Abstract

Trypanosoma cruzi (Y strain)-infected interleukin-4−/− (IL-4−/−) mice of strains 129/J, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 showed no significant difference in parasitemia levels or end point mortality rates compared to wild-type (WT) mice. Higher production of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) by parasite antigen (Ag)-stimulated splenocytes was observed only for C57BL/6 IL-4−/− mice. Treatment of 129/J WT mice with recombinant IL-4 (rIL-4), rIL-10, anti-IL-4, and/or anti-IL-10 monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) did not modify parasitism. However, WT mice treated with rIL-4 and rIL-10 had markedly increased parasitism and suppressed IFN-γ synthesis by spleen cells stimulated with parasite Ag, concanavalin A, or anti-CD3. Addition of anti-IL-4 MAbs to splenocyte cultures from infected WT 129/J, BALB/c, or C57BL/6 mice failed to modify IFN-γ synthesis levels; in contrast, IL-10 neutralization increased IFN-γ production and addition of rIL-4 and/or rIL-10 diminished IFN-γ synthesis. We conclude that endogenous IL-4 is not a major determinant of susceptibility to Y strain T. cruzi infection but that IL-4 can, in association with IL-10, modulate IFN-γ production and resistance.

Trypanosoma cruzi is the etiologic agent of Chagas' disease in humans. This digenetic protozoon causes a systemic infection in humans and in other mammals that is controlled by T-cell-dependent immune responses but not completely eliminated. Control of the acute phase of infection is critically dependent on cytokine-mediated macrophage activation of intracellular killing. Treatment of mice with anti-gamma interferon (anti-IFN-γ), anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF), and anti-interleukin-12 (anti-IL-12) neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) leads to aggravation of the disease, reinforcing the importance of these cytokines in the in vivo resistance to infection (2, 3, 11, 18). Furthermore, although neutralization of IL-10 MAbs was not always effective at changing the course of infection, the importance of IL-10 in the regulation of parasitism and IFN-γ production was shown using mice with disrupted IL-10 genes (2, 12). The importance of IL-4 in determining susceptibility to infection has not yet been fully determined. On the basis of in vitro testing, two contrasting roles for IL-4 have been described: enhancement of intracellular T. cruzi destruction by macrophages (19) and inhibition of IFN-γ-mediated trypanocidal activity (9). Low levels (less than 0.32 ng/ml) of IL-4 in splenocyte culture supernatants from mice infected with T. cruzi have been reported (1, 2). However, IL-4 secretion by spleen cells (SC) was associated with enhanced susceptibility in T. cruzi Tulahúen strain-infected BALB/c mice (10). Treatment with a neutralizing anti-IL-4 MAb decreased parasitemia levels and increased survival of BALB/c mice infected with the reticulotropic Tulahúen or RA strain of T. cruzi, but did not change either parasitemia or mortality levels in CL strain-infected mice (14).

In order to clarify the importance of IL-4 in T. cruzi infection, we studied the responses of 129/J, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 mice with disruption in the IL-4 genes (IL-4−/−) and of the respective wild-type (WT) mice infected with the Y strain of T. cruzi. This strain is widely used in experimental T. cruzi infections and is also a reticulotropic strain (4). In addition, we investigated the effects of treatment of T. cruzi-infected mice and of in vitro treatment of SC cultures with neutralizing anti-IL-4 MAbs or with recombinant IL-4 (rIL-4), either alone or in combination with, respectively, anti-IL-10 MAbs or with rIL-10, on the course of infection and cytokine production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and infection with T. cruzi.

