Abstract

Background

Previous clinical trials have demonstrated the potential efficacy of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (PARPis) in patients with cancer involving homologous recombination repair (HRR) gene-mutation. Moreover, HRR gene-mutated cancers are effectively treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) with the increase in tumor mutation burden. We have proposed to conduct a multicenter, single-arm phase II trial (IMAGENE trial) for evaluating the efficacy and safety of niraparib (PARPi) plus programmed cell death-1 inhibitor combination therapy in patients with HRR gene-mutated cancers who are refractory to ICIs therapy using a next generation sequencing-based circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and tumor tissue analysis.

Methods

Key eligibility criteria for this trial includes HRR gene-mutated tumor determined by any cancer gene tests; progression after previous ICI treatment; and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status ≤ 1. The primary endpoint is the confirmed objective response rate (ORR) in all patients. The secondary endpoints include the confirmed ORR in patients with HRR gene-mutation of ctDNA using the Caris Assure (CARIS, USA). The target sample size of the IMAGENE trial is 57 patients. Biomarker analyses will be performed in parallel using the Caris Assure, proteome analysis, and T cell repertoire analysis to reveal tumor immunosurveillance in peripheral blood.

Expected outcome

Our trial aims to confirm the clinical benefit of PARPi plus ICI combination therapy in ICI-resistant patients. Furthermore, through translational research, our trial will shed light on which patients would benefit from the targeted combination therapy for patients with HRR gene-mutated tumor even after the failure of ICIs.

Trial registration

The IMAGENE trial: jRCT, Clinical trial no.: jRCT2051210120, Registered date: November 9, 2021.

Keywords: Homologous recombination repair, Niraparib, PARP inhibitor, Immune checkpoint inhibitor, Tumor-agnostic therapy

Background

Homologous recombination (HR) is a multifactorial process in DNA repair involving the repair of double strand brakes (DSB) generated at the broken replication forks [1]. In particular, HR repair (HRR) genes such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 play a critical role in carrying out successful HR. In normal cells, DSBs are repaired by the HRR mechanism to prevent cell death. By contrast, in cells with HRR dysfunction (HR deficiency: HRD), the damage DNA accumulates because of unsuccessful DSB, eventually leading to cell death [2]. These cells rely on DNA single-strand break repair such as base exchange repair (BER) mechanisms, including Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), an enzyme required for BER to maintain genomic stability [3]. PARP inhibitors (PARPis) induce synthetic lethality in cells with HRD and consequently exhibit antitumor effects. Taking this effect into account, PARPis have undergone clinical approval for the treatment of ovarian, breast and prostate cancers involving HRR gene mutations [4–10].

Recently, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been introduced with the aim to improve patient outcomes as evidenced by the encouraging results of several clinical trials [11–16]. Interestingly, HRR gene mutations are found in a particular patient subset in many types of cancer, and these patients are thought to have susceptibility to ICIs because HRR gene mutations generate immunogenic cancer-antigens owing to the accumulation of somatic mutations [17]. Indeed, several studies have shown that alterations in DNA damage response and repair genes are associated with response to programmed cell death 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) blockade in patients with several types of cancer [18, 19]. Considering above, we can expect synergistic effects of PARPi plus ICI combination therapy for patients with HRR-gene mutations.

The SCRUM-Japan consortium of the Nationwide Cancer Genome Screening Project with an industry-academia collaboration started the MONSTAR-SCREEN project, which evaluates the presence of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) before and after initiating cancer treatments [20, 21]. This ctDNA assay can reveal comprehensive somatic genomic alterations that enable the assessment of predominant spatial and temporal intratumoral heterogeneity with minimal invasiveness [22]. Utilizing this platform, we propose an investigator-initiated trial (IMAGENE trial) of niraparib (PARPi) and pembrolizumab or nivolumab combination therapy for HRR gene-mutated solid cancer based on the findings of ctDNA as well as tissue genome screening in eight institutions (sample size: 57, enrollment: 1 years and 8 months).

For personalized immunotherapy, we believe this tumor-agnostic trial would create scientific breakthrough that may lead to better treatments for patients with HRR-gene mutations.

