Abstract

Purpose of Review

The purpose of this review is to discuss current knowledge and recent findings regarding clinical aspects of thickeners for pediatric gastroesophageal reflux and oropharyngeal dysphagia. We review evidence for thickener efficacy, discuss types of thickeners, practical considerations when using various thickeners, and risks and benefits of thickener use in pediatrics.

Recent Findings

Thickeners are effective in decreasing regurgitation and improving swallowing mechanics and can often be used empirically for treatment of infants and young children. Adverse effects have been reported, but with careful consideration of appropriate thickener types, desired thickening consistency, and follow-up in collaboration with feeding specialists, most patients have symptomatic improvements.

Summary

Thickeners are typically well tolerated and with few side effects but close follow-up is needed to make sure patients tolerate thickeners and have adequate symptom improvement.

Keywords: thickening, oropharyngeal dysphagia, aspiration, gastroesophageal reflux disease, regurgitation, pediatrics

Introduction

Thickened feeding is commonly used in pediatric clinical practice as a simple approach to treat both gastroesophageal reflux and oropharyngeal dysphagia in infants and young children (1, 2). Both of these diagnoses are frequently encountered in both pediatric gastroenterology and general pediatric practice and the symptoms of both commonly overlap; therefore, all providers should be familiar with an approach to thickening as an initial therapy for both conditions (3-7). For the purposes of this review, we will focus on thickening of feeds in children less than 2 years of age, when reflux and oropharyngeal dysphagia are most prevalent.

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is the physiologic passage of gastric contents into the esophagus, most frequently during transient relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter (8, 9). GER becomes gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) when the reflux causes troublesome signs or symptoms such as significant discomfort, poor weight gain, or airway symptoms (10). Symptoms have traditionally been attributed to acid, based on adult studies, but refluxate is primarily non-acid in infants and young children (11-14). Therefore, acid suppressive medications such as proton pump inhibitors and H2-receptor antagonist medications are both ineffective in controlling reflux and have been associated with adverse effects including increased risk of respiratory and gastrointestinal infections (15-23). Current GERD guidelines from NASPGHAN and ESPGHAN recommend thickening as the first-line approach to treat GERD in infants and young children (1). From a reflux perspective, thickening of feeds reduces the number of regurgitation episodes in multiple studies, supporting the new guidelines(1, 2, 24-27).

Thickening is also used to treat oropharyngeal dysphagia with aspiration, a common cause of feeding difficulties in infants with an apparently increasing prevalence, due to increased recognition of symptoms in otherwise healthy infants and toddlers and improved survival of premature infants and other children with medical complexity (7, 28). For swallowing, thickening changes the swallow mechanics and improves pacing, allowing the bolus to move more slowly from the oropharynx into the esophagus and improving both oromotor control and airway protection (29, 30).

Given the risks of pharmacologic approaches, thickening is the first line treatment for both the continuum of pediatric reflux-GERD and swallowing dysfunction. It is the goal of this paper to review the strengths and limitations of thickeners in the pediatric population.

Evidence for Thickener Efficacy

Thickening of feeds is a simple intervention that can be recommended by a variety of pediatric providers and trialed in the office. A number of studies have evaluated the efficacy of thickeners for both pediatric reflux and oropharyngeal dysphagia, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1:

Studies of Thickener Efficacy for Pediatric Reflux and Oropharyngeal Dysphagia

| Study | Study Design |

Outcome | Thickener | Reported Effect |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastroesophageal Reflux | Orenstein, J Pediatr 1987 | Prospective trial | Scintigraphy and observation of regurgitation | Cereal | Reflux similar by scintigraphy but emesis, gastric emptying, crying time and time awake decreased |

| Wenzl, Pediatrics 2003 | Prospective crossover study | Reflux by impedance | Cereal | Regurgitation frequency, regurgitation amount and refluxate height decreased with thickening | |

| Corvaglia, J Pediatr 2006 | Prospective crossover study | Reflux by impedance in premature infants | Pre-cooked starch | Breastmilk thickened with starch ineffective at reducing reflux | |

| Chao, Nutrition 2007 | RCT | Regurgitation by scintigraphy | Cereal | Thickening more effective than upright positioning to reduce regurgitation frequency | |

| Horvath, Pediatrics 2008 | Meta-analysis | Regurgitation and impedance | Varied thickeners included | Thickening moderately effective for reflux | |

| Kwok, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017 | Systematic review | Regurgitation and impedance | Varied thickeners included | Moderate effectiveness for persistent regurgitation in bottle-fed infants | |

| Oropharyngeal Dysphagia | Khoshoo, Pediatr Pulm 2001 | Prospective trial | Swallow function with thickened feeds in infants with bronchiolitis | Cereal | Swallow function improved with thickened feeds in infants with bronchiolitis |

| Dion, Dysphagia 2015 | Survey of Canadian clinicians | Practice patterns in recommending/using thickened liquids | Varied thickeners included | Thickened liquids used broadly but practice varied | |

