Abstract

Tuberous Sclerosis (TS) is a rare genetic disorder manifesting with multiple benign tumors impacting the function of vital organs. In TS patients, dominant negative mutations in TSC1 or TSC2 increase mTORC1 activity. Increased mTORC1 activity drives tumor formation, but also severely impacts central nervous system function, resulting in infantile seizures, intractable epilepsy, and TS-associated neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism, attention deficits, intellectual disability, and mood disorders. More recently, TS has also been linked with frontotemporal dementia. In addition to TS, accumulating evidence implicates increased mTORC1 activity in the pathology of other neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders. Thus, TS provides a unique disease model to address whether developmental neural circuit abnormalities promote age-related neurodegeneration, while also providing insight into the therapeutic potential of mTORC1 inhibitors for both developing and degenerating neural circuits. In the following review, we explore the ability of both mouse and human brain organoid models to capture TS pathology, elucidate disease mechanisms, and shed light on how neurodevelopmental alterations may later contribute to age-related neurodegeneration.

Keywords: synapse, tau, mTORC, tuberous sclerosis, GABA, neurodevelopment, neurodegeneration

Introduction

Overview of Tuberous Sclerosis

Tuberous Sclerosis (TS) is a rare genetic disorder manifesting with multiple benign tumors impacting the function of vital organs (Curatolo et al., 2015). TS is driven by autosomal dominant negative mutations in either of the Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC) genes, TSC1 or TSC2 (Laplante et al., 2012). A significant portion of patients also exhibit germline and/or somatic mosaicism, resulting in heterogenous expression of TSC1/2 mutations (Verhoef et al., 1999; Giannikou et al., 2019). In most patients, TSC1/2 mutations impact central nervous system function, resulting in infantile seizures, intractable epilepsy, and TS-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND), including autism, attention deficits, intellectual disability, and mood disorders (Shepherd and Stephenson, 1992; de Vries and Watson, 2008; Chu-Shore et al., 2010; Bolton et al., 2015; de Vries et al., 2015; Kingswood et al., 2017; de Vries et al., 2018; Cervi et al., 2020). Recently, significant phenotypic overlap between TS and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) has also been described; this overlap includes TAND-associated cognitive-behavioral alterations, as well as clinical biomarkers, such as phosphorylated tau (Olney et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2020a; Alquezar et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022). These neuropsychiatric manifestations significantly affect quality of life for TS patients and their families, accounting for the majority of disease-associated morbidity, mortality, and burden of care in the TS patient population (Curatolo et al., 2015).

Despite this significant burden, the neuropsychiatric component of TS is the most complex and least understood disease aspect. At a molecular level, TSC1 and TSC2 form a complex that negatively regulates mammalian target of rapamycin complex-1 (mTORC1) -mediated growth pathways (Laplante et al., 2012). Thus, disease-associated mutations result in increased mTORC1 activity and growth, leading to tumor formation (Laplante et al., 2012; Lipton and Sahin, 2014). Not surprisingly, therapeutic approaches have largely focused on mTORC1 inhibitors, such as rapamycin and rapamycin-derivatives. mTORC1 inhibitors, such as the rapamycin derivative everolimus, have demonstrated efficacy in preventing disease-associated tumor growth, including the growth of subependymal giant cell astrocytomas in the brain (Franz et al., 2013; Franz et al., 2015; Lechuga et al., 2019). However, attempts at treating neurocognitive impairment in TS have been mixed (Krueger et al., 2013; Tran et al., 2015; French et al., 2016; Krueger et al., 2017; Overwater et al., 2019). For example, everolimus fails to treat intractable epilepsy in at least 50% of patients (French et al., 2016; Overwater et al., 2019), and there is no clinically observed benefit to TAND (Krueger et al., 2017). This failure of mTORC1 inhibitors suggests tumor-independent mechanisms contribute to neurocognitive impairment. Tumor-independent mechanisms in TS pathology are supported by mouse models, in which pathogenic TSC1 and TSC2 mutations give rise to neuron-autonomous alterations in synapse development (Feliciano et al., 2013/02; Feliciano et al., 2020; Bassetti et al., 2021; Bateup et al., 2013). Understanding how TS-associated synaptic alterations contribute to neurocognitive impairment and increased risk of dementia within the TS patient population (Liu et al., 2020a) will have implications for the larger autism spectrum, where synaptic alterations are a common pathological feature (Penzes et al., 2011; Phillips and Pozzo-Miller, 2014). Emerging evidence also suggests that patients within autism spectrum disorders are at an increased risk of early onset dementia (Vivanti et al., 2021). Thus, it is necessary to understand how synaptic alterations within developing circuits may later contribute to synapse loss, neurodegeneration and cognitive decline in dementia. This review addresses shared pathological features linking synaptic dysfunction across TS patient lifespan with the hope of elucidating mechanisms that drive age-related cognitive loss within the larger autism patient spectrum.

