Abstract

Knowledge tests used to evaluate child protection training program effectiveness for early childhood education providers may suffer from threats to construct validity given the contextual variability inherent within state-specific regulations around mandated reporting requirements. Unfortunately, guidance on instrument revision that accounts for such state-specific mandated reporting requirements is lacking across research on evaluation practices. This study, therefore, explored how collection and integration of validity evidence using a mixed methods framework can guide the instrument revision process to arrive at a more valid program outcome measure.

Keywords: mandated reporting, child maltreatment, validity, mixed methods, instrument revision, child abuse knowledge test, effectiveness outcomes

Mandated reporting laws necessitate that early childhood education (ECE) providers report suspected abuse/neglect for children under their care (National Child Abuse and Neglect Training and Publications Project, 2014). This is particularly important for the ECE field, given that 47% of child maltreatment victims in 2017 were between 0 and 5 years of age (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019). Exposure to abuse/neglect during this sensitive period of development can lead to long-term negative changes in developmental outcomes and functioning (Fox et al., 2010). Early identification, therefore, provides an opportunity to disrupt maltreatment, prevent further harm, and refer children and families to needed services for ongoing support. These early prevention efforts capitalize on children’s developmental plasticity in early childhood to foster positive developmental changes (Fox et al., 2010; Jones Harden et al., 2016).

Unfortunately, ECE providers make up less than 1% of Child Protective Services reports of suspected child abuse/neglect (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019). This glaring disproportionality between the number of child victims and reporting practices of ECE providers requires effective child protection training, so that early identification can occur, improving the public health response to young children experiencing maltreatment. Although the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Reauthorization Act (2010), or CAPTA, provides a broad definition of maltreatment at the federal level, there remains variability in how states define what constitutes child abuse/neglect and what must be reported (see Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2016, for examples of state-level definitions). These various definitions and mandated reporting duties give rise to different conceptual models for providing child protection training, with subsequent variability in how program outcomes are measured. If the main purpose of outcome evaluation activities is “to demonstrate the nature of change” (Grinnell et al., 2012, p. 259) as a result of child protection training program or intervention participation, then arriving at an accurate conclusion about program effectiveness may be problematic if such changes are attributable to measurement error. Therefore, issues of validity around measurement development and revision should be considered when interpreting instruments as being reflective of change in the program outcomes of interest (Braverman, 2012).

Issues of Validity in Evaluating Child Protection Training Programs

According to Mathews and colleagues (2015), child protection training programs are considered a core public health strategy aimed at improving the accurate reporting of suspected child abuse/neglect by professionals who are required by law to do so. Such training programs are typically implemented at the organizational level or individual provider level as discrete educational training strategies (Gilbert et al., 2009; Powell et al., 2012). Within the field of ECE, child protection training has been shown to effectively increase knowledge about mandated reporting laws and practice (i.e., the typical training program outcome of interest; Carter et al., 2006) for students in preservice education (Kenny, 2007; McKee & Dillenburger, 2012) and educators in practice who attend professional development training (Mathews et al., 2017). From a methodological standpoint, therefore, evaluators and relevant stakeholders should have confidence that these outcome measures of knowledge improvement show a high degree of reliability (i.e., consistency of data and data collection) and validity (i.e., the degree to which instruments accurately represent the construct they are intended to measure; Poister, 2015).

However, given that child protection training content areas are typically governed by state laws, variability in legal definitions presents a problem in evaluating program effectiveness when core definitions underlying the construct of knowledge vary by jurisdiction. Known as semantic drift (Nastasi & Hitchcock, 2016), these changes in the meaning of test items due to contextual differences across geographic locations (e.g., state variability in maltreatment definitions) or professions (e.g., education, mental health, medical, or legal) foster concerns about the validity of instruments used to measure knowledge improvement as an outcome of interest in effectiveness studies. Therefore, evaluations of child protection training programs should employ knowledge tests that are continually revised and validated to ensure that knowledge outcomes accurately reflect the definitions of maltreatment for specific states where they will be used. This iterative process of revision not only ensures sound psychometric properties for measures but also adds “policy salience (as) … intrinsic to the definition of a good measure” (Weitzman & Silver, 2013, p. 116), given the central role played by state laws in defining the construct of knowledge of child protection.

Gathering and Integrating Validity Evidence Using Mixed Methods

The Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (henceforth referred to as Standards) refers to validity as “the degree to which evidence and theory support the interpretations of test scores for proposed uses of tests” (American Educational Research Association [AERA], American Psychological Association [APA], National Council on Measurement in Education [NCME], 2014, p. 11). Validation studies are typically conducted to assess empirical evidence that can inform the refinement of a construct’s definition, revise the test, or identify other areas that need further examination. Guided by a unified validity framework (Messick, 1989a; Messick 1989b; Morell & Tan, 2009), the goal of the current study was to gather and integrate multiple sources or facets of validity evidence to refine the iLookOut for Child Abuse Knowledge Test (also known as iLookOut Knowledge Test) in an iterative manner across multiple stages. Specifically, the current study included support from three sources of validity evidence: content-related (i.e., themes, wording, and format of the items guided by CAPTA), response processes (i.e., how ECE providers understood test items as representing knowledge of child abuse), and internal structure (i.e., knowledge of child abuse represented as a single dimension or multiple dimensions). These sources of validity evidence were evaluated to see how scores (i.e., overall or subscale) on the iLookOut Knowledge Test can provide a valid inference that ECE providers have adequate knowledge about mandated reporting requirements based on the CAPTA framework.

The use of mixed methods research is an important design consideration when gathering sources of validity evidence and establishing methodological rigor (Braverman, 2012) for measurement-related outcomes (e.g., knowledge tests) to evaluate child protection training effectiveness. Once collected using both quantitative and qualitative strands, these sources of validity evidence can be integrated across multiple stages. Integration of validity evidence “involves intentionally bringing together quantitative and qualitative approaches such that their combination leads to greater understanding of the topic” (McCrudden & McTigue, 2019, p. 381). Specific to the current study, integration was conducted at the methods level (i.e., data collection and analysis are linked through building where one data collection procedure informs subsequent procedures) and the interpretation and reporting level (i.e., data sets are intentionally mixed to demonstrate how they are more informative when combined than either data set alone). Integration at the interpretation and reporting level typically includes an integrated report or narrative, as well as a joint display (i.e., a visual display representing the quantitative and qualitative results in a single display) that can provide meta-inferences about how the validity argument can be used to inform instrument revision across multiple stages.

The Current Study

The current study evaluated three sources of validity evidence, content-related, response process, and internal structure, and the degree to which these supported the interpretation of the iLookOut Knowledge Test scores as representing ECE providers’ knowledge of child abuse mandated reporting practices. The iLookOut Knowledge Test was developed to evaluate the effectiveness of iLookOut for Child Abuse, an evidence-based child protection training program, which was delivered as an online professional development intervention for ECE providers (Levi et al., 2019). This multiphase project is currently being scaled up and adapted across multiple states where a valid and consistent measure is needed to evaluate cross-regional effectiveness and minimize semantic drift. Therefore, methodological rigor at the measurement level was a necessary precursor to continuing evaluation efforts as the project moves forward.

To this end, our current study aimed to answer the following research questions. First, to what degree does the iLookOut Knowledge Test reflect the dimensionality inherent in the definitional construct of child abuse and neglect? Second, how do ECE providers from different states (i.e., statutory differences in child abuse definitions) interpret items on the iLookOut Knowledge Test? Finally, to what extent do the quantitative structural assessment and qualitative interpretation results provide overlapping evidence on items that need to be revised in order to improve instrument validity?

We showed how integration of validity evidence using a mixed methods framework was helpful in addressing semantic drift to maintain an outcome measure’s construct validity when implemented in multiple phases across different states. The current study outlined how integration in mixed methods was used to iteratively revise and further validate an instrument to ensure that score interpretations accurately reflected ECE providers’ knowledge of mandated reporting requirements.

Method

Mixed Methods Study Design Overview

Our mixed methods framework involved the use of both quantitative (QUAN) and qualitative (QUAL) strands to understand instrument development and refinement more fully (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018; Johnson et al., 2007; Perry et al., 2013). Specifically, our study design consisted of four main phases with the uppercase designation indicating priority in the design. First, we collected quantitative data (QUAN I) to evaluate the initial internal structure of the iLookOut Knowledge Test. Second, we collected qualitative response process data (QUAL) using cognitive laboratory methods to evaluate similarities and differences in participants’ interpretations of items on the iLookOut Knowledge Test. Third, we used findings from the qualitative analysis to revise the items that had substantively different interpretations. Finally, additional quantitative data (QUAN II) were collected to further evaluate structural validity of the iLookOut Knowledge Test using the revised items. This advanced mixed methods design contained elements of an explanatory sequential design (e.g., QUAN I → qual; Morell & Tan, 2009) and an exploratory sequential design (e.g., QUAL → quan II; Nastasi et al., 2007) to understand and address semantic drift and construct validity concerns in an iterative process necessary to revise the iLookOut Knowledge Test through multiple phases of project implementation.

