Abstract

Nonopsonic interaction of host immune cells with pathogens is an important first line of defense. We hypothesized that nonopsonic recognition between type III group B streptococcus and human neutrophils would occur and that the interaction would be sufficient to trigger neutrophil activation. By using a serum-free system, it was found that heat-killed type III group B streptococci bound to neutrophils in a rapid, stable, and inoculum-dependent manner that did not result in ingestion. Transposon-derived type III strain COH1-13, which lacks capsular polysaccharide, and strain COH1-11 with capsular polysaccharide lacking terminal sialic acid demonstrated increased neutrophil binding, suggesting that capsular polysaccharide masks an underlying binding site. Experiments using monoclonal antibodies to complement receptor 1 and to the I domain or lectin site of complement receptor 3 did not inhibit binding, indicating that the complement receptors used for ingestion of opsonized group B streptococci were not required for nonopsonic binding. Nonopsonic binding resulted in rapid activation of cellular p38 and p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinases. This interaction was not an effective trigger for superoxide production but did promote release of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-8. The release of interleukin-8 was markedly suppressed by the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor SB203580 but was only minimally suppressed by the mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated kinase inhibitor PD98059. Thus, nonopsonic binding of type III group B streptococci to neutrophils is sufficient to initiate intracellular signaling pathways and could serve as an arm of innate immunity of particular importance to the immature host.

Group B streptococci (GBS) are a leading cause of neonatal sepsis and meningitis, with an incidence in the 1990s of 1 to 2 per 1,000 live births and a fatality rate of 5 to 12% (3). GBS also is recognized increasingly as a pathogen in adults, particularly in the elderly and in those with immunocompromising conditions (37). For optimal ingestion and killing by polymorphonuclear cells (PMN), GBS must be opsonized with capsular polysaccharide (CPS)-specific antibody and with complement, in particular the C3 fragments C3b and iC3b (8, 14, 39). The PMN immunoglobulin G (IgG) receptors FcγRII and FcγRIII and complement receptors 1 (CR1) (CD35) and CR3 (CD11b/CD18) mediate these interactions (1, 25, 39). Opsonin-mediated phagocytosis and killing of GBS have been evaluated extensively, but the potential nonopsonic interaction of GBS with human phagocytes is largely unexplored.

Several lines of investigation indicate that the nonopsonic association of GBS with host cells is biologically important. First, antibody- and complement-independent phagocytosis of serotypes Ia and III GBS by murine macrophages has been documented and has been shown to be CR3 dependent (2). Next, unopsonized GBS are equivalent to opsonized organisms in eliciting leukotriene B4 and interleukin-8 (IL-8) release from monocytes (33). In addition, encapsulated and unencapsulated type III GBS as well as their cell wall components elicit tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-6 and IL-1β production from adult and neonatal monocytes (44, 45, 47, 50). Kim et al. (20) have also shown that 26% of human cord sera containing ≤0.01 μg of type III GBS-specific antibody/ml exhibited efficient opsonophagocytosis and protective activity in vivo, independent of complement, IgM, or fibronectin. Nonopsonic interactions also are important in the immune response to other pathogenic microorganisms such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Neisseria meningitidis, mycobacteria, and yeasts (6, 23, 28, 42, 52). These interactions can trigger effects such as cytokine release, superoxide production, actin polymerization, phagocytosis, and cytokine production (27, 32, 46). While nonopsonic immune responses may be relatively inefficient (13, 46), they nonetheless have an important role in the initial host immune response as an arm of innate immunity.

The mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases have a central role in mediating signal transduction in response to a number of external stimuli (19, 55). The activities of p38 and extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK 1/2, p44/42) increase rapidly in response to N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (FMLP) or lipopolysaccharide, suggesting that these kinase cascades have a pivotal role in regulating PMN function (7, 24). The intracellular signaling pathways which regulate key PMN functions have been partially characterized, but the extent to which they contribute to PMN activation by GBS is undefined (5, 36).

Although antibody to CPS and an intact complement system promote the optimal immune response to type III GBS, phagocytosis and intracellular killing may be achieved in settings where CPS-specific antibody is deficient (9). Most newborn infants lack sufficient CPS-specific antibody to optimally mediate phagocytosis and also have immature complement-mediated opsonization, but they do not develop invasive type III GBS infection, despite exposure to or colonization with the organism (3, 10, 37). We hypothesized that nonopsonic interaction between type III GBS and PMN would occur and that the interaction would be sufficient to activate intracellular signaling pathways important to the host immune response. Our objective was to define whether innate immune mechanisms are important in host defense to GBS, particularly for the nonimmune or immunocompromised host.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PMN isolation.

PMN were isolated from fresh whole blood obtained from healthy adult volunteers, anticoagulated with citrate phosphate dextrose, sedimented with dextran, and then purified over a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient. Erythrocytes were eliminated by hypotonic lysis (39). Cell viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion after isolation of PMN and was consistently more than 92%. PMN were suspended in calcium- and magnesium-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for flow cytometry assays and in RPMI 1640 with l-glutamine supplemented with HEPES and gentamicin (50 μg/ml) (Life Technologies, Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) for MAP kinase and IL-8 assays. PMN were kept on ice and used within 4 h. All reagents and solutions contained endotoxin at ≤0.03 U/ml, as determined by Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Associates of Cape Cod, Woods Hole, Mass.).

Bacteria.

Three strains of type III GBS were used. Strain COH1 is an encapsulated strain originally isolated from the blood of an infant with type III GBS sepsis (34). Strain COH1-13, which lacks the type III GBS CPS, and strain COH1-11, which lacks the terminal sialic acid of the type III CPS, are isogenic mutants derived by transposon insertion mutagenesis (34). These strains were provided by Craig W. Rubens (University of Washington, Seattle) and were used in assays to determine the role of CPS in nonopsonic binding. An aliquot of stock solution of type III GBS stored at −70°C was grown overnight on blood agar plates. Colonies were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) to achieve mid-log-phase growth. Bacteria were harvested, washed in normal saline, and resuspended in PBS. The bacterial suspension was heat-killed at 60°C for 60 min, aliquoted, and stored at −20°C. All type III GBS strains utilized in subsequent experiments were heat-killed. The type III GBS used in the MAP kinase and IL-8 assays had an endotoxin level of ≤10 pg/ml at a concentration of 108 CFU/ml (Chromogenic LAL; Bio-Whittaker).

