Abstract

Current business challenges mean that understanding elements that can affect organizational performance represents a differential factor in maintaining competitiveness. In this context, the objective of this article is to conduct a Systematic Literature Review (SLR) of the relationship between dynamic capabilities, strategic behavior, and organizational performance. For this, A three-stage SLR protocol was used: (i) planning, (ii) conduct, and (iii) knowledge development. A total of 118 articles covering the publication period of 2006–2021 were included, which evidenced: (i) the grouping of words into three classes: “Knowledge Management,” “Measurement Instrument,” and “Organizational Environment”; (ii) the methodological framework; (iii) directions for future research. The findings reinforce the importance of the theoretical, methodological, and empirical relationship between the three constructs. Furthermore, the results indicate the relationship between the set of terms selected in each class, highlighting the strong connection between dynamic capabilities and competitive intensity. The main findings of the research show that organizations can expand or modify their processes by building and using dynamic capabilities as institutional factors, shaping strategic behavior to advance better performance.

Keywords: Organizational performance, Dynamic capabilities, Strategic behavior, Systematic literature review

Introduction

To achieve sustained competitive advantage and efficiency, organizations need to adapt to both internal and external environments to establish a position in their sector based on available resources, skills and capabilities (Behl et al. 2022). They must thus focus on strategic behaviors (Al-Ansaari et al. 2015; Adewunmi et al. 2017; Bilgili et al. 2022); a company’s strategic behavior informs its approach to activity monitoring and performance achievement (Masa’deh et al. 2018; Tsai and Tsai 2022).

In highly dynamic sectors, both the approach based on the Structure-Conduct-Performance paradigm and a resource-based approach are limited in their ability to explain the sources of competitive advantage and performance achieved from strategic choices. By emphasizing a company's adjustment to highly dynamic environments, while facing the challenges imposed by volatile sectors through integration, reconfiguration, competencies and renewal of resources, dynamic analysis is a promising alternative to understanding sustainable sources of advantage and how such advantages are developed and implemented (Medeiros et al. 2020). The current business environment is challenging for organization survival. Performance measurement mechanisms can guide strategy implementation through performance monitoring, enabling organizations to achieve strategic goals and collect useful data to improve their performance (Owais and Kiss 2020; Pekovic and Vogt 2021).

It is particularly important to understand how the relationship between the three constructs of dynamic capabilities, strategic behavior and organizational performance has been addressed in the scientific literature. The present article presents a Systematic Literature Review (SLR) of the relationship between these three constructs using the Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) databases. The SLR protocol comprises three phases: (i) planning the SLR; (ii) conducting the SLR; (iii) dissemination of knowledge (Tranfield et al. 2003; Kitchenham 2004; Biolchini et al. 2007).

Previous research has not incorporated a joint analysis of these three constructs. An example is Zhou et al. (2019), which showed how dynamic capability leads a company to obtain a competitive advantage and improve its organizational performance, understanding that dynamic capabilities will be effective when leveraged by good strategies. Ringov (2017) addressed the juxtaposition of conflicting statements about the relationship between coded dynamic capabilities and company performance at different levels of environmental dynamism, concluding that the performance contribution of coded dynamic capabilities decreases as the dynamic environment increases. Shams and Belyaeva (2018) only analyzed dynamic capability, but related it to similar themes such as strategic management and competitive advantage. Analysis of the relationship between strategic behavior and performance was identified and verified by Silveira-Martins et al. (2014) in the context of the wine industry in Portugal. Benitez and Damke (2016) addressed the relationship between strategic behavior and organizational performance, analyzing the behavior of small companies in the retail sector from the perspective of the Miles et al. (1978) typology.

This SLR is therefore the first to offer a joint analysis of all three constructs of dynamic capabilities, strategic behavior and organizational performance. It aims to further understand the evolution of these themes and provide insights for future empirical research. It demonstrates how a combination of these constructs can influence companies' organizational performance and help improve their strategies to achieve better results and organizational effectiveness.

After this brief introduction, the article is structured as follows: in the second section, the theoretical bases of the research are discussed; the third section contains a discussion of the applied methodological procedures; the results are presented and analyzed in the fourth section; the fifth section contains the conclusions and limitations of the review.

Background

Figure 1 shows the relationship between dynamic capabilities, strategic behavior and organizational performance.

Fig. 1.

Relationship between dynamic capabilities, strategic behavior and organizational performance.

Source: Research data

Dynamic capabilities

In recent years, a new approach has emerged from strategy theory that allows organizations to revise their tactics towards a comprehensive chance of success (Zea-Fernández et al. 2020; Michaelis et al. 2021). This novel approach, known as Dynamic Capabilities (DC) theory, focuses on an organization’s ability to create, renew, modify, integrate and reconfigure its mix of resources in a rapidly changing environment to achieve high returns, sustainability and long-term competitiveness (Teece et al. 1997; Londoño-Patiño and Acevedo-Álvarez 2018; Weiss and Kanbach 2021). There are three key aspects that motivate the use of DC theory: first, that companies with a high level of dynamic capabilities are intensely entrepreneurial; second, that these are formed by innovation and collaboration with other organizations; third, that the knowledge asset is the most difficult to replicate (Teece 2011; Villafuerte-Godínez and Leiva 2015).

According to Vivas-López (2013), dynamic capabilities, in addition to being a source of new resources for the company, are a powerful tool for organizational strategists. These capabilities will enable the activation and reorientation of the complex network of economic and organizational factors, helping to control the company’s evolution and enhance future options or business opportunities. Dynamic capabilities are therefore key factors in innovating and optimizing the overall strategic course. In a dynamic context (Schumpeterian, evolutionary, rapid change or high speed, according to different authors), if a company intends to maintain its competitive advantage, it must be able to change (adapt, evolve, renew, adopt and reconfigure) (Teece et al. 1997; Eisenhardt and Martin 2000). Consequently, the concept of dynamic capabilities emphasizes the ability of a company and its managers to continuously modify resource allocation in a flexible and adaptable way in response to environmental changes (Vivas-López, 2013).

The new school of dynamic capabilities indicates that one source of knowledge is universities. Dynamic capabilities contribute to the development of knowledge within higher education institutions, integrating curricula, encompassing the importance of creativity, knowledge transfer, protection of intangible resources, technological know-how, relationships and new forms of organization. Emphasis is placed on soft assets (knowledge) that allow the synchronization of internal and external resources to address environmental challenges (Teece 2007; Rodríguez-Lora et al. 2016).

According Vodovoz and May (2017), DC theory allows us to understand the value creation process mediated by operational capabilities. Case studies have reaffirmed the tendency of DC theory to represent, with quality, a theoretical framework for the analysis of aspects related to value creation (new products and service channels) and new business model development (to achieve new consumer niches).

