Abstract

Bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is an important agent of induction of ocular pathology following corneal injury or wearing of contaminated contact lenses. The mechanism of LPS uptake through the corneal epithelium is unclear, and the role played by inflammatory cells in this phenomenon has not been previously assessed. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled LPS from Escherichia coli was deposited onto the abraded corneas of New Zealand White rabbits. Epifluorescence microscopy of living excised corneas revealed diffuse LPS staining in the epithelial and stromal layers only in the vicinity of the abrasion. In addition, specific cellular uptake of LPS was suggested by fluorescence staining of cells along the abrasion site. In a second series of experiments, an anti-CD18 polyclonal antibody was used to block infiltration of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) into the cornea. In these experiments, a diffuse distribution of fluorescent LPS was still observed along the abrasion, but the specific cellular uptake was abolished. The findings indicate that LPS enters the cornea via diffuse penetration at sites of injury and that specific cellular uptake of LPS occurs within the cornea via PMN which have migrated into the damaged tissue.

Complications of common ocular diseases such as conjunctivitis, keratitis, ulceration, and general inflammation may result in impaired visual function (1–3). Although bacterial colonization of the eye clearly contributes to the pathogenesis of eye disease, these disorders may also result in the absence of culturable bacteria (1), and at least in part because of host defense factors. Such disorders may be associated with contact lens wear (1–3, 6, 7, 11, 13) or with specific surgical procedures (S. P. Holland, R. Mathias, D. W. Morck, and S. Slade, submitted for publication). Indeed, overwhelming infiltration by polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) is known to play a central role in the pathogenesis of tissue damage at numerous sites, including the eye (10). Yet, the role played by these host cells in the pathogenesis of ocular disease remains unclear. Also, while lipopolysaccharide (LPS) has been shown to induce corneal damage (10), the route of entry of free LPS into the corneal tissue has yet to be clarified.

Bacterial LPS (endotoxin) can induce a variety of symptoms, including fever, reduction of blood pressure, inflammation, and tissue ulceration (8). LPS activates complement and initiates the production of numerous cytokines (8, 9). Activation of these various responses, either individually or concurrently, may cause systemic and/or localized pathology (8). Indeed, induction of the complement system may lead to the production of anaphylatoxins (C3a and C5a) and cytokines such as interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-2, which are potent proinflammatory mediators (8, 9, 14). These, in turn, amplify PMN recruitment at the sites of inflammation, hence contributing to the perpetuation of tissue injury (10). The objective of these experiments was to characterize the mechanisms of uptake of bacterial LPS at sites of corneal injury and to assess the role played by PMN in this phenomenon.

Adult New Zealand White rabbits (1.5 to 2.5 kg) were housed at the University of Calgary Life and Environmental Animal Resource Centre and provided commercial rabbit chow and water ad libitum. All animal procedures were carried out according to the guidelines of the Canadian Council of Animal Care and followed procedures approved by the University of Calgary Animal Care Ethics Committee. Rabbits were anesthetized with halothane (4%; 2 liters per min). Corneas were abraded over an approximate length of 1 cm with a sterile 26-gauge needle from the medial canthus to the lateral canthus, with care being taken to limit the depth of abrasion of the epithelial layer, as described previously (4, 10). Following the abrasion, 10 μl of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated LPS (1 mg/ml; from Escherichia coli O55:B5 (List Biological Labs Inc., Campbell, Calif.) was applied to the corneal surface with a 10-μl Hamilton syringe. At 15 min postinoculation, the animals were euthanized with an overdose of sodium pentabarbital. Corneas were removed, rinsed in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), resuspended in sterile PBS, placed in 24-well sterile tissue culture plates (Nunc), and incubated at 37°C (5% CO2) until being observed with an epifluorescence microscope, approximately 30 min postsurgery. IB4 antibody, a polyclonal antibody raised in rabbits against the PMN CD18 surface antigen, was a gift from John Wallace at the University of Calgary. This antibody is known to block CD18-dependent neutrophil extravasation (14). The antibody was delivered intravenously at a concentration of 1 mg of protein per kg of body weight in a 1-ml volume of sterile PBS, 18.25 h prior to surgery. One group of rabbits served as controls (n = 6 eyes); a second group was treated with IB4 (n = 6 eyes). In each animal, one eye was abraded while the contralateral side remained unmanipulated. Excised corneal preparations were observed with an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 25). The entire corneal surfaces were assessed for LPS staining. Observations were recorded with a Nikon 35-mm camera on 200-ASA Kodachrome film. Cells labeled with FITC-LPS were counted by using the 10× magnification lens. Cell counts were expressed as the mean number of cells per field of view under the 10× lens ± the standard error of the mean. Values were compared by one-way analysis of variance and the Student Newman-Keuls test for multiple comparisons. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

