Abstract

Following COVID-19, the global educational landscape shifted dramatically. Almost every educational institute in Bangladesh undertook a strategic move to begin offering online or blended learning courses to mitigate the challenges created by the pandemic. The TVET sector, particularly the polytechnic institute of Bangladesh, endeavored to explore the blended learning approach as an immediate and long-term solution to address the educational dislocation caused by the pandemic. This study attempts to conceptualize a pedagogical design based on the ADDIE and rapid prototyping model to make a reliable and robust instructional design to be used in the blended learning context. A content validity index (CVI) was used to validate the proposed model; a technology acceptance model (TAM) was employed to examine its acceptability to students; and finally, students’ academic performances were analysed to evaluate the overall performance of the proposed instructional design. The findings reveal that the proposed instructional design can be a reliable and valid pedagogical approach to be implemented in the blended learning context for polytechnic students. The proposed instructional design may help TVET educators and course designers to create a robust blended learning environment in the TVET sector and in other similar disciplines, such as science and engineering education.

Keywords: Instructional design, Blended learning, Polytechnic institutes, ADDIE and RAPID prototyping, TVET, Bangladesh

Introduction

The delivery of learning is rapidly evolving with the advent of modern technologies. Researchers are continually exploring different ways and methods to create effective online environments for students (Al Mamun et al., 2020; Al Mamun, Hossain, et al., 2022; Lawrie et al., 2016). The recent outburst of COVID-19 further accelerated the adaptation of online learning among educators to address the immediate educational challenges caused by the pandemic. In response, the technical and vocational education and training (TVET) sector in Bangladesh is trying to meet these educational challenges by shifting the course delivery from face-to-face to distance learning mode. However, the report suggests that, in general, the educational institutions of Bangladesh and, in particular, the TVET course designers are facing multifaceted problems in shifting traditional learning to the online environment (Uzzaman et al., 2020). For example, weaknesses are prevalent in the following areas: infrastructure, a lack of modern technologies and low internet speed (Al-Amin et al., 2021), poor preparation of teacher training in pedagogical knowledge and technology use (Rony & Awal, 2019), of teachers awareness of the potential use of technology and poor technical competency (Saidu & Al Mamun, 2022), and student readiness and motivation towards online learning (Al Mamun, Hossain, et al., 2022; Jahan et al., 2021), etc. are key factors obstructing the effective implementation of online education in Bangladesh.

Educators and course designers of the polytechnic institutes of Bangladesh are facing even more difficulties in implementing the online learning environment as research has shown that it was far more difficult for technical subjects to be delivered online as some of the topics require hands-on activities and special training to master the skills (Kamal, 2020). In addition, students studying in the polytechnic institutes of Bangladesh usually have low socioeconomic status (Khan, 2019) and, thus, lack modern digital devices and high-speed internet connections in their households (Das, 2021). Also, effective and immediate personal feedback, which is readily available in face-to-face classroom situations, cannot be offered in the online mode effectively. Despite decades of research, online learning lacks the development of such a pedagogical method that integrates a quick and effective feedback mechanism system within the online learning environment (Li et al., 2019). Nonetheless, several research studies have attempted to provide synchronous feedback to students in online and self-regulated learning environments (Al Mamun, 2018; Al Mamun et al., 2020; Al Mamun et al., 2022; Timonen & Ruokamo 2021). However, other studies show that fully online learning delivery may have an unsatisfactory impact on academic achievement due to the absence of direct teacher supervision (Adedoyin & Soykan, 2020). Thus, standalone online learning may not fully meet students’ learning needs.

Previous research argues that blended learning (BL) can improve educational approaches to support effective student learning (Kang & Seomun, 2018). Blended learning is a pedagogical approach that offers students experience in both face-to-face and online educational learning modes. This approach allows students to learn anytime, anywhere, and can potentially minimize all the drawbacks of online and traditional learning systems coherently (Carman, 2002). The blended classrooms encourage more active classroom learning by promoting self-confidence and academic success by increasing students’ behavioral, emotional, and intellectual participation in the learning process (Wang et al., 2009). For example, the flipped classroom, which is a popular form of BL, engages students more actively in solving complicated tasks and helps students to develop higher-order thinking skills in different disciplines such as engineering and medical science (Al Mamun, Azad, et al., 2022; M. K. Lee, 2018; Tang et al., 2022). Thus, the BL approach can offer a practical solution to the polytechnic institutes of Bangladesh in minimizing the educational challenges caused by the pandemic.

Although several studies used the ADDIE model and rapid prototyping individually to create online instructional designs (Dong, 2021) and blended learning modules (Chen, 2016; Islam et al., 2022; Stapa & Mohammad, 2019), the combination of the two to develop instructional designs for the blended learning environments is non-existent. Particularly in the Bangladesh TEVT context, there is a dearth of research that may give educators a thorough guideline for creating a BL environment that is both rigorous and time-efficient. Thus, this study endeavors to address this gap and develops a BL framework for the TVET educators and course designers to implement in the polytechnic institutes of Bangladesh. The following research questions were posed to meet this end:

RQ1: Is the proposed instructional design reliable and valid for the BL environment of the polytechnic institutes of Bangladesh?

RQ2: To what extent do the polytechnic students of Bangladesh accept the proposed instructional design?

RQ3: Is the proposed instructional design effective in improving students’ academic performances?

Blended learning: the context of polytechnic institutes in Bangladesh

Blended learning is defined as the coexistence of face-to-face and online learning, where a significant portion of the content is delivered online (Means et al., 2013; Marsh & Drexler, 2001) explained BL as a self-paced but teacher-led, online, and face-to-face classroom delivery system to achieve a flexible and cost-effective education to cater to individual learning approaches. BL combines several modes of instruction, i.e., live online classrooms, face-to-face classrooms, and self-paced learning (Singh, 2003). A designer can create a course from scratch or add extra online activities to a traditional learning setup in this method of learning (Alammary et al., 2014). The effectiveness of BL depends on its design approach, such as how the course is structurally organized and how every aspect of the learning objectives is aligned with the delivery method. The instructors can integrate various instructional components, e.g., lectures, discussions, and different synchronous and asynchronous learning activities, to deliver an effective learning environment.

Though online learning is not a new concept in Bangladesh, there is little or no research available that offers a comprehensive BL environment in the context of technical and vocational education and training (TVET), especially for polytechnic students. In fact, designing a suitable BL environment is found to be a complicated task in the TVET context of Bangladesh (Raihan & Han, 2013). Several studies identified key factors that hinder the effective implementation of educational technology in the polytechnic institutes of Bangladesh (Al Mamun, 2012; Al Mamun & Tapan, 2009; M. S. H. Khan et al., 2012). For example, Hossain & Ahmed (2013) reported that due to a shortage of trained resource personnel and the absence of a positive mindset toward technology, the intensity of technology use in educational institutions is fragile and backdated. According to research, the use of technology in the polytechnic institutions of Bangladesh has been limited due to a lack of pedagogical knowledge, technological incompetency, shortage of training, and the absence of modern technology (Al Mamun, 2012). Often instructors fail to integrate technology into their lessons as a result of a huge teaching load (Chowdhury, 2018). Thus, teachers have been unable to find the necessary time to redesign the course components in light of technological advancements (Mndzebele, 2013). Moreover, polytechnic institutes of Bangladesh often struggle with inadequate financial support for developing the ICT infrastructure, which results in insufficient computers, labs, libraries, and modern classroom facilities (Raihan & Shamim, 2008). Thus, these issues have become the key impediments for policymakers and educators in developing and implementing an effective BL environment for the polytechnic institutes of Bangladesh.

Technical and vocational education and training (TVET) curricula, specifically at the polytechnic level, are often meant to educate learners for direct entrance into a specific career or trade. Curriculum and instructional designers for online learning need to ensure that polytechnic students will have the same opportunity to achieve those sets of skills and training as they might in the traditional learning environment. However, creating an online environment as per the requirements of the TVET qualification framework while offering carefully designed tasks and activities to develop the desired skill sets in that mode is a formidable task. Though the concept of BL is exciting for some, it is still a daunting task to implement. Nonetheless, the pandemic has compelled polytechnic institutes of Bangladesh to search for a quick, immediate solution to continue the education provisions without any interruption.

