Abstract

Vibrio cholerae is the causal organism of the diarrheal disease cholera. The rugose variant of V. cholerae is associated with the secretion of an exopolysaccharide. The rugose polysaccharide has been shown to confer increased resistance to a variety of agents, such as chlorine, bioacids, and oxidative and osmotic stresses. It also promotes biofilm formation, thereby increasing the survival of the bacteria in the aquatic environments. Here we show that the extracellular protein secretion system (gene designated eps) is involved directly or indirectly in the production of rugose polysaccharide. A TnphoA insertion in epsD gene of the eps operon abolished the production of rugose polysaccharide, reduced the secretion of cholera toxin and hemolysin, and resulted in a nonmotile phenotype. We have constructed defined mutations of the epsD and epsE genes that affected these phenotypes and complemented these defects by plasmid clones of the respective wild-type genes. These results suggest a major role for the eps system in pathogenesis and environmental survival of V. cholerae.

Vibrio cholerae is a gram-negative bacterium that causes the diarrheal disease cholera, which continues to be a global threat. Seven pandemics have been recorded in the history of cholera, and a novel epidemic strain, O139 Bengal, has emerged recently (15). In countries where cholera is endemic, such as Bangladesh and India, cholera occurs in seasonal peaks intermittent with an endemicity baseline (8). The survival of V. cholerae during interepidemic periods has long been a key question. It has been proposed that V. cholerae can enter into a nonculturable state but remain viable and capable of producing disease (35, 42). It has also been shown that V. cholerae cells remain associated with plankton, which may be reservoirs of this bacterium (13).

V. cholerae can switch to another survival form, known as the rugose phenotype, while retaining virulence (28, 34, 49). The rugose phenotype, as originally described by Bruce White in 1938, is characterized by wrinkled colony morphology associated with the secretion of copious amounts of extracellular polysaccharide (49, 50). Under normal growth conditions, the shift from smooth to rugose or vice versa occurs at a low frequency that can be increased by growth in alkaline peptone water for 2 to 3 days at 37°C (28) or by starvation in M9 salts at 16°C (45, 46). V. cholerae serogroup O1 El Tor, serogroup O139, and non-O1 strains have been shown to switch to the rugose phenotype, although O1 classical strains have not (28, 52).

The rugose form of V. cholerae exhibits increased resistance to chlorine, acid, serum killing, and oxidative and osmotic shocks (28, 34, 45, E. W. Rice, C. J. Johnson, R. M. Clark, K. R. Fox, O. J. Reasoner, M. E. Dunnigan, P. Panigraphi, J. A. Johnson, and J. G. Morris, Jr., Letter, Lancet 340:740, 1992). The increased resistance is probably due to aggregation of cells in the polysaccharide matrix 28, 34; Rice et al., Lancet 340:740, 1992). Consistent with this idea, rugose polysaccharide has been shown to promote biofilm formation that might result in an increased survival of V. cholerae in aquatic environments, although the presence of rugose V. cholerae in aquatic environments has not yet been confirmed (52). The genetic basis of rugosity and its role in biofilm formation are just beginning to be unraveled. Recently, a genetic region (vps, for vibrio polysaccharide synthesis) involved in the synthesis of rugose polysaccharide, termed EPSETr, has been identified. Mutations in this region abolished the formation of rugose material, and addition of purified rugose polysaccharide to the mutant bacteria conferred resistance to chlorine (52). A search for the genes responsible for biofilm formation has identified three groups of genes involved in (i) biosynthesis and secretion of mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin type IV pilis (MSHA), (ii) vibrio polysaccharide synthesis (vps genes), and (iii) flagellar motility (47, 48).

Epidemic cholera is caused by V. cholerae strains of serogroup O1 or O139 that secrete cholera toxin (CT) (15). CT secretion requires a general secretory pathway (GSP) encoded by the eps (extracellular protein secretion) operon, comprising 12 genes, epsC to -N. This pathway is also essential for the secretion of chitinase and protease (30, 38–40).

A diverse group of gram-negative bacteria utilize GSP homologs to secrete either soluble proteins such as cellulase, pectinase, protease, pullulanase, and chitinase (9, 19, 21, 32, 33, 40) or cell surface-associated appendages such as type IV pili (25) and S-layers (44). GSP systems are divided into two branches. Transport of specific signal-associated proteins across the inner membrane involves Sec proteins, while assembly and transport of proteins across the outer membrane require a terminal branch (32). GSP terminal branches, like eps, consist of 12 to 14 genes and are present in both animal and plant pathogens (37). Escherichia coli filamentous bacteriophages such as M13, fd, and f1 carry some of these GSP gene homologs, which are involved in the secretion of matured phage particles (36). GSP proteins are highly specific in secretory functions and cannot be substituted for each other despite a high degree of similarity among the proteins of different bacterial origins (32, 37). While the majority of these proteins are localized in the cytoplasmic membrane, GspD is an integral outer membrane protein (9). It has been suggested that GspD is a multimeric complex of 12 monomers that forms a large pore allowing transport of macromolecules such as S-layers, pili, mature filamentous phages, and extracellular proteins such as pectinase, hydrolase, CT, chitinase, and protease (9, 37). We report here the involvement of the V. cholerae eps operon in the production of rugose polysaccharide and motility as well as secretion of hemolysin and CT. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the involvement of a type II secretion system in polysaccharide production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1, and the oligonucleotide primers are listed in Table 2. Media and growth conditions were as previously described (28).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| V. cholerae strains | ||

