Abstract

While many researchers suggest that relational conflict has adverse performance effects in family firms, the exact mechanisms through which conflict harms performance are rarely empirically investigated. This paper explores the role of family social capital in the relationship between relational conflict and family firm performance. We hypothesize that the negative relationship between relational conflict and family firm performance is partially mediated by family social capital, while family ownership moderates the relationship between relational conflict and family social capital. In a sample of 175 U.S.-based small and medium-sized family firms recruited through Prolific Academic, we find that relational conflict harms firm performance indirectly through the erosion of family social capital. However, no evidence of a direct negative effect of relational conflict on performance is found. Our results also indicate that the negative relationship between relational conflict and family social capital is intensified by family ownership. We discuss the implications and contributions and present relevant directions for future research.

Keywords: Relational conflict Family social capital Family ownership Family firm performance

Introduction

Because of the family and business overlap in family firms, family businesses are said to be “plagued by conflicts” (Levinson, 1971). Interpersonal conflicts in family firms have attracted the attention of professionals and scholars since the emergence of family business research. Most often, they are perceived as a dysfunctional phenomenon that harms the family and the firm (Kubíček & Machek, 2020). The psychology literature distinguishes multiple types of conflict. Disagreements about tasks or problems at hand, referred to as substantive or cognitive conflicts, can benefit firm performance as they allow for increased understanding of the tasks and initiate the exchange of ideas and opinions (Jehn, 1995). However, personal and emotional conflicts, known as affective or relational conflicts, do not seem to have any benefits related to performance (De Dreu & Weingart, 2003). The family business literature corroborates these results (Eddleston & Kellermanns, 2007; Ensley et al., 2007; Nosé et al., 2017), finding that relational conflict is detrimental to family firm performance. Nevertheless, the exact mechanisms of how relational conflict harms family firm performance are rarely empirically evaluated.

To understand the adverse effects of relational conflict in family firms, it is critical to discuss the factors that make family firms different from their nonfamily counterparts. One of these factors is the presence of family ties in the business. Compared to other organizational forms of business, these ties are considered stronger, more intense, and more long-lasting (Hoffman et al., 2006). Consequently, a substantial body of family business literature concentrated on the uniqueness of family ties and their potential to create competitive advantage (Arregle et al., 2007; Hoffman et al., 2006; Pearson et al., 2008). Broadly, the wealth embedded in and engendered by social ties is referred to as social capital (Adler & Kwon, 2002). The academic literature presents several categorizations of social capital. First, social capital can refer to internal (bonding) social ties, which connect people inside a social group or organization, and external (bridging) social ties related to outside networks of contacts (Putnam, 2000). Social capital is a multidimensional construct, having a structural dimension (represented by closure, density, and connectivity of social ties), relational dimension (trust, norms, and obligations), and cognitive dimension (shared representations and meanings;Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). In the unique context of family firms, social capital takes a particular form because of the temporal stability, interrelatedness, and closure of family ties (Pearson et al., 2008). The internal social capital in family firms is referred to as family social capital (Arregle et al., 2007). Like organizational social capital, family social capital is assumed to be composed of its structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions (Carr et al., 2011; Herrero & Hughes, 2019). However, it has several unique attributes: it is hardly imitable by nonfamily firms (Herrero, 2018), it is transferred and inherited during the succession process (Aragón‑Amonarriz et al., 2019), and it takes longer to develop (Arregle et al., 2007).

Apart from family social capital, another distinguishing feature of family firms is their pursuit of family-centred goals, which is theoretically explained by their propensity to protect and build their socioemotional wealth (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). Socioemotional wealth (SEW) can be defined as the non-economic utility derived from ownership and involvement in the family firm (Martin & Gómez-Mejía, 2016). The extent to which family firms emphasise family-centred goals varies. While family firms need to maintain family involvement to be considered “family firms” (Chrisman et al., 2012), the degree to which they do so can vary from complete family control to “enough but not too much” (Stewart & Hitt, 2012). In other words, some family firms are “pure family firms”, while others are more similar to nonfamily businesses. Thus, family firms display vast within-group differences, and recent family business literature calls for further investigation of their heterogeneity (Daspit et al., 2021; Haynes et al., 2021). One factor that creates this heterogeneity is the concentration of firm ownership in family hands. Family ownership has important consequences related to family firms’ behaviors as the firm’s actions are driven by utilities derived by dominant family owners (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011). For instance, high family ownership “leads to an emphasis on particular types of stakeholders and a particular type of socially oriented behavior” (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011, p. 681), making family firms responsive to environmental concerns (Berrone et al., 2010). Family ownership gives family members greater power to influence a firm’s strategy and decisions, providing the firm with the ability to behave in a way that is distinctively supportive of the family (Evert et al., 2018). When family ownership is high, the financial and socioemotional wealth of family members is at stake, making family firms take actions that are risk-averse and focused on SEW preservation (Evert et al., 2018). Although family ownership is not directly linked to family firm performance (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011), in the context of relational conflicts in family firms, it becomes an important factor to study. Under normal circumstances, family ownership produces emotional attachment and leads to family-firm identification and seeing the firm as “our business” (Kotlar et al., 2020). However, relational conflicts are associated with socioemotional costs (Rousseau et al., 2018), and under high emotional attachment and family-firm identification of family members, they can be even more detrimental.

To shed more light on how relational conflict harms family performance, the current study investigates how relational conflict affects family firms’ performance and their family social capital, as well as the role of family ownership in these relationships. The rest of this paper proceeds as follows. First, we present the relevant theoretical background and develop the hypotheses. Second, we discuss the sampling and data analysis methods. Subsequently, we present and discuss the results. Finally, we provide concluding remarks.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Relational Conflict and Family firm Performance

There is a consensus in the intragroup conflict literature that relational conflict has the potential to have direct adverse effects on the performance of social groups. Relational conflict produces negative feelings such as anxiety and fear, severely affecting individuals. Jehn (1995) found that relational conflict reduces group members’ satisfaction and willingness to remain in the social group. The negative feelings associated with relational conflict also reduce group members’ cognitive functioning and ability to process information (Jehn, 1995) and inhibit their creative thinking (Carnevale & Probst, 1998). Instead of focusing on tasks that must be accomplished, group members spend their time and energy resolving (or trying to ignore) the conflicts (Jehn & Mannix, 2001). De Dreu and Weingart’s (2003) meta-analysis revealed that relational conflict is indeed negatively associated with individuals’ satisfaction and team performance. The findings are supported in the context of family firms, where relational conflict produces animosity, stress, hostile behaviours, and insufficient attention devoted to family business needs (Eddleston & Kellermanns, 2007). Thus, like previous authors, we expect that:

Hypothesis 1

There is a negative relationship between relational conflict and family firm performance.

Family Social Capital and Family firm Performance

In their seminal paper, Pearson et al. (2008) discuss family firms’ unique resources and capabilities caused by family members’ involvement and interactions and posit that “familiness”, or family social capital (Arregle et al., 2007), is composed of structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions, just as organizational social capital. It should be noted that family social capital is most often considered to be an “internal”, bonding type of social capital (“strong ties”), and our discussion will therefore not focus on bridging social capital (“weak ties”). The entrepreneurship literature does not present a consensus on whether internal social capital is always beneficial for firms. On the one hand, due to close relationships, trust, and shared vision, social capital creates the potential for solidarity and collaboration, making people in a firm more attentive to the firm’s goals (Adler & Kwon, 2002). When internal social capital is strong, employees are willing to subordinate their individual goals and actions to collective goals and actions (Leana & Van Buren, 1999). Sharing of information, which results in richer information for decision-making, and a shared understanding of roles also increase the quality of decision-making (Mustakallio et al., 2002). Thus, internal social capital has the potential to contribute to firm performance. On the other hand, some authors argue that social capital also has its “dark side” (Gargiulo & Benassi, 1999). Excessive internal social capital can lead to group-thinking, rigidity, or inability to access novel ideas and resources (Stam et al., 2014). For instance, excessive trust can lead to an overreliance on close contacts and their networks, thus restricting the ability to find, evaluate and exploit opportunities (Shi et al., 2015). Thus, excessive internal social capital can limit growth opportunities.