This study attempts to customize the popular analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation (ADDIE) model to build an instructional prototype in the BL environment. As ADDIE has its limitations, e.g., it requires adequate funding and a longer timeframe to implement, this study integrates the concept of rapid prototyping (RP) with the ADDIE approach to design an instructional design for the BL environment (Dong, 2021). However, RP has its drawbacks too. It has a propensity to promote informal design that is not fully formed. Thus, a potential design might be adopted uncritically in the hands of irresponsible or harried designers. Therefore, to achieve a plausible, functional instructional design, this study integrates the concept of ADDIE with rapid prototyping (RP). This approach potentially cancels out the shortcomings of each model.

Review of ADDIE and RAPID prototyping model

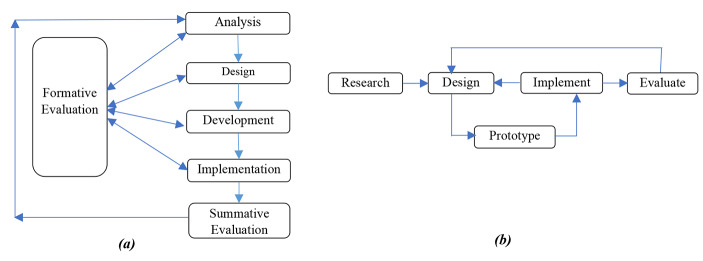

The ADDIE model has become influential since its inception at Florida State University in 1975 (Branson et al., 1975). It is an iterative instructional design method in which the instructional designer may return to any previous step based on the formative evaluation undertaken during the process (Aldoobie, 2015; Kulvietiene & Sileikiene, 2006). This process-based model enables instructional designers, content developers, and even teachers to produce efficient and effective teaching practices. The ADDIE model consists of five phases: analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation (see Fig. 1a). In this approach, the result of one phase serves as the starting point for the next one (Aldoobie, 2015).

Fig. 1.

Instructional design of (a) ADDIE model adapted from Kulvietiene & Sileikiene (2006), and (b) Rapid Prototyping (RP) adapted from Meier and Miller (2016)

The analysis phase in the ADDIE model defines, identifies, and determines the feasible solutions to a problem (Kulvietiene & Sileikiene, 2006). The design phase is primarily concerned with implementing the directives that the designer received from the analysis phase. Additionally, throughout the design phase, the instructional designer concentrates on choosing a course format and designing an appropriate instructional approach and assessment technique for the subject (Aldoobie, 2015). Based on the design phase, the development phase aggregates all the separate pieces to create a complete working prototype ready for implementation. Often, instructional designers argue that the components envisioned in the design phase must “come to life” in the development phase (Onguko et al., 2013). The implementation phase is concerned with transacting a plan; it entails three primary steps: training, preparing learners, and structuring the learning environment. Evaluation is the final step of the ADDIE model. The evaluation phase checks each step of the instructional design to ensure that they are aligned with the program’s intended goals. Two types of evaluation need to be undertaken in the ADDIE model. The first one is a formative evaluation, which can be undertaken after completing each phase. The second one is the summative evaluation which assesses the actual value of the whole instructional design at the end of the program.

However, the ADDIE approach has a few downsides to creating a quick and effective instructional design. An inherent problem with the ADDIE methodology is that each step is a resource-intensive procedure, requires a longer time for content design and development, and is sometimes expensive (Dong, 2021). Attempting to adhere to all phases of ADDIE during a pandemic is a difficult task for teachers who want a quick instructional design for the effective delivery of the courses.

In contrast, rapid prototyping (RP) requires less design time, faster implementation, less cost, and the benefits of more frequent evaluations over the ADDIE approach (Jones & Richey, 2000). Researching is the first stage of the RP model, which is similar to the ADDIE model’s analysis phase (Dong, 2021). In the second stage, designers experiment with the system, identify potential problems, and contribute to selecting a suitable interface for designing the online environment (Miller, 2008) through regular assessments and evidence-based design adjustments (Meier & Miller, 2018). Additionally, Dick et al., (2009) suggest that RP can be implemented through concurrent design and development, which means that most of the analysis work is done concurrently with the production of the initial draft of the design materials. Thus, RP techniques usually minimize production time because they (a) reduce the implementation time by utilizing the working prototypes as the final product and (b) offer continuous modification of the working prototypes. Finally, the summative and formative evaluation of the prototype is undertaken to ensure the viability of the model.

Instructional design with ADDIE model and RAPID prototyping

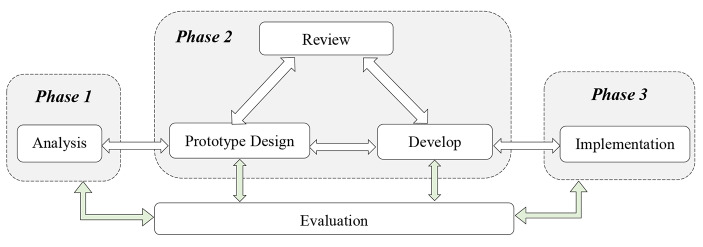

In the middle of a pandemic, a course designer needs the quick development of a trustworthy and robust model. Thus, combining ADDIE with rapid prototyping may be used to develop a personalized instructional design that can be communicated, implemented, measured, evaluated, and modified to fine-tune the model for the BL context. In this study, to reduce the design time and make a robust prototype, some features of the RP approach have been integrated with the ADDIE approach. In this process, the review phase has been introduced between the design and development phases of the prototype (Fig. 2). It offers a continuous review process that will accentuate the pace of development for the prototype design and development. Thus, the design and development of this prototype occur concurrently (Dong, 2021). The following is the modified version of an instructional design prototype based on the ADDIE and RP approaches.

Fig. 2.

Proposed instructional design and development process for the blended learning context

In the first phase, designers are engaged with the analysis process to determine the course objectives, contents, instructional strategy, and learners’ background to formulate the conceptual structure of the instructional strategy. The designer must be aware of the types of virtual and social settings that are necessary to assist students in achieving their learning objectives. There is widespread agreement that the most effective techniques for course design begin with a precise definition of course objectives before developing course activities, assignments, and evaluations (McGee & Reis, 2012). Course objectives are especially crucial for blended courses since they may guide material development, mode of delivery (face-to-face class or online), and developing related instructional strategies.

In the second phase, designing the instructional prototype and its development takes place. In designing the prototype, three key design components are considered, i.e., the learning activities, assessment procedures, and instructional design. The learning activities and elements of instructional strategies are identified, and the criteria for assessing and evaluating students’ performance are formulated to begin the prototype design. In designing the prototype, the designers and students review the design elements continually. This is a concurrent process where the designer is allowed to work parallel with many design segments while the end-user (students) reviews the prototype that has been forwarded to them.

The next step is to develop the instructional prototype in the second phase. The development of the prototype consists of creating learning materials, tutorials, and student activities. Class activities, assessments, assignments, lectures, discussion forums, etc., must be already prepared at this stage. In this stage, the designer must deal with the steps to deliver instructions to the user. The concept of rapid prototyping has been employed in the design and development phase. That means students will have the opportunity to review the prototype even before it is completed. After developing each segment of the prototype, it was forwarded to the reviewer and the students for their views and suggestions. In fact, the opportunity to engage the students in the RP approach significantly improves the evaluation of prototypes alongside the reviewers’ feedback and can be readily used to update the instructional design (Jones & Richey, 2000).

The final phase is the implementation stage, where the plan is converted to action. This phase involves three significant tasks, e.g., training the tutor, making students ready, and structuring and deploying the learning environment. In this phase, the course designer must incorporate training sessions to use all the tools integrated into the prototype. The teacher needs to make sure the learners are well-trained to use the prototype and that the learning environment is well-structured and user-friendly. Poon (2013) suggests integrating weekly discussions, teacher feedback, practice sessions, face-to-face meetings, etc., into the course delivery to ensure the quality of learning. Students are found to be motivated to engage with the activities and be responsible for the learning when such activities are integrated within the learning environment (McGee & Reis, 2012). It is to be noted that the students, reviewers, and even the other fellow designers can continually evaluate the prototype and give feedback on the course contents.

