Abstract

Financial toxicity describes the negative effects of the economic burden of medical care on patients that potentially lead to poor well-being and quality of life. Co-ordinated efforts at the care provider, health system, insurance and government level, supported by emerging research into remedial approaches, are needed to address this problem.

Many medical interventions can have toxic effects on patient health but medical care may also have toxic effects that are financial in nature. The term financial toxicity was coined ~10 years ago to bring attention to the often high costs of cancer treatments and the resulting financial burden and distress on patients and their families. Since then, research into financial toxicity has expanded to many other disease types.

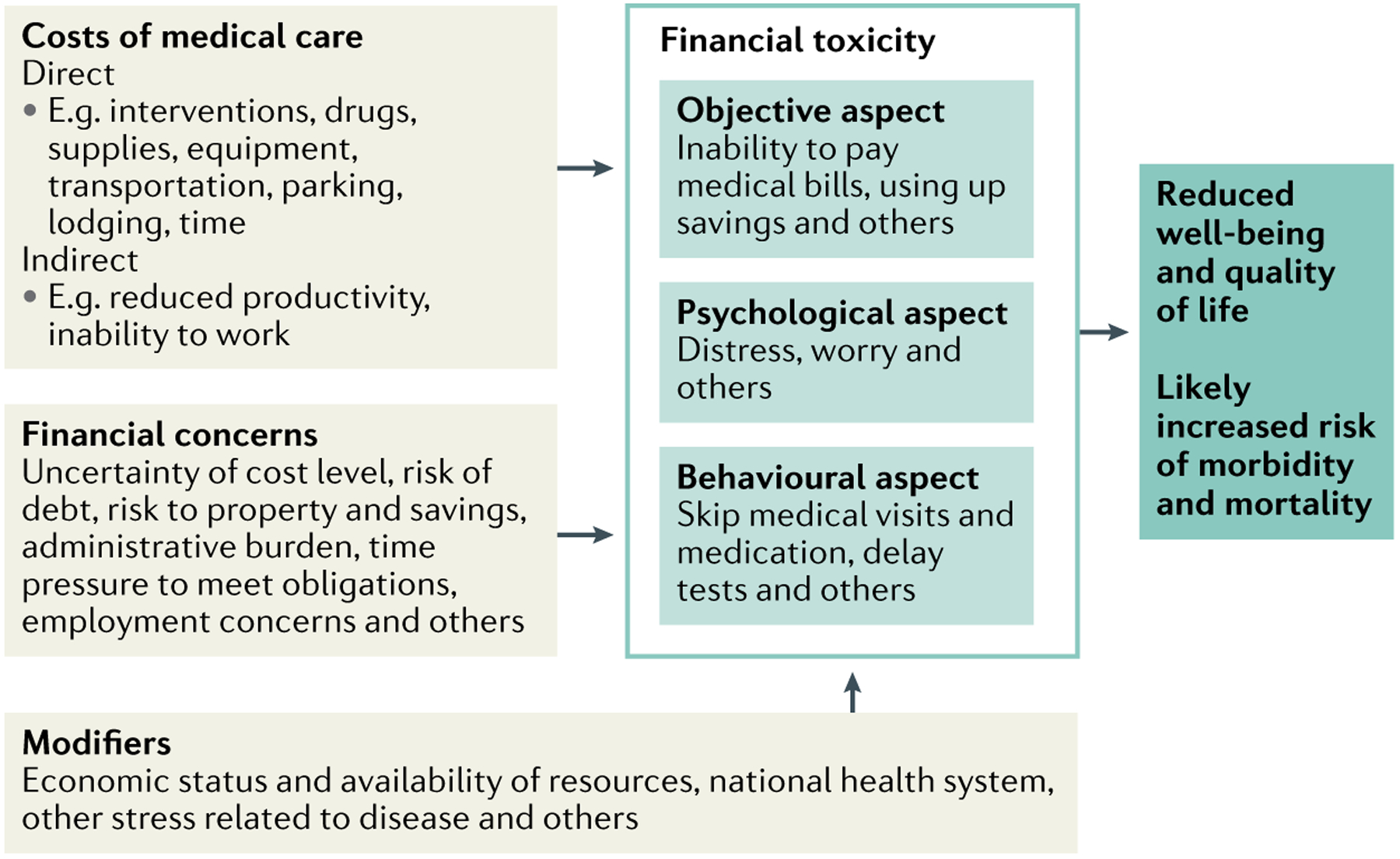

Financial toxicity originates from the numerous expenses required for accessing and receiving medical care, such as doctor’s visits, diagnostic tests, surgery, drugs, equipment, prescribed diets, supporting therapies and follow-up measures (FIG. 1). The costs are paid in full or in part by patients with amounts varying depending on the type of their insurance coverage or their national health system. However, patients also incur other expenses to receive medical treatment, for example, costs of travelling to points of care, meals and lodging away from home. Similarly, patients bear costs related to the time they spend receiving care, potentially taking time off work and losing the opportunity to earn money. Collectively, these costs and expenses add burden and distress to the stress of the disease itself.

Fig. 1 |. Contributors, aspects, modifiers and potential effects of financial toxicity of medical care.

Direct and indirect costs of treatment in addition to financial concerns lead to financial toxicity in various aspects that ultimately affect patient outcomes.

One study from the USA estimated that financial toxicity affects approximately 137 million (56%) of adults, when considering all its aspects in various diseases1. The most common aspect was the psychological burden, such as worry about costs of care, which was reported by 43%. An objective burden, such as not being able to pay medical bills, was reported by 26%1. The portion of adults with financial toxicity varies across diseases: for example, it is reported by 54% of adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and 41% of adults with cancer2.

