Abstract

We recently generated interleukin-4 (IL-4) receptor alpha-deficient (IL-4Rα−/−) BALB/c mice and showed evidence for a protective role of IL-13-mediated functions in leishmaniasis. In this study, we investigated the IL-4 expression and T helper 2 (Th2) development in Leishmania major-infected IL-4Rα−/− mice. Here we show that the early burst of IL-4 expression observed in L. major-infected BALB/c mice is independent of IL-4Rα-mediated functions. Subsequently, we confirmed an impaired Th2 development in vitro. Unexpectedly, during L. major infection, isolated CD4+ IL-4Rα−/− T cells expressed high IL-4- but low gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-specific mRNA, comparable to Th2-polarized BALB/c CD4+ cells and in contrast to Th1-polarized C57BL/6 CD4+ cells. Since antigen-specific restimulated popliteal lymph node cells (PLN) of IL-4Rα−/− mice also responded with high IL-4 but low IFN-γ production, comparable to Th2-polarized cells from wild-type BALB/c mice and in contrast to Th1-polarized C57BL/6 cells, these results suggested an unimpaired Th2 polarization during an established infection with L. major. To further define the observed IL-4 receptor-independent Th2 cell phenotype, we determined an independent Th2 marker, the IL-12 receptor beta-2 (IL-12Rβ2)-specific transcript levels of CD4+ T cells. Confirming Th2 polarization in L. major-infected IL-4Rα−/− mice, comparable IL-12Rβ2 message levels between CD4+ T cells from infected IL-4Rα−/− mice and Th2 cells from BALB/c mice were found, whereas Th1-polarized C57BL/6 cells showed strikingly increased IL-12Rβ2 expression levels. These results indicate that signals mediated by the IL-4Rα are not necessary to induce and sustain an efficient IL-4 expression and Th2 polarization in L. major-infected BALB/c mice and suggest that IL-4Rα-independent mechanisms underlie the default Th2 development in L. major-infected BALB/c mice.

Experimental murine leishmaniasis is a paradigm example for the relationship between the genetic factors that control T helper cell differentiation and the outcome of the disease. Healer strains like C57BL/6 develop dominant T helper 1 (Th1) responses with high gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production, low interleukin-4 (IL-4) production, and protective cellular immune responses, whereas nonhealer strains like BALB/c develop dominant Th2 responses with high IL-4 and low IFN-γ production, resulting in exacerbation of the disease (20, 39). This infectious disease model has been particularly versatile to study the mechanisms operating in vivo during the onset of T helper cell development from a common pool of naive CD4+ T-cell precursors.

In vitro, IL-12 and IL-4 were clearly shown to drive T helper development toward the Th1 and Th2 phenotypes (26, 36, 53, 55), respectively. In vivo, the role of IL-4 for Th2 development has been studied extensively in murine leishmaniasis. Neutralization of early Leishmania major-induced IL-4 production increases resistance in BALB/c mice by promoting a protective Th1 response and represses the development of a deleterious Th2 polarization (6, 50). It has been shown that a LACK antigen-specific Vβ4+Vα8+ CD4+ T-cell population is responsible for the early burst of IL-4 and that depletion of this subpopulation renders BALB/c mice resistant to the infection (33). The importance of IL-12 for Th1 development in vivo has also been demonstrated in this infection model. Mice on a genetically resistant background are rendered susceptible to infection with L. major by the disruption of IL-12 and mount a polarized Th2 cell response (40). Moreover, treatment with IL-12 during the onset of the infection increases resistance in BALB/c mice, skewing the T helper development toward Th1 (22, 56). Recent in vitro studies have demonstrated that Th2 commitment proceeds from a rapid loss of IL-12 responsiveness due to the down-regulation of the IL-12 receptor beta-2 chain (IL-12Rβ2) in BALB/c T cells (18, 57). Moreover, L. major infection rapidly induces IL-12 unresponsiveness in BALB/c mice (23, 35). Despite these accumulating data, the role of IL-4 in driving BALB/c mice toward a dominant Th2 development in L. major infection is not completely understood. It remains elusive whether the enhanced IL-4 production or the rapidly induced IL-12 unresponsiveness drive Th2 polarization in L. major-infected BALB/c mice.

We have recently generated an IL-4Rα-deficient mouse strain on a genetically pure BALB/c background and demonstrated that both IL-4- and IL-13-mediated functions were abrogated in the absence of IL-4Rα. IL-4Rα−/− mice showed an increased resistance to infection with L. major, also observed in IL-4-deficient BALB/c mice. In contrast to the latter, IL-4Rα−/− mice eventually developed progressive disease, which indicates a protective role for IL-13 in chronic leishmaniasis (45). The experiments presented here were designed to follow IL-4 expression and T helper cell development in vivo in the absence of IL-4Rα-mediated functions. IL-4Rα−/− mice are an ideal animal model to address this question, since T helper development can be assessed on the basis of expression of IL-4, the key effector cytokine of Th2 cells. Whereas in vitro Th2 development was strikingly impaired, in vivo we found an unimpaired Th2 polarization in L. major-infected IL-4Rα-deficient mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

IL-4Rα−/− mice were generated on a pure BALB/c genetic background as recently described (45). Mice were bred in specific-pathogen-free facilities and during infection experiments were kept in filter top cages and maintained in barrier facilities at the Max Planck Institute for Immunobiology (Freiburg, Germany) or at the University of Cape Town (Cape Town, South Africa).

Infection with L. major.

L. major LV 39 (MRHO/Sv/59/P strain) (40) was maintained by continuous passage in mice. Parasites were isolated from skin lesions of infected animals and grown in complete Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM; Gibco, Paisley, Scotland) on rabbit blood agar as described elsewhere (45). Anesthetized mice were infected subcutaneously into one hind footpad with 2 × 106 to 20 × 106 stationary-phase metacyclic L. major promastigotes (9) in a final volume of 50 μl of Hanks' balanced salt solution. For intravenous infections, 2 × 107 promastigotes were used.

Stationary-phase cultures were also used to prepare freeze-thawed (F/T) antigen of L. major promastigotes (59). Briefly, the cultures were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and diluted in PBS to a final concentration of 107 parasites/ml. Parasites were rapidly frozen to −80°C and thawed at 37°C four times. F/T preparations were stored at −80°C until use.

