Abstract

This study presents the development and evaluation of a high flow rate gelatin cascade impactor (GCI) to collect different PM particle sizes on water-soluble gelatin substrates. The GCI operates at a flow rate of 100 lpm, and consists of two impaction stages, followed by a filter holder to separate particles in the following diameter ranges: >2.5 μm, 0.2–2.5 μm, and <0.2 μm. Laboratory characterization of the GCI performance was conducted using monodisperse polystyrene latex (PSL) particles as well as polydisperse ammonium sulfate, sodium chloride, and ammonium nitrate aerosols to obtain the particle collection efficiency curves for both impaction stages. In addition to the laboratory characterization, we performed concurrent field experiments to collect PM2.5 employing both GCI equipped with gelatin filter and personal cascade impactor sampler (PCIS) equipped with PTFE filter for further toxicological analysis using macrophage-based reactive oxygen species (ROS) and dithiothreitol consumption (DTT) assays. Our results showed that the experimentally determined cut-point diameters for the first and second impaction stages were 2.4 μm and 0.21 μm, respectively, which agreed with the theoretical predictions. Although the GCI has been developed primarily to collect particles on gelatin filters, the use of a different type of substrate (i.e., quartz) led to similar particle separation characteristics. The findings of the field tests demonstrated the advantage of using the GCI in toxicological studies due to its ability to collect considerable PM-toxic constituents, as corroborated by the DTT and ROS values for the GCI-collected particles which were 26.44 nmoles/min/mg PM and 8813.2 μg Zymosan Units/mg PM, respectively. These redox activity values were more than twice those of particles collected concurrently on PTFE filter using the PCIS. This high-flow-rate impactor can collect considerable amounts of size-fractionated PM on water-soluble filters (i.e., gelatin), which can completely dissolve in water allowing for the extraction of soluble and insoluble PM species for further toxicological analysis.

Keywords: Particulate matter, Inertial impaction, Cascade impactor, Gelatin filter, Oxidative potential, Ultrafine particles

1. Introduction

Particulate matter (PM) is considered one of the main contributing factors to adverse health effects in humans, including respiratory diseases, lung cancer, neurotoxicity, and cardiovascular illnesses (Anderson et al., 2012; Gauderman et al., 2015; Nelin et al., 2012; Polichetti et al., 2009; Y. Wang et al., 2017). These health effects are associated with human exposure to ambient PM (Clifford et al., 2018) and can be evaluated by epidemiological and toxicological studies using aerosols that represent real-life ambient PM (Schwarze et al., 2006; Valavanidis et al., 2008). Given the complexity of the physicochemical characteristics of real-life ambient PM, it is very challenging to generate similar aerosols in the lab for chemical and toxicological analyses (Jacoby et al., 2011; Krieger et al., 2012). Therefore, collecting real-life PM directly from the ambient air is essential for numerous applications, including health assessment studies.

The collection of ambient aerosols with different particle sizes is accomplished by various inertial impaction technologies (Chen et al., 2018; H. Wang et al., 2017). Low-flow-rate inertial impactors were used in various air sampling applications; however, they do not usually collect sufficient PM loadings for particle characterization and toxicological analysis because of their low operational flow rates (Patel et al., 2021). On the other hand, high-flow-rate impactors can shorten the sampling duration and collect considerable amounts of PM-targeted constituents existing in the atmosphere (Patel et al., 2021; Sugita et al., 2019). Aerosol concentrators, such as versatile aerosol concentration enrichment system (VACES), have also been developed to enrich ambient PM concentration for conducting inhalation studies (Kim et al., 2000, 2001; Ning et al., 2006), however they impose several challenges. For instance, the operation of these concentrators is complex as it requires multiple processes in series, including saturation, condensation, and impaction (Kim et al., 2001). In addition, employing the concentrators in exposure studies can lead to inevitable instability in PM physical and chemical characteristics because of the variability of concentration and chemical composition of ambient PM (Taghvaee et al., 2019). While aerosol concentrators have been widely used for the collection of ambient PM, employing high-flow-rate inertial impactors leads to a simpler setup with a lower cost (Kavouras et al., 2000; Misra et al., 2002).

Previous publications used inertial impactors to collect ambient particles on various types of substrates, including PTFE (Teflon) and quartz filters (Biswas & Gupta, 2017; George et al., 2012). The collected particles on these different substrates are usually extracted in a particular solvent (e.g., ultrapure Milli-Q water) using a sonication device in order to generate liquid solutions for PM characterization or using them in exposure studies (Varga et al., 2001). However, the efficiency of extracting the collected particles in Milli-Q water is often much lower than 100% due to the insolubility of some particles, making it difficult to extract all the collected particles in the sample (Huang et al., 2020; Taghvaee et al., 2019). Some of these water-insoluble species (e.g., transition metals and organics such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH)) are particularly toxic components of the ambient aerosol and their exclusion compromises the integrity of toxicological studies (Gerlofs-Nijland et al., 2009). To overcome this challenge, the use of water-soluble particle collection media such as filters and impaction substrates is highly desired since these substrates will completely dissolve in water (i.e., 100% extraction efficiency), allowing for the extraction of all possible particles, including water-insoluble fractions. As an example, gelatin filters are one of the commercially available water-soluble filters and have been widely used for collecting airborne microbes and viruses (i.e., bioaerosol sampling) since they can efficiently maintain microorganisms (Appert et al., 2012; Chan et al., 2020; Fabian et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2020; Scherwing & Patzelt, 2020). However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have developed a high-flow-rate cascade impactor for collecting multi-sized ambient PM (i.e., coarse, accumulation, and ultrafine particles) on gelatin filters to use in toxicological studies.

The main objective of this study was to develop and evaluate a high-flow-rate gelatin cascade impactor (GCI) for the collection of different ambient PM fractions on gelatin substrates and filters. The performance of GCI was evaluated using laboratory-generated aerosols as well as in field experiments to collect ambient PM for further toxicological studies. The GCI operates at a high flow rate (100 lpm) and is designed to separate ambient particles into three groups: coarse (> 2.5 μm), accumulation (0.2 – 2.5 μm), and ultrafine particles (< 0.2 μm). The development of the GCI offers a simple and powerful tool for numerous applications requiring PM aqueous solutions, including toxicity assays and inhalation studies. In addition, the use of water-soluble gelatin substrates permits the complete extraction of water-insoluble species, which provides a better understanding of the toxicological properties of the collected PM samples. Using gelatin filters in field sampling experiments is simpler, cheaper, and more efficient in terms of PM slurry preparations in comparison with conventional filters (e.g., PTFE and quartz) that pose considerable difficulties in extracting the collected particles into aqueous solutions (Huang et al., 2020; Taghvaee et al., 2019).

2. Methods

2.1. Gelatin cascade impactor design

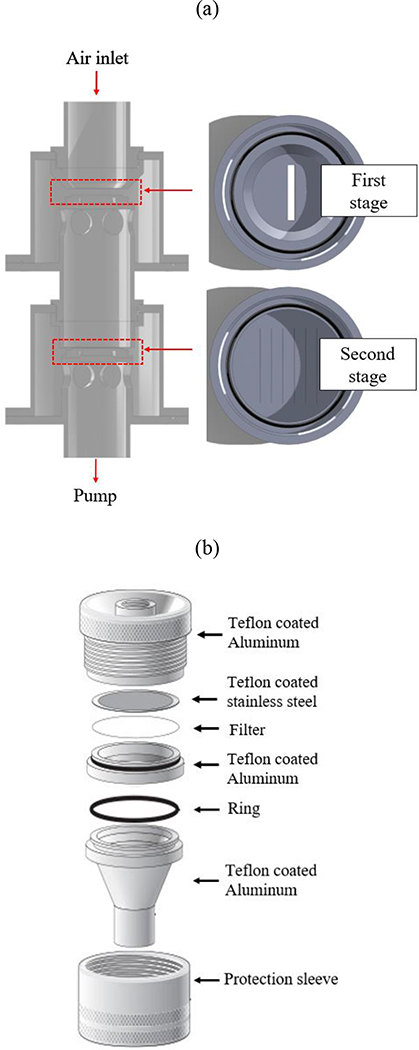

The gelatin cascade impactor (shown in Figure 1) consists of two sequential impaction stages along with a filter holder placed downstream of the impactor and is operated at flow rate of 100 lpm. Gelatin filters with diameters of 47 mm and 80 mm (3.0 μm pore size, Sartorius AG, Germany) were used as particle collection media in the two impaction stages and the after-filter stage, respectively. The detailed specifications of the GCI are expressed in Table 1 which presents the design parameters and the physical characteristics of the impactor based on the theoretical calculations. As presented in Table 1, the critical cut-point diameters (d50) for the first and second impaction stages of GCI were 2.5 μm and 0.2 μm, respectively. They were determined first theoretically for each impaction stage based on the critical Stokes number and then confirmed in laboratory experiments as discussed later in section 3.1.1. Following the same procedure, the pressure drop values were determined theoretically as 1 in H2O (0.25 kPa) and 12 in H2O (2.98 kPa) for the first and second impaction stages, respectively, and then were verified experimentally. Furthermore, the first impaction stage was designed with one slit nozzle having width and length of 0.33 cm and 2.48 cm, respectively, while the second stage was designed with 6 equally spaced slit nozzles having equal width (0.013 cm) and length (3.12 cm).

Figure 1.

The (a) two impaction stages and the (b) filter holder of the gelatin cascade impactor

Table 1.

