Abstract

A detailed study of the reaction of CF3-ynones with NaN3 was performed. It was found that the reaction permits the selective synthesis of either 4-trifluoroacetyltriazoles or 5-CF3-isoxazoles. The chemoselectivity of the reaction was switchable via acid catalysis. The reaction of CF3-ynones with NaN3 in EtOH produced high yields of 4-trifluoroacetyltriazoles. In contrast, the formation of 5-CF3-isoxazoles was observed under catalysis by acids. This acid-switchable procedure can be performed at sub-gram scale. The possible reaction mechanism was supported by DFT calculations. The synthetic utility of the prepared 4-trifluoroacetyltriazoles was demonstrated.

Keywords: CF3-ynones, sodium azide, triazoles, isoxazoles, CF3-group

1. Introduction

The chemistry of fluorinated compounds is a rapidly developing area of modern organic chemistry [1,2,3,4]. Owing to their unique physicochemical and biological properties, organofluorine compounds are used intensively as construction materials, components of liquid crystalline compositions, agrochemicals and pharmaceuticals [5,6,7,8,9,10]. Nowadays about 20% of currently used drugs [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] and agrochemicals [20,21,22,23] contain at least one fluorine atom. Heterocycles are also attractive for medicinal chemistry due to their various biological activities. Thus, numerous drugs and agrochemicals are heterocyclic compounds [24,25,26,27,28,29]. About 59% of small-molecule drugs approved by the US FDA contain a nitrogen heterocycle in their structure [30]. As a result, the search for novel effective methodologies for the synthesis of fluorinated heterocycles has been an important task in recent decades [31,32,33].

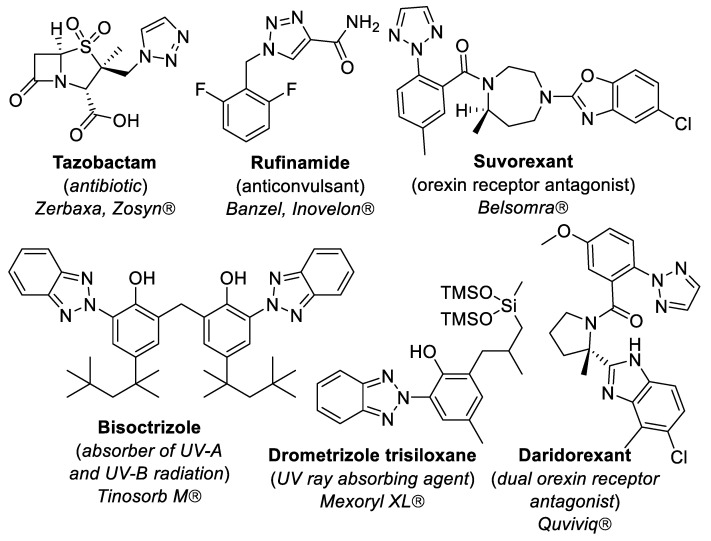

The 1,2,3-triazole scaffold has been intensively investigated in recent decades, boosted by the discovery of CuAAC–RuAAC reactions (metal-catalyzed alkyne–azide cycloaddition) [34]. Many triazoles were found to exhibit useful practical properties and found applications as agrochemicals, pigments, metal chelators, photostabilizers and corrosion inhibitors [35]. N-2-Aryl-1,2,3-triazole derivatives behave as highly efficient UV/blue-light-emitting fluorophores [36,37,38]. Pharmaceutical and therapeutic applications of triazoles are of special interest [39]. Triazoles revealed properties of antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antiepileptic, antiviral, antimalarial, anti-Alzheimer’s, antioxidant, antitubercular, antidiabetic, antiobesity, anticonvulsant, anti-cancer, anti-acetylcholinesterase, and antiparasitic agents [40,41,42]. Several 1,2,3-triazole derivatives have been approved by FDA and are already on the market: tazobactam (antibiotic) [43], rufinamide (anticonvulsant) [44], suvorexant (orexin receptor antagonist for the treatment of insomnia) [45], bisoctrizole (absorber of UV-A and UV-B radiation) [46], drometrizole trisiloxane (UV ray absorbing agent) [47] and daridorexant (dual orexin receptor antagonist used to treat insomnia in adults) [48] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

1,2,3-Triazole-containing marketed drugs.

CF3-ynones are valuable building-blocks for the synthesis of various fluorinated heterocycles [49,50]. Recently, on the basis of CF3-ynones, we elaborated novel approaches to fluorinated diazepines [51], pyrimidines [52], thiophenes [53], triazoles [54], pyrazoles [55,56,57], 1,3-oxazinoquinolines [58,59,60,61] and quinolones [62]. This article reports novel effective acid-switchable pathways to 4-trifluoroacetyltriazoles and 5-trifluoromethylisoxazoles based on the reaction of CF3-ynones with sodium azide.

2. Results

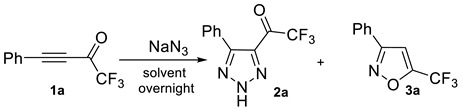

We envisioned that the reaction of CF3-ynones with sodium azide would lead to triazoles 2 via a Michael addition followed by spontaneous cyclization of the intermediates formed. We chose CF3-ynone 1a as a model compound for exploring the cyclization conditions. First, several solvents were tested to search for an optimal reaction medium. It was found that the reaction is extremely sensitive to the nature of a solvent. Thus, the transformation of CF3-ynone 1a in non-polar toluene led to triazole 2a in a 2% yield only (see Table 1). Better yields of 2a were observed in more polar acetone, acetonitrile, THF and ethyl acetate (entries 2–5). In the case of most polar aprotic solvents in the row (DMF, DMSO and NMP, entries 6–8) the yields of 2a increased to about 50%. Eventually, we found that the best yields of 2a can be obtained in alcohols. Thus, the reactions in methanol and ethanol led to 2a in 77% and 81% yields, respectively (entries 9–10). It should be noted that full conversion of CF3-ynone 1a was observed in all mentioned solvents. It was also found that the main byproduct of the reaction was isoxazole 3a, which was formed in small amounts.

Table 1.

Investigation of the solvents’ nature in the reaction of sodium azide with CF3-ynone 1.

| Entry | Solvent | Yield of 2a, % a | Yield of 3a, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PhMe | 2 | 12 |

| 2 | Acetone-H2O | 12 | 5 |

| 3 | MeCN | 26 | 7 |

| 4 | THF | 19 | 12 |

| 5 | EtOAc-H2O | 23 | 14 |

| 6 | DMF | 49 | 2 |

| 7 | DMSO | 48 | 1 |

| 8 | NMP | 52 | 2 |

| 9 | MeOH | 77 | 4 |

| 10 | EtOH | 85(81 b) | 3 |

a—by 19F NMR; b—isolated yield.

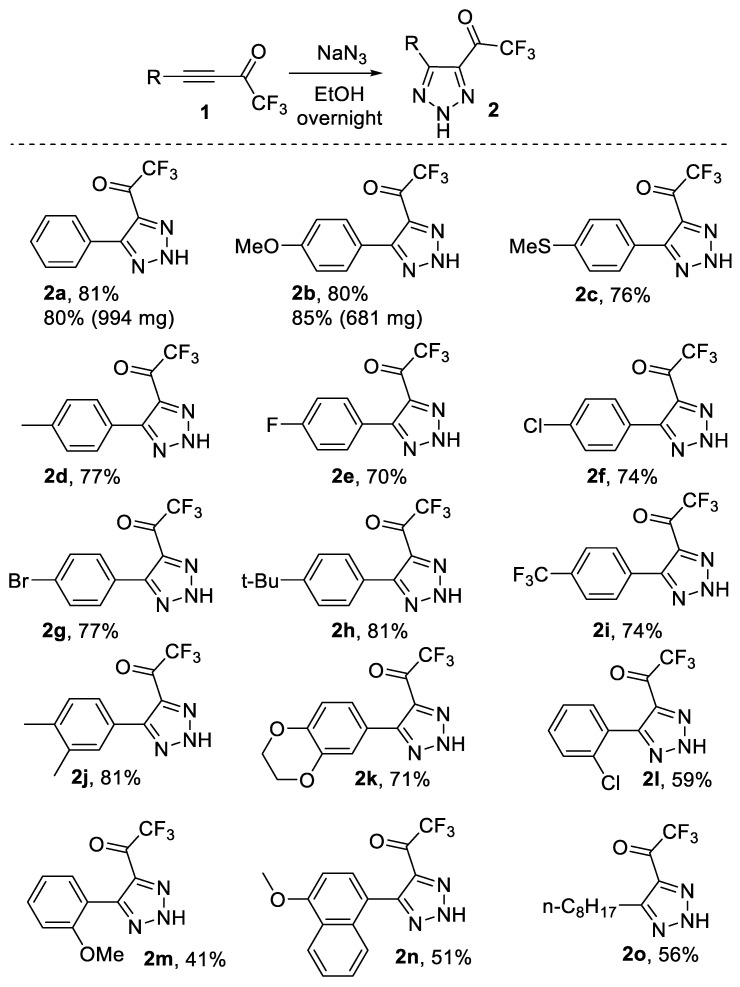

Having optimal conditions in hand, we decided to study the scope of the synthesis of trifluoroacylated triazoles. To this end, we performed a series of reactions with various CF3-ynones. To our delight, the reaction was found to be very general. The yield of 3 did not depend on electronic nature of the substituents in the aryl ring of CF3-ynones to give target triazoles in 70–80% yields (2a–k). The steric demand was found to be more crucial for the reaction outcome. Thus, the reaction with ortho-substituted CF3-ynones 1l,m and naphthalene derivative 1n produced triazoles in 41–59% yields. Alkyl-substituted ynone 1o was also successfully involved in the reaction to form triazole 2o in good yields. We also demonstrated scalability of the method (Scheme 1). Gram-scale synthesis of triazoles 2a,b was performed to give the products in high yields (80–85%). It should be noted, that NH-triazoles 2 are a novel class of fluorinated triazoles which have not been reported yet. The structure of triazoles 2 was confirmed beyond doubt by NMR, FT-IR and HRMS spectra. Thus, the presence of the trifluoroacetyl group (2a as an example) was proven by quadruplets in 13C NMR at 174.4 ppm (C=O) and 116.2 ppm (CF3) as well as by the signal at 1719 cm−1 (C=O) in FT-IR. Two signals in the low field in 13C NMR at 147.7 ppm and 136.1 ppm were the quaternary carbons of the triazole moiety. A broad singlet at 12.75 ppm in 1H NMR and a broad band near 3000 cm−1 in FT-IR confirm the presence of a NH-triazole moiety.

Scheme 1.