Synapse formation in developing neural circuits

Before we address how synapses are altered in TS, we will first discuss how they typically form during development. Synapses are the points of contact between neurons which facilitate electrochemical communication, giving rise to complex cognitive functions, such as learning, memory, and social behavior (Lynch et al., 2007). In humans, synapse formation begins around mid-fetal gestation (Tau and Peterson, 2010). Synapses can either be inhibitory, suppressing action potential formation, or excitatory, promoting action potential formation. Inhibitory GABAergic synapse formation precedes the formation of excitatory glutamatergic synapses (Ben-Ari, 2002; Ben-Ari, 2006). However, inhibitory synapses initially exhibit GABA-induced excitation (Ben-Ari, 2002; Ben-Ari, 2006). This GABA-elicited depolarization may serve neuroprotective roles in the fetal development of neural circuitry since the excitatory transmitter glutamate can be cytotoxic. However, since GABA is derived from glutamate, this initial GABA-induced excitation may allow GABA to promote neurite and synapse formation, while also preventing glutamate-induced neurotoxicity in vulnerable neural circuits of the developing brain (Ben-Ari, 2002; Ben-Ari, 2006). In immature neural circuits, expression of the sodium-potassium-chloride importer, NKCC1, is high, while expression of the potassium chloride exporter, KCC2, is low (Ben-Ari, 2002; Sernagor et al., 2010; Côme et al., 2019). The ratio of NKCC1 to KCC2 affects the reversal potential of GABA receptors, resulting in Cl− efflux and depolarization when the ratio of NKCC1:KCC2 is high (Liu et al., 2020b). However, KCC2 expression beginning at 18–25 post-conception weeks in subplate and cortical plate neurons enables GABA-induced inhibition through chloride influx and hyperpolarization characteristic of mature circuits (Sedmak et al., 2016).

Corresponding with the developmental shift from GABA-induced excitation to inhibition, excitatory synapses containing pre-synaptic vesicular glutamate transporters and post-synaptic glutamate receptors, begin to form. These excitatory synapses initially form along dendrites or on finger-like dendritic projections, known as filopodia-like spine precursors, but after birth, they are predominantly found on specialized dendritic projections, known as spines (Wilson and Newell-Litwa, 2018). In their mature state, these dendritic spines exhibit a polarized mushroom-shaped structure with a bulbous head atop a thin spine neck (Newell-Litwa et al., 2015). This morphology helps to facilitate action potential propagation. The increased surface area of the head region increases the number of glutamate receptors adjacent to the pre-synaptic axon terminal, thus increasing the likelihood of action potential formation. Furthermore, the physical properties of the thin spine neck alter resistance, with length of the spine neck inversely correlating with action potential formation (Araya et al., 2014; Tønnesen and Nägerl, 2016). Unlike inhibitory synapses which form along the dendritic shaft, the unique morphology of the post-synaptic compartment of excitatory synapses allows them to be readily visualized in post-mortem tissue without the use of immunolabeling, which often requires antigen retrieval in human post-mortem samples. Furthermore, in transmission electron microscopy, the electron-dense post-synaptic density of excitatory synapses is also readily visible (Hahn et al., 2009/04). Because of these attributes, the majority of post-mortem human brain studies of neuropsychiatric disorders have focused on changes to excitatory synapses. In humans, excitatory synapse formation lasts until later juvenile stages (∼5–6years). Throughout adolescence, synaptic pruning refines developing neural circuits, leading to relatively stable synapse densities throughout adulthood, except for cases of age-related cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases when synapse numbers once more decline (Penzes et al., 2011).

Synaptic pathology in TS

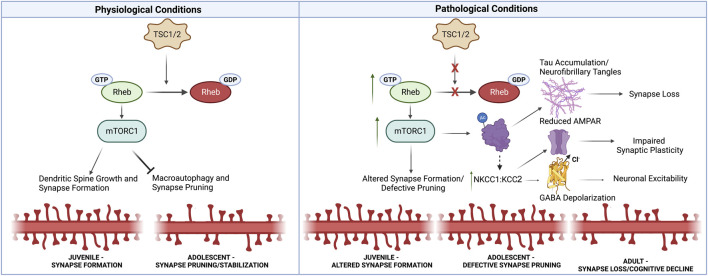

In TS mouse models, synapse formation is initially impaired, but synaptic overgrowth is observed later in development (Tavazoie et al., 2005; Phillips and Pozzo-Miller, 2014; Tang et al., 2014; Yasuda et al., 2014). In TS mice, the initial defect in synapse formation corresponds with immature filopodia-like spine precursors (Tavazoie et al., 2005; Yasuda et al., 2014). However, later in development, increased mTORC1 activity impairs macroautophagy of excitatory synapses, resulting in synaptic overgrowth (Tang et al., 2014). Consistent with these temporal differences in synaptic pathology, mTORC1 inhibition fails to rescue the emergence of TS-associated deficits in synapse formation but restores synaptic pruning later in synapse development (Tavazoie et al., 2005; Phillips and Pozzo-Miller, 2014; Tang et al., 2014; Yasuda et al., 2014). Defective macroautophagy may also contribute to the observed increase in excitatory synapses in the temporal lobe of autism patients aged 13–19 years (Tang et al., 2014). Notably, a similar increase is not observed in autism patients of ages 3–9 years, suggesting that TSC-mediated inhibition of mTORC1 is necessary for synaptic pruning to occur at later adolescent stages (Tang et al., 2014). Intriguingly, one might suspect that this synaptic overgrowth might protect TS individuals from age-related FTD (Olney et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2020a). Similar to other neurodegenerative diseases, FTD exhibits synapse loss within the temporal lobe (Clare et al., 2010). However, if the TS-associated mTORC1 hyperactivation prevents synaptic pruning, what are the mechanisms that drive synapse loss and cognitive decline of TS patients later in life? Here, we will explore two potential hypotheses by which developmental TS synaptic pathology later disrupts neural circuits, resulting in their eventual degradation (Figure 1). In the following section, we will first address the mechanisms by which developmental synaptic pathology may contribute to later neurodegeneration and then examine potential therapeutic strategies.

