Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of the serious global health challenges of our time. There is now an urgent need to develop novel therapeutic agents that can overcome AMR, preferably through alternative mechanistic pathways from conventional treatments. The antibacterial activity of metal complexes (metal = Cu(II), Mn(II), and Ag(I)) incorporating 1,10-phenanthroline (phen) and various dianionic dicarboxylate ligands, along with their simple metal salt and dicarboxylic acid precursors, against common AMR pathogens were investigated. Overall, the highest level of antibacterial activity was evident in compounds that incorporate the phen ligand compared to the activities of their simple salt and dicarboxylic acid precursors. The chelates incorporating both phen and the dianion of 3,6,9-trioxaundecanedioic acid (tdda) were the most effective, and the activity varied depending on the metal centre. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) was carried out on the reference Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain, PAO1. This strain was exposed to sub-lethal doses of lead metal-tdda-phen complexes to form mutants with induced resistance properties with the aim of elucidating their mechanism of action. Various mutations were detected in the mutant P. aeruginosa genome, causing amino acid changes to proteins involved in cellular respiration, the polyamine biosynthetic pathway, and virulence mechanisms. This study provides insights into acquired resistance mechanisms of pathogenic organisms exposed to Cu(II), Mn(II), and Ag(I) complexes incorporating phen with tdda and warrants further development of these potential complexes as alternative clinical therapeutic drugs to treat AMR infections.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00775-022-01979-8.

Keywords: Metal complexes; Antimicrobial resistance; Pseudomonas aeruginosa; 1,10-Phenanthroline; Whole genome sequencing

Introduction

Over the past few decades, the emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has outpaced the development and market entry of new antimicrobial agents [1–5]. Drug-resistant infections are associated with higher morbidity, mortality, and health expenditures. Consequently, AMR is now one of the biggest challenges facing modern medicine. The European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net) reports that approximately 670,000 infections occur in the EU each year due to resistant bacteria, with 33,000 directly attributable deaths, costing €1.1 billion in healthcare costs [6]. While on a worldwide scale, the resistance of microorganisms to antimicrobial agents is reported to account for 700,000 deaths annually, and this is set to increase to 10 million by the year 2050 [7]. Although a recent systemic analysis estimated there were 4.95 million deaths associated with bacterial AMR in 2019, including 1.27 million deaths directly attributable to bacterial AMR alone [8]. As seen with the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‑19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the global monitoring of infectious agents in addition to the research and development of new therapeutics to deal with them is paramount. Moreover, the pandemic has exacerbated the existing AMR crisis due to incorrect prophylactic treatment [9]. The World Health Organization (WHO) established the Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS), an operational framework for surveillance of resistance, and in conjunction published a list of antibiotic-resistant priority pathogens in a bid to guide and promote investigation and production of new agents for these highly resistant microorganisms [10]. The priority pathogen list is divided into three categories according to the urgency for new therapeutics and includes Gram-negative bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacterales (critical status), and the Gram-positive bacteria Enterococcus faecium and Staphylococcus aureus (high status). Infections caused by these microorganisms pose a severe worldwide hazard, and the 2020 WHO clinical antibacterial pipeline analysis report stated that the demand for new antimicrobial agents to treat these bacterial infections had not been met [11]. The WHO also included for the first time a comprehensive overview of non-traditional antibacterial medicines in the pipeline, with the aim of encouraging more research in this area. As the post-antibiotic era looms, the crucial need to develop entirely novel therapeutic agents to the current clinical drugs that can overcome antibiotic resistance, preferably through different and multiple biological targets or pathways, is now widely recognised [12].

Interdisciplinary research in inorganic medicinal chemistry with biology is advancing the knowledge and implementation of transition metal complexes into therapy and is offering a realistic alternative to traditional organic antibiotics [13–17]. Several metal-based therapies are progressing through clinical trials and some have already been approved for clinical use [18, 19]. 1,10-Phenanthroline (phen) is a classic chelating bidentate ligand known to exert antimicrobial activity against a broad spectrum of bacteria [20]. The coordination of metal ions with the bioactive hydrophobic N,N’-donor phen can increase their bioavailability through improved cell membrane permeability, yielding significant improvements in activity compared to the free (uncoordinated) metal ions. The development of novel inorganic complexes with phen or phen-like ligands have demonstrated therapeutic promise for treatment of bacteria [21, 22], fungi [23–25], parasites [26, 27] and viruses [28, 29]. Our research group has investigated the antimicrobial potential of metal-based complexes incorporating phen and its derivatives. 1,10-Phenanthroline-5,6-dione (phendione) and its metal complexes, [Cu(phendione)3](ClO4)2·4H2O (Cu-phendione) and [Ag(phendione)2]ClO4 (Ag-phendione), were tested against Brazilian clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa [30], Acinetobacter baumannii [31] and Klebsiella pneumoniae [32] that had demonstrated multidrug-resistant (MDR) patterns. The metal–phendione complexes were potent against both planktonic- and biofilm-growing cells while having low toxicity in Galleria mellonella larvae [25, 33] and in mice [34]. They were effective inhibitors of the metalloenzyme Elastase B (lasB), which is secreted by P. aeruginosa, suggesting this as a novel potential chemotherapeutic target [35]. Moreover, they were able to interact with double-stranded DNA and promote oxidative damage, suggesting multiple mechanisms of action in P. aeruginosa [36].

Herein, we present the antibacterial activity of copper(II), manganese(II) and silver(I) complexes incorporating phen and dicarboxylate ligands against WHO priority pathogens that are also problematic within Irish clinical settings. The microbial panel comprised the Gram-positive bacteria methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE), and the Gram-negative bacteria carbapenem-resistant and ESBL-producing Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, derived from patients in Irish hospitals. For the microbiological screening of the complexes, European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) standardised susceptibility testing methods were utilised as currently these guidelines are used in all diagnostic laboratories throughout Europe. The well-characterised susceptible P. aeruginosa PAO1 strain was selected for subsequent acquired resistance studies to selected lead metal complexes with the aim of deciphering the complexes mechanism of action. This strain was dosed with sub-lethal concentrations of the selected complexes and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) was then performed to unveil any genome changes implicated in acquired resistance mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Test complexes

A range of previously published Cu(II), Mn(II) and Ag(I) complexes incorporating dicarboxylate and 1,10-phenanthroline (phen) ligands, along with their relevant non-phen metal-dicarboxylate precursor complexes were selected for the study. The 22 complexes were generated, purified and characterised as previously published using a similar facile two-step approach involving; (i) reaction of the dicarboxylic acid with the respective metal acetate salt to yield the metal–dicarboxylate complex; and (ii) reaction of the metal–dicarboxylate with excess 1,10-phenathroline to generate the metal–dicarboxylate–phenanthroline complex. The dicarboxylic acids included butanedioic acid (bdaH2), pentanedioic acid (pdaH2), hexanedioic acid (hxdaH2), heptanedioic acid (hpdaH2), octanedioic acid (odaH2), undecanoic acid (uddaH2), phthalic acid (phH2) and 3,6,9-trioxaundecanedioic acid (tddaH2). The codes, chemical formulae, solubility and references to the original synthetic routes and characterisation for all the 22 complexes are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Metal complexes assessed in this study

| Code | Complex formula | Solubility | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cu(II) complexes | |||

| Cu-ph-phen | [Cu(ph)(phen)(H2O)2] | DMSO | [38] |

| Cu-oda | [Cu(oda)]H2O | DMSO | [39] |

| Cu-oda-phen | [Cu(oda)(phen)2]8H2O | DMSO | [39] |

| Cu2-oda-phen | [Cu2(oda)(phen)4](ClO4)22.76H2O.EtOH | H2O | [40] |

| Cu-tdda | [Cu(3,6,9-tdda)]H2O | H2O | [23] |

| Cu-tdda-phen | [Cu(3,6,9-tdda)(phen)2]3H2O.EtOH | H2O | [23] |

| Mn(II) complexes | |||

| Mn-bda | [Mn(bda)]0.2H2O | H2O | [41] |

| Mn-bda-phen | [Mn2(bda)2(phen)2(H2O)4]0.4H2O | H2O | [41] |

| Mn-pda | [Mn(pda)].H2O | H2O | [42] |

| Mn-pda-phen | [Mn(pda)(phen)] | H2O | [42] |

| Mn-hxda | [Mn(hxda)].H2O | H2O | [43] |

| Mn-hxda-phen | [Mn(hxda)(phen)2(H2O)]0.7H20 | H2O | [43] |

| Mn-hpda | [Mn(hpda)] | H2O | [43] |

| Mn-hpda-phen | [Mn(phen)2(H2O)2][Mn(hpda)(phen)2(H2O)]pda.12.5H2O | H2O | [43] |

| Mn-oda | [Mn(oda)]H2O | H2O | [43] |

| Mn-oda-phen | [Mn2(oda)(phen)4(H2O)2][Mn2(oda)(phen)4(oda)2]0.4H2O | H2O | [43] |

