients | 18 | 14 |

| Proteinuria at baseline (g/d) | 1.6 (0.7–2.2) | 1.4 (0.6–2.1) |

| Proteinuria at relapse (g/d) | 5.0 (3.9–6.1) | 5.0 (3.9–6.1) |

| eGFR at baseline (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 54 (39–72) | 50 (39–72) |

| eGFR at relapse (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 59 (46–71) | 59 (46–71) |

| Relapse was within 30 days of COVID-19 vaccine | 5 (28) | 5 (36) |

| In patients with minimal change disease | ||

| Number of patients | 7 | 7 |

| Proteinuria at baseline (g/d) | 0.2 (0.1–2.2) | 0.2 (0.1–2.2) |

| Proteinuria at relapse (g/d) | 6.4 (4–7.6) | 6.4 (4–7.6) |

| eGFR at baseline (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 88 (50–94) | 88 (50–94) |

| eGFR at relapse (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 83 (40–94) | 83 (40–94) |

| Relapse was within 30 days of COVID-19 vaccine | 2 (29) | 2 (29) |

Data reported as count (frequency) or median (interquartile range).

Relative Risk of Disease Relapse after COVID-19 Vaccination

The findings from the extended Cox regression models are shown in Table 3. In the overall cohort, exposure to any COVID-19 vaccine was not associated with an increased risk of disease relapse (hazard ratio [HR]=1.08; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.65 to 1.8). An interaction analysis suggested that the relative risk of disease flare associated with any vaccine exposure was not significantly different on the basis of the type of glomerular disease (P value for interaction=0.45). The risk of disease relapse was also estimated separately for exposure to the first dose and second or third doses of COVID-19 vaccine compared with being unexposed. In the overall cohort, a first dose of COVID-19 vaccine was not associated with disease relapse (HR=0.67; 95% CI, 0.33 to 1.36); however, there was a two-fold increase in the risk of disease relapse associated with a second or third dose of COVID-19 vaccine (HR=2.23; 95% CI, 1.06 to 4.71). An interaction analysis suggested that the relative risk of disease relapse associated with either the first dose or with the second or third dose of COVID-19 vaccine was not significantly different on the basis of the type of glomerular disease (P value for interaction=0.51). In a multivariable model that adjusted for patient characteristics at baseline, the risk of disease relapse associated with either the first dose (HR=0.65; 95% CI, 0.32 to 1.32) or with the second or third dose of COVID-19 vaccine (HR=2.16; 95% CI, 1.03 to 4.51) was similar to the unadjusted analysis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relative risk of disease flare associated with COVID-19 vaccine exposure using the primary outcome

| Model | Exposure | HR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | Any vaccine exposure | 1.08 (0.65–1.8) | 0.76 |

| Univariable | First dose | 0.67 (0.33–1.36) | 0.27 |

| Second or third dose | 2.23 (1.06–4.71) | 0.04 | |

| Multivariablea | Any vaccine exposure | 1.06 (0.64–1.76) | 0.83 |

| Multivariablea | First dose | 0.65 (0.32–1.32) | 0.23 |

| Second or third dose | 2.16 (1.03–4.51) | 0.04 |

Vaccine exposure was modeled as a time-varying variable, with exposure continuing until 30 days after vaccine administration. All models were stratified on glomerular disease type and exclude five patients with C3 glomerulonephritis because of too few patients to allow stratification.

Multivariable model was adjusted for sex, age, time from biopsy to the index date, worsening disease activity between 12 and 24 months before the index date, eGFR and proteinuria at index date, hypertension, diabetes, and immunosuppression medication use on the index date.

