Abstract

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prevention after major gynecological cancer surgery might be an alternative to parenteral low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). Patients undergoing major gynecological cancer surgery were randomized at hospital discharge to receive rivaroxaban 10 mg once daily or enoxaparin 40 mg once daily for 30 days. The primary efficacy outcome was a combination of symptomatic VTE and VTE-related death or asymptomatic VTE at day 30. The primary safety outcome was the incidence of major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding. Two hundred and twenty-eight patients were enrolled and randomly assigned to receive rivaroxaban (n = 114)or enoxaparin (n = 114). The trial was stopped due to a lower-than-expected event rate. The primary efficacy outcome occurred in 3.51% of patients assigned to rivaroxaban and in 4.39% of patients assigned to enoxaparin (relative risk 0.80, 95% CI 0.22 to 2.90; p = 0.7344). Patients assigned to rivaroxaban had no primary bleeding event, and 3 patients (2.63%) in the enoxaparin group had a major or CRNM bleeding event (hazard ratio, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.007 to 2.73; P = 0.1963). In patients undergoing major gynecological cancer surgery, thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban 10 mg daily for 30 days had similar rates of thrombotic and bleeding events compared to parenteral enoxaparin 40 mg daily. While the power is limited due to not reaching the intended sample size, our results support the hypothesis that DOACs might be an attractive alternative strategy to LMWH to prevent VTE in this high-risk population.

Keywords: rivaroxaban, enoxaparin, venous thromboembolism, gynecology and obstetrics, cancer

Introduction

Cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT) is the second leading cause of mortality in patients with malignancy, mainly due to the most common complication, venous thromboembolism (VTE).1 Several risk factors for VTE development also coexist with cancer patients, such as chemotherapy and immobilization, contributing to the increased risk that cancer patients have of developing VTE compared to patients without cancer.2

There is an association between the type of cancer and the occurrence of VTE. Data from the Cancer-VTE Registry revealed a VTE incidence of 14/1000 people per year (95% CI 13 to 14) for all cancers. The incidence of VTE is the highest for pancreatic cancer in 98/1000 people per year (95% CI 80 to 119), followed by lung, gastric, ovarian, uterine, and breast cancer.3

A meta-analysis looking at data from 6324 patients with ovarian cancer determined a VTE incidence rate of 12.6%.4 The highest incidence rates are related to tumors with more extended staging, which may mean a profile of greater aggressiveness than when compared to tumors in the early stages. The overall incidence of VTE after major gynecological cancer surgery ranges from 5% to 25%.5

Heparin, low-molecular-weight-heparin (LMWH), and vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) were considered the cornerstones of the prevention and treatment of VTE. This trend changed with the introduction of direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC), which are now replacing LMWH for primary thromboprophylaxis after elective hip or knee arthroplasty and VKAs for the treatment of VTE.6

The American Society of Oncology (ASCO) and the American College for Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommend extended pharmacological postsurgical thromboprophylaxis (4 weeks) for patients undergoing major abdominal or pelvic cancer surgery following the use of preoperative heparin and compression therapy.7,8 The agents currently recommended for VTE thromboprophylaxis in patients undergoing abdominal or pelvic cancer surgery are LMWHs.9

Rivaroxaban is an oral direct oral inhibitor of activated factor X (FXa) already approved for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valve atrial fibrillation to reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events in patients with chronic coronary artery disease (CAD) or peripheral artery disease (PAD), for the treatment of acute VTE, long-term prevention of recurrent VTE and prevention of VTE after total knee or hip arthroplasty.10

The only on-label indication for surgical VTE prophylaxis with rivaroxaban is after elective hip or knee arthroplasty. However, several studies have shown efficacy and safety in thromboprophylaxis of other non-orthopedic surgeries.11 Recently, apixaban - another DOAC - was compared to subcutaneous enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in women undergoing surgery for suspected gynecological cancer in a controlled and randomized multi-institutional study, looking for safety as the primary outcome. Apixaban was a safe alternative to LMWH for thromboprophylaxis after gynecological cancer surgery and hypothesized its noninferiority for efficacy compared to the LMWH.12

Given its oral availability, ease to use, and possible higher adherence, this study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of oral rivaroxaban compared to standard of care parenteral LMWH for extended VTE prevention after major gynecological cancer surgery.