| Mn-tdda | [Mn(3,6,9-tdda)]H2O | H2O | [37] |

| Mn-tdda-phen | {[Mn(3,6,9-tdda)(phen)2]3H2O.EtOH}n | H2O | [37] |

| Ag(I) complexes | |||

| Ag-udda | [Ag2(udda)] | H2O | [44] |

| Ag-udda-phen | [Ag2(phen)3(udda)]0.3H2O | H2O | [44] |

| Ag-tdda | [Ag2(3,6,9-tdda)]2H2O | H2O | [23] |

| Ag-tdda-phen | [Ag2(3,6,9-tdda)(phen)4]EtOH | H2O | [23] |

| Controls | |||

| Copper chloride | H2O | ||

| Manganese chloride | H2O | ||

| Silver nitrate | H2O | ||

| 1,10-phenanthroline | MeOH | ||

Figure S 1 shows the core structures of the three key lead complexes that have emerged from this study, {[Cu(3,6,9-tdda)(phen)2]3H2O.EtOH}n (Cu-tdda-phen), {[Mn(3,6,9-tdda)(phen)2]3H2O.EtOH}n (Mn-tdda-phen) and [Ag2(3,6,9-tdda)(phen)4]EtOH (Ag-tdda-phen). X-ray crystallography has established that the Mn-tdda-phen complex is polymeric in nature. Figure S 1(a) shows the repeating unit for Mn-tdda-phen which comprises a six coordinate Mn(II) centre in a slightly distorted octahedral coordination environment, with the nitrogen atoms from two bidentate phenanthroline ligands and the oxygen atoms from two mono-dentate carboxylates from two symmetry-related diacids (which are coordinated in a cis fashion) occupying the coordination sphere [37]. The Cu-tdda-phen complex is believed to have an analogous polymeric structure with its repeating unit (postulated on the basis of very similar analytical and spectral data to those of Mn-tdda-phen) is shown in Fig. S 1(b). The silver complex Ag-tdda-phen, which has been characterized using spectroscopic methods, on the other hand is a binuclear complex comprising two Ag(I)(phen)2 moieties connected via a tdda2− bridge, with each carboxylate function binding to the Ag(I) centres in a monodentate fashion to yield a square pyramidal geometry [Fig. S 1(c)]. All three of these lead complexes are stable and the presence of the tdda2− ligand renders them highly water soluble.

To illustrate that any observed effects were in fact due to the complexes rather than the attached ligands or free metal ions that may be produced within the cellular environment, the activity of the simple metal salts and the metal-free dicarboxylic acids were also included in the study as direct comparators. These included the following: copper(II) chloride (CuCl2), manganese(II) chloride (MnCl2) and silver(I) nitrate (AgNO3), and the free 1,10-phenanthroline (phen) ligand. The metal-free dicarboxylic acids were also included in the study All of the complexes were dissolved in their corresponding diluent (see Table 1) at a concentration of 10 mg/mL. Complexes which were only soluble in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were made in a 0.1% (DMSO/H2O) solution, while phen and the dicarboxylate ligands were dissolved in methanol (MeOH) and diluted down to a 1% (MeOH/H2O) solution. The remaining complexes were fully water-soluble. Working solutions (512 µg/mL) for the bacterial screen were made up in Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB; Cruinn).

Phen 1,10-phenanthroline, bdaH2 butanedioic acid, pdaH2 pentanedioic acid, hxdaH2 hexanedioic acid, hpdaH2 heptanedioic acid, odaH2 octanedioic acid, uddaH2 undecanoic acid, phH2 phthalic acid, 3,6,9-tddaH2 3,6,9-trioxaundecanedioic acid

Clinical isolates and control strains

The clinical isolates obtained for this study were: Gram-positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (n = 5; MRSA1-MRSA5) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (n = 6; VRE1-VRE6), and Gram-negative Enterobacterales, included an extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producer (n = 1; ESBL1), metallo-β-lactamase-producer (n = 1; MBL1) and Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producer isolates (n = 1; KPC1), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 4; PA1–PA4) isolates collected from a range of hospitals throughout Ireland. In addition to the clinical isolates, reference American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) control strains were included in the study. Gram-positive controls included S. aureus ATCC 29213 and Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, and Gram-negative controls included Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031, and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 and PAO1. K. pneumoniae (ATCC 700603 and ATCC BAA-1705) were also included in the Gram-negative panel as ESBL-, KPC-positive resistant control stains, respectively.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing by disc diffusion

Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of clinical isolates were established through the qualitative Kirby–Bauer disc-diffusion method, performed according to European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines [45]. Selections of antimicrobial agents were chosen according to EUCAST recommendations for quality control and are displayed in Table 2. All antimicrobial discs were obtained from Oxoid™ Ltd (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Bacteria were stored on beads in cryogenic vials (Microbank™Cryovials) at – 80 °C and resuscitated on 5% blood agar 24 h before experiments. Three to five colonies were transferred from the agar plate to 5 mL of sterile saline (NaCl) solution, and adjusted until the turbidity matched that of a 0.5 McFarland standard (equivalent to a 1.5 × 108 CFU/mL). This was carried out for each individual strain. When the inoculum matched the 0.5 McFarland standard, a cotton swab was used to spread it on a Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA) plate. The plate was allowed to dry for 3–5 min before the corresponding antimicrobial disc (Table 2) was added to the plate with a sterile forceps. After incubation for 16–18 h at 37 °C, the zone of inhibition was determined by measuring the inhibition of growth around the disc at 3 points using a digital calliper. Studies were performed in triplicate, three independent times, and results are expressed as the mean measurement.

Table 2.

Disc-diffusion antimicrobial susceptibility testing using common antibacterial agents

| Strains | Antibiotic (Antibiotic class) | Disc content (µg) |

|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive panel | ||

|

S. aureus (ATCC 29213) Clinical isolates MRSA1–MRSA5 |

Cefoxitin (Cephalosporin) Ciprofloxacin (Fluoroquinolone) Gentamicin (Aminoglycosidase) Linezolid (Oxazolidinones) Rifampicin (Ansamycin) |

30 5 10 10 5 |

|

E. faecalis (ATCC 29212) Clinical isolates VRE1–VRE6 |

Ampicillin (Penicillin) Ciprofloxacin (Fluoroquinolone) Gentamicin (Aminoglycosidase) Vancomycin (Glycopeptide) Linezolid (Oxazolidinone) |

2 5 30 5 10 |

| Gram-negative panel | ||

|

E. coli (ATCC 25992) K. pneumoniae (ATCC 10031) K. pneumoniae (ATCC 700603—ESBL, ATCC BAA1705—KPC) Clinical isolates ESBL1, MBL1 and KPC1 |

Ampicillin (Penicillin) Cefotaxime (Cephalosporin) Ceftazidime (Cephalosporin) Erthapenem (Carbapenem) Gentamicin (Aminoglycosidase) |

10 5 10 10 10 |

|

P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27853, PAO1) Clinical isolates PA1–PA4 |

Piperacillin–tazobactam (Penicillin–β-lactamase inhibitor) Ceftazidime (Cephalosporin) Meropenem (Carbapenem) Ciprofloxacin (Fluoroquinolone) Gentamicin (Aminoglycoside) |

36 (30–6) 10 10 5 10 |

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

The antibacterial activity of the test complexes and the common antibiotics was also investigated using minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) antimicrobial susceptibility testing. The MIC of the complexes determined against clinical isolates and reference strains using the 96-well broth micro-dilution method outlined by EUCAST (2017b). A twofold dilution series of the test complexes was prepared in cation-adjusted Mueller–Hinton broth (CAMHB) and mixed with equal volumes (50 µL) of diluted bacteria in 96-well plates (Cruinn), generating a final test complex concentration range of 0.25–256 µg/mL. Each plate included a positive growth control (bacteria and broth) and a broth only no growth control. In addition to the metal complexes and the common antibiotic agents (Table 2), the MIC of the vehicle control (0.1% DMSO, 1% MeOH), starting materials (simple metal salts, phen and bridging ligands) was also determined (Table 1). The MIC was recorded as the lowest concentration to inhibit the visible growth (no turbidity observed) of the test strains following 16–18 h incubation at 37 °C. Studies were performed in triplicate, three independent times, and results are expressed as the mean MIC value.

Minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC)

The minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of the metal complexes against test isolates was determined by sub-culturing 5 μL of test dilution from each well in the MIC assay, which failed to show turbidity growth, onto antibiotic free MHA plates. Plates were incubated for a further 16–18 h at 37 °C. The MBCs was recorded as the lowest concentration of agent that prevented the growth (no growth observed) of an organism after subculture. Studies were performed in triplicate, three independent times, and results are expressed as the mean MBC value.

Fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC)

The antibacterial activity of individual metal–phen complexes in combination with the conventional common antibiotics was evaluated using the broth micro-dilution checkerboard assay [46]. Plates were prepared as described in Sect. 2.4. After incubation at 37 °C for 16–18 h, the fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index (FICI) for combinations of metal complexes with antibiotics was calculated according to the equation: FICI = FIC(metal complex) + FIC(antibiotic). Where, FIC(metal complex) = (MIC of metal complex in combination with antibiotic)/(MIC of metal complex alone) and FIC(antibiotic) = (MIC of antibiotics in combination with metal complex)/(MIC of antibiotic alone). With this method, FICI values were interpreted as synergy at a FIC index ≤ 0.5; additive at a FIC index > 0.5 to 1; indifference at a FIC index > 1– < 2; and antagonism at a FIC index ≥ 2 [47]. Studies were performed in triplicate, three independent times, and the results were expressed as mean FIC value.