Arregle et al. (2007) and Pearson et al. (2008) assume that family social capital presents a competitive advantage vis-à-vis nonfamily firms. In the family business setting, one of the rare studies suggesting evidence of “dark side” of family social capital was presented by Herrero and Hughes (2019). In their study, social capital’s relational and cognitive dimensions contribute to performance, but the structural dimension displays an inverse U-shaped relationship with performance. Apart from Herrero and Hughes’s (2019) study, the family business literature is relatively unanimous regarding the positive effects of family social capital on performance (e.g., Duarte Alonso et al., 2020). Family social capital has been found to improve firm performance by enhancing knowledge integration (Kansikas & Murphy, 2011), knowledge internalization and product development (Chirico & Salvato, 2016), innovation (Sanchez-Famoso et al., 2019), fostering social cohesion and work climate (Ruiz Jiménez et al., 2013), improving family firm resilience during difficult times (Wiatt et al., 2020), and creating strong bonds with the community (Duarte Alonso et al., 2020). As all the above factors can be drivers of firm performance, then, we also expect that:

Hypothesis 2

There is a positive relationship between family social capital and family firm performance.

Relational Conflict and Family Social Capital

Family studies suggest that family members who experience conflict with other family members tend to avoid mutual interactions. For instance, adolescents avoid interaction with parents if they observe hostile, impulsive and inconsistent family conflict (Cooper, 1988) or have a bad conflict experience (Noller et al., 2006). When marital conflict is present in the family, parents tend to devote less engagement to the parent-child relationship and become less attentive, thus reducing their interactions with children (Buehler & Gerard, 2002). Conflicts between siblings are characterized by a lack of active conflict resolution efforts; often, siblings simply ignore each other, which can have long-term consequences (Vandell & Bailey, 1992). In extremely conflicted families, family ties can be broken when, for instance, an adolescent is told to leave or a family member proposes divorce (Aldridge, 1984). Hence, relational conflict has the potential to harm social interactions among family members, weaken family ties and their connectivity, thus harming the essential components of the structural dimension of social capital. Moreover, relational conflict can also affect “appropriable organization” (Coleman, 1988). Family members involved in conflict tend to perpetuate the toxic behaviours in their peer- or nonfamily social groups. For example, adolescents adopt their parents’ hostility and adverse conflict behaviours (Taylor & Segrin, 2010). Children’s direct exposure to parental conflicts increases the likelihood of imitating parents’ conflict behaviours in relationships with nonfamily members (Buehler et al. 2009). Thus, family conflict can permeate the whole organization (Barach & Ganitsky, 1995), reducing the ability to use and reuse family ties (Pearson et al., 2008) in the family-firm context. In sum, relational conflict can be expected to harm the structural dimension of family social capital.

The emotionality of relational conflict also seems to affect the relational dimension of social capital, i.e., trust, norms, obligations, and identification. Broadly, trust is developed through perceived trustworthiness and affect (Williams, 2001). Perceived trustworthiness is a cognitive determinant of trust related to perceived abilities, benevolence, and integrity (Mayer & Davis, 1999). On the other hand, positive affect, i.e. positive emotions and moods, is one of the predictors of affective (“deep”) trust. Negative affect produced by relational conflict signals the presence of a threatening environment, thus creating negative feelings and perceptions of other people involved in the conflict (Lu et al., 2017). These feelings and perceptions, in turn, determine how an individual’s trust develops over time (Williams, 2001). Through emotional contagion, individuals’ negative emotions can spread throughout the social group, leading to a low level of trust in the whole group (Fulmer & Gelfand, 2012). The psychology literature presents similar findings for identification, suggesting that an individual’s identification with the group decreases with negative emotions such as anger (Kessler & Hollbach, 2005). Thus, by virtue of negative affect, relational conflict can be assumed to hinder the relational dimension of family social capital.

Relational conflict is also likely associated with the cognitive dimension of social capital, i.e. shared vision and language. First, one of the most commonly discussed cognitive manifestations of interpersonal conflict is disagreement. Barki and Hartwick (2004) define conflict as a “process that occurs between independent parties as they experience negative emotional reactions to perceived disagreements and interference with the attainment of their goals”. Thus, it can be assumed that relational conflict reduces shared cognitions about collective goals (Knight et al., 1999). Second, relational conflict weakens social ties among family members and their social interactions. However, developing shared vision, shared language, and collective narratives among family members requires close social relations and frequent social interactions (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998; Mustakallio et al., 2002). Social interactions can only be built with a positive affective tone (Pelled & Xin, 1999); negative affect, typical for relational conflict, will hinder their development. Overall, then, it can be assumed that relational conflict harms the cognitive dimension of social capital by reducing mutual agreement, quality of relationships, and frequency of social interactions among family members.

As we have shown, psychology literature and family business literature present compelling arguments why relational conflict can harm all three dimensions of family social capital: structural, relational, and cognitive. In addition, according to the process perspective of social capital, the development of family social capital requires stability, closure, interdependence, and interactions (Pearson et al., 2008), all of which can be assumed to be negatively affected by an escalated interpersonal conflict between family members. To sum up, it can be expected that:

Hypothesis 3

There is a negative relationship between relational conflict and family social capital.

Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 constitute a partial mediation model in which relational conflict has both direct and indirect negative effects (through family social capital) on family firm performance. Consequently, taking the arguments as a whole, we expect that:

Hypothesis 4

The relationship between relational conflict and family firm performance is partially mediated by family social capital.

Moderating Effects of Family Ownership

Hypothesis 3

expects a negative relationship between relational conflict and family social capital. Presumably, in family firms, relational conflict escalates more easily and rapidly than in nonfamily firms (Frank et al., 2011). It can be expected that the differences in family-firm identification and emotional attachment among family firms will also cause differences in conflict and emotional dynamics. First, the negative affect produced by relational conflict represents a socioemotional cost (Rousseau et al., 2018). While relational conflict produces negative affect itself, ceteris paribus, in families that strongly perceive the firm as “their business”, the level of stress and negative affect can be considered to be higher because family members feel emotionally invested, and the wellbeing of the family is put at danger (Kotlar et al., 2020). Second, a possible economic and socioemotional loss can create the need to leave the situation (Rousseau et al., 2018); yet, family members face great exit barriers and cannot simply leave. These exit barriers can be assumed to be greater under high family ownership since for most owners, the loss of the firm represents a highly emotional event (Berrone et al., 2012), and thus, family ownership has high emotional value (Zellweger & Astrachan, 2008). When family ownership is high and relational conflict occurs, family members face the need to leave while being unable to leave, which results in additional strain and negative affect. Third, under normal circumstances, when a family member feels threatened, trhey are likely to approach other family members to address the threat. When relational conflict occurs in the family, the family system cannot coordinate family members to collectively protect the sense of belonging and emotional attachment created by family ownership (Kotlar et al., 2020). Family members are left “alone” in a socioemotional loss perspective, intensifying the already-existing negative affect. The intensified negative affect acts as an “exacerbator” of the conflict-outcome relationship (Adams & Laursen, 2007; Jehn & Bendersky, 2003). Finally, family firms with concentrated family ownership can be reluctant to seek help outside of the family circle due to their emotional resistance (McCann et al., 2004) and hubristic overestimation of own abilities to resolve the conflicts (Haynes et al., 2015). The negative effects of relational conflict on family social capital cannot be effectively mediated by (or be transferred to) nonfamily members who can otherwise diffuse family tensions and reduce family conflicts (Rosecká & Machek, 2021). In sum, it can be expected that high family ownership magnifies the adverse effects of relational conflict on family social capital by increasing the extent of negative affect produced by relational conflict and by virtue of lower ability to use conflict-resolution mechanisms. In other words, we posit that:

Hypothesis 5

The relationship between relational conflict and family social capital is moderated by family ownership.

