Abstract

Improving quality and operational practices in education organizations and developing a culture of continuous improvement are crucial yet challenging endeavors because of the complex nature of education organizations. While quality management practices can clearly improve the quality of these organizations in several aspects, empirical research for quality management in educational organizations is sparse because of the lack of suitable frameworks for assessing quality. In this paper, we present the first large-scale empirical study of implementing quality management practices in educational organizations in the United States. It is based on seven years of objective data for quality assessments by external professional reviewers as part of the U.S. government’s Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (MBNQA) program. Our findings provide empirical evidence for the reliability and robustness of the Baldrige model as an effective quality assessment for educational organizations. Controlling for the applicant’s year, our findings show that Information and knowledge management is a key influencer and predictor of Customer satisfaction and focus, and Management of process quality is a key influencer and predictor of Quality and operations results. This study also provides effective insight and recommendations for how to improve quality systems and achieve business excellence in educational organizations using the Baldrige model. The findings will therefore help managers and administrators to make informed decisions about key factors that impact quality in educational organizations.

Keywords: Quality management, Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (MBNQA), Educational organizations, Quality results

Introduction

Over the last several decades, quality management principles have shaped organizational thinking and business practices to improve organizational processes and achieve better customer satisfaction (Kok et al. 2001; Gonza´lez-Cruz et al. 2018; Parast and Golmohamamdi 2019). Although quality management research has helped both manufacturing organizations and service organizations to improve their quality and organizational processes, one important segment of the economy has had limited discussion in scholarly research: educational organizations.

The main challenge to understanding and implementing quality management in education is a lack of clarity about what quality means in the education context (Brockerhoff et al. 2015; Dicker et al. 2019). Quality in education is considered a multi-dimensional term: a term that is simultaneously dynamic and contextual (Krause 2012). There are multiple stakeholders involved in education, adding to the complex nature of managing quality in such a dynamic system (Latif et al. 2019). In addition, the meaning of customers and customer satisfaction is also not clear in education settings. While education can be viewed as a service, it simultaneously deals with both tangible dimensions (e.g., course materials) and intangible dimensions (e.g., advising and serving students) of quality. The ethical and social responsibility dimensions are also important in education settings (Harris et al. 2011), further adding to the complex nature of quality assessment in education.

The first step in understanding quality management in education settings is to develop a quality framework that will provide a holistic approach to understanding quality, using an established quality framework such as the EFQM or Baldrige model (Osseo-Asare and Longbottom 2002; Lomas 2004; Araújo and Sampaio 2014; Martín-Gaitero and Escrig-Tena 2018; Castka 2018). Despite the clear importance of quality in education, very limited scholarly studies have sought to understand quality management practices in education. We therefore aim to address this gap in the literature on quality management and business excellence by applying the model of the Baldridge Performance Excellence Program.

The Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (MBNQA) is an annual assessment program for quality and business excellence led by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), which is a part of the U.S. Department of Commerce. The MBNQA is an effective framework for assessing and improving an organization’s quality and operations, and it is said to be useful and applicable to any type of organization, regardless of size or industrial sector (Bandyopadhyay and Leonard 2016). For a long time, it was not possible to assess the impact of the MBNQA on enhancing organizational quality and operational results because the data for the MBNQA assessments were confidential and not publicly available.1 Therefore, understanding the long-term effect of quality management practices in educational organizations remains an unexplored area that warrants further research.

In this study, we seek to address these gaps by understanding quality practices in educational organizations (public schools, universities, and other non-profit educational organizations). To achieve this, we first examine how quality management practices can improve quality outcomes using the MBNQA criteria. The MBNQA is a robust framework, so it provides an excellent foundation to better understand quality issues in education in terms of theoretical rigor as well as managerial relevance (Parast 2015; Parast and Golmohammadi 2019; Parast and Safari 2021, 2022). In addition, by using scores from independent reviewers (which is embedded in the quality assessment process of the Baldrige program), we ensure that the data is objective. This approach to quality assessment avoids the shortcomings of collecting data through self-administered surveys (Sofaer and Firminger 2005). In addition, the Baldrige data for education organizations spans seven years, thus providing a suitable basis for examining the relationships between quality practices over time. This provides important evidence for moving beyond correlations analysis and establishing causality. This approach will therefore improve both the theory and practice of quality management in the education domain.

Quality management in education

Defining quality and its management in education settings is a debatable issue. Some argue that the concept of quality and the interplay between different entities in educational settings is similar to that of manufacturing and other service enterprises, but the concept of quality and how it is defined clearly needs to be refined to fit the nature of education (Owlia and Aspinwall 1997). Some argue that there is no clear definition of what quality means in education (Brockerhoff et al. 2015). Educational organizations deal with multiple stakeholders, each with its own idea of quality (Schindler et al. 2015). Thus, what students perceive as high-quality education may differ from that of an employer or a funding agency (Dicker et al. 2019). In addition, concepts such as ethics and social responsibility should be emphasized in education settings to prepare students for their future roles in society (Harris et al. 2011). Quality assessment in education should therefore develop a holistic and systematic approach that incorporates all the complementary perspectives of quality (Goldberg and Cole 2002).

Quality, ethics, and social responsibility

From a solely economic perspective, organizations’ primary objective is to maximize their profits and shareholder value; thus, in a competitive business environment, business and ethics are not necessarily compatible (Ahmed and Machold 2004). While the relationship between quality, ethics, and social responsibility has been widely debated for the business environment, the relationship and its internal compatibility in the context of educational organizations needs further attention to address the needs and interests of the various stakeholders.

Quality management studies have long acknowledged the link between quality and ethics. Ishikawa (1985) alluded to this by articulating how quality control principles relate to believing in the goodness of people. This is reflected in the Kaizen quality management concept of a continuous improvement in the quality of life for individuals (Evans and Lindsay 1993). The literature suggests that adhering to quality management principles shapes corporate culture and encourages ethical leadership principles; this is reflected in the MBNQA (Steeples 1994). While there is a relationship between quality and ethics from a theoretical perspective (Chen et al. 1997; Raiborn and Payne 1996), numerous unethical practices are prevalent in the business world. Boisjoly (1993) argues that such unethical practices mostly result from cultural failures and shortcomings in management systems, so implementing a quality management system like the MBNQA may address this issue.

Several authors argue that a quality management system can address the ethical dimensions of management systems and the institutionalized ethical principles within organizations. Wicks and Freeman (1998) note that TQM principles address management practices while promoting moral values. What is needed is to broaden the concept of quality, which has happened in the quality management domain. Indeed, the concept of quality has evolved from statistical values for quality control and process improvement to considering more nuanced factors like customer satisfaction, employee engagement, and learning and innovation (Kok et al. 2001; Perdomo-Ortiz et al. 2009; Maletič et al. 2014; Psomas and Antony 2015). The recent trends toward sustainability and social responsibility have led to the quality management literature focusing more on the role of quality in improving an organization’s relationship with its stakeholders (Parast 2013, 2014; Wagner 2015). Organizations that implement quality management practices are more inclined to adhere to the principles and premises of social responsibility and ethical conduct, suggesting the existence of direct links between quality, ethics, and social responsibility (Erwin 2011; Attig and Cleary 2015). Thus, implementing quality management in educational organizations could not only lead to improvements in business processes and outcomes, it could also provide a suitable platform for addressing codes of conduct, ethical principles, and corporate social responsibility for the various stakeholders.

