Abstract

Background:

Arteriovenous fistulae (AVF) are the preferred access for hemodialysis but still have poor rates of maturation and patency limiting their clinical use. The underlying mechanisms of venous remodeling remain poorly understood, and only limited numbers of unbiased approaches have been reported.

Methods:

Biological Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis and differentially expressed genes (DEG) analysis were performed for three AVF datasets. A microRNA enrichment analysis and L1000CDS2 query were performed to identify factors predicting AVF patency.

Results:

The inflammatory and immune responses were activated during both early and late phases of AVF maturation, with upregulation of neutrophil and leukocyte regulation, cytokine production and cytokine-mediated signaling. In men with failed AVF, negative regulation of myeloid-leukocyte differentiation and regulation of macrophage activation were significantly upregulated. Compared to non-diabetic patients, diabetic patients had significantly reduced immune response-related enrichment such as cell activation in immune response, regulation of immune-effector process and positive regulation of defense response; in addition, diabetic patients showed no enrichment of the immune response-regulating signaling pathway.

Conclusions:

These data show coordinated, and differential regulation of genes associated with AVF maturation, and different patterns of several pathways are associated with sex differences in AVF failure. Inflammatory and immune responses are activated during AVF maturation and diabetes may impair AVF maturation by altering these responses. These findings suggest several novel molecular targets to improve sex specific AVF maturation.

Keywords: Arteriovenous fistulae, GO for biological processes, inflammation, diabetes, sex difference

Introduction

Arteriovenous fistulae (AVF) are currently the preferred modality for vascular access for hemodialysis in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (1, 2). For satisfactory use in hemodialysis, AVF outflow veins are required to mature sufficiently, with venous dilation to >6 mm and increased venous wall thickness to withstand wall puncture with large needles 3 times a week (2, 3). However, AVF maturation is not well understood, and approximately 20% to 60% of AVF do not mature, resulting in inability to use the AVF for hemodialysis. (2, 4–6). The poor rates of AVF maturation suggest a need to understand venous remodeling that leads to successful AVF maturation to improve care for patients with ESRD.

Multiple risk factors such as diabetes and female sex predict AVF failure (7–12); however, the underlying mechanisms of these poor outcomes are still not well understood. AVF maturation is also reduced in diabetic patients (13–15) but diabetics have similar venous hemodynamics as non-diabetic patients, suggesting that diabetic and non-diabetic patients are comparable candidates for AVF creation (16) but have other factors that may lead to AVF failure. Preclinical models have reported that diminished patency of female AVF is preceded by lower peak velocity, reduced magnitudes of shear stress, and less laminar flow during remodeling (17). In addition, AVF in women show increased venous fibrosis that can result in poor vascular remodeling (18), suggesting several mechanisms of reduced venous remodeling in women. With a limited number of studies on AVF maturation examining either diabetic patients or women, the potential mechanisms associated with AVF failure remain unclear.

Advances in bioinformatics can now identify biologic processes relevant to vascular pathophysiology (19–21). Gene expression profiles and microRNA analysis can identify molecular mechanisms of venous remodeling including regulation of extracellular matrix components and genes associated with failure during AVF maturation (22–25). However, gene expression profiles stratified for several clinical factors at high risk for AVF failure have not been reported. We used Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of several gene expression profiles related to AVF maturation in both women and diabetic patients. We hypothesized that AVF maturation is characterized by regulation of the inflammatory and immune systems, and that poor outcomes in both women and diabetic patients are driven by different patterns of pathway enrichment compared to men or non-diabetic patients.

Materials and Methods

We used three different high throughput RNA and gene expression microarray sequencing datasets obtained from AVF samples that have been previously reported. Two of these datasets were obtained from the publicly available National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) dataset (datasets 1 and 3 in Table 1) (26, 27). The third dataset is a gene expression microarray dataset compiled from the murine aortocaval fistula model (23). (dataset 2 in Table 1).

Table 1.

Datasets.

| Dataset number | Data source | Source Organism | Dataset Details | Analysis Cohorts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nath et al (22) | Mus | RNA expression profiles of unmatched veins and a carotid-jugular AVF from CKD mice | • Sham vs AVF |

| GEO series GSE116268 | Muscularis | |||

|

| ||||

| 2 | Hall et al (23) | Mus | Gene expression microarray analysis using MouseGene 1.0 ST array from aortocaval AVF | • Sham vs AVF |

| Muscularis | ||||

|

| ||||

| 3 | Martinez et al (24) | Homo | RNA expression profiles of matched native veins and AVF from brachial-basilic AVF | • Matured vs Failed AVF |

| GEO series GSE119296 | Sapiens | • Men vs Women | ||

| • Diabetic vs non-diabetic patients | ||||

Murine and Human AVF Datasets

The first RNA-sequencing dataset (dataset 1: GSE116268), reported the analysis of 6 unmatched samples (murine carotid-jugular AVF vs Sham) that were harvested from mice with chronic kidney disease (CKD) at day 7 after AVF creation (22). We previously reported the second dataset (dataset 2) that analyzed murine aortocaval fistula whole-genome gene expression microarray data using the Mouse Gene 1.0 ST array, compared to the IVC of sham-operated wild type mice (23).

The third dataset (dataset 3: GSE119296) reported whole-genome transcriptomics and RNA sequencing of matched pre-access veins and AVF from human patients who had two-stage (brachial-basilic) AVF creation and compared matured with failed AVF. This dataset contained RNA expression profiles in 19 matched pre-access veins and corresponding AVF samples with detailed information on demographics and clinical characteristics (24). The 19 matched pre-access veins and corresponding AVF RNA expression profiles were re-grouped based on sex and diabetes to determine the effect of these clinical variables on AVF maturation.

Differential expression analysis

For RNA-sequence expression data from the murine AVF datasets, dataset 1: GSE116268 and dataset 2, the Limma package of R was used to identify the differentially expressed genes (DEG) (28). RNA-sequence expression data from selected subgroups in dataset 3 (GSE119296), was analyzed with a limma powers differential expression analysis that was conducted by BioJupies, a web-based analysis tool (29, 30). P-values were adjusted with the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Genes with cutoffs of |Log2 fold change|>1.5 and adjusted P-value <0.05 were defined as DEG. Volcano plots were generated using OmicStudio tools (31).

Gene Ontology (GO) for biological process enrichment analysis

The GO enrichment analysis tool in BioJupies was connected with Enrichr to identify biological processes that are over-represented in the increased or decreased DEG (30, 32). GO enrichment results were uploaded to OmicStudio for report creation (31).

Gene overlap analysis

The human AVF dataset (dataset 3: GSE119296) was regrouped based diabetic status. Then, lists of significantly increased DEG of matured AVF samples and matched pre-access veins from the two patient groups (diabetic vs. non-diabetic) were uploaded into Metascape, a web-based portal designed to provide a comprehensive gene list annotation and analysis (33). Go enrichment was then used to determine the functional overlap of the input gene lists and described using Cisco plots.

Enriched ontology cluster analysis

Statistically enriched biological process GO terms were obtained from Metascape as described above (33). Then, accumulative hypergeometric p-values and enrichment factors were calculated and subsequently used for filtering. Based on Kappa-statistical similarities among their gene memberships, significant terms were hierarchically clustered into a tree. Next, a 0.3 kappa score was applied as the threshold to cast the tree into term clusters. Then the GO term with the best P-value was selected within each cluster as its representative GO term and displayed in a dendrogram. A clustered heatmap colored by P-value was created using Metascape (33, 34).

L1000CDS2 query

The library of integrated network-based cellular signatures (LINCS) L1000 is a genome-wide transcriptomics assay. The LINCS-L1000 dataset has been combined with a geometrical multivariate computational method of extracting messenger RNA expression data, known as characteristic direction (CD), resulting in a web-based search engine called L1000CDS2 that is freely accessible via various open-source code implementations (35, 36). The L1000CDS2 tool of BioJupies was used to identify small molecules and drugs that mimic or reverse the gene expression signature of failed AVF that were generated as described above (30). The L1000CDS2 analysis was performed by submitting the top 2000 genes in the gene expression signature to the L1000CDS2 signature search API (36); the top 5 results were displayed using bar charts.