The Moderated Mediation Model

The combination of the expectations of Hypotheses 4 and 5 leads to a moderated mediation model between relational conflict and family firm performance, in which family social capital acts as a mediating variable and family ownership as a moderating variable. In other words, besides harming family firm performance directly, relational conflict is expected to harm family social capital (with family ownership acting as a moderator), which, in turn, negatively affects performance. Formally, we expect that:

Hypothesis 6

The relationship between relational conflict and family firm performance is partially mediated by family social capital, with family ownership acting as a moderator of the relational conflict-family social capital relationship.

Methods

Data Collection

An online questionnaire was prepared in Qualtrics and distributed through Prolific Academic (e.g., Derfler-Rozin et al., 2021) to managers of small and medium-sized family firms in the United States. The choice of the data collection method builds on the fact that online panel data has been increasingly used in recent years (Porter et al., 2019) while providing results that converge to conventional datasets in terms of data quality (Walter et al., 2019). The survey was carried out in the first quarter of 2021 and consisted of two waves. The objective of the first wave (“prescreening”) was to recruit managers who (1) would describe their firm as a family business and (2) were members of the controlling family. Thus, in the sample, we identify family firms based on their self-perception as a family firm (Zahra, 2003). In the prescreening stage, we addressed a total of 1,700 managers, out of which 297 met our selection criteria. In the second wave, we distributed the full survey to these 297 respondents and obtained 229 complete responses. Besides firm demographic variables and constructs employed in this study (the Appendix provides a summary list of measures), we asked the respondents to briefly describe their family business. This description served as an initial check of respondents’ efforts to provide meaningful responses. We eliminated 41 observations in case we were dissatisfied with the description (e.g. the person did not seem to be a family member or provided only superficial information). The survey also contained several attention checks (e.g., “Please write below the word ‘red’). Eight respondents failed to pass the attention checks, and their responses were removed from the sample (Jackson et al., 2016). Finally, we did not admit five respondents who seemed to use virtual private servers to hide their location (Winter et al., 2019).

The final sample consists of 175 U.S. family business managers. The companies in the sample can be classified as microenterprises with 5–10 employees (27.6%), small companies with 10–49 employees (65.4%), and medium-sized companies with 50–499 employees (14.1%). The family firms are controlled by the first generation (24%), second generation (47.5%), third generation (25.1%), or fourth generation (3.4%). The majority of companies were affiliated with the services sector (50.8%), followed by manufacturing (17.1%), wholesale and retail (16%), construction (6.8%), and other industries (9.1%). Several factors complicate the assessment of sample representativeness. The descriptive data of the respondents should be compared with those of the population of U.S. family firms. Because there is no official database of such businesses, and the U.S Census does not track them (Chang et al., 2008), it is hard to know exactly what characteristics apply to this population. In addition, we are unable to draw valid comparisons between our sample and the samples of previous family business studies carried out in the US, as these studies frequently use convenience samples (Gedajlovic et al., 2012). The existing surveys of American family businesses are very diverse, too. Table 1 illustrates this diversity by showing family firms’ industry affiliation in selected surveys conducted in the US The examples include two representative family business surveys (e.g., Haynes et al., 2021), one large-sample survey conducted among SMEs in Florida, and two recent family business reports of advisory organizations.

Table 1.

Industry affiliation in the sample and in previous representative family business surveys

| Survey | Sample size | Manufacturing [%] | Construction [%] | Wholesale and retail trade [%] |

Services [%] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study | 175 | 17.1 | 6.8 | 16 | 50.8 | |

| National Family Business Survey (2000) | 708 | 7.2 | n/a | 23.4 | 48 | Construction not presented as a separate category. |

| American Family Business Survey (2003) | 1,143 | 24.5 | 12.2 | 27.7 | n/a | Wholesale and distribution represents one broader category. Services not presented as a separate category. |

| Florida Small Business Development Center (2020) | 3,633 | 12.3 | 7.6 | 13.8 | 66.3 | The figures refer to nine regions in Florida. |

| KPMG UAE Family Business Report: COVID-19 Edition (2021) | 498 | 20 | 8 | n/a | 66 | The figures refer to “Americas”, including South America and the Caribbean. Wholesale and retail not presented as a separate category. |

| Family Enterprise USA Family Business Survey (2021) | 172 | 23.5 | 6 | n/a | n/a | Wholesale not presented as a separate category. Instead, retail & consumer durables is considered. |

Notes: The frequencies for the National Family Business Survey were taken from Puryear et al. (2008)

The National Family Business Survey (NFBS) was conducted in 1997/2000. Most NFBS survey participants were microenterprises with fewer than five employees (Puryear et al., 2008). According to the U.S. Census, most American companies are indeed microenterprises—with different industrial characteristics from small and medium-sized firms—and thus NFBS could not serve as a reference survey for our study. Further, the American Family Business Survey (AFBS), conducted in 2003, presents wholesale and distribution as a broader industry category and does not present the percentage of firms operating in services. On the other hand, the generational involvement of firms surveyed in AFBS is remarkably similar to our sample (first generation = 27%, second generation = 43%, third generation = 23%). A survey among 3,633 small businesses was conducted in 2019 by Florida Small Business Development Center (SBDC). The industry affiliation of the firms in the sample is fairly similar to ours (services = 66.3%, manufacturing = 12.3%, construction = 7.6%, wholesale and retail = 13.8%). The fourth example, KPMG UAE Family Business Report conducted in 2021, surveyed family firms operating in the broader region of “Americas” and provides similar figures (services = 66%, manufacturing = 20%, construction = 8%). However, the survey does not present wholesale and retail as a separate sector. Finally, we consider the annual survey conducted by Family Enterprise USA in 2021. While the proportion of construction (6%) is comparable to our study, the survey does not publish information on wholesale trade and services, thus preventing us from assessing the similarities. While the descriptive elements of our data set are, to some extent, comparable to previous representative surveys, our sample must be interpreted as a convenience sample, which is likely not representative of the entire population of family firms in the U.S. Thus, our sample offers particular insights into relational conflict in small and medium-sized U.S. family firms, rather than family microenterprises (see Table 1).

Measures

Dependent variable. To assess family firm performance, we asked respondents to indicate on a five-point Likert scale the extent to which they were satisfied with the firm’s current performance relative to the rivals. Performance was measured using three individual items: net profit growth, market share, and sales (Cooper & Artz, 1995).

Independent variable. To measure relational conflict, we employ the intragroup conflict scale developed by Jehn (1995) with item wordings adapted to the family business context (Paskewitz & Beck, 2017). Respondents were asked to indicate their agreement on a five-point Likert scale with statements such as “There is much relationship conflict among family members in our firm” or “Family members often get angry with each other while working in our firm”.

Mediator. The mediator, family social capital, was measured using the ISC-FB scale developed by Carr et al. (2011). The scale has twelve items and consists of the structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). Due to the high interdependence between the three dimensions, we included them under a single construct.

Moderator. To measure family ownership, we employ a single item in which respondents were asked to indicate the percentage of ownership in the hands of the controlling family (e.g., Adithipyangkul et al., 2021; Chrisman et al., 2012; Memili et al., 2013).

Control variables. In the analysis, we control for additional variables that can be assumed to affect firm performance (e.g., Lee, 2006). First, to capture maturation effects, we control for the age of the business (i.e., the number of years since the date of incorporation). Second, we control for firm size by asking the respondents to indicate how many people, including management, were employed in the firm on average in the past 12 months. Third, we control for generational involvement using a single item in which the respondents indicated the number of generations (one, two, three, or more) currently involved in the firm’s operations (Arzubiaga et al., 2018). Finally, we introduce four binary dummy variables, each representing a broad industry affiliation (manufacturing, construction, wholesale, services).