Content-related evidence and the iLookOut Knowledge Test.

The knowledge test was developed and piloted prior to the initial implementation of the iLookOut child protection training program and consisted of 21 items about child abuse/neglect and its reporting—with each item having one correct answer and being equally weighted for a maximum score of 21. The knowledge test was developed by an interdisciplinary group of experts. Pilot testing involved a multistage process that began with a focus group of experienced ECE providers who reviewed the test items’ comprehensibility and relevance. This was followed by cognitive interviews with academic experts in child welfare law to provide content-related evidence of validity and then field testing with ECE undergraduate students and full-time ECE providers to evaluate and improve content-related validity evidence and reliability prior to effectiveness testing of the intervention program. Across all phases of program implementation, the iLookOut Knowledge Test was used as a measure of program effectiveness by examining pre- to posttest changes in participants’ overall scores. The present study complied with relevant ethical standards for human subjects’ protections based on the approval by the institutional review board (study #0376) of the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine.

Quantitative Stage (QUAN I): Structural Validity

Participants and procedures.

Participants for QUAN I were Pennsylvania ECE providers (n = 5,379) who completed the iLookOut child protection training program as part of an open enrollment trial (see Table 1 for sample demographics). There were no specific eligibility criteria for participation. The program was listed as a state-approved mandated reporter training on the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services website. Other than an initial press release and word of mouth, no active recruitment was carried out (i.e., no mailings, no phone calls). Participants accessed the training program online and provided informed consent prior to filling out registration and proceeding to the learning program. Completion of the online child protection training program conferred 3 hr of professional development credits. The sample for the present analysis was drawn from participants who completed the online modules between January 2014 and March 2015.

Table 1.

Early Childhood Education Provider Characteristics as a Percentage of the Sample.

| ECE Provider Demographics | Phase II (n = 5,379) |

Qualitative (n = 26) |

Phase III (n = 719) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White or Caucasian | 71.4 | n/a | 95.97 | |

| Black or African American | 19.5 | 0.42 | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.4 | 0.28 | ||

| Hispanic | 5.2 | 0.70 | ||

| Asian | 1.6 | 0.70 | ||

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0.1 | 0.28 | ||

| Other | 1.8 | 1.67 | ||

| Education level | ||||

| Below high school | 0.7 | n/a | 0.1 | |

| High school diploma or general equivalency diploma | 31.9 | 35.6 | ||

| Child Development Associate credential | 10.0 | 4.6 | ||

| Associate’s degree | 14.8 | 24.1 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 31.6 | 27.3 | ||

| Advanced degree | 11.0 | 8.3 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 90.5 | 96.2 | 96 | |

| Male | 9.5 | 3.8 | 4 | |

| Age range | ||||

| <18 | n/a | n/a | 0.4 | |

| 18–29 | 39.4 | 31.7 | ||

| 30–44 | 28.8 | 31.8 | ||

| >44 | 31.8 | 36.0 | ||

| Prior mandated reporter training | ||||

| Yes | 74.4 | 88.5 | 49.5 | |

| No | 25.6 | 11.5 | 50.5 | |

| Childcare work setting | ||||

| Home-based | 5.1 | 7.7 | 21.6 | |

| Center-based | 60.1 | 80.8 | 60.0 | |

| Head start facility | 8.7 | 7.7 | 18.4 | |

| Religious facility | 11.2 | 3.8 | 0 | |

| Other | 14.9 | 0 | 0 | |

| Years working as an early childhood practitioner | ||||

| <5 | 50.0 | 7.7 | 40.2 | |

| 6–10 | 18.1 | 19.2 | 16.8 | |

| 11–15 | 11.0 | 3.8 | 14.0 | |

| >15 | 20.9 | 69.2 | 28.9 | |

Instrument

The QUAN I knowledge test was modified from the pilot and consisted of 23 items related to child abuse/neglect and its reporting (see Appendix A for test items). Analysis of the internal consistency for all 23 items indicated low reliability (α = .681), possibly due to violations of a unidimensional assumption in the structure of the test (McDonald, 1999; Rodriguez et al., 2016). Guided by federal definitions of maltreatment (i.e., CAPTA), knowledge was therefore hypothesized to correspond to a three-factor structure comprised of actions by a parent or caretaker, consequences for the child, and mandated reporting duties. Based on this hypothesized structure, items were divided into three subscales that included actions by adults that might constitute child abuse (actions), bruises that might indicate child abuse (bruises), and legal requirements regarding child abuse (legal requirements).

Data analysis.

