Abstract

Objectives:

Cleft lip with/without cleft palate and cleft palate only are congenital birth defects where the upper lip and/or palate fail to fuse properly during embryonic facial development. Affecting ~1.2/1000 live births world-wide, these orofacial clefts impose significant social and financial burdens on affected individuals and their families. Orofacial clefts have a complex etiology resulting from genetic variants combined with environmental covariates. Recent genome-wide association studies and whole-exome sequencing for orofacial clefts identified significant genetic associations and variants in several genes. Of these, we investigated the role of common/rare variants in SHH, RORA, MRPL53, ACVR1, and GDF11.

Materials and Methods:

We sequenced these five genes in 1255 multi-ethnic cleft lip with/without palate and cleft palate only samples in order to find variants that may provide potential explanations for the missing heritability of orofacial clefts. Rare and novel variants were further analyzed using in-silico predictive tools.

Results:

19 total variants of interest were found, with variant types including stop-gain, missense, synonymous, intronic, and splice-site variants. Of these, 3 novel missense variants were found, one in SHH, one in RORA, and one in GDF11.

Conclusion:

This study provides evidence that variants in SHH, RORA, MRPL53, ACVR1, and GDF11 may contribute to risk of orofacial clefts in various populations.

Keywords: Candidate Gene, Craniofacial Genetics, Genome-Wide Association Studies, Whole Exome Sequencing, Congenital Birth Defect, Novel Variants

INTRODUCTION:

Orofacial clefts (OFCs) are congenital birth defects where the independently derived facial primordia that form the orofacial complex fail to fuse properly and completely during embryonic development. OFCs are the most common craniofacial birth defect in humans with an average worldwide prevalence of 1.2/1000 live births (Rahimov, Jugessur, & Murray, 2012), though individual population incidence can vary. The highest prevalence for OFC has been reported in Asia and the lowest in Africa (Mossey & Modell, 2012), and the difference in prevalence across the world suggests that the relative impact of specific susceptibility genes may vary between different populations (Gowans et al., 2016).

While there are several treatments available for OFCs, which include corrective surgery, speech therapy, dental care, and mental health support (Berk & Marazita, 2002); access and affordability of these services imposes significant social and financial burdens on affected individuals and their families. Additionally, OFCs can result in early life complications such as trouble eating, breathing, and higher prevalence of ear infections (Nackashi, Dedlow, & Dixon-Wood, 2002). All of these increase child mortality risk, especially in areas that lack access to care.

OFCs can be categorized into two groups: Nonsyndromic, which is clefting that occurs in isolation with no other visible structural defects, and syndromic, which is clefting that is consistently seen with other birth abnormalities. Approximately 70% of OFCs fall into the nonsyndromic category. The etiology of nonsyndromic OFCs is complex and results from a combination of genetic variants and environmental covariates (Dixon, Marazita, Beaty, & Murray, 2011). Genetically, nonsyndromic OFCs tend to veer away from clear Mendelian inheritance patterns. Environmental risk factors include maternal smoking, alcohol consumption, and insufficient intake of folates and other vitamins and minerals during gestation, particularly during the first trimester of pregnancy.

Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and whole-exome sequencing (WES) identified significant genetic associations and rare variants for OFCs (Beaty et al., 2010; Birnbaum et al., 2009; Butali et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2017). In prior studies, we previously identified rare variants in GWAS identified candidate genes (Butali et al., 2014). In this study, we investigated the role of rare variants in Sonic Hedgehog (SHH), RAR Related Orphan Receptor A (RORA), and Activin Receptor Type-1 (ACVR1) as identified in our African only GWAS (Butali et al., 2019). In addition, we investigated Mitochondrial Ribosomal Protein L53 (MRPL53), which was identified using an expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) approach, and Growth Differentiation Factor 11 (GDF11), which was identified following WES. All these genes were screened for rare variants in individuals with cleft lip with or without cleft palate (CL/P) and cleft palate only (CPO) from multiple populations (namely Nigeria, Ethiopia, Ghana, Puerto Rico, Iowa, and the Philippines).

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

DNA Collection and Processing:

A total of 1255 samples were included in this study from participants in Nigeria, Ethiopia, Ghana, Puerto Rico, Iowa, and the Philippines (Supplementary Table 1). Local Institutional Review Board approvals (Iowa approval number: 201101720, Lagos University Teaching Hospital Idi‐Araba, Lagos IRB approval number: ADM/DCST/HREC/VOL.XV/321, Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital Ile‐Ife IRB approval number: ERC/2011/12/01, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology IRB approval number: CHRPE/RC/018/13, the Addis Ababa University IRB approval number: 003/10/surg, the University of Puerto‐Rico IRB approval number: 0640111, and Iowa approval number: 199804080 in conjunction with Philippines approval number: 199804081) and informed consent were obtained from all participants prior to sample and data collection. Saliva and swab samples were collected using OG-500 Oragene-DNA Collection Kits (http://www.dnagenotek.com) from case individuals with OFCs, their family members, and control individuals. Case families were recruited by surgeons at cleft clinics and during surgical missions. Controls were defined as individuals born alive without any congenital birth defects and were recruited at immunization and dental clinics. Following collection, samples were transported to the Butali laboratory at the University of Iowa for DNA extraction and processing. DNA was extracted from saliva and swab samples using Qiagen DNA Extraction Kits. Concentration of DNA samples were then quantified using Qubit Assays and the Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (http://www.invitrogen.com/site/us/en/home/brands/Product-Brand/Qubit.html). XY genotyping was also done as a quality control measure to validate matching of sample sex to clinical records from collection.

Primer Design:

Forward and reverse primers were designed using Primer3 v.0.4.0 (Rozen & Skaletsky, 2000) to encompass the coding regions of the candidate genes of interest. Primer uniqueness was checked using UCSC BLAT (Kent, 2002). Primers were then optimized and confirmed using gel electrophoresis. Further details can be found in prior studies (Liu et al., 2017). The primers used in the PCR and annealing temperatures are available upon request from Butali Laboratory.

Coding Region Amplification:

Coding regions of the genes of interest were amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using 4 ng/µl DNA samples. Amplification product quality was assessed with gel electrophoresis. Successfully amplified products were then sent to Functional Biosciences, Madison, Wisconsin (http://order.functionalbio.com/seq/index) to undergo Sanger sequencing via ABI 3730XL (http://www.appliedbiosystems.com/absite/us/en/home.html). Resulting chromatograms were imputed into PHRED software where trace files were read, base calls were made, and quality values were assigned to each base call (http://www.phrap.org/phredphrapconsed.html). Chromatograms were then assembled, scanned, and visualized with PHRAP (http://www.phrap.org/), POLYPHRED (http://droog.gs.washington.edu/polyphred/), and CONSED (http://www.phrap.org/consed/consed.html) respectively.

