Abstract

Defective genes account for ∼80% of the total of more than 7,000 diseases known to date. Gene therapy brings the promise of a one-time treatment option that will fix the errors in patient genetic coding. Recombinant viruses are highly efficient vehicles for in vivo gene delivery. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors offer unique advantages, such as tissue tropism, specificity in transduction, eliciting of a relatively low immune responses, no incorporation into the host chromosome, and long-lasting delivered gene expression, making them the most popular viral gene delivery system in clinical trials, with three AAV-based gene therapy drugs already approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or European Medicines Agency (EMA). Despite the success of AAV vectors, their usage in particular scenarios is still limited due to remaining challenges, such as poor transduction efficiency in certain tissues, low organ specificity, pre-existing humoral immunity to AAV capsids, and vector dose-dependent toxicity in patients. In the present review, we address the different approaches to improve AAV vectors for gene therapy with a focus on AAV capsid selection and engineering, strategies to overcome anti-AAV immune response, and vector genome design, ending with a glimpse at vector production methods and the current state of recombinant AAV (rAAV) at the clinical level.

Keywords: gene therapy, viral vectors, adeno-associated virus (AAV)

Graphical abstract

Pupo et al. review the different approaches to improve AAV vectors for gene therapy with a focus on AAV capsid selection and engineering, strategies to overcome anti-AAV immune response, and vector genome design, ending with a glimpse at vector production methods and the current state of rAAV at the clinical level.

Introduction

The success of gene therapy relies on an efficacious means to transfer the proper genetic material into the correct tissue. Vectors derived from adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) have become popular delivery systems for therapeutic gene transfer due to their non-pathogenic and broadly tropic nature,1,2,3 their reduced immunogenicity, and the potential to achieve efficient and long-lived gene transfer.4 AAV is a non-enveloped, single-stranded DNA virus, with a genome size of 4.7 kb and a small icosahedral capsid of ∼25 nm, that was discovered in the 1960s as a contaminant in a simian adenovirus preparation.1

The AAV capsid is composed of 60 copies in total of viral protein, VP1–3, in a population ratio of 1:1:10 on average.5,6 However, this is highly dependent on the serotype and the particular preparation.7 AAV capsid assembly is divergent and stochastic, leading to a highly heterogeneous population of capsids of variable composition, whereby even the single-most abundant VP stoichiometry represents only a small percentage of the total AAV population.7

The biology of AAV has been extensively studied.8 A defining characteristic of AAV is its dependence on a helper virus co-infection (such as adenoviruses or herpes-viruses) for productive replication.9

Replication defective AAV viral-like particles (also known as recombinant AAV [rAAV]), in which all viral open reading frames from the viral genome have been eliminated, and containing heterologous genetic information, can be assembled and packaged to high vector yields for gene transfer applications.4

AAV vectors are being explored for numerous therapeutic applications, and they are the most popular viral gene delivery system explored in clinical trials.10,11 The use of AAV vectors in early- and late-stage clinical trials for monogenic diseases such as hemophilia,12 inherited forms of blindness,12 and muscular dystrophy13 has been remarkably successful, regarding their clinical safety and efficacy. Gene transfer therapies using AAV vectors are being fast-tracked for clinical approval for congestive heart failure, hemophilia A and B, retinal disease, X-linked myotubular myopathy, glioma, glioblastoma, and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), among others.14

Despite the fast pace of applications for AAV vectors, their usage in particular treatments is restricted due to remaining challenges, such as pre-existing humoral immunity to AAV capsids, poor transduction efficiency in certain tissues, low organ specificity, and vector dose-dependent toxicity in patients.3,8

In the present review, we address the different approaches to improve AAV vectors for gene therapy with a focus on AAV capsid, strategies to overcome anti-AAV immune response, and vector genome design, and ending with a glimpse at vector production methods and the current state of rAAV at the clinical level.

AAV capsids

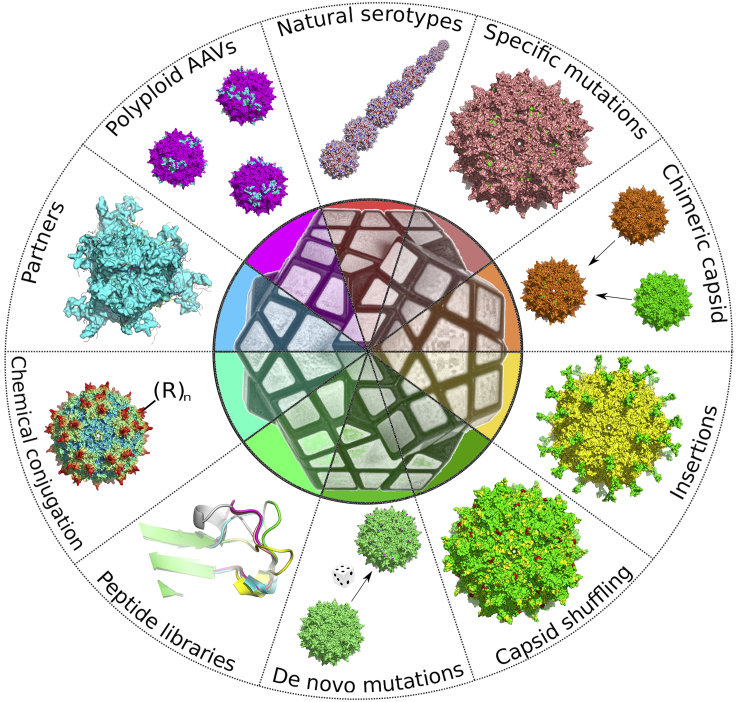

In the last 10 years, with the advances in the field of synthetic biology and our better understanding of AAV structure and biology, several new rAAVs with defined properties have been generated. These new rAAVs have displayed the potential to markedly reduce anti-capsid immune responses and vector dose administration owing to improved gene transfer efficiency and transduction of specific cells and tissues. Figure 1 summarizes the capsid-related approaches that are detailed below.

Figure 1.

Capsid-related approaches to improve AAV-based gene delivery vectors

Natural serotypes

It is frequently said that 13 AAV serotypes have been identified to date (AAV1–13),14,15 but this is just the most studied subgroup from hundreds of serotypes or distinct AAV variants that have been isolated from primates, goats, sea lions, bats, snakes, and other animals4,8,16,17 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Common serotypes/variants for AAV vectors

| Serotype | Origin | Primary receptor | Secondary receptor | Tissue tropism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAV1 | primate | N-linked sialic acid | AAVR GPR108 TM9SF2 |

SMm,c,p,h, CNSm,c,p, lungm,p,h, retinam,r, pancreasm, heartm,i, liverm,p |

| AAV2 | human | heparan sulfate proteoglycan | AAVR GPR108 TM9SF2 LamR αVβ5 integrin α5β1 integrin FGFR1 CD9 HGFR |

SMm,c,h, CNSm,c,p,h, liverm,c,p,h, kidneym, retinam,c,p,h, lungp,h, jointh, ACm |

| AAV3 | human | heparan sulfate proteoglycan | AAVR GPR108 LamR FGFR1 c-MET HGFR |

Liverp,h, SMm, CNSp, cochlear inner hair cellsm |

| AAV4 | NHP | O-linked sialic acid | GPR108 | CNSm,c,p, retinam,c, lungm,p, kidneym, heartm |

| AAV5 | human | N-linked sialic acid | AAVR PDGFR TM9SF2 |

SMm, CNSm,c,p,r, lungm, retinam, liverp,h |

| AAV6 | human | heparan sulfate proteoglycan N-linked sialic acid |

AAVR GPR108 TM9SF2 EGFR |

SMm,c, heartm,s,i,c, lungc,m,p, airwaym,c,p, liverc, CNSp, retinar |

| AAV7 | rhesus macaque | – | GPR108 TM9SF2 |

SMm, retinam, CNSm, liverm |

| AAV8 | rhesus macaque | – | AAVR GPR108 TM9SF2 LamR |

Liverm,c,p,h, SMm,c, CNSm,c,p, retinam,c,p, pancreasm, heartm,c,p, kidneym, ATm |

| AAVrh.8 | rhesus macaque | – | GPR108 | SMh, liverh, CNSm |

| AAV9 | human | terminal N-linked galactose of SIA | AAVR GPR108 TM9SF2 LamR |

Liverm, heartm,i,c,p, SMm,c,p,h, lungm, pancreasm, CNSm,c,p, retinam,p, testesm, kidneym |

| AAV10 | cynomolgus monkeys | – | – | Heartm, lungm, liverm, kidneym, uterusm |

| AAVrh.10 | rhesus macaque | – | GPR108 LamR |

Liverm, heartm, SMm,c, lungm, pancreasm, CNSm,r,c, retinam, kidneym |

| AAV11 | cynomolgus monkeys | – | – | SMm, kidneym, spleenm, lungm, heartm, stomachm |

| AAV12 | NHP | – | – | SMm, salivary glandsm |

| AAVrh32.33 | rhesus macaque | – | GPR108 | – |

Some of these serotypes have been separated into clades A–F on the basis of shared serologic and functional attributes.14 From the common variants for AAV vectors, two serotypes, AAV5 and AAV4, exhibit greater differences in capsid protein sequences. AAV5 is the most phylogenetically distinct, with 58% capsid homology with AAV2 and AAV8 and 57% homology with AAV10.14 In contrast, the other serotypes commonly used in gene transfer share greater homology (∼80%).18 The variable regions in sequence correspond mainly with conformationally distinct loops in the VP structures, which are associated with receptor binding, transduction efficacy, and antigenicity, being relevant in terms of differences in tissue tropism, antigenicity, and the likelihood of cross-reactive immunogenicity between serotypes.34