MicroRNA (miRNA) enrichment analysis

The miRNA enrichment analysis tool in BioJupies was run to obtain enriched miRNA results using Enrichr (30, 32). Significant results were determined by using a cut-off of P-value <0.05 after applying Benjamini-Hochberg correction. We focused on human miRNA experimentally identified from the TargetScan library (37); the top 30 miRNA targeting down-regulated genes in failed AVF were listed in tables, and Venn diagrams for total and selected miRNA were created using OmicStudio tools (31).

Immune cell abundance analysis

We submitted the original RNA-Seq data of matured AVF from patients in dataset 3 (GSE119296) to Immune Cell Abundance Identifier (ImmuCellAI), an online tool that estimates the abundance of immune cells from an uploaded gene expression dataset (38). Immune cell abundance in samples was performed according to the instructions for use; box plots were created by GraphPad Prism 8 based on abundance results.

Statistical analysis

Data on immune cell abundance analysis were analyzed using Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Normality of distribution was assessed using Q-Q plots or the Shapiro-Wilk test. Groups were compared using unpaired t-tests, or unpaired t-tests with Welch’s correction or the Mann-Whitney test based on patterns of distribution. Statistical significance was set at a P-value < 0.05.

Results

Activation of the inflammatory and immune responses during venous remodeling

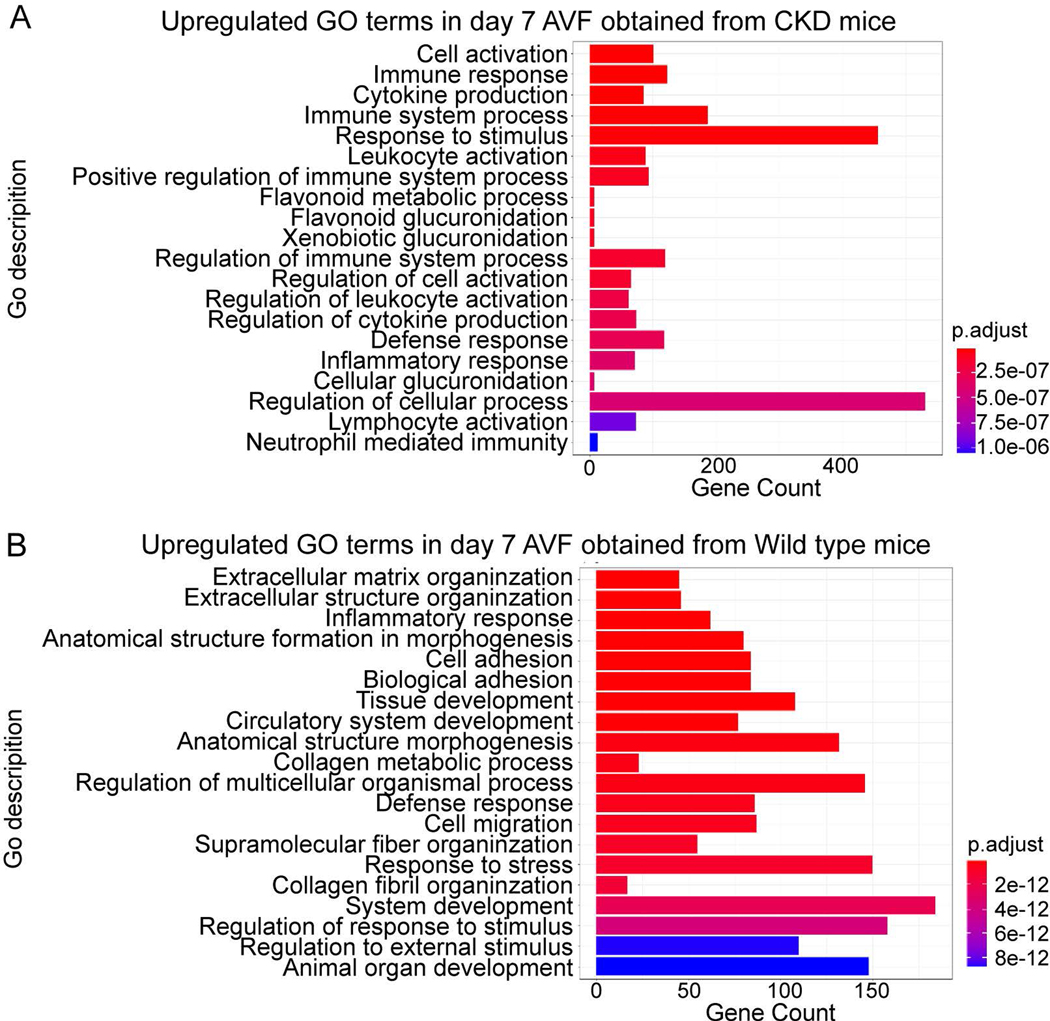

To determine the role of the inflammatory and immune responses on venous remodeling during AVF maturation, we evaluated both murine and human AVF datasets. The murine datasets were used to assess several biological processes during the early stage (day 7) of AVF maturation. Analysis of the murine carotid-jugular AVF dataset (dataset 1: GSE116268) showed that mRNA expression related to cytokine production, leukocyte activation, processes relating to positive regulation of the immune response, regulation of leukocyte activation, cytokine production and inflammatory responses were significantly upregulated in AVF compared with veins derived from sham-operated mice (Fig. 1. A). This data suggests that the inflammatory and immune responses are activated during the early phase of AVF maturation; therefore, we confirmed the role of the inflammatory and immune responses using an alternate murine AVF model (aortocaval AVF; dataset 2) (23). Similar to dataset 1, GO term enrichment analysis of increased DEG showed significant upregulation of mRNA related to the inflammatory response and the defense response, as well as other related processes such as cell adhesion and migration (Fig. 1. B). These data suggest that the inflammatory and immune responses are upregulated during early venous remodeling.

Figure 1.

GO terms for biological process enrichment analysis of murine AVF. A) Up-regulated GO terms for biological processes from AVF harvested at day 7 from carotid-jugular AVF in mice with CKD, compared to sham-operated mice (Dataset 1: GSE116268). The GO terms are ranked based on adjusted P-values. B) Up-regulated GO terms for biological process from aortocaval AVF harvested at day 7 from wild type mice compared with a sham group (dataset 2). CKD, chronic kidney disease.