Ten- to 12-week-old female 129/J, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 IL-4−/− and WT mice were used. 129/J IL-4−/− and WT mice were bred at the DNAX Research Institute. BALB/c IL-4−/− and C57BL/6 IL-4−/− mice were a gift from Luiz Rizzo and were bred, as well as their WT counterparts, at the Department of Immunology, Instituto Ciências Biomédicas, Universide de São Paulo. All mice were bred and maintained in specific-pathogen-free conditions and housed in microisolator cages with ad libitum access to food and water. Groups of 5 or 6 mice were infected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with T. cruzi Y strain blood trypomastigotes (BT) obtained as previously described (7). WT and IL-4−/− mice of the highly susceptible 129/J strain were infected with 500 BT, and BALB/c (moderately susceptible) and C57BL/6 (resistant) mice were infected with 5,000 BT. Parasitemia counts were performed by counting the parasites in 5 μl of citrated blood obtained from the lateral tail veins. Mortality was evaluated by daily inspection of the cages.

Cytokines and anticytokine MAbs and in vivo treatments.

129/J WT mice were treated with the anti-IL-4 MAbs (11B11) or with murine rIL-4 in doses and schedules that have been shown previously to be effective in vivo (6, 15); 11B11 and rIL-4 were given alone or in association with anti-IL-10 MAb 2A5 or murine rIL-10, respectively. The rat anti-mouse cytokine MAbs, dissolved in sterile 0.15 M NaCl, were administered i.p. on days 0 (before infection) and 7 after infection in the following doses per animal: anti-IL-4 11B11 (immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1]), 5 and 2.5 mg; anti-β-galactosidase GL 113 isotype control (IgG1), 5 and 2.5 mg; anti-IL-10 2A5 (IgG1) or anti-IFN-γ XMG1.2 (IgG1), 2 and 1 mg. The recombinant cytokines rIL-4 and rIL-10 were a gift from Satish Menon (DNAX Research Institute). rIL-4 was injected i.p. (5 μg complexed to 50 μg of MAb 11B11) every third day (8), and rIL-10 was injected i.p. daily (20 μg/day/mouse).

Spleen cell cultures and in vitro treatments with cytokines or MAbs.

SC from WT or IL-4−/− mice of strains 129/J, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 or from 129/J WT mice treated in vivo with cytokines or anticytokines were obtained on day 11 after infection as previously described (1) and cultured at 8 × 106/ml (0.5 ml in 24-well plates) in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and penicillin and streptomycin (100 U/ml and 100 μg/ml, respectively) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). The cultures were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 MAbs (145-2C11; American Type Culture Collection). Individual wells were incubated with 0.2 ml of anti-CD3 MAbs diluted to 10 μg/ml in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.0 (PBS), for 18 h at 4°C and washed three times with PBS before the cells were added (1). Alternatively, SC cultures were stimulated with 2 × 106 frozen-thawed tissue culture trypomastigotes (trypomastigotes' antigen [T-Ag]) prepared as described previously (7). In some experiments, cultures were also stimulated with concanavalin A (ConA) (Sigma Chemical Co.) at a concentration of 5 μg/ml. Treatment in vitro with cytokines or neutralizing MAbs of SC cultures from WT mice was done by adding at the beginning of the cultures the MAbs 11B11 (anti-IL-4) and/or 2A5 (anti-IL-10) at 20 μg/ml or GL 113 (isotype control) at 40 μg/ml or the recombinant cytokines rIL-4 and/or rIL-10 at 50 ng/ml. Supernatants were collected after 20 and 72 h, and the cytokines from duplicate cultures were measured by two site sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, as previously described (1, 2).

Statistical analysis.

Groups of mice for parasitemia determinations consisted of five or six animals. Results were analyzed by analysis of variance followed by Dunn's nonparametric test. Differences in cytokine production levels in culture were analyzed by Bonferroni's test.

RESULTS

Parasitemia and mortality of WT versus IL-4−/− mice.