The physical characteristics and design parameters of the gelatin cascade impactor

| First stage | Second stage | After-filter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate material | Gelatin filter | Gelatin filter | Gelatin filter |

| Substrate diameter (mm) | 47 | 47 | 80 |

| Critical Stokes number St50 | 0.25 | 0.25 | - |

| √St50 | 0.5 | 0.5 | - |

| Cut-point d50 (μm) | 2.50 | 0.20 | - |

| △P (kPa) | 0.25 | 2.98 | - |

| Jet velocity Uj (cm/s) | 2021 | 7001 | - |

| Flow rate (lpm) | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Slit nozzle width W (cm) | 0.33 | 0.013 | - |

| Slit nozzle length (cm) | 2.48 | 3.12 | - |

| Number of slit nozzles | 1 | 6 | - |

2.2. Impaction theory

Inertial impaction theory has been widely used for the development of air particulate capturing technologies (e.g., cascade impactors) (Gotoh & Masuda, 2000; Maeng et al., 2007; Marple et al., 1990a) and was used for the development of the GCI in this study. We employed the following Stokes equation for designing the cut-point diameter and nozzle dimensions of impactor stages based on the Stokes number of a particle having a 50% impaction probability (St50) (Marple et al., 1990b, 1991; Sioutas, Koutrakis, & Olson, 1994):

| (1) |

where ρp is the particle density (g/cm3), Uj is the average velocity of the jet (cm/s), μ is the dynamic viscosity of the air (g/(cm.s)), dp is the particle diameter (cm), W is the nozzle width (cm), and Cc is Cunningham slip correction factor, which was estimated using equation 2 (Hinds, 1999):

| (2) |

where λ is the mean free path of air molecules (cm).

Moreover, the jet velocities for both impaction stages in Table 1 were calculated by dividing the GCI flow rate by the nozzle cross-sectional area. The theoretical pressure drop across each impactor stage was calculated based on the following Bernoulli’s equation:

| (3) |

where ΔP is the pressure drop (dyn/cm2) and the density of air (ρa) is equal to 0.0012 g/cm3.

2.3. Laboratory characterization of the first and second impaction stages of the GCI

2.3.1. Experimental setup

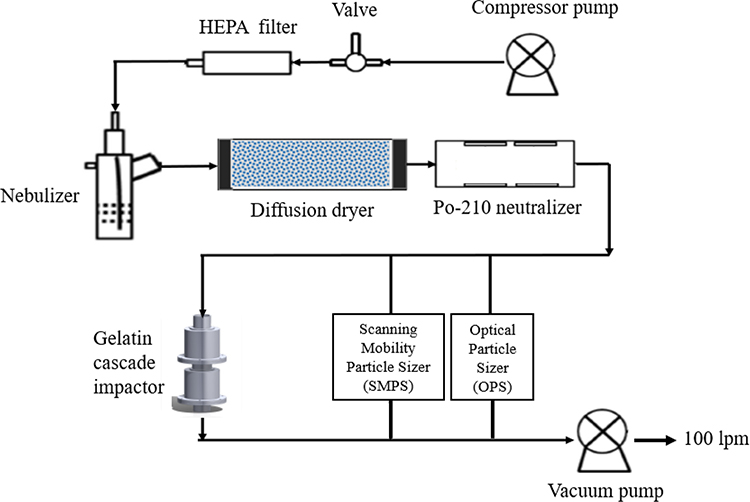

Monodisperse polystyrene latex (PSL) particles along with three different polydisperse aerosols (i.e., sodium chloride (NaCl), ammonium sulfate ((NH4)2SO4), and ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3)) were used to determine the particle collection efficiency for each stage of the gelatin cascade impactor. These monodisperse and polydisperse particles were generated in the lab by aerosolizing their aqueous solution using a nebulization system (Figure 2) (Han et al., 2009; Lim et al., 2020; Soo et al., 2016). Figure 2 illustrates the schematic of the experimental setup used for the characterization of impaction stages of the GCI. At first, the liquid suspensions were converted to airborne aerosols by supplying compressed filtered air to a nebulizer (Model 11310 HOPE™ nebulizer, B&B Medical Technologies, USA) using a compressor pump (Model VP0625-V1014-P2-0511, Medo Inc., USA) equipped with HEPA capsule (Model 12144, Pall Corporation, USA). The aerosolized particles were drawn to a silica-gel diffusion dryer (Model 3062, TSI Inc., USA) to remove the moisture of particles, followed by a glass container having Po-210 neutralizers (Model 2U500, NRD Inc., USA) to minimize the electrical charges of particles. The airborne particles entered the GCI operating with a flow rate of 100 lpm using a high-capacity pump (Model 0523-101-G588NDX, Gast Manufacturing Inc., USA).

Figure 2.

Experimental setup schematic for the laboratory characterization of the gelatin cascade impactor

Particle collection efficiency (1 – particle penetration) was determined as a function of particle size using an optical particle sizer (OPS) (Model 3330, TSI Inc., USA) and a scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS) (Model 3936, TSI Inc., USA). Since the GCI was designed to allow for decoupling of the first impaction stage from the second stage, we individually characterized each stage to obtain the particle collection efficiency curves using the experimental setup shown in Figure 2. Given that the OPS and SMPS mainly detect particles in size range of 0.3 to 10 μm and 0.01 to 0.7 μm, respectively, we characterized the first impaction stage using the OPS only while the second impaction stage was characterized using both instruments simultaneously (i.e., OPS and SMPS). As shown in the experimental setup schematic, both particle counter instruments were connected upstream and downstream of the impaction stage to measure the difference in particle number concentrations before and after the impactor. Equation 4 was used for calculating the collection efficiency of particles for each impaction stage:

| (4) |

where CE is the particle collection efficiency and PNu and PNd are particle number concentrations upstream and downstream of the impactor, respectively. Additionally, the pressure was also experimentally measured upstream and downstream of each impaction stage using Magnehelic pressure gauge (Model series 2000, Dwyer Instruments Inc., USA) to calculate the pressure drop as a function of the air flow rate.

2.3.2. Mass loading tests

In addition to the laboratory characterization of GCI described above, the performance of GCI equipped with gelatin filter was compared with a personal cascade impactor sampler (PCIS) (Model 225–370, SKC Inc., USA) equipped with PTFE (Teflon) filter (Pall Life Sciences Inc., USA). We performed laboratory experiments employing both impactors in parallel to collect artificially generated test aerosols (i.e., sodium chloride, ammonium nitrate, and glutaric acid) and then calculate the mass concentrations (μg/m3) of the collected particles. For each test aerosol, the experiments were carried out to compare the particle mass concentrations measured by the GCI first and second impaction stages with those determined by the PCIS 2.5 μm and 0.25 μm cut-point stages, respectively. Prior to the above-mentioned laboratory tests, all filters and substrates were kept in a room with a controlled temperature of 22 – 24 °C and relative humidity of 40 – 50% to equilibrate and then were weighed before and after the experiments using Mettler 5 microbalance (MT5, Mettler Toledo Inc., USA) to determine the collected mass from the difference between their final and initial weights.

2.4. Analysis of blank gelatin filters

2.4.1. Chemical and toxicological analyses

Blank gelatin and PTFE filters having equal size (47 mm) were analyzed in the Wisconsin State Lab of Hygiene (WSLH) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The blank filters were analyzed for their inorganic ions, metals, and trace elements. The inorganic ions were assessed using ion chromatography (IC), while the metals and trace elements were measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS) (Karthikeyan & Balasubramanian, 2006; Lough et al., 2005). Furthermore, the redox activity of the filters was assessed by means of the macrophage-based reactive oxygen species (ROS) and dithiothreitol consumption (DTT) assays. At first, aqueous solutions of the filters were prepared using Type 1 ultrapure Milli-Q water (resistivity 18.2 MΩ·cm at 25 °C, total organic carbon (TOC) ≤ 5 ppb) for the use in both assays. ROS assay was performed by exposing highly responsive rat alveolar macrophage cells to the liquid solution and using dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) as the fluorescent probe to assess the ROS activity. DCFH-DA was employed in ROS assay since it is responsive to main radioactive oxygen species, including hydroxyl, peroxide, and superoxide radicals (Carranza & Pantano, 2003; Schoonen et al., 2006). More details related to ROS assay are described in Landreman et al. (2008). Furthermore, the DTT assay has been widely used for measuring the redox activity of PM samples (Delfino et al., 2013; Kumagai & Shimojo, 2002; Shima et al., 2006). This assay measures the DTT consumption in the filter extract and its conversion to the disulfide form, in which the linear rate of DTT depletion is proportional to the oxidative potential (toxicity) of the analyzed sample. Further details regarding the DTT assay can be found in Kumagai et al. (2002) and Shafer et al. (2016).

2.4.2. Particle number concentrations

A blank gelatin filter with an average mass of 63.20 mg was dissolved in 220 ml of ultrapure Milli-Q water using an ultrasonic bath for 30 min to form a homogenous solution with a concentration of approximately 287 μg/ml. The blank gelatin slurry was analyzed for the particle number concentrations using the nebulization system setup described previously, in which the slurry was aerosolized and then drawn through the SMPS inlet port to measure the number-based size distribution. For the purpose of comparison, we collected ambient ultrafine PM (UFP) on PTFE filter (20 × 25 cm, 2.0 μm pore size, PALL Life Sciences, USA) using a high-flow-rate PM sampler that has a cut-point diameter of 0.18 μm to separate accumulation from ultrafine PM (Misra et al., 2002). The collected particles were extracted in an ultrapure Milli-Q water to form a liquid suspension having a concentration of 275 μg/ml (i.e., similar to the concentration of the blank gelatin suspension) that was re-aerosolized using the previously discussed nebulization system.