Tissue tropism reflects the specific interactions between serotype-specific structures on the rAAV capsid and cellular glycans and receptors.14 The initial binding of many AAV serotypes is via primary receptors including glycans and proteoglycans such as heparan sulfate, terminal galactose (Gal), and several linkage variants of sialic acid (SA).14 AAV serotype vectors can be grouped into three categories with respect to their glycan receptor usage: Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycan (HSPG) for AAV2, AAV3, AAV6, and AAV13; sialic acid (SA) for AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, and AAV6; and Gal for AAV9.15 The primary glycan receptors, if any, are unknown for AAV7, AAV8, AAVrh10, AAV11, and AAV1215 (Table 1). We need to point out that this glycan receptor usage grouping is probably a simplification, and that actual profile of glycan recognition is more complex. An example of that is AAV2, as more than 70% of AAV2-like sequences isolated from human samples (having at least a 98% of sequence identity) lack arginine residues at position 585 and 588, being unable to bind HSPG.35 An equivalent diversity could be expected within the other serotypes, regarding their interaction with receptors. We are going to be referring to the AAV laboratory strains, cloned and with the reference genomes, in the rest of this work, unless stated otherwise.

This initial binding is followed by interactions with secondary membrane protein receptors that facilitate internalization.14 A range of secondary receptors has been reported: FGFR1,36 CD9, αVβ5, and α5β1 integrins14,37 for AAV2; hepatocyte growth factor receptor c-MET for AAV238 and AAV339; platelet-derived growth factor receptor for AAV515; EGFR for AAV640; LamR for AAV2, AAV3, AAV8, and AAV9,14 among others14 (Table 1).

AAVR, a glycoprotein with a molecular mass of 150 kDa previously known as KIAA0319L, has been identified as critical for the entry of numerous AAV serotypes, including AAV1, AAV2, AAV3B, AAV5, AAV6, AAV8, and AAV9.41,42 AAV serotypes interact differently with AAVR, while AAV2 interacts predominantly with the second immunoglobulin (Ig)-like polycystic kidney disease repeat domain (PKD2) present in the ectodomain of AAVR, AAV5 interacts primarily through the most membrane-distal PKD1,43 and other AAV serotypes, including AAV1 and AAV8, require a combination of PKD1 and PKD2 for optimal transduction.42 Different non-exclusive functions have been proposed for AAVR in AAV infection: AAVR interacts with AAV either at the surface and aids in AAV cellular uptake into an endosomal pathway, the interaction occurs in the early endosomal system and facilitates trafficking to the trans-Golgi, AAVR interacts with AAV once it reaches the Golgi and facilitates escape from the trans-Golgi network into the cytoplasm, or a combination of the three possibilities.3 Recent data support that AAVR is not a major contributor in cellular attachment and that its role is to facilitate entry at a step prior to nuclear import.19 AAVR usage is conserved among all primate AAVs except for those of the AAV4 lineage (composed of AAV4 and AAVrh32.33) that can bind and transduce cells in the absence of AAVR by an AAVR-alternate route.44

GPR108, a member of the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily, appears to mediate this AAVR-alternate route.19 Transduction was affected in GPR108 knockout for most serotypes (including AAV4 and AAVrh32.33), except for AAV5.19 GPR108 independence can be transferred to other serotypes with the VP1 unique domain of AAV5, and its usage is conserved in mice and humans, being relevant both in vitro and in vivo.19 GPR108 localized primarily to the Golgi, where it may interact with AAV and play a critical role in mediating virus escape or trafficking.20

TM9SF2, a Golgi protein involved in glyco-sphingolipid regulation and endosomal trafficking, also mediates viral transduction in at least seven different AAV serotypes (Table 1).20 TM9SF2 is important for the stabilization and localization of NDST1,45 and it has been shown to be involved in ricin activity, Shiga toxin activity and in vaccinia virus and chikungunya virus infections,46 and AIDS progression.47

The unique combination of specific glycan and protein receptors is believed to be the main factor determining AAV serotype tissue tropisms.8 In mice, AAV serotypes 1–9 show overlapping but distinct tissue expression patterns: liver (AAV 1–3 and 5–9), skeletal muscle (AAV 1–9), heart (AAV4 and 6–9), lung (AAV4 and 6–9), brain (AAV 8–9), and testes (AAV9).48 AAV9, AAVrh.8, and AAVrh.10 are special cases for central nervous system (CNS) delivery, as they are able to bypass the blood-brain barrier and efficiently target cells of the CNS when injected intravenously in different animal models.48,49,50,51,52 Although the diversity of AAVs is huge, several important cell types and tissues are not targeted by natural AAVs.3 Unfortunately, animal models may be poorly predictive of AAV tropism in humans.14,15 Given the difficulties to obtain multiple biopsies in the clinical setting, vector tropism is less characterized in humans, and tissue-specific promoters are frequently incorporated into vectors to limit the expression of the transgene to a particular target tissue.14

AAV vector efficacy depends not only on the ability of the different serotypes to enter the target cells but may also reflect the speed of uncoating and the conversion of the single-stranded vector DNA into duplex DNA that is transcriptionally active.53,54 Several reports summarize and review the transduction efficacy of AAV serotypes in different tissues and specific cells.10,55,56,57,58 A more effective vector could be administered at a lower dose, which could have potential benefits in terms of reduced immunogenicity. The final dose will also depend on other factors, such as the quality of vector manufacturing, transgene activity, and host immunity to the serotype.14

Dealing with post-translation modifications by specific mutations

A total of 52 post-translational modifications (PTMs) were detected in AAV2, AAV3, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV7, AAV8, AAV9, and AAVrh10 capsids produced in AAV-293 cells, including glycosylation (36%), phosphorylation (21%), ubiquitination (17%), SUMOylation (13%), and acetylation (11%).59 To add complexity to this matter, capsid PTMs are heterogeneous60 and differ when produced in human and baculovirus-Sf9 manufacturing platforms.61 Four AAV serotypes (AAV2, AAV5, AAV9, and AAVrh10) had more than seven PTMs in their capsid proteins.61

While no detectable PTM was found in AAV1 by Mary et al.,61 several were found in other studies,61 including N-terminal acetylation; K61, K459, and K528 methylation; and S149 and S153 phosphorylation. The fact that serine and lysine mutant AAV1 vectors (K137R, S663A, and S669A) demonstrate increased transduction both in vitro and in vivo60 is additional evidence of the presence and functional relevance of PTMs in AAV1.

AAV2 capsid proteins have eight sequence motifs that are potential sites for O- or N-linked glycosylation.62 Although no glycosylation was previously found for virus prepared in cultured HeLa cells,63 AAV2 capsid is indeed glycosylated at residues N253, N518, S537, and N551.63 The disruption of N253 N-glycosylation site (mutant N253Q) severely compromised AAV2 packaging efficiency, probably by compromising the vector assembly and stability.61

AAV2 capsids are phosphorylated at tyrosine residues by EGFR-PTK, which leads to their subsequent ubiquitination and impaired intracellular trafficking to the nucleus.61 Point mutations of specific surface-exposed single tyrosine residues (Y444F and Y730F) lead to high-efficiency transduction at lower doses.64,65 A triple-mutant (Y444F + Y500F + Y730F) vector has ∼30- to 80-fold higher level of in vivo gene transfer to murine hepatocytes66 and ∼130-fold increase in transgene expression in murine fibroblasts67 than the wild-type AAV2. These tyrosine residues are highly conserved in most AAV serotypes, with few exceptions.68

Phosphorylation sites, recognized as degradation signals by ubiquitin ligase (phosphodegrons), were predicted from AAV2 capsid sequences and the corresponding serine and threonine residues were mutated by alanine and lysine residues by arginine.66 The transduction efficiencies of 11 S/T/A and 7 K/R vectors were significantly higher than the AAV2-WT vectors.69 The AAV2 K532R mutant showed significantly reduced ubiquitination compared with AAV2-WT.69

Native levels of ubiquitinated capsids in freshly packaged AAV2 are significantly low.69 These capsids showed the presence of ubiquitination at codon K544, phosphorylation at S149, and SUMOylation by SUMO-2/3 at K258.61 The mutant vector K258Q demonstrated reduced levels of SUMO-1/2/3 proteins and negligible transduction.61

