Abstract

Background

Caregiver burden consists of disease specific and perceived stressors, respectively referred to as objective and subjective indicators of burden, and is associated with negative outcomes. Previous research has found that care partners to persons living with cognitive impairment and elevated levels of amyloid-β, as measured by a positron emission tomography (PET) scan, may experience caregiver burden.

Aims

To elucidate the relationship between amyloid scan results and subjective and objective indicators of burden.

Methods

A parallel mixed-methods design using survey data from 1338 care partners to persons with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia who received an amyloid scan from the CARE-IDEAS study; and semi-structured interviews with a subsample of 62 care partners. Logistic regression models were used to investigate objective factors associated with caregiver burden. A thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews was used to investigate subjective indicators by exploring care partners' perceptions of their role following an amyloid scan.

Results

Elevated amyloid was not associated with burden. However, the scan result influenced participants perceptions of their caregiving role and coping strategies. Care partners to persons with elevated amyloid expected increasing responsibility, whereas partners to persons without elevated amyloid and mild cognitive impairment did not anticipate changes to their role. Care partners to persons with elevated amyloid reported using knowledge gained from the scan to develop coping strategies. All care partners described needing practical and emotional support.

Conclusions

Amyloid scans can influence subjective indicators of burden and present the opportunity to identify and address care partners' support needs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40520-022-02314-6.

Keywords: Caregiver burden, Dementia, MCI, Amyloid scans, Disclosure

Introduction

Nine million Americans provide informal care to people living with dementia [1]. Compared to cognitively healthy older adults, people with dementia are more likely to need assistance with multiple self-care and medical tasks [2]. Care partners to people living with dementia are at increased risk of burden, which is associated with depression, anxiety and poorer physical health [3]. Existing models of caregiver burden, or caregiver stress, have outlined a complex relationship among multifactorial stressors. Levels of burden can be affected by primary stressors such as daily caregiving tasks and the care recipient's symptoms, referred to as objective indicators, or by how the care partner perceives the burden of care, referred to as subjective indicators [4]. Caregiver burden can further be moderated by coping strategies and social support.

Care partners play an important role in initiating the process of seeking a diagnosis for dementia [5]. In seeking a diagnosis, care partners expect to receive objective, personalized information and practical advice about the person living with cognitive impairment’s (PLwCI’s) condition [5]. Neuroimaging techniques, such as amyloid-β positron emission tomography (PET) scans, can detect the neuropathology associated with Alzheimer’s disease and increase diagnostic confidence [6]. The scan results are disclosed as a binary outcome, where a positive result indicates elevated levels of amyloid plaques, and a negative result indicates that levels of amyloid plaques are not elevated. In the US, coverage for amyloid scans is limited to those enrolled in a research study. Appropriate use criteria (which informed the inclusion criteria for this study) have recommended amyloid scans for those who are experiencing memory problems, with an uncertain etiology and where the scan is expected to influence the clinical management of the patient [7]. There is evidence that receiving a scan can alter the medical management of the patient [8]; however, its impact on patients and their care partners is less clear. More research is needed to understand how amyloid scan results can be used to better support PLwCI and their care partners before they can be made available in clinical practice.

Previous research has reported that care partners would like to learn the PLwCI’s amyloid status [9, 10]. However, it is not understood how scan results may shape care partners’ expectations of the disease process and experiences of caregiver burden. On the one hand, receiving amyloid scan results may help care partners to better understand the PLwCI’s condition and feel more confident in their future plans [11]. On the other hand, receiving an amyloid scan result may have a negative impact on care partners. A cross-sectional study of scan recipients in the US found that care partners to people diagnosed with dementia without elevated amyloid had significantly more caregiver burden than those with elevated amyloid [12]. However, this study reported baseline findings and the long-term relationship between scan results and caregiver burden has yet to be investigated. Furthermore, care partners to people with elevated amyloid have increased odds of reporting symptoms of anxiety compared to those with a negative scan [13, 14], and this was especially marked in care partners to people living with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). These findings are supported by a qualitative study reporting feelings of despair among care partners to PLwCI with elevated amyloid [15].

Care partners are at increased risk of burden, which is associated with poorer health outcomes. As care partners to persons with elevated amyloid may experience higher rates of caregiver burden, it is important to understand the relationship between caregiver burden and amyloid scans. It is unclear whether the symptoms of burden experienced by some care partners following an amyloid scan are a result of disease-specific factors (objective indicators), how they perceive their caregiving role in light of the scan result (subjective indicators), or a combination of both. Therefore, the aim of this study is to elucidate the relationship between amyloid scan and objective and subjective indicators of caregiver burden. The specific research questions were (1) Which factors are associated with caregiver burden 18 months after receiving a PET scan? and (2) How do caregivers perceive their caregiving role in light of the PLwCI’s scan result and diagnostic category? This knowledge could be used to inform clinical practice and develop interventions to better support care partners following an amyloid scan.