| C6706 | Wild type, smooth, serogroup O1 El Tor biotype | 34 |

| C6706 R | C6706 rugose variant | This study |

| 569B | Wild type, smooth, serogroup O1 Classical biotype | 12 |

| N16961 | Wild type, smooth, serogroup O1 El Tor biotype | 28 |

| N16961 R | N16961 rugose variant | This study |

| NS1 | Derivative of N16961 R, smooth, epsD::TnphoA, KanR | This study |

| AA10 | N16961 R, epsD::Kanr cassette | This study |

| AA1 | N16961 R, epsE::Kanr cassette | This study |

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | recA ΔlacU169 φ80d lacZΔM15 | Gibco BRL |

| S17-1 λ pir | pro hsdR hsdM+ Tmpr Strr | 7, 27 |

| SM10 λ pir | thi thr leu tonA lacY supE recA::RP4-2Tc::Mu Kanr | 7 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript | High-copy-number vector, Ampr, ori ColE1 | Stratagene |

| pCVD442 | Suicide vector, ori R6K, Ampr, sacB | 7 |

| pHC79 | Low-copy-number cosmid vector, Ampr, ori R6K | 11 |

| pRT733 | TnphoA delivery vector, oriR6K, mob RP4, Kanr Ampr | 43 |

| pUC18 K | High-copy-number vector, Ampr, ori ColE1, Kanr cassette mutagenesis vector | 26 |

| pUC18 K2 | High-copy-number vector, Ampr, ori ColE1, Kanr cassette mutagenesis vector | J. B. Kaper |

| pAA5 | pHC79 containing a 38-kb Sau3 AI fragment of NS1, Ampr Kanr | This study |

| pAA13 | pBluescript SK containing a 4.3-kb TnphoA insertion junction sequence from pAA5, Ampr | This study |

| pDSK-2 | pBluescript KS containing a 2.4-kb EcoRI-BamHI PCR fragment (epsD) from V. cholerae 569B | This study |

| pAA26 | pBluescript SK containing a 2.4-kb BamHI-EcoRI PCR fragment (′epsD-5′-epsE′) from the N16961 rugose strain | This study |

| pAA29 | pAA26::Kanr, a 0.8-kb Kanr cassette from pUC18K inserted into the unique NheI site at the 3′ end of epsD | This study |

| pAA35 | pCVD442 containing a 3.2-kb BamHI-EcoRI fragment from pAA29 | This study |

| pAA40 | pBluescript SK containing 2.3-kb BamHI-KpnI PCR fragment (′epsD-epsE-epsF′) | This study |

| pAA42 | pAA40 containing Tetr cassette (EcoRI-AvaI fragment of pBR322) cloned in the XmnI site | This study |

| pAA46 | pAA42ΔepsE::Kanr, deletion of a HincII (bp 4117–4263) fragment and insertion of a 0.8-kb Kanr cassette from pUC18K2 into that site | This study |

| pAA48 | pCVD442 containing 3.1-kb BamHI-EcoRI fragment of pAA46 cloned into the SalI site | This study |

TABLE 2.

Sequences of the oligonucleotide primers

| Primer | Location | Nucleotide sequence | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| J-238 | IS50R | 5′-GAAAGGTTCCGTTCAGGA-3′ | U25548>U25548 |

| M-157 | epsE | 5′-CGGAATTCCATATCGCGCAGCCGAGTCAC-3′ | L33796 |

| M-158 | epsD | 5′-CGGGATCCGATTTCTGGCGATCCTAAAGTG-3′ | L33796 |

| M-202 | epsD | 5′-CGGGATCCGTAAATACAACTACATCCGC-3′ | L33796 |

| M-203 | epsF | 5′-GGGGTACCCAGCGCACCAGATAAATCAG-3′ | L33796 |

| M-229 | epsD | 5′-GCAAGAAGTCTCGAACGTG-3′ | L33796 |

| M-230 | epsE | 5′-CGAGCGCCTCCATCGACAAC-3′ | L33796 |

| M-231 | IS50L | 5′-AGCCCGGTTTTCCAGAAC-3′ | U25548 |

| M-355 | epsE | 5′-CTCTTTGTCCGCCTCGTA-3′ | L33796 |

| M-357 | epsE | 5′-GATCTGCACAGTTTGGGTATG-3′ | L33796 |

| TD001 | epsC | 5′-GAAATCCGCAGGAAATTT-3′ | L33796 |

| TD002 | epsE | 5′-AGAGATCACCATTTCGG-3′ | L33796 |

Isolation of TnphoA mutants.

TnphoA, on suicide vector pRT733 (43), was introduced by conjugation into rugose isolates of strains C6706 and N16961. Transconjugants were plated on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar containing kanamycin and polymyxin B to select for cells that acquired the TnphoA and were screened for smooth colonies. These colonies were grown in alkaline peptone water (31) to check whether the shift from the rugose to smooth phenotype is not due to phase variation but is due to the inactivation of a gene essential for the rugose phenotype.

Mapping of the TnphoA insertions.

To determine the number and locations of the insertions in each mutant, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (4) of SfiI-digested chromosomal DNAs of wild-type and mutant strains was carried out on a CHEF-DRII mapper (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The DNA was transferred onto nylon membrane (MSI, Westboro, Mass.) by capillary transfer and hybridized with a 32P-labeled 2.6-kb BglII TnphoA fragment under stringent conditions (22). Since SfiI does not cut within TnphoA, each hybridized band corresponded to a single insertion.

Cosmid cloning.

Cloning and recombinant DNA techniques were carried out as previously described (22). Chromosomal DNA of NS1 was partially digested with Sau3A1, and fragments in the range of 30 to 35 kb were purified. These fragments were ligated into the BamHI site of cosmid pHC79 (11), packaged using Gigapack (Stratagene, Inc., La Jolla, Calif.), and transduced into E. coli DH5α, and the transductants were selected on LB plates containing 50 μg of kanamycin per ml.

