Abstract

Objectives

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a severe impact on people across the world, particularly older adults who have a higher risk of death and health complications. We aimed to explore older adults’ intention towards COVID-19 vaccination and factors that influenced their motivation to get vaccinated.

Study design

A qualitative study was conducted in New South Wales, Australia (April 2021), involving interviews with older adults (aged 70 years and older).

Methods

In-depth interviews were carried out with 14 older adults on their perceptions around COVID-19 vaccination. The COVID-19 vaccination program had just commenced at the time of data collection. We thematically analysed interviews and organised the themes within the Behavioural and Social Drivers of Vaccination (BeSD) Framework.

Results

We found that most participants were accepting of COVID-19 vaccination. Participants’ motivation to get vaccinated was influenced by the way they thought and felt about COVID-19 disease and vaccination (including perceptions of vaccine safety, effectiveness, benefits, COVID-19 disease risk, and vaccine brand preferences) and social influences (including healthcare provider recommendation, and influential others). The uptake of COVID-19 vaccination was also mediated by practical issues such as access and affordability.

Conclusions

Efforts to increase COVID-19 vaccination acceptance in this population should focus on highlighting the benefits of vaccination. Support should be given to immunisation providers to enhance efforts to discuss and recommend vaccination to this high-risk group.

Keywords: COVID-19, Older adults, Vaccination, Vaccination acceptance, Australia, Qualitative

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2020 [1]. As of late July 2022, there were over 565 million confirmed cases, and 6.3 million confirmed deaths [2]. Protection against severe disease and death caused by COVID-19 and slowing the emergence of new variants will largely depend on people's acceptance and uptake of COVID-19 vaccines [3]. However, uptake is threatened by vaccine hesitancy, access issues and refusal of COVID-19 vaccines [4,5].

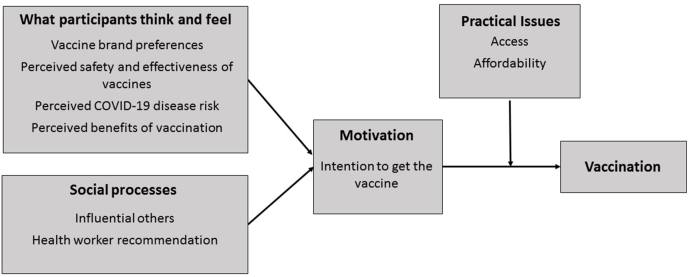

Vaccine uptake is driven by vaccination motivation and experiences. According to the Behavioural and Social Drivers (BeSD) of Vaccination Framework, [5] vaccination motivation is influenced by what people think and feel about vaccine preventable diseases and vaccines and by social processes related to vaccines (i.e., recommendation from a health worker). In addition, practical factors (i.e., access to services and information about vaccination) also influence vaccine uptake.

Vaccination uptake in older adults (those aged 70 years and over) was a focus of the Australian Government's rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine program [6]. Older adults were prioritised as a key group as increasing age is the leading risk factor for mortality and complications from COVID-19 infection [7]. The rollout in Australia began in late February 2021, and older adults were included a priority group. This was the second highest priority group after frontline health and aged care workers, disability and aged care residents and quarantine and border workers.

Previous research on vaccination uptake with Australian older adults has shown mixed results. For example, whilst influenza vaccination has previously reached coverage rates of over 70%, [8,9] awareness and uptake of pneumococcal vaccination is suboptimal, ranging from 39% to 69% [10,11]. In terms of COVID-19 vaccination, being older (>65 years old) has been associated with higher acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines, in Australia and internationally [[12], [13], [14]]. However, there is evidence that some older adults continue to remain uncertain and hesitant about getting a COVID-19 vaccine [15,16].

Understanding the specific factors that influence uptake of vaccines by priority groups during a pandemic (such as COVID-19 vaccines) early in a vaccine rollout is critical to achieving vaccine coverage among that priority group. Such information can inform interventions that aim to impact and modify a priority group's willingness to get vaccinated. Further, the BeSD Framework highlights that qualitative investigations into COVID-19 vaccination uptake can provide in-depth insights into local, context and time specific issues [5]. At the time of this study there was limited qualitative information about the specific drivers of COVID-19 vaccination among Australian older adults early on in the vaccine rollout. With these considerations in mind, this study aimed to qualitatively investigate the factors influencing COVID-19 vaccination decisions among adults aged 70 years and overliving in New South Wales (NSW) Australia, the most populous of the eight Australian states and territories.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

To address the research aims, we used a qualitative methods design involving individual interviews with older adults living in NSW. This study received approval from the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (2020/277).