Cell separation. (i) Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

Cells (1 × 107 to 5 × 107) were labeled and washed in PBS–3% fetal calf serum (FCS) at 4°C. Between each step of staining, cells were washed twice extensively. Labeling was performed with phycoerythrin-coupled anti-CD4 (RM4-5; PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.). To avoid nonspecific binding, cells were preincubated for 20 min with a cocktail of mouse and rat sera diluted 1/40 and unlabeled anti-CD32 (2.4G2) antibody. Cell sorting was performed on a FACStar (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) in buffer without NaN3 as recently described (8). Sorted cells were collected in complete IMDM with 20% FCS. The resulting CD4+ cell population were of >99% purity (data not shown).

(ii) Magnetic beads.

Peripheral draining lymph nodes were purified for CD4+ cells by incubation with magnetic beads coated with anti-CD4 antibody RM4-5 (PharMingen), using the Dynabeads system as instructed by the manufacturer (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) as recently described (24). Subsequently, positively selected cells were detached from the beads. FACScan analysis of the resulting CD4+ cell population revealed >85% purity (data not shown).

In vitro CD4+ cell differentiation. (i) In vitro Th2 cell differentiation.

CD4+ T cells purified from lymph nodes were cultured at 106/ml in flat-bottom microwells (2 × 105/well) precoated with anti-CD3 (145-2C11; 10 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 (37/51; 10 μg/ml) and cultured in complete IMDM supplemented with IL-2 (50 U/ml; PharMingen). T helper development was driven by IL-12 (1 ng/ml; PharMingen), IL-4 (500 U/ml; PharMingen), or IL-13 (25 pg/ml; R&D Systems) and neutralizing antibody for IL-4 (11B11; 10 μg/ml) or IFN-γ (R4-6A2; 10 μg/ml) as indicated. After 72 h, cells were washed extensively, transferred to fresh microwells, and cultured in the presence of IL-2 (50 U/ml) for 24 h. Finally, cells were transferred to microwells precoated with anti-CD3. Cell-free supernatants were collected after 48 h of culture without any additional reagents. Values represent means and standard deviations of triplicate cultures.

(ii) L. major-specific restimulation.

Restimulation of cells from draining lymph nodes of L. major-infected mice was performed as described previously (38). Briefly, cells (2 × 106 per well in 1 ml of complete IMDM) were stimulated in the presence of recombinant IL-2 (250 U/ml; PharMingen) with plate-bound anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (145-2C11; 20 μg/ml) or 106 of F/T L. major antigen per ml in 48-well flat-bottom tissue culture plates. Supernatants were taken after 48 and 72 h of culture with anti-CD3 or L. major antigen, respectively. Cytokine levels in the supernatants were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Values represent means and standard deviations of triplicate cultures.

RT-mediated PCR (RT-PCR).

RNA preparation, reverse transcription, and PCR were performed as previously described (8, 29, 52). Briefly, total cellular RNA was prepared from spleen cells or CD4+ popliteal lymph nodes (PLN), using RNA-Clean (AGS, Heidelberg, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA (3 μg) in a 30-μl reaction volume containing random hexamer primers (50 pg/ml; Pharmacia, LKB, Freiburg, Germany), 0.4 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Promega, Heidelberg, Germany), 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 75 mM KCl, and 3 mM MgCl2 in the presence of 0.5 U of RNase inhibitor (Promega) was reverse transcribed with murine Moloney leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (RT; 16 U/ml; Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 90 min, terminated by heating to 94°C for 3 min, and immediately chilled on ice. Samples were diluted 1:10 with H2O to a concentration of 10 ng of cDNA equivalents per ml, assuming a 1:1 ratio of reverse transcription. Cycling conditions were 94°C for 2 min before 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 56 to 62°C (depending on the primer pairs used) for 30 s, and 30 s at 72°C, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 3 min. Cycling conditions for the amplification of β2-microglobulin consisted of 32 cycles. PCR was performed using 0.2 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Stehelin AG, Basel, Switzerland) in a total volume of 50 μl. Half of the PCR mixture was separated on a 1.6% agarose gel containing 0.2 μg of ethidium bromide per ml.

Quantification of cytokine transcripts.

The level of individual transcripts was determined by competitive RT-PCR as originally described (4), using the multispecific competitor plasmids pMUS (54) for β2-microglobulin, IL-4, and IFN-γ and pSPCR1 (27) for IL-4Rα. Before quantification of individual transcripts, cDNAs were adjusted to equal concentrations of the housekeeping β2-microglobulin gene. PCR mixtures with equal aliquots (usually 4 ml) of the diluted RT reaction containing approximately 40 ng of cDNA equivalents and oligonucleotide-specific primers were added to serial fourfold dilutions ranging from 5 × 106 to 75 molecules of the appropriate competitor plasmid as previously described (8, 29, 52) and indicated in Fig. 3. PCR coamplification was performed during the logarithmic phase, using the cycling conditions described above. Specific primers compete for binding on and amplification of the competitor control fragment and cellular cDNA, resulting in fragments differing 50 to 100 bp in size. The PCR products derived from the competitor template and the cDNA were resolved on an agarose gel, and the relative ethidium bromide staining intensities of the target and the competitor DNAs were compared. Equal staining intensities in the competitive reaction indicates equal concentrations, allowing quantification of the input cDNA. In all experiments, control PCR with competitor only or without DNA was performed to exclude false positives.

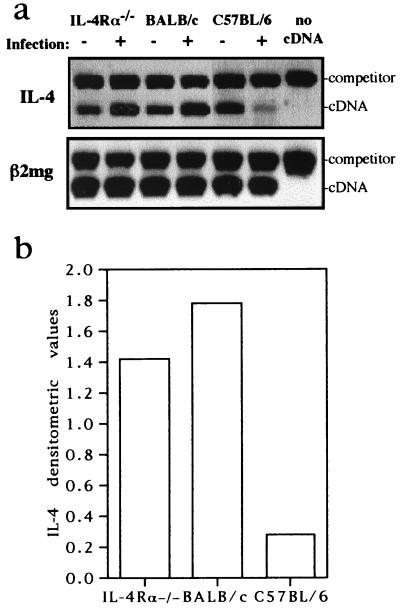

FIG. 3.

