Abstract

Objective:

To establish and validate a model comprising clinical and radiological features to pre-operatively predict post-resection hepatic metastasis (HM) in patients with gastric adenocarcinoma (GAC).

Methods:

We retrospectively analyzed 461 patients (HM, 106 patients); and non-metastasis (NM, 355 patients) who were confirmed to have GAC post-surgery. The patients were randomly divided into the training (n = 307) and testing (n = 154) cohorts in a 2:1 ratio. The main clinical risk factors were filtered using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator algorithm according to their diagnostic value. The selected factors were then used to establish a clinical–radiological model using stepwise logistic regression. The Akaike’s information criterion and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were used to evaluate the prediction performance of the model.

Results:

Logistic regression analysis showed that the peak enhancement phase, tumor location, alpha-fetoprotein, cancer antigen (CA)−125, CA724 levels, CT-based Tstage and arterial phase CT values were important independent predictors. Based on these predictors, the areas under the ROC curve of the training and testing cohorts were 0.864 and 0.832, respectively, for predicting post-operative HM.

Conclusion:

This study built a synthetical nomogram using the pre-operative clinical and radiological features of patients to predict the likelihood of HM occurring after GAC surgery. It may help guide pre-operative clinical decision-making and benefit patients with GAC in the future.

Advances in knowledge:

1. The combination of clinical risk factors and CT imaging features provided useful information for predicting HM in GAC.

2. A clinicoradiological nomogram is a tool for the pre-operative prediction of HM in patients with GAC.

Introduction

Gastric adenocarcinoma (GAC) is the fifth most common cancer and the third most common cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. In clinical practice, adjuvant chemotherapy is usually recommended for greater than Stage IB or II carcinoma, even after R0 resection, although the prognosis of GAC is still relatively poor. The most common metastatic sites of GAC are the distant lymph nodes (56%), hepatic lymph nodes (53%), and peritoneum (51%) 1 ; the type of recurrence, metastasis, and diffusion of GAC are closely related to its histological characteristics. 2 In clinical practice, CT is the most commonly used pre-operative imaging method to detect metastasis in patients with GAC because of its affordability and relatively few contraindications. As the commonest imaging method for detecting hepatic metastasis (HM), CT can verify the shape, density, and enhancement mode of GAC, as well as evaluate the relationship between the tumor and presence of distant metastasis, which provides more diagnostic information and allows for Tumor Node Metastasis (TNM) staging before surgery. Detecting micrometastases in the early stages of GAC is difficult. Although the lymph nodes and peritoneum are the commonest metastatic sites of GAC, the prognosis is often determined by the presence of hepatic metastasis. The timing and occurrence of HM after surgery in patients with GAC are closely related to its prognosis, and males are more likely to experience tumor recurrence and HM than females, especially in patients with Stage III carcinoma. 3

To date, there are no studies combining clinical risk factors and CT imaging features pre-operatively predict HM in patients with GAC. Hence, we aimed to investigate the diagnostic value of essential clinical risk factors and CT enhancement characteristics, including the peak enhancement phase (PEP) of the primary lesion and CT attenuation values, in predicting HM. Further, we aimed to establish and validate a CT-based nomogram as an individualized clinical predictive tool for patients with HMs of GAC to provide an objective treatment basis for the clinical selection of high-risk post-operative liver metastasis patients with pre-operative perioperative chemotherapy.

Methods and materials

Patients

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Lanzhou University Second Hospital, who waived the requirement for informed consent from the patients.

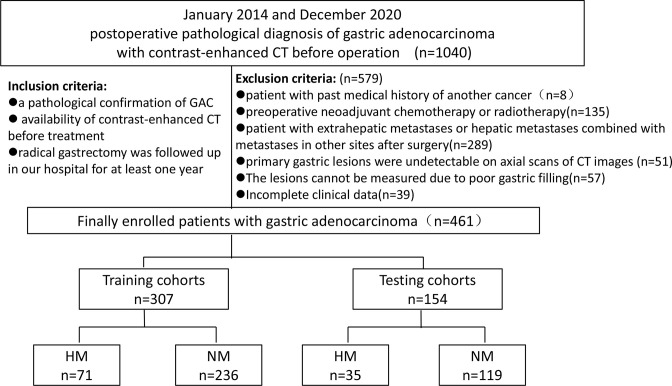

We enrolled 1040 consecutive patients with GAC between January 2014 and December 2020 (Figure 1). The patients who fulfilled the following criteria were included: (i) a pathological confirmation of GAC; (ii) availability of contrast-enhanced CT before treatment; and (iii) radical gastrectomy was followed-up in our hospital (Lanzhou University Second Hospital) for at least one year.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study enrollment. GAC, gastric adenocarcinoma; HM, hepatic metastasis; NM, non-metastasis.

The exclusion criteria were: (i) patients with past medical history of another cancer (n = 8); (ii) pre-operative neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy (n = 135); (iii) patient with extrahepatic metastases or hepatic metastases combined with metastases in other sites after surgery (n = 289); (iv) primary gastric lesions were undetectable on axial scans of CT images (n = 51); (v) the lesions cannot be measured due to poor gastric filling (n = 57); and (vi) incomplete clinical data (n = 39).

Finally, 461 patients (female, 110; male, 351; mean age, 56.065 ± 9.488 years; age range, 28–81 years) were enrolled into the study. The median time interval was 242 days. There were 11 patients in whom the metastases occurred after >2 years. The patients were randomly divided into the training (n = 307) and testing (n = 154) cohorts in a 2:1 ratio; the prevalence of HM in the training and testing cohorts was 21.13 and 22.73%, respectively.

