Abstract

Polymorphisms in PapA, the major structural subunit and antigenic determinant of P fimbriae of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli, are of considerable epidemiological, phylogenetic, and immunotherapeutic importance. However, to date, no method other than DNA sequencing has been generally available for their detection. In the present study, we developed and rigorously validated a novel PCR-based assay for the 11 recognized variants of papA and then used the new assay to assess the prevalence, phylogenetic distribution, and bacteriological associations of the papA alleles among 75 E. coli isolates from patients with urosepsis. In comparison with conventional F serotyping, the assay was extremely sensitive and specific, evidence that papA sequences are highly conserved within each of the traditionally recognized F serotypes despite the diversity observed among F types. In certain strains, the assay detected serologically occult copies of papA, of which some were shown to represent false-negative serological results and others were shown to represent the presence of nonfunctional pap fragments. Among the urosepsis isolates, the assay revealed considerable segregation of papA alleles according to O:K:H serotype, consistent with vertical transmission within clones, but with exceptions which strongly suggested horizontal transfer of papA alleles between lineages. Sequencing of papA from two strains that were papA positive by probe and PCR but F negative in the new PCR assay led to the discovery of two novel papA variants, one of which was actually more prevalent among the urosepsis isolates than were several of the known papA alleles. These findings provide novel insights into the papA alleles of extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli and indicate that the F PCR assay represents a versatile new molecular tool for epidemiological and phylogenetic investigations which should make rapid, specific detection of papA alleles available to any laboratory with PCR capability.

P fimbriae, the principal mannose-resistant adherence organelles of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli, mediate Gal(α1-4)Gal-specific binding to glycolipid isoreceptors on host epithelial cells, thereby contributing to pathogenesis by promoting bacterial colonization of host tissues and stimulating an injurious host inflammatory response (11, 33, 34). P fimbriae are antigenically diverse, occurring in 11 known serological variants, which are termed F7-1, F7-2, and F8 to F16 according to the system of Ørskov et al. (18, 64, 68, 70). Whereas Gal(α1-4)Gal-specific binding is mediated by PapG, the fimbrial tip adhesin molecule (29, 56), the antigenic diversity of P fimbriae is attributable to peptide sequence variability within PapA, the major P fimbrial structural subunit (12, 13, 22, 55, 57, 96). PapA is present in hundreds to thousands of identical copies per fimbria and is encoded by the corresponding gene, papA (12, 57). Wild-type E. coli strains can contain up to three copies of the pap operon and, since each pap operon can have a different variant (allele) of papA, can express up to three different P fimbrial (F)-antigen types each (1, 18, 67, 68, 70, 75–77).

The evolution of antigenic diversity within PapA may have been driven by selective pressure from the host immune system (8, 12, 96). P fimbriae are expressed in vivo within the urinary tract during infection and appear to be physiologically relevant immunogens (2, 17, 49, 54, 73, 87). They also are effective antigenic targets for a protective host humoral immune response (48, 52, 71, 81). Thus, avoidance of the host immune attack would be predicted to favor a diverse PapA antigenic repertoire in the E. coli population as a whole and even within individual strains, which may be able to switch the expression of their various papA alleles on or off through phase variation (62, 68, 78, 94).

Knowledge of the F antigen status of wild-type E. coli strains can be valuable in several ways. First, independent of its pathogenetic significance, the F antigen can serve as a typing tool to help differentiate strains, much as do the O, K, and H antigens of conventional E. coli serotyping (18, 65, 70). Second, since F antigens are markers for the corresponding papA alleles, they can be used to trace the vertical or horizontal transmission of particular pap variants within the E. coli population, e.g., as defined by O:K:H serotypes, and in relation to other virulence factors (61, 70, 72, 74). Third, epidemiological analyses of F types among strains from defined clinical syndromes or host populations can reveal the clinical associations of particular F variants, which could help guide future efforts to develop and deploy an anti-PapA vaccine (12, 63, 64).

The current “gold standard” method for F determination involves rocket immunoelectrophoresis and crossed-line immunoelectrophoresis (67, 68), demanding techniques which require highly specialized equipment, skills, and F-specific antisera; hence, at present it is largely confined to a single laboratory (88). Consequently, few studies have been done regarding associations of F antigens with other bacterial properties, clonal markers, or clinical syndromes. F-specific monoclonal antibodies, which can be used in (more widely available) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (68), have been developed, but they have been developed for only a subset of the known F types (1, 15–18, 68) and have not come into general use.

Previous efforts to exploit DNA sequence polymorphisms for typing of papA variants by restriction endonuclease analysis (19) or with a battery of oligonucleotide probes (13) were handicapped by the unavailability of sequence data for the full range of papA alleles. Full-length sequencing of papA from wild-type strains, although highly informative and requiring no prior knowledge of existing papA sequences (8), is impractical for large-scale screening. The recently completed cloning and sequencing of papA variants corresponding to all 11 recognized F types of P fimbriae (7) suggested the possibility of exploiting amplification technology for papA allele determinations. In the present study, we sought to develop and validate a PCR-based assay for the 11 known F-type-specific papA alleles of E. coli and to use this assay to investigate the papA allele repertoire of a collection of well-characterized blood isolates from patients with urosepsis.

(This work was presented in part at the 98th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, abstr. 12200.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Control strains used in derivation and validation of the PCR assay included diverse wild-type strains plus, in many instances, their recombinant pap derivatives (e.g., Tables 1 and 2). The derivation set used in assay development consisted mainly of the source strains for the F type-specific papA sequences on which the PCR assay was based. The derivation set strains (and their respective F types and wild-type parent strains) were HB101/pPIL110-75 (F7-1, from AD110) (99), HB101/pPIL110-75 (F7-2, from AD110) (95), AM1727/pANN921 (F8, from 2980) (25), AM1727/pPIL288-10 (F9, from C1018) (14), MOSBLUE/pF10 (F10, from C1960-79) (this study), AM1727/pPIL291-15 (F11, from C1976) (15), 1442 (F12, wild type) (22), HB101/pRHU845 (F13, from J96) (30), MOSBLUE/pF14 (F14, from C1023-79) (this study), MOSBLUE/pF15 (F15, from C1805-79; present study), and MOSBLUE/pF16 (F16, from C83-83) (this study). The first validation set (Table 1) consisted primarily of strains from the International Escherichia and Klebsiella Center (IEKC), World Health Organization, Copenhagen, Denmark, and included, for most F types, that laboratory's type strain for the particular F type. These were supplemented with diverse other F-typed strains, as available. The second validation set (Table 2) consisted of nine strains, generously provided by Han de Ree, for which the O:K and F serotypes had been previously published (16–18, 68).

TABLE 1.

First validation set strains for F PCR assay

| F serotype(s)

|

F PCR result | Strain name | O:K:H serotype (or source strain, if clone) | Source or reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Putativea | Confirmatory | ||||