Reactions of CF3-ynones 1 with NaN3 in ethanol.

The acidic nature of NH-triazoles is well known (pKa~9.26) [63]. The presence of the electron-withdrawing trifluoroacetyl group made triazoles 2 highly acidic and soluble in water at basic pH. We successfully used this feature of triazoles 2 for their purification. After the evaporation of ethanol, the residue was dispersed between water and a mixture of heptane and ethyl acetate. The organic phase containing all by-products was thrown away and the water phase was acidified to form pure triazole 2. It should be noted that all solvents used in this protocol are listed as green ones and the amount of waste was minimal. The E-factor calculated for gram scale synthesis of 2a was 13.6, which is a good value for fine chemicals. Therefore, we can describe the method proposed as a green one.

Next, we focused our attention on isoxazoles 3, formed as by-products in the reaction of CF3-ynones with sodium azide. Isoxazole is another popular scaffold for drug design. These heterocycles exhibit antimicrobial, antiviral, antifungal, anti-tuberculosis, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antipyretic, immunomodulatory, anticonvulsant and anti-diabetic properties [64,65]. Several isoxazole-containing drugs have already been marketed [66].

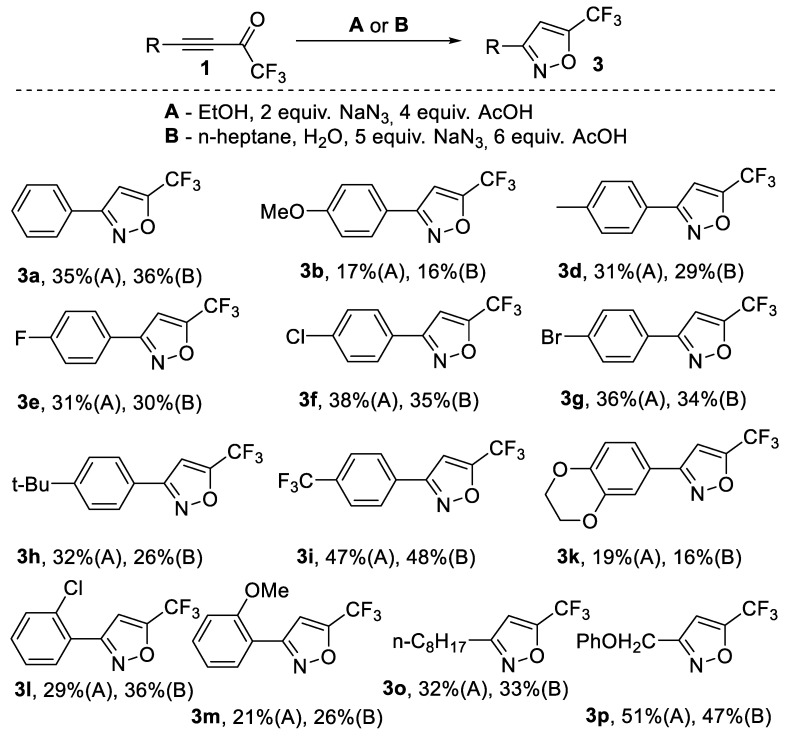

We proposed the possibility of switching the reaction direction from triazole 2 to isoxazole 3. One can notice that NaN3 is a salt that is strongly basic and weakly acidic. As a result, solutions formed by NaN3 have a slightly basic pH. We decided to add acid to the reaction in order to neutralize even acidic pH. To our delight, this manipulation permitted us to switch the selectivity of the reaction to make the formation of izoxazole 3 a major reaction path. Thus, the addition of various organic acids such as HCOOH, CH3COOH, CH2ClCOOH and CF3COOH changed the reaction direction in the same solvent (EtOH) to form isoxazole 3, while triazole 2 became a minor product. Moreover, similar results were obtained in the heptane-H2O system. Both conditions gave isoxazole 3a in isolated yields of 35–36%. A control experiment without the addition of any acid was performed in heptane-H2O. It was found, that CF3-ynone 1a was fully consumed and the reaction led to trace amounts of triazole 2a and isoxazole 3a along with much tarring. So, the role of acid is crucial in the formation of isoxazole 3a. Next, we examined several other solvents in the reaction using acetic acid as a catalyst (see Supplementary Materials). Again, the reaction in the presence of acid led to isoxazole 3a in 35–41% yields (by 19F NMR) in MeOH, EtOAc, PhMe, dioxane and TCE (1,1,2-trichloroethylene) (Table S2). The reaction in quite acidic CF3CH2OH could be performed without the addition of any acids to give isoxazole 3a in a 37% yield. Eventually, a reaction in acetic acid led to the same yield of isoxazole. It should be noted that the application of stronger acids (MeSO3H and HCl) blocks the conversion of CF3-ynone in the reaction mixture. Taking into account the list of green solvents, we chose the EtOH and n-heptane-water systems as solvents for further investigation of the reaction. Ethanol was chosen because, in this case, there was obviously a possibility of elegantly managing the reaction direction via the simple addition of acetic acid (also a green solvent). The use of n-heptane simplified the isolation and purification of isoxazoles 3. Thus, after completion of the reaction, isoxazole 3a was placed in n-heptane (upper phase), while the by-products were mostly present the third phase below water. n-Heptane phase could be easily separated to give a solution of pure isoxazole in most cases (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Reactions of ynones 1 with NaN3 in ethanol and in n-heptane in the presence of acid.

Using the above-mentioned optimal conditions for the synthesis of isoxazoles 3, we carried out a series of reactions with a set of CF3-ynones. It was found that unlike in the synthesis of triazoles, the yields of isoxazoles were very sensitive to the electronic nature of the substituents in the aryl ring of CF3-ynones. Thus, the CF3-ynone with an electron-withdrawing CF3 group in the aryl ring produced isoxazole 3i yields of 48%. In contrast, the reaction with ynones bearing electron-donating alkoxy-groups (1b,k,m) led to isoxazoles 3 in lower yields. The yields of other aryl isoxazoles were in the range of 26–36%. Alkyl-substituted ynones 1o,p were also successfully used in the reaction to give isoxazoles 3o,p in 33 and 51% yields, respectively (Scheme 2).

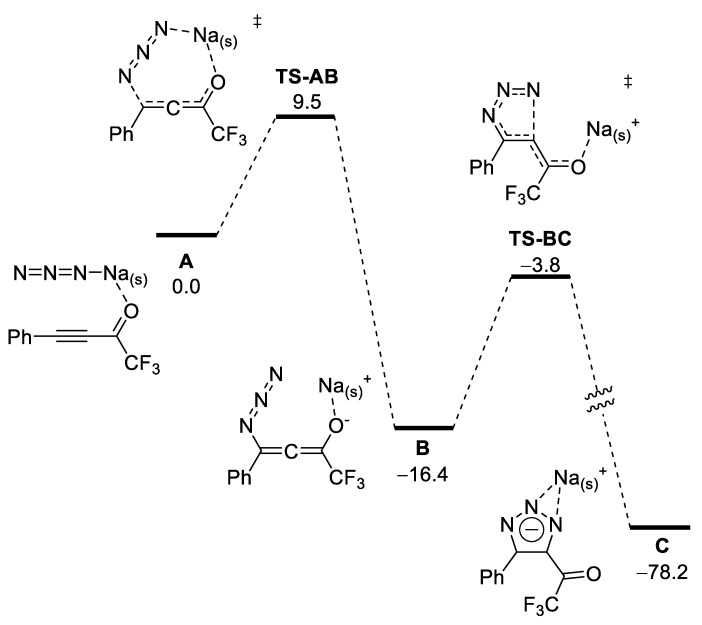

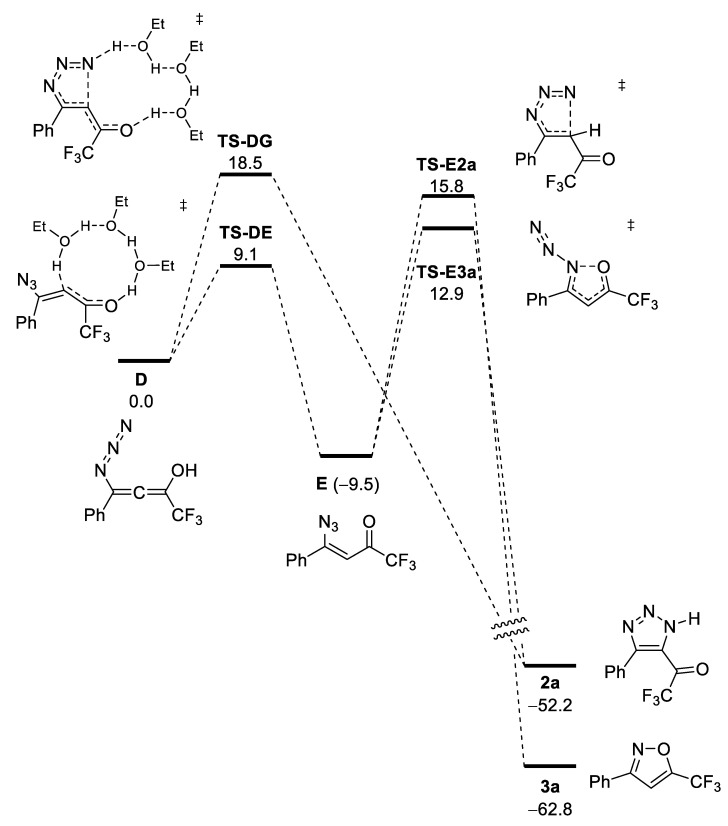

To rationalize the observed selectivity of the reactions of sodium azide with ynones, we performed DFT modeling (for details, see supporting information). Precomplex A consists of ynone, and sodium azide solvated by four ethanol molecules. The addition of azide to the triple bond proceeds via low-lying transition state TS-AB to give allene B. Then, through transition state TS-BC, the triazolate C is formed. The reaction is highly exergonic (ΔG = −78.2 kcal/mol). The rate-limiting energy barrier corresponds to TS-BC (ΔΔG≠ = ΔG(TS-BC) − ΔG(B) = 12.6 kcal/mol) [67]. Thus, under non-acidic conditions, the reaction proceeds with a very low barrier to give triazole at a rate that is determined mainly by the rate of dissolution of sodium azide in the reaction medium (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Plausible DFT mechanism of formation of triazoles in absence of acid (numbers are relative Gibbs free energies in kcal/mol; Na(s)+ = Na(EtOH)4+).