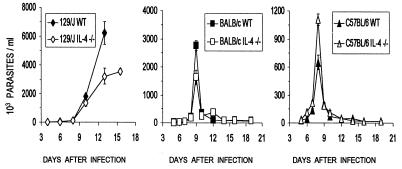

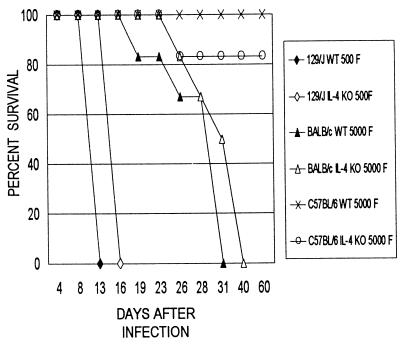

T. cruzi-infected WT and IL-4−/− mice of strains 129/J, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 showed very similar parasitemia levels during the infection. Variations on the order of a 50% reduction (129/J) or increase (BALB/c and C57BL/6) in parasite counts in IL-4−/− mice, in comparison to WT mice, were observed on the days of peak parasitemia levels (Fig. 1). However, these differences were not statistically significant. Analysis of the cumulative survival data (Fig. 2) showed a slight increase in survival time for IL-4−/− mice of strains 129/J (3 days) and BALB/c (9 days for 50% of the mice) in comparison with their respective WT; none, however, survived after infection. Mice from the resistant C57BL/6 strain, either WT or IL-4−/−, had, respectively, 100 and 80% survival rates after infection.

FIG. 1.

Parasitemia levels of IL-4−/− and WT mice of strains 129/J, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 infected, respectively, with 500, 5,000, and 5,000 Y strain T. cruzi BT. Values are arithmetic means ± standard deviations for five mice per group. Differences were found to be not significant when analyzed by analysis of variance and the nonparametric Dunn test. Data are representative of two experiments.

FIG. 2.

Survival rates of IL-4−/− and WT mice of strains 129/J, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 infected, respectively, with 500, 5,000, and 5,000 Y strain T. cruzi BT (n = 10 to 12 mice per group). KO, knockout.

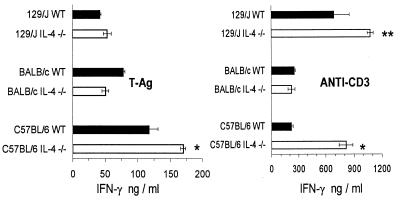

IFN-γ production by SC from infected WT versus IL-4−/− mice.

Cultured SC from IL-4−/− mice of strains C57BL/6 and 129/J produced higher levels of IFN-γ in culture than those from their WT counterparts after polyclonal stimulation with anti-CD3 (Fig. 3). When SC were stimulated with parasite antigen (T-Ag), however, higher production of IFN-γ by IL-4−/− mice than by WT mice was seen only for the C57BL/6 strain. BALB/c mice, WT and IL-4−/−, showed similar levels of IFN-γ production by SC stimulated with either anti-CD3 or T-Ag. IL-4 production in cultures from WT mice of the three strains was below detection levels (156 pg/ml).

FIG. 3.

IFN-γ production by SC from IL-4−/− and WT 129/J, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 mice infected with Y strain T. cruzi as indicated for Fig. 1. Cultures from mice infected for 11 days were stimulated with T-Ag or with plate-bound anti-CD3, and supernatants were collected 72 h later. Shown are arithmetic means ± standard deviations from duplicate cultures. ∗ and ∗∗, significant differences between WT and IL-4−/− mice (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively). Data are representative of two experiments.

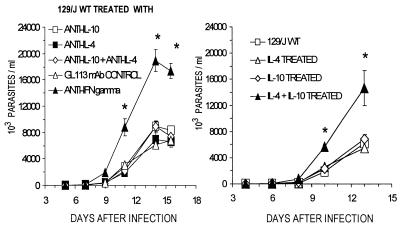

Treatment of mice with anti-IL-4 and/or anti-IL-10 MAbs or with rIL-4 and/or rIL-10.

