Abstract

Background

The accessibility of health services is an important factor that affects the health outcomes of populations. A mobile clinic provides a wide range of services but in most countries the main focus is on health services for women and children. It is anticipated that improvement of the accessibility of health services via mobile clinics will improve women's and children's health.

Objectives

To evaluate the impact of mobile clinic services on women's and children's health.

Search methods

For related systematic reviews, we searched the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE), CRD; Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA), CRD; NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), CRD (searched 20 February 2014).

For primary studies, we searched ISI Web of Science, for studies that have cited the included studies in this review (searched 18 January 2016); WHO ICTRP, and ClinicalTrials.gov (searched 23 May 2016); Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), part of The Cochrane Library.www.cochranelibrary.com (including the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group Specialised Register) (searched 7 April 2015); MEDLINE, OvidSP (searched 7 April 2015); Embase, OvidSP (searched 7 April 2015); CINAHL, EbscoHost (searched 7 April 2015); Global Health, OvidSP (searched 8 April 2015); POPLINE, K4Health (searched 8 April 2015); Science Citation Index and Social Sciences Citation Index, ISI Web of Science (searched 8 April 2015); Global Health Library, WHO (searched 8 April 2015); PAHO, VHL (searched 8 April 2015); WHOLIS, WHO (searched 8 April 2015); LILACS, VHL (searched 9 April 2015).

Selection criteria

We included individual‐ and cluster‐randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and non‐RCTs. We included controlled before‐and‐after (CBA) studies provided they had at least two intervention sites and two control sites. Also, we included interrupted time series (ITS) studies if there was a clearly defined point in time when the intervention occurred and at least three data points before and three after the intervention. We defined the intervention of a mobile clinic as a clinic vehicle with a healthcare provider (with or without a nurse) and a driver that visited areas on a regular basis. The participants were women (18 years or older) and children (under the age of 18 years) in low‐, middle‐, and high‐income countries.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of studies identified by the search strategy, extracted data from the included studies using a specially‐designed data extraction form based on the Cochrane EPOC Group data collection checklist, and assessed full‐text articles for eligibility. All authors performed analyses, 'Risk of bias' assessments, and assessed the quality of the evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

Main results

Two cluster‐RCTs met the inclusion criteria of this review. Both studies were conducted in the USA.

One study tested whether offering onsite mobile mammography combined with health education was more effective at increasing breast cancer screening rates than offering health education only, including reminders to attend a static clinic for mammography. Women in the group offered mobile mammography and health education may be more likely to undergo mammography within three months of the intervention than those in the comparison group (55% versus 40%; odds ratio (OR) 1.83, 95% CI 1.22 to 2.74; low certainty evidence).

A cost‐effectiveness analysis of mammography at mobile versus static units found that the total cost per patient screened may be higher for mobile units than for static units. The incremental costs per patient screened for a mobile over a stationary unit were USD 61 and USD 45 for a mobile full digital unit and a mobile film unit respectively.

The second study compared asthma outcomes for children aged two to six years who received asthma care from a mobile asthma clinic and children who received standard asthma care from the usual (static) primary provider. Children who receive asthma care from a mobile asthma clinic may experience little or no difference in symptom‐free days, urgent care use and caregiver‐reported medication use compared to children who receive care from their usual primary care provider. All of the evidence was of low certainty.

Authors' conclusions

The paucity of evidence and the restricted range of contexts from which evidence is available make it difficult to draw conclusions on the impacts of mobile clinics on women's and children's health compared to static clinics. Further rigorous studies are needed in low‐, middle‐, and high‐income countries to evaluate the impacts of mobile clinics on women's and children's health.

Keywords: Aged; Aged, 80 and over; Child; Child, Preschool; Female; Humans; Middle Aged; ; Asthma; Asthma/therapy; Child Health Services; Child Health Services/economics; Child Health Services/statistics & numerical data; Cost-Benefit Analysis; Mammography; Mammography/statistics & numerical data; Maternal Health Services; Maternal Health Services/economics; Maternal Health Services/statistics & numerical data; Mobile Health Units; Mobile Health Units/economics; Mobile Health Units/statistics & numerical data; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; United States

Plain language summary

Mobile clinics for women's and children's health

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this Cochrane Review was to assess the effects of mobile clinics on women’s and children’s health. Cochrane researchers searched for and analysed all relevant studies to answer this question.

Key messages

The review only included two studies. One included study showed that mobile clinics may increase the number of women who use mammography services, although the cost of mammography screening may be higher. The other study showed that mobile clinics may make little or no difference to children’s asthma symptoms, their use of medication and urgent care, or their caregivers’ quality of life. More studies are needed, including studies that measure the effect of mobile clinics on cost and on people’s access to healthcare, their satisfaction, health, and well‐being.

What was studied in the review?

In many settings, people have poor access to healthcare services because they live in remote or hard‐to‐reach areas. Women and children may find it very difficult to access health services because of financial or social circumstances.

One way to increase people’s access to healthcare services is by providing mobile clinics. A mobile clinic is a vehicle with a driver and clinical equipment, and is staffed by a healthcare provider, such as a doctor or nurse, that visits areas regularly to provide health services.

Mobile clinics are used in many countries and are often used to offer health services to women and children, such as antenatal care, childhood immunisation, family planning services, and breast cancer screening.

By taking health services to the community through mobile clinics, governments hope to increase the use of these services and improve people’s health. This Cochrane review aimed to explore the effect of mobile clinics on people’s access to and use of health care and on their satisfaction, health, and well‐being; as well as their cost and cost effectiveness, compared to permanent clinics.

What are the main results of the review?

The review authors included two studies, which were from the USA.

In the first study, women were either offered health education and mammography screening in mobile clinics or health education only including reminders to attend a permanent clinic that offered mammography screening. The study showed that:

· women offered mammography in mobile clinics may be more likely to undergo mammography (low certainty evidence);

· the cost of screening per woman may be higher for mobile clinics than for permanent clinics (low certainty evidence).

This study did not assess the effect of the mobile clinics on women’s health and well‐being, their access to services or their satisfaction with these services.

In the second study, children were offered asthma care either at mobile clinics or at their usual primary care provider. This study showed that mobile clinics:

· may make little or no difference to the children’s asthma symptom‐free days or their use of urgent care and medication (low certainty evidence);

· may make little or no difference to the quality of life of the children’s caregivers (low certainty evidence).

The study did not assess the effect of the mobile clinics on children’s access to services or their satisfaction with these services, or on the cost and cost‐effectiveness of using the mobile clinics.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies that had been published up to April 2015.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Mobile clinics versus static clinics for mammography screening.

| Immediate onsite mobile mammography with health education versus health education only (including reminders to attend a static clinic service for mammography) | |||||

| Participant or population: women aged 60 to 84 years at study entry. (Age of participants matches our selection criteria) Settings: High income country; USA (California) Intervention: mobile clinic ‐ women were offered immediate onsite mobile mammography with health education Comparison: static clinic ‐ women received health education only and were encouraged to have a mammogram at the usual static clinic | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Static clinic | Mobile clinic | ||||

| Health status and well‐being | The study did not assess this outcome | ||||

| Health behaviour: self‐reported mammography uptake (follow‐up: 3 months) | Study population | OR 1.83 (1.22 to 2.74) | 473 (1)1 | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Low 2 |

|

| 382 per 1000 | 531 per 1000 | ||||

| Utilisation, coverage or access | The study did not assess this outcome | ||||

| Resource use: total cost per patient receiving mammography screening | The total cost per patient screened may be higher for mobile units than for stationary units (USD 41 for a stationary full digital screening unit; USD 102 for a mobile full digital screening unit; and USD 86 for mobile film screening unit). This evidence was of low certainty (⊕⊕⊖⊖)2 | ||||

| Satisfaction with care among healthcare recipients | The study did not assess this outcome | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; OR: odds ratio; GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: this research provides a very good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different3 is low. Moderate certainty: this research provides a good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different3 is moderate. Low certainty: this research provides some indication of the likely effect. However, the likelihood that it will be substantially different3 is high. Very low certainty: this research does not provide a reliable indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different3 is very high. | |||||