We collected clinical data, including patient sex, age, location of GAC, Borrmann and Lauren type, degree of tissue differentiation, CT-based TN stage, pathologic TN-stage, tumor marker level, mode of operation, and regular chemotherapy after surgery. Patients were monitored every 3–6 months in the first 2 years post-operation, and every 6–12 months until the fifth year. Regarding the follow-up time of the HM group, the shortest period of HM occurred in 28 days and the longest period occurred in 1319 days. The median recurrence-free survival is 360 ± 322 days. The cut-off time of the NHM group was December 2020 without any metastasis or recurrence. Median follow-up time was 736 ± 522 days. Post-operative image detection method was enhanced CT or MRI. Five patients were diagnosed by needle biopsy, 10 by enhanced MRI, and the rest by enhanced abdominal CT. During each follow-up consultation, we obtained the medical history, performed physical examination, CT/MRI and other imaging examinations, and evaluated laboratory tumor markers.

CT image acquisition

All patients ingested 800–1000 ml of water to distend the stomach prior to CT. During scanning, patients were instructed to suspend respiration; all examinations were performed on a Discovery CT750 HD system (GE Healthcare, IL) and included triphasic enhanced scanning in the arterial- (AP), venous- (VP), and delayed phases (DP). Enhanced CT was performed with a 0.5 ms switch of tube voltage between 140 kVp and 80 kVp; tube current, 350 mA; pitch, 0.984:1; rotation time, 0.75 s; and reconstructed layer thickness, 1.25 mm. The scanning range was measured from the diaphragmatic dome to the symphysis pubis. Non-ionic contrast material, iohexol (370 mg I/mL; GE Healthcare), at 0.9 ml/kg of body weight (total volume, 60–110 ml) and flow rate of 3–4 ml s−1 was injected via a peripheral vein using a dual high-pressure syringe. The AP acquisition time was triggered 9 s after the attenuation of the diaphragmatic abdominal aorta reached 100 HU (SmartPrep; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA), while the VP and DP followed 30 s and 70 s after initiation, respectively. Raw data were reconstructed to 1.25 mm slice images using projection-based decomposition software; an additional 40% adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction algorithm was applied to suppress image noise.

Image analysis

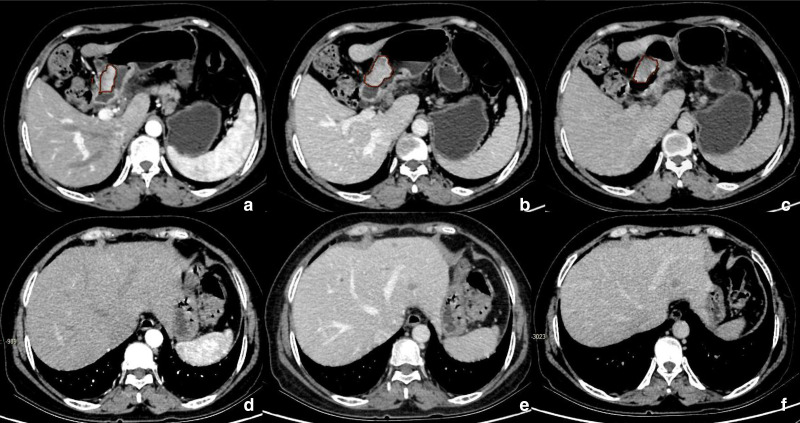

Two senior radiologists used the double-blind method to analyze the pre-operative, triphasic-enhanced abdominal CT images of the patients. To ensure the reliability of the measurement results, we only referred to the gastroduodenoscopy results obtained before the measurement, to confirm the accuracy of the position of the tumors. Image analysis included both subjective and objective analyses; for the subjective analysis, the radiologists visually determined the PEP at which the tumor showed the highest attenuation value among the three phases in each case. If the two doctors disagree, a third, senior doctor was consulted to reach a consensus. For the objective analysis, the radiologists traced the entire tumor as the region of interest (ROI); the CT attenuation value of the ROI was determined for each phase. The ROI was measured at the largest and clearest position of the axial tumor, avoiding the necrotic area as far as possible; the entire GAC region was considered the target area of the ROI. Contours were drawn within the borders of the primary tumor masses to avoid partial volume effects—including adjacent air, fat, vessels, normal tissue, and surrounding organs—and the CT values of the ROI were measured in the AP, VP, and DP. The average of the values determined by the two doctors were considered as the final measurements and recorded. Figure 2 shows the CT images and measurement methods for cases of HM.

Figure 2.

A 53-year-old female with hepatic metastasis after surgery for gastric adenocarcinoma. Multiple hepatic metastases were found on enhanced CT 91 days post-operation for gastric antrum cancer. a, b, and c are pre-operative CT images of gastric cancer in the arterial, venous, and delayed phases, respectively; the drawn areas are ROI diagrams to measure CT values for gastric cancer. d, e, and f are CT images of the arterial, venous, and delayed phases, respectively; hepatic metastasis was first identified after the operation, clearly demonstrating multiple hepatic metastatic tumors. ROI, region of interest.

