Abstract

An estimated 3 million people died due to the Bengal famine of 1943. The purpose of this article is to theorize the Bengal famine through the lens of colonial biopolitics. The colonial strategies and utilitarian principles by the British authorities exacerbated the Bengal famine. Utilizing Foucault’s concept of biopolitics, I point out how the British viewed Indian bodies discursively. To reaffirm their sense of superiority, they reduced their Indian subjects to animal-like beings’ incapable of controlling their own reproduction. In order to fulfil British goals, Indian people were forced to participate in the war effort. This paper situates the local and global politics of the famine as they were wrapped up in the geopolitics of World War II, during which the British colonial authorities were far more concerned about a Japanese invasion of South Asia than they were with the lives of people dying of hunger. The article highlights how the implementation of racist policies worsened the famine since it was a product of wartime priorities and calculations. I argue that the Bengal famine of 1943 is a historic tragedy of the colonial past, which was transformed into a socially constructed catastrophe by the British colonizers.Geographers have never studied the Bengal famine of 1943, and one of the principal purposes of this paper is to fill this void.

Keywords: Colonial biopolitics, Famine, Bengal famine of 1943, Governmentality, Colonial authorities, War

Introduction

I hate Indians. They are a beastly people with a beastly religion. The famine was their own fault for breeding like rabbits.

–Winston Churchill (quoted in Choudhury,; 2021, p. 1; Portillo, 2007; Tharoor, 2010).

Churchill’s words seem shocking today, but they reflected orthodox British imperial attitudes toward Indians in the mid-twentieth century. Tragically, this dehumanization carried significant policy implications that affected the lives of millions, notably during the great Bengal famine of 1943. Several scholarly works have examined the Bengal famine in disciplines like economics (Goswami, 1990; Sen, 1977), history (Islam, 2007; Mukherjee, 2015; Tauger, 2003), and English literature (Bhattacharya, 2016), but geographers have never contributed to this body of work. This paper seeks to fill this void.

Geographical interpretations of hunger and famine have become more sophisticated over time. Scholars in famine studies who examined the complex phenomenon of famine gradually realized that famines can hardly be explained by any single, overarching theory (Devereux, 1993); rather, famines reflect complex constellations of social and environmental forces. A predominant line of thought was that of Malthus, who blamed the occurrence of food shortages on overpopulation and these Malthusian beliefs were common among British colonial administrators who interpreted famine as examples of Darwinian natural selection (Tauger, 2003). The idea of ‘complex emergencies’ introduced by Keen (2008) and later adopted by the UN is also worth mentioning in this respect, as colonial famines are manifestations of ‘conflict- generated emergencies.’ The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) defined a complex emergency as a “humanitarian crisis in a country, region, or society where there is total or considerable breakdown of authority resulting from internal or external conflict [that] requires an international response that goes beyond the mandate or capacity of any single agency and /or the ongoing United Nations country program” (Keen, 2008, p. 2).

Famine studies have been transformed in recent times and the focus on the causes of famine has been relocated from crop failures to the consequences of economic relations, social structures, and political actions (Tauger, 2003). In essence, the understanding of famine shifted from Malthusian to a much more politically informed one. Concomitantly, as geographers’ understanding of power and politics evolved, they delved into biopolitics (Foucault et al., 2008) and subsequently colonial biopolitics (Nally, 2008). This line of thought emphasized the geopolitics of famine as well as the analysis of colonial bodies, which were subject to European panopticism, monitoring and regulation. Such a perspective is useful in unveiling the political dynamics of famines, how they are produced and reproduced over time and space, and how they were contested.

This paper explores the infamous Bengal famine of 1943 by visualizing it through the lens of colonial biopolitics. It seeks to expose the colonial strategies and utilitarian principles of the British government. It highlights the role of the British government during this crisis and how the British viewed Indian bodies. This essay seeks to comprehend the local and global politics of the famine as they were enveloped in the geopolitics of World War II, during which the British colonial authorities were far more concerned about a Japanese invasion of South Asia than they were with the lives of people dying of hunger. This paper lays out the argument of how the British prioritized their military needs during World War II and how colonial authorities utilized Bengal’s resources and labor power for a war effort even during a catastrophic famine. It also points out how the famine was exacerbated by the British authorities due to their incompetence and implementation of various erroneous governmental policies.

The principal aim of biopolitics is to turn individuals into governable objects, and colonial famines in India provide a perfect context to examine the role of biopolitics in consolidating and expanding bio-inequality in the Global South and how indifferences of those at the top of the power structures disregard the bodies of the poor people forcing them to die. Geographers have never used the concept of biopolitics in their attempts to comprehend the colonial famines that occurred in India. When seen through the perspective of biopolitics, I believe that researching colonial famines in India offers up new research avenues to interpret biopolitics empirically. Adopting a biopolitical approach helps us to critically analyze how the use of statistics and surveys categorized populations based on factors such as race, religion, class, caste, gender, and so on during a disaster. To the best of my knowledge, no geographer has studied the Bengal Famine of 1943 yet, and I believe that this vacuum could be filled profitably given geographers' interest in spaces of violence, development, colonialism and famines. I want to draw attention here to the geographical silences in studying colonial famines in India and how famines in Bengal inform biopolitics in critical geographical thought.

This paper begins with a discussion of the literature on famine, including the critical analyses of scholars in famine studies. The second section lays out a brief account of the historical context of famines in colonial India. The third part delves into the Great Bengal famine of 1943, foregrounding its context and background, debates concerning the famine’s origin, and the role and responsibilities of the colonial authorities featuring the various policies created by the British government during the holocaust. The final section underscores how colonial biopolitics intertwined with power relations and racism affected the most vulnerable members of the society. The conclusion summarizes the major themes and proposes future avenues of research.

Theoretical Perspectives on Famine

The definition of famine evolved from hunger, food shortages and mass starvation to include war, poverty, and market failure (for details see Devereux, 1993, pp. 10–18). Famine relief at the appropriate time was especially considered and researchers began focusing on the food distribution system rather than just on total crop production and food availability (Sen, 1981). The number of people affected, and the mortality rate became important parameters in separating famines from starvation as starvation distresses small groups of people compared to famines. In the event of a famine, people will starve to death unless external food supplies and intervention are provided. In addition to mortality, the concept of ‘excess mortality’ was incorporated (Alamgir, 1980), which consists of more deaths than normally demographically expected. Famines, according to de Waal (2017), are social, economic, and political phenomena; famines are related to production, market, and political or military shocks, even if these aspects are not present at the same time.

Famine theories also transformed through several bodies of research and debates. According to Devereux (1993), prosperous nations seldom face famines because markets are interconnected, and economies are open. As a result, the supply and demand dynamics of food play a significant role in the development of famines. Sen (1982) argued that a major cause of famine is not a sudden decline in food availability, but a sudden redistribution of whatever food is available, highlighting the deeply political nature of famines. Watts (1993) emphasized that while impoverished people are disproportionately affected by famine, hunger, and malnutrition, not all poor people are equally vulnerable to hunger. Vulnerability in this context is crucial here and it is defined by the mechanisms that explain why certain people are more prone than others to suffer from hunger or malnutrition.

Perspectives on famine changed from crude Malthusianism to ‘political events’ and eventually to biopolitics. One example is the paper by Nally (2008), who examined the Irish famine of the 1840s and dissected it from the perspective of colonial biopolitics. Famines were a way of controlling or terrorizing the population so that they would acquiesce to British rule. He highlighted how the Great Irish Famine (1845–1852) was shaped by a particular colonial regulatory order to exploit the catastrophe and maximize state power, thus driving Irish life by a logic both deeply colonial and biopolitical.