Strategic behavior

Strategic behavior is of particular importance in organizations because it is linked to outcomes (Bruner et al. 1986) and considers the potential future reactions of others (Burks et al. 2009). According Mintzberg (1987), strategic behavior involves setting goals, determining actions and mobilizing resources to achieve these goals. Therefore, it also involves planning and executing behaviors that make achieving those goals possible. Behling and Lenzi (2019) argued that strategic behavior encompasses the process of organizational adaptation to environmental turbulence, involving the internal dynamics of the organization. In other words, strategic behavior is characterized by the ways companies align themselves with the external environment and the choices they make over time. Likewise, Krishnamoorthi and Mathew (2018) showed that strategic behavior is the result of an orientation to international evidence regarding competition, innovation, opportunities and added value through organized actions in adapting to market changes. According to Agrell and Teusch (2020), companies can collude with their rivals to increase company profits, for example, by setting prices above competitive levels. Furthermore, it may be rational for companies to propose mergers, even in the absence of any merger-related efficiencies, because the transaction allows them to exercise market power and raise prices (unilateral effects) or because mergers facilitate collusion (coordinated or collusive effects).

By separately analyzing the concept of strategy, Svobodová and Rajchlová (2020) claimed that the creation and implementation of strategy are essential for operational planning, as it increases efficiency and leads to long-term benefits. Each company must determinei its strategy based on the environment in which it operates, its portfolio and the specification of concepts, principles and detailed plans for development and behavioral approach. Hughes et al. (2021) presented the idea that contrasting behaviors drive strategic entrepreneurs and that opportunity-seeking behavior is a function of a company's entrepreneurial strategy. Through entrepreneurial behaviors, a company is expected to develop competence by identifying a flow of rich opportunities to foster innovation. However, opportunities alone cannot create innovation, as the latter also depends on the resources attracted to the company. The strategic management of resources is a construct that conceptualizes behavior in search of advantage (Yin et al. 2021).

According to Hussein and Hafedh (2020), strategic behaviors are one of the most important topics in the field of strategic management and organizational behavior. They also focus on the nature of the behaviors adopted by senior management when dealing with human resources within the organization and with other external parties. These behaviors represent the mechanism for many strategic future decisions. Strategic behavior influences human resources at different organizational levels, but reflects the orientations of senior leadership and affects the nature of strategic direction.

Effective decision-making is an area of strategic behavior that has been widely discussed in practice and research (Staszkiewicz and Szelągowska 2019; Khanin et al. 2021). Research is mainly based on two theories: the principal agent theory and the theory of market competition. The former emphasizes that managers are motivated by shareholders or owners to reduce production costs and optimize production processes; the latter highlights the impact of market competition outside a company on the strategic behavior of production, research and development (Zhao et al. 2021; Ball 2021).

Organizational performance

Organizational performance is the result of the ability of entrepreneurs to formulate strategies that align the organization with the increasingly complex and dynamic environmental changes, and is concerned with the measurable fulfillment of organizational objectives (Meinhardt et al. 2018; Abubakar et al. 2019; Schwens and Wagner 2019; Marzall et al. 2022). Laaksonen and Peltoniemi (2018) and Rehman et al. (2019) believe that organizational performance is a significant indicator in achieving established organizational goals and objectives. Lee and Choi (2003) and Martín-Castro (2015) showed that organizations that learn more efficiently show better long-term results than their competitors. Performance can also be enhanced by improving individual knowledge within a culture of continuous organizational learning.

Nitzl et al. (2019) suggested that the use of information related to organizational performance is intended to facilitate decision-making to fulfill predefined goals. Such uses (decision facilitators) include monitoring (setting and monitoring goals, comparing expected and actual results), focus of attention (providing guidelines for the organization) and uses of strategic decision-making (supporting non-routine decisions). Zehir et al. (2016) argued that when implementing a planned strategic objective, the goals are intended to achieve efficiency, effectiveness and innovation. Wood and Ogbonnaya (2018) showed that a model of mutual gains is capable of producing superior organizational performance, as it supports the high involvement of managers and leads to a mutually beneficial situation for both employees and employers. It is therefore a distinct management approach as it delivers high levels of employee satisfaction and well-being and encourages employees to take a positive attitude towards the organization. A high-performance work system promotes a strong organizational environment in which employees feel that they belong and thus are willing to make extra efforts to achieve organizational objectives and improve performance (Kellner et al. 2016). In other words, a high-performance work system results in an increase in the value, individuality and inimitability of employees’ knowledge and skills, which, in turn, generate a competitive advantage and better performance (Zhang and Morris 2014).

Considering the emergence of new technologies and changes in the market, customers and suppliers, in addition to crises, the dynamic capabilities of innovation, entrepreneurship, organizational learning and market orientation are recognized as capabilities to achieve advantage and improve the relationship between resources and organizational performance (Henri 2006).

Materials and methods

The present study comprises an SLR that aims to address the following research question: “How has the relationship between dynamic capabilities, strategic behavior and organizational performance been addressed in the scientific literature?”. The purpose is to highlight theoretical gaps to inform new research. We adopted the protocol developed by Tranfield et al. (2003), with three steps: (i) planning the SLR; (ii) conducting the SLR; (iii) disseminating knowledge. This protocol is widely used to review scientific literature in the field of management (Klewitz and Hansen 2014; Araújo et al. 2018; Rojon et al. 2021; Guido et al. 2022; Fabrizio et al. 2022).

Planning the SLR

To guarantee the originality of our review, we searched the Scopus and WoS (Core Collection) databases to identify possible reviews involving the concepts of organizational performance, dynamic capabilities and strategic behavior together. Scopus and WoS (Core Collection) are widely used in different fields of knowledge. In addition to serving as a tool for retrieving information, they also facilitate the selection and analysis of scientific literature from a range of interests published in many languages (Barnett and Lascar 2012; Okhovati et al. 2017). Although WoS records date back to 1945, the publications from Scopus start from 1960, therefore we used 1960 as the starting point in both databases. Table 1 presents the resulting strings and number of systematic review articles.

Table 1.

Strings and number of systematic review articles from the database searches

| Databases | String | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“organizational performance*”) AND (“dynamic capacity*” OR “dynamic capability*” OR “strategic behavior*”) AND (“systematic review” OR “systematic literature review”)) AND DOCTYPE (ar OR re) AND PUBYEAR > 1959 AND PUBYEAR < 2022) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) | 1 |

| Web of Science | TS = ((“organizational performance*”) AND (“dynamic capacity*” OR “dynamic capability*” OR “strategic behavior*”) AND (“systematic review” OR “systematic literature review”)) AND LANGUAGE:(English) Indexes = SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, AandHCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, ESCI Timespan = 1960–2021 | 0 |

Source: Research data

Our preliminary search found only one article that jointly addressed the three constructs and sought to demonstrate the important role of dynamic capabilities in the relationship between knowledge asset management and company performance (Moustaghfir 2008). The article argued that effective knowledge asset management increases the value of organizational competencies, which in turn support organizational processes, products and services. In this respect, dynamic resources assume the role of continuously modeling operational routines and competencies and, consequently, offer superior long-term performance. Moustaghfir (2008) drew attention to dynamic capabilities as a missing component in the relationship between knowledge assets and company performance. These insights represent the theoretical basis for the development of a conceptual framework for how the effective management of knowledge assets affects the overall performance of the business and improves value-generating activity. However, strategic behavior involves the accumulated knowledge that arises from decisions based on the organizational adaptation process in the face of environmental turbulence, which involves the dynamism of the organization (Behling and Lenzi 2019). It is therefore timely to conduct an SLR focusing on the direct relationship between dynamic capabilities, strategic behavior and organizational performance in view of this theoretical gap.

