Abstract

Introduction

Women, Infants and Children (WIC) nutrition professionals serve as frontline providers for Black families who disproportionately experience poor perinatal outcomes. With racism driving inequities, we developed an antiracism training tailored to WIC. This report describes the training framework, design, components, and evaluation.

Methods

In 2019, with feedback from WIC providers, we created a 3-h antiracism training for Philadelphia WIC nutrition professionals that included an identity reflection, key concept definitions, workplace scenario and debrief, a model for repair and disruption, and an action tool. We implemented this training in August 2019 and surveyed WIC staff trainees’ awareness of racism and skills to address bias before, immediately after, and 6 months post-training, comparing responses at each time point.

Results

Among 42 WIC staff trainees, mean age was 30 years, 56% were white, 91% female, and 74% had no prior antiracism training. Before the training, 48% felt quite a bit or extremely aware of the role of racism in the healthcare system; this increased to 91% immediately after and was 75% 6 months later. Similar increases in confidence identifying and addressing interactions that perpetuate racism were achieved immediately after training, although the magnitude decreased by 6 months. One-third felt quite a bit or extremely confident the training improved participant interactions at the 6-month timepoint. Qualitative feedback reinforced findings.

Discussion

Results suggest antiracism training may improve WIC nutrition professionals’ attitudes, awareness, and actions and could be valuable in efforts to advance health equity. More work is needed to examine how changes translate into improvements for WIC participants.

Keywords: WIC, Antiracism training, Health equity, Cultural humility, Perinatal health disparities

Introduction

In recent years, with the exception of how the police mistreat, harm, and kill Black people, perhaps no other issue around racial justice and inequities has received as much attention and scrutiny as the crisis in Black maternal health [1]. This is due in large part to the organizing and scholarship by Black women and birthing people who, through their own lived experience, research, and community-based efforts, have exposed the racism that has resulted in the extant racial health inequities impacting Black families [2]. Regardless of good intentions, racism impacts the health care environment, the health care provider’s practice, and the participant/patient experience [2, 3]. Many well-intentioned healthcare institutions (e.g., hospitals, nursing homes and health service agencies (e.g., Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children [WIC] struggle with the reality that with regard to perinatal health equity, they are not simply part of the solution but also part of the problem [4, 5, 6]).

This time of increased consciousness around perinatal health inequities and systemic racism is a crucial opportunity to provide needed training, tools, and support to all staff in the maternal child health workforce [7]. Antiracism initiatives have begun in healthcare institutions. However, one overlooked health services agency with a key role in the perinatal landscape for Black birthing people in cities like Philadelphia is WIC. Data reveal that more of the lowest income (i.e., 100% or less of Federal Poverty Level) WIC participants are disproportionately Black and Indigenous families who have significant financial need and corresponding higher incentive to utilize WIC services [8]. While improvements are necessary in how demographic data are collected at WIC, particularly around racial identity [9], nationally, the majority of WIC participants identify as white or non-Black Hispanic people. Contrasting to national demographics of participants, in 2017, almost 75% of all Pennsylvania WIC participants were Black (including those who identify as Black and Hispanic), which is equal to or lower than the proportion in Philadelphia [10]. Black-led advocacy groups as well as the National WIC Association view racial biases as malleable and suggest training staff on racial inequities, antiracism, and bias [11–13], yet neither clear guidelines nor a standard approach for antiracism training targeting WIC staff exist. This lack of antiracism training has significant implications—as of 2017, nationwide eligibility for WIC included more than 2.4 million non-Hispanic Black people [14], indicating that a substantial number of families could be impacted by racism in the WIC program.

While there are promising models being developed for antiracism trainings, such as Crawford Bias Reduction Theory & Training [15] and 5Rs of Cultural Humility [16], there is not yet a specific antiracism methodology or training identified in the literature as having demonstrated consistent, significant, and sustained effectiveness or widespread implementation and dissemination. However, recent meta-analyses [17, 18] reveal several characteristics associated with effective diversity and bias trainings that are likely to translate to antiracism trainings as well: opportunities for social interaction,in-person sessions (ideally at the workplace); disseminated practice (i.e., trainings over more than one session); employer-mandated attendance; and trainings as one part of larger institutional equity efforts. These same studies also recommend strategies to deal with biases that include supporting metacognition, active “debiasing,” and practicing within the framework cultural humility. While there are critiques of implicit bias training efforts in healthcare (e.g., potentially activating rather than mitigating biases) [19, 20], this seems to be a risk if the approach only focuses on awareness of one’s bias and not concrete tools to recognize and manage the impact of the bias on others [20].