Sen (1982) developed the entitlements approach for interpreting famine. In this approach, in a market economy, a person can exchange what he or she owns for a different collection of commodities. He or she can do this exchange either through trading or production or a combination of both. These analyses define why some groups of people who belong to specific occupations such as landless laborers, informal sector workers, artisans, pastoralists, and service- people as vulnerable (Watts & Bohle, 1993). Michael Watts envisaged this exchange-entitlement model as a logical first step in building a historical account of famines in different social formations. Famine scholars such as Amrita Rangasami (1985) similarly reminded us that famine “cannot be defined with reference to the victims of starvation alone and the great hungers have always been re-distributive class struggles: ‘a process in which benefits accrue to one section of the community’ while losses flow to the other” (quoted in Davis, 2002, p. 22).

Colonial Biopolitics and Famine

Michel Foucault (1981) used the term biopolitics for investigating governing practices in modern times. The regulation of the population is referred to as ‘biopolitics’ and was initially accomplished by “diagnosing and dealing with a population that was conceived in the abstract, such as by birth rates, infant mortality, and longevity” (Legg, 2005, p. 139). Foucault (2007) introduced the notion of biopolitics (see Foucault, 2003, 2007), which is defined as “the state-led management of life, death, and biological being a form of politics that placed human life at the very center of its calculations” (quoted in Nally, 2008, p. 716). Food crises and disease were conceived by authorities to be “public health” issues requiring new regimes of calculation, intervention, and direction and these crises are not necessarily accompanied by the prevention of famines or other catastrophes, but rather “allowing them to happen and then being able to orientate them in a profitable direction” (Nally, 2008, p. 717).

Nally (2008), in describing the Irish famine, explored the British government’s famine relief policies and how different laws and disciplines permitted the colonial state to target subaltern bodies. Even though Ireland and Bengal were very different in culture and context, both were British colonies and both experienced famines. In this instance, I am not blindly exporting the model from Ireland to India; rather, I am applying Nally’s broad analytical approach but paying attention to the unique specificities of biopolitics in India. During the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, held during the Irish famine, Britain's superiority in invention and technology was brazenly showcased to the whole world. Analogous to the 1943 Bengal famine, the British colonial authority blamed the Irish famine on natural causes, accusing nineteenth century Ireland of being overpopulated to avert such misery.

Biopower has long been associated with the management of famines and the implementation of controls, surveillance, and regulations to handle disease epidemics. The concept of biopower evolved from its original connotation of enslavement of bodies and control of the population (Legg, 2006). Among the numerous approaches used to achieve this control were demographic science, the census, statistical analyses, and the interrelationship between a territory’s resources and its occupants. Foucault (2003, p. 256) while describing biopower writes “in a normalizing society, you have a power which is…a biopower, and racism is the indispensable precondition that allows someone to be killed, that allows others to be killed”. He noted that by ‘killing’, he never meant direct killing or murder, but it is indirect murder in every other form i.e., “the fact of exposing someone to death, increasing the risk of death for some people, or, quite simply, political death, expulsion, rejection and so on” Biopolitics thus is the power to ‘make’ live and ‘let’ die.

The various ways by which a state manages its people and territories are referred to as its governmentality (Foucault, 1978). Governmentality, according to Foucault (1981, p. 139; 1979, p. 213) includes the “exercise of discipline over bodies and ‘police’ supervision of the inhabitants of the sovereign’s territory.” As Heath and Legg (2018, p. 1) write “Enacted through institutions (such as the family or school), discourses (such as medicine or criminal justice) and procedures and analyses (such as surveys and statistics), governmentality aims to maintain a healthy and productive population.” Sasson and Vernon (2015) claimed, in analyzing the actions of British authorities throughout past famines, that it was not until the Irish famine that they understood famines could be prevented, and the notions of launching relief began between 1846 and 1883, intending to civilize the colonial people. One notable trait shared by the colonial famines of Bengal and Ireland is that many lives may have been saved if effective policies had been adopted at the appropriate times (Nally, 2011a, 2011b). Several forms of colonial governmentality were called into question, including the organization of famine camps based on who could work 12 h a day and who would just get relief. Residency in the camps was made mandatory, and restrictions were imposed to purchase only specific amounts of grains. Duncan (2020) emphasized the British authorities' state-sanctioned atrocities, such as withholding food from prisoners, evicting people from their lands, and employing police constables, minor court officials, and prison guards while paying them a pittance and entrusting them with the job of enforcing the law.

Famines can also be visualized as another form of excessive geopolitics as Chaturvedi (2003) argued that the partition of India (a direct consequence of British imperial mapping) is a perfect example of excessive geopolitics, tearing apart the country of India into communities of Hindus and Muslims, resulting in never-ending conflicts and violence. He raises the issue of geopolitical imaginations and images of India, posing the question of whose land was partitioned, thereby claiming that excessive geopolitics transforms borders into rivalries such as 'our' land vs. 'their' land. Divisive categories such as religion, caste, tribe, and community were implanted at the core of the social structure of India by the British rulers. Legg (2006) argued that maps were used as a means of regulating space. These maps obscured the tales underlying local struggles and conflicts, and so served as a vehicle for fresh calculations of territorial conquest and forcible land acquisition.

A Brief Geo-history of Famines in South Asia

Famines were frequent phenomena throughout South Asian history, but it was not until the establishment of colonial censuses and vital registration after the 1860s that their demographic characteristics could be accurately analyzed. Famines were also widespread throughout the pre-colonial period, albeit they were far less severe and frequent than during the colonial period (for further information on the famines of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, see (Parwez & Khan, 2017, p. 35). It is also worth noting that historians lack extensive data on pre-colonial famines due to low literacy rates in medieval and ancient times, a lack of censuses, modern record-keeping systems, mass media, and other modern modes of communication such as telephones, telegrams, trains, and aircraft. Famines occurred mostly because of the aftereffects and damage of wars and rebellions throughout the Mughal dynasty. Khondker (1986) claimed that pre-British famines were caused by localized food shortages for a limited time, but colonial famines were caused by repeated economic crises when a significant number of people were unemployed with no income to buy food. The reasons for the periodic occurrence of famines in colonial India have been long debated. Although other reasons such as colonial exploitation, population expansion, and global geopolitics were blamed for these calamities, El Niño-induced droughts and the failure of monsoon rains over South Asia were widely viewed as the proximate cause in each of these 19th-century famines (Purkait et al., 2020). There were approximately 25 major famines during the British Raj (the period of rule by the British Crown over the Indian subcontinent from 1858 to 1947 following the dissolution of the British East India Company). Tharoor (2018, p. 235) points out that from 1770 to 1900, 25 million Indians are estimated to have died in famines, compared to only 5 million deaths throughout the entire world from wars from 1793 to 1900.