Variant Calling:

Coding regions of sequenced samples were visualized and called using the software CONSED. Genomic location of each variant was found through imputing CONSED data into the UCSC Genome Browser BLAT (Kent, 2002). Effects of coding variants on protein function were predicted using Polymorphism Phenotyping v2 (POLYPHEN-2) (Adzhubei et al., 2010), Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant (SIFT) (Sim et al., 2012), Protein Variation Effect Analyzer (PROVEAN) (Choi & Chan, 2015), Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) (McLaren et al., 2016), and Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) (Rentzsch, Witten, Cooper, Shendure, & Kircher, 2019). Have Your Protein Explained (HOPE) (Venselaar, Te Beek, Kuipers, Hekkelman, & Vriend, 2010) was used to analyze and visualize the structural effects and changes point variants had on subsequent protein function. Possible variant effects on splicing were also predicted using Human Splice Finder 3.1 (Desmet et al., 2009).

Variants were cross-referenced with those in publicly available databases: 1000 Genomes (Auton et al., 2015), Exome Aggregation Consortium (K. J. Karczewski et al., 2017), GnomAD (Konrad J. Karczewski et al., 2020), and Exome Variant Server (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/). Through these databases, we were able to ascertain the novelty and frequency of the variants found. Variants that lacked a reference number and had not been previously reported in the aforementioned databases or in the literature were described as novel. Identified variants with low minor allele frequencies (MAF) were described as “very rare” if the MAF was less than 1% of the general population, and were described as “rare” if the MAF was less than 5% but greater than or equal to 1% of that of the general population. These variants, (novel, very rare, and rare), if found, were confirmed through reverse sequencing of the samples.

Segregation Analysis:

Segregation analysis was done in order to determine if the variants found were de Novo or had a maternal or paternal inheritance pattern. Proband samples with variants of interest and corresponding familial samples were sequenced and compared.

SysFACE Craniofacial Gene Expression and Enrichment Analysis:

