Abstract

Background

Pressure ulcers affect approximately 10% of people in hospitals and older people are at highest risk. A correlation between inadequate nutritional intake and the development of pressure ulcers has been suggested by several studies, but the results have been inconsistent.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of enteral and parenteral nutrition on the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers.

Search methods

In March 2014, for this first update, we searched The Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Trials Register, the Cochrane Central register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library), the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (The Cochrane Library), the Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA) (The Cochrane Library), the Cochrane Methodology Register (The Cochrane Library), NHS Economic Evaluation Database (The Cochrane Library), Ovid Medline, Ovid Embase and EBSCO CINAHL. No date, language or publication status limits were applied.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the effects of enteral or parenteral nutrition on the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers, which measured the incidence of new ulcers, ulcer healing or changes in pressure ulcer severity. There were no restrictions on types of patient, setting, date, publication status or language.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened for inclusion, and disagreement was resolved by discussion. Two review authors independently extracted data and assessed quality using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias.

Main results

We included 23 RCTs, many were small (between 9 and 4023 participants, median 88) and at high risk of bias.

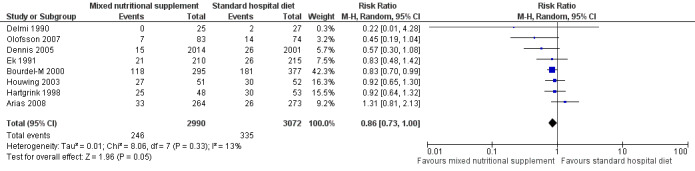

Eleven trials compared a combination of nutritional supplements, consisting of a minimum of energy and protein in different dosages, for the prevention of pressure ulcers. A meta‐analysis of eight trials (6062 participants) that compared the effects of mixed nutritional supplements with standard hospital diet found no clear evidence of an effect of supplementation on pressure ulcer development (pooled RR 0.86; 95% CI 0.73 to 1.00; P value 0.05; I2 = 13%, random effects). This outcome is at unclear or high risk of bias.

Fourteen trials evaluated the effects of nutritional supplements on the healing of existing pressure ulcers: seven trials examined mixed nutritional supplements, three the effects of proteins, two trials examined zinc, and two studies examined ascorbic acid. The included trials were heterogeneous with regard to participants, interventions, comparisons and outcomes and meta‐analysis was not appropriate. There was no clear evidence of an improvement in pressure ulcer healing from the nutritional supplements evaluated in any of these individual studies.

Authors' conclusions

There is currently no clear evidence of a benefit associated with nutritional interventions for either the prevention or treatment of pressure ulcers. Further trials of high methodological quality are necessary.

Plain language summary

Dietary supplementation for preventing and treating pressure ulcers

Background Pressure ulcers (also called bed sores) are wounds caused by pressure at the weight‐bearing, bony points of immobilised people (such as hips, heels and elbows). Poor nutritional status, or dehydration, may weaken the skin and make people more vulnerable to developing pressure ulcers. Once a pressure ulcer has developed, it can become very large and difficult to heal.

Review Question We wanted to find out whether changing the diet (for example by giving supplements) could prevent the development of pressure ulcers. We also wanted to find out if dietary changes could help heal pressure ulcers that had already occurred.

The review of trials found that there is no clear evidence that nutritional interventions reduce the number of people who develop pressure ulcers or help the healing of existing pressure ulcers. More research is needed.

Background

A pressure ulcer ‐ also known as a pressure sore, decubitus ulcer or bedsore ‐ is defined as "localized injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence, as a result of pressure, or pressure in combination with shear." Shear pressure occurs when layers of skin are forced to slide over one another or over deeper layers of tissue, for example, if a patient slides down the bed (EPUAP and NPUAP 2009a). Friction is also thought to contribute. Applied pressure affects cellular metabolism by decreasing or obliterating tissue circulation, resulting in insufficient blood flow to the skin and underlying tissues, and causing tissue ischaemia (deficient blood supply). Elderly patients with decreased mobility, limited mental status and increased skin friction and shear may have a higher risk of developing a pressure ulcer (Perneger 2002). Schoonhoven 2006 found that independent predictors of pressure ulcers were increased age, reduced (<54kg) or increased (>95kg) weight at admission, abnormal appearance of the skin, friction and shear, and surgery planned for the coming week (Schoonhoven 2006).

Pressure ulcer classification systems allow a consistent description for the severity and level of tissue injury of a pressure ulcer. The words "stage", "grade", and "category" may be used interchangeably to describe the levels of soft‐tissue injury (EPUAP and NPUAP 2009a). The classification includes Grades 1 through to 4. Grade 1 reflects persistent non‐blanching erythema (redness) of the skin, Grade 2 involves partial thickness skin loss (epidermis and dermis), Grade 3 reflects full thickness skin loss involving damage or necrosis of subcutaneous tissue whereas in Grade 4 the damage extends to the underlying bone, tendon or joint capsule (EPUAP and NPUAP 2009a).

Pressure ulcers affect a significant minority of people in hospitals and other care facilities. An economic analysis of the impact of pressure ulcer care in a 252‐bed elderly care unit in Glasgow reported that 41% of the patients suffered from some pressure damage. The incidence data were reported to show that 45% of these pressure ulcers were potentially preventable (Thomson 1999). The overall prevalence of pressure ulcers in all facilities in the United States was 12.3% in 2009, with 5% of the pressure ulcers considered to be facility‐associated. When Grade I ulcers were excluded, overall pressure ulcer prevalence was 9% (VanGilder 2009). A Swiss study showed an incidence of pressure ulcers (Grade 2 or more) of 10% in acute hospitals (Perneger 1998). Schoonhoven 2002 reported a weekly incidence of patients with Grade 2 pressure ulcers of 6.2% (95% confidence interval (CI) 5.2% to 7.2%) in two large Dutch hospitals. In 2001, a study of 3012 patients (mean age 65 years) from 165 wards in 11 hospitals in Germany estimated the prevalence of pressure ulcers as 24% to 39% (Dassen 2001). Between 2002 and 2008 the pressure ulcer prevalence rates in German long‐term care facilities decreased from 12.5% to 5.0%, while non‐blanchable erythema decreased from 6.6% to 3.5% (Lahmann 2010). The authors hypothesised that this decrease was due to more effective treatment strategies and better prevention. Another retrospective analysis of clinical records from 414 cancer patients admitted over six months for palliative care showed a prevalence of pressure ulcers of 22.9%, and an incidence of 6.7% (Hendrichova 2010).

The prevention of pressure ulcers involves a number of strategies designed to address both extrinsic factors, e.g. reducing the pressure duration or magnitude at the skin surface through repositioning or use of pressure relieving cushions or mattresses, and intrinsic factors, e.g. the ability of the patient's skin to remain intact and resist pressure damage by optimising hydration, circulation and nutrition. There is some evidence that the incidence and severity of pressure ulceration increases with poor nutrition (Bergstrom 1992;Berlowitz 1989). Decreased calorie intake, dehydration, and a drop in serum albumin levels may decrease the tolerance of skin and underlying tissue to pressure, friction, and shearing force, thus increasing the risk of skin breakdown and reducing wound healing ability (Mueller 2001). Serum albumin is commonly used as a measure of the amount of protein available in the blood for healing. The combination of low energy and low protein intake is often described as protein‐calorie or protein‐energy malnutrition.

A few studies have suggested a correlation between protein‐calorie malnutrition and pressure ulcers (Breslow 1991a; Finucane 1995; Strauss 1996). The effects of special diets in preventing and treating pressure ulcers has not yet been examined sufficiently, although many risk assessment tools include nutritional status (e.g. Braden 1994; Gosnell 1989). Nevertheless, there is a consensus that nutrition is an important factor, as shown by its incorporation in a variety of guidelines, e.g. the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) Pressure Ulcer Prevention Guidelines, which state, "Consider the impact of the following factors on an individual’s risk of pressure ulcer development: a) nutritional indicators . . ."; and "Screen and assess the nutritional status of every individual at risk of pressure ulcers in each health care setting", and urge care‐providers to, "Provide sufficient calories . . . provide adequate protein . . . provide and encourage adequate daily fluid intake for hydration . . . provide adequate vitamins and minerals" (EPUAP and NPUAP 2009a; EPUAP and NPUAP 2009b).

Enteral nutrition is nourishment such as a special diet, or supplements to normal eating or tube feeding, that are given via the mouth or by tube and absorbed through the digestive system. Parenteral nutrition is nourishment such as intravenous infusion or intramuscular injection given via the bloodstream. It is unclear if the route of administration (i.e. oral feeding, tube feeding or parenteral feeding) plays a role in pressure ulcer prevention and treatment

This update of the original systematic review was required to summarize the best research available and to enable evidence‐based guidance on the role of nutritional interventions in the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect of enteral and parenteral nutritional interventions (e.g. supplementation) on the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of parallel or crossover design evaluating the effect of enteral and/or parenteral nutrition on the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers by measuring the incidence of new ulcers, ulcer healing rates or changes in pressure ulcer severity.

Types of participants

People of any age and sex with or without existing pressure ulcers, in any care setting, irrespective of primary diagnosis. For the purpose of this review a pressure ulcer is defined as an area of localised damage to the skin and underlying tissue caused by pressure, shear, friction or a combination of these.

Types of interventions

Clearly described nutritional supplementation (enteral or parenteral nutrition) or special diets. Comparisons between supplementary nutrition plus standard diet versus standard diet alone and between different types of supplementary nutrition (e.g. enteral versus parenteral) were eligible.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Proportion of participants developing new (incident) pressure ulcers (for prevention studies); and,

time to complete healing (for treatment studies).