Studies of quality in educational organizations

Research into quality in education has been conducted from three perspectives. The first perspective, which is by far the most dominant, is concerned with theorizing and conceptualizing quality in education. This stream of research provides different directions and conceptualizations for quality in education and discusses the challenges associated with measuring it (Crawford and Shulter 1999; De Jager and Nieuwenhuis 2005; Becket and Brookes 2006; Sharabi 2013). The second perspective on quality in education is concerned with assessing customer satisfaction, which involves primarily looking at students’ perceptions of quality for an educational organization and its instruction. This is largely influenced by the literature on service quality, which generally measures quality on a multidimensional scale that evaluates a service from the customer’s (i.e., the student’s) viewpoint (Parasuraman et al. 1985, 1988). Although this branch of research provides important insight into the quality of service delivery and student satisfaction, it is primarily concerned with customer interaction and the delivery of services, so it does not capture the inherent nuances of quality in an education setting (Verma and Parasad 2017). This stream of research examines the dimensions of quality in education and the service sector from a student’s point of view, and it has found that students regard as valuable components of a quality education features such as courses offered and delivered, information management and responsiveness, collaboration and comparisons, internal audit assessment, IT equipment and infrastructure, and library resources (Lagrosen et al. 2004). Finally, the third perspective on quality in education deals with measuring quality in education and identifying important quality practices to enhance quality outcomes and business results in education settings (Asif et al. 2013). While these studies provide insights into quality issues by conducting surveys, they usually suffer from weak research design, a poor methodological approach, and a limited view of quality, all of which raise concerns about the validity and reliability of their findings. Our study is concerned with this third perspective on quality in education. We use the Baldrige model for quality to examine the relationship between quality management practices and an organization’s operational and business results. We assess the impact of quality management practices (leadership, management of process quality, information and analysis, human resources development and management, and strategic planning for quality) on customer focus and satisfaction and operational and business results, as shown in Fig. 1.

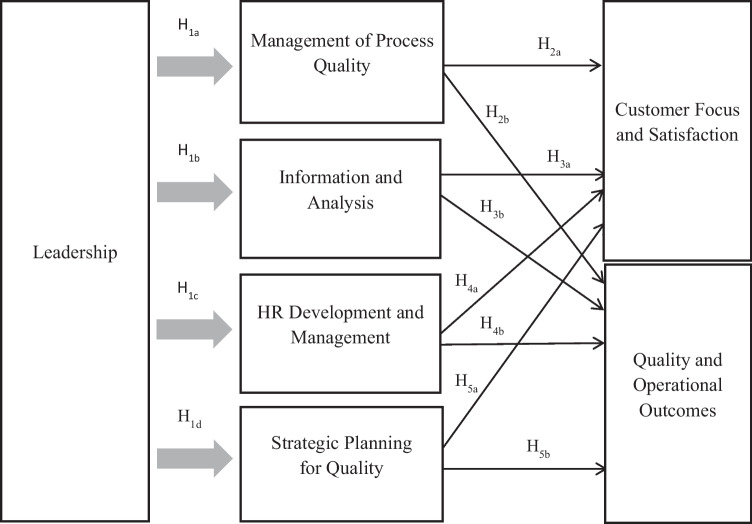

Fig. 1.

Structural Model/Framework for Quality Management in Educational Organizations (Adapted from Parast 2015)

Table 1 presents a review of studies concerned with quality management in educational organizations. Most of these studies are concerned with conceptual development and the articulation of definitions for quality in education (Crawford and Shulter 1999; De Jager and Nieuwenhuis 2005; Becket and Brookes 2006; Sharabi 2013), as well as some case studies (Michael et al. 1997; Mergen et al. 2000; Goldberg and Cole 2002). While some studies survey students (Aly and Akpovi 2001; Csizmadia et al. 2008), most of them sought to solicit information from different stakeholders (e.g., students, faculty, and staff) about quality, and the analyses are limited to providing descriptive statistics about key variables. These studies mainly do not follow a rigorous process of survey design, sampling strategy, and survey implementation. A similar criticism can be directed against the qualitative studies, which provide some limited knowledge about the cases being discussed (Michael et al. 1997; Newton 2002; Sadiq Sohail et al. 2003). Therefore, these studies are limited to the specific sample and context being examined.

Table 1.

Studies of Quality Management in Educational Organizations (in alphabetical order)

| Study | Research | Country | Baldrige | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ah-Teck and Starr (2013) | Survey | Mauritius | Yes | This study used the MBNQA principles/model to evaluate the performance of primary and secondary schools in Mauritius. They found that school leadership in Mauritius has direct and indirect impacts on outcomes through inner factors of the schools |

| Aly and Akpovi (2001) | Survey | U.S | No | Over half of California’s public universities apply quality management, but the scope of its implementation is limited to business finance and administrative services |

| Ardi et al. (2012) | Survey | Indonesia | No | Based on this study, faculty commitment, delivery quality, and effective processes for obtaining and improving quality significantly influence students’ satisfaction |

| Asif et al. (2013) | Survey | Pakistan | No | Based on their study, key elements of successful quality management in a higher-education environment are organizational vision, effective leadership, performance measurement and analysis, process management and control, resource allocation and program design, and effective stakeholder relationships |

| Badri et al. (2006) | Survey | UAE | Yes | They confirmed that leadership is a significant driver for all MBNQA elements, and all these elements are associated with organizational outcomes as well as the organization’s stakeholder focus, student focus, and market focus |

| Basari and Altinay (2018) | Interview | Cyprus | No | Their suggestions include prioritizing quality policies and concepts at a high level and in all units of an educational institution, while considering that equality in education and developing a quality consciousness and a strategic plan are important for higher education institutions |

| Becket and Brookes (2006) | Conceptual | U.K | No | Effective evolution and subsequent change management are crucial for executing quality enhancement |

| Brennan and Shah (2000) | Conceptual | Global | No | Questions about power and values are central points when establishing quality management. Quality management systems can therefore challenge the intrinsic value systems of an educational institution. Quality management is also an effective mechanism for considering and applying extrinsic values from society and the economy and incorporating them into education life with greater importance |

| Buranakul et al. (2017) | Survey | Thailand | Yes | Their study suggests that universities apply TQM to improve organizational capacity for innovation and to develop strategies for building a knowledge sharing environment as a positive driver of tacit knowledge and innovation capacity |

| Chin et al. (2003) | Survey | Hong Kong | Yes | They developed a self-assessment training toolkit to measure and evaluate organizational performance. The kit was designed based on MBNQA criteria for an engineering management curriculum |

| Crawford and Shulter (1999) | Conceptual | Global | No | There is a different understanding of TQM in education compared to TQM in industry. We may experience contradictory outcomes when we apply quality management in educational institutions because it may lead to the learning process focusing on good examination grades. This differs from the main concept of TQM because efforts at continuous improvement are relevant even to educational institutions, such as by improving the quality of instruction and developing students into more creative and critical thinkers |

| Csizmadia et al. (2008) | Survey | Hungary | No | The study states that in the Hungarian higher education system, these organizational characteristics are important in implementing quality management practices: leadership commitment and support, external consultants’ involvement, organizational reputation, and political and bureaucratic decision-making processes |

| De Jager and Nieuwenhuis (2005) | Conceptual | South Africa | No | The challenge is to successfully align the quality management concept with outcome-based education principles, to benefit from applying quality management solutions in higher education systems |

| Dicker et al. (2019) | Survey | U.K | No | The study confirms that employers look for high-quality personal traits in graduates. However, academic staff and students mostly focus on learning and teaching, feedback, and relationships. Students expressed uncertainty about the quality of the education they receive. The high-level administration teams of higher education organizations should highlight the value they deliver to their students/clients |

| Elmuti et al. (1996) |

Survey and Interview |

U.S | No | Continuous improvement can come from the main fundamentals of an effective quality management system: leadership commitment, customer orientation, employee engagement, quality-oriented vision, and effective benchmarking. In an education system, however, the university leadership and administration present the main challenge. While a great deal of time, effort, training, and resources should be allocated to implementing quality management, the top management teams in many higher education institutions are unable or unwilling to support such programs |

