Abstract

Background

Cancer-related financial hardship can negatively impact financial well-being and may prevent adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors (ages 15–39) from gaining financial independence. This analysis explored the financial experiences following diagnosis with cancer among AYA survivors.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional, anonymous survey of a national sample of AYAs recruited online. The Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST) and InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale (IFDFW) assessed financial hardship (cancer-related and general, respectively), and respondents reported related financial consequences and financial coping behaviors (both medical and non-medical).

Results

Two hundred sixty-seven AYA survivors completed the survey (mean 8.3 years from diagnosis). Financial hardship was high: mean COST score was 13.7 (moderate-to-severe financial toxicity); mean IFDFW score was 4.3 (high financial stress). Financial consequences included post-cancer credit score decrease (44%), debt collection contact (39%), spending more than 10% of income on medical expenses (39%), and lacking money for basic necessities (23%). Financial coping behaviors included taking money from savings (55%), taking on credit card debt (45%), putting off major purchases (45%), and borrowing money (42%). In logistic regression models, general financial distress was associated with increased odds of experiencing financial consequences and engaging in both medical- and non-medical-related financial coping behaviors.

Discussion

AYA survivors face long-term financial hardship after cancer treatment, which impacts multiple domains, including their use of healthcare and their personal finances. Interventions are needed to provide AYAs with tools to navigate financial aspects of the healthcare system; connect them with resources; and create systems-level solutions to address healthcare affordability.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Survivorship care providers, particularly those who interact with AYA survivors, must be attuned to the unique risk for financial hardships facing this population and make efforts to increase access available interventions.

Keywords: Financial toxicity, Young adult, Cancer survivorship, AYA

Background

The high costs of cancer care, coupled with the disruptions to employment and earnings caused by cancer, its treatment, and the late effects of treatment, often result in financial hardship for cancer survivors [1, 2]. This hardship, which includes medical debt, difficulty paying out-of-pocket expenses, and associated psychosocial distress, can negatively impact financial well-being and may prevent adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors from gaining financial independence [3–6]. Survivors of AYA cancers are more likely to experience medical financial hardship than adults with no cancer history, and AYA survivors are more likely than older survivors to face financial hardship after treatment [4, 7–9].

An emergent body of evidence suggests financial hardship among AYA survivors is associated with inferior quality survivorship care, medication non-adherence, and diminished psychosocial well-being [9–13]. However, the longer term effects on personal finances, along with the impact on other components of healthcare use (e.g., vision, dental, mental health care), are not well-studied among AYAs. This analysis explored the financial experiences of a sample of AYA cancer survivors recruited online. Specifically, it sought to determine associations between financial hardship and material financial burden, including associated consequences and coping behaviors.

Methods

Design, subjects, and recruitment

This was a cross-sectional, anonymous online survey of a national sample of AYAs with a history of cancer, who were over 18 years of age or older and treated prior to age 40. The survey was conducted in English, and survivors of all disease types and treatment phases were eligible. The study was approved as exempt research by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Institutional Review Board. Data were collected from December 2020 to March 2021 using REDCap, a secure online platform [14]. Respondents were not paid for their participation. Given that data collection occurred during a peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, we sought to distinguish events specifically related to COVID-19 (e.g., job loss because of COVID-19, shift to remote work) from those that occurred prior to the pandemic. Questions relating to COVID-19 were analyzed separately, and these results are reported elsewhere [15].

Subjects were recruited online through multiple, concurrent methods, including (1) collaboration with AYA cancer advocacy organizations and programs (e.g., Expect Miracles Foundation, Stupid Cancer, Elephants and Tea, Teen Cancer America) to recruit through their social media channels (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, as applicable), email lists, and listservs; (2) tweets and Facebook posts by study investigators and the study account, which were then shared by their networks; (3) sharing of the study by program staff of hospital-based AYA programs throughout the USA; (4) purchase of Facebook and Instagram advertisements and use of paid promoted tweets on Twitter to promote the study.

Measurement

In this analysis, “financial experiences” were defined as respondents’ measured financial hardship and their self-reported material financial burden, both described below.