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were performed using the R software package (v. 3.6.3; http://www.Rproject.org). First, we built a logistic regression model that could generate a nomogram to discriminate between HM and NM. The student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, as well as the χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests, were used to compare the triphasic-enhanced CT values and clinical factors between the HM and NM groups. Statistically significant features determined via univariate analysis were further analyzed using a multivariate logistic regression model to identify the key indicators of HM. A backward stepwise selection was applied, in which the stopping rule was based on the likelihood-ratio test with the Akaike’s information criterion. A quantitative and easy-to-use nomogram, designed to discriminate between HM and NM, was then built based on the final regression coefficient.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to evaluate the diagnostic capabilities of the nomogram, after which the area under the curve (AUC) and its 95% confidence interval, sensitivity, and specificity were calculated. Calibration curves were used to assess the goodness of fit of the nomogram. To verify the clinical usefulness of the nomogram, we quantified the net benefit of data acquisition at different threshold probabilities through decision curve analysis (DCA). All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical and CT imaging characteristics

Clinical features and statistics of patients in both the training and testing cohorts are presented in Table 1. The median time interval was 242 days.11 patients developed metastases after >2 years. Only 51 patients developed hepatic metastases within 1 year of radical surgery, and 44 patients developed hepatic metastases between 1 and 2 years after surgery. The two independent readers reached agreement on the different imaging features in the majority of cases. Disagreement occurred in 5/461 (1.08%) cases for PEP, 6/461 (1.30%) cases for cT-stage, 2/461 (0.43%) cases for cN-stage, 2/461 (0.43%) cases for the arterial phase CT values, 4/461 (0.87%) cases for the venous phase CT values, 3/461 (0.65%) cases for the delayed phase CT values. Consensus was reached in these cases by consulting a highly experienced chief physician of abdominal imaging with 15 years of experience.

Table 1.

Comparison of HM and NM in the training and testing cohorts

| Characteristic | Training cohort | Testing cohort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HM | NM | p- value | HM | NM | p- value | |

| Gender (%) | 0.219 | 0.897 | ||||

| Male | 57 (24.9%) | 172 (75.1%) | 28 (23.0%) | 94 (77.0%) | ||

| Female | 14 (17.9%) | 64 (82.1%) | 7 (21.9%) | 25 (78.1%) | ||

| Age (in years) | 56.61 ± 8.70 | 56.28 ± 9.81 | 0.246 | 55.71 ± 9.53 | 55.42 ± 9.35 | 0.871 |

| Tumor location | 0 | 0.477 | ||||

| EGJ | 22 (53.7%) | 19 (46.3) | 4 (33.3%) | 8 (66.7%) | ||

| Gastric body | 24 (25.5%) | 70 (74.5) | 11 (26.2%) | 31 (73.8%) | ||

| Gastric antrum | 25 (14.5) | 147 (85.5%) | 20 (20.0%) | 80 (80.0%) | ||

| HD | 0.45 | 0.101 | ||||

| Poor | 39 (21.0%) | 147 (79.0%) | 23 (25.6%) | 67 (74.4%) | ||

| Moderate | 30 (27.3%) | 80 (72.7%) | 12 (21.4%) | 44 (78.6%) | ||

| Well | 2 (18.2%) | 9 (81.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (100%) | ||

| Borrmann type | 0.002 | 0.448 | ||||

| I | 9 (33.3%) | 18 (66.7%) | 4 (40.0%) | 6 (60.0%) | ||

| II | 9 (23.7%) | 29 (76.3) | 5 (21.7%) | 18 (78.3%) | ||

| III | 47 (20.0%) | 188)80.0%) | 26 (21.5%) | 95 (78.5%) | ||

| IV | 6 (85.7%) | 1 (14.3%) | ||||

| Lauren type | 0.99 | 0.812 | ||||

| Intestinal | 27 (23.5%) | 88 (76.5%) | 13 (20.3%) | 51 (79.7%) | ||

| Diffuse | 25 (23.1%) | 83 (76.9%) | 13 (23.6%) | 42 (76.4%) | ||

| Mixed | 19 (22.6%) | 65 (77.4%) | 9 (25.7%) | 26 (74.3%) | ||

| Pathology T stage | 0 | 0 | ||||

| T1 | 1 (3.8%) | 25 (96.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 16 (100%) | ||