AAV2 N-terminal residue is acetylated, a PTM that is conserved in AAV1, AAV2, AAV3, AAV5, AAV7, AAV9, and AAVrh10 vectors.61

In AAV3, phosphorylation and HexNAcylation was observed in residues Y6 and S149, respectively.61,70

Only one PTM was detected in AAV4, a ubiquitination site at K479. This modification was unique and absent in all other serotypes.61 On the other hand, AAV5 has several PTMs, including glycosylation at N292; ubiquitination at K122, K451, and K639; and HexNAcylation at residues N308, T376, and N428.61 AAV5 mutant vectors neutralizing phosphorylation sites at serine (S268A, S652A, and S658A) and threonine (T107A) improve gene transfer efficiency in vitro and in vivo.61

AAV6 had a single acetylation at residue A2.62 AAV7 stands out for the glycosylation PTMs at S157, N254, N460.61

Both AAV9 and AAVrh10 had a relatively higher proportion of sumoylated residues detected in AAV9 (K84, K316, K557) compared with all other serotypes and an overall similar distribution of common PTMs.61

PTMs were distributed along the entire capsid polypeptide of AAV8.61 AAV8 has phosphorylations at Y6, S149, S153, S279, and S671; acetylation of A2 residue; ubiquitination at K137; O-GlcNAc on T494; and N-glycosylation at N499 and N521 residues.60 The point mutant vectors S279A, S671A, and K137R showed higher and preferential transduction of the liver.60,61,71,72 Spontaneous deamidation occurs on the AAV8 vector capsid at 16 positions, predominantly asparagine residues where the N + 1 residue is glycine.71 There is a correlation between vector activity loss over time and progressive deamidation.60,73 This deamidation phenomenon is not serotype specific, with experimental evidence of its presence in AAV1, AAV3B, AAV4, AAV5, AAV7, AAV9, and AAVrh32.33.73

Baculo-AAV8 capsids have more PTMs than those produced in human cells.60 These include methylation and acetylation on K530, methylation on K709, and O-GlyNAc on T663.60

New methodologies, such as an HILIC-FLR-MS protocol74 and VectorMOD,75 have been developed to ease the process of unambiguous serotype identification, stoichiometry assessment, process impurities detection, and PTM characterization.

Chimeric capsid

A common rational design approach for AAV capsid engineering is to build chimeras by the grafting of functional motives from a serotype into another. These motives are usually related with receptor binding regions that dictate tropism. Sometimes the substitution of only one amino acid is enough to achieve a significantly different phenotype. The mutation of K531 in AAV6 by the corresponding amino acid in AAV1 (E) suppresses the heparin-binding ability of AAV6. It also reduces transgene expression to levels similar to those achieved with AAV1 in HepG2 cells in vitro and in mouse. The mutant AAV1 E531K has heparin-binding ability and increased transduction efficiency.76 Intravitreally delivered heparan sulfate binding mutants AAV1-E531K and AAV8-E533K accumulate at the inner limiting membrane separating the vitreous and the retina in the eye, similar to AAV2, while wild types AAV1 and AAV8 do not.76 The single insertion of Thr residue from AAV1 into AAV2 capsid at position 265 enhanced muscle transduction and reduced neutralizing antibody (NAb) titers in mouse.77

In most cases, multiple residues or entire regions are grafted from one serotype into another to achieve the desired phenotype. Both AAV1 and AAV6 are more efficient transducing muscle than AAV2. Replacement of residues 350–736 of AAV2 VP1 with the corresponding amino acids from VP1 of AAV1 resulted in a chimeric vector that behaved very similarly to AAV1 in vitro and in vivo.78 This region can be reduced to amino acids 350–430 to obtain a chimera with similar behavior.79 Following a more comprehensive approach, a panel of synthetic AAV2 vectors was generated by replacing the hexapeptide sequence involved in heparan sulfate binding with corresponding residues from other AAV strains.80 The tropism of the generated capsid was evaluated after intravenous administration in mice. AAV2i8, an AAV2/AAV8 chimera, selectively transduced cardiac and skeletal muscle tissues with high efficiency, traversed the blood vasculature, showed markedly reduced hepatic tropism, and displayed an altered antigenic profile.81 Only four mutations (Q263A, N705A, V708A, and T716N, AAV2 numbering) and one insertion (T265, AAV1 numbering) were required in AAV2 to obtain AAV2.5, which combines the improved muscle transduction capacity of AAV1 with reduced antigenic cross-reactivity against both parental serotypes, while keeping the AAV2 receptor binding.81

Engraftment of AAV9 galactose binding footprint into AAV2 resulted in the chimera AAV2G9, which exploits both Gal and heparan sulfate receptors for infection.82 AAV2G9 remains hepatotropic, like AAV2, but mediates rapid onset and higher transgene expression in mice.82 AAV2G9 displays preferential, robust, and widespread neuronal transduction within the brain and decreased glial tropism.82 Engraftment of the same Gal footprint onto the previously mentioned AAV2i8 chimera yielded an enhanced chimera named AAV2i8G9. This chimera remains liver-detargeted like AAV2i8 and selectively transduces muscle tissues with high efficiency.83

AAV2-AAV8 chimeras, combined with site-directed mutations, were used to map the epitopes related with T cell responses to AAV capsids after intramuscular injection of vectors into mice and non-human primates (NHPs).82 The identified epitope overlaps with the heparan sulfate proteoglycan binding site, which justified the observed correlation between heparin binding, uptake into human dendritic cells, and activation of capsid-specific T cells.84

A series of chimeras termed AAV X-Vivo (AAV-XV) were obtained combining AAV12 VP1/2 sequences with the VP3 sequence of AAV6.85 These AAV variants showed enhanced infection, compared with the wild-type parental viruses, of neuronal cell lines, hematopoietic stem cells, and human primary T cells.85

Although the construction of chimeric AAV capsids is essentially a trial-and-error process, the abundance of structural information on different serotypes and mutants supports a more robust design from the beginning. In order to provide quantitative design principles for guiding site-directed recombination of AAV capsids, capsid structural perturbations predicted by the SCHEMA algorithm was correlated with experimental measurements of disruption in 17 chimeric capsid proteins.86 Protection of viral genomes and cellular transduction were inversely related to calculated disruption of the capsid structure in a chimera population created by recombining AAV2 and AAV4.86 This algorithm and equivalent analysis may be useful for delineating quantitative design principles to guide the creation of new AAV chimeras.

Peptide and protein insertions

Instead of grafting motives from one serotype into another, chimeric AAV capsids can be created by the insertion of peptides and whole proteins in specific VP regions. The main goal of these insertions has been to alter natural AAV serotype tropism. There are two choices that conform the essence of this methodology: what to insert and where.

In one of the first related reports, in order to target CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells, a chimeric AAV2 capsid was constructed where VP2 was replaced by an anti-CD34 scAb-VP2 fusion protein.87 The chimeric had a significantly increased preferential infectivity for the normally refractory CD34+ human myoleukemia cell line KG-1.87

In order to define critical components of virion assembly and infectivity in AAV2, an exhaustive linker insertional mutagenesis was performed in AAV2.88 Some insertional mutants were identified with the capability to assemble the capsid, encapsulate DNA, and infect target cells.88 A 14-amino-acid targeting peptide, including the RGD motif, was inserted into six AAV2 VP loops and the resulting mutants were evaluated by their ability to package the viral genome, A20 antibody recognition, presence of the peptide on the capsid surface, and B16F10 and RN22 target cell binding.89 Mutants with insertion in positions 447 and 587 passed all the filters.89 The mutant with the insertion in 587 efficiently transduced cells despite the presence of neutralizing antisera.89 Peptide insertions in the same loops but different positions, 449 and 588, were successful as well.90 After testing seven positions to insert a 4C-RGD peptide, only insertions following amino acids 584 or 588 were able to expand AAV2 tropism.91 In this last study, no insertion in 447–449 was tried, but in 459 instead, which failed.91 A mutant with this peptide inserted in position 453 also fails to bind its target receptor, but a structural analysis revealed a possible interaction with residues R585 and R588.92 The AAV2 capsid mutant carrying RGD-4C in position 453 and with R585A/R588A substitutions was superior to the one with the insertion in position 587 in target receptor binding and cell transduction efficiency.93 When the muscle targeting peptide MTP is inserted in positions 587 or 588 of AAV2 capsid, both viruses diminished their infectivity on non-muscle cell lines and on un-differentiated myoblast, but preserved or enhanced their infectivity on differentiated myotubes.93 MTP inserted in 587, but not in 588, abolished AAV2 heparin-binding capacity, and infected myotubes in a heparin-independent manner.94 Peptides containing a net negative charge, such as MTP, are prone to confer an HSPG non-binding phenotype when inserted in 587.95