Competitive RT-PCR from CD4+ cells at day 49 after infection with L. major. IL-4Rα−/− BALB/c, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 (four per group) were injected with 2 × 106 L. major promastigotes into one hind footpad. At day 49 after infection, draining lymph nodes from groups were pooled, CD4+ T lymphocytes were purified by magnetic beads, and the isolated RNA was reverse transcribed. Levels of specific mRNAs were determined by competitive RT-PCR after standardization of cDNAs for the constitutive housekeeping β2-microglobulin gene (β2mg) at 3 × 105 molecules. Arrows indicate equimolar amount of cDNA and competitor (comp.) PCR product, the latter used in fourfold dilutions with absolute numbers indicated. IL-12Rβ2-specific transcripts were measured semiquantitatively. (b) Transcript numbers of IFN-γ and IL-4 per 3 × 105 molecules of β2-microglobulin of CD4+ T cells from indicated mouse strains. IL-4Rα and BALB/c CD4+ T cells had equal transcript numbers of IFN-γ (1.2 × 103) and IL-4 (6.1 × 102) but eightfold-reduced IFN-γ and at least eightfold-increased IL-4 transcripts in comparison to C57BL/6 cells (IFN-γ, 9.8 × 104; IL-4, <75 molecules). (c) Densitometric analysis of IL-4Rα and IL-12Rβ2 PCR after normalization with corresponding β2-microglobulin cDNA PCR signal strength (pixels per square millimeter). The densitometric values refer to PCR signal strength differences (BALB/c values arbitrary set as 1) between indicated mouse strains. IL-4Rα expression levels between BALB/c and C57BL/6 were comparable. No significant difference was observed for IL-12Rβ2 expression levels between IL-4Rα−/− and BALB/c mice, whereas C57BL/6 PLN showed a threefold increase after infection.

IL-12Rβ2-specific cDNA was amplified for 30 cycles with the primers IL-12Rβ2-s (5′-CTGCACCCACTCACATTAAC-3′) and IL-12Rβ2-as (5′-CAGTTGGCTTTGCCCTGTGG-3′), amplifying a 670-bp product. No specific products were obtained when reverse transcription was omitted or genomic DNA was used as the template.

Densitometric analysis was performed using the computer-based image software NIH Image 1.52 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.) and measured as pixels per square millimeter.

ELISA.

Cytokine levels in culture supernatants were detected by sandwich ELISA as described before (7). Supernatants and appropriate cytokine standards (PharMingen) were used in threefold serial dilutions. The coating and biotinylated detection antibodies for IFN-γ and IL-4 were purchased from PharMingen. Detection was performed with alkaline phosphatase-coupled streptavidin (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, Ala.). The detection limits for IFN-γ and IL-4 were 0.2 and 0.01 ng/ml, respectively.

RESULTS

IL-4Rα-independent IL-4 expression during early L. major infection.

L. major induces a burst of IL-4 mRNA expression in the spleen cells of BALB/c mice 90 min after intravenous infection. The source are CD4+ T cells that express a canonical Vβ4+Vα8+ T-cell receptor repertoire (33). Using IL-4Rα−/− mice, we intended to determine if this early burst of IL-4 expression is independent on a IL-4Rα-mediated stimulation by IL-4 and repeated the original experiments, including IL-4Rα-deficient mice. IL-4Rα−/−, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 mice were infected intravenously with 107 L. major LV 39 (MRHO/Sv/59/P strain) metacyclic promastigotes. Ninety minutes later, mice were sacrificed, total RNA was extracted, and an aliquot was reverse transcribed from individual spleens as described in Materials and Methods. After adjusting the individual cDNA samples to equal concentrations for the housekeeping β2-microglobulin gene, the level of IL-4-specific mRNA expression was quantified by competitive RT-PCR and compared with mRNA levels from uninfected mice (Fig. 1). Spleen cells from infected BALB/c mice showed an increase of IL-4 message in comparison to uninfected BALB/c mice. In contrast, infected C57BL/6 cells showed reduced IL-4 mRNA levels compared to uninfected controls, confirming previous results (33). Spleen cells from infected IL-4Rα−/− BALB/c mice showed also a similar increase of IL-4 message in comparison to uninfected BALB/c mice, therefore reflecting the phenotype of BALB/c mice but not C57BL/6 mice. As suggested from published BALB/c studies (35), our results demonstrate that the early IL-4 expression induced by L. major infection in BALB/c mice can be independent of signals mediated by IL-4Rα.

FIG. 1.

L. major-induced early IL-4 expression. BALB/c IL-4Rα−/−, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 mice (two per group) were intravenously injected with 200 μl of Hanks' balanced salt solution in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 2 × 107 L. major promastigotes. Mice were sacrificed after 90 min, and total RNA was isolated from spleens. (a) Levels of IL-4-specific mRNAs were determined by RT-PCR after standardization of cDNAs for the constitutive housekeeping β2-microglobulin gene (β2mg) in a competitive RT-PCR. (b) Densitometric analysis of IL-4 PCR after normalization with corresponding β2-microglobulin cDNA PCR signal strength (pixels per square millimeter). The IL-4 densitometric values refer to PCR signal strength differences between uninfected (arbitrarily set as 1) and infected spleen cells of indicated mouse strains. Increased IL-4 expression levels (densitometric values, 1.4 and 1.8) were found in IL-4Rα−/− and BALB/c mice, whereas a striking reduction (0.2) was found in spleen cells of infected C57BL/6 mice.

IL-4Rα-independent IL-4 production during an established L. major infection.

To investigate the in vivo T helper development in the absence of a functional IL-4 receptor, we performed acute L. major infection studies and determined the differentiation of Th1 versus Th2 cells were. IL-4Rα−/−, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 mice were infected with 2 × 107 L. major LV 39 (MRHO/Sv/59/P strain) metacyclic promastigotes into one hind footpad. The course of infection was monitored by measuring the swelling of the infected footpad weekly (data not shown). At day 56 postinfection, at a time point where T helper cell polarization is known to be established, animals were sacrificed and the draining PLN were isolated. To reveal the cytokine expression profile, cells were restimulated by the addition of either anti-CD3 or Leishmania antigen for 48 or 72 h, and cytokine concentration in supernatants were measured by ELISA (Fig. 2). After polyclonal T-cell restimulation with anti-CD3, IFN-γ concentrations were low in supernatants from BALB/c and IL-4Rα−/− cultures but high in cultures of PLN from infected C57BL/6 mice. IL-4 concentrations were relatively high in supernatants from cultures of all three strains.

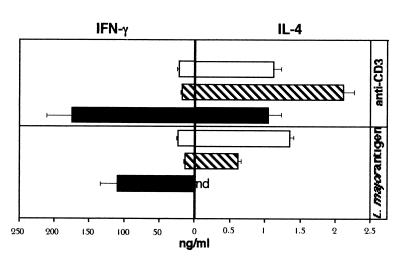

FIG. 2.