| T2 | 9 (13.8%) | 56 (86.2%) | 2 (6.9%) | 27 (93.1%) | ||

| T3 | 7 (6.3%) | 105 (93.8%) | 5 (8.2%) | 56 (91.8%) | ||

| T4 | 54 (51.9%) | 50 (48.1%) | 28 (58.3%) | 20 (41.7%) | ||

| Pathology N stage | 0 | 0 | ||||

| N0 | 7 (24.3%) | 98 (93.3%) | 3 (5.6%) | 51 (94.4%) | ||

| N1 | 45 (45.9%) | 53 (54.1%) | 18 (40.0%) | 27 (60.0%) | ||

| N2 | 16 (25.8%) | 46 (74.2%) | 13 (40.6) | 19 (59.4) | ||

| N3 | 3 (7.1%) | 39 (92.9%) | 1 (4.3%) | 22 (95.7%) | ||

| Her-2 lever | 0.207 | 0.447 | ||||

| Negative | 36 (26.3%) | 101 (73.7%) | 17 (27.0%) | 46 (73.0%) | ||

| Positive | 35 (20.6%) | 135 (79.4%) | 18 (19.8%) | 73 (80.2%) | ||

| LVI | 0.263 | 0.121 | ||||

| Negative | 8 (15.1) | 45 (84.9%) | 4 (12.5%) | 28 (87.5%) | ||

| Positive | 63 (24.8%) | 191 (75.2%) | 31 (25.4%) | 91 (74.6%) | ||

| Elevated tumor markers | ||||||

| AFP | 13 (65.0%) | 7 (35.0%) | 0 | 4 (40.0%) | 6 (60.0%) | 0.338 |

| CEA | 35 (35.4%) | 64 (64.6%) | 0.001 | 15 (38.5%) | 24 (61.5%) | 0.007 |

| CA199 | 20 (33.9%) | 39 (66.1%) | 0.029 | 9 (40.9%) | 13 (59.1%) | 0.028 |

| CA125 | 11 (57.9%) | 8 (42.1%) | 0.001 | 3 (27.3%) | 8 (72.7%) | 0.709 |

| CA724 | 32 (48.5%) | 34 (51.5%) | 0 | 9 (37.5%) | 15 (62.5%) | 0.06 |

| Operation procedure | 0.503 | 0.118 | ||||

| DG | 30 (19.7%) | 122 (80.3%) | 13 (18.8%) | 56 (81.2%) | ||

| PG | 13 (27.1%) | 35 (72.9%) | 4 (14.3%) | 24 (85.7%) | ||

| TG | 28 (26.4%) | 79 (73.6%) | 18 (31.6) | 39 (68.4%) | ||

| Surgery approach | 0.564 | 0.849 | ||||

| Open gastrectomy | 20 (21.1%) | 75 (78.9%) | 10 (21.7%) | 36 (78.3%) | ||

| Laparoscopic | 51 (24.1%) | 161 (75.9%) | 25 (23.1%) | 83 (76.9%) | ||

| Lymphadenectom | 0.637 | 0.338 | ||||

| D0 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (100%) | ||||

| D1 | 6 (33.3%) | 12 (66.7%) | 4 (40.0%) | 6 (60.0%) | ||

| D2 | 65 (22.6%) | 223 (77.4%) | 31 (21.5%) | 113 (78.5%) | ||

| PAC | 0.033 | 0.003 | ||||

| No | 4 (18.2%) | 18 (81.8%) | 2 (13.3%) | 13 (86.7%) | ||

| Incompletion | 24 (34.8%) | 45 (65.2%) | 16 (44.4%) | 20 (55.6%) | ||

| Completion (6–8 times) | 43 (19.9%) | 173 (80.1%) | 17 (16.5%) | 86 (83.5%) | ||

| CT-based T stage | 0 | 0 | ||||

| T1 | 1 (16.7%) | 5 (83.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (100.0%) | ||

| T2 | 4 (6.5%) | 58 (93.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 32 (100.0%) | ||

| T3 | 38 (24.2%) | 119 (75.8%) | 16 (22.5%) | 55 (77.5%) | ||

| T4 | 28 (34.1%) | 54 (65.9%) | 19 (41.3%) | 27 (58.7%) | ||

| CT-based N stage | 0 | 0 | ||||

| N0 | 4 (4.5%) | 84 (95.5%) | 2 (4.3%) | 45 (95.7%) | ||

| N1 | 37 (35.9%) | 66 (64.1%) | 19 (35.8%) | 34 (64.2%) | ||

| N2 | 24 (31.6%) | 52 (68.4%) | 13 (40.6%) | 19 (59.4%) | ||

| N3 | 6 (15.0%) | 34 (85.0%) | 1 (4.5%) | 21 (95.5%) | ||

| PEP (%) | 0 | 0 | ||||

| AP | 29 (42.6%) | 39 (57.4%) | 18 (47.7%) | 20 (52.6%) | ||

| VP | 35 (29.7%) | 83 (70.3%) | 14 (27.5%) | 37 (72.5%) | ||

| DP | 7 (5.8%) | 114 (94.2%) | 3 (4.6%) | 62 (95.4%) | ||

| AP CT value (HU) | 94.20 ± 20.29 | 79.03 ± 21.79 | 0.689 | 97.17 ± 22.40 | 76.76 ± 22.69 | 0 |

| VP CT value (HU) | 98.69 ± 21.73 | 87.06 ± 20.74 | 0.567 | 93.34 ± 18.73 | 82.87 ± 21.77 | 0 |

| DP CT value (HU) | 78.08 ± 15.37 | 80.40 ± 19.20 | 0.091 | 74.91 ± 14.33 | 76.68 ± 16.83 | 0.574 |

AP, arterial phase; DP, delayed phase; EGJ, esophagogastric junction; HM, hepatic metastasis; NM, non-metastasis; PEP, peak enhancement phase; VP, venous phase.

Note: A Fisher’s exact (n < 5) or χ 2 (n ≥ 5) test was used to compare the differences in categorical variables (Gender, Tumor location, HD, Borrmann type, Lauren type, Pathology T stage, Pathology N stage, Her-2, LVI, Elevated tumor markers, Operation procedure, Open or Laparoscopic gastrectomy, Lymphadenectom, PAC, CT-based T and N stage, and PEP), while a two-sample t-test was used to compare the differences in age and tumor triphasic-enhanced CT values.