Mutant selection

Mutants with decreased susceptibility to selected metal-tdda-phen complexes (metal = Mn(II), Cu(II) and Ag(I)) were generated by serial passage of P. aeruginosa PAO1 to increasing concentrations of the test complex, see Fig. 1 for a schematic overview of mutants. Briefly, conical flasks containing 10 mL of MHB with twofold increasing concentrations of either Mn-tdda-phen, Cu-tdda-phen, or Ag-tdda-phen were inoculated with an inoculum density equivalent to 1 × 107 CFU/mL of PAO1. Following overnight incubation at 37 °C aerated at 200 rpm, the MIC of the twofold dilution series was determined by the micro-dilution method. The conical flasks with the highest drug concentration that permitted growth (turbidity observed) were used to inoculate a series of tubes containing fresh MHB with twofold increasing concentrations of Mn-tdda-phen, Cu-tdda-phen, or Ag-tdda-phen adjusted to a starting concentration equivalent to 1 × 107 CFU/mL. The inoculated tubes were incubated overnight at 37 °C aerated at 200 rpm. Again, the MIC was recorded as the lowest concentration to inhibit the visible growth of the test strains, and the tube with growth at the highest drug concentration was used to prepare the inoculum for the following passage.

Fig. 1.

Schematic overview of reducing drug susceptibility of lead metal-tdda-phen complexes, Mn-tdda-phen, Cu-tdda-phen, and Ag-tdda-phen in reference strain P. aeruginosa PAO1 (PAO1_Mn, PAO1_Cu, PAO1_Ag, respectively). PAO1_NT refers to the control strain that did not receive any treatment

Whole-genome sequencing and analysis

The whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of mutant P. aeruginosa PAO1 strain (PAO1_NT, PAO1_Mn, PAO1_Cu, PAO1_Ag, respectively) were performed by MicrobesNG (http://www.microbesng.com). FASTQ files received from MicrobesNG were imported into Geneious Prime and mapped against reference genomes from the NCBI Nucleotide database. ‘PAO1, complete genome’ (Accession no. NC_002516) was used as the reference genome for the P. aeruginosa files. Variants were detected within Geneious Prime and exported as csv files. Settings used were taken from the WGS guide created by Gautam et al. [48], including the following; mapper—Bowtie 2, trim before mapping—do not trim, threshold: highest quality, threshold for sequences without quality: 95%, no coverage call.

The csv files were saved as xlsx files and opened with Microsoft Excel. Variants present in resistant strains of P. aeruginosa were compared to each other, and to the P. aeruginosa control using Ablebits add-in in Microsoft Excel. Any variants that were shared between at least two of the resistant strains and were not present in the control were noted. Any variants within the data that caused an amino acid (aa) change were investigated. BLAST searches were carried out to identify the possible function of any variant-containing hypothetical proteins. The data for this study have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) at EMBL–EBI under accession number PRJEB52838.

Statistics

All experiments were performed in triplicate, in three independent experimental sets. All data were statistically analysed using one-way analysis variance (ANOVA). The data were expressed as mean values. Data with P values smaller than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., USA).

Results

Susceptibility profile of all clinical isolates

Clinical isolates were first assessed against a range of commercial antibacterial agents commonly used within the clinic. The susceptibility profile of Gram-positive bacteria represented by S. aureus and Enterococcus species (E. faecium and E. faecalis) and Gram-negative bacteria, Enterobacterales (E. coli and K. pneumoniae) and P. aeruginosa are presented in Table 3. Each representative bacterial group consists of an ATCC control strain and clinical strains isolated from patients with bloodstream infections in Irish hospitals. The susceptibility profiles of these microorganisms were assessed in accordance to the EUCAST guidelines [45, 49]. The zones of inhibition for the ATCC control strains fell within the accepted ranges [50].

Table 3.

Susceptibility profile of control strains and clinical isolates against clinically used antibiotics, as determined by disc diffusion and classified according to EUCAST guidelines

| Species | Strain | Antibiotic (zone of inhibition as mm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive panel | ||||||

| Cefoxitin | Ciprofloxacin | Gentamicin | Linezolid | Rifampicin | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | ATCC 29213 | 27 (S) | 24 (S) | 21 (S) | 24 (S) | 33 (S) |

| MRSA1 | 10 (R) | 0 (R) | 8 (R) | 23 (S) | 27 (S) | |

| MRSA2 | 13 (R) | 0 (R) | 8 (R) | 22 (S) | 28 (S) | |

| MRSA3 | 11 (R) | 0 (R) | 19 (S) | 24 (S) | 27 (S) | |

| MRSA4 | 15 (R) | 0 (R) | 21 (S) | 24 (S) | 27 (S) | |

| MRSA5 | 13 (R) | 0 (R) | 20 (S) | 24 (S) | 28 (S) | |

| Vancomycin | Ciprofloxacin | Gentamicin | Linezolid | Ampicillin | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus faecium | ATCC 29212 | 24 (S) | 25 (S) | 20 (S) | 23 (S) | 24 (S) |

| VRE1 | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | |

| VRE2 | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 13 (R) | 0 (R) | |

| VRE3 | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 11 (R) | 0 (R) | |

| VRE4 | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 13 (R) | 0 (R) | |

| VRE5 | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 11 (R) | 0 (R) | |

| VRE6 | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 10 (R) | 0 (R) |

| Gram-negative panel | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ertapenem | Ceftazidime | Cefotaxime | Gentamicin | Ampicillin | ||

| Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae | ATCC 25922 | 32 (S) | 26 (S) | 27 (S) | 21 (S) | 20 (S) |

| ATCC 10031 | 27 (S) | 13 (R) | 14 (R) | 13 (R) | 10 (R) | |

| ATCC 700603 | 26 (S) | 8 (R) | 15 (R) | 12 (R) | 0 (R) | |

| ESBL1 | 25 (S) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | |

| MBL1 | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | |

| ATCC BAA1705 | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 17 (S) | 0 (R) | |

| KPC1 | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | |

| Ceftazidime | Ciprofloxacin | Gentamicin | Meropenem | Piperacillin–Tazobactam | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ATCC 27853 | 25 (S) | 29 (S) | 20 (S) | 27 (S) | 25 (S) |

| PAO1 | 15 (S) | 25 (S) | 18 (S) | 18 (S) | 25 (S) | |

| PA1 | 20 (S) | 24 (S) | 13 (R) | 25 (S) | 21 (S) | |

| PA2 | 16 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | |

| PA3 | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 17 (R) | 0 (R) | |

| PA4 | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | 9 (R) | 11 (R) |

Zones of inhibition are presented in mm. Resistant (R; Red); Susceptible (S; Green)

All five clinical MRSA strains (MRSA1–MRSA5) were resistant to cefoxitin and ciprofloxacin, while two (MRSA1 and MRSA2) isolates were also resistant to gentamicin (Table 2). The clinical, vancomycin-resistant Enterococci strains (VRE1–VRE6) demonstrated resistance to all of the standard antibacterial agents. Representative Gram-negative sub-panels included the Enterobacterales panel encompassed by extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing strains, ATCC 700603 (K. pneumoniae) and clinical isolate ESBL1, metallo-β-lactamase (MBL)-producing clinical isolate MBL1, and K. pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing strain ATCC BAA1705 and clinical isolate KPC1. As expected, the ESBL + strain demonstrated resistance to all β-lactams tested but remained susceptible to the carbapenem. Similarly, both MBL + and KPC + CRE test strains also demonstrated the expected antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) profiles with resistance expressed to all β-lactams including the carbapenem, a last resort drug. The P. aeruginosa group incorporated four clinical isolates (PA1–PA4). PA1 was susceptible to all test antibiotics except gentamicin, while PA2, PA3 and PA4 were resistant to all examined agents.

Based on the criteria released by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the bacterial panel is comprised of several multidrug-resistant (MDR) isolates [51].

Antibacterial testing of metal complexes

Once the susceptibility profiles of the clinical isolates were established, in vitro studies were carried out to determine the antibacterial activity of the metal–dicarboxylate–phen complexes against the Gram-positive and Gram-negative panels (Figs. 2 and 3, respectively). Quantitative serial broth dilutions of each complex were performed so as to establish the MIC and MBC values. In addition, the simple metal salts, metal-free ligands and antibiotics were included, along with all of the respective metal-free dicarboxylic acids, butanedioic acid (bdaH2), pentanedioic acid (pdaH2), hexanedioic acid (hxdaH2), heptanedioic acid (hpdaH2), octanedioic acid (odaH2), undecanoic acid (uddaH2), phthalic acid (phH2) and 3,6,9-trioxaundecanedioic acid (tddaH2). Ciprofloxacin and gentamicin were used as controls for the Gram-positive panel as they are well-known broad-spectrum antibiotics that have different mechanisms of activity, inhibition of DNA synthesis (ciprofloxacin) and protein synthesis (gentamicin). Gentamicin and meropenem (inhibition of cell wall synthesis) were utilised for the Gram-negative panel.