Methods

Study design and treatment

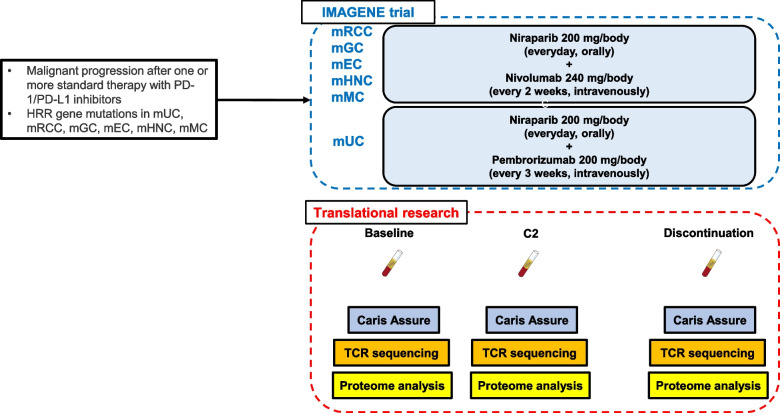

The present trial is a multicenter, single-arm, proof-of-concept (POC), phase II study. aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of combination therapy of niraparib plus nivolumab or pembrolizumab (PD-1 inhibitor) in patients with solid cancer involving HRR gene mutations. This study is conducted as a tumor-agnostic trial for patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC), metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC), metastatic gastric cancer (mGC), metastatic esophageal cancer (mEC), metastatic head and neck cancer (mHNC), and metastatic melanoma (mMC). HRR gene mutations were determined by tumor tissue analysis including FoundationOne CDx, OncoGuide NCC oncopanel, and Caris Molecular Profiling (Fig. 1). In this study, FoundationOne liquid CDx, Guardant 360, and Caris Assure are also used to screen patients harboring HRR gene mutations using ctDNA tests in blood samples (Fig. 1). The HRR genes are defined as BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, CDK12, CHEK2, PALB2, BARD1, BRIP1, CHEK1, FANCL, RAD51B, RAD51C, RAD51D, and RAD54L. This trial has been registered in the Japan Registry of Clinical Trials (jRCT2051210120).

Fig. 1.

Overall trial design. As the translational research, liquid biopsies for the IMAGENE trial will be performed at baseline, cycle 2, and after discontinuation of protocol treatment. C2; Cycle 2, mEC; metastatic esophageal cancer, mGC; metastatic gastric cancer, mHNC; metastatic head and neck cancer, mMC; metastatic melanoma, mRCC; metastatic renal cell carcinoma, mUC; metastatic urothelial carcinoma, PD-1; programmed cell death-1, PD-L1; programmed cell death ligand-1, TCR; T cell receptor

Patients

The eligibility criteria for this trial are presented in Table 1. Key eligibility criteria include the presence of HRR gene mutated tumors determined by an analysis of the tumor tissue or blood sample; tumor progression after treatment with a previous PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor; and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status score of ≤ 1. All patients are enrolled in the molecular profiling study, SCRUM-Japan MONSTAR-SCREEN-2 (UMIN000043899), which incorporate a tissue (Caris Molecular Profiling) and plasma multiomics approach (Caris Assure) based on artificial intelligence. Enrollment has started on April 2022 and will be completed on August 2023.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for the IMAGENE trial

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. Malignant progression after one or more standard therapy with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, and completion of standard therapy in principle |

1. Severe comorbidity a. Synchronous active malignancies b. Uncontrolled brain metastasis or leptomeningeal metastasis c. Active infectious disease d. Uncontrolled ascites, pleural effusion, or pericardial effusion requiring continued drainage e. Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus or hypertension f. Myocardial infarction, severe/unstable angina pectoris, symptomatic congestive heart failure of New York Heart Association Class II—IV within 6 months before enrollment g. Psychiatric diseases or psychiatric symptoms that were considered to cause difficulty in enrollment in a clinical trial |

| 2. Diagnosed with the target disease (unresectable advanced or recurrent urothelial cancer, renal cell carcinoma, gastric cancer, esophageal cancer, head and neck cancer, malignant melanoma with HRR gene mutation in the germline or somatic cells, which were detected by the specified tests) |