Methods

Study Design

The VALERIA trial (Venous thromboembolism prophylAxis after gynecoLogical pElvic cancer surgery with RIvaroxaban vs enoxAparin) was a pragmatic, open-label (with blinded adjudication), single-center, randomized, active-controlled trial in patients undergoing major gynecological cancer surgery. The study was conducted at the São Paulo State Public Women's Health Reference Center, São Paulo, Brazil. Enrollment began in October 2020 and ended in March 2022. The objective was to assess whether rivaroxaban 10 mg once daily for 30 days initiated at hospital discharge would be noninferior to parenteral enoxaparin for 30 days postoperative for the efficacy outcome, a combination of symptomatic and asymptomatic VTE, including VTE-related death).

The study was led by an academic steering committee whose members designed the trial and coordinated the scientific and medical aspects of the study. Science Valley Research Institute (São Paulo, Brazil) was responsible for data and site management and all statistical analysis. All clinical events were evaluated by an independent clinical events adjudication committee, whose members were blinded to the study treatment assignment. The study also had an independent data safety monitoring board for safety surveillance during the trial. The steering committee analyzed the data and all authors had full access to primary clinical trial data.

The ethics committee approved the trial protocol. Following local regulations, all participants provided informed consent (IC). The VALERIA trial institutional review board (IRB) (CAAE 35668820.8.1001.0069) and IRB approvals (4.238.164 and 5.196.881). The protocol is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04999176).

Participants

Patients were considered eligible if they were ≥ 18 years old, have undergone major gynecological cancer surgery (staging surgery, debulking surgery, total or radical hysterectomy, unilateral or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, lymph node removal, open or laparoscopic access), have received LMWH thromboprophylaxis during hospitalization and have signed the IC. The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion Criteria |

| Female patients 18 years of age or older |

| Have undergone major gynecological cancer surgery (staging surgery, debulking surgery, total or radical hysterectomy, unilateral or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, lymph node removal, open or laparoscopic access) |

| Have signed informed consent |

| Have received thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin, fondaparinux, or unfractionated heparin during the index hospitalization |

| Exclusion Criteria |

| Age < 18 years |

| Refusal of informed consent |

| Physician's decision that involvement in the trial was not in the patient's best interest |

| Patients with a medical indication for anticoagulation therapy at the time of inclusion (for example, diagnosis of venous thromboembolism, atrial fibrillation, mechanical valve prosthesis) |

| Patients with contraindications to anticoagulation (active bleeding, liver failure, blood dyscrasia, or prohibitive hemorrhagic risk in the investigator's assessment) |

| Use of strong inhibitors of cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and/or glycoprotein P (P-gp) (eg, protease inhibitors, ketoconazole, Itraconazole) and/or use of P-gp and strong inducers of CYP3A4 (how but not limiting rifampicin/rifampicin, rifabutin, rifapentine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine or St. John's wort) |

| Creatinine clearance <30 ml / min |

| Pregnancy or breastfeeding |

| Known HIV infection |

| Presence of one of the following uncontrolled or unstable cardiovascular diseases: stroke, ECG confirmed acute ischemia or myocardial infarction, and/or clinically significant dysrhythmia |

Randomization and Intervention

Randomization

Participants were randomly assigned at hospital discharge to one of two treatment groups based on a computer-generated randomization schedule prepared before the study. In group 1, patients received rivaroxaban 10 mg once daily for 30 days postoperative at hospital discharge. In group 2, patients received enoxaparin 40 mg SC once daily, continued at randomization, for 30 days postoperative. Patients were randomized electronically in a ratio of 1:1. Randomization was balanced using randomly swapped blocks. This was an open-label study.

The randomization list was generated using validated software (RedCap, version 11.2.2) and blocks of variable sizes. Investigators had to access this trial website and complete a simple medical record form to include the patient in the trial.

Intervention

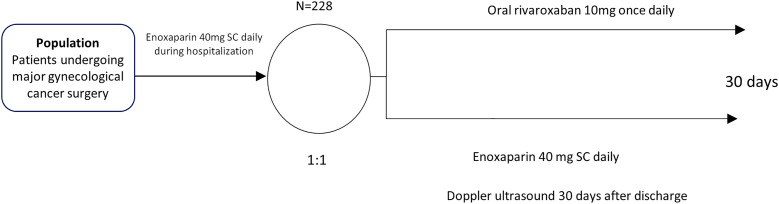

Patients undergone an initial screening evaluation during hospitalization. At discharge, they were randomized to either oral rivaroxaban 10 mg once daily or enoxaparin 40 mg SC once daily, both for 30 days. A mandatory lower limb Doppler ultrasound was carried out on day 30 as part of the primary efficacy endpoint.