| Madhoun, J Neonatal Nurs 2015 | Survey of NICU providers | Practice patterns in recommending and using thickened liquids in NICU | Varied thickeners included | Variability in recommendations and use of thickeners in NICU | |

| McSweeney, J Pediatr 2016 | Retrospective cohort study | Hospitalization risk for thickened liquids compared to gastrostomy feeds | Varied thickeners included | Fewer admissions with thickening compared to gastrostomy feeds | |

| Coon, Hosp Pediatr 2016 | Retrospective database study | ER visit or hospitalization for acute respiratory infection | Not specified | Decreased acute respiratory infection with thickening for infants with silent aspiration | |

| Krummrich, Pediatr Pulm 2017 | Prospective cohort study | Parent reported improvements in symptoms | Varied thickeners included | Improved symptoms and oral liquid intake with thickening | |

| Duncan, J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2018 | Retrospective cohort study | Symptom improvement, hospitalization risk | Not specified | Decreased symptoms and hospitalization for infants with laryngeal penetration |

For gastroesophageal reflux, the mechanism is not well described but it is hypothesized that thickeners work by moving feeds to the antrum, away from the cardia and lower esophageal sphincter, thereby reducing the amount of refluxate into the esophagus. Furthermore, the increased viscosity of the refluxate from thickeners may reduce the amount of reflux traveling all of the way up into the oropharynx (1). A variety of studies have used clinical measures, including regurgitation frequency and impedance studies to demonstrate the impact of thickening for treating reflux (2, 24-27, 31). While some studies have suggested that thickened feeds might result in slower gastric emptying, others have refuted this; it might be that delayed gastric emptying depends on the type and concentration of thickener that is used (32, 33). These studies are summarized in Table 1.

A number of studies have evaluated the effectiveness of thickeners in oropharyngeal dysphagia, and have shown that they slow oropharyngeal bolus transit and improve bolus cohesion. (34-37). Coon et al showed in a large database study that thickening reduces acute respiratory illness hospitalizations and emergency department visits in infants with silent aspiration (38) Krummrich surveyed parents of children receiving thickened feeds for oropharyngeal dysphagia and found that most symptoms were improved after thickening (39). In addition, we have previously shown that, even in infants with mild swallowing abnormalities (e.g. isolated laryngeal penetration), thickening is associated with symptom improvement and decreased hospitalization risk (40). Thickening of feeds can even reduce the need for gastrostomy tube placement in children with aspiration; McSweeney found that patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia that were treated with thickened feeds had fewer hospitalizations compared to those fed by gastrostomy, due to reduced frequency of respiratory infections in children receiving thickened feeds, along with increased reflux and gastrostomy complications in patients who underwent gastrostomy placement (41). These studies are summarized in Table 1.

Types of Thickeners

There are a variety of thickeners that can be used in pediatric practice, ranging from food based thickeners to commercial thickeners. Other authors have recently discussed the utility of commercially available pre-thickened formulas, but it is important to keep in mind that some of these formulas are activated by acid and therefore only thicken once they reach the stomach; while this is helpful for gastroesophageal reflux, this delayed thickening does not help oropharyngeal dysphagia (42). Therefore, it is important to know which products are designed to treat gastroesophageal reflux versus oropharyngeal dysphagia. Characteristics of each of the thickeners are shown in Table 2.

Table 2:

Thickener Types and Characteristics

| Thickener Type |

Primary Ingredient |

Calories | Can Thicken Breastmilk |

Approved Age/Weight |

Limitations/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice Cereal | Rice | 5 kcal per teaspoon of cereal | No | No restriction | Cannot be used for breastmilk, change in bowel movements, arsenic concern |

| Oatmeal Cereal | Oatmeal | 5 kcal per teaspoon of cereal | No | No restriction | Cannot be used for breastmilk, increased risk of nipple clogs |

| Other Grain Cereals | Varies | Varies depending on grain | No | No restriction | Cannot be used for breastmilk, nutritional considerations and consistencies vary depending on grain |

| GelMix | Carob bean gum | Adds 5 kcal per ounce for nectar consistency | Yes | >42 weeks corrected age, weight >6 lbs | Heating required for thickening but can be used for breast milk |

| SimplyThick | Xanthan gum | Adds 5 kcal per ounce for nectar consistency | Yes | >12 months – 3 years corrected age depending on institution | Case reports of NEC. and new recipe includes soluble fiber |

| Thick-It | Corn Starch | Adds 4 kcal per ounce for nectar consistency | No | >12 months corrected age | Grainy texture reported, GI upset more common |

| Purathick | Tara gum | Adds 2 kcal per ounce for nectar consistency | Yes | >12 months corrected age | Thickens both hot and cold liquids |

| Food Purees | Fruit, vegetable, yogurt, other pureed foods | Varies depending on foods used | Yes | Typically after 4 months of age | Important to work with dietician and feeding specialist to insure appropriate nutritional content and consistency |