2. Underwent one of the following treatments before protocol treatment: a. Extensive surgery within 4 weeks b. Colostomy/ileostomy within 2 weeks c. Chemotherapy within 2 weeks d. Radiation therapy within 2 weeks |

| 3. Measurable lesions | 3. CTCAE Grade 2 adverse events due to previous therapy, which are not recovered |

| 4. Legal adult on informed consent | 4. History of PARP inhibitor treatments |

| 5. ECOG PS: 0 or 1 | 5. Intolerant to previous irinotecan therapy |

| 6. Appropriate physical function confirmed by laboratory values within 14 days before enrollment | 6. Comorbidity or history of uncontrollable hypertension |

| 7. (Female of childbearing potential) Agreed to contraception and not to donate oocytes from consent to 180 days after the last dose of the study drug | 7. Men/women who are unwilling to avoid pregnancy; women who are pregnant or breastfeeding; women with a positive pregnancy test |

| 8. (Male) Agreed to contraception from the start of study treatment to 180 days after the last dose of the study drug, and agreed not to donate sperms from the start of study treatment to 90 days after the last dose of the study drug or 120 days after the last dose of a PD-1 inhibitor, whichever is later | 8. Known active HCV or HIV infection |

| 9. Written consent to participate in the clinical trial | 9. Any other patients who are regarded as inadequate for trial enrollment by investigators |

In addition to this clinical trial, patients who do not meet all inclusion criteria, or those meet any of the exclusion criteria are enrolled in the natural history follow-up cohort and will be observed on follow up to collect information on anti-tumor treatment, post-treatment and survival every 3 months as a historical control (SCRUM-Japan registry, UMIN000028058).

Treatments

Patients with mRCC, mGC, mEC, mHNC, and mMC will be treated with niraparib 200 mg daily and nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks, whereas those with mUC will be treated with niraparib 200 mg daily and pembrolizumab 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks. Patients will receive therapy until reaching either disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. The dose of niraparib can be reduced to 200 mg daily according to adverse events during the treatment.

Endpoints and statistical analysis

The primary endpoint is the objective response rate (ORR) confirmed by the investigators' assessment in patients with HRR genes mutation determined by any cancer gene panel. The secondary endpoints include the confirmed ORR in patients with HRR gene mutations in ctDNA determined by Caris Assure, progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), disease control rate (DCR), duration of response (DOR), time to treatment failure (TTF), and change rate of tumor size, as determined by the investigators' assessment, and the incidence of adverse events (AEs). Efficacy will be evaluated according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) V.1.1 using computed tomography every 6 weeks until the end of cycle 12 (nivolumab) or 8 (pembrolizumab), and thereafter every 8 weeks. AEs are assessed according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events V.4.0 before the administration of the investigational drug on the day of administration. In this trial, the threshold of the ORR has been set to 16%, and the expected rate to 31%, as niraparib combined with ICIs based on the results of previous clinical trials of ICIs. Under this assumption, with a one-sided significance level of 5% and a power of 80%, the sample size required was calculated to be 57. The sample size for each tumor was set at 15 for mUC, 4 for mRCC, 15 for mGC, 8 for mEC, 13 for mHNC and 2 for mMC, based on feasibility and the expected proportion of participants.

All analysis will be based on the intention-to-treat principle. The baseline characteristics will be described as the mean and standard deviation, or median and quantiles (for continuous variables), or proportion (for categorical variables). The binomial test will be used to analyze the primary endpoint ORR and a threshold, and the Clopper-Pearson method will use the 95% confidence interval for ORR and DOR. Estimates of PFS, DCR, DOR, TTF, and OS will be used with the Kaplan–Meier method.

Biomarker analyses and translational research

ctDNA analysis using a targeted next-generation sequencing (Caris Assure) will be performed at baseline, Cycle 2, and after treatment discontinuation. We will also perform three types of analysis (namely, PD-L1 expression analysis, next-generation sequencing-based T cell repertoire analysis, and quantitative proteomics analysis) to investigate predictive biomarkers of response to this combination therapy. First, the expression level of PD-L1, a well-known biomarker of the clinical response to ICIs in cancer tissues, will be evaluated. Second, we will perform T cell repertoire analysis based on next-generation sequencing to determine whether T cell receptor (TCR) diversity in the peripheral blood can serve as a useful indicator of response to combination therapy. Third, we will perform a mass spectrometry-based quantitative proteomic analysis using plasma to identify candidate proteins as potential predictive biomarkers.