In a comprehensive analysis of AAV2 capsid, 93 mutants at 59 different positions were constructed, including peptide insertions and alanine scanning.96 Insertion of the serpin receptor ligand in N-terminal regions of VP1 (residue 34) or VP2 (residue 138) changed the tropism of AAV2 in vitro.96 With the design of a new system of production in which expression of VP2 protein is isolated and combined with VP1 and VP3 expressed separately, proteins up to 30 kDa were successfully inserted after residue 138, within the VP1-VP2 overlap.97 Different types of proteins have been inserted in the N terminus of VP2 since then. For example, an anti-Her2/neu DARPin was inserted in the N terminus of AAV2 VP2 in order to precisely target tumor tissue and deliver a suicide gene.98 DARPins are high-affinity binding proteins of 14–17 kDa that have been developed as an alternative to antibodies. The DARPin-AAV vector substantially reduced Her2/neu+ tumor growth without causing fatal liver toxicity.98 Anthopleurin-B, a toxin specific for cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5, was inserted in VP2 after residue T138.99 The mutant with the insertion plus R585A/R588A mutations transfers genes to cardiac myocyte without hepatic and other extracardiac infectivity.99

Insertions of peptides and proteins are not exclusive to serotype 2. The tolerance of AAV5 capsid to small deletions and tandem duplication of sequence was globally addressed with the generation and characterization of a library of more than 105 mutants, revealing potential insertion sites.100 An AAV6 mutant with an RGD peptide insertion at position 585, plus Y705-731F + T492V-K531E substitutions, showed a significant increase in both specificity and efficiency in a xenograft animal model in vivo.101 A murine breast cancer tissue-specific peptide was inserted at positions 590 and 589 of AAV8 and AAV9, respectively.102 This peptide was previously selected in an AAV2-based peptide library. The insertion of this peptide augmented tumor gene delivery in both serotypes.102 Nevertheless, the insertion of a peptide derived from the same AAV2 library, with specificity for murine lung tissue, did not alter tropism of either serotype.102 This is evidence of how the context may affect the function of the inserted sequences, particularly short peptide ones, where the required functional conformations could be affected by the anchor and interacting residues in the template AAV.

In a recent approach, the seven amino acids from the GH2/GH3 loop (residues 453–459 in AAV2 VP1) were replaced by three different nanobodies, having 110–130 amino acids, with specificities for CD38, ARTC2.2, and P2X7, respectively.103 Nanobodies are single Ig variable domains from heavy-chain antibodies that naturally occur in camelids. This strategy dramatically enhanced the transduction of specific target cells by recombinant AAV2 and it was also successfully tested in AAV1, AAV8, and AAV9 serotypes.103

Enhanced AAV9 (eAAV9), a modified AAV9 with an insulin-mimetic peptide (S519) inserted into the capsid, has a significantly higher transduction efficiency of insulin receptor (IR) expressing cell lines, differentiated primary human muscle cells, and up to 18-fold enhancement over AAV9 transduction of mouse muscle in vivo.104 A new AAV variant, AAV9-Retro, was developed by inserting the 10-mer peptide into the VR-VIII loop of AAV9 VP3 domain.105 AAV9-Retro can retrogradely infect projection neurons, and can be transported across the nervous system, like AAV9, by intracranial or intravenous injections in mice.105 The insertion of bone-targeting peptide motifs (Asp)14 or (AspSerSer)6 onto the AAV9-VP2 capsid protein results in a significant reduction of transgene expression in non-bone peripheral organs in an osteoporosis model.106

In order to evaluate the capacities of different serotypes to display peptides on their capsid surfaces, 27 peptides were systematically inserted in 13 different AAV capsid variants, followed by production of reporter-encoding vectors.107 Vector performance depended not only on the combination of capsid, peptide, and cell type but also on the position of the inserted peptide and the nature of flanking residues.107 The results are available as an online database, and tools like this should accelerate the in vivo screening of new peptide insertions and the application of the resulting products as unique gene therapy vectors.

Capsid shuffling

DNA shuffling of cap proteins from different serotypes can be achieved by random recombination of homologous genes in vitro.108 These result in large chimeric AAV capsids that can be selected for a given phenotype in a classical directed evolution approach.

An adapted DNA family shuffling technology was used to create a complex library of hybrid capsids from eight different wild-type viruses.109 Selection on primary or transformed human hepatocytes and pooled human antisera led to a single type 2/8/9 chimera, named AAV-DJ, with 60 capsid mutations compared with AAV2.109 Most of these mutated residues are located in the loops extruding from the VP, some critical for natural receptor binding or for antibody recognition or escape. AAV-DJ vectors had more infectivity in vitro than eight standard AAV serotypes (AAV1–6, 8, and 9) and surpassed AAV2 in livers of naive and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) immunized mice.109 AAV-DJ vector has been shown to be a useful tool for gene therapy research targeting retinal disorders, being able to transfer genes to the photoreceptor layer with intravitreal injection and having an efficient gene transfer to various cell types in the retina.110 AAV-DJ8, an AAV-DJ variant modified to specific residues of AAV8, displayed more tropism in astrocytes compared with AAV9 in the substantia nigra region than AAV9 and other vectors.17

Chimeric-1829 is an infectious clone selected from a chimeric capsid library containing randomly fragmented and reassembled capsid genomes from serotypes 1–9.111 As its name indicates, this particular clone contains genome fragments from AAV1, 2, 8, and 9, with AAV2 contributing to surface loops at the 3-fold axis of symmetry, while AAV1 and 9 contribute to 2- and 5-fold symmetry interactions, respectively. Similar to AAV2, Chimeric-1829 utilizes heparan sulfate as a primary receptor, but it shows an altered tropism in skeletal muscle, liver, and brain; transduces melanoma cells more efficiently; and has a unique immunological profile.111

A similarly obtained library was selected against a kainic acid-induced limbic seizure rat model in order to produce a novel AAV vector capable of crossing the seizure-compromised blood-brain barrier and transducing cells in the brain.112 After intravenous administration, two clones transduced the cells in areas exhibiting a seizure-compromised blood-brain barrier that were localized to the piriform cortex and ventral hippocampus.112

Rec1–4 were generated by shuffling the fragments of capsid sequences in three NHP AAV serotypes cy5, rh20, and rh39 and AAV8.113 These vectors were originally selected for retinal tissue transduction, where they are efficient, but no more so than AAV2 and AAV5.113 They have shown potential in other localizations. Rec2 vector showed high transduction efficiency in both brown and white adipose tissue, superior to AAV1, AAV8, and AAV9.114 Compared with AAV9, Rec3 improved gene delivery to mouse spinal cord, transducing a broader region of it, and displaying higher transgene expression and increased maximal transduction rates of astrocytes and neurons.115

Another vector obtained by capsid shuffling and directed evolution, named Olig001, contains a chimeric mixture of AAV1, 2, 6, 8, and 9.116 Olig001 shows a preferential oligodendrocyte tropism following intracranial injection into the striatum, as opposed to the vast majority of AAV vectors, which have shown a dominant neural tropism in the CNS. This vector has very low affinity for peripheral organs, especially the liver, after intravenous administration.116

AAV LP2-10, composed of capsids from AAV serotypes 2, 6, 8, and 9, with VP3 subunits derived from AAV8 swapped with AAV6 from residues 261 to 272, manifested a higher ability to escape NAbs in IVIG and human serum samples.117 LP2-10 transduced human hepatocytes with efficiency similar to that of AAV8.117

AAV2.5T, a capsid with lung tropism, was evolved from an AAV2/AAV5 capsid-shuffled library.118 VP2 and VP3 capsid proteins of AAV2.5T are derived from AAV5 with a single A581T mutation in VP1. VP1 of AAV2.5T is a hybrid of AAV2 and AAV5 capsids with the N-terminal unique sequence (VP1u) from the 1–128 amino acids of the AAV2 VP1, followed by the 129–725 amino acids of AAV5 capsid harboring the A581T mutation.118

De novo mutations

An alternate way to create an AAV capsid library from which to select a desired phenotype is by the generation of random mutations in capsid DNA. This has been accomplished by modified PCR protocols, including staggered extension process and error-prone PCR.119 The size of AAV libraries obtained by this approach is in the range of 106–107 mutants and they have been based in AAV2 with the main goal to escape NAbs while keeping the other functional properties of AAV2 untouched120 or modifying heparan sulfate affinity.95,121,122

To improve the liver transduction of AAV5 while retaining its low seroprevalence, a library of AAV5 mutants was constructed via random mutagenesis and screened in Huh7 cells.123 Two new AAV5 variants, MV50 and MV53, demonstrated significantly increased transduction efficiency in Huh7 cells (∼12×) and primary human hepatocytes (∼10×).123

AAV-S was isolated from a random capsid library, and it mediates highly efficient reporter gene expression in a variety of cochlear cells, including inner and outer hair cells, fibrocytes, and supporting cells in both mice and cynomolgus macaques.124