Visit schedule

Patients were screened for the eligibility criteria during hospitalization and were randomized at hospital discharge. Medications were provided at randomization and were started within the first 24 h after hospital discharge and maintained for 30 days. At randomization, patients were encouraged to report in the protocol evaluations or by extra-telephone calls any symptoms suggestive of VTE or bleeding. In every consultation, the investigators performed detailed surveillance on chest pain, dyspnea, peripheral edema, and pain in the lower limbs. Investigators also actively pursued bleeding signs.

The first evaluation occurred on day seven after randomization and could be either by telephone call or at the outpatient clinic. The second evaluation was carried out on day 30 ± 5 at the outpatient clinic. On the same day, lower limbs venous duplex scan was performed. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design.

Primary study objective

To demonstrate that oral rivaroxaban 10 mg once daily initiated at hospital discharge is noninferior to enoxaparin 40 mg SC once daily for 30 days after major gynecological cancer surgery on a composite of VTE or VTE related death at 30 days after the intervention.

Study outcomes

The primary efficacy outcome was a composite of symptomatic objectively confirmed VTE (deep venous thrombosis [DVT], pulmonary embolism [PE], and asymptomatic ultrasonography-confirmed DVT or VTE-related death at 30 days postoperative.

The primary safety outcome was a combination of major bleeding plus clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding at 30 days postoperative. Major bleeding was defined according to International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) criteria,13 including fatal bleeding and/or symptomatic bleeding in a critical area or organ (eg, intracranial, intraspinal, intraocular, retroperitoneal, intra-articular, pericardial, or intramuscular with compartment syndrome) or bleeding requiring the transfusion of 2 units of packed red blood cells.

All nonmajor bleeds were considered minor and were divided into clinically relevant and not clinically relevant minor bleeds. Clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding (CRNMB) events were defined as events that did not meet the definition of major bleeding but were associated with medical intervention, unscheduled contact with a physician, temporary cessation of drug therapy, or any other discomfort, such as pain or impairment of activities of daily life. The remaining nonmajor bleeds were considered minor bleeds.

Sample size

The study was designed to test the hypothesis that rivaroxaban would be noninferior to parenteral enoxaparin for the primary efficacy outcome. The criteria for noninferiority required that the upper limits of the 95% confidence intervals were below prespecified margins for both the relative risk (2.0).

The sample size was calculated assuming the power of 80%, a significance level of 0.05, and the response anticipated for the occurrence of the primary efficacy endpoint of 7% in both groups (we have included a mandatory Doppler ultrasound on day 30 – a surrogate endpoint to detect asymptomatic events and expect increased events. With 440 patients enrolled, we would be able to see a difference of 6 percentage points, or 2%, in the rivaroxaban group. This 2% rate was considered clinically reasonable because we anticipate a higher compliance rate in the experimental arm. With a drop-out rate of 10%, 440 patients would be necessary (220 per arm).

Beyond the initial sample size calculation, a formal interim analysis by the Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) evaluating primarily safety was planned. The first formal interim analysis was intended when the first 200 patients enrolled and completed the 30-day follow-up visit.

Statistical analysis

The efficacy analysis tests were one-sided, with a type I error rate of 2.5%, assuming a two-sided 95% confidence interval. The cumulative incidence of the composite events was compared between the rivaroxaban and LMWH groups, and the relative risk (RR) or hazard ratio was estimated. For the safety analysis, statistical tests were two-sided, with a type I error rate of 5% and a two-sided 95% confidence interval. Noninferiority could be claimed if the upper limit of the 95% CI was less than 2.0.

Trial oversight

The study was designed and led by a Steering Committee composed of academic investigators and other experienced clinical researchers in this field. The data monitoring committee oversaw the data and safety of the study. All primary efficacy and principal safety events were centrally and independently adjudicated.