Methods

Mixed-methods design

This study uses an exploratory parallel mixed-methods design. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected and analyzed separately. Quantitative methods were used to address the first research question and investigate which factors put care partners at greater risk of burden as defined with objective indicators. Qualitative methods were used to address the second research question and examine the influence of the scan result on subjective indicators of burden by exploring the participants' interpretation of the scan and how this affected perceptions of their caregiving role. Findings from the quantitative and qualitative analyses were integrated during interpretation.

Data sources

Data for this study were derived from the Caregivers Reactions and Experience (CARE) supplemental study of the Imaging Dementia Evidence for Amyloid Scanning Study (IDEAS), a cohort study examining the impact of amyloid-β PET scans on clinical outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries with MCI or dementia. The CARE-IDEAS study expands on the IDEAS study by quantitatively and qualitatively investigating the perspectives of patients and care partners who have received an amyloid scan. The CARE-IDEAS study comprises a subsample of 2228 patients and 1872 care partners from 415 dementia care practices across 40 states who participated in the IDEAS study; the method of recruitment and inclusion and exclusion criteria have previously been reported [16]. The CARE-IDEAS study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Brown University (#1606001534).

Quantitative analysis

Data collection procedures and measures

Quantitative data were collected at two time points through a structured telephone survey questionnaire. Time point 1 was completed on average 4.5 months after the scan (between 2017 and 2018) and the time point 2 was completed approximately 18 months later (between 2018 and 2019). Care partners who had completed the questionnaire at both time points were included in this analysis (N = 1338). Sociodemographic information for care partners was obtained at time point 1. PLwCI’s diagnostic category at enrollment (MCI vs dementia) and scan result (elevated vs non-elevated levels of amyloid) were taken from the IDEAS study.

We used a four-item screening version of the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) to measure caregiver burden at time point 2. Scores range between 0 to 16, where a higher score indicates greater burden. Participants scoring in the 75th percentile, a score of 7 or above (range = 0–16), were classified as experiencing high caregiver burden. The screening version of the ZBI was found to be reliable among community dwelling care partners to PLwCI for detecting caregiver burden in longitudinal studies [17].

Care partners rated the number of hours per week they spent caring for the PLwCI due to memory problems on a categorical scale (< 5, 5–19, 20–39, and 40 +) at both time points. We cross-tabulated the responses from care partners at both time points to determine whether there had been a change in the number of hours they spent caregiving, this was categorized as “fewer,” “the same” and “more”.

We used two items (help with dressing and help with keeping track of medications) from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) to measure the degree to which memory problems affected the PLwCI’s daily activities in the last month. This measure was completed by care partners at time point 2.

Statistical analysis

First, participant characteristics were summarized, stratified by diagnostic category and level of impairment. Chi-squared tests were used to check for significant differences between the groups. Second, unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models were estimated to determine which variables were associated with high caregiver burden at follow-up. All analyses were completed using the gtsummary package in RStudio [18].

Quantitative sample

Table 1 presents participant characteristics in the quantitative sample retained at time point 2. Most participants were caring for someone with MCI (72.4%) and over half were caring for someone with elevated amyloid (64.6%). The majority of care partners were younger than 75 (60.0%), female (67.6%), non-Hispanic White (93.8%), had a Bachelor’s or graduate degree (28.7 and 32.1%, respectively) and were caring for their spouse (89.3%). Half (50.7%) spent 5 hours or fewer per week caring for the PLwCI at follow-up, with 13.4% reporting the PLwCI required help with dressing and 44.9% required help with medications due to memory problems.

Table 1.

Quantitative sample characteristics by diagnostic category and level of amyloid

| All participants | Dementia (N = 369) | MCI (N = 969) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1338 | Not Elevated, N = 96 | Elevated, N = 273 | p1 | Not Elevated, N = 377 | Elevated, N = 592 | p1 | |

| Care partner Characteristics | |||||||

| Age, n (%) | 0.43 | 0.35 | |||||

| < 65 | 209 (15.7) | 15 (15.8) | 40 (14.9) | 64 (17.0) | 90 (15.3) | ||

| 65–74 | 589 (44.3) | 49 (51.6) | 116 (43.1) | 175 (46.4) | 249 (42.3) | ||

| 75 + | 532 (40.0) | 31 (32.6) | 113 (42.0) | 138 (36.6) | 250 (42.4) | ||

| Gender, n (%) | 0.96 | 0.33 | |||||

| Male | 433 (32.4) | 34 (35.4) | 96 (35.2) | 111 (29.4) | 192 (32.4) | ||

| Female | 905 (67.6) | 62 (64.6) | 177 (64.8) | 266 (70.6) | 400 (67.6) | ||

| Non-Hispanic, White, n (%) | 1251 (93.8) | 87 (90.6) | 254 (93.4) | 0.13 | 349 (93.3) | 561 (94.9) | 0.16 |

| Level of Education, n (%) | 0.52 | 0.033 | |||||

| High school or less | 160 (12.0) | 11 (11.5) | 38 (14.0) | 38 (10.1) | 73 (12.4) | ||