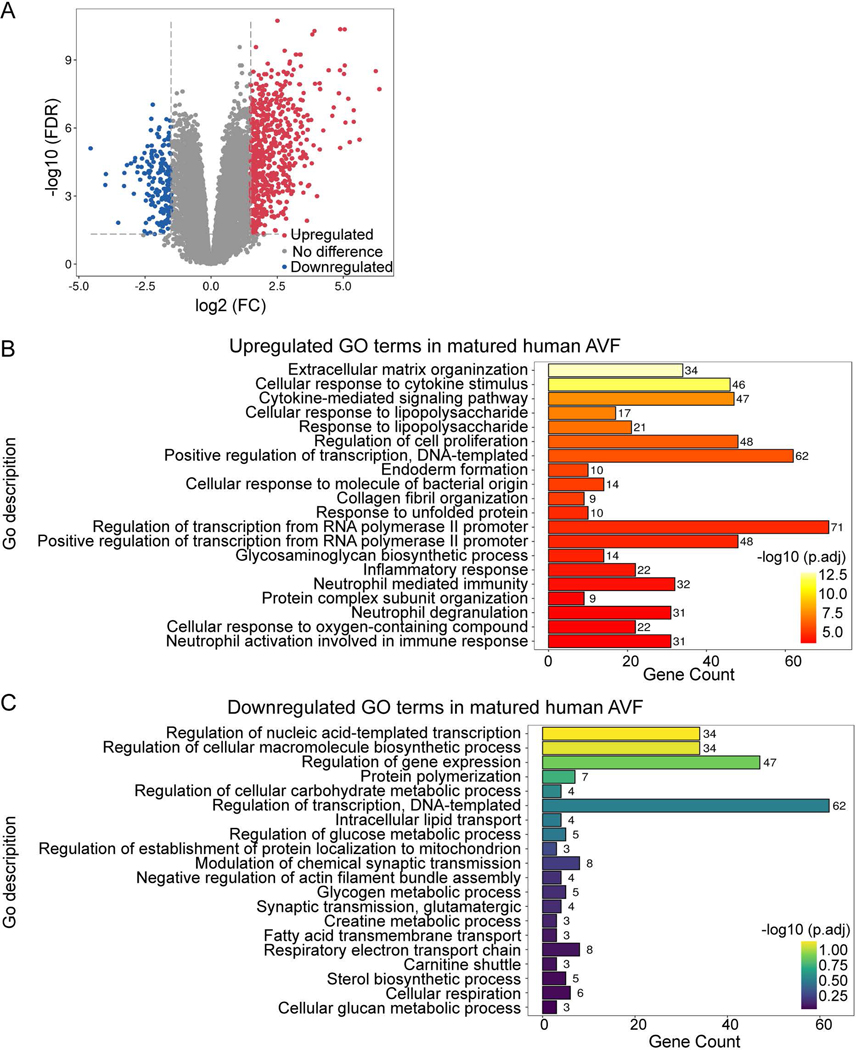

To determine whether the role of GO processes such as the inflammatory and immune responses that were identified in the murine datasets are relevant to human AVF maturation, we used a human brachial-basilic AVF dataset (dataset 3: GSE119296) and compared groups based on AVF maturity (matured AVF vs failed AVF). The cohort of matured AVF consisted of 11 matched pairs of veins and AVF yielding 762 DEG in mature AVF (592 up-regulated and 170 down-regulated) with a significant fold change > 1.5 (Fig. 2. A). GO term enrichment analysis comparing the mature AVF to veins showed that the upregulated DEG were related to extracellular matrix reorganization, cellular proliferation, RNA synthesis and protein synthesis (Fig. 2. B, C). Interestingly, there was an upregulated cellular response to cytokine stimulus, cytokine-mediated signaling pathway, as well as neutrophil activation, degranulation and neutrophil mediated immunity, suggesting upregulation of the immune response (Fig. 2. B). Among the downregulated DEG, there was no significant enrichment of biological processes relating to immune response (Fig. 2. C). This data from human AVF suggests that the inflammatory and immune responses are active, at least at later stages of AVF maturation (6–15 weeks). In toto, these results show that the inflammatory and immune responses are present during AVF maturation, suggesting their mechanistic importance for venous remodeling.

Figure 2.

Differential expression profiles and GO terms for biological process enrichment analysis of human AVF. A) Volcano plot showing expression profiles of genes from mature AVF compared with the corresponding pre-access veins (Dataset 3: GSE119296). A fold change value of >1.5 was selected for identifying DEG. Up-regulated DEG are in red; down-regulated are in blue; Genes without significant expression change are in grey. B-C) Significantly overrepresented GO terms for biological process among up-regulated (Fig. 2B) or down-regulated (Fig. 2C) genes presented in (Fig. 2A). The GO terms are ranked by adjusted P-values. Gene counts show the number of hits in the corresponding GO term family.

AVF maturation in diabetics is associated with reduced inflammatory and immune responses

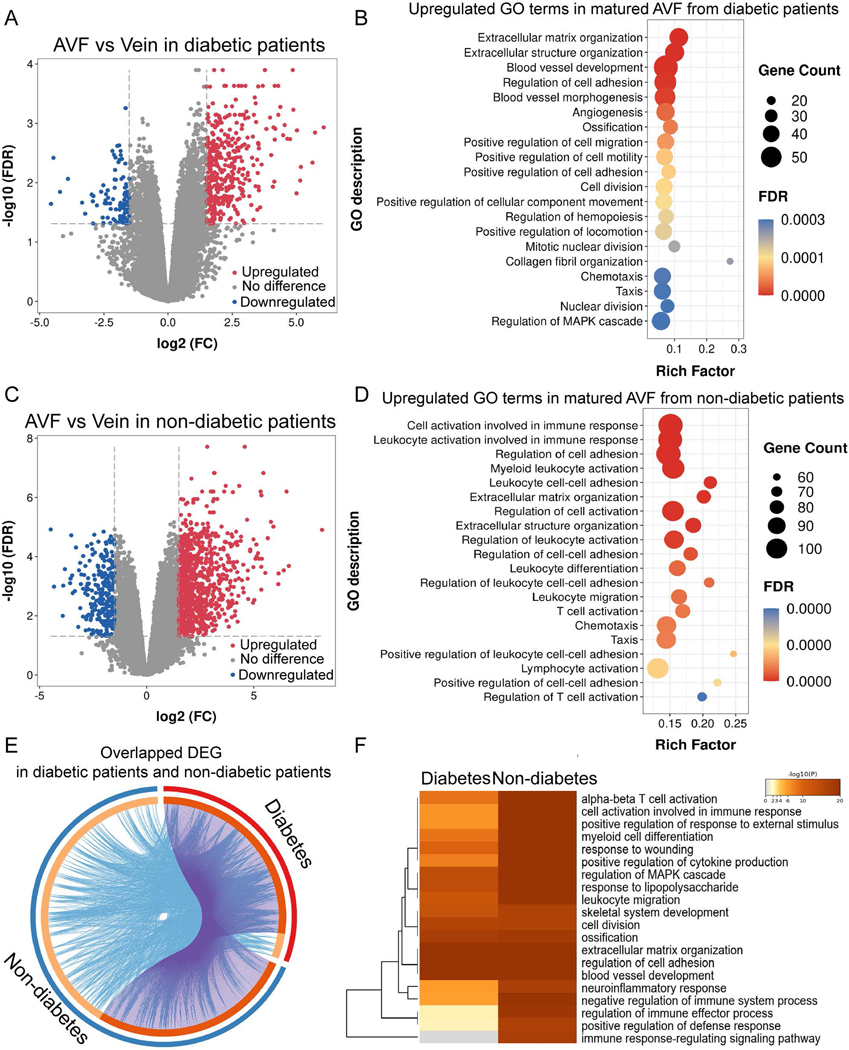

Since diabetes is associated with AVF failure, we determined the effect of diabetes on the biological processes in the human AVF dataset (dataset 3: GSE119296). Differential expression analysis showed 488 DEG (394 up-regulated and 94 down-regulated) in diabetic patients and 1128 DEG (870 up-regulated and 258 down-regulated) in non-diabetic patients (Fig. 3. A, C). Diabetic patients showed less enrichment of biologic processes relating to inflammatory and immune responses, such as cell activation, myeloid leukocyte activation, leukocyte and lymphocyte activation (Fig. 3. B, D); diabetic patients had significant upregulation of proliferative processes such as extracellular matrix and structure organization, blood vessel morphogenesis, angiogenesis, regulation of cell motility, cell migration and cell adhesion (Fig. 3. E).

Figure 3.