| Goldberg and Cole (2002) | Case study | U.S | No | Based on this study, by applying a cycle of planning, analyzing, and continuously improving, as well as using data from the education process, institutions can make informed decisions and determine areas of success and areas for improvement |

| Hoecht (2006) | Conceptual/interview | U.K | No | While accountability and transparency are well developed in academia, quality practices are very bureaucratic, with a high opportunity cost and usually only addressed on a superficial level |

| Jaraiedi and Ritz (1994) | Conceptual | U.S | No | While teaching is a crucial factor in the quality puzzle, a higher education institution should review its policies and practices to assess whether they really satisfy the needs of the institution's primary customers: the students |

| Johnson and Golomski (1999) | Conceptual | U.S | No | The study recommends applying quality management principles in an education curriculum, improving administration processes and business operations, reducing cycle times, enhancing learning and leadership, understanding and engaging stakeholders and other parties, and identifying opportunities for improvement |

| Kanji et al. (1999b) | Survey | Malaysia and U.S | No | Higher education needs to be guided through quality management and supported by the top management of the organization to enhance business performance. Leadership is therefore the most important factor. Higher education institutions that implement quality management outperform those that do not |

| Kanji et al. (1999a) | Survey | U.S | No | Measuring quality management and core concepts are considered critical success factors for higher education institutions to achieve business excellence |

| Koch and Fisher (1998) | Conceptual | U.S | No | There are limited empirical studies about quality management in educational organizations. Major quality issues at universities include the nature of the curriculum, effective collaboration with industry, and management and leadership arrangements |

| Lagrosen et al. (2004) | Survey |

Austria Sweden U.K |

No | This study examined the dimensions of higher education’s quality and service quality from the students’ perspective, highlighting information and responsiveness, courses offered, internal audits, computing and IT facilities, collaborations and comparisons, and library resources |

| Latif et al. (2019) | Survey | Pakistan | No | Six quality drivers in higher education services were identified: leadership, teaching, administration services, knowledge services, other activities, and continuous improvement |

| Lomas (2004) | Conceptual | U.K | No | Organizations should identify, train, and nurture transformational leaders and other human actors who are adept in leadership skills and HR management. Organizations may apply specific quality management practices, such as EFQM or TQM, to achieve business excellence |

| Mahajan et al. (2014) | Survey | India | No | Leadership is the most crucial factor, followed by organizational structure and practices. Most factors are interdependent, and they should be seen coherently when assessing their effects on students’ education |

| Mergen et al. (2000) | Case study | U.S | No | This study assessed and showed the impacts of quality on design, conformance, and performance as an effective quality management model in higher education |

| Michael et al. (1997) | Case study | U.S | No | Quality management and improvement in higher education begins at the higher levels of administration. Providing enough training for management and staff is crucial. There may be resistance from top management teams about relinquishing authority to empower staff. These organizations need to change their management behavior, too |

| Motwani and Kumar (1997) | Conceptual | U.S | No | Top management should be involved in understanding and developing an effective plan to successfully achieve quality management. The organizational administration should conduct an internal quality assessment to determine strengths and weaknesses, obtain opinions and feedback from internal and external customers to assess its current state and identify improvement opportunities, and recognize and reward any quality improvements |

| Newton (2002) | Case study | U.K | No | By stressing autonomy, ownership, and self-assessment, an assurance system for quality management helps organization leadership in higher education to understand problems and the risk of exacerbating or exposing them. To conduct change in quality management, top leadership and management teams should assess the status of operations and their emerging trends |

|

O’Mahony and Garavan (2012) |

Case study | Ireland | No | Four key parameters are involved in implementing effective quality management in higher education institutions: senior leadership sponsorship and support, stakeholder involvement, execution of quality practices, and management of cultural change |

| Osseo-Asare and Longbottom (2002) | Case study | U.K | No | This study highlights the importance of staff development strategies for deans, assistant deans, and other staff involved in quality and operational improvement. The strategies should be based on integrating the EFQM model and the U.K. Quality Assurance Agency model. This study suggests comparing the EFQM and MBNQA models for education criteria |

| Owlia and Aspinwall (1997) | Case study | Global | No | From a theoretical perspective, the most critical principle of quality management in universities is customer orientation, because the motivation for academia does not usually depend on market issues. Based on this study’s analysis, the type of activities in educational institutions do not differ from those of manufacturing or other service enterprises. This study demonstrates the importance of several factors: morality among students and stuff, a high level of productivity, and customer focus and satisfaction |

| Psomas and Antony (2017) | Survey | Greece | No | Quality management practices in the Greek higher education system reveal the following concerns: leadership support and commitment, strategic plan for quality, student focus, process management, teaching team, employee engagement, and positive impacts on society |

| Sahney et al. (2004) | Conceptual | Global | No | This study viewed the input quality of educational institutions through the students, teachers, supporting staff, infrastructure, and the process quality of institutions in the form of its teaching and learning activities. Output quality was viewed in terms of the graduating students leaving the institution. This study also treats an educational institution or system as a transformational process that converts unskilled students into competent ones. In this system, the outputs include examination outcomes, employment, earnings, and satisfaction |

| Sahney et al. (2008) | Survey | India | No | Employee satisfaction is the main determinant for adopting an effective “customer-centric philosophy.” |

| Sarrico and Rosa (2016) | Case study | Portugal | No | The main challenges in supply chain quality management in the education sector relate to trust, sharing information, leadership, and integration. There is also a problem in supply chain integration. Developing SCQM models for this sector may aid this integration and lead to performance improvements |

| Sharabi (2013) | Conceptual | –- | No | In education institutions, the service quality delivered to students by the employees in contact with them is highly related to the top management and various departments of the educational institution |

| Sadiq Sohail et al. (2003) | Case study | Malaysia | No | Quality management practices encourage educational institutions to collect data, measure their performance, establish standards, benchmark, and make effective decisions |

|

Srikanthan and Dalrymple (2004) |

Conceptual | –- | No | Developing an effective quality system in education requires transforming it into a learning organization with quality monitoring for learning. Higher education institutions need to develop a vison to guide their actions. Student learning should be the main measure of academic quality, and customer responsiveness needs to be practiced and emphasized |

| Stahl (2004) | Conceptual | –- | No | Both e-teaching and information technology application in teaching may morally threaten the legitimacy of the education process. Strong association between teaching and business interests is one of the main reasons for this issue |

| Thakkar et al. (2006) | Case study | India | No | This study highlights the importance of continuous improvement, cultural improvement, and the optimal use of financial resources to improve service value at all levels |

| Tsinidou et al. (2010) | Survey | Greece | No | Quality of education is studied from the perspective of students. Based on the students’ outcomes, students’ success in the market can be improved by higher quality of teaching, effective library services, skilled employees, and the development of more specialized subjects. Such results also increase the interaction between a university and society |

| Venkatraman (2007) | Conceptual | New Zeeland | No | This study developed a quality management model for higher education that covers leadership, HR management, education management, information management, customer orientation and satisfaction, and partnership |

| Verma and Parasad (2017) | Survey | India | No | This study discusses service quality from a multi-dimensional construct with variables for six aspects: professional, academic, behavioral, industry interaction, physical, and non-academic. The results show internal consistency across the samples |

| Vesper and Gartner (1997) | Survey | U.S., Canada, and others | Yes | They ranked entrepreneurship programs based on seven criteria: courses offered, faculty publications, impact on the community, alumni accomplishments, innovations, alumni startups, and outreach to scholars. They also applied the seven MBNQA criteria to the quality of their programs |

| Voss et al. (2005) | Survey | U.S | No | In both private and public enterprises, progressive HR management leads to greater employee satisfaction, which consequently improves service quality and customer satisfaction. Research shows that HR practices have more impact on these elements than quality practices |

| Williams (1993) | Conceptual | –- | No | To have effective and efficient educational institutions, we need to focus on consistent quality services, continuous improvement, customer satisfaction, and a system for recognizing poor quality and correcting it |

| Willis and Taylor (1999) | Survey | U.S | No | From the employers’ perspective of business school graduates, communication skills and work ethics are the main weaknesses, while IT skills are the main strength. The lack of patience and commitment is another issue that business schools should consider to improve quality outcomes, although some employers asserted that certain schools produce superior graduates |

