Abstract

Amyloidosis refers to a group of diseases caused by the deposition of abnormal proteins in tissues. Herein, curcumin was loaded in a nanohydrogel made of poly (vinylcaprolactam) to improve its solubility and was employed to exert an inhibitory effect on insulin fibrillation, as a protein model. Poly (vinyl caprolactam), cross-linked with polyethylene glycol diacrylate, was synthesized by the reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer method. The release profile of curcumin exhibited a first-order kinetic model, signifying that the release of curcumin was mainly dominated by diffusion processes. The study of curcumin release showed that 78% of the compound was released within 72 h. The results also revealed a significant decline in insulin fibrillation in the presence of curcumin-loaded poly (vinyl caprolactam). These observations confirmed that increasing the ratio of curcumin-loaded poly (vinyl caprolactam) to insulin concentration would increase the hydrogel’s inhibitory effect (P-value < 0.05). Furthermore, transmission electron and fluorescence microscopies and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy made it possible to study the size and interaction of fibrils. Based on the results, this nanohydrogel combination could protect the structure of insulin and had a deterrent effect on fibril formation.

Keywords: Insulin, Fibrillation, Curcumin, Poly (vinylcaprolactam), PVCL, Nano-hydrogel, RAFT, PEGDA

1. Introduction

Amyloid is a fibrillar insoluble form of amyloidogenic proteins such as insulin, α-synuclein, calprotectin, and α-β, which has some structural features rich in β-sheet. In limited cases, these proteinous aggregates are compatible with the body, such as intracellular amyloid in melanocytes that play a productive role in melanin formation. In most cases, these types of protein assembly are considered abnormalities like insulin and many of them lead to neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases [1]. Fibrillation of these amyloidogenic proteins is a challenging step during the production of their therapeutic forms for pharmaceutical and biological uses [2,3]. Along with cell therapy [4], novel therapies involving natural antioxidants and plant-derived products/molecules with neuroprotective properties are being used as adjunctive therapies [5]. Curcumin, an active component of turmeric, is one of the promising therapeutic agents. It is composed of natural hydrophobic compounds that have anti-cancer, anti-oxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties [6]. These features of curcumin have led to the synthesis of various analogues such as structural analogues, liposomal curcumin, phospholipid complex, and curcumin nanoparticles to enhance its bioavailability and to determine its impacts on humans’ health [7]. In general, curcumin enhances the performance of the immune system by interacting with certain immune cells such as lymphocytes and macrophages. Curcumin also induces immune responses by modulating immune molecules such as IgG, IgM, and sIgA [8]. In addition, the antioxidant properties of curcumin can make it a potential component in the food packaging industry, because bioactive ingredients such as curcumin can preserve the food quality and improve its safety [9].

Hydrogels or hydrophilic gels are three-dimensional polymers that are cross-linked networks fabricated by the interaction between monomers. Hydrogels have several advantages such as high ability to absorb a significant amount of water, controllable swelling behavior, flexibility, biocompatibility, and long survival [10]. These unique properties make them valuable materials for health products [11], agriculture [12], drug delivery systems[13], pharmaceuticals [14], bio-medical applications [15], diagnostics [16], and biosensors [17]. Nanogels are a subset of hydrogels with nanoscaled sizes. Nanogels offer a versatile platform as drug delivery matrices [18]. Poly (N-vinylcaprolactam) (PVCL) is a temperature-responsive polymer that has a Lower Critical Solution Temperature (LCST) in the physiological environment. Its features such as thermosensitivity as well as excellent biocompatibility and nontoxicity have attracted a lot of attention[19]. Since the transformation of soluble proteins into insoluble amyloids leads to various neurological diseases, research has reported the inhibitory effect of some substances on fibril formation including the use of polymeric ligands-coated nanoparticles [20], chitosan-coated mesoporous silica particles [21], and plant extracts such as coumarin [22], plumbagin [23], and curcumin [24]. However, the low solubility of curcumin in aqueous media limits its use as a therapeutic agent [25]. Nonetheless, when curcumin was loaded into PVCL-based nanogels such as PVCL-co-poly vinylacetate-co-polyethylene glycol, its solubility, chemical stability, and antioxidant activity were significantly enhanced [26]. To investigate their pharmaceutical trends in drug/gene delivery, various PVCL-based materials have been developed such as micelles, gels (i.e., nano and micro), and hybrids [27].

Previously, the Reversible Addition Fragmentation chain Transfer (RAFT) synthesis of different types of nanohydrogel based on poly hydroxyethyl methacrylate [28,29] and polyaminoethyl methacrylamide [30] was reported for drug delivery. Additionally, a lysine-modified nanohydrogel based on PVCL backbone was utilized for the delivery of doxorubicin [31]. Herein, PVCL cross-linked with PEGDA (PVCL-PEGDA) was fabricated via the RAFT technique. The prepared particles were loaded with curcumin and their efficacy in hampering the fibrillation of insulin was evaluated in vitro.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Materials

Curcumin (≥94%), Cyanomethyl N-methyl N-phenyl-dithiocarbamate, Vinyl Caprolactam (VCL) (98%), a,a-azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN 98%), poly(ethyleneglycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) (Mn 575), hexane, recombinant human insulin, thioflavin-T (ThT), Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) solution, and deuterium monoxide (D2O) were bought from Sigma Company. Congo red (CR), 1,4-dithiothreitol (DTT), acetic acid, NaCl, 8-Anilinonaphthalene-1-sulfonic acid (ANS), and other chemicals were purchased from Merck Company.

2.2. Instruments

To prepare buffers and other solutions in this study, the required water was achieved by an Ultra-pure water system (Direct-Q5). UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (LAMBDA 365) and fluorescence spectrophotometer (Varian Cary Eclipse) were used for spectroscopic studies. In addition, Fluorescence microscope (Lionheart FX), High-Performance Liquid Chromatographer (HPLC) (AZURA model) armed with 300 × 8 mm PSS SUPERMA size exclusion column (KNAUER, Germany), Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectrometer (FTIR) (Tensor II model), and Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) (Philips CM10) were used for investigating the effect of Cur@PVCL on fibril’s structure. Moreover, 1HNMR spectrometer (250 MHz, D2O), 13CNMR (62.9 MHz, D2O) (Bruker Avance DPX model), Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) (Sanaf S.DSC.T), Thermal Gravimetric Analysis(Mettler Toledo, USA), Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) (zeta sizer from Microtrac USA model) were used for the characterization of the synthesized nanogels.