Implementation of the proposed model in the BL context

The proposed model was used to prepare a BL environment for a diploma engineering course titled 67,911: Internal Combustion (IC) Engine Principal, which is offered in the first semester of the Diploma in Marine Technology program. The details of the course curriculum and the required learning materials are available on the website of the Bangladesh Technical Education Board (BTEB) (BTEB, 2016). The BTEB designed the curriculum for face-to-face delivery. The current study restructured the course curriculum in such a way that forty-five per cent (45%) of the content was delivered online and 55% through the face-to-face classroom. For the online part of the course delivery, Google classroom was used. Google Classroom is a freely available learning management system for anyone with a Google account. Google classroom is found to be a simple student-friendly platform for delivering and managing online classrooms (Saidu & Al Mamun, 2022). However, Google classroom does not have any group discussion feature; thus, a separate online discussion forum, i.e., a Facebook group, was created for this class. Table 1 shows the implementation of the proposed model in the BL context.

Table 1.

Implementation of the proposed model in the BL context

| Phases | Tasks | Design Input | Design Output | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online (45% course) | Face-to-face (55% course) | |||

| Analysis | Goal Analysis |

What are the learning objectives? What are the expected learning outcomes? |

The learning objectives and the expected learning outcomes are defined in the BTEB curriculum used for designing the BL course materials (BTEB, 2016). | The learning objectives and the expected learning outcomes defined in the BTEB curriculum are used for designing the face-to-face course materials (BTEB, 2016). |

| Content Analysis |

Does the course content align with educational objectives? Does the instructional material consistent with learning outcomes? |

Learning objectives focus on more factual and conceptual knowledge, Less challenging content, unequivocal and unidirectional learning contents |

Learning objectives focus on more procedural and meta-cognitive knowledge, More challenging content, equivocal and multidirectional learning contents |

|

| Instructional Strategy Analysis | What types of virtual and social settings are necessary to assist students in achieving these objectives? |

The online classroom (Google meet/ Zoom) Online chat room Online discussion group |

Traditional classroom Group discussion Labs/ hands-on |

|

| Learner Analysis | What attitudes, abilities, and prior knowledge are required of students? | Assessing students’ attitudes through the technology acceptance model | Early assessment of prior knowledge | |

| Analysis of Assessment Techniques |

What abilities should the learner gain after the completion of instruction? How can we know if pupils have met these objectives? |

Test/ Quizzes Feedback Summative/ formative assessments |

||

| Design | Learning Activity Design | What should be the learning activities? | Classroom activities/ exercises/ group discussions | |

| Assessment Design |

How to assess the student’s performance? What should be the evaluating criteria? |

Quiz/ Assignments Test/Activities Projects/ Presentations |

||

| Instructional Strategy Design | What strategies to follow for creating the instructional design? | Lectures, discussions, reading activities, online chat room, online discussion group | Lectures, discussions, hands-on practices, labs | |

| Development |

Material Development Developing tutorials/ activities |

How to give overall direction to the classroom? How to align learning objectives with learning outcomes? |

Online announcements, Worksheets, video clips, images, PowerPoint slides and recorded lectures |

Lecture notes, activity development, workbooks |

| Implementation |

Training the instructor Preparing the learner Organizing the learning environment |

How to train the students and teachers? How to coordinate the learner’s space? |

Video tutorials, workshops, and seminars | Workshops and seminars |

| Evaluation | Feedback |

How to survey the data? How to interpret test results? |

Review and feedback through opinion forms and survey instrument | |

Methods

Context and participants

The proposed instructional design was implemented with the IC Engine Principle course offered in the first year at the two TVET institutions of Bangladesh, i.e., Faridpur and Munshiganj institutes of marine technology. There were three groups of participants (Table 2) whose reviews and opinions were elicited at different levels to validate the instructional design and examine its acceptance and usability.

Table 2.

Participants and types of validation

| Validation types | Validation time | Validation Instrument | N | Role | Expertise domain | Relevant experiences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content Validation | Continuous | Reflective journal opinion form | 4 |

Instructors = 2 Students = 2 |

Mechanical engineering | 2 years |

| Content Validation | End of each lesson | Content Validation Index (CVI) | 6 | Faculty | Engineering/ Educational technology | 5 Years |

| Acceptance and usability | End of the course | Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) | 81 | Students |

Throughout the design and development phase, one instructor and one student from each of the polytechnic institutes were involved in reviewing and giving their feedback on the contents employed by the proposed instructional design prototype (Table 2). A reflective journal form was used to obtain feedback from both the instructors and students. Their reviews were considered highly important for further rectification of the course designs. Further, to validate the content, six experts were asked to provide their opinion on the course contents. Their specialization was mechanical, electrical, and computer science engineering, with the research, focus on educational technology. They all have about 5 years of experience doing research related to teaching-learning in an online context. Finally, 81 students who participated in the IC Engine Principle course voluntarily gave their opinions through a survey questionnaire. The survey was designed based on the technology acceptance model (TAM) to examine the acceptance and usability of the proposed instructional design.

Model validation, acceptance, and effectiveness

Effective instructional design has three key phases –development, validation, and usability (J. Lee et al., 2017). The details of the instructional design and development phases have been discussed in the above sections with supporting theoretical and background information (see Sects. 2, 3, and 4). The following sections discuss the methodology of model validation, acceptance, and usability, i.e., model effectiveness.

Validation of the contents

To answer RQ1, two sources of data have been utilized in validating the proposed instructional model and its content. First, a reflective journal opinion form (Chitpin, 2006; Cooper & Stevens, 2006) was devised to record the review generated by the reviewers (i.e., two instructors and two students) (Appendix, Table A). It is a potent technique that can help to develop a better and more organized instructional strategy. This reflective journal approach appears to be beneficial in allowing students to reflect on their learning as well as the effectiveness of the instructional method (Cooper & Stevens, 2006). Thorpe (2004) found a wide range of reflections from the reviewers while using this approach. These reviews lead to a more thorough understanding of the instructional technique and help to fine-tune it.

Second, the content validation index (CVI) has been used to validate the content of the proposed instructional design (Appendix, Table B). The content Validity Index (CVI) is the most frequently used quantitative measure for determining the validity of the contents of any given course material (Rodrigues et al., 2017). Content validity is a critical early step in enhancing the construct validity of an instrument (Yusoff, 2019). Content validation determines whether the items included in the course design accurately represent all the domains of learning. As a result, content validity works as the primary indicator of how well content is developed (Waltz et al., 2016). Research shows that good content validity implies that the materials are well-developed following current evidence and best practices (Yusoff, 2019). This study formulated the CVI scale based on the methods from several published articles (J. Lee et al., 2017; Polit et al., 2007; Waltz et al., 2016).

The data derived from the content validity index (CVI) scale has been analysed to measure whether the experts agree on the content’s suitability for the blended learning context. In the CVI scale, the TVET experts analysed the appropriateness of the content on four different dimensions, i.e., content reliability, comprehensibility, user-friendliness, and the generality of the instructional design (Banyen et al., 2016; Hoffman, 2013; J. Lee et al., 2017). A 4-point rating scale on a continuum from not clear (1) to very clear (4) has been utilized to collect the expert opinion on 14 different items about the contents (Appendix, Table B).