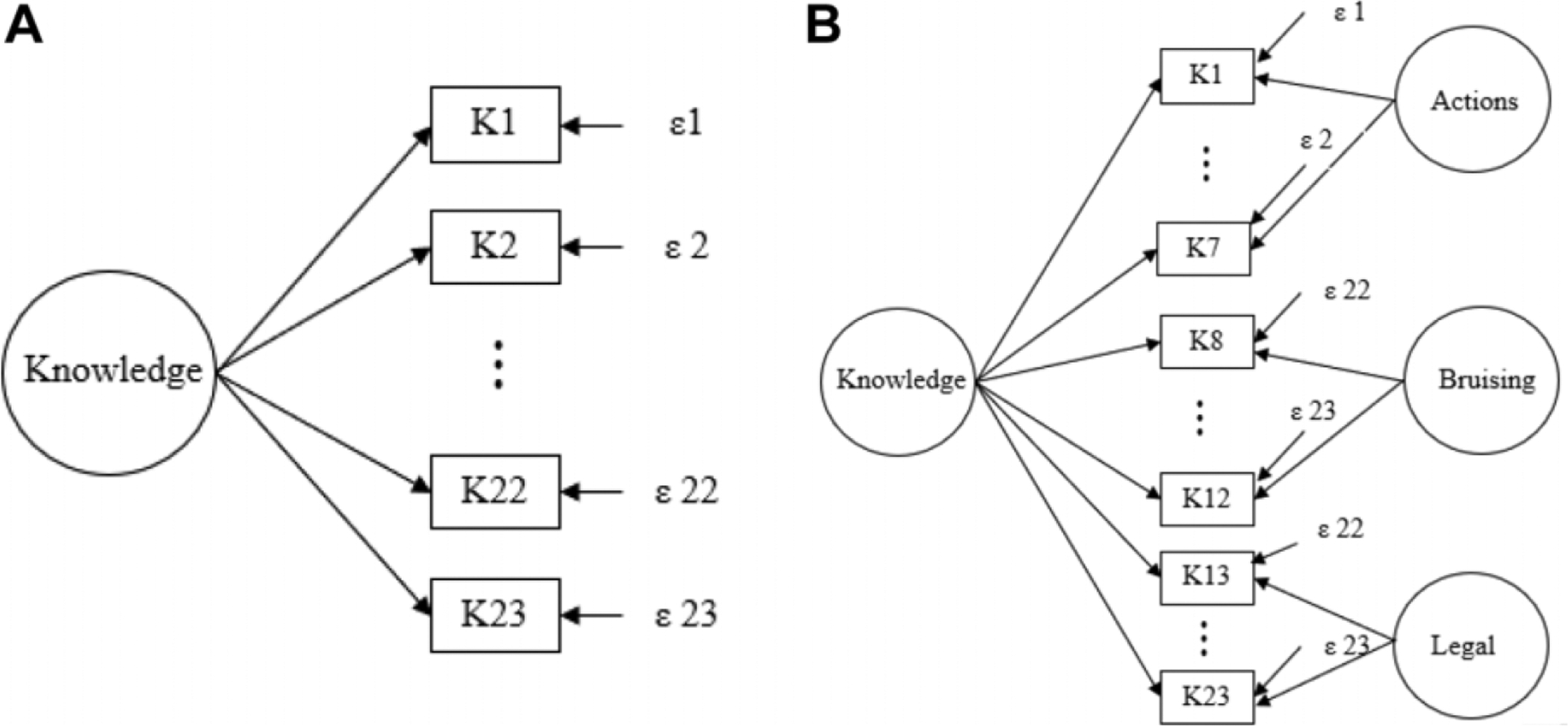

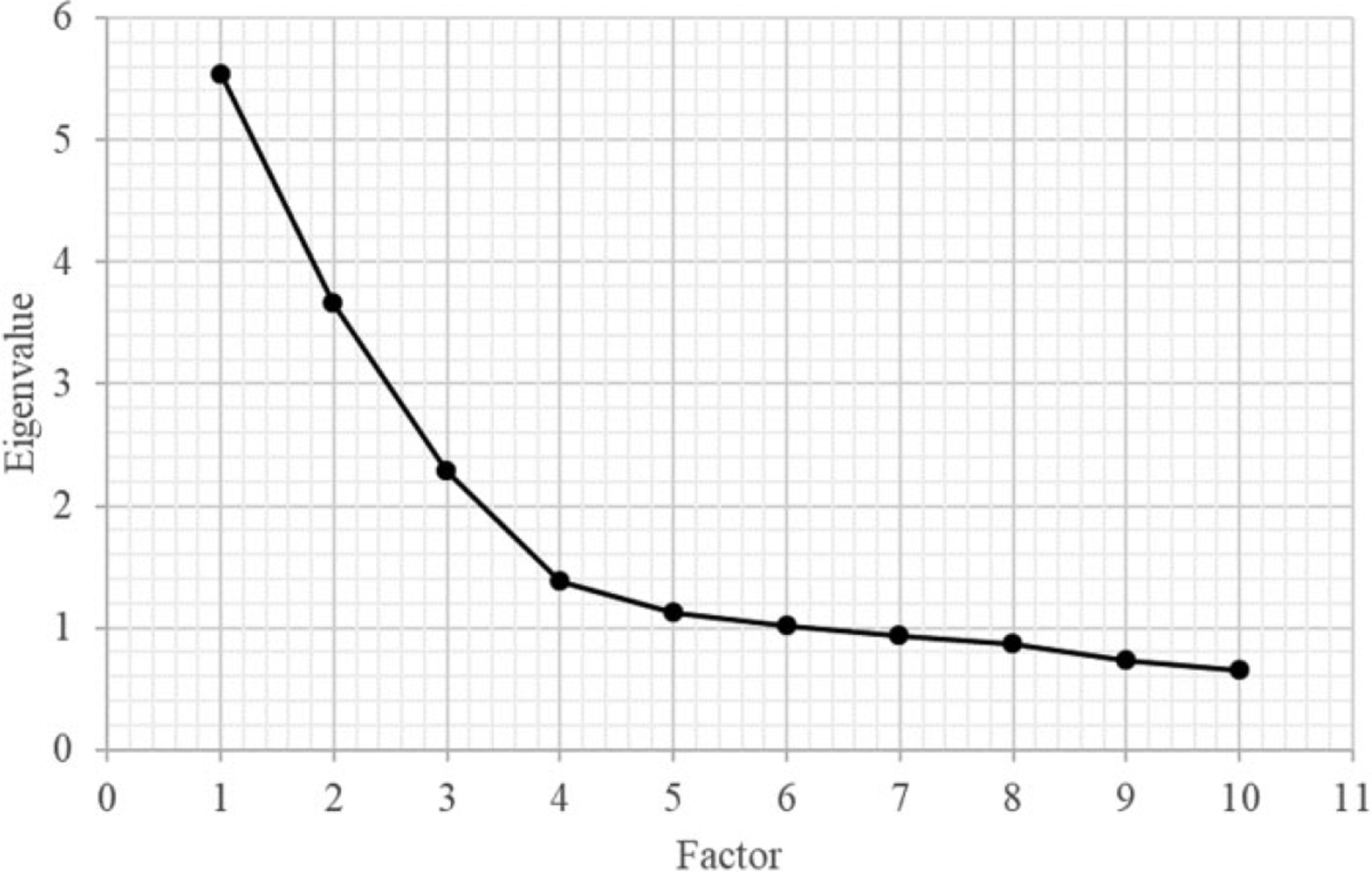

Structural validity was assessed through an unrestricted exploratory factor analysis (EFA) in Mplus Version 8.3 using diagonally weighted least squares estimation given the ordinal nature of the items. Model fit was assessed using root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; ≤.06), comparative fit index (CFI; ≥.95), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR; ≤.08; Hu & Bentler, 1999). A one-factor EFA model using a GEOMIN (OBLIQUE) rotation was initially selected to evaluate whether a unidimensional structure could account for all 23 test items (see Figure 1, Model A). The potential implausibility of a unidimensional model was assessed by examining the scree plot wherein factor solutions with eigenvalues above one were tested. Subsequent multidimensional models were then examined, which included a correlated traits model (i.e., all subscales were correlated) and a bi-factor model. Given that the iLookOut Knowledge Test included item parcels that attempt to capture the complexities surrounding knowledge of child abuse/neglect and its reporting requirements through items that tap into actions, bruises, and legal subscales, it was important to account for these dimensions while assessing a single construct of knowledge.

Figure 1.

Model A represents a one-factor model (i.e., unidimensional model); Model B represents a bi-factor model with a hypothesized general factor (i.e., knowledge) and three group factors (i.e., iLookOut knowledge test subscales).

To this end, an unrestricted bi-factor EFA model using a BI-GEOMIN (ORTHOGONAL) rotation (see Figure 1, Model B) was applied to the data. Bi-factor EFA models allow for simultaneously modeling a single construct of knowledge (i.e., general factor) while accounting for the multi-dimensionality of other latent factors (i.e., group factors). According to Reise et al. (2010), items that load into a general factor “reflects what is common among the items and represents the individual differences on the target dimension that a researcher is most interested in” (p. 546), which in this case was knowledge of mandated reporting. Further, subscales are group factors that “represent common factors measured by the items that potentially explain item response variance not accounted for by the general factor” (Reise et al., 2010, p. 546). Application of a bi-factor EFA model, therefore, provided a less ambiguous interpretation of the summed scores for the knowledge test.

Integration from QUAN I to QUAL.

Internal structure validity evidence gathered from QUAN I was used to inform modifications to the knowledge test prior to the QUAL stage. These modifications were intended to improve conceptual clarity related to test structure and to make the test sufficiently generalizable and readily adapted for use in other states (outside Pennsylvania) without resulting in semantic drift that would undermine its validity. Specific changes included modifications to the response options and the addition of two subscales: signs or behavior that are concerning for child abuse (concerning signs) and legal penalties for failing to report child abuse (legal penalties). The concerning signs subscale included new and revised items designed to measure knowledge about red flags that do not rise to the legal definitions of child abuse/neglect. The other subscale included items that measured knowledge about legal penalties for failing to report suspected child abuse/neglect. The resulting version of the instrument used in the QUAL stage included 26 items total, six for actions, six for bruises, six for concerning signs, five for legal requirements, and three for legal penalties (see Appendix B for test items).

Qualitative Stage (QUAL): Response Process Validity

Participants, procedures, and analyses.

Qualitative data were collected by Research Matters, LLC, who designed and executed a study to conduct cognitive interviews or cognitive laboratories (cognitive labs) using the revised test from QUAN I. Cognitive labs provide insight into comprehension and understanding of test items through participants’ verbal reports as they complete and review the test (Leighton, 2017; Zucker et al., 2004). Cognitive labs help identify test validity concerns by providing “evidence that the cognitive processes being followed by those taking the assessment are consistent with the construct to be measured” (AERA, APA, NCME, 2014, p. 82). Further, cognitive labs have been used by researchers to improve survey instruments in small- and medium-scale evaluation projects (Ryan et al., 2012). The qualitative study involved three rounds of iterative research and revision that took place between January and April 2017. Research was conducted in Pennsylvania, California, and Maine, respectively. The iLookOut project team led the recruitment of 26 ECE providers as study participants across all three sites (see Table 1 for demographics of the study sample). All study participants reported that they were paid employees in a childcare setting. A Research Matters researcher traveled to each site and conducted one-on-one cognitive interviews with each participant using the protocol described above. Each cognitive interview session took between 40 and 60 min.

Research Matters developed a detailed interview guide for data collection from the sample of ECE providers. The knowledge test was administered in five parts to enable the researchers to ask a series of follow-up questions immediately after the respondent completed a set of questions on a topic. The interview included scripted prompts for particular items (e.g., “What does [TERM] mean to you?”) as well as a series of general prompts to use, as needed, to encourage verbal reporting by the respondent (e.g., “Tell me more about that” or “What are you thinking about right now”). An array of cognitive prompts was used to elicit information from respondents, including interpretation probes (e.g., “What does [TERM] mean to you?”), paraphrasing (e.g., “Please repeat the question in your own words”), confidence judgment (e.g., “How sure are you about that answer?”), and recall (e.g., “How did you arrive at your answer?”)