Restimulation of PLN with anti-CD3 or L. major antigen. IL-4Rα−/− (open bars), BALB/c (hatched bars), and C57BL/6 (filled bars) mice (four per group) were injected with 2 × 107 L. major promastigotes into one hind footpad. At day 56 after infection, cells from the draining lymph nodes from each group were pooled and restimulated in 48-well plates with IL-2 (250 U/ml) in the presence of anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) or L. major antigen (106/ml) for 48 or 72 h, respectively. IFN-γ and IL-4 concentrations in the supernatants were determined by ELISA. Values are means and positive standard deviations from triplicate cultures. nd, not detected. Representative results from two independent experiments are shown.

Leishmania antigen-specific restimulation of PLN revealed a pronounced type 1 polarization of C57BL/6 cells with high IFN-γ levels and undetectable IL-4, whereas BALB/c cultures had at least 50-fold-higher IL-4 and 5-fold-lower IFN-γ concentrations, demonstrating a type 2 polarization. Interestingly, IL-4Rα−/− mice showed a type 2 cytokine profile comparable to that of BALB/c mice after antigen-specific restimulation of PLN. Similar results were found at 10 and 18 weeks after infection with 2 × 106 promastigotes into one hind footpad (Table 1). At the latter time point, antigen-specific IL-4 production was undetectable, with high IFN-γ concentrations in BALB/c or IL-4Rα−/− mice. A similar Th1 response in late infection of BALB/c mice was recently observed by others (5). Taken together, these experiments demonstrate that a sustained IL-4 production can be independent of IL-4Rα-mediated function in L. major-primed BALB/c lymphocytes. Moreover, the lack of a functional IL-4 receptor results in no increased production of IFN-γ and therefore no skewed Th1 response. Conclusively, our observations suggest an IL-4Rα-independent, highly efficient mechanism for type 2 differentiation in L. major-infected BALB/c mice.

TABLE 1.

Restimulation of draining PLN with L. major antigen

| Strainb | Mean Concn (ng/ml) ± SD

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 wk post infectiona

|

18 wk postinfection

|

|||||||

| Medium

|

L. major antigen

|

Medium

|

L. major antigen

|

|||||

| IL-4 | IFN-γ | IL-4 | IFN-γ | IL-4 | IFN-γ | IL-4 | IFN-γ | |

| IL-4Rα−/− | ≤0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.12 | 0.7 ± 0.03 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | ≤0.01 | 0.50 ± 0.09 | ≤0.01 | 38.3 ± 4.4 |

| BALB/c | ≤0.01 | 0.24 ± 0.21 | 0.6 ± 0.09 | 2.7 ± 1.2 | ≤0.01 | 6.21 ± 0.21 | ≤0.01 | 30.0 ± 0.9 |

| C57BL/6 | ≤0.01 | 5.50 ± 2.78 | ≤0.01 | 22.2 ± 1.6 | NDc | ND | ND | ND |

2 × 106 promastigotes/mouse injected into one hind footpad.

Four mice per group.

ND, not determined.

An unimpaired Th2 polarization in L. major-infected IL-4Rα−/− BALB/c mice.

To determine in vivo T helper polarization of CD4+ cells, omitting in vitro restimulation, we assessed gene transcription by RT-PCR. We infected IL-4Rα−/−, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 mice with 2 × 106 L. major promastigotes (45) and isolated CD4+ T cells from PLN 49 days after infection by anti-CD4-coupled magnetic beads. RNA was extracted, and IL-4- and IFN-γ-specific message was quantified by competitive RT-PCR after adjusting the cDNAs, using the constitutive housekeeping β2-microglobulin gene as a standard (Fig. 3). Quantitative analysis showed that CD4+ T cells from infected C57BL/6 mice expressed eightfold-higher IFN-γ-specific transcript levels and at least eightfold-lower IL-4-specific transcript levels compared with BALB/c mice (Fig. 3a and b). These results were consistent with our antigen-specific restimulation experiments and confirm earlier studies (3, 20, 39), demonstrating a dominant Th1 phenotype in resistant C57BL/6 mice but a dominant Th2 phenotype in susceptible BALB/c mice. IL-4Rα−/− CD4+ cells showed IFN-γ- and IL-4-specific transcript levels comparable to those of Th2-differentiated BALB/c CD4+ cells (Fig. 3a and b). The unimpaired Th2 phenotype of IL-4Rα−/− CD4+ T cells in comparison to BALB/c controls was unexpected, as it is believed that IL-4 is the factor responsible for Th2 differentiation in leishmaniasis. Hence, we determined CD4+ T cells for an independent marker that is regulated in a T helper-specific manner. IL-12Rβ2 is expressed very early during T-cell activation. It is subsequently down-regulated on developing Th2 cells, rendering them unresponsive to IL-12, whereas it remains expressed on Th1 cells in vitro (57). This down-regulation has also been observed in vivo after infection of BALB/c mice with L. major (23, 35). Indeed, as shown in Fig. 3c, the levels of IL-12Rβ2-specific mRNA of Th2-differentiated BALB/c CD4+ cells were strikingly (threefold) lower than those of Th1-differentiated C57BL/6 cells. Comparable low levels of IL-12Rβ2 transcription levels were found in CD4+ cells from IL-4Rα−/− and BALB/c mice, confirming the presence of Th2-polarized cells in infected IL-4Rα−/− mice. The expression levels of IL-4Rα were similar in Th1-polarized cells of C57BL/6 mice and Th2 cells of BALB/c mice (Fig. 3c), indicating that the loss of IL-4 responsiveness does not underlie differential IL-4 receptor expression in BALB/c mice.

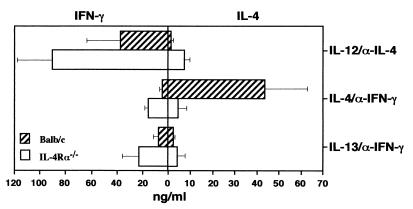

Impaired in vitro Th2 differentiation in the absence of IL-4Rα.