MAb.

Monoclonal antibodies (MAb) to PMN CR1 (CD35, clone E11) were purchased from Biogenesis (Sandown, N.H.), and MAb to CR3 (LM 2/1 and clone 44) were purchased from Biosource International (Camarillo, Calif.) and Pharmingen (San Diego, Calif.), respectively. A MAb to CD18 (TS 1/18) was obtained from Endogen (Woburn, Mass.). The MAb OKM1, directed to the lectin-dependent epitope of CR3, was kindly provided by Michelle Mariscalco (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex.). Isotypic nonbinding MAb MsIgG1 and IgG2b were purchased from Coulter Immunology (Hialeah, Fla.) for use as controls to each MAb employed.

Preparation of GBS.

An aliquot of heat-killed type III GBS was incubated with 0.05 mg of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.)/ml in 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate (pH 9.5) at room temperature for 24 h as described by Cantinieaux et al. (4). After being washed three times with PBS, the isolate was aliquoted and stored in a light-protected environment at −20°C until use. Uniformity of staining was determined by fluorescence microscopy and confirmed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis in a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, Calif.).

Flow cytometry assay for determining type III GBS-FITC–PMN interaction.

PMN (106; 100 μl) were incubated with type III GBS (107 CFU)-FITC (100 μl) and 100 μl of PBS for various time intervals. In some experiments, PMN were treated for 30 min with saturating concentrations of MAb E11 (10 μg/ml), LM 2/1 (10 μg/ml), clone 44 (10 μg/ml), OKM1 (10 μg/ml), TS 1/18 (20 μg/ml), or their respective isotypic controls (38, 41, 43, 53). Flow-cytometric analysis was performed using the Cell-Quest software program of the Becton Dickinson (Mountainview, Calif.) FACScan. PMN were gated according to the characteristic light scatter pattern. Logarithmic fluorescence intensity (x axis) was plotted versus relative cell number (y axis) and was displayed by monovariant histogram. Data from 5,000 PMN were analyzed for associated FITC fluorescence as a measure of bacterial association.

Binding versus ingestion.

External fluorescence was quenched with crystal violet (0.25 g/liter; Difco), and type III GBS-FITC interactions with PMN were analyzed within 1 min (29). Experiments also were performed after incubation of PMN with cytochalasin B (5 μg/ml) (Sigma Chemical Co.) for 30 min to inhibit phagocytosis. Flow-cytometric data with and without cytochalasin B were compared.

Western blot analysis of cellular MAP kinases p38 and p44/42.

Phosphorylation of threonine or tyrosine on MAP kinases is an accurate indicator of their activation (31, 55). Detection of the phosphorylated p38 and p44/42 was performed as follows. After PMN (107/ml) and type III GBS (108 CFU/ml), strain COH1, were incubated for various time intervals, the reaction mixture was quickly pelleted and washed with ice-cold PBS supplemented with 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 1 mM NaF. The mixture was resuspended in ice-cold lysis solution (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100 [pH 8.0], 1 μg each of leupeptin, pepstatin, and antipain/ml, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate) and allowed to lyse for 20 min on ice. The solution then was centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C (IEC Centra MP4R, Needham Heights, Mass.). The protein content was determined by the bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) using albumin as a standard. A protein sample (40 μg) from each reaction mixture was loaded and electrophoresed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–12 or 10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–12 or 10% PAGE) and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). The membranes were blocked in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST) supplemented with 5% skim milk for 1 h. The membranes were subsequently incubated with 1/500-diluted primary phosphospecific rabbit antibodies recognizing Thr 180- or Tyr 182-phosphorylated p38 MAP kinase or Thr 202- or Tyr 204-phosphorylated p44/42 MAP kinase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) at 4°C overnight. Membranes were washed with TBST for 10 min once, then for 5 min twice, and then were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-linked donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) as the secondary antibody at a dilution of 1/1,000 in TBST for 1 h at room temperature. After three washes with TBST, membranes were treated with enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (ECL +; Amersham) according to the manufacturer's instructions and the phosphorylated MAP kinases were detected by autoradiography. To confirm that equal amounts of cellular proteins were loaded, the membranes were cleared of the primary antibody-secondary antibody complex by incubation in stripping buffer (100 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, 62.5% Tris-HCl, pH 6.7) for 30 min at 50°C. They were then washed twice for 10 min with TBST, blocked with TBST supplemented with 5% skim milk for 1 h, and reprobed with rabbit antibody to total (unphosphorylated) p38 and p44/42 (New England Biolabs), followed by incubation with secondary horseradish peroxidase-linked donkey anti-rabbit antibody, and the total MAP kinases were detected by autoradiography.

IL-8 ELISA.

To detect IL-8 production, PMN (107/ml) were incubated with type III GBS strain COH1 (108 CFU/ml) for 24 h as described previously (55). PMN were incubated with compound SB203580, a specific inhibitor of the p38 MAP kinase, or with PD98059 (Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.), which inhibits the activation of MAP kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and thus p44/42 for 30 min at various concentrations. The cell-free supernatant was analyzed for IL-8 using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The lower limit of detection is 5 pg/ml.

Oxidative burst.

The following methods were used to detect the products of the PMN oxidative burst in response to type III GBS. For chemiluminescence, PMN (106/ml) were mixed with luminol (10−7 M) and stimulated with type III GBS (107 CFU/ml) or phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; 100 ng/ml) as a positive control. The mixture was agitated for 20 s and analyzed immediately on the liquid scintillation counter (LKB 1219 Rackbeta). Chemiluminescence was measured for 45 s for 10-min cycles for a total of seven cycles. In the 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) method, PMN incorporate the DCFH-DA and the diacetate moiety is cleaved to produce the nonfluorescent compound DCFH. The hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and peroxidases generated by activated PMN oxidize the intracellular DCFH to the fluorescent compound 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein. The green fluorescence produced by PMN is proportional to the amount of H2O2 generated. PMN (106/ml) were loaded with DCFH-DA (25 μM) for 15 min at 37°C. They were then stimulated either with type III GBS (107 CFU/ml) or PMA (100 ng/ml), and analyzed by FACS for change in PMN fluorescence as an indication of H2O2 and peroxidase production. Finally, in the hydroethidine (HE) method, the nonfluorescent compound HE is transformed to red fluorescent ethidium bromide by the superoxide anion O2−. Thus, PMN (106/ml) were loaded with HE (1 μg/ml) and subsequently stimulated with type III GBS (107 CFU/ml) or PMA (100 ng/ml), and the red fluorescence detected by FACS analysis was used as an indicator of O2− production.