Fig. 2.

Gram-positive panel. Heat map displaying the mean MIC of metal complexes, grouped according to their metal centre and antibiotic controls (ciprofloxacin and gentamicin) for (A) S. aureus, control strain ATCC 29213, and clinical isolates, MRSA1–MRSA5, and (B) Enterococcus spp, control strain ATCC 29212 (E. faecalis) and clinical isolates, VRE1–VRE6. Graph tiles that are white without a value, did not have a MIC that fell within the tested range (> 256 µg/mL). Detail of the concentration range, and its relation to colour, is displayed in the figure legend

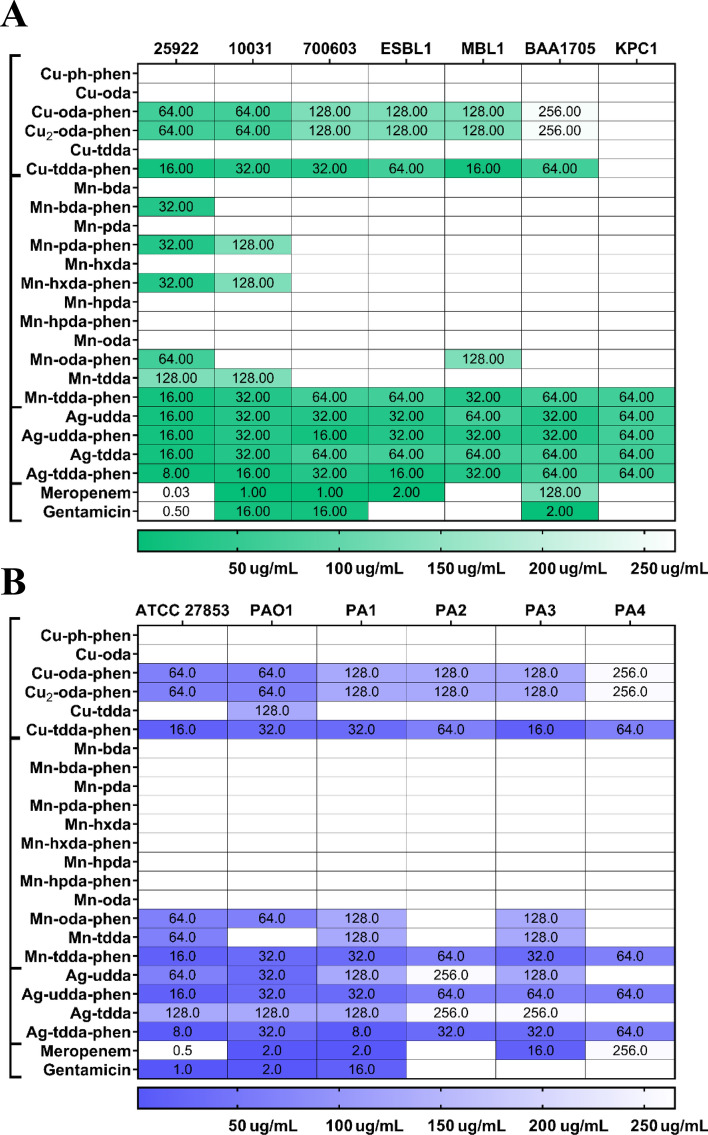

Fig. 3.

Gram-negative panel. Heat map displaying the mean MIC values of metal complexes, grouped according to their metal centre and also antibiotic controls (meropenem and gentamicin) for (A) Enterobacterales control strain ATCC 29213 (E. coli), ATCC 10031 (K. pneumoniae), ATCC 700603 (ESBL +), ATCC BAA1705 (KPC +) and clinical isolates ESBL1, MBL1 and KPC1, and (B) Pseudomonas aeruginosa, control strain ATCC 27853 and PAO1, and clinical isolates PA1–PA4. Graph tiles that are white without a value, did not have a MIC value that fell within the test range (> 256 µg/mL). Details of the concentration range, and its relation to colour, is displayed in the figure legend

Gram-positive panel

Staphylococcus aureus

The MIC values (µg/mL) of the metal complexes and commonly used antibiotics against S. aureus strains are displayed in Fig. 2A. With the exception of Mn-hpda-phen, metal complexes containing the phen ligand demonstrated a higher level of antibacterial activity against both the control strain (ATCC 29213) and the clinical isolates (MRSA1–MRSA5) in comparison with their non-phen precursors. The MIC value for gentamicin was 1 µg/mL (1.74 µM) for ATCC 29,213 (S. aureus) and MRSA3–MRSA5 isolates which interprets them as being susceptible to the antibiotic according to EUCAST breakpoints. Ciprofloxacin also had an MIC value of 1 µg/mL (3.02 µM) against ATCC 29213, while all of the clinical isolates were resistant to the antibiotic (> 256 µg/mL) (> 772 µM). The Cu(II)-phen complexes, Cu-ph-phen (2.25 µM), Cu-oda-phen (1.35 µM), Cu2-oda-phen (0.76 µM) and Cu-tdda-phen (1.34 µM), and Mn(II) complex Mn-tdda-phen (1.36 µM) also produced a MIC of 1 µg/mL against ATCC 29,213. The simple salts, CuCl2 and MnCl2, had no appreciable effects against the strain (Table S 1), and although phen alone was able to inhibit growth, it was not as effective as the Cu(II) and Mn(I)-phen complexes. Moreover, none of the metal-free dicarboxylic acids demonstrated any inhibitory effects below a concentration of 256 µg/mL (data not shown), and this is in agreement with previously reported data [52]. This suggests that the activity of metal-phen complexes are a consequence of the whole complex rather than its separate constituent parts. However, activity is not necessarily dependent on the number of coordinated phen ligands present per complex. For instance, Cu-oda-phen, Cu-tdda-phen and Mn-tdda-phen contain two phen ligands, and Cu2-oda-phen contains four ligands. Mn-oda-phen has the greatest amount of phen ligands attached (eight) but had an MIC value of 32 µg/mL (104 µM) against ATCC 29213. A sub-set of these complexes (Mn-oda-phen, Mn-tdda-phen and Cu2-oda-phen) were previously examined against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and a similar observation was made [53].

Cu-tdda-phen had an MBC value of 4 µg/mL (5.38 µM) which matched the MBC of gentamicin (6.95 µM). Antibiotics are usually regarded as bactericidal if the MBC is no more than four times the MIC value [54], so in this regard the majority of Cu-tdda-phen MBCs are four times the established MIC value (Table S 1). Strains resistant to gentamicin had an MIC value of 64 µg/mL (100 µM) (MRSA1) and 128 µg/mL (500 µM) (MRSA2), while Mn-tdda-phen (MIC of 1 µg/mL/1.36 µM and 8 µg/mL/10.9 µM against MRSA1 and MRSA2, respectively) and Cu-tdda-phen required a lower concentration to inhibit growth of the isolates (MIC of 8 µg/mL/10.8 µM against both). The similar activities of Cu-tdda-phen and Mn-tdda-phen suggests that, in these particular cases, antimicrobial activity is independent of the nature of the central transition metal dication. This supports previous observations that, in certain instances, activity can be independent of the metal present [14]. However, the metal complexes that contain an Ag(I) nucleus behaved differently to their Cu(II) and Mn(II) counterparts. Ag-tdda-phen (6.65–13.3 µM) and Ag-udda-phen (7.81–15.6 µM) had a MIC range of 8–16 µg/mL across all of the test isolates. Their non-phen precursors, Ag-tdda (67 µM) and Ag-udda (74 µM), maintained activity across all strains at the administered concentration of 32 µg/mL. From previous studies we know that the silver(I)-dicarboxylate precursors are far less stable in aqueous solution than their silver(I)-dicarboxylate-phen derivatives, whereby they rapidly decompose over several days when left standing in direct sunlight [40]. The silver(I)-dicarboxylate-phen derivatives studied were found to be completely photo-stable up to 8 months of exposure to direct sunlight in aqueous solution (confirmed by clarity of colour, lack of any precipitation and UV–Vis spectrophotometry) [40]. In that study cyclic voltammetric (CV) analysis demonstrated that the silver(I)-dicarboxylate precursors studied behaved in a similar fashion to the redox inactive silver acetate resulting in a large silver-stripping peak in the CV profile. The silver(I)-dicarboxylate-phen derivatives on the other hand were found to be redox active and producing only a slight silver stripping peak. Furthermore, the silver(I)-dicarboxylate-phen derivatives were found to have avid DNA binding capability and DNA viscosity studies demonstrated that they exhibit far greater DNA-intercalating ability than ethidium bromide which is the benchmark for comparison of DNA intercalation.

Therefore, based on their relative instability in aqueous solution and the electrochemical analysis, it is postulated that the Ag-udda and the Ag-tdda complexes exerted their toxicity through the release of Ag(I) ions from the complex into the growth medium. This is substantiated by the observation that the simple metal salt, AgNO3, exerted similar activity (MIC value 4–64 µg/mL) (Table S 1). This is not surprising as silver is widely reported to have strong antibacterial properties, particularly against S. aureus with a multi-target mode of action and the ability to overcome antibiotic resistance [51]. The Ag-udda-phen and the Ag-tdda-phen derivatives on the other hand are stable in aqueous solution, redox active and their antibacterial activities are superior to those observed for their non-phen precursors, suggesting that their mechanism of antibacterial activity is significantly different to that of their non-phen precursors, although slow release of silver ions may be part of their multimodal mechanism of action. The DNA binding and intercalating studies previously reported provide further evidence for this differential in their potential modes of action.

Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis

The MIC values of the metal complexes and commonly used antibiotics against Enteroccous spp are displayed in Fig. 2B. The control antibiotics ciprofloxacin and gentamicin had an MIC of 1 µg/mL (3.02 µM) and 8 µg/mL (18.3 µM), respectively, against the control strain ATCC 29212, which fell within the recommended values provided by EUCAST. In contrast, all of the clinical isolates had MICs greater than the highest concentration of antibiotic used (256 µg/mL), thus classifying them as being resistant to the antibacterial agents. Fewer metal complexes exercised antibacterial action against the Enterococci group of isolates. Although the Cu(II)-phen complexes inhibited the growth of all strains considerably higher concentrations were required (16–256 µg/mL) (12.2–443 µM). Of the Cu(II) and Mn(II) panel, Cu-tdda-phen and Mn-tdda-phen were the most active. Both complexes established MICs of 16–64 µg/mL (21.5–87 µM) across the bacterial strains and were superior to the control antibiotics, ciprofloxacin and gentamicin (> 256 µg/mL). Moreover, the MBCs for Cu-tdda-phen ranged from 32 µg/mL (43 µM) to 128 µg/mL (172 µM) (Table S 2), demonstrating that not only was the complex able to inhibit the growth of highly resistant microorganisms at lower concentrations than the control antibiotics, but was also able kill them at concentrations below the MICs of the antibiotics. As with the MRSA isolates, the Ag(I) complexes behaved differently to the other metal complexes. Ag-tdda-phen (6.65–13.3 µM) and Ag-udda-phen (7.81–15.6 µM) had a MIC range of 8–16 µg/mL across all strains, while their non-phen precursors, Ag-tdda (67 µM) and Ag-udda (74 µM), respectively, required 32 µg/mL to inhibit growth of the bacterial isolates. The MBCs of the phen-containing complexes, Ag-tdda-phen (26.6–53.2 µM) and Ag-udda-phen (31.2–62.5 µM), were 32–64 µg/mL and their non-phen complexes had an MBC value of 128 µg/mL (271–297 µM). The simple metal salt, AgNO3, inhibited all of the bacterial isolates at a concentration of 4 µg/mL, outperforming the Ag(I) complexes. However, the Ag(I) complexes were able to kill the same bacteria at lower concentrations. Metal-free phen and the dicarboxylic acids did not have MBC values within the test concentration range, and therefore, it is postulated that coordination of the ligands to the metal enhances the bactericidal effect.

Gram-negative panel

Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae

The Enterobacterales panel are represented by susceptible control strains ATCC 25922 (E. coli) and ATCC 10031 (K. pneumoniae), resistant control strains ATCC 700603 (K. pneumoniae extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producer) and ATCC BAA1705 (K. pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producer), and clinical isolates ESBL producer (ESBL1) a metallo-β-lactamase (MBL)-producer (MBL1) and a KPC producer (KPC1). Figure 3A highlights that a reduced selection of complexes retained activity when screened against Gram-negative bacteria and, overall, complexes containing a phen ligand had heightened activity. Of the Cu(II) complexes, Cu2-oda-phen (48.7–194 µM) and Cu-oda-phen (80.5–345 µM) had an MIC value in the range 64–256 µg/mL, while Cu-ph-phen was essentially inactive against the Gram-negative panel. Gram-negative bacteria, unlike Gram-positive bacteria, possess a protective outer membrane (OM) which can impede access of some antibacterial agents and this can be a limiting factor in a chemotherapeutic treatment protocol [55]. Cu-tdda-phen (MICs = 16–64 µg/mL) (21.5–86 µM), Mn-tdda-phen (MIC = 16–128 µg/mL) (21.8–174 µM) and Ag-tdda-phen (MIC = 8–64 µg/mL) (6.7–53.2 µM) were the most active agents from within each representative group. The Ag(I) complexes, Ag-udda, Ag-udda-phen and Ag-tdda, produced a similar toxicity profile as the silver salt, AgNO3 (Table S 3), across all strains, again suggesting that the binuclear silver complexes may be exerting activity by releasing Ag(I) ions into solution. Ag-tdda-phen generated an MBC value (64–128 µg/mL) twice that of its MIC value (32–64 µg/mL) across the clinical isolates apart from ESBL1 that required 4 times the MIC value (16 µg/mL) to eliminate the isolate. Transmission election microscopy observation of AgNO3 treated E. coli identified morphological and structural changes as well as enhanced permeability in the bacterial cell envelope [56] suggesting that the Ag(I) complexes are exerting their antibacterial activity in this manner.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

When investigating the MIC of the metal complexes (Fig. 3B), Cu-tdda-phen (21.5–86 µM) and Mn-tdda-phen (21.8–87 µM) were decidedly the most active complexes from those that harbour a Cu(II) or Mn(II) nucleus. A related activity pattern was observed through the test strains, with ATCC 27,853 having an MIC value of 16 µg/mL (21.5 µM and 21.8 µM, respectively) for both chelates and an MBC value of 32 µg/mL (43 µM and 43.5 µM, respectively). For the Cu(II) and Mn(II) tdda-phen complexes to inhibit growth of the clinical isolates PA2 and PA4, an MIC value of 16 µg/mL was necessary, whereas both of these bacterial strains were resistant to the control antibiotics, meropenem (MIC = > 256 µg/mL, > 585 µM) and gentamicin (MIC = > 256 µg/mL, 444 µM). Ag-tdda-phen presented with an MIC value of 8 µg/mL (6.6 µM) for ATCC 27,853 and PA1, and 32–64 µg/mL (26.6–53.2 µM) across the remaining strains. The non-phen derivative, Ag-tdda, had an MIC value of 128–256 µg/mL (106–213 µM) for all of the clinical strains, indicating that the inclusion of the phen ligand caused a more potent effect.

Combination effects of selected clinical isolates with lead metal-tdda-phen complexes and antibiotics

Combination therapy is a method for restoring the clinical efficacy of antibiotics and avoiding the development of drug resistance in the clinic. Therefore, combinatorial testing of elected metal-tdda-phen complexes and control antibiotics was used to determine the interaction and potency of the combined treatments compared to their individual activities against the selected clinical isolates. Representative isolates were chosen from each genera, particularly strains that had a more extensive resistance profile (Table 3). They were as follows: S. aureus clinical isolates, MRSA1 and MRSA2, Enterococci isolates, VRE1 and VRE6, Enterobacterales isolates, ATCC 700603, MBL1, ESBL1, ATCC BAA1705 and KPC1, and P. aeruginosa isolates PA2 and PA4. Selected antibacterial agents were unique to the group of bacteria, for instance, antibiotics chosen for VRE isolates were vancomycin and linezolid. Finally, a representative metal complex from each different metal-containing series was selected including the very active tdda-phen family, Cu-tdda-phen, Mn-tdda-phen and Ag-tdda-phen. When drugs are combined, their effects on bacterial cells may be amplified, slightly enhanced, weakened, or have no effect at all, so the drugs may show synergistic, additive, indifferent or antagonistic interactions, respectively. On the basis of their FIC index, each combination was categorized as synergistic (≤ 0.5), additive (> 0.5 to 1), indifferent (> 1 to < 2) or antagonistic (≥ 2), according to the EUCAST guidelines [47]. Ideally, for the combination of metal complex with antibiotic, a synergistic was desired.

Combination effects in selected Gram-positive isolates

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

Ciprofloxacin is a bactericidal antibiotic of the fluoroquinolone class that target DNA replication [57] and gentamicin is a clinically significant aminoglycoside antibiotic that inhibits protein synthesis [58]. All three metal-tdda-phen complexes in combination with ciprofloxacin produced an indifferent effect against the clinical isolates, MRSA1 and MRSA2 (Table S 5). This means that the inhibitory effect of the combined agents is the same as that of the more active drug alone, this being the metal-tdda-phen complexes. When the complexes were co-administered with gentamicin, the combination was synergistic, in terms of the FICI value. In this context, the inhibitory effect against the bacterium in the combination was more potent than that of the individual agents alone.

Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE)

Vancomycin, a glycopeptide, exerts its bactericidal effect by binding to d-alanyl-d-alanine residues of the bacterial cell wall and preventing polymerization of peptidoglycans [59]. Linezolid is the first synthetic oxazolidinone antibiotic with a unique mechanism of action as it appears to block initiation of protein production [60]. All combinations of vancomycin or linezolid with the three metal-tdda-phen complexes against the clinical isolates, VRE1 and VRE6, produced indifferent effects (Table S 6).