| F7-1, F7-2 | NDb | F7-1, F7-2 | AD110 | O6:K2:H1 | 18 |

| F7-1d | ND | F7-1 | MC400/pDAL201B | (AD110) | 55 |

| F7-2d | ND | F7-2 | HB101/pDAL210B | (AD110) | 55 |

| F7-1, F7-2 | ND | F7-1, F7-2 | CFT073 | O6:K2:H1 | 60 |

| F7-1 | ND | F7-1 | DH5α/pKgg201 | (CFT073) | 60 |

| F7-2 | ND | F7-2 | DH5α/pDIW101 | (CFT073) | 60 |

| F7-2 | ND | F7-2 | C952-79 | O6:K2:H1 | IEKC |

| F7-2 | ND | F7-2 | C953-79 | O6:K2:H1 | IEKC |

| F7-2 | ND | F7-2 | C1898-79 | O6:K2:H1 | IEKC |

| F7-2 | ND | F7-2 | 2H4 | O6:K2:H1 | 41 |

| F8 | F8, F10 | F8, F10 | C1253-77 | O18ac:K−:H− | IEKC |

| F8 | F8 | F8, F10 | C1254-77 | O75:K−:H5 | IEKC |

| F8 | F8, F10 | F8, F10 | C351-82 | O18ac:K−:H− | IEKC |

| F8 | F8, F10 | F8, F10 | C405-82 | O18ac:K−:H5 | IEKC |

| F8 | F8, F10e | F8, F10 | C805-83 | O18ac:K−:H− | IEKC |

| F8 | F− | F10 | C659-81 | O1:K51:H− | IEKC |

| F8 | F8 | F8, F10 | C321-82 | O18ac:K−:H− | IEKC |

| F8 | F8 | F8, F10 | C825-83 | O75:K5:H− | IEKC |

| F8 | F8, F12 | F8, F12 | V30b | O16:K1:H− | 41 |

| F9 | F9 | F9, F10 | 3669 | O2:K5:H4 | 12 |

| F9d | ND | F9 | HB101/pDAL200A | (3669) | 12 |

| F9 | F9 | F9, F10 | C1018-79 | O2:K5:H4 | IEKC |

| F9 | F9 | F9, F10 | C481-82 | O1:K1:H− | IEKC |

| F9 | F9, F10e | F8, F9 | C483-82 | O1?:K1:H− | IEKC |

| F9 | F14, F16 | F13, F14, F16 | C878-83 | O4:K12:H5 | IEKC |

| F10 | ND | F10 | C1960-79 | O7:K1:[H1] | IEKC |

| F10 | ND | F10 | C997-79 | O7:K1:H− | IEKC |

| F10 | ND | F10 | C328-82 | O7:K1:H− | IEKC |

| F10 | ND | F10 | C906-83 | O7:K1:H− | IEKC |

| NAc | F− | F10 | G1062a | O4:K7:HR | 38 |

| F11 | F11, F16e | F11, F16 | IA2 | O4:K12:H− | 10 |

| F11 | ND | F11 | HB101/pDC1 | (IA2) | 16 |

| F11 | ND | F11 | C1976-79 | O1:K1:H7 | IEKC |

| F11 | ND | F11 | C974-79 | O1:K1:H7 | IEKC |

| F11 | F10e, F11 | F10, F11 | V31 | O4:K12:H− | 41 |

| F11, F16 | ND | F11, F16 | AFR015 | O4:K+:H− | 45 |

| F11, F16 | F10e, F11, F16 | F10, F11, F16 | BOS040 | O4:K+:H1 | 45 |

| NA | F10, F11, F16 | F10, F11, F16 | JR1 | O4:K7:H1 | 82 |

| F12-1, F12-2 | ND | F12 | C1979-79 | O16K1:H− | IEKC |

| F12-2 | ND | F12 | C493-82 | O6:K13:H1 | IEKC |

| F12-2 | ND | F12 | C438-82 | O75:K5:H5 | IEKC |

| F12-2 | ND | F12 | C469-82 | O75:K95:H5 | IEKC |

| F13 | ND | F13 | J96 | O4:K−:H5 | 44 |

| F13 | ND | F13 | DH5α/pJJ48 | (J96: allele I) | 47 |

| F13 | ND | F13 | HB101/pJFK102 | (J96: allele III) | 51 |

| F13 | F13, F14 | F13, F14 | CP9 | O4:K10,K54/96:H5 | 44 |

| NA | ND | F13 | NM554/pCP9I | (CP9) | This study |

| NA | ND | F14 | NM554/pCP9III | (CP9) | This study |

| F13 | F13, F14 | F13, F14 | BF1023 | O4:K10,K54/96:H5 | 44 |

| F13 | F13, F14 | F13, F14 | BF1056 | O4:K10,K54/96:H5 | 44 |

| F13 | F13, F14 | F13, F14 | BOS038 | O4:K10,K54/96:H5 | 44 |

| F13 | F13, F14 | F13, F14 | BOS110 | O4:K10,K54/96:H5 | 44 |

| F13 | F13, F14 | F13, F14 | 518 | O4:K10,K54/96:H5 | 45 |

| F13 | ND | F13, F14 | 18878 | O4:K10,K54/96:H5 | IEKC |

| F13 | ND | F13 | BF1040 | O4:K3:H5 | 44 |

| F13 | ND | F13 | BF9043 | O4:K3:H5 | 44 |

| F13 | ND | F13 | CA002 | O4:K3:H5 | 45 |

| F13 | ND | F13 | CA062 | O4:K3:H5 | 45 |

| F13 | ND | F9, F13 | CA022 | O4:K3:H5 | 45 |

| F13 | F11,e F13 | F11, F13 | R28 | O4:K3:H5 | 45 |

| F13 | F13, F16 | F13, F16 | 3048 | O4:K−:H− | 31 |

| F13, 16 | ND | F13, 14, 16 | C134-73 | O4:K12:H5 | IEKC |

| F13, F14, F16 | ND | F13, F14, F16 | 20025 | O4:K12:H− | IEKC |

| F14 | ND | F14 | C127-86f | (Unknown) | IEKC |

| F14 | ND | F14 | C 818-83 | O25:H9 | IEKC |

| F14 | ND | F14 | C1023-79 | O83:K24:H31 | IEKC |

| F15 | ND | F10, F15 | C1805-79 | O75:K5:H− | IEKC |

| F15 | F− | F10 | C826-83 | O75:K5:H− | IEKC |

| F15 | F10e, F15 | F10, F15 | C372-82 | O75:K5:H+ | IEKC |

| F15 | F10, F15 | F10, F15 | C394-82 | O75:K5:H− | IEKC |

| F15 | F10e, F15 | F10, F15 | C312-82 | O75:K5:H− | IEKC |

| F16 | ND | F16 | C83-83 | O157:K−:H45 | IEKC |

| F16 | F14, F16 | F14, F16 | PM8 | O4:K12:H− | 41 |

| F16 | F16 | F7-1, F16 | BOS021 | O4:K+:H− | 45 |

| F16 | ND | F16 | BOS046 | O4:K12:H− | 45 |

According to records of the IEKC.

ND, not done.

NA, not applicable.

F type according to reference 12.

Antigen detected only in second or third round of confirmatory serotyping.

Recombinant.

TABLE 2.

Second validation set of strains for F PCR assay

| Straina | Published O:K serotype | Confirmatory O:K:H serotype | Published F type | Confirmatory F serotyping result

|

F PCR result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | |||||

| AD303 | O25:K− | O4:K2:H1 | F11, F16 | F11 | F10, F11 | F10, F11, F16 | F10, F11, F16 |

| AD309 | O77:K− | O77:K16:H4 | F7-1, F11, F12 | F11, F12 | NDd | ND | F11b |

| AD314 | O4:K12 | O4:K12:H1 | F11, F16 | F11 | F10?, F11 | F11, F16 | F11, F16 |

| NS3 | O14:K+ | OR:K?:H6 | F7-1, F13, F14 | F7-2, F13 | ND | ND | F7-2, F13 |

| NS24 | O1:K1 | O1:K1:H7 | F7-1, F11 | F11 | ND | ND | F11 |

| NS25 | O4:K12 | O4:K12:H1 | F11, F16 | F11 | F10, F11, F16? | F10, F11, F16 | F10, F11, F16 |

| NS26 | O83:K24 | O83:K−:H31 | F7-2, F14 | F14 | ND | ND | F14 |

| SP57 | O157:K− | O157:K−:H45 | F16 + ? | F− | F10?, F16 | F16c | F16 |

| SP88 | O157:K− | O157:K−:H45 | F16 + ? | F− | F10?, F16 | F16 | F16 |

Sources of strains and serotypes: AD309, AD314, NS3, NS24, NS25, and NS26, reference 18; SP57 and SP88, reference 68.

Subsequently found to be PCR positive for the new F48 papA allele (but still PCR negative for F12).

A second colony type noted in the serotyping laboratory was serotyped as OR:K−:H45, F10, F16. (This variant was not retested with the F PCR assay.)

ND, not done.

The application set consisted of 75 well-characterized blood culture isolates of E. coli collected from adults with urosepsis in Seattle, Wash., in the mid-1980s. The status of these strains with respect to multiple characteristics, including pap, diverse other virulence factors, O:K:H serotype, carboxylesterase B electrophoretic type, and host compromise status, has been reported previously (35, 39–42). Strains were considered to belong to a particular O:K:H serotype if they exhibited any two of the three corresponding antigens plus no other O, K, or H antigen (41).

Sequencing of papA alleles.

The nucleotide sequences of the F7-1, F7-2, F9, F11, F12, and F13 papA variants were as previously published (4, 22, 93, 97, 98) and as found in the GenBank database under accession no. X02921 (F7-1), M12861 (F7-2), M68059 (F9), L07420 (F11), X62157 (F12), and X61239 (F13). The nucleotide sequences of the F8, F10, F14, F15, and F16 papA variants were experimentally determined. papA was amplified from control strains AM1727/pANN921 (F8 clone, derivation set), C1960-79 (F10 wild type, Table 1), C1023-79 (F14 wild type, Table 1), C1805-79 (F15 wild type, Table 1), and C83-83 (F16 wild type, Table 1) using primers 5′-ctgagaattcaggttgaaattcgc-3′ (forward) and 5′-atgatgaattcggttattgccggtgcgg-3′ (reverse), which are modified from the corresponding pap sequences to provide EcoRI sites for cloning. The resulting papA amplicons were electrophoresed in agarose gel, and the DNA fragments were removed from the gel using the GeneClean Kit (Bio 101, Inc., La Jolla, Calif.). Purified fragments were ligated into the TA cloning vector (Invitrogen, Groningen, The Netherlands) to create plasmids pF8, pF10, pF14, pF15, and pF16, respectively, and transformed into the electrocompetent cells of the TA cloning kit to create the corresponding recombinant papA control strains. Sequencing of the inserts was done with the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method (88) using the Automated Laser Fluorescence sequencer (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). The M13 universal and reverse sequencing primers labeled with Cy5 were used in the AutoRead 1000 Sequencing Kit (Pharmacia, LKB Biotechnology). Three different clones of each fragment were sequenced.

Sequence alignments and dendrogram construction.