There have been several calls to use well-established quality models like the Baldrige or EFQM models in education settings (Osseo-Asare and Longbottom 2002; Lomas 2004). The studies that used the Baldrige model have collected data using surveys, which solicit the opinions of managers or key stakeholders. These studies targeted primary/secondary schools (Ah-Teck and Starr 2013) or universities/colleges (Vesper and Gartner 1997; Badri et al. 2006; Chin; Buranakul et al. 2017). Ah-Teck and Starr (2013) used MBNQA criteria to conduct a survey and assess the performance of primary and secondary schools in Mauritius. Vesper and Gartner (1997) used MBNQA criteria to assess entrepreneurship programs in the U.S., Canada, and overseas. Badri et al. (2006) used MBNQA criteria to conduct a survey among universities and colleges in UAE. Buranakul et al. (2017) used TQM methods, MBNQA criteria, and survey data to assess TQM impacts on the innovation capabilities of private universities in Thailand. In Hong Kong, Chin et al. (2003) used MBNQA principles to develop a performance toolkit for teaching courses and evaluating performance; they used a survey for their validation phase.

While these studies provide insights into quality management in the education domain, they do not provide a comprehensive assessment of quality management that is grounded in the theory and practice of quality management. Thus, we see a gap in using quality management frameworks such as the Baldrige model in the context of educational organizations. In addition, we could not find any comprehensive study that examined the relationship between quality management practices and operational and business outcomes in educational organizations from a longitudinal aspect. A longitudinal aspect is important, since it provides insight into ways that quality management practices can improve organizational quality outcomes over time and the potential invariance of these relationships over time. Thus, we provide a more nuanced assessment of quality management in educational organizations that examines quality using the Baldrige criteria. Using such a well-rounded framework for quality management provides more insight into the management of quality in educational organizations.

Theory development and research hypotheses

To examine the impact of quality management on quality and operational outcomes in educational organizations, we applied the MBNQA criteria. Previous studies about these criteria have confirmed the relation between leadership and other MBNQA model components (Pannirselvam et al. 1998; Wilson and Collier 2000; Pannirselvam and Ferguson 2001; Parast 2015). Empirical analyses of the MBNQA data show that leadership is a key quality driver because it impacts strategic quality management, information and knowledge management, process quality management, and HR development and management. In the MBQNA program, leadership is the key construct reflecting senior management’s responsibilities and efforts to apply effective leadership practices to cultivate motivation and teamwork, thus building a culture with a high level of trust and creating a successful organization for the near term and the long term. These practices collectively bring about quality and operational outcomes as well as customer orientation and satisfaction. This study examines the relationships among the elements in the MBNQA framework (see Fig. 1 below) and tests the hypotheses using objective data for educational organizations. Table 2 shows our research hypotheses developed in this study and provides a summary of the literature that supports the hypotheses developed in this study.

Table 2.

Hypotheses for MBNQA in Educational Organizations

| Hypothesis | Justification |

|---|---|

| H1a: In education organizations, leadership positively influences the management of process quality | Based on the Baldrige model, leadership directly affects process quality. Wilson and Collier (2000), Meyer and Collier (2001), Pannirselvam and Ferguson (2001), and Parast and Golmohammadi (2019) confirmed that quality leadership is significantly related to management of process quality. Elmuti et al. (1996), Kanji et al. (1999b), Csizmadia et al. (2008), and Mahajan et al. (2014) found that leadership support and commitment is the key factor in effective implementation of quality management |

| H1b: In education organizations, leadership positively influences information and knowledge management | Based on the Baldrige model, leadership directly affects information and analysis. Wilson and Collier (2000), Meyer and Collier (2001), and Parast and Golmohammadi (2019) showed that quality leadership is significantly related to information and knowledge management. Elmuti et al. (1996), Kanji et al. (1999b), Csizmadia et al. (2008), and Mahajan et al. (2014) found that leadership support and commitment is the key factor in effective implementation of quality management |

| H1c: In education organizations, leadership positively influences HR development and management | Based on the Baldrige model, leadership directly affects human resource development and management. Wilson and Collier (2000), Meyer and Collier (2001), Pannirselvam and Ferguson (2001), and Parast and Golmohammadi (2019) confirmed that quality leadership is significantly related to human resource development and management. Elmuti et al. (1996), Kanji et al. (1999b), Csizmadia et al. (2008), and Mahajan et al. (2014) argued that leadership support and commitment is the key factor in effective implementation of quality management |

| H1d: In education organizations, leadership positively influences strategic planning for quality | Based on the Baldrige model, leadership directly affects strategic quality planning. Wilson and Collier (2000) and Parast and Golmohammadi (2019) confirmed that quality leadership is significantly related to strategic planning for quality. Elmuti et al. (1996), Kanji et al. (1999b), Csizmadia et al. (2008), and Mahajan et al. (2014) found that leadership support and commitment is the key factor in effective implementation of quality management |

| H2a: In education organizations, management of process quality positively influences customer focus and satisfaction | Wilson and Collier (2000), Meyer and Collier (2001), and Pannirselvam and Ferguson (2001) confirmed that management of process quality is significantly related to customer focus and satisfaction. Research shows that process factors are closely related to service quality and customer satisfaction (Dabholkar and Overby 2005). Asif et al. (2013) discussed that process management is a key element of a successful quality system. Improving process quality was shown to have a positive impact on customers (students) in educational organizations (Ardi et al. 2012) |

| H2b: In education organizations, management of process quality positively influences quality and operational outcomes | Wilson and Collier (2000) and Pannirselvam and Ferguson (2001) confirmed that management of process quality is significantly associated with quality and operational outcomes. Asif et al. (2013) found that process management is a key element of successful quality systems. Thakkar et al. (2006) highlight the importance of continuous improvement, cultural improvement, and the optimal use of financial resources to improve service value at all levels |

| H3a: In education organizations, information and knowledge management positively influences customer focus and satisfaction | Wilson and Collier (2000) and Pannirselvam and Ferguson (2001) confirmed that information and knowledge management is significantly associated with customer focus and satisfaction. Asif et al. (2013) found that information and knowledge management is a key element of a successful quality system. Seeman and O’Hara (2006) discussed the important role of information systems in promoting the student-school relationship |

| H3b: In education organizations, information and knowledge management positively influences quality and operational outcomes | Meyer and Collier (2001) and Parast and Golmohammadi (2019) confirmed that information and knowledge management is significantly associated with quality and operational outcomes. Chavez et al. (2015) showed that information quality mediates the relationship between customer integration and operational performance. Asif et al. (2013) discussed that information and knowledge management is a key element of successful quality systems |

| H4a: In education organizations, HR development and management positively influences customer focus and satisfaction | Wilson and Collier (2000), Pannirselvam and Ferguson (2001), and Parast and Golmohammadi (2019) confirmed that human resource management is significantly associated with customer focus and satisfaction. According to Tsinidou et al. (2010), skilled employees have a positive impact on quality outcomes. Employee satisfaction is the main determinant for adopting an effective “customer-centric philosophy” (Sahney et al. 2008). Voss et al. (2005) argue that HR practices have a significant impact on quality outcomes |