Cereal thickeners

Infant cereal has been used for years to treat both gastroesophageal reflux and oropharyngeal dysphagia. While the anti-reflux formulas treat only GERD, adding cereal to formula immediately prior to feeding treats both. There are multiple cereal options on the market, though the most commonly used for thickening are infant rice cereal and infant oatmeal. These cereals are inexpensive, readily available, and the side effect profiles are well known. While cereals are very effective in thickening formula, they are dissolved by amylases in breastmilk so cannot be used as a breast milk thickener. Because rice cereal can also be used to add calories, feeds volumes might decrease, which might also have a beneficial effect on reflux. Consultation with a speech-language pathologist or other feeding specialist is recommended to determine the appropriate amount of cereal needed per fluid ounce.

Puree thickeners

Fruit purees such as baby food and/or yogurt can be used as thickeners in addition to cereal or alone in some infants or toddlers. As with cereal, the nutritional content and additional calories of the additives need to be weighed against the pros and cons of commercial thickeners and it is important to work with feeding and nutrition specialists to make sure liquid consistencies are appropriate, can be extracted from the bottle or cup, and have appropriate nutritional profiles.

Commercial thickeners

There are several thickeners used frequently in pediatrics: xanthan gum-based, carob-based, and cornstarch-based thickeners. While no commercial thickeners are approved for preterm infants, recently several have been marketed to infants greater than 42-weeks corrected gestational age. Advantages and disadvantages of these thickeners are shown in Table 2. The most significant advantage of carob- and xanthan gum-based thickeners is that they allow for thickening of breast milk, although these are not without risk, with recent concerns raised about the impact of these thickeners on the pediatric microbiome.

Regardless of which thickener is used, it is essential to work with a speech-language pathologist, occupational therapist, or other pediatric feeding specialist to ensure that thickened liquid can be extracted from the bottle nipple and is being made correctly (43). Nipples should not be enlarged to improve extraction as the degree of enlargement is variable and can actually worsen risk of aspiration. In addition, some thickeners require heating, some thicken more over time, and some are at greater risk for clumping, so working with specialists who are familiar with the nuances of the products is critical. Finally, some thickeners are expensive and are not covered by insurance, leading families to switch thickeners away from a recommended one; hence close follow up is important. A number of studies have also examined the effects of heat, time, and even the barium used in swallow studies on actual liquid consistency and therefore it is important to reassess symptoms if a given consistency is not helping as expected (44, 45).

How Much to Thicken

It is important to consider to what extent feeds should be thickened, since providers may not be aware of differences between degrees of thickening (30, 35). For gastroesophageal reflux, thickening recipes are usually less thick than what is required for oropharyngeal dysphagia. Most providers start with 1 teaspoon of cereal per ounce of formula (1). For oropharyngeal dysphagia, the care team would ideally determine the safest level of thickness needed to avoid aspiration or laryngeal penetration during the videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS); patients may be safe to take thin liquids, ½ nectar thick consistency, nectar thick consistency, honey thick consistency, or purees (46). However, providers should recognize that patients may need more thickening than suggested by the VFSS if patients are still symptomatic, as the VFSS represents a single point in time assessment.

Depending on the level of thickness, different nipple sizes may be needed; commercial bottle companies make a variety of nipples with different flow rates to prevent the need for manual enlargement(43). For older children, straw cups, spouted sippy cups, puree pouches, and other feeding equipment offer other methods of feeding thickened liquids. Regardless of which approach is taken, it is important to work closely in a multidisciplinary team to determine the most effective method that is also the safest.

Practical Considerations When Using Thickener

As previously discussed, whenever using thickener, clinical follow-up is needed to make sure that patients tolerate the thickener and degree of thickening, with adequate improvement in symptoms and minimal adverse effects.

As shown in Table 2, most thickeners are food-based and alter the nutritional profiles of feeds, and so providers must also consider calories being added with thickener and if possible work in collaboration with a dietician. There are additional osmolality considerations in higher calorie formulas and adding thickener may in some cases have unintended nutritional consequences (47). These issues are particularly important to consider in premature infants and other children with growth concerns, since these patients often require both supplemental calories and thickening of feeds and might also have renal dysfunction that should particularly be considered when altering osmolality profiles. It is important to note that hyperosmolar feeds can delay gastric emptying, prolong intestinal transmit and result in increased vomiting (48).