Secondary outcomes

Acceptability of supplements;

side effects;

costs;

rate of complete healing;

rate in change of size of ulcer (absolute and relative);

health‐related quality of life.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The search methods section of the original published version of this review is shown in Appendix 1.

In March 2014, for this first update, we searched the following electronic databases to find reports of relevant RCTs:

The Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register (searched 25 March 2014);

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2014, Issue 1);

The Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (The Cochrane Library 2014, Issue 1);

The Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA) (The Cochrane Library 2014, Issue 1);

The Cochrane Methodology Register (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 3);

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (The Cochrane Library 2014, Issue 1);

Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to March Week 2 2014);

Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, March 24, 2014);

Ovid EMBASE (1974 to 2014 March 24);

EBSCO CINAHL (1982 to 20 March 2014

The following strategy was used to search CENTRAL:

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Pressure Ulcer] explode all trees510 #2 pressure next (ulcer* or sore*) 1071 #3 decubitus next (ulcer* or sore*) 110 #4 (bed next sore*) or bedsore* 68 #5 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 1150 #6 MeSH descriptor: [Nutritional Physiological Phenomena] explode all trees18062 #7 MeSH descriptor: [Nutrition Therapy] explode all trees6361 #8 MeSH descriptor: [Enteral Nutrition] explode all trees1407 #9 MeSH descriptor: [Parenteral Nutrition] explode all trees1466 #10 nutrition* 25947 #11 MeSH descriptor: [Diet] explode all trees10790 #12 diet* 35397 #13 tube next (fed or feed or feeding) 442 #14 #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 52460 #15 #5 and #14 155

The search strategies for Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE and EBSCO CINAHL can be found in Appendix 2, Appendix 3 and Appendix 4 respectively. The Ovid MEDLINE search was combined with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximizing version (2008 revision); Ovid format (Lefebvre 2011). The EMBASE and CINAHL searches were combined with the trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (SIGN 2009). No date or language restrictions were applied. As the search strategy had been redesigned we screened all records regardless of publication year.

By updating the review we additionally searched several trial registers and searched in the first quarter of 2011:

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry;

CenterWatch Clinical Trials Listing Service;

Chinese Clinical Trial Register; ClinicalTrials.gov register;

Community Research & Development Information Service (of the European Union);

Current Controlled Trials metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) – active & archived registers;

German Trials Register;

Hong Kong Clinical Trials Register;

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal;

International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register;

Netherlands Trial Register;

South African National Clinical Trial Register;

UK Clinical Trials Gateway;

UK National Research Register (NRR);

University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN);

Clinical Trials Registry (for Japan) – UMIN CTR.

Searching other resources

For the original review handsearching of conference proceedings and journals was performed, bibliographies of relevant articles were examined and experts in the field were contacted in order to find additional literature that might be relevant, however no further handsearching was undertaken for this update. The reference lists of all identified eligible studies and other published systematic reviews were searched in order to identify further eligible studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Results from the search were assessed for potential eligibility by two review authors independently, and disagreement was resolved by discussion with a third review author. Potentially relevant studies were retrieved in full and two review authors decided, independently, whether these studies met the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

References identified from searches were entered into a bibliographic software package. Details of eligible studies were extracted and summarised using a data extraction sheet. Studies that had been published in duplicate were included only once except where multiple publications provided additional data. Data extraction was undertaken by two review authors simultaneously and independently. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias for each included study using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011). Five domains of risk of bias were assessed according to the The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), namely: generation of randomisation sequence, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting )(see Appendix 5 for details of criteria on which the judgement will be based). We presented the assessment of risk of bias using a 'risk of bias summary figure', which shows all of the judgements in a cross‐tabulation of study by entry. This display of internal validity indicates the weight the reader may give the results of each study.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Where there was the potential to pool data from separate studies, we assessed between study heterogeneity with both the chi‐squared test and the I2. We regarded I2 greater than 60% as indicative of serious heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). Clinical heterogeneity was also considered.

Data synthesis

The method of synthesising the studies (i.e. random‐effects or fixed‐effect model) depended upon the heterogeneity of studies identified. In case of serious heterogeneity (i.e. where I2 > 60%) a random‐effects model was to be routinely applied when pooling was considered appropriate.

The following comparisons were planned:

Enteral compared with parenteral nutrition;

supplement/diet in addition to regular diet compared with regular diet alone;

comparisons between different types of supplement/diets.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

The following subgroup analyses were considered:

Characteristics of the setting (e.g. hospital in‐patients versus out‐patients);

method of feeding (e.g. enteral versus parenteral feeding);

characteristics of patients (e.g. people with pre‐existing malnutrition versus people without malnutrition).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Our search strategy in 2003 identified 942 articles from online databases (MEDLINE (PubMed), CINAHL, and CENTRAL). A further 13 articles were retrieved by handsearching; 17 were referred to us by experts and manufacturers, and a further 23 were found by scanning bibliographies of relevant papers. In addition the Cochrane Wounds Group identified a further nine articles. After merging the results and removing duplicates, 912 citations were left and were reviewed independently. Two of the review authors had an initial overall agreement of 99% (904/912), and identified 16 studies related to potentially relevant trials, the text of which were retrieved in full. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and the rating of the third author. Eight trials met the inclusion criteria for the original version of this review.

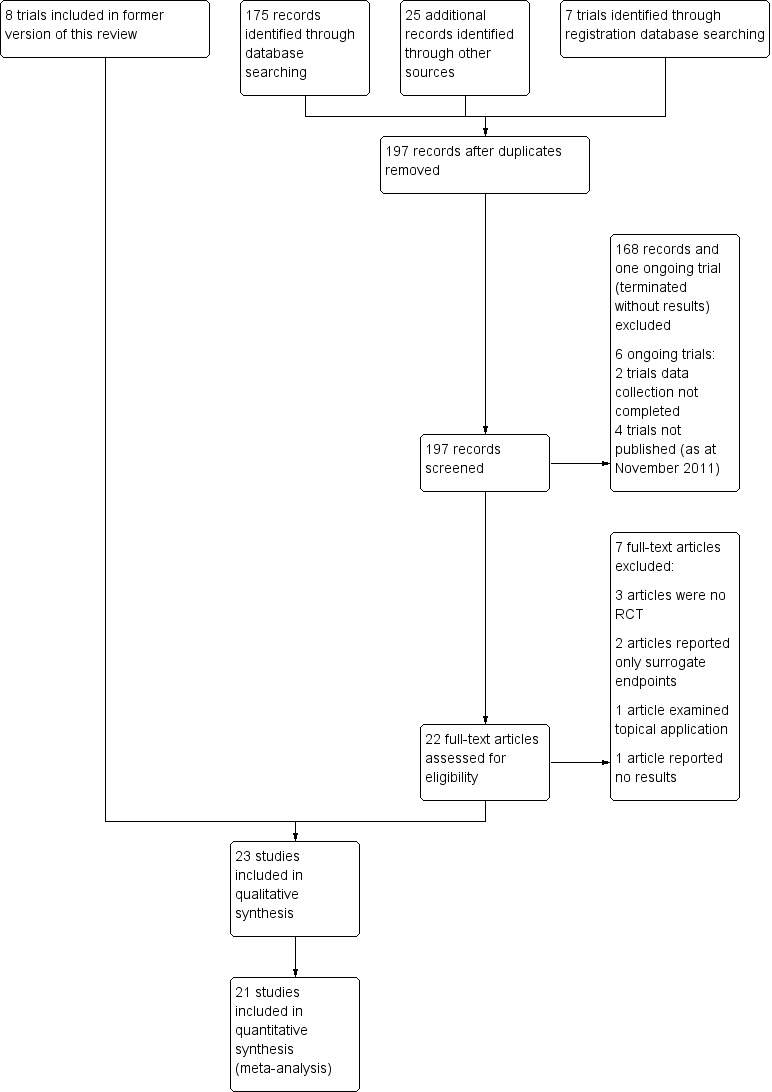

Our search strategy in 2011 identified 175 articles from online databases (MEDLINE (PubMed), EMBASE, CINAHL, and CENTRAL), 19 by scanning bibliographies of relevant papers and seven by searching registration databases. In addition, the Cochrane Wounds Group identified a further six articles. After merging the results and removing duplicates, 197 citations were left and were reviewed independently. The two authors had an initial overall agreement of 98% (192/197), and identified 22 studies related to potentially relevant trials, full text copies of which were retrieved in full (see Figure 1). Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Fifteen trials met the inclusion criteria bringing the total number of included studies to 23 (27 citations).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Twenty three RCTs are now included in the review (see Characteristics of included studies table); comprising 8 RCTs from the previous version of the review and 15 newly included RCTs.

Design

All included studies were RCTs. Six studies were multi‐centre trials (Bourdel‐M 2000; Dennis 2005; Meaume 2009; Ohura 2011; ter Riet 1995; van Anholt 2010).