Cloning of the epsD gene.

Two convergent PCR primers (TD001 and TD002 [Table 2]) based on the published nucleotide sequence of the eps operon (from bp 850 to 3217) were used to amplify the epsD gene from V. cholerae 569B (40). The resulting 2.4-kb amplicon was gel purified, digested with BamHI, and partially digested with EcoRI, as epsD has an internal EcoRI site, before ligation into EcoRI-BamHI-digested pBluescript vector. The ligated DNA was transformed into E. coli DH5αF′tet, and transformants were selected on LB plates containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml. One of the transformants, designated pDSK-2, was shown to contain the epsD gene by restriction enzyme analysis.

Construction of in-frame insertion mutants.

The epsD gene was PCR amplified using primers M-157 and M-158 and cloned into pBluescript, resulting in pAA26. A Kanr cassette from pUC18K was inserted into the NheI site of epsD (pAA29). The entire insert was transferred into a suicide vector, pCVD442 (pAA35), that contains a sucrose selection system. Transfer of the epsD knockout into the V. cholerae chromosome was done by conjugation and selection for ampicillin resistance. Derivatives with chromosomal integration of the Kanr cassette were selected on 5% sucrose plates (7). Further analysis of the sucrose-resistant colonies (Kanr Amps) by PCR and DNA sequencing was carried out in order to verify the chromosomal knockout of the epsD gene. The epsE gene was cloned similarly in pBluescript using primers M-202 and M-203 (pAA40). A Kanr cassette from pUC18 K2 was inserted into the gene at the HincII sites (pAA46), and in the next step the epsE gene with the Kanr cassette was transferred into pCVD442 (pAA48). The knockout was introduced into the chromosome as described above.

Other techniques.

CT assay was done by GM1 ganglioside enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (5). Hemolysin activity was measured by streaking out the test strains on 5% rabbit blood agar plates and incubating the plates at 37°C overnight. Motility assays were carried out by inoculation of the test strains on motility agar plates containing 0.3% agar followed by incubation at 37°C for 4 to 5 h, at the end of which time the zone of motility was measured (17). DNA sequencing was done with an ABI automated sequencer at the University of Maryland Biopolymer Laboratory. DNA sequence analyses were performed using the DNASIS program (Hitachi Software Corp.), and sequence homology searching was performed using the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST program (1).

RESULTS

Isolation of TnphoA mutants with an altered rugose phenotype.

To identify the genetic regions involved in rugosity, we isolated mutants following TnphoA mutagenesis. TnphoA (23), on suicide vector pRT733 (43), was introduced by conjugation into rugose variants of V. cholerae O1 El Tor strains C6706 and N16961. Kanr and polymyxin B-resistant exconjugants were screened for smooth colonies. Smooth colonies were tested in alkaline peptone water and were found to remain smooth, indicating the linkage of TnphoA to the smooth phenotype.

The locations of TnphoA insertions in each mutant were mapped by PFGE analysis. Seven of the 16 stable smooth mutants analyzed had multiple TnphoA insertions (Table 3). The remaining nine mutants had single insertions in a total of five unique fragments (145.5, 165, 291, 435, and 677 kb), indicating the possible association of these fragments with the rugose phenotype. The 291-kb fragment had an insertion in the majority (ten) of the mutants. Of these, four mutants (S7, S17, S20, and NS1) had a single insertion. Therefore, strain NS1 with a TnphoA insertion in the 291-kb fragment was selected for further analysis.

TABLE 3.

Secretion phenotypes of wild-type and mutant V. cholerae O1 El Tor rugose strains

| Straina | Antibiotic resistanceb | No. of TnphoA insertions | Map location of TnphoA insertion(s) (kb of SfiI fragment)c | Hemolysisd | Motilitye | CT activity (% of total) in:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium | Cells | ||||||

| S1 | Kanr Ampr | 1 | 677 | +++ | +++ | 99 | 1 |

| S2 | Kanr Ampr | 1 | 145.5 | +++ | ++ | 99 | 1 |

| S3 | Kanr Ampr | 2 | 291, 339 | + | + | 80 | 20 |

| S4 | Kanr Ampr | 2 | 291, 339, 388 | − | − | 66 | 34 |

| S7 | Kanr Ampr | 1 | 291 | +++ | +++ | 99 | 1 |

| S8 | Kanr Ampr | 1 | 677 | +++ | +++ | 99 | 1 |

| S10 | Kanr Ampr | 1 | 165 | +++ | + | 99 | 1 |

| S11 | Kanr Ampr | 2 | 291, 490 | +++ | +++ | 70 | 30 |

| S13 | Kanr Ampr | 2 | 291, 490 | +++ | ++ | 99 | 1 |

| S14 | Kanr Ampr | 3 | 291, 490, 525 | ++ | +++ | 99 | 1 |

| S16 | Kanr Ampr | 2 | 291, 280 | +++ | +++ | 53 | 47 |

| S17 | Kanr Ampr | 1 | 291 | +++ | +++ | 86 | 14 |

| S18 | Kanr Ampr | 2 | 80, 425 | +++ | +++ | 75 | 25 |

| S20 | Kanr Ampr | 1 | 291 | +++ | +++ | 99 | 1 |

| NS1 | Kanr Ampr | 1 | 291 | − | − | 28 | 72 |

| NS25 | Kanr Ampr | 1 | 435 | +++ | +++ | NDf | ND |

| N16961 R | Kanr Ampr | None | +++ | +++ | 99 | 1 | |

| AA16 | Kanr Ampr | None | +++ | +++ | 98 | 2 | |

| AA10 | Kanr | None | − | + | 36 | 64 | |

| AA10/pDSK-2 | Kanr Ampr | None | + | +++ | 99 | 1 | |

| AA1 | Kanr | None | − | − | 87 | 13 | |

| AA1/pAA44 | Kanr Ampr | None | + | ++ | 99 | 1 | |

Strains S1 to S20 were derived from C6706 rugose; NS1 and NS25 were derived from N16961 rugose

Ampr is probably due to cointegration of the transposon delivery vector

In PFGE analysis

Hemolytic activity on 5% rabbit blood agar plates after 24 h of incubation at 37°C. +++, ++, +, and −, complete, moderate, weak, and no lysis, respectively.