Hydrogen azide and acetic acid have virtually the same pKa values (in water), at 4.75 and 4.76, respectively. It should be expected that in the presence of acetic acid, NaN3 and HN3 are in equilibrium in the reaction media. Thus, it can be supposed that under such conditions, azide is bound to ynone to give allene B in the same manner as in the absence of acetic acid (Scheme 3). Importantly, the allene B can be regarded as sodium enolate, which is strongly basic. Thus, we suppose that under acidic conditions, enolate B is immediately protonated to give a neutral form of allene D (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Plausible DFT mechanism of formation of isoxazoles in presence of acid (numbers are relative Gibbs free energies in kcal/mol).

Allene D can undergo isomerization via transition state TS-DE to give azide E, or via transition state TS-DG to give triazole 2a. Since TS-DE lies 9.4 kcal/mol lower in energy than TS-DG, the main route of the reaction is the formation of azide E. Isoxazole 3a is formed via cyclization and the simultaneous release of dinitrogen via transition state TS-E3a. Alternatively, triazole 2a can be formed from E via transition state TS-E2a. Transition states leading to isoxazole and triazole are rather close in energy; however, TS-E3a lies 2.9 kcal/mol lower. Thus, under room temperature conditions, selectivity of the formation of isoxazole:triazole should be expected to be greater than 100:1. Overall the energetic barrier of the formation of isoxazole ΔΔG≠ = ΔG(TS-E3a) − ΔG(E) = 22.4 kcal/mol. Such an energy barrier corresponds well with the observed completion of the reaction within a few hours at r.t.

The DFT calculation can also explain the lower yield of isoxazoles 3. We believe that only Z-configurated vinylazide E can cyclize into izoxazole. Another diastereomer has a disfavored arrangement of the azide group and the trifluoroacetyl moiety. As a result, the formation of polymeric products takes place.

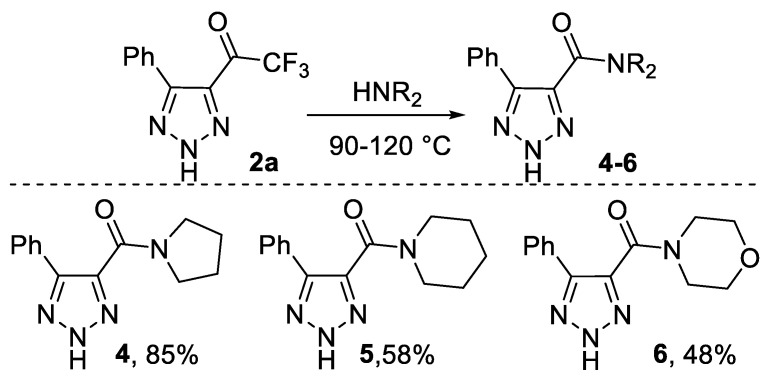

It should be noted that N-unsubstituted 4-trifluoroacyl triazoles 2 are a novel class of fluorinated compounds which have not been reported yet. In this article, we started an investigation of the chemical properties of triazoles. We found that trifluoroacetyl triazoles react with secondary amines at elevated temperatures to give the corresponding amides (derivatives of pyrrolidine, piperidine and morpholine) in quite good yields (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

Reactions of triazole 2a with secondary amines.

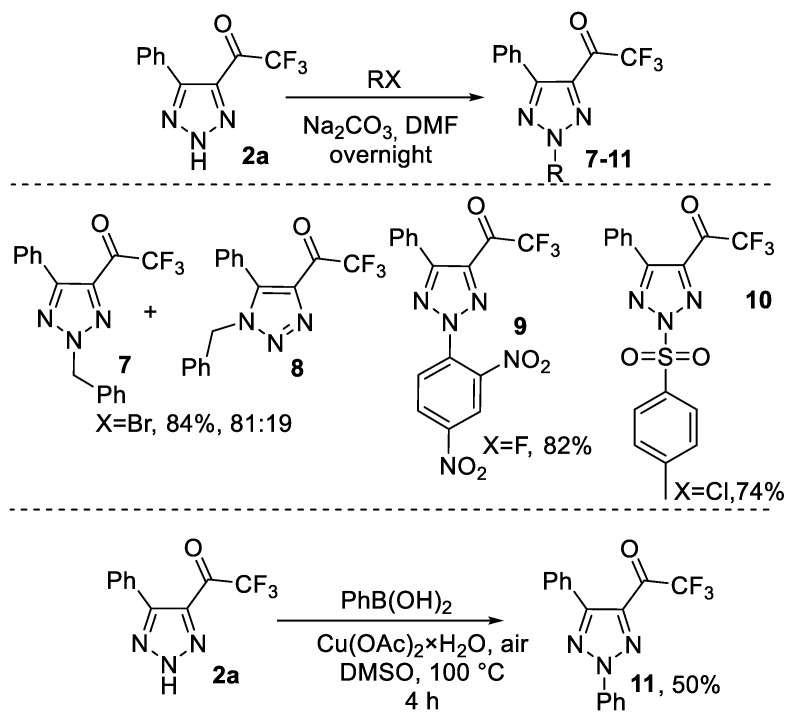

Next, we studied modification of the NH moiety of triazoles 2. We performed alkylation of model triazole 2a in DMF using Na2CO3 as a base. It was found that the reaction with benzyl bromide led mostly to 2-benzyltriazole 7 along with 1-benzylisomer 8 in an 81:19 ratio. In contrast, the arylation and sulfonylation of 2a proceeded 100% regioselectively to give only 2-substituted products, 9 and 10, in high yields. Similarly, the reaction with phenyl boronic acid in non-optimized conditions of the Chan–Lam reaction 100% regioselectively produced a 50% yield of 2-phenyltriazole 11. It should be noted that N-2-aryl-1,2,3-triazoles are of special interest due to their possible properties of UV/blue-light-emitting fluorophores [36,37,38]. Thorough investigation of the alkylation and arylation of triazoles 2, as well as their UV/blue-light-emitting properties, is currently in progress and is going to be published soon (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Modification of NH moiety of triazole 2a.

3. Materials and Methods

General remarks.1H, 13C and 19F NMR spectra were recorded using a Bruker AVANCE 400 MHz spectrometer in acetone-d6, CD3CN and CDCl3 at 400, 100 and 376 MHz, respectively. Chemical shifts (δ) in ppm are reported based on the residual acetone-d5, CHD2CN and chloroform signals (2.04, 1.94 and 7.25 for 1H and 29.8, 1.3, 77.0 for 13C) as internal references. The 19F chemical shifts were referenced to C6F6, (−162.9 ppm). The coupling constants (J) are given in Hertz (Hz). ESI-MS spectra were measured using an Orbitrap Elite instrument. For FT-IR, a spectrometer was employed using consoles of internal reflection iS3 with ATR element from ZnSe and a dip angle of 45 °C. TLC analysis was performed on “Merck 60 F254” plates. Column chromatography was performed usig silica gel “Macherey-Nagel 0.063–0.2 nm (Silica 60)”. In all cases, gravity column chromatography was used. All reagents were of reagent grade and were used as such or were distilled prior to use. CF3-ynones 1 [68] were prepared as reported previously. Melting points were determined using Electrothermal 9100 apparatus.

Investigation of reaction of CF3-ynones with NaN3 in various solvents. A 4 mL vial with a screw cap was charged with CF3-ynone 1a (0.099 g, 0.5 mmol), corresponding solvent (2 mL, see Table 1) and NaN3 (0.039 g, 0.6 mmol, 1.2 equiv.). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight using a magnetic stirrer. The composition of the reaction mixture was established via 19F NMR using PhCF3 as a standard for calculation of the products’ yields. It is important to note that all manipulations with azides demand significant care for safety reasons.

Synthesis of triazoles 2 (general procedure). An 8 mL vial with a screw cap was charged with corresponding CF3-ynone 1 (1 mmol), ethanol (4 mL) and NaN3 (0.078 g, 1.2 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight using a magnetic stirrer. Next, ethanol was evaporated in vacuo; the residue was suspended in the heptane–ethylacetate mixture (1:1, 0.5–1 mL) and purified via column chromatography using gradient elution with mixtures of heptane–ethylacetate (9:1, 3:1 and 1:1). Evaporation of the solvents produced pure triazoles 2.

2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(5-phenyl-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)ethanone (2a). Obtained from 1a (0.202 g, 1.02 mmol). White crystals, m.p. 105–108 °C, yield 0.199 g (81%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 12.75 (br.s, 1H), 7.89–7.75 (m, 2H), 7.58–7.45 (m, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.4 (q, 2JCF = 37.2 Hz), 147.7, 136.1, 131.3, 129.0, 128.9, 125.1, 116.2 (q, 1JCF = 290.6 Hz). 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −75.0 (s, 3F). 1H NMR (CD3CN, 400.1 MHz): δ 12.75 (br.s, 1H), 7.85–7.74 (m, 2H), 7.61–7.49 (m, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CD3CN, 100.6 MHz): δ 175.2 (q, 2JCF = 36.3 Hz), 148.1, 137.0, 131.7, 130.1, 129.6, 127.1, 117.4 (q, 1JCF = 290.2 Hz). 19F NMR (CD3CN, 376.5 MHz): δ −73.0 (s, 3F). 1H NMR (acetone-d6, 400.1 MHz): δ, 8.06–7.98 (m, 2H), 7.41–7.28 (m, 3H), 5.14 (br.s, 1H). 13C{1H} NMR (acetone-d6, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.7 (q, 2JCF = 33.4 Hz), 152.0, 136.1, 133.5, 129.5, 128.51, 128.45, 118.6 (q, 1JCF = 291.6 Hz). 19F NMR (acetone-d6, 376.5 MHz): δ −70.7 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd for C10H7F3N3O+: 242.0536; found: 242.0536. IR (ν, cm−1): 1719 (C=O).

2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)ethanone (2b). Obtained from 1b (0.228 g, 1 mmol). Pale brown solid, m.p. 100–102 °C, yield 0.216 g (80%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 13.87 (br.s, 1H), 7.84 (d, 2H, 3J = 8.8 Hz), 7.97 (d, 2H, 3J = 8.8 Hz), 3.84 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.2 (q, 2JCF = 37.0 Hz), 162.0, 146.7, 135.5, 130.7, 116.5, 116.3 (q, 1JCF = 290.7 Hz), 114.3, 55.4. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −74.7 (s, 3F). 1H NMR (acetone-d6, 400.1 MHz): δ 13.41 (br.s, 1H), 7.91 (d, 2H, 3J = 7.9 Hz), 7.08 (d, 2H, 3J = 8.0 Hz), 3.88 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (acetone-d6, 100.6 MHz): δ 175.0 (q, 2JCF = 36.0 Hz), 162.4, 147.9, 136.2, 131.5, 127.8, 117.5 (q, 1JCF = 290.6 Hz), 114.7, 55.7. 19F NMR (acetone-d6, 376.5 MHz): δ −72.6 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C11H9F3N3O2+: 272.0641; found: 272.0641. IR (ν, cm−1): 1719 (C=O).