Data and Safety Monitoring Board and Clinical Events Committee

An independent DSMB monitored safety data on an ongoing basis with access to unblinded data. The DSMB reviewed results from a formal interim analysis once 200 patients had completed the study. The DSMB used a p-value <0.001 in the interim analysis to declare an overwhelming statistically significant difference in outcomes between study groups to guide their recommendations. An overall p-value <0.05 was used to assert statistical significance at the end of the study. A detailed DSMB charter provided trial-stopping rules for efficacy, safety, and futility.

The Clinical Events Committee (CEC) was composed of medical experts in the field of thrombosis. Committee members did not directly include study participants, were not involved in monitoring the VALERIA trial study, and had no direct operational responsibilities for conducting the study. Members analyzed all suspected outcome events described below that occurred after randomization as soon as they became available and evaluated and classified consistently and impartially, according to the clinical events charter, remaining blinded to the treatment assignment.

Data Sharing Statement

Anonymized participant data can be made available upon requests directed to the corresponding author. Proposals will be reviewed based on scientific merit. After approval of a proposal, data can be shared through a secure online platform after signing a data access agreement.

Results

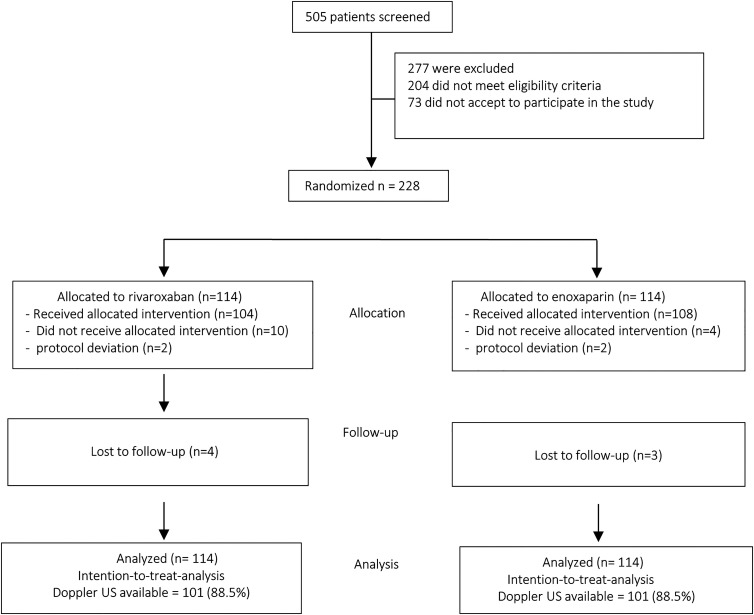

Between October 2020 and ended in March 2022, 505 patients were accessed for eligibility. The trial was stopped prematurely due to the low-than-expected event rates. The upper limit of 95% would not be below 2.0 with the programmed 440 patients. The study was, therefore, converted to exploratory and hypothesis-generating. Of the total patients who were screened, 204 (40.4%) did not meet eligibility criteria, and 73 (14.4%) did not agree to participate in the study. The remaining 228 (45.2%) patients were enrolled and randomly assigned to receive rivaroxaban (n = 114 [50%]) or enoxaparin (n = 114 [50%]). Seven patients (4 in the rivaroxaban group and 3 in the enoxaparin group) were not followed up on, with 2 considered protocol deviations. They were included in the intention-to-treat primary analysis. Thus, 104 received rivaroxaban, and 108 received enoxaparin for 30 days. The study flow diagram is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

CONSORT study flow diagram.

Baseline Characteristics

The median age was 55 years (range, 20.3-86.7 years); 51 women (23%) had advanced cancer (stages III and IV), and 217 women (99%) underwent open surgery. The demographic data did not differ between the two treatment groups. The baseline characteristics are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | Enoxaparin (n = 114) | Rivaroxaban (n = 114) | Total (n = 228) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 56 (20-82) | 54 (23-87) | 55 (20-87) | 0.2864 |

| Body mass index, median (range) | 28.1 (15.5-46.8) | 28.5 (14.7-48.0) | 28.3 (14.7-48.0) | 0.6033 |

| Caprini score | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| <5 | 60 (53) | 68 (60) | 128 (56) | 0.3502 |