FIGURE 1.

Synaptic Alterations Linking Neurodevelopmental and Neurodegenerative Pathology in TS. Under physiological conditions, TSC1/2 inhibit mTORC1 activity through Rheb-GTPase. mTORC1 promotes synapse formation, but prevents macroautophagy-mediated synaptic pruning later in development. Thus under pathological conditions in TS, mTORC1 activity is increased, resulting in defective synaptic pruning in adolescence. Increased mTORC1 also promotes tau aggregation through acetylation and phosphorylation. Furthermore, impaired autophagy prevents the clearance of tau aggregates, ultimately driving synapse loss. Additionally, TS patients exhibit alterations in NKCC1:KCC2 that resemble immature neural circuits. These changes may in part be driven by tau accumulation. Increased NKCC1:KCC2 can alter GABA polarization at inhibitory synapses, but also impairs AMPAR recruitment at excitatory synapses which is necessary for synaptic plasticity associated with learning and memory. Thus, early developmental synaptic alterations likely lead to the accumulation of neurotoxic tau aggregates, impair synaptic plasticity necessary for learning and memory, and alter neuronal excitability, thus driving synapse loss in neurodegenerative disorders. Created with Biorender.com.

Potential synaptic mechanisms linking neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative pathology

Altered NKCC1:KCC2 in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders

As previously mentioned, the ratio of NKCC1 to KCC2 underlies GABA-mediated currents, with developing neural circuits exhibiting higher NKCC1:KCC2 ratios resulting in GABA-induced depolarization and excitation. Intriguingly, TS patients exhibit increased expression of NKCC1 and decreased expression of KCC2, perpetuating GABA-induced excitation as observed in the immature developing brain (Talos et al., 2012; Ruffolo et al., 2016). A human neuronal model of TS recapitulates elevated SLC12A2 (NKCC1) and decreased SLC12A5 (KCC2) expression (Costa et al., 2016). The elevated NKCC1:KCC2 ratio may in part be a compensatory mechanism in response to TS-elevated mTORC1 since NKCC1 suppresses mTORC1 activity (Demian et al., 2019). Similar NKCC1:KCC2 alterations are observed in other neurodevelopmental disorders, such as Rett Syndrome (Tang et al., 2016). Neurodegenerative diseases, such as Huntington’s Disease (HD) and possibly Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), exhibit alterations in NKCC1 and KCC2 expression that resemble immature neural circuits (Tang, 2020; Dargaei et al., 2018; Yin et al., 2019/01; Lam et al., 2022; Virtanen et al., 2021). Furthermore, in a human induced pluripotent model of tauopathies, introducing common FTDP-17 mutations (FTD with parkinsonism linked with chromosome 17) reduced KCC2 expression in differentiated neurons (García-León et al., 2018), further suggesting that reduced KCC2 is a driver of neurodegenerative disease pathology, particularly in tauopathies, such as AD and FTD.

Altered NKCC1:KCC2 expression can impact both synaptic formation and function, potentially contributing to disease-associated hyperexcitability and synapse loss. Acute pharmacological reductions in KCC2 are sufficient to drive hyperexcitability and epileptiform activity through depolarizing GABA currents (Sivakumaran et al., 2015). However, KCC2 also functions independent of GABA at excitatory glutamatergic synapses, where KCC2 is necessary for both dendritic spine maturation and clustering of AMPA receptors (Li et al., 2007; Gauvain et al., 2011). At the dendritic spines of excitatory synapses, reduced KCC2 expression results in immature filopodia-like protrusions and impairs glutamatergic synapse formation (Li et al., 2007), similar to synaptic impairment initially observed in TS (Yasuda et al., 2014). Later in development, TS synapse density increases due to mTORC1-mediated inhibition of autophagy (Tang et al., 2014). However, consistent with KCC2-mediated trafficking of AMPARs, Tsc1 knockout hippocampal neurons have reduced expression of AMPAR subunits, GluA1/R2 and GluA2/R2 (Bateup et al., 2013). GluA1/2 are specifically added to synapses during periods of plasticity that underlie learning and memory (Shi et al., 2001).