IL-4 induces the differentiation of naive Th cells into Th2 cells in vitro (36, 55), whereas Th1 development is driven by IL-12 (53). Since the in vivo L. major studies showed an unimpaired Th2 cell phenotype in IL-4Rα−/− mice, the in vitro potential of naive IL-4Rα−/− T cells to differentiate into Th1/Th2 cells was investigated. Unprimed CD4+ lymph node cells from IL-4Rα−/− mice and wild-type controls were isolated by FACS, subsequently cultured with anti-CD3/CD28 in the presence of IL-2, and stimulated with a combination of either IL-12 and anti-IL-4 to induce Th1 development or IL-4 and anti-IFN-γ to induce Th2 development. IL-4Rα−/− CD4+ T cells showed normal Th1 differentiation, as indicated by their ability to produce high amounts of IFN-γ but low levels of IL-4, similarly to wild-type cells, following IL-12–anti-IL-4 stimulation (Fig. 4). In contrast, IL-4Rα−/− CD4+ T cells showed impaired in vitro Th2 differentiation, determined by >2-fold-higher IFN-γ but >10-fold-lower IL-4 production compared to IL-4-stimulated wild-type cells (Fig. 4). IL-13 in combination with anti-IFN-γ had no major effect on T helper differentiation since both IFN-γ and IL-4 levels remained low in wild-type cells.

FIG. 4.

Impaired in vitro Th2 differentiation. FACS-isolated CD4+ cells (>99% purity) of IL-4Rα−/− (white bars) or wild-type (hatched bars) PLN (106 cells/ml) were cultured with anti-CD3/CD28 in the presence of IL-2 (50 U/ml). T helper development was promoted by a combination of IL-12 (1 ng/ml) and anti-IL-4 (11B11; 10 mg/ml), to generate Th1 cells, or IL-4 (500 U/ml) or IL-13 (25 pg/ml) in the presence of anti-IFN-γ (R4-6A2; 10 mg/ml), to generate Th2 cells. Three days later, cells were washed and further incubated with IL-2 for 24 h. Finally, cells were transferred onto anti-CD3-coated plates without additional stimuli, and IFN-γ and IL-4 levels in the supernatants were determined 2 days later by ELISA. Values are means and standard deviations from triplicate cultures. PLN from IL-4Rα-derived cells showed no significant differences in the production of IFN-γ and IL-4 compared to corresponding BALB/c cells (P > 0.12 by Student's t test). The data are representative of two experiments.

DISCUSSION

L. major infection studies in IL-4Rα−/− BALB/c mice demonstrated that the early burst of endogenous IL-4 expression in BALB/c mice is independent of stimulation by its own receptor but directly induced by Leishmania, confirming previous infection studies in BALB/c mice (34). Depletion studies have shown that the source of early IL-4 production is a T-cell receptor-restricted LACK antigen-specific Vβ4+Vα8+ CD4+ T-cell population. Its depletion also abrogates Th2 development (33).

The main finding in this study was an unimpaired Th2 polarization in L. major-infected IL-4Rα−/− mice during an established infection. We demonstrated the presence of a Th2 cell phenotype by all analyzed criteria of CD4+ T cells: high IL-4 but low IFN-γ and IL-12Rβ2 transcript and/or protein expression levels comparable to Th cells of infected BALB/c controls at 6 and 8 weeks in infected IL-4Rα−/− BALB/c mice. These results clearly demonstrate that L. major-specific Th2 cells are able to develop efficiently in the absence of IL-4 (or IL-13)-mediated functions. This was unexpected, as it is believed that the Th2-promoting influence of IL-4 is responsible for driving Th2 development in L. major-infected BALB/c mice, a conclusion based mainly on IL-4 neutralization studies. Despite our finding of an unimpaired Th2 polarization in an established infection, an influence of endogenous IL-4 on Th2 cell differentiation in L. major-infected mice, which may be more evident in earlier time points during the course of infection, cannot be excluded. Indeed, in a recent study, L. major-infected IL-4Rα−/− BALB/c mice showed a reduction of IL-4-specific message in draining lymph nodes compared to BALB/c controls at 56 days postinfection (46). However, since data were obtained from unseparated PLN, the observed twofold reduction could be also due to a lack of IL-4-mediated downstream effector functions on CD4-negative cells rather than reduced IL-4 expression in T helper cells. Irrespective of the influence of endogenous IL-4 on L. major-induced Th2 differentiation, the question arises as to the mechanism(s) responsible for the observed efficient IL-4 (or IL-13)-independent L. major-specific Th2 cell differentiation. Possible answers may inferred from recent studies which showed a cell-intrinsic bias toward IL-4 expression of activated CD4+ BALB/c T cells (17, 25). This genetically linked commitment has been demonstrated to be independent of signals mediated by the IL-4 receptor (2); therefore, it is possible that the high parasite burden in the draining lymph nodes of L. major-infected in BALB/c mice (45) itself is the driving force of the sustained activation of CD4+ Th2 cells, with subsequent transcription of IL-4 in chronically infected IL-4Rα−/− BALB/c mice. In addition, the dominant IL-4 phenotype could be exacerbated by conversion of L. major-specific Th1 cells (43) by L. major-infected and/or antigen-presenting cells (44) in the absence of IL-4-mediated functions or due to a lack of signals inducing a Th1 development. Indeed, we did not observe an increased Th1 response, and CD4+ T cells from wild-type and IL-4Rα−/− BALB/c mice showed strikingly reduced levels of 12Rβ2-specific message in comparison to C57BL/6 cells. IL-12 is the key promoting cytokine for Th1 development and antagonizes Th2-promoting cells. Therefore, the observed impaired IL-12 responsiveness by down-regulation of the IL-12 receptor may have favored Th2 differentiation of activated T cells in the mutant mice. This possible explanation is in agreement with the recent identification of a locus on chromosome 11 which seems to be involved in premature loss of functional IL-12 receptor expression, as one mechanism underlying the BALB/c bias (16, 19). Down-regulation of IL-12Rβ2 expression is also believed to depend on IL-4, since it can be prevented by the administration of IL-4 neutralizing antibodies (23, 35). The reduced IL-12Rβ2 expression levels of IL-4Rα−/− BALB/c CD4+ cells (in comparison to corresponding cells from C57BL/6 CD4+) clearly suggest that other (IL-4-independent) mechanisms must exist in addition.