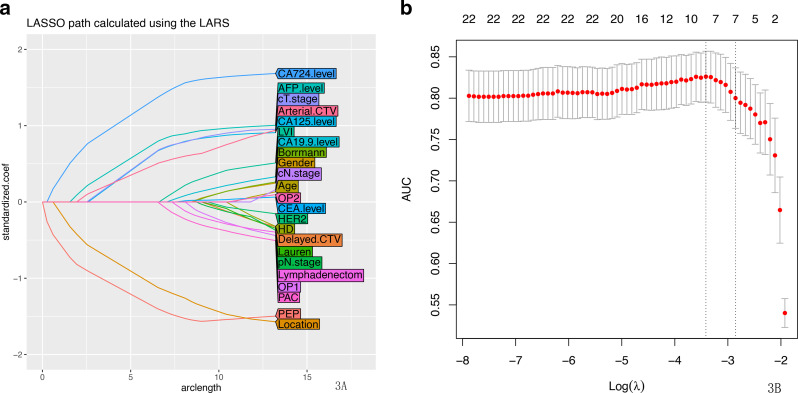

There were no significant differences in clinical characteristics between the cohorts, nor within the HM and NM groups. Using multiple logistic regression analysis, factors including PEP, tumor location, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), cancer antigen (CA)-125, CA724 levels, CT-based T stage(cT.stage) and Arterial phase CT values(Arterial.CTV) were selected from the patients in the training cohort using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression model (Figure 3A and B).

Figure 3.

(a) LASSO coefficient profiles of the 23 hepatic metastasis-related features. A coefficient profile plot was produced against the log (λ) sequence. (b) Feature selection using the LASSO binary logistic regression model. The differentiation performance of the radiologic features was explored on the ROC curve. Tuning parameter (λ) selection in the LASSO model employed fivefold cross-validation via the maximum AUC. A λ value of 0.016 was selected (1-SE criteria) according to fivefold cross-validation. AUC, area under the curve; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Development of individualized prediction model for HM

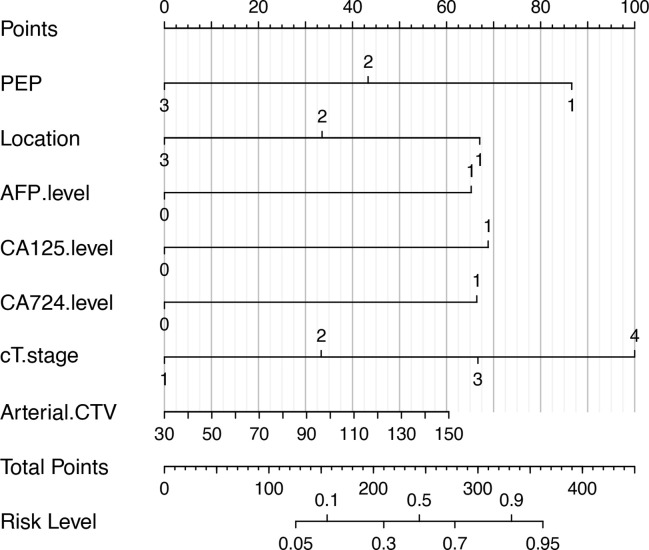

Statistically significant indicators in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression model; PEP, tumor location, AFP, CA125, CA724 levels, cT.stage and Arterial.CTV were identified as independent predictors of HM (Table 2). PEP and tumor location were negatively correlated with post-operative liver metastases from gastric adenocarcinoma, whereas other predictors were positively correlated (Table 3). A quantitative nomogram was constructed for individualized, predicted HM based on these parameters (Figure 4).

Table 2.

Risk factors of hepatic metastasis in gastric adenocarcinoma

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| PEP | 0.34 (0.22,0.52) | 0.000 |

| Location | 0.50 (0.35,0.72) | 0.000 |

| AFP.level | 2.74 (1.06,7.06) | 0.037 |

| CA125.level | 4.28 (1.57,11.66) | 0.004 |

| CA724.level | 4.44 (2.39,8.24) | 0.000 |

| cT-stage | 2.70 (1.77,4.11) | 0.000 |

| Arterial.CTV | 1.02 (1.00,1.03) | 0.046 |

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; Arterial.CTV, arterial phase CT values; OR, odds ratio; PEP, peak enhancement phase.

Table 3.

Correlations between variables and model coefficient

| Variables | Model coefficient | Std. error | t-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEP | −1.079 | 0.284 | −3.80 |

| Location | −0.835 | 0.226 | −3.69 |

| AFP.level | 1.625 | 0.633 | 2.57 |

| CA125.level | 1.715 | 0.622 | 2.76 |

| CA724.level | 1.654 | 0.381 | 4.34 |

| cT-stage | 0.830 | 0.265 | 3.14 |

| Arterial.CTV | 0.013 | 0.010 | 1.31 |

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; Arterial.CTV, arterial phase CT values; CA, cancer antigen; PEP, peak enhancement phase.

Figure 4.

The developed clinical and radiologic features nomogram for predicting the probability of HM. For the PEP, 1 stands for AP, 2 stands for the VP, and 3 stands for DP. For the location, 1 stands for upper, 2 stands for middle, and 3 stands for lower. For the AFP, CA125, and CA724 levels, 0 represents within the normal value while 1 represents above the normal value. For the cT stage, 1 is for T1 stage, 2 is for T2 stage, 3 is for T3 stage, and 4 is for T4 stage. To locate the patient’s PEP, draw a line straight up to the x-axis to establish the score associated with that site. Repeat the same for the other covariates (tumor location, pT stage, AFP level, CA125 level, CA724 level). By summing the scores of each point and locating on the total score scale, the estimated probability of HM could be determined. AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; AP, arterial phase; Arterial.CTV, arterial CT values; DP, delayed phase; HM, hepatic metastasis; PEP, peak enhancement phase; VP, venous phase.