1Naeim 2009. 2We downgraded the quality of the evidence by 2 levels as we judged the study to be at moderate risk of bias and there was some imprecision around the estimate. 3Substantially different: a large enough difference that it might affect a decision

Summary of findings 2. Mobile clinics versus standard static services for childhood asthma care.

| Mobile clinics compared with standard 'static' services for childhood asthma care | |||

|

Paticipannt or population: children aged 2 to 6 years with persistent asthma and their caregivers. (Age of participants matches our selection criteria) Settings: High income country; USA (Baltimore) Intervention: mobile asthma clinic delivering screening, evaluation, and treatment services Comparison: static services comprising standard asthma care from the usual primary care provider | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Health status and well‐being (follow‐up: 12 months) |

Children who receive asthma care from a mobile asthma clinic may experience little or no difference in symptom‐free days and urgent care use, compared to children who receive standard asthma care. There may be little or no difference in quality of life among caregivers of children who receive asthma care from a mobile asthma clinic, compared to caregivers of children who receive standard asthma care. |

322 (1)1 |

Low 2 ⊕⊕⊖⊖ |

| Health behaviour (follow‐up: 12 months) |

There may be little or no difference in caregiver‐reported medication use among children who receive asthma care from a mobile asthma clinic compared to children who receive standard asthma care. | 322 (1)1 |

Low 2 ⊕⊕⊖⊖ |

| Utilisation, coverage or access | The study did not assess this outcome | ||

| Resource use | The study did not assess this outcome | ||

| Satisfaction with care among health care recipients | The study did not assess this outcome | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; OR: odds ratio; GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: this research provides a very good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different3 is low. Moderate certainty: this research provides a good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different3 is moderate. Low certainty: this research provides some indication of the likely effect. However, the likelihood that it will be substantially different3 is high. Very low certainty: this research does not provide a reliable indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different3 is very high. | |||

1Eakin 2012. 2We downgraded by two levels because we judged the study as at moderate risk of bias and due to imprecision. 3Substantially different: a large enough difference that it might affect a decision.

Background

Description of the condition

The accessibility of health services is an important factor that affects the health outcomes of populations. Several approaches have been employed to increase geographical healthcare coverage and utilisation, including building new facilities and use of outreach clinical services.

However, in many settings the building of new health centres and other facilities is not always feasible and does not necessarily result in more people receiving better services. For example, initiatives by governments, non‐governmental organisations (NGOs), and community self‐help schemes have often led to an increase in the building of health facilities. However, a study in Zimbabwe concluded that in some circumstances it was more economical to bring health staff to patients than vice versa, and that choosing geographically more optimal sites (i.e. further away from static clinics) would increase the cost‐effectiveness of outreach clinics (Vos 1990). Community‐based distribution programmes and mobile clinics are the most common outreach clinical services globally. Mobile clinics are used in a wide range of low‐ and middle‐income countries, e.g. in Nigeria (Onyia 1981), Thailand (Sriamporn 2006), Indonesia (Molyneaux 1988), and Egypt (El‐Zanaty 2001).

Description of the intervention

Mobile clinics have been widely used worldwide for many years. These clinics provide a wide range of services but their main focus in most countries is on health services for women and children. A mobile clinic is a clinic vehicle with a healthcare provider, such as a doctor or nurse, and a driver that visits areas on a regular basis (e.g. weekly, biweekly, or monthly) to provide health services.

Such services can enhance accessibility by providing services to underserved populations; they may therefore increase the potential to reach women and children who are underserved by static health services (ACCP 2004). For example, expanding access to contraceptives through mobile clinics can contribute to improving health by helping to reduce rates of unintended pregnancy and its associated morbidity and mortality (Welsh 2006).

In the USA, mobile clinics are used for screening for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) counselling (Ellen 2003), prenatal care (Edgerley 2007), and breast cancer screening (Skinner 1995). In Nigeria, mobile under‐fives clinics (clinics for children under five years old) provide health education, immunisation, malarial chemoprophylaxis, and regular weight monitoring (Onyia 1981). In Egypt, it was planned that mobile clinics should offer family planning services, antenatal care services, and counselling, examination, and investigation for some diseases, e.g. hepatitis B, HIV/autoimmune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), and health care for menopausal women. However, the main services offered by mobile clinics for the last 10 years have been restricted to family planning, antenatal care, and, occasionally, immunisation (El‐Zanaty 2001).

How the intervention might work

Mobile clinics could tackle some barriers of access proposed by various frameworks especially availability, geographic accessibility (distance between service location and households), and utilisation of health services (Jacobs 2012). It is anticipated that improvement of access would have a positive impact on the health of specific groups. For example, increased accessibility to family planning services for women may increase the use of effective contraceptive methods and reduce the number of unwanted pregnancies and illegal abortions. Similarly, increased accessibility to antenatal care may result in earlier diagnosis and referral of high‐risk pregnancies and better care for women with normal pregnancies, and so decrease the risk of having low birthweight babies (O'Connell 2010). Mobile clinics also could play a vital role in increasing utilisation of cervical cancer screening and raising awareness among women about importance of early detection of cervical cancer (Swaddiwudhipong 1995). For children, increased vaccination coverage and regular nutritional assessment may result in decreased infant and child morbidity and mortality in the long term.

Why it is important to do this review

Mobile clinics play an important role in offering services to vulnerable groups (i.e. women and children) living in remote or difficult‐to‐access areas where their access to health services is poor. Previous studies have suggested that mobile clinics may have the potential to increase access to antenatal care (Edgerley 2007; O'Connell 2010), immunisation, malaria chemoprophylaxis, and regular monitoring of weight (Onyia 1981), and may also have the potential to increase utilisation of breast cancer screening (Skinner 1995), cervical cancer screening (Swaddiwudhipong 1995), and screening for STDs and HIV counselling (Ellen 2003).

However, despite the wide use of mobile clinics across a range of settings, there is ongoing debate regarding their use compared to static clinics (Mercer 2005). For example, in Thailand mobile services were more heavily utilised than static services, which may be because these mobile services were more accessible and acceptable to women (ACCP 2004). In contrast, in rural areas of other countries, such as Bangladesh (Mercer 2005), and Egypt (El‐Gibaly 2008), static clinics were preferred by women to satellite clinics. In Bangladesh, women who were dissatisfied with the mobile clinics reported lack of medicines and unavailability of some services. In Egypt, static clinics were preferred because women perceived that the quality of family planning services offered by the static clinics is better than that offered by mobile clinics. In addition, continuity of care offered in the static clinics and availability of health provider on a daily basis were other causes for static clinic preferences (El‐Gibaly 2008). In Egypt, a national strategic plan has been adopted for the period 2007 to 2017 and includes provision of fee‐waiver family planning/reproductive health services using mobile clinics. The intention of this plan is to make these services accessible in areas not served by static clinics (El‐Zanaty 2001). Women and children are vulnerable and high risk groups. They may, in some low‐ and middle‐income countries, have limited mobility and therefore have difficulties accessing health services. Bringing the service to them may therefore have a greater impact on their health than on the health of other population groups, such as men, in the same countries.