Instrument.

The knowledge test used for cognitive interviews was modified from QUAN I and included 26 items. This QUAL version contained five subscales (see Appendix B for test items) and included edits from Research Matters for improving structure, format, clarity, and comprehensibility of both items and test instructions. Following the first round of cognitive interviews, the study team and Research Matters further revised the instructions and six test items that demonstrated weak response process validity evidence. The second round of cognitive interviews was then conducted with this revised instrument, where qualitative data informed further revisions in test instructions, item wording, and item ordering. This revised instrument was subsequently used in the third and final round of cognitive labs, using the qualitative findings to revise the wording of two items.

Integration from QUAL to QUAN II.

After the final revisions to the knowledge test (following the third round of cognitive labs), an item was removed since Maine does not impose any financial penalties for failing to report suspected abuse. As such, the final version of the knowledge test used in the next quantitative stage (QUAN II) included 25 items across five subscales: actions (six items), bruises (six items), concerning signs (six items), legal requirements (five items), and legal penalties (two items; see Appendix B for test items).

Quantitative Stage (QUAN II): Revised Instrument Structural Validity

Participants and procedures.

Participants for QUAN II were ECE providers (n = 719) from the I-95 corridor of Maine (see Table 1 for demographics) who were at least 18 years old, could read English, and worked (paid or volunteer) at a licensed childcare facility (commercial, noncommercial, home-based, or other) for children <5 years of age. Recruitment letters and emails were sent to the directors of these licensed childcare facilities with instructions for them and their staff on how to access the iLookOut child protection training program online using their program license number. Mailings included a summary explanation of the research, and individual participants provided informed consent after accessing the program website, but before starting the actual learning program. Completing the online program conferred 3 hr of professional development credits and satisfied Maine’s mandated reporter requirement. Participants accessed and completed the online child protection training program between October 2017 and August 2018.

Instrument.

QUAN II employed the revised knowledge test outlined in the second integration after QUAL (see Appendix B for test items). Analysis of the internal consistency for all the items in the revised instrument showed good reliability (α = .73), which was significantly better than the version employed for QUAN I.

Data analysis.

Examination of the structural validity for the revised instrument followed similar procedures outlined in the QUAN I section above. Given the hypothesized models derived from QUAN I and QUAL findings however, a more restrictive bi-factor confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) framework was used instead. Fit indices to assess model quality employed the same criteria from QUAN I, which included RMSEA, CFI, and SRMR. Further, standardized factor loadings of 0.30 and above were used to retain meaningful items (Brown, 2006; McDonald, 1999). Finally, given the complexity inherent in multidimensional constructs, model-based reliability estimates using coefficient omega (ω) and omega-hierarchical (ωH or omegaH) were calculated and compared (Canivez, 2016; McDonald, 1999; Rodriguez et al., 2016). Coefficient ω is an estimate of the internal reliability of the overall multidimensional composite (i.e., estimates the proportion of variance in the observed total score based on the general and group factors) where interpretation is like α that assumes a unidimensional structure. OmegaH on the other hand is more appropriate for a bi-factor structure and estimates the proportion of variance in overall scores attributable to the general factor while considering the variability in orthogonal group factor scores as measurement error (Rodriguez et al., 2016). OmegaH can be calculated by dividing the squared sum of factor loadings on the general factor (i.e., knowledge of mandated reporting) by the model estimated variance of total scores (i.e., all common sources of total score variance plus unique variances attributed to the group factors).

Results

QUAN I Findings From EFAs

Results of the one-factor model indicated poor data-model fit (RMSEA = .09, CFI = .50, SRMR = .17), which challenged the plausibility of a unidimensional construct for knowledge. Analysis of the scree plot (see Figure 2) indicated the potential of extracting five factors due to eigenvalues above 1. Based on this, a five-factor multidimensional model with correlated group factors (i.e., a correlated traits model; Reise et al., 2010) was selected. Results indicated improvement over the unidimensional model (RMSEA = .02, CFI = .98, SRMR = .03). Unfortunately, the selection of a correlated traits model without a common measurement structure (i.e., general factor) made interpretation of subscale scores challenging, given the goal of having a single composite score represent knowledge. To address this concern, a bi-factor EFA model using an orthogonal rotation was applied.

Figure 2.

Scree plot for QUANT I, indicating the potential number of factors to be extracted based on eigenvalues above 1.

The hypothesized three-factor structure was tested by specifying three group factors (i.e., subscales representing actions, bruises, and legal) along with a general factor structure representing knowledge (3 + 1 Model), which yielded good data-model fit (RMSEA = .03, CFI = .97, SRMR = .04). Examination of the factor structure revealed problems wherein only certain items (i.e., 1, 2, 4–6, 8, 10, 12, 13–15, 20, 22, and 23) loaded under the general factor as expected, with factor loadings (λ) ranging from .41 to .59. Items 1–7 loaded on the actions subscale as expected (λ = .56–.77) but with Item 3 (λ = .42) cross-loaded. Only Items 9 (λ = .88) and 11 (=.77) loaded significantly for the bruises subscale, while only Items 13–15 (λ = .73, .70, and .75, respectively) loaded significantly under the legal subscale. These results indicate that interpretation of the 3 + 1 Model as representing respondents’ knowledge of mandated reporting duties may be problematic.

Based on eigenvalues above 1, a five-group factor plus one general factor multidimensional model (5 + 1 Model) was also tested, yielding improved data-model fit (RMSEA = .02, CFI = .99, SRMR = .03) compared with the prior models. This signaled the need to consider increasing the number of subscales from three to five.

QUAL Findings From Cognitive Labs

Across all three cognitive lab sites, respondents reported that they found the introduction clear and easy to understand, the terms familiar, and the use of bullet points and bold type effective in drawing their attention to key terms. Respondents were able to explain their understanding of the types of abuse that were stipulated by the test (e.g., physical abuse, sexual abuse, psychological abuse, neglect, and imminent risk). What follows is a discussion on respondents’ understanding of items from the revised knowledge test across the five subscales.

Subscale 1: Actions by adults that might constitute child abuse.

Although cognitive interviewing revealed that most items were understood as intended, some items did not perform well. For example, the item, impairs physical functioning from disciplining a child, appeared to be problematic for respondents during Rounds 1 and 2 despite evidence for structural validity from QUAN I. As a result, the item was revised prior to Round 3 of cognitive interviews and read, disciplines a child in a way that results in the child having difficulty doing things he or she can typically do, such as walk, sit, talk, etc. This revised wording markedly improved understanding, as evidenced by participants describing the question as being about “physical harm that makes them unable to do those things” and “injuries to the point of swelling or breaking bones or bruising where they can’t sit or do other things kids do.”

Subscale 2: Bruises that might indicate child abuse.

Response process evidence suggested that respondents interpreted the items in this subscale fully as intended. For example, despite weak structural validity evidence from Phase II, the item unexplained bruising in toddler’s shins was interpreted in the context of typical child development. “I work with toddlers … They play rough and they fall a lot. Seems reasonable to have bruises there.” The item dark spots on a child’s lower back that do not change over time was designed to measure respondents’ ability to distinguish common birthmarks from skin markings that might be from abuse. A representative response was “I have had kids who have this, it is part of the pigment of their skin. If it is a bruise, it changes over time. So, this leads me to believe this isn’t bruising.” As intended, the qualifier do not change over time signaled to respondents that the spots are not bruises. However, respondents who focused on the term dark spots speculated that the spots might be a birthmark, natural color variation, or a skin condition but continued to be skeptical about the spot being a bruise. “I am not sure what the dark spots would be caused by. It is unclear whether or not it means bruising.” Following the third round of cognitive labs, the term dark spots was then changed to areas of blue-gray skin to more accurately reflect what Mongolian spots look like.

Subscale 3: Signs or behaviors concerning for child abuse.

Evidence from cognitive labs showed that respondents’ interpretation of test items was more variable when those items included situations that often co-occur with maltreatment (e.g., poverty, intimate partner violence). This suggests the importance of having a clear understanding of statutory definitions for abuse/neglect to avoid conflating it with co-occurring experiences, such as poverty, since neglect involves negligent failure to provide essential needs such as clothing and food (Ca. Welf. & Inst. Code § 300; Me. Stat. Ann. Tit. 22, § 4002; Pa. Cons. Stat. Tit. 23, § 6303). For example, some respondents appeared to struggle with the item, consistently is dirty, has bad body odor, and is inadequately dressed for the weather. “It is difficult based on my experiences with families who have hard times. Mom could be trying her best but I gotta (sic) go toward yes. It is neglect if it happens regularly.” Response process evidence did show that qualifiers such as “consistently” or “always” helped respondents reflect on and critically analyze the items but continued to remain unsure. “Consistently makes me think … the behavior hasn’t changed. I would not report until I had talked with the family. It could be neglect or it could be a poor family that doesn’t have resources. I am unsure about whether it should be reported.”