Statistical analysis.

Unless otherwise stated, the results represent the means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) of three to five experiments. Levels of significance for comparisons between samples were determined using Student's unpaired t test (two tailed). P values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Nonopsonic binding of type III GBS with human PMN.

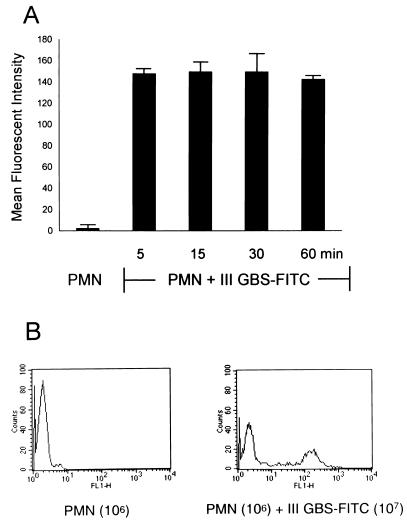

Upon incubation of PMN (106) with type III GBS-FITC strain COH1 (107 CFU), 40% ± 3% of PMN became associated with type III GBS-FITC, as evidenced by an increase in their mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) from 2% ± 0.2% to 148% ± 4% (Fig. 1A and B). This association was rapid, occurring within 5 min, and did not change at 15-min intervals for 1 h. This association was stable. It was not changed by washing and resuspension.

FIG. 1.

Type III GBS binds nonopsonically to PMN in a rapid and stable manner. (A) PMN (100 μl; 106) were incubated with heat-killed type III GBS-FITC (100 μl; 107 CFU) in a serum-free environment. PMN were gated according to their characteristic light scatter pattern, and data from 5,000 PMN were analyzed for increase in their MFI as an indicator of association with type III GBS-FITC. The graph shows the change in MFI of the 40% ± 3% participating PMN at this PMN-to-type III GBS ratio. This interaction occurred within 5 min, and the percentage of participating PMN and their MFI did not change, as shown by FACS analysis at 15-min intervals, for up to 1 h. (B) Histogram representative of one assay showing the MFI shift of participating PMN when incubated with type III GBS-FITC.

To determine the relative magnitude of the nonopsonic association, experiments were conducted with type III GBS-FITC opsonized for 15 min with serum containing a high concentration of antibody to type III GBS CPS (82 μg/ml), as determined by IgG ELISA. The levels of association of PMN with unopsonized and opsonized bacteria were compared. Opsonized and unopsonized type III GBS-FITC showed similar degrees of PMN association when analyzed within 5 min of incubation (39% ± 3% and 46% ± 1%, respectively). After 30 min of incubation, the unopsonized type III GBS exhibited 42% ± 3% PMN association while opsonized type III GBS exhibited 87% ± 1% PMN association. Thus, nonopsonic association occurred as promptly as that of opsonized type III GBS with PMN, but over time the magnitude of the association was not as great.

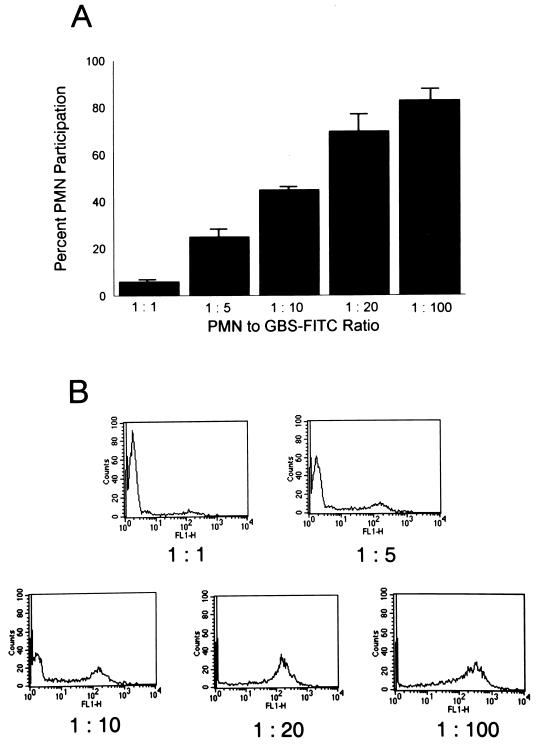

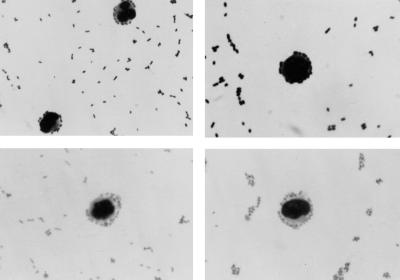

The inoculum dependence of the association was next evaluated. Participation by PMN increased from 6% ± 1% at a PMN-to-type III GBS-FITC ratio of 1 to 1 to 83% ± 5% at a ratio of 1 to 100 (Fig. 2A). Figure 2B is a family of representative histograms showing the shift in MFI of participating PMN as the type III GBS inoculum is increased. In addition, the nonopsonic binding of type III GBS to PMN was confirmed by direct microscopy (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

The nonopsonic interaction between PMN and type III GBS is inoculum dependent. (A) PMN (106) were incubated with increasing concentrations of heat-killed type III GBS-FITC. PMN were analyzed by flow cytometry for FITC association. The percentages of participating PMN are shown. (B) Representative family of histograms, where increasing PMN participation is evidenced by the shift in their MFI as the inoculum of type III GBS is increased.