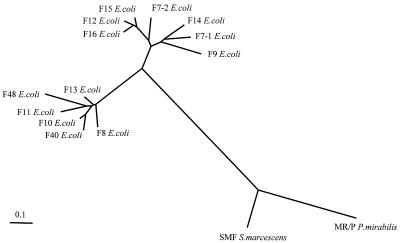

To illustrate the phylogenetic relationships between the PapA variants, an alignment of the predicted mature peptides was made using the CLUSTAL-X program (26). The alignment was then used to calculate a distance matrix from which an unrooted phylogenetic tree was inferred according to the neighbor-joining method (86) using the PHYLIP 3.5c package (21) (Fig. 1). (J. G. Kusters, Department of Medical Microbiology, Free University, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, generously constructed the tree.) For comparison with PapA, the two most closely related known pilin genes from other members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, i.e., MR/P of Proteus mirabilis (5, 6) and SMF of Serratia marcescens (58), were included in the tree (7) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram of PapA variants. Included are the 11 recognized PapA variants (F7-1, F7-2, and F8 to F16), new PapA variants F40 and F48 from the present study, and SMF and MR/P pilins (from S. marcescens and P. mirabilis, respectively). The unrooted tree was based on (predicted) mature peptides and was constructed using the neighbor-joining method (86). The presumed evolutionary distance between any two members of the tree equals the sum of the lengths of the branches connecting them.

F PCR primers.

A universal forward F primer (Ff [5′-ggcagtggtgtcttttggtg-3′]) was selected from the consensus signal sequence region of papA, without regard for peptide structure. To guide selection of immunologically relevant and F-type-specific reverse primers, secondary-structure predictions were made for the 11 translated F-specific PapA peptides using the PlotStructure and PeptideStructure components of the Wisconsin Package (version 5.0; Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.) (32). For each of the 11 PapA sequences, unique peptide regions were identified that were predicted to be hydrophilic (27, 28), surface exposed (20), and antigenic (32) and to contain beta (reverse) turns (9, 23), hence, to be putative F-specific epitopes (89). Candidate reverse primers for each F type were selected from the coding regions corresponding to these putative F-specific epitopes. Since all putative F-specific epitopes for the F12 peptide had corresponding DNA sequences which were suboptimal for use as primers, two compromise F12 reverse primers were chosen. One primer (F12/F15r) corresponded to a predicted antigenic epitope shared with F15, whereas the other (F12r) was unique to F12 at the nucleotide level but corresponded to a predicted nonantigenic peptide region shared by the F12 and F16 variants (not shown).

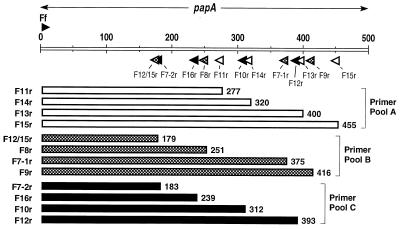

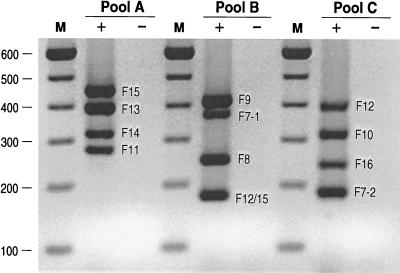

Reverse primers were sorted into three pools of four primers each while maintaining within each pool compatibility between primers and a distribution of product sizes that would allow ready resolution of products in agarose gels (Fig. 2 and 3). Reverse primers were tested in combination with the universal forward primer (Ff), first individually and then in multiples, against single and multiple positive and negative control DNAs. PCR conditions and primer sequences were adjusted as needed to achieve balanced and specific amplification of all F variants with the derivation set strains (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Distribution of primers and amplicons for multiplex F PCR assay. The universal forward primer Ff (forward-pointing arrowhead above the 5′ end of papA), in combination with the reverse primers (backward-pointing arrowheads below papA), yields a PCR amplicon (wide bars) of specific length with template DNA representing each allele of papA. The allele-specific amplicons can be resolved by size in agarose gels when reverse primers are sorted into three pools, i.e., A (white), B (hatched), and C (black).

FIG. 3.

Gel electrophoresis of multiplex F PCR assay products. PCR was done using primer pools A, B, and C (plus universal forward primer Ff) with pooled template DNA from pap-positive control strains representing all 11 known F types (plus lanes) and pap-negative control DNA (minus lanes). Amplicons of the expected sizes appear in each of the positive control lanes. No PCR products appear in the negative control lanes. Lanes M, 100-bp ladder. The values on the left are molecular sizes in base pairs.

F PCR methods.

Amplification was done in a 25-μl reaction mixture containing template DNA (2 μl of boiled lysate [37]), 4 mM MgCl2, the four deoxynucleoside triphosphates at 0.8 mM each, 0.6 μM concentration of each primer (except for those marked with an asterisk below, which were used at a concentration of 0.3 μM), and 2.5 U of AmpliTaq Gold in 1× PCR buffer (Perkin-Elmer, Branchburg, N.J.). The three primer pools, with the reverse primers listed in order of decreasing amplicon size within each pool, were as follows: pool A, *F15r (gctacattcttgccacttgc; 455 bp), F13r (gggtattagcatcaccttcggag; 400 bp), F14r (gcagcatatctttattgttccc; 320 bp), and *F11r (ggcccagtaaaagataattgaacc; 277 bp); pool B, *F9r (aaggccccgttgacgtttt; 416 bp), *F7-1r (tttcacccgttttccactcg; 375 bp), *F8 (gtaccacctacagcacttgg; 251 bp), and *F12/15r (aattcttgggcgttgaggatcca; 179 bp); pool C, *F12r (cccatcgacaagacttgaca; 393 bp), F10r (ctcctcattatgaccagaaaccct; 312 bp), F16r (gttcccgctttattaccagc; 239 bp), and F7-2r (tttgggttgactttccccatc; 183 bp). All three primer pools also contained the forward primer Ff (Fig. 2).

The reaction mixture was heated to 95°C in an automated thermal cycler (PTC-100-96; MJ Research, Watertown, Mass.) for 12 min to activate the AmpliTaq Gold. This initial denaturation was followed by 25 cycles of denaturation (94°C, 30 s), annealing (67°C, 1 min), and extension (72°C, 1.5 min) and a final extension step (72°C, 10 min). Samples were electrophoresed in 2% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, destained with distilled water, and then photographed using a UV transilluminator and digital capture system (Gel Doc; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). The sizes of the amplicons were determined by comparing them to a 100-bp DNA ladder (Gibco-Bethesda Research Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) which was run on the same 2% agarose gel (Fig. 2 and 3).

Confirmation of specificity of F PCR products.

To confirm that a PCR product of a size corresponding to one of the predicted F-specific amplicons actually represented that papA variant, the nucleotide sequence of at least one putative F-specific amplicon was determined for each F type as derived from a strain other than the source strain for the corresponding type-specific papA sequence (Table 3). Amplicons were purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.) or MicroSpin S-300 HR columns (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) and subsequently directly sequenced by the dideoxy-chain termination method (88). Experimentally determined sequences were compared with known papA sequences by using the BLAST algorithm (3) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) to find the closest match in the GenBank, EMBL, DDBJ, and PDB sequence data banks.

TABLE 3.

Confirmation of putative F-specific amplicon sequences

| Source straina | Putative F type of amplicon | Unambiguous nucleotides in sequenced amplicon (no.) | BLAST search result

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best match

|

2nd best match

|

|||||||

| % Identity with best match | F type of best match | Accession no. of best match | % Identity with 2nd best match | F type of 2nd best match | Accession no. of 2nd best match | |||

| CFT073 | F7-1 | 346 | 99.4 | F7-1 | X02921 | 39.6 | F14 | Y08928 |

| CFT073 | F7-2 | 158 | 96.2 | F7-2 | M12861 | 67.1 | F16 | Y08930 |

| C351-82 | F8 | 227 | 97.8 | F8 | Y08931 | 83.7 | ECOR 48e | AF051811 |

| C483-82 | F9 | 339 | 92.6 | F9 | M68059 | 14.2 | F14 | Y08928 |

| 3669b | F10b | 275 | 93.1 | F10 | Y08927 | 60.7 | F13 | X61239 |

| IA2 | F11 | 258 | 95.3 | F11 | L07420 | 77.1 | ECOR 48e | AF051811 |

| C1979-79 | F12 | 359 | 98.3 | F12 | X62157 | 91.9 | F15 | Y08929 |

| C1979-79 | F12/15c | 154 | 98.7 | F12 | X62157 | 98.1 | F15 | Y08929 |

| CP9 | F13 | 367 | 94.3 | F13 | X61239 | 45.0 | F10 | Y08927 |

| CP9b | F14b | 301 | 100 | F14 | Y08928 | 70.4 | F7-1 | X02921 |

| C372-82 | F15 | 427 | 99.7 | F15 | Y08929 | 92.7 | ECOR 46e | AF051810 |

| C372-82 | F12/15d | 156 | 97.4 | F12 | X62157 | 96.8 | F15 | Y08929 |

| IA2b | F16b | 220 | 97.3 | F16 | Y08930 | 89.1 | F15 | Y08929 |

Strains are as shown in Table 1.

The F10, F14, and F16 amplicons from strains 3669, CP9, and IA2, respectively, represented extra F types. Extra F10 amplicons from F8 and F15 control strains C1254-77 and C1805-79 also were confirmed as representing authentic F10 sequence (data not shown).

From F12.

From F15.

F = antigen type not defined.

Detection of papG alleles, other pap elements and virulence factor genes, hemolysin, and hemagglutination.

In selected strains, the three papG alleles were detected using an established allele-specific PCR assay (39). Other pap elements and non-pap virulence factors were detected by PCR and/or by dot blot hybridization (under high-stringency conditions) by using primers, probes, and experimental conditions previously described (43, 46). Hemolysin production was assessed by growth on 5% sheep blood agar. Mannose-resistant hemagglutination (MRHA) was assessed using human A1P1 and sheep erythrocytes, with pigeon egg white used as a specific inhibitor of P fimbriae to differentiate P pattern MRHA from non-P MRHA, as previously described (36).