Setting

Fifteen of the 23 trials were carried out in hospitals (Arias 2008; Benati 2001; Bourdel‐M 2000; Brewer 1967; Dennis 2005; Derossi 2009; Desneves 2005; Hartgrink 1998; Houwing 2003; Meaume 2009; Norris 1971; Ohura 2011; Olofsson 2007; Taylor 1974; Theilla 2007), and three in long‐term care facilities (Cereda 2009; Craig 1998; Lee 2006). One study was conducted in the long‐term care unit of a university hospital (Ek 1991). Two multi‐centre trials covered a range of settings, with long‐term care units and hospital wards (ter Riet 1995; van Anholt 2010). The Delmi 1990 trial was carried out in a orthopaedic ward, but some of the participants were transferred to a rehabilitation hospital. Chernoff 1990 did not mention the setting. Most studies were conducted in Europe (Benati 2001; Bourdel‐M 2000; Cereda 2009; Delmi 1990; Derossi 2009; Ek 1991; Hartgrink 1998; Houwing 2003; Olofsson 2007; Taylor 1974; ter Riet 1995), or the USA (Brewer 1967; Chernoff 1990; Craig 1998; Lee 2006; Norris 1971) with one each from Australia (Desneves 2005), Israel (Theilla 2007), Japan (Ohura 2011) and Urugay (Arias 2008). Three studies were international trials (Dennis 2005; Meaume 2009; van Anholt 2010).

Participants

Most of the studies included in the review were small. The median sample size was 88 participants, with a range from 12 (Chernoff 1990) to 4023 patients (Dennis 2005). Fourteen were conducted as treatment studies because the included participants already had pressure ulcers (Benati 2001; Brewer 1967; Cereda 2009; Chernoff 1990; Desneves 2005; Ek 1991; Lee 2006; Meaume 2009; Norris 1971; Ohura 2011; Taylor 1974; ter Riet 1995; Theilla 2007; van Anholt 2010). Five trials specifically recruited people with hip fractures (Delmi 1990; Derossi 2009; Hartgrink 1998; Houwing 2003; Olofsson 2007). Other patient populations, each with one trial, included stroke patients (Dennis 2005), and people with spinal cord injury (Brewer 1967). In several studies the mean age of the participants was over 80 years (Bourdel‐M 2000; Cereda 2009; Craig 1998; Delmi 1990; Hartgrink 1998; Houwing 2003; Meaume 2009; Olofsson 2007). The mean ages in the trials of Arias 2008 and Theilla 2007 were considerably lower at 60.2 years and 61.1 years respectively. Not all studies reported the mean age of the participants.

Interventions

The interventions in the included trials can be summarized as special nutrient supplementation or mixed nutritional supplements. Eleven studies considered mixed nutritional supplements as an intervention to prevent pressure ulcers (Arias 2008; Bourdel‐M 2000; Craig 1998; Delmi 1990; Dennis 2005; Derossi 2009; Ek 1991; Hartgrink 1998; Houwing 2003; Olofsson 2007; Theilla 2007). Mixed nutritional supplements included energy enriched supplements of protein alone and mixed supplements of protein, vitamins, carbohydrate, and lipids etc. All studies compared the nutritional intervention with a standard intervention, for example standard hospital diet, or standard hospital diet plus placebo.

Seven treatment studies considered special nutrients compared with placebo: two investigated the influence of ascorbic acid (Taylor 1974; ter Riet 1995); two the impact of zinc sulphate (Brewer 1967; Norris 1971); and three the impact of protein (Chernoff 1990; Lee 2006; Meaume 2009). Six studies considered mixed nutritional supplements as an intervention to treat pressure ulcers (Benati 2001; Cereda 2009; Desneves 2005; Ek 1991; Ohura 2011; van Anholt 2010). Ohura 2011 investigated the influence of increased energy in comparison with a standard amount of energy. The other studies compared the nutritional intervention with a standard intervention, for example standard hospital diet or standard hospital diet plus placebo.

Two studies considered the influence of mixed nutritional supplements on pressure ulcer healing as well as on the prevention of pressure ulcers (Ek 1991; Theilla 2007). In three studies the enteral nutrition or supplement was administered by nasogastric tube (Craig 1998; Hartgrink 1998; Ohura 2011).

Outcomes

Prevention

Five studies reported pressure ulcer incidence (Bourdel‐M 2000; Ek 1991; Hartgrink 1998; Houwing 2003; Theilla 2007). In six studies pressure ulcer incidence was considered as an in‐hospital complication (Arias 2008; Craig 1998; Delmi 1990; Dennis 2005; Derossi 2009; Olofsson 2007).

Treatment

The outcomes were heterogeneous. Two different validated scores were reported, namely the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH, National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel; Thomas 1997; Günes 2009) and the Pressure Sore Status Tool (PSST; Bates‐Jensen 1992; Benati 2001). Five trials reported pressure ulcer healing with validated scores: four with PUSH (Cereda 2009; Desneves 2005; Lee 2006; van Anholt 2010), and one with PSST (Benati 2001). Other studies considered pressure ulcer size, pressure ulcer surface, or pressure ulcer volume (Cereda 2009; Chernoff 1990; Meaume 2009; Taylor 1974; ter Riet 1995). Five studies reported the number of people healed (Brewer 1967; Cereda 2009; Ohura 2011; Taylor 1974; ter Riet 1995), and one study noted adverse effects related to the supplements (Meaume 2009).

Excluded studies

See Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Fifteen studies were excluded from the review for the following reasons:six studies were not randomised (Barateau 1998; Bergstrom 1987; Bourdel‐M 1997; Breslow 1991; Langemo 2006; Neander 2004). Three trials used surrogate primary endpoints without specifically reporting pressure ulcers, or did not report any other outcomes predefined in this review (Eneroth 2006; Langkamp‐Henken 2000; Stotts 2009). One study used a topical application of vitamin A (Settel 1969). One study compared mixed nutritional supplements, but did not report any results (Schröder‐van den N 2004). One study appears to report on the same study and group of patients as the Ek 1991 trial, but does not report pressure ulcer outcomes (Larsson 1990). Breslow 1993 intended to conduct a RCT but switched to a CCT because groups were unbalanced and the trial had a high drop‐out rate; therefore the authors decided to exchange patients within the groups. One study (Myers 1990) did not explicitly describe the type of nutritional supplementation. Another trial we found in a registration database had been terminated without results because of a lack of patients (NCT00502372).

Ongoing studies

We identified six ongoing trials from different registration databases (NCT01107197; ACTRN12605000704695; NCT00228657; NCT01142570; ACTRN12610000526077; NCT01090076). In two trials the data collection was not complete (NCT01107197; NCT01142570), while another trial announced results for the third quarter of 2012 (ACTRN12605000704695). We contacted the principal investigators of the trials where all the data had been collected and asked for information about the outcomes in which we are interested (ACTRN12605000704695; NCT00228657; NCT01142570; ACTRN12610000526077; NCT01090076), but either they did not respond, or were not allowed to release any results prior to publication.

Risk of bias in included studies

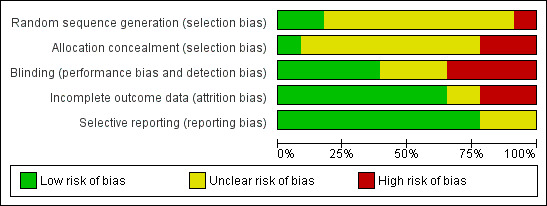

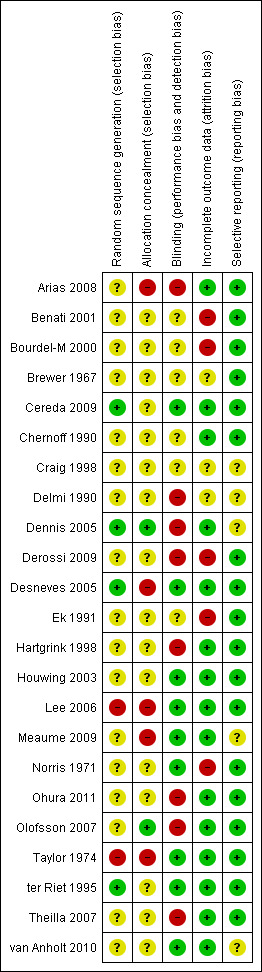

All included studies were prospective RCTs. In general, most of the studies included in the review were small and had either an unclear, or high risk, of bias. Figure 2 and Figure 3 show judgments about the risk of bias for all the included studies. The descriptions of the risk of bias for each item and for each included trial are described in the Characteristics of included studies table.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Randomisation sequence generation

Only four out of 23 trials clearly reported adequate generation of randomisation sequence (Cereda 2009; Dennis 2005; Desneves 2005; ter Riet 1995).

Allocation concealment

Only one out of 23 trials clearly reported adequate allocation concealment (Dennis 2005).

Blinding

Seven trials tried to minimise performance bias by blinding the medical staff and patients to treatment allocation (Houwing 2003; Lee 2006; Meaume 2009; Norris 1971; Taylor 1974; ter Riet 1995; van Anholt 2010). Two trials blinded only the outcome assessor (Cereda 2009; Desneves 2005). Two other studies were described as blinded, but the methods were not reported (Brewer 1967; Craig 1998). Three trials were assumed not to have performed any blinding because blinding of participants or medical staff was not described, and so these were rated as being of unclear risk of bias (Bourdel‐M 2000; Chernoff 1990; Ek 1991). In eight trials, the intervention was apparent to patients and medical staff, and therefore blinding was deemed not to be possible (Arias 2008; Delmi 1990; Dennis 2005; Derossi 2009; Hartgrink 1998; Ohura 2011; Olofsson 2007; Theilla 2007).