2.2. Setting

Interviews were conducted between the 7th and 23rd of April, 2021. Australia commenced the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines (AstraZeneca and Pfizer) in phased stages, beginning on 21 February, 2021 [6]. Australian Government recommendations changed during our data collection period due to thrombosis with thrombocytopenia (TTS) emerging as a rare but serious side effect of the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine, especially in younger adults. As such, the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) recommended preferencing the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine for all people under 50 years of age on 8 April, 2021 [17]. The majority of our interviews took place after this announcement. Australia had low COVID-19 case numbers at this time, due to the pursuit of a near-elimination strategy [18].

2.3. Participant recruitment

Participants were recruited by a professional recruitment agency to meet predefined eligibility criteria (aged 70 years and over; a resident of NSW). The agency used this criteria to find participants through their database of potential respondents. Participants were provided with an information sheet detailing the purpose of the study. Those who provided written consent were scheduled for a 30-min phone or video conference-based interview at a time that was convenient for them. The research team did not have contact with participants prior to the commencement of the study. The interview guide asked participants about their experiences with previous vaccinations, feelings about, and intentions toward COVID-19 vaccination (see Supplementary File 1). Participants were reimbursed AUD60 (USD45) for their time.

2.4. Procedure

Interviews were conducted by BB, MS, and KB and analysed together with CK, all of whom are experienced researchers skilled in qualitative research methods. The research team worked as social scientists at an immunisation research centre at the time of this study. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed by an external transcription company. We conducted sampling and data analysis concurrently, stopping recruitment when our analysis of new transcripts no longer produced new categories.

2.5. Data analysis

We used thematic analysis to identify and extract information relevant to the research question [19,20]. Each transcript was read separately by two researchers who then created a combined analysis file. In addition to the pair analysis, we engaged in a group analysis, where the team met regularly to discuss combined analyses, reconcile differences in interpretation and agree on the emerging categories. Informed by the analysis of an initial seven transcripts, BB drafted a framework of key categories and sub-categories.

We used the key categories of the BeSD Framework, which is based on the ‘increasing vaccination model’ (see Fig. 1) [5,21]. This framework was utilised because it an evidence-based way to categories findings and has been used in other COVID-19 vaccination research with priority groups [22,23]. This framework was used as a guide for the remaining analysis and interpretation, during which it was expanded with new insights and refined through a group analysis process.

Fig. 1.

The adapted BeSD Framework showing key themes identified during the interviews.

In this paper, and consistent with the definition of vaccine hesitancy, [21] we refer to participants who were hesitant and the one participant who rejected COVID-19 vaccination as ‘hesitant’.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

In total, 14 participants aged between 70 and 83 years were interviewed (Table 1). At the time of the interviews, one participant had already received their first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine (AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine) and another five participants had booked an appointment for their first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. We assigned participants pseudonyms to ensure anonymity.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants.

| Category | Number of Participants |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 6 |

| Male | 8 |

| Age group | |

| 70–79 | 12 |

| 80+ | 2 |

| Location | |

| Metro | 8 |

| Regional/rural | 6 |

| Chronic health conditiona | |

| Yes | 9 |

| No | 5 |

| COVID-19 vaccination status | |

| Received one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine | 1 |

| Booked in to receive a COVID-19 vaccine | 5 |

| Not booked in or received a COVID-19 vaccine | 8 |

Health conditions included heart disease, inflammatory condition, lung disease, neurological condition, and immunocompromised.

3.2. Findings

Nine themes, aligned with each category of the BeSD Framework, were identified (see Fig. 1) and are described below, accompanied by a small number of de-identified quotes to illustrate key points.

3.3. What participants think and feel

3.3.1. Vaccine brand preferences

Participants who were accepting of COVID-19 vaccination often indicated that they had no preference for a particular COVID-19 vaccine brand. Conversely, most hesitant participants preferred Pfizer over the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine, primarily due to concerns about TTS.