Reliability and Validity

To assess the quality of the measurement model, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in Amos. In the first step, we evaluated the overall model fit, and subsequently, to assess the reliability and validity of the latent variables, we observed their composite reliabilities (CR), average variances extracted (AVE), maximum shared variances (MSV), and average shared variances (ASV). The measurement model consists of relational conflict (α = 0.944, CR = 0.945, AVE = 0.863; MSV = 0.396, ASV = 0.246), family social capital (α = 0.924, CR = 0.985, AVE = 0.956; MSV = 0.533, ASV = 0.369), and family firm performance (α = 0.862, CR = 0.862, AVE = 0.677; MSV = 0.218, ASV = 0.146). Overall, the model displays a good fit to the data (χ2 = 333.99, df = 221, CMIN/df = 1.511, CFI = 0.963, RMSEA = 0.054, PCLOSE = 0.266). All constructs display good reliability as the individual CRs are greater than 0.7 (Nunnally, 1978). Moreover, Cronbach’s alpha values are all greater than 0.8, thus indicating a good internal consistency of the measures. Convergent validity is acceptable since all CRs are greater than the AVEs, and AVEs are greater than 0.5 (Hair et al., 2010). The constructs also display a good discriminant validity as both the MSVs and ASVs are less than AVEs (Hair et al., 2010). Further, to support the convergent validity of the outcome variable (firm performance), we use a single item to measure respondent’s overall satisfaction with the firm. Specifically, we employ a single item (“How overall satisfied are you with the business?”) with answers ranging from 1 = Completely dissatisfied to 5 = Extremely satisfied. The correlation between these two variables is positive and significant (r = .595, p < .0001), showing a good convergent validity with respect to different measures of a single construct (Barringer & Bluedorn, 1999). Thus, there are no construct reliability or validity concerns in our study. Because the data were collected in the same period using the same methods, we evaluate the presence of common method bias using Harman’s single factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Exploratory factor analysis does not provide a single-factor solution, suggesting that common method bias is not an issue in our data.

Results

Descriptive statistics along with Pearson correlations between the individual variables are presented in Table 2. Relational conflict is negatively correlated with family social capital (r = –.553, p < .01), firm performance (r = –.171, p < .05), and family ownership (r = –.306, p < .01). Family social capital is also positively correlated with firm performance (r = .375, p < .01). Firm performance is further negatively correlated with family ownership (r = –.174, p < .05), and positively correlated with generational involvement (r = .165, p < .05). Family ownership is negatively correlated with firm age (r = –.187, p < .05), firm size (r = –.251, p < .01), and generational involvement (r = –.156, p < .05). As expected, there is a positive correlation between firm age and firm size (r = .338, p < .01) and firm age and generational involvement (r = .302, p < .01). Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation matrix

| M | SD | Min | Max | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Relational conflict | 2.174 | 1.069 | 1.000 | 5.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| 2. Family social capital | 4.145 | 0.655 | 2.000 | 5.000 | –0.553** | 1.000 | ||||

| 3. Firm performance | 3.798 | 0.713 | 1.670 | 5.000 | –0.171* | 0.375** | 1.000 | |||

| 4. Family ownership | 89.926 | 18.321 | 25.00 | 100.00 | –0.306** | 0.049 | –0.174* | 1.000 | ||

| 5. Firm age | 23.060 | 19.468 | 2.00 | 121.00 | 0.069 | –0.127 | 0.025 | –0.187* | 1.000 | |

| 6. Firm size | 35.058 | 60.660 | 5.00 | 499.00 | 0.048 | − 0.086 | 0.061 | –0.251** | 0.338** | 1.000 |

| 7. Generational involvement | 2.080 | 0.791 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 0.094 | –0.054 | 0.165* | –0.156* | 0.302** | 0.141 |

Note: M = mean, SD = standard deviation

* p < .05, ** p < .01

To test our hypotheses, we use the conditional process analysis tool PROCESS for SPSS (Hayes, 2018). The significance of direct and indirect effects is estimated using 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals based on 5000 bootstrap samples. A statistically significant effect at the 0.05 level exists if the confidence interval does not contain the zero value (Hayes, 2018). To reduce structural multicollinearity, all variables defining product terms are centred before the analysis. The regressions use heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors.

To test hypotheses 1–4, we evaluate a simple mediation model and report the total, direct, and indirect effects (Table 3). Considering firm performance as the outcome variable, we did not observe any significant association between relational conflict and performance (b = –0.013, p = .837). Thus, hypothesis 1 is not supported. However, there is a positive and significant relationship between family social capital and family firm performance (b = 0.391, p < .01), which supports hypothesis 2. Relational conflict is significantly and negatively associated with family social capital (b = –0.379, p < .01), supporting hypothesis 3. In the bottom part of Table 3, we display the estimated total, direct and indirect effects and their 95% confidence intervals. While the total effect is negative and significant, we did not find evidence of a significant direct effect, suggesting that family social capital fully mediates the relationship between relational conflict and family firm performance. Thus, we only find partial support for hypothesis 4 as no evidence of a direct effect of relational conflict on firm performance has been found (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Testing Hypothesis 4 - Mediating role of family social capital

| Variables / Outcome variable | Family social capital | Firm performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.732** (0.249) | 1.663** (0.499) | ||

| Control variables | ||||

| Firm age | –0.002 (0.002) | –0.001 (0.003) | ||

| Firm size | –0.001 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) | ||

| Generational involvement | –0.006 (0.047) | 0.163* (0.070) | ||

| Manufacturing | 0.383* (0.177) | 0.201 (0.234) | ||

| Construction | –0.023 (0.252) | 0.060 (0.205) | ||

| Wholesale | 0.231 (0.189) | 0.205 (0.220) | ||

| Services | 0.394* (0.175) | 0.169 (0.187) | ||

| Independent variable | ||||

| Relational conflict | –0.379** (0.062) | –0.013 (0.064) | ||

| Mediator | ||||

| Family social capital | 0.391** (0.099) | |||

| R2 | 0.409 | 0.202 | ||

| F-statistics | 9.529** | 6.394** | ||

| Direct and indirect effects of relational conflict on firm performance | ||||

| Outcome variable | Firm performance | |||

| b | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Total effect | –0.162* | 0.066 | –0.271 | –0.052 |

| Direct effect | –0.013 | 0.064 | –0.119 | 0.093 |

| Indirect effect | –0.148* | 0.042 | –0.212 | –0.077 |

Note: LLCI = lower limit of the 95% confidence interval, ULCI = upper limit of the 95% confidence interval. Standard errors are presented in parentheses (.)

* p < .05, ** p < .01

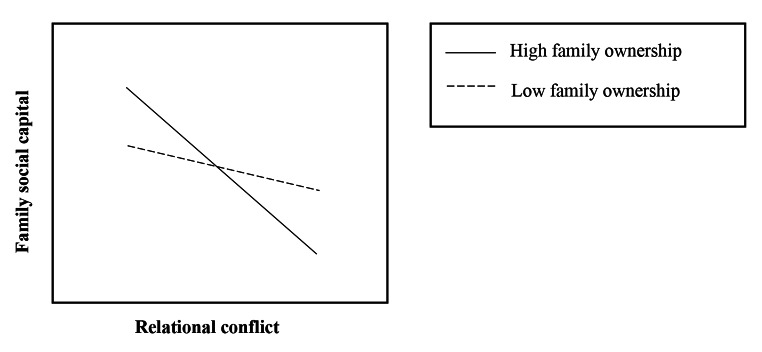

To test hypothesis 5, we assess a simple moderation model while observing the significance of the interaction term and the significance of the conditional effect of the focal predictor (relational conflict) at three conditioning values of the moderator (family ownership): low (minus one standard deviation from the mean), moderate (mean), and high. Because one standard deviation above the mean is above the maximum observed in the data for family ownership, in all subsequent analyses, the maximum measurement for family ownership (100%) is used for conditioning instead. The results are displayed in Table 4. They suggest the existence of a significant and negative relationship between relational conflict and family social capital (b = –0.398, p < .01). Furthermore, the interaction term is significant and negative (b = –0.006, p < .01), which indicates that family ownership strengthens the negative relationship between relational conflict and family social capital. The moderating effect is illustrated in Fig. 1, which presents the interaction plot. The conditional effects of relational conflict on family social capital are statistically significant for all the three conditioning values of family ownership (low, moderate, and high). Thus, hypothesis 5 is supported.