FIG. 3.

Direct microscopy of the nonopsonic binding of type III GBS to PMN. PMN (106) were incubated for 5 min with heat-killed type III GBS (107 CFU). Smears of the reaction mixture were stained with NEAT STAIN (Midland Biomedical, Paulsboro, N.J.). Magnification, ×100.

Type III GBS is bound to but not ingested by PMN.

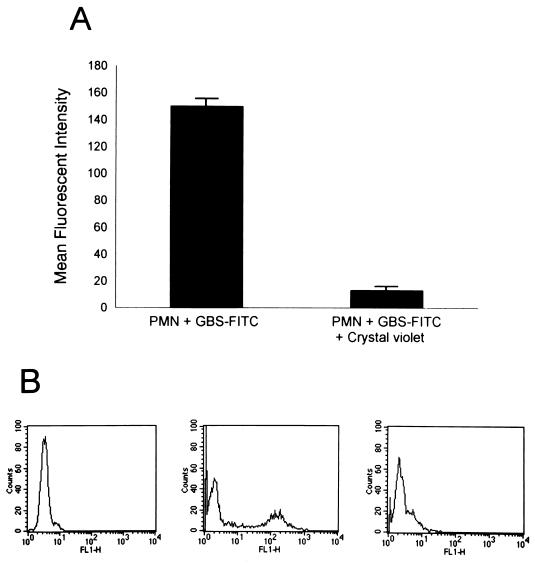

After PMN and type III GBS-FITC were allowed to interact and the association was confirmed as described above, extracellular fluorescence was quenched by the addition of crystal violet at 0.25 g/liter. The reaction mixture then was subjected to FACS analysis within 1 min to avoid the lysosomotropic effect of the dye. The MFI of PMN was reduced by 91% ± 3% (Fig. 4A and B). This extracellular quenching was performed on assay mixtures that had incubated for 5 min or 1 h, and there was no difference in the degrees of quenching, indicating that longer interaction did not promote phagocytosis. To confirm this finding, experiments in which PMN were treated with cytochalasin B (5 μg/ml) were performed. There was no decline in the PMN association with type III GBS-FITC, indicating that phagocytosis was not promoted as a consequence of the interaction (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Type III GBS is bound to but not ingested by PMN. (A) PMN (106) were incubated with heat-killed type III GBS-FITC (107 CFU), and MFI of participating PMN is shown. Crystal violet at a final concentration of 0.25 g/liter was added to quench extracellular fluorescence, and the reaction mixture was reanalyzed by flow cytometry to determine the effect on the MFI of participating PMN. The graph represents the mean ± SEM of three experiments. (B) Representative histograms showing the shift of the PMN MFI after the addition of crystal violet. The left histogram depicts the MFI of the gated PMN alone. The middle histogram shows the increase in MFI of participating PMN after incubation with type III GBS-FITC. The shift in the MFI of the PMN back to approximately baseline after the addition of crystal violet is shown in the right histogram.

Evaluation of the receptor and ligand for this interaction.

To investigate the role of the complement receptors known to mediate attachment and ingestion of opsonized GBS as potential binding foci, we utilized MAb known to have affinity for these sites and to have functionally inhibitory properties. The anti-CR1 MAb E11 had no inhibitory effect on binding. Two MAb were used to evaluate the possible use of different binding epitopes within the CR3 I domain and thus the existence of different blocking abilities depending on the ligand (43). Clone 44 and clone LM 2/1 used at saturating concentrations did not block the binding of type III GBS-FITC to PMN. To determine whether type III GBS bound to the lectin site of CR3, PMN were treated with MAb OKM1, known to bind this site (33, 43); there was no inhibitory effect on binding. In addition, MAb to the common β chain, CD 18, clone TS 1/18, did not inhibit binding (data not shown). Taken together, these experiments indicated that the CRs important for attachment and ingestion of opsonized type III GBS do not mediate nonopsonic binding.

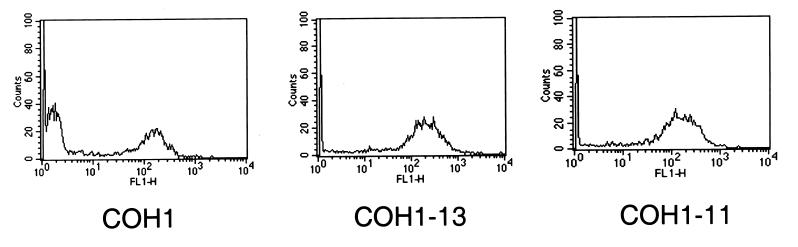

Both the CPS-deficient strain COH1-13 and the capsular sialic acid-deficient strain COH1-11 exhibited increased PMN association of 71% ± 3% and 70% ± 4%, respectively, participating at a PMN-to-bacterium ratio of 1:10, compared with 43% ± 1% for strain COH1 (P ≤ 0.02 for either mutant strain versus COH1) (Fig. 5). In addition, FACS analysis demonstrated no difference in the degree of FITC labeling of the mutants compared with that of the parent GBS strain. This finding is consistent with the concept that an increase in the binding and phagocytosis of encapsulated pathogens may occur when surface charges are altered or possible ligands are exposed (26, 49) and with previous reports indicating that CPS of type III GBS may contribute to the organism's ability to evade host defense mechanisms (30).

FIG. 5.

Role of type III GBS CPS in nonopsonic binding. PMN (106) were incubated with heat-killed type III GBS-FITC using the encapsulated strain COH1 (107 CFU) or with strain COH1-13 (107 CFU), which lacks CPS, and strain COH1-11 (107 CFU), which lacks the terminal sialic acid of CPS, and were analyzed by FACS. The histograms are representative of the 44% ± 1% of PMN binding to COH1 at a PMN-to-GBS ratio of 1:10. Both COH1-13 and COH1-11 showed increased binding to PMN, with 71% ± 3% and 70% ± 4%, respectively, of gated PMN participating in the interaction at the same ratio (mean ± SEM of three experiments; P ≤ 0.02 for either mutant strain versus COH1).