In addition, the inclusion of economic evaluation has become an increasingly accepted component of health policy and planning. A number of country experiences have shown that information on the cost‐effectiveness of health interventions can be used alongside other types of information to inform different policy decisions (Hutubessy 2003). Also, information about cost‐effectiveness can guide policy makers to make the right judgements and address inequities based on the evidence presented from cost‐effectiveness studies about the pros and cons of the different policies and programmes (Oxman 2009). This is of particular importance in countries where health care demand exceeds supply and where resources for healthcare provision are very limited. For example, in Egypt the cost per client at a mobile clinic is lower than that at static clinics. However, reproductive health services offered by mobile clinics were used by only 6% of the target communities (women living in remote rural areas), which may reduce their cost‐effectiveness (El‐Gibaly 2008).

Objectives

To evaluate the impact of mobile clinic services on women's and children's health.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included the following study designs:

individual‐ and cluster‐randomised controlled trials (RCTs);

individual and cluster non‐randomised studies;

controlled before‐and‐after (CBA) studies that included at least two intervention sites and two control sites;

interrupted time series (ITS) studies with a clearly defined point in time; when the intervention occurred and at least three data points before and three after the intervention.

Types of participants

We included women (defined as aged 18 years or more) and children (from birth until the age of 18 years) in low‐, middle‐, and high‐income countries.

Types of interventions

A mobile clinic is a clinic vehicle (with a healthcare provider) that visits areas on a regular basis (e.g. weekly, every two weeks , or monthly) to provide health services. We assessed mobile clinics for their effectiveness in providing services to women and children. These services include promotive, preventive, and curative care for women and children, and might involve antenatal care, postnatal care, screening for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), screening for breast and cervical cancer, screening for osteoporosis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) counselling, family planning, vaccination of children, and regular weight monitoring of children.

We compared:

mobile clinic services versus no services;

mobile clinic services versus static clinics;

combined mobile and static clinic services versus static clinics.

We excluded mobile clinics that provided services exclusively to men over the age of 18 years (since the interventions and outcomes of interest were related only to women and to children under the age of 18 years) and mobile clinics used in emergencies (such as in earthquakes). We didn't include outreach workers that used other means of transportation (e.g. bikes) to deliver e.g. family planning methods. This was because a mobile clinic is able to offer a different, and generally wider, range of services in a different way, compared to using a bike to reach a particular areas to deliver care. For example, the structure of a mobile clinic is often similar to that of a static clinic, and the mobile facility is usually staffed by a health professional trained to deliver a range of curative, promotive, and preventive services and with access in the mobile clinic to the equipment needed to undertake these activities (e.g. an ultrasound machine, instruments for examination, etc). In contrast, outreach workers who use other forms of transportation generally do not have access to this range of equipment and supplies. Also, we excluded a temporary clinic structure that was not mobile, but whose health workers only visited once a week (for example) to provide services to a particular community. Moreover, other types of outreach services are dealt with in other reviews, e.g. the Gruen 2003 review on specialist outreach clinics in primary care and rural hospital settings.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Health outcomes: participant outcomes were:

health status and well‐being, including number of cases diagnosed, treated, or referred for treatment, including cases of STDs, high‐risk pregnancies, malnutrition among children and infectious diseases among children;

health behaviour: any measure of the extent to which service users adhered to recommended care plans. For example, for women, whether they attended for the recommended number of antenatal visits, and for children, whether they completed the vaccination schedule at the designated time;

-

utilisation, coverage, or access: we used coverage and service utilisation as proxies for the impact of health services on the health of women and children. Measures included:

contraceptive prevalence;

vaccination coverage among children;

use of other services provided by mobile clinics (e.g. osteoporosis screening, antenatal care, postnatal care, screening for STDs, screening for breast and cervical cancer, HIV counselling, regular weight monitoring of children etc.);

-

resource use, including:

cost‐effectiveness of services offered by the mobile clinics in comparison to static clinics.

Secondary outcomes

Satisfaction (assessed in any way) of healthcare recipients with care.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases for related systematic reviews:

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE), Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) (searched 20 February 2014)

Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA), Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) (searched 20 February 2014)

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) (searched 20 February 2014)

We searched the following databases, with no language or date restrictions, for primary studies:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2015, Issue 3, part of The Cochrane Library.www.cochranelibrary.com (including the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group Specialised Register) (searched 7 April 2015)

MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, MEDLINE Daily, MEDLINE and OLDMEDLINE 1946 to Present, OvidSP (searched 7 April 2015)

Embase 1980 to 2015 Week 14, OvidSP (searched 7 April 2015)

CINAHL 1980 to present, EbscoHost (searched 7 April 2015)

Global Health 1973 to 2015 Week 13, OvidSP (searched 8 April 2015)

POPLINE, K4Health (searched 8 April 2015)

Science Citation Index and Social Sciences Citation Index 1975 to present, ISI Web of Science (searched 8 April 2015)

Global Health Library (GHL), Regional Indexes, Word Health Organization (WHO) (searched 8 April 2015)

Pan American Health Organization database (PAHO), Virtual Health Library (VHL) (searched 8 April 2015)

World Health Organization Library Information System (WHOLIS), WHO (searched 8 April 2015)

Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences database (LILACS), Virtual Health Library (VHL) (searched 9 April 2015)

Searching other resources

Trial registries

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), Word Health Organization (WHO): www.who.int/ictrp/en (searched 23 May 2016)

ClinicalTrials.gov, US National Institutes of Health (NIH): clinicaltrials.gov (searched 23 May 2016)

Other sources

We also:

reviewed the reference lists of relevant systematic reviews and studies

conducted a cited reference search for all included studies using Science Citation Index and Social Sciences Citation Index 1975 to present, and Emerging Sources Citation Index 2015 to present, ISI Web of Science (searched 18 January 2016)

See Appendix 1 for the search strategies we used.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of studies identified by the search strategy to assess which studies met the inclusion criteria. We obtained the full‐text articles of potentially eligible studies. Two review authors (AF and GS) assessed the full‐text articles against the inclusion criteria of this review. Whenever there was uncertainty or disagreement, we reached consensus by discussion among the review authors (HAA). All full‐text articles that were excluded after full‐text assessment are listed in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted details of study design, population, intervention, and comparison, and outcome data from included articles using a specially‐designed data extraction form based on the Cochrane EPOC Group data collection sheet.

The extracted data included:

participant characteristics (age, gender, education, ethnicity, health issues, etc.) and number of participants included in the study;

intervention characteristics (description of the mobile clinic including staffing, drugs, equipment, number of visits to the target area etc.) and comparison static clinic characteristics in the same terms. These descriptions also included the characteristics of the healthcare providers in both types of clinics (age, gender, profession, level of training, etc.) whenever reported in the included studies;

the setting (urban/rural) and description of other services provided in the served communities;

the country (low‐, middle‐, or high‐income);

description of the outcomes, timing of outcome assessment, and outcome data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias of each included study using the nine standard Cochrane EPOC criteria and the seven standard criteria for ITS studies (EPOC 2015; Appendix 1). Judgements on the overall risk of bias took into account the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered that the bias impacted on the findings. We assessed studies to be at high risk of bias if they scored 'high risk' in one or more of the following domains: sequence generation; allocation concealment; or selective outcome reporting (based on growing empirical evidence that these three factors are the most important in influencing risk of bias) (Higgins 2011). We judged the overall risk of bias as low if we assessed these key domains as at low risk of bias; unclear if one or more key domains were at unclear risk of bias; and high if one or more key domains were at high risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, we had planned to use risk ratios (relative risk). For continuous outcomes measured in the same way, we had planned to use the mean difference. We had planned to use the standardised mean difference to combine the data from trials that measured the same outcome using different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

We used the odds ratio (OR) of the non‐randomised studies because it accounted for clustering in data. For example, in Reuben 2002, the primary analysis adjusted for correlation of observations within sites (cluster effect) using the Huber method (inflating the standard errors), which is a non‐parametric correction independent of observations when estimating the sample variance.