| Vocational/Some college | 361 (27.2) | 32 (33.3) | 70 (25.8) | 117 (31.2) | 142 (24.2) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 381 (28.7) | 31 (32.3) | 90 (33.2) | 87 (23.2) | 173 (29.5) | ||

| Graduate degree | 427 (32.1) | 22 (22.9) | 73 (26.9) | 133 (35.5) | 199 (33.9) | ||

| Relationship to PLwCI, n (%) | 0.66 | 0.54 | |||||

| Spouse | 1,194 (89.3) | 85 (88.5) | 246 (90.1) | 339 (89.9) | 524 (88.7) | ||

| Other | 143 (10.7) | 11 (11.5) | 27 (9.9) | 38 (10.1) | 67 (11.3) | ||

| Caregiver Burden, n (%) | 0.031 | 0.33 | |||||

| Low | 927 (70.5) | 69 (74.2) | 165 (61.8) | 276 (74.4) | 417 (71.5) | ||

| High | 387 (29.5) | 24 (25.8) | 102 (38.2) | 95 (25.6) | 166 (28.5) | ||

| Hours Spent Caregiving (per week), n (%) | 0.61 | 0.013 | |||||

| < 5 | 667 (50.7) | 29 (30.9) | 85 (31.5) | 235 (63.3) | 318 (54.7) | ||

| 6–19 | 354 (26.9) | 34 (36.2) | 84 (31.1) | 71 (19.1) | 165 (28.4) | ||

| 20–39 | 145 (11.0) | 16 (17.0) | 42 (15.6) | 34 (9.2) | 53 (9.1) | ||

| 40 + | 150 (11.4) | 15 (16.0) | 59 (21.9) | 31 (8.4) | 45 (7.7) | ||

| Change in hours spent caregiving per week, n (%) | 0.45 | 0.46 | |||||

| Fewer | 84 (12.0) | 10 (20.0) | 23 (14.7) | 20 (10.2) | 31 (10.4) | ||

| The same | 431 (61.4) | 27 (54.0) | 79 (50.6) | 135 (68.5) | 190 (63.5) | ||

| More | 187 (26.6) | 13 (26.0) | 54 (34.6) | 42 (21.3) | 78 (26.1) | ||

| PLwCI needs help with medication, n (%) | 581 (44.9) | 61 (65.6) | 190 (73.4) | 0.16 | 95 (26.1) | 235 (40.7) | < 0.001 |

| PLwCI needs help with dressing, n (%) | 178 (13.4) | 27 (28.7) | 72 (26.6) | 0.69 | 23 (6.1) | 56 (9.6) | 0.060 |

| PLwCI Characteristics | |||||||

| Age, n (%) | 0.97 | 0.17 | |||||

| 65–74 | 443 (43.3) | 27 (40.3) | 71 (41.8) | 152 (47.8) | 193 (41.2) | ||

| 75 + | 581 (53.7) | 40 (59.7) | 99 (58.2) | 166 (52.2) | 276 (58.8) | ||

MCI mild cognitive impairment, PLwCI persons living with cognitive impairment

1Pearson’s Chi-squared test; Fisher’s exact test

Among care partners for people living with dementia, a greater proportion of those caring for a patient with elevated amyloid reported high caregiver burden (38.2%) compared to those caring for people without elevated amyloid (25.8%). Among participants caring for someone with MCI, the number of hours participants spent providing care varied significantly by the amyloid scan result; 63.5% of participants caring for a person with MCI and elevated amyloid spent 5 h or fewer per week providing care, compared to 54.7% without elevated amyloid. Furthermore, significantly more care partners to people with MCI and elevated amyloid (40.7 vs. 26.1%) reported the person they care for needed help with keeping track of medications due to memory problems.

Quantitative results

Factors associated with caregiver burden

Logistic regression models were used to explore which variables were associated with higher odds of caregiver burden (Table 2). Unadjusted logistic regression models show that being younger, female (OR = 2.26, CI = 1.72–3.01) and spending more hours caregiving per week was associated with increased odds of caregiver burden. Additionally, providing care to a PLwCI with an elevated scan result (OR = 1.34, CI = 1.04–1.72), a diagnosis of dementia (OR = 1.43, CI = 1.10–1.85) or who needs help with keeping track of medications (OR = 2.67, CI = 2.09–3.43) or dressing (OR = 3.37, CI = 2.42–4.71) was associated with an increased odds of burden.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models showing factors associated with high caregiver burden