Cosmid cloning of pap operons from strain CP9.

To isolate each of the two pap operons from control strain CP9 (Table 1) for separate analysis, transformants of pap-negative K-12 host strain NM554 containing a previously constructed cosmid library from strain CP9 (85) were incubated with human or sheep erythrocytes at 4°C in excess α-methyl-d-mannose to allow selective hemadsorption of bacterial clones expressing PapG allele I or III, respectively (38). Following hemadsorption, erythrocytes were extensively washed and then plated on selective agar. Colonies from overnight growth at 37°C which exhibited the appropriate MRHA phenotype were confirmed as containing the appropriate papG allele by PCR (37).

Sequencing of novel papA variants.

Certain strains were positive for papA by dot blot assay and by flanking-primer PCR but were negative with the F PCR assay. Consequently, papAH amplicons from these strains (generated using forward consensus primer Ff and reverse primer PapAr [5′-cgtcccaccatacgtgctcttc-3′] which is from the 5′ end of papH) were directly sequenced as described above for putative F-specific amplicons. Sequences were analyzed as described above for other papA sequences. A specific reverse primer (F48r [5′-gttcattggcttggattg-3′]) which was compatible with the pool A reverse primers was designed for one of these new papA variants (F48) using the approach described above for the other reverse primers and was used to screen selected strains in combination with the universal forward primer Ff.

RAPD fingerprinting.

Random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) genomic fingerprints were generated for selected strains using boiled bacterial lysates as template DNA, Ready-To-Go PCR beads (Pharmacia), decamer primer 1290, and amplification conditions previously described (100). Fingerprints were compared side by side in ethidium bromide-stained 1% agarose gels.

Serological methods.

Historical O:K:H and F types were from the literature or from the records of the IEKC. Confirmatory serotyping was done for selected strains as part of the present study by the IEKC. Lipopolysaccharide (O), capsular (K), and flagellar (H) antigens were determined by using the established typing sera and methods specified by Ørskov and Ørskov (66). F determination was done by using rocket immunoelectrophoresis, followed by crossed-line immunoelectrophoresis, as previously described (68). For selected strains, 10× concentrated F10 antiserum was used to enhance detection of the F10 antigen.

Statistical methods.

Comparisons of proportions were tested using Fisher's exact test with a significance threshold of P < 0.05.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences determined in this study have been deposited in GenBank under accession no. Y08931 (F8), Y08927 (F10), Y08923 (F14), Y08929 (F15), and Y08930 (F16).

RESULTS

Derivation set.

After optimization of assay conditions and primer sequences, the F PCR assay yielded the predicted F-specific amplicon(s) for each of the 11 control strains in the derivation set without cross-reactivity between F types. With pooled template DNAs, robust amplicons could be generated simultaneously in a single reaction mixture for all four of the F types represented within each primer pool and products could be readily resolved in agarose gels (Fig. 3).

First validation set.

Among the 73 strains in the first validation set, many PCR-serotype discrepancies were encountered (Table 1). Thirty-seven (51%) of the strains exhibited at least one such discrepancy. All 37 discrepant strains had an F type detected by PCR that was not expected based on known serological data (i.e., a putative false-positive PCR result); three also had a presumed serological F type that was not detected by PCR (i.e., a putative false-negative PCR result). The putative false-positive PCR results consisted mostly of F10, F14, or F16 PCR products appearing in strains which were not known to be serologically positive for these F types. Thus, although the PCR assay appeared to be highly sensitive for detection of serologically known F types, its specificity was less clear.

Three explanations were considered as possible explanations for the observed PCR-serology discrepancies, including (i) PCR contamination, (ii) nonspecific amplification due to primer cross-reactivity, and (iii) the true presence of (serologically occult) heterologous copies of papA. The first possibility, PCR contamination, was ruled out by a series of reproducibility experiments (data not shown). To differentiate between the second and third possibilities, DNA sequences were determined for representative (putative) F10-, F14-, and F16-specific amplicons from control strains 3669, CP9, and IA2, respectively, in which these products were serologically unexpected, and also for the expected F PCR amplicons from these strains (i.e., F9, F13, and F11, respectively). In each instance, the closest match in the sequence data banks for a strain's “extra” F amplicon corresponded to the strain's PCR-detected extra F type rather than with its known serological F type, whereas the closest match for the strain's serologically predicted F amplicon was the corresponding control papA sequence (Table 3). Similar direct sequence confirmation that the strain's unexpected putative F10 amplicon represented the authentic F10 papA sequence was obtained for F8 and F15 control strains C1254-77 and C1805-79 (data not shown). These results excluded primer cross-reactivity and, instead, strongly suggested the presence of true (serologically unrecognized) heterologous copies of papA in the extra-F strains.

As a second proof of the presence of serologically occult papA copies, the two pap operons from strain CP9 (which gave an unexpected F14 amplicon, as well as the expected F13 amplicon) (Table 1) were isolated as separate cosmid clones for independent analysis. Both cosmid clones expressed P pattern MRHA, evidence that the pap operons they contained were functional. One clone was nonhemolytic, contained papG allele III by PCR, and yielded the F13 product in the F PCR assay (Table 1). The other was strongly hemolytic, contained papG allele I by PCR, and yielded the F14 product in the F PCR assay (Table 1). Thus, the sum of the F PCR results for CP9's two pap cosmid clones equaled the F PCR result for the wild-type parent. These findings confirmed the presence in CP9 of two independent and fully functional copies of the pap operon, each with its own papA allele, as predicted by the F PCR assay.

Further evidence that detection by PCR of multiple F types correlates with the presence of multiple discrete copies of papA was provided by F PCR analysis of strain CFT073 and of cosmid clones representing its two pap operons, which were known to produce different-size pilins (60); hence, the two pap operons were hypothesized to contain distinct papA alleles. The wild-type parent was F7-1 plus F7-2 by PCR, and the two cosmid clones were F7-1 and F7-2, respectively. These results were subsequently confirmed by serology (Table 1). (Discovery of the same F profile in strain CFT073 as in F7-1, F7-2 control strain AD110 [Table 1] prompted RAPD fingerprinting of both of these O6:K2:H1 strains, which confirmed a close genomic relationship between them [data not shown].)

The above-described series of experiments suggested that most of the putative false-positive F PCR results actually represented the presence of true papA copies which either were not expressed or were expressed but not detected serologically. To differentiate between these two possibilities, selective confirmatory reserotyping was done using state-of-the-art methods (including, when indicated, 10× concentrated F10 antiserum) for 33 of the 37 strains from the first validation set for which discrepancies had been noted between the F PCR and historical F serotypes.

Repeat serological testing brought serology into agreement with PCR for 21 (64%) of the 33 previously discrepant strains, confirming that most of the initially observed PCR serology discrepancies represented serological false negatives. The 12 strains which, after confirmatory serotyping, had persisting discrepancies included 11 instances of a PCR-detected extra F type, mostly F10 in an F8-, F9-, or F15-positive control strain, and a single instance of a serological F type (a newly identified F10) not detected by PCR.

To clarify whether these residual PCR-serological discrepancies were due to nonexpression of papA versus expression of papA without serological detection, the three remaining extra-F strains (C659-81, G1062a, and C826-83) which were F PCR positive only for their extra F type (i.e., F10) and were serologically F negative, i.e., did not have a second serological or PCR-defined F type to confound the analysis (Table 1), were tested for multiple pap elements, for other adhesin genes, and for MRHA phenotype (Table 4). Two of the strains (C659-81 and C826-83) were found to have a fragmentary pap operon and not to express P-pattern MRHA and, hence, almost certainly did not express an F10 PapA pilin (Table 4). In contrast, strain G1062a had a complete copy of pap and expressed P pattern MRHA, consistent with P fimbrial expression. With F10 as its sole papA allele, this strain would be expected to express P fimbriae of the F10 type. Thus, this strain's F seronegativity seemed probably to represent a serological false negative.

TABLE 4.

Adhesin genotypes and phenotypes of three control strains positive for F10 by PCR but not by serology

| Strainb | O:K:H serotype | F serotype

|

PCR | Adhesin genotypea

|

MRHA pattern | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Putativec | Confirmedd | papAH | papC | papEF | papG | papG allele | afa/draBC | sfaS | ||||

| C659-81 | O1:K51:H− | F8 | F− | F10 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | Non-P |

| G1062a | O4:K7:Hr | NAe | F− | F10 | + | + | + | + | III | − | − | P |

| C826-83 | O75:K5:H− | F15 | F− | F10 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | −f |

As determined by PCR, except for papAH in strain C826-83 (PCR negative, probe positive for papAH). +, wild type; −, mutant.

Strains C659-81 (alias FS09) and C826-83 (alias FS30) were from the IEKC laboratory. Strain G1062a (alias C892-97) was from the J.R.J. laboratory (Table 1).

Based on historical serotyping results for strains from the IEKC.

Including with 10× concentrated F10 antiserum.

NA, not applicable (strain G1062a was first serotyped during the present study).

−, HA negative.

Second validation set.