Table 4.

Testing Hypothesis 5 - Moderating role of family ownership

| Variables | Estimates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.940** (0.193) | |||

| Control variables | ||||

| Firm age | –0.002 (0.002) | |||

| Firm size | –0.000 (0.001) | |||

| Generational involvement | –0.025 (0.046) | |||

| Manufacturing | 0.400* (0.178) | |||

| Construction | 0.025 (0.245) | |||

| Wholesale | 0.280 (0.185) | |||

| Services | 0.421* (0.173) | |||

| Independent variable | ||||

| Relational conflict | –0.398** (0.065) | |||

| Moderator | ||||

| Family ownership | –0.001 (0.002) | |||

| Interaction term | ||||

| Relational conflict × Family ownership | –0.006* (0.002) | |||

| R2 | 0.434 | |||

| F-statistics | 9.307** | |||

| Conditional effects of relational conflict on family social capital | ||||

| Conditioning values of family ownership | b | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

| Low | –0.317* | 0.051 | –0.401 | –0.232 |

| Medium | –0.398* | 0.065 | –0.505 | –0.291 |

| High | –0.442* | 0.076 | –0.568 | –0.315 |

Note: Outcome variable: family social capital. LLCI = lower limit of the 95% confidence interval, ULCI = upper limit of the 95% confidence interval. Standard errors are presented in parentheses (.)

* p < .05, ** p < .01

Fig. 1.

Moderating effect of family ownership on the relationship between relational conflict and family social capital: The interaction plot

Hypothesis 6

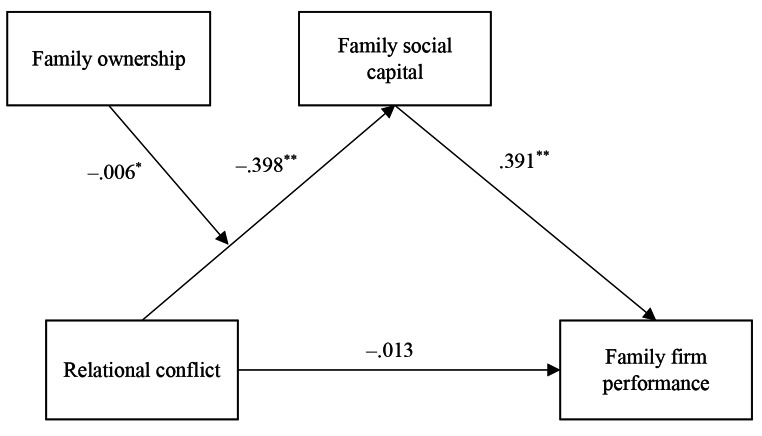

is evaluated using a moderated mediation model. We observe the significance of the direct effect and conditional indirect effect of relational conflict on performance and the significance of the index of moderated mediation (Hayes, 2015). Table 5 presents the results. Consistent with our previous findings, there is a significant and negative relationship between relational conflict and family social capital (b = –0.398, p < .01). Since the interaction term is significant and negative (b = –0.006, p < .01), this relationship is negatively moderated by family ownership. Moreover, a significant and positive relationship is found between family social capital and family firm performance (b = 0.391, p < .01). Again, we have not found any direct association between relational conflict and family firm performance. On the other hand, there are significant and negative indirect effects when family ownership is low, moderate, and high. Finally, the index of moderated mediation is statistically significant at the 0.05 level. In conclusion, we found evidence of a moderated mediation, as predicted by hypothesis 6. However, relational conflict does not harm family firm performance directly but indirectly by harming family social capital. The results are graphically displayed in Fig. 2.

Table 5.

Testing Hypothesis 6 - Moderated mediation

| Variables / Outcome variable | Family social capital | Firm performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.940** (0.193) | 1.636** (0.411) | ||

| Control variables | ||||

| Firm age | –0.002 (0.002) | –0.001 (0.003) | ||

| Firm size | –0.000 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) | ||

| Generational involvement | –0.025 (0.046) | 0.163* (0.070) | ||

| Manufacturing | 0.400* (0.178) | 0.201 (0.234) | ||

| Construction | 0.025 (0.245) | 0.060 (0.205) | ||

| Wholesale | 0.280 (0.185) | 0.205 (0.220) | ||

| Services | 0.421* (0.173) | 0.169 (0.187) | ||

| Independent variable | ||||

| Relational conflict | –0.398** (0.065) | –0.013 (0.064) | ||

| Mediator | ||||

| Family social capital | 0.391** (0.099) | |||

| Moderator | ||||

| Family ownership | –0.001 (0.002) | |||

| Interaction term | ||||

| Relational conflict × Family ownership | –0.006* (0.002) | |||

| R2 | 0.434 | 0.202 | ||

| F-statistics | 9.307** | 6.394** | ||

| Direct and indirect effects | ||||

| Outcome variable | Firm performance | |||

| b | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Direct effect | –0.013 | 0.064 | –0.119 | 0.093 |

| Conditional indirect effect when family ownership is: | ||||

| Low | –0.124* | 0.035 | –0.179 | –0.064 |

| Medium | –0.156* | 0.043 | –0.221 | –0.081 |

| High | –0.173* | 0.049 | –0.248 | –0.087 |

| Index of moderated mediation | –0.002* | 0.001 | –0.004 | –0.001 |

Note: LLCI = lower limit of the 95% confidence interval, ULCI = upper limit of the 95% confidence interval. Standard errors are presented in parentheses (.)

* p < .05, ** p < .01

Fig. 2.

Results of the moderated mediation model

Note: The indirect effect is significant at the 0.05 level for all levels of family ownership. * p < .05, ** p < .01

Robustness Check

Since the data is cross-sectional, we tested an alternative causal model, in which the order of the first two variables predicting family firm performance was switched (e.g. Van Gils et al., 2019). The alternative model specification thus considered that the relationship between family social capital and family firm performance relationship is mediated by relational conflict, with family ownership acting as a moderator of the relational conflict-family firm performance relationship. Consistent with our expectations, there is a positive and significant direct effect of family social capital on family firm performance (b = 0.371, p < .01), but the indirect effect is not significant for any level of family ownership (low, medium, and high), thus providing evidence against the alternative causal path and in favour of our hypotheses (Van Gils et al., 2019). The complete results are displayed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Robustness check – Alternative causal path, relational conflict as a mediator

| Variables / Outcome variable | Relational conflict | Firm performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.699** (0.508) | 1.727** (0.433) | ||

| Control variables | ||||

| Firm age | –0.002 (0.002) | –0.001 (0.003) | ||

| Firm size | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) | ||

| Generational involvement | –0.024 (0.072) | 0.154* (0.070) | ||

| Manufacturing | 0.039 (0.275) | 0.203 (0.224) | ||

| Construction | 0.009 (0.311) | 0.112 (0.199) | ||

| Wholesale | –0.188 (0.232) | 0.231 (0.217) | ||

| Services | 0.118 (0.230) | 0.202 (0.181) | ||

| Independent variable | ||||

| Family social capital | –0.893** (0.102) | 0.371** (0.106) | ||

| Mediator | ||||

| Relational conflict | –0.039 (0.073) | |||

| Moderator | ||||

| Family ownership | –0.006 (0.005) | |||

| Interaction term | ||||

| Relational conflict × Family ownership | –0.001 (0.003) | |||

| R2 | 0.365 | 0.216 | ||

| F-statistics | 14.281** | 6.292** | ||

| Direct and indirect effects | ||||

| Outcome variable | Firm performance | |||

| b | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Direct effect | 0.371 | 0.106 | 0.162 | 0.581 |

| Conditional indirect effect when family ownership is: | ||||

| Low | 0.024 | 0.077 | –0.130 | 0.180 |

| Medium | 0.035 | 0.071 | –0.077 | 0.201 |

| High | 0.041 | 0.081 | –0.083 | 0.300 |

| Index of moderated mediation | 0.001 | 0.004 | –0.005 | 0.010 |

Note: LLCI = lower limit of the 95% confidence interval, ULCI = upper limit of the 95% confidence interval. Standard errors are presented in parentheses (.)