2.5. Field evaluation of gelatin cascade impactor

In addition to the laboratory characterization of the GCI, field tests were conducted using GCI and PCIS equipped with gelatin and PTFE filters, respectively. The field location was near the University of Southern California (USC) main campus in downtown Los Angeles, CA, and in close proximity to a major highway (I-110). This location site has been extensively used in previous publications since it represents a mixture of various urban sources emitting PM in different sizes and chemical compositions (Moore et al., 2007; Ning et al., 2007; Sardar et al., 2005). The aerosol samplers (i.e., GCI and PCIS) were placed in a controlled indoor environment (i.e., a sampling unit) and connected to the outdoor environment using an aluminum tube to sample ambient air, which will equilibrate to room temperature once it enters the controlled indoor space. It should be noted that placing the GCI in an outdoor environment to conduct field experiments might be problematic, especially in fall and winter seasons, because the higher relative humidity prevailing during these periods might compromise the quality of the gelatin substrates. Before initiating these field experiments, the PTFE and gelatin filters were kept in a standard laboratory condition (i.e., temperature of 22 – 24 °C and relative humidity of 40 – 50%) to equilibrate and then obtain their pre-sampling weights. After sampling, the filters were weighed to calculate the collected mass on each filter from the difference between the post-sampling and the pre-sampling weights.

Prior to starting the field sampling, we conducted a series of field tests to assess the durability of gelatin filters in withstanding long-term sampling durations. These field experiments were carried out with different sampling durations (e.g., 1 day, 2 days, 5 days) to collect ambient particles on gelatin substrates using the GCI. We realized that exceeding 24-hr of sampling resulted in damaging the gelatin filters as they were torn apart and separated into smaller pieces. Therefore, we performed short-term sampling (24 hr) to compare the oxidative potential of PM2.5 (dp < 2.5 μm) samples using the GCI and the PCIS simultaneously. For the collection of PM2.5, we employed the GCI first impaction stage and the PCIS 2.5 μm cut-point stage and placed an 80 mm gelatin filter and a 37 mm PTFE filter in their after-filter stages, respectively. Given that the PCIS operates at low flow rate (i.e., 9 lpm), we used two PCIS simultaneously on each sampling day to allow for the collection of sufficient PM mass loadings (> 300 μg) on two PTFE filters, which were composed together to form a slurry for the toxicological analysis. The mass loading was not an issue in GCI since it was operating at flow rate of 100 lpm, allowing for an average collection of more than 2 mg of PM2.5 each day. After concluding five daily field experiments, the collected samples were sent to Wisconsin state lab of hygiene to measure the redox activity of particles using DTT and ROS assays.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Laboratory experiments using artificially generated test aerosols

3.1.1. Pressure drop and collection efficiency curves

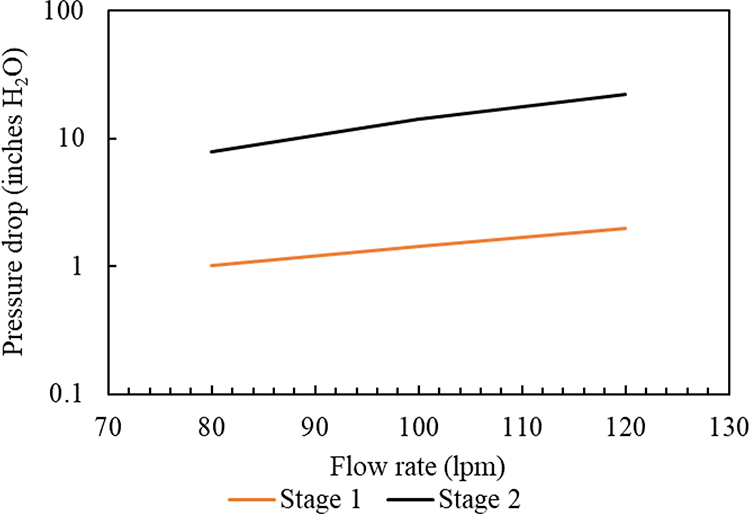

Using the experimental setup discussed earlier, the pressure drop was measured for both impaction stages and plotted as a function of GCI air flow rate as shown in Figure 3. By operating the GCI at a flow rate of 100 lpm, the pressure-drop values for the first and second impaction stages were experimentally measured as 1.4 in H2O (0.35 kPa) and 14.2 in H2O (3.53 kPa), respectively. These pressure-drop values agreed with the theoretical predictions (Table 1) of the first and second impaction stages. Maintaining low pressure drop (≤ 3.5 kPa) in both impaction stages was necessary to minimize evaporation losses of volatile components (Furuuchi et al., 2010).

Figure 3.