Having found no significant differences between the courses of parasitemia in WT and IL-4−/− mice, we investigated whether treatment with anti-IL-4 plus anti-IL-10 neutralizing MAbs or with the respective recombinant cytokines would alter the course of infection or modify IFN-γ synthesis. We did not observe significant changes of parasitemia levels in anti-IL-4- and in anti-IL-4- and/or anti-IL-10-treated 129/J mice infected with T. cruzi Y strain compared to controls injected with the GL 113 control MAb; treatment with anti-IFN-γ MAbs, however, resulted in marked elevation of parasitemia levels (Fig. 4). In addition, the levels of IFN-γ produced by cultured SC taken from anti-IL-4- and/or anti-IL-10-treated mice, stimulated with antigen (Fig. 5) or with ConA or anti-CD3 (Fig. 6), were not significantly different from those obtained in SC cultures from untreated or control antibody-treated WT mice. SC from mice treated with anti-IFN-γ MAbs in vivo produced higher levels of this cytokine when restimulated in vitro with T-Ag (Fig. 5) or with ConA, but not upon stimulation with anti-CD3 (Fig. 6).

FIG. 4.

Parasitemias of WT 129/J mice infected with 500 parasites and treated with rIL-4, rIL-10, or rIL-4 plus rIL-10 or with the rat anti-mouse cytokine MAbs anti-IL-4 (11B11), anti-IL-10 (2A5), anti-IL-4 plus anti-IL-10, or anti-IFN-γ (XMG 1.2) or with isotype control MAb anti-β-galactosidase (GL 113) at the doses indicated in Materials and Methods. Shown are arithmetic means ± standard deviations from five mice. ∗, significant difference (P < 0.01). Data are representative of two experiments.

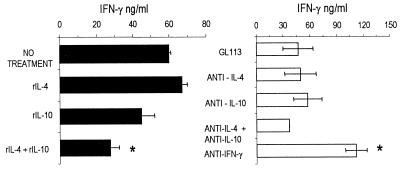

FIG. 5.

IFN-γ production by SC (day 11 of infection) from WT 129/J mice infected with 500 parasites, treated as indicated for Fig. 4, and stimulated in culture for 72 h with T-Ag. Shown are arithmetic means ± standard deviations from duplicate cultures. ∗, significant difference (P < 0.01). Data are representative of two experiments.

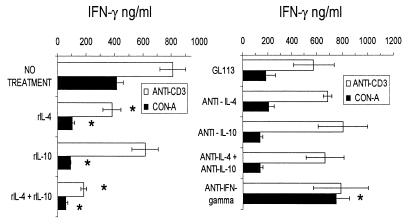

FIG. 6.

IFN-γ production by SC (day 11 of infection) from WT 129/J mice infected with 500 parasites, treated as indicated for Fig. 4, and stimulated in culture for 72 h with ConA or with anti-CD3. Shown are arithmetic means ± standard deviations from duplicate cultures. ∗, significant difference (P < 0.01). Data are representative of two experiments.

Parasitemia levels were markedly increased by the combined treatment with rIL-4 and rIL-10, whereas treatment with either cytokine alone failed to modify parasite blood counts (Fig. 4). The combined treatment also resulted in markedly reduced IFN-γ production by cultured SC stimulated in vitro with T-Ag or with ConA or anti-CD3 (Fig. 5 and 6). Treatment with rIL-4 or with rIL-10 alone led to a reduction of IFN-γ production by SC in cultures stimulated with ConA (Fig. 6) but not with T-Ag (Fig. 5), while only rIL-4 treatment reduced IFN-γ levels in anti-CD3-stimulated cultures (Fig. 6).

Treatment of SC cultures from WT mice with anti-IL-4 or anti-IL-10 MAbs or with rIL-4 and/or rIL-10.