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI)1 | p | OR (95% CI)1 | p |

| Care partner age | ||||

| < 65 | – | – | ||

| 65–74 | 0.69 (0.50–0.97) | 0.029 | 0.77 (0.48–1.25) | 0.29 |

| 75–84 | 0.59 (0.42–0.84) | 0.003 | 0.66 (0.40–1.08) | 0.10 |

| 85 + | 0.27 (0.11–0.56) | 0.001 | 0.25 (0.09–0.66) | 0.008 |

| Care partner gender | ||||

| Male | – | – | ||

| Female | 2.26 (1.72–3.01) | < 0.001 | 2.39 (1.74–3.32) | < 0.001 |

| Care partner race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic, White | – | – | ||

| Hispanic, White | 1.21 (0.49–2.77) | 0.67 | 1.02 (0.36–2.75) | 0.97 |

| Non-Hispanic, Black or African American | 1.61 (0.63–3.93) | 0.30 | 1.31 (0.36–4.21) | 0.66 |

| Other | 0.93 (0.42–1.89) | 0.85 | 0.99 (0.39–2.40) | 0.99 |

| Relationship to PLwCI | ||||

| Spouse | – | – | ||

| Other | 1.25 (0.86–1.81) | 0.24 | 0.96 (0.55–1.66) | 0.88 |

| Level of education | ||||

| High school or less | – | – | ||

| Vocational/some college | 1.13 (0.74–1.75) | 0.59 | 0.96 (0.58–1.58) | 0.86 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1.46 (0.96–2.24) | 0.079 | 1.36 (0.84–2.23) | 0.21 |

| Graduate degree | 1.31 (0.87–2.01) | 0.20 | 1.30 (0.81–2.12) | 0.29 |

| Hours spent caregiving (per week) | ||||

| < 5 | – | – | ||

| 6–19 | 4.65 (3.40–6.40) | < 0.001 | 4.92 (3.46–7.06) | < 0.001 |

| 20–39 | 7.96 (5.34–11.9) | < 0.001 | 7.23 (4.59–11.5) | < 0.001 |

| 40 + | 10.1 (6.78–15.3) | < 0.001 | 9.25 (5.76–15.0) | < 0.001 |

| PLwCI needs help with medication | ||||

| No | – | – | ||

| Yes | 2.67 (2.09–3.43) | < 0.001 | 1.13 (0.81–1.57) | 0.47 |

| PLwCI needs help with dressing | ||||

| No | – | – | ||

| Yes | 3.37 (2.42–4.71) | < 0.001 | 1.59 (1.06–2.40) | 0.027 |

| PLwCI scan result | ||||

| Not Elevated | – | – | ||

| Elevated | 1.34 (1.04–1.72) | 0.026 | 1.15 (0.85–1.55) | 0.36 |

| Diagnostic category | ||||

| MCI | – | – | ||

| Dementia | 1.43 (1.10–1.85) | 0.007 | 0.78 (0.56–1.08) | 0.14 |

MCI mild cognitive impairment, PLwCI persons living with cognitive impairment

1OR Odds ratio, CI Confidence interval

When adjusting for all other variables, the effect of age as a protective factor against caregiver burden was attenuated but only significant for the 85 + group (OR = 0.25, CI = 0.09–0.66). Women still had much higher odds of burden compared to men (OR = 2.39, CI = 1.74–3.32). Spending more hours a week caregiving and providing care to a PLwCI who needs help dressing remained associated with increased odds of burden (OR = 1.59, CI = 1.06–2.40). In the adjusted models the diagnostic category (OR = 1.15, CI = 0.85–1.55) and scan result (OR = 0.78, CI = 0.56–1.08) were no longer significantly associated with caregiver burden.

Qualitative analysis

Data collection procedures

A subset of care partners who completed both survey time points and consented to be contacted for future research opportunities were invited to participate in an additional in-depth telephone interview. Care partners were eligible to participate if they scored 21 or above on the Modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status [19]; this cut-off was recommended by an expert in cognitive assessment. To increase diversity of experiences and perspectives in the qualitative sample, we over-sampled participants who did not identify as non-Hispanic White. Potential participants were mailed a consent form prior to being contacted by the research team for an interview.

Qualitative data were collected through semi-structured interviews. The interviews were conducted with 62 care partners via telephone between May 2020 and January 2021 by two research assistants and one research coordinator, under the supervision of senior researchers. Before starting the interviews, the consent form was reviewed with the participant and they were asked to explain the purpose of the study in their own words as an additional check of capacity. The interviews followed a topic guide which started with questions about the decision to get the scan followed by questions about what the scan meant for both the care partner and the PLwCI, how they felt about the results, and what the scan results meant for the PLwCI’s future care (see Supplementary File 1).

Thematic analysis

The interviews were recorded, with permission, and transcribed verbatim. Initially, the data were organized using exploratory content analysis. Codes determined to be relevant to this research question were selected for the thematic analysis presented in this paper. We followed the six steps of reflexive thematic analysis as outlined by Braun and Clarke [20]. All members of the research team familiarized themselves with the data and made an initial list of codes. The team met to share their codes, and discuss the different interpretations of the data. During this meeting the codes were compiled into a list of categories (see Supplementary File 2). The first author applied the categories developed by the team to the data in NVivo. We used the queries function to stratify the qualitative data by scan result and diagnostic category at the time of the scan to explore the subjective indicators of burden. The first author then developed themes, along with a thematic diagram, which was reviewed by the rest of the team.