The presence of an effective IL-4 receptor-independent Th2 differentiation pathway seems to be specific for L. major infection, as impaired Th2 differentiation was observed in IL-4Rα−/− mice infected with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis (1, 46). IL-4Rα−/− mice showed an even more severe impairment of the Th2 differentiation compared to infected IL-4-deficient mice, suggesting a regulatory role for the IL-13 on Th2 cell development (1). Similar observations were also made in IL-13- or IL-4/IL-13-deficient mice (41, 42). The molecular mechanisms for these IL-13-mediated functions are elusive, and direct IL-13 effects on T cells cannot be completely ruled out. Indirect regulatory effects are possible since IL-13, like IL-4, has potent modulating effects on macrophages, such as the secretion of NO, which is known to be protective against L. major, or IL-12 and IL-18 production. Both cytokines influence Th1 differentiation (48, 58), and their potential deregulation due to the absence of IL-13-mediated functions may alter T helper development in vivo. It should be noted that these IL-13 functions could potentially still be mediated in IL-4Rα−/− mice by the recently cloned IL-13Rα2 (10). Since neither exogenous IL-13 nor IL-4 can restore wild-type responses in T cells derived from IL-13−/− mice (41), IL-13 seems to act upstream of IL-4 on T cells. Mechanistically, IL-13 could modulate the common signal transduction pathways of IL-4 and IL-13, including the IL-4 receptor itself.

The observation of an impairment of in vitro Th2 differentiation is consistent with earlier studies (36, 53), and analysis in mice deficient in IL-4 (30, 32) or IL-4Rα (46) demonstrate that IL-4 is the promoting factor for Th2 differentiation in vitro. The absence of IL-13-driven Th2 differentiation (Fig. 4) is also consistent with studies showing that in contrast to human T cells, murine T cells are not responsive to IL-13 stimulation (60). It is worth noting that despite the absence of the IL-4 receptor, diminished but still measurable production of IL-4 was detected in the supernatants of stimulated IL-4Rα−/− lymph node cells irrespective of the stimuli used (Fig. 4). These results show that also in vitro IL-4 production can continue independently of IL-4Rα signaling as previously suggested (46), and IL-4-independent Th2 differentiation can be a major pathway as demonstrated in the study presented here.

The different outcome between L. major-infected IL-4Rα−/− mice and anti-IL-4 neutralization studies prompted us to reexamine common literature data. Interestingly, most of the original neutralization studies determined type 2 responses rather than Th2 differentiation, showing reduced immunoglobulin E production (31) and/or reduced IL-4 production in lymph node cells (5, 6), and an effect of anti-IL-4 treatment on PLN IL-4 expression was not always found (37). More important, in those rare anti-IL-4 experiments where Th2 differentiation was directly investigated using isolated CD4+ T cells, a reduction of IL-4 mRNA expression levels was originally found in Northern analysis (21, 50). However, a recent study using a more sensitive semiquantitative RT-PCR study could not confirm these previous findings with similar expression levels in anti-IL-4-treated and untreated BALB/c CD4+ T cells (47). In addition to the varying neutralization data, we should be aware that both approaches have their limits and may induce unknown alternative pathways. In the gene-deficient mouse model, mice develop in the absence of IL-4 (and IL-13)-mediated functions; hence alternative pathways, inactive in IL-4-producing wild-type mice, cannot be excluded. Moreover, soluble IL-4Rα is also absent in IL-4Rα−/− mice (45) but abundantly present in BALB/c mice (51), with increased expression levels in L. major-infected mice (12). Since both antagonistic and agonistic functions, which seem to depend on the relative concentration on IL-4 and soluble IL-4Rα, have been demonstrated (14, 15, 28), some unknown effects of soluble IL-4Rα on T helper differentiation in BALB/c mice cannot be ruled out. Anti-IL-4 neutralization, on the other hand, is effective only during the first 2 days after infection (35). Moreover, as discussed above, Th2 responses vary and other effects from the antibody treatment cannot be ruled out. For example, incomplete neutralization is probably unavoidable in autocrine stimulation pathways due to the close proximity of the ligand to the receptor, as is the case for IL-4-producing Th2 cells, and resulting partial signaling may alter T helper cell responses in vivo. Second, the anti-IL-4 antibody (11B11) used for neutralization studies has also stabilization properties on IL-4 in vivo, with altering effects on the kinetics of biodistribution of endogenous IL-4 (51). This may have consequences on in vivo T helper differentiation. Also, the demonstrated interrelationship between anti-IL-4 treatment and soluble IL-4Rα (11, 13, 49) may influence T helper differentiation. Therefore, some other (unknown) mechanisms due to these cytokine-binding proteins could be responsible for the observed Th2 polarization in IL-4-neutralized BALB/c mice. To investigate the possible effects of soluble IL-4Rα in L. major and Th2 differentiation, we are in the process of generating a mouse strain deficient for soluble IL-4Rα induced by alternative transcription.

In summary, our results show that signals mediated by the IL-4Rα are not necessary to induce and sustain IL-4 expression whereas IFN-γ production remains low in CD4+ cells. Hence, an efficient IL-4Rα-independent Th2-polarizing mechanism must exist that underlies the default Th2 development in L. major-infected BALB/c mice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank B. Arendse, M. Held, M. Simpson, and K.-H. Widmann for excellent technical assistance, H. Mossmann and H. Arendse for organization of the animal facility, J. C. Gutierrez-Ramos for obtaining the competitor plasmid pSPCR1, and G. Alber, M. Kopf, and A. Gessner for stimulating discussions and critical reviews of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the German-Israeli Foundation (grant I-260-162.02/92) and by the Medical Research Centre, South Africa (grant 415509). F.B. is holder of a Wellcome Senior Research Fellowship in Medical Science in South Africa.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

Since acceptance of the manuscript, we have shown that the adjuvant alum can drive a Th2 response independently of signaling through the interleukin-4 receptor alpha (J. M. Brewer, M. Conacher, C. A. Hunter, M. Mohrs, F. Brombacher, and J. Alexander, J. Immunol. 163:6448–6454, 1999).