Conducting the SLR

The second step involved a broad and unbiased search of articles in the corpus with the aim of minimizing selection bias. The search strategy involved using keywords within the topics of organizational performance, dynamic capabilities and strategic behavior, combined with Boolean operators, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Number of articles founded in Scopus and Web of Science

| Databases | String | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“organizational performance*”) AND (“dynamic capacity*” OR “dynamic capability*” OR “strategic behavior*”)) AND (PUBYEAR > 1959 AND PUBYEAR < 2022) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA, “BUSI”) OR LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA, “ECON”)) AND ( LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) | 117 |

| Web of Science | TS = ((“organizational performance*”) AND (“dynamic capacity*”OR “dynamic capability*” OR “strategic behavior*”)) and Management or Business or Economics (Web of Science Categories) and English (Languages) and Article (Document Types) Indexes = SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, AandHCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, ESCI Timespan = 1960–2021 | 69 |

Source: Research data

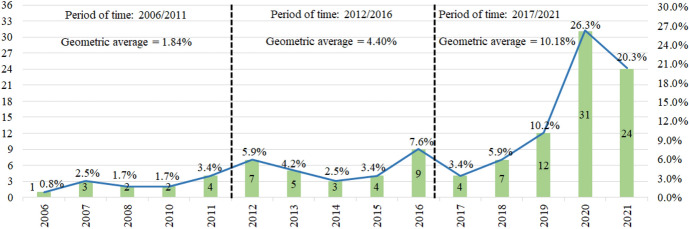

Of the 186 articles identified (Fig. 2), 24 duplicates were removed. Reputation and representativeness of journals were evaluated through the citation quartiles of Scimago Journal and Country Rank (SCIMAGO 2019); of the 162 remaining articles, 138 belonged to the first two citation quartiles (Q1 and Q2), meaning that a further 24 articles were excluded.

Fig. 2.

Selection process of textual corpus.

Source: Research data

Figure 2 shows that the 138 articles were from journals classified in SJR Q1 and Q2 (SCIMAGO 2019). Journals in these first two quartiles have lower acceptance rates than those in the third and fourth quartiles or those Without Classification (WC). They are therefore more productive, more selective and publish higher quality work than those in Q3 and Q4 (Gu and Blackmore 2017; Kaczam et al. 2022).

The thematic adherence of the articles was then evaluated. After reading the abstracts, 118 articles were determined to constitute the textual corpus, 79 from Scopus and 39 from WoS.

Knowledge dissemination

Knowledge dissemination comprises the presentation and discussion of the results and conclusions. We used RStudio, Gephi® and Iramuteq software (Bastian et al. 2009; Souza et al. 2018; Guleria and Kaur 2021). Descriptive information was obtained from the textual corpus and emerging themes via RStudio. The bibliographic coupling network was extracted with the aid of Gephi®. Word clusters and relationships between words were extracted with Iramuteq.

Results

This section presents the results of the textual corpus analysis (118 articles). First, a descriptive analysis of general characteristics is presented. Second, the bibliographic coupling network shows how the articles in the corpus are connected. Third, based on the descending hierarchical classification of words, a typology of three classes is presented. Finally, a set of suggestions for future research is provided.

Descriptive analysis

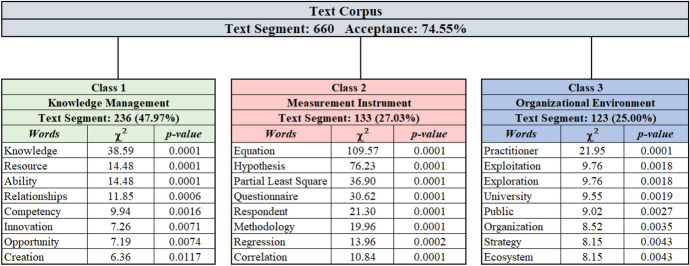

Figure 3 shows the annual distribution of the 118 articles in the textual corpus in the period between 2006 and 2021. A total of 12 articles were published in the first five years (2006 to 2011), which is equivalent in relative terms to 10.17% of the published works and a geometric average of 1.84%. This reveals a slight growth trend of this theme over time.

Fig. 3.

Annual distribution of the textual corpus.

Source: Research data

Between 2012 and 2016, 28 articles were published, corresponding to an accumulated 23.73% and an average production of around 4.40%. This revealed a rise of 2.56% from the previous five-year period, with particular mention for 2016 in which nine articles were published. The last 5 year period, 2017–2021, saw a further 78 articles, which corresponds in relative terms to 66.10% of the works published. This period also saw more diversity in the journals in which publications appeared, in addition to an average production of around 10.18% and a growth of 5.78% compared with the previous 5 year period. The year 2020 stands out as particularly productive, when there were 31 articles published, corresponding to 26.3% of the articles in the whole corpus. Figure 4 shows descriptive statistics on the topic of study.

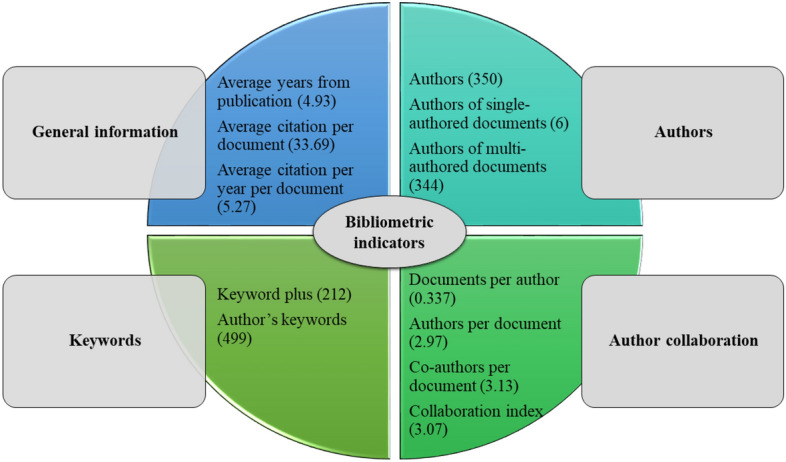

Fig. 4.

Corpus bibliometric indicators.