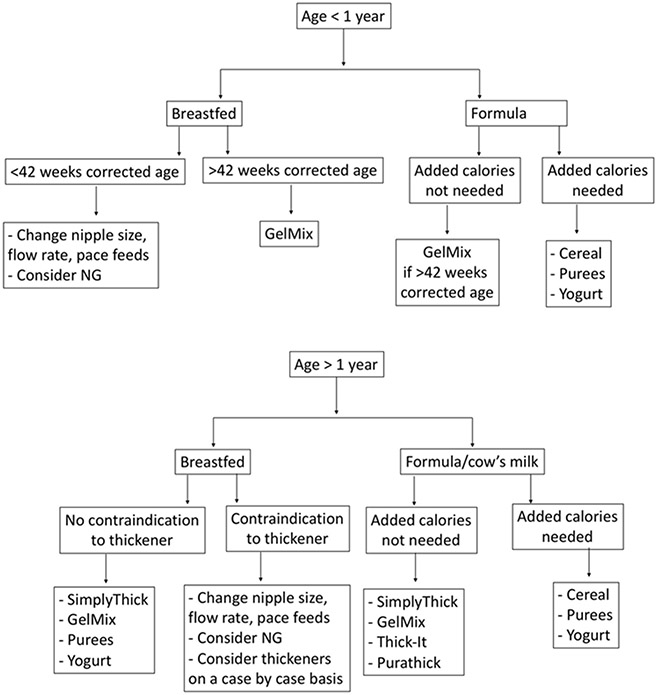

Even when thickeners are effective at controlling symptoms and have minimal side effects, providers should consider how long to utilize them in a given patient and how best to wean liquid consistency. Controversy exists in how best to wean thickeners for infants and young children who would be expected to have improvement in their symptoms, with some groups suggesting empiric weaning with only clinical evaluation of symptoms and others advocating repeat swallow studies (49, 50). Given the high prevalence of silent aspiration in infants and young children, observation of symptoms during weaning is not always reliable, so repeating VFSS is important for patients with silent aspiration (51). A suggested clinical algorithm for thickening feeds for infants and young children is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Clinical Algorithm for Thickening Feeds for Infants and Young Children.

Note: Contraindications to thickener include history of necrotizing enterocolitis and disorders leading to poor intestinal perfusion, such as congenital heart disease.

Safety Considerations

The potential benefits, mechanisms of effect, and considerations for optimizing thickener use in infants and young children have been discussed. However, concerns have been raised about risk of thickeners in infants, including arsenic exposure, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), dehydration, decreased intake, and constipation, and these concerns sometimes limit their use in clinical practice (52, 53). An understanding of the evidence for these concerns and how to mitigate the possible risks of thickeners can help providers to be more accepting of their use in appropriate clinical settings.

Arsenic Exposure

Since infant rice cereal is typically the least expensive and most accessible thickener, it has traditionally been the first choice for use in the treatment of both reflux and oropharyngeal dysphagia. However, reports from the FDA and studies over the last few years have issued warnings about possible inorganic arsenic exposure from rice, which has been linked to increased risk of cancer and neurotoxicity. The warnings were initially based on data from countries where there was high level, sustained arsenic exposure, due to high dietary rice intake in areas with industrial contamination and other naturally occurring sources of arsenic (54-56). However, cross-sectional studies in the United States have shown increased arsenic exposures in infants who ate rice-based products in their first year compared to those who did not, and overall this might be of particular concern in young infants (57, 58). Exposure assessments have also suggested that rice cereal is the largest potential source of arsenic in infants and toddlers but formula and drinking water are also significant sources and specific cereals can have varying amounts of arsenic (57, 59, 60). Additionally, studies of urine arsenic metabolites suggest that formula fed infants overall have higher arsenic metabolite levels compared to breastfed infants and that weaning from milk to solid foods results in higher arsenic exposure, suggesting that rice cereal but also other foods could be of concern(61, 62). The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) weighed in on this issue in their own statements and as a result more and more families have expressed concern about using rice cereal as a thickener, particularly in infants who require thickened feeds for an extended time. There remains a lack of longitudinal studies in this population and no studies have evaluated long term risks from exposure in infancy(63, 64). Whenever possible, our recommendation is to use infant cereal with no or low arsenic and our hope would be that with increased awareness and FDA regulation, infant cereal and other foods will have minimal arsenic levels (65). Current AAP recommendations are to limit rice consumption by encouraging infants and young children to eat a variety of foods; the AAP also recommends following the Consumer Reports suggested intake of ¾ cup of infant rice cereal per day(66, 67). This is the equivalent of 36 teaspoons of rice cereal per day and therefore an infant receiving standard thickening for reflux taking less than 36 ounces per day would be under this threshold, but infants with oropharyngeal dysphagia receiving thicker consistencies or taking higher volumes of formula per day might exceed this threshold, depending on the liquid consistency required. In the approach to using rice cereal and discussions with patient families, providers must try to balance these potential risks with the clear risks of untreated oropharyngeal dysphagia or troublesome symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux, along with the other potential risks that must be considered with non-cereal based thickeners(68).