Discussion

The introduction of next-generation sequencing technologies and large-scale tumor molecular profiling tests have revolutionized the field of precision oncology [23]. Precision oncology has already transformed cancer treatment for both common and rare malignancies that are targeted by specific therapies to improve clinical outcomes in patients. HRR gene-mutated tumor are one of the rare fractions across cancers, which are reported to be approximately 3% – 20% [24–29], and require more effective treatment beyond PARPi monotherapy. In this regard, our trial will reveal some important points for selecting patients who benefit from a PARPi in combination with ICIs as tumor-agnostic therapy.

First, our trial could first reveal the real benefit of PARPi plus ICI combination therapy for patients who are refractory to previous treatment with ICIs for a subset of HRR gene-mutated tumors. Importantly, PARPis are compatible with ICIs for three reasons: 1) PARPis upregulate PD-L1 expression in cancer cells in vitro and in vivo which is a marker for response to ICIs; 2) PARPis release DNA from cancer cells and induce T cell activation through the release of interferon-γ by the activation of the STING pathway; and 3) PARPis change the tumor microenvironment to activate tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Considering these possible benefits, our trial could reveal additional effects of PARPi combined with ICI in ICIs-resistant cancers [17, 30].

Second, our trial could show whether patients with HRR gene-mutated solid tumors identified by ctDNA genotyping benefit from PARPi plus ICI similarly to patients identified by conventional tissue analysis. To date, only one study from our group has reported that pertuzumab plus trastuzumab showed similar efficacy in patients with mCRC with HER2 amplification in ctDNA and tumor tissues [31]. Considering that ctDNA may offer clinical advantages for assessing tumor heterogeneity associated with acquired resistance, our trial could contribute to the critical assessment for further use of ctDNA genotyping clinical trials.

Third, our trial results will help perform translational research to decipher the real benefit from PARPi plus ICI combination therapy and could clarify the dynamics of tumor immunosurveillance in both tissues and peripheral blood in our setting. We previously reported that peripheral TCR analysis and early ctDNA dynamics could predict clinical response to ICIs [32]. Franz et al. reported that the clinical utility of proteomic analysis may clarify the responders to PAPRi [33]. Given the additional effect of PAPRi for modulating the tumor microenvironment and cancer-specific T cells, our combined novel analysis could identify the subgroup that shows a good response to this combination therapy.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, the IMAGENE trial is the first phase II study to evaluate the efficacy, safety and POC of combination therapy with niraparib and ICI in patients with HRR gene-mutated tumor. For precision oncology, these findings will shed light on the potential value of targeted combination therapy for patients with HRR gene-mutated tumors even after the failure of ICIs treatment.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the patients and their families who participated in this trial; all the co-investigators and site personnel. We also thank the clinical trial office members in the Department of Medical Innovation, Osaka University Hospital (Yoko Kawamura, Kento Asano, and Tomoharu Dohi) and FiveRings Corporation (Harumi Sakata, Chiho Uegaki, Tatsushi Goto, and Hiroshi Miyamoto).

Abbreviations

- CTCAE

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Event

- ICI

Immune checkpoint inhibitor

- ORR

Objective response rate

- OS

Overall survival

- PARPi

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor

- PD-1

Programmed cell death-1

- PD-L1

Programmed cell death ligand-1

- PFS

Progression-free survival

Authors’ contributions

TK and NN participated in the entire coordinating of this trial, designed and prepared the protocol. NM, MS, ME, TO, TA, NS, YY, NT, MO, KN, TH, MN, TK, KN, TF, SO, YN, HB, and TY designed and prepared the protocol. EH is the chief statistician. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission and agreed to be accountable for the contents.