2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(5-(4-methylthio)phenyl)-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)ethanone (2c). Obtained from 1c (0.123 g, 0.504 mmol). Pale yellow-brown solid, m.p. 102–104 °C, yield 0.110 g (76%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 13.99 (br.s, 1H), 7.75 (d, 2H, 3J = 8.4 Hz), 7.26 (d, 2H, 3J = 7.9 Hz), 2.5 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.2 (q, 2JCF = 37.2 Hz), 147.0, 143.7, 135.7, 129.1, 125.5, 120.7 (d, 4JCF = 1.6 Hz), 116.2 (q, 1JCF = 290.8 Hz), 14.7. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −74.8 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C11H9F3N3OS+: 288.0413; found: 288.0417. IR (ν, cm−1): 1722 (C=O).

2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(5-(p-tolyl)-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)ethanone (2d). Obtained from 1d (0.424 g, 2 mmol). Pale beige powder, m.p. 128–130 °C, yield 0.395 g (77%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 13.41 (br.s, 1H), 7.72 (d, 2H, 3J = 7.9 Hz), 7.28 (d, 2H, 3J = 8.0 Hz), 2.41 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.2 (q, 2JCF = 37.1 Hz), 146.9 (q, 4JCF = 2.3 Hz), 142.0, 135.6, 129.5, 128.9, 121.4, 116.2 (q, 1JCF = 290.7 Hz), 21.4. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −75.0 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C11H9F3N3O+: 256.0692; found: 256.0692. IR (ν, cm−1): 1719 (C=O).

2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(5-(4-fluorophenyl)-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)ethanone (2e). Obtained from 1e (0.110 g, 0.509 mmol). Pale beige solid, m.p. 85–87 °C, yield 0.092 g (70%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 11.12 (br.s, 1H), 7.90–7.79 (m, 2H), 7.15 (t, 2H, 3J = 8.3 Hz). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.3 (q, 2JCF = 37.4 Hz), 164.3 (d, 1JCF = 252.8 Hz), 147.5, 136.0, 131.3 (d, 3JCF = 8.8 Hz), 121.7, 116.2 (q, 1JCF = 290.5 Hz), 116.0 (d, 2JCF = 22.1 Hz). 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −75.0 (s, 3F), 109.1 (s, 1F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C10H6F4N3O+: 260.0442; found: 260.0447. IR (ν, cm−1): 1726 (C=O).

1-(5-(4-Chlorophenyl)-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)-2,2,2-trifluoroethanone (2f). Obtained from 1f (0.233 g, 1 mmol). Pale beige solid, m.p. 83–85 °C, yield 0.203 g (74%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 14.05 (br.s, 1H), 7.75 (d, 2H, 3J = 8.3 Hz), 7.42 (d, 2H, 3J = 8.2 Hz). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.3 (q, 2JCF = 37.3 Hz), 147.1, 137.5, 136.0, 130.3, 129.1, 123.6, 116.1 (q, 1JCF = 290.6 Hz). 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −74.9 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C10H6[35Cl]F3N3O+: 276.0146; found: 276.0151; calcd. for C10H6[37Cl]F3N3O+: 278.0117; found: 278.0121. IR (ν, cm−1): 1726 (C=O).

1-(5-(4-Bromophenyl)-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)-2,2,2-trifluoroethanone (2g). Obtained from 1g (0.186 g, 0.671 mmol). Pale beige solid, m.p. 82–84 °C, yield 0.166 g (77%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 13.39 (br.s, 1H), 7.69 (d, 2H, 3J = 8.5 Hz), 7.59 (d, 2H, 3J = 8.5 Hz). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.3 (q, 2JCF = 37.7 Hz), 147.5, 136.1, 132.1, 130.5, 125.8, 124.4, 116.1 (q, 1JCF = 290.3 Hz). 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −75.0 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C10H6[79Br]F3N3O+: 319.9641; found: 319.9646; m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C10H6[81Br]F3N3O+: 321.9620; found: 321.9625. IR (ν, cm−1): 1723 (C=O).

1-(5-(4-(Tret-butyl)phenyl)-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)-2,2,2-trifluoroethanone (2h). Obtained from 1h (0.130 g, 0.512 mmol). Light brown powder, m.p. 140–143 °C, yield 0.123 g (81%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 14.12 (br.s, 1H), 7.82 (d, 2Н, 3J = 8.3 Hz), 7.53 (d, 2Н, 3J = 8.2 Hz), 1.35 (s, 9H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.3 (q, 2JCF = 37.1 Hz), 155.1, 147.0, 135.9, 128.8, 126.0, 121.6, 116.3 (q, 1JCF = 290.7 Hz), 35.0, 31.0. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −74.9 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C14H15F3N3O+: 298.1162; found: 298.1166. IR (ν, cm−1): 1712 (C=O).

2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(5-(4-trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)ethanone (2i). Obtained from 1i (0.268 g, 1.01 mmol). Pale yellow solid, m.p. 67–69 °C, yield 0.230 g (74%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 10.94 (br.s, 1H), 7.94 (d, 2H, 3J = 8.2 Hz), 7.71 (d, 2H, 3J = 8.3 Hz). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.5 (q, 2JCF = 37.8 Hz), 148.2, 136.5, 132.6 (q, 2JCF = 32.9 Hz), 129.8, 129.5, 125.7 (q, 3JCF = 3.6 Hz), 123.6 (q, 1JCF = 272.4 Hz), 116.1 (q, 1JCF = 290.4 Hz). 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −64.2 (s, 3F), −75.1 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C11H6F6N3O+: 310.0410; found: 310.0416. IR (ν, cm−1): 1718 (C=O).

1-(5-(3,4-Dimethylphenyl)-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)-2,2,2-trifluoroethanone (2j). Obtained from 1j (0.118 g, 0.522 mmol). Pale brown solid, m.p. 76–78 °C, yield 0.114 g (81%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 14.05 (br.s, 1H), 7.63–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.21 (d, 1H, 3J = 7.7 Hz), 2.30 (s, 3H), 2.28 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.2 (q, 2JCF = 37.1 Hz), 146.9, 140.7, 137.4, 135.6, 130.1, 129.8, 126.4, 121.8, 116.3 (q, 1JCF = 290.7 Hz), 19.8, 19.6. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −74.8 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C12H11F3N3O+: 270.0849; found: 270.0856. IR (ν, cm−1): 1722 (C=O).

1-(5-(2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxin-6-yl)-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)-2,2,2-trifluoroethanone (2k). Obtained from 1k (0.240 g, 1.025 mmol). Slightly yellow oil, yield 0.218 g (71%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 13.85 (br.s, 1H), 7.35 (s, 1Н), 7.31 (d, 1Н, 3J = 8.5 Hz), 6.90 (d, 1Н, 3J = 8.4 Hz), 4.31–4.23 (m, 4H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.3 (q, 2JCF = 37.0 Hz), 146.9, 146.2, 143.5, 135.6, 122.5, 120.6, 118.1, 117.7, 117.8 (q, 4JCF = 3.1 Hz), 116.3 (q, 1JCF = 290.7 Hz), 64.5, 64.1. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −74.8 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C12H9F3N3O3+: 300.0591; found: 300.0595. IR (ν, cm−1): 1717 (C=O).

1-(5-(2-Chlorophenyl)-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)-2,2,2-trifluoroethanone (2l). Obtained from 1l (0.237 g, 1.015 mmol). Pale brown viscous oil, yield 0.164 g (59%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 13.55 (br.s, 1H), 7.80–7.25 (m, 4H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 173.9 (q, 2JCF = 38.1 Hz), 145.0, 137.7, 133.5, 131.8, 131.3, 129.9, 126.9, 125.3, 115.8 (q, 1JCF = 290.2 Hz). 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −75.6 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C10H6[35Cl]F3N3O+: 276.0146; found: 276.0149; calcd. for C10H6[37Cl]F3N3O+: 278.0117; found: 278.0118. IR (ν, cm−1): 1726 (C=O).

2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(5-(2-methoxyphenyl)-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)ethanone (2m). Obtained from 1m (0.195 g, 0.867 mmol). Pale brown solid, m.p. 130–132 °C, yield 0.097 g (41%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 10.67 (br.s, 1H), 7.61 (dd, 1Н, 3J = 8.5 Hz, 4J = 8.5 Hz), 7.42–7.38 (m, 1H), 7.00–6.94 (m, 2Н), 3.74 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.6 (q, 2JCF = 36.5 Hz), 156.4, 142.0, 136.6, 132.1, 130.7, 120.3, 116.0 (q, 1JCF = 290.6 Hz), 113.7, 110.8, 55.2. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −74.7 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C11H9F3N3O2+: 272.0641; found: 272.0625.

2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(5-(4-methoxynaphthalen-1-yl)-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)ethanone (2n). Obtained from 1n (0.215 g, 0.773 mmol). Slightly yellow oil, yield 0.127 g (51%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 13.00 (br.s, 1H), 8.36–8.30 (m, 1Н), 7.53–7.36 (m, 4H), 6.81 (d, 1Н, 3J = 7.9 Hz), 4.04 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 173.9 (q, 2JCF = 37.6 Hz), 157.7, 145.8, 137.8, 131.8, 129.6, 127.9, 125.9, 125.5, 123.7, 122.8, 116.0 (q, 1JCF = 290.4 Hz), 114.4 103.0, 55.7. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −75.4 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C15H11F3N3O2+: 322.0798; found: 322.0805. IR (ν, cm−1): 1720 (C=O).

2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(5-octyl-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)ethanone (2o). Obtained from 1o (0.122 g, 0.521 mmol). Pale brown solid, m.p. 66–68 °C, yield 0.082 g (56%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 13.73 (br.s, 1H), 3.21–3.07 (m, 2H), 1.75–1.65 (m, 2H), 1.37–1.19 (m, 10H), 0.87–0.81 (m, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.7 (q, 2JCF = 37.1 Hz), 149.3, 136.8, 116.1 (q, 1JCF = 290.4 Hz), 31.7, 29.1, 29.0, 28.3, 24.1, 22.6, 14.0. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −75.4 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C12H19F3N3O+: 278.1475; found: 278.1475. IR (ν, cm−1): 1721 (C=O).