Combination effects in Gram-negative strains

Enterobacterales isolates

Ceftazidime, is a third-generation cephalosporin antibiotic that exerts its bactericidal action by inhibiting enzymes responsible for cell wall synthesis primarily through penicillin-binding protein 3 (PBP3) [61]. Meropenem is a broad-spectrum antibacterial agent of the carbapenem class that inhibits cell wall synthesis also through binding to PBP targets [62]. The strains representing the test Enterobacterales group were ATCC 700603, ATCC BAA1705, ESBL1, MBL1 and KPC1 isolates (Table S 7). Co-exposure of ceftazidime with Cu-tdda-phen or Mn-tdda-phen, and the combinations of all of the metal-tdda-phen complexes with meropenem, caused an indifferent effect with all strains (the inhibitory rate of the combined agents was the same as that of the more active drug alone, that being the metal-tdda-phen complex). The addition of Ag-tdda-phen to ceftazidime also had an indifferent effect against ESBL1 and KPC1 strains. However, the same combination against ATCC 700603, MBL1 and ATCC BAA1705 produced an additive effect (combination of agents did not increase the inhibitory effect to an extent that was better than that of administering the concentration of the more active single drug alone). The same effect was observed with the combinations of Cu-tdda-phen, Mn-tdda-phen and Ag-tdda-phen with gentamicin against ESBL1. There have been numerous reports of simple silver or silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) restoring activity of ineffective antibiotics against multidrug-resistant strains [63–65]. One report stated the combination of AgNPs with ceftazidime were synergistic against 62.50% of examined ESBL + K. pneumoniae isolates, and confirming the inhibition of β-lactamase enzymes in isolates exposed to AgNPs [66].

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

When the clinical isolates PA2 and PA4 were tested with the metal-tdda-phen complexes in tandem with meropenem and gentamicin the results were indifferent and synergistic, respectively (Table S 8).

Whole-genome sequencing of Gram-negative Pseudomonas aeruginosa for resistance properties to selected metal-tdda-phen complexes

Wild type P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 was exposed to sub-lethal concentrations of lead metal-tdda-phen complexes so as to induce resistance properties (Fig. 1). This generated distinct strains that were denoted as PAO1_Mn, PAO1_Cu, and PAO1_Ag, when exposed to Mn-tdda-phen, Cu-tdda-phen and Ag-tdda-phen, respectively. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) was performed on all strains and the genomes were subsequently analyzed using the bioinformatics programme ‘Geneious Prime’.

Various mutations were identified upon comparing the untreated control strain (PAO1_NT) to the metal-tdda-phen-treated strains (PAO1_Cu, PAO1_Mn and PAO1_Ag) (Table S 9). One variant identified between all metal-tdda-phen exposed strains was situated in an unnamed gene that encodes for a hypothetical protein that is linked to a carbon–nitrogen hydrolase containing protein. A BLAST search and computational predictions suggest that the protein exhibits N-carbamoylputresceine amidase activity [67]. This protein is a crucial component in the polyamine biosynthetic pathway, indicating that resistance to the metal-tdda-phen complexes may be acquired through alterations in the activity levels of this pathway. Mutations in agmatine deiminase and N-carbamoylputrescine amidase can directly influence the rate at which polyamines are produced. Arginine deiminase, GatB of the aspartyl/glutamyl-tRNA amidotransferase complex and ɣ-glutamyl phosphate reductase can all indirectly contribute to an altered polyamine biosynthetic rate [68]. The remaining mutations (Table S 9) were aligned to specific pathways and mechanisms, as discussed below.

Mutations associated with cellular respiration

Genome analysis suggest that alterations to energy metabolism pathways contributed to the development of bacterial resistance. Amino acid altering single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) occurred in various unspecified oxidoreductases and known oxidases and dehydrogenases in metal-tdda-phen-treated strains. These enzymes are heavily involved in cellular respiration [69, 70]. In situations, where electron acceptors in oxidative phosphorylation are unavailable, the protein D-lactate dehydrogenase may act as a temporary electron sink [71]. In addition, recent studies have demonstrated the ability of D-lactate dehydrogenase to act as an electron transferring agent, transporting electrons from NADH to quinones present in the plasma membrane [72]. A mutation in the gene encoding for D-lactate dehydrogenase, ldhA, was identified in the analysis. In addition, a SNP was identified in an unspecified cytochrome c oxidase which acts as a terminal electron acceptor but also has other functions in bacteria such as promoting virulence and biofilm growth [73]. Both of these mutations indicate that cellular respiration was affected by the metal-tdda-phen complexes.

Mutations associated with polyamine biosynthetic pathway

Amino acid substitutions were identified in agmatine deiminase and N-carbamoylputrescine amidase (CPA), respectively. An inhibitory mutation in agmatine deiminase would prevent the formation of N-carbamoylputrescine, and therefore, no mutation would be required in CPA as it would not have a substrate on which to act. Similarly, the arginine biosynthetic pathway involves the conversion of glutamate into arginine through a series of consecutive enzymatic reactions [74]. Mutations were identified in arginine deiminase, GatB of the aspartyl/glutamyl-tRNA amidotransferase complex and ɣ-glutamyl phosphate reductase. Arginine deiminase and ɣ-glutamyl phosphate reductase catalyse the conversion of arginine to citrulline and N-acetyl-glutamyl-5-phosphate to N–acetyl-glutamyl-5-semialdehyde, respectively [74]. These reactions are essential steps in the arginine biosynthetic pathway. GatB is involved in the synthesis of glutamine which is a precursor to glutamate [75]. Amino acid substitutions in each of these enzymes further support the previous postulation that an enhanced rate of polyamine biosynthesis could contribute to the resistance of the PAO1 strain to the three metal-tdda-phen complexes.

Mutations associated with virulence factors

Bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) is the principle second messenger involved in the regulation of cell cycle, differentiation, virulence, motility, biofilm formation and dispersion [76, 77]. It is synthesized from two GTP molecules by diguanylate cyclases (DGC), and is degraded by phosphodiesterases (PDE). Variants in PDE, PprA, WspC, RhlA and alginate lyases were identified in metal-tdda-phen-treated strains, suggesting that changes occurred in the biofilm life cycle. In addition, WspC is a methyltransferase that promotes the activation of the Wsp pathway. This pathway is involved in the regulation of c-di-GMP concentration [78, 79]. Similarly, the gene pprA encodes the histidine kinase sensor, PprA, for the two-component system PprA–PprB. This system is associated with biofilm formation during high-stress conditions. PprA is responsible for the activation of the two-component system and a mutation in pprA could indicate that the activity status of the system was altered as a resistance strategy toward the metal-tdda-phen complexes [80, 81]. A mutation in rhlA was identified, which is a gene that codes for rhamnosyltransferase subunit A that acts as a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of rhamnolipid, a secondary metabolite that is important for the maintenance of mature biofilms [82]. We have previously reported the anti-biofilm activity of these metal-tdda-phen complexes against P. aeruginosa strains, isolated from Cystic Fibrosis patients, in both in vitro [22] and in vivo scenarios [83]. A SNP in an alginate lyase domain-containing protein was also observed in both PAO1_Cu and PAO1_Mn strains. This mutation resulted in an arginine residue being substituted for a glutamine residue. Alginate is a critical component of biofilms, providing the thick mucoid consistency that facilitates protection against the environment and stressors. Alginate lyase proteins degrade alginate and this mutation may reduce the enzyme's efficiency, allowing alginate levels to rise and promoting biofilm formation [84, 85].

SNPs were identified in other virulence factors such as nalC, which is a transcriptional regulator responsible for the control of the mexAB-oprM operon [86], encoding the primary efflux pump of P. aeruginosa, MexAB–OprM [87]. The MexAB–OprM system is responsible for the resistance to quinolones, macrolides, chloramphenicol, tetracyclines, lincomycin, and β-lactam antibiotics [88]. A mutation in this protein resulted in an arginine residue replacing a serine residue. Another notable variant was present in XqhA, a protein that increases specificity of the type II secretion system (T2SS) [89]. T2SS is known to secrete PlcH, a hemolytic toxin in which another mutation was identified causing the substitution of a serine with an alanine [90]. Finally, a mutation resulting in the replacement of an asparagine with a lysine occurred in the highly conserved bacterial protein, ClpB. This protein is vital in the disaggregation of proteins during high stress conditions [91], suggesting that the metal-tdda-phen complexes may have triggered protein aggregation within the bacterial cell.

Discussion

Here, we investigated the antibacterial capabilities of copper(II), manganese(II), and silver(I) complexes containing dicarboxylate ligands and phen in panels of clinical isolates derived from Irish hospitals and further investigated the potential resistance mechanisms by whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of our lead complexes in the representative Gram-negative organism, P. aeruginosa. With Gram-positive and -negative bacteria, their distinction lies in the composition of the cell envelope. The scaffold of the Gram-positive cell wall consists of a thick layer of peptidoglycan polymer embedded with teichoic and lipoteichoic acids that are anchored to the cell membrane. Teichoic acids are long anionic glycopolymers that bind cations contributing to bacterial cell surface charge and hydrophobicity, which in turn affects the interaction of antibiotics and host defences [92]. In contrast, and in the absence of teichoic acid, the Gram-negative cell wall consists of a thin layer of peptidoglycan; however, the outer membrane encloses this. This layer is effectively a second lipid bilayer containing amphiphilic lipopolysaccharide (LPS), phospholipids and outer membrane proteins [93]. Porins are β-barrel structures that form channels to orchestrate the movement of small hydrophilic molecules across the outer membrane [94], and efflux pumps are membrane-bound proteins which are responsible for the extrusion of a variety of solutes. Therefore, the outer membrane is a very effective and selective permeability barrier and a significant obstacle in the development of antibacterial agents that are effective against Gram-negative bacteria [55, 95]. In addition to this intrinsic resistance, acquired resistance is developing rapidly, creating a further impediment in the treatment of diseases caused by these pathogens [96–98].