Differential expression profiles and enriched GO terms of mature AVF from diabetic and non-diabetic patients. A) & C) Volcano plots showing expression profiles of genes in mature AVF compared with veins from diabetic patients (Fig. 3A) or non-diabetic patients (Fig. 3C). A 1.5-fold change was used as the threshold to select DEG. Up-regulated DEG are in red; down-regulated are in blue; genes without significant change in grey. B) & D) Bubble charts showing the top 20 significantly overrepresented GO terms for biological process among upregulated genes shown in (Fig. 3A) and (Fig. 3C), respectively. FDR is the P-value adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. FDR < 0.05. Rich factor in the X-axis represents the enrichment levels. The size of dots indicates gene numbers enriched in the GO process, while the color of the dots represents FDR. E) Circos plot showing overlap of the significantly up-regulated genes in matured AVF from diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Outer arc represents AVF from the diabetic patients (red) or non-diabetic patients (blue). Inner arc in dark orange color represents genes that appear in both groups; light orange color represents genes that are unique to that group. Purple lines link the same gene that are shared by two groups. Blue lines link the different genes where they fall into the same significant GO term. The greater the number of purple links and the longer the dark orange arcs suggest greater overlap among the gene lists from groups. Blue links indicate the amount of functional overlap among the two gene groups. F) Heatmap showing the representative GO terms for biological processes, selected using the most significant P-value, through cluster enrichment analysis of up-regulated DEG between AVF from diabetic or non-diabetic patients. The heatmap cells are colored by their P-values. A white cell indicates lack of enrichment for that term in the diabetic group.

Since our data suggests activation of the inflammatory and immune responses during AVF maturation (Fig. 1, 2), we determined the effect of diabetes on inflammatory and immune activation in this dataset. Diabetic patients showed significant reduction in immune response-related enrichment such as cell activation in immune response, regulation of immune-effector process and positive regulation of defense response; notably, there was no enrichment of immune response-regulating signaling pathways in diabetic patients (Fig. 3. F). This data suggests that diabetic patients show reduced inflammatory and immune responses during AVF maturation.

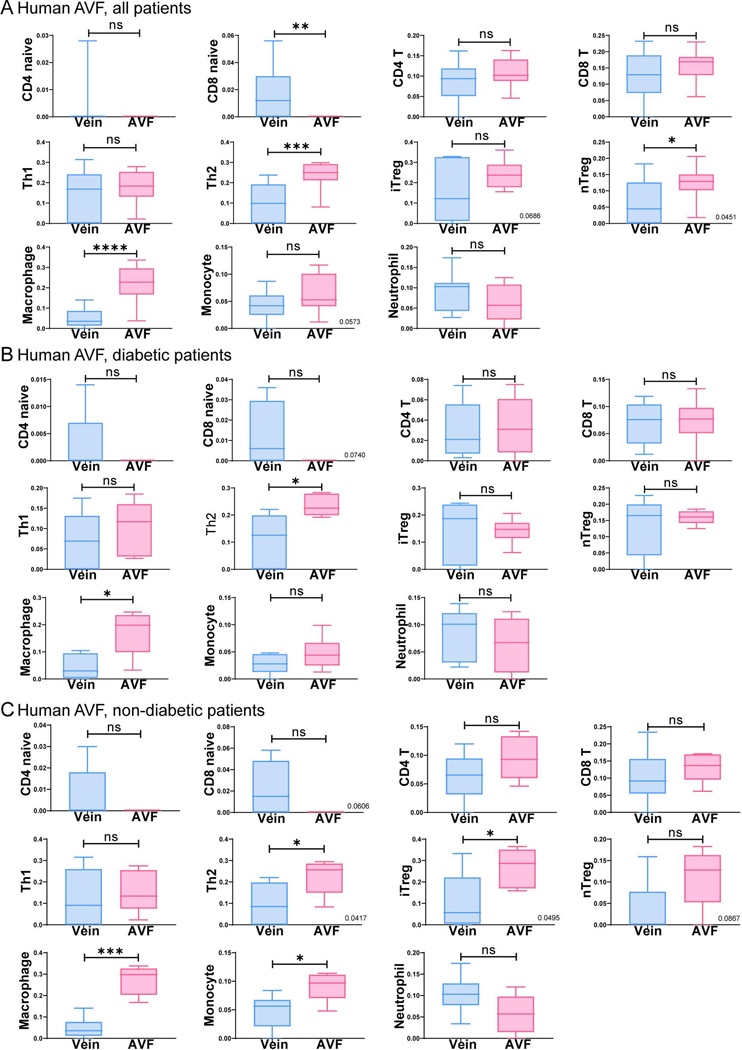

Since the GO process data suggests reduced inflammatory and immune responses in diabetic patients, we next determined the distribution of immune cells during AVF maturation in diabetic and non-diabetic patients (dataset 3: GSE119296). Regardless of diabetic status, there was increased infiltration of immune cells, including T helper type 2 (Th2) cells, macrophages and natural regulatory T-cells in AVF compared to pre-access veins; no significant differences were observed in infiltration of other immune cells (Fig. 4). Although there were no significant differences in immune cell distribution, based on diabetic status, these data show several types of immune cells are present during AVF maturation.

Figure 4.

Immune cell abundance analysis comparing matured AVF to veins in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. A-C) Boxplots show the abundant immune cells in matured AVF compared to veins in all patients (Fig. 4A, n=11), patients with diabetes (Fig. 4B, n=5 for AVF; n=6 for control) and non-diabetic patients (Fig. 4C, n=6 for AVF; n=5 for the control). Student t-test was used to analyze data. Veins are in blue; AVF are in pink.

Sex differences during AVF maturation

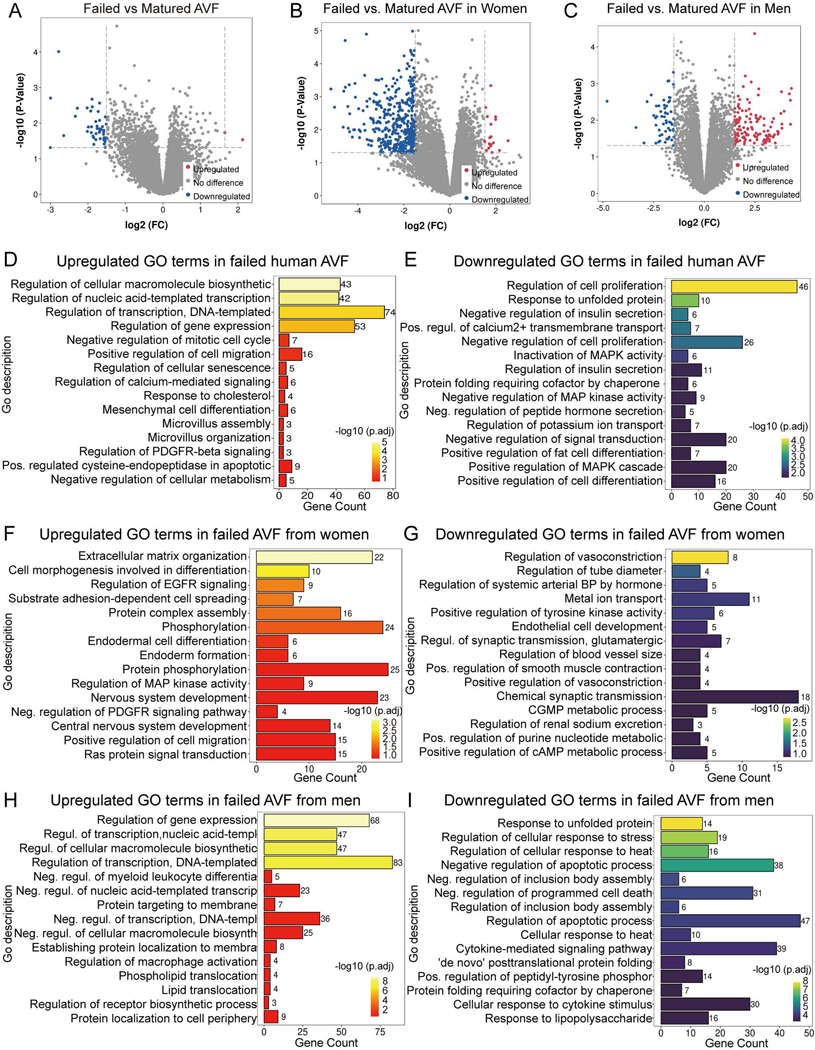

Since women have higher rates of AVF failure and worse AVF patency compared to men, we next determined whether there were sex differences in the human dataset (dataset 3: GSE119296). The dataset was stratified based on sex and the differences in biologic processes were evaluated in failed and mature samples. In the dataset there were 46 DEG (2 upregulated and 44 downregulated) in failed AVF samples compared to mature AVF, regardless of sex. Stratified by sex, failed AVF from women showed 428 DEG (18 upregulated and 410 downregulated) compared to mature AVF; failed AVF from men showed 174 DEG (118 upregulated and 56 downregulated; (Fig. 5. A–C). The biological processes associated with gene expression and cellular macromolecule synthesis were significantly enriched in upregulated DEG of failed AVF in all patients regardless of sex. Cell proliferation, protein folding, cell differentiation, metal ion transport and MAPK activity were significantly down-regulated (Fig. 5. D, E).