Informed by this evidence, in 2019 we developed and implemented an antiracism training for Philadelphia WIC staff, tailored to nutrition professionals, who have the role of counseling all WIC participants. To the best of our knowledge, this report is the first describing an antiracism training for WIC staff and delineates the (a) training framework, (b) design and key training components, and (c) evaluation, including results from 6 months post-training. This work was determined to be non-human subjects research by the Institutional Review Board at Temple University.

Methods

Training Framework

Informed by the lessons from the literature on effective bias trainings, we chose cultural humility as our training’s guiding framework. First developed in the late 1990s by Melanie Tervalon and Jann Murray-García to help address health disparities and institutional inequities in medicine, cultural humility is currently conceptualized as “the ability to maintain an interpersonal stance that is other-oriented in relation to aspects that are most important to the person” [21], p. 354). Key principles of cultural humility include: (1) a lifelong commitment to self-evaluation, -reflection, and -critique,(2) a willingness to right imbalances in power for respectful partnerships; and (3) a recognition of the need for institutional accountability [22]. According to Masters et al. [16], the practice of cultural humility helps promote empathy, mitigate bias, and allows providers to recognize the individuality of the person in their care. Using a cultural humility framework inherently brings more awareness into clinical encounters and incorporates skills identified as reducing biases in healthcare, such as perspective-taking, metacognition, and partnership-building [23, 24], all of which are equally germane to encounters in health service agencies like WIC.

Design and Key Training Elements

Between March and August of 2019, our training team of an Afro-Latinx, hospital-based midwife and antiracism educator and a White, community-based midwife with experience in public health research and bioethics, developed the foundational didactic 3-h antiracism training. In preparation, we held a focus group with WIC staff to elicit their feedback on the training content, including interactive scenarios based on their workplace experiences. Our intention in developing the training was to increase awareness and provide skills to reduce experiences of bias, prejudice, and racism at WIC as well as to make WIC visits more meaningful and less stressful for participants and staff. The five core components of the training are described below.

-

Identity Web Reflection Exercise

We chose to begin the training with an “Identity Web Reflection” exercise to help participants consider how their identity shapes their worldview and an introduction to the concept of cultural humility. This exercise asks WIC staff trainees to: (1) draw a circle around their name in the middle of their paper; (2) put their most important identities, with at least three identities being ones they did not choose (e.g., immigrant, Black, oldest child) in five circles around their name; (3) reflect on questions like “Has belonging to one of these groups ever cost you, either personally or professionally?” and “Are there identity groups to which others assume (correctly or incorrectly) you belong?”; (4) partner with a colleague to share responses, considering which answers offered new insights; and (5) discuss with the group about if/how having more awareness of their personal identities can help them find common ground with one another as well as with WIC participants.

-

Definitions and Concepts in the Context of WIC, Philadelphia, and Perinatal Health Data

We intended to ground antiracism work in the specific context of Philadelphia (e.g., high poverty rates, racially diverse), the role and functions of WIC (e.g., participation coverage rates), and national and local perinatal health data (e.g., Black maternal mortality and morbidity rates). Framing these sobering statistics from a place of empathy acknowledges that WIC staff are being asked to do more with less, just as families experiencing poverty and health inequities are (e.g., they can partner with families to find creative, practical ways to still improve health/outcomes even in the context of less institutional and individual resources). We then planned to define racism, privilege/white privilege, white supremacy, implicit bias and cultural humility, as well as introduce a multilevel framework based on the socio-ecological model of behavior change examining individual, interpersonal, and institutional influences on interactions at WIC.

-

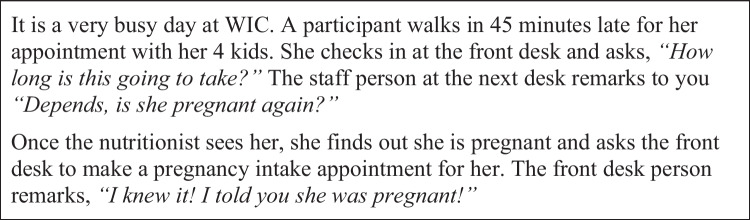

Workplace Scenario and Debrief

Based on focus group input, we prepared an interactive group discussion and debrief about how knowledge of health inequities and social/structural determinants of health impact the care given at WIC using “A Very Busy Day at WIC…” scenario (Fig. 1). WIC staff trainees were asked to apply a cultural humility framework to consider what they would say and do the same or differently in this scenario, and to think through how their response may be impacted by their personal identity and positionality in the workplace, as well as if the WIC participant in the scenario was, for example, White versus Black, or a Muslim person in garb versus a Spanish-speaking participant.