However, Eakin 2012 used a generalised estimating equation (GEE) to estimate the group population average for each outcome over time to control for the correlation among longitudinal measures within an individual, while adjusting for baseline level of each outcome.

In future updates, we may need to re‐analyse cluster‐RCTs if clusters were not taken into consideration during analysis. We will re‐analyse each study if it is possible to extract the following information from the trial report:

the number of clusters (or groups) randomised to each intervention group, or the average (mean) size of each cluster;

the outcome data ignoring the cluster design for the total number of individuals (e.g. number or proportion of individuals with events, or means and standard deviations (SDs));

an estimate of the intracluster (or intraclass) correlation coefficient (ICC).

We will present the point estimate of effect without any measure of uncertainty, and will note the presence of unit of analysis errors.

Dealing with missing data

We assumed that data were missing at random (as judged by the authors of each included study, i.e. missing due to refusal, or dropout). Therefore we analysed the available data only (and ignored the missing data).

In future updates, if we assume that data were not missing at random (as judged from the sociodemographic characters of the study participants compared to the outcome results in the same paper and the authors' justification for selecting a certain group versus another), whenever possible we will contact the original study investigator for missing data. In case of missing summary statistics (e.g. SDs), we will look for other statistics within each study to calculate the SD.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We were unable to assess heterogeneity as only two studies (three articles) met the inclusion criteria of this review. In future updates, we will assess clinical heterogeneity across the non‐randomised studies based on differences in populations, interventions, comparisons, and outcomes.

We will assess statistical heterogeneity using the T² value, the I² statistic, and the Chi² test and also using visual interpretation of forest plots. We will consider heterogeneity substantial where the T² value is greater than zero, and either the I² statistic is greater than 50% or there is a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. We will explore any heterogeneity (see the 'Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity' section below).

Assessment of reporting biases

We were unable to assess publication bias as only two studies (three articles) met the inclusion criteria. In future updates of this Cochrane review, we will assess publication bias using a funnel plot provided that there are 10 or more studies included in an analysis. We will judge publication bias to exist when we detect asymmetry in the funnel plot.

We assessed selective outcome reporting bias in each included study by comparing the outcomes reported in the results to those previously specified in the methodology section. Also we assessed this by checking whether the outcomes reported included those expected to have been measured in the study, based on the research question if the study protocol was unavailable.

In future updates, and provided that the study protocols are available, we will assess reporting bias by comparing if all of the prespecified (primary and secondary) outcomes list in the protocol are also reported in the published study. Where study protocols are unavailable, we will assess selective outcome reporting as above.

Data synthesis

Due to the small number of included studies and different outcomes reported, we were unable to perform data synthesis. In future updates of this review, we will group and compare studies according to similar outcome measures, e.g. non‐randomised studies that report contraceptive prevalence rate, vaccination coverage, percentage of breast cancer screened women, percentage of women with osteoporosis, etc. We will use a random‐effects model for meta‐analysis, based on the assumption that the true effects measured across non‐randomised studies are related but not the same due to differences in population, intervention, and setting. If studies are not sufficiently homogeneous to combine in a meta‐analysis, we will present the results of included studies in a forest plot but will not present the pooled estimate.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In future updates, we will investigate heterogeneity even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. We plan to perform the following subgroup analyses:

gender of the health care provider(s) that offers services to women included in the study, as the gender of the healthcare provider may affect the acceptability of the service and seeking of health care;

whether the study was conducted in a low‐, middle‐, or high‐income country as the socioeconomic level within the country may affect the quality and level of services offered by the mobile clinics;

the geographical setting of the study as living in a rural or urban area may affect the accessibility of the mobile clinic and may also affect quality.

Sensitivity analysis

In future updates of this review, we will conduct sensitivity analyses based upon the following to determine how robust and consistent the results are:

exclusion of all non‐RCTs;

exclusion of studies at high risk of bias (assessed using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool described above);

exclusion of studies where we have obtained additional data from the study investigators;

variation of the ICC used to re‐analyse data from cluster‐RCTs

exclusion of data from studies that were re‐analysed.

'Summary of findings' tables

We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to assess the quality of evidence related to each of the key outcomes. We created 'Summary of findings' tables using the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool (GDT) (available from www.gradepro.org). As we only had the complete information from one included study (Reuben 2002), we assessed the quality of the evidence for this study only and included it in the 'Summary of findings' table.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search retrieved 9516 records. There were 6910 after we removed duplicates. We screened 6910 records by title and abstract, and excluded 6820 articles. We assessed 90 full‐text articles for eligibility. We excluded 84 studies and three studies are awaiting classification while 3 articles (constitute 2 studies) were included. The reasons for exclusion: studies had an ineligible study design (n = 63); used an ineligible interventions (n = 16); were reviews rather than primary studies (n =5) (see Characteristics of excluded studies). We have presented this information in the study flow diagram in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Two studies met the inclusion criteria of this review (Reuben 2002; Eakin 2012). Another published paper, Naeim 2009, was a cost‐effectiveness analysis and a secondary analysis of data collected in Reuben 2002. It focused on the cost‐effectiveness of the intervention.

Reuben 2002 is a cluster‐randomised controlled trial (RCT) that tested whether the offer of immediate, onsite, mobile mammography combined with health education was effective at increasing breast cancer screening rates versus health education alone, including encouragement to have a mammogram at the typical static clinic. The study randomised 60 community‐based meal sites, senior centres, and clubs in California, USA to either health education only or health education plus onsite mobile mammography over a two‐year period. There were 463 female participants (aged 60 to 84 years at study entry): 235 were offered health education and onsite mobile mammography and 228 received health education only.

The exclusion criteria of this study included recent mammography (within the past year), no telephone, inability to speak English or Spanish, and limited cognitive capacity to participate in the study (based on failure to be oriented to the date and day of the week, and inability to place numbers appropriately on an outline of a clock). The study assessed self‐reported mammography after three months through telephone interviews.

A secondary analysis, Naeim 2009, examined the cost‐effectiveness of mammography at mobile versus static (stationary) units.

The second included study was a cluster‐RCT that evaluated whether a 'Breathmobile' clinic would improve asthma outcomes compared to standard care, a static clinic (Eakin 2012). 'Head Start' programme sites in Baltimore, USA (66 sites in total) were the units of randomisation, while children were the unit of analysis. The Breathmobile is a mobile asthma clinic that delivers asthma screening, evaluation, and treatment services directly to inner city children at their schools or at the Head Start sites. A specially trained nurse practitioner, allergist, nurse, and driver/patient assistant provide care on the Breathmobile. The study included 322 children aged two to six years of age with persistent asthma. Eligibility criteria included caregiver reported physician diagnosed asthma or reactive airways disease and at least one of the following:

use of short acting beta agonist in the past four weeks;

asthma symptoms in the past four weeks; or

treated in the emergency department (ED) for asthma in past six months.

The study included both male and female children, and most participants were African‐American (more than 97%) in the two trial arms relevant to this review. Most children belonged to low‐income families.