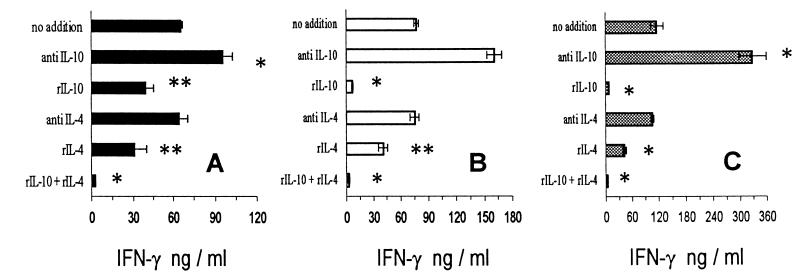

Treatment of T-Ag-stimulated SC cultures obtained from T. cruzi-infected WT 129/J, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 mice with anti-IL-10 led to increased IFN-γ production levels when endogenously produced IL-10 was neutralized by the in vitro treatment. In contrast, no such effect was seen when the cultures were treated with neutralizing anti-IL-4 MAbs (Fig. 7). However, either rIL-4 or rIL-10 added to the cultures inhibited IFN-γ synthesis, and the combined addition of the cytokines markedly suppressed IFN-γ production. Anti-CD3-stimulated cultures were treated in the same way, and anti-IL-10 addition resulted in a moderate increase of IFN-γ production, whereas it was not changed by anti-IL-4 treatment (data not shown). IL-4 plus IL-10 additions were moderately inhibitory of anti-CD3-stimulated IFN-γ synthesis (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

IFN-γ production by T-Ag-stimulated SC from WT 129/J (A), BALB/c (B), and C57BL/6 (C) mice infected with Y strain T. cruzi as indicated for Fig. 1. The cultures were treated in vitro with rIL-4 and/or rIL-10 (50 ng/ml) or with anti-IL-4 or anti-IL-10 MAbs (20 μg/ml). Supernatants were collected at 72 h. Shown are arithmetic means ± standard deviations from duplicate cultures. ∗ and ∗∗, significant differences (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively). Data are representative of two experiments.

DISCUSSION

The data presented in this paper show that endogenous production of IL-4 is not a critical determinant of susceptibility to T. cruzi Y strain infection because complete deprivation of IL-4 by genetic disruption of the corresponding gene failed to modify levels of parasitemia and mortality in three inbred mouse strains that ranged from highly susceptible to resistant to the infection. These observations contrast with the reduction of parasitemia levels of the order of 4- to 10-fold observed in IL-10−/− mice (2, 12). As previous results reported a protective effect of anti-IL-4 MAb treatment in mice infected with the Tulahúen or RA strains of T. cruzi (14), we also treated WT mice with high doses of anti-IL-4 MAb in order to assess the effects of IL-4 neutralization on the course of infection. Considering that the IL-4-neutralizing effects of MAb 11B11 have been documented in both in vivo and in vitro administration schedules (6, 15), our failure to find an effect of this MAb on parasitemia (Fig. 4) or on in vitro IFN-γ production by SC cultures from anti-IL-4-treated mice (Fig. 5 and 6) or when the MAb was added in vitro to SC cultures from WT mice (Fig. 7) suggests that, in Y strain T. cruzi infection, endogenously produced IL-4 does not significantly limit resistance or IFN-γ production. The high IFN-γ and low IL-4 production during infection and the observation that, even when IFN-γ was neutralized by the MAb, IL-4 production reached levels of only 0.62 ng/ml (1) (data not shown) also support this interpretation.