How might early alterations in NKCC1:KCC2 contribute to synaptic alterations in neurodegenerative disorders? Due to the NKCC1:KCC2 regulation of synapse formation and function, GABA-mediated depolarization could contribute to the observed increase in neuronal excitability in neurodegenerative disorders, including FTD (Wishart et al., 2006; Clare et al., 2010; Beagle et al., 2015; Cepeda et al., 2019; Subramanian et al., 2020; Targa Dias Anastacio et al., 2022). Furthermore, GluA1 subunit expression is decreased in neurodegenerative disorders, including AD and FTD, consistent with learning and memory deficits in these disorders (Benussi et al., 2019; Qu et al., 2021). Thus developmental disruptions in synaptic plasticity and activity could predispose individuals to early-onset dementia. Further studies are needed to identify synapse-specific proteomic changes in TS and corresponding synaptic changes in FTD. Identification of synaptic alterations shared between TS and FTD could be used for therapeutic intervention in early development, thus preventing synaptic alterations that likely contribute to later age-related cognitive decline.

Restoring KCC2 expression in TS patients may be complicated as mTORC1 inhibition does not restore the developmental shift in GABA-induced activity; rather, rapamycin treatment decreased KCC2 expression, increasing seizure susceptibility in a juvenile, but not adult, rat model (Huang et al., 2012). Thus, while the rapamycin derivative everolimus reduces patient tumor burden, decreased KCC2 expression could contribute to the persistence of epileptic seizures in ∼50% of treated patients (French et al., 2016; Overwater et al., 2019). Notably, however, these studies were conducted in a chemically-induced seizure model and not in a TS model, where mTORC1 is elevated. Thus, further studies of the effect of mTORC1 inhibition on KCC2 and epilepsy in TS are needed. Nonetheless, the development of KCC2-enhancing drugs may hold promise for restoring GABA-induced inhibition and AMPAR-mediated synaptic plasticity in affected neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders (Tang et al., 2019; Tang, 2020).

mTORC1-driven tau post-translational modifications drive pathological accumulation

Since tauopathies, such as AD and FTD, exhibit synapse loss and hyperexcitability, we will next explore how tau pathology may contribute to both neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative diseases. Pathogenic tau impairs synaptic transmission by binding to the synaptic vesicle protein, synaptogyrin-3, ultimately resulting in the loss of excitatory glutamatergic synapses (Largo-Barrientos et al., 2021). Notably, TS is a tauopathy that exhibits similar pathology to FTD brains, which do not contain amyloid plaques (Liu et al., 2022). Thus, TS is a good model to assess the role of tau aggregation independent of amyloid plaques. Accumulating evidence also suggests that tau aggregation plays an underappreciated role in other neurodevelopmental disorders (Rankovic and Zweckstetter, 2019). Intriguingly, TSC1 haploinsufficiency increases tau acetylation and accumulation (Alquezar et al., 2021). This is likely through increased mTORC1 activity since mTORC1 directly activates p300 acetyltransferase, which is responsible for tau acetylation (Wan et al., 2017; Alquezar et al., 2021). In addition to acetylation, mTORC1 also regulates tau aggregation through phosphorylation (Caccamo et al., 2013). Since elevated mTORC1 in TS prevents autophagy-mediated clearance of pathogenic tau aggregates (Alquezar et al., 2021), early post-translational tau modifications may progressively lead to the accumulation of tau aggregates and early-onset dementia and neurodegeneration, especially since hyperphosphorylated tau promotes the self-assembly of tau neurofibrillary tangles (Iqbal et al., 2010). Thus, increased tau phosphorylation and acetylation leading to accumulation are likely early biomarkers of neurodevelopmental disorders that contribute to the increased patient susceptibility to neurodegenerative disorders. As previously noted, increased excitability in tauopathies may be driven in part by decreased KCC2 expression as introduction of FTD-associated tau mutations decrease KCC2 levels in a human neuronal model (García-León et al., 2018). Furthermore, loss of tau reduces network hyperexcitability in AD and seizure models (Holth et al., 2013). However, this rescue is likely driven by multiple factors since tau loss reduces hyperexcitability in the absence of KCC2 function (Holth et al., 2013). Finally, rapamycin reduces tau aggregate burden in mice and human neurons by activating autophagy (Ozcelik et al., 2013; Silva et al., 2020). Additionally, this reduction in tau burden reduces astrogliosis (Ozcelik et al., 2013), which is associated with neuroinflammation (Fleeman and Proctor, 2021), although tau was recently shown to drive synapse loss through pre-synaptic vesicle association independent of neuroinflammation (Largo-Barrientos et al., 2021). Intriguingly, preventing association of tau with the synaptic vesicle protein, synaptogyrin-3, restores synaptic plasticity and could potentially serve as an additional therapeutic strategy for reducing tau neurotoxicity (Largo-Barrientos et al., 2021).

Concluding remarks

Accumulating evidence suggests that neurodevelopmental disorders, such as TS, place the affected individual at an increased susceptibility to neurodegeneration. In the present piece, we explored potential synaptic mechanisms driving this association (Figure 1). We first examined how persistent alterations in potassium chloride channels may alter neuronal excitability and synaptic plasticity in developing and degenerating networks. Next, we discussed how early mTORC1-driven post-translational modifications to tau promote accumulation and pathological aggregation leading to synapse loss. The accumulated evidence links early impairment in synaptic plasticity with later synapse loss in neurodegeneration, while also highlighting the need for future studies to identify developmental synaptic alterations that drive age-related synapse loss and neurodegeneration. Insights from future studies of TS and FTD will likely have ramifications for other neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders, where increased mTORC1 signaling is observed (Negraes et al., 2021).