Qualitative results

Qualitative sample

Most participants in the qualitative sample were under the age of 75 (72.6%), female (75.8%), non-Hispanic White (54.8%) and spent 20 hours per week providing care (74.2%), see Table 3. One third reported high caregiver burden (29.5). 35.5% reported the PLwCI needed help keeping track of medications due to memory problems. The majority of participants were caring for a person with elevated amyloid (58.1%) and/or MCI (79.0%).

Table 3.

Characteristics of qualitative sample

| Characteristic | N = 62 |

|---|---|

| Care partner age, n (%) | |

| < 65 | 13 (21.0) |

| 65–74 | 32 (51.6) |

| 75 + | 17 (27.4) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 15 (24.2) |

| Female | 47 (75.8) |

| Non-Hispanic, White, n (%) | 34 (54.8) |

| Caregiver burden, n (%) | |

| Low | 43 (70.5) |

| High | 18 (29.5) |

| Hours spent caregiving (per week), n (%) | |

| < 20 | 46 (74.2) |

| 20 + | 16 (25.8) |

| PLwCI needs help with medication, n (%) | 22 (35.5) |

| Scan result, n (%) | |

| Elevated | 36 (58.1) |

| Not Elevated | 26 (41.9) |

| Diagnostic category, n (%) | |

| MCI | 49 (79.0) |

| Dementia | 13 (21.0) |

MCI mild cognitive impairment, PLwCI persons living with cognitive impairment

Results

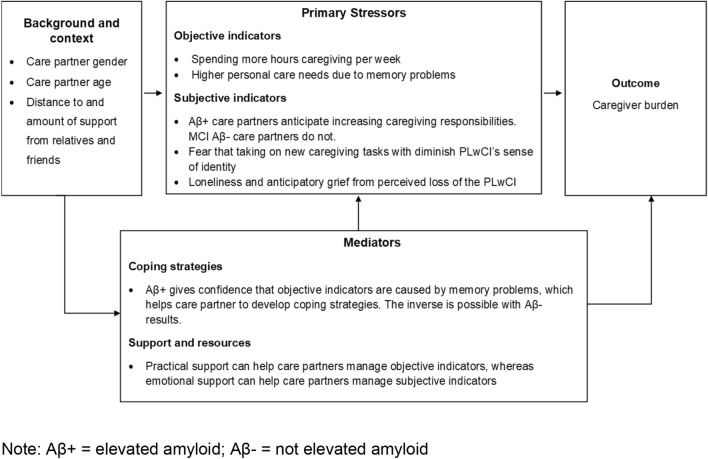

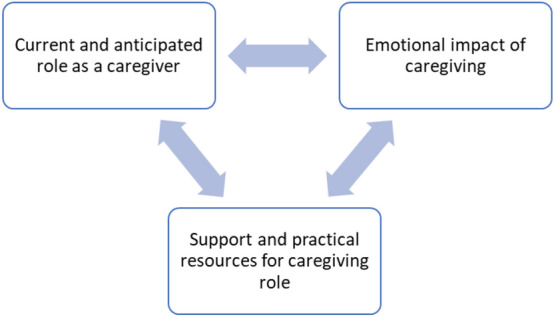

We identified three themes: (1) current and anticipated role as a care partner, (2) emotional impact of caregiving and (3) support and practical resources (Fig. 1). The scan result influenced care partners perceptions of their caregiving role and the emotional impact of caregiving. All participants described a need for support and practical resources to help them manage their current and future caregiving role and its emotional impact.

Fig. 1.

Thematic diagram of qualitative results

Current and anticipated role as a care partner

Most care partners described taking on caregiving tasks as a result of the PLwCI’s symptoms. Many, especially those caring for someone with elevated amyloid, expressed an expectation that this would gradually increase until formal care would be needed. However, some care partners to people with MCI without elevated amyloid reported they did not expect the PLwCI’s cognitive impairment to decline and therefore their caregiving role would not change.

Participants detailed gradually taking on more responsibility, including managing the PLwCI’s medications, medical appointments, finances and household chores as a result of the PLwCI’s memory problems. When taking on new tasks or roles, some participants noted concerns about the impact this change may have on the PLwCI’s sense of autonomy and identity.

“I’m a medical person, and he was the finance person. I allowed him to do everything in those early years. Like I said, we’ve been married 39 years, and I honestly did not take an active interest. Now, I find that when I really need to, he is extremely reluctant to give any of that up. Like, as I said, what he does with finances, that’s what defines him.” (MCI without elevated amyloid)

Participants acknowledged an awareness that the PLwCI’s care needs could increase to the point where they would no longer be able to manage their care alone. Some participants described increasing informal care arrangements by moving closer to family members, for example. Whereas others reported considering home care, nursing homes or assisted living. In general, participants expressed a preference to delay introducing formal care for as long as possible.