Necrotizing Enterocolitis

One of the earliest concerns about commercial thickeners in particular has been the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) following case reports of premature infants experiencing NEC after receiving feeds thickened with SimplyThick and Carobel (69-71). Clarke described the first cases, two infants born at 25 weeks who were established on full feeds and had onset of NEC at days 26 and 30 of life after receiving feeds thickened with Carobel, a carob bean gum based thickener; both infants died. Woods described 3 cases of late-onset colonic NEC in premature infants born at 24-28 weeks that all occurred after the second postnatal month after receiving feeds thickened with SimplyThick (71). Beal reviewed 22 cases of NEC that occurred in infants receiving SimplyThick; of these, 21 of the infants were premature and median onset of NEC occurred at 66 days of life, with 50% of cases occurring at home (69). The mechanism behind this association is not known but microbiome alterations and changes in intestinal transit time may play a role (71-73). Because of these case reports, SimplyThick is packaged as a thickener for children older than 12 years of age without the consultation of a healthcare professional. However, many institutions are using it in low risk children as young as 12 months with close follow up. Contraindications to thickener may include history of necrotizing enterocolitis and disorders leading to poor intestinal perfusion, such as congenital heart disease. Young patients should be monitored for diarrhea, abdominal distension, or other signs of gastrointestinal distress.

Dehydration

Perhaps one of the most common concerns about the use of thickeners is the presumed risk for dehydration in infants and young children; there is a misconception that by thickening liquids, there is a reduction in free water even when the total ingested volume is the same. Providers also sometimes worry about free water availability in thickened liquids, but studies have shown that there is no difference in water absorption for patients taking thickened liquids (74). Another concern raised by families is the worry that children will drink less because of the additional calories added with some thickeners. However, Krummrich reported increased liquid intake after receiving thickening, perhaps since thickened liquids are better tolerated in patients with swallowing difficulty, which could perhaps be attributed to fewer unpleasant symptoms during or after feeding with adequate treatment of reflux and/or oropharyngeal dysphagia(39).

Change in Bowel Movement Consistency

Depending on the thickening agent, patients may report changes in bowel movement consistency. Some thickeners (e.g. rice cereal) have been associated with constipation, while others have been associated with diarrhea (e.g. SimplyThick which has added fiber or fruit puree with increased fructose load). Studies that have looked at this directly have found that only 20% of infants receiving rice cereal for thickening actually experience constipation (75). Even in these cases, there are several options that could be considered if stooling changes are problematic: one could switch from rice cereal to oatmeal or to a commercial thickener, and if there are continuing issues with constipation, then prune juice, lactulose, or another stool softener could be considered.

Conclusions

Thickeners are effective and frequently used empirically to treat both reflux and swallowing disorders. From a GERD perspective, the risks of thickening need to be weighed against other GERD therapies but because of their safety profile, thickening is first line therapy before acid suppression. From an oropharyngeal dysphagia perspective, the alternative to thickening would involve continued aspiration with increased pulmonary morbidity, hospitalizations, and ER visits in addition to increased placement of enteral tubes; again the thickening safety profile relative to the alternatives is favorable. It is important to work closely with a speech-language pathologist or other feeding specialist if possible and also to make sure all patients have close follow-up to ensure both tolerance of thickening and adequate symptom improvement.

Source of Funding and Conflict of Interest Statement

This work was supported by The Translational Research Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, NIH R01 DK097112-01, and NIH T32 DK007477-33. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Rosen R, Vandenplas Y, Singendonk M, Cabana M, DiLorenzo C, Gottrand F, et al. Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2018;66(3):516–54. NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN pediatric reflux guidelines, including suggested clinical algorithms, discussion of thickening and other approaches including hypoallergenic diet and anti-reflux medications.