Respondents also struggled to interpret the item that involved intimate partner violence (physically abuses their partner in the presence of a child), which also showed weak structural validity evidence in QUAN I. Although there is a high co-occurrence of child abuse/neglect with domestic violence (Lawson, 2019), most states (with the exception of West Virginia and Montana) do not explicitly include the terms “domestic violence” or intimate partner violence in their legal definition of abuse/neglect (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2014). Even after the item was reworded (witnesses intimate partner violence such as a parent, caregiver, or other adult physically abusing his/her partner), many respondents continued to conflate witnessing intimate partner violence with abuse/neglect. “The child witnesses it … yes. It’s pretty clear, child would be in danger eventually … in danger of being physically abused” or “Yes, it is psychological abuse for the child to see this.”

Subscale 4: Legal requirements regarding child abuse.

In the early rounds of cognitive labs, items that involved legal requirements were reported as the hardest to interpret. For example, for the item, you are only required to report suspected child abuse if a parent or caregiver intended to harm the child, one respondent answered correctly, but did so because they thought that the word “only” was being linked to “parent or caregiver” (rather than the word “intended”). “Because we are required to report no matter who it is.” Several respondents did not notice the word only, and answered incorrectly, while others had to reread the question a few times before realizing the presence of this qualifier. To make the wording less “tricky” (as some described it), this item was revised to read, you are required to report suspected abuse only if the person’s behavior intended to harm the child—which helped respondents interpret the item as intended.

The item that asked, under Pennsylvania law, are you required to report suspected child abuse/neglect if a child was put at significant risk for being injured even when no injury or harm actually occurred? was reworded to accommodate statutes outside Pennsylvania. Further revisions were conducted after Round 1 of the cognitive labs to improve item understanding and evidence appeared to indicate that respondents understood the item as intended (e.g., “True. Significant risk. Similar to imminent harm—something that put a child in harms [sic] way and by luck, nothing happened;” “True. Next time they may not miss. There is potential for abuse to occur so you have to report”).

Subscale 5: Legal penalties for failing to report child abuse.

The three items in the legal penalties subscale were short statements that used common language and showed strong structural validity evidence from QUAN I. Respondents indicated that these items were “straightforward” and “very clear,” and most spent little, if any, time reflecting on their meaning. Accordingly, neither the instructions nor any of the items were revised as a result of the cognitive lab data.

QUAN II Findings on the Revised Knowledge Test From the QUAL Stage

Results of the one-factor CFA model for QUAN II data indicated poor fit for the unidimensional model (RMSEA = .06, 95% CI [0.05, 0.06], CFI = .71, SRMR = .14). Based on the hypothesized factor structure derived from the previous QUAN and QUAL stages, a correlated group factors (i.e., correlated traits model with five factors) CFA and multidimensional bi-factor CFA models were subsequently tested. Findings from the correlated group factors CFA model showed improvements over the unidimensional model but still indicated poor data-model fit (RMSEA = .05, 95% CI [0.04, 0.05], CFI = .82, SRMR = .11).

Prior to fitting the bi-factor models, factor variance was constrained to 1.0 to ensure model identification (Reise et al., 2010). Specification of a hypothesized 5 + 1 CFA Model resulted in nonconvergence and may be attributable to a violation of bi-factor modeling assumptions. Specifically, Reise and colleagues (2010) stated that bi-factor models, in addition to the assumption of orthogonality, must contain at least three items that load on a general factor and only one group factor. Examination of the subscales showed that legal penalties only included two items, potentially violating this assumption. Therefore, an alternate 4 + 1 CFA Model was specified wherein all items under legal requirements and legal penalties were combined under a single subscale called legal.

The 4 + 1 CFA Model converged but yielded poor data-model fit (RMSEA = .04, 95% CI [0.03, 0.04], CFI = .88, SRMR = .10) and included several warnings about one or more zero cells in the bivariate table involving Item 22 in relation to other items. A respecification of the 4 + 1 CFA Model, which excluded Item 22, resulted in model convergence without any subsequent error messages. The model yielded adequate fit (RMSEA = .03, 95% CI [0.02, 0.03], CFI = .95, SRMR = .08) with no further respecifications needed for a modification index of 3.84. Therefore, this respecified 4 + 1 CFA Model was retained as a viable representation of the underlying bi-factor structure for knowledge of mandated reporting. Examination of the factor structure for the 4 + 1 Model indicated that most of the items loaded onto the general factor of knowledge as hypothesized (see Table 2), with the exception of Items 21 (λ = .18), 23 (λ = .18), and 24 (λ = .28). In terms of the group factors, most items loaded onto the hypothesized subscales with the exception of the following: Item 3 (λ = .18) for action, Item 9 (λ = .18) for bruises, Item 16 (λ = .18) for concerning signs, and Items 21 (λ = .18), 27 (λ = .18), and 28 (λ = .18) for legal.

Table 2.

Factor Loadings for QUANT II Bi-Factor Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model With Uncorrelated Group Factors.

| 4 + 1 Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item Set | Item | K | G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 |

| Actions (G1) | 1 | .34 | .76 | |||

| 2 | .35 | .84 | ||||

| 3 | .37 | — | ||||

| 4 | .43 | .59 | ||||

| 5 | .41 | .64 | ||||

| 6 | .46 | .62 | ||||

| Bruises (G2)$ | 7 | .50 | .30 | |||

| 8 | .43 | .45 | ||||

| 9 | .50 | — | ||||

| 10 | .46 | .30 | ||||

| 11 | .42 | .66 | ||||

| 12 | .51 | .56 | ||||

| Concerning signs (G3) | 14 | .52 | −.33 | |||

| 15 | .66 | −.41 | ||||

| 16 | .61 | — | ||||

| 17 | .34 | .67 | ||||

| 18 | .38 | .50 | ||||

| 19 | .46 | −.31 | ||||

| Legal (G4)$ | 20 | .30 | .42 | |||

| 21 | — | — | ||||

| 23 | — | .38 | ||||

| 24 | — | .51 | ||||

| 27 | .41 | — | ||||

| 28 | .40 | — | ||||

Note. Only standardized factor loading (λ) values ≥ |.30| are reported. K = knowledge; G = group factor.

Model-based internal consistency for the overall composite score was high (ω = .90). Given the hypothesized multidimensional structure, however, calculation of the model-based omegaH was lower than omega but well within the acceptable range (ωH= .72). According to Rodriguez et al. (2016), this omegaH value meant that 72% of the variance in unit-weighted total score was attributable to the general factor. The comparison between omega and omegaH (i.e., relative omega calculated as ωH/ω) further indicated that 80% of the reliable variance in the total knowledge score was assumed to reflect individual differences in the general factor of knowledge, with 18% (i.e., ω − ωH) attributable to the group factors inherent in the multidimensional structure of the instrument. Moreover, examination of omegaH for each subscale, where variance from the general factor was partitioned out, indicated significantly reduced reliability estimates (action = .63, bruises = .33, concerning signs = .00, and legal = .36) as expected. Taken together, acceptable values for omegaH and low reliability for omegaH subscales signify that individual differences in knowledge of mandated reporting were mostly due to the general factor rather than the group factors. That is, the total raw score of the iLookOut Knowledge Test can be interpreted as plausibly unidimensional despite the inclusion of subscales.

Discussion

Validity evidence gathered across content, response process, and internal structure provided pre-liminary support for the adequacy and appropriateness of interpreting the aggregated score (excluding Items 21, 23, and 24) for the iLookOut Knowledge Test as representing knowledge of child abuse and mandated reporting (AERA, APA, NCME, 2014; Messick, 1989a). In terms of content-related validity evidence, use of child welfare law experts, ECE undergraduate students, and full-time ECE providers in PA during the pilot study provided insight into how test items aligned with the standards reflected in the federal definition of child abuse (i.e., CAPTA).