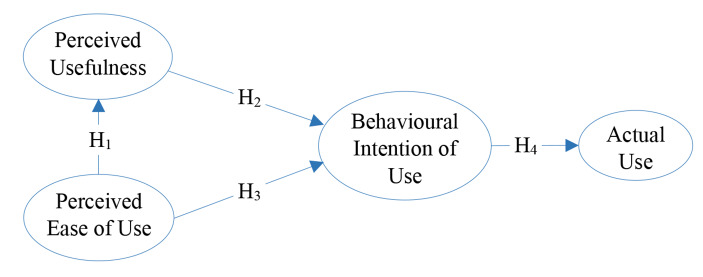

Acceptance and usability of the instructional design

To answer the RQ2, this study used the technology acceptance model (TAM) to examine its acceptance and usability by the end-users, i.e., students. TAM has been widely utilized in studies on the acceptance of new technologies by users (Davis, 1985). The primary goal of the TAM model is to give insight into users’ views about new technology adoption. The original TAM proposed four key areas to evaluate, i.e., perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, behavioral intention to use, and actual use (Davis, 1989).

Perceived usefulness (PU) is defined as the extent to which an individual feels that utilizing a certain technology would improve his or her work performance (Alshurideh et al., 2019). Several empirical investigations have shown that PU is the most important factor in deciding whether or not to use a particular technology (Tan et al., 2012; Tarhini et al., 2017). Students usually adopt a new technology system when they believe that its use will improve their learning performance (Davis, 1985).

Perceived ease of use (PEU) of a system refers to the degree to which an individual believes that utilizing a certain technology is simple and has no difficulties involved (Davis, 1989). In an online learning context, Lin et al. (2011) defined PEOU as the degree to which users perceive that utilizing an e-learning system will be effortless. Previous studies have shown that the perceived ease of use has a major impact on the perceived usefulness of a product (Binyamin et al., 2019; Zogheib et al., 2015). Hence, the authors hypothesize that the students’ perceived ease of use of the proposed instructional model influences the perceived usefulness of the proposed instructional model in the blended learning context.

H1: Perceived ease of use (PEU) has a positive influence on perceived usefulness (PU)

PU has been shown to have a substantial effect on behavioral intentions (BI) toward e-learning adoption (Ritter, 2017; Teo, 2012; G. K. W. Wong, 2015; Zogheib et al., 2015). There is a substantial positive link between perceived usefulness (PU) and behavioral intention to utilize the e-learning system (Mahmodi, 2017). Thus, the following hypothesis has been formulated:

H2. Perceived usefulness (PU) has a positive influence on the Behavioural intention (BI) to use the proposed instructional design

Behavioral intention is a cognitive process of a person’s readiness to undertake a particular activity and is a direct precursor of usage behavior. Behavioral intention (BI) refers to the intention of learners to utilize e-learning systems, which often includes a long-term commitment (Liao & Lu, 2008). Research shows that PEU is positively associated with behavioral intention to employ it, both directly and indirectly (Sandjojo & Wahyuningrum, 2016). Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H3. Perceived ease of use (PEU) has a positive influence on the Behavioural intention (BI) to use the proposed instructional design

Research has also demonstrated that the behavioral intention of an e-learning system directly and considerably determines the actual usage of the new technology system (Mou et al., 2016). We, therefore, hypothesized that students’ behavioral intention to use the proposed instructional design prototype impacts their actual use of it in the blended learning context.

H4: Behavioural intention of use (BI) has a positive influence on the actual use (AU) of the proposed instructional design

Based on the TAM literature, we have formulated a 12 items survey to examine the acceptance and usability of the proposed instructional model (Fig. 3). Altogether, 7 items have been adopted from Al-Maroof and Al-Emran (2018) and Mailizar et al., (2021). Finally, five items were newly created to develop the 12 items survey instrument (Appendix, Table C).

Fig. 3.

Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to examine students’ acceptance of the proposed instructional model

Partial least squares (PLS) based structural equation modelling (SEM) was utilized to analyze the data gathered from the TAM model for evaluating the students’ acceptance of the proposed instructional model. Data from the TAM model helped to re-examine the underlying variables that contribute to students’ adoption of the new instructional design. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to validate the construct of each dimension of the TAM model. CFA is a theory-driven approach to determine whether or not the number of factors and their loadings with measured variables adhere to the pre-established theory (Hung et al., 2010).

Effectiveness of the instructional design

Finally, to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed instructional design (RQ3), we compared students’ performance in the IC Engine Principle course in the BL context with other engineering courses conducted in the traditional learning context. A paired-sample t-test has been used to compare the students’ performances.

Results

Model validation

Reviewers’ reflections from the opinion form were analysed first to examine the content validity. Reviewers have carefully gone through each of the learning items and online lessons and mentioned whether the items and lessons are suitable for the proposed instructional design for the BL context. The following table shows the reviewers’ (students and faculty members) reflections on the suitability of the contents. Four reviewers were engaged in this section. They were given a model validation form in which they were required to indicate the suitability of the learning contents.

Table 3 reveals that most of the reviewers agreed with the suitability of the online course contents for the BL approach. However, some class tests and assignments were extensively modified as per reviewers’ suggestions. Reviewers were also advised to provide suggestions about the learning materials and course contents. Their suggestions were then analyzed qualitatively to rectify the items and improve the fidelity of each lesson. The reviewers offered several recommendations for making the online classroom more engaging and participatory. For example, one of the reviewers wrote,

The rubrics of the assignment are necessary for online classrooms to ensure clarity.

Table 3.

The reviewers’ reflection on the suitability of the contents

| Classes | Items | Suitability (in %) |

|---|---|---|

| Online Class 1 | Online lecture | 75 |

| Video contents | 100 | |

| Assignment | 75 | |

| Class test | 50 | |

| Online Class 2 | Online lecture | 100 |

| Video contents | 100 | |

| Assignment | 75 | |

| Class test | 75 | |

| Online Class 3 | Online lecture | 100 |

| Video contents | 75 | |

| Assignment | 100 | |

| Class test | 75 | |

| Online Class 4 | Online lecture | 100 |

| Video contents | 75 | |

| Assignment | 75 | |

| Class test | 100 | |

| Online Class 5 | Online lecture | 100 |

| Video contents | 75 | |

| Assignment | 100 | |

| Class test | 100 |

Based on the reviewer’s feedback, a rubric has been developed, which is designed to assist students in reflecting upon their progress in completing activities in online courses. Some reviewers commented on the need to restructure the sequence of the contents; this suggestion was accepted and acted upon. For example, one reviewer said-

It will be helpful for the students if the class materials are organized properly in the course stream. It will help the students to follow the classroom properly.

.

Thus, online learning has been reorganized lesson by lesson in a single interface of the Google classroom so that students can easily follow the learning materials. Also, some incremental changes have been made for each of the lessons as per the reviewers’ feedback, which ensured the prototype’s fidelity.

Further, the content validation index (CVI) has been used to examine the experts’ feedback to validate the contents of the proposed instructional design. CVI is the most generally reported technique to validate the content of an instrument or intervention (Zamanzadeh et al., 2015). Typically, the value of item CVI (I-CVI) and Scale-level-CVI (S-CVI) have been used for content validation. The CVI with a value of 1.00 or near 1.00 indicates very good content validity, whereas a value of 0.50 or less indicates an inadequate degree of content validity (Martuza, 1977). The S-CVI is determined based on the number of components in a tool that have received a very positive rating, such as ‘very suitable. Finally, S-CVI using the Universal Agreement (UA) (S-CVI/UA) and (S-CVI/AVE) has been calculated to check the content validity of the course designed for the BL context (Zamanzadeh et al., 2015).

As revealed in Table 4, the content validity was found to be high as the I-CVI was greater than 0.80 for each of the constructs. Also, the mean S-CVI/UA was greater than 0.700, and the mean S-CVI/AVE was found to be greater than 0.90, which was deemed satisfactory (Polit et al., 2007). For items’ reliability, the Cronbach alpha coefficient for each construct was more than 0.60, which is considered reliable and satisfactory (Hair et al., 2009).

Table 4.