Pressure drop as a function of GCI flow rate for stages 1 and 2

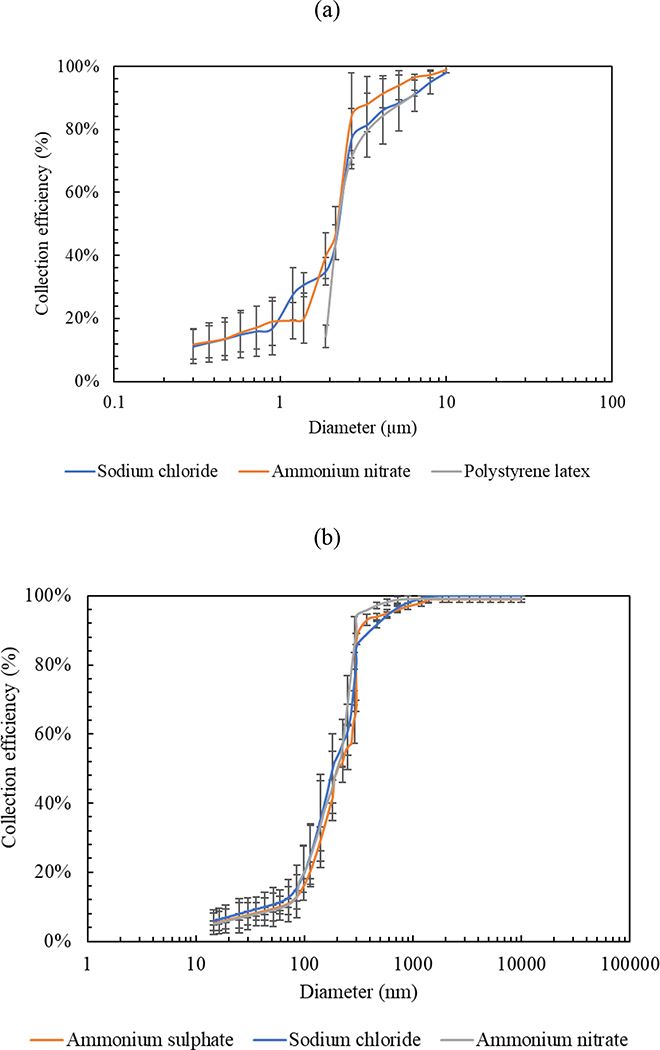

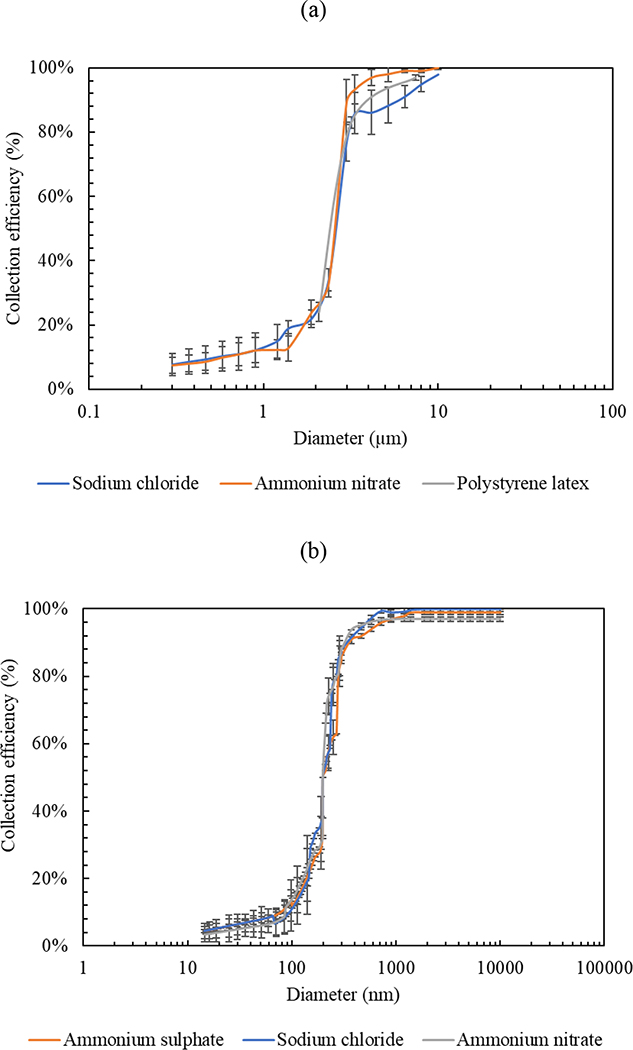

Additionally, Figure 4 shows the particle collection efficiency curves for both impaction stages using gelatin filters as impaction substrates. Figure 4 (a) shows the collection efficiency data as a function of particle size for the first impaction stage using three laboratory-generated aerosols, including PSL, sodium chloride, and ammonium nitrate. The collection efficiency increased rapidly in the range of 2 – 3 μm and was higher than 90 – 95 % for particles larger than 5 μm, corroborating the fact that the GCI equipped with gelatin substrate efficiently minimized coarse particle bouncing and re-entrainment losses. All three test aerosols showed a very good agreement in the critical (50%) cut-point diameter of the first impaction stage, which was approximately 2.4 μm, corresponding to a Stokes number of 0.27 (√St50 =0.52). The figure also demonstrated that the lab aerosols had the same particle size distribution, except of the monodisperse PSL particles (size range of 1.9 – 7 μm) which were coarse particles and used for the characterization of the first impaction stage only. Transitioning to the second impaction stage, Figure 4 (b) shows the collection efficiency curves using three polydisperse aerosols, including ammonium sulfate, ammonium nitrate, and sodium chloride. The collection efficiency increased sharply in the particle size range of 0.16 – 0.27 μm and approached approximately 99% for particles larger than 0.3 μm, which also indicated that the particle losses and bounce-off were not significant in the GCI. Similar to the first stage, the 50% cut-point diameter was in good agreement across the three analyzed aerosols and was, on average, 0.21 μm, corresponding to a Stokes number of 0.29 (√St50 =0.54).

Figure 4.

Collection efficiency curves of the GCI (a) first impaction stage and (b) second impaction stage using gelatin filters and various artificially generated aerosols. X-axis represents optical diameters for particles ≥ 0.3 μm and mobility diameters for particles < 0.3 μm. Error bars are standard deviations.

The experimental values of the 50% cut-point diameters for both impaction stages were very consistent with the theoretical predictions shown in Table 1. Additionally, the experimentally measured square root of Stokes numbers (√St50) for the first and second impaction stages were 0.52 and 0.54, respectively, and were consistent with previous studies that reported experimentally determined √St50 values in the range of 0.4 – 0.6 for impactors with rectangular nozzle (Demokritou et al., 2002, 2004; Misra et al., 2002; Sioutas, Koutrakis, & Burton, 1994). However, they were lower than the theoretical √St50 value (0.77) calculated for a slit-nozzle impactor with a flat rigid substrate (Hinds, 1999). The lower √St50 with respect to the rigid surface is most likely due to the penetration of particles into the pores of the gelatin substrate, causing a slight increase in the collection efficiency and minimizing the particle losses and bouncing-off. Previous studies reported similar results by achieving lower √St50 values than the theoretically calculated for rigid surfaces because of the use of polyurethane foam (PUF) as an impaction substrate (Kavouras et al., 2000; Kavouras & Koutrakis, 2001). The sharpness of the collection efficiency curves was assessed by the geometric standard deviation (GSD) value obtained from the square root of the ratio of particle diameter corresponding to 84.1% collection efficiency to the diameter of 15.9% collection efficiency (Demokritou, Gupta, et al., 2002; Kang et al., 2012; Marple et al., 2004). The GSD of the collection efficiency curves of the test aerosols in the first and second impaction stages were in the range of 1.4 – 1.5, indicating sharp inertial separation of particles.

In addition to the use of gelatin as impaction substrates, we employed 47 mm quartz filters in both impaction stages to obtain particle collection efficiency curves using the same procedure and laboratory-generated aerosols described earlier. Figure 5 shows that the use of quartz filters led to similar collection efficiency patterns and the same 50% cut-point diameters in comparison with gelatin substrates. Therefore, GCI can also be used with different substrates (e.g., quartz, Teflon) without any changes in its technical specifications and particle separation characteristics.

Figure 5.

Collection efficiency curves of the GCI (a) first impaction stage and (b) second impaction stage using quartz filters and various artificially generated aerosols. X-axis represents optical diameters for particles ≥ 0.3 μm and mobility diameters for particles < 0.3 μm. Error bars are standard deviations.

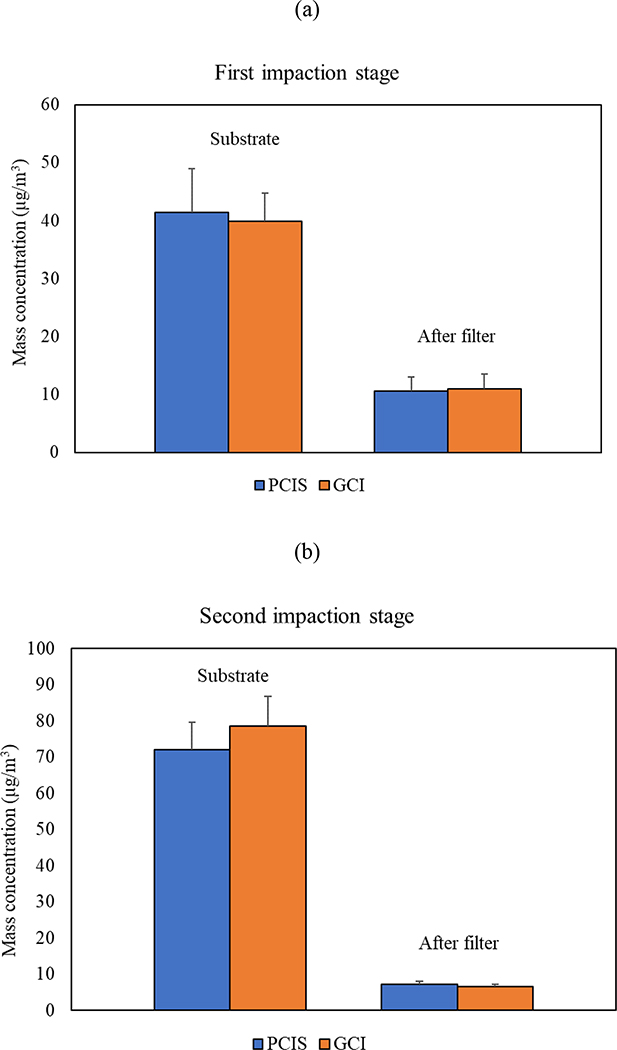

3.1.2. The comparison of particle loading between GCI and PCIS

Figure 6 shows the average mass concentrations of particles collected on gelatin and PTFE substrates using GCI and PCIS, respectively. The data shown in the figure are based on the average value of the three test aerosols (i.e., sodium chloride, ammonium nitrate, and glutaric acid) used in the laboratory experiments. Figure 6 (a) presents the mass concentration results based on the first impaction stage of GCI and the 2.5 μm cut-point stage of the PCIS. Given that both stages had 50% cut-point diameters of approximately 2.5 μm, the findings show an excellent agreement between both impactors with a minimal variability of 3.3% and 4.2% for the impaction substrate and after-filter, respectively. Moreover, Figure 6 (b) also demonstrates consistency in mass concentration between both impactors using 0.25 μm cut-point stage of the PCIS and the second impaction stage of the GCI, along with their after-filter stages. The variability in mass concentrations between the GCI and PCIS were 8.1% and 9.3% for the impaction substrate and after-filter, respectively. The higher mass concentration variability between the GCI and PCIS in this experiment was attributed to the slight difference in the 50% cut-point diameter between the PCIS 0.25 μm stage and GCI second impaction stage, which also explains the higher mass concentration of the PCIS over the GCI in the after-filter stage.

Figure 6.

The comparison of mass concentrations of collected particles using PCIS and GCI (a) first and (b) second impaction stages. Error bars are standard deviations.