To determine if this interaction was saturable, parallel experiments in which heat-killed, unlabeled type III GBS were allowed to compete with type III GBS-FITC were conducted and the extent to which the association was inhibited was determined by FACS analysis. Type III GBS, strain COH1, at a concentration of 107 CFU produced only 7% ± 1% inhibition of PMN binding to type III GBS-FITC. When the unlabeled type III GBS was used at a concentration of 108 CFU, the degree of inhibition increased to 25% ± 1%.

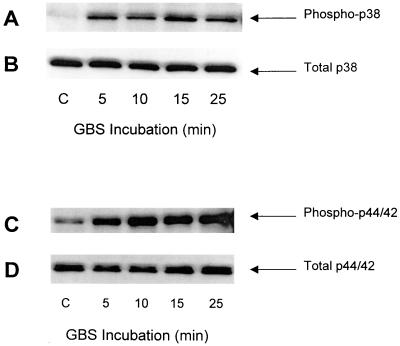

Nonopsonic binding activates PMN MAP kinases p38 and p44/42.

PMN (107/ml) were incubated with type III GBS strain COH1 (108 CFU/ml) in a serum-free system for the time intervals indicated in Fig. 6. The activation of PMN MAP kinases was evaluated by using Western blotting to detect the induced protein phosphorylation. As shown in Fig. 6A, cellular p38 MAP kinase became phosphorylated and hence activated. This activation in response to type III GBS occurred within 5 min, peaked at 15 min, and began to decline by 25 min. This time course is consistent with observations pertaining to other activators of the MAP kinase pathways (19, 24). Cellular p44/42 MAP kinase also was activated by the incubation of PMN with type III GBS in a serum-free environment (Fig. 6C). Figure 6B and D are representative of the total p38 and p44/42 MAP kinases and show that the effects observed for the induced phosphorylation of these MAP kinases were not the result of differences in loading or protein digestion.

FIG. 6.

Activation of p38 and p44/42 MAP kinases in human PMN. PMN (107/ml) were incubated with heat-killed type III GBS (108 CFU/ml) for the time intervals indicated at 37°C. Cellular proteins were separated by SDS–10 or 12% PAGE. Western blotting was performed using antibodies specific for phosphorylated p38 (A) and p44/42 (C) MAP kinases and total p38 (B) and p44/42 (D), as described in Materials and Methods. These results are representative of three similar experiments.

Lack of PMN oxidative burst in response to unopsonized type III GBS.

Incubation of unopsonized type III GBS with PMN did not trigger the oxidative burst. PMN chemiluminescence was not enhanced as a result of this interaction and was no different than that for unstimulated PMN. In addition, it was found by using the DCFH and HE methods to detect H2O2 and O2− that type III GBS-stimulated PMN were similar in response to unstimulated PMN. In contrast, PMA-stimulated PMN exhibited a potent response, with increases in their green and red fluorescence detected by the DCFH or HE methods, respectively (data not shown). Thus, unopsonized type III GBS did not trigger the PMN oxidative burst.

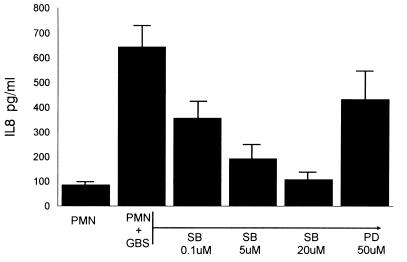

Induction of IL-8 by type III GBS.

Figure 7 shows the IL-8 release by PMN induced by type III GBS following 24 h of incubation. To determine the role of the p38 and p44/42 MAP kinases in mediating this response, the effects of specific inhibitors on the release of IL-8 were evaluated. The p38 inhibitor SB203580 blocked the release of IL-8 in a dose-response manner. However, the p44/42 inhibitor PD98059 at the maximal reported effective concentration (50 μM) only minimally blocked the release of IL-8 (7). This indicates that the p38 MAP kinase and not p44/42 mediates the observed IL-8 release in response to unopsonized type III GBS.

FIG. 7.

Effect of MAP kinase inhibitors on PMN IL-8 production. PMN (107/ml) were treated with the concentrations specified of SB203580 (SB) or PD98059 (PD) for 30 min. They were then incubated with heat-killed type III GBS (108 CFU/ml) for 24 h. The supernatant was separated from the cells, and the amount of IL-8 produced was determined by ELISA.

DISCUSSION

We have investigated the potential of type III GBS to bind nonopsonically to human PMN and have found that this does occur and that it results in the activation of intracellular signaling pathways that are known to mediate PMN inflammatory functions. Nonopsonic interactions between host phagocytic cells and invading microorganisms are recognized increasingly as an important arm of host defense (27) and have been shown to trigger cytokine release, superoxide generation, receptor upregulation, phagocytosis, and killing (16, 17, 27, 32, 46). With immune systems characterized by a very low level of type III GBS CPS-specific antibody and limited complement-mediated opsonization (8, 10), newborn infants are deficient in their capacity to mount an adequate immune response. Thus, nonopsonic interactions may be an important arm of innate immunity that could serve as a means of early defense against invasion. In the context of diminished neonatal alveolar macrophage response and delayed PMN chemotaxis, nonopsonic activation of PMN may contribute to prevention of the resultant sepsis syndrome associated with overwhelming type III GBS infection (22).

We observed a rapid and stable binding between PMN and heat-killed type III GBS that was inoculum dependent. The rapid occurrence and stability of the interaction are similar to those reported by Mork and Hancock (23) for the association of P. aeruginosa with macrophage cell lines in an opsonin-free environment. Although the binding of PMN to nonopsonized type III GBS was less efficient than PMN binding to opsonized type III GBS, it nonetheless resulted in the activation of PMN and release of IL-8, which are important host immune responses.