“If we were able to have the Pfizer vaccine I probably wouldn’t worry as much, but I think the AstraZeneca one has got quite a few question marks over it, and I am a little bit concerned about it.” (Fiona, female, aged 74 years, hesitant)

Other hesitant participants did not want to receive either COVID-19 vaccine brand, saying that neither was appropriate for them.

3.3.2. Perceived safety and effectiveness of vaccines

Most accepting participants expressed confidence and trust in the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines. These participants reported gaining confidence from seeing the vaccines rolled out in other countries (e.g., USA, United Kingdom) and the corresponding small number of people who experienced negative side effects. These participants also commented that vaccination had been effective in reducing hospitalisation rates and the spread of COVID-19 infections in these countries.

“We follow England and America. Now, if they’re having good results, I mean, I think they had 20 or 40 people have had a few problems, but when you look at the millions that they’re doing, it’s such a small number.” (Paul, male, aged 77 years, accepting)

Hesitant participants expressed a lack of confidence in the safety of COVID-19 vaccines, expressing concerns about the side effects of the vaccines, from short-term side effects (e.g., severe fatigue, feeling unwell) to potentially unknown long-term side effects. The main safety concern was the risk of developing blood clots associated with the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. These participants reported that seeing this rare side effect emerge after the vaccine was made available to the public reinforced their hesitancy and their decision to “wait and see” about getting vaccinated.

These participants also described concerns with the speed of vaccine development and viewed the blood clotting side effect associated with the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine as evidence that the vaccine was ‘rushed’. One hesitant participant perceived that the elderly, as one of the first groups to receive the vaccines, were being used as “guinea pigs” for the vaccines.

“Something that’s been developed in 12 months, we’ve already seen there’s a very, very slight chance of blood clots. We’re worrying about what the future long-term ramification might be. It could be a hell of a lot worse than what COVID does to you.” (Ben, male, aged 70 years, hesitant)

Hesitant participants were also concerned about the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines, particularly in preventing people from getting COVID-19 disease or passing it on to others. Some perceived the data supporting high efficacy rates of these vaccines as weak, inconclusive and lacking credibility as it was provided by pharmaceutical companies.

3.3.3. Perceived COVID-19 disease risk

Accepting participants were more likely to perceive their personal risk of getting COVID-19 as high. Most accepting participants also reported feeling that they would be more susceptible to contracting severe COVID-19 disease due to their age or chronic health condition.

“I guess your immune system maybe is not as strong as you get older and therefore – and it seemed to be affecting older people much more than it did young people.” (Julia, female, aged 81 years, accepting)

Conversely, many hesitant participants perceived their personal risk of being infected by COVID-19 as low due to the low COVID-19 case numbers in their local area, state, or Australia more broadly. This contributed to the lack of urgency these participants reported about needing to get vaccinated, and expressed most commonly by participants living in regional NSW.

Hesitant participants also reported not feeling susceptible to contracting severe COVID-19 disease despite their age or chronic health condition. Participants that were in their early seventies and with no chronic health conditions were more likely to express this sentiment.

“I sort of feel 70 was an arbitrary figure, I live in this sort of delusion I’m still young and old people is anyone that’s older than me, and I’m still young. I didn’t feel susceptible at all.” (Ben, male, aged 70 years, hesitant)

3.3.4. Perceived benefits of vaccination

For accepting participants, the perceived benefits outweighed the potential risks associated with vaccinating. The main stated benefit was protection for themselves, their family and friends and the broader community. These participants reported a sense of responsibility to protect close family and friends and people more vulnerable than them.

“The key would be protection – protection for myself, and obviously people around me.” (Sean, male, aged 70 years, accepting)

Other benefits included the ability to travel domestically and internationally, getting life back to normal and less restrictions in visiting friends in aged care.

For some hesitant participants, the potential benefits did not outweigh the risks. Overall, the potential risk of experiencing an adverse effect was seen as higher and with more negative consequences, than the risk of contracting COVID-19.

Hesitant participants outlined two key benefits to vaccination that might convince them to vaccinate. Some hesitant participants said that if case numbers in NSW were higher, they would consider vaccinating for protection; some others indicated they would consider vaccinating to be able to travel.