Incomplete outcome data

Many of the trials reported the reasons for withdrawals and drop‐outs very accurately. Three trials minimised attrition bias by analysing data with an intention‐to‐treat approach (Dennis 2005; ter Riet 1995; van Anholt 2010). Two trials specified that there were no drop‐outs or withdrawals (Chernoff 1990; Houwing 2003). Six trials were judged to have a high risk of bias either because the reasons for losses‐to‐follow‐up were unclear (Benati 2001; Delmi 1990; Derossi 2009), or the drop‐out rate was unacceptably high (Hartgrink 1998; Norris 1971), or there was an imbalance in numbers of drop‐outs from different study groups (Hartgrink 1998). In the trial of Ek 1991 the drop‐outs were not comprehensibly described with regard to the numbers of participants in the intervention group and the control group; furthermore the number of patients evaluated was not clearly described.

Selective reporting

Most of the trials reported the outcome data analogous to the measurements described in the methods section. An unclear risk of selective reporting had to be assumed for five trials. Two of them did not describe all clinical outcomes, so it was not clear whether they were assessed (Craig 1998; Delmi 1990). Two trials did not report at least one pre‐defined outcome measure which was specified at the beginning of their study, but this is less relevant with regard to this review because outcomes relevant for this review have been reported (Dennis 2005; van Anholt 2010). One study stated for a subgroup that, "there have been no significant differences", but did not provide the results (Meaume 2009).

Risk of bias summary

All included trials had a certain risk of bias, with one or more quality domains judged as either unclear or at high risk of bias. Figure 2 shows judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included trials. Interpretations and conclusion of the effects of the following interventions should be drawn against the background of these findings.

Effects of interventions

The included trials were heterogeneous with regard to patients (e.g. some surgical, some critically ill, some residents in nursing homes), and to nutritional interventions (e.g. type of nutritional intervention, form in which supplementation was applied, time of application, and dose and duration of nutritional supplementation).

PREVENTION STUDIES

The primary outcome in prevention studies was the proportion of participants who developed new pressure ulcers. The results are presented here as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The risk ratio is the proportion of people developing a new pressure ulcer in the intervention group divided by the proportion in the control group.

Mixed nutritional supplements compared with standard hospital diet (nine trials)

Delmi 1990: included 59 people recovering from hip fractures and presented data on the prevalence of pressure ulcers at three time points. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups at the final follow‐up (six months).No pressure ulcers were present in the treatment group though there were two in the control group (RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.01 to 4.28). Ek 1991: included 501 patients who were expected to remain in hospital for more than three weeks, with follow‐up for up to 26 weeks. There was no statistically significant difference in pressure ulcer development between the two groups (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.42; P value = 0.49). Hartgrink 1998: included 140 people recovering from hip fractures who were followed‐up for two weeks. After two weeks 25/48 (52%) of the patients remaining in the intervention group and 30/53 (56% )in the control group had pressure ulcers of Grade 2 or more (where Grade 2 was damage to at least the extent of blister formation).An intention‐to‐treat analysis indicated no difference in the incidence of sores of Grade 2 or above. Bourdel‐M 2000: included 672 people over 65 years of age who were in the acute phase of a critical illness; participants were followed‐up for 15 days or until discharged. At 15 days, the cumulative incidence of pressure ulcers (all grades) was 40% (118/295, calculated from relative numbers as absolute numbers have not been provided) in the nutritional intervention group compared with 48% (181/377, calculated from relative numbers as absolute numbers have not been provided) in the control group. There was a reduction in pressure ulcer development with supplementation (RR 0.83 (95% CI 0.70 to 0.99; P value = 0.04). The incidence of pressure ulcers was derived from the raw data and was not directly reported by the authors.The proportion of erythema was 90% for both groups and no significant differences in the development of erythema were detected between the two groups. Multivariate analysis, taking into account all diagnoses, potential risk factors and the intra‐ward correlation, indicated that the independent risk factors of developing a pressure ulcer were: serum albumin level at baseline, Kuntzman score at baseline, lower limb fracture, Norton score < 10, and belonging to the control group. Houwing 2003: included 103 hip fracture patients who were followed‐up for 28 days. There was no significant difference between the two groups; the incidence of pressure ulcers (grades I to 2) in the nutritional intervention group was 27/51 (55%) compared with 30/52 (59%) in the placebo group (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.30; P value = 0.63). None of the participants developed a pressure ulcer of a grade higher than 2 but the incidence of pressure ulcers at Grade 2 was 18% in the nutritional intervention group versus 28% in the placebo group, which was not statistically significant (RR 0.66; 95% CI 0.31 to 1.38; P value = 0.27). Dennis 2005: included 4023 stroke patients who were able to swallow. There was no significant difference in pressure ulcer incidence between the two groups (15/2014 (0.75%) in the supplemented group compared with 26/2001 (1.30%) in the control group: RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.08; P value = 0.08). This trial only reported additional outcomes defined as secondary outcomes for this review. Quality‐of‐life (EUROQoL) information was available from 3086 (99%) patients, with no major differences between groups. Median utility (ranging from 0, i.e. death, to 1, i.e. perfect health) for all patients, including those who died, was 0.52 (interquartile range 0.03 to 0.74, P value = 0.96 for difference between groups) in both groups (difference between means = 0·001 (95%CI –0·023 to 0·025)). Olofsson 2007: included 199 patients with femoral neck fracture aged 70 years or older. There was no significant difference between the two groups (treatment group 7/83 (8.43%) and control group 14/74 (18.92%); RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.19 to 1.04; P value = 0.12). Arias 2008: randomised 667 patients with mild or serious malnutrition (Subjective Global Assessment B or C). There was no significant difference between the two groups (nutritional intervention group 33/264 (12.50%) compared with the control group 26/273 (9.52%); RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.81 to 2.13; P value = 0.27). Derossi 2009: included 107 hip‐fracture patients aged 65 and older, scheduled to undergo surgical treatment. Pressure ulcers were considered to be a complication. The authors noted that there were no differences between the intervention and control groups, but did not present any data, and did not respond to our request for clarification. This trial was therefore not included in the pooled analysis.

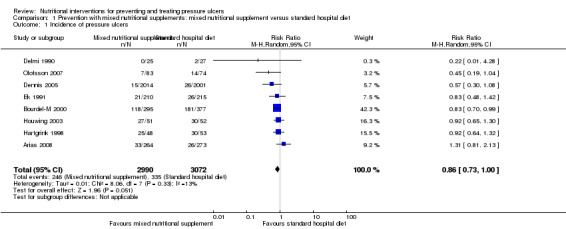

When the eight trials with available data were pooled using a fixed effect model there was a reduction in pressure ulcer incidence with supplementation (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.96; I2 =13%). This difference was less clear when a random effects model was applied (RR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.00)(Analysis 1.1; Figure 4). Given the methodological differences between these studies (differences in interventions and duration of follow up), the random effects model is probably more appropriate, although some may argue that pooling at all is inappropriate.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Prevention with mixed nutritional supplements: mixed nutritional supplement versus standard hospital diet, Outcome 1 Incidence of pressure ulcers.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Prevention with mixed nutritional supplements: mixed nutritional supplement versus standard hospital diet, outcome: 1.1 Incidence of pressure ulcers.

Mixed nutritional supplements compared with other nutritional interventions (two trials).

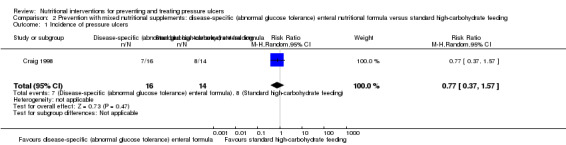

Craig 1998 included 34 people with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus or documented hyperglycaemia and requiring total enteral nutrition support by nasogastric tube. Disease‐specific enteral nutritional formula was compared with standard high‐carbohydrate feeding. There was no difference in pressure ulcer development between the two groups (7/16 (43.75%) developed a pressure ulcer in the treatment group compared with 8/14 (57.14%) in the control group); RR 0.77 (95% CI 0.37 to 1.57; P value = 0.47; Analysis 2.1 ).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Prevention with mixed nutritional supplements: disease‐specific (abnormal glucose tolerance) enteral nutritional formula versus standard high‐carbohydrate feeding, Outcome 1 Incidence of pressure ulcers.

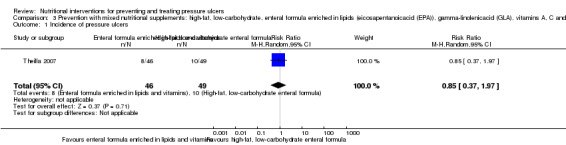

Theilla 2007 included 100 intensive care patients suffering from acute lung injury and compared a high fat and low carbohydrate enteral formula which was enriched in lipids vitamins A, C, and E with a high‐fat and low‐carbohydrate enteral formula. There was no difference between the two groups in pressure ulcer development; there were eight new pressure ulcers in the supplemented group compared with 10 in the control group (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.97; P value = 0.71; Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Prevention with mixed nutritional supplements: high‐fat, low‐carbohydrate, enteral formula enriched in lipids (eicosapentanoicacid (EPA)), gamma‐linolenicacid (GLA), vitamins A, C and E versus high‐fat, low‐carbohydrate, enteral formula, Outcome 1 Incidence of pressure ulcers.

Summary of the effects of nutritional supplements on pressure ulcer development

Eleven studies investigated the effect of mixed nutritional supplements on pressure ulcer incidence (Arias 2008; Bourdel‐M 2000; Craig 1998; Delmi 1990; Dennis 2005; Derossi 2009; Ek 1991; Hartgrink 1998; Houwing 2003; Olofsson 2007; Theilla 2007). Overall the incidence of pressure ulcers was lower in the intervention group in all trials except for Arias 2008 however none of these differences was statistically significant with the exception of Bourdel‐M 2000. It was possible to pool eight of these trials in a meta‐analysis (Delmi 1990; Dennis 2005; Ek 1991; Arias 2008; Hartgrink 1998; Houwing 2003; Olofsson 2007). When a fixed effect model was applied, there was a reduction in the risk of pressure ulceration associated with nutritional supplementation (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.96; P value = 0.01; I2 = 13%). This difference was not robust to analysis using a random effects model (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.00; P value = 0.05) Analysis 1.1; Figure 4). There is clearly considerable uncertainty as to whether nutritional supplementation reduces pressure ulceration and heterogeneity in the studies that have explored this.