The lack of effect on T. cruzi parasitemia levels by in vivo treatment with the high doses (3 mg) of anti-IL-10 used in this study or with low doses (200 μg) has been reported before (2). Although in vivo anti-IL-10 treatment of mice had no effect on the course of parasitemia and on the subsequent IFN-γ in vitro production by SC taken from these animals, the addition of anti-IL-10 MAbs to cultures enhanced IFN-γ production by SC from infected mice, indicating that endogenous IL-10 has a significant regulatory effect on IFN-γ production in the three tested mouse strains (Fig. 7). Furthermore, IL-10−/− mice, besides developing lower parasitemias, had increased production of IFN-γ, nitric oxide, and TNF alpha (TNF-α) (2, 12), the latter associated with immune hyperreactivity and earlier mortality (12). Treatment of mice with both anti-IL-4 and anti-IL-10 MAbs also failed to modify parasitemia levels. In this context, treatment of IL-10−/− mice with anti-IL-4 MAbs also did not alter the evolution of T. cruzi infection in these mice (2). A group of mice treated with anti-IFN-γ MAbs, which resulted in very severe aggravation of the infection, was included as a positive control. SC from these mice produced higher levels of IFN-γ than those from control mice upon in vitro stimulation with T-Ag or ConA but not in response to anti-CD3 stimulation (Fig. 5 and 6). This higher in vitro production of IFN-γ correlated with the enhanced proliferation in response to T-Ag and ConA (but not to anti-CD3) by SC obtained from anti-IFN-γ-treated T. cruzi-infected mice (T-Ag-stimulated control, 9,066 ± 1,775 cpm; T-Ag-stimulated anti-IFN-γ-treated SC, 58,870 ± 10,302 cpm; ConA-stimulated control, 148,214 ± 2,624 cpm; ConA-stimulated anti-IFN-γ-treated SC, 311,238 ± 9,507 cpm; anti-CD3-stimulated control, 248,206 ± 12,581 cpm; anti-CD3-stimulated anti-IFN-γ treated SC, 276,615 ± 20,373 cpm). It has been shown that IFN-γ, by stimulating nitric oxide production, is a mediator of immunosuppression (1) and apoptosis (13) in T. cruzi infection.

Daily administration of rIL-4 or rIL-10 (20 μg/mouse) did not change the course of parasitemia in 129/J WT mice or change IFN-γ production levels by SC stimulated with T-Ag. However, each cytokine was acting systemically, as evidenced by the decrease of IFN-γ synthesis by SC from treated mice upon in vitro stimulation with ConA or anti-CD3. Evidence that rIL-4 or rIL-10 can also modulate an already-primed IFN-γ response was provided by in vitro experiments, where the addition of either cytokine to cultured SC from BALB/c, 129/J, or C57BL/6 infected mice decreased IFN-γ production. The combined treatment with rIL-4 and rIL-10 led to a marked increase in the parasitemia of 129/J mice accompanied by a significant decrease in IFN-γ synthesis by SC cultures in response to all stimuli. Besides reducing IFN-γ synthesis, both cytokines can directly counteract IFN-γ-mediated macrophage microbicidal activity and thus enhance parasite survival (9, 17). We had previously shown that the in vivo rIL-10 dose of 20 μg/mouse/day was suboptimal and that effects on parasitemia levels were seen at a dose of 40 μg/day (2). Nevertheless, when IL-4 treatment was associated with IL-10, albeit at a suboptimal concentration, a marked additive effect was observed. These results indicate that IFN-γ production can be regulated in vivo by IL-4 and IL-10. This is consistent with the suppression of IFN-γ production and aggravation of infection observed in T. cruzi-infected mice that had been injected with IL-4- and IL-10-producing T-Ag-specific TH2 lymphocyte blasts (5). However, we found no evidence that SC from IL-4–IL-10-treated mice had evolved towards a T2 pattern of cytokine secretion, as IL-4 production by cultured SC was consistently below detection levels. Taken together, our data suggest that endogenously produced IL-4 is not a major cytokine regulator of IFN-γ production or a determinant of susceptibility in the acute phase of Y strain T. cruzi infection. In contrast, IL-10, as previously shown, is much more important at limiting resistance (2, 12, 16). Nevertheless, when associated with IL-10, IL-4 can constitute a powerful modulator of IFN-γ production and T1 activation during infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

DNAX Research Institute is supported by Schering-Plough Co. Partial support was provided by grants from FAPESP. Ana Paula Galvão da Silva was supported by a FAPESP fellowship.