Figure 5.

Sex-specific differential expression profiles and biological process GO terms enrichment of failed vs. mature AVF. A-C) Volcano plots showing expression profiles of genes in failed AVF compared with matured AVF from all patients (Fig. 5A, matured AVF n=11; failed AVF n=8), women (Fig. 5B, matured AVF n=5; failed AVF n=4), and men (Fig. 5C, matured AVF n=6; failed AVF n=4). A 1.5-fold change was used as the threshold to select DEG. Up-regulated DEG in red; down-regulated in blue; no significant change in grey. D-I) Bar charts presenting the up-regulated (red-orange-yellow, left) or down-regulated (blue-green-yellow, right) GO terms for biological process in failed AVF compared with matured AVF in all patients (Fig. 6D, E), women (Fig. 6F, G) and men (Fig. 6H, I). The top 15 terms listed are ranked by adjusted P-values. Gene count shows the number of gene hits in the corresponding GO term family. Pos., positive; Neg., negative; Regul., regulation.

The analysis was then performed separately in the samples from women and men. In women, the most prominently upregulated GO terms in failed AVF were extracellular matrix organization, cell morphogenesis and spreading, EGFR signaling regulation and protein assembly; downregulated GO terms included regulation of vasoconstriction, tube diameter, hormone-mediated blood pressure and endothelial cell development (Fig. 5. F, G). In men, the GO terms regulation of gene expression, negative regulation of myeloid-leukocyte differentiation, regulation of macrophage activation, protein localization and lipid translocation were upregulated in failed AVF; the terms cellular response to unfolded protein, stress, heat, cytokines, cytokine-mediated signaling, as well as regulation of apoptosis and cell death, were significantly downregulated in failed AVF (Fig. 5. H, I). This data is consistent with sex differences in the biological process enrichment analysis of failed AVF, that is upregulation of macrophage activation and downregulation of cytokine-mediated responses were more common in men with failed AVF.

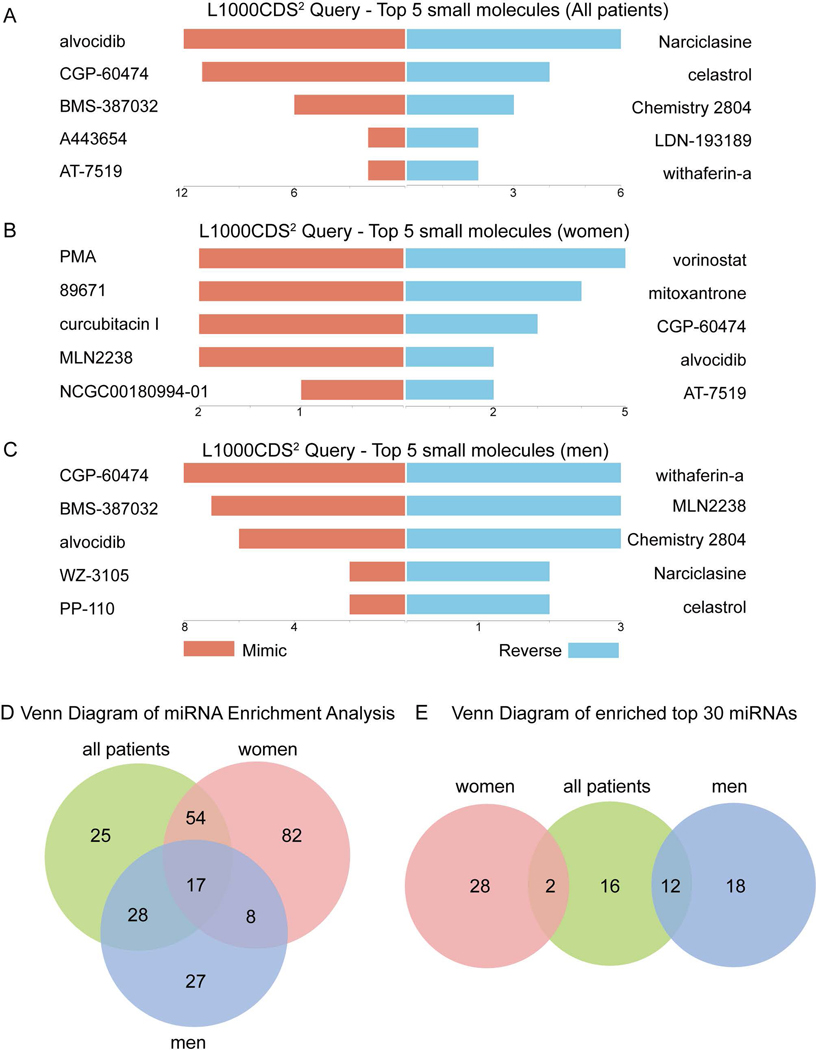

Gene expression signature targets to prevent AVF failure

Since differential gene expression analysis suggests sex-specific differences in women and men with failed AVF (Fig. 5), we next determined whether any of these differences suggest different therapeutic targets. We identified the top 5 small molecules that produced similar or opposite gene expression signatures in failed AVF compared to matured AVF, stratified by sex. Several anti-inflammatory small molecules such as CGP-60474 and alvocidib (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors) mimicked gene expression signatures of failure in men (Fig. 6. A, C); interestingly, these molecules tended to regulate gene expression in the opposite direction in women, with prevention of AVF failure in women (Fig. 6. B).

Figure 6.

Sex-specific gene expression signature targets to prevent AVF failure. A-C) Bar charts showing the top 5 small molecules identified by the L1000CDS2 query within all patients (Fig. 6A), women (Fig. 6B) and men (Fig. 6C). The left orange panel shows the small molecules that mimic the observed gene expression signature in failed AVF compared with mature AVF; the right blue panel shows the small molecules that reverse it. D) Venn diagram showing overlap of microRNA (miRNA) using miRNA enrichment analysis. The diagram was drawn according to all miRNA targeting the decreased DEG in failed AVF. E) Venn diagram showing the top 30 miRNA listed in the Tables 2–4 and their sex-specific overlap. All patients are shown in green; women in red; men in blue.

We also performed microRNA (miRNA) enrichment analysis to determine whether small non-coding RNA could influence post-translational down-regulated gene expression in failed AVF (Fig. 6. D). Women had more unique miRNA compared to men (Fig. 6. E). The top 30 miRNA expressed are listed in Tables 2–4, and there was little overlap between these groups in women and men (Fig. 6. E). This data suggests sex-specific differences in failed AVF.

Table 2.