There was no evidence of a difference in pressure ulcer development when alternative nutritional supplements were compared with each other but there have only been two small trials.

Overall, these studies were at high or unclear risk of bias. Generally, studies were not at risk of selective reporting, but we were uncertain about the risk of bias in other key domains, for example, generation of allocation sequence and concealment of allocation. Blinding of participants, clinical staff and outcome assessors did not seem to have been performed adequately overall, with nearly all studies (with the exception of Houwing 2003) at high or unclear risk of performance bias.

TREATMENT STUDIES

Mixed nutritional supplements compared with other nutritional interventions (seven trials)

Seven studies investigated the effect of mixed nutritional supplements on the healing of existing pressure ulcers (Benati 2001; Cereda 2009; Ek 1991; Desneves 2005; Ohura 2011; Theilla 2007; van Anholt 2010).

Arginine‐enriched mixed nutritional supplement compared to standard hospital diet (four trials)

Four trials investigated the effect of an arginine‐enriched mixed nutritional supplement on pressure ulcers.

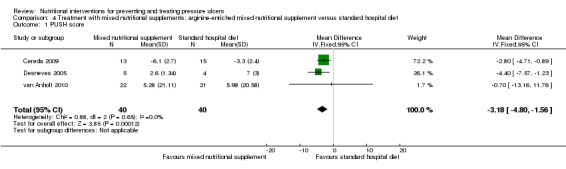

Rate of ulcer healing

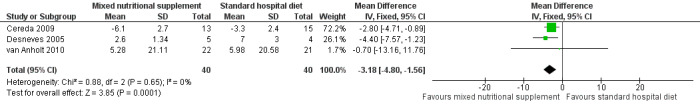

Benati 2001 undertook a preliminary investigation but presented the results in graphical form only with no numerical data. The patients who received supplementation had a better pressure ulcer healing score (PSST). Three studies used the PUSH score as an outcome. Desneves 2005 compared the effect of two different kinds of supplement, i.e. an arginine, zinc, and vitamin C‐enriched supplement or a high‐protein, high‐energy supplement to standard hospital diet. The difference in mean PUSH scores was ‐4.40 (95% CI ‐7.57 to ‐1.23) in favour of the arginine, zinc and vitamin C‐enriched supplement. van Anholt 2010 found no difference when comparing a special supplement in non‐malnourished patients with placebo (difference in PUSH scores ‐0.70; 95% CI ‐13.16 to 11.76;); this paper includes a Repeated Measures Mixed Model. In the trial of Cereda 2009 the difference in the change in PUSH scores indicated better healing in the supplemented group (MD = ‐2.80; 95% CI ‐4.71 to ‐0.89; P value = 0.01). When these three studies were combined there was greater improvement in PUSH scores in people who received the arginine‐enriched supplement compared with those on the standard hospital diet (Mean Difference ‐3.18; 95% CI ‐4.80 to ‐1.56; P value = 0.0001; I2 = 0%) (Analysis 4.1; Figure 5). The validity of this result is undermined by the quality of reporting of the primary studies; this precluded our ability to accurately judge risk of bias.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Treatment with mixed nutritional supplements: arginine‐enriched mixed nutritional supplement versus standard hospital diet, Outcome 1 PUSH score.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 Treatment with mixed nutritional supplements: arginine‐enriched mixed nutritional supplement versus standard hospital diet, outcome: 4.1 PUSH score.

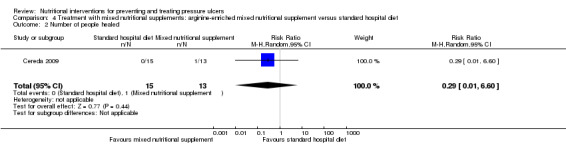

Number of people healed

Cereda 2009 reported a complete healing of pressure ulcers in 1/13 patients in the nutritional intervention group versus 0/15 patients in the standard hospital diet group; clearly with only one healing event there is insufficient statistical power to detect a difference as statistically significant in this comparison (RR 0.29; 95% CI 0.01 to 6.60; P value = 0.44; Analysis 4.2).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Treatment with mixed nutritional supplements: arginine‐enriched mixed nutritional supplement versus standard hospital diet, Outcome 2 Number of people healed.

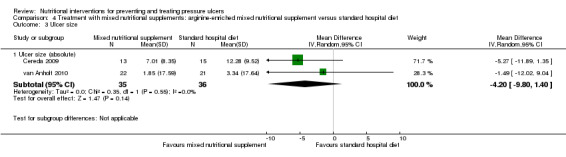

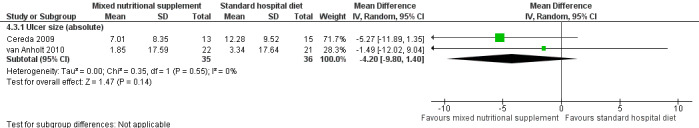

Ulcer size

The trials of Cereda 2009 and van Anholt 2010 both assessed difference in mean pressure ulcer size and were pooled (I2 = 0%); overall there was no clear evidence of a treatment effect of the arginine enriched supplement (compared with the standard hospital diet) though there is a lack of statistical power and a difference cannot be ruled out (MD ‐4.20 cm2 95% CI ‐ 9.80 to 1.40; P value = 0.14) (Analysis 4.3; Figure 6).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Treatment with mixed nutritional supplements: arginine‐enriched mixed nutritional supplement versus standard hospital diet, Outcome 3 Ulcer size.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 Treatment with mixed nutritional supplements: arginine‐enriched mixed nutritional supplement versus standard hospital diet, outcome: 4.3 Ulcer size.

Mixed nutritional supplements compared with standard hospital diet (one trial and the third group of another trial)

Ulcer healing

Ek 1991: included 501 patients who were expected to remain in hospital for more than three weeks and were followed‐up for up to 26 weeks. The patients in the supplemented group had 67 pressure ulcers, those in the standard hospital diet group had 83 pressure ulcers. In the supplemented group 41.8% of the pressure ulcers healed and 51.3% improved. In the standard hospital diet group 30.3% of the pressure ulcers healed and 43.9% improved.No further analyses were undertaken as the number of patients evaluated in the groups was not clear from the trial report and there appears to have been inclusion of multiple pressure ulcers in individual patients.

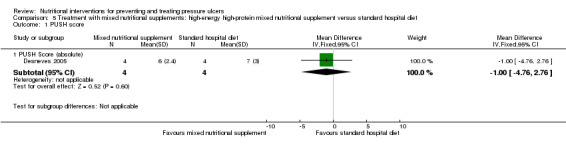

Desneves 2005: compared the effect of a high‐energy, high‐protein supplement with a standard hospital diet in a study with 8 patients. The difference between mean PUSH scores was ‐1.00 (95% CI ‐4.76 to 2.76; P value = 0.60 Analysis 5.1) showing no difference between the groups however this comparison is grossly underpowered.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Treatment with mixed nutritional supplements: high‐energy high‐protein mixed nutritional supplement versus standard hospital diet, Outcome 1 PUSH score.

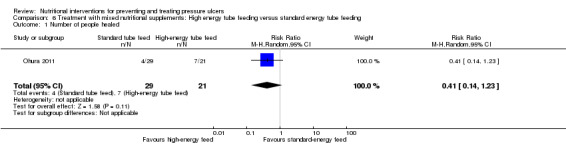

High‐energy tube feeding versus standard‐energy tube feeding (one trial)

Ohura 2011: recruited 60 tube‐fed patients with pressure ulcers of NPUAP Grades 3 to 4 and compared high‐energy tube feeding with standard‐energy tube feeding. The number of people whose ulcers healed was 7/21 in the treatment group and 4/29 in the control group. There was therefore no clear evidence of a benefit of high energy tube feeding however this comparison is very underpowered (RR 0.41; 95 % CI 0.14 to 1.23; P value = 0.11, Analysis 6.1).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Treatment with mixed nutritional supplements: High energy tube feeding versus standard energy tube feeding, Outcome 1 Number of people healed.

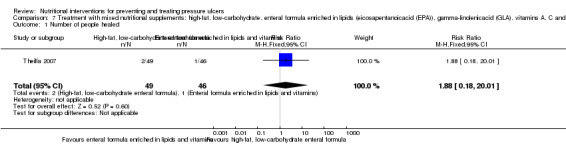

High‐fat, low‐carbohydrate, enteral formula enriched in lipids (eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), gamma‐linolenic acid (GLA)), plus vitamins A, C and E versus high‐fat, low‐carbohydrate, enteral formula (one trial).

Theilla 2007 recruited 100 people in intensive‐care and suffering from acute lung injury. The study compared a high‐fat and low‐carbohydrate enteral formula enriched in lipids with vitamins A, C, and E with a high‐fat and low carbohydrate enteral formula and there was no clear evidence of a benefit with the enriched formula. In the group receiving the enriched high fat/low carbohydrate enteral formula only one participant out of 46 healed compared with 2/49 in the control group (RR 1.88 (95% CI 0.18 to 20.01) (Analysis 7.1) Again this is a grossly underpowered comparison.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Treatment with mixed nutritional supplements: high‐fat, low‐carbohydrate, enteral formula enriched in lipids (eicosapentanoicacid (EPA)), gamma‐linolenicacid (GLA), vitamins A, C and E versus high‐fat, low‐carbohydrate, enteral formula, Outcome 1 Number of people healed.