3. Method

3.1. Synthesis of PVCL cross-linked PEGDA (PVCL-co-PEGDA)

To synthesize PVCL-co-PEGDA (briefly PVCL), VCL (9 mmol) and PEGDA (0.27 mmol), as a cross-linker, were mixed in dried dioxane (5 mL) in the presence of cyanomethyl N-methyl N-phenyl dithiocarbamate (0.045 mmol) as a RAFT agent and AIBN (0.0182 mmol) as the initiator. The mixture was degassed under nitrogen gas and was freeze-thawed several times. Then, the mixture was sealed and stirred at 90 °C for 48 h. Afterward, the reaction was washed with dried n-hexane three times. Finally, the product was dried with a freeze-dryer for 48 h [31].

3.2. Preparation of curcumin-loaded PVCL (Cur@PVCL)

To synthesize Cur@PVCL, PVCL (10 mg) and curcumin (1 mg) were dissolved in 10 mL PBS containing sodium chloride 150 mM. Then, the mixture was sealed and stirred at 25 °C for 48 h. Afterward, it was centrifuged at 6000 g for 15 min to separate the liquid solvent from the polymeric compound. Then, it was washed three times to remove unbound curcumin and was dried with a freeze dryer for 48 h.

3.3. Insulin fibril formation

To prepare the samples (2 mg/mL insulin solution) with the least difference, 28 mg of insulin was dissolved in 14 mL PBS containing sodium chloride 150 mM. Then, the samples were aliquoted in seven micro-tubes with a capacity of 2 mL. The samples were prepared by adding 1, 5, and 10 μl of both PVCL stock (10,000 ppm) and/or Cur@PVCL (10,000 ppm) stock to reach 1:1, 1:5, and 1:10 molar ratios of insulin to PVCL and Cur@PVCL, respectively. The measurements were made after 1, 6, 9, 24, 48, and 72 h of incubation at 45 °C, which was set as the stress condition.

3.4. The release of curcumin from PVCL

The release of curcumin from PVCL was investigated using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (LAMBDA 365). Initially, 2 mg Cur@PVCL was sonicated in 10 mL of PBS (a balanced salt formulation containing 10 mM phosphate and 150 mM sodium chloride at pH = 7.3–7.5) for 3 min. Then, the solution was shaken at 37 °C by 200 g. After that, 1 mL of the solution was picked up and replaced with fresh buffer for each measurement. The absorbance of the picked-up sample was read at the wavelength of 420 nm. This step was done at different time points during 96 h. The equivalent concentration of each absorbance was obtained using the equation of the standard curcumin curve. After that, the release percentage, as well as the cumulative percentage release, were calculated using the following equation:

| (1) |

Where n was the total number of picking up the sample, Ci was the concentration of curcumin at time i, and w was the initial curcumin mass in the sample.

Finally, the cumulative percentage release was computed in terms of time. These measurements were performed for three pH levels (7.5, 6.5, and 5). Triplet experiments were conducted for each pH to reduce the instrumental and investigator errors. To find the loading percentage, Cur@PVCL was put in acetic acid (1 M) solution to release all curcumin, and UV-Vis absorbable was measured at 418 nm (absorbance characteristic for curcumin). Using the calibration curve of curcumin, its concentration was calculated at about 22.31 ppm.

3.5. Fluorescence spectroscopy

Fluorescence spectroscopy was performed using a Varian Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer, which was equipped with Peltier to control the thermal conditions. All the studies were performed with 1 mL UV quartz cuvette. In doing so, 5 μl of ThT 100 μM (PBS containing sodium chloride 150 mM) was added to all the samples. After a 10-min incubation at a dark place, the samples were ready for ThT spectroscopy. The measurements were performed after incubation for 1, 6, 24, 48, and 72 h. The fluorescence intensity was measured at 484 nm.

For the control samples, all compounds were prepared without the protein and their fluorescence intensity at the wavelength of 484 nm was subtracted from the fluorescence sample. After all, the kinetic parameters of insulin fibrillation were analyzed using the following equation, in which yi and yf respectively represented the intensity of the emitted light in the initial lag phase and plateau phase, and mi and mf were their slopes.

| (2) |

The extracted kinetic parameters included the half-life t (t1/2) of the formation of the fibril, lag time (t lag), and rate constant (K app), which have been given in the table below [32].

3.6. UV-Vis spectrophotometer

All the previous steps in the preparation of the fibril samples were performed here. After that, 5 μl of CR 50 μM (PBS containing sodium chloride 150 mM used as the solvent) was added to all the samples. Then, a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (LAMBDA 365) gave the absorbed wavelength intensity to the wavelength set in the visible region. The variations of CR absorbance were plotted for each ratio of insulin to PVCL and Cur@PVCL at different incubation times [33].

3.7. DTT-induced insulin aggregation

Similar to the CR test, UV-Vis (LAMBDA 365) was used to study the kinetics of insulin aggregation in the presence of DTT, as a disulfide bonds reducer. Samples containing 1 mL of insulin 0.4 mg/mL with the same concentration ratio to PVCL and Cur@PVCL, as the previous samples, and similar solvents were prepared. Just before spectroscopy, 5 μl of DTT (4 mM) was added to these samples to increase the rate of aggregation. The spectrophotometer was set at the wavelength of 360 nm for 20 min. Then, the diagram of absorption intensity in terms of time was drawn for different ratios of PVCL concentration to Cur@PVCL.