* p < .05, ** p < .01

Discussion

Despite the resilience of family firms, relational conflicts can make them especially fragile (Kubíček & Machek, 2020). Previous family business authors found that relational conflict only has detrimental consequences in family firms (Eddleston & Kellermanns, 2007; Ensley et al., 2007; Nosé et al., 2017). While it is known that relational conflict is harmful, to our knowledge, no study investigated empirically how relational conflict harms firm performance. Previous authors explain their findings using the arguments of the intragroup conflict literature, which assumes that relational conflict is associated with the dissatisfaction of individual team members (Jehn, 1995). Thus, in family firms, relational conflict is believed to reduce goodwill and mutual understanding, induce negative emotions and hostile behaviours, and distract attention from business needs (Eddleston & Kellermanns, 2007). This led us to the expectation that relational conflict has a direct negative effect on firm performance. However, contrary to our expectations, we do not find evidence of any direct effect. This finding is, to some extent, similar to the findings of Hoelscher (2014) who does not find any impact of relational conflict on performance once “family capital” is controlled for1. While there does not seem to be a direct link between relational conflict and firm performance, we show that family social capital, as a unique family-firm-specific variable, enters into the relational conflict-performance relationship as a mediator. Relational conflict harms family social capital, whose lower levels, in turn, deteriorate family firm performance.

We also find that family ownership strengthens the negative relationship between relational conflict and family social capital. This finding can be attributed to an intensified level of negative affect in a situation when family members feel emotionally attached to and identified with the family firm, but relational conflict escalates among family members. In Jehn and Bendersky’s (2003) terminology, family ownership becomes an “exarcebator” of the conflict-outcome relationship, increasing the adverse effects of relational conflict. Intuitively, this finding means that the greater the “family character” of the firm, the worse the negative impact of relational conflict on family social capital becomes. Thus, family firms with high family ownership can be particularly vulnerable to relational conflicts (Eddleston & Kellermanns, 2007). It should be noted that we do not find that relational conflict emerges more easily in family firms than in other types of organizations. However, we do argue that the exact extent of relational conflict, ceteris paribus, does more harm in family firms that display high family ownership.

Our study has theoretical implications for the family business but also the intragroup conflict literature. First, we demonstrate that relational conflict does not harm firm performance directly. Instead, the adverse effects of relational conflict on family firm performance can all be attributed to the erosion of family social capital. This does not, however, contradict previous findings (e.g. Jehn, 1995). For instance, while relational conflict is believed to reduce mutual understanding, it, in fact, deteriorates the relational dimension of social capital. Likewise, when relational conflict is said to shift attention from collective goals, it actually harms the cognitive dimension of social capital. From a broader perspective, the intragroup conflict literature could be enriched by considering that the adverse effects of relational conflict can be attributed to the damage to social capital shared by social group members. Likewise, while the conflict literature finds that trust mediates the conflict-performance relationship (Lau & Cobb, 2010), we provide a broader picture, showing that not only trust, but generally, social capital, can act as this mediator. Overall, we believe that social capital can be used as an overarching concept for studying the adverse effects of dysfunctional conflicts in family firms and other types of organizations or social groups, presenting a contribution beyond family business research.

From the viewpoint of family business literature, there are two major theoretical implications. First, we show that the damage to family social capital, a resource that is unique to family firms, is the primary reason why dysfunctional conflicts are harmful in family firms. Thus, we are among the few authors to investigate the family outcomes of relational conflicts in family firms (Kubíček & Machek, 2020). Second, our findings suggest that family ownership, or more broadly, emotional attachment to the firm and family-firm identification, determines the damage caused by relational conflict. From this point of view, emotional attachment and identification can represent not only endowment but also a burden (Kellermanns et al., 2012); on the one hand, they can help prevent the development of relational conflict, but they can also intensify its negative consequences when the conflict escalates.

For sure, this study is not free of limitations. First, we used an online panel to collect data. We followed recent management studies’ findings that online panels provide results comparable to conventional data collection methods (Porter et al., 2019; Walter et al., 2019). Moreover, we did our best to reduce potential bias and were very selective in admitting observations to the research sample. Second, while we observed enough variance to test our hypotheses, like some other previous authors (e.g., Carr et al., 2011; Eddleston & Kellermanns, 2007; Memili et al., 2013; Merchant et al., 2018; Rousseau et al., 2018; Ruiz Jiménez et al., 2013), we employed a convenience sample of family firms. Although some descriptive statistics of our sample display a reasonable match with previous family business surveys (Table 1), we cannot guarantee that the sample is fully representative of the U.S. population of family firms, whose characteristics are not precisely known. In general, data collection in family business research is constrained by the lack of national databases of family firms (Chang et al., 2008; Lussier & Sonfield, 2009). Additionally, the existing family business studies diverge in their sample structures, making it difficult to compare with prior research. Microenterprises, which represent the vast majority of U.S. family firms, can display different natures of interpersonal conflict and different forms of family social capital than larger firms. While we believe that the theoretical justification of our hypotheses remains valid for all types of businesses, applying our findings to microenterprises should be done with caution. Hence, our study offers implications especially for small and medium-sized firms with more than five employees. Third, while the respondents are family managers, we lack information on their individual ownership stake. Nevertheless, we assume that family managers are well-informed about the company ownership structure and naturally tend to hold an ownership stake (Rousseau et al., 2018), making them qualified enough to reliably answer the survey questions. Fourth, our study is cross-sectional. Thus, whenever possible, we avoid referring to causality and emphasize the existence of directed associations/relationships between variables. Further, we only consider family ownership as the moderator, making it difficult to comment on the extent to which a family firm follows family-centred goals. A fine-grained measure of socioemotional wealth (e.g., Berrone et al., 2012) could provide additional insights into how relational conflict harms family firm performance. Finally, our analysis does not control for the effects of the Covid-19 pandemics. Social distancing and virtual interactions have caused disruptions in social relationships, possibly affecting family firms’ social capital. Likewise, the strain on family members’ physical and psychological health could exacerbate the existing tensions, contributing to existing conflicts among family members and creating new ones (De Massis & Rondi, 2020). Since not all industries have been equally affected by the pandemics, its adverse performance effects are, at least partially, reflected in the effects of industry control variables. Nevertheless, the effects of Covid-19 on social relationships among family members are not considered in the analysis.

Conclusion

This paper hypothesizes and finds supportive evidence for a moderated mediation model in which relational conflict harms firm performance indirectly through the deterioration of family social capital. We also show that family ownership strengthens the adverse effects of relational conflict. Contrary to our expectations, we do not find that relational conflict harms family firm performance directly.

The findings have several practical implications. Family firm owners, especially those holding a significant portion of ownership shares, should be aware of the potential harm that relational conflict can do to interpersonal relationships. In turn, poor relationships can severely harm the family firm. From a practical standpoint, solving this problem in family businesses is difficult. For fear of opening the door to more damaging issues that lie under the surface (Kaye, 1991), some family members tend to postpone conflict resolution, often indefinitely. In family firms, sacrifices are made to preserve even conflicted relationships in the hope they will repair over time, sometimes leading to situations when it becomes unhealthy for the family to remain in the business together (Kaye, 1996). Timely prevention and, if necessary, conflict resolution can help reduce the adverse effects of relational conflict (Alvarado-Alvarez et al., 2020; Caputo et al., 2018) on family social capital in family firms. The emphasis on cooperation, which helps family members understand deeply held beliefs that can be clarified and shared only through intense interaction over time, offers one method to counteract these impacts. Collaboration helps formulate shared norms, which serve as a compass when a family business is threatened and contribute to the development of family social capital (Sorenson et al., 2009). In general, to mitigate the adverse effects of relational conflict, family firms should not hesitate to address nonfamily members as they are often able to diffuse family tensions (Rosecká & Machek, 2021).