“One of the main reasons is that I do want to do some overseas travel at some stage, and I don’t think that’s going to be on the cards for Australians until we’re all vaccinated.” (Fiona, female, aged 74 years, hesitant)

3.4. Social processes

3.4.1. Influential others

Participants identified family members and friends as important influences on their vaccination decisions. Accepting participants tended to report knowing someone around their age who had already been vaccinated and had had a positive experience or no side effects. This was reassuring to participants, and a motivation to vaccinate.

“The key reason for me was my friends- having the injections, and they were saying how simple it was to have it done.” (Petra, female, aged 74 years, accepting)

Some hesitant participants reported placing a high value on forming their own independent decisions about COVID-19 vaccination, rather than listening to others. Participants said that at t times this was a source of tension between themselves and families and/or friends.

“There’s been a bit of tension in my life because my children are into the, you know, work in the medical field and they’re in support of the COVID vaccination.” (Aaron, male, aged 71 years, rejecting)

Accepting participants described that they trusted the assurances from health authorities and the government about vaccinating against COVID-19. These participants praised the response from the federal and state governments in protecting people from COVID-19.

“We have assurances from the very top of government and from the top of the medical fraternity, both public and private that, yes, this is what we should be doing.” (Connor, male, aged 84 years, accepting)

While some hesitant participants reported trusting government advice on the public health measures implemented to slow the spread of COVID-19, some were disconcerted by the changing advice around who was eligible to receive the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. These participants perceived this advice as inconsistent and confusing, and evidence that health authorities were uncertain about the guidance they were providing to the public. These participants were particularly concerned that elderly, unwell people were being put at risk unnecessarily, as the side effects of the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine could cause harm and in some rare cases death.

3.4.2. Health worker recommendation

Accepting participants were more likely to report having received an explicit recommendation to vaccinate from their general practitioner (GP). These participants typically described having a long-standing relationship with their GP and trusting their opinion. Elderly participants with underlying health conditions sometimes also received an active recommendation from their medical specialist or were encouraged by chronic disease organisations to book in for vaccination.

Some hesitant participants also reported valuing their GP's advice and stated that it would influence their decision if they received a recommendation to be vaccinated.

“Specifically asking my doctor, since he knows my history of varicose veins whether or not I would be at more of a risk of blood clots through the AstraZeneca vaccination, because of my personal medical history.” (Fiona, female, aged 74 years, hesitant)

Some hesitant participants reported not receiving a recommendation from their GP yet, and this contributed to their impression that vaccination was not urgent.

3.5. Motivation

3.5.1. Intention to get a COVID-19 vaccine

Participants reported a range of COVID-19 vaccination intentions, from accepting (8 participants), hesitant (5 participants) and rejecting (1 participant). Accepting participants had either received one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, were booked in to receive the vaccine or indicated that they intended to receive the vaccine.

“I certainly will obviously have it. I’ve always thought that it was a good idea because at least it’s some finality to it all.” (Sean, male, aged 70 years, accepting)

Participants who were hesitant often planned to wait before vaccinating because they had specific concerns about COVID-19 vaccine safety and side effects.

“I just think we all have our own ways of thinking and our own ways of dealing with things, and that I want to wait and that I want to see a bit of outcome.” (Georgia, female, aged 70 years, hesitant)

The one participant who had no intention of vaccinating against COVID-19 stated that the health risks posed by the COVID-19 pandemic had been overstated by the Australian government.

3.6. Practical issues

3.6.1. Access

Many accepting participants who had made a booking to receive a COVID-19 vaccine reported finding the process easy and convenient. These participants had all booked through a GP practice, either online or by calling. For these participants, knowing that they were eligible to get vaccinated from government communications had encouraged them to book an appointment with their GP.

“Once you’ve had it, as I did yesterday, I’ve got to ask myself, “What’s all the fuss about it? It’s so straight forward. It’s just an easy process.” It’s not hard, and it’s not painful, and it takes no more than about 20 minutes.” (Leo, male, aged 70 years, accepting)

Participants who intended to get vaccinated in the future discussed several practical issues that made vaccination booking difficult. This included their GP practice not having enough stock when they went to make a booking or their local GP practice not offering COVID-19 vaccinations. This was a source of considerable frustration for these participants.

Hesitant participants living in regional areas of NSW perceived that the vaccine rollout in their area was slow. These participants interpreted the accelerated rollout in other areas as a lack of urgency to vaccinate in their area.