Funding

IMAGENE trial receives financial support from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED; grant Number, 21ck0106656h0001). Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. provides investigational drugs as well as financial support for the translational research. The funders had no role in the study design; in data collection, analysis, or interpretation; or in the writing of the report.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The IMAGENE trial is conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects, and the Clinical Trial Acts in Japan. Each trial has been approved by the institutional review board of Osaka University Hospital Certified Review Board.

All patients were required to sign written informed consent.

Registry and the Registration No. of the study/trial: This trial has been registered in the Japan Registry of Clinical Trials (jRCT2051210120).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

TK reports research funding supports from Takeda and Pfizer. NM reports honoraria from Janssen, Merck biopharma, and Sanofi and research funding supports from Janssen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Roche, MSD, Taiho, Astellas, Amgen, Eisai, Eli Lilly, PRA Health Science, Takeda, Pfizer, Seagen, Chugai, Abbvie, and Novartis. MS reports honoraria from Janssen, AstraZeneca, and Astellas and research funding support from Daiichi Sankyo. ME reports honoraria from ONO, Takeda, Novartis, Pfizer, Bristol, Janssen, MSD, Merck, AstraZeneca, and Eisai and research funding support from Sanofi, Bayer, Astellas, ONO, and Takeda. TO reports honoraria from Takeda. MO reports honoraria from Bayer, Bristol, Novartis, Ono, Merck, Takeda, MSD, and Pfizer. KN reports honoraria from Ono, Novartis, MSD, and Bristol, and consulting fees from Novartis and MSD. YN reports honoraria from Chugai, Merck Biopharma, and Guardant Health AMEA, and research funding support from Taiho, Chugai, Guardant Health, Genomedia, Daiichi Sankyo, Seagen, and Roche Diagnostics. HB reports honoraria from Taiho, Ono, and Eli Lilly Japan, and research funding support from Ono. TY reports honoraria from Chugai, Merck, Bayer, Ono, and MSD, and research funding from MSD, Daiichi Sankyo, Ono, Taiho, Amgen, Sanofi, Pfizer, Genomedia, Sysmex, Chugai, and Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim. NN reports honoraria from Takeda, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Merck Biopharma, Ono, and Bristol.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Murai J, Pommier Y. PARP trapping beyond homologous recombination and platinum sensitivity in cancers. Ann Rev Cancer Biol. 2019;3:131–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-030518-055914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen L, Martens JWM, Van Hoeck A, Cuppen E. Pan-cancer landscape of homologous recombination deficiency. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5584. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19406-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas A, Murai J, Pommier Y. The evolving landscape of predictive biomarkers of response to PARP inhibitors. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:1727–1730. doi: 10.1172/jci120388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Bono J, Mateo J, Fizazi K, Saad F, Shore N, Sandhu S, et al. Olaparib for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2091–2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, Friedlander M, Vergote I, Rustin G, et al. Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1382–1392. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, Oza AM, Mahner S, Redondo A, et al. Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2154–2164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pujade-Lauraine E, Ledermann JA, Selle F, Gebski V, Penson RT, Oza AM, et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1274–1284. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez-Martin A, Pothuri B, Vergote I, DePont CR, Graybill W, Mirza MR, et al. Niraparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2391–2402. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robson M, Im SA, Senkus E, Xu B, Domchek SM, Masuda N, et al. Olaparib for metastatic breast cancer in patients with a germline BRCA mutation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:523–533. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Litton JK, Rugo HS, Ettl J, Hurvitz SA, Gonçalves A, Lee KH, et al. Talazoparib in patients with advanced breast cancer and a germline BRCA mutation. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:753–763. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, George S, Hammers HJ, Srinivas S, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1803–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellmunt J, de Wit R, Vaughn DJ, Fradet Y, Lee JL, Fong L, et al. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1015–1026. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang YK, Boku N, Satoh T, Ryu MH, Chao Y, Kato K, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer refractory to, or intolerant of, at least two previous chemotherapy regimens (ONO-4538-12, ATTRACTION-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390:2461–2471. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31827-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato K, Cho BC, Takahashi M, Okada M, Lin CY, Chin K, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma refractory or intolerant to previous chemotherapy (ATTRACTION-3): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1506–1517. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30626-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferris RL, Blumenschein G, Jr, Fayette J, Guigay J, Colevas AD, Licitra L, et al. Nivolumab for Recurrent Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1856–1867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weber JS, D’Angelo SP, Minor D, Hodi FS, Gutzmer R, Neyns B, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:375–84. 10.1016/s1470-2045(15)70076-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Yarchoan M, Johnson BA, 3rd, Lutz ER, Laheru DA, Jaffee EM. Targeting neoantigens to augment antitumour immunity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:209–222. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teo MY, Seier K, Ostrovnaya I, Regazzi AM, Kania BE, Moran MM, et al. Alterations in DNA damage response and repair genes as potential marker of clinical benefit from PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in advanced urothelial cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1685–1694. doi: 10.1200/jco.2017.75.7740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Labriola MK, Zhu J, Gupta RT, McCall S, Jackson J, Kong EF, et al. Characterization of tumor mutation burden, PD-L1 and DNA repair genes to assess relationship to immune checkpoint inhibitors response in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8:e000319. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2019-000319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamura Y, Fujisawa T, Taniguchi H, Bando H, Okamoto W, Tsuchihara K, et al. SCRUM-Japan GI-SCREEN and MONSTAR-SCREEN: Path to the realization of biomarker-guided precision oncology in advanced solid tumors. Cancer Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1111/cas.15132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taniguchi H, Nakamura Y, Kotani D, Yukami H, Mishima S, Sawada K, et al. CIRCULATE-Japan: Circulating tumor DNA-guided adaptive platform trials to refine adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2021;112:2915–2920. doi: 10.1111/cas.14926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parikh AR, Leshchiner I, Elagina L, Goyal L, Levovitz C, Siravegna G, et al. Liquid versus tissue biopsy for detecting acquired resistance and tumor heterogeneity in gastrointestinal cancers. Nat Med. 2019;25:1415–1421. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0561-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malone ER, Oliva M, Sabatini PJB, Stockley TL, Siu LL. Molecular profiling for precision cancer therapies. Genome Med. 2020;12:8. doi: 10.1186/s13073-019-0703-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson AG, Kim J, Al-Ahmadie H, Bellmunt J, Guo G, Cherniack AD, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cell. 2017;171(540–56):e25. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato Y, Yoshizato T, Shiraishi Y, Maekawa S, Okuno Y, Kamura T, et al. Integrated molecular analysis of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:860–867. doi: 10.1038/ng.2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma Nature. 2014;513:202–209. doi: 10.1038/nature13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Integrated genomic characterization of oesophageal carcinoma Nature. 2017;541:169–175. doi: 10.1038/nature20805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heeke AL, Pishvaian MJ, Lynce F, Xiu J, Brody JR, Chen WJ, et al. Prevalence of homologous recombination-related gene mutations across multiple cancer types. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2018:17. doi: 10.1200/po.17.00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim KB, Soroceanu L, de Semir D, Millis SZ, Ross J, Vosoughi E, et al. Prevalence of homologous recombination pathway gene mutations in melanoma: rationale for a new targeted therapeutic approach. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141:2028. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2021.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Césaire M, Thariat J, Candéias SM, Stefan D, Saintigny Y, Chevalier F. Combining PARP inhibition, radiation, and immunotherapy: A possible strategy to improve the treatment of cancer? Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3793. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura Y, Okamoto W, Kato T, Esaki T, Kato K, Komatsu Y, et al. Circulating tumor DNA-guided treatment with pertuzumab plus trastuzumab for HER2-amplified metastatic colorectal cancer: a phase 2 trial. Nat Med. 2021;27:1899–1903. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01553-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kato T, Kiyotani K, Tomiyama E, Koh Y, Matsushita M, Hayashi Y, et al. Peripheral T cell receptor repertoire features predict durable responses to anti-PD-1 inhibitor monotherapy in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Oncoimmunol. 2021;10:1862948. doi: 10.1080/2162402x.2020.1862948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franz A, Coscia F, Shen C, Charaoui L, Mann M, Sander C. Molecular response to PARP1 inhibition in ovarian cancer cells as determined by mass spectrometry based proteomics. J Ovarian Res. 2021;14:140. doi: 10.1186/s13048-021-00886-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.