- 2.Orenstein SR, Magill HL, Brooks P. Thickening of infant feedings for therapy of gastroesophageal reflux. The Journal of pediatrics. 1987;110(2):181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jadcherla S Dysphagia in the high-risk infant: potential factors and mechanisms. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2016;103(2):622s–8s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Funderburk A, Nawab U, Abraham S, DiPalma J, Epstein M, Aldridge H, et al. Temporal Association Between Reflux-like Behaviors and Gastroesophageal Reflux in Preterm and Term Infants. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2016;62(4):556–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prasse JE, Kikano GE. An overview of pediatric dysphagia. Clinical pediatrics. 2009;48(3):247–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gold BD. Review article: epidemiology and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux in children. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2004;19 Suppl 1:22–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horton J, Atwood C, Gnagi S, Teufel R, Clemmens C. Temporal Trends of Pediatric Dysphagia in Hospitalized Patients. Dysphagia. 2018;33(5):655–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campanozzi A, Boccia G, Pensabene L, Panetta F, Marseglia A, Strisciuglio P, et al. Prevalence and natural history of gastroesophageal reflux: pediatric prospective survey. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):779–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Omari TI, Barnett CP, Benninga MA, Lontis R, Goodchild L, Haslam RR, et al. Mechanisms of gastro-oesophageal reflux in preterm and term infants with reflux disease. Gut. 2002;51(4):475–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orenstein SR. Controversies in pediatric gastroesophageal reflux. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 1992;14(3):338–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen R Gastroesophageal reflux in infants: more than just a pHenomenon. JAMA pediatrics. 2014;168(1):83–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orenstein SR, Shalaby TM, Kelsey SF, Frankel E. Natural history of infant reflux esophagitis: symptoms and morphometric histology during one year without pharmacotherapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(3):628–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mainie I, Tutuian R, Shay S, Vela M, Zhang X, Sifrim D, et al. Acid and non-acid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms despite acid suppressive therapy: a multicentre study using combined ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring. Gut. 2006;55(10):1398–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyle JT. Acid secretion from birth to adulthood. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37 Suppl 1:S12–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown KE, Knoderer CA, Nichols KR, Crumby AS. Acid-Suppressing Agents and Risk for Clostridium difficile Infection in Pediatric Patients. Clinical pediatrics. 2015;54(11):1102–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canani RB, Cirillo P, Roggero P, Romano C, Malamisura B, Terrin G, et al. Therapy with gastric acidity inhibitors increases the risk of acute gastroenteritis and community-acquired pneumonia in children. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):e817–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freedberg DE, Lamouse-Smith ES, Lightdale JR, Jin Z, Yang YX, Abrams JA. Use of Acid Suppression Medication is Associated With Risk for C. difficile Infection in Infants and Children: A Population-based Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(6):912–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freedberg DE, Toussaint NC, Chen SP, Ratner AJ, Whittier S, Wang TC, et al. Proton Pump Inhibitors Alter Specific Taxa in the Human Gastrointestinal Microbiome: A Crossover Trial. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(4):883–5 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graham PL 3rd, Begg MD, Larson E, Della-Latta P, Allen A, Saiman L. Risk factors for late onset gram-negative sepsis in low birth weight infants hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2006;25(2):113–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manzoni P, Garcia Sanchez R, Meyer M, Stolfi I, Pugni L, Messner H, et al. Exposure to Gastric Acid Inhibitors Increases the Risk of Infection in Preterm Very Low Birth Weight Infants but Concomitant Administration of Lactoferrin Counteracts This Effect. The Journal of pediatrics. 2018;193:62–7.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosen R, Amirault J, Liu H, Mitchell P, Hu L, Khatwa U, et al. Changes in gastric and lung microflora with Acid suppression: Acid suppression and bacterial growth. JAMA pediatrics. 2014;168(10):932–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stark CM, Nylund CM. Side Effects and Complications of Proton Pump Inhibitors: A Pediatric Perspective. The Journal of pediatrics. 2016;168:16–22. Review of the recent literature on multiple adverse effects associated with proton pump inhibitor use in pediatrics.

- 23.Duncan DR, Mitchell PD, Larson K, McSweeney ME, Rosen RL. Association of Proton Pump Inhibitors With Hospitalization Risk in Children With Oropharyngeal Dysphagia. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chao HC, Vandenplas Y. Effect of cereal-thickened formula and upright positioning on regurgitation, gastric emptying, and weight gain in infants with regurgitation. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif). 2007;23(1):23–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horvath A, Dziechciarz P, Szajewska H. The effect of thickened-feed interventions on gastroesophageal reflux in infants: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):e1268–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwok TC, Ojha S, Dorling J. Feed thickener for infants up to six months of age with gastro-oesophageal reflux. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017;12:Cd003211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wenzl TG, Schneider S, Scheele F, Silny J, Heimann G, Skopnik H. Effects of thickened feeding on gastroesophageal reflux in infants: a placebo-controlled crossover study using intraluminal impedance. Pediatrics. 2003;111(4 Pt 1):e355–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duffy KL. Dysphagia in Children. Current problems in pediatric and adolescent health care. 2018;48(3):71–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldfield EC, Smith V, Buonomo C, Perez J, Larson K. Preterm infant swallowing of thin and nectar-thick liquids: changes in lingual-palatal coordination and relation to bolus transit. Dysphagia. 2013;28(2):234–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steele CM, Alsanei WA, Ayanikalath S, Barbon CE, Chen J, Cichero JA, et al. The influence of food texture and liquid consistency modification on swallowing physiology and function: a systematic review. Dysphagia. 2015;30(1):2–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corvaglia L, Ferlini M, Rotatori R, Paoletti V, Alessandroni R, Cocchi G, et al. Starch thickening of human milk is ineffective in reducing the gastroesophageal reflux in preterm infants: a crossover study using intraluminal impedance. The Journal of pediatrics. 2006;148(2):265–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyazawa R, Tomomasa T, Kaneko H, Morikawa A. Effect of formula thickened with locust bean gum on gastric emptying in infants. Journal of paediatrics and child health. 2006;42(12):808–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyazawa R, Tomomasa T, Kaneko H, Arakawa H, Morikawa A. Effect of formula thickened with reduced concentration of locust bean gum on gastroesophageal reflux. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). 2007;96(6):910–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dion S, Duivestein JA, St Pierre A, Harris SR. Use of Thickened Liquids to Manage Feeding Difficulties in Infants: A Pilot Survey of Practice Patterns in Canadian Pediatric Centers. Dysphagia. 2015;30(4):457–72. Survey study of use of thickening in Canadian pediatric providers, finding that thickened liquids are used broadly but the practice varies.