To gain a more complete understanding of financial hardship, and because of the lack of AYA-specific financial hardship measures, we assessed (1) overall financial distress and (2) financial toxicity related to cancer. Overall financial distress was measured using the InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale (IFDFW), a validated 8-item scale. Respondents selected an answer choice from 1 to 10, and scores were averaged, with lower scores representing worse financial distress [16]. Severity thresholds were as follows: scores 1–4 indicated overwhelming to high distress; scores 5–7 indicated average to low distress; and scores 8–0 indicated very low to no distress. The financial toxicity of cancer was measured using the Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST), an 11-question validated tool. Objective and subjective components of financial toxicity were rated on a 0–4 scale with a 0–44 composite score, with lower scores suggesting worse financial toxicity [17]. COST tool thresholds for severity of financial toxicity were based on thresholds previously published in the literature: scores 0–13 indicated severe financial toxicity; scores 14–25 indicated moderate financial toxicity; and scores over 25 indicated low to no financial toxicity [18, 19].

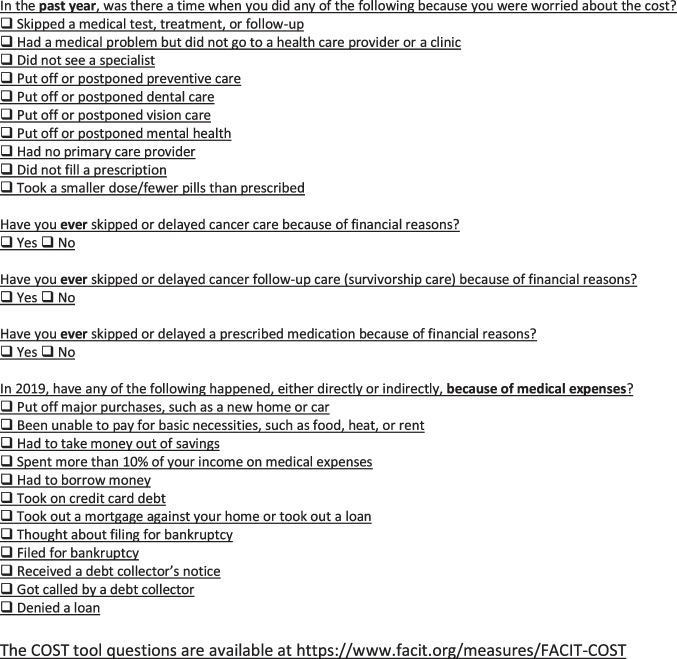

To understand material financial burden, we relied on a conceptualization proposed by Jones and colleagues, in which material financial burden is comprised of both financial consequences and financial coping behaviors [20]. Financial consequences refer to the difficulties associated with bill-paying, and financial coping behaviors are actions taken by the patient to ensure needs are met; both consequences and coping behaviors may be related to healthcare or non-healthcare expenses or circumstances. To assess financial consequences, respondents answered investigator-designed yes/no questions relating to methods of medical bill payment (or non-payment) and negative events associated with medical bills (e.g., bankruptcy thoughts/filing, using savings for bills); they also estimated their annual out-of-pocket expenses, student loan debt, and credit card debt. Financial coping behaviors were measured using questions relating to skipping or delaying components of healthcare derived from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey and investigator-designed yes/no questions about general cost-coping (e.g., delaying purchases, borrowing money) [21].

Respondents self-reported relevant demographic (e.g., current age, race/ethnicity, employment status, income, education) and clinical (e.g., diagnosis, treatment status, recurrence status, age at diagnosis) information.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequencies, central tendency) characterized the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. The IFDFW and COST tools were scored according to validated guidelines. Univariable testing (e.g., t-tests, Pearson correlation, ANOVA) assessed associations with IFDFW and COST scores among variables of interest (i.e., out-of-pocket payment methods, financial consequences, financial cost-coping).

For financial consequences and financial coping behaviors, logistic regression models were constructed among variables significant in univariate testing (p < 0.05) to explore association with IFDFW score (i.e., overall financial distress), controlling for current age, race/ethnicity, treatment status, education, income, and full-time employment. For financial cost-coping, we considered both medical-related cost-coping (e.g., skipping treatment, not taking prescribed medication) and general cost-coping (e.g., taking on credit card debt, delaying purchases). Because lower scores represent worse outcomes on the IFDFW, we report the inverse of the adjusted odds ratio for ease of interpretation.