Motility determined after 4 to 6 h of incubation at 37°C on motility agar. +++, ++, +, and −, high, moderate, weak, and nonmotile phenotypes, respectively.

ND, not determined.

Subcloning, mapping, and sequencing of NS1 TnphoA insertion junctions.

The TnphoA-containing fragment was cloned in a cosmid vector as described in Materials and Methods. One Kanr transductant, designated pAA5, was characterized further. To map the TnphoA insertion junctions in pAA5, cosmid DNA was purified, digested with EcoRI or SalI, and hybridized with a 2.6-kb BglII TnphoA probe. EcoRI cuts upstream of the kan gene in TnphoA, and the fragment that hybridizes to the probe is the 3′ TnphoA-Vibrio junction fragment. SalI cuts downstream of kan gene in TnphoA, and the two fragments that hybridize are the 5′ and 3′ TnphoA-Vibrio junction fragments. As expected, this probe hybridized with a single EcoRI fragment, identifying the 3′ TnphoA insertion junction, and with two SalI fragments, identifying both the 5′ and 3′ TnphoA insertion junctions (data not shown).

The 4.3-kb SalI fragment from pAA5 containing the 3′ TnphoA-Vibrio insertion junction was cloned into the SalI site of pBluescript SK(+) to yield pAA13. The cloned fragment was sequenced using primer J-238 (Table 2), derived from the 3′ end of TnphoA. A DNA sequence homology search revealed that the TnphoA was inserted 148 bp upstream of the stop codon of epsD, the second gene in the eps operon (Fig. 1). We verified the integrity of the epsD sequence at the 5′ TnphoA-Vibrio junction, since a deletion or other rearrangements at this end could also result in the mutant phenotype. To rule out this possibility, we PCR amplified the 5′ TnphoA-Vibrio junction sequence from NS1 chromosomal DNA using two convergent primers, M-158 and M-231 (Table 2). The resulting 1.2-kb PCR product was sequenced using a TnphoA reverse primer, M-231, and an epsD primer, M-229 (Table 2). The DNA sequence data did not reveal any evidence of a deletion or other rearrangement at the 5′ TnphoA junction except for a 9-bp direct repeat at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the TnphoA insertion site. Tn5 is known to create a 9-bp target duplication (3). These results indicated that the TnphoA insertion at the 3′ end of epsD gene (corresponding to 49 amino acid residues from the carboxyl-terminal end of the EpsD protein) was responsible for the reversion of the rugose to the smooth phenotype in the NS1 mutant.

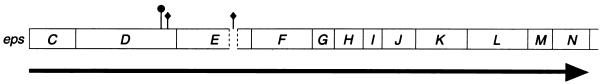

FIG. 1.

The eps operon of V. cholerae. The eps cluster contains the genes epsC to epsN, and the entire region is 12,077 bp in length. The transcriptional orientation of the eps cluster is indicated by the arrow below the genes. The site of the TnphoA insertion in epsD is indicated by a filled circle, and those of the in-frame Kanr cassettes are indicated by the filled diamonds. A 146-bp deletion in the epsE gene at the site of Kanr insertion is indicated by the broken box.

Complementation of the epsD::TnphoA mutant by a cloned epsD+ gene.

Although the TnphoA insertion in the NS1 mutant resulted in the loss of the rugose phenotype, we could not conclude whether the phenotypic change was due exclusively to inactivation of epsD or was caused by a polar effect on the genes downstream of epsD within the eps operon. We therefore attempted to complement the epsD mutation in NS1. A plasmid carrying epsD+, pDSK-2, was electroporated into NS1, and ampicillin-resistant transformants were observed for colony morphology. No rugose colonies were seen on initial isolation, but on passage in LB medium without the antibiotic, rugose colonies were recovered at a high frequency (20 to 50%). All the rugose revertants had lost the Kanr marker. One such rugose strain, AA16, selected for further study, exhibited sensitivity to both kanamycin and ampicillin, and furthermore, plasmid DNA could not be detected (data not shown). These results suggested the loss of both the TnphoA insertion and pDSK-2 from AA16 and reversion to the wild-type rugose phenotype. This probably happened by allelic exchange between the chromosomal epsD::TnphoA and the pDSK-2 (eps+). The loss of TnphoA and restoration of the wild-type epsD sequence in AA16 were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. DNA sequences flanking the TnphoA insertion site were amplified using primers M-157 and M-158 (Table 2), purified, and sequenced using primers M-229 and M-230. Sequence analysis showed that AA16 contained the epsD+ allele, indicating the loss of TnphoA along with the 9-bp direct repeat. In our hands, under identical conditions the reversion of rugose to smooth or vice versa or with NS1 containing a control plasmid (pBluescript) lacking epsD occurs at a very low frequency (ca. 10−4). These results indicated that the reversion in AA16 is not due to TnphoA excision but is attributable to homologous recombination.