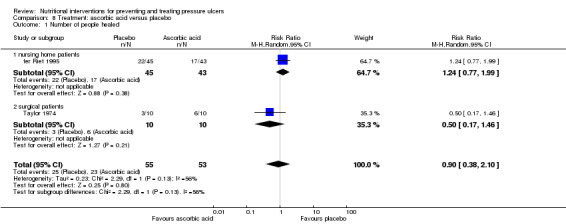

Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) compared with placebo (two trials)

Two trials investigated the effect of ascorbic acid on pressure ulcer healing. In the trial of Taylor 1974, 20 people in surgical wards were followed‐up and data reported at one month. The study of ter Riet 1995 was intended to replicate the trial of Taylor with more participants (n = 88).

Ulcer healing

Healing rate

The mean healing rate in the trial of Taylor 1974 was 2.47 cm2/week in the intervention group compared with 1.45 cm2/week in the control group. The mean healing rate in the trial of ter Riet 1995 was 0.21 cm2/week in the intervention group (n = 43) and 0.27 cm2/week in the control group (n = 45) (difference ‐0.06 cm2/week); no standard deviations were reported and therefore pooling was not possible.

Number of ulcers healed

Taylor 1974 reported that 6/10 participants in the ascorbic acid group completely healed compared with 3/10 participants in the placebo group. This comparison is underpowered with only 9 events and therefore there is no clear evidence of a benefit associated with ascorbic acid supplementation on complete healing (RR 0.5 95% CI 0.17 to 1.46; P value = 0.21)(Analysis 8.1). ter Riet 1995 conducted an appropriate survival analysis to compare the overall risk of healing on ascorbic acid and placebo and found no difference (HR 0.78, 90%CI 0.44 to ‐1.39).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Treatment: ascorbic acid versus placebo, Outcome 1 Number of people healed.

In order to allow comparison and meta‐analysis with the Taylor 1974 study, we extracted numbers healed from the survival curves of the ter Riet 1995 trial report. From the graphs, it appears that 17/43 in the ascorbic acid group were healed at 84 days compared with 22/45 in the placebo group (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.99; P value = 0.38; calculated by review authors Analysis 8.1). The two trials were pooled using a random effects model (I2=56%) and overall there was no evidence of a benefit on pressure ulcer healing of ascorbic acid supplementation (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.38 to 2.10; P value = 0.80; Analysis 8.1).

Ulcer size

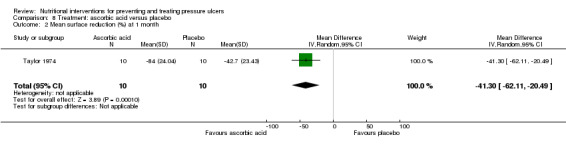

Taylor 1974 reported a greater mean reduction in pressure ulcer area in the group treated with ascorbic acid (84% reduction (SD 24.04) after one month compared with a 42.7% in the placebo group (SD 23.43) . The overall difference in means was 41.30% in favour of the ascorbic acid (95% CI ‐62.11 to ‐20.49; P value=0.0001 Analysis 8.2).

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Treatment: ascorbic acid versus placebo, Outcome 2 Mean surface reduction (%) at 1 month.

ter Riet 1995: the mean volume reduction was 0 ml/week in the intervention group and 0.20 ml/week in the control group (difference ‐0.20 ml/week). The mean "clinical change", where improvements (i.e. surface reduction, healing velocity, volume reduction) were scored on a scale from ‐100 to +100% was 17.89% per week in the intervention group and 26.08% per week in the control group (difference ‐8.19% per week).

In summary: the two studies that investigated the effect of ascorbic acid supplementation (compared with placebo) on existing pressure ulcers found no overall evidence of benefit.

Proteins or amino acids compared with other nutritional interventions (three trials)

Three trials investigated the effect of different proteins or amino acid products on pressure ulcer healing.

Very high protein (25% of calories) compared with high protein (16% of calories) (one trial)

At the start of the Chernoff 1990 study, pressure ulcers ranged in size from 1.0 cm2 to 46.4 cm2 in the very high protein (intervention) group and from 1.6 cm2 to 63.8 cm2 in the high protein (control) group. There was no difference in complete healing between treatment groups (RR 9.00 with 95% CI 0.59 to 137.65; P value = 0.11).

Concentrated, fortified, collagen protein hydrolysate supplement compared with placebo (one trial)

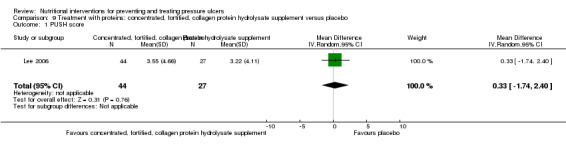

Lee 2006 examined the effect of a supplement of a concentrated, fortified, collagen protein hydrolysate supplement three times daily in 89 residents of long‐term care facilities with pressure ulcers of NPUAP grades 2, 3 and 4. There was a greater reduction in the difference in change in PUSH score in the supplemented group (decrease: ‐5.56 in the intervention group, ‐2.85 in the placebo group), however it should be noted that the PUSH Score was much higher in the intervention group at start of the trial. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in the study primary outcome of PUSH score at 8 weeks (MD = 0.33; 95% CI ‐1.74 to 2.40; P value = 0.76) (Analysis 9.1).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Treatment with proteins: concentrated, fortified, collagen protein hydrolysate supplement versus placebo, Outcome 1 PUSH score.

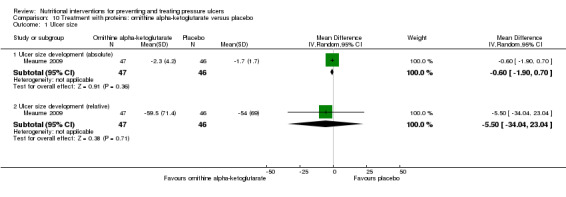

Ornithine alpha‐ketoglutarate compared with placebo (one trial)

Meaume 2009 analysed the effect of 10 g ornithine alpha‐ketoglutarate daily on the healing of heel pressure ulcers NPUAP Grade 2 or 3 after accidental immobilization. Because of baseline imbalances in ulcer area in the two groups, the analysis was stratified by ulcer area. There was no evidence of a benefit of the ornithine supplement in people with baseline PU area ≤ 8cm2 (difference in mean change in area ‐0.6 cm2 (95% CI ‐1.90 to 0.70; P value = 0.36).

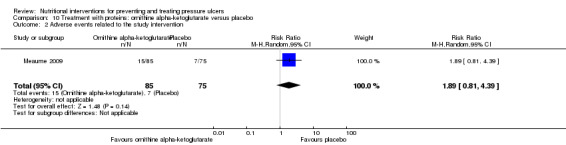

In the group with baseline PU area < 8 cm2 there was also no evidence of an effect of the ornithine supplement (difference in the mean change in PU area ‐5.50; 95% CI ‐34.04 to 23.04; P value = 0.71; Analysis 10.1). There were more adverse effects in the ornithine group (15/85 vs. 7/75) however this may have been a chance difference (RR 1.89, 95% CI 0.81 to 4.33; P value = 0.14; Analysis 10.2).

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Treatment with proteins: ornithine alpha‐ketoglutarate versus placebo, Outcome 1 Ulcer size.

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Treatment with proteins: ornithine alpha‐ketoglutarate versus placebo, Outcome 2 Adverse events related to the study intervention.

There were no differences in wound area changes in the group with baseline PU area > 8 cm2

Zinc sulphate compared with placebo (two trials)

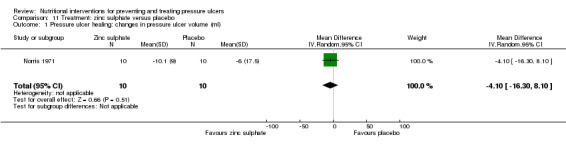

Two trials investigated the effect of zinc sulphate on the healing of pressure ulcers. In the Norris 1971 study, 20 people with pressure ulcers were treated with either zinc sulphate supplements or placebo. The zinc sulphate group showed a mean reduction in pressure ulcer volume of 10.1 ml (SD 9 ml) whilst those in the placebo group showed a mean reduction in pressure ulcer volume of 6.0 ml (SD 17.5 ml). There was no overall evidence of an effect of zinc sulphate on pressure ulcer volume (MD = ‐4.1 ml; 95% CI ‐16.30 to 8.10; P value = 0.51; Analysis 11.1).

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Treatment: zinc sulphate versus placebo, Outcome 1 Pressure ulcer healing: changes in pressure ulcer volume (ml).

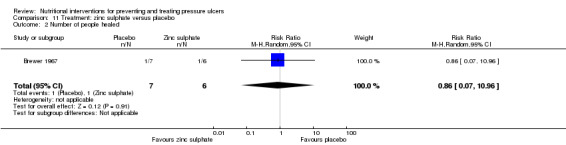

Brewer 1967 compared zinc sulphate with placebo in 14 patients with spinal cord injuries and poorly healing pressure ulcers. One person healed in the treatment group (n = 6) and one in the control group (n = 7) (RR 0.86;95% CI 0.07 to 10.96; P value = 0.91; Analysis 11.2).

11.2. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Treatment: zinc sulphate versus placebo, Outcome 2 Number of people healed.