Top 30 miRNA enrichment of down-regulated genes in all patients.

| No. | miRNA | adjusted P-value | Gene Count |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 1 | hsa-miR-4281 | 0.00912 | 70 |

| 2 | hsa-miR-648 | 0.00931 | 69 |

| 3 | hsa-miR-3659 | 0.01894 | 69 |

| 4 | hsa-miR-584 | 0.01139 | 67 |

| 5 | hsa-miR-4694–5p | 0.02181 | 66 |

| 6 | hsa-miR-215 | 0.00840 | 65 |

| 7 | hsa-miR-192 | 0.00855 | 65 |

| 8 | hsa-miR-496 | 0.01405 | 65 |

| 9 | hsa-miR-3177–5p | 0.01845 | 65 |

| 10 | hsa-miR-663 | 0.01870 | 65 |

| 11 | hsa-miR-1908 | 0.01887 | 65 |

| 12 | hsa-miR-4669 | 0.02255 | 64 |

| 13 | hsa-miR-4640–3p | 0.02288 | 63 |

| 14 | hsa-miR-4474–5p | 0.01963 | 62 |

| 15 | hsa-miR-3196 | 0.00325 | 61 |

| 16 | hsa-miR-3180 | 0.00348 | 61 |

| 17 | hsa-miR-3180–3p | 0.00375 | 61 |

| 18 | hsa-miR-3613–5p | 0.00521 | 60 |

| 19 | hsa-miR-4278 | 0.01641 | 59 |

| 20 | hsa-miR-744 | 0.00452 | 56 |

| 21 | hsa-miR-4258 | 0.01051 | 48 |

| 22 | hsa-miR-1911 | 0.01248 | 45 |

| 23 | hsa-miR-4707–5p | 0.01869 | 43 |

| 24 | hsa-miR-3178 | 0.00904 | 35 |

| 25 | hsa-miR-3141 | 0.02376 | 35 |

| 26 | hsa-miR-542–5p | 0.02356 | 32 |

| 27 | hsa-miR-3687 | 0.00314 | 25 |

| 28 | hsa-miR-4442 | 0.00331 | 25 |

| 29 | hsa-miR-3917 | 0.01086 | 25 |

| 30 | hsa-miR-4754 | 0.01553 | 18 |

Table 4.

Top 30 miRNA enrichment of down-regulated genes in men.

| No. | miRNA | adjusted P-value | Gene Count |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 1 | hsa-miR-1292 | 0.01758 | 71 |

| 2 | hsa-miR-4281 | 0.02619 | 68 |

| 3 | hsa-miR-4259 | 0.04403 | 67 |

| 4 | hsa-miR-663 | 0.02643 | 66 |

| 5 | hsa-miR-1908 | 0.02695 | 66 |

| 6 | hsa-miR-4640–3p | 0.02792 | 64 |

| 7 | hsa-miR-4713–3p | 0.03653 | 61 |

| 8 | hsa-miR-3196 | 0.00631 | 60 |

| 9 | hsa-miR-3180 | 0.00680 | 60 |

| 10 | hsa-miR-3180–3p | 0.00736 | 60 |

| 11 | hsa-miR-142–3p | 0.04167 | 56 |

| 12 | hsa-miR-4258 | 0.01143 | 50 |

| 13 | hsa-miR-638 | 0.03967 | 47 |

| 14 | hsa-miR-744 | 0.04581 | 47 |

| 15 | hsa-miR-1538 | 0.01039 | 44 |

| 16 | hsa-miR-4745–3p | 0.01084 | 44 |

| 17 | hsa-miR-4738–5p | 0.00316 | 43 |

| 18 | hsa-miR-4734 | 0.00828 | 42 |

| 19 | hsa-miR-4467 | 0.00945 | 37 |

| 20 | hsa-miR-4632 | 0.01714 | 37 |

| 21 | hsa-miR-3141 | 0.02622 | 36 |

| 22 | hsa-miR-4655–3p | 0.00968 | 32 |

| 23 | hsa-miR-3605–3p | 0.02092 | 32 |

| 24 | hsa-miR-4681 | 0.01190 | 30 |

| 25 | hsa-miR-3687 | 0.00542 | 25 |

| 26 | hsa-miR-4442 | 0.00596 | 25 |

| 27 | hsa-miR-574–3p | 0.00901 | 24 |

| 28 | hsa-miR-4304 | 0.02154 | 24 |

| 29 | hsa-miR-521 | 0.01994 | 22 |

| 30 | hsa-miR-4485 | 0.02571 | 20 |

Discussion

This study used advanced bioinformatics to show the robust inflammatory and immune responses present in venous remodeling that occurs during AVF maturation. Human AVF were collected 6–15 weeks after the initial AVF creation, suggesting that inflammatory and immune responses are active at least through later stages of AVF maturation (24). Interestingly, we noted that the inflammatory and immune responses were less prominent in diabetic patients (Fig. 3). In addition, there was sex differences (Fig. 5) that identified different potential therapeutics based on sex (Fig. 6). These data suggest that the inflammatory and immune responses are involved during venous remodeling that occurs during AVF maturation and that sex-specific differences in inflammation and/or the immune system may lead to different modes of AVF failure.

The immune response is involved in vascular remodeling. Notably, regulatory T-lymphocytes (Treg) suppress effector T-lymphocytes, blunting vascular injury in part through anti-inflammation and regulation of immunity (39, 40). In AVF, the absence of T cells hinders venous adaptation to the fistula environment, with lower flow rates, smaller luminal diameter, and less successful microphage infiltration, that is rescued by adaptive transfer of CD4+ lymphocytes (41). In addition, macrophages may perform critical roles during venous remodeling (42). Atorvastatin inhibits inflammatory macrophages and contributes to AVF outward remodeling and primary patency (43). CD44 promotes AVF maturation, in part via accumulation of M2 macrophages (44). In addition, deletion of macrophages by clodronate reduced wall thickness and decreased AVF patency, in part due to inhibition of both M1- and M2-type macrophages, suggesting a sophisticated role for macrophages during venous remodeling (45). Intriguingly, impaired venous outward remodeling was observed in RP105−/− mice, characterized by enriched M2-type macrophages, decreased M1-type macrophages and reduced T-cells (46). Our analysis is consistent with an abundance of macrophages and Th2 cells in mature AVF (Fig. 4), suggesting that the immune response is activated during AVF maturation. Considering that active inflammation promotes AVF failure (24, 47, 48), the balance of inflammatory and immune responses requires additional analyses; recent data suggests that T-cells are present very early during AVF maturation and regulate macrophages (49).

Diabetic patients have reduced AVF maturation, especially for forearm AVF (50). Intriguingly, one study showed that diabetes may not affect AVF patency or duration of maturation (51). However, smooth muscle cells collected from veins of diabetic patients show aberrant morphology, cytoskeletal disarray and impaired proliferative capacity, and diminished RhoA expression and activity, potential mechanisms of inferior venous remodeling in diabetic patients (52). Moreover, obesity-related diabetes is associated with chronic and low-grade inflammation in adipose tissue where immune cells infiltrate and regulate other organs (53–55). In addition, diabetic patients have elevated inflammatory factors, such as TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-8, suggesting that diabetes is associated with chronic inflammation and abnormal immune responses (56). Our analysis shows fewer immune-related responses were enriched in up-regulated DEG of matured AVF from diabetic patients (Fig. 3), suggesting that diabetes impacts AVF maturation by regulating inflammation and/or immunity. Further focused studies, specifically targeting immune and/or inflammatory pathways involved in AVF maturation could show potential therapeutic targets to improve AVF maturation in diabetic patients.