Results

Sample

Of 410 potential respondents who clicked on the survey, eight were ineligible due to age ≥ 40 years at diagnosis. Among the remaining 402 eligible respondents, 71 did not start the survey once entering it. Of respondents who started the survey (n = 331), 267 provided evaluable data, which we defined as at least completing the IFDFW and COST measures and including an age-eligible response to the question on age at diagnosis (completion rate = 81%). Mean respondent age was 27.0 years at diagnosis (sd = 7.50) and 35.3 years (sd = 5.30) at time of survey. The sample predominantly identified as women (87%) and included 8% men and 2% non-binary or transgender respondents; 3% did not report their gender. Breast cancer (27%), lymphoma (17%), leukemia (11%), and colorectal cancer (10%) were the most common diagnoses. The majority of the sample (58%) reported they had finished all cancer treatment, with 26% still receiving hormonal therapy and 14% undergoing active treatment; 35% had experienced metastasis, recurrence, or a second cancer after their initial diagnosis. Ninety-seven percent of the sample had health insurance: most (73%) had private insurance, with 12% Medicare and 9% Medicaid.

The sample was comprised of 70% non-Hispanic white respondents, 10% Hispanic/Latino/a/x, 6% non-Hispanic Black, 6% multiple race/ethnicities, and 3% Asian. Overall, 70% had completed at least a bachelor’s degree, and 53% were partnered/married. The most frequently reported income range at diagnosis was $25,000–$49,999 (30%) and $50,000–$100,000 (36%) at survey completion. Among respondents reporting student loan debt (n = 151), mean debt was $63,398 (sd = 72,319.27). Sixty percent of the sample (n = 161) reported having credit card debt: mean debt was $10,243 (sd = 13,593.46). A majority of respondents (55%) was employed full-time at survey completion; 14% were on long-term disability; 9% were students; and 8% were unemployed at survey completion [Respondents could select more than one answer choice]. Complete sample demographics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample demographics and clinical information (N = 267)

| No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Woman | 232 (86.9) |

| Man | 22 (8.2) |

| Trans man | 2 (0.7) |

| Non-binary | 4 (1.5) |

| Prefer not to respond | 7 (2.6) |

| Race | |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino/a/x White | 188 (70.4) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino/a/x Black | 15 (5.6) |

| Hispanic/Latino/a/x | 27 (10.1) |

| Asian | 7 (2.6) |

| Native American/American Indian | 1 (0.4) |

| More than once race | 17 (6.4) |

| Prefer not to respond | 12 (4.5) |

| Current relationship status | |

| Single/not living with partner | 106 (39.7) |

| Married/living with partner | 141 (52.8) |

| Widowed, divorced, or separated | 11 (4.1) |

| Prefer not to respond/something else | 9 (3.4) |

| Highest education | |

| High school | 9 (3.4) |

| Some college or vocational training | 39 (14.6) |

| Associate’s degree | 22 (8.2) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 81 (30.3) |

| Graduate or professional degree | 108 (40.4) |

| Prefer not to respond | 8 (3.0) |

| Current household income | |

| Less than $25,000 | 36 (13.5) |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 49 (18.4) |

| $50,000–$99,999 | 95 (35.6) |

| $100,000 or more | 63 (23.6) |

| Prefer not to respond | 24 (9.0) |

| Employment statusa | |

| Working full-time | 95 (54.9) |

| Working part-time | 15 (8.7) |

| Homemaker/stay-at-home parent | 14 (8.1) |

| In school | 12 (6.9) |

| On disability (short or long term) | 31 (17.9) |

| Unemployed | 13 (7.6) |

| Prefer not to respond | 10 (5.8) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Breast | 70 (26.2) |