3.6.2. Affordability

Several participants who were less accepting of the vaccine reported financial costs associated with going to the GP and consulting about vaccination.

“I don’t really want to have to go to my doctor because now I’ve got to pay a consultation fee and I’m on a pension and that’s quite expensive.” (Fiona, female, aged 74 years, hesitant)

Conversely, knowing that there was no charge associated with vaccination consultation and/or vaccinating, as a key facilitator for accepting participants.

4. Discussion

This study contributes to the limited but growing literature on COVID-19 vaccination intentions, perceptions and experiences among older Australian adults. We found that participants’ motivation to vaccinate was influenced by their perceptions of COVID-19 disease risk, vaccine safety, effectiveness, benefits, vaccine brand preferences, and a provider and influential others recommending vaccination. The uptake of COVID-19 vaccine was also mediated by practical issues such as convenience, vaccine availability and affordability.

These findings are consistent with other international and Australian literature among older adults. Qualitative interviews with Swiss and Australian older adults found that those who reported benefits of vaccination, higher level of confidence in the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines, and reported that their provider recommended vaccination to them were more likely to accept vaccination [23,24]. Certain barriers to vaccination were also seen in other older adult samples, including a survey among 488 Saudi Arabian older adults conducted in late 2020. This research found that adverse side effects and safety and efficacy concerns were the main reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy [25]. Qualitative methods among Australian and UK older adults also uncovered similar reasons for hesitancy, including perceived vaccination risks outweighing the benefits and access issues [23,26].

Several other factors have emerged from the literature that were not found in our study. This includes perceptions of the severity of the potential long-term effects, the social influence of misinformation and the severity of previous infection with COVID-19 [23,27,28]. This is unsurprising as the BeSD Framework posits that the factors that influence vaccination uptake are context and time specific [5]. As such, the framework was useful to in the analysis process to categorise the key themes that emerged from this study.

Whilst most participants in this study were accepting of COVID-19 vaccination, a few did express hesitancy. This is consistent with research conducted in Australia, UK, and US [23,25,29]. Several participants in our study identified a few factors that might change their vaccination intention, including receiving a vaccination recommendation from their GP and being able to travel freely once vaccinated. While cautious when generalising findings to the wider Australian older adult population, our findings have a number of implications for COVID-19 vaccination strategies targeting older adults.

First, the central role of a GP or specialist in vaccination intentions and uptake, found in this study, has been reported previously [21]. Recent research suggests that a provider's recommendation is also a driver of vaccine acceptance for COVID-19 vaccines [30,31]. In light of this, we recommend that GPs and other immunisation providers (e.g., Aboriginal Medical Services, pharmacists, nurses) need to be supported to proactively recommend COVID-19 vaccination. This includes supporting providers' outreach to patients for example by calling or messaging eligible patients, and securing adequate remuneration for vaccination consultations.

Second, providers should also be supported with communication training and resources, particularly around how to have supportive and effective conversations with hesitant patients, and recommend vaccination. Providers in Australia reported that it has been challenging to stay up to date with COVID-19 vaccine information and recommendations, and this has impacted their confidence when talking with patients [23]. Providers in Australia have requested clear and simple resources to support their conversations with parents [32]. Conversation guides, decision aids and information sheets that outline the risks and benefits of vaccination could support discussions and informed consent.

Finally, findings from our study suggest that highlighting the benefits of vaccination, including the non-health benefits (i.e., ability to travel freely) may facilitate vaccination uptake among older adults. Previous vaccination messaging research has demonstrated that benefits-framed messaging is more effective than using fear in regards to vaccination [33]. Likewise, recent research demonstrated that messages that focus on the personal benefits of COVID-19 vaccination are effective in reducing vaccine hesitancy [34,35]. Highlighting such non-health benefits could tip people's risk-benefits calculation in favour of COVID-19 vaccination.

4.1. Limitations and future research

Recruiting participants through a recruitment company may have resulted in our study sample not being representative of the full range of perspectives of older adults living in NSW. It's possible that individuals with certain intentions and attitudes, positive or negative towards vaccination, were over-represented among individuals who agreed to participate in this study. Further, our participant's views may not represent those of older adults living outside of NSW and from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. However, the repeated emergence of key themes in the interviews suggests that the most salient ideas were captured. Further research with diverse communities would provide an understanding of their perceptions and experiences with COVID-19 vaccination.