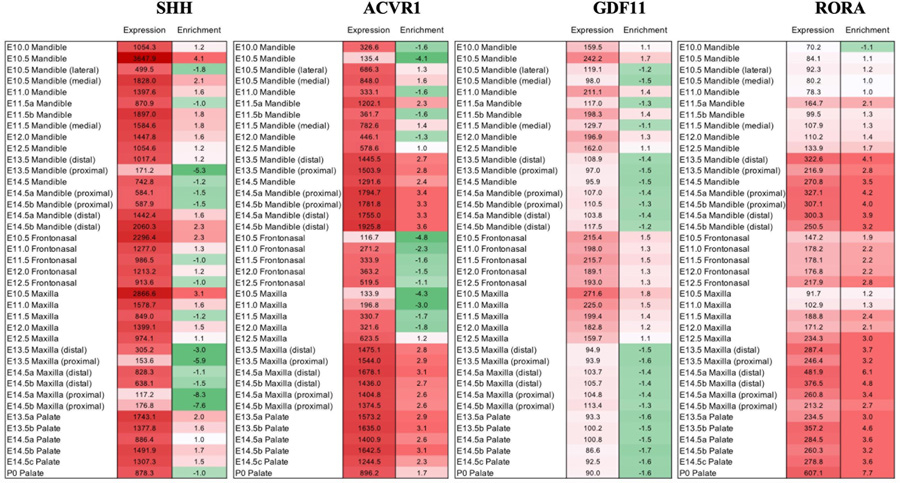

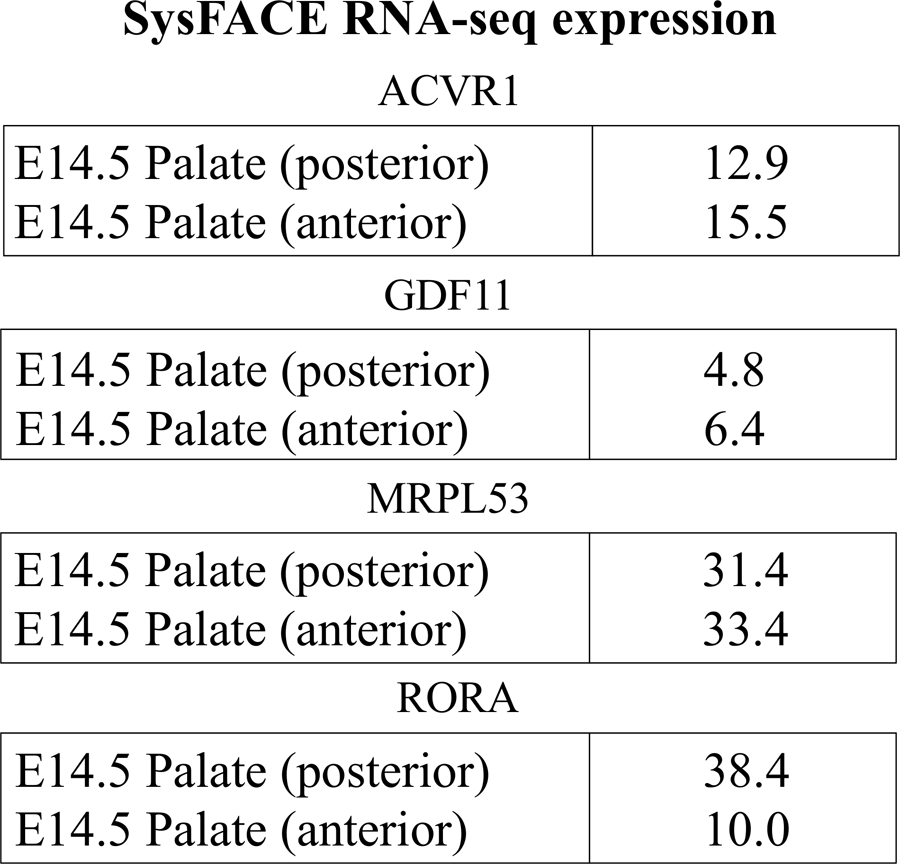

Following GWAS, to prioritize genes based on their expression in craniofacial tissues, we used a bioinformatics resource tool called SysFACE. SysFACE-based analysis has been successfully used for examining craniofacial expression of genes previously linked to orofacial clefting (Butali et al., 2014; Butali et al., 2019; L. L. Cox et al., 2018; T. C. Cox et al., 2019). Briefly, SysFACE uses transcriptomics data on specific craniofacial tissues at embryonic (E) or postnatal (P) stages. Microarray expression profiles of candidate genes were analyzed from previously generated mouse mandible, frontonasal, maxilla and palate datasets (FaceBase datasets: FB00000107, FB00000254, FB00000264, FB00000467.01, FB00000468.01, FB00000474.01, FB00000477.01, FB00000905, FB00000926, FB00000934, FB00000935; NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets: GSE22989, GSE31004, GSE35091, GSE7759, GSE11400, GSE31004). In addition to expression, comparative analysis for candidate genes was performed for estimating craniofacial tissue-enriched expression for microarray datasets. Namely, craniofacial-tissue specific microarray data was compared with mouse whole embryo body (WB) tissue microarray data at E10.5, E11.5, and E12.5 (GSE32334), termed “WB in silico subtraction”, as previously described (Kakrana et al., 2018; Lachke et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2017). Expression in RNA-seq data from E14.5 anterior and posterior oral palate were obtained from FaceBase (FB00000765.01, FB00000767.01).

RESULTS:

In total, we found 19 variants of interest that may affect function of the protein based on bioinformatics predictions. These include: six in SHH, one in RORA, three in MRPL53, six in ACVR1, and two in GDF11. We could not ascertain if the novel variants were de Novo or segregated in the family due to non-availability of samples from one of the parents or sometimes none of the parents (Table 1).

Table 1.

SHH Variants in CPO/CL/P Samples

| Part A: Variants Observed | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghana, Ethiopia, and Nigeria | |||||||||||

| New/Known | Cleft Type | HGVS | HGVp | Type | Ghana | Ethiopia | Nigeria | 1KG | EVS | ExAC | GenomeAD |

| rs4716913 | CPO | NA | p.Pro10Pro | Synonymous | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.015/0.004 | 0 | 0 | 0.014/0.001 |

| rs551809680 | CPO | c.1181G>A | p.Arg394His | Missense | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.0023/0.0006 | 0 | 0 | 0.00303/3.944e-05 |

| Novel | CLP | c.338T>C | p.Val113Ala | Missense | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| rs4716913 | CLP | NA | p.Pro10Pro | Synonymous | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.015/0.004 | 0 | 0 | 0.014/0.001 |

| Puerto Rico | |||||||||||

| New/Known | Cleft Type | HGVS | HGVp | Type | # of Individuals | 1KG | EVS | ExAC | GenomeAD | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| rs908886937 | CLP | c.874G>A | p.Gly292Arg | Missense | 1 | - | 0 | 0 | 0.00014656/2.09529e-05 | ||

| rs553158506 | CPO | c.376C>G | p.Arg126Gly | Missense | 1 | - | 0 | 0 | 4.067e-05/2.665e-05 | ||

| rs9333633 | CL | c.570G>A | p.Ser190Ser | Synonymous | 2 | 0.005/0.005 | 0 | 0 | 0.003/0.005 | ||

| Part B: Predicted Effects of Variants | |||||||||||

| Ghana, Ethiopia, and Nigeria | |||||||||||

| New/Known | Cleft Type | HGVS | HGVp | Polyphen-2 | SIFT | Provean Score | CADD | Human Splice Finder | Segregation Analyses | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| rs4716913 | CPO | NA | p.Pro10Pro | NA | NA | NA | NA | Alteration of an exonic ESE site. Creation of an exonic ESS site. Potential alteration of splicing. |

NA | ||

| rs551809680 | CPO | c.1181G>A | p.Arg394His | Benign | Tolerated | Neutral | 21 | NA | NA | ||

| Novel | CLP | c.338T>C | p.Val113Ala | Probably Damaging | Deleterious | Damaging | 21.4 | NA | Parent Samples Unavailable | ||

| rs4716913 | CLP | NA | p.Pro10Pro | NA | NA | NA | NA | Alteration of an exonic ESE site. Creation of an exonic ESS site. Potential alteration of splicing. | NA | ||

| Puerto Rico | |||||||||||

| New/Known | Cleft Type | HGVS | HGVp | Polyphen-2 | SIFT | Provean Score | CADD | Human Splice Finder | Segregation Analyses | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| rs908886937 | CLP | c.874G>A | p.Gly292Arg | Benign | Tolerated | NA | 10.33 | NA | Absent in Father | ||

| rs553158506 | CPO | c.376C>G | p.Arg126Gly | Benign | Deleterious Low Confidence | NA | 0.267 | NA | Absent in Father | ||

| rs9333633 | CL | c.570G>A | p.Ser190Ser | NA | NA | NA | 12.54 | Alteration of an exonic ESE site. Potential alteration of splicing. | Absent in Mother | ||

All analyses were based on genome assembly number GRCh38/hg38, 2017 (http://genome.icsc.edu).

1KG: 1000 Genomes; EVS: Exome Variant Server; ExAC: Exome Aggregation Consortium; GenomeAD: Genome Aggregation Database; CADD: Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion; ESE: Exonic Splicing Enhancer; ESS: Exonic Splicing Silencer; NA: Not Applicable

SHH:

In sequencing the SHH gene, four missense variants of interest (Table 1) were found (p.Arg394His, p.Val113Ala, p.Gly292Arg, p.Arg126Gly). Among these variants, one was a novel missense variant (p.Val113Ala) in an individual from Ghana with CLP. p.Val113Ala was predicted to be “Probably Damaging” and “Deleterious” by Polyphen-2 and SIFT and had a CADD score of 24.6, meaning it is in the top 1% of deleterious variants in the human genome. We also found two silent variants (p.Pro10Pro and p.Ser190Ser) that potentially alter splicing. p.Pro10Pro was found in both CPO and CLP samples. HOPE analysis of the novel variant p.Val113Ala in SHH predicted that there could be an empty space in the core leading to disturbances in domain structure. Additionally, the decrease in amino acid size from Valine to Alanine may also affect protein interactions with surrounding molecules. Segregation analysis could not be done on p.Val113Ala as parent samples were not available.

RORA:

In sequencing the protein-coding region of the RORA gene, we found a novel missense variant (Table 2) in an individual from Ghana with CLP (p.Gly4Val). SIFT predicted this variant to be “Damaging”, while CADD assigned a score of 16.31, meaning it is in the top 10% of deleterious variants in the human genome. The amino acid change is in a conserved region between monkeys and humans. HOPE analysis of the RORA variant p.Gly4Val showed an increase in amino acid size and hydrophilicity compared to the wild type. As Glycine is the most flexible amino acid, the change to Valine resulted in an increase in rigidity, which may affect protein interactions and function. Additionally, p.Gly4Val segregated in the family and was found in an unaffected sibling in addition to the proband, indicating incomplete penetrance of the cleft phenotype in this family.