| Lymphoma | 45 (16.9) |

| Colorectal | 27 (10.1) |

| Brain | 19 (7.1) |

| Leukemia | 30 (11.2) |

| Gynecologic | 16 (6.0) |

| Sarcoma | 18 (6.7) |

| Thyroid | 10 (3.7) |

| Other | 22 (8.2) |

| Prefer not to respond/missing | 10 (3.7) |

| Annual out-of-pocket expenses estimate | |

| < $500 | 32 (12.0) |

| $500–$999 | 25 (9.4) |

| $1000–1999 | 33 (12.4) |

| $2000–4999 | 75 (28.1) |

| $5000 + | 77 (28.8) |

| Don’t know | 25 (9.4) |

| Payment methodsa | |

| Checking/general savings | 218 (81.6) |

| Health savings account (HSA) | 72 (27.0) |

| Specific health care savings account (non-HSA) | 19 (7.1) |

| Low or no interest medical credit card | 14 (5.2) |

| Traditional credit card | 100 (37.5) |

| Loan | 16 (6.0) |

| Parent/other family pays full cost | 15 (5.6) |

| Parent/other family pays part of cost | 57 (21.3) |

| Crowdfunding | 20 (7.5) |

| Did not pay some/all costs | 49 (18.4) |

| Treatment status | |

| Active treatment | 37 (13.9) |

| Receiving hormonal/endocrine therapy | 70 (26.2) |

| Completed treatment | 155 (58.1) |

| Prefer not to respond | 5 (1.2) |

| Insurance type | |

| Private | 195 (73.0) |

| Medicaid | 25 (9.3) |

| Medicare | 32 (12.0) |

| Other plan | 6 (2.2) |

| No insurance | 8 (3.0) |

| Don’t know | 1 (0.3) |

aRespondents could select more than one answer choice

Overall financial distress and financial toxicity

Mean IFDFW score (i.e., overall financial distress) was 4.3 (sd = 2.38): 35% of the sample scored 1–2, which IFDFW authors characterize as “overwhelming/severe financial distress”; 28% scored 3–4, or “high financial distress”; 23% scored 5–6, or “average financial distress”; and 14% scored 7–10, or “low or no financial distress”[16]. Mean COST score (i.e., cancer-related financial toxicity) was 13.7 (sd = 9.09): 54% of respondents had severe financial toxicity (COST < 14); 36% had moderate (COST 14–25); and 11% had low/no financial toxicity (COST ≥ 26).

In univariate correlation testing, IFDFW and COST scores were highly and significantly correlated (r = 0.85, p < 0.001). As such, both lower financial distress and less cancer-related financial toxicity were associated with older age at survey, more education, and higher current income. Lacking full-time employment and having credit card debt were also associated with worse financial distress and worse financial toxicity. Race/ethnicity, relationship status, and student loan debt were not significantly associated with COST scores but were associated with IFDFW scores, such that respondents who identified as Black, Indigenous, or a person of color (BIPOC); single respondents; and those with student loan debt had significantly higher financial distress. Age at diagnosis, treatment status, and recurrence, metastasis, or development of a second cancer were not associated with either IFDFW or COST scores (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariable analyses

| Comparison of means | IFDFWa mean | p-value | COSTb mean | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-time employment | < .001 | < .001 | ||

| Yes | 4.81 | 15.75 | ||

| No | 3.66 | 11.19 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | .012 | .15 | ||

| White non-Hispanic | 4.49 | 13.95 | ||

| Black, Indigenous, or person of color | 3.60 | 12.12 | ||

| Student loan debt | .012 | .07 | ||

| Yes | 3.97 | 12.95 | ||

| No | 4.92 | 15.37 | ||

| Credit card debt | < .001 | < .001 | ||

| Yes | 3.57 | 11.19 | ||

| No | 6.55 | 20.98 | ||

| Marital/partner status | .02 | .05 | ||

| Single | 3.76 | 11.94 | ||

| Married/partnered | 4.63 | 14.75 | ||

| All others | 4.88 | 13.38 | ||

| Recurrence, metastasis, second cancer | .56 | .70 | ||

| Yes | 4.44 | 13.42 | ||

| No | 4.24 | 13.88 | ||

| Formal education | < .001 | < .001 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 4.79 | 15.00 | ||

| Less than bachelor’s degree | 2.93 | 9.68 | ||

| Current annual income | < .001 | < .001 | ||

| < $25,000 | 2.29 | 6.05 | ||

| $25,000–$49,999 | 3.29 | 11.12 | ||

| $50,000–$99,999 | 4.32 | 13.98 | ||

| $100,000 or more | 6.24 | 19.25 | ||

| Treatment status | .36 | .15 | ||

| Active treatment | 3.80 | 11.21 | ||

| Receiving hormonal therapy | 4.20 | 13.41 | ||

| Finished with all treatment | 4.46 | 14.41 | ||

| Did not pay some/all of out-of-pocket expenses | < .001 | < .001 | ||

| Yes | 2.68 | 9.10 | ||

| No | 4.69 | 14.76 | ||

| Took out a loan to pay medical bills | < .001 | < .001 | ||

| Yes | 2.16 | 6.31 | ||

| No | 4.43 | 14.19 | ||

| Receive family help with out-of-pocket costs | .001 | < .001 | ||

| Yes | 3.42 | 9.58 | ||

| No | 4.59 | 15.00 | ||

| Paid for bills with a health savings account | < .001 | < .001 | ||

| Yes | 5.31 | 17.43 | ||

| No | 3.92 | 12.35 | ||

| Used crowdfunding to pay medical bills | .013 | .15 | ||

| Yes | 2.87 | 10.92 | ||

| No | 4.41 | 13.94 | ||

| Correlationsc | IFDFW | p-value | COST | p-value |

| Age at diagnosis | .05 | .47 | .04 | .50 |

| Age now | .14 | .04 | .15 | .02 |

| Education | .35 | < .001 | .25 | < .001 |

| Income | .43 | < .001 | .40 | < .001 |

aInCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale, scored 1 = 10 with lower scores indicating worse financial well-being