Our present investigations have shown that, overall, the metal complexes that incorporate the phen ligand demonstrated superior antibacterial toxicity when compared to their non-phen precursors, metal-free phen, metal-free dicarboxylic acids or simple metal salts. The greater activity profiles of metal-phen complexes or metal-phendione complexes (phendione is a derivative of phen), in comparison with their non phen analogues has previously been reported against a range of microorganisms [23, 24, 30, 31, 53]. Moreover, the metal-phen complexes that contained the 3,6,9-trioxaundecanedioate (tdda) bridging dianionic ligand maintained their potency, to varying degrees, across both the Gram–positive and Gram–negative panels (Figs. 2 and 3). The tdda ligand enhances the water solubility of the metal complexes, strengthening their hydrophilicity and potentially increasing their uptake into the bacterial cell and thus their subsequent antibacterial action [99, 100]. Although generally the inclusion of the phen ligand in the complex formulations is key to their antibacterial action, the general exception to this was the Ag(I) complexes which were found to be active in both their phen and non-phen containing forms. Ag(I) compounds have well-documented multimodal bactericidal properties, displaying a broad spectrum of activity across both classes of bacteria [101, 102]. Ag(I) ions interact with the bacterial cell envelope and destabilize the membrane [103, 104], couple with nucleic acids and proteins [105], and inhibit metabolic pathways [106, 107]. Although the Ag(I) ion is generally not regarded as being redox active, the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) also attributes to its antibacterial activity [13, 101]. However, it is thought that the production of ROS indirectly occurs through the perturbation of the respiratory electron transfer chain [108], Fenton chemistry following destabilization of Fe–S clusters or displacement of iron [109] and inhibition of anti-ROS defences by thiol–silver bond formation [110]. The antibacterial potential of Ag(I) is influenced by the composition of the cell wall, the thick negatively charged peptidoglycan layer in Gram-positive bacteria attracts/binds the metal cations and retards their entry [101, 111]. The complexation of metal ions to a hydrophobic chelating ligand, such as phen, encases the cations in a hydrophobic sleeve and enables their penetration through the cell wall and membrane of a bacterium, thus presenting the complex to internal target biomolecules which ultimately inhibits cell growth or even triggers cell death [15]. The heightened activity of phen-containing Ag(I) complexes, compared to their non-phen precursors, was evident in the present work with both the Gram-positive (Fig. 2) and Gram-negative panels (Fig. 3). Ag(I) complexed to phen or a phen-type ligand (e.g., phendione) have presented with additional routes in which they exert their toxicity against microorganisms, such as interacting with double stranded DNA [36] or suppressing virulence [35]. Cu(II) and Mn(II)-phen complexes have been reported to be avid producers of ROS [112] which is thought to cause cell membrane damage and thiol depletion. Oxidative and thiol stress promotes the release metal ions (Fe, Zn and Cu) from metalloproteins, increasing their intracellular concentration initiating Fenton-type chemistry which then stimulates further ROS generation [113]. This, coupled with intercalation of the complexes with bacterial DNA, would cause deformation and cleavage of the nucleic acid [53, 112, 114] producing cascade effects that would eventually lead to bacterial cell death. These previous observations substantiate the hypothesis that the current metal-tdda-phen complexes, producing high intracellular levels of ROS, affect cellular respiration (Table S 9). Various mutations were detected in the mutant genome of the metal-tdda-phen-treated P. aeruginosa representative strain, PAO1, causing amino acid changes within proteins involved in the polyamine biosynthetic pathway. Polyamines have demonstrated the ability to reduce oxidative damage caused by ROS [115]. As previously mentioned, Cu(II), Mn(II) and Ag(I)-phen complexes generate free radicals which are highly reactive and unstable. Polyamines act as ROS scavengers, stabilizing ROS and preventing ROS-induced damage to DNA, lipids and proteins. Recent findings suggest that these organic cations may also upregulate genes associated with the enzymatic degradation of ROS, such as catalases and superoxide dismutases. Superoxide dismutases have the ability to degrade superoxide radicals, while catalases can degrade hydrogen peroxide [116, 117].

Due to the increasing rate of AMR, metals and metal complexes have not only been investigated as alternatives to antibiotics but also as adjuvants. There have been numerous reports on the capacity of metals or metal-bearing compounds to synergise and potentiate antibiotics within both in vitro and in vivo models [56, 118–121]. Within the present study, all three metal-tdda-phen complexes potentiated gentamicin (an aminoglycoside) activity in clinical isolates of MRSA, EBSL and P. aeruginosa in terms of their fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index. Aminoglycosides are bactericidal antibiotics that inhibit protein synthesis by binding with a high affinity to the aminoacyl-tRNA site (A site) within the 30S ribosomal subunit, thereby inhibiting the translation process and producing truncated proteins and affecting the cell wall composition. This increases membrane permeability and subsequently heightens uptake of the drug [122]. In studies using strains of E. coli, Herisse et al. reported a tenfold increase in antimicrobial activity of aminoglycosides (gentamicin, tobramycin, kanamycin, and streptomycin) when co-administered with AgNO3 [118]. Aminoglycosides cross the cell membrane via proton motive forces, and the Ag(I) ion enhanced their toxicity by acting independently of this process. Morones-Ramirez et al. also reported the synergistic combination of AgNO3 with β-lactams, aminoglycosides, and quinolones against E. coli, and they suggested that this was due to intensified ROS production [56]. One or both of the above-mentioned mechanisms could also be the reason why the present metal-tdda-phen complexes enhanced the activity of gentamicin, and this warrants further investigation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, of the spectrum of metal complexes assessed those incorporating the phen ligand had superior activity to their non-phen derivatives. In addition, the three metal-phen complexes incorporating the 3,6,9-trioxaundecanedioate (tdda) ligand broadly maintained activity across the bacterial panel of both classes, and these complexes also re-sensitized, gentamicin-resistant isolates to the antibiotic. The genomes of mutant P. aeruginosa strains treated to the metal-tdda-phen (metal = Cu(II), Mn(II), and Ag(I)) complexes eluded to novel and potentially multimodal mechanisms by which the test complexes exert their toxicity. The encouraging results emanating from the current study suggests that future pharmacological, toxicological and pharmacokinetic investigations are warranted for the metal-tdda-phen complexes.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. However, data can be stored on the TUDublin central repository Arrow.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Theuretzbacher U, Bush K, Harbarth S, et al. Critical analysis of antibacterial agents in clinical development. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18:286–298. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-0340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler M, Gigante V, Sati H, et al. Analysis of the clinical pipeline of treatments for drug-resistant bacterial infections: despite progress, more action is needed. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022;66:1–39. doi: 10.1128/aac.01991-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Destoumieux-Garzón D, Mavingui P, Boetsch G, et al. The one health concept: 10 years old and a long road ahead. Front Vet Sci. 2018;5:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2018.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cassini A, Högberg LD, Plachouras D, et al. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European economic area in 2015: a population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:56–66. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30605-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Theuretzbacher U, Gottwalt S, Beyer P, et al. Analysis of the clinical antibacterial and antituberculosis pipeline. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:40–50. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30513-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020) Antimicrobial resistance. tackling the burden in the European union. Eur Cent Dis Prev Control:1–20.

- 7.O'Neill J (2014) Antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. The review on antimicrobial resistance

- 8.Murray C, Ikuta K, Sharara F, et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399:629–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pelfrene E, Botgros R, Cavaleri M. Antimicrobial multidrug resistance in the era of COVID-19: a forgotten plight? Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2021;10:1–21. doi: 10.1186/s13756-021-00893-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization (2017) Prioritization of pathogens to guide discovery, research and development of new antibiotics for drug-resistant bacterial infections, including tuberculosis. [Accessed 25 March 2019]

- 11.World Health Organization (2020) Antibacterial agents in clinical and preclinical development. 2021. [Accessed 11 Feburary 2022]