We conducted this study at a particular point in time; participant's intentions, perceptions and experiences will likely have shifted over time, with the changes in vaccine availability and access, COVID-19 case numbers and public health advice. Continuous monitoring of older adults' sentiment towards COVID-19 vaccination is needed within the pandemic context. This may allow identification of variations in vaccination intentions over time and provide timely, accurate information that can be used by policymakers and service coordinators to tailor immunisation program and services.

5. Conclusions

This qualitative study highlights factors influencing older Australian adults' decision making around COVID-19 vaccination, at the start of the vaccine rollout. Encouragingly, most of the older adults were accepting and intended to vaccinate. As older adults are among those most affected by the negative consequences of COVID-19, however, it's important to focus on those who remain hesitant. Strategies to increase acceptance could involve highlighting the medical and non-medical benefits of COVID-19 vaccination, and supporting immunisation providers in their vaccination consultations with older adults. Findings from this study may inform the development of campaigns to promote vaccination acceptance and uptake during the COVID-19 pandemic and future pandemics.

Funding

All authors’ positions are funded by the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance. The COVID-19 Vaccination Messaging Study is funded via a grant from NSW Health.

Statement of ethical approval

This study received approval from the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (2020/277).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Bianca Bullivant reports financial support was provided by NSW Health. Maryke Steffens reports financial support was provided by NSW Health. Katarzyna Bolsewicz reports financial support was provided by NSW Health. Catherine King reports financial support was provided by NSW Health.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants for sharing their time and insights about COVID-19 vaccination.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhip.2022.100349.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.World Health Organization WHO director-general’s opening remarks at the media on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020. 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19--11-march-2020

- 2.World Health Organization WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. 2022. https://covid19.who.int/

- 3.World Health Organization COVID-19 advice for the public: getting vaccinated. 2022. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines/advice

- 4.Hou Z., Tong Y., Du F., Lu L., Zhao S., Yu K., et al. Assessing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, confidence, and public engagement: a global social listening study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021;23 doi: 10.2196/27632. https://www.jmir.org/2021/6/e27632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization Behavioural and social drivers of vaccination: tools and practical guidance for achieving high uptake. 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/354459?show=full Geneva, Licence, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 6.Australian Department of Health Australia's COVID-19 vaccine national roll-out strategy announced. 2021. https://www.health.gov.au/news/australias-covid-19-vaccine-national-roll-out-strategy-announced

- 7.Kang S.J., Jung S.I. Age-related morbidity and mortality among patients with COVID-19. Infect. Chemother. 2020;52:154–164. doi: 10.3947/ic.2020.52.2.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hull B., Hendry A., Dey A., Macartney K., McIntyre P., Beard F. Exploratory analysis of the first 2 years of adult vaccination data recorded on AIR. 2019. www.ncirs.org.au/sites/default/files/2019-12/Analysis%20of%20adult%20vaccination%20data%20on%20AIR_Nov%202019.pdf November 2019. Westmead, NSW, National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance.

- 9.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . 2011. 2009 Adult Immunisation Survey: Summary Results, Cat.https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/primary-health-care/2009-adult-vaccination-survey-summary-results/contents/summary no. PHE 135, Canberra. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank O., De Oliveira Bernardo C., González-Chica D.A., Macartney K., Menzies R., Stocks N. Pneumococcal vaccination uptake among patients aged 65 years or over in Australian general practice. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020;16:965–971. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1682844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trent M.J., Salmon D.A., MacIntyre C.R. Predictors of pneumococcal vaccination among Australian adults at high risk of pneumococcal disease. Vaccine. 2022;40:1152–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards B., Biddle N., Gray M., Sollis K. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance: correlates in a nationally representative longitudinal survey of the Australian population. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazarus J.V., Ratzan S.C., Palayew A., Gostin L.O., Larson H.J., Rabin K., et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat. Med. 2021;27:225–228. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seale H., Heywood A.E., Leask J., Sheel M., Durrheim D.N., Bolsewicz K., Kaur R. Examining Australian public perceptions and behaviors towards a future COVID-19 vaccine. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021;21:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-05833-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhagianadh D., Arora K. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among community-dwelling older adults: the role of information sources. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2022;41:4–11. doi: 10.1177/07334648211037507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malesza M., Wittmann E. Acceptance and intake of COVID-19 vaccines among older Germans. J. Clin. Med. 2021;10:1388. doi: 10.3390/jcm10071388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ATAGI ATAGI statement on AstraZeneca vaccine in response to new vaccine safety concerns. 2021. https://www.health.gov.au/news/atagi-statement-on-astrazeneca-vaccine-in-response-to-newvaccine-safety-concerns Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- 18.Australian Government Department of Health Our response to the pandemic. 2022. https://www.health.gov.au/health-alerts/covid-19/government-response