Our analysis also shows that there is a need for further research. First, while family social capital is traditionally considered an internal type of social capital (Arregle et al., 2007), it would be worthy to investigate how relational conflict harms the bridging social capital (or “weak ties”) of family firms. Second, psychology literature acknowledges that conflicts can also have positive effects, and future studies could investigate how cognitive conflicts (i.e. task and process conflicts) affect firm performance. While the family business literature already presents findings related to the performance effects of cognitive conflicts in family firms (Eddleston & Kellermanns, 2007), the role of family social capital in this relationship remains unexplored. Another major avenue for future research is the moderating role of family involvement and family essence. Our study only considered family ownership, representing a source of power and family firms’ ability to pursue family-centred goals. However, of equal importance is the willingness to follow these goals (Evert et al., 2018). While family ownership is considered to be associated with family-firm identification (Kotlar et al., 2020), this only represents one of many dimensions of socioemotional wealth (Berrone et al., 2012). Thus, future research could investigate the role of the individual facets of socioemotional wealth in conflict-outcome relationships in family firms, including whether socioemotional wealth represents an endowment or a burden (Kellermanns et al., 2012) when it comes to conflicts in family firms. Finally, family ownership forms part of the organizational context. Showing that family ownership matters, we believe that future research should explore more in depth the broader role of contextual factors that attenuate or exacerbate conflicts within family firms. Those factors can include, for instance, the succession process stage, the presence of nonfamily CEOs, family climate, or cultural norms and rules (Kubíček & Machek, 2020).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the funding support received from the Czech Science Foundation for the project entitled “Intrafamily Conflicts in Family Firms: Antecedents, Effects and Moderators” (registration no.: GA20-04262S).

Appendix Questionnaire items

| Variables | Range | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Relational conflict | I strongly disagree (1) - I strongly agree (5) | Paskewitz & Beck (2017) |

| There is much relationship conflict among family members in our firm. | ||

| Family members often get angry with each other while working in our firm. | ||

| There is much emotional conflict among family members in our firm. | ||

| There is much personal animosity among family members in our firm. | ||

| Family social capital | I strongly disagree (1) - I strongly agree (5) | Carr et al. (2011) |

| Family members who work in this firm engage in honest communication with one another. | ||

| Family members who work in this firm have no hidden agendas. | ||

| Family members who work in this firm willingly share information with one another. | ||

| Family members who work in this firm take advantage of their family relationships to share information. | ||

| Family members who work in this firm have confidence in one another. | ||

| Family members who work in this firm show a great deal of integrity with each other. | ||

| Overall, family members who work in this firm trust each other. | ||

| Family members who work in this firm are usually considerate of each other’s feelings. | ||

| Family members who work in this firm are committed to the goals of this firm. | ||

| There is a common purpose shared among family members who work in this firm. | ||

| Family members who work in this firm view themselves as partners in charting the firm’s direction. | ||

| Family members who work in this firm share the same vision for the future of this firm’s direction. | ||

| Family firm performance | Completely dissatisfied (1) - Extremely satisfied (5) | Cooper & Artz (1995) |

| Relative to your rivals, how satisfied are you with your current performance in terms of net profit growth? | ||

| Relative to your rivals, how satisfied are you with your current performance in terms of market share? | ||

| Relative to your rivals, how satisfied are you with your current performance in terms of sales? |

Declarations

Confirmation

With the submission of this manuscript we would like to undertake that all authors agreed to the submission and that the manuscript is not published, in press, or submitted elsewhere. We confirm that all the research meets the ethical guidelines. We have seen, read, and understood your guidelines on copyright.

Footnotes

In Hoelscher’s (2014) study, “family capital” is understood as information channels, moral infrastructure, identity, and family expectations.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nikola Rosecká, Email: nikola.rosecka@vse.cz.

Ondřej Machek, Email: ondrej.machek@vse.cz.

References

- Adams RE, Laursen B. The correlates of conflict: disagreement is not necessarily detrimental. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(3):445–458. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler PS, Kwon SW. Social capital: prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review. 2002;27(1):17–40. doi: 10.5465/amr.2002.5922314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adithipyangkul P, Hung HY, Leung TY. An auditor’s perspective of executive incentive pay and dividend payouts in Family Firms. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 2021;42(4):697–714. doi: 10.1007/s10834-020-09729-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge D. Family interaction and suicidal behaviour: a brief review. Journal of Family Therapy. 1984;6(3):309–322. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-6427.1984.00652.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado-Alvarez C, Armadans I, Parada MJ. Tracing the roots of constructive conflict management in family firms. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research. 2020;13(2):105–126. doi: 10.1111/ncmr.12164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aragón-Amonarriz C, Arredondo AM, Iturrioz-Landart C. How can responsible family ownership be sustained across generations? A Family Social Capital Approach. Journal of Business Ethics. 2019;159(2):161–185. doi: 10.1007/s10551-017-3728-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arregle JL, Hitt MA, Sirmon DG, Very P. The development of organizational social capital: attributes of family firms. Journal of Management Studies. 2007;44(1):73–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00665.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arzubiaga U, Iturralde T, Maseda A, Kotlar J. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance in family SMEs: the moderating effects of family, women, and strategic involvement in the board of directors. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal. 2018;14(1):217–244. doi: 10.1007/s11365-017-0473-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barach JA, Ganitsky JB. Successful succession in family business. Family Business Review. 1995;8(2):131–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6248.1995.00131.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barki H, Hartwick J. Conceptualizing the construct of interpersonal conflict. International Journal of Conflict Management. 2004;15(3):216–244. doi: 10.1108/eb022913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barringer BR, Bluedorn AC. The relationship between corporate entrepreneurship and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal. 1999;20(5):421–444. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199905)20:5<421::AID-SMJ30>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berrone P, Cruz C, Gomez-Mejia LR, Larraza-Kintana M. Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: do family-controlled firms pollute less? Administrative Science Quarterly. 2010;55(1):82–113. doi: 10.2189/asqu.2010.55.1.82. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berrone P, Cruz C, Gomez-Mejia LR. Socioemotional wealth in family firms: theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Family Business Review. 2012;25(3):258–279. doi: 10.1177/0894486511435355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, Gerard JM. Marital conflict, ineffective parenting, and children’s and adolescents’ maladjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64(1):78–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00078.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, Franck KL, Cook EC. Adolescents’ triangulation in marital conflict and peer relations. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19(4):669–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00616.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo A, Marzi G, Pellegrini MM, Rialti R. Conflict management in family businesses: a bibliometric analysis and systematic literature review. International Journal of Conflict Management. 2018;29(4):519–542. doi: 10.1108/IJCMA-02-2018-0027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale PJ, Probst TM. Social values and social conflict in creative problem solving and categorization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1300–1309. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carr JC, Cole MS, Ring JK, Blettner DP. A measure of variations in internal social capital among family firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 2011;35(6):1207–1227. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00499.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EP, Chrisman JJ, Chua JH, Kellermanns FW. Regional economy as a determinant of the prevalence of family firms in the United States: a preliminary report. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 2008;32(3):559–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00241.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chirico F, Salvato C. Knowledge internalization and product development in Family Firms: when Relational and affective factors Matter. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 2016;40(1):201–229. doi: 10.1111/etap.12114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chrisman JJ, Chua JH, Pearson AW, Barnett T. Family involvement, family influence, and family–centered non–economic goals in small firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 2012;36(2):267–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00407.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:S95–S120. doi: 10.1086/228943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C. (1988). Commentary: The role of conflict in adolescent parent relationships. In M. Gunnar (Ed.), 21st Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology (pp. 181–197). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cooper AC, Artz KW. Determinants of satisfaction for entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing. 1995;10(6):439–457. doi: 10.1016/0883-9026(95)00083-K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daspit JJ, Chrisman JJ, Ashton T, Evangelopoulos N. Family firm heterogeneity: a definition, common themes, Scholarly Progress, and directions Forward. Family Business Review. 2021;34(3):296–322. doi: 10.1177/08944865211008350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Dreu CK, Weingart LR. Task versus relationship conflict, team performance, and team member satisfaction: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(4):741–749. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Massis AV, Rondi E. COVID-19 and the future of family business research. Journal of Management Studies. 2020;57(8):1727–1731. doi: 10.1111/joms.12632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derfler-Rozin R, Sherf EN, Chen G. To be or not to be consistent? The role of friendship and group-targeted perspective in managers’ allocation decisions. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2021;42(6):814–833. doi: 10.1002/job.2490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte Alonso A, Kok S, O’Brien S. Understanding the impact of family firms through social capital theory: a south american perspective. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 2020;41(4):749–761. doi: 10.1007/s10834-020-09669-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eddleston KA, Kellermanns FW. Destructive and productive family relationships: a stewardship theory perspective. Journal of Business Venturing. 2007;22(4):545–565. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ensley MD, Pearson AW, Sardeshmukh SR. The negative consequences of pay dispersion in family and non-family top management teams: an exploratory analysis of new venture, high-growth firms. Journal of Business Research. 2007;60(10):1039–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.12.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evert RE, Sears JB, Martin JA, Payne GT. Family ownership and family involvement as antecedents of strategic action: a longitudinal study of initial international entry. Journal of Business Research. 2018;84:301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frank H, Kessler A, Nosé L, Suchy D. Conflicts in family firms: state of the art and perspectives for future research. Journal of Family Business Management. 2011;1(2):130–153. doi: 10.1108/20436231111167219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fulmer CA, Gelfand MJ. At what level (and in whom) we trust: trust across multiple organizational levels. Journal of Management. 2012;38(4):1167–1230. doi: 10.1177/0149206312439327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gargiulo, M., & Benassi, M. (1999). The dark side of social capital. In S. Gabbay, & R. Leenders (Eds.), Social capital and liability (pp. 298–322). Kluwer.