| H4b: In education organizations, HR development and management positively influences quality and operational outcomes | Wilson and Collier (2000), Pannirselvam and Ferguson (2001), and Parast and Golmohammadi (2019) confirmed that human resource management is significantly associated with quality and operational outcomes. According to Tsinidou et al. (2010), skilled employees have a positive impact on quality outcomes in educational organizations. Voss et al. (2005) found that HR practices have a significant impact on quality outcomes |

| H5a: In education organizations, strategic planning for quality positively influences customer focus and satisfaction | Wilson and Collier (2000), Meyer and Collier (2001), and Parast and Golmohammadi (2019) confirmed that strategic planning for quality is significantly associated with customer focus and satisfaction. Fooladvand et al. (2015) discuss the important role of strategic planning in improving quality outcomes in educational organizations. According to Tsiakkiros and Pashiardis (2002), strategic planning is critical to achieving organizational goals and long-term survival |

| H5b: In education organizations, strategic planning for quality positively influences quality and operational outcomes | Wilson and Collier (2000) confirmed that strategic planning for quality is significantly associated with quality and operational outcomes. Fooladvand et al. (2015) discuss the important role of strategic planning for quality in improving quality outcomes in educational organizations. Tsiakkiros and Pashiardis (2002) found that strategic planning in educational organizations is critical to achieving organizational goals and long-term survival |

Methodology

This study uses the MBNQA (Baldrige) model and its criteria for quality management, which are the same criteria that were used when collecting the data. These are the criteria: 1) Leadership; 2) Strategic Planning for Quality; 3) Customer Focus and Satisfaction; 4) Information and Knowledge Management; 5) HR Development and Management; 6) Management of Process Quality; and 7) Quality and Operational Outcomes (NIST 2020). An overview of each criterion follows.

Leadership

This key aspect reflects senior management’s responsibilities and efforts to apply effective leadership practices to cultivate motivation and teamwork, thus building a culture with a high level of trust and creating a successful organization for the near term and the long term.

Strategic planning for quality

This reflects an organization’s strategic goals and objectives, its long-term and short-term plans, its action plan, how it measures progress, and how it changes plans when necessary.

Customer focus and satisfaction

This component of quality management relates to how an educational organization engages with its students and other customers. This involves ensuring students’ success but also listening to their voices, so their expectations are addressed and an effective relationship with them is built. This component therefore emphasizes customer engagement and satisfaction as a critical element of effective learning and education performance. In addition to students, there are other important customers such as parents, local businesses, other educational organizations that may receive the students later, and potential employers of the students. A major challenge for educational organizations is finding a balance between the different expectations of students (as the primary customer) and these other stakeholders.

Information and knowledge management

This is considered the core component for aligning operations with strategic goals and objectives. The criteria for education cover the main information for understanding, measuring, evaluating, and improving an educational organization’s performance and knowledge management in order to enhance innovation and competitiveness.

HR development and management

This addresses workforce practices in educational organizations, including the persons who create value and those who support them in doing so, such as teachers, trainers, administrators, and the management team.

Management of process quality

This focuses on educational organizations’ processes and activities, program types, service design and delivery methods, innovation, and operational effectiveness plans and practices for the near term present and long term.

Quality and operational outcomes

This focuses on the results and outcomes that are necessary for sustaining or growing an educational organization, including the results of educational processes, student learning, leadership and governance, workforce outcomes, satisfaction, financial outcomes, and marketing performance.

Data

The required data for each educational organization were collected as part of the MBNQA program. These data consist of 115 organizational scores for educational organizations in the U.S. over a seven-year period from 1999 to 2006, but any given educational organization may not appear in all seven years. Due to the robustness, soundness, and objectivity of the evaluation process, the data are highly reliable (Parast 2015; Parast and Golmohammadi 2019; Parast and Safari 2021, 2022).

Sample

This study’s sample is the data from U.S. educational organizations that applied for the MBNQA award between 1999 and 2006. The data for 1999 were excluded from our analysis, since 1999 was the first year of such data collection. In total, there are 115 observations for the 1999–2006 period.

Table 3 presents a summary of the data for each criterion for each year (mean and standard deviation). The first column gives the year and (in parentheses) the sample size for that year. To examine the normality of our dataset, we needed to estimate the skewness (asymmetry) as well as kurtosis (peakedness) of the dataset. Our estimates for both asymmetry and kurtosis fell between -0.851 and 0.302, which are both within the acceptable range of -1.5 to + 1.5. This demonstrates that our dataset has normal univariate behavior (Tabachnick and Fidell 2013) and meets the requirement of normality.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics

| Year | Leadership | Strategic Planning for Quality | Customer Focus and Satisfaction | Information and Knowledge Management | HR Development and Management |

Management of Process Quality | Quality and Operational Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 (16) | (.43, .16) | (.38, .15) | (.40, .12) | (.36, .15) | (.39, .14) | (.42, .12) | (.35, .16) |

| 2000 (11) | (.48, .09) | (.42, .13) | (.41, .09) | (.41, .14) | (.42, .09) | (.43, .14) | (.36, .15) |

| 2001 (10) | (.48, .12) | (.44, .15) | (.43, .12) | (.48, .14) | (.43, .11) | (.43, .11) | (.37, .18) |

| 2002 (10) | (.35, .10) | (.32, .10) | (.35, .10) | (.35, .13) | (.35, .07) | (.36, .07) | (.29, .08) |

| 2003 (19) | (.40, .13) | (.33, .12) | (.38, .12) | (.40, .12) | (.38, .08) | (.37, .11) | (.29, .14) |

| 2004 (17) | (.54, .10) | (.42, .13) | (.44, .11) | (.46, .13) | (.45, .06) | (.45, .12) | (.36, .10) |

| 2005 (16) | (.49, .12) | (.43, .13) | (.46, 11) | (.48, .11) | (.47, .12) | (.47, .13) | (.39, .13) |

| 2006 (16) | (.53, .09) | (.51, .11) | (.53, .09) | (.51, .11) | (.52, .11) | (.53, .12) | (.42, .13) |

Table 3 shows that there were significant improvements in the mean value for most criteria (constructs) over the seven years from 1999 to 2006, which could be a result of the widespread application of quality practices. For instance, the Leadership score improved from 0.43 to 0.53 (+ 23%) during this seven-year period. The improvement in the Leadership score can be attributed to the fact that different educational organizations, more advanced in quality management, applied in the later years. We can see similar improvement patterns for other MBNQA constructs: Strategic Planning for Quality increased from 0.38 to 0.51 (34.2%), Customer Focus and Satisfaction increased from 0.40 to 0.53 (32.5%), Information and Knowledge Management increased from 0.36 to 0.5 (41.7%), HR Development and Management increased from 0.39 to 0.52 (33.3%), and Management of Process Quality increased from 0.42 to 0.53 (26.2%), and most importantly, Quality and Operational Outcomes increased from 0.35 to 0.42 (20%) as our main output. While we have seen declines in quality and operational results in other segments such as healthcare (Parast and Golmohammadi 2019), the overall improvement in the education sector is quite significant.

Table 4 presents the overall mean, standard deviation (SD), and pairwise correlation of the MBNQA criteria. It shows that the scores for quality management constructs in these educational organizations range from 0.36 to 0.45 (out of 1), implying that there is a significant shortfall in effectively applying quality management practices in these organizations. Furthermore, these constructs are highly correlated, which reflects the considerable interrelationships among the MBNQA model elements that were supported and envisioned in the literature.

Table 4.