- 19.Clarke V., Braun V., Hayfield N. In: Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods. 3rd ed. Smith J.A., editor. SAGE Publications; London: 2015. Thematic analysis; p. 222. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tolley E.E., Ulin P.R., Mack N., Robinson E.T., Succop S.M. John Wiley & Sons; San Francisco: 2016. Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research. 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brewer N.T., Chapman G.B., Rothman A.J., Leask J., Kempe A. Increasing vaccination: putting psychological science into action. Psychol. Sci. Publ. Interest. 2017;18:149–207. doi: 10.1177/1529100618760521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolsewicz K.T., Steffens M.S., Bullivant B., King C., Beard F. “To protect myself, my friends, family, workmates and patients and to play my part”: COVID-19 vaccination perceptions among health and aged care workers in New South Wales, Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2021;18:8954. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18178954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufman J., Bagot K.L., Tuckerman J., Biezen R., Oliver J., Jos C., et al. Qualitative exploration of intentions, concerns and information needs of vaccine-hesitant adults initially prioritised to receive COVID-19 vaccines in Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Publ. Health. 2022;46:16–24. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.13184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fadda M., Suggs L.S., Albanese E. Willingness to vaccinate against Covid-19: a qualitative study involving older adults from Southern Switzerland. Vaccine X. 2021;8 doi: 10.1016/j.jvacx.2021.100108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Hanawi M.K., Alshareef N., El-Sokkary R.H. Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination among older adults in Saudi Arabia: a community-based survey. Vaccines. 2021;9:1257. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9111257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams L., Gallant A.J., Rasmussen S., Brown Nicholls L.A., Cogan N., Deakin K., et al. Towards intervention development to increase the uptake of COVID-19 vaccination among those at high risk: outlining evidence-based and theoretically informed future intervention content. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020;25:1039–1054. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malesza M., Wittmann E. Acceptance and intake of COVID-19 vaccines among older Germans. J. Clin. Med. 2021;1388:10. doi: 10.3390/jcm10071388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caycho-Rodríguez T., Tomás J.M., Carbajal-León C., Vilca L.W., Reyes-Bossio M., Intimayta-Escalante C., et al. Sociodemographic and psychological predictors of intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine in elderly Peruvians. Trends Psychol. 2021;30:206–223. doi: 10.1007/s43076-021-00099-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikolovski J., Koldijk M., Weverling G.J., Spertus J., Turakhia M., Saxon L., et al. Factors indicating intention to vaccinate with a COVID-19 vaccine among older US adults. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Enticott J., Gill J.S., Bacon S.L., Lavoie K.L., Epstein D.S., Dawadi S., et al. Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: a cross-sectional analysis—implications for public health communications in Australia. BMJ Open. 2022;12 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Metwali B.Z., Al-Jumaili A.A., Al-Alag Z.A., Sorofman B. Exploring the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers and general population using health belief model. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2021;27:1112–1122. doi: 10.1111/jep.13581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leask J., Carlson S.J., Attwell K., Clark K.K., Kaufman J., Hughes C., et al. Communicating with patients and the public about COVID-19 vaccine safety: recommendations from the collaboration on social science and immunisation. Med. J. Aust. 2021;215:9–12. doi: 10.5694/mja2.51136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nyhan B., Reifler J., Richey S., Freed G.L. Effective messages in vaccine promotion: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e835–e842. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berliner Senderey A., Ohana R., Perchik S., Erev I., Balicer R. Encouraging uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine through behaviorally informed interventions: national real-world evidence from Israel. 2021. Available at SSRN 3852345. [DOI]

- 35.Freeman D., Loe B.S., Yu L.M., Freeman J., Chadwick A., Vaccari C., et al. Effects of different types of written vaccination information on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK (OCEANS-III): a single-blind, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6:e416–e427. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00096-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.