Table 2.

RORA Variants in CPO/CL/P Samples

| Part A: Variants Observed | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghana, Ethiopia, and Nigeria | |||||||||||

| New/Known | Cleft Type | HGVS | HGVp | Type | Ghana | Ethiopia | Nigeria | 1KG | EVS | ExAC | GenomeAD |

| Novel | CLP | c.11G>T | p.Gly4Val | Missense | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Part B: Predicted Effects of Variants | |||||||||||

| Ghana, Ethiopia, and Nigeria | |||||||||||

| New/Known | Cleft Type | HGVS | HGVp | Polyphen-2 | SIFT | Provean Score | CADD | Human Splice Finder | Segregation Analyses | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| Novel | CLP | c.11G>T | p.Gly4Val | Benign | Deleterious | NA | 16.31 | NA | Present in Unaffected Sibling | ||

All analyses were based on genome assembly number GRCh38/hg38, 2017 (http://genome.icsc.edu).

1KG: 1000 Genomes; EVS: Exome Variant Server; ExAC: Exome Aggregation Consortium; GenomeAD: Genome Aggregation Database; CADD: Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion; ESE: Exonic Splicing Enhancer; ESS: Exonic Splicing Silencer; NA: Not Applicable

MRPL53:

In MRPL53, three very rare missense variants (Table 3) were found (p.Thr45Ser, p.Arg73Cys, and p.Ser92Pro). p.Thr45Ser and p.Ser92Pro had CADD scores above 20, meaning they are in the top 1% of deleterious variants in the human genome. Additionally, p.Arg73Cys was found in two unrelated samples and had a CADD score of 32, indicating that it is in the top 0.1% of deleterious variants in the human genome. The p.Thr45Ser was predicted to be “Tolerated” and “Benign”. However, this variant is still of interest in further studies due to the conservative nature of these prediction tools. All three variants have a low minor allele frequency of less than 0.01. HOPE analyses of these variants predicted that the change from Threonine to Serine in p.Thr45Ser would show a decrease in amino acid size that may affect protein interactions with surrounding molecules. The change from Arginine to Cysteine in p.Arg73Cys results in a loss of hydrogen bonds and an increase in hydrophobicity, which may distort structure and result in loss of interactions. Lastly, the change from Serine to Proline in p.Ser92Pro was predicted to exhibit an increase in hydrophobicity, which may affect protein interactions with surrounding molecules. Additionally, as Proline is a helix breaker, the amino acid change showed disruption in the alpha-helix secondary structure.

Table 3.

MRPL53 Variants in CPO/CL/P Samples

| Part A: Variants Observed | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New/Known | Cleft Type | HGVS | HGVp | Type | Population | # of Individuals | 1KG | EVS | ExAC | GenomeAD |

| rs751976686 | CL | c.133A>T | p.Thr45Ser | Missense | Ethiopia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.182e-05/7.98473e-06 |

| rs202083153 | CLP | c.216C>A | p.Arg73Cys | Missense | Puerto Rico | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.78938e-05/1.19594e-05 |

| rs574615587 | CLP | c.274T>C | p.Ser92Pro | Missense | Puerto Rico | 1 | 0.005/0.00019968 | 0 | 0 | 2.89285e-05/7.97684e-06 |

| Part B: Predicted Effects of Variants | ||||||||||

| New/Known | Cleft Type | HGVS | HGVp | Polyphen-2 | SIFT | Provean Score | CADD | Human Splice Finder | Segregation Analyses | |

|

| ||||||||||

| rs751976686 | CL | c.133A>T | p.Thr45Ser | Benign | Tolerated | NA | 22.4 | NA | Present in Mother, no paternal sample | |

| rs202083153 | CLP | c.216C>A | p.Arg73Cys | Probably Damaging | Deleterious | NA | 32 | NA | Absent in Both Separate Fathers | |

| rs574615587 | CLP | c.274T>C | p.Ser92Pro | Possibly Damaging | Deleterious | NA | 22.4 | NA | Absent in Father | |

All analyses were based on genome assembly number GRCh38/hg38, 2017 (http://genome.icsc.edu).

1KG: 1000 Genomes; EVS: Exome Variant Server; ExAC: Exome Aggregation Consortium; GenomeAD: Genome Aggregation Database; CADD: Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion; ESE: Exonic Splicing Enhancer; ESS: Exonic Splicing Silencer; NA: Not Applicable

ACVR1:

Three missense variants of interest (Table 4) were found in sequencing ACVR1 (p.Pro465Leu, p.Ala15Gly, and p.Glu49Lys). All three missense variants had CADD scores above 20, meaning they are in the top 1% of deleterious variants in the human genome. p.Pro465Leu was predicted to be “Possibly Damaging” by Polyphen-2 and “Tolerated” by SIFT. Provean score independently predicted p.Pro465Leu to be “Damaging”, with a separate SIFT prediction of “Deleterious”. p.Ala15Gly was predicted to be “Deleterious with low confidence” by SIFT. We also found two silent variants (p.Leu505Leu and p.Pro465Pro), and one intronic variant (rs12105152) in the CPO samples that were predicted by ESF to “Most probably” and “Potentially” alter splicing. HOPE analyses of these variants predicted that the change from Proline to Leucine in p.Pro465Leu results in an amino acid size increase that may affect interactions with surrounding molecules due to being located on the protein surface. Additionally, Prolines are rigid, so the change to Leucine may disturb backbone conformation. HOPE analysis of p.Ala15Gly predicted that, since Glycine is the smallest and most flexible amino acid, this increase in flexibility and decrease in size may result in loss of interactions with surrounding molecules. Additionally, there is a loss of hydrophobic interactions in the core or surface of the protein. p.Ala15Gly also occurs within a signal peptide important for protein recognition and mature protein cleavage, thus signal peptide recognition may be affected. Since the “Benign” and “Tolerated” predictions by Polyphen-2 and SIFT; respectively, contradict the high (top 1% deleterious variant) CADD score in both variants, this discrepancy will be further investigated in future functional studies.

Table 4.