Phagocytosis by PMN of type III GBS did not occur over 1 h, as evidenced by the unaltered degree of association and by the equal extents of external quenching at 5 min and 1 h. Others (2, 48) have reported that nonopsonic association does result in phagocytosis but under different experimental conditions and employing different cell lines. More importantly, the nonopsonic binding of pathogens to host phagocytic cells may not always result in phagocytosis but still may serve an important role in the immune response. Vandenbrouke-Grauls et al. (46) found that the uptake of unopsonized Staphylococcus aureus by PMN proceeded at a slower rate than that for opsonized organisms but that the ability of unopsonized organisms to induce superoxide release was equal to that of opsonized organisms. Levels of nonopsonic recognition, attachment, and stimulation for ingested and adherent pathogen may be comparable (27). Öhman et al. (28) described the equal abilities of ingested and adherent type 1 fimbriated E. coli to trigger the release of reactive oxidative metabolites and lysosomal enzymes from human PMN. Mycobacterium avium was shown to bind nonopsonically to macrophages via the integrin αvβ3, resulting in enhanced expression of CR3 (16). Similarly, binding of the minor fimbrial subunit of Bordetella pertussis to the integrin VLA-5 resulted in the activation of CR3 and enhanced binding to B. pertussis via filamentous hemagglutinin (17). Thus, the binding of pathogens to phagocytic cell receptors without phagocytosis may initiate the inflammatory response or facilitate later ingestion (48).

The CPS of type III GBS is a virulence factor enabling it to avoid host defense mechanisms (30). Changes in surface characteristics of polysaccharides of microorganisms may alter the surface charge and thus render them more susceptible to phagocytosis (49). The binding of type III GBS transposon mutant strains lacking CPS or its terminal monosaccharide, sialic acid, was enhanced. Thus, the CPS may act as a barrier or cloak that prevents phagocytic cells from reaching binding ligands. Furthermore, type III CPS itself was not the ligand for this interaction. This finding is in accord with the results of Vallejo et al. and Williams et al. (44, 45, 50), who demonstrated that encapsulated and unencapsulated strains of type III GBS were comparable in their abilities to elicit TNF-α and IL-6 from monocytes. There are other data from piglet pneumonia and meningitis models to indicate that capsule mutant strains of type III GBS induce a more potent inflammatory response than do encapsulated strains (21, 30). This is consistent with the prevailing concept that cell wall peptidoglycan and perhaps GBS polysaccharide are greater stimulators of cytokine release than are lipoteichoic acid or type-specific CPS. Lack of capsule leading to increased attachment of GBS is not limited to PMN, as this also has been demonstrated with other cell lines such as respiratory epithelial cells (18). Thus, the concept of increased accessibility of bacterial proteins to eukaryotic cell receptors is probably a generalized one.

Since CR1 and CR3 are important for opsonophagocytosis of type III GBS and for nonopsonic phagocytosis of other pathogens, it seemed prudent to study them as potential binding ligands (12, 39). Antal et al. (2) investigated the nonopsonic association of type III GBS with the macrophage-like cell line PU5-1.8 and with mouse peritoneal macrophages and documented CR3-mediated phagocytosis. The percent phagocytosis observed varied from 20 to 50% over a 3-h incubation. It is of interest that type III GBS is avirulent in mice since murine phagocytes clear this microorganism in the absence of antibody or complement (48). Gbarah et al. (12) have defined CD11 and CD18 as receptors for type 1-fimbriated E. coli. CR3 also has a role in the nonopsonic recognition of mycobacteria by macrophage cell lines (35). However, CR1 and CR3 do not appear to be receptors for the observed interaction between type III GBS and PMN since MAb against these sites did not inhibit the association. Speert et al. (40) postulated different leukocyte receptors for nonopsonic and opsonic phagocytosis of P. aeruginosa. Interestingly, Antal et al. (2) noted that nonopsonic phagocytosis of GBS by the cell lines utilized was incompletely blocked by MAb against CR3, hinting that there are other sites of nonopsonic interaction.

Unlabeled, heat-killed type III GBS partially inhibited PMN binding to FITC-labeled type III GBS. It is possible that this interaction is nonsaturable, implying a nonspecific type of interaction that is still capable of triggering the innate immune response. An alternative explanation is that these gram-positive organisms tend to bind with each other and then bind PMN in chains, a phenomenon that we observed by direct microscopy. Thus, FITC-labeled type III GBS may actually be binding to unlabeled type III GBS already bound to the surface of the PMN.

Nonopsonic binding of type III GBS resulted in phosphorylation and activation of p38 MAP kinase as well as p44/42 MAP kinase. These MAP kinases have an essential role in PMN intracellular signaling pathways in response to various external stimuli and environmental stresses (15, 31, 55). The p38 MAP kinase pathway is responsible for PMN superoxide generation, chemotaxis, and IL-8 production in response to TNF-α and FMLP, and the activation of MAP kinase pathways generally results in activation of transcription factors which regulate protein synthesis (36, 55). The p38 MAP kinase pathway is involved in PMN apoptosis and gene expression (11, 55). Activation of p38 MAP kinase mediates the upregulation of CD11b and is required for PMN-mediated killing of S. aureus (36). The MAP kinase p44/42 also has a role in PMN enzyme release and phagocytosis (7, 19). While type III GBS activated both p38 and p44/42 MAP kinases, only p38 MAP kinase mediated IL-8 release from PMN, as documented by the ability of the p38 MAP kinase-specific inhibitor SB203580 to inhibit IL-8 release while the p44/42 MAP kinase inhibitor had a minimal effect. Our results are consistent with those of Zu et al. (55), who noted that FMLP activates both p38 and p44/42 MAP kinases but that only p38 MAP kinase was required for PMN chemotaxis and superoxide generation. In contrast, lipopolysaccharide as a stimulus results in phosphorylation and activation of p38 MAP kinase and not p44/42 MAP kinase, with a maximum response at 20 to 25 min. However, like type III GBS, it does not result in superoxide generation (24). The time to peak stimulation is consistent with our data, but type III GBS activated both MAP kinases. Thus, multiple signaling pathways are involved in regulating PMN responses, and the p38 MAP kinase may play different roles in mediating PMN function in response to distinctive stimuli (24, 36, 51, 55). The effect of PMN activation by type III GBS was the release of IL-8. This is an important immune response since IL-8 promotes the attraction of additional PMN to the site of invasion, primes PMN for the respiratory burst, and is representative of an array of proinflammatory cytokines activated by NF-κB which could contribute to host defense and sepsis symptomatology (55).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that type III GBS binds nonopsonically to human PMN. This interaction occurs rapidly and in an inoculum-dependent manner. The binding is stable and does not stimulate phagocytosis. It does not require the complement receptors used for attachment and ingestion of opsonized GBS. This interaction resulted in the activation of the cellular p38 and p44/42 MAP kinases and the p38-mediated release of the potent chemotactic cytokine IL-8. We propose that this interaction, acting as an arm of innate immunity, serves as a first line of defense in the nonimmune host. This may be particularly important in the populations most affected by GBS, such as newborn infants, the elderly, and the immunocompromised, in whom nonopsonic binding may initiate the immune response and promote clearance of organisms before infection is well established. Further definition of these mechanisms may provide insights into alternative therapeutic modalities, such as antiadhesion therapy and use of inhibitors of the MAP kinases as inflammatory modulators (36, 46, 54).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by Contract NO1-A175326 (E.A.A., M.S.E.) and by grant R01-AI19031 (C.W.S.) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