Content Validity Index (CVI) of the proposed instructional design

| Construct | Total Items | S-CVI/UA | S-CVI/AVE | Cronbach Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content Reliability | 5 | 0.667 | 0.889 | 0.769 |

| Comprehensibility | 5 | 0.667 | 0.925 | 0.618 |

| User-friendliness | 5 | 0.833 | 0.914 | 0.804 |

| Generality | 5 | 0.667 | 0.880 | 0.625 |

| Avg. S-CVI/UA | 0.709 | |||

| Avg. S-CVI/AVE | 0.902 | |||

Model acceptance

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

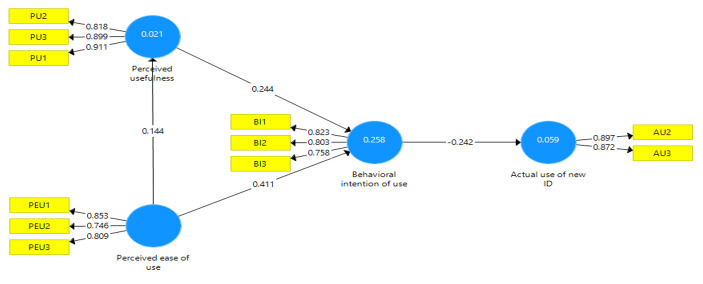

Based on the TAM constructs, this study conducted structural equation modelling (SEM) using smart PLS to evaluate the student’s acceptance of the proposed model (Ramayah et al., 2018). PLS-SEM produces more accurate estimates when the sample size is limited and is recommended for predicting the relationships of the theoretical construct (Hair et al., 2020). PLS analysis employs two distinct models- the measurement and the structural model. The measurement model, also known as the outer model, depicts the underlying relationships of the latent constructs, whereas the structural model, also known as the inner model, defines the relationships between the exogenous and endogenous variables of the model. Gefen et al., (2000) and Hair et al., (2017) presented various recommendations regarding the validation of the measurement and structural models. Based on the recommendations, this study examined the outer loadings of the survey items and the average variance extracted (AVE) to determine the measurement model’s convergent validity. Discriminant validity was determined using cross-loading and the Fornell-Larcker criteria. Additionally, this study used the bootstrapping technique for determining the statistical significance of the path coefficients of the relationships, the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio, and the coefficient of determination (R2) values (Hair et al., 2017). Henseler et al. (2015) proposed that the HTMT needs to be examined to develop a more stringent discriminant validity of the constructs. The R2 in the structural model was investigated to predict the proportion of the variation of the dependent variable, i.e., students’ acceptance of other independent variables in the model.

Table 5 shows the convergent validity and the reliability of the TAM constructs. The composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha (α) value are larger than 0.7, and the AVE value larger than 0.50 provide excellent convergent validity and reliability of the model (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). However, in determining the measurement model, one item (AU1) was dropped as the factor loading was found to be below 0.40 for the item (Hulland, 1999). Further, as shown in Table 5, the square root of the AVE on the diagonal (in bold numbers) is greater than the correlations of the constructs, confirming the validity of the measurement model (Hair et al., 2017).

Table 5.

Reliability, convergent, and discriminant validity

| Measures | Items | CR | AVE | Reliability (α) | AU | BI | PEU | PU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual Use (AU) | 2 | 0.878 | 0.782 | 0.722 | 0.885 | |||

| Behavioral Intention of Use (BI) | 3 | 0.837 | 0.632 | 0.711 | -0.242 | 0.795 | ||

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) | 3 | 0.845 | 0.646 | 0.730 | -0.113 | 0.447 | 0.804 | |

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | 3 | 0.909 | 0.769 | 0.856 | 0.141 | 0.303 | 0.144 | 0.877 |

Table 6 shows good convergent and discriminant validity as all items had larger loadings (> 0.700) on their respective constructs and lower loadings on other constructs. These data show that the psychometric characteristics of the TAM constructs were excellent for the proposed instructional design (Hair et al., 2017). The HTMT values shown in Table 7 indicate that all model construct values fall below the threshold value of 0.85, which satisfies the condition of strict discriminant validity (Henseler et al., 2015).

Table 6.

Multicollinearity assessment and factor structure matrix of the model

| Constructs | Items | AU | BI | PEU | PU | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual Use (AU) | AU2 | 0.897 | -0.225 | -0.045 | 0.018 | 1.470 |

| AU3 | 0.872 | -0.203 | -0.16 | 0.244 | 1.470 | |

| Behavioral Intention of Use (BI) | BI1 | -0.145 | 0.823 | 0.393 | 0.367 | 1.366 |

| BI2 | -0.176 | 0.803 | 0.355 | 0.216 | 1.453 | |

| BI3 | -0.275 | 0.758 | 0.309 | 0.107 | 1.366 | |

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) | PEU1 | -0.08 | 0.447 | 0.853 | 0.103 | 1.489 |

| PEU2 | -0.089 | 0.31 | 0.746 | 0.146 | 1.332 | |

| PEU3 | -0.109 | 0.286 | 0.809 | 0.101 | 1.631 | |

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | PU1 | 0.132 | 0.306 | 0.126 | 0.911 | 2.340 |

| PU2 | 0.197 | 0.185 | 0.002 | 0.818 | 2.070 | |

| PU3 | 0.083 | 0.275 | 0.193 | 0.899 | 2.054 |

Table 7.

Results of Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio for discriminant validity

| Construct | AU | BI | PEU | PU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual Use (AU) | |||||

| Behavioral Intention of Use (BI) | 0.347 | ||||

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) | 0.181 | 0.594 | |||

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | 0.231 | 0.353 | 0.163 | ||

This study also checks the collinearity issue because it affects weight estimates and the statistical significance of the relationships of the items. Table 6 shows that the variance inflation factor (VIF) of all the items is below 5.0, indicating that the model is free from multicollinearity issues (Hair et al., 2017).

Finally, the structural model using the TAM constructs has been examined to check the predictive explanatory power (R2), and the cross-validated redundancy (Q2) of the model (Fig. 4). The predictive explanatory power (R2) indicates the degree to which the independent variables adequately explain the dependent variables. Cohen (1988) recommended that predictive explanatory power can be classified as substantial, moderate, or weak when R2 values are above 0.26, 0.13, or 0.02, respectively. Our model shows in Table 8 a moderate explanatory power (R2 = 0.258) for behavioral intention to use (BI) and weak explanatory power for both actual use and perceived usefulness for the proposed instructional design (R2 = 0.059, 0.021).

Fig. 4.

Results of the structural model using TAM

Table 8.

Results of Structural Model

| Constructs | R 2 | Q 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Use (AU) | 0.059 | 0.033 |

| Behavioral Intention of Use (BI) | 0.258 | 0.133 |

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | 0.021 | 0.005 |

The cross-validation redundancy (Q2) is used to assess the model’s predictive relevance for the latent dependent variables. If Q2 > 0, the model is considered predictively relevant (Geisser, 1975; Stone, 1976). According to the results in Table 8, the structural model is acceptable since the exogenous constructions have predictive relevance for the model’s endogenous components.

Table 9 explores the hypotheses test results between different TAM constructs. It reveals that both perceived usefulness (H2) (β = 0.244, t = 2.229, p < 0.05) and perceived ease of use (H3) (β = 0.411, t = 4.025, p < 0.05) had a positive influence on behavioural intention to use the proposed instructional design. Similarly, hypothesis H4 revealed the behavioral intention of use had a positive influence on actual usage of the proposed instructional design (β = -0.242, t = 2.231, p < 0.05), But hypothesis H1 suggests that perceived ease of use did not have a positive influence on perceived usefulness (β = 0.144, t = 0.919, p > 0.05).

Table 9.

Results of hypotheses testing using path analysis

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Std. beta (β) | SD | t - value | p-value | decision | f 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H 1 | PEU → PU | 0.144 | 0.156 | 0.919 | 0.359 | Not supported | 0.021 |

| H 2 | PU → BI | 0.244 | 0.110 | 2.229 | 0.026 | Supported | 0.079 |

| H 3 | PEU → BI | 0.411 | 0.102 | 4.025 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.223 |

| H 4 | BI → AU | -0.242 | 0.109 | 2.231 | 0.026 | Supported | 0.062 |

Sullivan and Feinn (2012) stressed that a p-value indicates the presence of a statistically significant impact but does not provide insights into the strength of these relationships. Thus, it is important to present and evaluate the impact size (f2) to understand the strength of these relationships. Cohen (1988) reported that the f2 values of 0.02, 0.1, and 0.35 indicate small, medium, and large impact sizes, respectively. The results in Table 9 show that the impact of perceived usefulness (PU) on behavioral intention (BI) and the impact of behavioral intention (BI) on actual use (AU) are small. In contrast, perceived ease of use (PEU) has a medium impact size on behavioral intention (BI) to use the proposed instructional design.