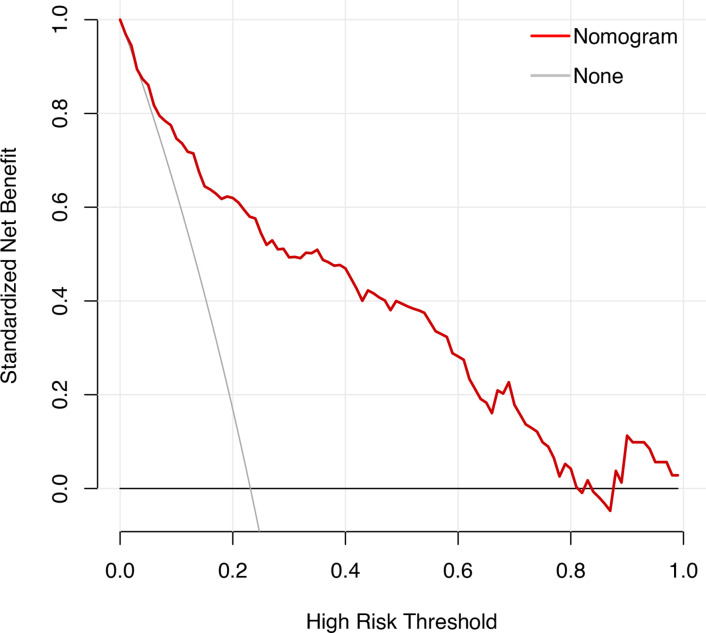

The nomogram had an excellent predictive capability, with AUCs of 0.864 and 0.832 in the training and testing cohorts (Table 4). The DCA of the nomogram also showed that because of the favorable prediction of HM when the threshold probability of a patient or doctor ranged from 10 to 90%, the nomogram added greater benefit than a treat-all or treat-none scheme (Figure 5).

Table 4.

Accuracy of predictive values between the training and testing cohorts

| Cohort | AUC | 95% CI | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | 0.864 | 0.817–0.916 | 0.817 | 0.805 | 0.808 |

| Testing | 0.832 | 0.763–0.901 | 0.686 | 0.798 | 0.773 |

AUC, area under the curve.

Figure 5.

For the decision curve, the y-axis represents the net benefit. This was calculated by expected benefit (gaining true positives) and subtracting expected harm (deleting false positives). The highest curve at any given threshold probability is the optimal prediction to maximize net benefit.

Discussion

This study aimed to incorporate enhanced CT features and clinical factors into a nomogram to help with predicting post-operative HM in patients with GAC. The nomogram comprised seven obtainable parameters (PEP, tumor location, AFP, CA125, CA724 levels, cT.stage and Arterial. CTV) demonstrating a high discriminative performance between HM and NM; three CT parameters-PEP, cT.stage and Arterial.CTV contributed to the prediction nomogram.DCA and calibration curves also revealed excellent model stability and benefits.

Previous studies have demonstrated the promise of CT-based nomograms as a non-invasive tool for the individualized prediction of GAC LN metastasis. 4–6 While it is generally considered that most GACs show moderate to marked enhancement in the early phase on contrast-enhanced CT, some authors 7 reported that the CT enhancement patterns of GACs were influenced by their histological components.

Xu et al’s studies have reported that primary tumor-based intravenous CT analysis provides valuable information for predicting occult peritoneal metastases in advanced GAC. 8 Liu et al CT-based T staging is an independent predictor to predict of occult peritoneal metastasis in advanced gastric cancer. 9 At the same time, they thought tiny lesions or microscopic metastases are not detectable, and those that emerge after surgery, i.e. metachronous hepatic metastases cannot be predicted. There are very few studies regarding the characteristics of CT enhancement to predict HM in patients with GAC. We found that when peak enhancement of the primary GAC occurred in the AP and the higher CT value in the arterial phase, it was more prone to HM. Tumors with high microvessel density often develop blood-borne metastases; the AP may thus exhibit early enhancement and higher malignancy, consistent with the results of Chen et al. 10 The enhancement of arterial stage GAC tumors depends on tumor blood vessels, while the formation and invasion of lymphatic vessels correlates with HM after radical GAC resection. 11 Additionally, the normalized iodine concentration value (NIC) of the AP and VP of energy spectrum CT iodine concentration is linearly and positively correlated with microvessel density. NIC-AP reflects the angiogenesis of relatively early and well-differentiated GAC, while NIC-VP reflects the angiogenesis of advanced and poorly differentiated GAC. 10 This type of HM occurred immediately after surgery, suggesting that early intensified GAC is highly aggressive. The path of HM in GAC may either follow the portal vein blood flow, or be caused by freely circulating tumor cells. From the perspective of efficacy, further trials on prognostic factors will benefit patients by subtype, which has guiding significance in promoting treatment decisions. 12

Our results confirm that the prognosis of GAC located in the cardia is poor and the proportion of HM after surgery is high. Xu Chang 13 designed a radiomic model for the differential diagnosis of esophagogastric junction (EGJ) adenocarcinoma at stages T3 and T4a. Li 14 showed that tumor sites, epidermal growth factor receptor, and HER-2 expression were all different, and had an impact on the survival rate of patients. Although the etiology of adenocarcinoma in EGJ is unclear, the prognosis of cardia adenocarcinoma is usually poor in the advanced stages. 15

We discovered that the higher the cT stage, the more likely HM is to subsequently occur. Our study also indicated that pre-operational cT stage, as well as pre-treatment AFP, CA125, and CA724 levels, were the key clinical risk factors statistically associated with the risk of HM. This was consistent with many other studies regarding HM that have been conducted for the prediction of early GAC recurrence after surgery. Imaging studies have suggested that clinical N staging, carbohydrate antigen 19–9 levels, carcinoembryonic antigen levels, and Borrmann classification were useful indicators for predicting early recurrence, 16 while a multicenter study 17 indicated that age, tumor size, tumor location, Lauren type, and pTNM stage classified according to the AJCC/UICC staging system were independent prognostic factors (all p < 0.001). In terms of tumor markers, when AFP, CA125, and CA724 levels are elevated, HM is more likely to occur after surgery. This is consistent with previous reports, 18 in which patients with HMs had higher serum AFP levels than those without HM, while about 72.7% of patients with GAC that exhibited elevated AFP levels had HMs.