bComprehensive Scale for Financial Toxicity, scored 0–44 with lower scores indicating worse financial toxicity

cPearson r correlation

Material financial burden: financial consequences

Financial consequences related to medical expenses included debt collection contact (39%), spending more than 10% of income on medical expenses (39%), lacking money to pay for basic necessities (23%), loan denial (20%), and thoughts about and/or filing for bankruptcy (14%). Of respondents who could report their credit status (n = 209), 44% said their credit score went down after cancer (vs. 29% went up and 27% stayed the same). Experiencing any of these events was associated with worse overall financial distress and cancer-related financial toxicity in univariable testing; in multivariable models, worse financial distress was associated with experiencing any negative financial consequences, including lacking money for basic necessities (aOR = 2.31, 95% CI = 1.64, 3.26) and debt collection contact (aOR = 1.52, 95% CI = 1.27, 1.83) (see Table 3 for complete results).

Table 3.

Multivariable associations of IFDFW with financial coping behaviors and financial consequences

| Odds ratio estimate | 95% Confidence interval | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial coping behaviors | ||||

| Lifetimeb | ||||

| Skipped/delayed cancer treatment | 1.46 | 1.16 | 1.85 | < .001 |

| Skipped/delayed survivorship care | 1.35 | 1.14 | 1.91 | < .001 |

| Did not take medication as prescribed | 1.43 | 1.20 | 1.71 | < .001 |

| Past yearc | ||||

| Skipped medical test or appointment | 1.64 | 1.35 | 2.01 | < .001 |

| Had a health problem but did not see provider | 1.63 | 1.33 | 1.99 | < .001 |

| Skipped/delayed preventative care | 1.41 | 1.19 | 1.68 | < .001 |

| Skipped/delayed dental care | 1.33 | 1.14 | 1.56 | < .001 |

| Skipped/delayed vision care | 1.20 | 1.03 | 1.39 | 0.02 |

| Skipped/delated mental health care | 1.40 | 1.19 | 1.66 | < .001 |

| Did not see a specialist | 1.71 | 1.38 | 2.11 | < .001 |

| Did not fill a prescription | 1.38 | 1.12 | 1.69 | 0.002 |

| Took fewer pills than prescribed | 1.49 | 1.16 | 1.92 | 0.001 |

| In 2019 (Pre-Covid) | ||||

| Put off purchase | 1.32 | 1.13 | 1.55 | < .001 |

| Borrowed money | 1.47 | 1.24 | 1.76 | < .001 |

| Took on credit card debt | 1.97 | 1.58 | 2.45 | < .001 |

| Financial consequences | ||||

| In 2019 (Pre-Covid) | ||||

| Could not afford basic necessities | 2.31 | 1.64 | 3.26 | < .001 |

| Took money from savings | 1.38 | 1.17 | 1.62 | < .001 |

| Spent more than 10% of income on healthcare | 1.46 | 1.22 | 1.74 | < .001 |

| Contacted by debt collector | 1.52 | 1.27 | 1.83 | < .001 |

| Thought about or filed for bankruptcy | 2.62 | 1.69 | 4.07 | < .001 |

| Denied a loan | 1.75 | 1.32 | 2.30 | < .001 |

InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale, scored 1 = 10 with lower scores indicating worse financial well-being; models controlled for current age, race/ethnicity, education, treatment status, income, full-time employment, and reported findings represent odds of engaging in practice for each one point decrease in scale

bRespondents reported if they had ever engaged in the named practice because of the cost

cRespondents reported if they had engaged in the named practice because of the cost in the past year

Nearly all respondents (94%) reported they were financially responsible for their health care costs, as opposed to a parent or someone else. Among estimates of annual out-of-pocket expenses, 19% of respondents reported expenses “greater than $5000” and 28% endorsed out-of-pockets costs between $2000 and $5000 (28%); 39% of the sample estimated they spent > 10% of their annual income on healthcare costs (see Table 1).

Frequently endorsed methods of payment of out-of-pocket expenses were from a checking account/general savings (82%), traditional credit card (38%), and/or a designated health savings account (27%) [categories not exclusive]. Twenty-four percent of respondents received help with some or all of their costs from parents/family; 18% reported that they did not pay some portion of their out-of-pocket costs; 8% used crowdfunding methods; and 6% took out a loan for medical bills.