An iterative revision process (outlined below) provided insight for the first research question, “To what degree does the iLookOut Knowledge Test reflect the dimensionality inherent in the definitional construct of child abuse and neglect?” More specifically, results from the EFA in QUAN I and the CFA from QUAN II provided evidence that unidimensional and correlated traits models were not appropriate structures for the knowledge test. Despite a multidimensional structure based on federal definitions of abuse, the bi-factor models, along with omega reliability estimates, indicated that a general factor (i.e., knowledge) can adequately represent the construct as hypothesized, while accounting for the variance from group factors (i.e., subscales). This means that assigning a point for the significant items and summing across (excluding Items 21, 23, and 24) to arrive at a total test score can provide inference about ECE providers’ knowledge of child abuse, where higher scores indicate better knowledge in this domain. This scoring template is in line with other researchers who have aggregated test scores to represent knowledge about mandated reporting, which were subsequently used to evaluate training effectiveness (Carter et al., 2006; Kenny, 2007; Mathews et al., 2017; McKee & Dillenburger, 2012).

Cognitive labs were used to answer the second research question that asked, “How do ECE providers from different states (i.e., statutory differences in child abuse definitions) interpret items on the iLookOut Knowledge Test?” Response processes during the QUAL stage showed evidence that ECE providers across PA, ME, and CA understood the instructions for the test and were able to report on their interpretation of each subsequent test item. Where appropriate, barriers to understanding were documented and modified to ensure that test items were understood as intended. Despite the potential for semantic drift given statutory differences across the three different states represented by the participants, we found evidence that respondents understood the items as intended. To our knowledge, this is the only study to employ cognitive labs methodology to collect response process validity evidence for a child abuse knowledge test in a sample of ECE providers. Despite paucity of similar research in the field of child abuse, however, findings from our study are in line with others who employed cognitive labs to gather response process validity evidence in graphic literacy (Langenfeld et al., 2020), mathematics (Winter et al., 2006), and science inquiry (Dickenson et al., 2013).

Finally, guided by Messick’s (1989a) unified validity framework, the different sources of validity evidence outlined above were integrated in an iterative manner across different stages of our mixed methods study to answer the final research question, “To what extent do the quantitative structural assessment and qualitative interpretation results provide overlapping evidence on items that need to be revised in order to improve instrument validity?” Specifically, poor performing items from the EFA in QUAN I were examined more closely during the cognitive labs in the QUAL stage to modify any barriers to understanding. Divergent responses drawn from the QUAL stage were revised, and results were subsequently integrated into QUAN II to further evaluate the internal structure of the revised instrument. According to the Standards, “a sound validity argument integrates various strands of evidence into a coherent account of the degree to which existing evidence and theory support the intended interpretation of test scores …” (AERA, APA, NCME, 2014, p. 21). The Standards further stipulate that the amount and quality of evidence to support a provisional judgment of validity varies by the area of research and the stakes involved, that is, higher stakes testing requires higher standards of evidence. Given the important preventive effects of mandated reporting therefore, evaluation of training effectiveness should include measures that have higher quality evidence of validity. Our study contributes to this dearth of available information by undergoing integration of validity evidence using a mixed methods approach. A more detailed discussion of this iterative revision process is therefore provided in the next section.

Using Mixed Methods to Integrate Findings

Results from QUAN I showed weak evidence for structural validity of the overall knowledge test and its hypothesized subscales. Building from these results, the knowledge test structure and items were revised, and response process validity evidence was collected prior to reexamining structural validity evidence for the modified test. The joint display in Table 3 highlights several exemplars of validity evidence from the iterative findings across both quantitative and qualitative stages of the study. First, cognitive labs from the qualitative stage of the study provided valuable insight into respondents’ understanding of items, particularly those showing weak structural validity evidence from the initial EFA from QUAN I of the study. This in turn informed how the inclusion of qualifiers, rewording of items, and restructuring of subscales improved the overall structural validity of the iLookOut Knowledge Test—which is demonstrated by the improved overall structure from QUAN II findings.

Table 3.

Integrated Findings for Exemplars of Validity Evidence Across Explanatory (QUAN I → qual) and Exploratory (QUAL → quan II) Stages.

| Subscales | Item Text | QUAN I EFA | Problem | Cognitive Interview Quotes (QUAL) | Problem | QUAN II EFA | Problem | Meta-inferences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actions | Causes any kind of physical injury to a child | .05 | Y | “Yes, physical injury is what it implies. Harm in any way, shape, or form is abuse.” | Y | .37 | N | Qualifiers and rewording of items helped respondents understand the items as intended |

| Bruises | Unexplained bruising on a toddler’s shins | −.09 | Y | “I work with toddlers. They are monkeys. They play rough and they fall a lot Seems reasonable to have bruises there.” | N | .42 | N | Improved validity may be due to restructuring of items and respondents thought critically through the question as intended |

| Concerning signs | Consistently dirty, has bad body odor, and is inadequately dressed for the weather | n/a | n/a | “I would not report until I had talked with the family. It could be neglect or it could be a poor family that doesn’t have resources. I am unsure about whether it should be reported. I am unsure.” | Y | .52 | N | Results indicated that respondents took pause when answering questions in this set This appeared to indicate the need to reflect on questions more closely in order to engage in more critical analysis of the scenarios. |

| Legal requirements | You are only required to report suspected child abuse if a parent or caregiver intended to harm the child | .11 | Y | “We are required to report no matter who it is” “Wording was tricky.” |

Y | .18 | Y | This item set appeared to be the most problematic. Despite modifications and some evidence that respondents understood the questions, the general factor did not hold. Interpretation of this set as indicative of mandated reporting knowledge may continue to be problematic. |

| When a parent has put their child at significant risk of injury, but no injury or harm actually occurred, you are still required to report suspected child abuse to child protective services… | .50 | N | “Significant risk Similar to imminent harm—something that put a child in harms (sic) way and by luck nothing happened.” “Next time they may not miss. There is potential for abuse to occur so you have to report” |

Y | Convergence problem | Y | Despite evidence for structural validity from QUAN I, there were problems that persisted across QUAL and QUAN II. Interpretation of the keyword “significant risk” may prove problematic as respondents appeared to engage in conjecture and thinking beyond the available information in the question stem |

Note. General factor (i.e., knowledge) represented in the table with loading () values ≥ |.30| considered significant for the study. EFA = exploratory factor analysis.

Second, evidence from cognitive labs showed that several items (particularly within the concerning signs subscale) required respondents to engage in more critical analysis to discern their intended meaning. This is not particularly surprising given the complexity of child abuse/neglect as a social problem (Stone, 2019) and the attendant social complexities of recognizing and reporting suspected maltreatment. So, too, state laws regarding mandated reporting policies can exhibit wide variation in both substance and interpretation (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2014). The significant variability that has been shown among ECE providers (Levi et al., 2015) highlights the importance of having well-designed evidence-based interventions to improve mandated reporters’ knowledge and judgment. Accordingly, we regard it as a positive sign that respondents took pause to think through some items more carefully and consider the complexities regarding their mandated reporting responsibilities, for example, disentangling effects of poverty versus concerns about failure to provide (i.e., physical neglect).

Third, evidence from the qualitative stage of the study indicated that the legal requirements subscale was the most difficult item set to answer despite changes in wording. This was further confirmed with quantitative results from the CFA during QUAN II, specifically for Item 22 (… put their child at significant risk of injury, but no injury or harm actually occurred, you are still required to report …), which resulted in model convergence problems. This may be due to the structure of the question stem, which was potentially cumbersome for respondents. According to Roe (2008), question stems should be created to be as succinct as possible, avoiding long and wordy structures that include definitions and examples. Upon examination of the length and complexity of all the questions throughout the knowledge test, Item 22 was the longest at 350 characters and included the definition for, and examples of, significant risk. Further complications in understanding this item appeared to be related to respondents’ framing of significant risk as imminent harm or potential for harm. This is a particularly salient concern given how risk levels and child abuse definitions vary by state. For example, only Vermont (Ann. Stat. Tit. 33, § 4912) explicitly includes the words significant risk, whereas nine states (CT, ME, MT, NJ, NY, OK, WA, WV, and WY), the District of Columbia, and CAPTA at the federal level include the word imminent risk or danger in the definition of child abuse (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2016). Given that this subscale pertains to items that measure legal requirements, definitional incongruency between the statute and item wording may be increasing cognitive load that depletes working memory (Chen et al., 2018) for respondents as they switch between definitions. This, in turn, may divide respondents’ attention away (Lee & Lee, 2011) from considering the intended meaning of the item and its subsequent interpretability.