3.2. Filter blank analysis

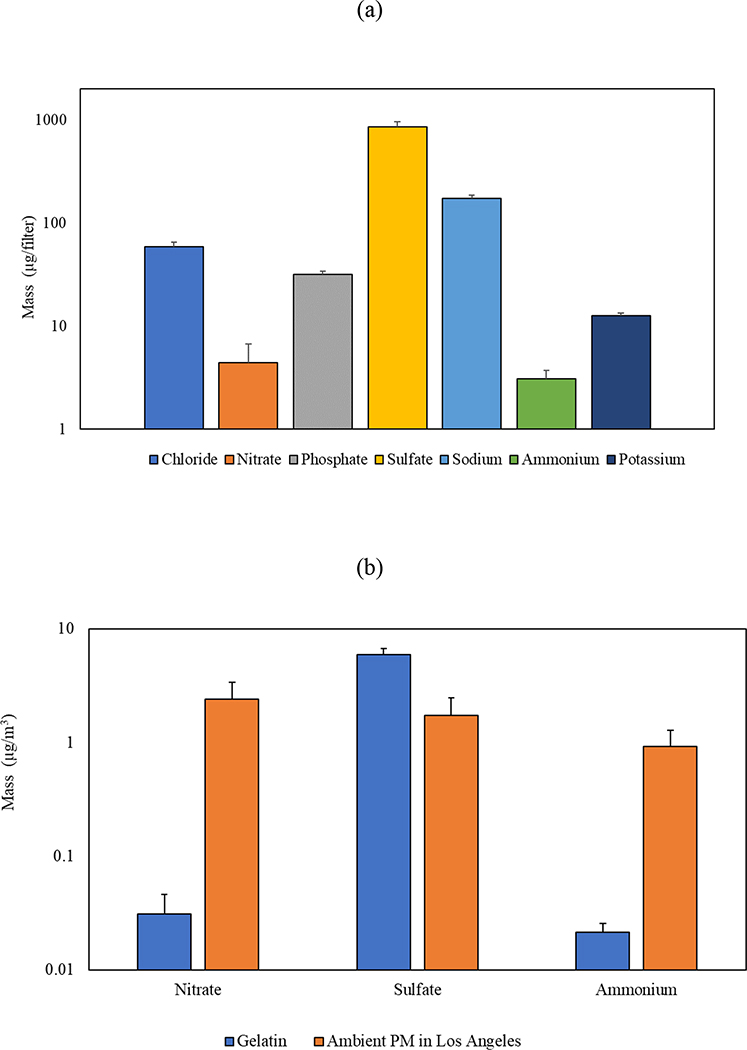

3.2.1. Chemical and toxicological analyses

The IC analysis results are presented in Figure 7 (a), which illustrates the levels of inorganic ions found on blank gelatin filter. The levels of inorganic ions in the blank gelatin were approximately less than 150 μg/filter, excluding sulfate which showed a concentration of 860 μg/filter. Considering the maximum sampling duration (i.e., 24 hr) of the gelatin filter and the operational flow rate (i.e., 100 lpm) of the GCI, the levels of inorganic ions in the blank gelatin filter were converted to airborne concentrations in units of mass per volume of air (m3). The comparison of volume-based values with typical inorganic ion content in ambient PM in Los Angeles (Pirhadi, Mousavi, Taghvaee, et al., 2020) is shown in Figure 7 (b). According to the figure, the inorganic ion levels in the blank gelatin (< 0.05 μg/m3) were substantially lower than the levels in ambient PM, except sulfate (5.97 μg/m3) which was more than twice its level in the ambient air (1.73 μg/m3) in Los Angeles. Considering that ammonium sulfate is a major constituent of PM2.5, these results preclude the use of gelatin substrates for inorganic PM ion analysis, but as we noted earlier, the main purpose of using these substates was for toxicological analysis and more suitable substrates (e.g., quartz or Teflon) can be used with the GCI for the characterization of the inorganic ion content of PM.

Figure 7.

Inorganic ion (a) blank levels in gelatin substrate and (b) the normalized concentrations (per volume of air based on 24 hr sampling) of the blank gelatin in comparison with typical ambient PM levels in Los Angeles. Error bars are standard deviations

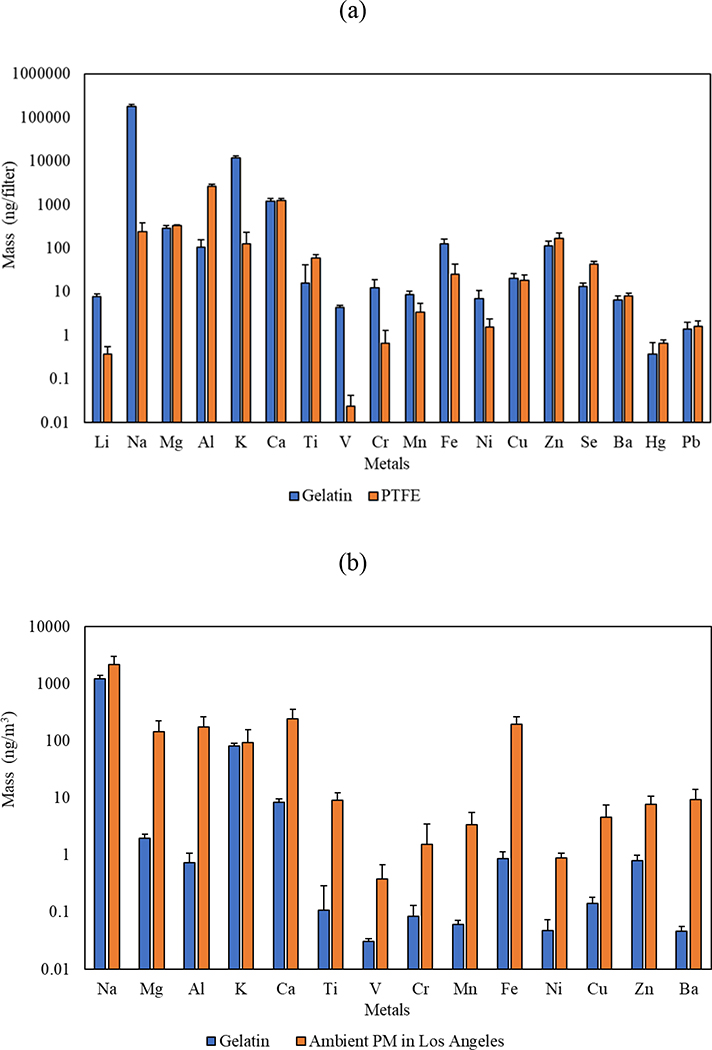

Figure 8 (a) shows the results of ICP-MS analysis for metals and trace elements in blank gelatin and PTFE filters having equal size (i.e., 47 mm). The levels of most metals and trace elements in the blank gelatin were approximately in the range of 10 – 10,000 ng/filter, with the exception of sodium (Na) and potassium (K) which were much higher than other metals with concentrations of 176,758 and 11,668 ng/filter, respectively. It is worth noting that some of these selected metals had negligible values (less than 10 ng/filter), including lithium (Li), manganese (Mn), nickel (Ni), barium (Ba), mercury (Hg), and lead (Pb). The findings also highlight that the concentrations of several metals in gelatin exceeded that of PTFE, including potassium (K), vanadium (V), sodium (Na), and chrome (Cr), especially Na whose concentration in gelatin was 735 times its concentration in the PTFE filter. It is also notable that the blank levels of most redox-active metals (i.e., Fe, Cu, Ti, Zn, Pb, Ba, Mn) were in a comparable range in the two filters. Following the same procedure discussed earlier to convert blank levels to airborne concentrations per volume of air, we expressed the blank metals and trace elements in units of ng/m3 of air in Figure 8 (b) and compared them with the ambient PM in Los Angeles (Pirhadi, Mousavi, Taghvaee, et al., 2020). As shown in the figure, the levels of most metals and trace elements in the blank gelatin (< 1 ng/m3) were lower than those in the ambient air by one order of magnitude or higher. However, the concentrations of sodium and potassium in the blank gelatin were in a comparable range with the ambient levels.

Figure 8.

Metals and trace elements (a) blank levels in gelatin substrate in comparison with PTFE and (b) the normalized concentrations (per volume of air based on 24 hr sampling) of the blank gelatin in comparison with typical ambient PM levels in Los Angeles. Error bars are standard deviations

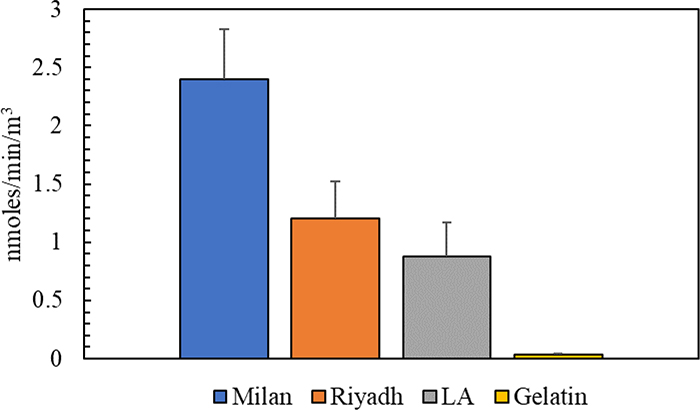

The toxicological analysis showed that the average oxidative potential levels in the blank gelatin filter based on DTT and ROS assays were 5.19 ± 0.88 nmoles/min/filter and 367.3 ± 89.5 μg Zymosan/filter, respectively. The blank redox activity values of the gelatin filter were in a comparable range with the blank PTFE filter, which had DTT and ROS activities of 3.92 ± 0.67 nmoles/min/filter and 283.4 ± 72.9 μg Zymosan/filter, respectively. Furthermore, extensive studies used DTT assay to determine the oxidative potential of PM collected samples in different locations around the globe (i.e., Milan, Los Angeles, and Riyadh) (Altuwayjiri et al., 2022; Cho et al., 2005; Farahani et al., 2022; Hakimzadeh et al., 2020; Saffari et al., 2014). Figure 9 shows the comparison of the normalized DTT activity (per volume of air) of the blank gelatin filter with the ambient PM in the three major cities. According to the figure, the DTT activity of the blank gelatin (0.036 ± 0.006 nmoles/min/m3) is much lower than the ambient PM in Milan, Los Angeles, and Riyadh which had average oxidative potential levels of 2.4 ± 0.43, 0.88 ± 0.29, and 1.2 ± 0.32 nmoles/min/m3, respectively. Therefore, gelatin filters can be used as substrates for the collection of PM samples for toxicological analysis since their blank redox activity values were in a comparable range with other substrates (i.e., PTFE) and were considerably low compared to the DTT responses recorded in typical ambient PM around the world.

Figure 9.

DTT activity comparison between the blank gelatin substrate and PM collections in three major cities around the world. Error bars are standard deviations.