Model effectiveness

After running a full semester in the BL context, students’ final exam score in the IC Engine Principle course was compared with the scores of other non-BL courses. A paired-samples t-test was used to examine student performances in both contexts. As revealed in Table 10, the results showed an improved performance in the IC Engine Principle course (M = 3.228, SD = 0.60417) compared to the overall CGPA of other non-BL courses (M = 3.087, SD = 0.78382). The result is statistically significant at t (66) = -2.410, p < 0.05. The effect size (0.081) further shows that this is a moderate improvement in students’ performances due to the intervention, e.g., the implementation of the proposed instructional design in the BL context (Cohen, 1988).

Table 10.

Paired sample t-test results for students’ improvement of performance in the BL context

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Paired Differences | t | df | Sig. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | St. error | Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||||

| Overall CGPA (other courses) | 3.087 | 0.784 | − 0.140 | 0.477 | 0.058 | − 0.257 | − 0.024 | -2.410 | 66 | 0.019 |

| GPA (IC Engine course at BL context) | 3.228 | 0.604 | ||||||||

Also, the graduate progression chart (Table 11) indicates the passing rate of the students in the IC Engine Principle course. The passing rate is found to be higher for the academic year 2021 when the “IC Engine Principle” course has been delivered in BL mode with the proposed instructional design.

Table 11.

Students’ progression chart for the IC Engine Principle course

| Academic Year | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of students | 84 | 80 | 81 |

| Total number of passing students | 61 | 61 | 67 |

| Graduate progression rate | 73% | 76% | 83% |

Discussion

This study conceptualized a pedagogical framework combining the ADDIE and rapid prototyping model for the blended learning context to be used by the course designers in the TVET context of Bangladesh. The proposed model has been validated by the reviewers and experts, and its effectiveness and acceptance by the students were examined. The findings revealed that the proposed pedagogical design is reliable and valid and thus might be appropriately implemented in the blended learning context of the polytechnic institutes of Bangladesh. The polytechnic students demonstrated a positive attitude towards the model and performed better in the achievement test compared to the students without the blended learning session.

Decades of research show the importance of blending online and face-to-face classrooms to offer effective learning experiences for students (J. Lee et al., 2017; Mason et al., 2013). In the context of polytechnic institutes of Bangladesh, a customized ADDIE-RP instructional design confirmed the same for a marine engineering course in the BL environment through content validation (Polit et al., 2007). As revealed, the course implemented with the customized ADDIE-RP model received positive reviews from experts. Research shows that due to its adaptability, ADDIE can contribute to and satisfies most instructional needs (Campbell, 2014). This might be the key contributing factor to receiving such positive reviews from experts and reviewers. However, as ADDIE requires more time to adapt, the RP Model complements this deficiency by providing formative feedback and quick adoption of necessary technologies at an early stage (Dong, 2021). This unique feature of RP offers effective communication among the instructors and facilitates their focus on the teaching and learning activities through trialability in the quickest possible time (Botturi et al., 2007). In summary, RP could address the limitations of ADDIE by integrating formative feedback elements and early adaptations. Thus, the proposed model provides a unique, open, and flexible pedagogical framework to be implemented in the BL environment of the polytechnic institutes of Bangladesh. The findings of this study are consistent with other recent studies that suggested that rapid prototyping and ADDIE should be used together to create instructional design since they both have the potential to enhance blended learning environments (J. Lee et al., 2017).

The CVI index of the proposed model also indicates content interpretability, comprehensibility, usability, and generality of the instructional design (J. Lee et al., 2017). Interpretability is described as the capacity to explain or convey the meaning to a person in a way that can be easily understood (Barredo Arrieta et al., 2020). This is the major strength of this model. In a similar vein, the easy comprehensibility of the model allowing the users to grasp what the proposed instructional design can deliver, is a key strength of this model. The usability of the model also received a very positive rating from the experts, which confirms it is easy to use, and effective for interaction (de Oliveira et al., 2021).

This study utilized the Technical Acceptance Model (TAM) to recognize students’ acceptance of the proposed instructional design and examine its actual use by the students. The findings revealed that perceived usefulness (PU) has a significant positive influence on the behavioral intention (BI) to use this prototype. This result is in line with other studies where there is a strong relationship between perceived usefulness and behavioral intention to use a new instructional prototype (Salloum et al., 2019; K. T. Wong et al., 2013). It can be argued that when students believe that modern technology could enhance their performance, it inherently influences their behavioral intentions to use the technology. This model also revealed that perceived ease of use (PEU) had positively influenced the behavioral intention (BI) to use it. This finding is consistent with the studies conducted by Davis (1989), Motaghian et al. (2013), and Park (2009). It is evident that when students found the proposed model comfortable and easy to use, it positively affected their behavioral intention to use it. It is to be noted that perceived ease of use (PEU) had no positive impact on perceived usefulness (PU), which is in contrast with some other studies that reported a direct positive relationship between them (Akmal, 2017; Cigdem & Topcu, 2015). Liu et al. (2010) also argued that course design and user interface are the most important factors that directly affect PEU and encourage students to opt for new technology. However, Motaghian et al. (2013) also argued that significant positive relations between perceived ease of use (PEU) and perceived usefulness (PU) may not always be established. It is argued that some other variables, e.g., age, gender, subject, instructor preparation and support, and years of teaching experience, could be responsible for this deviation (Dai et al., 2020). Future research can explore further the relationships among these variables with the perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness.

Finally, the effectiveness of this model has been examined by implementing the proposed instructional design in a blended learning context. This study designed a marine engineering course with the proposed model and offered it formally to the students for a full semester. The results showed moderate improvement in students’ academic performance in the BL course compared to the non-BL courses. The findings of this study are consistent with earlier studies that found significant improvements in students’ attitudes and satisfaction while taking BL courses and these improvements are directly related to the students’ academic performances (Bland, 2006; Kellogg, 2009; Kintu et al., 2017) concluded that students’ academic performance might be improved by implementing the proper web technology for assignments and exams. Tian & Suppasetseree (2013) also found that an online task-based instructional model significantly improves students’ performance. In fact, educators continually look for innovative approaches to keep classes exciting and engaging while utilizing technology in the blended learning context (Arghode et al., 2018).

Implications of the research

Though ADDIE is popular among instructional designers (DeBell, 2020), it comes with its limitations. Educators, course designers, and academic libraries should take measures to overcome these limitations while maintaining the quality of the ADDIE model during the instructional design process. The current study offers a modified framework that includes some aspects of RP into ADDIE to improve the overall efficiency of this theoretical approach. Creating such a unique theoretical framework can lay down the foundation around which educators could construct compelling instructional materials for a blended learning environment.

Also, this study has several practical implications for TVET educators in the context of higher education in Bangladesh. TVET educators can organize training for the instructional designers to solve certain difficulties related to the instructional design in the blended learning context by employing the proposed model. Specifically, the collaboration between the course designers of different institutions can take place to develop a universal instructional design for higher institutions (Linh & Suppasetseree, 2016). Given that instructional design has an impact on the quality of instruction, this proposed model would assist Bangladeshi TVET course designers in gaining the skill set necessary to create blended learning sessions that will increase the learning effectiveness and efficiency of the students. Since there is no instructional design for establishing a BL environment in Bangladesh, the proposed model, intended for TVET education as well as other higher education programs, can fill this gap. To give educators a better grasp of the underlying design processes and to enable them to make better, more informed decisions, this study explicitly explained the steps of the key design component of the proposed model. Additionally, the outcome of this study might encourage individual TVET teachers to design and implement their courses for blended learning environments at their respective institutes.