-

Review of a Model for Healing, Repair, and Disruption

Building on this increased awareness of cultural humility in their interactions with WIC participants and/or other staff, we decided to follow the workplace scenario with a simple, effective model for healing and repair, which deconstructs the different roles (e.g., mistake maker, upstander, and bystander) people play in social interactions, especially during conflicts [25]. In order to offer some specific avenues for taking action, we briefly reviewed the 5 Ds of Bystander Intervention (Delay, Delegate, Direct, Distract, Document) drawn from the violence prevention and community safety literature [26], but applied to situations involving racism and bias at WIC.

-

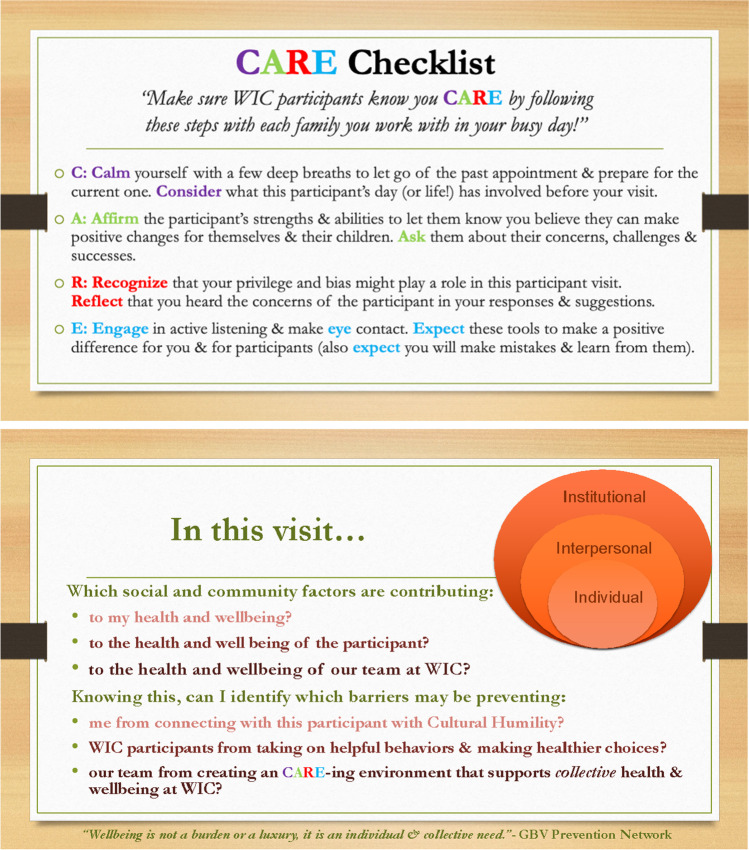

CARE Card Action Tool

We chose to conclude the training with the introduction of a novel action tool, the CARE Card (Fig. 2), intended to be visible at one’s desk at WIC as a reminder that this work is ongoing and lifelong. The double-sided, laminated card is designed to prompt WIC staff to be mindful and culturally humble in their interactions with participants and each other, rather than a linear checklist. The back of the card provides a visual of the individual, interpersonal, and institutional level framework we revisit throughout the session.

Fig. 1.

Workplace scenario: “A very busy day at WIC”

Fig. 2.