- 35. Madhoun LL, Siler-Wurst KK, Sitaram S, Jadcherla SR. Feed-Thickening Practices in NICUs in the Current Era: Variability in Prescription and Implementation Patterns. Journal of neonatal nursing : JNN. 2015;21(6):255–62. Survey study of use of thickening in the NICU, finding that there is variability in the use of thickening in the NICU.

- 36.Khoshoo V, Ross G, Kelly B, Edell D, Brown S. Benefits of thickened feeds in previously healthy infants with respiratory syncytial viral bronchiolitis. Pediatric pulmonology. 2001;31(4):301–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rofes L, Arreola V, Mukherjee R, Swanson J, Clave P. The effects of a xanthan gum-based thickener on the swallowing function of patients with dysphagia. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2014;39(10):1169–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coon ER, Srivastava R, Stoddard GJ, Reilly S, Maloney CG, Bratton SL. Infant Videofluoroscopic Swallow Study Testing, Swallowing Interventions, and Future Acute Respiratory Illness. Hospital pediatrics. 2016;6(12):707–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Krummrich P, Kline B, Krival K, Rubin M. Parent perception of the impact of using thickened fluids in children with dysphagia. Pediatric pulmonology. 2017;52(11):1486–94. Survey of parents, showing improved symptoms in infants with oropharyngeal dysphagia after receiving thickened feeds.

- 40.Duncan DR, Larson K, Davidson K, May K, Rahbar R, Rosen RL. Feeding Interventions are Associated with Improved Outcomes in Children with Laryngeal Penetration. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McSweeney ME, Kerr J, Amirault J, Mitchell PD, Larson K, Rosen R. Oral Feeding Reduces Hospitalizations Compared with Gastrostomy Feeding in Infants and Children Who Aspirate. The Journal of pediatrics. 2016;170:79–84. Retrospective study finding that outcomes are improved with oral thickened feeds compared to gastrostomy feeds in children with aspiration.

- 42. Salvatore S, Savino F, Singendonk M, Tabbers M, Benninga MA, Staiano A, et al. Thickened infant formula: What to know. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif). 2018;49:51–6. Recent review of considerations and recommendations for use of thickened formulas for infants with reflux.

- 43. Pados BF, Park J, Dodrill P. Know the Flow: Milk Flow Rates From Bottle Nipples Used in the Hospital and After Discharge. Advances in neonatal care : official journal of the National Association of Neonatal Nurses. 2018. Study that evaluated flow rates from commercial bottle nipple sizes, showing great variability in flow rates.

- 44.Gosa MM, Dodrill P. Effect of Time and Temperature on Thickened Infant Formula. Nutrition in clinical practice : official publication of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2017;32(2):238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoon SN, Yoo B. Rheological Behaviors of Thickened Infant Formula Prepared with Xanthan Gum-Based Food Thickeners for Dysphagic Infants. Dysphagia. 2017;32(3):454–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arvedson JC, Lefton-Greif MA. Instrumental Assessment of Pediatric Dysphagia. Seminars in speech and language. 2017;38(2):135–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Levy DS, Osborn E, Hasenstab KA, Nawaz S, Jadcherla SR. The Effect of Additives for Reflux or Dysphagia Management on Osmolality in Ready-to-Feed Preterm Formula: Practice Implications. JPEN Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition. 2018. Evaluation of the effect of thickeners on formula osmolality, emphasizing the importance of considering potential effects of increasing osmolality on feeding tolerance and safety.

- 48.Jadcherla SR, Berseth CL. Acute and chronic intestinal motor activity responses to two infant formulas. Pediatrics. 1995;96(2 Pt 1):331–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolter NE, Hernandez K, Irace AL, Davidson K, Perez JA, Larson K, et al. A Systematic Process for Weaning Children With Aspiration From Thickened Fluids. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wentland C, Hersh C, Sally S, Fracchia MS, Hardy S, Liu B, et al. Modified Best-Practice Algorithm to Reduce the Number of Postoperative Videofluoroscopic Swallow Studies in Patients With Type 1 Laryngeal Cleft Repair. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2016;142(9):851–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Duncan DR, Mitchell PD, Larson K, Rosen RL. Presenting Signs and Symptoms do not Predict Aspiration Risk in Children. The Journal of pediatrics. 2018;201:141–6. Retrospective study showing no association between presenting symptoms and finding of aspiration on VFSS, highlighting high prevalence of silent aspiration in infants and young children.