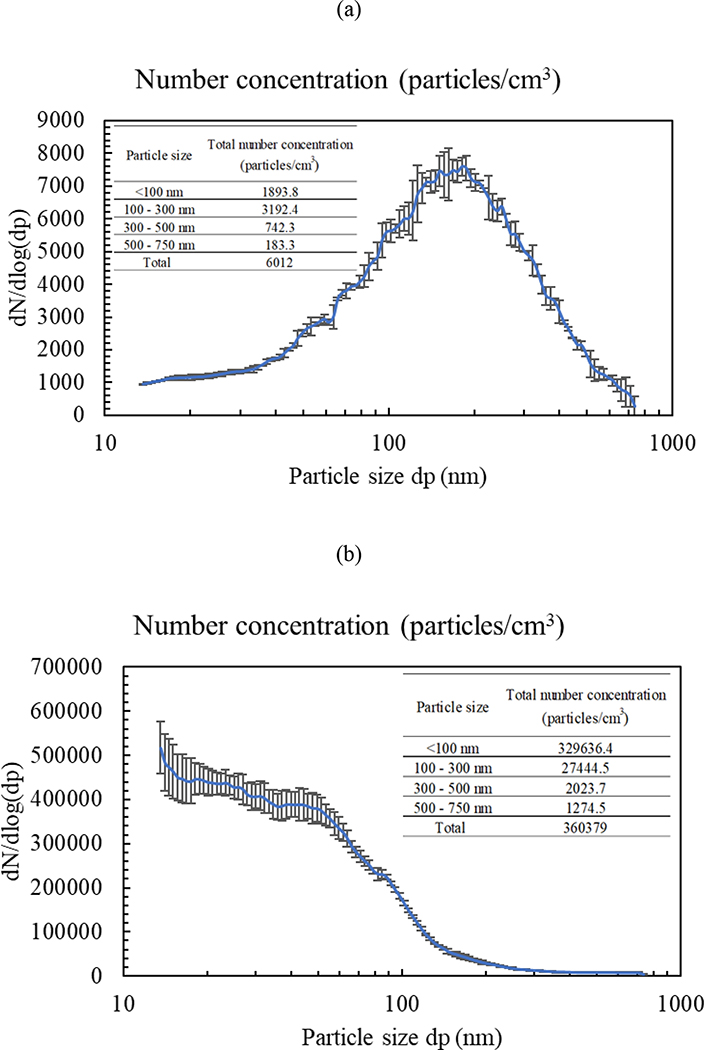

3.2.2. Particle number concentrations of re-aerosolized gelatin blank filters and filters with ambient PM

The SMPS was employed to assess the particle number concentrations of the two suspensions (i.e., blank gelatin and UFP) by aerosolizing the slurries using the typical nebulization system illustrated in the methodology section. Accordingly, the particle number distribution curves as a function of particle diameter were obtained and presented in Figure 10 for the blank gelatin and UFP slurries. As clearly shown in the figure, the particle number concentration for UFP exceeded the blank gelatin by approximately two orders of magnitudes. The total particle number concentrations for blank gelatin and UFP suspensions were 6,012 ± 248 and 360,379 ± 21,757 particles/cm3, respectively. This considerably low particle number concentration of the blank gelatin in comparison with UFP further corroborates the use of gelatin filters in the field of aerosol sampling.

Figure 10.

Particle number concentrations as a function of particle diameter for (a) gelatin and (b) UFP suspensions. X-axis represents mobility diameters measured by SMPS. Error bars are standard deviations.

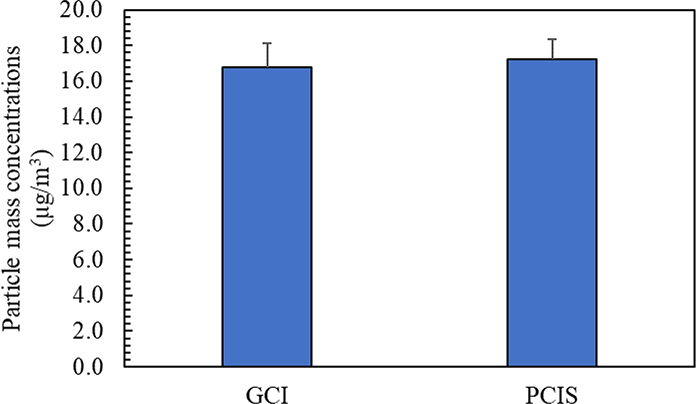

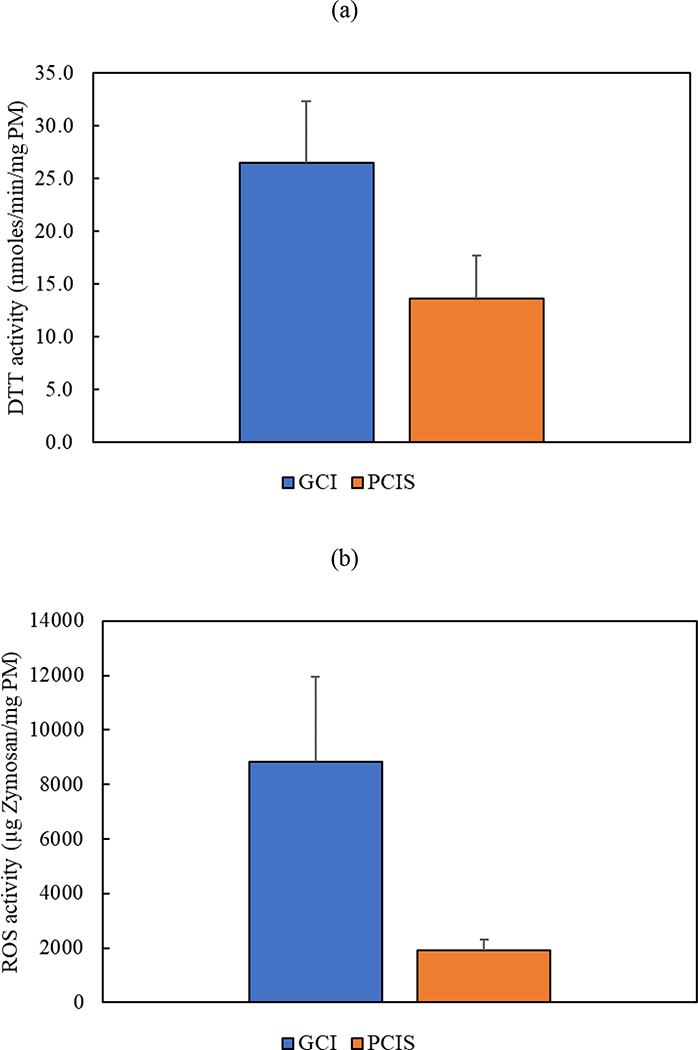

3.3. Field comparison between the oxidative potential of particles collected using the GCI and the PCIS

Before performing the toxicological analysis on the collected PM2.5 samples, the ambient particle mass concentrations obtained by the GCI and PCIS were compared in Figure 11, which shows a very good agreement between the two samplers (i.e., minimal variability of less than 3%). The consistency between the GCI equipped with gelatin substrate and the PCIS equipped with PTFE substrate corroborates the suitable use of gelatin filters in field sampling without any issues related to water absorption. The collected PM2.5 samples were then analyzed using DTT and ROS assays in order to compare the redox activity of particles collected on gelatin filters using the GCI with particles collected on PTFE filters using the PCIS. It should be noted that the blank redox activity values of gelatin and PTFE filters were subtracted from the redox activity of the collected PM2.5 samples. For comparison purposes, we normalized the redox activity to PM mass, obtained from the gravimetric analysis, to express the values in units of μg Zymosan Units/mg PM and nmoles/min/mg PM for ROS and DTT, respectively. Figure 12 (a) shows the results of the DTT assay in which the oxidative potential of particles collected using the GCI was approximately twice the PCIS, with redox activities of 26.44 nmoles/min/mg PM and 13.56 nmoles/min/mg PM for the GCI and PCIS, respectively. In addition, the ROS results shown in Figure 12 (b) further corroborate the ability of the GCI to achieve higher particle redox activity values in comparison with the PCIS. As illustrated in the figure, the ROS activity of particles collected using GCI equipped with gelatin filter (8813.2 μg Zymosan Units/mg PM) is more than 4 times the redox activity of particles collected on PTFE filter using PCIS (1909.1 μg Zymosan Units/mg PM). The higher PM oxidative potential of the GCI compared to the PCIS might be attributed to the superiority of the GCI in capturing water-insoluble redox-active PM species (e.g., elemental carbon, PAH, other insoluble organics, and transition metals such as iron, lead, nickel). Previous studies have reported the significant contribution of water-insoluble compounds to the oxidative potential of PM2.5 (Daher et al., 2011; Pirhadi, Mousavi, & Sioutas, 2020). D. Wang et al. (2013) conducted an experiment using aerosol-into-liquid collector to compare the ROS levels of two PM2.5 suspensions, one of which was filtered from the water-insoluble species. They concluded that the filtered suspension resulted in approximately 30% lower ROS activity than the unfiltered slurry, further underscoring the effective role of insoluble compounds in the overall redox activity of PM2.5. These observations support the efficiency of using the GCI in collecting ambient PM for further toxicological studies and in-vivo and in-vitro assays.

Figure 11.

Ambient PM2.5 mass concentrations based on the GCI and PCIS. The error bars are standard deviations.

Figure 12.

Redox activity of particles collected on gelatin filter using the GCI in comparison with particles collected on PTFE using the PCIS based on (a) DTT and (b) ROS assays. Error bars are standard deviations.