CARE card action tool

Assessment of the Program

To evaluate the antiracism training, we developed a series of 13 questions to assess WIC staff trainees’ knowledge of core concepts, awareness of their own identity, biases and privilege, and understanding of the role of racism in the US healthcare system. During implementation, we asked WIC staff trainees these questions at three timepoints (just before training, immediately after training, and 6 months post-training). We additionally created questions for trainees to rate their confidence to identify and address interactions that perpetuate racism at the individual, interpersonal, and institutional levels using a 5-point Likert Scale for responses, where 1 was “not at all,” 2 was “a little bit,” 3 was “somewhat,” 4 was “quite a bit,” and 5 was “extremely” confident. We framed our training and assessments in the context of the socio-ecological model for behavior change (at the individual, interpersonal, and institutional levels), as this model is often utilized by healthcare institutions and health service agencies to understand the many influences on health outcomes, and it is familiar to WIC staff. Right after the training, we additionally queried WIC staff trainees for feedback about each component and the training overall, assessing usefulness via a 5-point Likert scale for responses, where 1 was “not at all,” 2 was “a little bit,” 3 was “somewhat,” 4 was “quite a bit,” and 5 was “extremely” useful along with offering opportunities to give qualitative feedback. Surveys were available via a REDCap link to be completed by smartphone with paper copies available onsite for those who preferred that method. Responses were collected anonymously, managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools, and summarized as means/frequencies. We did not link individual trainee responses at each timepoint, limiting the examination of data to the cohort level only. Therefore, we used two-sided z-tests for independent proportions to compare responses before the training (baseline) to responses immediately after training, as well as responses at baseline to 6 months post-training. SAS version 9.4 [27] was utilized to carry out all analyses. While all WIC staff trainees (n = 42) completed the 3-h training session, we acknowledge there was attrition in the response rate for the posttest immediately after the training (n = 34), as well as in the number of responses we received at 6 months post-training (n = 32).

Results

We implemented the training in August 2019 on the required bimonthly education day for Philadelphia WIC nutrition professionals at agency headquarters. Our team provided lunch, administered a pre-assessment, and established community agreements (e.g., willingness to take risks, speak from one’s own experiences, etc.) before beginning didactics. Among 42 WIC staff trainees, the mean age was 30 years, 55% self-identified as white, 32% as Black or African American, 9% as Asian, 4% as other, 91% were female, and 74% had no prior antiracism training. Forty percent had worked at WIC for less than 1 year, 30% between 1 and 2 years, 12% between 3 and 5 years, 9% for 6–10 years, and 9% greater than 10 years. Eighty-six percent of staff trainees were WIC Nutrition Professionals (other remaining staff trainees were managers or administrators who worked at the WIC site where the training was conducted; they were not required to attend but chose to join the session). According to management at NORTH, Inc, there were approximately 44 Nutrition Professionals employed across all Philadelphia WIC offices at the time of the training. Thirty-six nutritional professionals attended the training, which is approximately 82% of the group required to attend.

Before the training, 48% of WIC staff trainees felt quite a bit or extremely aware of the role of racism in the US healthcare system; this increased to 91% immediately after and remained high at 6 months (75%) (p < 0.05 for changes from baseline to immediate posttest and from baseline to 6 months post-training using two-sided z-tests for independent proportions). At baseline, only 56% of trainees reported being quite a bit or extremely aware of their own biases and privilege. This increased to 91% immediately after the training and remained above baseline (81%) at the 6-month post-training assessment (p < 0.05 for changes from baseline to immediate posttest and from baseline to 6 months post-training using two-sided z-tests for independent proportions). While nutrition professionals reported increased confidence in identifying and addressing interactions that perpetuate racism at the individual, interpersonal, and institutional levels immediately after the training, their confidence in identifying and addressing interactions that perpetuate racism decreased at 6 months post-training at all levels (Table 1).

Table 1.

WIC nutrition professionals’ confidence in identifying and addressing interactions that perpetuate racism•

| Pre-training (n = 42) |

Immediately post-training (n = 34) |

Six months post-training (n = 32) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| % trainees that reported “quite a bit” or “extremely” confident | |||

| Confidence in IDENTIFYING interactions that perpetuate racism at the individual level | 49% | 74%* | 72%* |

| Confidence in ADDRESSING interactions that perpetuate racism at the individual level | 37% | 74%* | 45% |

| Confidence in IDENTIFYING interactions that perpetuate racism at the interpersonal level | 44% | 77%* | 61% |

| Confidence in ADDRESSING interactions that perpetuate racism at the interpersonal level | 22% | 64%* | 52%* |

| Confidence in IDENTIFYING interactions that perpetuate racism in work setting (e.g., at the institutional level) | 42% | 76%* | 65% |

| Confidence in ADDRESSING interactions that perpetuate racism in work setting (e.g., at the institutional level) | 29% | 73%* | 45% |

•For some responses, data were missing for one WIC staff trainee

*Changes from baseline to this time point were statistically significant (p < 0.05) using two-sided z-tests for independent proportions

Table 2 summarizes feedback immediately after the training about the usefulness of each program component as well as key qualitative feedback about each component. When queried about how their practice might change as a result of attending the workshop, WIC staff reflections included, “Learning to pause and think about my own implicit biases and try to be even more understanding of the participants situations,” and “I hope that I can have more mindful moments, where I'm taken back, or surprised by participants, who suffer and have such diverse experiences”. At 6 months post-training, one-third of WIC staff trainees felt quite a bit or extremely confident that the workshop content led to real changes in their interactions with WIC participants.