We thank Satish Menon for providing the recombinant cytokines and Luiz Rizzo for reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrahamsohn I A, Coffman R L. Cytokine and nitric oxide regulation of the immunosuppression in Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J Immunol. 1995;155:3955–3963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrahamsohn I A, Coffman R L. Trypanosoma cruzi: IL-10, TNF, IFN-γ and IL-12 regulate innate and acquired immunity to infection. Exp Parasitol. 1996;84:231–244. doi: 10.1006/expr.1996.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aliberti J C S, Cardoso M A G, Martins G A, Gazinelli R T, Vieira L Q, Silva J S. Interleukin-12 mediates resistance to Trypanosoma cruzi in mice and is produced by murine macrophages in response to live trypomastigotes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1961–1967. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.1961-1967.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrade S G. Tentative grouping of different Trypanosoma cruzi strains in some types. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 1976;18:140–141. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbosa-de Oliveira L C, Curotto-de-Lafaille M A, Lima G M C, Abrahamsohn I A. Antigen-specific IL-4 and IL-10 secreting CD4+ lymphocytes increase in vivo susceptibility to Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Cell Immunol. 1996;170:41–53. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatelain R, Varkila K, Coffman R L. IL-4 induces a Th2 response in Leishmania major infected mice. J Immunol. 1992;148:1182–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curotto-de-Lafaille M A, Barbosa-de Oliveira L C, Lima G M C, Abrahamsohn I A. Trypanosoma cruzi: maintenance of parasite-specific T cell responses in lymph nodes during the acute phase of the infection. Exp Parasitol. 1990;70:164–174. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(90)90097-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finkelman F D, Madden K B, Morris S C, Holmes J M, Boiani I M, Katona C R, Maliszewski R. Anti-cytokine antibodies as carrier protein. Prolongation of in vivo effects of exogenous cytokines by injection of cytokine-anti-cytokine antibody complexes. J Immunol. 1993;151:1235–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golden J M, Tarleton R L. Trypanosoma cruzi: cytokine effects on macrophage trypanocidal activity. Exp Parasitol. 1991;72:391–402. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(91)90085-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoft D F, Lynch R G, Kirchhoff L V. Kinetic analysis of antigen-specific immune responses in resistant and susceptible mice during infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. J Immunol. 1993;151:7038–7047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunter C A, Slifer T, Araujo F. Interleukin-12-mediated resistance to Trypanosoma cruzi is dependent on tumor necrosis factor alpha and gamma interferon. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2381–2386. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2381-2386.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunter C A, Ellis-Neyes L A, Slifer T, Kannaly S, Grünig G, Fort M, Rennick D, Araujo F G. IL-10 is required to prevent immune hyperactivity during infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. J Immunol. 1997;158:3311–3316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martins G A, Cardoso M A G, Aliberti J C S, Silva J S. Nitric oxide-induced apoptotic cell death in the acute phase of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. Immunol Lett. 1998;63:113–120. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(98)00066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petray P B, Rottenberg M E, Bertot G, Corral R S, Diaz A, Orn A, Grinstein S. Effect of anti-gamma-interferon and anti-interleukin-4 administration on the resistance of mice against infection with reticulotropic and myotropic strains of Trypanosoma cruzi. Immunol Lett. 1993;35:77–80. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(93)90151-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powrie F, Menon S, Coffman R L. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-10 synergize to inhibit cell-mediated immunity in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2223–2229. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reed S G, Brownell C E, Russo D M, Silva J S, Grabstein K H, Morrissey P J. IL-10 mediates susceptibility to Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J Immunol. 1994;153:3135–3140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silva J S, Morrisey P J, Grabstein K H, Mohler K M, Anderson D, Reed S G. Interleukin-10 and interferon γ regulation of experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J Exp Med. 1992;175:169–174. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torrico F, Heremans H, Rivera M T, Van-Marck E, Billiau A, Carlier Y. Endogenous IFN-gamma is required for resistance to acute Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. J Immunol. 1991;146:3626–3632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wirth J J, Kierszenbaum F, Zlotnik A. Effects of IL-4 on macrophage functions: increased uptake and killing of a protozoan parasite (Trypanosoma cruzi) Immunology. 1989;66:296–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]