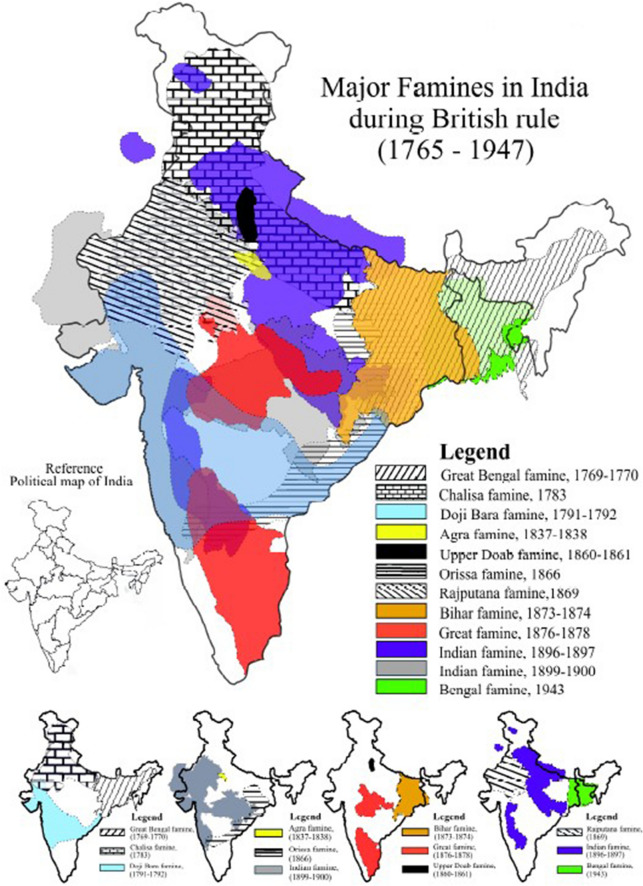

Among the countless famines that India suffered, Bengal was affected most severely. The first and worst of these was in 1770, which is estimated to have taken the lives of 10 million people The Great Bengal Famine of 1770 was the first of the horrendous famines and it opened the door to future famines in South Asia during colonial rule. The list of major famines during the British rule as pointed out by Tharoor (2016) are: The Great Bengal Famine (1770), Madras (1782–1783), Chalisa Famine (1783–1784) in Delhi and surrounding areas, Doji bara Famine (1791–1792) around Hyderabad, Agra Famine (1837–1838), Orissa Famine (1866), Bihar Famine (1873–1874), Southern India Famine (1876–1877), Bombay Famine (1905–1906) and the Bengal Famine (1943–1944). Purkait (2020) illustrated the 12 major famines during the British Rule (1765-1947), which were unevenly distributed throughout the colony (Fig. 1). The famine in 1876–1878 initiated the foundation of the first Indian Famine Commission of 1880 that consequently laid the commencement of India's subsequent relief system, namely the Famine Codes (Maharatna, 1992).

Fig. 1.

Major Famines India during British Rule.

Source: (Purkait et al., 2020)

The Great Bengal Famine of 1943

The Bengal famine of 1943 was one of the worst disasters in twentieth century South Asia. It was devastating in terms of its scale, causing three million deaths and occurred during the midst of World War II, when India was under the British Raj. This period during the Second World War, Asia faced several famines simultaneously. Other famines that occurred during the same time as Bengal included the Henan Famine in China (1942–1943), as well as the Vietnamese famine in 1944–1945. The estimates of the magnitude of mortality during the Great Bengal famine of 1943 have been questioned. The famine took the lives of 3 million people, which is the cited maximum (Dyson & Maharatna, 1991). Before the partition of the Indian colony in 1947, Bengal included the state of West Bengal in India and present-day Bangladesh. Its most important and populous city was Calcutta (now Kolkata). From 1772 to 1911, Calcutta was the capital of colonial India. From 1912 until today, Calcutta has been the capital of the state of West Bengal in India.

The main causes of the Bengal famine of 1943 accepted by many researchers after innumerable debates are: (a) an absolute shortage of rice, due to the loss of imports from Burma, and rice exports from Bengal to Sri Lanka (since it was one of the strategic bases against Japan; the British called it Ceylon) and to those regions of the British empire that could not get rice from Southeast Asia after the fall of Burma; (b) the 'material and psychological' consequences of World War II, creating a drastic increase in the price of rice; (c) the incompetence of the government of Bengal to control the supply and distribution of food grains in the market, thus generating large scale hoarding; (d) delayed response after the onset of famine; and (e) the government of India's procrastination in putting into operation a nation-wide system of moving supplies from food surplus to deficit areas (Law‐Smith, 2007; Mishra, 2000).

One important characteristic of the famine that Sen (1977) noted was it created an uneven expansion of incomes and purchasing power. People who were involved in military and civil defense works, in the army, or industries associated with war activities were covered by distribution arrangements and subsidized food prices. Ó Gráda (2015) pointed out that more than half of India’s war-related output was produced in Calcutta and the number of military workers in the city was one million. As a result, they could access abundant supplies of food while others faced the consequences of rising food prices. Impoverished families sold their lands in exchange for stacks of rice. Due to this gruesome situation, the city of Calcutta witnessed crimes such as selling girls and women and even consumption of meat from dead cows.

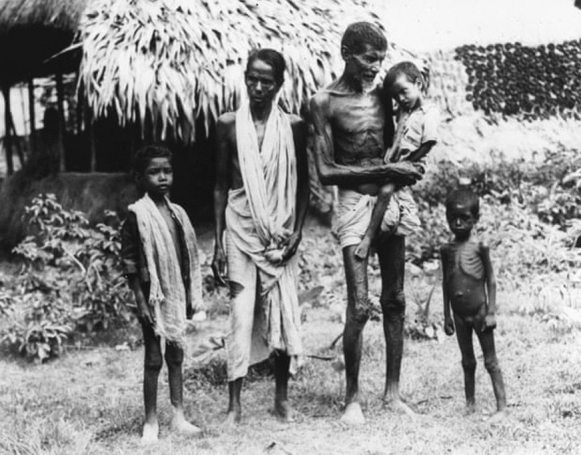

Calcutta witnessed the famine in the form of destitute masses from the rural areas who travelled there from the surrounding rural districts. People thought if they could move to Calcutta, they had a better chance of survival than anywhere else in Bengal because the city had so many people engaged in war-related activities (Mukherjee, 2015). Figure 2 depicts a picture of a family who moved to Kolkata to obtain food. Charitable organizations offered relief by providing meals in their kitchens. Meals were given at the same time of the day in more than one kitchen, which prevented poor people from getting more than one meal. The soup supplied in the kitchens was cooked with low-quality millet and vegetables. Collingham (2012) observed that poor food quality in the kitchen induced ‘famine diarrhea’, which resulted in more fatalities. In the same vein, Nally (2011a, 2011b, p. 221) argued that material space acted as a means of biopolitical regulation as during the Irish famine, several locations, like as "workhouses, food depots, soup kitchens, public work operations, outdoor relief schemes, allowed the state to target and manage Irish destitution.". The famine swept across at least 60% of Bengal's net cultivable area, affecting more than 58% of the rural households and reducing over 486,000 rural families to a state of beggary (Goswami, 1990). The harshest phase of the famine lasted for eight months (March to October 1943) but its impacts were felt for a much longer period, creating starvation and epidemics. Among the numerous devastating effects of the famine, the mass starvation phase culminated in epidemics caused by weak immune systems due to hunger. Throughout Bengal even during the end of January 1944, it is estimated that there was a total of 13,000 hospital beds available for famine victims considering an average of 2300 people dying each day out of starvation and diseases (Mukherjee, 2011). Cholera mortality (58,230 persons) reached its maximum in October and November together with a severe rate of smallpox following thereafter (March and April 1944). Concurrently, malaria peaked in December 1943 (168,592 persons) (Sen, 1982).

Fig. 2.

A family arrived in Kolkata in search of food in November 1943. Photograph: Keystone/Getty images.

Source: The Guardian, March 2019 (https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/mar/29/winston-churchill-policies-contributed-to-1943-bengal-famine-study" https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/mar/29/winston-churchill-policies-contributed-to-1943-bengal-famine-study)

Context and background of the famine

In March 1942, the Japanese Army completed the occupation of Burma (now Myanmar). During this time, there was a serious shortage in rice production as India used to have 15% of its rice imports from Burma. After the capture of Rangoon in 1942, the shipments of Burmese rice to Bengal were stopped by the Japanese army, contributing greatly to the food shortage there (Ó Gráda, 2008). The loss of Japanese imports resulted in the requisitioning of rice reserves in areas vulnerable to the Japanese invasion, as well as large-scale hoarding (Ó Gráda, 2015). Bengal was also lacking wheat, dried legumes, mustard, sugar, and salt. As a result, the wholesale price of rice rose from 14 Rupees (Rs) per maund on December 11, 1942, to 37 Rs per maund by August 20 (1 maund = 37.32 kg) (Sen, 1977).