Source: Research data

Figure 4 shows that the corpus contains 89 journals and 350 authors and co-authors. There was an average of 33.69 citations per document, 5.27 citations per year per published document, 0.34 documents per author and 2.97 authors per published document. Regarding the level of cooperation between authors, there is a lack of researchers with single authorship, with some authors involved in more than one work. In other words, 31 authors share authorship with other authors, generating a collaboration index of 2.79, in addition to 3.04 co-authors per document. There were 499 keywords plus from the databases and 212 keywords defined by the authors, which is relevant to the formulation of the analyses of Zipf's third bibliometric law (Piantadosi 2014).

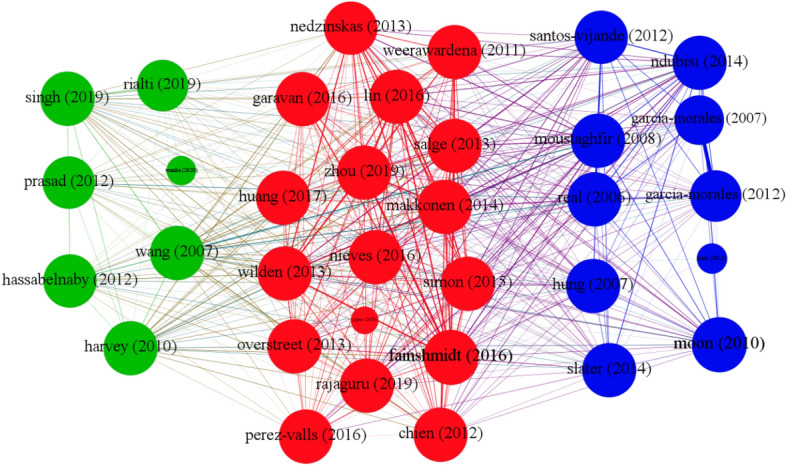

Bibliographic coupling analysis

The bibliographic coupling analysis aims to show which authors are closer to others in their reference lists, thus establishing theoretical alignment between these authors. This section aims to assess which authors are more bibliographically coupled in terms of intensity, highlighting the most prominent themes. The degree of theoretical or methodological proximity is evaluated from a list of references of pairs of researchers, based on the assumption that if two works refer to the same source, they have proximity. This consequently favors emergence of new research fronts, as advocated by Kessler (1963) and Zhao and Strotmann (2008).

To design the bibliographic coupling network using the Gephi® software, we used the distribution algorithm developed by Fruchterman and Reingold (1991). For the grouping of network elements, we used the modularity class statistic as indicated by Newman (2006) and where the size of the vertices is proportional to the eigenvector centrality statistic (Prell 2012).

Figure 5 shows the network formulation containing 34 authors coupled from the textual corpus based on their bibliographic references, distributed in three clusters:

-

(i)

Green cluster: composed of seven articles, in which the main highlight is Singh and El-Kassar’s (2019) “Role of big data analytics in developing sustainable capabilities”, published in the Journal of Cleaner Production. The main objective of this work was to examine the extent of sustainable capabilities driven by corporate commitment resulting from the integration of big data technologies, green supply chain management and green human resource management practices, and the extent to which these capabilities can improve the performance of the company as a whole. The results of this study show the influence of big data-driven strategies on business growth in terms of sustainable performance, considering the internal processes that constitute sustainable capabilities.

-

(ii)

Red cluster: formed by 17 articles, in which the work of Wilden et al. (2013), entitled “Dynamic Capabilities and Performance: Strategy, Structure and Environment”, is highlighted. This paper was published in Long Range Planning and its main objective was to assess, theoretically and empirically, whether the effects contingent on the organic organizational structure facilitate the impact of dynamic capabilities on organizational performance. The research evidenced the performance effects of the internal alignment between organizational structure and dynamic capabilities, and the external adjustment of dynamic capabilities with competitive intensity.

-

(iii)

Blue cluster: formed by 10 articles, the main highlight being the work by Moon (2010), entitled “Organizational Cultural Intelligence: Dynamic Capability Perspective”, published in Group and Organization Management. The main objective was to propose a nomological network for organizational cultural intelligence (CQ) models that sheds light on the role of organizational CQ and the underlying mechanism of the relationship between organizational CQ and organizational performance, as well as intermediate performance outcomes (international performance). The results showed that the organizational CQ approach attempts to provide a coherent framework that can integrate the conceptual theory of cultural intelligence at the micro level and build on the theoretical foundations of dynamic capability.

Fig. 5.

Network of bibliographically linked documents.

Source: Research data—estimated by Gephi® software

In all the clusters, the above authors had the highest estimated values for the betweenness centrality statistic (32.23, 10.47 and 8.11, respectively). They also shared the most references with two other authors in the network. The coupling analysis makes it possible to show, in a generalized way, the close theoretical relationship of the highlighted authors, with convergence in terms of citation of classic authors.

Word cluster analysis

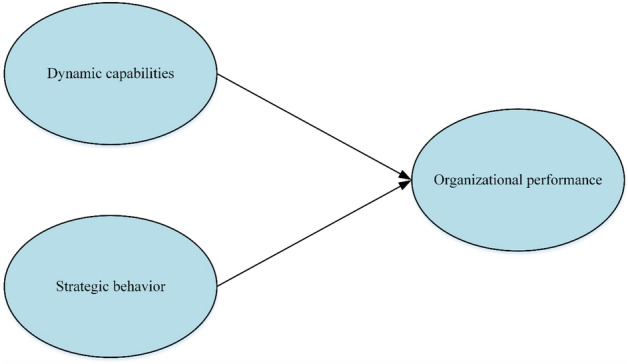

This section is intended to provide a detailed analysis of the keywords in the corpus, grouping them according to frequency of occurrence, to enable the identification of lexical content and centrality (Mendes et al. 2016). We used the method of Reinert (1990), reported as Descending Hierarchical Classification (DHC), to present the formulated classes grouped into classes considering the 118 article abstracts. Iramuteq software allows for different forms of analysis of the textual corpus, such as the classic lexical analysis through co-occurrences, as shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Grouping of highlighted words in the textual corpus.

Source: Research data

The formulation of the word groupings displayed in Fig. 6 considered the most frequent terms extracted from the abstracts. The terms described in their literal form contained in the search string (Organizational Performance, Dynamic Capability and Strategic Behavior) were excluded, since they would naturally be present in the formulation process. We considered the word incidence matrix, where the size of the terms and their centering in the word map is proportional to their occurrence.

To conduct this analysis, 660 text segments were evaluated, equivalent to 74.55% correctly classified extracts. The retention of text segments must be at least 70% for the DHC analysis to be adequate, therefore this analysis can be considered statistically representative (Camargo and Justo 2013). We show that 23,570 occurrences emerged, categorized as words or forms, with 1,871 words characterized as active forms. In addition, there were three classes containing the following compositions: Class 1, with 236 text segments (47.97%); Class 2, with 133 text segments (27.03%); Class 3, with 123 text segments (25.00%). The corpus content was subsequently analyzed, leading to the categorization of the three classes that were renamed from the content analysis technique.