An alternative approach to random mutations is the comprehensive mutagenesis approach, where all single-codon substitution, insertion, and deletion mutants for AAV2 capsid were generated and evaluated in vitro and in vivo.125 The phenotypic characterization of this library, regarding capsid ensemble and thermal stability, tissue tropism, and delivery, allows the implementation of a machine learning (ML) guided design of new AAV capsids that outperform the one resulting from random mutagenesis.125

The combination of DNA/RNA barcoding with multiplexed next-generation sequencing enables the direct side-by-side comparison of pre-selected AAV capsids in high throughput and in the same animal.126 As a validation of the methodology, three independent libraries were created, from which a peptide-displaying AAV9 mutant called AAVMYO was discovered.126 AAVMYO exhibits superior efficiency and specificity in the musculature, including skeletal muscle, heart, and diaphragm, following peripheral delivery.126

ML models trained directly on experimental data without biophysical modeling provide one route to accessing the full potential diversity of engineered proteins. The application of deep learning allowed designing highly diverse adeno-associated virus 2 (AAV2) capsid protein variants that remain viable for packaging of a DNA payload.127

The vast structural information on AAV capsids allows the rational design of new variants. The structures of several AAV8/antibody complexes were solved by cryoelectron microscopy, and then each VP surface loop involved in the interactions was evolved by infectious cycling in the presence of a helper adenovirus.128 This process yielded a humanized AAV8 capsid (AAVhum.8) displaying non-natural surface loops that simultaneously display tropism for human hepatocytes, increased gene transfer efficiency, and NAb evasion.128

Using alanine scanning mutagenesis, S155 and the flanking residues, D154 and G158, were found to be essential for AAV2 transduction efficiency.129 Specific capsid mutants show a 5- to 9-fold decrease in viral mRNA transcripts, highlighting a potential role of this N-terminal S/T motif in transcription of the viral genome.129

Peptide libraries

The most frequent approach in direct evolution of AAV capsids consists of the insertion of random peptides (usually seven amino acids long) in a VP loop (AAV2’s VP1 587, 588, and their equivalent in other serotypes are preferred) to generate a random capsid library. This library is then used to perform selection for a desired phenotype, usually related to a given tropism or to escape NAbs. In this approach, peptides are selected in the right capsid context and, in principle, should be superior to the insertion of peptides previously selected elsewhere. In one of the first implementations of this methodology, a random AAV2 peptide library was screened on human coronary artery endothelial cells, peptide motives were selected, and their insertion enhanced transduction in coronary endothelial cells but not in control non-endothelial cells.130 New capsids targeting primary human CD34+ peripheral blood progenitor cells were selected with the methodology.131 The chimera AAV-DJ has been used to develop new capsid peptide display random libraries from which new capsids targeting mice lung alveolar cells have been selected.109 In another successful example, selected AAV2-peptide capsids target autologous human keratinocytes, transducing these cells with high efficiency and selectivity.132

Despite early successful examples and the undeniable potential of this methodology, from early on its limitations became apparent, some specific and others that extend to all directed evolution approaches (including the previously discussed capsid shuffling and de novo mutations libraries). Among the limitations are the following:

-

•

Libraries contaminated with WT.

-

•

In vitro selection results do not always translate to in vivo applications.

-

•

Collateral tropism of selected variants.

-

•

Cross-packaging and mosaicism.

-

•

The enhanced features of the selected capsids may not extend beyond the context in which the selective pressure was applied.

An improved library production system using a synthetic cap gene reliably avoids generation of wild-type AAV2.133 With this procedure, the efficiency and specificity of gene transfer to target cells was improved.133

Vectors selected for optimized transduction of primary tumor cells in vitro were not suitable for transduction of the same target cells under in vivo conditions.134 After several rounds of selections performed using tumor and lung tissue as prototype targets in living animals injected intravenously, selected clones conferred gene expression in the target tissue, while gene expression was undetectable in animals injected with control vectors.134 Nevertheless, the selected vectors also transduced a number of other tissues, particularly the heart.134 MicroRNA-regulated transgene cassettes as the combination of library-derived capsid targeting and microRNA control was proposed as an alternative to address this collateral tropism issue.135 In vivo screening of random peptide libraries by next-generation sequencing can achieve improvement in target tissue specificity.136 Using this methodology, a capsid variant was selected that specifically and very efficiently delivers genes to the endothelium of the pulmonary vasculature after intravenous administration.136

The correlation between the selected capsids and the encapsidated viral genomes is crucial to be able to obtain the correct information about the selected variants.137 AAV libraries have the potential to be affected by cross-packaging and mosaicism, in which particles are composed of genomes and capsid monomers derived from different library members.138 AAV2 libraries produced by a two-step protocol with pseudotyped library transfer shuttles, which should ensure genome-capsid correlation, display a bias in the amino acid composition. This bias confers increased heparin affinity and, thus, similarity to wild-type AAV2 tropism, which may impair the intended use of these libraries.137 A step-by-step protocol on how to obtain and screen random AAV display peptide libraries in vivo, taking into account most of these topics, is available.139 Dilution of input library DNA significantly increases capsid monomer homogeneity and increases capsid-genome correlation, reducing cross-packaging and capsid mosaic formation.138

Cre-recombination-based AAV targeted evolution (CREATE) methodology140 is one of the most interesting cases of AAV random displayed libraries, showing both their great potential and highlighting their probable main limitation. This methodology first provided the AAV-PHP.B variant, which efficiently and widely transduces the adult mouse CNS after intravenous injection.140 Two modified versions were obtained later, AAV-PHP.eB and AAV-PHP.S, that efficiently transduce the central and peripheral nervous systems, respectively.141 In adult mice, intravenous administration of a lower dose of AAV-PHP.eB transduced 69% of cortical and 55% of striatal neurons, while administration of AAV-PHP.S transduced 82% of dorsal root ganglion neurons as well as cardiac and enteric neurons.141 Being able to bypass the blood-brain barrier and efficiently target cells of the CNS after systemic injection, AAV-PHP.B and its derivatives were strong candidates for gene delivery therapies in humans. Then, it was reported that the neurotropic properties of AAV-PHP.B were not extended to NHPs or the other commonly used mouse strain, BALB/cJ.142 The same happened with AAV-PHP.B variants, such as AAV-PHP.eB, AAV-PHP.B2, and AAV-PHP.B3.143 To make matters worse, AAV-PHP.B caused an acute toxicity event, with consumption thrombocytopenia and secondary hemorrhages, leading to the euthanasia of an NHP 5 days after injection.142 Intravenous administration of PHP.B capsid also failed to upregulate transduction efficiency in the marmoset brain.144 Nevertheless, AAV-PHP.B does work in other strains of mice (C57BL/6N, SJL/J, FVB/N, and DBA/2)145 and PHP.eB works in rats.146

One of the advantages of direct evolution approaches is that there is no need to know the molecular determinants of the successful phenotypes, including the receptors and corresponding binding sites giving a new tropism, or the epitopes recognized for the avoided antibodies. The problem is that such receptors or epitopes do not necessarily have to be conserved among different species, or even strains of a given species. It was recently described that a GPI-linked protein, LY6A, is the cellular receptor for AAV-PHP.B capsids, driving their transport across the blood-brain barrier.143,147 AAV-PHP.B capsids binding and posterior transduction mediated by this receptor can occur independently of other known AAV receptors.143 The absence of LY6A in some mouse strains and primates explained the failure to reproduce the reported neurotropic effects previously observed in C57BL/6J mice.143 AAV-PHP.B and AAV-PHP.eB are now valuable and widely used vectors for mouse neuroscience studies, but they cannot be used in their current form as vectors to be delivered systemically to target CNS in human gene therapy.

These results suggest that the libraries should be selected in their intended final target. As we have seen that there is not a good translation between libraries selected in vitro with the in vivo results, the challenge to select good vectors from AAV libraries for gene delivery in humans is high.

Alternative approaches have been developed. A new RNA-driven screen platform, termed Tropism Redirection of AAV by Cell-type-specific Expression of RNA (TRACER) was developed as a directed evolution approach based on recovery of capsid library RNA transcribed from CNS-restricted promoters.148 The platform was tested in mice with AAV9 peptide display libraries, and 10 individual variants were characterized and showed up to 400-fold higher brain transduction over AAV9 following systemic administration in mice.148 It remains to be seen whether this or equivalent methodologies will allow the selection of better vectors for human use.