Overall Attributes and Pairwise Correlation of Criteria (Constructs)

| Mean | S.D | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Leadership | .45 | .13 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 2. Strategic planning for quality | .41 | .14 | .842*** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 3. Customer focus and satisfaction | .43 | .12 | .863*** | .840*** | 1.00 | |||||

| 4. Information and analysis | .43 | .14 | .822*** | .853*** | .851*** | 1.00 | ||||

| 5. HR development and management | .43 | .11 | .842*** | .808*** | .832*** | .802*** | 1.00 | |||

| 6. Process management for quality | .44 | .13 | .824*** | .820*** | .817*** | .837*** | .812*** | 1.00 | ||

| 7. Quality and operational outcomes | .36 | .14 | .777*** | .809*** | .767*** | .779*** | .749*** | .800*** | 1.00 | |

***p < .01

Data analysis and estimation procedure

In this study, we applied the structural equation modeling (SEM) approach for our analysis. SEM allows the analysis and testing of complex associations among various independent and dependent variables simultaneously, so there can be more than one output variable. Additionally, SEM can be regarded as effectively combining both factor analysis and regression analysis to analyze the structural associations among observed and latent variables (Bagozzi and Yi 2012).

Measurement model—validation and analysis

To verify our SEM analysis and examine the overall fitness of our MBNQA model for educational organizations, we used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), because, as stressed by Hair et al. (2009), CFA is an important method for full model measurement. Our CFA goodness-of-fit statistic showed the overall fitness of the model to be (χ2/df = 1.17, RMSEA = 0.038 (0.01, 0.065); RMR = 0.001). Based on this result, all the key parameters of Chi-Square, RMSEA, and RMR fall within the respective acceptable and recommended ranges (Hu and Bentler 1999). In addition, we applied the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin method of sampling adequacy to evaluate the validity of the factor model (Kärnä et al. 2003). We received a result of KMO = 0.96 and χ2 = 2201.24 with p < 0.01, which suggests there are no concerns regarding the factor model.

Next, we estimated the reliability for our main constructs using Cronbach’s alpha. These values were also found to be within the recommended range (between 0.84 and 0.93). A reliability value greater than or equal to 0.7 is acceptable for survey study (Hair et al. 2009). As Table 5 shows, our estimation of the standardized loadings for the model are all significant, thus proving the convergent validity of the model. Additionally, we tested composite reliabilities and average variance extracted (AVE) to ensure convergent validity and discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981; Agarwal 2013; Henseler et al. 2015). The “Item” column lists each sub-construct used in our analysis. Descriptions of the entries in this column are provided in Appendix A.

Table 5.

Properties of the Constructs and Model

| Scale | Measurements | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reliability | Composite reliability | Item (Sub-construct) |

Loading | Average Variance Extracted | |

| Leadership | .87 | .95 | L11 | .94 | .92 |

| L12 | .89 | ||||

| Strategic Planning for Quality | .93 | .93 | S21 | .96 | .89 |

| S22 | .95 | ||||

| Customer Focus and Satisfaction | .90 | .93 | C31 | .90 | .89 |

| C32 | .87 | ||||

| Information and Analysis | .89 | .96 | I41 | .95 | .93 |

| I42 | .91 | ||||

|

HR Development and Management |

.89 | .97 | H51 | .87 | .88 |

| H52 | .93 | ||||

| H53 | .85 | ||||

| Process Management | .87 | .97 | P61 | .92 | .92 |

| P62 | .91 | ||||

| Quality and Operational Results | .93 | .98 | Q71 | .87 | .68 |

| Q72 | .95 | ||||

| Q73 | .90 | ||||

| Q74 | .88 | ||||

Structural Model and the Testing of Hypotheses

Control variables

There are two control variables, namely for industry (i.e., educational organizations) and application year. We assigned a vector of dummy variables for each year (Y1999 through Y2006), applying 1999 as the reference year.

Statistical procedure

As indicated earlier, to assess the validity of the conceptual framework as shown in Fig. 1, we applied the SEM approach using AMOS 25.0 software. Table 6 shows the outcome of this analysis: the regression coefficients and corresponding p-value for each path. These results are consistent with the main hypotheses H1a through H1d. They show that Leadership significantly and positively influences the following variables: Management of Process Quality (ß = 0.975, p < 0.05), Information and analysis (ß = 0.991, p < 0.05), HR development and managementt (ß = 0.917, p < 0.05), and Strategic quality planning (ß = 0.957, p < 0.05). Information and analysis significantly and positively influences Customer focus and satisfaction (ß = 1.861, p < 0.05) (H3a). Management of process quality is a significant predictor for Quality and operational results (ß = 0.615, p < 0.10) (H2b). The details of all these relations are presented in Table 6. We were not able to find support for hypotheses H2a, H3b, H4a, H4b, H5a and H5b.

Table 6.

Coefficients

| Controls | Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer focus and satisfaction | Quality and operations results | Strategic quality planning | Information and analysis |

HR development and management | Management of process quality | |

| Y2000 | -.178* | .053 | .015 | .036 | .042 | -.111* |

| Y2001 | -.392** | .053 | .043 | .199** | .068 | -.086 |

| Y2002 | -220* | .046 | .075 | .210** | .096 | .063 |

| Y2003 | -.423** | .024 | -.034 | .237** | .083 | -.051 |

| Y2004 | -.319** | -.019 | .090* | .292** | .225* | .085 |

| Y2005 | -.331** | .011 | .001 | .208** | .141* | .006 |

| Y2006 | -.113 | -.078 | .109** | .192** | .225* | .058 |

| Predictors | Customer focus and satisfaction | Quality and operations results | Strategic quality planning |

Information and analysis |

HR Development | Management of process quality |

| Leadership | n.s | n.s | .957** | .991** | .917** | .975** |

| Strategic quality planning | -.261 | .338 | ||||

| Information and analysis | 1.861** | .013 | ||||

| HR Development | -.023 | -.034 | ||||

| Management of process quality | -.578 | .615* | ||||

n.s. hypothesis is not stated

*p ≤ .10; * p ≤ .05 **

Robustness and validation tests

Normality test

Even though the normality assumption in data is necessary for regression analysis, it is not required for the SEM approach (Sharma et al. 1989; Lei and Lomax 2005). We applied the skewness and kurtosis measures to examine data symmetry and peakedness, which were found to be in the range of -0.702 to 0.238. Thus, we concluded that normality assumptions for the data were met.

Heteroscedasticity test

To ensure that we obtained unbiased estimates, a heteroscedasticity test was needed. Heteroscedasticity reflects the situation that the regression variance disturbances (or the variance of error terms) is not constant across observations (Greene 2012). We plotted predicted values vs. residuals and found no evidence of heteroscedasticity in the dataset.

Multicollinearity test

The multicollinearity test concerns the insensitivity of the results to interrelationships or correlations among variables. Based on our analysis, all the variable inflation factor (VIF) values estimated by our multiple regression analysis were below the recommended value (10), since the highest VIF value was 4.6. This means that there was no major concern about multicollinearity in the dataset (Belsley et al. 1980; Hair et al. 2009).

Alternative structural models

We evaluated whether the alternative structural models proposed in the literature would significantly improve the model’s fit. An alternative structural model proposed for the MBNQA suggests a mediating relationship between Information and Analysis and other quality management practices (Wilson and Collier 2000). This alternative model shows model fit statistics of χ2/df = 1.983, RMSEA = 0.093; RMR = 0.004; CFI = 0.922. This is not significantly different from the structural model proposed in this study (χ2/df = 1.94, RMSEA = 0.091; RMR = 0.004; CFI = 0.924). The second alternative model, which was proposed by Flynn and Saladin (2001), introduces three more paths in addition to the model proposed by Wilson and Collier (2000): a path from Customer orientation and focus to Process management, a path from HR development to Process management, and a path from Strategic planning to HR development. This structural model gives fit statistics of χ2/df = 1.983, RMSEA = 0.093; RMR = 0.004; CFI = 0.922. Again, this was not significantly different from the structural model proposed in this study. We also realized that these two alterative models were primarily developed and verified in manufacturing settings, where only Quality and operational results is considered for the outcome. Our empirical results, along with the nature of the educational organizations, suggest that the model proposed in this study considers both customer focus and quality results as outcomes for a quality system, so it is a suitable model for quality management and business excellence in educational settings.