“I would like to have someone to help around here, but at the same time, I just rather do it myself. I don’t know how to explain. I think if [it] just gets really worse in the future, yeah, I will like somebody to help. Right now, I think I can handle it with the help of my kids.” (Dementia with elevated amyloid)

Conversely, some participants who were caring for a person with MCI without elevated amyloid did not describe a future where increasing care would be needed, and reported returning to their normal routines. “Well, hopefully we won’t need that, with the negative test results from that. We were hoping that you won't need any of that. If it had been positive, we would have already started making alternative, alternative plans.” (MCI without elevated amyloid).

Emotional impact of role

Participants outlined the emotional impact of their caregiving role. Participants who were caring for someone with elevated amyloid detailed using the knowledge derived from the scan to develop coping strategies. Whereas a participant caring for some with MCI without elevated amyloid said they struggled to cope with cognitive decline which could not be attributed to Alzheimer’s disease.

Participants noted that witnessing the progression of memory problems was upsetting. Spouses, in particular, expressed feeling sad and anticipatory grief from watching the cognitive and functional decline of the PLwCI. Many care partners were living alone with the PLwCI with minimal support, and noted that being the sole witness to changes in the PLwCI was an isolating experience.

“It's very eye opening, especially when you live with someone to watch their daily movements. People who do not live with their loved ones or people who just visit, don’t understand exactly what happens to people like that and that as the brain deteriorates, you could see changes.” (MCI with elevated amyloid)

Managing the everyday symptoms associated with dementia or MCI could be emotionally challenging. Participants noted that receiving a scan result indicating elevated amyloid helped to reinforce the knowledge that the symptoms they observed were likely to be caused by Alzheimer’s disease. This, in turn, helped them to develop coping strategies.

“I know that my role is going to change because I have to be even more patient and more supportive when he can’t find something that’s right in front of his face. So I just know that I just have to be more patient, and then him being anxious about it makes it more difficult for him.” (MCI with elevated amyloid)

“When that hits me and I’m just kind of freaking out, I go and open the picture of the PET scan on my desktop and say, ‘Oh yeah,’ and it helps me remind myself of what we’re dealing with. It's not him. It's the Alzheimer’s. I have this mantra, ‘It's not him. It’s the Alzheimer’s,’ and the PET scan helps me remember that. So I guess that's kind of, for me, it’s just a reminder that this is a real thing, not just he’s not just being weird.” (MCI with elevated amyloid)

However, a participant caring for a person without elevated amyloid, was increasingly frustrated by memory problems which could not be attributed to dementia: “At times, it’s very frustrating because of the memory loss. I keep hearing, he doesn't have Alzheimer’s. He doesn’t have dementia. It’s ADHD. That’s something not as serious. It’s something that we just have to deal with day-by-day.” (MCI without elevated amyloid).

Support and practical resources

Participants said they needed both practical and emotional support to manage their caregiving role and its emotional impact irrespective of scan result. Many care partners described family and friends as a source of both practical and emotional support. Some care partners in this study said they moved closer to family, or family members moved in to share caregiving tasks. Without such support, care partners could feel even more burdened by their role: “I think the biggest problem for me at this point is the fact that there’s really nobody else for me to share this. It’s a responsibility on me. I’m going to use the word ‘burden’ on me.” (Dementia without elevated amyloid). Furthermore, some participants said they felt uncomfortable with sharing their difficulties with family members: “It’s not fair to them for me to unload daily, with everything that’s going wrong. It is, in my opinion, important for me to keep them in the loop enough but I don’t call them every single time he does something screwy.” (MCI without elevated amyloid). Participants also listed specialist dementia services, rather than family members, as a source of support.

Participants reported attending classes run by specialist services and talking to health and social care professionals could help them to understand what to expect in the future, make plans and set realistic expectations for their anticipated caregiving role.

“What’s helped me a lot, again, is the support group that we go to where the social worker there is the one that has advised us what to do along the path of this illness or disease, whatever they want to call it. But she’s been very informative, telling us what steps we should take next.” (Dementia without elevated amyloid)

Attending caregiver meetings was also described as a valuable opportunity to meet others in similar situations: “[care partners should] go to the caregiver meetings. Sometimes that’s your only outlet to be able to talk to people.” (Dementia with elevated amyloid).

Integration of quantitative and qualitative findings.

To elucidate the relationship between amyloid scan and the objective and subjective indicators of burden, we grounded the integration of the quantitative results in the caregiver stress model (Fig. 2). Both the quantitative and qualitative results indicate the caregiver’s background and context can affect caregiver burden. The quantitative results show women have a greater risk of burden and care partners over the age of 85 have a reduced risk of burden. Furthermore, the qualitative results show distance to and degree of support from family members and friends can help care partners manage their caregiving role.

Fig. 2.