Supported by the above study results, if the AP CT-enhancement of gastric cardia adenocarcinoma is the most obvious, cT stage is more higher and the levels of AFP, CA125, and CA724 tumor markers increase, prevention of HM should be performed immediately before or after gastrectomy through sex-based and individualized treatment strategies, such as perioperative chemotherapy. Because of improvement in advanced GAC’s response to chemotherapy and targeted therapy, as well as the implementation of some perioperative chemotherapy regimens, the role of surgery in patients with GAC should be examined. Picado et al 19 used survival analysis to compare gastrectomy plus perioperative chemotherapy with the aim of improving the survival rate of patients with GAC and HMs. Similarly, Smyth et al 20 believed that perioperative chemotherapy or adjuvant chemotherapy can improve the survival rate of patients with Stage IB cancer and above. The current surgical treatment model after perioperative chemotherapy provides a good prognosis for patients with GAC 19,21,22 ; however, most patients receive palliative chemotherapy for advanced GAC with HMs. Studies have shown that in patients with GAC after resection of a single HM, perioperative chemotherapy and other treatments can also improve the patient’s lifetime, 19,23,24 although prospective studies with large sample sizes are lacking to validate these results.

Our study had several limitations; first, to ensure the reliability of the CT value measurement in the ROI, 108/1040 patients were excluded because the primary tumor lesion was not visible or could not be adequately measured on CT. It is worth mentioning that the diagnosis of gastric cancer in these patients depends on gastroscopy and histopathological examination. 289/1040 patients were excluded because extrahepatic metastases or hepatic metastases combined with metastases in other sites. Exclusion of these patients may limit the clinical applicability of this model as in clinical practice hepatic metastases will commonly occur together with other extrahepatic disease sites. Further, the tumor areas consist of more enhanced mucosal layers and less enhanced muscle or serosal layers. If we only use the more enhanced parts, the measured value will be affected. Second, energy spectrum CT-enhanced cases were not screened, while the post-processing workstation will be used for measurement in the follow-up; parameters such as the iodine concentration in the lesion may demonstrate a higher combined predictive power. Finally, there were 11 patients developed metastases after >2 years. However, in patients with a very long interval, it is questionable whether risk-factors are really able to predict the occurrence of metastases already at baseline. Therefore, this model will thus only be applicable to a very selective group of patients.

We developed a nomogram that incorporates both CT imaging and clinical features to predict HM of GAC post-operatively, which may aid in the development of more effective therapeutic strategies for patients with GAC. In conclusion, the peak of the enhanced CT image and arterial phase CT value of the primary tumor, location of GAC, and increase in tumor markers levels and the cT stage indicate the possibility of HM developing after surgery. This predictive model—the basis of which is conducive for formulating a more appropriate treatment plan for the patient before surgery—thus provides new treatment strategies for patients with GAC who undergo perioperative chemotherapy and other treatments before surgery.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by grants of the Lanzhou University Second Hospital Second Hospital “Cuiying Technology Innovation Plan” Applied Basic Research Project (ID:CY2018-QN09,CY2021-ZD-01), Science and Technology Foundation for Young Scholars of Gansu Province (ID: 20JR5RA324) , Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (lzujbky-2021-kb32)

Patient consent: This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Lanzhou University and informed consent was waived.

Ethics approval: All procedures performed in the studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Contributor Information

Haiting Yang, Email: yht1503588@163.com.

Jianqing Sun, Email: sun_jianqing@126.com.

Hong Liu, Email: liu20190410@163.com.

Xianwang Liu, Email: 1553537867@qq.com.

Yingxia She, Email: 1582036634@qq.com.

Wenjuan Zhang, Email: hxzhangwj121@163.com.