In multivariable analysis (see Table 3), controlling for current age, race/ethnicity, treatment status, education, income, and full-time employment, more financial distress was associated with an increased odds of not paying out-of-pocket expenses (aOR = 1.51, 95% CI = 1.17, 1.94), taking out a loan to pay medical bills (aOR = 1.97, 95% CI = 1.17, 3.72), and having other people pay some/all of medical costs (aOR = 1.23, 95% CI = 1.02,1.47). Less financial distress was associated with an increased likelihood of using a health savings account (aOR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.02, 1.41).

Material financial burden: financial coping behaviors

General financial coping behaviors included taking money out of savings (55%), taking on credit card debt (45%), putting off a major purchase (45%), and borrowing money (42%). Related to healthcare, respondents endorsed whether they had ever skipped or delayed cancer care (23%) or survivorship care (36%) because of the cost, and if, in the past year, they skipped or delayed seeing a specialist (30%); seeing a provider for a medical problem (35%); or utilizing preventative care (37%), vision care (38%), dental care (53%), or mental health care (45%) because of the cost. Skipping or delaying any element of healthcare was associated with worse financial distress and worse financial toxicity in univariate testing. Respondents also reported ever skipping or delaying prescribed medication (40%) and doing so in the past year (29%). Both practices were associated with worse financial distress and toxicity in univariate testing.

In multivariable models controlling for current age, race/ethnicity, treatment status, education, income, and full-time employment, worse financial distress led to increased odds of engaging in any healthcare-related cost-coping (e.g., skipping survivorship care [aOR = 1.35, 95% CI = 1.14, 1.91]; forgoing mental health care [aOR = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.19, 1.66]) or general cost-coping behavior [(e.g., putting off major purchases [aOR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.13, 1.55]; borrowing money [aOR = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.24, 1.76]) (see Table 3 for complete results).

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate the long-term financial consequences experienced by AYA survivors and highlight their financial coping mechanisms, including limiting their use of healthcare. Respondents, who were on average 8.3 years from their diagnosis, faced both healthcare- and non-healthcare-related financial consequences, as well as high levels of financial hardship (i.e., overall financial distress and cancer-specific financial toxicity). This hardship increased the odds of engaging in general and medical-related financial cost-coping behaviors, both with potentially negative outcomes. This study also highlights the association of overall financial distress with ongoing healthcare needs potentially necessitated by late and long-term effects of treatment (e.g., mental health care, dental treatment, vision care) and with non-medical financial concern [10, 13].

In our sample, cancer-related financial toxicity, as measured by the COST tool, was worse than that reported elsewhere in AYA samples, likely owing to our recruitment strategies [9, 10, 22]. We found that BIPOC race/ethnicity, lower education, and lower income were all associated with worse financial hardship in this AYA sample—findings that align with prior research and demonstrate the systemic effects of structural inequalities and discriminatory practices [2, 23]. For AYAs, given their age and developmental stage, financial challenges include education-associated debt, the costs associated with starting and raising a family (which can be exacerbated by treatment-related infertility), and achieving financial independence despite having a “bad” or limited credit history, low/no savings, and a disrupted employment history [24]. These challenges, combined with other concerns that may disproportionally affect young adults (YA) (e.g., insurance instability, job lock, employment turnover), create an environment that reinforces ongoing financial hardship and stymies adult financial stability [25–27].

Despite a recent emergence of commentaries and reviews addressing financial hardship among AYA survivors, the issue—and, more importantly, interventions to address it—remain understudied, particularly among historically and systematically excluded populations [6, 11, 28–30]. Promising efforts have been made toward disease- and treatment-focused research and among specific populations, including YA survivors in the military and YA women in the workforce; these studies demonstrate a need for tailored interventions to address the unique concerns experienced within disparate populations [31, 32]. Findings from our study highlight a key theme for future AYA financial hardship-related research: expanding samples to include family, caregivers, and care partners, as loan denials, bankruptcy, and other negative effects may impact the entire family unit [30, 33]. Another ongoing need for AYA financial hardship research, as others have noted, is a measurement tool that is specifically tailored to and/or validated in the AYA population, given that currently available tools cover topics that may not yet be directly applicable to younger AYAs or those who are not yet financially independent (e.g., retirement savings, contributions to household incomes) and do not include topics that are more likely to be relevant to younger respondents (e.g., childcare costs, student loan repayment) [34]. In the absence of such a tool, our use of both the IFDFW and COST was supported by their high internal consistency (IFDFW: α = 0.95; COST: α = 0.87), which we have seen in our previous work as well, and our study was the first, to our knowledge, to use both tools in an AYA sample [10, 15].