| ≥5 | 54 (47) | 46 (40) | 100 (44) | |

| Suspected cancer site | ||||

| Cervical | 49 (43) | 47 (41) | 96 (42) | 0.4638 |

| Uterine | 31 (27) | 39 (34) | 70 (31) | |

| Ovarian | 34 (30) | 28 (25) | 62 (27) | |

| Surgical intervention | ||||

| Open | 110 (96) | 114 (100) | 224 (98) | 0.1217 |

| Minimally invasive | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | |

| Other | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | |

| Duration of surgery, median (range), min | 140.1 (40-355) | 142.9 (40-360) | 141.5 (40-360) | 0.7507 |

| Duration of hospitalization, days | 4.1 (1-38) | 3.3 (1-10) | 3.7 (1-38) | 0.5681 |

| Confirmed diagnosis by anatomopathological exam | ||||

| Malignant or borderline | 112 (49) | 109 (48) | 221 (97) | 0.4458 |

| Benign | 2 (1) | 5 (2) | 7 (3) | |

| Stage of malignant tumor | n = 112 | n = 109 | n = 221 | |

| In Situ | ||||

| Uterine | 8 (7) | 12 (11) | 20 (9) | 0.7111 |

| Cervical | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Ovarian | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 4 (2) | |

| Low (I or II) | ||||

| Uterine | 19 (17) | 24 (22) | 43 (19) | 0.8611 |

| Cervical | 36 (32) | 37 (34) | 73 (33) | |

| Ovarian | 12 (11) | 14 (13) | 26 (12) | |

| High (III or IV) | ||||

| Uterine | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 5 (2) | 0.6818 |

| Cervical | 13 (12) | 7 (6) | 20 (9) | |

| Ovarian | 18 (16) | 12 (11) | 30 (14) |

Primary Efficacy Outcomes

The primary efficacy outcome occurred in four (3.51%) of 114 patients assigned to rivaroxaban and 5 (4.39%) of 114 patients assigned to enoxaparin (relative risk 0.80, 95% CI 0.22 to 2.90; p = 0.7344).

Safety Outcomes

The safety outcome occurred in no patients in the rivaroxaban group (0%) and 3 patients (2.63%) in the enoxaparin group (hazard ratio, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.007 to 2.73; P = 0.1963). Minor bleeds occurred in 20 (17.54%) patients in the rivaroxaban group and in 16 (14.03%) patients in the enoxaparin group (hazard ratio,1.25; 95% CI 0.68 to 2.28; P = 0.4690). Minor bleeds were hematoma (0.8% vs 6.1%), surgical wound bleeds (4.3% vs 4.3%), and vaginal bleeding (7% vs 2.6%). The rates of other adverse events were similar in the two groups. Table 3 reports both the efficacy and safety results.

Table 3.

Primary efficacy and safety results.

| Participants, No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | Rivaroxaban (n = 114) | Enoxaparin (n = 114) | RR (95%CI) | P-value |

| Venous thromboembolism (symptomatic + asymptomatic VTE + VTE related death) | 4 (3.51%) | 5 (4.39%) | 0.80 (0.22—2.90) | 0.7344 |

| Symptomatic proximal | 3 (2.63%) | 2 (1.75%) | 1.50 (0.25—8.80) | 0.6535 |

| Symptomatic distal | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| Asymptomatic proximal | 1 (0.87%) | 2 (1.75%) | 0.50 (0.04—5.43) | 0.5690 |

| Asymptomatic distal | 0 | 1 (0.87%) | 0.33 (0.01—8.09) | 0.4997 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| VTE-related death | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| Bleeding (MB + CRNMB) | 0 | 3 (2.63%) | 0.14 (0.007 —2.73) | 0.1963 |

| MB | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| CRNMB | 0 | 3 (2.63%) | 0.14 (0.007 —2.73) | 0.1963 |

| Minor bleeding | 20 (17.54%) | 16 (14.03%) | 1.25 (0.68— 2.28) | 0.4690 |

Legend: MB: Major bleeding; CRNMB: Clinically Relevant Non-Major Bleeding; RR: Relative Risk; CI: Confidence Interval.

Net Clinical Benefit

The net clinical benefit looking at thrombotic events and major bleeding would was in line with the primary efficacy results (3.51% vs 4.39% [relative risk 0.80, 95% CI 0.22 to 2.90; p = 0.7344]), because no patient in both groups presented major bleeding events.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that post-operative thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban 10 mg daily for 30 days had similar rates of thrombotic and bleeding events compared to parenteral enoxaparin 40 mg daily in an high-risk population for VTE such as patients undergoing major gynecological cancer surgery.