Table 2.

Evaluation of training components immediately post-training

| Training components | % trainees that reported “quite a bit” or “extremely” useful | Qualitative feedback |

|---|---|---|

| Identity web exercise | 88% |

“I thought it was very helpful and I was able to see things from a different perspective. I feel like I have more awareness now.”—Trainee 7 “I liked that I got to talk and explain an experience to a fellow coworker who is not from my background”—Trainee 3 “It made me think of things I was unaware of about my identity.”—Trainee 11 |

| Definitions and discussion of concepts | 90% |

“It (was) very helpful to define words and phrases that have a lot of political and racial tension around them. This invites clarity and understanding, rather than reactivity and division.”—Trainee 15 “Scholarly definitions help bring the words back from overly sensationalized click bait news articles. These words are thrown all over social media and the news so it’s great to remind ourselves what we are actually taking about.”—Trainee 22 |

| A very busy day at WIC scenario | 70% |

“We become immune to these situations rather than see each participant as an individual.”—Trainee 4 “This can be complicated because there are so many different people and angles to try and understand. Each of us suffer, and we act out when we don’t take care of ourselves.”—Trainee 21 |

| CARE card action tool | 90% |

“I find this to be a very helpful tool to find calm and to maintain self-care, as well as care for those different from you.”—Trainee 36 “Using the CARE card, (I’m) thinking about how the things participants go through affects our session.”—Trainee 40 |

Discussion

These findings suggest that a 3-h antiracism training grounded in cultural humility can change attitudes and awareness as well as confidence among WIC staff in identifying and addressing interactions that perpetuate individual, interpersonal, and systemic racism. WIC staff reported sustained increases in awareness of systemic racism and of their own biases and privilege for at least 6 months post didactics. Similar increases in confidence identifying and addressing interactions that perpetuate racism were achieved immediately after the training, although the magnitude decreased by 6 months. While WIC staff trainees’ reflections indicated they could see making changes to their practice as a result of the content presented, and one-third reported that the workshop led to changes in their interactions with WIC participants, we did not objectively assess whether changes in provider behaviors occurred (e.g., through observation) or query patients on their experiences.

Our results are aligned with those from a newly published paper, “Implementing a graduate medical education antiracism workshop at an academic university in the Southern USA” [28]. Similar to our training, content covered microaggressions, colorblindness, tokenism, stereotypes, levels of racism, the impact of racism on health, and antiracism concepts. A majority of participants who completed the post-training assessment reported they could apply knowledge to their work (95%) and found the workshop useful (95%). Over two-thirds reported being able to better identify disparities and better identify and communicate about racism. After the workshop, 75% thought differently about the healthcare impact of institutionalized racism. While Simpson and colleagues did not assess participants at 6 months post-training, many participants requested a longitudinal curriculum to build and sustain momentum around culture change. The consistent drop in WIC staff trainees’ confidence to identify and address interactions that perpetuate racism at 6 months post-training in our study further validates this need for disseminated practice in antiracism efforts.

Despite the fact that WIC staff trainees found the core training components in our study quite a bit or extremely useful, the workplace scenario and debrief elicited a wide range of responses and feelings among WIC staff trainees, including defensiveness. Trainees pointed out the competing priorities of accommodating challenges that participants face while still meeting agency expectations to follow protocols and rules, e.g., allowing participants who arrive late due to issues beyond their control such as public transportation challenges to still be seen on the same day versus following agency protocol to reschedule if more than 30 min late. This highlights how institutional level policies influence interactions between WIC participants and providers as well as among WIC staff [29], further demonstrated by the WIC enrollment process. Until the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the passage of waivers at the federal level to allow for remote enrollment and issuance of benefits [30], the bureaucratic and protocol driven nature of WIC meant there had not been institutional acknowledgement of how the life context that positions families in need of WIC benefits may work against them having the agency, time, and skills needed to physically produce what is required [31]. However, remote enrollment has been an antiracist institutional change that took WIC participants’ social context into account and reduced the opportunity for WIC staff implicit and explicit biases about the person applying for benefits. Therefore, it felt significant that WIC staff trainees recognized the need for an integrated approach linking individual, interpersonal, and institutional efforts toward equity, not solely placing the onus for change on individual staff members working on their biases or addressing interpersonal racism in the workplace.