Fourth, despite evidence for response process validity and improved internal structure for the revised knowledge test during QUAN II, several items did not load on the general factor as expected. Items 21–24, which fall under the legal requirements subscale, appear problematic and may potentially be due to statutory variability in child abuse/neglect definitions (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2016). More specifically, these items inquire about respondents’ understanding of reporting thresholds that influence decisions to report suspected child abuse. Mandated reporting laws make it explicitly clear that ECE providers are required to report suspected child abuse (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2019). However, there is no clear guidance on what the standards are that constitute suspicion within each state. This is especially concerning considering a study where child abuse experts in research and practice are not in agreement on the threshold for reporting suspected child abuse (Levi & Crowell, 2011).

Finally, structural validity evidence from QUAN II indicated that the iLookOut knowledge test should not be broken down into subscales. Rather, results from the bi-factor model point to the plausibility that a single construct representing knowledge of mandated reporting duties is represented by the items that significantly loaded onto the general factor. Indeed, according to Reise and colleagues (2010), “to the degree that the items reflect primarily the general factor and have low loadings on the group factors, subscales make little sense” (p. 555). This means that when all test items (except for Items 21, 23, and 24) are aggregated or summed, higher scores on the iLookOut Knowledge Test indicate better knowledge on mandated reporting requirements.

Contributions, Limitations, and Future Directions

Integration of validity evidence using mixed methods employed in the current study contributed to our understanding that iterative and rigorous validation procedures are important to ensure confidence in the effectiveness of child protection training programs for ECE providers. That is, by collecting ongoing validity evidence for evaluation instruments across different states, our study demonstrated how researchers can understand and account for measurement error and show that program effectiveness was due to intervention effects. This addresses an important future direction in evaluation research posed by Azzam and Jacobson (2015) wherein evaluators need to partner with researchers and increase the availability and utility of common measures to facilitate meta-analyses across evaluations or secondary analyses. According to Azzam and Jacobson (2015), data aggregation that uses similar measures across contexts (i.e., controlling for semantic drift) makes it more feasible for evaluators to attribute variability in outcomes based on context or program effects “rather than differences in measurement error” (Azzam & Jacobson, 2015, p. 109).

The iterative process of test revision is important to ensure that the instrument is still measuring the intended construct. Threats to validity may arise due to semantic drift resulting in alterations to the construct of interest, which in this case is knowledge of child abuse and mandated reporting practices. From the current study, this can be seen when project implementation moved from one state to another and the underlying framework for defining child abuse changes (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2016). An important contribution from the current study, therefore, was the framework and guidance provided on how to engage in such an iterative process for test revision using mixed methodology.

A potential limitation of our study was the difference in demographic characteristics of ECE providers across QUAN I and QUAN II stages. Specifically, the QUAN I Pennsylvania sample included a more diverse sample of ECE providers relative to the QUAN II Maine sample. It is not clear whether such disproportional samples influenced the overall test and item performance. Such a limitation is particularly important to consider within an equity lens given the disproportionality inherent in the child welfare system where African-American children make up over 20% of substantiated victims despite only comprising about 13% of the overall U.S. population (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2019). Attempts at increasing ECE provider knowledge about child abuse and neglect, therefore, should also attend to subjective perceptions of items across contexts (as exemplified in our qualitative approach) that go above and beyond quantitative analyses.

This gets at the main issue of fairness in testing that may be a threat to a fair and valid interpretation of the iLookOut Knowledge Test scores (AERA, APA, NCME, 2014). Given evidence for internal structure at the conclusion of QUAN II, it is therefore important that future work examine how respondent characteristics (e.g., gender, race, educational attainment, socioeconomic status, language) might influence test performance. Within a CFA framework, internal structure evaluation should include differential item functioning to examine the potential for measurement bias, for example, using multigroup factor analysis (Barendse et al., 2012) or item response theory (Panlilio et al., 2019).

Implications

Child protection training programs represent an important public health response to maltreatment prevention, with ECE providers being in a pivotal role to provide safety and security for children in their classrooms who may be at risk of child abuse/neglect. Therefore, evaluation of child protection training programs must exhibit effectiveness in increasing ECE knowledge about mandated reporting practices. Employing valid instruments to assess such knowledge is necessary. Findings from our study offer evidence that the iLookOut Knowledge Test can be a viable tool that ECE providers can use to assess prior knowledge of maltreatment and mandated reporting requirements, as well as a postintervention measure of program effectiveness. As a stand-alone instrument, this knowledge test can be an important evaluation tool that practitioners and administrators can employ in order to collect data and examine changes in ECE provider knowledge about mandated reporting practices after participating in a mandated reporter training program. Considering the results of our study, however, use of the iLookOut Knowledge Test should exclude legal requirements given statutory variability in mandatory reporting. Instead, a separate legal section should be included, which would reflect the state in which the training is held.

From a policy perspective, our study addresses a call by the Institute of Medicine and National Research Council (2014) that highlights the need for increasing policy-related research related to “mandatory reporting” and “education of potential child abuse and neglect reporters” (p. 353). Policies surrounding mandatory reporting programs lack evidence to support its effectiveness, particularly around changes that broaden the scope or definition of maltreatment and the means by which to assess the likely consequences of such changes. By employing a validated instrument to evaluate child protection training programs, policy-related evaluation research can begin to look at how education programs can potentially decrease false positive reports and increase accuracy of reporting to ensure that the families who are at most risk receive the services they need to become more successful. This latter point is particularly important to consider in the context of reimagining the role of the child welfare system to move beyond protection and promote increased attention to well-being (Daro & Donnelly, 2015). This means that future training programs and assessment instruments should include a holistic consideration of the causes and consequences of maltreatment to deliver more effective prevention programs and ensure the equitable distribution of resources.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our sincerest gratitude to Dr. Matt McCrudden, Dr. John Creswell, Dr. Lauren Jodi Van Scoy, and Penn State’s Qualitative and Mixed Methods Core for providing us with invaluable feedback and guidance on this article. You guys rock!

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers 5R01HD088448-04 and P50HD089922) and the Social Science Research Institute at The Pennsylvania State University.

Appendix A

Table A1.

iLookOut Knowledge Test Items From QUAN I.

| Item # | Question Stem |

|---|---|

| Actions by adults that might constitute child abuse | |

| You are required by Pennsylvania law to report suspected child abuse when a parent, caregiver, or other adult does which of the following: | |

| 1 | Physically restrains a child by locking them in a closet |

| 2 | Places duct tape over a child’s mouth as a form of punishment |

| 3 | Causes any kind of physical injury |

| 4 | Causes substantial pain from disciplining a child |

| 5 | Impairs physical functioning from disciplining a child |

| 6 | Forcefully slaps a child under one year of age |

| 7 | Physically abuses their partner (also known as domestic violence) in the presence of a child |

| Bruises that might indicate child abuse | |

| Which of the following kinds of bruising should be reported as suspected child abuse situations: | |

| 8 | Any bruising in an infant who has not started pulling to stand |

| 9 | Any bruising in a toddler or preschooler |

| 10 | Any bruising from spanking |

| 11 | Unexplained bruising on a toddler’s shins |

| 12 | Unexplained bruising on a toddler’s ears |

| Legal requirements regarding child abuse | |

| 13 | Financial penalty |

| 14 | Loss of professional license |

| 15 | Spend time in prison |

| 16 | Under Pennsylvania law, to count as child abuse/neglect, an act (or failure to act) must be committed: intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly |

| 17 | Under Pennsylvania law, you can be held legally liable if you suspect child abuse/neglect and report it, but it turns out to be unfounded |

| 18 | Under Pennsylvania law, once you have “reasonable cause to suspect” child abuse/neglect, you are required to report it:

|

| 19 | Under Pennsylvania law, you must report:

|

| 20 | Pennsylvania law requires you to report suspected child abuse/neglect to: (check one)

|

| 21 | Under Pennsylvania law, to count as physical abuse, it must result in a child experiencing:

|

| 22 | Under Pennsylvania law, are you required to report suspected child abuse/neglect if a child was put at significant risk for being injured even when no injury or harm actually occurred? |

| 23 | Under Pennsylvania law, suspected physical child abuse or neglect must be reported if it occurred “recently.” What period of time counts as recent?

|

Note. Response options vary between 3-point scales (i.e., yes, no, unsure) to 6-point nominal scales (see response options in bullet format above).

Appendix B

Table B1.