REFERENCES

- 1.Barner M, Mohrs M, Brombacher F, Kopf M. Differences between IL-4Rα and IL-4 deficient mice reveal a novel role of IL-13 in the regulation of T helper 2 cells and protection to nematode infection. Curr Biol. 1998;8:669–672. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70256-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bix M, Wang Z E, Thiel B, Schork N J, Locksley R M. Genetic regulation of commitment to interleukin 4 production by a CD4(+) T cell-intrinsic mechanism. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2289–2299. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogdan C, Gessner A, Rollinghoff M. Cytokines in leishmaniasis: a complex network of stimulatory and inhibitory interactions. Immunobiology. 1993;189:356–396. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80366-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouaboula M, Legoux P, Pessegue B, Delpech B, Dumont X, Piechaczyk M, Casellas P, Shire D. Standardization of mRNA titration using a polymerase chain reaction method involving co-amplification with a multispecific internal control. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21830–21838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatelain R, Mauze S, Varkila K, Coffman R L. Leishmania major infection in interleukin-4 and interferon-gamma depleted mice. Parasite Immunol. 1999;21:423–431. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1999.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatelain R, Varkila K, Coffman R L. IL-4 induces a Th2 response in Leishmania major-infected mice. J Immunol. 1992;148:1182–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dai W D, Köhler G, Brombacher F. Both innate and acquired immunity to Listeria monocytogenes infection are increased in IL-10 deficient mice. J Immunol. 1997;158:2259–2267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dai W J, Bartens W, Köhler G, Hufnagel M, Kopf M, Brombacher F. Impaired macrophage listericidal and cytokine activities are responsible for the rapid death of Listeria monocytogenes-infected IFN-γ receptor-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1997;158:5297–5304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Da Silva R, Sacks D L. Metacyclogenesis is a major determinant of Leishmania promastigote virulence and attenuation. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2802–2806. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.11.2802-2806.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donaldson D D, Whitters M J, Fitz L J, Neben T Y, Finnerty H, Henderson S L, O'Hara R J, Beier D R, Turner K J, Wood C R, Collins M. The murine IL-13 receptor alpha 2: molecular cloning, characterization, and comparison with murine IL-13 receptor alpha 1. J Immunol. 1998;161:2317–2324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fanslow W C, Clifford K N, Park L S, Rubin A S, Voice R F, Beckmann M P, Widmer M B. Regulation of alloreactivity in vivo by IL-4 and the soluble IL-4 receptor. J Immunol. 1991;147:535–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez B R, Chilton P M, Hondowicz B D, Vetvickova J, Yan J, Jones III W, Scott P. Regulation of the production of soluble IL-4 receptors in murine cutaneous leishmaniasis. The roles of IL-12 and IL-4. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:481–488. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.3.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez B R, Wynn T A, Hieny S, Caspar P, Chilton P M, Sher A. Linked in vivo expression of soluble interleukin-4 receptor and interleukin-4 in murine schistosomiasis. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:649–656. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez-Botran R, Chilton P M, Ma Y, Windsor J L, Street N E. Control of the production of soluble interleukin-4 receptors: implications in immunoregulation. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;59:499–504. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.4.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gessner A, Schroppel K, Will A, Enssle K H, Lauffer L, Rollinghoff M. Recombinant soluble interleukin-4 (IL-4) receptor acts as an antagonist of IL-4 in murine cutaneous leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4112–4117. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4112-4117.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorham J D, Guler M L, Steen R G, Mackey A J, Daly M J, Frederick K, Dietrich W F, Murphy K M. Genetic mapping of a murine locus controlling development of T helper 1/T helper 2 type responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12467–12472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guery J C, Galbiati F, Smiroldo S, Adorini L. Selective development of T helper (Th) 2 cells induced by continuous administration of low dose soluble proteins to normal and beta(2)-microglobulin-deficient BALB/c mice. J Exp Med. 1996;183:485–497. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.2.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guler M L, Gorham J D, Hsieh C S, Mackey A J, Steen R G, Dietrich W F, Murphy K M. Genetic susceptibility to Leishmania: IL-12 responsiveness in TH1 cell development. Science. 1996;271:984–987. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guler M L, Jackobson N G, Gubler U, Murphy K M. T cell genetic background determines maintenance of IL-12 signaling. Effects on Balb/c and B10.D2 T helper cell type 1 phenotype development. J Immunol. 1997;159:1767–1774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinzel F P, Sadick M D, Holaday B J, Coffman R L, Locksley R M. Reciprocal expression of interferon gamma or interleukin 4 during the resolution or progression of murine leishmaniasis. Evidence for expansion of distinct helper T cell subsets. J Exp Med. 1989;169:59–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinzel F P, Sadick M D, Mutha S S, Locksley R M. Production of interferon gamma, interleukin 2, interleukin 4, and interleukin 10 by CD4+ lymphocytes in vivo during healing and progressive murine leishmaniasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7011–7015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heinzel F P, Schoenhaut D S, Rerko R M, Rosser L E, Gately M K. Recombinant interleukin 12 cures mice infected with Leishmania major. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1505–1509. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Himmelrich H, Parra L C, Tacchini C F, Louis J A, Launois P. The IL-4 rapidly produced in BALB/c mice after infection with Leishmania major down-regulates IL-12 receptor beta 2-chain expression on CD4+ T cells resulting in a state of unresponsiveness to IL-12. J Immunol. 1998;161:6156–6163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hölscher C, Köhler G, Müller U, Mossmann H, Schaub G A, Brombacher F. Defective nitric oxide effector functions lead to extreme susceptibility of Trypanosoma cruzi-infected mice deficient in gamma interferon receptor or inducible nitric oxide synthase. Infect Immun. 1997;66:1208–1215. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1208-1215.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsieh C S, Macatonia S E, O'Garra A, Murphy K M. T cell genetic background determines default T helper phenotype development in vitro. J Exp Med. 1995;181:713–721. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsieh C S, Macatonia S E, Tripp C S, Wolf S F, O'Garra A, Murphy K M. Development of T(H)1 CD4(+) T cells through IL-12 produced by Listeria-induced macrophages. Science. 1993;260:547–549. doi: 10.1126/science.8097338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jia G Q, Gutierrez-Ramos J C. Quantitative measurement of mouse cytokine mRNA by polymerase chain reaction. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1995;6:253–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jung T, Wagner K, Neumann C, Heusser C H. Enhancement of human IL-4 activity by soluble IL-4 receptors in vitro. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:864–871. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199903)29:03<864::AID-IMMU864>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kopf M, Brombacher F, Köhler G, Kienzle G, Widmann K-H, Lefrang K, Humborg C, Ledermann B, Solbach W. IL-4-deficient Balb/c mice resist infection with Leishmania major. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1127–1136. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kopf M, Le G G, Bachmann M, Lamers M C, Bluethmann H, Koehler G. Disruption of the murine IL-4 gene blocks Th2 cytokine responses. Nature. 1993;362:245–248. doi: 10.1038/362245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kropf P, Etges R, Schopf L, Chung C, Sypek J, Muller I. Characterization of T cell-mediated responses in nonhealing and healing Leishmania major infections in the absence of endogenous IL-4. J Immunol. 1997;159:3434–3443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuhn R, Rajewsky K, Muller W. Generation and analysis of interleukin-4 deficient mice. Science. 1991;254:707–710. doi: 10.1126/science.1948049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Launois P, Maillard I, Pingel S, Swihart K G, Xenarios I, Acha O H, Diggelmann H, Locksley R M, MacDonald H R, Louis J A. IL-4 rapidly produced by V beta 4 V alpha 8 CD4+ T cells instructs Th2 development and susceptibility to Leishmania major in BALB/c mice. Immunity. 1997;6:541–549. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80342-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Launois P, Ohteki T, Swihart K, MacDonald H R, Louis J A. In susceptible mice, Leishmania major induce very rapid interleukin-4 production by CD4+ T cells which are NK1.1−. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:3298–3307. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Launois P, Swihart K G, Milon G, Louis J A. Early production of IL-4 in susceptible mice infected with Leishmania major rapidly induces IL-12 unresponsiveness. J Immunol. 1997;158:3317–3324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Le Gros G, Ben S S, Seder R, Finkelman F D, Paul W E. Generation of interleukin 4 (IL-4)-producing cells in vivo and in vitro: IL-2 and IL-4 are required for in vitro generation of IL-4-producing cells. J Exp Med. 1990;172:921–929. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.3.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li J, Scott P, Farrell J P. In vivo alterations in cytokine production following interleukin-12 (IL-12) and anti-IL-4 antibody treatment of CB6F1 mice with chronic cutaneous leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5248–5254. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5248-5254.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Locksley R, Reiner S L, Hatam F, Littman D R, Killeen N. Helper T cells without CD4: control of leishmaniasis in CD4-deficient mice. Science. 1993;261:1448–1451. doi: 10.1126/science.8367726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Locksley R M, Heinzel F P, Holaday B J, Mutha S S, Reiner S L, Sadick M D. Induction of Th1 and Th2 CD4+ subsets during murine Leishmania major infection. Res Immunol. 1991;142:28–32. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(91)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mattner F, Magram J, Ferrante J, Launois P, Di P K, Behin R, Gately M K, Louis J A, Alber G. Genetically resistant mice lacking interleukin-12 are susceptible to infection with Leishmania major and mount a polarized Th2 cell response. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1553–1559. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKenzie G J, Emson C L, Bell S E, Anderson S, Fallon P, Zurawski G, Murray R, Grencis R, McKenzie A N. Impaired development of Th2 cells in IL-13-deficient mice. Immunity. 1998;9:423–432. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80625-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKenzie G J, Fallon P, Emson C L, Grencis R, McKenzie A N. Simultaneous disruption of Interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 defines individual roles in T helper cell type 2-mediated responses. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1565–1572. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.10.1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mocci S, Coffman R L. Induction of a Th2 population from a polarized Leishmania-specific Th1 population by in vitro culture with IL-4. J Immunol. 1995;154:3779–3787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mocci S, Coffman R L. The mechanism of in vitro T helper cell type 1 to T helper cell type 2 switching in highly polarized Leishmania major-specific T cell populations. J Immunol. 1997;158:1559–1564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mohrs M, Lederman B, Koehler G, Dorfmueller A, Gessner A, Brombacher F. Differences between IL-4 and IL-4Rα deficient mice in chronic leishmaniasis reveal a protective role for IL-13 receptor signaling. J Immunol. 1999;162:7302–7308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noben-Trauth N, Shultz L D, Brombacher F, Urban J F, Gu H, Paul W E. An interleukin 4 (IL-4)-independent pathway for CD4+ T cell IL-4 production is revealed in IL-4 receptor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10838–10843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Noben-Trauth N P, Kropf P, Mueller I. Susceptibility to Leishmania major infection in interleukin-4-deficient mice. Science. 1996;271:987–990. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okamura H, Kashiwamura S-I, Tsutsui H, Yoshimoto T, Nakanishi K. Regulation of interferon-γ production by IL-12 and IL-18. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:529. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rudolphi A, Enssle K H, Claesson M H, Reimann J. Adoptive transfer of low numbers of CD4+ T cells into SCID mice chronically treated with soluble IL-4 receptor does not prevent engraftment of IL-4-producing T cells. Scand J Immunol. 1993;38:57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1993.tb01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sadick M D, Heinzel F P, Holaday B J, Pu R T, Dawkins R S, Locksley R M. Cure of murine leishmaniasis with anti-interleukin 4 monoclonal antibody. Evidence for a T cell-dependent, interferon gamma-independent mechanism. J Exp Med. 1990;171:115–127. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sato T A, Widmer M B, Finkelman F D, Madani H, Jacobs C A, Grabstein K H, Maliszewski C R. Recombinant soluble murine IL-4 receptor can inhibit or enhance IgE responses in vivo. J Immunol. 1993;150:2717–2723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Satoskar A, Brombacher F, Dai W J, McInnes I, Liew F Y, Alexander J, Walker W. SCID mice reconstituted with IL-4-deficient lymphocytes, but not immunocompetent lymphocytes, are resistant to cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 1997;159:5005–5013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seder R A, Gazzinelli R, Sher A, Paul W E. Interleukin 12 acts directly on CD4+ T cells to enhance priming for interferon gamma production and diminishes interleukin 4 inhibition of such priming. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10188–10192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shire D. Open exchange of reagents and information useful for the measurement of cytokine mRNA levels by PCR. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1993;4:161–162. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swain S L, Weinberg A D, English M, Huston G. IL-4 directs the development of Th2-like helper effectors. J Immunol. 1990;145:3796–3806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sypek J P, Chung C L, Mayor S E, Subramanyam J M, Goldman S J, Sieburth D S, Wolf S F, Schaub R G. Resolution of cutaneous leishmaniasis: interleukin 12 initiates a protective T helper type 1 immune response. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1797–1802. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Szabo S J, Dighe A S, Gubler U, Murphy K M. Regulation of the interleukin (IL)-12R beta2 subunit expression in developing T helper 1 (Th1) and Th2 cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:817–824. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takeda K, Tsutsui H, Yoshimoto T, Adachi O, Yoshida N, Kishimoto T, Okamura H, Nakanishi K, Akira S. Defective NK cell activity and Th1 response in IL-18-deficient mice. Immunity. 1998;8:383–390. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Titus R G, Ceredig R, Cerottini J C, Louis J A. Therapeutic effect of anti-L3T4 monoclonal antibody GK1.5 on cutaneous leishmaniasis in genetically-susceptible BALB/c mice. J Immunol. 1985;135:2108–2114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zurawski G, de Vries J E. Interleukin 13, an interleukin 4-like cytokine that acts on monocytes and B cells, but not on T cells. Immunol Today. 1994;15:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]