Discussion

This study provides the first comprehensive, data-driven, and empirically sound assessment of quality management practices for educational organizations. In addition to providing a suitable theoretical and conceptual framework for assessing quality management in education settings, this study uses assessments from independent reviewers for quality practices to yield a high level of reliability and validity for the data, thus ensuring the robustness of the results and findings. Furthermore, the longitudinal nature of the data, which covers quality practices over a seven-year period, captures the nuances related to the association between quality management practices and quality results over time, thereby increasing the robustness of the results when compared to cross-sectional surveys that are administered at just a given point in time. This means that the relationships go beyond simple correlations and there is a stronger case for causality.

Theoretical contributions

This research makes several contributions to the literature in the field of operations management, quality management, informing public policy, and governance practices at educational organizations. First, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first empirical assessment of the use of a well-established quality management model in educational organizations. Our findings suggest that quality management models like the MBNQA framework are compatible with educational organizations and can be used to enhance quality outcomes and achieve business excellence.

Second, this study builds upon the relatively dispersed previous research into quality management in educational settings, and it further advances our understanding of how quality management practices, which were developed primarily for production and manufacturing systems, can improve quality results in education settings (Elmuti et al. 1996; Kanji et al. 1999b; De Jager and Nieuwenhuis 2005). Using high-quality data from educational organizations, we have provided an early but comprehensive assessment of quality management in educational settings. This effort addresses two main gaps in the current literature by 1) using independent professional reviewers’ scores, which are objective and reliable, and 2) using seven years of data for educational organizations, thus enabling a more rigorous evaluation of the associations between quality management practices and quality and operational outcomes. The robustness of the MBNQA model and the quality of the data ensure the validity of the results.

Third, our research improves our understanding of how educational organizations can enhance their business operations and quality by applying the MBNQA model. Consistent with prior anecdotal evidence for quality management practices in educational organizations (Elmuti et al. 1996; Csizmadia et al. 2008; Asif et al. 2013), our findings show that Leadership is the key driver of quality management practices in educational organizations, which in turn significantly influence all other quality management elements. This supports prior studies that have suggested an interdependence among quality practices in educational organizations (Mahajan et al. 2014). We examined the Leadership effects from two perspectives. First, Leadership directly and positively impacts other constructs of the model, including Information and analysis, Strategic planning for quality, HR development and management, and Quality process management. This outcome affirms the Baldrige theory that Leadership drives systems, and this outcome also supports previous studies that have articulated how the strong commitment and sponsorship of the senior leadership team is a key driver of quality improvement (Psomas and Antony 2017). It also supports the anecdotal evidence that a university’s top administration presents the main obstacle to implementing a quality management system (Elmuti et al. 1996). Leadership also significantly influences Strategic planning (ß = 0.957, p < 0.05), and this is one of the greatest impacts among the MBNQA criteria. This suggests that in educational organizations, leaders must recognize the importance of long-term strategies for quality; this also supports former studies that have emphasized the crucial role of strategic planning and development as an important factor in the successful implementation of quality management in educational organizations (Osseo-Asare and Longbottom 2002; Basari and Altinay 2018).

Our fourth contribution concerns the significant impact of Process quality management on Quality and operational results (ß = 0.615, p < 0.1). Studies have well discussed the challenges related to process management and process improvement in service organizations (Ettlie and Rosenthal 2011); however, this study found that Management of process quality significantly affects quality and operational results in educational organizations. Studies confirm that applying a process approach to quality improvement (e.g., Lean and Six Sigma) leads to significant improvement in business processes and their outcomes (Assarlind and Gremyr 2016). Our findings support the recommendation put forward in the literature about the important role of process management and process improvement, as well as decision-making processes, in educational organizations (Asif et al. 2013; Goldberg and Cole 2002; Csizmadia et al. 2008). Our results also support the efforts of Zhao et al. (2008) as well as Harris et al. (2011), who showed the importance of process management in a successful implementation of quality management. Our findings extend that effect of process management to educational organizations.

The sixth contribution of this study is about the significant association between Information and knowledge management and Customer focus and satisfaction in educational organizations (ß = 1.861, p < 0.05). This has by far the largest coefficient among quality management and quality outcomes in educational organizations. The important role of information, analysis and knowledge management has been extensively discussed in the literature (Lagrosen et al. 2004; Venkatraman 2007; Sarrico and Rosa 2016), but empirical evidence for the effect of information and knowledge management on improving quality results in educational organizations had thus far been overlooked. Studies of the relationship between investment in information systems and customer satisfaction have also yielded mixed findings in business settings (Mithas et al. 2016). Our empirical results support the previous studies that have highlighted the importance of information systems and knowledge sharing for enhancing organizational performance in a business (i.e., profit-driven) setting (Lloyd-Walker and Cheung 1998; Demirbag et al. 2012). Information analysis, and knowledge management is an engine for quality improvement in educational organizations, and it is a key driver for continuous improvement and the transition to a learning organization in educational organizations (Goldberg and Cole 2002; Srikanthan and Dalrymple 2003).

Finally, our findings provide further important knowledge about the long-term effects of quality management solutions on educational organizations. While the literature expresses mixed opinions concerning the effectiveness of quality management programs (e.g., Asif et al. 2009; Bourke and Raper 2017), we tried to shed more light on the long-term impact of quality management programs on educational organizations. By reviewing the effects for each year and comparing them with our reference year (1999), we could provide valuable insight into this effect for service organizations. Reviewing the coefficients for Customer focus and satisfaction for the year-effect (see Table 6), we found a negative trend from 2000 (ß = -0.178, p < 0.1) to 2005 (ß = -0.331, p < 0.05). This suggests that compared with 1999, there was a decline in customer focus and satisfaction over time. This implies that, on average, the educational organizations were not able to address the needs and interests of their customers over time, hence the declining trend. In contrast, we can see significant improvements in Information and Analysis, where the year-effect shows a positive trend from 2001 (ß = 0.199, p < 0.05) to 2006 (ß = 0.192, p < 0.05). This demonstrates that while implementing quality management in educational organizations improves Information and analysis, it does not necessarily lead to a sustained improvement in Customer focus and satisfaction. The theoretical contribution of these observations is that it suggests diminishing returns on investment, in terms of customer focus practices, from information and knowledge management over time. This accords with the diminishing public trust in educational organizations (Salisbury and Horn 2019). It also provides an interesting observation for explaining the mixed results for the effectiveness of quality management programs, because this temporal effect cannot be captured with cross-sectional surveys. In addition, solely relying on the use of information technologies and information systems does not necessarily lead to better customer satisfaction. The information and analysis need to be incorporated into the development of new processes and reflected in organizational practices in order to address customers’ needs and interests and achieve a sustainable level of customer service quality. If they are not, the effect will be limited, and the information and analysis will not lead to process improvements or changes in organizational practices. Thus, educational organizations need to be aware that simply investing in information systems, library resources, and other informative and educational resources do not necessarily lead to better quality results, especially if input from multiple stakeholders is not incorporated into the design of information systems and improvements for organizational processes.