Revised iLookOut Knowledge Test Items From QUAL and QUAN II.

| Item # | Question Stem |

|---|---|

| Actions by adults that might constitute child abuse | |

| When answering the questions that follow, assume that the information provided is all that is available. Based only on this information, you must decide whether to report suspected abuse | |

| Please indicate whether STATE LAW REQUIRES childcare providers to report to Child Protective Services each of the following as suspected child abuse. When a parent, caregiver, or other adult: | |

| 1 | Physically confines a child by locking him/her in a closet |

| 2 | Places duct tape over a child’s mouth for being too loud |

| 3 | Causes any kind of physical injury to a child |

| 4 | Causes a child substantial pain from disciplining him/her |

| 5 | Disciplines a child in a way that results in the child having difficulty doing things he or she can typically do, such as walk, sit, talk, and so on |

| 6 | Forcefully slaps a child under one year of age |

| Bruises that might indicate child abuse | |

| When answering the questions that follow, assume that the information provided is all that is available. Based only on this information, you must decide whether to report suspected abuse | |

| Please indicate whether childcare providers SHOULD REPORT to CPS each of the following as suspected child abuse | |

| 7 | Any bruising on an infant who has not started pulling to stand |

| 8 | Any bruising on a toddler’s forehead |

| 9 | Any bruising from spanking |

| 10a | Dark spots on a child’s lower back that do not change over time |

| 11 | Unexplained bruising on a toddler’s shins |

| I2 | Unexplained bruising on a toddler’s ears |

| Signs or behaviors that are concerning for child abuse | |

| When answering the questions that follow, assume that the information provided is all that is available. Based only on this information, you must decide whether to report suspected abuse | |

| Please indicate whether each of the following scenarios raises enough of a concern for suspected child abuse that it SHOULD BE REPORTED to CPS by childcare providers. The child: | |

| 14 | Consistently is dirty, has bad body odor, and is inadequately dressed for the weather |

| 15 | Is always hungry and often found stuffing food in his/her pockets to take home |

| 16 | Witnesses intimate partner violence (such as a parent, caregiver, or other adult physically abusing his/her partner) |

| 17 | Always wears mismatched clothing, and has hair that isn’t combed or brushed |

| 18 | Is consistently very demanding of attention and affection, and is often very clingy |

| 19 | Repeatedly plays make-believe that includes drug use and violence toward animals |

| Legal requirements regarding child abuse | |

| For each of the following statements, indicate if it is True or False under your state’s law. | |

| 20 | If you report suspected child abuse to CPS and it turns out that no child abuse has occurred, you could be subject to a legal penalty |

| 21b | You are only required to report suspected child abuse if a parent or caregiver intended to harm the child |

| 22 | When a parent has put their child at significant risk of injury, but no injury or harm actually occurred, you are still required to report suspected child abuse to CPS. (By “significant risk,” we mean things like leaving a sleeping infant alone in a locked car for 30 minutes, or a parent who is angry throws an empty glass at their child but misses.) |

| 23 | You are only required to make a report of suspected child abuse to CPS if you have evidence that a child has been abused |

| 24 | For an incident to qualify as sexual abuse, the child must have been physically touched |

| Legal penalties for failing to report child abuse | |

| Under your state’s law, if you knowingly and willfully fail to report suspected child abuse to CPS, which of the following penalties might you face? | |

| 26c | Pay a fine |

| 27 | Lose your professional license |

| 28 | Spend time in prison |

Note. Response options have been modified to be consistent across items and are on a 3-point scale (i.e., yes, no, unsure).

Item wording was changed for QUAN II from “Dark spots … ” to “Areas of blue-gray skin ….”

Item wording was changed for QUAN II from “You are only required to report suspected child abuse if … ” to “You are required to report suspected child abuse only if ….”

Item was not included in QUAN II because it was not specified in Maine’s statutes.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, National Council on Measurement in Education, and Joint Committee on Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (U.S.). (2014). Standards for educational and psychological testing. American Educational Research Association. [Google Scholar]

- Azzam T, & Jacobson MR (2015). Reflections on the future of research on evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation, 148, 103–116. 10.1002/ev.20160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barendse MT, Oort FJ, Werner CS, Ligtvoet R, & Schermelleh-Engel K (2012). Measurement bias detection through factor analysis. Structural Equation Modeling, 19(4), 561–579. 10.1080/10705511.2012.713261 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braverman MT (2012). Negotiating measurement: Methodological and interpersonal considerations in the choice and interpretation of instruments. American Journal of Evaluation, 34(1), 99–114. 10.1177/1098214012460565 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Canivez GL (2016). Bifactor modeling in construct validation of multifactored tests: Implications for multi-dimensionality and test interpretation. In Schweizer K & DiStefano C (Eds.), Principles and methods of test construction: Standards and recent advancements (pp. 247–271). Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Carter YH, Bannon MJ, Limbert C, Docherty A, & Barlow J (2006). Improving child protection: A systematic review of training and procedural interventions. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 91, 740–743. 10.1136/adc.2005.092007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen O, Castro-Alonso JC, Paas F, & Sweller J (2018). Extending cognitive load theory to incorporate working memory resource depletion: Evidence from the spacing effect. Educational Psychology Review, 30(2), 483–501. 10.1007/s10648-017-9426-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Reauthorization Act. (2010). P.L. 111–320, 42 U.S.C. 5101 § 3.

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2014). Domestic violence and the child welfare system. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/factsheets/domestic-violence/ [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2016). Definitions of child abuse and neglect. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/define.pdf#page=5&view=Summaries%20of%20State%20laws [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2019). Mandatory reporters of child abuse and neglect. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/manda.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, & Plano Clark VL (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Daro D, & Donnelly AC (2015). Reflections on child maltreatment research and practice: Consistent challenges. In Daro D, Cohn Donnelly A, Huang L, & Powell B (Eds.), Advances in child abuse prevention knowledge. Child maltreatment (Contemporary issues in research and policy (Vol. 5). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-16327-7_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickenson TS, Gilmore JA, Price KJ, & Bennett HL (2013). Investigation of science inquiry items for use on an alternate assessment based on modified achievement standards using cognitive lab methodology. The Journal of Special Education, 47(2), 108–120. 10.1177/0022466911414720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SE, Levitt P, & Nelson CA III. (2010). How the timing and quality of early experiences influence the development of brain architecture. Child Development, 81(1), 28–40. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01380.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Kemp A, Thoburn J, Sidebotham P, Radford L, Glaser D, & MacMillan HL (2009). Child maltreatment 2: Recognising and responding to child maltreatment. The Lancet, 373, 167–180. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61707-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinnell RM, Gabor P, & Unrau YA (2012). Program evaluation for social workers: Foundations of evidence-based programs (6th ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. (2014). New directions in child abuse and neglect research. National Academies Press. 10.17226/18331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ, & Turner LA (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2), 112–133. 10.1177/1558689806298224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones Harden B, Buhler A, & Parra LJ (2016). Maltreatment in infancy: A developmental perspective on prevention and intervention. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17(4), 366–386. 10.1177/1524838016658878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny MC (2007). Web-based training in child maltreatment for future mandated reporters. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(6), 671–678. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenfeld T, Thomas J, Zhu R, & Morris CA (2020). Integrating multiple sources of validity evidence for an assessment-based cognitive model. Journal of Educational Measurement, 57(2), 159–184. 10.1111/jedm.12245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson J (2019). Domestic violence as child maltreatment: Differential risks and outcomes among cases referred to child welfare agencies for domestic violence exposure. Children and Youth Services Review, 98, 32–41. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.12.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, & Lee H (2011). Divided attention facilitates intentional forgetting: Evidence from item-method directed forgetting. Consciousness and Cognition, 20(3), 618–626. 10.1016/j.concog.2010.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighton J (2017). Using think-aloud interviews and cognitive labs in educational research. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levi BH, Belser A, Kapp K, Verdiglione N, Mincemoyer C, Dore S, Keat J, & Fiene R (2019). iLookout for child abuse: Conceptual and practical considerations in creating an online learning programme to engage learners and promote behaviour change. Early Child Development and Care, 1–10. 10.1080/03004430.2019.1626374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi BH, & Crowell K (2011). Child abuse experts disagree about the threshold for mandated reporting. Clinical Pediatrics, 50(4), 321–329. 10.1177/0009922810389170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi BH, Crowell K, Walsh K, & Dellasega C (2015). How childcare providers interpret ‘reasonable suspicion’ of child abuse. Child & Youth Care Forum, 44(6), 875–891. 10.1007/s10566-015-9302-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews B, Yang C, Lehman E, Mincemoyer C, Verdiglione N, & Levi B (2017). Educating early childhood care and education providers to improve knowledge and attitudes about reporting child maltreatment: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One, 12(5), e0177777. 10.1371/journal.pone.0177777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews B, Walsh K, Coe S, Kenny MC, & Vagenas D (2015). Protocol for a systematic review: Child protection training for professionals to improve reporting of child abuse and neglect. Campbell Systematic Review, 11(1), 1–24. 10.1002/CL2.141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]