Among strains in the second validation set, although agreement was poor between F PCR and both the historical and the (initial) confirmatory F serotype results, correspondence of PCR to serology improved as serological F profiles were refined in successive rounds of confirmatory serotyping (Table 2). By the third round of serotyping, serology agreed with PCR with respect to the F profile of eight of the nine strains and for 15 (94%) of the 16 F types detected by one or both methods (Table 2). These findings confirmed that conventional F serotyping often substantially underestimates the potential F repertoire of wild-type P-fimbriated strains and that most PCR serotype discrepancies are due to false-negative serological results rather than to PCR false positivity.

Prevalence of papA variants among 75 urosepsis isolates.

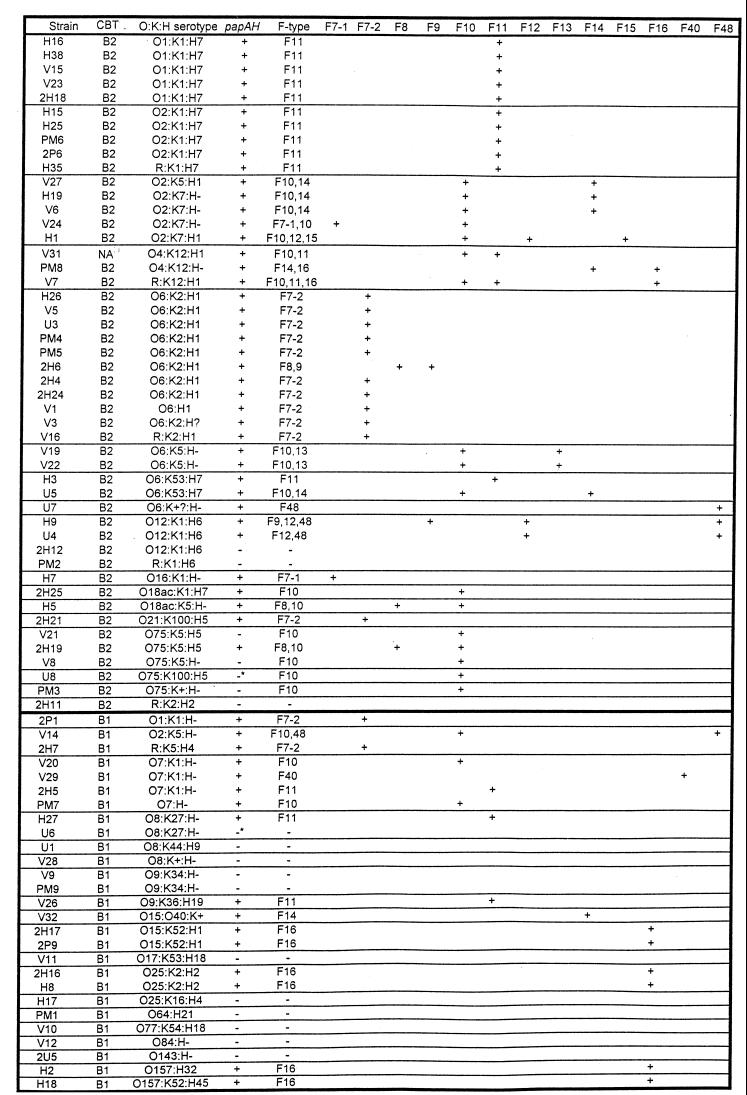

With its sensitivity and specificity rigorously confirmed, the F PCR assay was next used to assess the papA allele status of 75 blood isolates from patients with urosepsis. Fifty-nine (79%) of the 75 strains were found by PCR to contain one or more of the 11 known papA alleles. Of the F PCR-positive strains, 44 had a single F type, 13 had two F types, and 2 had three F types, for a total of 76 detected F types (Fig. 4). Each of the 11 known F types occurred at least once in the population, in decreasing order of prevalence, as follows: F10, 27% (20 strains); F11, 21% (16 strains); F7-2, 17% (13 strains); F16, 11% (8 strains); F14, 8% (6 strains); F8 and F12, 4% (3 strains) each; F7-1, F9, and F13, 3% (2 strains) each; F15, 1% (1 strain). Thus, the three most prevalent F types (F10, F11, and F7-2) accounted for nearly two-thirds (64%) of the F types detected. F7-2, F11, and F16 tended to occur alone (33 [89%] of 37 occurrences), whereas F8, F9, F12, F13, F14, and F15 usually occurred in combination with another F type (15 [88%] of 17 occurrences). The remaining F types (F7-1 and F10) occurred both alone and in combination, each with approximately the same frequency (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

papA alleles among 75 E. coli isolates from patients with urosepsis. Strains are sorted according to O:K:H serotype within each carboxylesterase B type (CBT). Results for papAH are shown as positive if the blot and PCR assays were both positive, as negative if the blot and PCR assays were both negative, and as negative with an asterisk if the blot assay was positive but the PCR assay was negative. F PCR results are listed in the aggregate and also shown distributed according to individual F types. Serogroup O75 strains V21, V8, and PM3 (shown as papAH-negative) exhibited trace reactivity with the papAH probe in some blots. Carboxylesterase B data are from reference 39, O:K:H data are from reference 41, and papAH data are from reference 46. NA, not assayed.

Phylogenetic distribution of papA alleles among urosepsis isolates.

Several of the papA alleles exhibited a clear-cut phylogenetic distribution, as evidenced by their strong associations with particular O:K:H serotypes (which usually equate with genetic clonal groups) or carboxylesterase B types (Fig. 4; Table 5). It is noteworthy that although F10 was significantly associated with carboxylesterase B type B2 in general, it was most highly correlated specifically with serogroup O75 (Table 5). Similarly, although F16 was significantly associated with carboxylesterase B type B1 in general, this was due to its independent strong associations with three small subgroups among the B1 strains, i.e., O15:K52:H1, O25:K2:H2, and serogroup O157 (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Association of F-specific papA alleles with serotype and carboxylesterase B type among 75 E. coli urosepsis isolates

| papA allele (no. of isolates) | Group | No. with papA allele/total (%)

|

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group members | Other strains | |||

| F7-2 (13) | O6:K2:H1 | 10/11 (91) | 3/64 (5) | <0.001 |

| F10 (20) | Carboxylesterase B type B2 | 17/48 (35) | 3/27 (11) | 0.03 |

| Serogroup O75 | 5/5 (100) | 15/70 (21) | <0.001 | |

| F11 (10) | O1:K1:H7, O2:K1:H7 | 10/10 (100) | 56/65 (9) | <0.001 |

| F12 (3) | O12:K1:H6 | 2/4 (50) | 1/71 (1) | 0.006 |

| F13 (2) | O6:K5:H− | 2/2 (100) | 0/73 (0) | <0.001 |

| F14 (6) | O2:K5:H1, O2:K7:H1 | 3/5 (60) | 3/70 (4) | 0.003 |

| F16 (8) | O4:K12:H1 | 2/3 (67) | 6/72 (8) | 0.03 |

| Carboxylesterase B type B1 | 6/27 (22) | 2/48 (4) | 0.02 | |

| O15:K52:H1 | 2/2 (100) | 6/73 (8) | 0.01 | |

| O25:K2:H2 | 2/2 (100) | 6/73 (8) | 0.01 | |

| O157 | 2/2 (100) | 6/73 (8) | 0.01 | |

| F48a | O12:K1:H6 | 2/4 (50) | 2/71 (3) | 0.01 |

The F48 allele was discovered as part of present study.

Associations of papA variants with other bacterial traits among urosepsis isolates.

Several of the papA variants exhibited statistically significant associations with specific bacterial traits, including other papA alleles (Table 6). F7-2 was highly correlated with probe positivity but PCR negativity for the group II capsule synthesis genes kpsMT, a genotype which largely equates with K2 capsule (46). F10 and F14 each exhibited multiple associations with other traits, including an association with one another (Table 6). The association of F11 with the K1 variant of kpsMT (Table 6) was consistent with its association with serotypes O1:K1:H7 and O2:K1:H7 (Table 5). In keeping with the association of F16 with serogroup O4 (Table 5), F16 was also associated with the O4 lipopolysaccharide synthesis gene rfc (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Association of F-specific papA alleles with other bacterial traits among 75 E. coli urosepsis isolates

| papA allele (no. of isolates) | Associated trait | No. with papA allele/total (%)

|

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With trait | Without trait | |||

| F7-2 (13) | kpsMT II probe positive, PCR negative | 12/13 (92) | 1/62 (2) | <0.001 |

| F10 (20) | cnf-1 | 8/12 (75) | 12/63 (19) | 0.001 |

| K5 kpsMT II | 16/25 (64) | 4/50 (18) | <0.001 | |

| traT | 9/50 (18) | 11/25 (44) | 0.03 | |

| F11 (16) | K1 kpsMT II | 12/21 (57) | 4/54 (7) | <0.001 |

| F14 (6) | F10 | 4/20 (25) | 2/55 (4) | 0.04 |

| papG allele III | 3/5 (60) | 3/70 (4) | 0.003 | |

| cnf-1 | 4/12 (33) | 2/63 (3) | 0.005 | |

| K5 kpsMT II | 6/25 (24) | 0/50 (0) | <0.001 | |

| F16 (8) | rfc | 2/3 (67) | 6/72 (8) | 0.03 |

| F48a (4) | F12 | 2/3 (67) | 2/72 (3) | 0.006 |

The F48 allele was discovered as part of the present study.