To provide detail on the content of the classes contained in Fig. 6, we present the eight terms containing the highest probability values (p value) associated with the chi-square statistic. We set a minimum frequency of five occurrences and considered a critical value of the chi-square statistic as greater than 3.80 (χ2 > 3.80), so that the terms are statistically significant or, alternatively, a probability value lower than 5% (p value < 0.05). A p value < 0.05 refers to the level of significance adopted so that there is an association between words and classes, as recommended by Reinert (1990).

When analyzing the words contained in Class 1, “Knowledge Management”, the following are highlighted in descending order of frequency of occurrences and chi-square statistics: Knowledge, Resource, Ability, Relationships, Competency, Innovation, Opportunity, Creation. These terms are recurrent in other findings, as described by Moustaghfir (2008), Criado-García et al. (2020) and Arun and Ozmutl (2021). It can be clearly seen that the respective authors sought to apply the concept of dynamic capabilities linked to organizational competencies that, consequently, influence the processes, products and services necessary for rapid changes for the development of dynamic capabilities and improved performance. Tseng and Lee (2014) showed that dynamic capability is an important intermediary organizational mechanism through which knowledge capability benefits are converted into enterprise-level performance effects. In other words, knowledge capacity increases the dynamic capability of organizations, which, in turn, increases organizational performance and provides competitive advantages.

For the analysis of Class 2, “Measurement Instruments”, the following words are highlighted in descending order of frequency of occurrences and chi-square statistics: Equation, Hypothesis, Partial Least Square, Questionnaire, Respondent, Methodology, Regression, Correlation. Since 92.47% of the articles are characterized as quantitative, using data collection instruments such as structured questionnaires, it is to be expected that the overwhelming majority of articles used relational data analysis tools. We highlight the research conducted by Wilden et al. (2013), Zhou et al.(2019), Cake et al. (2020) and Lee et al. (2020). In all the quantitative studies evaluated here, several used methodologies to test theoretical hypotheses for principles that support the reduction of waste, increase of efficiency and maximization of organizational performance. For example, Hair Jr. et al. (2005) showed that the form of relational modeling, through the technique of structural equations, seeks to explain the interrelationships between variables from a series of multiple regression equations. These equations aim to describe the constructs which, in turn, are latent factors composed of multiple variables. In the analyzed articles, we noted, from the use of confirmatory models with theoretical support, the testing of hypotheses that sought to relate organizational dynamic capabilities with the alignment of processes and their organizational performance. For this purpose, moderator variables and their organizational performance were used in a complementary way, as mediators as well as the “multigroup” analysis technique, by incorporating sociodemographic characteristics or linked to managerial aspects.

Analogous to the previous class, in Class 3, “Organizational Environment”, the following terms can be highlighted: Practitioner, Exploitation, Exploration, University, Public, Organization, Strategy, Ecosystem. Greater occurrences of these terms occurred in Yang et al. (2016), Vogus and Rerup (2018), Napathorn (2021) and Widianto et al. (2021). In a generalized way, we perceived that the articles assess the development of skills of organizations in the institutional context by evaluating the relationships between the characteristics of the mental model of a given work team in making strategic decisions for organization performance. In this context, the set of terms selected have a strong connection with the effects of dynamic performance capabilities which, in turn, depend on the competitive intensity faced by companies. The organizational environment evidenced from the co-occurrences of the words in the corpus is justified based on variables related to public institutions, strategies adopted by companies and in the market, so that such organizations can expand or modify their processes.

Suggestions for future research

The results of this SLR lead to some suggestions for future research on the theme of dynamic capabilities, strategic behavior and organizational performance in different types of organizations. In particular, future research should: (i) empirically test the insertion of moderating or mediating variables, using structural equation models to assess their relationships with dynamic and substantive capabilities (Ali et al. 2012); (ii) investigate the effect of organizational capabilities, such as marketing, research and development, IT and supply chain capabilities on organizational performance (Yu et al. 2018); (iii) investigate how CEOs' personal beliefs influence the dynamic capabilities of companies in longitudinal terms, so that dynamic components and their individual characteristics can be captured (Von den Driesch et al. 2015); (iv) survey whether the effect of organizational learning moderates the relationship between strategic changes and organizational performance, in addition to empirically testing the effect of company size and industry type on organizational performance (Yi et al. 2015); (v) investigate the effects of COVID-19 on resilient organizations’ superior performance, from the perspective of strategic behavior (Eklund 2021).

Conclusion

This SLR contributes to a greater understanding of the interface between dynamic capability, strategic behavior and organizational performance in theoretical, methodological and empirical terms. In methodological terms, 25 of the articles, (21.19%) are qualitative studies and 93 (78.81%) are quantitative. Interest in the subject has grown over the time, with the highest number of published articles appearing in the last five years; 66.10% of the articles were published between 2017 and 2021 and the most productive year was 2020. Theoretically, there was an average of 33.69 citations per document, 5.27 citations per year per published document, 0.34 documents per author and 2.97 authors per published document. In empirical terms, among the quantitative metrics, structural equation modeling occurred in 65 works (69.89%), followed by regression analysis technique with 11 occurrences (11.83%).

The network formulation contains 34 authors coupled according to their bibliographic references, distributed over the three clusters of articles in the corpus, where each node represents one of these articles. Among the highest values of the betweenness centrality statistic, in the seven articles in the green cluster, prominent authors are Singh and El-Kassar (2019), of the 17 articles in the red cluster, the work of Wilden et al. (2013) is highlighted and in the 10 articles in the blue cluster, Moon (2010) is noteworthy.

Word analysis in terms of frequency of occurrence and chi-square statistics showed the following: Class 1 (“Knowledge Management”) contained Knowledge, Resource, Ability, Relationships, Competency, Innovation, Opportunity, Creation; Class 2 (“Measurement Instruments”) featured Equation, Hypothesis, Partial Least Square, Questionnaire, Respondent, Methodology, Regression, Correlation; Class 3 ("Organizational Environment") highlighted Practitioner, Exploitation, Exploration, University, Public, Organization, Strategy, Ecosystem.

As a general result, the relationship between the set of terms selected in the class has a strong connection with the effects of dynamic performance capabilities which, in turn, depend on the competitive intensity faced by companies. Furthermore, the organizational environment evidenced from the co-occurrences of the words in the corpus is justified based on variables related to public institutions, strategies adopted by companies and the market. In this respect, the data relatively confirm the fact that such organizations can expand or modify their processes by building and using dynamic capabilities as institutional factors as they seek to shape their behavior.

Both the theoretical framework and the results of bibliometrics point towards future research on the theme of dynamic capabilities, strategic behavior and organizational performance. Although this work presents a systematic and exhaustive review of the literature, there are some limitations, especially with regard to the selection of the textual corpus, which can be considered in future research: (i) the scientific production for analysis was limited to the Scopus and WoS databases; (ii) only articles published in English were considered; (iii) we only considered articles published in journals; (iv) “Accounting”, “Business”, “Management”, “Economics” and related fields were used as filters. Therefore, it is possible that relevant research has been published in other formats (e.g., books, book chapters, conference proceedings,), in different languages, in other databases or in other areas of knowledge.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the financial support and granting scholarship by the Research Support Foundation of the State of Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES). We also thank the Editor Neda Ghatrouei and anonymous reviewers for their contributions and recommendations. All comments were constructive, and we believe our revised manuscript was significantly improved by addressing the comments and suggestions.