Women have reduced AVF maturation and increased failure, especially forearm fistulae (10, 50, 57). Although a mouse AVF model showed no difference in venous dilation and wall thickness between female and male mice (day 21), female mice had decreased AVF patency (day 42) (17). In a mouse model including chronic kidney disease, female veins treated with angioplasty had a smaller diameter, lumen vessel area, decreased wall shear stress, lower average peak systolic velocity, and increased neointimal hyperplasia, consistent with clinical observations (58). These sex differences in animal models may in part be due to differential expression of proteins involved in thrombosis, response to laminar flow, inflammation, and proliferation (17, 59). Multiple clinical studies have shown that women were more likely to initiate dialysis with a catheter and undergo more interventions to improve AVF patency (60, 61). Importantly, lower AVF patency in women is not explained by differences in vessel diameter (8). In human patients, failed AVF in women have differential enrichment patterns compared with men (Fig. 6), suggesting that different biological processes may account, at least in part, for the sex differences in clinical AVF failure. Interestingly, CGP-60474 and alvocidib were identified as candidates to improve AVF outcomes in women. CGP-60474 is an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase that acts as anti-inflammatory agent by impairing NF-κB activity (62). Alvocidib is also a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor that is used to treat breast cancer (63). These candidates for therapeutic translation suggest potential sex-specific strategies to improve AVF maturation.

This study has several limitations. First, this analysis is based on a limited subset of available datasets from open-access datasets. Importantly, veins and AVF from the human datasets were obtained from a small number of patients, limiting the generalizability of the findings from this study. Moreover, human AVF were harvested 6 weeks after AVF creation and therefore early changes responsible for AVF maturation and failure could not be assessed. In addition, certain potential low-flow AVF configurations, such as radial-cephalic or brachial-cephalic AVF, were not part of the analyzed datasets; however, some studies have shown no functional differences in clinical performance of cephalic AVF compared to basilic AVF (64, 65). The severity of diabetes was not characterized in this dataset, limiting the ability to stratify immune response impairment. In addition, the L1000CDS2 query is based on the signatures collected from in-vitro experiments with restricted accuracy to predict in vivo data. As such, the analyses presented require additional validation.

Future Directions

In conclusion, biological process enrichment analysis suggests that the inflammatory and immune responses are a component of venous remodeling that occurs during AVF maturation. Diabetes impacts venous remodeling and is associated with less inflammatory and immune responses, and there are different inflammatory and immune responses in men and women that may help interpret the clinically observed sex differences in AVF failure. Small drugs, molecules and miRNA may serve as novel therapeutic targets to improve the sex-specific outcomes of AVF maturation and patency in women. Future translational and clinical research targeting the immune and/or inflammatory pathways involved in AVF maturation could provide novel therapeutic targets to improve AVF maturation and utilization for patients dependent on hemodialysis.

Table 3.

Top 30 miRNA enrichment of down-regulated genes in women.

| No. | miRNA | adjusted P-value | Gene Count |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 1 | hsa-miR-4520b-3p | 0.00003 | 86 |

| 2 | hsa-miR-3682–3p | 0.00031 | 82 |

| 3 | hsa-miR-556–5p | 0.00015 | 80 |

| 4 | hsa-miR-550b | 0.00048 | 77 |

| 5 | hsa-miR-3152–3p | 0.00121 | 77 |

| 6 | hsa-miR-4327 | 0.00168 | 76 |

| 7 | hsa-miR-3147 | 0.00184 | 75 |

| 8 | hsa-miR-4529–3p | 0.00051 | 74 |

| 9 | hsa-miR-21 | 0.00117 | 74 |

| 10 | hsa-miR-590–5p | 0.00120 | 74 |

| 11 | hsa-miR-4764–3p | 0.00192 | 74 |

| 12 | hsa-miR-921 | 0.00183 | 73 |

| 13 | hsa-miR-4694–5p | 0.00213 | 72 |

| 14 | hsa-miR-4280 | 0.00029 | 71 |

| 15 | hsa-miR-4536 | 0.00145 | 71 |

| 16 | hsa-miR-591 | 0.00200 | 70 |

| 17 | hsa-miR-3935 | 0.00047 | 69 |

| 18 | hsa-miR-151–3p | 0.00137 | 66 |

| 19 | hsa-miR-3146 | 0.00177 | 66 |

| 20 | hsa-miR-4671–3p | 0.00066 | 64 |

| 21 | hsa-miR-103b | 0.00089 | 64 |

| 22 | hsa-miR-4473 | 0.00173 | 61 |

| 23 | hsa-miR-3613–5p | 0.00180 | 61 |

| 24 | hsa-miR-3655 | 0.00177 | 59 |

| 25 | hsa-miR-4540 | 0.00179 | 55 |

| 26 | hsa-miR-4661–5p | 0.00137 | 53 |

| 27 | hsa-miR-1204 | 0.00061 | 41 |

| 28 | hsa-miR-1247 | 0.00214 | 36 |

| 29 | hsa-miR-210 | 0.00118 | 31 |

| 30 | hsa-miR-147b | 0.00148 | 28 |

Funding Sources

This research was funded by US National Institute of Health (NIH), grant number R01-HL144476.

Statement of Ethics

This study did not require approval of the ethics committee since it is a secondary analysis of previously approved and published data.

List of abbreviations

- AVF

Arteriovenous fistulae

- CD

Characteristic direction

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- DEG

Differently expressed gene

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GO

Gene ontology

- GSEA

Gene set enrichment analysis

- LINCS

library of integrated network-based cellular signatures

- M1

M1 type macrophages

- M2

M2 type macrophages

- miRNA

microRNA

- Th2

T helper type 2

Footnotes

Statements

Supplementary Materials

The data within these analyses are included in the Supplementary data, which can be found at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4557696.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Ravani P, Palmer SC, Oliver MJ, et al. Associations between hemodialysis access type and clinical outcomes: a systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(3):465–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lok CE, Huber TS, Lee T, et al. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Vascular Access: 2019 Update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(4 Suppl 2):S1–s164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu DY, Chen EY, Wong DJ, et al. Vein graft adaptation and fistula maturation in the arterial environment. J Surg Res. 2014;188(1):162–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allon M, Robbin ML. Increasing arteriovenous fistulas in hemodialysis patients: problems and solutions. Kidney Int. 2002;62(4):1109–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allon M. Current management of vascular access. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(4):786–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung AK, Imrey PB, Alpers CE, et al. Intimal Hyperplasia, Stenosis, and Arteriovenous Fistula Maturation Failure in the Hemodialysis Fistula Maturation Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(10):3005–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almasri J, Alsawas M, Mainou M, et al. Outcomes of vascular access for hemodialysis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Vasc Surg. 2016;64(1):236–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller CD, Robbin ML, Allon M. Gender differences in outcomes of arteriovenous fistulas in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2003;63(1):346–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farber A, Imrey PB, Huber TS, et al. Multiple preoperative and intraoperative factors predict early fistula thrombosis in the Hemodialysis Fistula Maturation Study. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63(1):163–70 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bashar K, Zafar A, Elsheikh S, et al. Predictive parameters of arteriovenous fistula functional maturation in a population of patients with end-stage renal disease. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan Y, Ye D, Yang L, et al. A meta-analysis of the association between diabetic patients and AVF failure in dialysis. Ren Fail. 2018;40(1):379–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salmela B, Hartman J, Peltonen S, Albäck A, Lassila R. Thrombophilia and arteriovenous fistula survival in ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(6):962–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conte MS, Nugent HM, Gaccione P, Roy-Chaudhury P, Lawson JH. Influence of diabetes and perivascular allogeneic endothelial cell implants on arteriovenous fistula remodeling. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54(5):1383–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owens CD, Wake N, Kim JM, Hentschel D, Conte MS, Schanzer A. Endothelial function predicts positive arterial-venous fistula remodeling in subjects with stage IV and V chronic kidney disease. J Vasc Access. 2010;11(4):329–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eroglu E, Kocyigit I, Saraymen B, et al. The association of endothelial progenitor cell markers with arteriovenous fistula maturation in hemodialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2016;48(6):891–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sedlacek M, Teodorescu V, Falk A, Vassalotti JA, Uribarri J. Hemodialysis access placement with preoperative noninvasive vascular mapping: comparison between patients with and without diabetes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38(3):560–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kudze T, Ono S, Fereydooni A, et al. Altered hemodynamics during arteriovenous fistula remodeling leads to reduced fistula patency in female mice. JVS Vasc Sci. 2020;1:42–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cai C, Kilari S, Singh AK, et al. Differences in Transforming Growth Factor-β1/BMP7 Signaling and Venous Fibrosis Contribute to Female Sex Differences in Arteriovenous Fistulas. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(16):e017420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen YC, Bui AV, Diesch J, et al. A novel mouse model of atherosclerotic plaque instability for drug testing and mechanistic/therapeutic discoveries using gene and microRNA expression profiling. Circ Res. 2013;113(3):252–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levula M, Oksala N, Airla N, et al. Genes involved in systemic and arterial bed dependent atherosclerosis--Tampere Vascular study. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e33787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koizumi G, Kumai T, Egawa S, et al. Gene expression in the vascular wall of the aortic arch in spontaneously hypertensive hyperlipidemic model rats using DNA microarray analysis. Life Sci. 2013;93(15):495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nath KA, O’Brien DR, Croatt AJ, et al. The murine dialysis fistula model exhibits a senescence phenotype: pathobiological mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2018;315(5):F1493-F9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall MR, Yamamoto K, Protack CD, et al. Temporal regulation of venous extracellular matrix components during arteriovenous fistula maturation. J Vasc Access. 2015;16(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez L, Tabbara M, Duque JC, et al. Transcriptomics of Human Arteriovenous Fistula Failure: Genes Associated With Nonmaturation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;74(1):73–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jie K, Feng W, Boxiang Z, et al. Identification of Pathways and Key Genes in Venous Remodeling After Arteriovenous Fistula by Bioinformatics Analysis. Front Physiol. 2020;11:565240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):207–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omnibus GE. National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus [cited 2021 01/25/2021]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/.