ACVR1 Variants in CPO/CL/P Samples

| Part A: Variants Observed | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghana, Ethiopia, and Nigeria | |||||||||||

| New/Known | Cleft Type | HGVS | HGVp | Type | Ghana | Ethiopia | Nigeria | 1KG | EVS | ExAC | GenomeAD |

| rs750457181 | CLP | c.1394C>T | p.Pro465Leu | Missense | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000/7.16013e-05 |

| rs13406336 | CLP | c.44C>G | p.Ala15Gly | Missense | 0 | 2 | 0 | -/0.0074 | 0 | 0 | 0.0007842/0.01053 |

| rs1219953789 | CLP | c.145G>A | p.Glu49Lys | Missense | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000/7.95988e-06 |

| rs12105152 | CPO | NA | NA | Intron | 13 | 0 | 5 | 0.043/0.012 | 0 | 0 | 0.042/0.003 |

| rs3738927 | CPO | NA | p.Leu505Leu | Synonymous | 23 | 3 | 8 | 0.085/0.026 | 0 | 0 | 0.062/0.006 |

| rs373855918 | CPO | NA | p.Pro465Pro | Synonymous | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000/7.95646e-06 |

| Part B: Predicted Effects of Variants | |||||||||||

| Ghana, Ethiopia, and Nigeria | |||||||||||

| New/Known | Cleft Type | HGVS | HGVp | Polyphen-2 | SIFT | Provean Score | CADD | Human Splice Finder | Segregation Analyses | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| rs750457181 | CLP | c.1394C>T | p.Pro465Leu | Possibly Damaging | Tolerated/Deleterious | Damaging | 24.3 | NA | Absent in Parents | ||

| rs13406336 | CLP | c.44C>G | p.Ala15Gly | Benign | Deleterious Low Confidence | Neutral | 22.6 | NA | NA | ||

| rs1219953789 | CLP | c.145G>A | p.Glu49Lys | Benign | Tolerated | Neutral | 22.9 | NA | Absent in unaffected sibling, parent samples NA | ||

| rs12105152 | CPO | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.323 | Alteration of the WT donor site, most probably affecting splicing. | NA | ||

| rs3738927 | CPO | NA | p.Leu505Leu | NA | NA | NA | 20.7 | Alteration of an exonic ESE site. Potential alteration of splicing. | NA | ||

| rs373855918 | CPO | NA | p.Pro465Pro | NA | NA | NA | 13.7 | Alteration of the WT donor site, most probably affecting splicing. | NA | ||

All analyses were based on genome assembly number GRCh38/hg38, 2017 (http://genome.icsc.edu).

1KG: 1000 Genomes; EVS: Exome Variant Server; ExAC: Exome Aggregation Consortium; GenomeAD: Genome Aggregation Database; CADD: Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion; ESE: Exonic Splicing Enhancer; ESS: Exonic Splicing Silencer; NA: Not Applicable

GDF11:

In sequencing GDF11 (Table 5), we found one novel missense variant of interest (p.Lys337Glu) and one stop-gain variant (p.Arg214Ter). Both variants had CADD scores above 20 meaning they are in the top 1% of deleterious variants in the human genome. HOPE analysis was conducted on the novel missense and stop-gain variants (p.Lys337Glu and p.Arg214Ter) found in GDF11. The change from Lysine to Glutamic acid resulted in a decrease in size and a change in charge from positive to negative. The change in size and charge may result in disruption of interactions with surrounding molecules and a decrease in molecular binding ability. As the wild-type Lysine is present in the PISA-database and is involved in a multimer contact, HOPE predicted that Lysine is normally contacting surrounding proteins. With the change to Glutamic acid, the smaller amino acid may be too small to maintain Lysine’s original multimer contacts. The wild-type lysine is also highly conserved in this position, while Glutamic acid does not appear in this position in homologous proteins. Additionally, the presence of the wild-type Lysine is important for protein stability because it forms part of a cysteine bridge. The change to Glutamic acid results in loss of the cysteine bond and can lead to severe consequences regarding protein structure and stability. In segregation analyses, the variant p.Lys338Glu was segregated from the mother and was found in an unaffected male twin. For the stop-gain variant, p.Arg214Ter, HOPE analysis could not be done as a premature stop variant does not result in an amino acid change.

Table 5.

GDF11 Variants in CPO/CL/P Samples

| Part A: Variants Observed | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghana, Ethiopia, and Nigeria | |||||||||||

| New/Known | Cleft Type | HGVS | HGVp | Type | Ghana | Ethiopia | Nigeria | 1KG | EVS | ExAC | GenomeAD |

| Novel | CL | c.1009A>G | p.Lys337Glu | Missense | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| rs780604190 | CLP | c.640G>T | p.Arg214Ter | Stop-Gained | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/3.985e-06 |

| Part B: Predicted Effects of Variants | |||||||||||

| Ghana, Ethiopia, and Nigeria | |||||||||||

| New/Known | Cleft Type | HGVS | HGVp | Polyphen-2 | SIFT | Provean Score | CADD | Human Splice Finder | Segregation Analyses | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| Novel | CL | c.1009A>G | p.Lys337Glu | Benign | Tolerated | Neutral | 23.7 | NA | Absent in mother, present in unaffected male twin | ||

| rs780604190 | CLP | c.640G>T | p.Arg214Ter | Benign | Tolerated | Neutral | 22.4 | NA | Present in mother, absent in maternal grandmother | ||

All analyses were based on genome assembly number GRCh38/hg38, 2017 (http://genome.icsc.edu).

1KG: 1000 Genomes; EVS: Exome Variant Server; ExAC: Exome Aggregation Consortium; GenomeAD: Genome Aggregation Database; CADD: Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion; ESE: Exonic Splicing Enhancer;

ESS: Exonic Splicing Silencer; NA: Not Applicable

SysFACE Analysis

SysFACE analyses based on microarray data showed that mouse orthologs of ACVR1, GDF11, RORA, and SHH exhibit high expression and enriched expression in multiple craniofacial tissues (Figure 1). Additionally, RNA-seq data showed that MRPL53 is expressed in the anterior and posterior palate of E14.5 mice (Figure 2). Previous expression analyses also supported GDF11 expression in craniofacial tissues (T. C. Cox et al., 2019).

Figure 1.

SysFACE-based microarray analysis of candidate gene expression in mouse craniofacial (CF) tissue To gain insight into their spatiotemporal expression dynamics, SysFACE (Systems tool for craniofacial expression-based gene discovery) was used to analyze expression and enriched-expression (enrichment) of candidate genes in various craniofacial (CF) tissues, namely, mandible, maxilla, frontonasal and palate at embryonic (E) and post-natal (P) stages. eQTL is a bioinformatics tool that is used to provide information on the impact of a SNP within a regulation region on the expression the nearby genes in relevant tissues. Whereas SYSFACE is a tool that is used to predict relevant candidate genes following discovery omics studies (GWAS, WES and WGS) for clefts based on the expression and enrichment levels of these genes in relevant structures. SysFACE-based microarray expression analysis is presented for the genes SHH, ACVR1, GDF11 and RORA. For “expression”, numbers represent fluorescence intensity units for normalized tissue-specific expression. For “enrichment”, numbers represent fold-change indicating enrichment in specific CF tissue compared to mouse whole embryo body reference dataset in an approach termed in-silico subtraction (please see Methods for details). SHH, ACVR1, GDF11 and RORA are expressed and enriched in several CF tissues at multiple stages in mouse development.