Eakin 2012 included the following outcome measures:

symptom‐free days (SFD). This primary outcome was calculated by subtracting the number of days, or nights, or both, with asthma symptoms (i.e. cough, wheeze, shortness of breath) in the past 30 days, as reported by caregivers;

acute care and medication use. This measure included caregiver reports of ED visits, hospitalisations, prescribed asthma controller medication regimen (e.g. inhaled corticosteroid and leukotriene modifiers), and courses of oral corticosteroids in the previous six months;

caregiver quality of life. The study used the Pediatric Asthma Caregiver's Quality of Life Questionnaire (PACQLQ), which is a 13‐item measure of activity limitations (four items) and emotional function (nine items) experienced by caregivers of asthmatic children. Responses on the PACQLQ are given on a 7‐point scale where 1 represents severe impairment and 7 represents non‐impairment. Higher scores indicate higher quality of life.

Excluded studies

We excluded 82 articles due to ineligible study design (n = 62); failure to meet our intervention definition (n = 16), or because they were not primary studies (n = 4) (see the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table).

Risk of bias in included studies

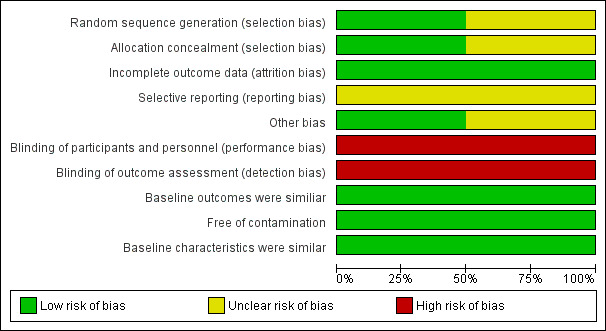

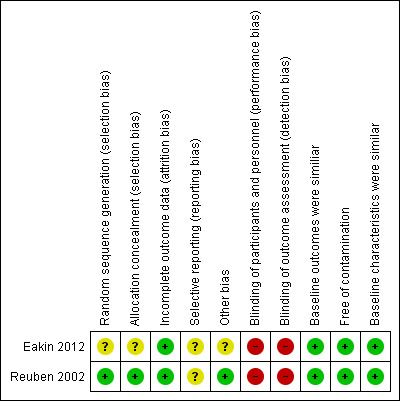

We have presented a summary of the 'Risk of bias' assessments in Figure 2 and Figure 3, and provided the detailed assessments in the 'Characteristics of included studies' tables. Overall, we assessed the two included studies as at moderate risk of bias.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item for each included study.

Allocation

We assessed Reuben 2002 as at low risk of selection bias. Eakin 2012 was at unclear risk of bias as the study did not report adequately on how sequence generation was determined.

Blinding

In Reuben 2002 blinding of the participants and research associates was not possible (high risk of bias). The study reported that "on the day of the program, the presence or absence of the mobile mammography van revealed to participants which intervention group they had been assigned. For the same reason, the research associates administering the interventions also were aware of participants intervention status. While blinding was assured for outcome assessment since the outcomes assessor was unaware of the intervention group status of all participants”. The study used telephone interviews to ask women whether they had undergone mammography.

In Eakin 2012, blinding of the participants to the intervention could not be assured (high risk of bias); the study reports that the Breathmobile was present only at those Head Start sites assigned the Breathmobile. However, outcome assessment was blinded since the research assistants that conducted follow‐up telephone surveys were unaware of participants' group assignment.

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed the risk of attrition bias as low in both studies since the proportion of missing data was similar in the intervention and control groups.

Selective reporting

Selective reporting bias was unclear in both included studies. Although the studies reported all outcomes listed in the methods section in the results section, we were unable to assess the study protocols (unavailable).

Other potential sources of bias

For cluster‐RCTs, we assessed the following potential sources of bias.

Recruitment bias

Individuals were most likely recruited to the trial after the clusters had been randomised in both studies, but this was unclear for Eakin 2012.

Baseline characteristics

We assessed this as low risk as baseline characteristics were similar across intervention and control in the two included studies.

Loss of clusters

There was no evidence of loss of clusters in either study.

Incorrect analysis

We assessed Reuben 2002 as at low risk of bias as the study authors took clustering into consideration during the analysis using the Huber method (inflating standard errors). Eakin 2012 was unclear regarding this risk of bias item as the study authors used generalised estimating equations (GEE) but did not discuss adjustment for clustering explicitly.

Effects of interventions

Primary outcomes

1. Health outcomes

1.1 Health status and well‐being

One study, Eakin 2012, showed that children who receive asthma care from a mobile asthma clinic may experience little or no difference in symptom‐free days up to 12 months following the intervention versus children who receive standard asthma care from their primary care provider (low certainty evidence) (Table 2).

Eakin 2012 showed that children who receive asthma care from a mobile asthma clinic may experience little or no difference in urgent care use (including both emergency room use and hospitalisations) up to 12 months following the intervention versus children who receive standard asthma care from their primary care provider (low certainty evidence).

Eakin 2012 also assessed caregiver quality of life, and showed that there may be little or no difference in this measure at 12 months among caregivers of children who receive asthma care from a mobile asthma clinic compared to caregivers of children who receive standard asthma care from their primary care provider (low certainty evidence).

1.2 Health behaviour

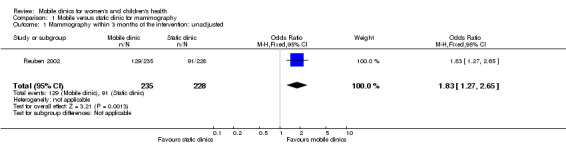

One study, Reuben 2002, showed that women offered immediate, mobile onsite mammography and health education may be more likely than those offered health education only (including encouragement to have a mammogram at any usual static clinic) to report undergoing mammography within three months of the intervention (55% versus 40%; OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.22 to 2.74; low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.1; unadjusted data only) (Table 1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Mobile versus static clinic for mammography, Outcome 1 Mammography within 3 months of the intervention: unadjusted.

The second included study, Eakin 2012, showed that there may be little or no difference in caregiver‐reported medication use at 12 months (including courses of oral steroids and prescriptions of inhaled corticosteroids) among children who receive asthma care from a mobile asthma clinic compared to children who receive standard asthma care from their primary care provider (low certainty evidence) (Table 2).

2. Utilisation, coverage, or access

None of the included studies assessed this outcome.

3. Resource use

Naeim 2009 reported a secondary cost‐effectiveness analysis of the data from Reuben 2002. This evaluation compared three types of screening program: stationary mammography units (with full digital film), mobile mammography with screen‐film, and mobile mammography with full digital film. The study included the following cost items: costs of equipment, mobile van, personnel, operating costs, processing and printing, and real estate costs. The study found that the total cost per patient screened was USD 41 for a stationary full digital unit, USD 102 for a mobile full digital unit, and USD 86 for mobile film unit. The study calculated the incremental cost per patient as the cost per mobile screening minus the cost per stationary screening. For mobile screening compared to screening at a stationary unit, the incremental cost per patient was USD 61 for a mobile full digital unit and USD 45 for a mobile film unit. For a mobile compared to a stationary unit, the incremental cost per screening was USD 264 for a mobile full digital unit and USD 207 for a mobile film unit. This evidence was of low certainty (Table 1).