- 28.Diboun I, Wernisch L, Orengo CA, Koltzenburg M. Microarray analysis after RNA amplification can detect pronounced differences in gene expression using limma. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7):e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torre D, Lachmann A, Ma’ayan A. BioJupies: Automated Generation of Interactive Notebooks for RNA-Seq Data Analysis in the Cloud. Cell Syst. 2018;7(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Studio O. Omic Studio Tools 2021. [cited 2021 01/25/2021]. Available from: https://www.omicstudio.cn/tool.

- 32.Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W90–W7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fernandez NF, Gundersen GW, Rahman A, et al. Clustergrammer, a web-based heatmap visualization and analysis tool for high-dimensional biological data. Sci Data. 2017;4:170151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clark NR, Hu KS, Feldmann AS, et al. The characteristic direction: a geometrical approach to identify differentially expressed genes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duan Q, Reid SP, Clark NR, et al. L1000CDS: LINCS L1000 characteristic direction signatures search engine. NPJ Syst Biol Appl. 2016;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam J-W, Bartel DP. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife. 2015;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miao Y-R, Zhang Q, Lei Q, et al. ImmuCellAI: A Unique Method for Comprehensive T-Cell Subsets Abundance Prediction and its Application in Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2020;7(7):1902880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barhoumi T, Kasal DA, Li MW, et al. T regulatory lymphocytes prevent angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular injury. Hypertension. 2011;57(3):469–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kasal DA, Barhoumi T, Li MW, et al. T regulatory lymphocytes prevent aldosterone-induced vascular injury. Hypertension. 2012;59(2):324–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duque JC, Martinez L, Mesa A, et al. CD4(+) lymphocytes improve venous blood flow in experimental arteriovenous fistulae. Surgery. 2015;158(2):529–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsubara Y, Kiwan G, Fereydooni A, Langford J, Dardik A. Distinct subsets of T cells and macrophages impact venous remodeling during arteriovenous fistula maturation. JVS-Vascular Science. 2020;1:207–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cui J, Kessinger CW, Jhajj HS, et al. Atorvastatin Reduces In Vivo Fibrin Deposition and Macrophage Accumulation, and Improves Primary Patency Duration and Maturation of Murine Arteriovenous Fistula. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(5):931–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuwahara G, Hashimoto T, Tsuneki M, et al. CD44 Promotes Inflammation and Extracellular Matrix Production During Arteriovenous Fistula Maturation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(6):1147–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo X, Fereydooni A, Isaji T, et al. Inhibition of the Akt1-mTORC1 Axis Alters Venous Remodeling to Improve Arteriovenous Fistula Patency. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):11046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bezhaeva T, Wong C, de Vries MR, et al. Deficiency of TLR4 homologue RP105 aggravates outward remodeling in a murine model of arteriovenous fistula failure. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):10269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang CJ, Ko YS, Ko PJ, et al. Thrombosed arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis access is characterized by a marked inflammatory activity. Kidney Int. 2005;68(3):1312–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sung SA, Ko GJ, Jo SK, Cho WY, Kim HK, Lee SY. Interleukin-10 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha polymorphisms in vascular access failure in patients on hemodialysis: preliminary data in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23(1):89–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsubara Y, Kiwan G, Liu J, et al. Inhibition of T-Cells by CsA (Cyclosporine A) Reduces Macrophage Accumulation to Regulate Venous Adaptive Remodeling and Increase Arteriovenous Maturation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021:ATVBAHA120315875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller PE, Tolwani A, Luscy CP, et al. Predictors of adequacy of arteriovenous fistulas in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1999;56(1):275–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mortaz SS, Davati A, Ahmadloo MK, et al. Evaluation of patency of arteriovenous fistula and its relative complications in diabetic patients. Urol J. 2013;10(2):894–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Riches K, Warburton P, O’Regan DJ, Turner NA, Porter KE. Type 2 diabetes impairs venous, but not arterial smooth muscle cell function: possible role of differential RhoA activity. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2014;15(3):141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lontchi-Yimagou E, Sobngwi E, Matsha TE, Kengne AP. Diabetes mellitus and inflammation. Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13(3):435–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shu CJ, Benoist C, Mathis D. The immune system’s involvement in obesity-driven type 2 diabetes. Semin Immunol. 2012;24(6):436–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guzik TJ, Skiba DS, Touyz RM, Harrison DG. The role of infiltrating immune cells in dysfunctional adipose tissue. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113(9):1009–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou T, Hu Z, Yang S, Sun L, Yu Z, Wang G. Role of Adaptive and Innate Immunity in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:7457269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilmink T, Hollingworth L, Powers S, Allen C, Dasgupta I. Natural History of Common Autologous Arteriovenous Fistulae: Consequences for Planning of Dialysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016;51(1):134–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cai C, Zhao C, Kilari S, et al. Effect of sex differences in treatment response to angioplasty in a murine arteriovenous fistula model. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2020;318(3):F565–F75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chan SM, Weininger G, Langford J, Jane-Wit D, Dardik A. Sex Differences in Inflammation During Venous Remodeling of Arteriovenous Fistulae. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:715114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee T, Qian J, Thamer M, Allon M. Gender Disparities in Vascular Access Surgical Outcomes in Elderly Hemodialysis Patients. Am J Nephrol. 2019;49(1):11–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arhuidese IJ, Faateh M, Meshkin RS, Calero A, Shames M, Malas MB. Gender-Based Utilization and Outcomes of Autogenous Fistulas and Prosthetic Grafts for Hemodialysis Access. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020;65:196–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Han HW, Hahn S, Jeong HY, et al. LINCS L1000 dataset-based repositioning of CGP-60474 as a highly potent anti-endotoxemic agent. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tan AR, Swain SM. Review of flavopiridol, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, as breast cancer therapy. Semin Oncol. 2002;29(3 Suppl 11):77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koksoy C, Demirci RK, Balci D, Solak T, Kose SK. Brachiobasilic versus brachiocephalic arteriovenous fistula: a prospective randomized study. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49(1):171–7 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ramanathan AK, Nader ND, Dryjski ML, et al. A retrospective review of basilic and cephalic vein-based fistulas. Vascular. 2011;19(2):97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]