Integration of results and the caregiver stress model

Primary stressors contributing to caregiver burden can be broken down into objective and subjective indicators. The quantitative results show caring for someone with elevated amyloid was not associated with increased burden. Instead, the objective indicators of burden were spending more hours caregiving per week and providing care to someone who needs help with personal care tasks due to memory problems. The qualitative results indicate that amyloid scan results affected subjective indicators, including how care partners perceive their caregiving role. More specifically, care partners to people with elevated amyloid scans results describe a future of increasing care responsibilities, whereas partners to people with MCI without elevated amyloid did not describe anticipating such a future. Other subjective indicators of burden that did not vary by scan result were a concern that taking on new caregiving responsibilities would diminish the PLwCI’s sense of identity and anticipatory grief from the perceived loss of the PLwCI.

Coping strategies, support and resources can affect the degree to which care partners experience burden. The findings from the qualitative study demonstrated that the knowledge derived from an elevated amyloid scan result could help participants to understand the PLwCI better and develop coping strategies. However, there was also some evidence that care partners to someone with MCI without elevated amyloid could experience an inverse of this effect. All participants had a need for practical and emotional support to manage the objective and subjective indicators of burden.

Discussion

Previous research has found that care partners value the opportunity to learn the PLwCI’s amyloid status [10, 15]. In this study, we found elevated amyloid was not associated with caregiver burden when controlling for other factors. We found the number of hours spent caregiving and the degree of care required by the care recipient were associated with higher odds of burden. However, the scan result affected how care partners perceived their caregiving role and their coping strategies. These findings indicate elevated amyloid is not associated with objectively measured burden. This is perhaps unsurprising as objective indicators of burden encompass disease-specific determinants, such as severity and rate of decline, and amyloid scans are not recommended for determining the severity of the disease or prognosis [7].

The findings of this study show that the scan result can influence the care partner’s subjective experience of their caregiving role and their coping strategies. Previous research shows that the desire to find out if the PLwCI’s symptoms were caused by Alzheimer’s disease was a key motivator for patients and their care partners to undergo an amyloid scan [15] and that care partners report better understanding of the PLwCI after receiving an amyloid scan [11, 15]. The findings from our study suggest a more nuanced experience based on the level of impairment at the time of diagnosis and scan result. Firstly, participants with scans indicating elevated amyloid expressed confidence that the PLwCI’s memory problems were caused by Alzheimer’s disease. Therefore, they described anticipating a future where the PLwCI would require an increasing amount of care. Furthermore, a scan result for elevated amyloid could provide comfort to care partners by clarifying the diagnosis and help them to develop coping strategies. Conversely, a care partner to a person with MCI reported the care recipient did not have Alzheimer’s disease and did not anticipate increasing care needs in the future. However, those with a negative scan and MCI may still experience symptoms of memory loss, and their care partners may struggle with managing symptoms which could not be explained by a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. While elevated amyloid increases the risk of converting from MCI to dementia, this relationship is not definitive [7]. As the scan result influences the care partner’s expectations of their role and how they cope with it, it is important they correctly interpret the meaning of the scan results. This is supported by research by our group, which found care partners to people with MCI had difficulty accurately reporting their scan results [21]. Still, it is not clear if this is due to the nuanced implications of the scan result or if this is due to how the results are communicated to patients and their care partners [9]. Furthermore, it is not clear how the diagnosis of alternative conditions to explain the PLwCI’s memory problem affects the care partner’s understanding of the scan result. Future research should examine how amyloid scan results are disclosed to care partners, including cases where PLwCI receive alternative diagnoses to explain their cognitive impairment, and how this affects their understanding of the scan result.

All participants in the qualitative analysis reported a need for emotional support and practical resources for managing their caregiving role, irrespective of the scan result or diagnostic category. This is supported by a survey of care partners in the US, where participants rated information on how to keep the care recipient safe at home and how to cope emotionally as their top two priorities [22]. Previous research has shown that care partners to persons with MCI and dementia have similar needs for support but differ in their specific support needs [23]. MCI care partners needed support with managing neuropsychiatric symptoms and dementia care partners needed support managing functional disability. Therefore, interventions to support care partners should be tailored depending on the diagnostic category of the patient.

Strengths and limitations

This study used a mixed-methods design to explore the relationship between caregiver burden and amyloid scan result. The use of both quantitative and qualitative data allowed us to examine the role of objective and subjective indicators and present a nuanced understanding of caregiver burden. The findings of this study should be considered in light of a few limitations. Firstly, when stratifying analyses by scan result and level of impairment, some cells contained a small number of participants, limiting the power to detect differences between groups. Furthermore, our quantitative sample was constrained by a lack of diversity in terms of race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status, although we did oversample diverse participants for the in-depth qualitative interviews. Similarly, we used a screening version of the ZBI, which may lack the sensitivity of longer versions. We detected similar levels of burden to Robinson and colleagues [12], who used the full version of this measure, however these similarities may be due to the distributional cut-off used to define high caregiver burden. More research is needed on this topic with a greater range of objective indicators of burden including the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Finally, qualitative interviews were completed a few years after the results of the amyloid scan and during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have influenced how care partners perceived their caregiving role and willingness to introduce formal care.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings of this study indicate that amyloid scan results influence subjective indicators of burden, rather than the objective indicators. As the scan result affects the care partner’s subjective understanding of their current and future caregiving role, it is important they are correctly interpreting the meaning of the scan. This is an important area for future work. Participants reported a need for emotional and practical support, which should inform care and interventions. The disclosure of amyloid status is an opportunity for clinicians to identify and address the support needs of care partners.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