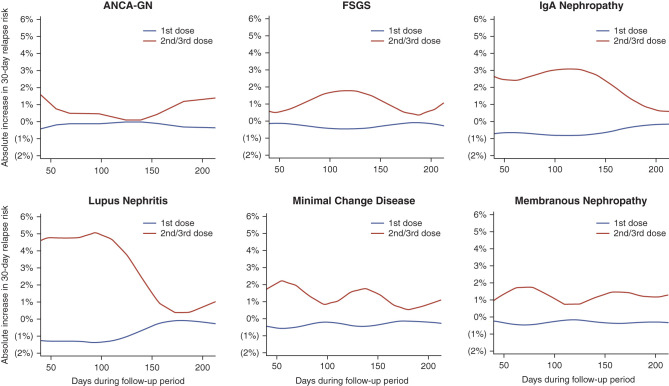

Absolute Risk of Disease Relapse after COVID-19 Vaccination

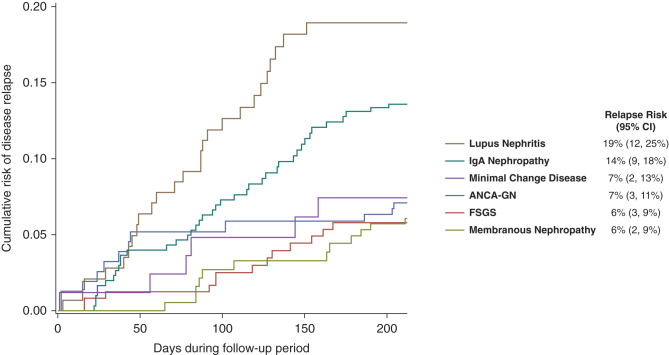

The cumulative risk of a disease flare after 210 days of follow-up in the absence of a COVID-19 vaccine is shown in Figure 2 and ranged from 6% (95% CI, 2% to 9%) in patients with membranous nephropathy to 19% (95% CI, 12% to 25%) in those with lupus nephritis. The increases in absolute risk of a disease flare within 30 days after different doses of vaccine administration are shown in Figure 3. This figure is on the basis of HR estimates and the rate of relapse unexposed to a vaccine within 30 days of each time point during the follow-up period (derived from the baseline survival of the Cox regression model; see Supplemental Material for further details). Because the baseline 30-day risk of a disease flare varied over time, the increase in absolute risk of disease flare associated with vaccine administration also varied over time and is therefore plotted in Figure 3 for all time points during follow-up from day 43 to day 210 in order to provide a range of values that are likely to occur in each type of glomerular disease. The absolute change in risk of a disease flare associated with a first dose of COVID-19 vaccine was near zero for all types of glomerular disease. The absolute increase in risk associated with a second or third dose of a COVID-19 vaccine varied from 1%–2% in those with ANCA-GN, minimal change disease, membranous nephropathy or FSGS to as high as 3%–5% in those with IgA nephropathy or lupus nephritis.

Figure 2.

The cumulative risk of disease flare in the absence of a COVID-19 vaccine. The cumulative risk is from the baseline survival functions from the extended Cox proportional hazards model in Table 3 stratified on type of glomerular disease. Point estimates and 95% CI are provided for the risk of disease flare after 210 days of follow-up, which corresponds to 30 days after the median time to the second vaccine dose in the cohort.

Figure 3.

The absolute change in risk of disease flare within 30 days of COVID-19 vaccine administration at each point during the follow-up period. The absolute change in risk at any given time point is the difference between the 30-day risk of disease flare if a dose of vaccine was administered at that time point and the 30-day risk of disease flare if no vaccine dose was administered within 30 days, assuming no prior disease flare. Because the observed rate of disease flare within 30 days of each time point during follow-up varied over time, the absolute change in risk associated with vaccine administration also varied over time and is plotted for all time points during follow-up from day 43 (the first day a second dose of vaccine was administered in the cohort) to day 210 (30 days after the median time to the second vaccine dose in the cohort). These results should be viewed as providing a range of the increase in absolute risk for each type of glomerular disease. Risk estimates are derived from the extended Cox proportional hazards model in Table 3 stratified on type of glomerular disease and smoothed using locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (see Supplemental Methods).