In this research, Google Classroom and Facebook were shown to be more readily available to be used as educational tools that are suitable for polytechnic students’ learning styles and preferences. The TVET educators could also consider the potential use of social media as viable tools to utilize in instructional design development. Also, this proposed ID can be used as a framework for developing similar courses in other similar domains of learning, i.e., medical, nursing, engineering, and science education.

Limitations and future research direction

This study was limited to only two polytechnic institutes, and only eighty-one students were engaged in validating the acceptance of the proposed instructional design. All the students came from a single discipline. Recruiting students from different disciplines and institutes could help to scale up the potential effectiveness of the model. Keeping these limitations into consideration, the findings of this study may apply and be generalizable only to the disciplines taught in the polytechnic institutes of Bangladesh.

Methodically, this paper focuses mostly on the quantitative data to validate and measure the acceptance and effectiveness of the customized prototype. Though in the reflective opinion form, a limited amount of qualitative data was used for designing and developing the course contents, more qualitative data could be incorporated for subsequent studies to strengthen the validation of the proposed model.

This study only focused on micro-level course design (J. Lee et al., 2017), overlooking the macro-level design aspects of the curriculum. In fact, this instructional framework lends itself to an individualistic approach to designing a BL environment for the courses. To secure a comprehensive understanding of the course design, the TVET educators and course designers need to consider aspects of instructional design for both macro and micro levels.

This study did not compare the implementation time of the current project with other similar projects. Future studies can investigate how much time could be saved using this modified ADDIE-RP framework compared to other ADDIE approaches.

Another methodological limitation of RP is due to the fast-paced approach, which often prevails in the instructional design at the expense of quality. This quick, fast-paced approach can have a detrimental impact on subsequent advances, impeding comprehension, teamwork, and commitment. Though the ADDIE model has elements of quality control, this study did not explicitly examine the drawbacks of the fast-paced RP approach. Future research might consider all the drawbacks of the RP and ADDIE models and can control them during the prototype design process.

Conclusion

Amid COVID-19, course instructors of the polytechnic institutes of Bangladesh were under high pressure to deliver their teaching. Thus, the TVET course designers urgently looked for options to create a rapid BL session for their students within a short space of time. Nonetheless, it was a daunting task for the researcher to create a compelling and quick prototype convenient for TVET educators, as the concept of online learning is new for many TVET institutions in Bangladesh.

This study endeavored to make an effective and quick instructional design for the TVET educators to support the course designers during the pandemic. The proposed instructional design has the potential to solve the immediate educational challenges and can offer a long-term solution even beyond the post-pandemic situations for this group. The core strength of this model was to offer the resource-constrained TVET course designers a framework to accomplish a reliable and robust instructional design within a brief time frame. In this regard, this ADDIE-RP instructional design could bring a major break-through in the BL environment for the TVET institutions of Bangladesh.

Appendix

Table A Reviewers Opinion Journal.

| Class No. | Item | Suitable / Not suitable | Suggestions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Online Class 1 | Online lecture | ||

| Video contents | |||

| Assignment | |||

| Class test | |||

| Online Class 2 | Online lecture | ||

| Video contents | |||

| Assignment | |||

| Class test | |||

| Online Class 3 | Online lecture | ||

| Video contents | |||

| Assignment | |||

| Class test | |||

| Online Class 4 | Online lecture | ||

| Video contents | |||

| Assignment | |||

| Class test | |||

| Online Class 5 | Online lecture | ||

| Video contents | |||

| Assignment | |||

| Class test |

Table B Content Validation of The Prototype.

| Constructs | Features | Items/Dimensions | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contents Reliability |

i. Clearly defined learning goals ii. Alignment of content with educational objectives iii. Exclusion of Unnecessary Information iv. Constructive feedback (i.e., quizzes, self-check questions, exercises, activities, tests, and other practice exercises or testing activities) v. Accuracy of information vi. Consistency of instructional materials with the intended learning outcome |

Item 1/Online Class 1 Item 2/ Online Class 2 Item 3/Online Class 3 Item 4/ Online Class 4 Item 5/ Online Class 5 |

||||

| Comprehensibility of the prototype |

i. Prototype actions and understanding ii. Auditory and visual compatibility |

Item 1/Online Class 1 Item 2/ Online Class 2 Item 3/Online Class 3 Item 4/ Online Class 4 Item 5/ Online Class 5 |

||||

| User-friendliness of the prototype |

i. A user-friendly interface ii. The ability to divert from the course flow. iii. Distinctive navigation technique iv. The authority of students to evaluate their abilities and practice |

Item 1/Online Class 1 Item 2/ Online Class 2 Item 3/Online Class 3 Item 4/ Online Class 4 Item 5/ Online Class 5 |

||||

| The generality of the prototype |

i. Positive Interaction with other instructional designers ii. Reliability of Prototype in designing a comparable course |

Item 1/Online Class 1 Item 2/ Online Class 2 Item 3/Online Class 3 Item 4/ Online Class 4 Item 5/ Online Class 5 |

Table C TAM for assessing of proposed instructional design.

| Constructs | Items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Usefulness | |||||

|

PU1 PU2 PU3 |

I believe technology improves my quality of learning. I believe web platforms should be used regularly in teaching. I believe a blended learning environment improved my learning capacity. |

||||

| Perceived Ease of Use | |||||

|

PEU1 PEU2 PEU3 |

The prototype has a user-friendly interface. All the contents in the prototype are easily accessible. I find it easy to navigate through the classroom |

||||

| Behavioral Intention of Use | |||||

|

BI1 BI2 BI3 |

I would like to keep myself updated with new educational technology. I am more comfortable with blended learning than only face-to-face learning. I want to attend more courses that offer blended learning. |

||||

| Actual Use | |||||

|

AU1 AU2 AU3 |

I use all the features of this prototype alone regularly I take part in test activities frequently (e.g., quizzes and assignments). I like to access all digital learning materials daily and can download/ upload files. |

||||

Funding

This research is funded by the Islamic University of Technology (IUT).

Data Availability

All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical declaration.

This study is approved by Committee for Advanced Studies and Research (CASR), Islamic university of Technology (IUT), Bangladesh.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shariful Islam Shakeel, Email: shakeel@iut-dhaka.edu.

Md Abdullah Al Mamun, Email: a.mamun@iut-dhaka.edu.

Md Faruque Ahmed Haolader, Email: tve.haolader@iut-dhaka.edu.

References

- Adedoyin, O. B., & Soykan, E. (2020). Covid-19 pandemic and online learning: the challenges and opportunities. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–13. 10.1080/10494820.2020.1813180.

- Akmal, A. (2017). Influence of Perceived Usefulness and Ease of Use on Students’ Continuous Intention in Learning on-Line English Lessons: an Extended Tam. UAD TEFL International Conference, 1, 28. 10.12928/utic.v1.146.2017

- Al-Amin M, Zubayer A, Al, Deb B, Hasan M. Status of tertiary level online class in Bangladesh: students’ response on preparedness, participation and classroom activities. Heliyon. 2021;7(1):e05943. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e05943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Maroof RAS, Al-Emran M. Students acceptance of google classroom: an exploratory study using PLS-SEM approach. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning. 2018;13(6):112–123. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v13i06.8275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al Mamun MA. Technology in Educational Settings in the Government Polytechnic Institutes of Bangladesh: a critical analysis. International Journal of Computer Applications. 2012;54(13):32–40. doi: 10.5120/8628-2502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al Mamun, M. A. (2018). The role of scaffolding in the instructional design of online, self-directed, inquiry-based learning environments: student engagement and learning approaches [The University of Queensland]. 10.14264/uql.2018.607

- Al Mamun MA, Azad MAK, Mamun A, Boyle M. Review of flipped learning in engineering education: scientific mapping and research horizon. Education and Information Technologies. 2022;27(1):1261–1286. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10630-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Mamun MA, Hossain MA, Salehin S, Khan MSH, Hasan M. Engineering students’ readiness for online learning amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: scale validation and lessons learned from a developing country. Educational Technology & Society. 2022;25(3):30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Al Mamun MA, Lawrie G, Wright T. Instructional design of scaffolded online learning modules for self-directed and inquiry-based learning environments. Computers & Education. 2020;144:103695. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al Mamun MA, Lawrie G, Wright T. Exploration of learner-content interactions and learning approaches: the role of guided inquiry in the self-directed online environments. Computers & Education. 2022;178:104398. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al Mamun MA, Tapan SM. Using ICT in teaching-learning at the polytechnic institutes of Bangladesh: constraints and limitations. Teacher’s World-Journal of Education and Research. 2009;33(1):207–217. [Google Scholar]

- Alammary A, Sheard J, Carbone A. Blended learning in higher education: three different design approaches. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology. 2014;30(4):30. doi: 10.14742/ajet.693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aldoobie, N. (2015). ADDIE Model.American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 5(6).