Figure 2.

SysFACE-based analysis using RNA-sequencing data of candidate gene expression in craniofacial (CF) tissue. SysFACE analysis based on RNA-sequencing data demonstrates that ACVR1, GDF11, MRPL533 and RORA are expressed in mouse posterior and anterior palate at embryonic (E) stage E14.5. Expression is indicated by numbers which represent fragments per kilobase of transcripts per million mapped reads (FPKM). The datasets used in this analysis are described in Methods.

DISCUSSION:

The genes sequenced in this study were chosen to be of interest due to having been previously reported in GWAS and WES. Also, SysFACE-based analysis showed that these candidate genes were robustly expressed in multiple craniofacial tissues in mouse development. Additionally, gnomAD provided low observed and expected (O/E) ratios. Since low O/E ratios signify that the gene is mutating at a lower rate than expected, and thus any variants found in such genes are pathogenic, this contributed to our interesting in evaluating these genes for disease causing variants.

We sequenced genes that have been previously reported in GWAS and WES and found three novel variants; p.Val113Ala reported in SHH, p.Gly4Val in RORA, and p.Lys337Glu in GDF11. Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) is a protein coding gene that regulates growth and patterning in early embryonic stages (McMahon, Ingham, & Tabin, 2003). Additionally, it is a mitogen and promotes cell proliferation in many embryonic and adult tissues (Jiang & Hui, 2008). SHH is expressed in the epithelium of the teeth, tongue papillae, and palatal rugae (Sagai et al., 2017), with expression in the oral epithelium occurring at the onset of palatal outgrowth (Rice, Connor, & Rice, 2006). SHH signaling provides inductive signals critical for the developmental patterning of the brain and face and is essential for craniofacial development in vertebrates. Additionally, in studies of human and animal model systems, interference with this pathway has been reported to cause birth defects; among the most well-studied of which fall within the holoprosencephaly (HPE) spectrum (Lipinski et al., 2010).

RAR (retinoic acid receptor) related orphan receptor A (RORA) is a member of the nuclear hormone receptors (NR 1). It controls the expression of several genes by binding to the hormone response elements within the promoters of those genes. These genes are involved in organ development, lipid metabolism, tumor metastasis, and circadian rhythm. RORA regulates expression of SHH, which has been well documented to be involved in organogenesis and has been implicated in many studies to be associated with OFCs in many populations. This gene also regulates genes involved in photoreceptor development and skeletal muscle development (Lau, Bailey, Dowhan, & Muscat, 1999), and is required for proper cerebellum development (Guissart et al., 2018). Additionally, RORA modulates the expression of Sulfotransferase 2A1 (SULT2A1) during lipid, steroid, and xenobiotic metabolism in the liver (Genoux et al., 2005; Giguère et al., 1994; Harding, Atkins, Jaffe, Seo, & Lazar, 1997; Lind et al., 2005). SULT2A1 was reported to be associated with CPO in our previous GWAS wherein it was shown that SULT2A1 played an important role and was expressed in palatal development in mice during embryonic development (Butali et al., 2019). While experiments showing gene-gene interactions regarding lip and palate development have yet to be reported, gene functions and their interactions in other organs are strongly suggestive. Specifically, in the liver, RORA regulates the expression of SULT2A1 to carry out lipid metabolic function. RORA has also been associated with syndromic intellectual disability (Guissart et al., 2018). RORA was identified as a top candidate gene through meta-analysis of nonsyndromic CL/P in Europeans, which revealed a genome-wide significant locus at chromosome 15q22.2 (Ludwig et al., 2012). This locus maps to a regulatory region containing both strong enhancer and promoter signatures, and multiple transcription factor-binding sites, as predicted by ENCODE.

We found p.Thr45Ser, p.Arg73Cys, and p.Ser92Pro in MRPL53. Segregation analyses of this variant shows that it was inherited from the mother. Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L53 (MRPL53) is a gene that encodes part of the large subunit of the mitochondrial ribosome. High expression levels of this gene are found in the tongue, trachea, throat, and skeletal muscles (Petryszak et al., 2016). This gene was identified to be associated with OFCs through eQTL analysis. It was observed that orbicularis oris muscle samples from cases with clefts exhibited different expression levels compared to controls. These expression levels were correlated with the genotypes of what was identified as the cis-eQTLs of this gene. Variants in this gene were also identified in samples with OFCs (Masotti et al., 2018). Studies have shown that MRPL53 interacts with MYC which is a transcription factor with a role in facial development (Agrawal, Yu, Salomon, & Sedivy, 2010). The mitochondria are the energy machinery of the cell and enzymes are required for the synthesis of ATP. These enzymes are synthesized within the mitochondria; thus, the disruption of their synthesis would have a huge impact on ATP production and many active cell processes such as cell growth, differentiation, and migration (Sylvester, Fischel-Ghodsian, Mougey, & O’Brien, 2004). These active processes have been well documented to be the mechanism through which OFCs develop. Coding variants of this gene have been associated with OFCs in previous studies in the Brazilian population (Masotti et al., 2018).

We found p.Pro465Leu, p.Ala15Gly, and p.Glu49Lys in ACVR1. This variant also matches a previously described variant (dbSNP:rs13406336) on ExPASy annotated as being of “polymorphism” severity. In addition, the change from Glutamic acid to Lysine in p.Glu49Lys had a change in charge from negative to positive, which may result in repulsion with surrounding molecules. Lastly, the increase in amino acid size from Glutamic acid to Lysine may result in bumps. Activin Receptor Type-1 (ACVR1) is a gene that encodes activin receptor type-1 protein, which is a member of the bone morphogenic protein (BMP) type I receptor family. The BMP signaling pathway is important because it plays a major role in craniofacial morphogenesis during embryonic development (Noda, Mishina, & Komatsu, 2016). Constitutively active ACVR1 expression of BMP signaling has been shown to have major effects on correct tissue responses in palatogenic signaling, such as impediments by the epithelial tissue on the fusion of the palatal mesenchyme and muscles of the hard and soft palates respectively (Noda et al., 2016; Reynolds et al., 2019). Additionally, neural crest-specific disruption of ACVR1 has also been found to result in craniofacial defects like lack of frontal bone squamous region ossification with cleft palate and a hypomorphic mandible (Mishina & Snider, 2014). In contrast to overexpression, the conditional deletion of BMP signaling receptor ACVR1 in neural crest cells can also result in craniofacial abnormalities (Dudas, Sridurongrit, Nagy, Okazaki, & Kaartinen, 2004).