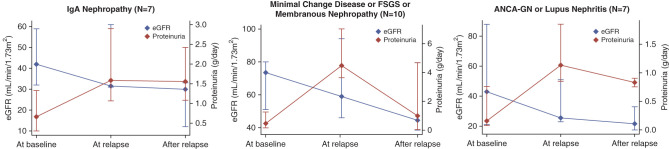

Clinical Course in COVID-19 Vaccine–associated Disease Relapse

The trajectories of eGFR and proteinuria in the 24 patients with a disease flare within 30 days of COVID-19 vaccine administration are shown in Figure 4. Proteinuria increased at the time of relapse in all types of GN, and subsequently remained stable in those with IgA nephropathy and improved over time in those with other types of GN. eGFR decreased over time in all types of GN. Among these 24 patients, four (17%) were treated with an increase or change in immunosuppression, and none of the patients underwent a repeat kidney biopsy after relapse.

Figure 4.

The trajectory of eGFR and proteinuria before and after relapse in the subgroup of 24 patients who experienced a disease flare within 30 days of a COVID-19 vaccine. Values for eGFR and proteinuria are provided at baseline (index date), at the time of disease flare (relapse), and for all values after relapse. Data points are presented as median (diamonds) with interquartile ranges (whisker bars). Types of glomerular disease were grouped on the basis of similar clinical features due to small sample sizes in disease-specific subgroups.

Additional Analyses

A number of sensitivity analyses were performed. First, the window period used to define vaccine exposure status was extended from 30 to 45 days after vaccine administration (Supplemental Table 4). Second, the analysis was repeated using the secondary outcome definition for disease relapse that was on the basis of a manual review of patient-level data (Supplemental Table 5). Third, to remove potential confounding related to vaccine acceptance, the analysis was repeated in those patients who received at least one vaccine dose (Supplemental Table 6) and in those who received at least two vaccine doses (Supplemental Table 7). In all of these analyses, the risk of disease flare associated with any COVID-19 vaccine exposure, or with the first dose and second or third dose, was similar to that from the primary analysis. There was no clear association between the type of COVID-19 vaccine and the risk of disease relapse (BNT162b2 vaccine; HR=0.99 [95% CI, 0.55 to 1.78]; MRNA-1273 vaccine: HR=1.3 [95% CI, 0.58 to 2.99]; ChAdOx1 vaccine: HR=1.64 [95% CI, 0.22 to 12.12]). Finally, a self-controlled case series was conducted in the subgroup of patients who experienced a disease relapse to account for both measured and unmeasured time-invariant confounding. The pattern of results was similar to the HR estimates from the extended Cox regression model (Supplemental Table 8), suggesting minimal unmeasured confounding in the primary analysis results.

Discussion

In this population-level cohort of 1105 adult patients with biopsy-confirmed glomerular disease followed for approximately 9 months, exposure to a second or third dose of COVID-19 vaccine was associated with an increased risk of disease relapse (HR=2.23; 95% CI, 1.06 to 4.71), but exposure to a first dose was not (HR=0.67; 95% CI, 0.33 to 1.36). The pattern of results was consistent when the window period used to define vaccination exposure was increased from 30 days to 45 days, when a more stringent definition of relapse was employed, and when the sample was restricted to patients who received either a single vaccine dose or multiple vaccine doses. Although we observed an increase in the relative risk of relapse after the second or third dose, the absolute increase in the risk associated with vaccine exposure was nonetheless low, underscoring the safety of COVID-19 vaccination in patients with glomerular disease.

This analysis provides the first accurate assessment of the relative and absolute risks of disease relapse associated with COVID-19 vaccination in patients with glomerular disease. Previous data regarding the association between COVID-19 vaccination and the risk of glomerular disease relapse have been limited to isolated case reports or case series. The largest case series to date described five patients from a single institution with preexisting minimal change disease, FSGS, IgA nephropathy, or membranous nephropathy.5 However, such reports are not able to account for the natural history of these diseases that includes a baseline risk of relapse that is independent of vaccination exposure. As illustrated in Figure 2, the disease-specific cumulative risk of relapse in the absence of a COVID-19 vaccine ranged between 6% and 19% during follow-up. Without an appropriate control group, case reports are unable to demonstrate conclusively that a disease relapse in close proximity to a vaccine would not have occurred in the absence of that exposure. The lack of data in unexposed individuals may have overemphasized an unknown and unproven risk, and potentially negatively affected the decision to proceed with vaccination among individual patients and their health care providers. To overcome this limitation, we used a unique population-level cohort in which we could identify all patients who, at the time COVID-19 vaccines became available in British Columbia, were not experiencing a current or recent relapse of their glomerular disease. By modeling vaccination as a time-varying exposure, patients in the cohort could contribute person time in both the exposed and unexposed states. This facilitated accurate estimation of the background risk of disease relapse in the cohort, which could then be compared with the relapse risk that was observed after vaccine administration. This approach provides the first source of population-level data on the risk of relapse in patients with glomerular disease after COVID-19 vaccination.