Discovery of novel papA variants.

Two of the urosepsis isolates, U7 and V29, were negative for the 11 known papA alleles according to the F PCR assay but still expressed P pattern MRHA and by both dot blot and PCR contained papAH, papC, papEF, and papG; hence, they were suspected of harboring novel variants of papA. Consequently, the papAH amplicons from these two strains were sequenced, translated into peptides, and compared with the 11 known PapA variants. Both new sequences appeared to represent novel papA alleles, since each was separated from its nearest neighbor in the PapA tree by a distance greater than that separating the two most closely related of the 11 known PapA variants (i.e., F12 and F15) (Fig. 1); one was actually as distant from its nearest neighbor as any of the known PapA variants was from its own nearest neighbor. The new PapA variant from strain V29 (which was termed F40 because of this strain's laboratory code number) was closely related to the F10 peptide (Fig. 1). PapA from strain U7 (which was termed F48) was an outlier member of the cluster that included the F40, F8, F13, F10, and F11 PapA variants (Fig. 1).

When combined with the universal forward primer (Ff), a reverse primer designed for the new F48 papA variant yielded the expected 176-bp amplicon from source strain U7 and did not react with control strains for 11 known F types (data not shown). Reamplification of all 75 urosepsis isolates with the new F48 primer detected a putative F48 papA allele in three additional strains, each of which was already known to contain at least one papA allele (Fig. 4). Direct sequencing of the putative F48 amplicons from these strains confirmed each as bona fide F48 (data not shown). The new F48 papA variant was found to be significantly associated with (but not confined to) serotype O12:K1:H6 (Table 5). It was statistically significantly associated with the F12 papA variant, from which it was quite distant at the nucleotide and peptide levels (Fig. 1 and 2), but not with other bacterial traits (Table 6). Because of this association of F48 with F12, the new F48 primer was used to test the F12 control strains. Although the F12 control strains from the first validation set were negative (data not shown), strain AD309 (second validation set), in which F12 had been detected serologically but not by PCR (which was one of only two instances, among all of the control strains, of a putative false-negative PCR result), was positive with the F48 primer (Table 2).

F10 amplicons from pap-negative O75 strains.

Among the urosepsis isolates, the F PCR assay showed all five representatives of serogroup O75 to contain the F10 papA allele (Fig. 4). This was surprising, since four of these strains had otherwise tested negative for all pap elements by both PCR and (except for one papAH probe-positive strain) dot blot assay. Direct sequencing of the putative F10 amplicons from these five strains confirmed that the amplicons represented the authentic F10 papA sequence (data not shown). Reexamination of the duplicate dot blots for the three putatively pap-negative O75 strains revealed variable faint reactivity with the papAH probe, consistent with the presence of a partial copy of papA, but no reactivity whatsoever with the probes for papC, papEF, and papG (data not shown). These findings, together with those for the serogroup O75 F15 control strain C826-83 (Table 4) and for several of the other serogroup O75 F8 and F15 control strains (first validation set [Table 1]), suggested that wild-type strains of serogroup O75 commonly contain isolated partial copies of the F10 papA allele, with or without a separate (complete) pap operon containing a different papA allele.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we developed and rigorously validated a novel PCR-based assay for the 11 recognized variants of papA, the major pilin gene of E. coli P fimbriae, and then used the assay to assess the prevalence, phylogenetic distribution, and bacteriological associations of the papA alleles among 75 E. coli isolates from patients with urosepsis. The assay was extremely sensitive and specific, evidence that papA sequences are highly conserved within each of the traditionally recognized F serotypes despite the diversity observed among F types. The assay revealed considerable segregation of papA alleles according to O:K:H serotype, consistent with vertical transmission within clones, but with exceptions which strongly suggested horizontal transfer of papA alleles between lineages. Two novel papA variants were identified, one of which was actually more prevalent among the urosepsis isolates than were several of the known papA alleles.

The assay's sensitivity approached 100% for detection of serologically evident F types among the diverse control strains in the two validation sets, evidence that the sequences selected for use as F-specific primers are highly conserved within each serological F type. This suggests that the regions targeted by the primers either encode the actual epitopes responsible for F serospecificity (as intended by our primer design strategy) or, if they do not, are nonetheless tightly linked with them. The high degree of homology observed between entire F-specific amplicons and the corresponding F-specific papA source sequences (Table 3) suggests that type-specific homology is not limited to just the primer-binding regions but is broadly present throughout papA. Full-length sequence analysis of multiple representatives of each F type from phylogenetically distinct backgrounds (8) is needed to more thoroughly evaluate this hypothesis.

The observed patterns of discrepancy between PCR and serology with respect to detection of F types were highly informative. Historically determined serotypes, understandably, did not include certain F types which, at the time of the original serotyping, were uncharacterized or not recognized as corresponding to P fimbriae. This probably accounted for many of the initial discrepancies involving F10, F14, and F16 (F. Scheutz, unpublished data), which constituted the bulk of the extra F types detected by PCR but putatively not by serology (Table 1). Although confirmatory serotyping (which was done initially using standard techniques and reagents and then using intensified methods) did eventually confirm most of the PCR-detectable F types, a small subset remained serologically occult.

At least some of these serologically occult papA variants represented nonfunctional copies (or fragments) of papA, as documented for one of the F15 control strains (O75:K5:H5) (Table 4) and for four of the serogroup O75 urosepsis isolates (Fig. 4). What proportion of the serologically occult papA copies might still be functional under the appropriate conditions (with the possibility of expression, of course, limited to those strains which have an intact pap operon either in cis or in trans to the serologically inapparent papA copy) can only be speculated upon. However, the expression of P pattern MRHA by strain G1062a (Table 4) suggests that at least some of these occult papA copies are functional. In any event, the preponderance of evidence indicated that the residual PCR-positive, serotype-negative discrepancies did not represent false-positive PCR results, at least not in the conventional sense of nonspecific primer binding or contamination, but instead represented detection of true papA sequences.

Alternative explanations for serological nondetection of documented papA alleles, in addition to nonexpression, could include low-level expression (consistent with the demonstrated differences in expression level between different pap operons in a single strain) (55) or expression of an antigenically altered pilin. Either hypothesis would be consistent with the improved serological detection of F10 that was observed in the present study with the use of 10× concentrated antiserum.

The PCR assay provided abundant evidence among both the control strains and the urosepsis isolates of clonal segregation of papA alleles, as reflected by the distribution of certain papA alleles according to O:K:H serotype and carboxylesterase B type. This is consistent with previously reported serological findings (68, 70). Also noted were circumstances suggesting horizontal transfer of papA alleles. These included the appearance of diverse papA alleles in different members of a single O:K:H serotype, e.g., O2:K7:H−, O4:K12:H1, and O7:K1:H− (Fig. 4), and the local predominance of a particular papA allele in evolutionarily distant lineages, e.g., F16 in three non-B2 O:K:H serotypes (O15:K52:H1, O25:K2:H2, and serogroup O157), but also in B2 serotype O4:K12:H1 (Fig. 4; Table 5).

The new assay also facilitated the discovery of novel papA variants by revealing the absence of any of the 11 known papA alleles in two strains that expressed P pattern MRHA and were papAH positive by probe and PCR. Sequencing of the papAH amplicons from these two strains revealed a unique papA variant in each strain. The subsequent detection of one of the new papA variants (F48) in 3 of the 75 urosepsis isolates by using a primer based on the F48 papA sequence illustrates how the F PCR assay can be used to discover new papA alleles and then screen for them. Discovery of a statistically significant association of the new F48 papA variant with F12 prompted retesting of all of the F12 control strains with the new F48 primer, including the strain in which the PCR assay had putatively missed an F12 papA allele. Only the latter strain was F48 positive. We are currently investigating the phenotypic correlates of the F48 papA allele, including the relationship between F48 and F12 (J. R. Johnson, unpublished data).

Further evidence of the PCR assay's utility as a strain typing tool was provided by the close relationship the assay revealed between two archetypal uropathogenic strains, CFT073 and AD110. CFT073 has been used in studies of pathogenesis (59, 60) and is currently under intensive investigation with respect to the distribution and composition of its pathogenicity islands, including through complete sequencing of its genome by the Fred Blattner laboratory (24, 50; H. L. T. Mobley, personal communication). Venerable strain AD110 was the original source of the first two numbered P fimbrial F types (F7-1 and F7-2) (69) and of recombinant derivatives thereof (95, 97) and has been used in many subsequent studies regarding the regulation of the pap operon, P fimbrial structure, and immunological aspects of PapA (12, 13, 55, 79, 80, 101). The finding that CFT073 has the same distinctive F-1, F7-2 papA allele profile as does AD110 called attention to these two strains' shared O6:K2:H1 serotype, which suggested a clonal relationship, as subsequently confirmed by RAPD fingerprinting. Prior to the discovery of strain CFT073's papA allele profile, neither we nor H. L. T. Mobley (from whose laboratory CFT073 originated) were aware of the considerable similarities between these two archetypal uropathogenic strains (Mobley, personal communication). The discovery of these similarities is significant in that it reveals that there has been an (unrecognized) continuum of investigation over the past 2 decades in different laboratories regarding the pathogenetic mechanisms of what may be essentially the same model uropathogenic strain.