Chemical conjugation and unnatural rAAV vectors

Chemical conjugation is an alternative approach to disrupt receptor binding motifs, or introduce new ones, and to mask epitopes and escape NAbs. PEGylation moderately protects AAV2 against NAbs with ∼2-fold less neutralization over unmodified vector.149 The PEGylated AAV2 conserves the infectivity up to a given PEG:lysine conjugation ratio, which depends on the polymer chain size.149 PEGylation of AAV vectors with succinimidyl succinate (SSPEG) and tresyl chloride (TMPEG) has been reported as a more effective approach, protecting the vector from NAbs without compromising transduction efficiency to the liver and muscle, and improving gene expression in the lung.149

Masking of arginine residues on AAV capsids can be achieved by an exogenous glycation reaction, in which surface-exposed guanidinium side chains are modified into charge neutral hydroimidazolones.150 This reaction disrupted the cluster of basic amino acid residues implicated in heparan sulfate binding in AAV2.150 Glycated AAV2 is then unable to bind heparan sulfate but retained the ability to infect neurons in the mouse brain and was redirected from liver to skeletal and cardiac muscle following systemic administration in mice, while also showing a 2-fold decrease in binding to the A20 monoclonal antibody.150

Due to the abundance of lysine and arginine residues in AAV capsids, the previous reactions intrinsically lack site specificity, making it difficult to avoid the unwanted modification of functionally critical residues. Two approaches have emerged to address the site-specific chemical modification of AAV capsids. The first strategy involves the genetic insertion of a peptide with a consensus sequence into the cap gene. The insertion of a 15-amino-acid biotin acceptor peptide allows the site-specific ligation of a ketone analog of biotin with the enzyme biotin ligase.151 This ketone group can be specifically conjugated to a hydrazide- or hydroxylamine-functionalized molecules, such as fluorophores, and a synthetic cyclic RGD peptide, targeting the virus to the αvβ3 integrin receptors.151 Another 13-amino-acid peptide, with a consensus sequence that is recognized by a cellular formylglycine-generating enzyme, was inserted into the cap gene at amino acid position 587.152 This enzyme converts the cysteine residue of the peptide to aldehyde-bearing formylglycine (FGly) residue. This aldehyde group allows the attachment of functionalized elements, such as peptides, antibodies, and fluorophores, without significant loss of viral function and infectivity.152 The conjugation of an anti-human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mouse monoclonal antibody increased transduction in 293T and HepG2 cells, while the conjugation of an anti-CD20 MAb enhanced transduction in CD20-expressing 293T (293T.CD20).152 Conjugation of a chemically modified cyclic RGD peptide displayed enhanced transduction in HeLa cells.152

The second strategy involves the incorporation of unnatural amino acids (UAAs) into specific sites on the virus capsid.153 This technology makes use of an engineered tRNA/aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase pair to deliver the UAA of interest in response to a repurposed nonsense codon, and over 150 UAAs have been genetically encoded.154,155 The unnatural amino acid AzK was chosen (by its azido functionality, which enables a highly specific bioconjugation reaction) to be introduced in distinct surface-exposed sites of AAV2.153 AzK residue was well tolerated in multiple regions of the capsid, which significantly expands the selection of sites that can be evaluated for attaching new elements.153 When a cyclic RGD peptide was attached to AzK in T454 and R588 sites, the R588AzK virus, which is non-infective due to the lack of R588 residue, regained significant infectivity toward SK-OV-3 cells, but not HEK293T cells.153

With the goal to protect AAV2 from pre-existing NAbs and increase its serum stability, a site-specific PEGylation was achieved using a lysine mimic called Nε-2-azideoethyloxycarbonyl-L-lysine (NAEK), an azide moiety.156 AAVs conjugated with 20-kDa PEG at sites Q325 + 1, S452 + 1, and R585 + 1 showed improved stability in pooled human serum, a nearly 2-fold reduction in antibody recognition, and a 20% reduction in antibody inducement in Sprague-Dawley rats.156

Building on the UAAs insertion approach, oligonucleotides were coupled to AAV2 and AAV-DJ capsids.157 Oligonucleotide-pseudotyped AAVs were then incubated with lipofectamine, which interacts with the negative charges of the oligonucleotides and forms a complex with them, creating a cloak around the capsids. The cloaked AAVs are resistant to serum-based NAbs and retained full functionality, keeping their ability to transduce a range of cell types and also enabling a robust delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 effectors.157 Tethering of oligonucleotides will enable the coating of AAV capsids with proteins, nucleotides, and small molecules through the use of specific DNA aptamers.157

These results demonstrate the feasibility of chemical alteration of rAAV vector tropism and/or antigenicity, becoming a practical orthogonal strategy to engineer AAV vectors for gene therapy applications.

Partners

AAV capsids can be associated non-covalently with partner biomolecules in order to alter their tropism or protect them from NAbs. The first successful example involved a bispecific F(ab’)2 antibody with one arm that recognizes cell-surface αIIβ3 (receptor expressed on human megakaryocytes), and the other, the AAV2 capsid.158 Targeted AAV vectors were able to selectively transduce megakaryocyte cell lines, which are not permissible to AAV2, while the endogenous tropism of AAV2 was significantly reduced.158 The binding of the bispecific antibody did not affect other steps required to successfully transduce target cells, such as escape from endosomes, migration to nucleus, or uncoating.158 Despite the potential of this particular approach, the use of bispecific antibodies to alter AAVs tropism has been practically abandoned since then.

Peptide affinity reagents have been used as alternative partners to antibodies in AAV capsid targeting. Pre-incubation of AAV2 vector with vascular endothelial cell membrane-specific peptides markedly increased AAV2 transduction of human umbilical vein vascular endothelial cells, without affecting AAV2 expression in other cell types.159 Through panning of a commercially available phage display peptide library, a heptapeptide specific for AAV8 serotype was obtained.160 This peptide blocked AAV8 vector gene transduction in vitro and in vivo and could be used as a reagent for affinity column chromatography of recombinant AAV8 vectors.160 This peptide could potentially be used as an anchor to conjugate other molecules to modify the properties of the AAV8 capsid.

Tat-Y1068, a small, cell permeable peptide consisting of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor peptide and the HIV-Tat sequence, was designed to improve the transduction efficiency of AAV2.161 Pre- or co-treatment of CYNOM-K1 cells (from cynomolgus monkey embryo skin) and rat fibroblast cell line RAT-1 with Tat-Y1068 increased the transduction efficiencies of AAV2 in a dose-dependent manner.161

Cell-penetrating peptides can significantly enhance the in vitro transduction efficiency of AAV9, the best of which was the LAH4 peptide.162 The enhancement of AAV9 transduction by LAH4 relied on binding of the AAV9 capsid to the peptide. LAH4 peptide increased the AAV9 transduction in the CNS in vitro and in vivo after systemic administration.162

Several potential blood-brain barrier shuttle peptides, that significantly enhance AAV8 transduction in the brain after a systemic administration, have been identified.163 The best results were obtained with a peptide named THR. The enhancement of AAV8 brain transduction by THR is dose dependent, with neurons as primary targets. THR directly binds to the AAV8 virion, increasing its ability to cross the endothelial cell barrier, without interfering with AAV8 infection biology.163

During production, a fraction of AAV vectors are associated with microvesicles/exosomes, termed vexosomes (vector exosomes) or, alternatively, exosome-associated AAV (exo-AAV).164 In exo-AAV, capsids are associated with the surface and in the interior of microvesicles.164 Purified exo-AAV outperformed conventionally purified AAV vectors in transduction efficiency and were more resistant to a neutralizing anti-AAV antibody.164 Exo-AAV bound to magnetic beads can be attracted to a magnetized area in cultured cells,164 which could be of use for their specific targeting.

Exo-AAV9 was up to 136-fold more resistant over a range of NAb concentrations relative to standard AAV2 vector in vitro.165 While passively transferred human antibodies decreased intravenously administered AAV9 transduction of brain by 80% in mice, transduction of exo-AAV9 was 4,000-fold higher.165 Simple pelleting of exo-AAV9 from media via ultracentrifugation results in high-titer vector preparations, capable of a more efficient transduction of CNS cells than AAV9 after systemic injection in mice.166

A significant enhancement of transduction efficiency in liver was observed in a hemophilia B mouse model treated with exo-AAV8 expressing human coagulation factor IX, compared with AAV8.167 Exo-AAV8 gene delivery allowed for efficient liver transduction even in the presence of moderate NAb titers.167

Gene delivery to sensory hair cells of the inner ear is inefficient with available vectors.168 Exo-AAV1 is more efficient than conventional AAV1, both in mouse cochlear explants in vitro and with direct cochlear injection in vivo.168 Exo-AAV1 gene therapy partially rescues hearing in a mouse model of hereditary deafness and shows no toxicity in vivo.168

Exo-AAV2 vector mediates robust gene delivery into the murine retina upon intravitreal injection, efficiently reaching the inner nuclear and outer plexiform, and, to a lesser extent, the outer nuclear layer.169 The simplicity of its production and isolation should make it widely applicable to basic research of the eye.169

An intratumoral administration of AAV6 vexosomes carrying a suicide gene in a murine xenograft model revealed a 2.3-fold increase in hepatocellular carcinoma regression compared with untreated animals.170

Given the positive results obtained so far with exo-AAVs and its applicability to any existing AAV vector, clinical applications based on exo-AAVs are expected. Before that, an exhaustive characterization of other biomolecules contained in such exosomes, besides the capsids, will be required. Other issues, such as the homogeneity and reproducibility of the exo-AAVs, will have to be addressed.