Synthesis of triazoles 2a,b (sub-gram scale, general procedure). A 25 mL one-neck round-bottomed flask was charged with corresponding CF3-ynone 1 (5 mmol) and ethanol (5 mL) and cooled down to 0 °C in an ice bath. Next, NaN3 (0.390 g, 6 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred overnight using a magnetic stirrer. Next, ethanol was evaporated in vacuo. The residue was dispersed in water (4 mL) and washed twice with a heptane–ethylacetate mixture (1:1, 1 mL). The organic phase was thrown away; the water phase was acidified via dropwise addition of concentrated HCl (0.8 mL, ~9–10 mmol) to form a precipitate. The water phase was decanted and the remaining precipitate was dried in vacuo.

2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(5-phenyl-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)ethanone (2a), sub-gram-scale synthesis. Obtained from 1a (1.019 g, 5.146 mmol). White crystals, m.p. 105–108 °C, yield 0.994 g (80%). Calculation of E-factor: E-factor = (mass of all reagents and solvents used)/(mass of the isolated product) = (1.019 + 0.390 + 5 mL(EtOH)×0.789 + 4 mL(H2O)×1 + 2 mL(Heptane)×0.684+ 2 mL(EtOAc)×0.902 + 0.8 mL(HCl)×1.2))//(0.994 g) = 13.509/0.994 = 13.6.

2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)ethanone (2b), sub-gram-scale synthesis. Obtained from 1b (0.674 g, 1 mmol). Pale brown solid, m.p. 100–102 °C, yield 0.681 g (85%).

Investigation of reaction of CF3-ynones with NaN3 in various solvents in the presence of acids. A 4 mL vial with a screw cap was charged with CF3-ynone 1a (0.099 g, 0.5 mmol), the corresponding solvent (2 mL, see Table S2), the corresponding acid (for quantity of acid, see Table S2) and NaN3 (for quantity, see Table S2). The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 day using a magnetic stirrer. The composition of the reaction mixture was established via 19F NMR using PhCF3 as a standard for calculation of the products’ yields.

Synthesis of isoxazoles 3 in ethanol (general procedure A). An 8 mL vial with a screw cap was charged with the corresponding CF3-ynone 1 (0.5 mmol), ethanol (2 mL), acetic acid (0.120 g, 2 mmol, 4 equiv.) and NaN3 (0.065 g, 1 mmol, 2 equiv.). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight using a magnetic stirrer. Next, ethanol was evaporated in vacuo at room temperature (it is important to note that isoxazoles 4a and 4x are quite volatile); the residue was suspended in the heptane–ethylacetate mixture (3:1, 0.5) and passed through a short silica gel pad via gradient elution using the heptane and heptane–ethylacetate mixture (9:1). Evaporation of the solvents produced pure isoxazoles 3.

Synthesis of isoxazoles 3 in heptane (general procedure B). An 8 mL vial with a screw cap was charged with corresponding CF3-ynone 1 (0.5 mmol), heptane (4 mL), water (0.5 mL), acetic acid (0.120 g, 2 mmol, 4 equiv.) and NaN3 (0.065 g, 1 mmol, 2 equiv.). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight using a magnetic stirrer. Next, the heptane phase was separated, the water phase was extracted with a heptane–ethylacetate mixture (9:1, 2 × 0.5 mL) and the combined extract was passed through a short silica gel pad using gradient elution with heptane followed by the heptane–ethylacetate mixtures (9:1). Evaporation of the solvents produced pure isoxazoles 3.

3-Phenyl-5-(trifluoromethyl)isoxazole (3a). Obtained from 1a (0.099 g, 0.5 mmol (A); 0.100 g, 0.505 mmol (B)). White crystals, m.p. 74–77 °C (Lit.: 73.3–74 °C [69], 76–78 °C [70]), yield 0.037 g (35%, (A)); 0.039 g (36%, (B)). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 7.85–7.76 (m, 2Н), 7.54–7.44 (m, 3Н), 7.0 (s, 1H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 162.5, 159.1 (q, 2JCF = 42.6 Hz), 130.9, 129.2, 127.3, 126.9, 117.9 (q, 1JCF = 270.3 Hz), 103.4 (q, 4JCF = 2.0 Hz). 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −65.3 (s, 3F). NMR data are in agreement with those in the literature [70].

3-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)isoxazole (3b). Obtained from 1b (0.114 g, 0.5 mmol (A); 0.110 g, 0.482 mmol (B)). Pale yellow solid, m.p. 72–74 °C (Lit.: 72–75 °C [70]), yield 0.021 g (17%, (A)); 0.019 g (16%, (B)). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 7.74 (d, 2Н, 3J = 8.9 Hz), 6.99 (d, 2Н, 3J = 8.9 Hz), 6.94 (pseudo-d, 1H, 4J = 0.8 Hz), 3.86 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 162.1, 161.7, 158.9 (q, 2JCF = 42.4 Hz), 128.4, 119.7, 117.9 (q, 1JCF = 270.0 Hz), 114.6, 103.2 (q, 4JCF = 1.8 Hz), 55.4. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −65.4 (d, 3F, J = 0.9 Hz). NMR data are in agreement with those in the literature [70].

3-(4-Methylphenyl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)isoxazole (3d). Obtained from 1d (0.106 g, 0.5 mmol (A); 0.115 g, 0.542 mmol (B)). Pale yellow solid, m.p. 78–80 °C (Lit.: 79–80 °C [71]), yield 0.035 g (31%, (A)); 0.036 g (29%, (B)). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 7.70 (d, 2Н, 3J = 8.0 Hz), 7.29 (d, 2Н, 3J = 8.0 Hz), 6.97 (pseudo-d, 1H, 4J = 0.9 Hz), 2.41 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 162.5, 159.0 (q, 2JCF = 42.4 Hz), 141.2, 129.9, 126.8, 124.4, 117.9 (q, 1JCF = 270.4 Hz), 103.3 (q, 4JCF = 2.0 Hz), 21.4. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −65.4 (d, 3F, J = 0.9 Hz). NMR data are in agreement with those in the literature [71].

3-(4-Fluorophenyl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)isoxazole (3e). Obtained from 1e (0.113 g, 0.5 mmol (A); 0.113 g, 0.5 mmol (B)). Pale beige crystals, m.p. 49–50 °C (Lit.: 48 °C [72]), yield 0.036 g (31%, (A)); 0.035 g (30%, (B)). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 7.83–7.78 (m, 2Н), 7.21–7.15 (m, 2Н), 6.97 (pseudo-d, 1H, 4J = 0.9 Hz). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 164.3 (d, 1JCF = 251.7 Hz), 161.6, 159.4 (q, 2JCF = 42.7 Hz), 129.0 (d, 3JCF = 8.7 Hz), 123.5 (d, 4JCF = 3.5 Hz), 117.8 (q, 1JCF = 270.5 Hz), 116.4 (d, 2JCF = 22.1 Hz), 103.3 (q, 4JCF = 2.2 Hz). 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −65.4 (d, 3F, J = 0.8 Hz), -109.9--110.0 (m, 1F). NMR data are in agreement with those in the literature [70].

3-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)isoxazole (3f). Obtained from 1f (0.117 g, 0.503 mmol (A); 0.114 g, 0.49 mmol (B)). Pale yellow solid, m.p. 51–53 °C (Lit.: 61–62 °C [71]), yield 0.047 g (38%, (A)); 0.042 g (35%, (B)). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 7.74 (d, 2Н, 3J = 8.7 Hz), 7.46 (d, 2Н, 3J = 8.7 Hz), 6.98 (pseudo-d, 1H, 4J = 0.9 Hz). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 161.5, 159.5 (q, 2JCF = 42.6 Hz), 137.1, 129.5, 128.2, 125.7, 117.7 (q, 1JCF = 270.3 Hz), 103.3 (q, 4JCF = 2.0 Hz). 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −65.4 (d, 3F, J = 0.9 Hz). NMR data are in agreement with those in the literature [71].

3-(4-Bromophenyl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)isoxazole (3g). Obtained from 1g (0.140 g, 0.505 mmol (A); 0.143 g, 0.516 mmol (B)). Colorless solid, m.p. 71–73 °C (Lit.: 63–64 °C [71]), yield 0.053 g (36%, (A)); 0.051 g (34%, (B)). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 7.68 (d, 2Н, 3J = 8.6 Hz), 7.62 (d, 2Н, 3J = 8.6 Hz), 6.98 (pseudo-d, 1H, 4J = 0.8 Hz). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 161.7, 159.5 (q, 2JCF = 42.8 Hz), 132.5, 128.4, 126.2, 125.4, 117.7 (q, 1JCF = 270.4 Hz), 103.3 (q, 4JCF = 2.0 Hz). 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −65.4 (d, 3F, J = 0.6 Hz). NMR data are in agreement with those in the literature [72].

3-(4-(tert-Butyl)phenyl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)isoxazole (3h). Obtained from 1h (0.121 g, 0.476 mmol (A); 0.122 g, 0.48 mmol (B)). Pale yellow viscous oil, yield 0.041 g (32%, (A)); 0.033 g (26%, (B)). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 7.74 (d, 2Н, 3J = 8.7 Hz), 7.51 (d, 2Н, 3J = 8.7 Hz), 6.97 (pseudo-d, 1H, 4J = 0.9 Hz), 2.41 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 162.4, 159.0 (q, 2JCF = 42.4 Hz), 154.4, 126.7, 126.2, 124.4, 117.9 (q, 1JCF = 270.4 Hz), 103.4 (q, 4JCF = 2.0 Hz), 34.9, 31.1. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −65.4 (d, 3F, J = 0.6 Hz). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C14H15F3NO+: 270.1100; found: 270.1102.

5-(Trifluoromethyl)-3-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)isoxazole (3i). Obtained from 1i (0.134 g, 0.504 mmol (A); 0.137 g, 0.515 mmol (B)). Colorless solid, m.p. 55–57 °C (Lit.: 63–64 °C [73]), yield 0.067 g (47%, (A)); 0.070 g (48%, (B)). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 7.94 (d, 2Н, 3J = 8.2 Hz), 7.75 (d, 2Н, 3J = 8.2 Hz), 7.05 (pseudo-d, 1H, 4J = 0.8 Hz). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 161.5, 159.8 (q, 2JCF = 42.9 Hz), 132.8 (q, 2JCF = 32.8 Hz), 130.7, 127.3, 126.2 (q, 3JCF = 3.9 Hz), 123.6 (q, 1JCF = 272.4 Hz), 117.7 (q, 1JCF = 270.5 Hz), 103.5 (q, 4JCF = 2.0 Hz). 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −64.2 (d, 3F), −65.3 (d, 3F, J = 0.6 Hz). NMR data are in agreement with those in the literature [73].