3.8. Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis study

To further investigate the aggregation behavior of insulin in the presence of the compounds, Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel (SDS-PAGE) analyses were assayed. At first, insulin 2.0 mg/mL was incubated with the maximum concentration of PVCL and Cur@PVCL (1–10 molar ratio). For better judgment, insulin was also incubated with curcumin alone. The prepared samples were incubated at 60 °C for 2 h and were then centrifuged (12,000 g) for 10 min. After collecting the supernatants, the obtained residues were prepared for non-reducing SDS-PAGE analysis. It should be noted that the unaggregated insulin would remain on the supernatants. Finally, 40 μl of each supernatant was loaded into each well.

3.9. Transmission electron microscope

Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) was used to investigate the size of insulin fibrils via a Philips CM10 transition electron microscope (Amsterdam, Netherlands). The three fibril samples included the control sample, the highest ratio of PVCL to insulin, and the highest ratio of Cur@PVCL to insulin.

3.10. Fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence imaging was performed using the Lionheart FX device (USA). To obtain the image of insulin amyloids, the microscope was set at 465 and 525 nm for excitation and emission wavelengths, respectively. Images were taken using the slide scanning method. To take the images, 10 μl of each fibril sample was mixed with 5 μl of ThT 100 μM until they became uniform. They were then placed on a slide in a dark place for 30 min to dry and to interact with the dye and the fibrils.

3.11. Size exclusion chromatography

Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) technique was used to evaluate the effect of the presence of Cur@PVCL on the population of insulin aggregates. It was performed by the KEAUER AZURA (Berlin, Germany). In doing so, three fibril samples were utilized including the control sample, the highest ratio of PVCL to insulin, and the highest ratio of Cur@PVCL to insulin. The measurements were performed under a flow rate of 1 mL/min and at a wavelength of 210 nm during a run time of 10 min. The number of fibril populations was plotted by the chromatographer.

3.12. Attenuated total reflection Fourier-transform infrared spectrophotometer

Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectrophotometer (ATR-FTIR) was performed by a Tensor II device (Bruker, Germany) using a 4 cm−1 resolution and an accumulation of 256 scans to study the secondary structure of the insulin fibril samples. To determine the ATR-FTIR spectrum, the samples had to be washed in D2O for eliminating any residual salts, H2O, and/or buffer contents. To do so, the samples were centrifuged three times with D2O and were then allowed to dry sufficiently. The percentage of absorbance was calculated within the range of 1600–1700 1/cm.

3.13. Statistical analysis

The significance level in this study was considered 0.05 (P-value < 0.05) and the number of replications for each experiment was considered at least three and the average of all replications was used as reportable data. Statistical operations were performed using GraphPad Prism V.7 software.

4. Results

In this study, after the synthesis of the PVCL-PEG, the structure and morphological properties of the hydrogel were characterized. Then, curcumin was loaded into the PVCL-PEG (to make Cur@PVCL) and its release profile was assessed. The effect of Cur@PVCL on insulin fibrillation was evaluated via ThT and CR experiments. The effect of Cur@PVCL on insulin was also investigated by SDS-PAGE. Additionally, the interactions of insulin fibrils with each other were explored by a fluorescence microscope, and their shapes, size distribution were studied through TEM and SEC, respectively. Finally, the fibrils’ structures were assessed by FTIR.

VCl is polymerized by the PEGDA, as a cross-linker, through the RAFT polymerization process. In this process, cyanomethyl, N-methyl, N-phenyl dithiocarbamate was used as the Chain Transfer Agent (CTA) as a specific type for n-vinylamide monomers and AIBN acted as the initiator of radical processes (Fig. S1). PEGDA, as an amphiphilic crosslinker, introduced the hydrogelation properties to the structure. Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration would transfer biosafety properties to the main structure. The RAFT synthesis of PVCL cross-linked by PEGDA has been reported by the present research team elsewhere [31]. The synthetic route of the PVCL-PEG was improved by the feed ratio of CTA/PEGDA/PVCL = 1: 3: 47. 1HNMR spectroscopy of the prepared structure showed the N-CH3 group of CTA moiety at 4.8 ppm, the proton of methine groups (CH-N) of PVCL backbone at 4–4.5 ppm, and methylene groups of PEG (−O-CH2) at 3.8 ppm. The 13CNMR also confirmed the structure of PVCL-PEG (Fig. S2). The Molecular Weight (MW) of the structure was calculated to be around 6.5 kD by the integrated peaks of index protons of the 1HNMR result. The MW of the structure was also analyzed by SEC, which was found to be around 6.2 kD [31]. The structural characterization was also performed by FT-IR spectroscopy (Fig. S3). In this spectrum, the characteristic bands of PVCL could be attributed to the amide group, which appeared at 1420 and 1470 cm−1, and the C-H stretching vibrations absorption appeared at 2910 and 2973 cm−1. There was also a C-O absorption peak related to PEG, which appeared at 1070–1200 cm−1. The synthesized structure could form nanohydrogels in aqueous media. DLS measurements demonstrated that the particles had varied ranges in size, with a maximum diameter of 271 nm (Fig. S5-SI). Additionally, the phase transition behavior of PVCl-PEG was determined by Differential Scanning Colorimetric (DSC) measurements. The DSC curves indicated that the phase transition changed at 32 °C (Fig. S4). Furthermore, Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) was employed to evaluate the thermal stability of the polymers. Based on the results, PVCL-PEG started to degrade before 200 °C, similar to other polymers. As shown in Fig. S6, the main decomposition step for PVCL-PEG started at 394.70 °C and ended at 446.21 °C.

Curcumin, as an anti-amyloid agent (curcumin inhibited the formation of amyloid-beta oligomers and fibrils, binds plaques, and moderates amyloid in vivo [34]), could promote the antifibrillation effect on this platform. With this aim, PVCL-PEG was loaded with curcumin. Compared to the concentration of original curcumin (100 ppm), the percent of curcumin absorption was 22.31%.

During the preparation of the samples, the dissolution of PVCL-PEG caused a cloudy insulin solution compared to the control sample (insulin alone), while the addition of Cur@PVCL resulted in a clearer sample. Therefore, a homogeneous mixture was obtained. Previous studies showed that curcumin did not have good solubility in aqueous solvents [25], while Cur@PVCL was shown to increase the solubility of the compound (Fig. S7).