Secondary outcomes

1. Satisfaction with care among healthcare recipients

None of the included studies assessed this outcome.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This Cochrane review aimed to assess the impact of mobile clinics that delivered services on any aspect of women's and children's health. However only two studies met the inclusion criteria. Reuben 2002 focused on mammography screening for women, and Eakin 2012 focused on care for children with asthma. Women who are offered mobile onsite mammography and health education may be more likely than those offered health education only to report undergoing mammography within three months of the intervention. However, the total cost per participant screened may be higher for mobile units than for stationary units. Children who receive asthma care from a mobile asthma clinic may experience little or no difference in symptom‐free days, urgent care use, and caregiver‐reported medication use versus children who receive standard asthma care from their usual primary care provider. In addition, there may be little or no difference in quality of life among caregivers of children who receive asthma care from a mobile asthma clinic compared to caregivers of children who receive standard asthma care. The certainty of the evidence was low for each of these outcomes.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This Cochrane review aimed to evaluate the impact of mobile clinic services on women's and children's health. However, the available evidence was limited, and both included studies were conducted in a high‐income country among quite specific populations (children aged two to six years with persistent asthma and older women who might be eligible for mammography screening). This limits the applicability of the evidence to low‐ and middle‐income country settings, as well as to other populations. Mobile clinic utilisation and impact may be influenced by a various number of factors, including the reasons for using mobile services (e.g. improving geographical access to a package of health services or increasing coverage of targeted interventions to a targeted population) and the context in which these services operate.

For a number of review outcomes, including utilisation, coverage, or access and satisfaction with care among healthcare recipients, little or no data were available. For other outcomes, the data available were sparse. Further rigorous studies are needed that both cover a range of settings, populations, and health issues and that assess a wide range of outcomes relevant to understanding the effects of mobile clinics.

This review considered studies with a wide range of designs for inclusion and is based on comprehensive searches, without language or publication status restrictions. We searched for randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non‐randomised studies, controlled before‐and‐after (CBA) studies, and interrupted time series (ITS) studies. We included this range of designs as randomisation may not be feasible for some mobile clinic interventions. However, non‐randomised studies, CBA, and ITS studies are not as well indexed as RCTs in electronic databases and it is possible that we may have missed some studies.

Certainty of the evidence

The 'Summary of findings' tables for the main comparisons summarise the certainty of the evidence for the key outcomes (Table 1; Table 2).

Using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, we assessed the certainty of the evidence as low. We judged both included studies as at moderate risk of bias overall and there was some imprecision around the estimate of effect (Reuben 2002; Eakin 2012). This suggests that the likelihood that the effect will be substantially different (i.e. the difference may be large enough to affect a decision) from that reported in the studies is high.

Potential biases in the review process

Identifying studies of mobile clinic interventions in electronic data base is challenging. However, our literature searches included many synonyms (mobile unit, mobile centres, mobile facilities, etc.) and we also searched a number of grey literature sources. Widening the scope of the eligible studies to include those carried out in high, middle or low income countries was an advantage to draw the attention to the absence of experimental studies evaluating the role of mobile clinics compared to the static clinics in low middle income countries.On the other hand, among the limitations which could be out of our control, is the possibility that we did not identify all eligible studies.The unpublished data were not obtained. Moreover, few outcomes were identified in the review compared to the proposed outcomes planned in the protocol. Many published papers evaluated the role of mobile clinic in offering maternal and child health services, however, because we limited our selection criteria to experimental designs only, none of the observational studies were included in this review. Another potential bias is that we excluded studies involving services offered to men which could have helped in better understanding the role played by the mobile clinics in improving health within communities and overcoming access barrier. However, we did exclude those studies because we were more interested in understanding mobile services offered to vulnerable populations (women and children) most.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Two other systematic reviews have explored the effects of mobile clinics. Mdege 2014 examined evidence on the use of mobile clinics to bring antiretroviral therapy closer to end users. The review did not identify any eligible studies on this topic. A second review, Vashishtha 2014, examined the use of mobile dental units. While Vashishtha 2014 identified a number of studies, none of these studies were eligible for inclusion in this Cochrane review as they did not meet our study design criteria.

We identified two other studies that evaluated the effects of mobile clinics for women's and child health but they did not use designs that were eligible for inclusion in this review (see the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table). One cohort study, O'Connell 2010, evaluated the difference in prenatal care utilisation and birth outcomes among demographically similar women who used, or did not use, a mobile van (on a regular schedule and equipped to deliver services for women) for prenatal care in Florida, USA. This study suggested that adequate prenatal care was higher for mothers that utilised a mobile van compared to those who did not. One ITS study evaluated the use of mobile clinics for cervical cancer screening in rural Thailand (Swaddiwudhipong 1995), but did not meet our ITS study eligibility criteria. This study suggested that knowledge about cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening, as well as ever being screened for cervical cancer, increased after implementation of the mobile clinic intervention. The findings of both of these studies should be viewed with caution as these studies used designs that are at high risk of bias.

The inclusion of an economic perspective in the evaluation of health and health care has become an increasingly accepted component of health policy and planning. A number of country experiences have shown that cost‐effectiveness information can be used alongside other types of information to guide policy makers who address inequities and make evidence‐based decisions (Oxman 2009), and thus aid different policy decisions (Hutubessy 2003). In this Cochrane review, one study included a cost‐effectiveness analysis (Reuben 2002). Although mobile mammography was more effective, the costs per screen were much higher in the mobile units compared with stationary units. Incremental cost per patient for a mobile over a stationary unit was USD 61 for a mobile full digital unit and USD 45 for a mobile film unit. Other studies have suggested that mobile clinics might be most cost effective in rural and remote areas. For example, a cost‐effectiveness analysis of mobile clinics used for screening for cervical cancer in Japan showed that these had the highest benefit‐cost ratio (1.20) and were more suitable for rural areas compared to a detection centre and a private physician program (Takenaga 1985). A cross‐sectional study from Tunisia also showed that a mobile clinic service was cost‐effective in delivering family planing services to remote rural areas (Coeytaux 1989). This study highlights that clinic output was positively associated with literacy of the population, the number of centres served by a unit, and the frequency with which centres were served in a month. These factors may be important considerations for future evaluations.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The limited evidence in this Cochrane review (only two small included studies) and the low certainty of the evidence makes it difficult to draw conclusions for practice in relation to mobile clinics for women's and children's health. Given these limitations, the results of this Cochrane review should be generalised with caution.

Implications for research.

We included only two studies in this Cochrane review, which were conducted in the USA. Therefore further well‐designed studies in low‐, middle‐, and high‐income countries are needed to evaluate the impacts of mobile clinics on women's and children's health. These studies should compare mobile clinic services with no services, mobile clinic services versus static clinics, and combined mobile and static clinic services versus static clinics. As far as possible, these studies should measure the full range of outcomes identified as important in this review and should address the impacts of mobile clinics on a wider range of health problems that affect women and children, including those living in both rural remote and urban settings. These studies should also assess resource use and cost effectiveness, given the importance of economic data in health policy and planning. Complementary studies that address the feasibility and acceptability of mobile clinic services in different settings would also be helpful.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the help and support of the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group. The authors would also like to thank the following editors and peer referees who provided comments to improve the review: Simon Lewin (Editor), Jesse Uneke (Editor), Claire Glenton (PLS Editor), Lesley Bamford (Peer referee), Marit Johansen (Information Specialist).