Funding

Research Support Foundation of the State of Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest for the authors listed.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Henrique Faverzani Drago, Email: henrique_fd@yahoo.com.br.

Gilnei Luiz de Moura, Email: mr.gmoura.ufsm@gmail.com.

Luciana Santos Costa Vieira da Silva, Email: luvcosta10@gmail.com.

Claudimar Pereira da Veiga, Email: claudimar.veiga@gmail.com.

Fabíola Kaczam, Email: kaczamf@gmail.com.

Luciana Peixoto Santa Rita, Email: luciana.santarita@feac.ufal.br.

Wesley Vieira da Silva, Email: wesley.silva@feac.ufal.br.

References

- Abubakar AM, Elrehail H, Alatailat MA, Elçi A. Knowledge management, decision-making style and organizational performance. J Innov Knowl. 2019;4:104–114. doi: 10.1016/J.JIK.2017.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adewunmi YA, Iyagba R, Omirin M. Multi-sector framework for benchmarking in facilities management. Benchmarking. 2017;24:826–856. doi: 10.1108/BIJ-10-2015-0093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agrell PJ, Teusch J. Predictability and strategic behavior under frontier regulation. Energy Policy. 2020 doi: 10.1016/J.ENPOL.2019.111140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ansaari Y, Bederr H, Chen C. Strategic orientation and business performance: an empirical study in the UAE context. Manag Decis. 2015;53:2287–2302. doi: 10.1108/MD-01-2015-0034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S, Peters LD, Lettice F. An organizational learning perspective on conceptualizing dynamic and substantive capabilities. J Strateg Mark. 2012;20:589–607. doi: 10.1080/0965254X.2012.734845. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arun K, Ozmutlu SY (2021) Strategic orientation of service enterprises towards customers. In: Cobanoglu C, Della Corte V (eds) Advances in global services and retail management. USF M3 Publishing, pp 1–11

- Ball R. Awareness mentality and strategic behavior in science. Front Res Metrics Anal. 2021 doi: 10.3389/FRMA.2021.703159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett P, Lascar C (2012) Comparing Unique Title Coverage of Web of Science and Scopus in Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. Issues Sci Technol Librariansh. 10.29173/ISTL1558

- Bastian M, Heymann S, Jacomy M. Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. Proc Int AAAI Conf Web Soc Media. 2009;3:361–362. doi: 10.1609/ICWSM.V3I1.13937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behl A, Gaur J, Pereira V, et al. Role of big data analytics capabilities to improve sustainable competitive advantage of MSME service firms during COVID-19—a multi-theoretical approach. J Bus Res. 2022;148:378–389. doi: 10.1016/J.JBUSRES.2022.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behling G, Lenzi FC. Entrepreneurial competencies and strategic behavior: a study of micro entrepreneurs in an emerging country. Brazilian Bus Rev. 2019;16:255–272. doi: 10.15728/BBR.2019.16.3.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benitez JR, Damke EJ. Comportamento Estratégico e Desempenho Organizacional sob a Perspectiva de Miles e Snow: um Estudo em Pequenas Empresas do Setor Varejista de Farmácias do Paraná. Rev Livre Sustentabilidade e Empreendedorismo. 2016;1:118–133. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgili H, Johnson JL, Bilgili TV, Ellstrand AE. Research on social relationships and processes governing the behaviors of members of the corporate elite: a review and bibliometric analysis. Rev Manag Sci. 2022;16:2285–2339. doi: 10.1007/S11846-021-00505-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biolchini JC de A, Mian PG, Natali ACC, et al (2007) Scientific research ontology to support systematic review in software engineering. Adv Eng Inform 21:133–151. 10.1016/J.AEI.2006.11.006

- Bruner JS, Goodnow JJ, Austin GA. A study of thinking. 2. Routledge; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Burks SV, Carpenter JP, Goette L, Rustichini A. Cognitive skills affect economic preferences, strategic behavior, and job attachment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7745–7750. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.0812360106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cake DA, Agrawal V, Gresham G, et al. Strategic orientations, marketing capabilities and radical innovation launch success. J Bus Ind Mark. 2020;35:1527–1537. doi: 10.1108/JBIM-02-2019-0068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo BV, Justo AM. IRAMUTEQ: a free software for textual data analysis. Temas Em Psicol. 2013;21:513–518. doi: 10.9788/TP2013.2-16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Criado-García F, Calvo-Mora A, Martelo-Landroguez S. Knowledge management issues in the EFQM excellence model framework. Int J Qual Reliab Manag. 2020;37:781–800. doi: 10.1108/IJQRM-11-2018-0317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Araújo CCS, Pedron CD, Bitencourt C. Identifying and assessing the scales of dynamic capabilities: a systematic literature review. Rev Gest. 2018;25:390–412. doi: 10.1108/REGE-12-2017-0021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza MAR, Wall ML, Thuler ACDMC, et al. The use of IRAMUTEQ software for data analysis in qualitative research. Rev Da Esc Enferm. 2018 doi: 10.1590/S1980-220X2017015003353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt KM, Martin JA. Dynamic capabilities: what are they? Strateg Manag J Strat Mgmt J. 2000;21:1105–1121. doi: 10.1002/1097-0266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund MA. The COVID-19 lessons learned for business and governance. SN Bus Econ. 2021 doi: 10.1007/S43546-020-00029-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio CM, Kaczam F, de Moura GL, et al. Competitive advantage and dynamic capability in small and medium-sized enterprises: a systematic literature review and future research directions. Rev Manag Sci. 2022;16:617–648. doi: 10.1007/S11846-021-00459-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fruchterman TMJ, Reingold EM. Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Softw Pract Exp. 1991;21:1129–1164. doi: 10.1002/SPE.4380211102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Blackmore K. Characterisation of academic journals in the digital age. Scientometrics. 2017;110:1333–1350. doi: 10.1007/S11192-016-2219-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guido G, Ugolini MM, Sestino A. Active ageing of elderly consumers: insights and opportunities for future business strategies. SN Bus Econ. 2022 doi: 10.1007/S43546-021-00180-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guleria D, Kaur G. Bibliometric analysis of ecopreneurship using VOSviewer and RStudio Bibliometrix, 1989–2019. Libr Hi Tech. 2021;39:1001–1024. doi: 10.1108/LHT-09-2020-0218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hair Jr. JF, Babin B, Money A, Samouel P (2005) Fundamentos de Métodos de Pesquisa em Administração. Bookman, Porto Alegre, RS