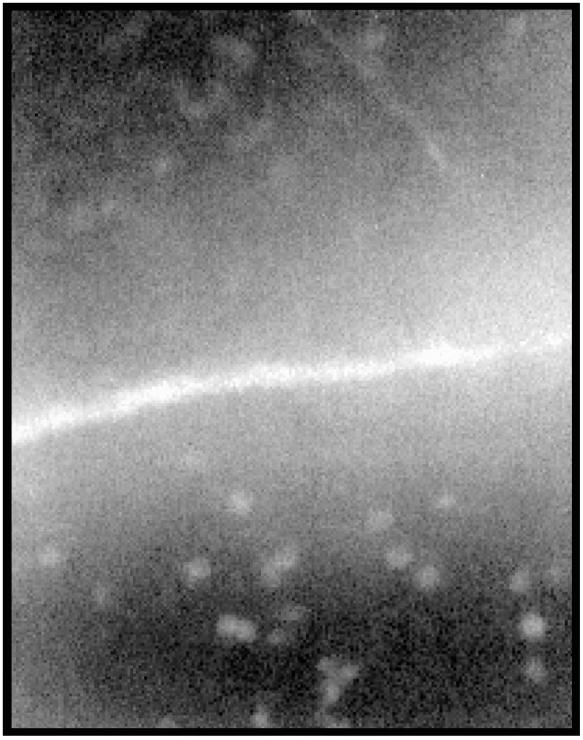

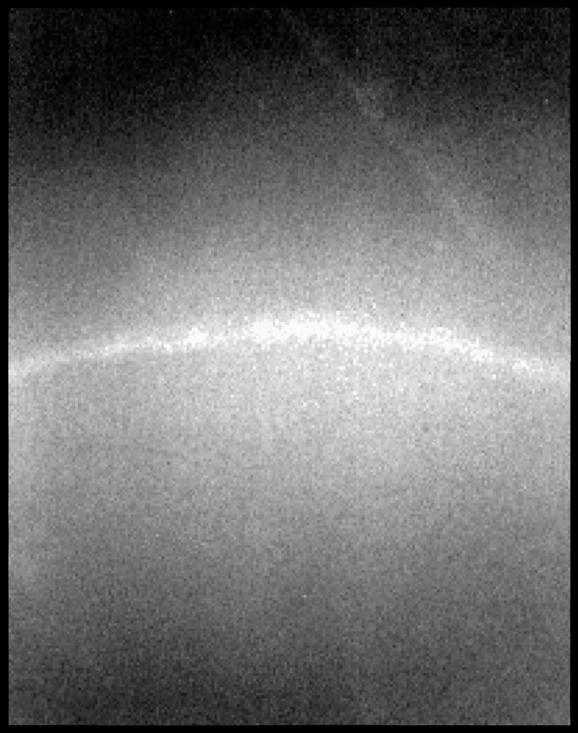

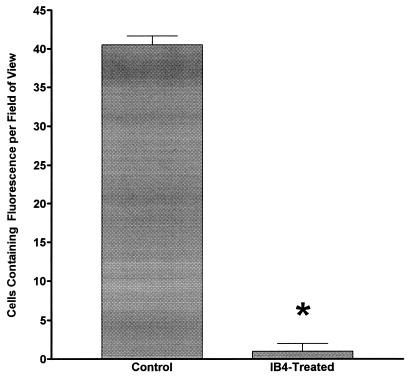

Results from microscopic observations are illustrated in Fig. 1 and 2. Diffuse fluorescence was detected along the line of abrasion for all preparations, but not in intact areas of the corneal surface. In addition, within control animals not exposed to IB4, specific cells labeled with fluorescent LPS were detected (Fig. 1). No staining was seen in nonabraded corneal areas (data not shown). Intravenous IB4 treatment abolished cell-specific FITC-LPS staining but did not alter the diffuse staining along the abrasion line (Fig. 2). As was observed in controls, FITC-LPS staining was restricted to abrasion sites. In all animals, no staining was detected on the nonabraded contralateral eye exposed to FITC-LPS and no specific uptake of FITC-LPS by cells could be detected (data not shown). Cell counts were performed to determine the number of cells specifically taking up FITC-LPS per field of view. The results of these FITC-LPS-labeled cell counts are illustrated in Fig. 3. IB4 treatment abolished cell-specific FITC-LPS labeling.

FIG. 1.

A photomicrograph of an abraded rabbit cornea that was exposed to FITC-LPS immediately following abrasion. Note the diffuse staining of the corneal stroma adjacent to the abrasion and the concentration of fluorescence staining by cells within the corneal stroma or on the surface of the cornea. Magnification, ×1,000.

FIG. 2.

A photomicrograph of an IB4 antibody-exposed, abraded rabbit cornea that was exposed to FITC-LPS immediately following abrasion. Note the diffuse staining along the corneal abrasion and the complete lack of specific cellular uptake of the FITC-LPS. Magnification, ×1,000.