Implications for education administrators

This empirical study offers suggestions and insights for the administrators of educational organizations. First, as higher education organizations begin to refine their quality initiatives, they can consider using the MBNQA framework and criteria to diagnose their defects and issues and to analyze, restructure, and streamline their business processes, systems, and quality-improvement efforts. When service organizations are committed to enhancing their businesses and operational results, the Baldrige model is an effective and comprehensive approach for assessment. In addition, educational organizations should recognize the crucial role of investment in Information and knowledge management to fulfil their customers’ needs and consider their customers’ opinions in services. Education organizations interact with multiple stakeholders and engage with a variety of customers, so attention must be paid to developing information systems and investing in enterprise information systems that can capture data from multiple stakeholders and incorporate them into organizational processes, because this will be critical for an educational organization’s success. During the COVID-19 pandemic, educational organizations that had invested in information technology, support systems, and other related infrastructure were able to mitigate the impact of the pandemic and transition more smoothly to a virtual learning environment, thus minimizing the impact on student learning.

Education administrators should also consider the crucial role of process management in their business operation. Most business improvement approaches (e.g., TQM, ISO 9000, Kaizen, Lean, and Six Sigma) focus on business processes and continuous improvement to enhance organizational outcomes such as customer satisfaction and quality and operational results. Administrators also need to pay more attention to investing in information systems, analytics, and organizational learning to improve their informed decision making, to enhance their service operations and customer satisfaction using data-driven approaches. Finally, to improve service quality and customer satisfaction, educational administrators should be mindful of the importance of soliciting input from multiple stakeholders and incorporating this into their decisions for improving organizational processes.

Limitations and future research

The MBNQA data for educational organizations is only available for the 1999–2006 period. This study could have been more effective if it had used more recent data for this model. Another limitation of the study is related to the sample size. While we were able to assess the validity of the results using a variety of fit indices, it is recommended that future studies examine the validity of the Baldrige model in educational institutions using a larger sample.

Furthermore, the availability and inclusion of other related parameters—such as age, size, and organizational type (i.e., private vs. public)—could have yielded valuable insights about the effects of these contextual and organizational parameters on quality outcomes in educational organizations. Some argue that the success of an organization such as Arizona State University in revolutionizing its educational system is related to its size (Salisbury and Horn 2019). Thus, the inclusion of other variables would have supported a more nuanced assessment of quality management in educational organizations. We are mindful that access to more detailed information about educational organizations such as type of the organization (e.g., university, non-profit) along with other organizational factors would provide a more robust assessment of quality management in educational organizations.

We should also be careful about generalizing this study’s outcomes. Since we used data from the United States, we may reasonably expect that we could extend the findings to other economies that experience similar management, social, and legal platforms. It would also be interesting to compare, analyze, and generalize the impact of similar quality excellence frameworks—such as the Deming Prize, EFQM, and other national quality award models—on the quality and operational outcomes of educational organizations.

Appendix A Description of each sub-construct listed in

| Construct | Items (sub-constructs) |

|---|---|

| 1. Leadership (LEA) |

L11) Senior Leadership: How do your senior leaders lead the organization? L12) Governance and Societal Contributions: How do you govern your organization and make societal contributions? |

| 2. Strategic Quality Planning (STR) |

S21) Strategy Development: How do you develop your strategy? S22) Strategy Implementation: How do you implement your strategy? |

| 3. Customer Focus and Satisfaction (CFS) |

C31) Customer Expectations: How do you listen to your customers and determine products and services to meet their needs? C32) Customer Engagement: How do you build relationships with customers and determine satisfaction and engagement? |

| 4. Information and Analysis (INF) |

I41) Measurement, Analysis, and Improvement of Organizational Performance: How do you measure, analyze, and then improve organizational performance? I42) Information and Knowledge Management: How do you manage your information and your organizational knowledge assets? |

| 5. Human Resource Development and Management (HRD) |

H51) Workforce Environment: How do you build an effective and supportive workforce environment? H52) Workforce Engagement: How do you engage your workforce for retention and high performance? |

| 6. Management of Process Quality (PRO) |

P61) Work Processes: How do you design, manage, and improve your key products and work processes? P62) Operational Effectiveness: How do you ensure effective management of your operations? |

| 7. Quality and Operational Results (RES) |

Q71) Product and Process Results: What are your product performance and process effectiveness results? Q72) Customer Results: What are your customer-focused performance results? Q73) Workforce Results: What are your workforce-focused performance results? Q74) Leadership and Governance Results: What are your senior leadership and governance results? Q75) Financial, Market, and Strategy Results: What are your results for financial viability and strategy implementation? |

Footnotes

The data for Baldrige assessments became available in 2011.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mahour Mellat Parast, Email: mahour.parast@asu.edu.

Arsalan Safari, Email: asafari@qu.edu.qa.

References

- Agarwal V. Investigating the convergent validity of organizational trust. J Commun Manag. 2013;17(1):24–39. doi: 10.1108/13632541311300133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ah-Teck JC, Starr K. Principals’ perceptions of “quality” in Mauritian schools using the Baldrige framework. J Educ Admin. 2013;51(5):680–704. doi: 10.1108/JEA-02-2012-0022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed PK, Machold S. The quality and ethics connection: toward virtuous organizations. Total Qual Manag Bus Excell. 2004;15(4):527–545. doi: 10.1080/1478336042000183604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aly N, Akpovi J. Total quality management in California public higher education. Qual Assur Educ. 2001;9(3):127–131. doi: 10.1108/09684880110399077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Araújo M, Sampaio P. The path to excellence of the Portuguese organizations recognized by the EFQM model. Total Qual Manag Bus Excell. 2014;25(5/6):427–438. doi: 10.1080/14783363.2013.850810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ardi R, Hidayatno A, Yuri M, Zagloel T. Investigating relationships among quality dimensions in higher education. Qual Assur Educ. 2012;20(4):408–428. doi: 10.1108/09684881211264028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asif M, de Bruijn EJ, Douglas A, Fisscher OAM. Why quality management programs fail: A strategic and operations management perspective. Int J qua Reliab Manag. 2009;26(8):778–794. doi: 10.1108/02656710910984165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asif M, Awan MU, Khan MK, Ahmad N. A model for total quality management in higher education. Qual Quant. 2013;47:1883–1904. doi: 10.1007/s11135-011-9632-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Assarlind M, Gremyr I. Initiating quality management in a small company. The TQM Journal. 2016;28(2):166–179. doi: 10.1108/TQM-01-2014-0003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Attig N, Cleary S. Managerial practices and corporate social responsibility. J Bus Ethics. 2015;131:121–136. doi: 10.1007/s10551-014-2273-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badri MA, Selim H, Alshare K, Grandon EE, Younis H, Abdulla M. The Baldrige education criteria for performance excellence framework: Empirical test and validation. Int J qua Reliab Manag. 2006;23(9):1118–1157. doi: 10.1108/02656710610704249. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi R, Yi Y. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci. 2012;40(1):8–34. doi: 10.1007/s11747-011-0278-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay PK, Leonard D. The value of using the Baldrige performance excellence framework in manufacturing organizations. J qua Participation. 2016;39(3):10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Basari G, Altina Z. Tolerance, equality and access in all levels of education quality management. Qual Quant. 2018;52:S961–S967. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0550-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becket N, Brookes M. Evaluating quality management in university departments. Qual Assur Educ. 2006;14(2):123–142. doi: 10.1108/09684880610662015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsley DA, Kuh E, Welsch RE. Regression Diagnostics: Identifying Influential Observations and Sources of Collinearity. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Boisjoly RM. Personal integrity and accountability. Account Horiz. 1993;7(1):59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bourke J, Roper S. Innovation, quality management and learning: Short-term and longer-term effects. Res Policy. 2017;46(8):1505–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2017.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan J, Shah T. Quality assessment and institutional change: experiences from 14 countries. High Educ. 2000;40:331–349. doi: 10.1023/A:1004159425182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]