In an innovative approach, a hybrid viral vector composed of a bacteriophage T4 and more than one “piggy-backed” AAV was recently developed.171 The AAV capsid acts as a driver by virtue of its natural ability to enter human cells. The delivery payload capacity of the whole hybrid vector is up to 170 kb.171 T4-AAV particles packaged with influenza virus hemagglutinin DNA, and displayed with plague F1mutV antigen, elicited durable immune responses against both flu and plague pathogens, providing complete protection to mice against pneumonic plague.171 This hybrid vector holds a great potential for applications when delivery of large genes is required.

As larger insertions often have unpredictable deleterious impacts on capsid formation and gene delivery, Velcro-AAV, a coiled-coil-based platform for non-covalent attachment of proteins/peptides to the surface of the AAV capsid, was developed.172 AAV capsids were decorated with leucine-zipper coiled-coil binding motifs that exhibit specific non-covalent heterodimerization.172 This protein display platform may facilitate the incorporation of biological moieties on the AAV surface, expanding possibilities for vector enhancement and engineering.

Polyploid AAV capsid

Polyploid or transcapsidation approach consisted of the transfection of combinations of AAV serotype helper plasmids to produce mosaic capsid recombinant AAV.173,174 To combine the advantages of AAV1 and AAV2 vectors, a mixture of the corresponding helper plasmids was used in the transfection process, resulting in packaged virions with capsid proteins from both serotypes.173 The resulting chimeric vectors could be purified by heparin column, and they showed expression levels similar to those of AAV1 in muscle or AAV2 in liver, in vivo.173 Surprisingly, the polyploids vectors did not escape NAbs, being inhibited by both AAV1 or AAV2 antiserum.173

To systematically evaluate how these mosaic capsid recombinant AAV can be formed, and their functionality, AAV1–5 helper plasmids were mixed at five ratios.174 This revealed the existence of functional subgroups among the serotypes, which correspond to pairwise VP sequence identities: subgroup A (AAV1–3), B (AAV4), and C (AAV5). The rAAV titer depends on the serotype’s subgroup: it is high with mixtures within subgroup A, intermediate from serotype 5 mixtures, while mixtures containing the AAV4 capsid exhibited reduced packaging capacity.174 This suggests a reduced compatibility of subunit interaction between serotypes of different subgroups. The binding profiles of the mixed-virus preparations to heparin sulfate or mucin agarose revealed either an abrupt shift or a gradual alteration in the binding profile to the respective ligand upon increase of a capsid component that conferred ligand specificity, only AAV3–AAV5 mixtures at the 3:1 ratio exhibited duality in binding. The transduction profiles either do not change with the ratio of the mixtures, increase gradually with titration of a second capsid component, or increase abruptly given a threshold. A synergistic effect in transduction and an unexpected new tropism were observed in some combinations of AAV1 helper constructs with type 2 or type 3 recipient helpers.174

Transduction efficiencies in the rat hypothalamus of polyploid AAV1/2 and AAV2/8 vectors carrying short hairpin RNAs were compared versus AAV1, AAV2, and AAV8.175 AAV1 vector was more efficient than the polyploids and the other serotypes in neuronal transduction of the rat lateral hypothalamic nucleus.175

Polyploid viruses might potentially acquire advantages from parental serotypes for enhancement of AAV transduction and evasion of NAb recognition without increasing capsid antigen presentation in target cells.176 rAAV resulting from the co-transfection of AAV2 and AAV8 helper plasmids at different ratios were evaluated for both their transduction efficiency and NAb escape activity.176 All the polyploid viruses induced higher transduction than their parental AAV vectors after muscular injection. After systemic administration, a 4-fold higher transduction in the liver was observed with AAV2/8 1:3 than that with AAV8.176 This same AAV2/8 1:3 virus was able to escape AAV2 neutralization and did not increase capsid antigen presentation capacity. NAb evasion ability was improved with the triploid AAV2/8/9 (ratio 1:1:1), which was able to escape NAb activity from mouse sera immunized with parental serotypes.176

Chai et al.177 explored the transduction efficiency of several haploid viruses, which were made from the VP1/VP2 of one serotype and VP3 of another compatible serotype. The haploid AAV vectors, composed of VP1/VP2 from serotypes 8 or 9, and VP3 from AAV2, displayed an increased liver transduction compared with those of AAV2 vectors, while those with VP1/VP2 from serotypes 8 or 9 and VP3 from AAV3 achieved higher transductions in multiple tissue types compared with those of AAV3 vectors.

Polyploid AAV vectors can potentially be generated from any compatible AAV, whether a natural serotype, rational designed, library derived, or any combination thereof, providing a novel strategy that should be explored in future clinical trials.

Strategies to overcome anti-AAV immune response

One reason AAV is the vector of choice for gene therapy is its relatively low immunogenicity. Paradoxically, finding efficient strategies to circumvent pre-existing anti-AAV immunity and to prevent de novo humoral and cellular responses to the vector is a necessity for the advancement of the field of gene therapy.

The ability of pre-existing NAbs to reduce or abrogate AAV-mediated therapy has been well documented.178,179,180 AAV2 has the highest seroprevalence of NAbs in the general population,181 which makes this serotype less suitable for systemic administration. The serotypes with the lowest reported seroprevalence of NAbs in humans are AAV8 and the phylogenetically distinct AAV5.178,181 Unlike other serotypes, AAV5 has proved to be more resistant to NAbs, as it is able to successfully transduce liver in humans with relatively high titers of NAbs.182,183 Based on these results, participants with titers of NAbs were included in trials in hemophilia A and B using AAV5 vector.14 NAb prevalence is moderate at birth, decreases markedly from 7 to 11 months, and then progressively increases through childhood and adolescence.184 The seroprevalence of NAbs to AAV vector serotypes also varies by geographic region.178 Although all four IgG subclasses have been detected in seropositive individuals or patients receiving AAV-mediated gene therapy, IgG1 constitutes the predominant subclass.59,185,186 Additionally, non-neutralizing AAV-specific antibodies have been observed that can potentially increase transduction in certain tissues.187 Complement activation by AAV-specific antibodies is currently being investigated as a possible source of tissue toxicity.188

Based on rates of pre-existing immunity, it makes sense to choose a vector serotype with the lowest prevalence in the general population, such as AAV5 or AAV8.14 However, anti-AAV antibody cross-reactivity caused by the high degree of conservation in the amino acid sequence among AAVs is another element to consider,181 as well as differences in immunogenicity between AAV serotypes.189 Due to this complex scenario, an important effort is being made in the design of novel AAV capsids or capsid modification strategies directed to avoid Nabs, as discussed elsewhere in this review.

Other strategies have focused on eliminating circulating NAbs or antibody-producing B cells. In this sense, plasmapheresis has been used to eliminate AAV-specific NAbs from patients’ sera with a degree of success in the context of low NAb titers.190 B cell depletion before AAV administration caused a reduction of AAV-specific humoral response in preclinical studies,191 and combination of rituximab with rapamycin is under study in a clinical setting (clinical trial NCT02240407). A promising approach based on IgG cleavage with the streptococcal endopeptidase IdeS (Imlifidase) was described last year by Leborgne et al.192 The authors demonstrated that IdeS degraded anti-AAV8 NAbs both in vitro and in vivo in a setting of passive transference of human IVIG followed by AAV8 administration in mice.192 Furthermore, elimination of anti-AAVs NAbs by IdeS allowed efficient AAV8-mediated liver transduction in mice infused with IVIG. These results were extended to NHPs naturally carrying anti-AAV8 NAbs, where IdeS treatment significantly increased transduction with AAV8-hFIX vector in the presence of NAbs and during a re-dosing schedule using AAV-LK03.192 Similar results were obtained by Elmore et al. using IdeZ endopeptidase, an IdeS analog from Streptococcus zooepidemicus.193 IdeZ rescued AAV8- and AAV9-mediated liver transduction in mice passively immunized with human IVIG and individual human sera, as well as in seropositive NHPs injected with AAV9.193

Despite the growing research effort, AAV re-dosing continues to be an unanswered need. Strategies such as IgG cleavage with IdeS or IdeZ can transiently eliminate anti-AAV NAbs before vector injections, which could be a solution to the major issue of pre-existing NAbs. However, the generation of capsid-specific CD8+ T cells with the ability to eliminate transduced target cells has also been described.194,195,196,197 Capsid immunodominant peptides are presented in major histocompatibility complex (MHC) classes I and II by antigen-presenting cells (APCs),198,199,200,201 which constitute the first signal for the activation of AAV-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, respectively. Co-stimulation and cytokine signals provided by APCs after sensing of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) on AAV capsid and viral genome are also required for priming naive AAV-specific T cells.200,201,202 Evidence indicates that capsid proteins are sensed by Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) in the surface of APCs,202 whereas unmethylated CpG motifs, present in the viral genome, are recognized by endosomal TLR9.200,203 Interestingly, Rogers et al. demonstrated that activation of TLR9-MyD88 pathway in plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) is essential for the cross-priming of capsid-specific CD8+ T cells, in a complex process that also requires a crosstalk with conventional DC (cDC) and type I interferon (IFN I).200 Early evidence also suggests that MDA5 sensor could have a role in AAV innate sensing through recognition of dsRNA molecules generated during vector transduction, which contributes to IFN I production.204