- Alshurideh, M., Salloum, S. A., Kurdi, A., B., & Al-Emran, M. (2019). Factors affecting the social networks acceptance: An empirical study using PLS-SEM approach. PervasiveHealth: Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare, Part F1479, 414–418. 10.1145/3316615.3316720

- Arghode V, Brieger E, Wang J. Engaging instructional design and instructor role in online learning environment. European Journal of Training and Development. 2018;42(7–8):366–380. doi: 10.1108/EJTD-12-2017-0110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banyen W, Viriyavejakul C, Ratanaolarn T. A blended learning model for learning achievement enhancement of thai undergraduate students. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning. 2016;11(4):48–55. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v11i04.5325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barredo Arrieta A, Díaz-Rodríguez N, Del Ser J, Bennetot A, Tabik S, Barbado A, Garcia S, Gil-Lopez S, Molina D, Benjamins R, Chatila R, Herrera F. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI. Information Fusion. 2020;58:82–115. doi: 10.1016/j.inffus.2019.12.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Binyamin SS, Rutter MJ, Smith S. Extending the technology acceptance model to understand students’ use of learning management systems in Saudi higher education. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning. 2019;14(3):4–21. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v14i03.9732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bland, L. (2006). Applying flip/inverted classroom model in electrical engineering to establish life-long learning. ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Conference Proceedings. 10.18260/1-2--491

- Botturi, L., Cantoni, L., Lepori, B., & Tardini, S. (2007). Fast Prototyping as a Communication Catalyst for E-Learing Design. In J. Willis (Ed.), Making the Transition to E-Learning (pp. 266–283). IGI Global. 10.4018/978-1-59140-950-2.ch016

- Branson, R. K., Rayner, G. T., Cox, J. L., Furman, J. P., King, F. J., & Hannum, W. H. (1975). Interservice procedures for instructional systems development.Center for Educational Technology, 4(AD-A019 468).

- BTEB (2016). Bangladesh Technical Education Board Course Structure & Syllabus (2016 Probidhan). https://bteb.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/bteb.portal.gov.bd/page/84dc01b3_d072_48f9_8aaa_aca776301210/2099.1.pdf

- Campbell PC. Modifying ADDIE: incorporating New Technologies in Library instruction. Public Services Quarterly. 2014;10(2):138–149. doi: 10.1080/15228959.2014.904214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carman, J. M. (2002). Blended learning design: Five key ingredients. Learning, 11. 10.1109/CSSE.2008.198

- Chen LL. A model for effective online Instructional Design. Literacy Information and Computer Education Journal. 2016;7(2):2303–2308. doi: 10.20533/licej.2040.2589.2016.0304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chitpin S. The use of reflective journal keeping in a teacher education program: a popperian analysis. Reflective Practice. 2006;7(1):73–86. doi: 10.1080/14623940500489757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury SA. Impacts of ICT integration in the Higher Education Classrooms: Bangladesh Impacts of ICT Integration in the Higher Education Classrooms: Bangladesh Perspective. Journal of Education and Practice. 2018;9:15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cigdem H, Topcu A. Predictors of instructors’ behavioral intention to use learning management system: a turkish vocational college example. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;52:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Cooper JE, Stevens DD. Journal-keeping and academic work: four cases of higher education professionals. Reflective Practice. 2006;7(3):349–366. doi: 10.1080/14623940600837566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Z, Wang M, Liu S, Tang L. Design and the technology acceptance model analysis of instructional mapping. Computer Applications in Engineering Education. 2020;28(4):892–907. doi: 10.1002/cae.22261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das TK. Online Education during COVID-19: prospects and Challenges in Bangladesh. Space and Culture India. 2021;9(2):65–70. doi: 10.20896/saci.v9i2.1220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F. D. (1985). A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: theory and results [Massachusetts Institute of Technology]. https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/15192

- Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems. 1989;13(3):319–339. doi: 10.2307/249008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, M., Mattedi, A. P., & Seabra, R. D. (2021). Usability evaluation model of an application with emphasis on collaborative security: an approach from social dimensions. Journal of the Brazilian Computer Society, 27(1), 10.1186/s13173-021-00108-8.

- DeBell, A. (2020). What is the ADDIE Model of Instructional Design?Water Bear Learning. https://waterbearlearning.com/addie-model-instructional-design/

- Dong H. Adapting during the pandemic: a case study of using the rapid prototyping instructional system design model to create online instructional content. Journal of Academic Librarianship. 2021;47(3):102356. doi: 10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981;18(1):39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D., Straub, D., & Boudreau, M. C. (2000). Structural equation modeling and regression: guidelines for Research Practice. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 4(Oc), 10.17705/1cais.00407.

- Geisser S. The predictive sample reuse method with applications. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1975;70(350):320–328. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1975.10479865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J., Black, Black, B., & Anderson. (2009). &. Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Hair, J., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th edition).

- Hair, J., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109(August 2019), 101–110. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

- Hair, J., Hult, G. T. T., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2015;43(1):115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, J. S. (2013). Instructional Design—Step by Step: Nine Easy Steps for Designing Lean, Effective, and Motivational Instruction. iUniverse. https://books.google.com/books?id=xCvPUzd0DmcC&pgis=1

- Hossain, A., & Ahmed, A. (2013). Prospect of ICT-based Distance (online) Learning for Pedagogical Development in Bangladesh.National Academy for Educational Management (NAEM) Journal, 9(7).

- Hulland J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: a review of four recent studies. Strategic Management Journal. 1999;20(2):195–204. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0266(199902)20:2<195::aid-smj13>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hung MLL, Chou C, Chen CHH, Own ZYY. Learner readiness for online learning: scale development and student perceptions. Computers and Education. 2010;55(3):1080–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2010.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M. K., Sarker, M. F. H., & Islam, M. S. (2022). Promoting student-centred blended learning in higher education: a model. E-Learning and Digital Media, 204275302110277. 10.1177/20427530211027721.

- Jahan, I., Rabbi, F., & Islam, U. N. (2021). Can Blended Learning be the New-Normal in Higher Education of Bangladesh ?Internasional Jurnal of Educational Reserch Review, June,306–317.

- Jones TS, Richey RC. Rapid prototyping methodology in action: a developmental study. Educational Technology Research and Development. 2000;48(2):63–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02313401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, A., & UNICEF Education COVID-19 Case Study. (2020). UNICEF Education COVID-19 (Case Study Malaysia – Empowering Teachers to Deliver Blended Learning after School Reopening 8 July 2020), March, 1–3.

- Kang J, Seomun GA. Evaluating web-based nursing education’s Effects: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2018;40(11):1677–1697. doi: 10.1177/0193945917729160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg, S. (2009). evelop ping On nline Materi ials to Facilit tate an n In nverte d Clas ssroom m Appr roach. 39th ASEE/IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference, 1–6.

- Khan, M. A. (2019). Situation Analysis of Bangladesh TVET Sector: A background work for a TVET SWAp. August.

- Khan MSH, Hasan M, Clement CK. Barriers to the introduction of ICT into education in developing countries: the example of Bangladesh. International Journal of Instruction. 2012;5(2):61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kintu, M. J., Zhu, C., & Kagambe, E. (2017). Blended learning effectiveness: the relationship between student characteristics, design features and outcomes. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14(1), 10.1186/s41239-017-0043-4.