4. Summary and conclusion

In this study, a two-stage gelatin cascade impactor was developed and evaluated in the laboratory as well as in field experiments. The GCI operates at a high flow rate of 100 lpm and consists of two impaction stages with 2.5 μm and 0.2 μm cut-point diameters, respectively. The pressure drop values in both impaction stages were low (≤ 3.5 kPa) in order to minimize evaporation losses of volatile components. Furthermore, laboratory experiments were conducted using artificially produced aerosols to corroborate the agreement of the GCI with the PCIS in terms of the mass concentration of collected particles, which showed a minimal variability of less than 10% between both impactors. In addition to the lab experiments, field experiments were carried out to collect PM2.5 particles on PTFE and gelatin filters using PCIS and GCI, respectively. Since the GCI was operated with a high sampling flow rate (100 lpm), it was able to collect considerable amounts of PM in 24 hr intervals. The field tests corroborated the higher particle oxidative potential levels measured by the GCI in comparison with the PCIS based on both DTT and ROS assays. The DTT and ROS activities of particles collected using the GCI were 26.44 nmoles/min/mg PM and 8813.2 μg Zymosan Units/mg PM, respectively, which were more than twice the redox activities of particles collected by the PCIS. This can be attributed to the superiority of the GCI in capturing water-insoluble redox-active PM species on gelatin filters, which were dissolved in water to extract all collected particles. Although gelatin filters offer significant advantages to the field of aerosol sampling, they might not be suitable for PM chemical characterization studies due to the elevated blank levels of some metals and inorganic ions (e.g., sulfate, sodium). In addition, field experiments to collect ambient PM on gelatin filters should be limited to 24-hr sampling duration to avoid any possible damage to the filter media. If PM chemical analysis or long-term sampling durations are required, the GCI can be equipped with different types of substrates without any significant change in its technical specifications or particle separation characteristics, as was verified experimentally by the use of quartz and gelatin substrates. The GCI is a significant technological contribution to air pollution studies and the field of aerosol sampling due to its ability to achieve high-volume collection of multi-sized PM without significant particle bouncing and re-entrainment losses. It also enables researchers in the field of environmental health to conduct inhalation and toxicological studies using water-soluble filters (i.e., gelatin) that can easily dissolve in water and achieve a particle extraction efficiency of 100%. The GCI equipped with gelatin filters is a powerful replacement for traditional cascade impactors due to its advantages in collecting considerable amounts of real-life PM redox-active constituents and preserving their chemical compositions for further toxicity assays.

Highlights.

Two-stage cascade impactor was developed and evaluated in the lab and field tests

GCI can separate PM into the following diameters: >2.5 μm, 0.2–2.5 μm, and <0.2 μm

Gelatin filters were used for the extraction of soluble and insoluble PM species

Redox activities of PM collected using GCI were more than twice those of PCIS

GCI can collect considerable redox-active PM species for toxicity assays

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH) (grants: R01ES029395 and R01ES032806). The authors would like to acknowledge the Ph.D. fellowship awards from the University of Southern California (USC) and Kuwait University.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

☒ The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Credit authorship contribution statement