The Norwegian Satellite of the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group receives funding from the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad), via the Norwegian Institute of Public Health to support review authors in the production of their reviews.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

The Cochrane Central Register for Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

CENTRAL, the Cochrane Library

| ID | Search | Hits |

| #1 | MeSH descriptor: [Mobile Health Units] this term only | 64 |

| #2 | (mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) near/3 (unit or units or clinic or clinics or center or centers or centre or centres or facility or facilities or hospital or hospitals):ti,ab,kw | 171 |

| #3 | (mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) near/3 (service* or health* or medicine or care):ti,ab,kw | 293 |

| #4 | (mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) near/3 (examination* or health next exam* or medical next exam* or diagnos* or treatment* or treating or therapy or therapies or surgery or operation* or prevent* or screen or screening or "x ray" or counsel* or laborator* or test or tests or testing or biopsy or biopsies or checkup* or check next up* or mammogra* or ultrasound or ultra next sound or vaccin* or immunisation or immunization):ti,ab,kw | 158 |

| #5 | (mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) near/3 (health* next personnel or health next care next personnel or medical next personnel or health* next professional* or health next care next professional* or medical next professional* or health* next provider* or health next care next provider* or medical next provider* or practitioner* or doctor or doctors or physician* or nurse or nurses or midwif* or midwiv*):ti,ab,kw | 22 |

| #6 | (medical or health* or mobile or clinic or clinical) next (bus or buses or van or vans or car or cars or truck or trucks or automobile* or trailer or trailers or wagon or wagons or wheel or wheels or vehicle or vehicles):ti,ab,kw | 17 |

| #7 | mobile near/3 (outreach or out next reach):ti,ab,kw | 7 |

| #8 | (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7) in Trials | 388 |

MEDLINE, OvidSP

| # | Searches | Results |

| 1 | Mobile Health Units/ | 3020 |

| 2 | ((mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) adj3 (unit? or clinic? or center? or centre? or facility or facilities or hospital?)).ti,ab. | 2732 |

| 3 | ((mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) adj3 (service? or health* or medicine or care)).ti,ab. | 2728 |

| 4 | ((mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) adj3 (examination? or health exam* or medical exam* or diagnos* or treatment? or treating or therapy or therapies or surgery or operation? or prevent* or screen or screening or x ray or counsel* or laborator* or test or tests or testing or biopsy or biopsies or checkup? or check up? or mammogra* or ultrasound or ultra sound or vaccin* or immunisation or immunization)).ti,ab. | 2116 |

| 5 | ((mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) adj3 (health* personnel or health care personnel or medical personnel or health* professional? or health care professional? or medical professional? or health* provider? or health care provider? or medical provider? or practitioner? or doctor? or physician? or nurse or nurses or midwif* or midwiv*)).ti,ab. | 351 |

| 6 | ((medical or health* or mobile or clinic or clinical) adj (bus or buses or van or vans or car or cars or truck? or automobile? or trailer? or wagon? or wheel? or vehicle?)).ti,ab. | 250 |

| 7 | (mobile adj3 (outreach or out reach)).ti,ab. | 85 |

| 8 | or/1‐7 | 8421 |

| 9 | randomized controlled trial.pt. | 388691 |

| 10 | pragmatic clinical trial.pt. | 132 |

| 11 | controlled clinical trial.pt. | 88951 |

| 12 | multicenter study.pt. | 182178 |

| 13 | Non‐Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic/ | 13 |

| 14 | Interrupted Time Series Analysis/ | 23 |

| 15 | Controlled Before‐After Studies/ | 27 |

| 16 | (randomis* or randomiz* or randomly allocat* or random allocat*).ti,ab. | 421108 |

| 17 | groups.ab. | 1431338 |

| 18 | (trial or multicenter or multi center or multicentre or multi centre).ti. | 159093 |

| 19 | (intervention? or effect? or impact? or controlled or control group? or (before adj5 after) or (pre adj5 post) or ((pretest or pre test) and (posttest or post test)) or quasiexperiment* or quasi experiment* or pseudo experiment* or pseudoexperiment* or evaluat* or time series or time point? or repeated measur*).ti,ab. | 6819048 |

| 20 | or/9‐19 | 7591994 |

| 21 | exp Animals/ | 17805413 |

| 22 | Humans/ | 13794328 |

| 23 | 21 not (21 and 22) | 4011085 |

| 24 | review.pt. | 1954177 |

| 25 | meta analysis.pt. | 54332 |

| 26 | news.pt. | 167676 |

| 27 | comment.pt. | 618973 |

| 28 | editorial.pt. | 373544 |

| 29 | cochrane database of systematic reviews.jn. | 11153 |

| 30 | comment on.cm. | 618973 |

| 31 | (systematic review or literature review).ti. | 58811 |

| 32 | or/23‐31 | 6836573 |

| 33 | 20 not 32 | 5213356 |

| 34 | 8 and 33 | 2668 |

Embase, OvidSP

| # | Searches | Results |

| 1 | ((mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) adj3 (unit? or clinic? or center? or centre? or facility or facilities or hospital?)).ti,ab. | 3251 |

| 2 | ((mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) adj3 (service? or health* or medicine or care)).ti,ab. | 3153 |

| 3 | ((mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) adj3 (examination? or health exam* or medical exam* or diagnos* or treatment? or treating or therapy or therapies or surgery or operation? or prevent* or screen or screening or x ray or counsel* or laborator* or test or tests or testing or biopsy or biopsies or checkup? or check up? or mammogra* or ultrasound or ultra sound or vaccin* or immunisation or immunization)).ti,ab. | 2672 |

| 4 | ((mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) adj3 (health* personnel or health care personnel or medical personnel or health* professional? or health care professional? or medical professional? or health* provider? or health care provider? or medical provider? or practitioner? or doctor? or physician? or nurse or nurses or midwif* or midwiv*)).ti,ab. | 414 |

| 5 | ((medical or health* or mobile or clinic or clinical) adj (bus or buses or van or vans or car or cars or truck? or automobile? or trailer? or wagon? or wheel? or vehicle?)).ti,ab. | 320 |

| 6 | (mobile adj3 (outreach or out reach)).ti,ab. | 104 |

| 7 | or/1‐6 | 7990 |

| 8 | Randomized Controlled Trial/ | 365910 |

| 9 | Controlled Clinical Trial/ | 390179 |

| 10 | Quasi Experimental Study/ | 2330 |

| 11 | Pretest Posttest Control Group Design/ | 223 |

| 12 | Time Series Analysis/ | 15125 |

| 13 | Experimental Design/ | 10912 |

| 14 | Multicenter Study/ | 118438 |

| 15 | (randomis* or randomiz* or randomly or random allocat*).ti,ab. | 778278 |

| 16 | groups.ab. | 1805842 |

| 17 | (trial or multicentre or multicenter or multi centre or multi center).ti. | 207195 |

| 18 | (intervention? or effect? or impact? or controlled or control group? or (before adj5 after) or (pre adj5 post) or ((pretest or pre test) and (posttest or post test)) or quasiexperiment* or quasi experiment* or pseudo experiment* or pseudoexperiment* or evaluat* or time series or time point? or repeated measur*).ti,ab. | 8141994 |

| 19 | or/8‐18 | 9100534 |

| 20 | (systematic review or literature review).ti. | 70713 |

| 21 | "cochrane database of systematic reviews".jn. | 3771 |

| 22 | (exp animal/ or nonhuman/) not exp human/ | 5224879 |

| 23 | or/20‐22 | 5298709 |

| 24 | 19 not 23 | 6862461 |

| 25 | 7 and 24 | 3356 |

| 26 | limit 25 to embase | 2524 |

CINAHL, EbscoHost

| # | Query | Results |

| S24 | S23 [Exclude MEDLINE records] | 302 |

| S23 | S8 and S22 | 1,142 |

| S22 | S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 or S17 or S18 or S19 or S20 or S21 | 1,219,859 |

| S21 | TI (trial or effect* or impact* or intervention* or before N5 after or pre N5 post or ((pretest or "pre test") and (posttest or "post test")) or quasiexperiment* or quasi W0 experiment* or pseudo experiment* or pseudoexperiment* or evaluat* or "time series" or time W0 point* or repeated W0 measur*) OR AB (trial or effect* or impact* or intervention* or before N5 after or pre N5 post or ((pretest or "pre test") and (posttest or "post test")) or quasiexperiment* or quasi W0 experiment* or pseudo experiment* or pseudoexperiment* or evaluat* or "time series" or time W0 point* or repeated W0 measur*) | 701,074 |