3-(2,3-diHydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxin-6-yl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)isoxazole (3k). Obtained from 1k (0.128 g, 0.5 mmol (A); 0.126 g, 0.492 mmol (B)). Colorless solid, m.p. 102–104 °C, yield 0.026 g (19%, (A)); 0.021 g (16%, (B)). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 7.34 (d, 1Н, 4J = 2.1 Hz), 7.30 (dd, 1Н, 3J = 8.4 Hz, 4J = 2.1 Hz), 6.96 (d, 1Н, 3J = 8.4 Hz), 6.91 (pseudo-d, 1H, 4J = 0.9 Hz), 4.34–4.29 m, 4H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 162.0, 158.9 (q, 2JCF = 42.4 Hz), 145.9, 144.0, 120.5, 120.3, 118.0, 117.9 (q, 1JCF = 270.8 Hz), 116.0, 103.3 (q, 4JCF = 2.0 Hz), 64.5, 64.3. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −65.4 (d, 3F, 4J = 0.4 Hz). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C12H9F3NO3+: 272.0529; found: 272.0531.

3-(2-Chlorophenyl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)isoxazole (3l). Obtained from 1l (0.119 g, 0.512 mmol (A); 0.123 g, 0.529 mmol (B)). Pale yellow oil, yield 0.037 g (29%, (A)); 0.047 g (36%, (B)). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 7.75 (dd, 1Н, 3J = 7.7 Hz, 4J = 1.8 Hz), 7.52 (dd, 1Н, 3J = 7.7 Hz, 4J = 1.4 Hz), 7.45 (td, 1H, 3J = 7.7 Hz, 4J = 1.8 Hz), 7.39 (td, 1H, 3J = 7.7 Hz, 4J = 1.4 Hz), 7.19 (pseudo-d, 1H, 4J = 0.8 Hz). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 161.2, 158.5 (q, 2JCF = 42.6 Hz), 132.9, 131.7, 131.1, 130.6, 127.4, 126.5, 117.8 (q, 1JCF = 270.3 Hz), 106.6 (q, 4JCF = 2.0 Hz). 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −65.2 (d, 3F, 4J = 0.9 Hz). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H3O]+ calcd. for C10H8[35Cl]F3NO2+: 266.0190; found: 266.0190; calcd. for C10H8[37Cl]F3NO2+: 268.0161; found: 268.0156.

3-(2-Methoxyphenyl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)isoxazole (3m). Obtained from 1m (0.113 g, 0.502 mmol (A); 0.108 g, 0.48 mmol (B)). Colorless oil, yield 0.026 g (21%, (A)); 0.030 g (26%, (B)). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 7.91 (dd, 1Н, 3J = 7.7 Hz, 4J = 1.7 Hz), 7.48–7.44 (m, 1Н), 7.22 (s, 1H), 7.06 (pseudo-t, 1H, 3J = 7.5 Hz), 7.02 (d, 1H, 3J = 8.4 Hz), 3.92 (s, 1H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 160.1, 157.9 (q, 2JCF = 42.2 Hz), 157.2, 132.1, 129.4, 121.1, 118.1 (q, 1JCF = 270.0 Hz), 116.1, 111.4, 106.9 (q, 4JCF = 2.0 Hz), 55.6. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −65.3 (d, 3F, 4J = 0.9 Hz). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C11H9F3NO2+: 244.0580; found: 244.0581.

3-Octyl-5-(trifluoromethyl)isoxazole (3o). Obtained from 1o (0.118 g, 0.504 mmol (A); 0.130 g, 0.556 mmol (B)). Colorless oil, yield 0.041 g (32%, (A)); 0.046 g (33%, (B)). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 6.53 (pseudo-d, 1H, 4J = 0.7 Hz), 2.71 (t, 2Н, 3J = 7.7 Hz), 1.70–1.63 (m, 2H), 1.39–1.19 (m, 10H), 0.88–0.85 (m, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 164.2, 158.4 (q, 2JCF = 42.4 Hz), 118.0 (q, 1JCF = 270.2 Hz), 104.9 (q, 4JCF = 1.9 Hz), 31.8, 29.14, 29.08, 29.04, 28.0, 25.8, 22.6, 14.1. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −65.4 (d, 3F, 4J = 0.9 Hz). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C12H19F3NO+: 250.14133; found: 250.141.

3-(Phenoxymethyl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)isoxazole (3p). Obtained from 1p (0.117 g, 0.52 mmol (A); 0.125 g, 0.556 mmol (B)). Pale yellow oil, yield 0.065 g (51%, (A)); 0.064 g (47%, (B)). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 7.36–7.30 (m, 2Н), 7.05–7.01 (m, 1Н), 6.99–6.96 (m, 2Н), 6.86 (pseudo-d, 1H, 4J = 0.4 Hz), 5.20 (s, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 161.2, 159.2 (q, 2JCF = 42.8 Hz), 157.6, 129.7, 122.0, 117.7 (q, 1JCF = 270.5 Hz), 114.6, 104.9 (q, 4JCF = 2.0 Hz), 61.0. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −65.2 (d, 3F, 4J = 0.6 Hz). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C11H9F3NO2+: 244.0580; found: 244.0585.

Synthesis of amides 4–6 (general procedure). A 4 mL vial with a screw cap was charged with 2,2,2-trifluoro-1-(5-phenyl-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)ethanone (2a). (0.054–0.059 g, 0.224–0.245 mmol) and the corresponding amine (0.189–0.230 g, ~2.7 mmol, ~12 equiv.) The reaction mixture was heated at 90 °C for 2.5–8 h using a magnetic stirrer while heating, and then, the volatiles were evaporated in vacuo. The residue was passed through a short silica gel pad using CH2Cl2 followed by CH2Cl2 -MeOH (100:1) as eluents. The evaporation of volatiles produced corresponding pure amide 4–6.

(5-Phenyl-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)(pyrrolidin-1-yl)methanone (4). Obtained from 2a (0.054 g, 0.224 mmol) and pyrrolidine (0.189 g, 2.66 mmol) by heating for 2.5 h. Pale brown solid, m.p. 162–164 °C, yield 0.046 g (85%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 7.76–7.65 (m, 2H), 7.35–7.25 (m, 3H), 3.67 (t, 2H, 3J = 6.9 Hz), 3.38 (t, 2H, 3J = 6.9 Hz), 1.92–1.85 (m, 2H), 1.85–1.74 (m, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 162.5, 142.8, 138.0, 128.9, 128.6, 127.6, 48.6, 46.4, 25.9, 24.2. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+Na]+ calcd. for C13H14N4ONa+: 265.1060; found: 265.1068. IR (ν, cm−1): 1595 (C=O).

(5-Phenyl-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)(piperidin-1-yl)methanone (5). Obtained from 2a (0.053 g, 0.220 mmol) and piperidine (0.228 g, 2.68 mmol) by heating for 8 h. Pale brown solid, m.p. 123–125 °C, yield 0.033 g (58%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 7.66 (dd, 2H, 3J = 6.9 Hz, 4J = 1.9 Hz), 7.41–7.38 (m, 3H), 3.82–3.62 (m, 2H), 3.28–3.10 (m, 2H), 1.68–1.48 (m, 4H), 1.34–1.21 (m, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 163.0, 142.9, 137.4, 128.9, 128.8, 128.5, 127.3, 48.3, 43.3, 26.0, 25.4, 24.3. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C14H17N4O+: 257.1397; found: 257.1403. IR (ν, cm−1): 1592 (C=O).

Morpholino(5-phenyl-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methanone (6). Obtained from 2a (0.053 g, 0.220 mmol) and morpholine (0.230 g, 2.64 mmol) by heating for 8 h. Pale brown viscous sticky mass, yield 0.027 g (48%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 7.73–7.59 (m, 2H), 7.44–7.34 (m, 3H), 3.87–3.79 (m, 2H), 3.77–3.70 (m, 2H), 3.47–3.39 (m, 2H), 3.39–3.27 (m, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 163.0, 141.6, 136.9, 129.3, 128.9, 127.5, 127.3, 66.53, 66.48, 47.5, 42.7. HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C13H15N4O2+: 259.1190; found: 259.1190. IR (ν, cm−1): 1604 (C=O).

Synthesis of triazoles 7–10 (general procedure). A 4 mL vial with a screw cap was charged with 2,2,2-trifluoro-1-(5-phenyl-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)ethanone (2a) (0.120 g, 0.498 mmol), DMF (1 mL), Na2CO3 (0.079 g, 0.745 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), and corresponding alkylating reagent (0.548 mmol, ~1.1 equiv.) The reaction mixture was stirred overnight, poured into water (20 mL) and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic phase was washed with water (20 mL) and dried over Na2SO4, and then, the volatiles were evaporated in vacuo. The residue was purified via column chromatography on silica gel using appropriate mixtures of hexane and CH2Cl2 as eluents.

1-(2-Benzyl-5-phenyl-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)-2,2,2-trifluoroethanone (7). Obtained from 2a (0.120 g, 0.498 mmol) and benzylbromide (0.094 g, 0.550 mmol). Purified using gradient elution with hexane-CH2Cl2 (3:1) followed by hexane-CH2Cl2 (1:1) and CH2Cl2. Beige oil, yield 0.113 g (69%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 7.96–7.86 (m, 2H), 7.53–7.44 (m, 5H), 7.44–7.36(m, 3H), 5.71 (s, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.2 (q, 2JCF = 37.0 Hz), 152.7, 136.4, 133.5, 130.1, 129.1, 129.0, 128.9, 128.40, 128.35, 128.2, 116.3 (q, 1JCF = 290.7 Hz), 59.9. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −74.9 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C17H13F3N3O+: 332.1005; found: 332.1005. IR (ν, cm−1): 1723 (C=O).

1-(1-Benzyl-5-phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)-2,2,2-trifluoroethanone (8). Obtained from 2a as an admixture (81:19) in the synthesis of 7. Beige thick oil, yield 0.026 g (15%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 7.58–7.52 (m, 1H), 7.51–7.46 (m, 2H), 7.31–7.25 (m, 3H), 7.24–7.20 (m, 2H), 7.08–7.00 (m, 2H), 5.46 (s, 2Н). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.2 (q, 2JCF = 37.3 Hz), 143.9, 138.1, 133.9, 130.9, 129.4, 129.0, 128.9, 128.7, 127.7, 124.4, 116.1 (q, 1JCF = 290.6 Hz), 52.2. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −75.4 (s, 3F). NMR data are in agreement with those in the literature [54].