Financial hardship, particularly among AYAs, is a multifaceted problem, and future intervention work must reach across systems in order to achieve maximum impact [35]. Findings from this study demonstrate the hardship AYA survivors face nearly a decade post-diagnosis. We, as well as others, have previously highlighted the need to provide cancer patients with financial navigation and increase their health cost literacy (i.e., ability to understand financial concepts related to care) and health insurance literacy [36–39]. For AYAs, who may still be developing their financial capability and may have limited experience with the healthcare system, these tools help them to engage in cost-related discussions with their providers, which we have shown to be promising in reducing out-of-pocket expenses [39, 40]. These interventions, however, must be embedded within broader systemic efforts to effect meaningful, sustainable change. While empowering AYAs with the knowledge to make informed decisions about insurance type and participate in cost-related discussions with their healthcare teams may improve their self-efficacy to manage healthcare and other expenses, the current flaws of the US healthcare system, including a lack of cost transparency and insurance coverage variations due to erosion of Affordable Care Act policies, impede meaningful progress [41, 42]. Frameworks to understand financial hardship, such as the conceptualization used in this study by Jones and colleagues and recently published, patient-centered work by Danhauer and colleagues, will be useful in structuring research that considers systemic effects [20, 43].

Our findings are limited by the cross-sectional nature of our study design, which precludes inferences about causation. In addition, we are limited by our use of a convenience sample and the resulting lack of gender, racial/ethnic, and educational diversity, which influences the generalizability of our results, although even with limited numbers we do demonstrate that groups typically under-represented or excluded show worse financial hardship, which is consistent with prior research. Our use of a convenience sample may have also caused us to attract and recruit respondents who were experiencing extreme hardship, as evidenced by our comparably high levels of financial hardship. Furthermore, our sample was comprised mostly of women, who, in prior research, have been found to be at higher risk for financial hardship [2, 5]. Findings in this study, particularly those related to employment, financial toxicity and distress, and elements of financial hardship, were also likely influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, as our data collection occurred in late 2020 and early 2021. As noted in our methodology, we attempted to mitigate this impact by structuring the survey so that respondents were asked to recall events prior to the pandemic, and we included specific questions about the economic impact of COVID-19 (e.g., job/insurance loss because of the pandemic, credit card debt increase since the pandemic). Nonetheless, it is highly likely that responses were shaped by individual experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it may be impossible to fully disentangle pre-COVID events, feelings, and practices.

Conclusion

These findings illustrate the profound, durable consequences of financial hardship after cancer treatment among AYA cancer survivors. Comprehensive interventions are needed to provide AYAs the requisite tools to navigate financial aspects of the healthcare system; connect them with resources toward gaining financial independence; and create systems-level solutions to address healthcare affordability.

Appendix. Survey questions

Author contribution

Conceptualization, study design, data collection: BT, DNF, CB, SEW, MSZ, FC; data analysis: BT, EMA; data interpretation, manuscript writing and revision, final manuscript approval: all authors.

Funding

This manuscript was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 and the Chanel Endowment to Fund Survivorship Research.

Data availability

De-identified data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, BT, pending permission from the Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) Institutional Review Board (IRB) and a signed data sharing agreement between institutions. The data are not publicly available due to the privacy of research participants.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The MSK IRB reviewed this study and determined it to be exempt per 45 CFR 46.104(d)(2).

Consent to participate

Because the MSK IRB classified this study as exempt, written consent was not obtained; however, potential participants were informed of the anonymous and voluntary nature of the research and that they could leave the study at any time.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, Part I: a new name for a growing problem. Oncology. 2013;27(2):80–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yabroff KR, et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(3):259–267. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landwehr MS, Watson SE, Dolphin-Krute M. Healthcare costs and access for young adult cancer survivors: a snapshot post ACA. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(10 Spec No.):Sp440-sp441. [PubMed]