We thank R. Nelson Bennett for his technical assistance with FACS analysis and Carol J. Baker for her critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson C L, Shen L, Eicher D M, Wewers M D, Gill J K. Phagocytosis mediated by three distinct Fcγ receptor classes on human leukocytes. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1333–1345. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.4.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antal J M, Cunningham J V, Goodrum K J. Opsonin-independent phagocytosis of group B streptococci: role of complement receptor type three. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1114–1121. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1114-1121.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker, C. J., and M. S. Edwards. Group B streptococcal infections. In J. S. Remington and J. O. Klein (ed.), Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant, 5th ed., in press. The W. B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia, Pa.

- 4.Cantinieaux B, Hariga C, Courtoy J, Hupin J, Fondu P. Staphylococcus aureus phagocytosis. A new cytofluorometric method using FITC and paraformaldehyde. J Immunol Methods. 1989;121:203–208. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen M S. Molecular events in the activation of human neutrophils for microbial killing. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18(Suppl. 2):S170–S179. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.supplement_2.s170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong Z M, Murphy J W. Cryptococcal polysaccharides bind to CD18 on human neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1997;65:557–563. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.557-563.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Downey G P, Butler J R, Tapper H, Fialkow L, Saltiel A R, Rubin B B, Grinstein S. Importance of MEK in neutrophil microbicidal responsiveness. J Immunol. 1998;160:434–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards M S, Nicholson-Weller A, Baker C J, Kasper D L. The role of specific antibody in alternative complement pathway-mediated opsonophagocytosis of type III, group B Streptococcus. J Exp Med. 1980;151:1275–1287. doi: 10.1084/jem.151.5.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards M S, Baker C J, Kasper D L. Opsonic specificity of human antibody to the type III polysaccharide of group B Streptococcus. J Infect Dis. 1979;140:1004–1008. doi: 10.1093/infdis/140.6.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrieri P. Neonatal susceptibility and immunity to major bacterial pathogens. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12(Suppl. 4):S394–S400. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.supplement_4.s394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frasch S C, Nick J A, Fadock V A, Bratton D L, Worthen G S, Henson P M. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent and -independent intracellular signal transduction pathways leading to apoptosis in human neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8389–8397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gbarah A, Gahmberg C G, Ofek I, Jacobi U, Sharon N. Identification of the leukocyte adhesion molecules CD11 and CD18 as receptors for the type 1-fimbriated (mannose-specific) Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4524–4530. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4524-4530.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goetz M B, Kuriyama S M, Silverblatt F T. Phagolysosome formation by polymorphonuclear neutrophilic leukocytes after ingestion of Escherichia coli that express type 1 pili. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:229–233. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.1.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gotoff S P, Boyer K M. Cellular and humoral aspects of host defense mechanisms against GBS. Antibiot Chemother (Basel) 1985;35:142–156. doi: 10.1159/000410369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han J, Lee J-D, Bibbs L, Ulevitch R J. A MAP kinase targeted by endotoxin and hyperosmolarity in mammalian cells. Science. 1994;265:808–811. doi: 10.1126/science.7914033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayashi T, Rao S P, Catanzaro A. Binding of the 68-kilodalton protein of Mycobacterium avium to αvβ3 on human monocyte-derived macrophages enhances complement receptor type 3 expression. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1211–1216. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1211-1216.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hazenbos W L W, van den Berg B M, Geuijen C W, Mooi F R, van Furth R. Binding of FimD on Bordetella pertussis to very late antigen-5 on monocytes activates complement receptor type 3 via protein tyrosine kinases. J Immunol. 1995;155:3972–3978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hulse M L, Smith S, Chi E Y, Rubens C E. Effect of type III group B streptococcal capsular polysaccharide on invasion of respiratory epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4835–4841. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4835-4841.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Junger W G, Hoyt D B, Davis R E, Herdon-Remelius C, Namiki S, Junger H, Loomis W, Altman A. Hypertonicity regulates the function of human neutrophils by modulating chemoattractant receptor signaling and activating mitogen-activated protein kinase p38. J Clin Investig. 1998;101:2768–2779. doi: 10.1172/JCI1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim K S, Wass C A, Hong J K, Concepcion N F, Anthony B F. Demonstration of opsonic and protective activity of human cord sera against type III group B streptococcus that are independent of type-specific antibody. Pediatr Res. 1988;24:628–632. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198811000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ling E W Y, Noya F J D, Ricard G, Beharry K, Mills E L, Aranda J V. Biochemical mediators of meningeal inflammatory response to group B streptococcus in the newborn piglet model. Pediatr Res. 1995;38:981–987. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199512000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin T R, Rubens C E, Wilson C B. Lung antibacterial defense mechanisms in infant and adult rats: implications for the pathogenesis of group B streptococcal infections in the neonatal lung. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:91–100. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mork T, Hancock R E W. Mechanisms of nonopsonic phagocytosis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3287–3293. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3287-3293.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nick J A, Avdi N J, Gerwins P, Johnson G L, Worthen G S. Activation of a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in human neutrophils by lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1996;156:4867–4875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noya F J D, Baker C J, Edwards M S. Neutrophil Fc receptor participation in phagocytosis of type III group B streptococci. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1415–1420. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1415-1420.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ofek I, Doyle R J. Interaction of bacteria with phagocytic cells. In: Ofek I, Doyle R J, editors. Bacterial adhesion to cells and tissue. London, United Kingdom: Chapman & Hall; 1994. pp. 171–194. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ofek I, Goldhar J, Keisari Y. Nonopsonic phagocytosis of microorganisms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:239–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.001323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Öhman L, Hed J, Stendahl O. Interaction between human polymorphonuclear leukocytes and two different strains of type 1 fimbriae-bearing Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1982;146:751–757. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perticarari S, Presani G, Mangiarotti M A, Banfi E. Simultaneous flow cytometric method to measure phagocytosis and oxidative products by neutrophils. Cytometry. 1991;12:687–693. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990120713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Philips J B, Li J-X, Gray B M, Pritchard D G, Oliver J R. Role of capsule in pulmonary hypertension induced by group B streptococcus. Pediatr Res. 1992;31:386–390. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199204000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raingeaud J, Whitmarsh A J, Barrett T, Derijard B, Davis R J. MKK3- and MKK6-regulated gene expression is mediated by the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1247–1255. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rautelin H, Blomberg B, Jarnerot G, Danielsson D. Nonopsonic activation of neutrophils and cytokine production by Helicobacter pylori: ulcerogenic markers. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:128–132. doi: 10.3109/00365529409090450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rowen J L, Smith C W, Edwards M S. Group B streptococci elicit leukotriene B4 and interleukin-8 from human monocytes: neonates exhibit a diminished response. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:420–426. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubens C E, Kupers J M, Heggen L M, Kasper D L, Wessels M R. Molecular analysis of the group B streptococcal capsule genes. In: Dunny G M, Cleary P P, McKay L L, editors. Genetics and molecular biology of streptococci, lactococci, and enterococci. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1991. pp. 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlesinger L S, Hull S R, Kaufman T M. Binding of the terminal mannosyl units of lipoarabinomannan from virulent strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to human macrophages. J Immunol. 1994;152:4070–4079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schnyder B, Meunier P C, Car B D. Inhibition of kinases impairs neutrophil activation and killing of Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem J. 1998;331:489–495. doi: 10.1042/bj3310489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schuchat A. Epidemiology of group B streptococcal disease in the United States: shifting paradigms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:497–513. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sehgal G, Zhang K, Todd III R F, Boxer L A, Petty H R. Lectin-like inhibition of immune complex receptor-mediated stimulation of neutrophils. J Immunol. 1993;150:4571–4580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith C L, Baker C J, Anderson D C, Edwards M S. Role of complement receptors in opsonophagocytosis of group B streptococci by adult and neonatal neutrophils. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:489–495. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.2.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Speert D P, Eftekhar F, Puterman M L. Nonopsonic phagocytosis of strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from cystic fibrosis patients. Infect Immun. 1984;43:1006–1011. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.3.1006-1011.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stark J M, Godding V, Sedgwick J B, Busse W W. Respiratory syncytial virus infection enhances neutrophil and eosinophil adhesion to cultured respiratory epithelial cells. Roles of CD18 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1. J Immunol. 1996;156:4774–4782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stokes R W, Thorson L M, Speert D P. Nonopsonic and opsonic association of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with resident alveolar macrophages is inefficient. J Immunol. 1998;160:5514–5521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thornton B P, Vetvicka V, Pitman M, Goldman R C, Ross G D. Analysis of the sugar specificity and molecular location of the β-glucan-binding lectin site of complement receptor type 3 (CD11b/CD18) J Immunol. 1996;156:1235–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vallejo J G, Baker C J, Edwards M S. Interleukin-6 production by human neonatal monocytes stimulated by type III group B streptococci. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:332–337. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vallejo J G, Baker C J, Edwards M S. Roles of the bacterial cell wall and capsule in induction of tumor necrosis factor alpha by type III group B streptococci. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5042–5046. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5042-5046.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vandenbrouke-Grauls C M J E, Thijssen H M W M, Verhoef J. Interaction between human polymorphonuclear leukocytes and Staphylococcus aureus in the presence and absence of opsonins. Immunology. 1984;52:427–435. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Hunolstein C, Totolian A, Alfarone G, Mancuso G, Cusumano V, Teti G, Orefici G. Soluble antigens from group B streptococci induce cytokine production in human blood cultures. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4017–4021. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4017-4021.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wennerstrom D E, Schutt R W. Adult mice as a model for early onset group B streptococcal disease. Infect Immun. 1978;19:741–744. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.2.741-744.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams P, Lambert P A, Haigh C G, Brown M R W. The influence of the O and K antigens of Klebsiella aerogenes on surface hydrophobicity and susceptibility to phagocytosis and antimicrobial agents. J Med Microbiol. 1986;21:125–132. doi: 10.1099/00222615-21-2-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams P A, Bohnsack J F, Augustine N H, Drummond W K, Rubens C E, Hill H R. Production of tumor necrosis factor by human cells in vitro and in vivo, induced by group B streptococci. J Pediatr. 1993;123:292–300. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81706-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xia Z, Dickens M, Raingeaud J, Davis R J, Greenberg M E. Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science. 1995;270:1326–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zaffran Y, Zhang L, Ellner J J. Role of CR4 in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-human macrophages binding and signal transduction in the absence of serum. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4541–4544. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4541-4544.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou M, Todd III R F, van de Winkel J G J, Petty H R. Cocapping of the leukoadhesion molecules complement receptor type 3 and lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 with Fcγ receptor III on human neutrophils. J Immunol. 1993;150:3030–3041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zopf D, Simon P, Barthelson R, Cundell D, Idanpaan-Heikkila I, Tuomanen E. Development of anti-adhesion carbohydrate drugs for clinical use. In: Kahane I, Ofek I, editors. Toward anti-adhesion therapy for microbial diseases. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1996. pp. 35–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zu Y-L, Qi J, Gilchrist A, Fernandez G A, Vazquez-Abad D, Kreutzer D L, Huang C-K, Sha'afi R I. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation is required for human neutrophil function triggered by TNF-α or FMLP stimulation. J Immunol. 1998;160:1982–1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]