In the primary analysis, exposure to any COVID-19 vaccine was not significantly associated with relapse of glomerular disease; however, the findings differed by vaccine dose. Whereas the risk of glomerular disease relapse after the first vaccine dose was negligible, the risk increased after the second or third vaccine dose. It should be acknowledged that the HR estimates had wide confidence intervals and need to be validated in an independent cohort with larger sample size to generate more precise estimates. This finding is biologically plausible, however, considering the enhanced immune response that has been observed after repeated COVID-19 vaccination, including higher antibody titers22 and more prominent systemic symptoms of immune activation such as fever, chills, and muscle aches.6,23 In the present analysis, the majority of patients received a mRNA vaccine (BNT162b2 or MRNA-1273), and the relative risk of disease flare was similar across all vaccine types. Among individuals who experienced a disease flare after vaccination, only a minority had a change in immune therapy, and none required a repeat kidney biopsy. This suggests that relapses were mostly mild and self-limiting, although we acknowledge that follow-up time was relatively short and medication dose changes (e.g., modification of immunosuppression or renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors) between prescription events were not necessarily captured in our dataset, which may underestimate the treatment used to control disease relapses. Importantly, the increase in absolute risk of relapse associated with a second or third vaccine dose was low. For example, in patients with ANCA-GN, minimal change disease, membranous nephropathy, or FSGS, our findings suggest one or two additional relapses among every 100 patients in the 30 days after a second or third vaccine dose and at most an additional three to five relapses among every 100 patients with IgA nephropathy or lupus nephritis. These are the first accurate estimates that can be used to educate patients regarding the potential risks of disease relapse after COVID-19 vaccination. Taken together, these findings indicate that patients with glomerular disease should be monitored more carefully after the second or third dose of COVID-19 vaccine but that the absolute increased risk of disease flare is minimal and more than offset by the substantial benefits of vaccination.

Our results did not demonstrate a significant difference in the risk of disease relapse after COVID-19 vaccination across types of glomerular disease. Although there have been several case reports of relapse in patients with minimal change disease, there have been very few reported cases in patients with membranous nephropathy.1,2 Several case reports have described disease flares after COVID-19 vaccination in patients with IgA nephropathy that clinically presented as episodes of gross hematuria.24–26 Because IgA nephropathy is the most common type of glomerular disease worldwide,27 it is not surprising that a sizeable number of reports of disease flares after vaccination have been observed in patients with IgA nephropathy. Given that the definition of disease flare used in this analysis was on the basis of either a change in kidney function or proteinuria, it is possible that we did not capture patients whose disease flare manifested solely as gross hematuria that self-resolved and did not result in any laboratory testing. However, this pattern of disease flare is, by definition, clinically mild, does not require immunosuppressive therapy, and is unlikely to have a long-term effect on kidney function and should therefore not deter patients from being vaccinated against COVID-19.