In order to address confidentiality concerns, we did not link individual trainee responses at each timepoint, limiting the examination of data on changes in attitudes, awareness, and behaviors to the cohort level only (necessitating the use of z-tests for independent proportions in analyses). Therefore, we could stratify by neither demographic variables (e.g., race, time at WIC) nor the impact of higher baseline competencies in the areas covered to determine which trainee characteristics were associated with attrition or survey completion. Further, while our original intention was to do an annual core training with three quarterly follow-up sessions, due to Pennsylvania WIC transitioning to electronic benefit transfer cards in the fall of 2019 followed by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, plans for ongoing sessions were indefinitely suspended. This could explain why confidence in addressing interactions that perpetuate racism at multiple levels was not sustained at 6 months. Lastly, evidence reviewed earlier in this report describes antiracism training as most impactful in the context of larger institutional efforts to advance equity, which is not yet happening in a comprehensive manner at Philadelphia WIC.

Despite limitations, the initial findings from the training remain promising and indicate further work is needed to study if and how these demonstrated changes in WIC staff trainees’ attitudes, actions, and awareness translate into improved care experiences for WIC participants. As such, these findings can inform institutional-level changes at Philadelphia WIC, including implementing antiracism trainings for all staff at Philadelphia WIC (with possible statewide dissemination); creating a confidential means for WIC participants to give feedback about their experiences that can inform both the agency’s policies and antiracism work; and advocating as an agency for inclusion of WIC staff in legislation that mandates antiracism training for perinatal providers. In this seminal moment of attention to Black maternal mortality and systemic racism, we believe offering ongoing antiracism training is a valuable step toward building the capacity of WIC staff to improve the participant experience and advance a culture of health equity.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank NORTH, Inc., managers of the Philadelphia WIC program, for allowing us to offer the antiracism training as part of their professional development offerings.

Author Contribution

CS, MCF, GL, and MJ participated in the training design. CS and MCF implemented the training. CS and SH participated in the acquisition and analysis of data. CS, MCH, and SH participated in the drafting of the final manuscript. All authors participated in the critical review of the manuscript. All authors have given final approval to the manuscript.

Funding

Members of the study team were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01DK115939, R01HL130816).

Data Availability

Data is available upon request.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

This work was determined to be non-human subjects research by the Institutional Review Board at Temple University.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Villarosa L. 2018. Why America’s black mothers and babies are in a life-or-Death crisis: the answer to the disparity in death rates has everything to do with the lived experience of being a black woman in America. New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/magazine/black-mothers-babies-death-maternal-mortality.html. Accessed 15 Sept 2021.

- 2.Crear-Perry J (2018) Race isn’t a risk factor in maternal health. Racism is. Rewire News. https://rewire.news/article/2018/04/11/maternal-health-replace-race-with-racism/. Accessed 15 Sept 2021.

- 3.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. The Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardeman RR, Medina EM, Kozhimannil KB. Structural racism and supporting Black lives—the role of health professionals. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2113–2115. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1609535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine (2020) Strategies to overcome racism’s impact on pregnancy outcomes. Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. smfm.org/equity.

- 6.Scott, K. A., Britton, L., McLemore, M. R. (2019). The ethics of perinatal care for Black Women: dismantling the structural racism in “Mother Blame” narratives. Journal Perinatal Neonatal Nursing, 33(2), 108–115. 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000394 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Milner A, Franz B, Henry Braddock II J. We need to talk about racism—in all of its forms—to understand COVID-19 disparities. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):397–402. doi: 10.1089/heq.2020.0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United States Department of Agriculture (2018) WIC participant and program characteristics 2018—charts. USDA Food and Nutrition Services. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/participant-and-program-characteristics-2018-charts#1. Accessed 15 Sept 2021.

- 9.Gamblin M, Brooks C, Bassam N, Abu Khalaf NB (2019) Applying racial equity to U.S, federal nutrition assistance programs: SNAP, WIC and child nutrition. A Bread for the World Institute special report. Bread for the World Institute. https://www.paperturn-view.com/us/bread-for-the-world/applying-racial-equity-to-u-s-federal-nutrition-assistance-programs?pid=NTg58712&v=3. Accessed 15 Sept 2021.