1-(2-(2,4-Dinitrophenyl)-5-phenyl-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)-2,2,2-trifluoroethanone (9). Obtained from 2a (0.057 g, 0.237 mmol) and 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (0.049 g, 0.263 mmol). Purified using gradient elution with hexane-CH2Cl2 (3:1) followed by hexane-CH2Cl2 (1:1). Pale yellow powder, m.p. 132–134 °C, yield 0.079 g (82%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 8.67 (d, 1Н, 4J = 2.4 Hz), 8.56 (dd, 1Н, 3J = 8.9 Hz, 4J = 2.4 Hz), 8.31 (d, 1Н, 3J = 8.9 Hz), 7.83 (dd, 2H, 3J = 7.7 Hz, 4J = 1.7 Hz), 7.49–7.40 (m, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 173.7 (q, 2JCF = 38.2 Hz), 153.8, 147.1, 142.8, 138.7, 134.1, 130.8, 129.0, 128.4, 127.4, 126.4, 120.7, 115.6 (q, 1JCF = 290.5 Hz). 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −75.0 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C16H9F3N5O5+: 408.0550; found: 408.0549. IR (ν, cm−1): 1738 (C=O); 1545, 1540, 1349, 1335 (NO2).

2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(5-phenyl-2-tosyl-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)ethanone (10). Obtained from 2a (0.060 g, 0.249 mmol) and 4-toluenesulfonyl chloride (0.052 g, 0.274 mmol). Purified using gradient elution with hexane-CH2Cl2 (1:1) followed by CH2Cl2.White crystals, m.p. 156–160 °C, yield 0.073 g (74%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 8.08 (d, 2Н, 3J = 8.4 Hz), 7.83 (dd, 2Н, 3J = 7.9 Hz, 4J = 1.4 Hz) 7.52–7.39 (m, 5H), 2.46 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.5 (q, 2JCF = 37.9 Hz), 153.4, 148.1, 138.6, 131.6, 130.8, 130.6, 129.6, 129.3, 128.5, 126.9, 115.8 (q, 1JCF = 290.5 Hz), 21.9. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −75.2 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C17H13F3N3O3S+: 396.0324; found: 396.0626. IR (ν, cm−1): 1731 (C=O).

Synthesis of 1-(2,5-diphenyl-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)-2,2,2-trifluoroethanone (11). A 25 mL round-bottomed flask was charged with 2,2,2-trifluoro-1-(5-phenyl-2H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)ethanone (2a) (0.062 g, 0.257 mmol), DMSO (1.5 mL), PhB(OH)2 (0.047 g, 0.385 mmol, 1.5 equiv.) and Cu(OAc)2×H2O (0.0051, 0.257 mmol, 0.1 equiv.) The reaction mixture was heated at 100 °C for 5 h in air using a magnetic stirrer while heating. The reaction mixture was poured into water (20 mL) and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 20 mL). Combined organic phase was washed with water (20 mL) and dried over Na2SO4, and then, the volatiles were evaporated in vacuo. The residue was purified via column chromatography on silica gel using gradient elution with hexane-CH2Cl2 (3:1) followed by hexane-CH2Cl2 (1:1) as eluents. Colorless crystals, m.p. 93–95 °C, yield 0.032 g (50%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400.1 MHz): δ 8.28–8.18 (m, 2H), 8.03–7.95 (m, 2H), 7.59–7.46 (m, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100.6 MHz): δ 174.4 (q, 2JCF = 37.5 Hz), 152.9, 138.8, 137.1, 130.4, 129.6, 129.4, 129.2, 128.5, 128.1, 119.7, 116.3 (q, 1JCF = 290.9 Hz). 19F NMR (CDCl3, 376.5 MHz): δ −74.9 (s, 3F). HRMS (ESI-TOF): m/z [M+H]+ calcd. for C16H11F3N3O+: 318.0849; found: 318.0851. IR (ν, cm−1): 1716 (C=O).