The released profile of curcumin (Fig. 1) revealed the highest percentage of release after 72 h. In the first 24 h, more than 70% of curcumin was released from PVCL with a rapid slope. Then, the release of curcumin continued with a gentle slope, so that the release reached only 78% 48 h later. After that, there were no significant changes in curcumin release (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Curcumin release profile The profile of the cumulative release of curcumin from the Cur@PVCL system in terms of time (96 h) at pH= 7.5 (A). Matching various kinetic models with the cumulative release curve of Cur@PVCL (B).Cur, curcumin; PVCL, polyvinyl chloride.

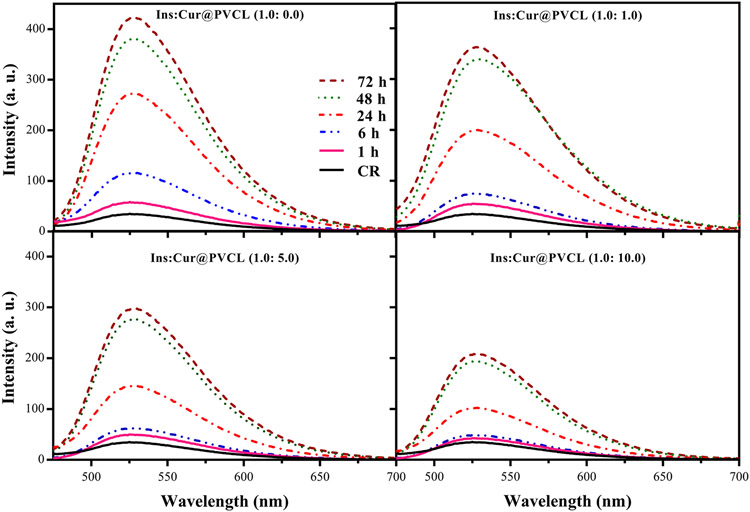

Thioflavin T is a fluorescence dye that can interact with amyloid fibrils and is commonly used to diagnose amyloids [35]. To further study the insulin fibrils, ThT was added to all samples. Using the sigmoid curve obtained from the ThT fluorescence signals, kinetic parameters of the fibrillation process were calculated (Table 1). The resulting diagram included three stages, namely the initial lag phase, the elongation phase, and the plateau phase where no new fibrils were formed. For the control sample, the initial lag phase lasted 21 h, the fibrillation phase was completed in the first 55 h, and finally, the plateau phase was reached. However, these values changed in the presence of PVCL and Cur@PVCL, which have been presented in Table 1 (Fig. 2 and Table 1). On the whole, using the PVCL increased the kinetics of insulin fibrillation, while the rate witnessed a decrease in the presence of Cur@PVCL.

Table 1.

The kinetic parameters of insulin fibrillation Extracted kinetic parameters from the diagram related to the data obtained from Thioflavin fluorescence intensity.

| Ins:PVCL | t1/2 (min) | tlag (min) | T (min) | Kapp (1/min) | Ins:Cur@PVCL | t ½ (min) | tlag (min) | T (min) | Kapp (1/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:0 | 35 | 24 | 5.5 | 0.1818 | 1:0 | 35 | 24 | 5.5 | 0.1818 |

| 1:1 | 33 | 20 | 6.5 | 0.1538 | 1:1 | 37.5 | 28 | 4.75 | 0.2105 |

| 1:5 | 31 | 16 | 7.5 | 0.1333 | 1:5 | 39 | 32 | 3.5 | 0.2857 |

| 1:10 | 30 | 15 | 7.5 | 0.1333 | 1:10 | 40 | 33 | 3.5 | 0.2857 |

Fig. 2.

The ThT binding test. Insulin fibrillation behavior in the presence of PVCL (A) and the presence of Cur@PVCL (B). The latter compound (B) indicated the insulin inhibitory effect. In these diagrams, the intensity has been plotted at 483 nm versus time at three different ratios of insulin to PVCL and insulin to Cur@PVCL. Cur, curcumin; PVCL, polyvinyl chloride.

The inhibition effect of Cur@PVCL on the formation of insulin fibrils was confirmed by the CR reagent (Fig. 3). The absorption of CR for each ratio of insulin concentration was measured at 1, 6, 24, 48, and 72 h time intervals. The results indicated that the growth of fibrils resulted in an increase in the absorption of the CR reagent over time. However, increasing the Cur@PVCL concentration reduced the absorption intensity, which revealed the inhibitory effect of Cur@PVCL on the formation of the protein fibrils. Nonetheless, adding the concentration did not cause a significant change in the inhibitory effect, indicating an optimal concentration of Cur@PVCL (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The interaction of CR with the insulin fibrils Insulin fibrils were made in the presence of PVCL and Cur@PVCL and then, the interaction of CR with the fibrils was studied. The experiment was done using four different ratios of insulin to Cur@PVCL during 72 h of incubation. CR, Congo red; Cur, curcumin; PVCL, polyvinyl chloride.

According to Fig. 4, the diagram consisted of three stages; i.e., a small initial lag phase, an elongation phase, and an equilibrium phase, which was consistent with the Smoluchowski model indicating the time evolution of the density of particles as they coagulate [36]. To study the effect of Cur@PVCL on disulfide bond-mediated insulin aggregation, DTT was added to insulin in the presence of several concentrations of PVCL and Cur@PVCL. Insulin showed an initial phase of fewer than two minutes in the presence of PVCL, while the initial phase increased to four minutes in the presence of Cur@PVCL. As the concentration of Cur@PVCL increased, not only the slope of the diagram decrease, but also the diagram reached the equilibrium phase at a lower intensity, which indicated a decrease in the number of aggregations (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

DTT-induced insulin aggregation and studying the effects of applied compounds during the aggregation Comparison of the kinetics of DTT-induced insulin aggregation in the presence of PVCL and Cur@PVCL. Each sample contained 0.4 mg/mL insulin, 5 μl of 4 mM DTT, and different concentrations of PVCL and Cur@PVCL. The samples were analyzed at 43 °C for 20 min. The absorbance wavelength was fixed at 360 nm.DDT, dithiothreitol; Cur, curcumin; PVCL, polyvinyl chloride.