- 4.Landwehr MS, et al. The cost of cancer: a retrospective analysis of the financial impact of cancer on young adults. Cancer Med. 2016;5(5):863–870. doi: 10.1002/cam4.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altice CK, et al. Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Ghazal LV, et al. Financial toxicity in adolescents and young adults with cancer: a concept analysis. Cancer Nurs. 2021;44(6):E636–e651. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu AD, et al. Medical financial hardship in survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(8):997–1004. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng Z, et al. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer. 2019;125(10):1737–1747. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdelhadi OA, et al. Psychological distress and associated additional medical expenditures in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2022;128(7):1523–1531. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thom B, Benedict C. The impact of financial toxicity on psychological well-being, coping self-efficacy, and cost-coping behaviors in young adults with cancer. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Salsman JM, et al. Understanding, measuring, and addressing the financial impact of cancer on adolescents and young adults. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(7):e27660. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith AW, et al. Understanding care and outcomes in adolescents and young adult with cancer: a review of the AYA HOPE study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(1):e27486. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaul S, et al. Cost-related medication nonadherence among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2017;123(14):2726–2734. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris PA, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thom B, et al. Economic distress, financial toxicity, and medical cost-coping in young adult cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from an online sample. Cancer. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Prawitz AD, et al. InCharge financial distress/financial well-being scale: development, administration, and score interpretation. Financ Couns Plan. 2006;17(1):34–50. [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Souza JA, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: the validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity. Cancer. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Esselen KM, et al. Evaluating meaningful levels of financial toxicity in gynecologic cancers. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Souza JAD, et al. Validation of a financial toxicity (FT) grading system. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15_suppl):6615–6615. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.6615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones SM, et al. A theoretical model of financial burden after cancer diagnosis. Future Oncol. 2020;16(36):3095–3105. doi: 10.2217/fon-2020-0547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). 2021 [cited 2022; Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/data/meps.html. [PubMed]

- 22.Ou JY, et al. Financial burdens during the COVID-19 pandemic are related to disrupted healthcare utilization among survivors of adolescent and young adult cancers. J Cancer Surviv. 2022;1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Panzone J, et al. Association of race with cancer-related financial toxicity. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;Op2100440. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Kayser K, et al. Living with the financial consequences of cancer: a life course perspective. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2021;39(1):17–34. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2020.1814933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parsons HM, et al. Young and uninsured: Insurance patterns of recently diagnosed adolescent and young adult cancer survivors in the AYA HOPE study. Cancer. 2014;120(15):2352–2360. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsons HM, et al. Early impact of the patient protection and affordable care act on insurance among young adults with cancer: analysis of the dependent insurance provision. Cancer. 2016;122(11):1766–1773. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirchhoff AC, et al. “Job lock” among long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. JAMA Oncol. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Cheung CK, et al. A call to action: antiracist patient engagement in adolescent and young adult oncology research and advocacy. Future Oncol. 2021;17(28):3743–3756. doi: 10.2217/fon-2020-1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doherty MJ, Thom B, Gany F. Evidence of the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of oncology financial navigation: a scoping review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(10):1778–1784. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirchhoff A, Jones S. Financial toxicity in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: proposed directions for future research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Cheung CK, et al. Capturing the financial hardship of cancer in military adolescent and young adult patients: a conceptual framework. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2021;1–18. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Meernik C, et al. Material and psychological financial hardship related to employment disruption among female adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2020;127(1):137–148. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nightingale CL, et al. Financial burden for caregivers of adolescents and young adults with cancer. Psychooncology. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Salsman JM, et al. Systematic review of financial burden assessment in cancer: evaluation of measures and utility among adolescents and young adults and caregivers. Cancer. 2021;127(11):1739–1748. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salsman JM, Kircher SM. Financial hardship in adolescent and young adult oncology: the need for multidimensional and multilevel approaches. JCO Oncol Pract. 0(0):OP.21.00663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Waters AR, et al. “I thought there would be more I understood”: health insurance literacy among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(5):4457–4464. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-06873-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aviki EM, et al. Patient-reported benefit from proposed interventions to reduce financial toxicity during cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(3):2713–2721. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06697-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thom B, et al. The intersection of financial toxicity and family building in young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2018;124(16):3284–3289. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zafar SY, et al. Cost-related health literacy: a key component of high-quality cancer care. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(3):171–173. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.004408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zafar SY, et al. The utility of cost discussions between patients with cancer and oncologists. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(9):607–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moss HA, et al. Declines in health insurance among cancer survivors since the 2016 US elections. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(11):e517. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30623-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chino F, Johnson J, Moss H. Compliance with price transparency rules at US national cancer institute-designated cancer centers. jaMA Oncol. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Danhauer SC, et al. Stakeholder-informed conceptual framework for financial burden among adolescents and young adults with cancer. Psychooncology. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

De-identified data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, BT, pending permission from the Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) Institutional Review Board (IRB) and a signed data sharing agreement between institutions. The data are not publicly available due to the privacy of research participants.