| S20 | TI ( randomis* or randomiz* or random* W0 allocat* ) OR AB ( randomis* or randomiz* or random* W0 allocat* ) | 81,751 |

| S19 | (MH "Health Services Research") | 7,044 |

| S18 | (MH "Multicenter Studies") | 9,168 |

| S17 | (MH "Quasi‐Experimental Studies+") | 7,903 |

| S16 | (MH "Pretest‐Posttest Design+") | 24,984 |

| S15 | (MH "Experimental Studies") | 14,117 |

| S14 | (MH "Nonrandomized Trials") | 157 |

| S13 | (MH "Intervention Trials") | 5,620 |

| S12 | (MH "Clinical Trials") | 81,626 |

| S11 | (MH "Randomized Controlled Trials") | 22,389 |

| S10 | PT research | 949,864 |

| S9 | PT clinical trial | 51,995 |

| S8 | S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 | 2,494 |

| S7 | TI ( mobile N3 (outreach or out W0 reach) ) OR AB ( mobile N3 (outreach or out W0 reach) ) | 47 |

| S6 | TI ( (medical or health* or mobile or clinic or clinical) W0 (bus or buses or van or vans or car or cars or truck or trucks or automobile* or trailer* or wagon* or wheel* or vehicle*) ) OR AB ( (medical or health* or mobile or clinic or clinical) W0 (bus or buses or van or vans or car or cars or truck or trucks or automobile* or trailer* or wagon* or wheel* or vehicle*) ) | 86 |

| S5 | TI ( (mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) N3 (health* W0 personnel or health W0 care W0 personnel or medical W0 personnel or health* W0 professional* or health W0 care W0 professional* or medical W0 professional* or health* W0 provider* or health W0 care W0 provider* or medical W0 provider* or practitioner* or doctor or doctors or physician* or nurse or nurses or midwif* or midwiv*) ) OR AB ( (mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) N3 (health* W0 personnel or health W0 care W0 personnel or medical W0 personnel or health* W0 professional* or health W0 care W0 professional* or medical W0 professional* or health* W0 provider* or health W0 care W0 provider* or medical W0 provider* or practitioner* or doctor or doctors or physician* or nurse or nurses or midwif* or midwiv*) ) | 212 |

| S4 | TI ( (mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) N3 (examination* or health W0 exam* or medical W0 exam* or diagnos* or treatment* or treating or therapy or therapies or surgery or operation* or prevent* or screen or screening or "x ray" or counsel* or laborator* or test or tests or testing or biopsy or biopsies or checkup* or check W0 up? or mammogra* or ultrasound or ultra W0 sound or vaccin* or immunisation or immunization) ) OR AB ( (mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) N3 (examination* or health W0 exam* or medical W0 exam* or diagnos* or treatment* or treating or therapy or therapies or surgery or operation* or prevent* or screen or screening or "x ray" or counsel* or laborator* or test or tests or testing or biopsy or biopsies or checkup* or check W0 up? or mammogra* or ultrasound or ultra W0 sound or vaccin* or immunisation or immunization) ) | 443 |

| S3 | TI ( (mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) N3 (service or services or health* or medicine or care) ) OR AB ( (mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) N3 (service or services or health* or medicine or care) ) | 917 |

| S2 | TI ( (mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) N3 (unit or units or clinic or clinics or center or centers or centre or centres or facility or facilities or hospital or hospitals) ) OR AB ( (mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) N3 (unit or units or clinic or clinics or center or centers or centre or centres or facility or facilities or hospital or hospitals) ) | 569 |

| S1 | (MH "Mobile Health Units") | 1,116 |

Global Health, OvidSP

| # | Searches | Results |

| 1 | ((mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) adj3 (unit? or clinic? or center? or centre? or facility or facilities or hospital?)).mp. | 553 |

| 2 | ((mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) adj3 (service? or health* or medicine or care)).mp. | 558 |

| 3 | ((mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) adj3 (examination? or health exam* or medical exam* or diagnos* or treatment? or treating or therapy or therapies or surgery or operation? or prevent* or screen or screening or x ray or counsel* or laborator* or test or tests or testing or biopsy or biopsies or checkup? or check up? or mammogra* or ultrasound or ultra sound or vaccin* or immunisation or immunization)).mp. | 496 |

| 4 | ((mobile or movable or moveable or traveling or travelling) adj3 (health* personnel or health care personnel or medical personnel or health* professional? or health care professional? or medical professional? or health* provider? or health care provider? or medical provider? or practitioner? or doctor? or physician? or nurse or nurses or midwif* or midwiv*)).mp. | 34 |

| 5 | ((medical or health* or mobile or clinic or clinical) adj (bus or buses or van or vans or car or cars or truck? or automobile? or trailer? or wagon? or wheel? or vehicle?)).mp. | 59 |

| 6 | (mobile adj3 (outreach or out reach)).mp. | 34 |

| 7 | or/1‐6 | 1343 |

| 8 | (randomis* or randomiz* or randomly allocat* or random allocat* or groups or trial or multicenter or multi center or multicentre or multi centre or intervention? or effect? or impact? or controlled or control group? or (before adj5 after) or (pre adj5 post) or ((pretest or pre test) and (posttest or post test)) or quasiexperiment* or quasi experiment* or pseudo experiment* or pseudoexperiment* or evaluat* or time series or time point? or repeated measur*).mp. | 1175972 |

| 9 | 7 and 8 | 755 |

POPLINE, K4Health

Two individual strategies.

1. Title: mobile AND Title: unit OR units OR clinic OR clinics OR mammography OR screening

2. All Fields: "mobile clinic" OR "mobile clinics" OR "mobile hospital" OR "mobile hospitals" OR "mobile health" OR "mobile healthcare" AND All Fields: randomised OR randomized OR "randomly allocated" OR "random allocation" OR "controlled trial" OR "control group" OR "control groups" OR quasiexperiment* OR "quasi experiment" OR "quasi experiments" OR "quasi experimental" OR "pseudo experiment" OR "pseudo experiments" OR "pseudo experimental" OR pseudoexperiment OR pseudoexperiments OR pseudoexperimental OR evaluat* OR "time series" OR "time point" OR "time points" OR "repeated measure" OR "repeated measures" OR "repeated measurement" OR "repeated measurements" OR "before and after" OR "pre and post" OR (("pretest" OR "pre test") AND ("posttest" OR "post test")) OR effect OR effects OR impact OR impacts OR intervention OR interventions OR trial OR multicenter OR "multi center" OR multicentre OR "multi centre"

Science Citation Index and Social Sciences Citation Index, ISI Web of Science

TOPIC: mobile NEAR/3 (clinic or clinics or hospital or hospitals or unit or units or mammography) AND TOPIC: woman* or women* or mother* or maternal* or child* AND TOPIC: randomised OR randomized or "randomly allocated" or "random allocation" or "controlled trial" or "control group" or "control groups" or quasiexperiment* or "quasi experiment" or "quasi experiments" or "quasi experimental" or pseudoexperiment* or "pseudo experiment" or "pseudo experiments" or "pseudo experimental" or evaluat* or "time series" or "time point" or "time points" or "repeated measure" or "repeated measures" or "repeated measurement" or "repeated measurements" or "before and after" or "pre and post" or (("pretest" or "pre test") AND ("posttest" or "post test")) or effect or effects or impact or impacts or intervention or interventions or trial or multicenter or "multi center" or multicentre or "multi centre"

Global Health Library, WHO

(Regional Indexes: AIM (AFRO), IMEMR (EMRO), IMSEAR (SEARO), WPRIM (WPRO), LILACS)

Searched in: Title