To better evaluate the effects of the prepared hydrogels on the aggregation of insulin, non-reducing SDS-PAGE was assayed. As Fig. 5 depicts, the monomeric residual of insulin was more soluble on the supernatant in the presence of curcumin and Cur@PVCL, while the main portions of the samples were aggregated for the control and PVCL.

Fig. 5.

SDS-PAGE analysis of aggregated insulin in the presence of the studied compounds SDS-PAGE analyses of insulin aggregation in the presence of the hydrogels and curcumin alone. 15% non-reducing SDS-PAGE was applied for the test. Lane 1 indicates the obtained supernatant of insulin after inducing stress to the insulin sample in the presence of curcumin alone. Lanes 2, 3, and 4 stand for the obtained supernatants of insulin in the control state, in the presence of PVCL, and the presence of Cur@PVCL, respectively. SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; Cur, curcumin; PVCL, polyvinyl chloride.

The microscopic fluorescence was evaluated using the ThT dye. This dye can stain fibrils’ plaques and can be observed with a fluorescence microscope [21]. The obtained images demonstrated that the fibrils were large and dense in the presence of PVCL compared to the control sample, which indicated their high interaction with each other. Nevertheless, they were small and scattered in the presence of Cur@PVCL, showing the lower lateral interactions of these fibrils (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The fluorescence microscopic images of insulin fibrils Under stress conditions, the fluorescence microscopic images of preformed insulin fibrils in the presence of PVCL and Cur@PVCL were taken. The test indicated the inhibitory effect of the Cur@PVCL hydrogel on insulin fibrillation. To prepare the fibrils for imaging, the samples at three different protein-compound ratios were incubated at 45 °C for 24 h. Then, 10 μl of each sample with 5 μl of ThT (100 μM) were uninformed on glass slides and were dried in a dark environment for 30 minCur, curcumin; PVCL, polyvinyl chloride.

Using TEM, the length and other morphological varieties of the fibrils could be monitored. Although the fibrillation process was completed in the absence of either PVCL or Cur@PVCL, amorphous aggregates were formed in the presence of these two compounds. Therefore, it could be concluded that both PVCL and Cur@PVCL reduced the longitudinal growth of fibrils (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Transmission electron microscopy of insulin fibrils Generated insulin fibrils in the presence of the maximum studied ratio of insulin to compounds (1:10) were selected for TEM analysis. The samples were prepared after a 24-h incubation under the stress condition.

Cur, curcumin; PVCL, polyvinyl chloride.

SEC was used to evaluate the overall size of the fibrils. Based on the results presented in Fig. 8, the first sample that only contained insulin (control sample) had two equal absorption intensities in the retention times of three and four minutes, which indicated two populations of fibrils with slight differences in size. In the presence of PVCL, however, the fibrils population shifted to higher MWs. In the presence of Cur@PVCL, the opposite happened; the samples were transformed to smaller sizes due to the delay in leaving the column. Therefore, it could be concluded that the population of smaller fibrils increased in the presence of Cur@PVCL (Fig. 8). All the changes detected in the size of insulin aggregates by SEC were superficial.

Fig. 8.

SEC analyses of aggregated insulin specimens The SEC experiment has been shown for three different insulin samples after a 24-h incubation under stress conditions. The gel filtration was performed at a flow rate of 1 mL/min for 20 min. The absorbance wavelength was fixed at 210 nm. SEC, size exclusion chromatography; Cur, curcumin; PVCL, polyvinyl chloride.

To evaluate the structure of the obtained fibrils in different conditions, ATR-FTIR assessments were done (Fig. 9). The main secondary structure content of insulin fibrils was the β-sheet form, and extended chain and α-helix were the second and third dominant contents, respectively. Besides, α-helix was the dominant content in the preformed fibrils in the presence of PVCL and Cur@PVCL. In these two forms of fibrils, the extended chain was transformed to a disordered state.

Fig. 9.

Secondary structure analyses of the obtained insulin fibrils in different situations The secondary structures were evaluated by ATR-FTIR. Deconvolutions were done by the Origin Lab 2018b software. ATR-FTIR, attenuated total reflection-Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy; Cur, curcumin; PVCL, polyvinyl chloride.

For better judgment, Table 2 has been presented.

Table 2.

Deconvolution of fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy data Amide I region for insulin fibril (made in the presence of the synthesized hydrogels) was selected for further analyses.

| Extended chain /Side chain | β-sheet | α-helix | Disordered/turn | Anti-parallel β-sheet | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | 1609–1618 | 1622–1637 | 1641–1657 | 1660–1678 | 1685–1697 |

| Area % | |||||

| Insulin | 24 | 34 | 18 | 13 | 11 |

| Insulin +PVCL | 16 | 30 | 33 | 12 | 9 |

| Insulin +Cur@PVCL | 11 | 19 | 41 | 16 | 13 |

5. Discussion

Nanogels are known as potential carriers in pharmaceutical applications that have such properties as hydrophilicity and compatibility [31]. One of these well-known synthetic nanogels is PVCL, which can increase the solubility of insoluble substances [37,38]. To enhance the bio-availability of curcumin, PVCL-PEGDA was used for the synthesis of Cur@PVCL (Fig. S4).

All Cur@PVCL showed a release behavior that could be described using a Korsmeyer-Peppas kinetic model, which was obtained by matching various kinetic models with the cumulative release curve of Cur@PVCL (Fig. 1-B) [39]. Previously, this model was proposed to release drugs from polymeric matrixes such as hydrogels, and this mechanism was considered a superposition of two independent mechanisms of relaxation and diffusion [40]. In the present study, 22% of curcumin was loaded to PVCL. In the first 24 h, the curcumin release study showed that 69% of curcumin was released, and this measure reached a maximum of about 78% after 72 h (Fig. 1-A).