FIG. 3.

Cell counts from the abraded corneas of untreated FITC-LPS-exposed animals (Control) and the abraded corneas of IB4 antibody-treated, FITC-LPS-exposed animals. ∗, value is significantly lower than that of control (P < 0.05).

In summary, in an attempt to characterize the mechanism of uptake of bacterial LPS into corneal tissue, this study investigated the effects of FITC-conjugated LPS deposition onto rabbit corneas, in the presence or in the absence of epithelial abrasion. The findings indicate that LPS enters the cornea only at sites of injury and that the uptake occurs via two distinct mechanisms: (i) via passive diffusion into the injured epithelium, and (ii) via specific cellular uptake. These results are consistent with the intact corneal epithelium acting as a barrier against entry of proinflammatory soluble products. Using a CD18 antibody clearly assisted in the identification of the cells responsible for FITC-LPS uptake as PMN. These findings confirm the observations of other investigators who demonstrated that the PMN is the primary immune cell type infiltrating corneal surfaces early in inflammation of the eye (4, 10). Data presented here add to these observations evidence that the PMN acts as the sequestration cell for LPS that has entered into the cornea. PMN are responsible for the development of corneal marginal infiltrates and are a well-established feature of the pathologic changes seen in diffuse lamellar keratitis (5, 12; S. P. Holland, R. Mathias, D. W. Morck, and S. Slade, submitted for publication) (Sands of the Sahara keratitis) following laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis. Corneal marginal infiltrates are known to occur as a result of direct bacterial infection or following contact of the ocular surface with contaminated medical devices, including contact lenses (7, 16, 17), and Sands of the Sahara keratitis (5, 12; S. P. Holland, R. Mathias, D. W. Morck, and S. Slade, submitted for publication) is suspected to be caused by LPS contamination of laser surgery sites. Findings from the present study demonstrate that LPS alone may recruit PMN at sites of epithelial injury and hence may contribute to these syndromes. Since unchecked PMN infiltration is directly responsible for tissue pathology in a number of inflammatory diseases (15), this study further underscores the significance of LPS contamination as a possible contributor to specific ocular diseases. Experiments described herein lay the basis for future research into the basic mechanisms by which host defense factors may contribute to the pathogenesis of such diseases.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by The Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bates A K, Morris R J, Stapleton F. Sterile infiltrates and contact lens wearers. Eye. 1989;3:803–806. doi: 10.1038/eye.1989.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crook T. Corneal infiltrates with red eye related to duration of extended wear. J Am Optom Assoc. 1985;56:698–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunn J P, Mondino B J, Weisman B A, Bruckner J A. Corneal ulcers associated with disposable hydrogel contact lenses. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;108:113–117. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(89)90002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elliott E, Li Z, Bell C, Stiel D, Buret A, Wallace T, Brzuszczak I, O'Loughlin E. Modulation of host response to Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection by anti-CD18 antibody in rabbits. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1554–1561. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90410-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holland S P. Update in cornea and external disease: solving the mystery of “sands of the Sahara” syndrome (diffuse lamellar keratitis) Can J Ophthalmol. 1999;34:93–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Josephson J E, Caffery B E. Infiltrative keratitis in hydrogel lens wearers. ICLC. 1979;6:47–70. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawin-Brussel C A, Refojo M F, Leong F L, Kenyon K R. Effect of Pseudomonas aeruginosa concentration in experimental contact lens-related microbial keratitis. Cornea. 1993;12:10–18. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrison D C, Ryan J L. Endotoxins and disease mechanisms. Annu Rev Med. 1987;38:417–432. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.38.020187.002221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowotny A. In search of the active site in endotoxins. In: Nowotny A, editor. Beneficial effects of endotoxins. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1983. pp. 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schultz C L, Morck D W, McKay S G, Olson M E, Buret A. Lipopolysaccharide induced acute red eye and corneal ulcers. Exp Eye Res. 1997;64:3–9. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silbert J T. Microbial disease and the contact lens patient. ICLC. 1988;15:221–229. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith R J, Maloney R K. Diffuse lamellar keratitis: a new syndrome in lamellar refractive surgery. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1721–1726. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)99044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein R N M, Clinch T E, Cohen E J, Genvert G I, Arentsen J J, Laibson P R. Infected vs. sterile corneal infiltrates in contact lens wearers. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;105:632–663. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tesh V L, Morrison D C. The interaction of Escherichia coli with normal human serum: factors affecting the capacity of serum to mediate lipopolysaccharide release. Microb Pathog. 1988;4:175–187. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(88)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thygeson P. Marginal corneal infiltrates and ulcers. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1947;January/February:198–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zantos S G. Corneal infiltrates, debris and microcysts. J Am Optom Assoc. 1984;55:196–198. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zantos S G. Management of corneal infiltrates in extended-wear contact lens patients. ICLC. 1984;11:604–612. [Google Scholar]