Our study has a number of limitations. Our definitions of disease-specific relapse were on the basis of changes in laboratory parameters, and a substantial number of patients were excluded from the analytic cohort because they did not have a sufficient number of proteinuria measurements with which to define stability of their glomerular disease at the index date. Similarly, this approach would not have captured patients with a disease flare that did not result in a blood or urine test being performed. It is likely that such events were mostly mild and self-limiting if they did not culminate in a physician requesting a laboratory test for confirmation of relapse. We included patients in this analysis who were not necessarily in remission at baseline but who had stable disease who would be considered for COVID-19 vaccination in clinical practice. There are no universally accepted definitions that can be used to ascertain disease stability at baseline or disease relapse thereafter. We chose definitions on the basis of established criteria from clinical trials and from the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines for the management of glomerular diseases.28 To address this limitation, we generated a secondary outcome definition in which all relapse events were adjudicated after manual review of the data while blinded to the vaccination status of the patients. The results were unchanged when the analysis was repeated using the secondary outcome. Under the assumption of a causal relationship, the appropriate time lag between vaccination exposure and glomerular disease relapse is unknown. We used an exposure window of 30 days on the basis of the range of timelines documented in case reports. In a sensitivity analysis, we extended the window to 45 days, and the results were similar.

In this population-level cohort of patients with biopsy-proven and clinically stable glomerular disease, exposure to a second or third dose of COVID-19 vaccine was associated with an approximately two-fold higher relative hazard of disease flare. Despite this higher relative risk, the absolute increase in the risk of relapse remained low, and the majority of patients who experienced a vaccine-associated relapse did not require a change in immunosuppression. Our findings indicate that patients with glomerular disease should be monitored more closely after a second or third COVID-19 vaccine but that the established benefits of vaccination in this vulnerable population likely outweigh the small absolute increase in risk of disease relapse.

Disclosures

S. Barbour reports consultancy for Achillion, Alexion, Novartis, Inception Sciences, Pfizer, Vera, and Visterra; research funding from Alexion, Novartis, and Roche; and honoraria from Alexion and Roche. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The BC Glomerulonephritis Registry is funded by BC Renal.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial: “mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines and Their Risk to Induce a Relapse of Glomerular Diseases” on pages 2128–2131.

Author Contributions

M. Atiquzzaman and S. Barbour were responsible for the conceptualization; M. Atiquzzaman, S. Barbour, and M.N. Canney wrote the original draft of the manuscript; M. Atiquzzaman, S. Barbour, M.N. Canney, L. Er, S. Hawken, Y. Zhao, and Y. Zheng were responsible for the methodology; M. Atiquzzaman, L. Er, S. Hawken, and Y. Zheng were responsible for formal analysis; S. Barbour, A. Cunningham, L. Er, S. Hawken, Y. Zhao, and Y. Zheng reviewed and edited the manuscript; S. Barbour and Y. Zhao were responsible for supervision; A. Cunningham was responsible for project administration; and A. Cunningham and Y. Zheng were responsible for data curation.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2022030258/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Definitions used to ascertain a recent disease relapse at the index date.

Supplemental Table 2. Definitions used to ascertain disease relapse after the index date to generate the primary outcome.

Supplemental Table 3. Patient characteristics on the index date associated with the occurrence of glomerular disease relapse during the follow-up period on the basis of the primary outcome definition.

Supplemental Table 4. The relative hazard of disease flare that is associated with COVID-19 vaccine exposure using the primary outcome and a 45-day window period after vaccine administration to define exposure status.

Supplemental Table 5. The relative hazard of disease flare that is associated with COVID-19 vaccine exposure using the secondary outcome.

Supplemental Table 6. The relative hazard of disease flare that is associated with COVID-19 vaccine exposure among patients who received at least one vaccine dose during follow-up (n=1011).

Supplemental Table 7. The relative hazard of disease flare that is associated with COVID-19 vaccine exposure among patients who received at least two vaccine doses during follow-up (n=982).

Supplemental Table 8. Comparison of results from the primary analysis (extended Cox regression model) and the self-controlled case series (SCCS).