- Henri JF. Management control systems and strategy: a resource-based perspective. Accounting, Organ Soc. 2006;31:529–558. doi: 10.1016/J.AOS.2005.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M, Hughes P, Morgan RE, et al. Strategic entrepreneurship behaviour and the innovation ambidexterity of young technology-based firms in incubators. Int Small Bus J Res Entrep. 2021;39:202–227. doi: 10.1177/0266242620943776. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein WH, Hafedh AA. Reflection of strategic behaviors in scenario planning. Int J Res Soc Sci Humanit. 2020;10:141–144. doi: 10.3764/IJRSSH.V10I04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczam F, Siluk JCM, Guimaraes GE, et al. Establishment of a typology for startups 4.0. Rev Manag Sci. 2022;16:649–680. doi: 10.1007/S11846-021-00463-Y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kellner A, Townsend K, Wilkinson A, et al. The message and the messenger: Identifying and communicating a high performance “HRM philosophy”. Pers Rev. 2016;45:1240–1258. doi: 10.1108/PR-02-2015-0049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler MM. Bibliographic coupling between scientific papers. Am Doc. 1963;14:10–25. doi: 10.1002/ASI.5090140103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khanin D, Turel O, Bart C, et al. The possible pitfalls of boards’ engagement in the strategic management process. Rev Manag Sci. 2021;15:1071–1093. doi: 10.1007/S11846-020-00386-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchenham B (2004) Procedures for performing systematic reviews. Jt Tech Report, Comput Sci Dep Keele Univ Natl ICT Aust Ltd ( 0400011T1)

- Klewitz J, Hansen EG. Sustainability-oriented innovation of SMEs: a systematic review. J Clean Prod. 2014;65:57–75. doi: 10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2013.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthi S, Mathew SK. Business analytics and business value: a comparative case study. Inf Manag. 2018;55:643–666. doi: 10.1016/J.IM.2018.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laaksonen O, Peltoniemi M. The essence of dynamic capabilities and their measurement. Int J Manag Rev. 2018;20:184–205. doi: 10.1111/IJMR.12122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Choi B. Knowledge management enablers, processes, and organizational performance: an integrative view and empirical examination. J Manag Inf Syst. 2003;20:179–228. doi: 10.1080/07421222.2003.11045756. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ZY, Chu MT, Wang YT, Chen KJ. Industry performance appraisal using improved MCDM for next generation of Taiwan. Sustain. 2020 doi: 10.3390/SU12135290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Londoño-Patiño JA, Acevedo-Álvarez CA (2018) El aprendizaje organizacional (AO) y el desempeño empresarial bajo el enfoque de las capacidades dinámicas de aprendizaje. Rev CEA 4:103–118. 10.22430/24223182.762

- Martín-de Castro G. Knowledge management and innovation in knowledge-based and high-tech industrial markets: the role of openness and absorptive capacity. Ind Mark Manag. 2015;47:143–146. doi: 10.1016/J.INDMARMAN.2015.02.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marzall LF, Kaczam F, Costa VMF, et al. Establishing a typology for productive intelligence: a systematic literature mapping. Manag Rev Q. 2022;72:789–822. doi: 10.1007/S11301-021-00214-Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masa’deh R, Al-Henzab J, Tarhini A, Obeidat BY (2018) The associations among market orientation, technology orientation, entrepreneurial orientation and organizational performance. Benchmarking 25:3117–3142. 10.1108/BIJ-02-2017-0024

- Medeiros SA, Magalhães Christino JM, Gonçalves CA, Gonçalves MA. Relationships among dynamic capabilities dimensions in building competitive advantage: a conceptual model. Gest e Prod. 2020 doi: 10.1590/0104-530X3680-20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt R, Junge S, Weiss M. The organizational environment with its measures, antecedents, and consequences: a review and research agenda. Manag Rev Q. 2018;68:195–235. doi: 10.1007/S11301-018-0137-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes FRP, Zangão MOB, Gemito MLGP, Serra I da CC (2016) Social representations of nursing students about hospital assistance and primary health care. Rev Bras Enferm 69:343–350. 10.1590/0034-7167.2016690218I [DOI] [PubMed]

- Michaelis B, Rogbeer S, Schweizer L, Özleblebici Z. Clarifying the boundary conditions of value creation within dynamic capabilities framework: a grafting approach. Rev Manag Sci. 2021;15:1797–1820. doi: 10.1007/S11846-020-00403-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miles RE, Snow CC, Meyer AD, Coleman HJ. Organizational strategy, structure, and process. Acad Manage Rev. 1978;3:546–562. doi: 10.5465/AMR.1978.4305755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg H. The strategy concept I: five ps for strategy. Calif Manage Rev. 1987;30:11–24. doi: 10.2307/41165263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moon T. Organizational cultural intelligence: dynamic capability perspective. Gr Organ Manag. 2010;35:456–493. doi: 10.1177/1059601110378295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moustaghfir K. The dynamics of knowledge assets and their link with firm performance. Meas Bus Excell. 2008;12:10–24. doi: 10.1108/13683040810881162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Napathorn C. The development of green skills across firms in the institutional context of Thailand. Asia-Pacific J Bus Adm. 2021 doi: 10.1108/APJBA-10-2020-0370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MEJ. Modularity and community structure in networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8577–8582. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.0601602103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitzl C, Sicilia MF, Steccolini I. Exploring the links between different performance information uses, NPM cultural orientation, and organizational performance in the public sector. Public Manag Rev. 2019;21:686–710. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2018.1508609. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okhovati M, Sharifpoor E, Aazami M, et al. Novice and experienced users’ search performance and satisfaction with Web of Science and Scopus. J Librariansh Inf Sci. 2017;49:359–367. doi: 10.1177/0961000616656234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Owais L, Kiss JT (2020) The Effects Of Using Performance Measurement Systems (PMSS) On Organizations’ Performance. CrossCultural Manag J 111–121

- Pekovic S, Vogt S. The fit between corporate social responsibility and corporate governance: the impact on a firm’s financial performance. Rev Manag Sci. 2021;15:1095–1125. doi: 10.1007/S11846-020-00389-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piantadosi ST. Zipf’s word frequency law in natural language: a critical review and future directions. Psychon Bull Rev. 2014;21:1112–1130. doi: 10.3758/S13423-014-0585-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prell C (2012) Social network analysis: history, theory and methodology. Los Angeles/London: SAGE