ThT is one of the oldest standard dyes for studying the formation of amyloid fibrils such as insulin [41,42]. When ThT binds to β-sheets rich structures, it not only increases the intensity of fluorescence emission but also makes a blue shift [43,44]. Thus, it shows a sharp increase in fluorescence due to binding to amyloid fibrils with the maximum excitation at around 450 nm and the maximum emission at around 485 nm [36]. The curve of these graphs is usually sigmoidal, and the t 1/2, t lag, and K app can be extracted from the equations of these graphs [45,46]. In the present study, increasing the ratio of Cur@PVCL to insulin resulted in an increase in t 1/2, which represented the time required to reach the half-maximum fluorescence emission from ThT binding to the fibrils. Additionally, t lag that represented the time required to reach the minimum fibrils concentration within the detection range of the device was consistent with t ½ (Fig. 2-B). This implied that increasing the concentration of Cur@PVCL to insulin enhanced the time required to start fibrillation as well as the time required to reach the maximum amount of fluorescence. However, opposite results were obtained in the presence of PVCL alone. PVCL that was unsaturated with curcumin could absorb water from the environment, which dried the environment and increased insulin fibrillation (Fig. 2-A). Consequently, increasing the ratio of Cur@PVCL to insulin led to a decline in the amount of insulin fibrils.

CR is another dye used to identify the presence of fibrils both in vivo and in vitro. When CR interacts with amyloid fibrils, it creates a complex with refractive properties. The maximum absorption for this complex is within the range of 490–540 nm [47]. CR also exhibits a characteristic redshift when it attaches to amyloid fibrils [48]. In the current research, the formation of fibrils was measured in the absence of curcumin as well as in the presence of Ins:Cur@PVCL (1:1, 1:5, and 1:10 ratios) in different time intervals of 1, 6, 24, 48, and 72 h (Fig. 3). Naturally, as the incubation time increases, the amount of fibrils increases for each ratio, especially in the elongation phase. In the present study, increasing the ratio of insulin: Cur@PVCL decreased the absorption intensity in the mentioned range along with a redshift. Consequently, it was concluded that the presence of Cur@PVCL in insulin led to a decrease in absorption intensity or a reduction in amyloid fibrils. These results were in agreement with the information obtained from the ThT test.

Insulin stability is another factor that shows its correct and flawless function. Due to the sensitive structure of proteins, a lot of effort has always been made to maintain their stability in physical and chemical environments [42]. By losing the stability, insulin would tend to aggregate, hence, the effect of Cur@PVCL on insulin fibrillation is very important. Insulin has three disulfide bonds, one of which is in-chain and the other two being out-chain. Decomposition of each of these disulfide bonds disrupts the structure of insulin and may result in the fibrillation phenomenon [22]. To investigate the susceptibility of insulin to reducing agents, DTT was used to assess the effect of PVCL and Cur@PVCL on the decomposition of each of these sulfide bonds (Fig. 4) [49]. Based on the findings, the absorption intensity at 360 nm was always lower than the control in the presence of Cur@PVCL. As the ratio of Cur@PVCL to insulin increased, this absorption intensity decreased, indicating greater insulin resistance to aggregate. However, opposite findings were obtained for PVCL. As the ratio of PVCL to insulin increased, the absorption intensity increased, as well, indicating greater protein susceptibility. Subsequently, it was concluded that not only Cur@PVCL did not cause instability, but it also increased the stability of this structure.

According to Fig. 5, the amount of insulin that remained undigested in the supernatant was greater in the presence of curcumin than in the control state (without the presence of an enhancer). However, when insulin was incubated with the synthetic substance of the nanogels, more insulin would stay away from the destruction and the share of nondamaged insulin in the supernatant would increase.

Generally, fluorescence microscopy is used to create 3-D images of small-scale specimens [50]. This technique allows the visualization of the dynamics of insulin fibrils in the presence of different concentrations of PVCL and Cur@PVCL [51]. It also allows the comparison of the density of amyloid fibrils and their lateral interactions. In the current investigation, insulin was incubated for 24 h, which was considered the control. As shown in Fig. 6, by increasing the concentration of Cur@PVCL, the diameter of the insulin fibrils bundles decreased, which represented the interaction between fibrils. On the other hand, similar to the previous observations, an increase in the concentration of PVCL enhanced the density of the fibrils and their lateral interactions. Therefore, denser fibrils were seen. It was thus concluded that increasing the concentration of Cur@PVCL reduced the lateral interaction, density, and variety of insulin fibrils in comparison to its absence.

In the present research, TEM was used to assess the effect of Cur@PVCL on the size and interaction of the amyloid fibrils. This evaluation was performed with scale bars of 300 nm. The results related to the insulin fibrils incubated after 24 h in the absence of Cur@PVCL and PVCL as well as in the presence of their highest concentration ratios (Ins: PVCL (1:10) and Ins: Cur@PVCL (1:10)) have been illustrated in Fig. 7. As expected, in the absence of Cur@PVCL, insulin fibrils were longer and had more lateral interactions, which was compatible with another report [52]. On the contrary, in the presence of Cur@PVCL, a reduction was observed in the length and the lateral interactions between the fibrils. Therefore, Cur@PVCL had an inhibitory effect on the formation and growth of these amyloid fibrils.

In this study, the trends of insulin oligomerization were assessed using a gel filtration column (SEC) and the results have been shown in Fig. 8. To both intensify the oligomerization changes and better detect the output signal via chromatography, insulin was incubated with Cur@PVCL and PVCL at the concentration ratio of 1:10. When insulin was incubated with Cur@PVCL, the insulin molecules changed from the hexamer state to a lower oligomerization ratio. However, no such results were obtained when insulin was incubated using PVCL alone. The changes in insulin monomer to a higher oligomeric state in the presence of curcumin at a flow rate of 1 mL/min for 20 min were partially inhibited compared to the changes related to insulin alone, showing that curcumin could modulate insulin aggregation during this time frame. Similarly, the data extracted from Fig. 9 and Table 2 indicated that in the presence of Cur@PVCL, the area under the graph decreased at the wavelength of 1622–1637 nm, which represented a decrease in the β-sheet structure. On the other hand, the area under the graph increased at the wavelength of 1641–1657 nm, indicating an increase in the α-helix structure. Similar results were also obtained at the wavelength of 1609–1618, which showed the side chain of insulin. These results suggested that α-helix to β-sheet restructuring was inhibited in the presence of Cur@PVCL.