In-frame insertion mutations in epsD and epsE genes affect rugose polysaccharide production.

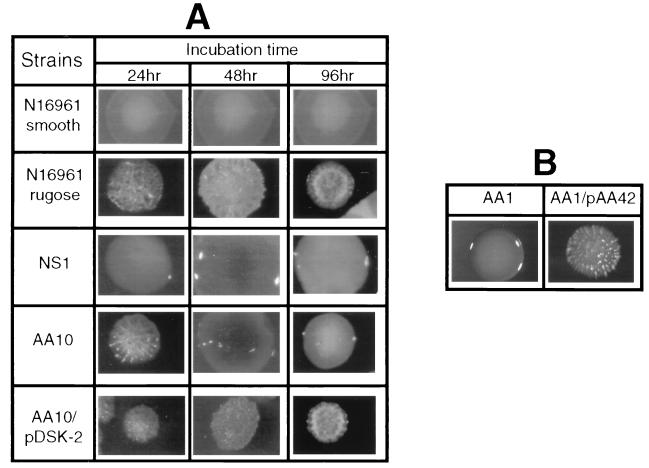

In order to eliminate the possibility of a polar effect and to examine whether genes other than epsD in the eps operon are involved in the rugose phenotype, we constructed an in-frame insertion of a Kanr cassette in epsD. The resulting mutant, AA10, exhibited a time-dependent defect in the expression of rugose polysaccharide; i.e., the mutant remained rugose for 24 h but turned smooth on prolonged incubation (Fig. 2A). Unlike NS1, this mutant could be complemented by pDSK-2; i.e., AA10 containing pDSK-2 was rugose (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

(A) Smooth and rugose colony morphologies of the wild-type and mutant strains. The various strains were grown to different times, as indicated, in LB agar plates with or without the respective antibiotics. (B) Strain AA1 (epsE::Kanr) and the complemented strain (epsE::Kanr/pAA42) after overnight growth.

NS1 exhibited a severe defect in rugose polysaccharide production (i.e., smooth even after several days of growth) compared to AA10. We interpret this to mean that in NS1 the TnphoA insertion had polar effects on the expression of genes downstream of epsD in the eps operon in addition to a partially defective epsD gene. In order to test this hypothesis, we introduced an in-frame insertion in the epsE gene. A 146-bp deletion of epsE was created and a Kanr cassette was inserted in-frame at this position, resulting in the strain AA1. This mutation abolished the production of rugose polysaccharide, indicating that epsE also is involved in rugose polysaccharide synthesis or secretion. A plasmid carrying an epsE+ allele complemented this mutant, restoring rugosity (Fig. 2B).

Other phenotypes affected in eps mutants.

Sandkvist et al. have found that mutations in six of the 12 genes of the eps operon (epsC, -E, -F, -G, -L, and -M) resulted in defects in secretion of CT, protease, and chitinase (38–40). They also noted that the rest of the genes of this operon might be required for extracellular secretion. We were interested in determining whether epsD and epsE mutants are defective in secretion of CT, hemolysin, and extracellular structures such as flagella. In addition to its defect in rugose expression (Fig. 2), NS1 exhibited a severe defect in secretion of CT and hemolysin as well as in motility (Table 3 and Fig. 3). Reversion of epsD::TnphoA in NS1 to the wild type (AA16) restored secretion of CT and hemolysin, motility, and rugosity to wild-type levels (Table 3). Similarly, AA10 (epsD::Kanr) and AA1 (epsE::Kanr) exhibited defects in these phenotypes, although AA1 showed a less severe defect in CT secretion. These defects could be complemented by plasmid clones of the respective wild-type genes (Table 3). The nonmotile phenotype of these mutants is not an indirect effect due to growth defects. The mutants NS1 and AA10 do not show any significant growth defect compared to the wild-type strain, N16961 R (generation time, 35 to 40 min). Although AA1 (epsE::Kanr) grows more slowly than N16961 R, there was no evidence of motility even after prolonged incubation (24 h) on motility agar plates. These results indicated that the epsD and epsE genes are involved in rugose polysaccharide production and formation of the polar flagella in addition to secretion of CT and hemolysin.

FIG. 3.

Swarming behavior of wild-type and mutant V. cholerae strains on motility agar plates. 1, N16961 R (wild type); 2, NS1 (epsD::TnphoA); 3, AA10 (epsD::Kanr); 4, AA10/pDSK-2 (epsD+); 5, AA1 (epsE::Kanr); 6, AA1/pAA42 Tetr (epsE+)

DISCUSSION

We were interested to decipher the genetic basis of rugosity. We hypothesized that there are separate genetic regions responsible for the synthesis, control, phase variation, and secretion to the extracellular milieu of the rugose polysaccharide. Indeed, the mutations in the TnphoA mutants isolated in this study mapped to five distinct SfiI fragments, suggesting that there may be five different regions involved in rugosity. Recently, Yildiz and Schoolnik (52) identified one of the regions (vps) involved in the synthesis of rugose polysaccharide. Here we report a second region (eps) involved in the synthesis or secretion of the polysaccharide. Identification of the other regions is in progress. Most of the TnphoA mutants isolated in this study had multiple insertions, and many had the suicide delivery vector cointegrated at the insertion site. This phenomenon has been previously observed, and it is one of the drawbacks of this transposon delivery vector (43).