Growth Differentiation Factor 11 (GDF11) is a protein coding gene in the TGF-β family that secretes signals important for positional identity determination along the anterior/posterior axis during development (Walker et al., 2017). GDF11 has previously been reported as a pivotal regulator during embryonic palatal formation, with homozygous knock-out mice showing a variety of anomalies including impaired palatal development (Bult, Blake, Smith, Kadin, & Richardson, 2019). GDF11 plays a major role in craniofacial development (Lee & Lee, 2015).

The rare coding variants found in this study and their subsequent analysis strongly suggest a role for these candidate genes in the etiology of OFC. Therefore, it is important to screen for rare coding variants in omics identified candidate genes in order to identify the missing heritability that cannot be explained by common variants.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the families who voluntarily participated in this study in Puerto Rico, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Ghana, Iowa, and the Philippines. We are also grateful to all the administrative and research staff, students, nurses and resident doctors who assisted with participant recruitment, consent, and data collection. We appreciate the contribution of our late colleague, Muhammad Musa who designed and sequenced the ACVR1 gene in multiple populations. This research is supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (R00 DE022378 and R01DE028300; A.B., R00 DE024571; C.B., R03 DE024776; S.A.L.) and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (S21 MD001830; C.B., U54 MD007587; C.B.).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS: None to declare.

REFERENCES:

- Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, . . . Sunyaev SR (2010). A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods, 7(4), 248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal P, Yu K, Salomon AR, & Sedivy JM (2010). Proteomic profiling of Myc-associated proteins. Cell Cycle, 9(24), 4908–4921. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.24.14199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auton A, Abecasis GR, Altshuler DM, Durbin RM, Abecasis GR, Bentley DR, . . . National Eye Institute, N. I. H. (2015). A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature, 526(7571), 68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaty TH, Murray JC, Marazita ML, Munger RG, Ruczinski I, Hetmanski JB, . . . Scott AF (2010). A genome-wide association study of cleft lip with and without cleft palate identifies risk variants near MAFB and ABCA4. Nat Genet, 42(6), 525–529. doi: 10.1038/ng.580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk NW, & Marazita ML (2002). Costs of cleft lip and palate: personal and societal implications. In Cleft lip and palate: from origin to treatment (pp. 458–467): Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum S, Ludwig KU, Reutter H, Herms S, Steffens M, Rubini M, . . . Mangold E (2009). Key susceptibility locus for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate on chromosome 8q24. Nat Genet, 41(4), 473–477. doi: 10.1038/ng.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bult CJ, Blake JA, Smith CL, Kadin JA, & Richardson JE (2019). Mouse Genome Database (MGD) 2019. Nucleic Acids Res, 47(D1), D801–d806. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butali A, Mossey P, Adeyemo W, Eshete M, Gaines L, Braimah R, . . . Murray J (2014). Rare functional variants in genome-wide association identified candidate genes for nonsyndromic clefts in the African population. Am J Med Genet A, 164a(10), 2567–2571. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butali A, Mossey PA, Adeyemo WL, Eshete MA, Gowans LJJ, Busch TD, . . . Adeyemo AA (2019). Genomic analyses in African populations identify novel risk loci for cleft palate. Hum Mol Genet, 28(6), 1038–1051. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, & Chan AP (2015). PROVEAN web server: a tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatics, 31(16), 2745–2747. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LL, Cox TC, Moreno Uribe LM, Zhu Y, Richter CT, Nidey N, . . . Roscioli T (2018). Mutations in the Epithelial Cadherin-p120-Catenin Complex Cause Mendelian Non-Syndromic Cleft Lip with or without Cleft Palate. Am J Hum Genet, 102(6), 1143–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox TC, Lidral AC, McCoy JC, Liu H, Cox LL, Zhu Y, . . . Roscioli T (2019). Mutations in GDF11 and the extracellular antagonist, Follistatin, as a likely cause of Mendelian forms of orofacial clefting in humans. Hum Mutat, 40(10), 1813–1825. doi: 10.1002/humu.23793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmet FO, Hamroun D, Lalande M, Collod-Béroud G, Claustres M, & Béroud C (2009). Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res, 37(9), e67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MJ, Marazita ML, Beaty TH, & Murray JC (2011). Cleft lip and palate: understanding genetic and environmental influences. Nat Rev Genet, 12(3), 167–178. doi: 10.1038/nrg2933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudas M, Sridurongrit S, Nagy A, Okazaki K, & Kaartinen V (2004). Craniofacial defects in mice lacking BMP type I receptor Alk2 in neural crest cells. Mech Dev, 121(2), 173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2003.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genoux A, Dehondt H, Helleboid-Chapman A, Duhem C, Hum DW, Martin G, . . . Fruchart JC (2005). Transcriptional regulation of apolipoprotein A5 gene expression by the nuclear receptor RORalpha. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 25(6), 1186–1192. doi: 10.1161/01.Atv.0000163841.85333.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giguère V, Tini M, Flock G, Ong E, Evans RM, & Otulakowski G (1994). Isoform-specific amino-terminal domains dictate DNA-binding properties of ROR alpha, a novel family of orphan hormone nuclear receptors. Genes Dev, 8(5), 538–553. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.5.538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowans LJ, Adeyemo WL, Eshete M, Mossey PA, Busch T, Aregbesola B, . . . Butali A (2016). Association Studies and Direct DNA Sequencing Implicate Genetic Susceptibility Loci in the Etiology of Nonsyndromic Orofacial Clefts in Sub-Saharan African Populations. J Dent Res, 95(11), 1245–1256. doi: 10.1177/0022034516657003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guissart C, Latypova X, Rollier P, Khan TN, Stamberger H, McWalter K, . . . Küry S (2018). Dual Molecular Effects of Dominant RORA Mutations Cause Two Variants of Syndromic Intellectual Disability with Either Autism or Cerebellar Ataxia. Am J Hum Genet, 102(5), 744–759. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.02.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Atkins GB, Jaffe AB, Seo WJ, & Lazar MA (1997). Transcriptional activation and repression by RORalpha, an orphan nuclear receptor required for cerebellar development. Mol Endocrinol, 11(11), 1737–1746. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.11.0002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, & Hui CC (2008). Hedgehog signaling in development and cancer. Dev Cell, 15(6), 801–812. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakrana A, Yang A, Anand D, Djordjevic D, Ramachandruni D, Singh A, . . . Lachke SA (2018). iSyTE 2.0: a database for expression-based gene discovery in the eye. Nucleic Acids Res, 46(D1), D875–d885. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, Cummings BB, Alföldi J, Wang Q, . . . Genome Aggregation Database, C. (2020). The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature, 581(7809), 434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karczewski KJ, Weisburd B, Thomas B, Solomonson M, Ruderfer DM, Kavanagh D, . . . MacArthur DG (2017). The ExAC browser: displaying reference data information from over 60 000 exomes. Nucleic Acids Res, 45(D1), D840–d845. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ (2002). BLAT--the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res, 12(4), 656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachke SA, Ho JW, Kryukov GV, O’Connell DJ, Aboukhalil A, Bulyk ML, . . . Maas RL (2012). iSyTE: integrated Systems Tool for Eye gene discovery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 53(3), 1617–1627. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau P, Bailey P, Dowhan DH, & Muscat GE (1999). Exogenous expression of a dominant negative RORalpha1 vector in muscle cells impairs differentiation: RORalpha1 directly interacts with p300 and myoD. Nucleic Acids Res, 27(2), 411–420. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YS, & Lee SJ (2015). Roles of GASP-1 and GDF-11 in Dental and Craniofacial Development. J Oral Med Pain, 40(3), 110–114. doi: 10.14476/jomp.2015.40.3.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind U, Nilsson T, McPheat J, Strömstedt PE, Bamberg K, Balendran C, & Kang D (2005). Identification of the human ApoAV gene as a novel RORalpha target gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 330(1), 233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski RJ, Song C, Sulik KK, Everson JL, Gipp JJ, Yan D, . . . Rowland IJ (2010). Cleft lip and palate results from Hedgehog signaling antagonism in the mouse: Phenotypic characterization and clinical implications. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol, 88(4), 232–240. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Busch T, Eliason S, Anand D, Bullard S, Gowans LJJ, . . . Butali A (2017). Exome sequencing provides additional evidence for the involvement of ARHGAP29 in Mendelian orofacial clefting and extends the phenotypic spectrum to isolated cleft palate. Birth Defects Res, 109(1), 27–37. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig KU, Mangold E, Herms S, Nowak S, Reutter H, Paul A, . . . Nöthen, M. M. (2012). Genome-wide meta-analyses of nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate identify six new risk loci. Nat Genet, 44(9), 968–971. doi: 10.1038/ng.2360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masotti C, Brito LA, Nica AC, Ludwig KU, Nunes K, Savastano CP, . . . Passos-Bueno MR (2018). MRPL53, a New Candidate Gene for Orofacial Clefting, Identified Using an eQTL Approach. J Dent Res, 97(1), 33–40. doi: 10.1177/0022034517735805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren W, Gil L, Hunt SE, Riat HS, Ritchie GR, Thormann A, . . . Cunningham F (2016). The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol, 17(1), 122. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0974-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon AP, Ingham PW, & Tabin CJ (2003). Developmental roles and clinical significance of hedgehog signaling. Curr Top Dev Biol, 53, 1–114. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(03)53002-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishina Y, & Snider TN (2014). Neural crest cell signaling pathways critical to cranial bone development and pathology. Exp Cell Res, 325(2), 138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossey PA, & Modell B (2012). Epidemiology of oral clefts 2012: an international perspective. Front Oral Biol, 16, 1–18. doi: 10.1159/000337464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nackashi JA, Dedlow ER, & Dixon-Wood V (2002). Health care for children with cleft lip and palate: comprehensive services and infant feeding. Cleft lip and palate: from origin to treatment, 127–158.