Financial costs of accessing and receiving medical care are likely unavoidable. However, some patients do not experience financial toxicity, whereas even relatively low costs or simply worrying about potential costs can result in financial toxicity in others. Certainly, many factors contribute to perceiving costs of treatment or managing a disease as stressors, including the underlying economic status of patients and their family and the availability of resources, such as savings or access to financial assistance programmes. Financial toxicity is not limited to those without health insurance, those with few financial resources or those who are unable to pay for treatment for other reasons. Even patients with the means to pay often have to make financial sacrifices, including using up savings or reducing other household expenses. Moreover, distress may arise from an overall uncertainty about how high costs will be, when payments are due and how much, if anything, the insurance will cover. As Lyman and Kuderer write, at least in the USA, “financial toxicity, financial abuse, or financial torture” exists owing to the high costs of care, related uncertainty, payment collection procedures and other factors that lead to physical and mental suffering, which is inflicted, paradoxically, by the same institutions that should heal patients3. Of note, financial toxicity is not unique to the USA, as an increasing number of studies are defining the extent of the problem in regions and health systems worldwide4.

Another important aspect of financial toxicity is the behavioural response of patients in terms of the adjustments patients may make to their medical care when facing or anticipating costs, such as skipping care or medications (FIG. 1). In the study that showed that ~56% of US adults are affected by financial toxicity, behavioural responses, such as delaying or avoiding care owing to worry about costs, were reported by ~20%1. All financial toxicity aspects taken together have consequences on both the physical and mental components of quality of life5. Effects on morbidity and mortality are likely: for example, one study showed that severe financial distress requiring bankruptcy after a cancer diagnosis was a risk factor for mortality6.

Financial toxicity is ubiquitous and will probably never be completely eliminated, and approaches to reduce financial toxicity are still in their infancy. A co-ordinated effort at multiple levels, including the care provider, health system, insurance and government level, is needed to address this problem7. Some of the interventions being tested, such as financial navigation, counselling and education, show promise in overcoming financial, transportation and communication barriers, improving financial management skills, reducing anxiety about costs and reducing behaviours such as skipping medications8. Many advocate for cost conversations between patients and providers and transparency around the cost of treatments, but it is unclear how these would work and whether they would have positive effects7. For example, if cost conversations were implemented, it is important that they do not increase patients’ concerns about receiving recommended treatment but enable them to find resources upfront to reduce costs of treatments and alleviate financial toxicity9. Clearly, as any other symptom or adverse effect of treatment, financial toxicity needs to be identified and intervened upon early to prevent its consequences.

To reduce financial toxicity, it is equally imperative that we expand research, and new frameworks and models are beginning to emerge. For example, a new theoretical model has been proposed in which financial burden (both general and specific to health care) as well as current costs and worry about future costs are examined together, building on psychological theories of stress, depression and anxiety, to explain their effect on quality of life, morbidity and mortality10. We, the authors, are also spearheading research to better understand how financial toxicity affects emotional well-being, that is, well-being intended broadly as the state of patients’ emotions and a reflection on life satisfaction and ability to pursue personal goals. Within our Emotional Well-being and Economic Burden Research Network (EMOT-ECON), we conceptualize the economic burden of disease as a stressor and seek to understand how coping with the stress affects emotional well-being, and how emotional well-being, through biopsychosocial pathways, affects quality of life and health outcomes. Bringing together researchers from several government agencies and cancer-focused non-profit professional and patientadvocacy organizations, the Interagency Consortium to Promote Health Economics Research on Cancer (HEROiC) aims to inform clinical practice and policy to improve access to cancer care and reduce cancer’s economic burden and related financial hardship. Similarly, the Costs of Care NGO is led by researchers who focus their work on helping clinicians and health systems provide affordable and equitable care. Only through these research efforts will we fully understand how important and urgent eliminating financial toxicity truly is.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful for funding for the Emotional Well-being and Economic Burden Research Network from the National Center For Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) and the Office Of The Director of the National Institutes Of Health (OD) (U24AT011310).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Yabroff KR, Zhao J, Han X & Zheng Z Prevalence and correlates of medical financial hardship in the USA. J. Gen. Intern. Med 34, 1494–1502 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valero-Elizondo J et al. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, cancer, and financial toxicity among adults in the United States. JACC CardioOncol. 3, 236–246 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyman GH & Kuderer N Financial toxicity, financial abuse, or financial torture: let’s call it what it is! Cancer Invest. 38, 139–142 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitch MI, Sharp L, Hanly P & Longo CJ Experiencing financial toxicity associated with cancer in publicly funded healthcare systems: a systematic review of qualitative studies. J. Cancer Surviv 10.1007/s11764-021-01025-7 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon LG, Merollini KMD, Lowe A & Chan RJ A systematic review of financial toxicity among cancer survivors: we can’t pay the co-pay. Patient 10, 295–309 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsey SD et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol 34, 980–986 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley CJ, Yabroff KR & Shih YT A coordinated policy approach to address medical financial toxicity. JAMA Oncol. 7, 1761–1762 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel MR et al. A scoping review of behavioral interventions addressing medical financial hardship. Popul. Health Manag 24, 710–721 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pisu M et al. Perspectives on conversations about costs of cancer care of breast cancer survivors and cancer center staff: a qualitative study. Ann. Intern. Med 170 (Suppl. 9), 54–61 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones SM, Henrikson NB, Panattoni L, Syrjala KL & Shankaran V A theoretical model of financial burden after cancer diagnosis. Future Oncol. 16, 3095–3105 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]