VTE is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in women with gynecologic malignancies. Many VTE prophylaxis trials include few or no women with gynecologic cancer. There is minimal data on gynecologic cancer-specific populations, and the results of these studies represent the best available evidence to support treatment recommendations in these patients. They are usually extrapolated to VTE treatment and prevention for patients with gynecologic cancer.14

The ISTH guidelines (9a ACCP) suggest for high-VTE-risk patients undergoing abdominal or pelvic surgery for cancer who are not otherwise at high risk for major bleeding complications, extended-duration pharmacologic prophylaxis (4 weeks) with parenteral LMWH over limited-duration prevention (Grade 1B).9 However, persistence in parenteral anticoagulants for the management of cancer-associated thrombosis is challenging.15 Cost, adherence, pain, and bruising at the injection site are also issues.16

Oral rivaroxaban is potentially an alternative to parenteral LMWHs in patients undergoing surgery for primary gynecologic cancer. There was no significant difference in VTE, with fewer events on the rivaroxaban arm, driven by proximal deep-venous thrombosis (DVT) in both groups. No pulmonary embolisms (PE) occurred in both groups.

There was no significant difference in major or CRNM bleeding events between the two groups of this study, suggesting that rivaroxaban may also be a safe alternative to enoxaparin in this high-risk population. No major bleeds occurred, with bleeding events driven mainly by minor bleeds in both groups.

This is the second trial to evaluate a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) for VTE prevention after major gynecological cancer surgery. Apixaban was also compared to enoxaparin in this setting, looking for safety as the primary outcome. In 400 women enrolled, investigators found no statistically significant differences between the apixaban and enoxaparin groups for major bleeding events (1 patient [0.5%] vs 1 patient [0.5%]; odds ratio [OR], 1.04; 95%CI, 0.07-16.76; P > 0 .99), clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding events (12 patients [5.4%] vs 19 patients [9.7%]; OR, 1.88; 95%CI, 0.87-4.1; P = 0.11), venous thromboembolic events (2 patients[1.0%] vs 3 patients [1.5%]; OR, 1.57; 95%CI, 0.26-9.50; P = 0.68). The authors concluded that apixaban was a safe alternative to LMWH for thromboprophylaxis after gynecological cancer surgery and hypothesized its noninferiority for efficacy compared to the LMWH. In addition, the results suggested higher satisfaction measures in the apixaban group, with the same adherence rates.12 Interestingly, in this trial the incidence of ovarian cancer was 42%, while in the VALERIA trial the incidence of ovarian cancer was 27%. While in Saketh's trial the stage high (III/IV) was 39.5%, in the VALERIA trial it was 22%. This difference partly explains the lower-than-expected incidence of VTE in the VALERIA trial.

Strengths and Limitations

This study is the first to test rivaroxaban for postoperative VTE prophylaxis after major abdominal open surgery in a randomized prospective study, including a high-risk VTE population after primary gynecological cancer.

Limitations included its open-label design, a small sample size, a single-center protocol, and premature interruption due to lower-than-expected VTE events.

Our findings may shed light on a significant medical unmet need, VTE prophylaxis after major abdominal surgeries, with a more convenient oral agent that might increase compliance. Future trials with larger study populations, properly powered for efficacy and safety, are warranted to confirm our findings.

Conclusion

In patients undergoing major gynecological cancer surgery, thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban 10 mg daily for 30 days had similar rates of thrombotic and bleeding events to enoxaparin 40 mg daily. While the power is limited due to not reaching the intended sample size, our results support the hypothesis that DOACs might be an attractive alternative strategy to LMWH to prevent VTE in this high-risk population. Larger and adequately powered studies are warranted to confirm our findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Science Valley Research Institute for its thorough help in conducting this study, the staff of São Paulo State Public Women's Health Reference Center Hospital, investigators, study coordinators, DSMB, CEC, and study participants who made the VALERIA trial possible.