Alarmed by Japan’s military successes, the British colonial authorities started preparing for a Japanese invasion of eastern and coastal Bengal. They initiated it by executing a scorched-earth policy, seizing and hoarding food supplies (Famine Commission, 1945). The denial policy, a Government of India plan, was implemented by L.G. Pinnell (Director of Civil Supplies until April 1943) in 1942 that played a consequential role before the famine. The policy included two important measures: the removal of rice in excess from coastal districts, and the removal of boats that could carry ten or more passengers to deny supplies and transport to the Japanese. Due to the ‘denial policy of rice’, the districts of Midnapore, Khulna and Bakarganj, which used to have a surplus of rice, were ordered by the colonial authorities to demolish their pre-existing stacks of rice. Moreover, due to the fear of the Japanese invasion, the government of Bengal impounded 66,653 boats, thereby halting all rice movement from surplus zones to the deficit districts of East Bengal (Goswami, 1990). In these districts of Khulna, Midnapore and Bakarganj, the economy of the fishing class was completely shattered. People who were engaged in pottery in different districts went out of trade and their families became homeless, as this industry required large inland shipments of clay.

Aggravating the agony of the people of Bengal, on October 16, 1942, a massive cyclone devastated the coastal areas of Midnapore and 24 Parganas, inundating over 3,200 square kilometers. Midnapore was the largest rice-growing and exporting district of the province. The standing winter rice crop as well as the reserve stocks were destroyed. Besides the deaths of 14,000 people, an estimated 12 million Rupees (Rs) worth of standing and stored rice was lost (Weigold, 1999).

Theories and debates on the causes of the 1943 famine

The reasons behind the causes of the Bengal famine have been widely scrutinized. The Family Inquiry Commission (FIC) was appointed by the Government of India in 1944 to investigate the causes of famine. According to the FIC, the famine was caused by two factors: First, during 1943 there was a serious shortage in the total supply of rice available for consumption in Bengal, as compared to the normal supply (Islam, 2007). Secondly, there was an exorbitant increase in the price of food beyond the purchasing power of people who were usually reliant on the supply of rice in the markets throughout the year.

The Famine Inquiry Commission (FIC) upheld a Malthusian view of food shortages by blaming the local population and explaining that food shortages and famine were routine phenomena of colonial India (Mukerjee, 2014). The Commission blamed natural calamities along with the tendency of Indians to breed excessively. It advocated the Food Availability Decline theory (FAD) by highlighting those shortages of rice were one of the basic causes of the famine (Famine Commission, 1945). The report was viewed as fallacious by different scholars after it was thoroughly investigated as there were discrepancies between the testimonies and the information published by the FIC. (see Mukerjee, 2014).

The degree of crop shortfall in late 1942 and its impact in 1943 have dominated the historiography of the famine. The issue reflects a larger debate between two perspectives: one emphasizes the importance of Food Availability Decline (FAD) as a cause of famine, and the other focuses on the Failure of Exchange Entitlements (FEE). The FAD explanation blames famine on crop failures brought on principally by crises such as drought, flood, or devastation from war. The FEE account agrees that such external factors are in some cases critical, but holds that famine is primarily the interaction between pre-existing "structural vulnerability" (such as poverty) and a shock event (such as war or political interference in markets) that disrupts the economic market for food. When these interact, some groups within society can become unable to purchase or acquire food even though sufficient supplies are available. Both the FAD and the FEE perspectives would agree that Bengal experienced at least some grain shortages in 1943 due to the loss of imports from Burma, damage from the cyclone, and crop disease due to pest attack (Padmanabhan, 1973). However, the FEE analyses do not consider food shortages as the predominant factor.

Academic consensus generally follows the FEE account, as formulated by Amartya Sen, in conceptualizing the Bengal famine of 1943 as an “entitlements famine”. In this view, the prelude to the famine was generalized war-time inflation. The problem was exacerbated by prioritized distribution and abortive attempts at price control. High inflation rates caused a fatal decline in the real wages of landless agricultural workers. Sen (1981) disagreed with the explanation put forward by the Famine Inquiry Commission and affirmed that the Bengal famine was not caused by a decline in food availability, but by a failure of entitlement to food. He termed the Bengal famine an “artificial famine” and emphasized class as one of the main determinants of famine vulnerability. He also pointed out that the supply of rice was just around 5% lower than the previous five-year average and was, in fact, 13% greater than in 1941, even though there was no famine in 1941 (Sen, 1982).

In Bengal during that time, the zamindars (local landlords) were at the top of the revenue-collecting ladder. The peasant or chasi (primarily lower caste Hindus or lower caste Muslims) cultivated the land and paid his rent to the landowner (Mukherjee, 2011). Food hoarding was a crucial factor in the case of this famine. The most noteworthy factor that Sen (1981) emphasized was that in the Bengal famine, it was the underprivileged occupations that were most affected—fishermen, agricultural laborers, and transporters – whereas the beneficiaries were big farmers, merchants, and rice mill owners (Sen, 1977). The inflation benefitted these latter groups, whose incomes soared, and whose food consumption also climbed up. Food was deliberately stockpiled in the village stores of wealthy landlords and tradesmen, who were impatiently awaiting the appropriate moment for inflation to cause price increases (Collingham, 2012). The years 1942 and 1943 experienced inflation across all sectors, predominantly because of high war expenditures due to the Japanese invasion of Burma in 1942. The colonial government financed its expenses by printing more money and the Reserve Bank of India was compelled to print notes about two and half times their total value (Gadgil & Sovani, 1944), creating an enormous increase in prices.

More recently, a groundbreaking work was done by Mishra et al. (2019) who used weather data to study soil moisture levels where they discovered that out of the six major famines between 1870 and 2016 in India, five were linked to soil moisture drought, but that the Bengal famine of 1943 was not caused by drought. Even the rainfall was also above average during that year. They concluded that the 1943 Bengal famine was not caused by drought but rather was a result of a policy failure during the British era. This cutting-edge approach to uncovering the causes of famine during 1943 attracted widespread media attention (Safi, 2019). One study (from a commentary) recently published even conceptualized the Bengal famine as a genocide (please see Mookerjee, 2022).

Responsibility of the colonial authorities

The role and responsibility of the British government during these crisis months were always highly questioned. The interventions by the government of Bengal in the province’s wholesale rice markets in 1942 and 1943 triggered the crisis. Greenough (1982) calculated that even after deducting the losses due to the halt of Burmese imports, the Midnapur cyclone, flood, and crop disease due to pest attack (see Padmanabhan, 1973), 90% of the usual supply of rice was available in 1943. There was also no deficiency of rice in Bihar, Orissa and Assam indicating that there should not have been any shortages in Bengal provided the surplus grain was accurately circulated, which the Indian Government failed to accomplish (Law‐Smith, 2007).

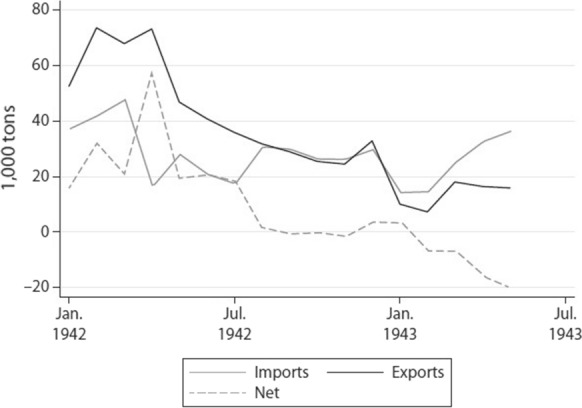

During the famine, the utilitarian principles and profit-seeking attitude of the British administrators dictated that for Britain to satisfy Indian demands, shipping and supplies had to be sourced for British soldiers fighting the Germans at that time. Also, supplying food to Indian civilians would have risked British civilian food supplies. The total amount of wheat harvested in the British Empire during the 1943–1944 year was 29 million tons, but the war cabinet strategically preserved it for the future. So, despite Bengal’s rice shortages, the British Empire had sufficient wheat to send to the famine victims (Mukerjee, 2014). Even in 1943, at the height of the famine, the UK imported 26 million tonnes of food and raw materials for its civilian population, creating a stockpile of 18.5 million tonnes at the end of the year. The Indian Central Food Department intended to set up a central purchasing organization, but the government mismanaged the situation and did not inform the surplus provinces about setting up procurement machinery until the end of January 1943. Bengal expected delivery of 350,000 tonnes of rice between April 1943 to March 1944 from neighboring states, but, unfortunately, received only 25,000 tonnes of rice supplied by Orissa (Law‐Smith, 2007). The total imports and exports during 1942–1943 are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Bengal’s rice trade, 1942–1943.