Author contributions

The author conceived of the topic, researched, and wrote this manuscript. The author approves of its publication.

Funding

This work was supported by the NIH under award number R21AT011371 and the NSF under award number 2144912 to KL.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Alquezar C., Schoch K. M., Geier E. G., Ramos E. M., Scrivo A., Li K. H., et al. (2021b). TSC1 loss increases risk for tauopathy by inducing tau acetylation and preventing tau clearance via chaperone-mediated autophagy. Sci. Adv. 7 (45), eabg3897. 10.1126/sciadv.abg3897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araya R., Vogels T. P., Yuste R. (2014). Activity-dependent dendritic spine neck changes are correlated with synaptic strength. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111 (28), E2895–E2904. LP-E2904. 10.1073/pnas.1321869111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassetti D., Luhmann H. J., Kirischuk S. (2021). Effects of mutations in TSC genes on neurodevelopment and synaptic transmission. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (14), 7273. 10.3390/ijms22147273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateup H. S., Johnson C. A., Denefrio C. L., Saulnier J. L., Kornacker K., Sabatini B. L. (2013). Excitatory/inhibitory synaptic imbalance leads to hippocampal hyperexcitability in mouse models of tuberous sclerosis. Neuron 78 (3), 510–522. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beagle A., Darwish S., Karageorgiou E., Vossel K. (2015). Seizures and myoclonus in the early stages of frontotemporal dementia. ). Neurology P1.218 84 [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y. (2006). Basic developmental rules and their implications for epilepsy in the immature brain. Epileptic Disord. 8 (2), 91–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y. (2002). Excitatory actions of gaba during development: The nature of the nurture. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3(9):728–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benussi A., Alberici A., Buratti E., Ghidoni R., Gardoni F., Di Luca M., et al. (2019). Toward a glutamate hypothesis of frontotemporal dementia. Front. Neurosci. 13, 304. 10.3389/fnins.2019.00304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P. F., Clifford M., Tye C., Maclean C., Humphrey A., le Maréchal K., et al. (2015). Intellectual abilities in tuberous sclerosis complex: Risk factors and correlates from the tuberous sclerosis 2000 study. Psychol. Med. 45 (11), 2321–2331. 10.1017/S0033291715000264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caccamo A., Magrì A., Medina D. X., Wisely E. V., López-Aranda M. F., Silva A. J., et al. (2013). mTOR regulates tau phosphorylation and degradation: implications for Alzheimer’s disease and other tauopathies. Aging Cell 12 (3), 370–380. 10.1111/acel.12057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda C., Oikonomou K. D., Cummings D., Barry J., Yazon V-W., Chen D. T., et al. (2019). Developmental origins of cortical hyperexcitability in Huntington’s disease: Review and new observations. J. Neurosci. Res. 97 (12), 1624–1635. 10.1002/jnr.24503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervi F., Saletti V., Turner K., Peron A., Bulgheroni S., Taddei M., et al. (2020). The TAND checklist: A useful screening tool in children with tuberous sclerosis and neurofibromatosis type 1. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 15 (1), 237. 10.1186/s13023-020-01488-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu-Shore C. J., Major P., Camposano S., Muzykewicz D., Thiele E. A. (2010). The natural history of epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsia 51 (7), 1236–1241. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02474.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare R., King V. G., Wirenfeldt M., Vinters H. V. (2010). Synapse loss in dementias. J. Neurosci. Res. 88 (10), 2083–2090. 10.1002/jnr.22392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côme E., Heubl M., Schwartz E. J., Poncer J. C., Lévi S. (2019). Reciprocal regulation of KCC2 trafficking and synaptic activity. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 13, 48. 10.3389/fncel.2019.00048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa V., Aigner S., Vukcevic M., Sauter E., Behr K., Ebeling M., et al. (2016). mTORC1 inhibition corrects neurodevelopmental and synaptic alterations in a human stem cell model of tuberous sclerosis. Cell Rep. 15 (1), 86–95. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curatolo P., Moavero R., de Vries P. J. Neurological and neuropsychiatric aspects of tuberous sclerosis complex. Lancet. Neurol. 2015. Jul;14(7):733–745. 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00069-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dargaei Z., Bang J. Y., Mahadevan V., Khademullah C. S., Bedard S., Parfitt G. M., et al. (2018). Restoring GABAergic inhibition rescues memory deficits in a Huntington's disease mouse model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115 (7), E1618-E1626–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries P. J., Watson P. (2008). Attention deficits in tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC): Rethinking the pathways to the endstate. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 52 (Pt 4), 348–357. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.01030.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries P. J., Whittemore V. H., Leclezio L., Byars A. W., Dunn D., Ess K. C., et al. (2015). Tuberous sclerosis associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) and the TAND Checklist. Pediatr. Neurol. 52 (1), 25–35. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries P. J., Wilde L., de Vries M. C., Moavero R., Pearson D. A., Curatolo P. (2018). A clinical update on tuberous sclerosis complex-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND). Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 178 (3), 309–320. 10.1002/ajmg.c.31637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demian W. L., Persaud A., Jiang C., É Coyaud, Liu S., Kapus A., et al. (2019). The ion transporter NKCC1 links cell volume to cell mass regulation by suppressing mTORC1. Cell Rep. 27 (6), 1886–1896. e6. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano D. M., Lin T. V., Hartman N. W., Bartley C. M., Kubera C., Hsieh L., et al. (2013/02/26201). A circuitry and biochemical basis for tuberous sclerosis symptoms: From epilepsy to neurocognitive deficits. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 31 (7), 667–678. 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2013.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano D. M. (2020). The neurodevelopmental pathogenesis of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) Front. Neuroanat., 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleeman R. M., Proctor E. A. (2021).Astrocytic propagation of tau in the context of Alzheimer’s disease Front. Cell. Neurosci., 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz D. N., Agricola K., Mays M., Tudor C., Care M. M., Holland-Bouley K., et al. (2015). Everolimus for subependymal giant cell astrocytoma: 5-year final analysis. Ann. Neurol. 78 (6), 929–938. 10.1002/ana.24523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz D. N., Belousova E., Sparagana S., Bebin E. M., Frost M., Kuperman R., et al. (2013). Efficacy and safety of everolimus for subependymal giant cell astrocytomas associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (EXIST-1): A multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, Engl. 381 (9861), 125–132. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61134-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French J. A., Lawson J. A., Yapici Z., Ikeda H., Polster T., Nabbout R., et al. (2016). Adjunctive everolimus therapy for treatment-resistant focal-onset seizures associated with tuberous sclerosis (EXIST-3): A phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet (London, Engl. 388 (10056), 2153–2163. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31419-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-León J. A., Cabrera-Socorro A., Eggermont K., Swijsen A., Terryn J., Fazal R., et al. (2018). Generation of a human induced pluripotent stem cell–based model for tauopathies combining three microtubule-associated protein TAU mutations which displays several phenotypes linked to neurodegeneration. Alzheimer’s Dement. 14(10):1261–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauvain G., Chamma I., Chevy Q., Cabezas C., Irinopoulou T., Bodrug N., et al. (2011). The neuronal K-Cl cotransporter KCC2 influences postsynaptic AMPA receptor content and lateral diffusion in dendritic spines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108 (37), 15474–15479. 10.1073/pnas.1107893108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannikou K., Lasseter K. D., Grevelink J. M., Tyburczy M. E., Dies K. A., Zhu Z., et al. (2019). Low-level mosaicism in tuberous sclerosis complex: Prevalence, clinical features, and risk of disease transmission. Genet. Med. 21 (11), 2639–2643. 10.1038/s41436-019-0562-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn C-G., Banerjee A., Macdonald M. L., Cho D-S., Kamins J., Nie Z., et al. (2009/04/16200). The post-synaptic density of human postmortem brain tissues: An experimental study paradigm for neuropsychiatric illnesses. PLoS One 4 (4), e5251. 10.1371/journal.pone.0005251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holth J. K., Bomben V. C., Reed J. G., Inoue T., Younkin L., Younkin S. G., et al. (2013). Tau loss attenuates neuronal network hyperexcitability in mouse and Drosophila genetic models of epilepsy. J. Neurosci. 33 (4), 1651–1659. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3191-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., McMahon J., Yang J., Shin D., Huang Y. (2012). Rapamycin down-regulates KCC2 expression and increases seizure susceptibility to convulsants in immature rats, Neuroscience 219, 33–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal K., Liu F., Gong C-X., Grundke-Iqbal I. (2010). Tau in Alzheimer disease and related tauopathies. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 7 (8), 656–664. 10.2174/156720510793611592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingswood J. C., d’Augères G. B., Belousova E., Ferreira J. C., Carter T., Castellana R., et al. (2017). TuberOus SClerosis registry to increase disease Awareness (TOSCA) – baseline data on 2093 patients. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 12 (1), 2. 10.1186/s13023-016-0553-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger D. A., Sadhwani A., Byars A. W., de Vries P. J., Franz D. N., Whittemore V. H., et al. (2017). Everolimus for treatment of tuberous sclerosis complex-associated neuropsychiatric disorders. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 4 (12), 877–887. 10.1002/acn3.494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger D. A., Wilfong A. A., Holland-Bouley K., Anderson A. E., Agricola K., Tudor C., et al. (2013). Everolimus treatment of refractory epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. Ann. Neurol. 74 (5), 679–687. 10.1002/ana.23960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam P., Vinnakota C., Guzmán B. C-F., Newland J., Peppercorn K., Tate W. P., et al. (2022). Beta-amyloid (Aβ(1-42)) increases the expression of NKCC1 in the mouse Hippocampus. Molecules 27 (8), 2440. 10.3390/molecules27082440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante M., Sabatini D. M. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012. Apr;149(2):274–293. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Largo-Barrientos P., Apóstolo N., Creemers E., Callaerts-Vegh Z., Swerts J., Davies C., et al. (2021). Lowering Synaptogyrin-3 expression rescues Tau-induced memory defects and synaptic loss in the presence of microglial activation. Neuron 109 (5), 767–777.e5. e5. 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechuga L., Franz D. N. (2019). Everolimus as adjunctive therapy for tuberous sclerosis complex-associated partial-onset seizures. Expert Rev. Neurother. 19 (10), 913–925. 10.1080/14737175.2019.1635457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Khirug S., Cai C., Ludwig A., Blaesse P., Kolikova J., et al. (2007). KCC2 interacts with the dendritic cytoskeleton to promote spine development. Neuron 56 (6), 1019–1033. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton J. O., Sahin M. (2014). The neurology of mTOR. Neuron 84 (2), 275–291. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A. J., Lusk J. B., Ervin J., Burke J., O’Brien R., Wang S-H. J. (2022). Tuberous sclerosis complex is a novel, amyloid-independent tauopathy associated with elevated phosphorylated 3R/4R tau aggregation. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 10 (1), 27. 10.1186/s40478-022-01330-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A. J., Staffaroni A. M., Rojas-Martinez J. C., Olney N. T., Alquezar-Burillo C., Ljubenkov P. A., et al. (2020a). Association of cognitive and behavioral features between adults with tuberous sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. JAMA Neurol. 77 (3), 358–366. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R., Wang J., Liang S., Zhang G., Yang X. (2020b). Role of NKCC1 and KCC2 in epilepsy: From expression to function [internet] Front. Neurology, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch G., Rex C. S., Gall C. M. (2007). LTP consolidation: Substrates, explanatory power, and functional significance. Neuropharmacol. 52(1):12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murmu R. P., Li W., Szepesi Z., Li J. Y. Altered sensory experience exacerbates stable dendritic spine and synapse loss in a mouse model of huntington's disease. J. Neurosci. . 2015. 35(1):287 LP – 298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negraes P. D., Trujillo C. A., Yu N-K., Wu W., Yao H., Liang N., et al. (2021). Altered network and rescue of human neurons derived from individuals with early-onset genetic epilepsy. Mol. Psychiatry 26 (11), 7047–7068. 10.1038/s41380-021-01104-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell-Litwa K. A. K. A., Badoual M., Asmussen H., Patel H., Whitmore L., Horwitz A. R. A. R. (2015). ROCK1 and 2 differentially regulate actomyosin organization to drive cell and synaptic polarity. J. Cell Biol. 210 (2), 225–242. 10.1083/jcb.201504046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney N. T., Alquezar C., Ramos E. M., Nana A. L., Fong J. C., Karydas A. M., et al. (2017). Linking tuberous sclerosis complex, excessive mTOR signaling, and age-related neurodegeneration: A new association between TSC1 mutation and frontotemporal dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 134, 813–816. 10.1007/s00401-017-1764-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overwater I. E., Rietman A. B., van Eeghen A. M., de Wit M. C. Y. (2019). Everolimus for the treatment of refractory seizures associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC): Current perspectives. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 15, 951–955. 10.2147/TCRM.S145630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozcelik S., Fraser G., Castets P., Schaeffer V., Skachokova Z., Breu K., et al. (2013). Rapamycin attenuates the progression of tau pathology in P301S tau transgenic mice. PLoS One 8 (5), e62459. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzes P., Cahill M. E., Jones K. A., VanLeeuwen J-E., Woolfrey K. M. (2011). Dendritic spine pathology in neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 14 (3), 285–293. 10.1038/nn.2741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips M., Pozzo-Miller L. (2014). Neuroscience letters,Dendritic spine dysgenesis autism Relat. Disord. 601. Elsevier Ireland Ltd, 30–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu W., Yuan B., Liu J., Liu Q., Zhang X., Cui R., et al. (2021). Emerging role of AMPA receptor subunit GluA1 in synaptic plasticity: Implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Prolif. 54 (1), e12959. 10.1111/cpr.12959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankovic M., Zweckstetter M. (2019). Upregulated levels and pathological aggregation of abnormally phosphorylated Tau-protein in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 98, 1–9. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffolo G., Iyer A., Cifelli P., Roseti C., Mühlebner A., van Scheppingen J., et al. (2016). Functional aspects of early brain development are preserved in tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) epileptogenic lesions, Neurobiol. Dis. 95, 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedmak G., Jovanov-Milošević N., Puskarjov M., Ulamec M., Krušlin B., Kaila K., et al. (2016). Developmental expression patterns of KCC2 and functionally associated molecules in the human brain. Cereb. Cortex 26 (12), 4574–4589. [Internet]Available from:. 10.1093/cercor/bhv218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sernagor E., Chabrol F., Bony G., Cancedda L. (2010).GABAergic control of neurite outgrowth and remodeling during development and adult neurogenesis: General rules and differences in diverse systems [internet] Front. Cell. Neurosci., 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd C. W., Stephenson J. B. P. (1992). Seizures and intellectual disability associated with tuberous sclerosis complex in the west of scotland. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 34 (9), 766–774. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1992.tb11515.