References

- 1.Li NL, Coates PT, Rovin BH: COVID-19 vaccination followed by activation of glomerular diseases: Does association equal causation? Kidney Int 100: 959–965, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gueguen L, Loheac C, Saidani N, Khatchatourian L: Membranous nephropathy following anti-COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. Kidney Int 100: 1140–1141, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sekar A, Campbell R, Tabbara J, Rastogi P: ANCA glomerulonephritis after the Moderna COVID-19 vaccination. Kidney Int 100: 473–474, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta RK, Ellis BK: Concurrent antiglomerular basement membrane nephritis and antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-mediated glomerulonephritis after second dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Kidney Int Rep 7: 127–128, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klomjit N, Alexander MP, Fervenza FC, Zoghby Z, Garg A, Hogan MC, et al. : COVID-19 vaccination and glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int Rep 6: 2969–2978, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. ; COVE Study Group : Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med 384: 403–416, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. ; C4591001 Clinical Trial Group : Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med 383: 2603–2615, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dagan N, Barda N, Kepten E, Miron O, Perchik S, Katz MA, et al. : BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in a nationwide mass vaccination setting. N Engl J Med 384: 1412–1423, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akbari A, Fathabadi A, Razmi M, Zarifian A, Amiri M, Ghodsi A, et al. : Characteristics, risk factors, and outcomes associated with readmission in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med 52: 166–173, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ponsford MJ, Ward TJC, Stoneham SM, Dallimore CM, Sham D, Osman K, et al. : A systematic review and meta-analysis of inpatient mortality associated with nosocomial and community COVID-19 exposes the vulnerability of immunosuppressed adults. Front Immunol 12: 744696, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi C, Wang L, Ye J, Gu Z, Wang S, Xia J, et al. : Predictors of mortality in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 21: 663, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kremer D, Pieters TT, Verhaar MC, Berger SP, Bakker SJL, van Zuilen AD, et al. : A systematic review and meta-analysis of COVID-19 in kidney transplant recipients: Lessons to be learned. Am J Transplant 21: 3936–3945, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbour S, Beaulieu M, Gill J, Djurdjev O, Reich H, Levin A: An overview of the British Columbia Glomerulonephritis network and registry: Integrating knowledge generation and translation within a single framework. BMC Nephrol 14: 236, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canney M, Induruwage D, Sahota A, McCrory C, Hladunewich MA, Gill J, et al. : Socioeconomic position and incidence of glomerular diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 367–374, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canney M, Induruwage D, McCandless LC, Reich HN, Barbour SJ: Disease-specific incident glomerulonephritis displays geographic clustering in under-serviced rural areas of British Columbia, Canada. Kidney Int 96: 421–428, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hogan MC, Reich HN, Nelson PJ, Adler SG, Cattran DC, Appel GB, et al. : The relatively poor correlation between random and 24-hour urine protein excretion in patients with biopsy-proven glomerular diseases. Kidney Int 90: 1080–1089, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. ; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Glomerular Diseases Work Group : KDIGO 2021 clinical practice guideline for the management of glomerular diseases. Kidney Int 100: S1–S276, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furie R, Rovin BH, Houssiau F, Malvar A, Teng YKO, Contreras G, et al. : Two-year, randomized, controlled trial of belimumab in lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med 383: 1117–1128, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khwaja A: KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract 120: c179–c184, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersen I, Douglas I, Whitaker H: Self controlled case series methods: An alternative to standard epidemiological study designs. BMJ 354: i4515, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walsh EE, Frenck RW Jr, Falsey AR, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, et al. : Safety and immunogenicity of two RNA-based COVID-19 vaccine candidates. N Engl J Med 383: 2439–2450, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menni C, Klaser K, May A, Polidori L, Capdevila J, Louca P, et al. : Vaccine side-effects and SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination in users of the COVID Symptom Study app in the UK: A prospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis 21: 939–949, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lo WK, Chan KW: Gross haematuria after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in two patients with histological and clinical diagnosis of IgA nephropathy. Nephrology (Carlton) 27: 110–111, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Negrea L, Rovin BH: Gross hematuria following vaccination for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in 2 patients with IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int 99: 1487, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahim SEG, Lin JT, Wang JC: A case of gross hematuria and IgA nephropathy flare-up following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Kidney Int 100: 238, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGrogan A, Franssen CF, de Vries CS: The incidence of primary glomerulonephritis worldwide: A systematic review of the literature. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 414–430, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rovin BH, Adler SG, Barratt J, Bridoux F, Burdge KA, Chan TM, et al. : Executive summary of the KDIGO 2021 guideline for the management of glomerular diseases. Kidney Int 100: 753–779, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.