- Gedajlovic E, Carney M, Chrisman JJ, Kellermanns FW. The adolescence of family firm research: taking stock and planning for the future. Journal of Management. 2012;38(4):1010–1037. doi: 10.1177/0149206311429990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Mejía LR, Cruz C, Berrone P, De Castro J. The bind that ties: socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. Academy of Management Annals. 2011;5(1):653–707. doi: 10.5465/19416520.2011.593320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Mejía LR, Haynes KT, Núñez-Nickel M, Jacobson KJ, Moyano-Fuentes J. Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: evidence from spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly. 2007;52(1):106–137. doi: 10.2189/asqu.52.1.106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th Ed.) Prentice Hall Inc.

- Hayes AF. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2015;50(1):1–22. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based Approach. Second Edition. Guilford Press.

- Haynes KT, Hitt MA, Campbell JT. The dark side of leadership: towards a mid-range theory of hubris and greed in entrepreneurial contexts. Journal of Management Studies. 2015;52(4):479–505. doi: 10.1111/joms.12127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes G, Marshall M, Lee Y, Zuiker V, Jasper CR, Sydnor S, Valdivia C, Masuo D, Niehm L, Wiatt R. Family business research: reviewing the past, contemplating the future. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 2021;42(1):70–83. doi: 10.1007/s10834-020-09732-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero I. How familial is family Social Capital? Analyzing Bonding Social Capital in Family and Nonfamily Firms. Family Business Review. 2018;31(4):441–459. doi: 10.1177/0894486518784475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero I, Hughes M. When family social capital is too much of a good thing. Journal of Family Business Strategy. 2019;10(3):100271. doi: 10.1016/j.jfbs.2019.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoelscher ML. Does family capital outweigh the negative effects of conflict on firm performance? Journal of Family Business Management. 2014;4(1):46–61. doi: 10.1108/JFBM-03-2013-0009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman J, Hoelscher M, Sorenson R. Achieving sustained competitive advantage: a family capital theory. Family Business Review. 2006;19(2):135–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6248.2006.00065.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SA, Gopalakrishna-Remani V, Mishra R, Napier R. Examining the impact of design for environment and the mediating effect of quality management innovation on firm performance. International Journal of Production Economics. 2016;173:142–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2015.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jehn KA. A multimethod examination of the benefits and detriments of intragroup conflict. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1995;40(2):256–282. doi: 10.2307/2393638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jehn KA, Bendersky C. Intragroup conflict in organizations: a contingency perspective on the conflict-outcome relationship. Research in Organizational Behavior. 2003;25:187–242. doi: 10.1016/S0191-3085(03)25005-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jehn KA, Mannix EA. The dynamic nature of conflict: a longitudinal study of intragroup conflict and group performance. Academy of Management Journal. 2001;44(2):238–251. doi: 10.5465/3069453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kansikas J, Murphy L. Bonding family social capital and firm performance. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business. 2011;14(4):533–550. doi: 10.1504/IJESB.2011.043474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye K. Penetrating the cycle of sustained conflict. Family Business Review. 1991;4(1):21–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6248.1991.00021.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye K. When the family business is a sickness. Family Business Review. 1996;9(4):347–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6248.1996.00347.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kellermanns FW, Eddleston KA, Zellweger TM. Article commentary: extending the socioemotional wealth perspective: a look at the dark side. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 2012;36(6):1175–1182. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00544.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler T, Hollbach S. Group-based emotions as determinants of ingroup identification. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2005;41(6):677–685. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2005.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knight D, Pearce CL, Smith KG, Olian JD, Sims HP, Smith KA, Flood P. Top management team diversity, group process, and strategic consensus. Strategic Management Journal. 1999;20(5):445–465. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199905)20:5<445::AID-SMJ27>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kotlar J, De Massis A, Frattini F, Kammerlander N. Motivation gaps and implementation traps: the paradoxical and time-varying effects of family ownership on firm absorptive capacity. Journal of Product Innovation Management. 2020;37(1):2–25. doi: 10.1111/jpim.12503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kubíček A, Machek O. Intrafamily conflicts in family businesses: a systematic review of the literature and agenda for future research. Family Business Review. 2020;33(2):194–227. doi: 10.1177/0894486519899573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lau RS, Cobb AT. Understanding the connections between relationship conflict and performance: the intervening roles of trust and exchange. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2010;31(6):898–917. doi: 10.1002/job.674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leana CR, Van Buren HJ. Organizational social capital and employment practices. Academy of Management Review. 1999;24(3):538–555. doi: 10.5465/amr.1999.2202136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Family firm performance: further evidence. Family Business Review. 2006;19(2):103–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6248.2006.00060.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson H. Conflicts that plague family businesses. Harvard Business Review. 1971;49:90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lussier RN, Sonfield MC. Founder influence in family business: analyzing combined data from six countries. Journal of Small Business Strategy. 2009;20(1):103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Lu SC, Kong DT, Ferrin DL, Dirks KT. What are the determinants of interpersonal trust in dyadic negotiations? Meta-analytic evidence and implications for future research. Journal of Trust Research. 2017;7(1):22–50. doi: 10.1080/21515581.2017.1285241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G, Gómez-Mejía L. The relationship between socioemotional and financial wealth: re-visiting family firm decision making. Management Research. 2016;14(3):215–233. doi: 10.1108/MRJIAM-02-2016-0638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer RC, Davis JH. The effect of the performance appraisal system on trust for management: a field quasi-experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1999;84(1):123–136. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.84.1.123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCann G, Hammond C, Keyt A, Schrank H, Fujiuchi K. A view from afar: rethinking the director’s role in university-based family business programs. Family Business Review. 2004;17(3):203–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6248.2004.00014.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Memili E, Zellweger TM, Fang HC. The determinants of family owner-managers’ affective organizational commitment. Family Relations. 2013;62(3):443–456. doi: 10.1111/fare.12015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant P, Kumar A, Mallik D. Factors influencing family business continuity in indian small and medium enterprises (SMEs) Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 2018;39(2):177–190. doi: 10.1007/s10834-017-9562-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mustakallio M, Autio E, Zahra SA. Relational and contractual governance in Family Firms: Effects on Strategic decision making. Family Business Review. 2002;15(3):205–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6248.2002.00205.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]