In view of the presence of both the F7-1 and F7-2 papA alleles in model pathogens CFT073 and AD110, and occasionally in other O6:K2:H1 strains (68, 70; Johnson, unpublished data), the absence of the F7-1 allele among the O6:K2:H1 urosepsis isolates in the present study is interesting. Almost all of the O6:K2:H1 urosepsis isolates, which constituted the population's single largest clonal group and quite probably equate with virulent clone 4 as described by Korhonen et al. and with clone V of Väisänen-Rhen et al. (53, 90, 92), were positive for F7-2 alone. Whether O6:K2:H1 strains with both F7-1 and F7-2 are simply uncommon enough that by chance alone none was represented in the present study population or whether there are selection factors that favor F7-2-only strains over F7-1-plus-F7-2 O6:K2:H1 strains as agents of urosepsis remains to be determined. It will be useful to survey O6:K2:H1 (and other) E. coli isolates from different extraintestinal syndromes for their papA allele content, in part to assess how generally representative are the strains that have emerged as model uropathogens (55, 60, 83, 84, 91) and in part to determine which F types would be most relevant to include in a syndrome-based PapA vaccine (12). The F PCR assay, which was simple, rapid, and easy to interpret, should greatly facilitate future studies of this sort.

This prediction is supported by the results of a “portability” assessment of the F PCR assay, in which 10 wild-type pap-positive strains of unknown F status plus strain J96 (an F13 control) were independently F typed in three different laboratories in the United States (J.R.J.), Canada (J. Fairbrother), and France (E. Oswald). The latter two laboratories had only just begun to use the assay when the testing was done. Consistent results were obtained for each strain in each laboratory (Johnson, unpublished data; E. Oswald and J. Fairbrother, personal communication, 1999).

In summary, the F-specific papA alleles of extraintestinal E. coli were found to be sufficiently conserved within each F type that highly sensitive and specific detection was possible by PCR using a small set of F-specific oligonucleotide primers. The multiplex PCR assay for the 11 known papA variants as developed and extensively validated in the present study arguably outperformed conventional F serotyping in accurately detecting papA variants. It detected serologically unrecognized papA copies, demonstrated both clonal segregation and horizontal transfer of papA alleles within the E. coli population and facilitated the discovery of two novel papA variants. The F PCR assay represents a versatile new molecular tool for epidemiological and phylogenetic investigation of the diverse papA alleles of extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Grant support for this research included VA Merit Review (J.R.J. and T.A.R.) and National Institutes of Health grants DK-47504 (J.R.J.) and AI-42059 (T.A.R.).