All in all, considering the negative effect of PVCL on insulin fibrillation as well as the previous findings on the potential ability of the hydrogel to absorb water, reducing the free water molecules around insulin molecules may speed up the rate of protein fibrillation, indicating the importance of water studies during the fibrillation of proteins.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, PVCL-PEG was reported as a new hydrophilic carrier for curcumin, which increased its solubility and bio-availability. Cur@PVCL could inhibit insulin fibrillation, and the rate of inhibition depended on the Cur@PVCl concentration. Accordingly, increasing the concentration of Cur@PVCL was accompanied by an increase in the inhibitory effect. Thus, Cur@PVCl reduced the efficiency of insulin fibrillation. In addition, FTIR assessment showed that Cur@PVCl could inhibit the conformational transition from α-helix to the β-sheet form.

Previously, there were many problems in using curcumin for the treatment of some proteins and its therapeutic applications, the most important of which is the insolubility of curcumin in aqueous medium. On the other hand, maintaining the final amount of the compound is of a great factor for its efficiency [34,53]. In this study, using PVCL hydrogel, we tried to continuously release a certain and necessary amount of curcumin in an aqueous medium so that the final amount is considered and can have its functional effect, which is to inhibit the process of fibrillation in insulin. Therefore, Cur@PVCL could be considered a therapeutic agent for reducing the rate of insulin fibrillation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Ms. A. Keivanshekouh at the Research Consultation Center (RCC) of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for her invaluable assistance in editing the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to thank Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for supporting this work under grant No. 24300. They would also like to acknowledge the grants provided by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health (award No. R15DE027533 and 1 R56 DE029191-01A1).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2022.04.009.