Junlin Zhou, Email: lzuzjl601@163.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Verstegen MH, Harker M, van de Water C, van Dieren J, Hugen N, Nagtegaal ID, et al . Metastatic pattern in esophageal and gastric cancer: influenced by site and histology . World J Gastroenterol 2020. ; 26 : 6037 – 46 . doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i39.6037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kanda M, Mizuno A, Fujii T, Shimoyama Y, Yamada S, Tanaka C, et al . Tumor infiltrative pattern predicts sites of recurrence after curative gastrectomy for stages 2 and 3 gastric cancer . Ann Surg Oncol 2016. ; 23 : 1934 – 40 . doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5102-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hsu L-W, Huang K-H, Chen M-H, Fang W-L, Chao Y, Lo S-S, et al . Genetic alterations in gastric cancer patients according to sex . Aging (Albany NY) 2020. ; 13 : 376 – 88 . doi: 10.18632/aging.202142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang Y, Liu W, Yu Y, Liu J-J, Xue H-D, Qi Y-F, et al . Ct radiomics nomogram for the preoperative prediction of lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer . Eur Radiol 2020. ; 30 : 976 – 86 . doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06398-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feng Q-X, Liu C, Qi L, Sun S-W, Song Y, Yang G, et al . An intelligent clinical decision support system for preoperative prediction of lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer . J Am Coll Radiol 2019. ; 16 : 952 – 60 . doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yang Y-T, Dong S-Y, Zhao J, Wang W-T, Zeng M-S, Rao S-X . CT-detected extramural venous invasion is corelated with presence of lymph node metastasis and progression-free survival in gastric cancer . Br J Radiol 2020. ; 93 ( 1116 ): 20200673 . doi: 10.1259/bjr.20200673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tsurumaru D, Miyasaka M, Muraki T, Nishie A, Asayama Y, Oki E, et al . Histopathologic diversity of gastric cancers: relationship between enhancement pattern on dynamic contrast-enhanced CT and histological type . Eur J Radiol 2017. ; 97 : 90 – 95 . doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu Q, Sun Z, Li X, Ye C, Zhou C, Zhang L, et al . Advanced gastric cancer: CT radiomics prediction and early detection of downstaging with neoadjuvant chemotherapy . Eur Radiol 2021. ; 31 : 8765 – 74 . doi: 10.1007/s00330-021-07962-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu S, He J, Liu S, Ji C, Guan W, Chen L, et al . Radiomics analysis using contrast-enhanced CT for preoperative prediction of occult peritoneal metastasis in advanced gastric cancer . Eur Radiol 2020. ; 30 : 239 – 46 . doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06368-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen XH, Ren K, Liang P, Chai YR, Chen KS, Gao JB . Spectral computed tomography in advanced gastric cancer: can iodine concentration non-invasively assess angiogenesis? World J Gastroenterol 2017. ; 23 : 1666 – 75 . doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i9.1666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Komori M, Asayama Y, Fujita N, Hiraka K, Tsurumaru D, Kakeji Y, et al . Extent of arterial tumor enhancement measured with preoperative MDCT gastrography is a prognostic factor in advanced gastric cancer after curative resection . AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013. ; 201 : W253 – 61 . doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Qiu J-L, Deng M-G, Li W, Zou R-H, Li B-K, Zheng Y, et al . Hepatic resection for synchronous hepatic metastasis from gastric cancer . Eur J Surg Oncol 2013. ; 39 : 694 – 700 . doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2013.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang X, Guo X, Li X, Han X, Li X, Liu X, et al . Potential value of radiomics in the identification of stage T3 and T4a esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma based on contrast-enhanced CT images . Front Oncol 2021. ; 11 : 627947 . doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.627947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li G-C, Jia X-C, Zhao Q-C, Zhang H-W, Yang P, Xu L-L, et al . The expression of epidermal growth factor receptor 1 and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 based on tumor location affect survival in gastric cancer . Medicine (Baltimore) 2020. ; 99 ( 21 ): e20460 . doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abdi E, Latifi-Navid S, Zahri S, Yazdanbod A, Pourfarzi F . Risk factors predisposing to cardia gastric adenocarcinoma: insights and new perspectives . Cancer Med 2019. ; 8 : 6114 – 26 . doi: 10.1002/cam4.2497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang W, Fang M, Dong D, Wang X, Ke X, Zhang L, et al . Development and validation of a CT-based radiomic nomogram for preoperative prediction of early recurrence in advanced gastric cancer . Radiother Oncol 2020. ; 145 : 13 – 20 . doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fang C, Wang W, Deng J-Y, Sun Z, Seeruttun SR, Wang Z-N, et al . Proposal and validation of a modified staging system to improve the prognosis predictive performance of the 8th AJCC/UICC ptnm staging system for gastric adenocarcinoma: a multicenter study with external validation . Cancer Commun (Lond) 2018. ; 38 : 67 . doi: 10.1186/s40880-018-0337-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kinkel K, Lu Y, Both M, Warren RS, Thoeni RF . Detection of hepatic metastases from cancers of the gastrointestinal tract by using noninvasive imaging methods (US, CT, MR imaging, PET): a meta-analysis . Radiology 2002. ; 224 : 748 – 56 . doi: 10.1148/radiol.2243011362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Picado O, Dygert L, Macedo FI, Franceschi D, Sleeman D, Livingstone AS, et al . The role of surgical resection for stage IV gastric cancer with synchronous hepatic metastasis . J Surg Res 2018. ; 232 : 422 – 29 . doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.06.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van Grieken NC, Lordick F . Gastric cancer . Lancet 2020. ; 396 : 635 – 48 . doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31288-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tiberio GAM, Ministrini S, Gardini A, Marrelli D, Marchet A, Cipollari C, et al . Factors influencing survival after hepatectomy for metastases from gastric cancer . Eur J Surg Oncol 2016. ; 42 : 1229 – 35 . doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim MS, Lim JS, Hyung WJ, Lee YC, Rha SY, Keum KC, et al . Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by D2 gastrectomy in locally advanced gastric cancer . World J Gastroenterol 2015. ; 21 : 2711 – 18 . doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Markar SR, Mikhail S, Malietzis G, Athanasiou T, Mariette C, Sasako M, et al . Influence of surgical resection of hepatic metastases from gastric adenocarcinoma on long-term survival: systematic review and pooled analysis . Ann Surg 2016. ; 263 : 1092 – 1101 . doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schildberg CW, Croner R, Merkel S, Schellerer V, Müller V, Yedibela S, et al . Outcome of operative therapy of hepatic metastatic stomach carcinoma: a retrospective analysis . World J Surg 2012. ; 36 : 872 – 78 . doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1492-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]