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S-H., Hayashi Y., Esteban J. A., Malinow R. (2001). Subunit-specific rules governing AMPA receptor trafficking to synapses in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Cell 105 (3), 331–343. Cell 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00321-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva M. C., Nandi G. A., Tentarelli S., Gurrell I. K., Jamier T., Lucente D., et al. (2020). Prolonged tau clearance and stress vulnerability rescue by pharmacological activation of autophagy in tauopathy neurons. Nat. Commun. 11 (1), 3258. 10.1038/s41467-020-16984-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumaran S., Cardarelli R. A., Maguire J., Kelley M. R., Silayeva L., Morrow D. H., et al. (2015). Selective inhibition of KCC2 leads to hyperexcitability and epileptiform discharges in hippocampal slices and in vivo . J. Neurosci. 35(21):8291–8296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian J., Savage J. C., Tremblay M-È. (2020). Synaptic loss in alzheimer's disease: Mechanistic insights provided by two-photon in vivo imaging of transgenic mouse models. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 14, 445. 10.3389/fncel.2020.592607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talos D. M., Sun H., Kosaras B., Joseph A., Folkerth R. D., Poduri A., et al. (2012). Altered inhibition in tuberous sclerosis and type IIb cortical dysplasia. Ann. Neurol. 71 (4), 539–551. 10.1002/ana.22696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang B. L. (2020). The expanding therapeutic potential of neuronal KCC2. Cells 9 (1), E240. 10.3390/cells9010240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang G., Gudsnuk K., Kuo S-H., Cotrina M. L., Rosoklija G., Sosunov A., et al. (2014). Loss of mTOR-dependent macroautophagy causes autistic-like synaptic pruning deficits. Neuron [Internet] .[cited 2017 May 5];83(5):1131–1143. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X., Drotar J., Li K., Clairmont C. D., Brumm A. S., Sullins A. J., et al. (2019). Pharmacological enhancement of KCC2 gene expression exerts therapeutic effects on human Rett syndrome neurons and Mecp2 mutant mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 11 (503), eaau0164. eaau0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X., Kim J., Zhou L., Wengert E., Zhang L., Wu Z., et al. (2016). KCC2 rescues functional deficits in human neurons derived from patients with Rett syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113(3):751–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targa Dias Anastacio H., Matosin N., Ooi L. (2022). Neuronal hyperexcitability in Alzheimer’s disease: What are the drivers behind this aberrant phenotype? Transl. Psychiatry 12 (1), 257. 10.1038/s41398-022-02024-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tau G. Z., Peterson B. S. (2010). Normal development of brain circuits. Neuropsychopharmacol. 35(1):147–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavazoie S. F., Alvarez V. A., Ridenour D. A., Kwiatkowski D. J., Sabatini B. L. (2005). Regulation of neuronal morphology and function by the tumor suppressors Tsc1 and Tsc2. Nat. Neurosci. 8 (12), 1727–1734. 10.1038/nn1566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tønnesen J., Nägerl U. V. (2016). Dendritic spines as tunable regulators of synaptic signals. Front. Psychiatry 7, 101. [Internet]Available from:. 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran L. H., Zupanc M. L. (2015). Long-term everolimus treatment in individuals with tuberous sclerosis complex: A review of the current literature. Pediatr. Neurol. 53 (1), 23–30. Pediatr Neurol [Internet]Available from:. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef S., Bakker L., Tempelaars A. M., Hesseling-Janssen A. L., Mazurczak T., Jozwiak S., et al. (1999). High rate of mosaicism in tuberous sclerosis complex. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 64 (6), 1632–1637. 10.1086/302412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen M. A., Uvarov P., Mavrovic M., Poncer J. C., Kaila K. (2021). The multifaceted roles of KCC2 in cortical development. Trends Neurosci. 44 (5), 378–392. Available from:. 10.1016/j.tins.2021.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivanti G., Tao S., Lyall K., Robins D. L., Shea L. L. (2021). The prevalence and incidence of early-onset dementia among adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 14 (10), 2189–2199. 10.1002/aur.2590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan W., You Z., Xu Y., Zhou L., Guan Z., Peng C., et al. (2017). mTORC1 phosphorylates acetyltransferase p300 to regulate autophagy and lipogenesis. Mol. Cell 68 (2), 323–335. e6. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson E. S., Newell-Litwa K. (2018). “Stem cell models of human synapse development and degeneration,” Mol. Biol. Cell [Internet. Editor M Bronner, 29, 2913–2921. Available from: .24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart T. M., Parson S. H., Gillingwater T. H. Synaptic vulnerability in neurodegenerative disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 65, 733–739. 2006. 10.1097/01.jnen.0000228202.35163.c4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda S., Sugiura H., Katsurabayashi S., Shimada T., Tanaka H., Takasaki K., et al. (2014). Activation of Rheb, but not of mTORC1, impairs spine synapse morphogenesis in tuberous sclerosis complex. Sci. Rep. 4, 5155. Sci Rep [Internet]Available from:. 10.1038/srep05155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin C., Ackermann S., Ma Z., Mohanta S. K., Zhang C., Li Y., et al. (2019/01/28201). ApoE attenuates unresolvable inflammation by complex formation with activated C1q. Nat. Med. 25 (3), 496–506. [Internet]Available from:. 10.1038/s41591-018-0336-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]