Based on the important role of TLR9 signaling for anti-AVV T cell responses, depletion of stimulatory CpG motifs or incorporation of TLR9 inhibitory oligonucleotides in the transgene sequence have been studied as potential solutions to avoid T cell activation in the context of gene therapy.205,206,207 Faust et al. showed that CpG-depleted AAVrh32.33 vectors allowed a stable transgene expression in mouse muscle tissue, which was associated with a significant reduction of the frequency and activation of CD8+ T cells specific for the capsid and the transgene.205 More recently, Chang et al. demonstrated that engineered AAV2, AAV8, and AAVrh32.33 vectors containing short DNA oligonucleotides that antagonize TLR9 activation elicited impaired T cell responses and enhanced transgene expression in different animal models.207 Nonetheless, Xiang et al.206 showed that CpG depletion does not always lead to reduced T cell responses and pointed out the importance of properly interpreting the results obtained in available animal models. In fact, most of the work commented on here evaluated the effect of CpG depletion on naive T cells directed against the capsid or the transgene, where the consensus is a reduction of their expansion and functionality. Conversely, Xiang et al. observed an enhanced in vivo proliferation of capsid-specific memory CD8+ T cells in response to CpG-depleted AAV vectors compared with vectors containing CpG motifs.206 Therefore, a deeper understanding of the potential outcome of CpG depletion in AAV vectors is needed for proper clinical application. Some evidence in this regard starts to accumulate in the clinical setting. In a phase I/II clinical trial, transient transgene expression was observed in hemophilia B patients treated with AAV8-based FIX Padua (BAX 335) gene therapy, which was associated with an increased content of CpG motifs introduced into the transgene coding sequence by codon optimization.208 This link between CpG content, immune system activation, and transgene elimination was corroborated in other gene therapy clinical trials for hemophilia B.209 Therefore, finding the right balance between the potential increase of transgene expression and the number of immunostimulatory CpG motifs can be critical when codon optimization strategies are applied to AAV gene therapy vectors for clinical use.

Experience from clinical trials has shown immune-related toxicity in patients receiving AAV-based gene therapy, particularly at high vector doses.12,194,198,210 The most common course of treatment has been corticosteroid administration,12,196,210 which has not always been successful to control anti-AAV immune responses and has known side effects.211,212 This highlights the importance of using more selective and efficient drugs to target AAV-specific T cell responses, which could potentially be used in patients in combination with strategies focused on avoiding NAbs, such as IdeS enzyme treatment, to enable re-dosing efforts. Particularly desirable are the strategies promoting specific immune tolerance mechanisms, such as expansion of regulatory T cells (Tregs). In this sense, ImmTOR nanoparticles, containing the ImmTOR inhibitor rapamycin, can promote a tolerogenic response characterized by the induction of tolerogenic DCs and antigen-specific Tregs when co-administered with antigens in animal models.213,214,215 Meliani et al. demonstrated that ImmTOR co-administered in mice with AAV vectors reduced both NAb titers and T cell responses against capsid proteins, including memory CD4+ T cell reactivation, with concomitant Treg expansion.216 Therefore, re-dosing was possible in both mice and NHP within the experimental conditions tested.216 More recently, Ilyinskii et al. showed that co-administration of ImmTOR with AAV vectors enhanced transgene expression in the liver through a mechanism unrelated to the immunoregulatory effects of ImmTOR and independent of the AAV receptor.217 The efficacy of co-administration of ImmTOR with AAV vectors to control anti-AAV immune responses in patients, as well as potential side effects, will be crucial points for future use in the clinical setting.

Vector genome design

Promoters “in the small work” of rAAV

Along with the selection of new capsids, design of the transgene sequence has also evolved during the past years. Given the limited cargo capacity of AAV and the broad tropism of most of the capsids, many efforts have been made for the identification of short and strong promoters.218 Although ubiquitous promoters are currently in use in the clinic and can still be used depending on the indication, e.g., when multiple cell types or tissues need to be treated, current efforts are more focused on the selection of tissue-specific promoter sequences. When selecting such sequences, promoter strength must also be considered in parallel to tissue specificity, since use of a strong promoter would allow increased vector potency and, thus, reduced doses. One strategy simply consists of identifying the minimal/core promoter sequence through testing different shortened sequences of natural gene promoters, as illustrated, for example, by the photoreceptor-specific rhodopsin kinase core promoter.219 Another strategy is to rationally assemble hybrid promoters using elements from different known enhancers and promoters, leading to the generation of short and strong promoters, either ubiquitous or tissue specific, suitable for delivery of large coding sequences such as s.p. Cas9 or coagulation factor VIII.218,220,221

This strategy can be further refined using computational approaches, by which transcription factor binding sites and other cis-acting sequences involved in tissue specificity and promoter strength can be identified from microarrays and genome-wide functional analyses.222 By assembling different combinations of such cis-regulatory motifs, it has been possible to select short tissue-specific enhancers able to greatly increase tissue-specific gene expression when added upstream of different promoters, as first demonstrated in mice and NHPs to direct coagulation factor IX expression in the liver from AAV9 vectors.223 The same strategy was also used to enhance specific gene expression in the heart or in skeletal muscles.224,225 Computational approaches have also been used to assemble libraries of completely synthetic promoters that are active in specific cell types.226 This technology has already allowed identification of new tissue-specific promoters of short length and high strength compared with natural promoter sequences that would be useful for AAV-mediated gene therapy in different tissues, including liver, muscle, retina, and brain.227,228,229 In addition to tissue specificity, such synthetic promoters can be selected to be constitutive, or inducible or repressible by chemical stimuli, as recently reported using liver as the target tissue 230.

AAV terminal repeats

In the process of screening promoter specificity and strength, it is critical to select the final candidates in an AAV vector context; i.e., in the presence of AAV terminal repeats in cis. Indeed, it is well known that AAV-2 inverted terminal repeat (ITR) sequence displays some promoter activity,231 which was shown to interfere with drug-inducible promoter regulation and was mapped within the A/D sequence element.232 Several putative transcription factor binding motifs have been found within the AAV-2 ITR sequence through bioinformatic analysis, and, substituting the D sequence in one, the ITR was reported to change transgene expression levels from the same promoter, both in vitro and in vivo.233,234 Substitution of AAV-2 terminal repeats with ITR from other serotypes was also shown to modify gene transfer efficiency, as shown using vectors with serotype 2 or serotype 3 ITRs packaged into an AAV-3 capsid.235 It is theoretically possible to encapsidate AAV vector genomes having ITR from any serotype into any AAV capsid serotype provided that the appropriate Rep proteins are used,236,237 so changing the ITR sequence depending on the promoter and the target tissue might have to be considered in the future.

RNA processing elements

Beyond promoter choice, other aspects of the transgene expression cassette design need to be considered to improve expression and, thus, increase vector potency.

First, it is now obvious that an intronic sequence must be included for optimal transgene RNA processing and mRNA export. A number of intronic sequences of varying length have been described and used in combination with different promoters (hybrid beta-actin/beta-globin,238 hybrid adenovirus/immunoglobin,239 hybrid beta-globin/Ig heavy chain or minute virus of mice (MVM)240). The addition of processing sequences at the 3′ end of the transgene has also been shown to improve transgene expression, such as the Woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element (WPRE), which can promote mRNA export to the cytoplasm,241,242,243 or short UC-rich elements, which can improve mRNA stability through PCPB1 protein binding.244 The addition of an S/MAR sequence can also improve transgene expression, and it has been shown to allow episomal vector persistence in proliferating cells with integration-deficient lentiviral vectors (IDLV),245,246 and, more recently, with AAV,247 which could be an advantage in differentiating or renewing tissues, such as the liver or the damaged muscle.

Selection of the polyadenylation signal can also affect transgene expression levels. The choice of a very short poly(A) signal is sometimes dictated by transgene size but can have a negative impact on expression levels. For example, short synthetic or shortened versions of the SV40 poly(A) signals were shown to decrease transgene expression from AAV vectors compared with bGH or SV40 larger sequences.242

In addition to the poly(A) signal required for transgene expression, a second poly(A) signal placed in the reverse orientation relative to the transgene sequence should be considered. Indeed, a recent study has shown that transcription of antisense RNA from the 3′ ITR can induce an innate immune response triggered by cellular double-stranded RNA sensors, resulting in IFN-β expression and lower transgene levels, and this was prevented by the addition of a reverse poly(A) signal close to the 3′ ITR to stop antisense transcription.204