(Source: Ó Gráda, 2015, p. 59)

It is simplistic to ascribe all the failures by putting the entire blame only on the British government. As mentioned earlier, there were different other complex issues like market failures, policy failures, malfeasance by government agencies, as well as different unethical practices by private companies. A more nuanced view also acknowledges the role of Punjab, which had a surplus of food grains in 1943–1944. There was an ongoing politics between the Punjab peasants’ lobbies and the ruling party that utilized the wartime soaring prices of food grains to compensate for the losses the Punjab peasantry had suffered earlier during the economic depression of the 1930s. The government sought to safeguard its rural vote bank by publicly advocating for allowing the wartime grain markets to operate on a laissez-faire basis (Yong, 2005). Many peasant leaders in Punjab encouraged farmers to resist the procurement of food crops by government agencies at a fixed price. This wartime prosperity of Punjab specifically when Bengal suffered helped to reproduce uneven development within India.

Official declaration and news of this ‘British- induced famine’ were deliberately suppressed from the people of Bengal to serve British interests. In August 1942, Bengal’s chief finance minister, Fazlul Huq, warned colonial authorities of a potential famine because of these policies. He was ignored by the British Governor of Bengal, John Herbert. At the same time, press regulations were employed to interrupt the circulation of any information from Bengal. This was not the first time the government have concealed news of the famine. While researching British responses to famine throughout the last 200 years, Sasson and Vernon (2015) discovered that famine news was not extensively disseminated in the British press and that the key concern was the negative impacts on tax reduction, as noted during the 1770 Bengal famine as well.

Colonial Biopolitics and the Great Bengal Famine of 1943

Racism reduces human beings to the race (phenotype) to which an individual belongs (Sharp, 2008). Racist ideology involves an elaborate classification of mind and personality linked to physical features. In the European geopolitical imagination, any race other than whites was conceived to be more bodily driven in their instincts and even viewed as having animal instincts more tied to the body than their minds (Sharp, 2008). Duncan (2007) demonstrated how race was used as a significant criterion to intensify the internal differentiation within the native Ceylonese population and used as biopower by the British colonizers to fragment and govern the indigenous people in nineteenth-century Ceylon. Race here was analyzed not only as utilized as a useful tool for segregation but also in the context of 19th-century environmental determinism and theories of tropical degeneration. Europeans who were born in Ceylon were regarded inferior to other Europeans born in Europe and close to the indigenous population (Duncan, 2020). Brown bodies were portrayed as disease-prone due to body odor, and these smells were viewed as spreading illness by contaminating the air.

Environmental determinism was defined at the time as the belief that individuals from cooler regions would deteriorate physically, ethically, and psychologically if they spent too much time in the tropics. The heat of the tropics was assumed to change the blood of Europeans, creating tropical anemia. The connection of Indians to land, tradition, and climate was regarded and supposed to be the cause of India's collapse, and tropical climate was blamed by the British as the primary cause of draining away vitality for productive labor. The British feared that their talents would deteriorate because of their intimate interaction with both the natural and cultural environments of India (Duncan, 2007, 2020).

The British generally perceived their colonial subjects as childlike, needing guidance in their every step of how to behave properly. The Indian working classes were believed to lack intellect and were always driven by bodily passions. When the Delhi government sent a telegram to Churchill depicting the horrible devastation generated by the famine and briefed him about the total number of deaths, his response was “Then why hasn't Gandhi died yet?” (quoted in Choudhury, 2021, p. 4). Churchill even claimed that the Indian population were the beastliest in the world after the Germans, the famine was created by themselves caused by overpopulation, and that Indians should pay the price for their negligence (Collingham, 2012). These statements paint a coherent picture of how the British colonial authorities marginalized their colonial subjects and reified racial exclusion.

Power is inscribed as well as resisted on the surface of the skin. In October 1943, when Archibald Wavell arrived in India to assume the post of Viceroy, he faced enormous pressure from Indian politicians for an investigation into the famine in Bengal. Leopold Armery, the Secretary of State was opposed to this investigation and wanted to silence these voices: “My own view was and is that inquiry now would be disastrous and that inquiry at future is undesirable” (quoted in Mukerjee, 2014, p. 71). He wanted to shift the interpretation of famine towards Malthusianism and said, “In the past 12 years the population of India had increased by about 60 million, and it had been estimated that the annual production of rice per head in Bengal had fallen from 384 to 283 lb. in the last 30 years” (quoted in Tharoor, 2018, p. 248). He linked the famine to population growth to divert the attention away from inflationary factors and India’s war effort funds.

As food prices increased, and signs of famine became prominent, in August 1942 the Bengal government launched the Bengal Chamber of Commerce Foodstuffs Scheme, which provided food and distribution of goods and services mainly to workers in high-priority war industries, so that they were forced to stick to their existing positions. These soldiers were more valuable than Indian citizens since they were fighting a war for the British, which was most important to them at the time. To avoid offending the Indian upper classes, the government spared them from high taxes, price limitations, and consumption restrictions during 1942. The backing of India's corporate and industrial classes was critical for the rise of Indian industry, which contributed significantly to the war effort (Collingham, 2012). Surprisingly, Sasson and Vernon (2015) observed that these erroneous relief strategies were gendered as well as dependent on the class. Men were taught that because women and children were not permitted to work, it was the man's obligation to support them. Only in exchange for employment, the underprivileged were given food.

Longhurst (2001, p. 3) argued that bodies play a significant role in people’s experiences of place, and, drawing on work concerned with embodiment and spatiality, she proclaimed, “the body is the potential to prompt new understandings of power, knowledge and social relations between people and places.” Similar notions can be linked to the Bengal famine. For example, the British considered the Greeks to be sturdier than anyone else and prioritized them based on their skin color and body stature. Choudhury (2021, p. 7) highlighted these remarks when Leopold Armery, commented: “Winston may be right in saying that the starvation of anyhow under-fed Bengalis is less serious than sturdy Greeks, but he makes no sufficient allowance for the sense of Empire responsibility in this country.” An additional statement uttered by Lord Wavell was “Apparently it is more important to save the Greeks and liberated countries than the Indians and there is reluctance either to provide shipping or to reduce stalks in this country.”

It is worth emphasizing that while most biographies of Churchill mention the bombing of Germany, none of them includes the 1943 Bengal famine. The absence of this disaster in popular biographies of Churchill symbolizes it as a non-significant event. Hickman (2009, p. 242) analyzed popular Churchill biographies and the 1943 Bengal famine, where he documented one quote when Churchill responded to an American critic of the British Raj: “Before we proceed any further, let us get one thing clear. Are we talking about the Brown Indians, who have multiplied alarmingly under the benevolent British rule? or are we speaking of the red Indians who, I understand, are almost extinct?”.

Orientalism, according to Edward Said (1979), is a discursive and geopolitical assertion of difference between East and West that is written throughout the texts of Western culture, whether through travel diaries, news stories, paintings, or other representations. In the case of orientalism, power was exercised through institutions that described the Orient. The people within the spaces of the Orient were not allowed to speak for themselves but were described and characterized by others (Sharp, 2008). The Orient was always seen as being different and backward from Europe, which was considered developed. Both Heath and Legg (2018) and Duncan (2007) pointed out that in terms of science, Asian sciences were considered far inferior, and like ‘mere children’ in comparison to Europeans. The natives were visualized to be close to nature, but Europeans held that the native people are incapable of modifying nature and were unable to exploit natural resources. The Bengal famine exemplifies this notion, in which the Bengali people were dependent on the British for the allocation and distribution of their resources even in a crisis. Duncan (2007), while exploring the consequences faced by coffee plantation workers noted how industrialization, commercialization, and Western technologies were introduced to the colonial sites for future calculation and enforcing discipline to the plantation laborers. Every ounce of labor was sucked from their body to fulfil the demands of the planters to make more money. Kandyan highlands were deforested to produce coffee that was exported for financial benefits. Just like Ceylon, food grains even could not be imported to Bengal from other neighboring states within India but instead exported (Law-Smith, 2007).