- 12.Matos De Opitz CL, Sass P (2020) Tackling antimicrobial resistance by exploring new mechanisms of antibiotic action. Future Microbiol 15:703–708. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Lemire J, Harrison J, Turner RJ. Antimicrobial activity of metals: mechanisms, molecular targets and applications. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:371–384. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frei A, Zuegg J, Elliott A, et al. Metal complexes as a promising source for new antibiotics. Chem Sci. 2020;11:2627–2639. doi: 10.1039/C9SC06460E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viganor L, Howe O, McCarron P, et al. The antibacterial activity of metal complexes containing 1,10-phenanthroline: potential as alternative therapeutics in the era of antibiotic resistance. Curr Top Med Chem. 2016;17:1280–1302. doi: 10.2174/1568026616666161003143333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans A, Kavanagh K. Evaluation of metal-based antimicrobial compounds for the treatment of bacterial pathogens. J Med Microbiol. 2021;70:1–18. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.001363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Claudel M, Schwarte J, Fromm K. New antimicrobial strategies based on metal complexes. Chemistry. 2020;2:849–899. doi: 10.3390/chemistry2040056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frei A. Metal complexes, an untapped source of antibiotic potential? Antibiotics. 2020;9:1–10. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9020090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boros E, Dyson PJ, Gasser G. Classification of metal-based drugs according to their mechanisms of action. Chem. 2020;6:41–60. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2019.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dwyer F, Reid I, Shulman A, et al. The biological actions of 1,10-phenanthroline and 2,2[prime]-bipyridine hydrochlorides, quartnery salts and metal chelates and related compounds. Aust J Exp Biol Med. 1969;47:203–218. doi: 10.1038/icb.1969.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmed M, Rooney D, McCann M, et al. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of a phenanthroline-isoniazid hybrid ligand and its Ag+ and Mn2+ complexes. Biometals. 2019;32:671–682. doi: 10.1007/s10534-019-00204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Shaughnessy M, McCarron P, Viganor L, et al. The antibacterial and anti-biofilm activity of metal complexes incorporating 3,6,9-trioxaundecanedioate and 1,10-phenanthroline ligands in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Irish cystic fibrosis patients. Antibiotics. 2020;9:1–22. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9100674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gandra R, McCarron P, Fernandes M, et al. Antifungal potential of copper(II), manganese(II) and silver(I) 1,10-phenanthroline chelates against multidrug-resistant fungal species forming the Candida haemulonii Complex: Impact on the planktonic and biofilm lifestyles. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Granato M, Gonçalves D, Seabra S, et al. 1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione-based compounds are effective in disturbing crucial physiological events of Phialophora verrucosa. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Granato M, Mello T, Nascimento R, et al. Silver(I) and copper(II) complexes of 1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione against Phialophora verrucosa: a focus on the interaction with human macrophages and Galleria mellonella larvae. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.641258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vargas Rigo G, Petro-Silveira B, Devereux M, et al. Anti-Trichomonas vaginalis activity of 1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione-based metallodrugs and synergistic effect with metronidazole. Parasitology. 2019;146:1179–1183. doi: 10.1017/S003118201800152X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lima A, Elias C, Oliveira S, et al. Anti-Leishmania braziliensis activity of 1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione and its Cu(II) and Ag(I) complexes. Parasitol Res. 2021;120:3273–3285. doi: 10.1007/s00436-021-07265-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papadia P, Margiotta N, Bergamo A, et al. Platinum(II) complexes with antitumoral/antiviral aromatic heterocycles: effect of glutathione upon in vitro cell growth inhibition. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3364–3371. doi: 10.1021/jm0500471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang E, Simmers C, Knight D. Cobalt complexes as antiviral and antibacterial agents. Pharmaceuticals. 2010;3:1711–1728. doi: 10.3390/ph3061711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viganor L, Galdino A, Nunes A, et al. Anti-Pseudomonas aeruginosa activity of 1,10-phenanthroline-based drugs against both planktonic- and biofilm-growing cells. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:128–134. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ventura R, Galdino A, Viganor L, et al. Antimicrobial action of 1,10-phenanthroline-based compounds on carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii clinical strains: efficacy against planktonic- and biofilm-growing cells. Braz J Microbiol. 2020;51:1703–1710. doi: 10.1007/s42770-020-00351-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vianez Peregrino I, Ferreira Ventura R, Borghi M, et al. Antibacterial activity and carbapenem re-sensitizing ability of 1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione and its metal complexes against KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical strains. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2021;73:139–148. doi: 10.1111/lam.13485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gandra R, McCarron P, Viganor L, et al. In vivo activity of copper(II), manganese(II), and silver(I) 1,10-phenanthroline chelates against Candida haemulonii using the Galleria mellonella model. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCann M, Santos A, Da Silva B, et al. In vitro and in vivo studies into the biological activities of 1,10-phenanthroline, 1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione and its copper(II) and silver(I) complexes. Toxicol Res. 2012;1:47–54. doi: 10.1039/c2tx00010e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galdino A, Viganor L, De Castro A, et al. Disarming Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence by the inhibitory action of 1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione-based compounds: Elastase B (lasB) as a chemotherapeutic target. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1–16. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galdino A, Viganor L, Pereira M, et al. Copper(II) and silver(I)-1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione complexes interact with double-stranded DNA: further evidence of their apparent multi-modal activity towards Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2022;27:201–213. doi: 10.1007/s00775-021-01922-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCann S, McCann M, Casey R, et al. Manganese(II) complexes of 3,6,9-trioxaundecanedioic acid (3,6,9-tddaH2): X-ray crystal structures of [Mn(3,6,9-tdda)(H2O)2]·2H2O and {[Mn(3,6,9-tdda)(phen)2·3H2O]·EtOH}n. Polyhedron. 1997;16:4247–4252. doi: 10.1016/S0277-5387(97)00233-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kellett A, Howe O, O’Connor M, et al. Radical-induced DNA damage by cytotoxic square-planar copper(II) complexes incorporating o-phthalate and 1,10-phenanthroline or 2,2′-dipyridyl. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:564–576. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCann M, Cronin J, Devereux M, et al. Copper(II) complexes of heptanedioic acid (hdaH2) and octanedioic acid (odaH2): X-ray crystal structures OF [Cu(η2-hda)(phen)2]·11H2O and [Cu(η2-oda)(phen)2]·12H2O (phen = 1,10-Phenanthroline) Polyhedron. 1995;14:2379–2387. doi: 10.1016/0277-5387(95)00075-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Devereux M, McCann M, Cronin J, et al. (1999) Binuclear and polymeric copper(II) dicarboxylate complexes: syntheses and crystal structures of [Cu2(pda)(phen)4](ClO4)2.5H2O.C2H5OH, [Cu2(oda)(phen)4](ClO4)2.2.67H2O.C2H5OH. Polyhedron 18:2141–2148

- 41.McCann M, Casey M, Devereux M, et al. Syntheses, X-ray crystal structures and catalytic activities of the manganese(II) butanedioic acid complexes. Polyhedron. 1997;16:2547–2552. doi: 10.1016/S0277-5387(97)00002-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geraghty M, McCann M, Casey M, et al. Synthesis and catalytic activity of manganese (II) complexes of pentanedioic acid; X-ray crystal structure of [Mn(phen)2(H20)2][Mn(O2C(CH 2)3CO2)(phen)2H2O](O2C(CH2)3CO2)·12H2O(phen=1,10-phenanthroline) Inorganica Chim Acta. 1998;277:257–262. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1693(97)06160-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCann M, Casey M, Devereux M, et al. (1997) Manganese(II) complexes of hexanedioic and heptanedioic acids: X-ray crystal structures of [Mn(O2C(CH2)4CO2(phen)2H2O]·7H2O and [Mn(phen)2(H2O)2][Mn(O2C(CH2)5CO2)[phen)2H2O](O2C(CH2)5CO2)·12.5H2O. Polyhedron 16:2741–2748

- 44.Thornton L, Dixit V, Assad L, et al. Water-soluble and photo-stable silver(I) dicarboxylate complexes containing 1,10-phenanthroline ligands: Antimicrobial and anticancer chemotherapeutic potential, DNA interactions and antioxidant activity. J Inorg Biochem. 2016;159:120–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2016.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing EUCAST disk diffusion method. 2017. [Accessed 17 September 2018] http://www.eucast.org.

- 46.Odds FC. Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52:1–2. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Terminology relating to methods for the determination of susceptibility of bacteria to antimicrobial agents. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2000;6:503–508. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2000.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gautam S, KC R, Leong K, et al. (2019) A step-by-step beginner’s protocol for whole genome sequencing of human bacterial pathogens. J Biol Methods 6:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. The european committee on antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 7.1, 2017. [Accessed 17 September 2018] http://www.eucast.org.

- 50.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Routine and extended internal quality control as recommended by EUCAST. Version 7.0, 2017. [Accessed 17 September 2018] http://www.eucast.org.

- 51.Magiorakos A, Srinivasan A, Carey R, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Devereux M, Mccann M, Leon V et al. (2000) Synthesis and biogical activity of manganese (II) complexes of phtalic and isophtalic acid: X-ray crystal structures of [Mn(ph)(phen)2(H2O)].4H2O, [Mn(phen)2(H2O)2]2(Isoph)2(phen).12H2O and [Mn(isoph)(bipy)]4.2.75bipy. Met Based Drugs 7:275–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.McCarron P, McCann M, Devereux M, et al. Unprecedented in vitro antitubercular activitiy of manganese(II) complexes containing 1,10-phenanthroline and dicarboxylate ligands: increased activity, superior selectivity, and lower toxicity in comparison to their copper(II) analogs. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levison M, Levison J. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antibacterial agents. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2009;23:791–815. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Impey R, Hawkins D, Sutton J, et al. Overcoming intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms associated with the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria. Antibiotics. 2020;9:1–19. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9090623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]