Discussion

The studies of nutritional supplementation vary in terms of interventions, outcome measurements and follow‐up; interpretation of these findings should be made with caution.

Summary of main results

Eleven studies compared a combination of nutritional supplements, consisting of a minimum of energy and protein in different dosages, for the prevention of pressure ulcers. A meta‐analysis was performed including eight trials comparing the effect of mixed nutritional supplements with standard hospital diet. The overall risk ratio (RR) was 0.86 (95% CI 0.73 to 1.00; P value = 0.05; see Analysis 1.1), Of the 6062 persons considered in this meta‐analysis 4015 were participants in the FOOD Trial (Dennis 2005). The other 2047 participants were allocated to seven trials which ranged in size from 52 to 672 participants. The trials examined clinically heterogenous interventions and were generally at high or unclear risk of bias. The clearest conclusion that can be drawn in the light of the volume and quality of this evidence is that it remains unclear whether nutritional supplementation reduces the risk of pressure ulcer development.

Fourteen studies evaluated the effects of nutritional supplements on the healing of existing pressure ulcers: seven trials examined mixed nutritional supplements, three the effect of protein supplements, two trials examined zinc, and two studies compared ascorbic acid with placebo. There is generally no clear evidence of improved pressure ulcer healing with nutritional supplements. There is some evidence of improved healing (as measured by a surrogate outcome measure, viz. PUSH scores) with an arginine enriched mixed nutritional supplement compared with standard hospital diet however there is no evidence of an effect on actual ulcer healing. Again most of the treatment studies were at unclear or high risk of bias.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Many studies included few patients and some had a considerable drop‐out rate. Furthermore, the follow‐up time was often very short, making it unlikely that true effects of interventions would be detected. Some trials reported that laboratory markers of malnutrition improved during treatment, but the clinical effects of protein, calories, vitamin or zinc supplementation on the incidence of new ulcers or healing of existing ulcers was unclear.The validity of the PUSH score as a surrogate measure of pressure ulcer healing is unclear.

Quality of the evidence

All included trials were at risk of bias with one or more quality domains judged as unclear or at high risk of bias. Interpretations and conclusion of the effects of the interventions should be drawn against the background of these findings.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Currently there is no clear evidence that nutritional interventions reduce the development of pressure ulcers or help them to heal. This conclusion should not be interpreted as nutritional interventions having no effect on pressure ulcers because the existing evidence base is of very low quality. People who are receiving health care and who are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition should receive expert nutritional assessment and intervention as per local practice.

Implications for research.

Further research with larger numbers of patients and sound methodology is required to procure evidence for the impact of nutrition on pressure ulcers. Consideration should be given to constituents of the supplement, and the method of application, as one study reported low tolerance of nasogastric tube feeding.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 25 March 2014 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | First update, new search, 15 additional trials included bringing the total to 23 trials. |

| 25 March 2014 | New search has been performed | Three review authors left the team and did not contribute to this update (G. Schloemer, O. Kuss, J. Behrens) |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2002 Review first published: Issue 4, 2003

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 21 August 2003 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment. |

Acknowledgements

The following people refereed the protocol and provided useful feedback: Mike Clark, Roberto Cassino, and Jane Kinniburgh. Special thanks go to Roberto Cassino, Mike Clark, Nicky Cullum, Andrew Jull, David Margolis, and Susan O'Meara for their helpful and constructive comments on this review. Special thanks go to Waltraud Mair for help with Spanish and Italian articles, Nadine Schumann for help with Italian articles, and Jens‐Olaf Hosenfeldt for help with Spanish articles. We are grateful for support and encouragement from Sally EM Bell‐Syer, E Andrea Nelson and Ruth Foxlee of the Cochrane Wounds Group. Thank you to Elizabeth Royle who copy edited the updated review. Special thanks go to Gabriele Schlömer and Johann Behrens for their contribution to the original version of the review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy for the original published version

The Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Trials Register was searched for reports of trials evaluating nutritional interventions in the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers in September 2002. The Trials Register has been developed and maintained by regular searches, using a maximally sensitive search strategy for retrieving randomised controlled trials, of 19 electronic databases, as well as handsearching of wound care journals and conference proceedings, and is regularly updated.

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) was also searched (Issue 3, 2002) using the following strategy: 1. (decubitus next ulcer*) 2. (bed and sore*) 3. (pressure and sore*) 4. (pressure and ulcer*) 5. DECUBITUS‐ULCER*:ME 6. ((((#1 or #2) or #3) or #4) or #5) 7. nutrition* 8. diet* 9. tube‐fe* 10. NUTRITION*:ME 11. DIET*:ME 12. DIET‐THERAPY*:ME 13. NUTRITIONAL‐SUPPORT*:ME 14. ENTERAL‐NUTRITION*:ME 15. PARENTERAL‐NUTRITION*:ME 16. ((((((((#7 or #8) or #9) or #10) or #11) or #12) or #13) or #14) or #15) 17. (#6 and #16)

MEDLINE was searched in June 2003 via PubMed using the following strategy: 1. (bed sore) OR bedsore OR (pressure sore) OR (decubitus ulcer) OR (pressure ulcer) OR (decubital ulcer) OR (ischaemic ulcer) 2. "Decubitus Ulcer"[MESH] 3. nutri* OR diet OR food 4. "nutrition"[MESH] OR "Diet"[MESH] OR "Food"[MESH] OR "Nutritional Support"[MESH] 5. enteral OR parenteral OR proteins OR vitamins OR minerals 6. "Amino Acids, Peptides, and Proteins"[MESH] OR "Dietary Supplements"[MESH] OR "Growth Substances, Pigments, and Vitamins"[MESH] OR "Enzymes, Coenzymes, and Enzyme Inhibitors"[MESH] OR "Lipids and Antilipaemic Agents"[MESH] OR "Minerals"[MESH] 7. therapy OR prophylaxis OR prevention 8. (randomized controlled trial[PTYP] OR drug therapy[SH] OR therapeutic use[SH:NOEXP] OR random*[WORD]) 9. systematic[sb] 10. (cohort studies[MESH] OR risk[MESH] OR (odds[WORD] AND ratio*[WORD]) OR (relative[WORD] AND risk[WORD]) OR (case control*[WORD] OR case‐control studies[MESH])) 11. (incidence[MESH] OR mortality[MESH] OR follow‐up studies[MESH] OR mortality[SH] OR prognos*[WORD] OR predict*[WORD] OR course[WORD]) 12. (#1 OR #2) AND (#3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6) AND (#7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11)

CINAHL was searched via Ovid in June 2003 with the following query: 1. exp Pressure ulcer/nu, dh, pc, et, rf, th, me [Nursing, Diet Therapy, Prevention and Control, Etiology, Risk Factors, Therapy, Metabolism] 2. PARENTERAL NUTRITION SOLUTIONS/ or ENTERAL NUTRITION/ or TOTAL PARENTERAL NUTRITION/ or PERIPHERAL PARENTERAL NUTRITION/ or PARENTERAL NUTRITION/ or NUTRITION/ 3. 1 and 2

The listed databases were searched by the authors for eligible studies for the earliest entrance date possible until the latest search date. For this review there were no restrictions on date of publication, language of publication, or publication status (published or unpublished work). Experts in the field, such as scientific societies for wound healing and treatment, for nutrition and for nutritional medicine, were contacted and asked whether they had been involved in any further studies or were aware of recent or ongoing studies on the effect of nutrition in the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers.

We handsearched the following conference proceedings to identify any research or relevant studies:

the Congress of the European Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ESPEN) 1996 ‐2002

the Meetings of the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) 1997 ‐ 2000

Some additional journals to those stated in the protocol were considered suitable for handsearching. The following journals were searched by hand from 1996 to 2002:

Advances in Wound Care,

Advances in Food and Nutrition Research,

Clinical Nutrition,

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition,

European Journal of Nutrition,

Wundforum,

Zeitschrift fuer Wundbehandlung,

Zeitschrift fuer Wundheilung,

Zeitschrift fuer Gerontologie und Geriatrie,

Aktuelle Ernaehrungsmedizin,

Deutsches Wundjournal

Studies and articles cited in articles identified have also been checked for eligibility.

We tried to identify unpublished studies by contacting manufacturers of nutritional supplements (Fresenius, NutriScience, Pfrimmer, Braun, Ratiopharm, Aventis and Novartis), but this yielded no further studies.