Paralleling orientalism, a unique focus on the notion of subaltern geopolitics by Ashutosh (2019) gives a counter topography of South Asian territories that do not center around the state. He revisited the 1955 Asia-Africa Conference in Bandung, referring to it as the "threshold moment for postcolonial geography" (p. 7) since it depicted an alternate South Asia with the capability implanted in postcolonial nation-states where anticolonialism succumbed to postcolonial state formation. This event transcended national and state lines, serving as a model for overcoming marginalization and forging new kinds of belonging.

Foucault’s biopolitics placed human life as the center of calculations, and rather than preventing a catastrophe, the state-led management or government allowed these calamities to occur to acquire a profit (Foucault et al., 2008). In the Bengal famine, the government’s role in dealing with the famine, including famine relief, was arranged from the vantage point of prioritizing their interests. The primary focus was on winning the ongoing war, and all requirements related to the war were reinforced. Correspondingly, all actions undertaken by the colonial government during the Irish famine were delayed (Nally, 2011a, b). The government's measures and policies (closure of Irish food depots, delayed suspension of the Navigation Act, retraction of the Corn-laws, etc.) were not aimed at alleviating food scarcity or saving Irish lives; rather, they were all strategically implemented to achieve desirable outcomes for the British.

Foucault’s governmentalized state included the population as a field of intervention and political economy was one of the prime objectives of the state. This conception is explicitly portrayed in the Bengal famine. From compelled tax collection during a crisis to forced participation in the war, Bengal was the site of exploitation for the British and the subaltern body served as a platform to exercise their power. Legg (2006) noted that for analyzing the population expansion of Delhi (1911–1947), the released report on the Relief of Congestion in Delhi paid no attention to the working conditions of the workers or the issues of illness and their causes of transmissions. The measuring parameter was the minimal space required for a person, without delving into the underlying issues. Overcrowding and poor sanitation were blamed only for illness transmission, ignoring the socioeconomic consequences of poor living circumstances and poverty. Humans were not viewed as persons but as objects. People were regarded as items that may be discarded at any time in this "extended laboratory of urban modernity" (Legg, 2006, p. 724).

While analyzing Foucault’s discourses on governmentality and biopower, Duncan (2007) argues that while the government has the purpose of managing the welfare and improvement of its people's lifestyle (wealth, health, life span), the assumption surrounding it involves a modern and broadened view of managing and regulating the population. This 'modern' assumption was founded on such goals, which could only be fulfilled by replacing traditional practices and unscientific beliefs with “modern” rational ones. Through agricultural commercialization, colonial regimes in India devastated indigenous agrarian food systems. The physical landscape of India was transformed by the construction of dams, telegraph lines, roads, and railways. Wilson (2016) argued that this geological imperialism was motivated by a desire to enhance a civilization that was perceived to be backward. Often studies (Duncan, 2020; Scott, 1995) include modern governmentality highlighting the daily and moral lives of the colonized population. Scott (1995) asserted that modern power is not about capitalism, but the very point of its application, which is involving the conditions in which a body has to live and define its life and noted how South Asian governmentalities were inaugurated by the insertion of Europe into the lives of colonial subjects.

The government of India begged London for wheat imports, but the colonial authorities instructed the Bengal government to publicly claim sufficiency. Justice Henry Braund of Bengal’s Department of Civil Supplies said that he was told “This shortage is a thing entirely of your own imagination. We do not believe it and you have got to get it out of your head that Bengal is deficit” (quoted in Mukerjee, 2014, p. 72). Similar instances such as the export of food commodities including oats, wheat, and animals from Irish ports had been detected during 1841 during the Irish famine. At the height of the famine, the British colonial authorities did not restrict these exports. As Sen labelled the Bengal famine as ‘artificial’, Nally’s book (2011, p. 12) reiterated the colonial government's “atrificial scarcity of shipping”, which was caused by the compelled importation of food aboard British ships, resulting in exorbitant freight prices.

Geo-power is an amalgamation of technologies of power associated with the management of territorial space and was legitimized by the self-interest of the British government. Mukerjee's work illustrated geo-power where she documented that some of India's grain was also exported to Sri Lanka and Australian wheat sailed past Indian cities to various other destinations in the Mediterranean. Lord Linlithgow, the Viceroy to Leo Amery, stated on January 26, 1943: “Mindful of our difficulties about food I told [Fazlul Huq] that he simply must produce more rice out of Bengal for Ceylon even if Bengal itself went short!” (quoted in Mukherjee, 2015, p. 93). Sinha (2009) argued as far as international politics is concerned, the United States was also reluctant to provide food aid to the Indian victims. The US Congress and the Roosevelt administration did not want to provide favors that might embarrass the British government and arouse opposition. Sinha (2009) reported that in August 1943, Syed Badrudduja, the Mayor of Calcutta, cabled Roosevelt urging the shipment of food grains, but American officials chose to ignore the gruesome situation in Bengal in late 1943. A committee investigating the food supplies of India even declined Canada’s offer of 100,000 tons of wheat for India. Together with this the British government also prevented the Indian legislative assembly from applying to the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration for any food aid.

Social categorization was successfully illustrated in the Bengal famine, reflecting how an atrocity can induce strategic opportunity that was embraced by the British Government. Nally (2011a, b), invoking Foucault’s notion of biopower, illustrates how the government's principle and the exercise of sovereignty acquired a modern connotation by the end of the late eighteenth century using Foucault's idea of biopower and biopolitics. It further states that if foreign foes threaten the sovereign authority, he may continue the battle and order his citizens to participate in the war for the defense of the state. According to Nally's interpretation of Foucault's liberal biopolitical model, starvation is even permitted if it results in a desirable social and economic transformation. This perception can be illustrated by class segregation during the famine. The ‘privileged classes’ of Calcutta who were important to the war effort were supported by rations. Native people were forced to join in the war during the Bengal famine, and they were rewarded by providing meals during the calamity. This sovereign power, therefore, included the authority to make life and death decisions, as well as control and management of the people and land. During a cabinet war meeting, Churchill’s militant policy stated that only those Indians who have a direct contribution to the war effort needed to be fed (Mukerjee, 2014). Sarkar (2020) explored how indigenous factors of caste discrimination and religious communalism worsened famine conditions. With respect to the government free-kitchen, his article (p. 2069) stated that in Calcutta, special relief was added to the middle classes and higher caste people who enjoyed quick distribution of uncooked rice (so that they could take rice into their homes and cook in private), sparing them from the public eating with other lower castes at the relief kitchens.

As a ramification of the British rulers' vision of India, the local people and the land are prepared to accept orders set by the colonial authority. The various dividing divisions of caste, tribe, religion, and community established by colonial administrations can be attributed to excessive geopolitics. During the famine also, these communal conflicts arose throughout the rationing process. Among the 3 million people who died, it is estimated that none of them was from the bhadralok [usually means an educated Bengali man who belongs to a high caste or often what might be called as Hindu-middle class] (Sarkar, 2020). At the end of August, two private groups, the Hindu Satkar Samiti and the Anjuman Mofidul Islam, were selected to dispose of deceased remains associated with religious affiliation. Hindu remains were intended to be brought to the burning ghats, whereas Muslim bodies were supposed to be transferred to the burial sites. These distinctions were even considered in light of the deplorable state of the corpses after death (Mukherjee, 2015).