Mohammad Aldekheel: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft

Vahid Jalali Farahani: Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Ramin Tohidi: Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Abdulmalik Altuwayjiri: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Constantinos Sioutas: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Altuwayjiri A, Pirhadi M, Kalafy M, Alharbi B, & Sioutas C (2022). Impact of different sources on the oxidative potential of ambient particulate matter PM10 in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A focus on dust emissions. Science of the Total Environment, 806. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JO, Thundiyil JG, & Stolbach A (2012). Clearing the air: A review of the effects of particulate matter air pollution on human health. Journal of Medical Toxicology, 8(2), 166–175. 10.1007/s13181-011-0203-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas K, & Gupta T (2017). Design and Development of a Novel PM Inertial Impactor With Reduced Particle Bounce Off. Journal of Energy and Environmental Sustainability, 3, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Carranza SE, & Pantano P (2003). Fluorescence microscopy and flow cytofluorometry of reactive oxygen species. In Applied Spectroscopy Reviews (Vol. 38, Issue 2, pp. 245–261). 10.1081/ASR-120021168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Romay FJ, & Marple VA (2018). Design and evaluation of a low flow personal cascade impactor. Aerosol Science and Technology, 52(2), 192–197. 10.1080/02786826.2017.1388498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho AK, Sioutas C, Miguel AH, Kumagai Y, Schmitz DA, Singh M, Eiguren-Fernandez A, & Froines JR (2005). Redox activity of airborne particulate matter at different sites in the Los Angeles Basin. Environmental Research, 99(1), 40–47. 10.1016/j.envres.2005.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford S, Mazaheri M, Salimi F, Ezz WN, Yeganeh B, Low-Choy S, Walker K, Mengersen K, Marks GB, & Morawska L (2018). Effects of exposure to ambient ultrafine particles on respiratory health and systemic inflammation in children. Environment International, 114, 167–180. 10.1016/j.envint.2018.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daher N, Ning Z, Cho AK, Shafer M, Schauer JJ, & Sioutas C (2011). Comparison of the Chemical and Oxidative Characteristics of Particulate Matter (PM) Collected by Different Methods: Filters, Impactors, and BioSamplers. Aerosol Science and Technology, 45(11), 1294–1304. 10.1080/02786826.2011.590554 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delfino RJ, Staimer N, Tjoa T, Gillen DL, Schauer JJ, & Shafer MM (2013). Airway inflammation and oxidative potential of air pollutant particles in a pediatric asthma panel. Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology, 23(5), 466–473. 10.1038/jes.2013.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demokritou P, Kavouras IG, Ferguson ST, & Koutrakis P (2002). Development of a high volume cascade impactor for toxicological and chemical characterization studies. Aerosol Science and Technology, 36(9), 925–933. 10.1080/02786820290092113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demokritou P, Lee SJ, & Koutrakis P (2004). Development and Evaluation of a High Loading PM2.5 Speciation Sampler. Aerosol Science and Technology, 38(2), 111–119. 10.1080/02786820490249045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farahani VJ, Altuwayjiri A, Pirhadi M, Verma V, Ruprecht AA, Diapouli E, Eleftheriadis K, & Sioutas C (2022). The oxidative potential of particulate matter (PM) in different regions around the world and its relation to air pollution sources. Environmental Science: Atmospheres, 2(5), 1076–1086. 10.1039/D2EA00043A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuuchi M, Eryu K, Nagura M, Hata M, Kato T, Tajima N, Sekiguchi K, Ehara K, Seto T, & Otani Y (2010). Development and performance evaluation of air sampler with inertial filter for nanoparticle sampling. Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 10(2), 185–192. 10.4209/aaqr.2009.11.0070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gauderman WJ, Urman R, Avol E, Berhane K, McConnell R, Rappaport E, Chang R, Lurmann F, & Gilliland F (2015). Association of Improved Air Quality with Lung Development in Children. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(10), 905–913. 10.1056/NEJMoa1414123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George KV, Patil DD, Kumar P, & Alappat BJ (2012). Field comparison of cyclonic separator and mass inertial impactor for PM10 monitoring. Atmospheric Environment, 60, 247–252. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.06.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlofs-Nijland ME, Rummelhard M, Boere AJF, Leseman DLAC, Duffin R, Schins RPF, Borm PJA, Sillanpää M, Salonen RO, & Cassee R, F. (2009). Particle Induced Toxicity in Relation to Transition Metal and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Contents. Environmental Science & Technology, 43(13), 4729–4736. 10.1021/es803176k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh K, & Masuda H (2000). Improvement of the classification performance of a rectangular jet virtual impactor. Aerosol Science and Technology, 32(3), 221–232. 10.1080/027868200303759 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hakimzadeh M, Soleimanian E, Mousavi A, Borgini A, de Marco C, Ruprecht AA, & Sioutas C (2020). The impact of biomass burning on the oxidative potential of PM2.5 in the metropolitan area of Milan. Atmospheric Environment, 224. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117328 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Hudda N, Ning Z, Kim HJ, Kim YJ, & Sioutas C (2009). A novel bipolar charger for submicron aerosol particles using carbon fiber ionizers. Journal of Aerosol Science, 40(4), 285–294. 10.1016/j.jaerosci.2008.11.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds WC (1999). Aerosol technology: properties, behavior, and measurement of airborne particles. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Huang R-J, Yang L, Shen J, Yuan W, Gong Y, Guo J, Cao W, Duan J, Ni H, Zhu C, Dai W, Li Y, Chen Y, Chen Q, Wu Y, Zhang R, Dusek U, O’Dowd C, & Hoffmann T (2020). Water-Insoluble Organics Dominate Brown Carbon in Wintertime Urban Aerosol of China: Chemical Characteristics and Optical Properties. Environmental Science & Technology, 54(13), 7836–7847. 10.1021/acs.est.0c01149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby J, Bau S, & Witschger O (2011). CAIMAN: a versatile facility to produce aerosols of nanoparticles. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 304, 012014. 10.1088/1742-6596/304/1/012014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan S, & Balasubramanian R (2006). Determination of water-soluble inorganic and organic species in atmospheric fine particulate matter. Microchemical Journal, 82(1), 49–55. 10.1016/j.microc.2005.07.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kavouras IG, Ferguson ST, Wolfson JM, & Koutrakis P (2000). Development and Validation of a High-Volume, Low-Cutoff Inertial Impactor. Inhalation Toxicology, 12(sup2), 35–50. 10.1080/08958378.2000.11463198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavouras IG, & Koutrakis P (2001). Use of Polyurethane Foam as the Impaction Substrate/Collection Medium in Conventional Inertial Impactors. Aerosol Science and Technology, 34(1), 46–56. 10.1080/02786820118288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Chang M-C, Kim D, & Sioutas C (2000). A New Generation of Portable Coarse, Fine, and Ultrafine Particle Concentrators for use in Inhalation Toxicology. Inhalation Toxicology, 12(sup1), 121–137. 10.1080/0895-8378.1987.11463187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Jaques PA, Chang M, Froines JR, & Sioutas C (2001). Versatile aerosol concentration enrichment system (VACES) for simultaneous in vivo and in vitro evaluation of toxic effects of ultrafine, fine and coarse ambient particles Part I: Development and laboratory characterization. Journal of Aerosol Science, 32(11), 1281–1297. 10.1016/S0021-8502(01)00057-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger UK, Marcolli C, & Reid JP (2012). Exploring the complexity of aerosol particle properties and processes using single particle techniques. Chemical Society Reviews, 41(19), 6631. 10.1039/c2cs35082c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai Y, Koide S, Taguchi K, Endo A, Nakai Y, Yoshikawa T, & Shimojo N (2002). Oxidation of proximal protein sulfhydryls by phenanthraquinone, a component of diesel exhaust particles. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 15(4), 483–489. 10.1021/tx0100993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai Y, & Shimojo N (2002). Possible Mechanisms for Induction of Oxidative Stress and Suppression of Systemic Nitric Oxide Production Caused by Exposure to Environmental Chemicals. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 7(4), 141–150. 10.1265/ehpm.2002.141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landreman AP, Shafer MM, Hemming JC, Hannigan MP, & Schauer JJ (2008). A macrophage-based method for the assessment of the reactive oxygen species (ROS) activity of atmospheric particulate matter (PM) and application to routine (daily-24 h) aerosol monitoring studies. Aerosol Science and Technology, 42(11), 946–957. 10.1080/02786820802363819 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JH, Park D, & Yook SJ (2020). Development of a multi-slit virtual impactor as a high-volume bio-aerosol sampler. Separation and Purification Technology, 250. 10.1016/j.seppur.2020.117275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lough GC, Schauer JJ, Park JS, Shafer MM, Deminter JT, & Weinstein JP (2005). Emissions of metals associated with motor vehicle roadways. Environmental Science and Technology, 39(3), 826–836. 10.1021/es048715f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeng J-Y, Park D, Kim Y-H, Hwang J, & Kim Y-J (2007). Micromachined Cascade Virtual Impactor for Aerodynamic Size Classification of Airborne Particles. IEEE 20th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS). 10.1109/MEMSYS.2007.4433121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marple VA, Liu BYH, & Burton RM (1990a). High-volume impactor for sampling fine and coarse particles. Journal of the Air and Waste Management Association, 40(5), 762–767. 10.1080/10473289.1990.10466722 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marple VA, Liu BYH, & Burton RM (1990b). High-volume Impactor for Sampling Fine and Coarse Particles. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association, 40(5), 762–767. 10.1080/10473289.1990.10466722 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marple VA, Rubow KL, & Behm SM (1991). A Microorifice Uniform Deposit Impactor (MOUDI): Description, Calibration, and Use. Aerosol Science and Technology, 14(4), 434–446. 10.1080/02786829108959504 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Misra C, Kim S, Shen S, & Sioutas C (2002). A high flow rate, very low pressure drop impactor for inertial separation of ultrafine from accumulation mode particles. Journal of Aerosol Science, 33(5), 735–752. 10.1016/S0021-8502(01)00210-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KF, Ning Z, Ntziachristos L, Schauer JJ, & Sioutas C (2007). Daily variation in the properties of urban ultrafine aerosol-Part I: Physical characterization and volatility. Atmospheric Environment, 41(38), 8633–8646. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.07.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelin TD, Joseph AM, Gorr MW, & Wold LE (2012). Direct and indirect effects of particulate matter on the cardiovascular system. Toxicology Letters, 208(3), 293–299. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning Z, Geller MD, Moore KF, Sheesley R, Schauer JJ, & Sioutas C (2007). Daily variation in chemical characteristics of urban ultrafine aerosols and inference of their sources. Environmental Science and Technology, 41(17), 6000–6006. 10.1021/es070653g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning Z, Moore KF, Polidori A, & Sioutas C (2006). Field Validation of the New Miniature Versatile Aerosol Concentration Enrichment System (mVACES). Aerosol Science and Technology, 40(12), 1098–1110. 10.1080/02786820600996422 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patel P, Aggarwal SG, Tsai C-J, & Okuda T (2021). Theoretical and field evaluation of a PM2.5 high-volume impactor inlet design. Atmospheric Environment, 244, 117811. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117811 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pirhadi M, Mousavi A, & Sioutas C (2020). Evaluation of a high flow rate electrostatic precipitator (ESP) as a particulate matter (PM) collector for toxicity studies. Science of The Total Environment, 739, 140060. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirhadi M, Mousavi A, Taghvaee S, Shafer MM, & Sioutas C (2020). Semi-volatile components of PM2.5 in an urban environment: Volatility profiles and associated oxidative potential. Atmospheric Environment, 223. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2019.117197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polichetti G, Cocco S, Spinali A, Trimarco V, & Nunziata A (2009). Effects of particulate matter (PM10, PM2.5 and PM1) on the cardiovascular system. Toxicology, 261(1–2), 1–8. 10.1016/j.tox.2009.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffari A, Daher N, Shafer MM, Schauer JJ, & Sioutas C (2014). Seasonal and spatial variation in dithiothreitol (DTT) activity of quasi-ultrafine particles in the Los Angeles Basin and its association with chemical species. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A, 49(4), 441–451. 10.1080/10934529.2014.854677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardar SB, Fine PM, Mayo PR, & Sioutas C (2005). Size-fractionated measurements of ambient ultrafine particle chemical composition in Los Angeles using the NanoMOUDI. Environmental Science and Technology, 39(4), 932–944. 10.1021/es049478j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoonen MAA, Cohn CA, Roemer E, Laffers R, Simon SR, & O’Riordan T (2006). Mineral-Induced Formation of Reactive Oxygen Species. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry, 64(1), 179–221. 10.2138/rmg.2006.64.7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarze PE, Øvrevik J, Låg M, Refsnes M, Nafstad P, Hetland RB, & Dybing E (2006). Particulate matter properties and health effects: consistency of epidemiological and toxicological studies. Human & Experimental Toxicology, 25(10), 559–579. 10.1177/096032706072520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer MM, Hemming JDC, Antkiewicz DS, & Schauer JJ (2016). Oxidative potential of size-fractionated atmospheric aerosol in urban and rural sites across Europe. Faraday Discussions, 189, 381–405. 10.1039/C5FD00196J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shima H, Koike E, Shinohara R, & Kobayashi T (2006). Oxidative Ability and Toxicity of n-Hexane Insoluble Fraction of Diesel Exhaust Particles. Toxicological Sciences, 91(1), 218–226. 10.1093/toxsci/kfj119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sioutas C, Koutrakis P, & Burton RM (1994). Development of a Low Cutpoint Slit Virtual Impactor for Sampling Ambient Fine Particles. Journal of Aerosol Science, 25(7), 1321–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Sioutas C, Koutrakis P, & Olson BA (1994). Development and evaluation of a low cutpoint virtual impactor. Aerosol Science and Technology, 21(3), 223–235. 10.1080/02786829408959711 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soo JC, Monaghan K, Lee T, Kashon M, & Harper M (2016). Air sampling filtration media: Collection efficiency for respirable size-selective sampling. Aerosol Science and Technology, 50(1), 76–87. 10.1080/02786826.2015.1128525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita K, Kin Y, Yagishita M, Ikemori F, Kumagai K, Ohara T, Kinoshita M, Nishimura K, Takagi Y, & Nakajima D (2019). Evaluation of the genotoxicity of PM2.5 collected by a high-volume air sampler with impactor. Genes and Environment, 41(1), 7. 10.1186/s41021-019-0120-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taghvaee S, Mousavi A, Sowlat MH, & Sioutas C (2019). Development of a novel aerosol generation system for conducting inhalation exposures to ambient particulate matter (PM). Science of the Total Environment, 665, 1035–1045. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valavanidis A, Fiotakis K, & Vlachogianni T (2008). Airborne Particulate Matter and Human Health: Toxicological Assessment and Importance of Size and Composition of Particles for Oxidative Damage and Carcinogenic Mechanisms. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part C, 26(4), 339–362. 10.1080/10590500802494538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga B, Kiss G, Ganszky I, Gelencsér A, & Krivácsy Z (2001). Isolation of water-soluble organic matter from atmospheric aerosol. Talanta, 55(3), 561–572. 10.1016/S0039-9140(01)00446-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Pakbin P, Saffari A, Shafer MM, Schauer JJ, & Sioutas C (2013). Development and Evaluation of a High-Volume Aerosol-into-Liquid Collector for Fine and Ultrafine Particulate Matter. Aerosol Science and Technology, 47(11), 1226–1238. 10.1080/02786826.2013.830693 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Bhambri P, Ivey J, & Vehring R (2017). Design and pharmaceutical applications of a low-flow-rate single-nozzle impactor. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 533(1), 14–25. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.09.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Xiong L, & Tang M (2017). Toxicity of inhaled particulate matter on the central nervous system: neuroinflammation, neuropsychological effects and neurodegenerative disease. Journal of Applied Toxicology, 37(6), 644–667. 10.1002/jat.3451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]