Appendix 2. Ovid MEDLINE search strategy

1 exp Pressure ulcer/ (5595) 2 (pressure adj (ulcer$ or sore$)).ti,ab. (4721) 3 (decubitus adj (ulcer$ or sore$)).ti,ab. (618) 4 (bedsore$ or (bed adj sore$)).ti,ab. (258) 5 or/1‐4 (7036) 6 exp Nutrition Therapy/ (38354) 7 nutrition$.ti,ab. (98588) 8 diet$.ti,ab. (209761) 9 (tube adj (fed or feed or feeding)).ti,ab. (1628) 10 or/6‐9 (293406) 11 5 and 10 (546) 12 randomized controlled trial.pt. (261976) 13 controlled clinical trial.pt. (41370) 14 randomi?ed.ab. (257887) 15 placebo.ab. (97860) 16 clinical trials as topic.sh. (83790) 17 randomly.ab. (147290) 18 trial.ti. (80869) 19 or/12‐18 (605281) 20 exp animals/ not humans.sh. (1722788) 21 19 not 20 (550693) 22 11 and 21 (64)

Appendix 3. Ovid EMBASE search strategy

1 exp Decubitus/ (9677) 2 (pressure adj (ulcer$ or sore$)).ti,ab. (5976) 3 (decubitus adj (ulcer$ or sore$)).ti,ab. (821) 4 (bedsore$ or (bed adj sore$)).ti,ab. (427) 5 or/1‐4 (10912) 6 exp Nutrition/ (943162) 7 nutrition$.ti,ab. (148040) 8 diet$.ti,ab. (292491) 9 (tube adj (fed or feed or feeding)).ti,ab. (2443) 10 or/6‐9 (1054866) 11 5 and 10 (1274) 12 exp Clinical trial/ (814722) 13 Randomized controlled trial/ (296848) 14 Randomization/ (52199) 15 Single blind procedure/ (16283) 16 Double blind procedure/ (88664) 17 Crossover procedure/ (33182) 18 Placebo/ (173876) 19 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. (85967) 20 RCT.tw. (11475) 21 Random allocation.tw. (961) 22 Randomly allocated.tw. (15027) 23 Allocated randomly.tw. (1254) 24 (allocated adj2 random).tw. (269) 25 Single blind$.tw. (10164) 26 Double blind$.tw. (94024) 27 ((treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. (253) 28 Placebo$.tw. (143416) 29 Prospective study/ (214584) 30 or/12‐29 (1132169) 31 Case study/ (17663) 32 Case report.tw. (175248) 33 Abstract report/ or letter/ (528846) 34 or/31‐33 (717245) 35 30 not 34 (1103264) 36 animal/ (752648) 37 human/ (9046339) 38 36 not 37 (504611) 39 35 not 38 (1079882) 40 11 and 39 (230)

Appendix 4. EBSCO CINAHL search strategy

S28 S15 and S27 S27 S16 or S17 or S18 or S19 or S20 or S21 or S22 or S23 or S24 or S25 or S26 S26 MH "Quantitative Studies" S25 TI placebo* or AB placebo* S24 MH "Placebos" S23 TI random* allocat* or AB random* allocat* S22 MH "Random Assignment" S21 TI randomi?ed control* trial* or AB randomi?ed control* trial* S20 AB ( singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl* ) and AB ( blind* or mask* ) S19 TI ( singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl* ) and TI ( blind* or mask* ) S18 TI clinic* N1 trial* or AB clinic* N1 trial* S17 PT Clinical trial S16 MH "Clinical Trials+" S15 S5 and S14 S14 S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 S13 TI ( tube fed or tube‐fed or tube feed* ) or AB ( tube fed or tube‐fed or tube feed* ) S12 TI diet* or AB diet* S11 (MH "Diet Therapy+") S10 (MH "Diet+") S9 TI nutrition* or AB nutrition* S8 (MH "Parenteral Nutrition+") S7 (MH "Enteral Nutrition") S6 (MH "Nutrition+") S5 S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 S4 TI ( bed sore* or bedsore* ) or AB ( bed sore* or bedsore* ) S3 TI decubitus or AB decubitus S2 TI ( pressure ulcer* or pressure sore* ) or AB ( pressure ulcer* or pressure sore* ) S1 (MH "Pressure Ulcer")

Appendix 5. Risk of bias criteria

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

low risk of bias. The investigators describe a random component in the sequence generation process such as: referring to a random number table; using a computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimization (minimization may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random.

unclear; risk of bias. The trial is described as randomised but the method of sequence generation was not specified.

high risk of bias, the sequence generation method is not, or may not be, random. Quasi‐randomised studies, those using dates, names, or admittance numbers in order to allocate patients are considered inadequate, and will be excluded for the assessment of benefits, but not for harms.

Was allocation adequately concealed?

low risk of bias. Allocation was controlled by a central and independent randomisation unit, opaque and sealed envelopes or similar, so that intervention allocations could not have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment.

unclear; risk of bias. The trial was described as randomised, but the method used to conceal the allocation was not described, so that intervention allocations may have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment.

high risk of bias. If the allocation sequence was known to the investigators who assigned participants, or if the study was quasi‐randomised.

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

low risk of bias. The trial was described as double blind and the method of blinding was described, so that knowledge of allocation was adequately prevented during the trial.

unclear; risk of bias. The trial was described as blinded, but the method of blinding was not described, so that knowledge of allocation was possible during the trial.

high risk of bias. The trial was not blinded, so that the allocation was known during the trial.

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?

low risk of bias. Incomplete outcome data adequately addressed if the numbers and reasons for dropouts and withdrawals in all study groups were described, or if it was specified that there were no dropouts or withdrawals.

unclear; risk of bias. The report gave the impression that there had been no dropouts or withdrawals, but this was not specifically stated.

high risk of bias. Incomplete outcome data inadequately addressed if the number or reasons for dropouts and withdrawals were not described.

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

low risk of bias. Pre‐defined, or clinically relevant and reasonably expected outcomes are stated in the method section and are reported in the results section.

unclear; risk of bias. Not all pre‐defined, or clinically relevant and reasonably expected outcomes are reported, or are not reported fully, or it is unclear whether data for these outcomes were recorded or not.

high risk of bias. One or more of the clinically relevant and reasonably expected outcomes were not reported; data on these outcomes were likely to have been recorded.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Prevention with mixed nutritional supplements: mixed nutritional supplement versus standard hospital diet.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Incidence of pressure ulcers | 8 | 6062 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.73, 1.00] |

Comparison 2. Prevention with mixed nutritional supplements: disease‐specific (abnormal glucose tolerance) enteral nutritional formula versus standard high‐carbohydrate feeding.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Incidence of pressure ulcers | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.37, 1.57] |

Comparison 3. Prevention with mixed nutritional supplements: high‐fat, low‐carbohydrate, enteral formula enriched in lipids (eicosapentanoicacid (EPA)), gamma‐linolenicacid (GLA), vitamins A, C and E versus high‐fat, low‐carbohydrate, enteral formula.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Incidence of pressure ulcers | 1 | 95 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.37, 1.97] |

Comparison 4. Treatment with mixed nutritional supplements: arginine‐enriched mixed nutritional supplement versus standard hospital diet.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 PUSH score | 3 | 80 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐3.18 [‐4.80, ‐1.56] |

| 2 Number of people healed | 1 | 28 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.01, 6.60] |

| 3 Ulcer size | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Ulcer size (absolute) | 2 | 71 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.20 [‐9.80, 1.40] |

Comparison 5. Treatment with mixed nutritional supplements: high‐energy high‐protein mixed nutritional supplement versus standard hospital diet.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 PUSH score | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 PUSH Score (absolute) | 1 | 8 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.0 [‐4.76, 2.76] |

Comparison 6. Treatment with mixed nutritional supplements: High energy tube feeding versus standard energy tube feeding.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of people healed | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.41 [0.14, 1.23] |

Comparison 7. Treatment with mixed nutritional supplements: high‐fat, low‐carbohydrate, enteral formula enriched in lipids (eicosapentanoicacid (EPA)), gamma‐linolenicacid (GLA), vitamins A, C and E versus high‐fat, low‐carbohydrate, enteral formula.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of people healed | 1 | 95 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.88 [0.18, 20.01] |

Comparison 8. Treatment: ascorbic acid versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of people healed | 2 | 108 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.38, 2.10] |

| 1.1 nursing home patients | 1 | 88 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.77, 1.99] |

| 1.2 surgical patients | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.17, 1.46] |

| 2 Mean surface reduction (%) at 1 month | 1 | 20 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐41.3 [‐62.11, ‐20.49] |

Comparison 9. Treatment with proteins: concentrated, fortified, collagen protein hydrolysate supplement versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 PUSH score | 1 | 71 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.33 [‐1.74, 2.40] |

Comparison 10. Treatment with proteins: ornithine alpha‐ketoglutarate versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Ulcer size | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Ulcer size development (absolute) | 1 | 93 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.60 [‐1.90, 0.70] |

| 1.2 Ulcer size development (relative) | 1 | 93 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.5 [‐34.04, 23.04] |

| 2 Adverse events related to the study intervention | 1 | 160 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.89 [0.81, 4.39] |

Comparison 11. Treatment: zinc sulphate versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pressure ulcer healing: changes in pressure ulcer volume (ml) | 1 | 20 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.1 [‐16.30, 8.10] |

| 2 Number of people healed | 1 | 13 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.07, 10.96] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Arias 2008.

| Methods | RCT, open‐label. Duration: 17 months, from May 2005‐September 2006. |

|

| Participants | Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) performed for 1700 hospital patients, 667 of whom had mild or serious malnutrition or were suspected of being malnourished (i.e. SGA status = B or C) and were included in the trial. Exclusion criteria: diabetes mellitus, decompensated liver disease with hepatic encephalopathy, impaired consciousness, impaired comprehension. Patients analysed (Drop out 130 patients): A) Intervention group (n = 264): 36.4% female, 63.6% male, mean age 62.0 years ± 18.8 (SD). B) Control group (n = 273): 63.1% female, 36.9% male, mean age 58.8 years ± 19.8 (SD). |

|

| Interventions | A) Nutritional intervention group (n = 264): standard hospital diet + oral supplement (with 1 kcal/ml; 14.0% protein; 31.5% fat; 54.5% carbohydrate) up to 700 ml/d. B) Control group (n = 273): standard hospital diet. |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Mortality. 2. Duration of hospital stay. 3. Complications. Outcomes 1‐3 were not considered in this review, except for incidence of pressure ulcers, which was considered to be a complication. |

|

| Notes | Location: Uruguay. Setting: hospital. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No allocation concealment intended. |