- 52.Cichero JA. Thickening agents used for dysphagia management: effect on bioavailability of water, medication and feelings of satiety. Nutrition journal. 2013;12:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith CH, Jebson EM, Hanson B. Thickened fluids: investigation of users' experiences and perceptions. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2014;33(1):171–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rahman A, Vahter M, Ekstrom EC, Persson LA. Arsenic exposure in pregnancy increases the risk of lower respiratory tract infection and diarrhea during infancy in Bangladesh. Environmental health perspectives. 2011;119(5):719–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raqib R, Ahmed S, Sultana R, Wagatsuma Y, Mondal D, Hoque AM, et al. Effects of in utero arsenic exposure on child immunity and morbidity in rural Bangladesh. Toxicology letters. 2009;185(3):197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schmidt CW. In search of "just right": the challenge of regulating arsenic in rice. Environmental health perspectives. 2015;123(1):A16–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shibata T, Meng C, Umoren J, West H. Risk Assessment of Arsenic in Rice Cereal and Other Dietary Sources for Infants and Toddlers in the U.S. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2016;13(4):361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Karagas MR, Punshon T, Sayarath V, Jackson BP, Folt CL, Cottingham KL. Association of Rice and Rice-Product Consumption With Arsenic Exposure Early in Life. JAMA pediatrics. 2016;170(6):609–16. Cross-sectional study of urinary arsenic, showing higher levels in infants exposed to rice products.

- 59.Carignan CC, Cottingham KL, Jackson BP, Farzan SF, Gandolfi AJ, Punshon T, et al. Estimated exposure to arsenic in breastfed and formula-fed infants in a United States cohort. Environmental health perspectives. 2015;123(5):500–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Juskelis R, Li W, Nelson J, Cappozzo JC. Arsenic speciation in rice cereals for infants. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry. 2013;61(45):10670–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Signes-Pastor AJ, Cottingham KL, Carey M, Sayarath V, Palys T, Meharg AA, et al. Infants' dietary arsenic exposure during transition to solid food. Scientific reports. 2018;8(1):7114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Signes-Pastor AJ, Woodside JV, McMullan P, Mullan K, Carey M, Karagas MR, et al. Levels of infants' urinary arsenic metabolites related to formula feeding and weaning with rice products exceeding the EU inorganic arsenic standard. PloS one. 2017;12(5):e0176923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Young JL, Cai L, States JC. Impact of prenatal arsenic exposure on chronic adult diseases. Systems biology in reproductive medicine. 2018;64(6):469–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Farzan SF, Karagas MR, Chen Y. In utero and early life arsenic exposure in relation to long-term health and disease. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2013;272(2):384–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nachman KE, Ginsberg GL, Miller MD, Murray CJ, Nigra AE, Pendergrast CB. Mitigating dietary arsenic exposure: Current status in the United States and recommendations for an improved path forward. The Science of the total environment. 2017;581-582:221–36. An approach to mitigate dietary arsenic exposure using a relative source contribution-based approach at different life stages.

- 66.FDA concludes study of arsenic in rice products; no dietary changes recommended. AAP News. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arsenic in your food: our findings show a real need for federal standards for this toxin. Consumer reports. 2012;77(11):22–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Piccione JC, McPhail GL, Fenchel MC, Brody AS, Boesch RP. Bronchiectasis in chronic pulmonary aspiration: risk factors and clinical implications. Pediatric pulmonology. 2012;47(5):447–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beal J, Silverman B, Bellant J, Young TE, Klontz K. Late onset necrotizing enterocolitis in infants following use of a xanthan gum-containing thickening agent. The Journal of pediatrics. 2012;161(2):354–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clarke P, Robinson MJ. Thickening milk feeds may cause necrotising enterocolitis. Archives of disease in childhood Fetal and neonatal edition. 2004;89(3):F280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Woods CW, Oliver T, Lewis K, Yang Q. Development of necrotizing enterocolitis in premature infants receiving thickened feeds using SimplyThick(R). Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2012;32(2):150–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gamage H, Tetu SG, Chong RWW, Ashton J, Packer NH, Paulsen IT. Cereal products derived from wheat, sorghum, rice and oats alter the infant gut microbiota in vitro. Scientific reports. 2017;7(1):14312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gonzalez-Bermudez CA, Lopez-Nicolas R, Peso-Echarri P, Frontela-Saseta C, Martinez-Gracia C. Effects of different thickening agents on infant gut microbiota. Food & function. 2018;9(3):1768–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sharpe K, Ward L, Cichero J, Sopade P, Halley P. Thickened fluids and water absorption in rats and humans. Dysphagia. 2007;22(3):193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mascarenhas R, Landry L, Khoshoo V. Difficulty in defecation in infants with gastroesophageal reflux treated with smaller volume feeds thickened with rice cereal. Clinical pediatrics. 2005;44(8):671–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]