- 10.March of Dimes (2017) PERISTATS Pennsylvania. Healthy moms. Strong babies. https://www.marchofdimes.org/Peristats/ViewSubtopic.aspx?reg=42&top=11&stop=448&lev=1&slev=4&obj=36. Accessed 15 Sept 2021.

- 11.Howell EA. Reducing disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;61(2):387–399. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muse S, Dawes Gay E, Doyinsola Aina A, et al. (2018) Setting the standard for holistic care of and for Black women. Black Mamas Matter Alliance.http://blackmamasmatter.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/BMMA_BlackPaper_April-2018.pdf. Accessed 15 Sept 2021.

- 13.National WIC Association (2021a) How we can build a more modern WIC experience. National WIC Association. https://www.nwica.org/blog/take-action-how-we-can-build-a-more-modern-wic-experience#.Yh0iHJPMJhE. Accessed 15 Sept 2021.

- 14.United States Department of Agriculture (2017) WIC 2017 eligibility and coverage rates. USDA Food and Nutrition Services. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic-2017-eligibility-and-coverage-rates. Accessed 15 Sept 2021.

- 15.Crawford, D. Crawford bias reduction theory and training (CBRT). Dr. Dana E. Crawford. http://drdanacrawford.com/home/cbrt/. Accessed 15 Sept 2021.

- 16.Masters, C., Robinson, D., Faulkner, S., Patterson, E., McIlraith, T., Ansari, A. (2019). Addressing biases in patient care with the 5Rs of cultural humility, a clinician coaching tool. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34(4), 627–63. 10.1007/s11606-018-4814-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.FitzGerald C, Martin A, Berner D, Hurst S. Interventions designed to reduce implicit prejudices and implicit stereotypes in real world contexts: a systematic review. BMC psychology. 2019;7(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s40359-019-0299-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalinoski ZT, Steele-Johnson D, Peyton EJ, Leas KA, Steinke J, Bowling NA. A meta-analytic evaluation of diversity training outcomes. J Organ Behav. 2013;34(8):1076–1104. doi: 10.1002/job.1839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green TL, Hagiwara N (2020) The problem with implicit bias training. Scientific American: Behavior & Society Opinion.https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-problem-with-implicit-bias-training/. Accessed 15 Sept 2021.

- 20.Hagiwara N, Kron FW, Scerbo MW, Watson GS. A call for grounding implicit bias training in clinical and translational frameworks. Lancet (London, England) 2020;395(10234):1457–1460. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30846-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hook JN, Davis DE, Owen J, Worthington Jr EL, Utsey SO (2013) Cultural humility: measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology®. 10.1037/a0032595. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Tervalon M, Murray-García J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9(2):117–125. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balakrishnan K, Arjmand EM. The impact of cognitive and implicit bias on patient safety and quality. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2019;52(1):35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2018.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504–1510. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Philadelphia School (2016) Tools for friendship. TPS Blog. https://www.tpschool.org/blog/2016/1/9/tools-for-friendship. Accessed 15 Sept 2021.

- 26.Center of Urban Pedagogy (2017) Show up: your guide to bystander intervention.https://www.ihollaback.org/app/uploads/2016/11/Show-Up_CUPxHollaback.pdf.

- 27.SAS Institute Inc (2013) SAS/ACCESS 9.4 Interface to ADABAS: Reference. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

- 28.Simpson T, Evans J, Goepfert A, Elopre L. Implementing a graduate medical education anti-racism workshop at an academic university in the Southern USA. Med Educ Online. 2022;27(1):1981803. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2021.1981803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nazroo JY, Bhui KS, Rhodes J. Where next for understanding race/ethnic inequalities in severe mental illness? Structural, interpersonal and institutional racism. Sociol Health Illn. 2020;42(2):262–276. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.13001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National WIC Association. (2021b) The state of WIC: healthier pregnancies, babies and young children during COVID-19. National WIC Association. https://s3.amazonaws.com/aws.upl/nwica.org/state-of-wic-report-march-2021.pdf. Accessed 15 Sept 2021.

- 31.Violante, A. &Yates-Berg, A. (n.d.). Could temporary, behaviorally informed changes to WIC be program fixtures? IDEAS 42 Blog. https://www.ideas42.org/blog/could-temporary-behaviorally-informed-changes-to-wic-be-program-fixtures/. Accessed 15 Sept 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.