EC and EB: initially designed the aims and analyses reported in this manuscript, all authors gave critical feedback on the research aims and qualitative and quantitative analyses. EC: conducted the quantitative analysis. All authors contributed to the qualitative analysis. EC: integrated the results and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the revising of the manuscript and approved the final draft.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG053934 and by the American College of Radiology Imaging Network and the Alzheimer's Association. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the American College of Radiology Imaging, or the Alzheimer's Association. EC was supported by an AHRQ National Research Service Award T32 (Grant 5T32 HS000011-37). ND was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers K01AG070284 and P30AG028716 (Dr. Schmader).

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available in the Brown Digital Repository (https://doi.org/10.26300/dqt0-vq57) which includes a CARE-IDEAS codebook, and a PDF file with a description of the software used and syntax used for data cleaning and the final analytical models.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association (2022) 2022 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 18:700–789. 10.1002/alz.12638 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman BC, Wolff JL. The disproportionate impact of dementia on family and unpaid caregiving to older adults. Health Aff. 2015;34:1642–1649. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2003;18:250–267. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30:583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karnieli-Miller O, Werner P, Aharon-Peretz J, et al. Expectations, experiences, and tensions in the memory clinic: the process of diagnosis disclosure of dementia within a triad. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:1756–1770. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212000841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schipke CG, Peters O, Heuser I, et al. Impact of beta-amyloid-specific florbetaben PET imaging on confidence in early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2012;33:416–422. doi: 10.1159/000339367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson KA, Minoshima S, Bohnen NI, et al. Appropriate use criteria for amyloid PET: a report of the amyloid imaging task force, the society of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging, and the alzheimer’s association. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:E1–E16. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.G Rabinovici, C Gatsonis, C Apgar, et al (2019) Amyloid PET Leads to Frequent Changes in Management of Cognitively Impaired Patients: the Imaging Dementia—Evidence for Amyloid Scanning (IDEAS) Study (Plen01.001). Neurology 92.

- 9.Largent EA, Abera M, Harkins K, et al. Family members perspectives on learning cognitively unimpaired older adult’s amyloid-β PET scan results. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:3203–3211. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mustafa R, Brosch JR, Rabinovici GD, et al. Patient and caregiver assessment of the benefits from the clinical use of amyloid PET imaging. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2018;32:35–42. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bensaïdane MR, Beauregard J-M, Poulin S, et al. Clinical utility of amyloid PET imaging in the differential diagnosis of atypical dementias and its impact on caregivers. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52:1251–1262. doi: 10.3233/JAD-151180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson RL, Rentz DM, Bruemmer V, et al. Observation of patient and caregiver burden associated with early Alzheimer’s disease in the United States: design and baseline findings of the GERAS-US cohort Study 1. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;72:279–292. doi: 10.3233/JAD-190430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bélanger E, D’Silva J, Carroll MS, et al. Reactions to amyloid PET scan results and levels of anxious and depressive symptoms: CARE IDEAS study. Gerontologist. 2022 doi: 10.1093/geront/gnac051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lingler JH, Sereika SM, Butters MA, et al. A randomized controlled trial of amyloid positron emission tomography results disclosure in mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16:1330–1337. doi: 10.1002/alz.12129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grill JD, Cox CG, Kremen S, et al. Patient and caregiver reactions to clinical amyloid imaging. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:924–932. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jutkowitz E, Van Houtven CH, Plassman BL, Mor V. Willingness to undergo a risky treatment to improve cognition among persons with cognitive impairment who received an amyloid PET scan. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2020;34:1–9. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, et al. The Zarit Burden Interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist. 2001;41:652–657. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sjoberg D, Whiting K, Curry M, et al. Reproducible summary tables with the gtsummary package. R J. 2021;13:570. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2021-053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welsh KA, Breitner JC, Magruder-Habib KM. Detection of dementia in the elderly using telephone screening of cognitive status. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1993;6:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.James HJ, Van Houtven CH, Lippmann S, et al. How accurately do patients and their care partners report results of amyloid-β PET scans for alzheimer’s disease assessment? J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;74:625–636. doi: 10.3233/JAD-190922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.AARP and National Alliance for Caregiving . Caregiving in the United States 2020. Washington, DC: AARP; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan KA, Weldon A, Huby NM, et al. Caregiver support service needs for patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24:171–176. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181aba90d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available in the Brown Digital Repository (https://doi.org/10.26300/dqt0-vq57) which includes a CARE-IDEAS codebook, and a PDF file with a description of the software used and syntax used for data cleaning and the final analytical models.