Control strains were provided by Steve Clegg, Johanes de Ree, Betsy Foxman, Sheila and Richard Hull, David Low, Joel Maslow, Harry L. T. Mobley, James Roberts, and Ann Stapleton. J. G. Kusters calculated the PapA tree. Dave Prentiss helped prepare the figures. Diana Owensby helped prepare the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe C, Schmitz S, Moser I, Boulnois G, High N J, Orskov I, Orskov F, Jann B, Jann K. Monoclonal antibodies with fimbrial F1C, F12, F13, and F14 specificities obtained with fimbriae from E. coli O4:K12:H−. Microb Pathog. 1987;2:71–77. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agata N, Ohta M, Miyazawa H, Mori M, Kido N, Kato N. Serological response to P-fimbriae of Escherichia coli in patients with urinary tract infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989;8:156–159. doi: 10.1007/BF01963903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schäffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baga M, Normark S, Hardy J, O'Hanley P, Lark D, Olsson O, Schoolnik G, Falkow S. Nucleotide sequence of the papA gene encoding the pap pilus subunit of human uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1983;157:330–333. doi: 10.1128/jb.157.1.330-333.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahrani F K, Mobley H L T. Proteus mirabilis MR/P fimbriae: molecular cloning, expression, and nucleotide sequence of the major fimbrial subunit gene. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:457–464. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.2.457-464.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahrani F K, Mobley H L T. Proteus mirabilis MR/P fimbrial operon: genetic organization, nucleotide sequence, and conditions for expression. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3412–3419. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3412-3419.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bijlsma I G W, van Dijk L, Kusters J G, Gaastra W. Nucleotide sequences of two fimbrial major subunit genes, pmpA and ucaA, from canine-uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis strains. Microbiology. 1995;141:1349–1357. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-6-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd E F, Hartl D L. Diversifying selection governs sequence polymorphisms in the major adhesin proteins FimA, PapA, and SfaA of Escherichia coli. J Mol Evol. 1998;47:258–267. doi: 10.1007/pl00006383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou P Y, Fasman G D. Prediction of the secondary structure of proteins from their amino acid sequence. Adv Enzymol. 1978;47:45–148. doi: 10.1002/9780470122921.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clegg S. Cloning of genes determining the production of mannose-resistant fimbriae in a uropathogenic strain of Escherichia coli belonging to serogroup O6. Infect Immun. 1982;38:739–744. doi: 10.1128/iai.38.2.739-744.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connell H, Hedlund M, Agace W, Svanborg C. Bacterial attachment to uro-epithelial cells: mechanisms and consequences. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11:50–58. doi: 10.1177/08959374970110011701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denich K, Blyn L B, Craiu A, Braaten B A, Hardy J, Low D A, O'Hanley P D. DNA sequences of three papA genes from uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains: evidence of structural and serological conservation. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3849–3858. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.3849-3858.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denich K, Craiu A, Rugo H, Muralidhar G, O'Hanley P. Frequency and organization of papA homologous DNA sequences among uropathogenic digalactoside-binding Escherichia coli strains. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2089–2096. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.2089-2096.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Ree J M, Schwillens P, Promes L, van Die I, Bergmans H, van den Bosch J F. Molecular cloning and characterization of F9 fimbriae from a uropathogenic Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1985;26:163–169. [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Ree J M, Schwillens P, van den Bosch J F. Monoclonal antibodies that recognize the P-fimbriae F71, F72, F9, and F11 from uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1985;50:900–904. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.3.900-904.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Ree J M, Schwillens P, van den Bosch J F. Monoclonal antibodies for serotyping the P fimbriae of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:121–125. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.1.121-125.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Ree J M, van den Bosch J F. Serological response to the P fimbriae of uropathogenic Escherichia coli in pyelonephritis. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2204–2207. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2204-2207.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Ree J M, van den Bosch J F. Fimbrial serotypes of Escherichia coli strains isolated from extra-intestinal infections. J Med Microbiol. 1989;29:95–99. doi: 10.1099/00222615-29-2-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dozois C M, Harel J, Fairbrother J M. P-fimbriae-producing septicaemic Escherichia coli from poultry possess fel-related gene clusters whereas pap-hybridizing P-fimbriae-negative strains have partial or divergent P fimbrial gene clusters. Microbiology. 1996;142:2759–2766. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-10-2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emini E A, Hughes J V, Perlow D S, Boger J. Induction of hepatitis A virus-neutralizing antibody by a virus-specific synthetic peptide. J Virol. 1985;55:836–839. doi: 10.1128/jvi.55.3.836-839.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Felsenstein J. Phylogenies from molecular sequences: inference and reliability. Annu Rev Genet. 1988;22:521–565. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.002513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia E, Bergmans H E N, van der Zeijst B A M, Gaastra W. Nucleotide sequences of the major subunits of F9 and F12 fimbriae of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Microb Pathog. 1992;13:161–166. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90076-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garnier J, Osguthorpe D J, Robson B. Analysis of the accuracy and implications of simple methods for predicting the secondary structure of globular proteins. J Mol Biol. 1978;120:97–120. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guyer D M, Kao J-S, Mobley H L T. Genomic analysis of a pathogenicity island in uropathogenic Escherichia coli CFT073: distribution of homologous sequences among isolates from patients with pyelonephritis, cystitis, and catheter-associated bacteriuria and from fecal samples. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4411–4417. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4411-4417.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hacker J, Ott M, Schmidt G, Hull R, Goebel W. Molecular cloning of the F8 fimbrial antigen from Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1986;36:139–144. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins D G, Thompson J D, Gibson T J. Using CLUSTAL for multiple sequence alignments. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:383–402. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hopp T P, Woods K R. Prediction of protein antigenic determinants from amino acid sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:3824–3828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hopp T P, Woods K R. A new computer program for predicting protein antigenic determinants. Mol Immunol. 1988;20:483–489. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(83)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoschützky H, Lottspeich F, Jann K. Isolation and characterization of the α-galactosyl-1,4β-galactosyl-specific adhesin (P adhesin) from fimbriated Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1989;57:76–81. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.1.76-81.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hull R A, Hull S I, Falkow S. Frequency of gene sequences necessary for pyelonephritis-associated pili expression among isolates of Enterobacteriaceae from human extraintestinal infections. Infect Immun. 1984;43:1064–1067. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.3.1064-1067.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hull S, Clegg S, Svanborg Eden C, Hull R. Multiple forms of genes in pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli encoding adhesins binding globoseries glycolipid receptors. Infect Immun. 1985;47:80–83. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.1.80-83.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jameson B A, Wolf H. The antigenic index: a novel algorithm for predicting antigenic determinants. Comput Appl Biosci. 1988;4:181–186. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/4.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson J R. Virulence factors in Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:80–128. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson J R. Host-pathogen interactions in Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 1994;7:287–294. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson J R. papG alleles among Escherichia coli strains causing urosepsis: associations with other bacterial characteristics and host compromise. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4568–4571. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4568-4571.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson J R, Ahmed P, Brown J J. Diversity of hemagglutination phenotypes among P fimbriated wild-type strains of Escherichia coli according to papG repertoire. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:160–170. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.2.160-170.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson J R, Brown J J. A novel multiply-primed polymerase chain reaction assay for identification of variant papG genes encoding the Gal(α1-4)Gal-binding PapG adhesins of Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:920–926. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.4.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson J R, Brown J J. Colonization with and acquisition of uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains as revealed by polymerase chain reaction-based detection. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1120–1124. doi: 10.1086/517409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson J R, Goullet P H, Picard B, Moseley S L, Roberts P L, Stamm W E. Association of carboxylesterase B electrophoretic pattern with presence and expression of urovirulence factor determinants and antimicrobial resistance among strains of Escherichia coli causing urosepsis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2311–2315. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2311-2315.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson J R, Moseley S, Roberts P, Stamm W E. Aerobactin and other virulence factor genes among strains of Escherichia coli causing urosepsis: association with patient characteristics. Infect Immun. 1988;56:405–412. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.2.405-412.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson J R, Orskov I, Orskov F, Goullet P, Picard B, Moseley S L, Roberts P L, Stamm W E. O, K, and H antigens predict virulence factors, carboxylesterase B pattern, antimicrobial resistance, and host compromise among Escherichia coli strains causing urosepsis. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:119–126. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson J R, Roberts P, Stamm W E. P fimbriae and other virulence factors in Escherichia coli urosepsis: association with patient's characteristics. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:225–229. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson J R, Russo T A, Brown J J, Stapleton A. papG alleles of Escherichia coli strains causing first episode or recurrent acute cystitis in adult women. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:97–101. doi: 10.1086/513824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson J R, Russo T A, Scheutz F, Brown J J, Zhang L, Palin K, Rode C, Bloch C, Marrs C F, Foxman B. Discovery of disseminated J96-like strains of uropathogenic Escherichia coli O4:H5 containing genes for both PapGJ96 (“Class I”) and PrsGJ96 (“Class III”) Gal(α1-4)Gal-binding adhesins. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:983–988. doi: 10.1086/514006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson J R, Stapleton A E, Russo T A, Scheutz F, Brown J J, Maslow J N. Characteristics and prevalence within serogroup O4 of a J96-like clonal group of uropathogenic Escherichia coli O4:H5 containing the class I and class III alleles of papG. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2153–2159. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2153-2159.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson J R, Stell A L. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J Infect Dis, 2000;181:261–272. doi: 10.1086/315217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson J R, Swanson J L, Neill M A. Avian P1 antigens inhibit agglutination mediated by P fimbriae of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1992;60:578–583. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.2.578-583.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaack M B, Roberts J A, Baskin G, Patterson G M. Maternal immunization with P fimbriae for the prevention of neonatal pyelonephritis. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.1.1-6.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kanai S, Mikake K, Agata N, Ohta M, Kato N. Antibody response to P-fimbriae of Escherichia coli in patients with genotourinary tract infections. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1990;36:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kao J, Stucker D M, Warren J W, Mobley H L T. Pathogenicity island sequences of pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli CFT073 are associated with virulent uropathogenic strains. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2812–2820. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2812-2820.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karr J F, Nowicki B, Truong L D, Hull R A, Hull S I. Purified P fimbriae from two cloned gene clusters of a single pyelonephritogenic strain adhere to unique structures in the human kidney. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3594–3600. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3594-3600.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Klemm P. Fimbrial adhesins of Escherichia coli. Rev Infect Dis. 1985;7:321–340. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Korhonen T K, Valtonen M V, Parkkinen J, Väisänen-Rhen V, Finne J, Ørskov F, Ørskov I, Svenson S B, Mäkelä P H. Serotypes, hemolysin production, and receptor recognition of Escherichia coli strains associated with neonatal sepsis and meningitis. Infect Immun. 1985;48:486–491. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.2.486-491.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ljungh A, Wadstrom T. Fimbriation of Escherichia coli in urinary tract infections. Comparisons between bacteria in the urine and subcultured bacterial isolates. Curr Microbiol. 1983;8:263–268. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Low D, Robinson E N, Jr, McGee Z A, Falkow S. The frequency of expression of pyelonephritis-associated pili is under regulatory control. Mol Microbiol. 1987;1:335–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1987.tb01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lund B, Lindberg F, Marklund B I, Normark S. The PapG protein is the α-d-galactopyranosyl-(1-4)-β-d-galactopyranose-binding adhesin of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:5898–5902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lund B, Lindberg F, Normark S. Structure and antigenic properties of the tip-located P pilus proteins of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1887–1894. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1887-1894.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mizunoe Y, Nakabeppu Y, Sekiguchi M, Kawabata S-I, Moriya T, Amako K. Cloning and sequence of the gene encoding the major structural component of mannose-resistant fimbriae of Serratia marcescens. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3567–3574. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.8.3567-3574.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mobley H L T, Green D M, Trifillis A L, Johnson D E, Chippendale G R, Lackatell C V, Jones B D, Warren J W. Pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli and killing of cultured human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells: role of hemolysin in some strains. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1281–1289. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.5.1281-1289.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mobley H L T, Jarvis K G, Elwood J P, Whittle D I, Lockatell C V, Russell R G, Johnson D E, Donnenberg M S, Warren J W. Isogenic P-fimbrial deletion mutants of pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli: the role of αGal(1-4)-βGal binding in virulence of a wild-type strain. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:143–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nimich W, Zingler G, Orskov I. Fimbrial antigens of Escherichia coli O1:K1:H7 and O1:K1:H− strains isolated from patients with urinary tract infections. Zentbl Bakteriol Hyg A. 1984;258:104–111. doi: 10.1016/s0176-6724(84)80014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nowicki B, Rhen M, Vaisanen-Rhen V, Pere A, Korhonen T K. Immunofluorescence study of fimbrial phase variation in Escherichia coli KS71. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:691–695. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.2.691-695.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.O'Hanley P. Prospects for urinary tract infection vaccines. In: Mobley H L T, Warren J W, editors. Urinary tract infections: molecular pathogenesis and clinical management. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 405–425. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Old D C, Yakubu D E, Crichton P B. Demonstration by immuno-electronmicroscopy of antigenic heterogeneity among P fimbriae of strains of Escherichia coli. J Med Microbiol. 1987;23:247–253. doi: 10.1099/00222615-23-3-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Olesen B, Kolmos H J, Orskov F, Orskov I. A comparative study of nosocomial and community-acquired strains of Escherichia coli causing bacteraemia in a Danish university hospital. J Hosp Infect. 1995;31:295–305. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(95)90208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Orskov F, Orskov I. Serotyping of Escherichia coli. Methods Microbiol. 1984;14:43–111. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Orskov I, Orskov F. Serology and Escherichia coli fimbriae. Prog Allergy. 1983;33:80–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Orskov I, Orskov F. Serologic classification of fimbriae. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;151:71–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ørskov I, Ørskov F, Birch-Andersen A. Comparison of Escherichia coli fimbrial antigen F7 with type 1 fimbriae. Infect Immun. 1980;27:657–666. doi: 10.1128/iai.27.2.657-666.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Orskov I, Orskov F, Birch-Andersen A, Kanamori M, Svanborg Eden C. O, K, H and fimbrial antigens in Escherichia coli serotypes associated with pyelonephritis and cystitis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1982;33:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pecha B, Low D, O'Hanley P. Gal-Gal pili vaccines prevent pyelonephritis by piliated Escherichia coli in a murine model: single component Gal-Gal pili vaccines prevent pyelonephritis by homologous and heterologous piliated E. coli strains. J Clin Investig. 1989;83:2102–2108. doi: 10.1172/JCI114123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pere A. P fimbriae on uropathogenic Escherichia coli O16:K1 and O18 strains. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1986;37:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pere A, Nowicki B, Saxen H, Siitonen A, Korhonen T K. Expression of P, type 1 and type 1C fimbriae of Escherichia coli in the urine of patients with acute urinary tract infection. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:567–574. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.4.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pere A, Selander R K, Korhonen T K. Characterization of P fimbriae on O1, O7, O75, rough, and nontypable strains of Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1288–1294. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1288-1294.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pere A, Väisänen-Rhen V, Rhen M, Tenhunen J, Korhonen T K. Analysis of P fimbriae on Escherichia coli O2, O4, and O6 strains by immunoprecipitation. Infect Immun. 1986;51:618–625. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.2.618-625.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Plos K, Carter T, Hull S, Hull R, Svanborg Edén C. Frequency and organization of pap homologous DNA in relation to clinical origin of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:518–524. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.3.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Plos K, Hull S I, Hull R A, Levin B R, Ørskov I, Ørskov F, Svanborg-Edén C. Distribution of the P-associated-pilus (pap) region among Escherichia coli from natural sources: evidence for horizontal gene transfer. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1604–1611. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.5.1604-1611.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rhen M, Makela P H, Korhonen T K. P fimbriae of Escherichia coli are subject to phase variation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1983;19:267–271. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Riegman N, Hoschutzky H, van Die I, Hoekstra W, Jann K, Bergmans H. Immunocytochemical analysis of P-fimbrial structure: localization of minor subunits and the influence of the minor subunit FsoE on the biogenesis of the adhesin. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1193–1198. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]