The data presented here demonstrate that a 291-kb SfiI fragment involved, directly or indirectly, in the production of rugose polysaccharide contains the eps operon. Interestingly, the recently described rugose polysaccharide biosynthesis region, vps, contains an (exopolysaccharide (EPS) transport-associated gene (exoP) (52). The role of this gene needs to be determined in light of our finding that the eps operon may be involved in the secretion of rugose polysaccharide. Perhaps the two systems are involved in the transport and secretion of rugose polysaccharide to different cellular compartments. For example, exoP may be involved in transport of the polysaccharide from the cytoplasm across the inner membrane, analogous to the Sec-dependent transport of proteins. The eps pathway may be involved in the subsequent transport across the outer membrane and secretion into the external medium.

The TnphoA insertion at the 3′ end of epsD in the N16961 rugose strain resulted in stable smooth colonies. Although EpsD has been predicted to be the channel-forming outer membrane protein of the GSP system, this report presents the first experimental evidence for the involvement of this protein in CT secretion as well as other secretion phenotypes in V. cholerae. Introduction of a wild-type epsD+ gene on a multicopy plasmid (pDSK-2) resulted in a high-frequency allelic exchange with the chromosomal epsD::TnphoA copy. The failure of complementation in trans may be due to overexpression of epsD from pDSK-2 compared to the genes downstream of epsD, which are probably underexpressed because of polarity of the chromosomal epsD::TnphoA insertion. The resulting alteration in the stoichiometry of the EPS proteins is probably detrimental to the cell, leading to reciprocal recombination that eliminated the epsD+ plasmid. This is consistent with the findings of Sandkvist et al. that EpsL and EpsM interact with each other (39, 41), and EpsD probably interacts with one or more of the EPS proteins in a stoichiometric fashion in the multiprotein secretion apparatus. Additional support for this argument is based on the construction of an in-frame insertion mutant of epsD (AA10) that could be complemented by pDSK-2. AA10 exhibits a delayed smooth phenotype. The colonies, after overnight growth, show rugose morphology, but they turn smooth on continued incubation. We speculate that this is due to a partial defect in secretion of rugose polysaccharide and that the synthesis of rugose polysaccharide is probably shut down when secretion is partially blocked. AA10 could be complemented by pDSK-2, and this indicated that the failure of complementation in NS1 is not due to lack of expression of epsD on pDSK-2.

Previously the eps system was shown to mediate the secretion of CT, chitinase, and protease (38–40). The data presented here indicate its involvement in the secretion of additional substrates, including hemolysin and complex structures such as rugose polysaccharide and flagella. However, not all the TnphoA mutants (rugose to smooth) are defective in secretion of CT and hemolysin. The mutants with multiple TnphoA insertions need to be separated to understand which of the insertions causes the defects. Even in isolates with a single TnphoA insertion there is not a strict correlation of the phenotypes. For example, S7, S17, S20, and NS1 all have a TnphoA in a 291-kb SfiI fragment. However, only NS1 exhibits all the secretory defects. The majority of the mutants that show defects in CT secretion (S3, S4, S11, S16, S17, and NS1) have at least one insertion in the 291-kb fragment. CT secretion is severely attenuated in epsD mutants NS1 and AA10. For reasons not well understood, in AA1 (epsE::Kanr), CT secretion is less severely affected.

The mutants S3, S4, and NS1 showed complete loss of hemolytic activity. E. coli hemolysin is secreted via the type I secretory pathway (32). In V. cholerae serogroup O1, biotype El Tor, hemolysin is secreted extracellularly as prohemolysin and requires cleavage by a secreted protease to become biologically active (29, 51). Hence, the epsD::TnphoA mutation in NS1, and presumably that in S4 as well, may be directly inhibiting the secretion of hemolysin or indirectly inhibiting hemolysis by affecting protease secretion.

The loss of motility in some mutants (S2, S3, S4, S10, and NS1) suggests a role for eps system in flagellar biosynthesis. The defects in motility of the epsD and epsE mutants are not due to growth defects. Preliminary electron microscopic analyses indicate that NS1 and AA1 lack a polar flagellum (A. Ali and S. Sozhamannan, unpublished data). It is interesting that unlike other systems where flagellar biogenesis involves dedicated pathways, in V. cholerae the GSP may play a direct or indirect role.

We are currently examining whether the eps mutants affect the formation of other extracellular structures such as toxin-coregulated pili (TCP) or mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin type IV pili as well. This is particularly relevant because some GSP homolog proteins are involved in assembly and maturation of filamentous phages (fd, f1 and M13) (36); the TCP pilus has been suggested to be the major coat protein of a single-stranded phage, VPI φ (16). It would be of interest to see if the epsD and epsE mutants are defective for the secretion of single-stranded phages of V. cholerae such as CTX φ and VPI φ.

It is surprising that the eps system, involved in transporting proteins across the outer membrane, can also affect polysaccharide secretion. It may be that the rugose polysaccharide is coated with proteins during translocation. Alternatively, the eps system may affect polysaccharide synthesis or processing rather than secretion. Our future studies will be aimed at distinguishing these possibilities.

It is conceivable that eps mutants affect the production of rugose polysaccharide indirectly by affecting the secretion of an outer membrane protein that positively regulates polysaccharide synthesis. The positive regulation may be through a two-component sensor-transducer regulatory cascade that relays an environmental signal. It has been shown that the eps mutants have a modified cell envelope due to defects in the production of certain outer membrane proteins (24, 40). This membrane perturbation might affect the signaling pathway that regulates the transcription of polysaccharide biosynthesis genes. In other species polysaccharide production and biofilm formation are regulated at the transcriptional level by LuxR and LuxI homologs (2, 6, 10, 20). Indeed, a LuxR homolog, HapR, has been identified recently in V. cholerae as a positive regulator of hemagglutinin and protease gene expression. Interestingly, HapR seems to negatively regulate rugose polysaccharide formation (14). Although the mechanism of this regulation is not known, it might involve quorum sensing. It may be that HapR itself is an outer membrane protein that requires a functional eps system for proper membrane localization. In this case, eps mutants would be derepressed for rugose expression. Although in a serogroup O139 smooth strain background, an epsD mutant is not phenotypically HapR− with respect to rugose expression (A. Ali and S. Sozhamannan, unpublished observation), there may be other strain-specific differences in this regulatory network.