- Rehman S, Mohamed R, Ayoup H. The mediating role of organizational capabilities between organizational performance and its determinants. J Glob Entrep Res. 2019 doi: 10.1186/S40497-019-0155-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reinert M. Alceste une méthodologie d’analyse des données textuelles et une application: Aurelia De Gerard De Nerval. Bull Sociol Methodol Méthodologie Sociol. 1990;26:24–54. doi: 10.1177/075910639002600103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ringov D. Dynamic capabilities and firm performance. Long Range Plann. 2017;50:653–664. doi: 10.1016/J.LRP.2017.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Lora V, Henao-Cálad M, Valencia Arias A. Taxonomías de técnicas y herramientas para la Ingeniería del Conocimiento: Guía para el desarrollo de proyectos de conocimiento. Ingeniare. 2016;24:351–360. doi: 10.4067/S0718-33052016000200016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rojon C, Okupe A, McDowall A. Utilization and development of systematic reviews in management research: What do we know and where do we go from here? Int J Manag Rev. 2021;23:191–223. doi: 10.1111/IJMR.12245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwens C, Wagner M. The role of firm-internal corporate environmental standards for organizational performance. J Bus Econ. 2019;89:823–843. doi: 10.1007/S11573-018-0925-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SCIMAGO (2019) SJR : Scientific Journal Rankings. https://www.scimagojr.com/journalrank.php. Accessed 6 Jul 2019

- Shams SMR, Belyaeva Z (2018) Dynamic capabilities, strategic management and competitive advantage: a debate and research trend. In: Vrontis D, Weber Y, Tsoukatos E (eds) 11th Annual Conference of the EuroMed-Academy-of-Business-Research Advancements in National and Global Business Theory and Practice. EuroMed Press, pp 1724–1727

- Silveira-Martins E, Basso MO, Mascarenhas LE. Strategic behavior and performance: a study applied in industries wineries Portugal. Rev Eletrônica Fafit/facic. 2014;5:22–40. [Google Scholar]

- Singh SK, El-Kassar AN. Role of big data analytics in developing sustainable capabilities. J Clean Prod. 2019;213:1264–1273. doi: 10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2018.12.199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Staszkiewicz P, Szelągowska A. Ultimate owner and risk of company performance. Econ Res Istraz. 2019;32:3795–3812. doi: 10.1080/1331677X.2019.1678499. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Svobodová Z, Rajchlová J. Strategic behavior of e-commerce businesses in online industry of electronics from a customer perspective. Adm Sci. 2020 doi: 10.3390/ADMSCI10040078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teece DJ. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg Manag J. 2007;28:1319–1350. doi: 10.1002/SMJ.640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teece DJ. Achieving integration of the business school curriculum using the dynamic capabilities framework. J Manag Dev. 2011;30:499–518. doi: 10.1108/02621711111133019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teece DJ, Pisano G, Shuen A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg Manag J. 1997;18:509–533. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tranfield D, Denyer D, Smart P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br J Manag. 2003;14:207–222. doi: 10.1111/1467-8551.00375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai HT, Tsai CL. The influence of the five cardinal values of confucianism on firm performance. Rev Manag Sci. 2022;16:429–458. doi: 10.1007/S11846-021-00452-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng SM, Lee PS. The effect of knowledge management capability and dynamic capability on organizational performance. J Enterp Inf Manag. 2014;27:158–179. doi: 10.1108/JEIM-05-2012-0025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villafuerte-Godínez RÁ, Leiva JC. Cómo surge y se vincula el conocimiento relacionado con el desempeño en las Pymes: un análisis cualitativo. Rev CEA. 2015;1:37. doi: 10.22430/24223182.123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vivas-López S. Implicaciones de las capacidades dinámicas para la competitividad y la innovación en el siglo xxi. Cuad Adm. 2013;26:119–139. [Google Scholar]

- Vodovoz E, May MR. Innovation in the business model from the perspective of dynamic capabilities: Bematech’s case. Rev Adm Mackenzie. 2017;18:71–95. doi: 10.1590/1678-69712017/ADMINISTRACAO.V18N6P71-95. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogus TJ, Rerup C. Sweating the “small stuff”: High-reliability organizing as a foundation for sustained superior performance. Strateg Organ. 2018;16:227–238. doi: 10.1177/1476127017739535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- von den Driesch T, da Costa MES, Flatten TC, Brettel M. How CEO experience, personality, and network affect firms’ dynamic capabilities. Eur Manag J. 2015;33:245–256. doi: 10.1016/J.EMJ.2015.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss L, Kanbach DK. Toward an integrated framework of corporate venturing for organizational ambidexterity as a dynamic capability. Manag Rev Q. 2021 doi: 10.1007/S11301-021-00223-Y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Widianto S, Lestari YD, Adna BE, et al. Dynamic managerial capabilities, organisational capacity for change and organisational performance: the moderating effect of attitude towards change in a public service organisation. J Organ Eff. 2021;8:149–172. doi: 10.1108/JOEPP-02-2020-0028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilden R, Gudergan SP, Nielsen BB, Lings I. Dynamic capabilities and performance: strategy, structure and environment. Long Range Plann. 2013;46:72–96. doi: 10.1016/J.LRP.2012.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wood S, Ogbonnaya C. High-involvement management, economic recession, well-being, and organizational performance. J Manage. 2018;44:3070–3095. doi: 10.1177/0149206316659111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Narayanan VK, Baburaj Y, Swaminathan S. Team mental model characteristics and performance in a simulation experiment. Manag Res Rev. 2016;39:899–924. doi: 10.1108/MRR-02-2015-0036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yi Y, He X, Ndofor H, Wei Z. Dynamic capabilities and the speed of strategic change: evidence from China. IEEE Trans Eng Manag. 2015;62:18–28. doi: 10.1109/TEM.2014.2365524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yin M, Hughes M, Hu Q. Entrepreneurial orientation and new venture resource acquisition: why context matters. Asia Pacific J Manag. 2021;38:1369–1398. doi: 10.1007/S10490-020-09718-W. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, Ramanathan R, Wang X, Yang J. Operations capability, productivity and business performance the moderating effect of environmental dynamism. Ind Manag Data Syst. 2018;118:126–143. doi: 10.1108/IMDS-02-2017-0064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zea-Fernández RD, Benjumea-Arias ML, Valencia-Arias A. Methodology for the identification of dynamic capacities for entrepreneurship in higher education institutions. Ingeniare. 2020;28:106–119. doi: 10.4067/S0718-33052020000100106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zehir C, Yıldız H, Köle M, Başar D. Superior organizational performance through SHRM implications, mediating effect of management capability: an implementation on islamic banking. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2016;235:807–816. doi: 10.1016/J.SBSPRO.2016.11.089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Morris JL. High-performance work systems and organizational performance: testing the mediation role of employee outcomes using evidence from PR China. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2014;25:68–90. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2013.781524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D, Strotmann A. Evolution of research activities and intellectual influences in information science 1996–2005: introducing author bibliographic-coupling analysis. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2008;59:2070–2086. doi: 10.1002/ASI.20910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K, Huang HH, Wu WS. Shareholding structure, private benefit of control and incentive intensity: from the perspective of enterprise strategic behaviour. Econ Res Istraz. 2021;34:856–879. doi: 10.1080/1331677X.2020.1805345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SS, Zhou AJ, Feng J, Jiang S. Dynamic capabilities and organizational performance: the mediating role of innovation. J Manag Organ. 2019;25:731–747. doi: 10.1017/JMO.2017.20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.