The 1943 famine is not the only example of ‘utilitarian principles’ implemented by colonial officials as a result of the ongoing World War II; similar incidents were also witnessed during the 1770 Great Bengal Famine, in which it was believed that nearly 10 million people died (Greenough, 1982). The East India Company, being a “profit-seeking entity” (Chaudhary et al., 2016, p. 101), continued collecting taxes ruthlessly even after the famine. It was not only in the 1943 famine that there were debates about the causes; different literature on the 1770 famine also argued that the severity of the 1770 famine was augmented due to the self-serving interests of the British officials who prioritized the profits that the Company could make by collecting revenues from Bengal as this forced tax collection increased the company’s revenue assessments by 10%. de Waal (2017) holds that the East Indian Company is a "villain" since it was directly responsible for the continual number of famines that have occurred since its inception.

Hegemony is always contested, and this is evidenced during several instances before the onset of the famine. There was massive resistance to governmental policies and schemes, several political movements, protests, and rebellions throughout India and Bengal from the beginning of the twentieth century. Some notable movements were the ‘first’ partition of Bengal in 1905, followed by the Swadeshi Movement (1905–1917; again from 1918 to 1947), the Khilafat Movement and Communal Violence (1919–1924), and Quit India Movement (August 1942) just before the Bengal famine (please see Bhowmik, 2021 for details of these movements and the role of Bengal to understand the political context). There was severe unrest in India during 1942 since Indians were reluctant to fight a war that never assured them that they would obtain their freedom. In August 1942, the Indian National Congress called for civil disobedience to oppose the colony’s compelled participation in World War II. The British authorities arrested more than 90,000, people and killed up to 10,000 political protesters (Mukerjee, 2011). Comparably, when the native Ceylonese people attempted to challenge hegemony, they suffered in the same way as colonial Indians did. Duncan (2007, p. 35) documented how everyday violence was exercised by the British colonizers on the Ceylonese people. Some examples are beating suspects for getting confessions to solve the cases and punishing prisoners whose families were unable to pay bribes. These incidents illustrate how “tropical colonies became laboratories of modern governmentality.”

Conclusion

The colonial landscape was not only a place to exert unequal power relations but also a surface to extract resources, creating various conflicts where both the colonizer and the colonized groups were involved and bound together. The British discriminated against Indians predicated on location and class (rural vs. urban, rich vs. poor) and implemented several policies that amplified the famine. The Indian landscape, the people, and their resources were all taken for granted, rendered invisible, and deprived of a voice in managing their own food shortage.

This paper illustrates that social relations are inevitably embodied, and power relations do not operate only from above (i.e., between colonizers and the colonial subjects), but as Amartya Sen demonstrated, can emanate from below and within the same community or family. In this famine, the privileged classes did not face the same consequences as the poor and the landlords (who belonged to the same community) took advantage of the inflated prices of food. This process accentuated income inequality.

This study not only focuses on food shortages in the twentieth century in Bengal, but it also argues for the need for further research today in this region about sustainability and adaptive measures to climate change in vulnerable communities. I want to give the example of Sundarbans here in this context, which is a climate change vulnerability hotspot. Sundarbans (a mangrove area in both West Bengal and Bangladesh's delta region) is susceptible to tropical cyclones and has been ravaged by numerous cyclones in the recent past, including Fani (May 2019), Bulbul (November 2019), Amphan (May 2020), and Yaas (May 2021). Due to these storms, farmlands and the houses of farmers were inundated with saline water. Several natural disasters in the recent past together with strict lockdown restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic have repeatedly devastated people’s source of income and livelihood, resulting in food insecurity in this region. I would want to propose that research integrating biopolitics and food scarcity is necessary and required to address and combat any food crises in Bengal, both now and in the future.

The Bengal famine depicts how colonial biopolitics unfolds, where the laws, and policies were implemented only to serve the British government’s priorities. It reflected how the colonial landscapes were molded and how strategies of power were incorporated to categorize, control, and reform the citizens of Bengal. People were used as laborers to fulfil British goals and were forced to participate in the war. This appropriation perpetuated the interests of the British colonizers and I argue for a deeper understanding of how this subjugation of power was internalized by the Indian people.

Geographers have not studied the Bengal famine of 1943, and one of the principal purposes of this paper is to fill this void. This paper can serve as a stepping-stone to studying famines by geographers that occurred under colonial rule in India and elsewhere. Work on colonial biopolitics offers a multi-scalar perspective in which the world system and the bodies of the victims of the famine are intimately tied together. The argument that I want to highlight in this article is that biopolitics not only informs famine, but famine also informs biopolitics, thereby contributing to theory and reinforcing the empirical value of biopolitics. While few Indian researchers have deployed biopolitics in animal geographies, the notion is yet to be applied in the context of Indian famines.

Geographers have overlooked the event of the Bengal famine and I suggest the discipline has much to offer considering its nuanced understanding of space and place. This paper focuses on how politics and place are intertwined with one another and how British colonial politics remade the place of Bengal. It reveals how colonial biopolitics became part of the place-based strategy, which is so similar to the Irish famine. The famine was used by the British to reaffirm their sense of superiority in that they reduced their Indian subjects to animal-like beings incapable of controlling their reproduction. The British colonial authorities used landscapes as a tool to naturalize British superiority. This paper seeks to bring the literature of biopolitics and famine into a dialogue with one another. The reverse relationship of famine also informing biopolitics has never been acknowledged before in the context of Indian famines during the colonial period. The Bengal famine of 1943 will always remain a historic tragedy and a symbolically significant event in the light of the colonial past, which was transformed into a socially constructed catastrophe by the British colonizers.

Acknowledgements

I am very much grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive and insightful comments and suggestions. I would also like to thank the Editor for his helpful comments and his support during the review process. All remaining mistakes are my own.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alamgir M. Famine in South Asia. Oelgeschlager, Gunn & Hain, Publishers Inc; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ashutosh, I. (2019). Postcolonial geographies and colonialism's mutations: The geo‐graphing of South Asia. Geography Compass, 14(2), e12478.

- Bhattacharya S. Colonial governance, disaster, and the social in Bhabani Bhattacharya’s novels of the 1943 Bengal famine. Ariel: A Review of International English Literature. 2016;47(4):45–70. doi: 10.1353/ari.2016.0032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmik M. The 1943 Bengal Famine: A Brief History of Political Developments at Play. International Journal of Studies in Public Leadership. 2021;2(1):79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bowbrick P. The causes of famine: a refutation of Professor Sen's theory. Food Policy. 1986;11(2):105–124. doi: 10.1016/0306-9192(86)90059-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi S. Towards a critical geography of partition(s): Some reflections on and from South Asia. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space. 2003;21(2):148–154. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary L, Gupta B, Roy T, Swamy AV. A new economic history of Colonial India. Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, S. (2021). Bengal Famine of 1943: Misfortune or Imperial Schema.Cognizance Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 1(5), 15-21. 10.2139/ssrn.3452678

- Collingham L. The taste of war: World War II and the battle for food. Penguin Publishing Group; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Daley P. Lives lived differently: Geography and the study of black women. Area. 2020;2020(52):794–800. doi: 10.1111/area.12655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das D. A relook at the Bengal famine. Economic and Political Weekly. 2008;43(31):59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. Late victorian holocausts: El Niño famines and the making of the third world. Verso Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux S. Theories of famine. UK: Harvester Wheatsheaf; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- de Waal A. Mass starvation: The history and future of famine. Polity Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds K. Political geography III: Critical geopolitics after ten years. Progress in Human Geography. 2001;25(3):469–484. doi: 10.1191/030913201680191790. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JS. In the shadows of the tropics: Climate, race and biopower in nineteenth century Ceylon. Ashgate; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JS. Resisting the rule of law in nineteenth-century ceylon: Colonialism and the negotiation of bureaucratic boundaries. Routledge; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson T. On the demography of South Asian famines: Part I. Population Studies. 1991;45(1):5–25. doi: 10.1080/0032472031000145056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson T, Maharatna A. Excess mortality during the Bengal famine: A re-evaluation. Indian Economic and Social History Review. 1991;28(3):281–297. doi: 10.1177/001946469102800303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Famine Commission. (1945). The famine inquiry commission final report-1945. Madras and Delhi: Indian Government Press.