References

- [1].Aguzzi A, O’connor T, Protein aggregation diseases: pathogenicity and therapeutic perspectives, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 9 (2010) 237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Stefani M, Protein misfolding and aggregation: new examples in medicine and biology of the dark side of the protein world, Biochim. Et. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Basis Dis 1739 (2004) 5–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Akbarian M, Khani A, Eghbalpour S, Bioactive pepticles: synthesis, sources, applications, and proposed mechanisms of action, Int. J. Mol. Sci 23 (2022) 1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Akbarian M, Insulin therapy; a valuable legacy and its future perspective, Int. J. Biol. Macromol (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Leuci R, Brunetti L, Poliseno V, Laghezza A, Loiodice F, Tortorella P, Piemontese L, Natural compounds for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases, Foods 10 (2021) 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mythri RB, Bharath Μ.M. Srinivas, Curcumin: a potential neuroprotective agent in Parkinson’s disease, Curr. Pharm. Des 18 (2012) 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kocaadam B, Şanlier N, Curcumin, an active component of turmeric (Curcuma longa), and its effects on health, Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr 57 (2017) 2889–2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Xu X-Y, Meng X, Li S, Gan R-Y, Li Y, Li H-B. Bioactivity, health benefits, and related molecular mechanisms of curcumin: current progress, challenges, and perspectives, Nutrients 10 (2018) 1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Aliabbasi N, Fathi M, Emam-Djomeh Z, Curcumin: a promising bioactive agent for application in food packaging systems, J. Environ. Chem. Eng 9 (2021), 105520. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ahmed EM, Hydrogel: preparation, characterization, and applications: a review, J. Adv. Res 6 (2015) 105–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Caló E, Khutoryanskiy VV, Biomedical applications of hydrogels: a review of patents and commercial products, Eur. Polym. J 65 (2015) 252–267. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Saxena AK, Synthetic biodegradable hydrogel (PleuraSeal) sealant for sealing of lung tissue after thoracoscopic resection, J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg 139 (2010) 496–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hosseini M, Farjadian F, Makhlouf ASH, Smart stimuli-responsive nano-sized hosts for drug delivery. Industrial Applications for Intelligent Polymers and Coatings, Springer, Cham, 2016, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kashyap N, Kumar N, Kumar MR, Hydrogels for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications, Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carr. Syst (2005) 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Stamatialis DF, Papenburg BJ, Girones M, Saiful S, Bettahalli SN, Schmitmeier S, Wessling M, Medical applications of membranes: drug delivery, artificial organs and tissue engineering, J. Membr. Sci 308 (2008) 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Van der Linden HJ, Herber S, Olthuis W, Bergveld P, Stimulus-sensitive hydrogels and their applications in chemical (micro) analysis, Analyst 128 (2003) 325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Krsko P, McCann TE, Thach T-T, Laabs TL, Geller HM, Libera MR, Length-scale mediated adhesion and directed growth of neural cells by surface-patterned poly (ethylene glycol) hydrogels, Biomaterials 30 (2009) 721–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Dreiss CA, Hydrogel design strategies for drug delivery, Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci 48 (2020) 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Marsili L, Dal Bo M, Eisele G, Donati I, Berti F, Toffoli G, Characterization of thermoresponsive poly-N-Vinylcaprolactam polymers for biological applications, Polymers 13 (2021) 2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Brahmaiah M, Sanjai K, Una J, Mihaela D, Biopolymer-coated gold nanoparticles inhibit human insulin amyloid fibrillation, Sci. Rep (2020) 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Akbarian M, Tayebi L, Mohammadi-Samani S, Farjadian F, Mechanistic assessment of functionalized mesoporous silica-mediated insulin fibrillation, J. Phys. Chem. B (2020) 124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Akbarian M, Rezaie E, Farjadian F, Bazyar Z, Hosseini-Sarvari M, Ara EM, Mirhosseini SA, Amani J, Inhibitory effect of coumarin and its analogs on insulin fibrillation/cytotoxicity is depend on oligomerization states of the protein, RSC Adv. 10 (2020) 38260–38274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Anand BG, Prajapati KP, Purohit S, Ansari M, Panigrahi A, Kaushik B, Behera RK, Kar K, Evidence of anti-amyloid characteristics of plumbagin via inhibition of protein aggregation and disassembly of protein fibrils, Biomacromolecules (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Carvalho Dd.M., Takeuchi KP, Geraldine RM, Moura C.Jd, Torres MCL, Production, solubility and antioxidant activity of curcumin nanosuspension, Food Sci. Technol 35 (2015) 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Liu Q, Han C, Tian Y, Liu T, Fabrication of curcumin-loaded zein nanoparticles stabilized by sodium caseinate/sodium alginate: Curcumin solubility, thermal properties, rheology, and stability, Process Biochem. 94 (2020) 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Li M, Xin M, Guo C, Lin G, Wu X, New nanomicelle curcumin formulation for ocular delivery: improved stability, solubility, and ocular anti-inflammatory treatment, Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm 43 (2017) 1846–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rao KM, Rao KSVK, Ha C-S. Stimuli responsive poly (vinyl caprolactam) gels for biomedical applications, Gels 2 (2016) 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Roointan A, Farzanfar J, Mohammadi-Samani S, Behzad-Behbahani A, Farjadian F, Smart pH responsive drug delivery system based on poly(HEMA-co-DMAEMA) nanohydrogel, Int. J. Pharm 552 (2018) 301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Farzanfar J, Farjadian F, Roointan A, Mohammadi-Samani S, Tayebi L, Assessment of pH responsive delivery of methotrexate based on PHEMA-st-PEG-DA nanohydrogels, Macromol. Res 29 (2021) 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Entezar-Almahdi E, Heidari R, Ghasemi S, Mohammadi-Samani S, Farjadian F, Integrin receptor mediated pH-responsive nano-hydrogel based on histidine-modified poly (aminoethyl methacrylamide) as targeted cisplatin delivery system, J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol 62 (2021), 102402. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Farjadian F, Rezaeifard S, Naeimi M, Ghasemi S, Mohammadi-Samani S, Welland ME, Tayebi L, Temperature and pH-responsive nano-hydrogel drug delivery system based on lysine-modified poly (vinylcaprolactam), Int. J. Nanomed 14 (2019) 6901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Akbarian M, Yousefi R, Moosavi-Movahedi AA, Ahmad A, Uversky VN, Modulating insulin fibrillation using engineered B-chains with mutated C-termini, Biophys. J (2019) 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Jayamani J, Shanmugam G, Singam ERA, Inhibition of insulin amyloid fibril formation by ferulic acid, a natural compound found in many vegetables and fruits, RSC Adv. 4 (2014) 62326–62336. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Yang F, Lim GP, Begum AN, Ubeda OJ, Simmons MR, Ambegaokar SS, Chen PP, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Frautschy SA, Curcumin inhibits formation of amyloid β oligomers and fibrils, binds plaques, and reduces amyloid in vivo, J. Biol. Chem 280 (2005) 5892–5901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Khurana R, Coleman C, Ionescu-Zanetti C, Carter SA, Krishna V, Grover RK, Roy R, Singh S, Mechanism of thioflavin T binding to amyloid fibrils, J. Struct. Biol 151 (2005) 229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Schreck JS, Yuan J-M, A kinetic study of amyloid formation: fibril growth and length distributions, J. Phys. Chem. B 117 (2013) 6574–6583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Mohanty C, Das M, Sahoo SK, Emerging role of nanocarriers to increase the solubility and bioavailability of curcumin, Expert Opin. Drug Deliv 9 (2012) 1347–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zhang J, Li J, Shi Z, Yang Y, Xie X, Lee SM, Wang Y, Leong KW, Chen M, pH-sensitive polymeric nanoparticles for co-delivery of doxorubicin and curcumin to treat cancer via enhanced pro-apoptotic and anti-angiogenic activities, Acta Biomater. 58 (2017) 349–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Mendyk A, Jachowicz R, Fijorek K, Dorozynski P, Kulinowski P, Polak S, KinetDS: an open source software for dissolution test data analysis, Dissolution Technol. 19 (2012) 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bruschi ML, Strategies to Modify the Drug Release from Pharmaceutical Systems, Woodhead Publishing, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Naiki H, Higuchi K, Hosokawa M, Takeda T, Fluorometric determination of amyloid fibrils in vitro using the fluorescent dye, thioflavine T, Anal. Biochem 177 (1989) 244–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Akbarian M, Yousefi R, Farjadian F, Uversky VN, Insulin fibrillation: toward the strategies for attenuating the process, Chem. Commun (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].LeVine III H, [18] Quantification of β-sheet amyloid fibril structures with thioflavin T, Methods Enzymol. 309 (1999) 274–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Reinke AA, Gestwicki JE, Structure–activity Relationships of amyloid beta-aggregation inhibitors based on curcumin: influence of linker length and flexibility, Chem. Biol. Drug Des 70 (2007) 206–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Ferrone F, [17] Analysis of protein aggregation kinetics, Methods Enzymol. 309 (1999) 256–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Nilsson MR, Techniques to study amyloid fibril formation in vitro, Methods 34 (2004) 151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Siddiqi MK, Alam P, Chaturvedi SK, Shahein YE, Khan RH, Mechanisms of protein aggregation and inhibition, Front Biosci. 9 (2017) 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Beretta C Studies of Aβ aggregation, toxicity and cellular uptake. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Lichtman JW, Denk W, The big and the small: challenges of imaging the brain’s circuits, Science 334 (2011) 618–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kumar A , Biochemical and Biophysical Characterization of a Class II Alpha Mannosidase from Lens culinaris (lentil) and Canavalia ensiformis, Jack Bean, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Iannuzzi C, Borriello M, Irace G, Cammarota M, Di Maro A, Sirangelo I, Vanillin affects amyloid aggregation and non-enzymatic glycation in human insulin, Sci. Rep 7 (2017) 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Bouvier ES, Koza SM, Advances in size-exclusion separations of proteins and polymers by UHPLC, TrAC Trends Anal. Chem 63 (2014) 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Belkacemi A, Doggui S, Dao L, CJErimm Ramassamy. Challenges associated with curcumin therapy in Alzheimer disease, 2011,13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.