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, we determined a green approach towards 4-trifluoroacetyltriazoles or 5-CF3-isoxazoles based on the reaction of CF3-ynones with NaN3 in EtOH. The reaction pathway could be totally controlled by the addition of acid to the reaction mixture. Without the addition of any acids, the reaction gave 4-trifluoroacetyltriazoles in isolated yields of up to 85%. In the presence of acid, the reaction of CF3-ynones with NaN3 in EtOH or heptane led to 5-CF3-isoxazoles in good yields. The utility of the elaborated method was confirmed by gram-scale synthesis. A remarkably low E-factor was demonstrated. Several reactions of prepared 4-trifluoroacetyltriazoles were investigated, and the high synthetic utility of these products was demonstrated.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (grant no. 18-13-00136). The authors acknowledge Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., MS Analytica (Moscow, Russia) and A. Makarov for providing mass spectrometry equipment for this work. DFT calculations were performed by M.S. Nechaev as part of the State Program of TIPS RAS.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms232314522/s1. Copies of all 1H, 13C and 19F NMR spectra, and computational details.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M.M.; methodology, V.M.M.; formal analysis, V.M.M.; investigation, V.M.M., Z.A.S. and M.S.N.; writing—original draft preparation, V.M.M.; writing—review and editing, V.M.M., Z.A.S., M.S.N. and V.G.N.; visualization, V.M.M.; supervision, V.M.M.; project administration, V.G.N.; funding acquisition, V.G.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation, grant number 18-13-00136.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Liang T., Neumann C.N., Ritter T. Introduction of fluorine and fluorine-containing functional groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:8214–8264. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang X., Wu T., Phipps R.J., Toste F.D. Advances in catalytic enantioselective fluorination, mono-, di-, and trifluoromethylation, and trifluoromethylthiolation reactions. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:826–870. doi: 10.1021/cr500277b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahrens T., Kohlmann J., Ahrens M., Braun T. Functionalization of fluorinated molecules by transition metal mediated C−F bond activation to access fluorinated building blocks. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:931–972. doi: 10.1021/cr500257c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yerien D.E., Barata-Vallejo S., Postigo A. Difluoromethylation reactions of organic compounds. Chem. Eur. J. 2017;23:14676–14701. doi: 10.1002/chem.201702311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirsch P. Modern Fluoroorganic Chemistry: Synthesis, Reactivity, Applications. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uneyama K. Organofluorine Chemistry. Blackwell Publishing; Oxford, UK: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Theodoridis G. Fluorine-containing agrochemicals: An overview of recent developments. In: Tressaud A., editor. Advances in Fluorine Science. Volume 2. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2006. pp. 121–175. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bégué J.P., Bonnet-Delpon D. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry of Fluorine John. Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tressaud A., Haufe G., editors. Fluorine and Health. Molecular Imaging, Biomedical Materials and Pharmaceuticals. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2008. pp. 553–778. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soloshonok V.A., Mikami K., Yamazaki T., Welch J.T., Honek J.F., editors. Current Fluoroorganic Chemistry. New Synthetic Directions, Technologies, Materials, and Biological Applications. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC, USA: 2006. (ACS Symposium Series 949). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meanwell N.A. Fluorine and fluorinated motifs in the design and application of bioisosteres for drug design. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:5822–5880. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gillis E.P., Eastman K.J., Hill M.D., Donnelly D.J., Meanwell N.A. Applications of fluorine in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:8315–8359. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu W., Wang J., Wang S., Gu Z., Aceña J.L., Izawa K., Liu H., Soloshonok V.A. Recent advances in the trifluoromethylation methodology and new CF3-containing drugs. J. Fluorine Chem. 2014;167:37–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2014.06.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Purser S., Moore P.R., Swallow S., Gouverneur V. Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:320–330. doi: 10.1039/B610213C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagmann W.K. The many roles for fluorine in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:4359–4369. doi: 10.1021/jm800219f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou Y., Wang J., Gu Z., Wang S., Zhu W., Aceña J.L., Soloshonok V.A., Izawa K., Liu H. Next generation of fluorine containing pharmaceuticals, compounds currently in phase II−III clinical trials of major pharmaceutical companies: New structural trends and therapeutic areas. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:422–518. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J., Sánchez-Roselló M., Aceña J.L., del Pozo C., Sorochinsky A.E., Fustero S., Soloshonok V.A., Liu H. Fluorine in pharmaceutical industry: Fluorine-containing drugs introduced to the market in the last decade (2001–2011) Chem. Rev. 2014;114:2432–2506. doi: 10.1021/cr4002879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ilardi E.A., Vitaku E., Njardarson J.T. Data-mining for sulfur and fluorine: An evaluation of pharmaceuticals to reveal opportunities for drug design and discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:2832–2842. doi: 10.1021/jm401375q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue M., Sumii Y., Shibata N. Contribution of Organofluorine Compounds to Pharmaceuticals. ACS Omega. 2020;5:10633–10640. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c00830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeschke P. The unique role of fluorine in the design of active ingredients for modern crop protection. ChemBioChem. 2004;5:570–589. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeschke P. The unique role of halogen substituents in the design of modern agrochemicals. Pest Manage. Sci. 2010;66:10–27. doi: 10.1002/ps.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujiwara T., O’Hagan D. Successful fluorine-containing herbicide agrochemicals. J. Fluorine Chem. 2014;167:16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2014.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeschke P. Latest generation of halogen-containing pesticides. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017;73:1053–1056. doi: 10.1002/ps.4540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor A.P., Robinson R.P., Fobian Y.M., Blakemore D.C., Jones L.H., Fadeyi O. Modern advances in heterocyclic chemistry in drug discovery. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016;14:6611–6637. doi: 10.1039/C6OB00936K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baumann M., Baxendale I.R., Ley S.V., Nikbin N. An overview of the key routes to the best selling 5-membered ring heterocyclic pharmaceuticals. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2011;7:442–495. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.7.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baumann M., Baxendale I.R. An overview of the synthetic routes to the best selling drugs containing 6-membered heterocycles. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013;9:2265–2319. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.9.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gribble G.W., Joule J.A., editors. Progress in Heterocyclic Chemistry. Volume 24 Academic Press, Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joule J.A., Mills K. Heterocyclic Chemistry at a Glance. Blackwell Publishing; Oxford, UK: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rulev A.Y., Romanov A.R. Unsaturated polyfluoroalkyl ketones in the synthesis of nitrogen-bearing heterocycles. RSC Adv. 2016;6:1984–1998. doi: 10.1039/C5RA23759A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vitaku E., Smith D.T., Njardarson J.T. Analysis of the structural diversity, substitution patterns, and frequency of nitrogen heterocycles among U.S. FDA approved pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:10257–10274. doi: 10.1021/jm501100b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nenajdenko V.G., editor. Fluorine in Heterocyclic Chemistry. Volume 1. Springer; Heidelberg, Germany: 2014. p. 681. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petrov V.A., editor. Fluorinated Heterocyclic Compounds: Synthesis, Chemistry, and Applications. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gakh A., Kirk K.L., editors. Fluorinated Heterocycles. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serafini M., Pirali T., Tron G.C. Chapter Three—Click 1,2,3-triazoles in drug discovery and development: From the flask to the clinic? in Applications of Heterocycles in the Design of Drugs and Agricultural Products Edited. In: Meanwell N.A., Lolli M.L., editors. Advances in Heterocyclic Chemistry. Volume 134. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA, USA: 2021. pp. 101–148. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalavadiyaa P.L., Kapuparaa V.H., Gojiyaa D.G., Bhatta T.D., Hadiyala S.D., Joshia H.S. Ultrasonic-assisted synthesis of pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-ol tethered with 1,2,3-triazoles and their anticancer activity. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2020;46:803–813. doi: 10.1134/S1068162020050106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan W., Wang Q., Lin Q., Li M., Petersen J.L., Shi X. N-2-Aryl-1,2,3-triazoles: A novel class of UV/Blue-Light-Emitting fluorophores with tunable optical properties. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:5011–5018. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsyrenova B., Nenajdenko V. Synthesis and spectral study of a new family of 2,5-diaryltriazoles having restricted rotation of the 5-aryl substituent. Molecules. 2020;25:480. doi: 10.3390/molecules25030480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsyrenova B., Khrustalev V., Nenajdenko V. 2H-bis-1,2,3-triazolo-isoquinoline: Design, synthesis, and photophysical study. J. Org. Chem. 2020;85:7024–7035. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.0c00263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agalave S.G., Maujan S.R., Pore V.S. Click Chemistry: 1,2,3-Triazoles as Pharmacophores. Chem. Asian J. 2011;6:2696–2718. doi: 10.1002/asia.201100432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo H.-Y., Chen Z.-A., Shen Q.-K., Quan Z.-S. Application of triazoles in the structural modification of natural products. J. Enzim. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2021;36:1115–1144. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2021.1890066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rani A., Singh G., Singh A., Maqbool U., Kaur G., Singh J. CuAAC-ensembled 1,2,3-triazole-linked isosteres as pharmacophores in drug discovery: Review. RSC Adv. 2020;10:5610–5635. doi: 10.1039/C9RA09510A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kharb R., Sharma P.C., Yar M.S. Pharmacological significance of triazole scaffold. J. Enzim. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2011;26:1–21. doi: 10.3109/14756360903524304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gin A., Dilay L., Karlowsky J.A., Walkty A., Rubinstein E., Zhanel G.G. Piperacillin-tazobactam: A beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combination. Expert. Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2007;5:365–383. doi: 10.1586/14787210.5.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arroyo S. Rufinamide. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palasz A., Lapray D., Peyron C., Rojczyk-Golebiewska E., Skowronek R., Markowski G., Czajkowska B., Krzystanek M., Wiaderkiewicz R. Dual orexin receptor antagonists—promising agents in the treatment of sleep disorders. Int. J. Neuropsychoph. 2014;17:157–168. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713000552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Latha M.S., Martis J., Shobha V., Sham Shinde R., Bangera S., Krishnankutty B., Bellary S., Varughese S., Rao P., Naveen Kumar B.R. Sunscreening agents: A review. J. Clin. Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:16–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gonzalez S., Fernandez-Lorente M., Gilaberte-Calzada Y. The latest on skin photoprotection. Clin. Dermatol. 2008;26:614–626. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roch C., Bergamini G., Steiner M.A., Clozel M. Nonclinical pharmacology of daridorexant: A new dual orexin receptor antagonist for the treatment of insomnia. Psychopharmacology. 2021;238:2693–2708. doi: 10.1007/s00213-021-05954-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Druzhinin S.V., Balenkova E.S., Nenajdenko V.G. Recent advances in the chemistry of alpha,beta-unsaturated trifluoromethylketones. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:7753–7808. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.04.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang C. Synthesis of trifluoromethyl or trifluoroacetyl substituted heterocyclic compounds from trifluoromethyl-α,β-ynones. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. Taip. 2022;69:594–603. doi: 10.1002/jccs.202100544. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Romanov A.R., Rulev A.Y., Ushakov I.A., Muzalevskiy V.M., Nenajdenko V.G. Synthesis of trifluoromethylated [1,4]diazepines from 1,1,1-trifluoroalk-3-yn-2-jnes. Mendeleev Commun. 2014;24:269–271. doi: 10.1016/j.mencom.2014.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Romanov A.R., Rulev A.Y., Ushakov I.A., Muzalevskiy V.M., Nenajdenko V.G. One-pot, atom and step economy (PASE) assembly of trifluoromethylated pyrimidines from CF3 –ynones. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017:4121–4129. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201700727. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muzalevskiy V.M., Iskandarov A.A., Nenajdenko V.G. Reaction of CF3-ynones with methyl thioglycolate. Regioselective synthesis of 3-CF3-thiophene derivatives. J. Fluorine Chem. 2018;214:13–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2018.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muzalevskiy V.M., Mamedzade M.N., Chertkov V.A., Bakulev V.A., Nenajdenko V.G. Reaction of CF3 -ynones with azides. An efficient regioselective and metal-free route to 4-trifluoroacetyl-1,2,3-triazoles. Mendeleev Commun. 2018;28:17–19. doi: 10.1016/j.mencom.2018.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Muzalevskiy V.M., Iskandarov A.A., Nenajdenko V.G. Synthesis of dibromo substituted CF3-enones and their reactions with N-nucleophiles. Mendeleev Commun. 2014;24:342–344. doi: 10.1016/j.mencom.2014.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muzalevskiy V.M., Rulev A.Y., Romanov A.R., Kondrashov E.V., Ushakov I.A., Chertkov V.A., Nenajdenko V.G. Selective, metal-free approach to 3- or 5-CF3-pyrazoles: Solvent switchable reaction of CF3-ynones with hydrazines. J. Org. Chem. 2017;82:7200–7214. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.7b00774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Topchiy M.A., Zharkova D.A., Asachenko A.F., Muzalevskiy V.M., Chertkov V.A., Nenajdenko V.G., Nechaev M.S. Mild and regioselective synthesis of 3-CF3-pyrazoles by the AgOTf-catalysed reaction of CF3-ynones with hydrazines. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018;2018:3750–3755. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201800208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trofimov B.A., Belyaeva K.V., Nikitina L.P., Afonin A.V., Vashchenko A.V., Muzalevskiy V.M., Nenajdenko V.G. Metal-free stereoselective annulation of quinolines with trifluoroacetylacetylenes and water: An access to fluorinated oxazinoquinolines. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:2268–2271. doi: 10.1039/C7CC09725E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muzalevskiy V.M., Belyaeva K.V., Trofimov B.A., Nenajdenko V.G. Diastereoselective synthesis of CF3-oxazinoquinolines in water. Green Chem. 2019;21:6353–6360. doi: 10.1039/C9GC03044A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Belyaeva K.V., Nikitina L.P., Afonin A.V., Vashchenko A.V., Muzalevskiy V.M., Nenajdenko V.G., Trofimov B.A. Catalyst-free 1:2 annulation of quinolines with trifluoroacetylacetylenes: An access to functionalized oxazinoquinolines. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018;16:8038–8041. doi: 10.1039/C8OB02379D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Muzalevskiy V.M., Sizova Z.A., Belyaeva K.V., Trofimov B.A., Nenajdenko V.G. One-pot metal-free synthesis of 3-CF3-1,3-oxazinopyridines by reaction of pyridines with CF3CO-acetylenes. Molecules. 2019;24:3594. doi: 10.3390/molecules24193594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Muzalevskiy V.M., Belyaeva K.V., Trofimov B.A., Nenajdenko V.G. Organometal-free arylation and arylation/trifluoroacetylation of quinolines by their reaction with CF3-ynones and base-induced rearrangement. J. Org. Chem. 2020;85:9993–10006. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.0c01277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hansen L.D., West B.D., Baca E.J., Blank C.L. Thermodynamics of proton ionization from some substituted 1,2,3-triazoles in dilute aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968;90:6588–6892. doi: 10.1021/ja01026a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sysak A., Obminska-Mrukowicz B. Isoxazole ring as a useful scaffold in a search for new therapeutic agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;137:292–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhu J., Mo J., Lin H.-Z., Chen Y., Sun H.-P. The recent progress of isoxazole in medicinal chemistry. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018;26:3065–3075. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Agrawal N., Mishra P. The synthetic and therapeutic expedition of isoxazole and its analogs. Med. Chem. Res. 2018;27:1309–1344. doi: 10.1007/s00044-018-2152-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kozuch S., Shaik S. How to conceptualize catalytic cycles? The energetic span model. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011;44:101–110. doi: 10.1021/ar1000956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Muzalevskiy V.M., Sizova Z.A., Duisenov A.I., Shastin A.V., Nenajdenko V.G. Efficient multi gram approach to acetylenes and CF3-ynones starting from dichloroalkenes prepared by catalytic olefination reaction (COR) Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020;2020:4161–4166. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.202000531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Khairnar P.V., Lung T.-H., Lin Y.-J., Wu C.-Y., Koppolu S.R., Edukondalu A., Karanam P., Lin W. An intramolecular Wittig approach toward heteroarenes: Synthesis of pyrazoles, isoxazoles, and chromenone-oximes. Org. Lett. 2019;21:4219–4223. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chalyk B.A., Hrebeniuk K.V., Fil Y.V., Gavrilenko K.S., Rozhenko A.B., Vashchenko B.V., Borysov O.V., Biitseva A.V., Lebed P.S., Bakanovych I., et al. Synthesis of 5-(fluoroalkyl)isoxazole building blocks by regioselective reactions of functionalized halogenoximes. J. Org. Chem. 2019;84:15877–15899. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.9b02264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martins M.A.P., Siqueira G.M., Bastos G.P., Bonacorso H.G., Zanatta N. Haloacetylated enol ethers. 7 †. Synthesis of 3-aryl-5-trihalomethylisoxazoles and 3-aryl-5-hydroxy-5-trihalomethyl-4,5-dihydroisoxazoles. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1996;33:1619–1622. doi: 10.1002/jhet.5570330612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kumar V., Aggarwal R., Singh S.P. The reaction of hydroxylamine with aryl trifluoromethyl-β-diketones: Synthesis of 5-hydroxy-5-trifluoromethyl-Δ2-isoxazolines and their dehydration to 5-trifluoromethylisoxazoles. J. Fluor. Chem. 2006;127:880–888. doi: 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2006.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hamper B.C., Leschinsky K.L. Reaction of benzohydroximinoyl chlorides and β-(trifluoromethyl)-acetylenic esters: Synthesis of regioisomeric (trifluoromethyl)-isoxazolecarboxylate esters and oxime addition products. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2009;40:575–583. doi: 10.1002/jhet.5570400404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.