- Foucault M. Governmentality. In: Faubion JD, editor. Essential works of foucault, 1954–1984: Power. London: Penguin; 1978. pp. 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. Discipline and punish; The Birth of the Prison. Vintage Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. The history of sexuality: Volume I, an introduction. London: Penguin; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. Society must be defended: Lectures at the college de France 1975–1976. New York: Picador; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. Security, territory, population: Lectures at the College De France, 1977–78. Palgrave Macmillan; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M, Davidson AI, Burchell G. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978–1979. Palgrave Macmillan; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gadgil DR, Sovani N. War and Indian economic policy. Gokhale institute of politics and economics. Oriental Watchman; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Gráda CÓ. The ripple that drowns? Twentieth-century famines in China and India as economic history. Economic History Review. 2008;61(s1):5–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0289.2008.00435.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gráda CÓ. Eating people is wrong, and other essays on famine, its past, and its future. Princeton University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami O. The Bengal famine of 1943: Re-examining the data. Indian Economic and Social History Review. 1990;27(4):445–463. doi: 10.1177/001946469002700403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenough PR. Prosperity and misery in modern Bengal: The famine of 1943–1944. Oxford University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Heath D, Legg S. Introducing South Asian governmentalities. In: Legg S, Heath D, editors. South Asian governmentalities: Michel foucault and the question of postcolonial orderings. Cambridge University Press; 2018. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman J. Orwellian rectification: Popular Churchill biographies and the 1943 Bengal Famine. Studies in History. 2009;24(2):235–243. doi: 10.1177/025764300902400205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Islam MM. The Great Bengal famine and the question of FAD yet again. Modern Asian Studies. 2007;41(2):421–440. doi: 10.1017/S0026749X06002435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur R. The vexed question of peasant passivity: Nationalist discourse and the debate on peasant resistance in literary representations of the Bengal famine of 1943. Journal of Postcolonial Writing. 2014;50(3):269–281. doi: 10.1080/17449855.2012.752153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keen D. Complex emergencies. Wiley; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Khondker H. Famine policies in pre-British India and the question of moral economy. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 1986;9(1):25–40. doi: 10.1080/00856408608723078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Law‐Smith, A. (2007). Response and responsibility: The government of India’s role in the Bengal famine, 1943. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies.

- Legg S. Foucault’s population geographies: Classifications, biopolitics and governmental spaces. Population, Space and Place. 2005;11(3):137–156. doi: 10.1002/psp.357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Legg S. Governmentality, congestion, and calculation in colonial Delhi. Social and Cultural Geography. 2006;7(5):709–729. doi: 10.1080/13698240600974721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Longhurst R. Bodies: Exploring fluid boundaries. Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalanobis P, Mukherjea R, Ghosh A. A sample survey of after-effects of the Bengal famine of 1943. Sankhyā: the Indian Journal of Statistics (1933–1960) 1946;7(4):337–400. [Google Scholar]

- Maharatna, A. (1992). The Demography of Indian Famines: A Historical Perspective. [Ph.D. dissertation, London School of Economics and Political Science (United Kingdom)]. http://etheses.lse.ac.uk/1279/.

- Mishra A. Reviewing the impoverishment process: The Great Bengal famine of 1943. Indian Historical Review. 2000;27(1):79–93. doi: 10.1177/037698360002700106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra V, Tiwari AD, Aadhar S, Shah R, Xiao M, Pai DS, Lettenmaier D. Drought and famine in India, 1870–2016. Geophysical Research Letters. 2019;46(4):2075–2083. doi: 10.1029/2018GL081477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mookerjee SP. Bengal famine: An unpunished genocide. Global Collective Publishers; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mukerjee M. Churchill’s secret war: The British empire and the ravaging of india during world war II. Basic Books; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mukerjee M. Bengal famine of 1943: An appraisal of the famine inquiry commission. Economic and Political Weekly. 2014;49(11):71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, J. (2011). Hungry Bengal: War, Famine, Riots, and the end of Empire 1939–1946 [Doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan] Proquest Theses and Dissertation Archive. https://www.proquest.com/docview/896352582?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

- Mukherjee J. Hungry Bengal: War, famine, and the end of empire. Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nally D. “That coming storm”: The Irish poor law, colonial biopolitics, and the Great Famine. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2008;98(3):714–741. doi: 10.1080/00045600802118426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nally D. The biopolitics of food provisioning. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 2011;36(1):37–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2010.00413.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nally DP. Human encumbrances: Political violence and the Great Irish Famine. University of Notre Dame Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Osmani, S. R. (1993). The Entitlement Approach to Famine: An Assessment. World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU/WIDER).

- Padmanabhan SY. The Great Bengal Famine. Annual Review of Phytopathology. 1973;11(1):11–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.11.090173.000303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parwez M, Khan E. Famines in Mughal India. Vidyasagar University Journal of History. 2017;5(2016–2017):21–45. [Google Scholar]

- Portillo, M. (2007). The Darien Scheme (Series.3) [Audio Podcast episode]. In Things We Forgot to Remember. BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/b008kh18

- Price P. Race and ethnicity II: Skin and other intimacies. Progress in Human Geography. 2013;37(4):578–586. doi: 10.1177/0309132512465719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Purkait P, Kumar N, Sahani R, Mukherjee S. Major Famines in India during British Rule: A referral map. Anthropos India. 2020;6:61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Rangasami, A. (1985). Failure of exchange entitlements. Theory of famine: A response. Economic and Political Weekly, 1797–1801.

- Safi Michael. (2019, March 29th). ‘Churchill's policies contributed to 1943 Bengal Famine- Study’. The Guardianhttps://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/mar/29/winston-churchill-policies-contributed-to-1943-bengal-famine-study.

- Said E. Orientalism. Pantheon Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar A. Fed by famine: The Hindu Mahasabha’s politics of religion, caste, and relief in response to the Great Bengal famine, 1943–1944. Modern Asian Studies. 2020;54(6):2022–2086. doi: 10.1017/S0026749X19000192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sasson T, Vernon J. Practising the British way of famine: Technologies of relief, 1770–1985. European Review of History: Revue Européenne D’histoire. 2015;22(6):860–872. doi: 10.1080/13507486.2015.1048193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D. Colonial governmentality. Social Text. 1995;43:191–220. doi: 10.2307/466631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sen A. Starvation and exchange entitlements: A general approach and its application to the great Bengal famine. Cambridge Journal of Economics. 1977;1(1):33–59. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.cje.a035349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sen A. Ingredients of famine analysis: Availability and entitlements. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1981;96(3):433–464. doi: 10.2307/1882681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen A. Poverty and famines: An essay on entitlement and deprivation. Oxford University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp J. Geographies of Postcolonialism. Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Simonow J. The Great Bengal famine in Britain: Metropolitan campaigning for food relief and the end of empire, 1943–44. The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 2020;48(1):168–197. doi: 10.1080/03086534.2019.1638622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha M. The Bengal famine of 1943 and the American insensitiveness to food aid. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 2009;70:887–893. [Google Scholar]

- Tauger MB. Entitlement, shortage, and the 1943 Bengal famine: Another look. Journal of Peasant Studies. 2003;31(1):45–72. doi: 10.1080/0306615031000169125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tharoor, S. (2010, November 29). The Ugly Briton. TIME. https://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2031992,00.html

- Tharoor S. An era of darkness: The British empire in India. Rupa Publications; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tharoor S. Inglorious empire: What the British did to India. Penguin; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tinker H. A forgotten long march: The Indian Exodus from Burma, 1942. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 1975;6(1):1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0022463400017069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watts MJ, Bohle HG. Hunger, famine and the space of vulnerability. GeoJournal. 1993;30(2):117–125. doi: 10.1007/BF00808128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weigold A. Famine management: The Bengal famine (1942–1944) revisited. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 1999;22(1):63–77. doi: 10.1080/00856409908723360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. The chaos of empire: The British Raj and the Conquest of India. PublicAffairs; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yong TT. The Garrison state: Military, Government and Society in Colonial Punjab, 1849–1947. SAGE Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]