- Noda K, Mishina Y, & Komatsu Y (2016). Constitutively active mutation of ACVR1 in oral epithelium causes submucous cleft palate in mice. Dev Biol, 415(2), 306–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petryszak R, Keays M, Tang YA, Fonseca NA, Barrera E, Burdett T, . . . Brazma A (2016). Expression Atlas update--an integrated database of gene and protein expression in humans, animals and plants. Nucleic Acids Res, 44(D1), D746–752. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimov F, Jugessur A, & Murray JC (2012). Genetics of nonsyndromic orofacial clefts. Cleft Palate Craniofac J, 49(1), 73–91. doi: 10.1597/10-178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentzsch P, Witten D, Cooper GM, Shendure J, & Kircher M (2019). CADD: predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res, 47(D1), D886–d894. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds K, Kumari P, Sepulveda Rincon L, Gu R, Ji Y, Kumar S, & Zhou CJ (2019). Wnt signaling in orofacial clefts: crosstalk, pathogenesis and models. Dis Model Mech, 12(2). doi: 10.1242/dmm.037051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice R, Connor E, & Rice DP (2006). Expression patterns of Hedgehog signalling pathway members during mouse palate development. Gene Expr Patterns, 6(2), 206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen S, & Skaletsky H (2000). Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol, 132, 365–386. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagai T, Amano T, Maeno A, Kiyonari H, Seo H, Cho SW, & Shiroishi T (2017). SHH signaling directed by two oral epithelium-specific enhancers controls tooth and oral development. Sci Rep, 7(1), 13004. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12532-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim N-L, Kumar P, Hu J, Henikoff S, Schneider G, & Ng PC (2012). SIFT web server: predicting effects of amino acid substitutions on proteins. Nucleic Acids Research, 40(W1), W452–W457. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester JE, Fischel-Ghodsian N, Mougey EB, & O’Brien TW (2004). Mitochondrial ribosomal proteins: candidate genes for mitochondrial disease. Genet Med, 6(2), 73–80. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000117333.21213.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venselaar H, Te Beek TA, Kuipers RK, Hekkelman ML, & Vriend G (2010). Protein structure analysis of mutations causing inheritable diseases. An e-Science approach with life scientist friendly interfaces. BMC Bioinformatics, 11, 548. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker RG, Czepnik M, Goebel EJ, McCoy JC, Vujic A, Cho M, . . . Thompson TB (2017). Structural basis for potency differences between GDF8 and GDF11. BMC Biol, 15(1), 19. doi: 10.1186/s12915-017-0350-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Zuo X, He M, Gao J, Fu Y, Qin C, . . . Bian Z (2017). Genome-wide analyses of non-syndromic cleft lip with palate identify 14 novel loci and genetic heterogeneity. Nat Commun, 8, 14364. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.