Similar indirect effects of the mutations in eps genes on flagellar biogenesis may result in nonmotile mutants. Regulatory genes, such as rpoN (encoding ς54) and the cognate transcriptional activators (flrA to -C) of flagellar biosynthesis have been identified (18), and it is possible that their ability to regulate flagellar gene transcription might also depend on a functional eps system. Our future studies will focus on elucidating the mechanism(s) by which the eps pathway affects phenotypes such as flagellar biogenesis and polysaccharide production. The significant finding of this work, however, is that the V. cholerae GSP system, eps, seems to affect directly or indirectly multiple aspects of V. cholerae pathogenesis and environmental survival.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nick Ambulos and Lisa Sadzewicz (University of Maryland Biopolymer Laboratory) for DNA sequencing and Richard Milanich for help with preparing the figures. We thank Rick Blank for comments on the manuscript. Our thanks are also due to the anonymous reviewer for the many useful suggestions to improve the manuscript.

This work was supported by a VA/DOD grant on emerging infectious diseases to J.G.M., a Department of Veterans Affairs grant to J.A.J., Public Health Service grant AI 35729 to J.A.J., and a University of Maryland intramural grant to S.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck von Bodman S, Farrand S K. Capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis and pathogenicity in Erwinia stewartii require induction by an N-acylhomoserine lactone autoinducer. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5000–5008. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.5000-5008.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg D E. Transposon Tn5. In: Berg D E, Howe M M, editors. Mobile DNA. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 185–210. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cameron D N, Khambaty F M, Wachsmuth I K, Tauxe R V, Barrett T J. Molecular characterization of Vibrio cholerae O1 strains by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1685–1690. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1685-1690.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connell T D, Metzger D J, Wang M, Jobling M G, Holmes R K. Initial studies of the structural signal for extracellular transport of cholera toxin and other proteins recognized by Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4091–4098. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.4091-4098.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa J M, Loper J E. EcbI and EcbR: homologs of LuxI and LuxR affecting antibiotic and exoenzyme production by Erwinia carotovora subsp. betavasculorum. Can J Microbiol. 1997;43:1164–1171. doi: 10.1139/m97-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. Construction of an eae deletion mutant of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by using a positive selection suicide vector. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4310–4317. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4310-4317.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glass R I, Claeson M, Blake P A, Waldman R J, Pierce N F. Cholera in Africa: lessons on transmission and control for Latine America. Lancet. 1991;338:791–795. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90673-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardie K R, Lory S, Pugsley A P. Insertion of an outer membrane protein in Escherichia coli requires a chaperone-like protein. EMBO J. 1996;15:978–988. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassett D J, Ma J F, Elkins J G, McDermott T R, Ochsner U A, West S E, Huang C T, Fredericks J, Burnett S, Stewart P S, McFeters G, Passador L, Iglewski B H. Quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa controls expression of catalase and superoxide dismutase genes and mediates biofilm susceptibility to hydrogen peroxide. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:1082–1093. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hohn B, Collins J. A small cosmid for efficient cloning of large DNA fragments. Gene. 1980;11:291–298. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(80)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes R K, Vasil M L, Finkelstein R A. Studies on toxinogenesis in Vibrio cholerae. III. Characterization of nontoxinogenic mutants in vitro and in experimental animals. J Clin Invest. 1975;55:551–560. doi: 10.1172/JCI107962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Islam M S, Drasar B S, Sack R B. The aquatic flora and fauna as reservoirs of Vibrio cholerae: a review. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1994;12:87–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jobling M G, Holmes R K. Characterization of hapR, a positive regulator of the Vibrio cholerae HA/protease gene hap, and its identification as a functional homologue of the Vibrio harveyi luxR gene. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:1023–1034. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6402011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaper J B, Morris J G, Jr, Levine M M. Cholera. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:48–86. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karaolis D K, Somara S, Maneval D R, Jr, Johnson J A, Kaper J B. A bacteriophage encoding a pathogenicity island, a type-IV pilus and a phage receptor in cholera bacteria. Nature. 1999;399:375–379. doi: 10.1038/20715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klose K E, Mekalanos J J. Differential regulation of multiple flagellins in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:303–316. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.2.303-316.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klose K E, Mekalanos J J. Distinct roles of an alternative sigma factor during both free-swimming and colonizing phases of the Vibrio cholerae pathogenic cycle. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:501–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kornacker M G, Pugsley A P. Molecular characterization of pulA and its product, pullulanase, a secreted enzyme of Klebsiella pneumoniae UNF5023. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:73–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Latifi A, Winson M K, Foglino M, Bycroft B W, Stewart G S, Lazdunski A, Williams P. Multiple homologues of LuxR and LuxI control expression of virulence determinants and secondary metabolites through quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:333–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17020333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindeberg M, Collmer A. Analysis of eight out genes in a cluster required for pectic enzyme secretion by Erwinia chrysanthemi: sequence comparison with secretion genes from other gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7385–7397. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7385-7397.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manoil C, Beckwith J. TnphoA: a transposon probe for protein export signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:8129–8133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marsh J W, Taylor R K. Identification of the Vibrio cholerae type 4 prepilin peptidase required for cholera toxin secretion and pilus formation. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1481–1492. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin P R, Hobbs M, Free P D, Jeske Y, Mattick S J. Characterization of pilQ, a new gene required for the biogenesis of type 4 fimbriae in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:857–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menard R, Sansonetti P J, Parsot C. Nonpolar mutagenesis of the ipa genes defines IpaB, IpaC, and IpaD as effectors of Shigella flexneri entry into epithelial cells. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5899–5906. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.18.5899-5906.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metcalf W W, Wanner B L. Construction of new beta-glucuronidase cassettes for making transcriptional fusions and their use with new methods for allele replacement. Gene. 1993;129:17–25. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90691-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris J G, Jr, Sztein M B, Rice E W, Nataro J P, Losonsky G A, Panigrahi P, Tacket C O, Johnson J A. Vibrio cholerae O1 can assume a chlorine-resistant rugose survival form that is virulent for humans. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:1364–1368. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.6.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagamune K, Yamamoto K, Naka A, Matsuyama J, Miwatani T, Honda T. In vitro proteolytic processing and activation of the recombinant precursor of El Tor cytolysin/hemolysin (pro-HlyA) of Vibrio cholerae by soluble hemagglutinin/protease of V. cholerae, trypsin, and other proteases. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4655–4658. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4655-4658.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Overbye L J, Sandkvist M, Bagdasarian M. Genes required for extracellular secretion of enterotoxin are clustered in Vibrio cholerae. Gene. 1993;132:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90520-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pal S C. Laboratory diagnosis. In: Barua D, Greenough III W B, editors. Cholera. New York, N.Y: Plenum Medical Book Co.; 1992. pp. 229–251. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pugsley A P. The complete general secretory pathway in Gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:50–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.50-108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reeves P J, Whitcombe D, Wharam S, Gibson M, Allison G, Bunce N, Barallon R, Douglas P, Mulholland V, Stevens S, Walker D, Salmond G P C. Molecular cloning and characterization of 13 out genes from Erwinia carotovora subspecies carotovora: genes encoding members of a general secretion pathway (GSP) widespread in Gram-negative bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:443–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rice E W, Johnson C H, Clark R M, Fox K R, Reasoner D J, Dunnigan M E, Panigrahi P, Johnson J A, Morris J G., Jr Vibrio cholerae O1 can assume a “rugose” survival form that resists killing by chlorine, yet retains virulence. Int J Environ Health Res. 1993;3:89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roszak D B, Colwell R R. Survival strategies of bacteria in the natural environment. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:365–379. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.3.365-379.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russel M. Phage assembly: a paradigm for bacterial virulence factor export? Science. 1994;265:612–614. doi: 10.1126/science.8036510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russel M. Macromolecular assembly and secretion across the bacterial cell envelope: type II protein secretion systems. J Mol Biol. 1998;279:485–499. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandkvist M, Morales V, Bagdasarian M. A protein required for secretion of cholera toxin through the outer membrane of Vibrio cholerae. Gene. 1993;123:81–86. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90543-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandkvist M, Bagdasarian M, Howard S P, DiRita V J. Interaction between the autokinase EpsE and EpsL in the cytoplasmic membrane is required for extracellular secretion in V. cholerae. EMBO J. 1995;14:1664–1673. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sandkvist M, Michel L O, Hough L P, Morales V M, Bagdasarian M, Koomey M, DiRita V J, Bagdasarian M. General secretion pathway (eps) genes required for toxin secretion and outer membrane biogenesis in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6994–7003. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.6994-7003.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sandkvist M, Hough L P, Bagdasarian M M, Bagdasarian M. Direct interaction of the EpsL and EpsM proteins of the general secretion apparatus in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3129–3135. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.10.3129-3135.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shiba T, Hill R T, Straube W L, Colwell R R. Decrease in culturability of Vibrio cholerae caused by glucose. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2583–2588. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2583-2588.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor R K, Manoil C, Mekalanos J J. Broad-host-range vectors for delivery of TnphoA: use in genetic analysis of secreted virulence determinants of Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1870–1878. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.4.1870-1878.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomas S R, Trust T J. A specific PulD homolog is required for the secretion of paracrystalline surface array subunits in Aeromonas hydrophila. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3932–3939. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.3932-3939.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wai S N, Mizunoe Y, Takade A, Kawabata S-I, Yoshida S-I. Vibrio cholerae O1 strain TSI-4 produces the exopolysaccharide materials that determine colony morphology, stress resistance, and biofilm formation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3648–3655. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3648-3655.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wai S N, Mizunoe Y, Yoshida S-I. How Vibrio cholerae survive during starvation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;180:123–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watnick P I, Fullner K J, Kolter R. A role for the mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin in biofilm formation by Vibrio cholerae El Tor. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3606–3609. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.11.3606-3609.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watnick P I, Kolter R. Steps in the development of a Vibrio cholerae El Tor biofilm. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:586–595. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01624.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.White P B. The rugose variant of vibrios. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1938;46:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 50.White P B. The characteristic hapten and antigen of rugose races of cholera and El Tor vibrios. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1940;50:160–164. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamamoto K, Ichinose Y, Shinagawa H, Makino K, Nakata A, Iwanaga M, Honda T, Miwatani T. Two-step processing for activation of the cytolysin/hemolysin of Vibrio cholerae O1 biotype El Tor: nucleotide sequence of the structural gene (hlyA) and characterization of the processed products. Infect Immun. 1990;58:4106–4116. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.4106-4116.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yildiz F H, Schoolnik G K. Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor: identification of a gene cluster required for the rugose colony type, exopolysaccharide production, chlorine resistance, and biofilm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4028–4033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]