Footnotes

Authorship Contributions: ER, LBA and ALMLO conceived the trial and wrote the initial proposal. All other authors contributed intellectually to the protocol development. ER estimated the sample size and drafted the statistical analysis with the statistical group. ALMLO and RFOP actively enrolled patients for the trial. ER participated in all statistical analyses. JL and GYKS conducted the operational side of the trial. PGMBS, JCCG, and AVSM participated in the blinded CEC. The initial draft of the manuscript was written by ER, ALM, CMR, and RDL, who had full access to and verified all the data underlying the study. All authors had access to the data, significantly contributed to the manuscript, agreed to submit it for publication, and vouch for the data's integrity, accuracy, completeness, and fidelity to the trial protocol.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: ALM reports personal fees from Sanofi, Bayer, Pfizer, and Cardinal Health. LBA reports grants from Bayer, Pfizer, and the Brazilian Ministry of Science and Technology. RDL reports grants and personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Medtronic PLC, and Sanofi; and personal fees from Amgen, Bayer, and Boehringer Ingelheim, outside of the submitted work. ER reports grants and consulting fees from Bayer and Pfizer; grants from the Brazilian Ministry of Science and Technology; and personal fees from Aspen Pharma and Daiichi-Sankyo, outside the submitted work. AVSM reports personal fees from Sanofi, Bayer, Pfizer, Ferring, AstraZeneca, Astellas, Novartis.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Science Valley Research Institute,

ORCID iDs: Ariane Vieira Scarlatelli Macedo https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3453-8488

Pedro Gabriel Melo de Barros e Silva https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1940-4470

Jawed Fareed https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3465-2499

Eduardo Ramacciotti https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5735-1333

References

- 1.Abdol Razak NB, Jones G, Bhandari M, Berndt MC, Metharom P. Cancer-Associated thrombosis: an overview of mechanisms, risk factors, and treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2018;10(10):1–21. DOI: 10.3390/cancers10100380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim AS, Khorana AA, McCrae KR. Mechanisms and biomarkers of cancer-associated thrombosis. Transl Res. 2020;225(1):33–53. DOI: 10.1016/j.trsl.2020.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohashi Y, Ikeda M, Kunitoh H, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: design and rationale of a multicentre, prospective registry (cancer-VTE registry). BMJ Open. 2018;8(5):e018910. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weeks KS, Herbach E, McDonald M, Charlton M, Schweizer ML. Meta-Analysis of VTE risk: ovarian cancer patients by stage, histology, cytoreduction, and ascites at diagnosis. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2020;2020(1):2374716. DOI: 10.1155/2020/2374716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trinh VQ, Karakiewicz PI, Sammon J, et al. Venous thromboembolism after major cancer surgery: temporal trends and patterns of care. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(1):43–49. DOI: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comerota AJ, Ramacciotti E. A comprehensive overview of direct oral anticoagulants for the management of venous thromboembolism. Am J Med Sci. 2016;352(1):92–106. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):381S–453S. DOI: 10.1378/chest.08-0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Key NS, Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(5):496–520. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.19.01461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gould MK, Garcia DA, Wren SM, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e227S–e277S. DOI: 10.1378/chest.11-2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan NC, Weitz JI. Rivaroxaban for prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism. Future Cardiol. 2019;15(2):63–77. DOI: 10.2217/fca-2018-0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunstad JP, Krochmal DJ, Flugstad NA, Kortesis BG, Augenstein AC, Culbertson GR. Rivaroxaban for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in abdominoplasty: a multicenter experience. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;36(1):60–66. DOI: 10.1093/asj/sjv117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guntupalli SR, Brennecke A, Behbakht K, et al. Safety and efficacy of apixaban vs enoxaparin for preventing postoperative venous thromboembolism in women undergoing surgery for gynecologic malignant neoplasm: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e207410. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.7410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaatz S, Ahmad D, Spyropoulos AC, Schulman S, Subcommittee on Control of A. Definition of clinically relevant non-major bleeding in studies of anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolic disease in non-surgical patients: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(11):2119–2126. DOI: 10.1111/jth.13140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis JD. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of venous thromboembolic complications of gynecologic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(4):759–775. DOI: 10.1067/mob.2001.110957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaefer JK, Li M, Wu Z, et al. Anticoagulant medication adherence for cancer-associated thrombosis: a comparison of LMWH to DOACs. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19(1):212–220. DOI: 10.1111/jth.15153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomez-Outes A, Terleira-Fernandez AI, Lecumberri R, Suarez-Gea ML, Vargas-Castrillon E. Direct oral anticoagulants in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2014;134(4):774–782. DOI: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]