Abstract

The mechanisms by which bacteria resist cell-mediated immune responses to cause chronic infections are largely unknown. We report the identification of a large gene present in enteropathogenic strains of Escherichia coli (EPEC) that encodes a toxin that specifically inhibits lymphocyte proliferation and interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, and gamma interferon production in response to a variety of stimuli. Lymphostatin, the product of this gene, is predicted to be 366 kDa and shares significant homology with the catalytic domains of the large clostridial cytotoxins. A mutant EPEC strain that has a disruption in this gene lacks the ability to inhibit lymphokine production and lymphocyte proliferation. Enterohemorrhagic E. coli strains of serotype O157:H7 possess a similar gene located on a large plasmid. Loss of the plasmid is associated with loss of the ability to inhibit IL-2 expression while transfer of the plasmid to a nonpathogenic strain of E. coli is associated with gain of this activity. Among 89 strains of E. coli and related bacteria tested, lifA sequences were detected exclusively in strains capable of attaching and effacing activity. Lymphostatin represents a new class of large bacterial toxins that blocks lymphocyte activation.

Bacteria have evolved a number of mechanisms, including antiphagocytic factors, leukotoxins, and systems for iron chelation, to resist the nonspecific (innate) immune response of vertebrate hosts (25). In addition, several mechanisms to circumvent humoral immunity have been described, such as immunoglobulin A proteases and immunoglobulin-binding proteins. However, few bacterial factors that specifically interfere with cellular immune responses have been described (69). In addition, the mechanisms that allow certain bacterial pathogens to colonize hosts for prolonged periods remain obscure.

Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) is a leading cause of diarrhea among infants in developing countries. EPEC is one of the few known bacterial causes of chronic diarrhea (24, 34, 55). EPEC strains are characterized by their ability to induce profound cytoskeletal rearrangements in host cells that result in the formation of adhesion pedestals upon which the bacteria rest (47). This phenomenon is known as the attaching and effacing effect. Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) strains, a subgroup of Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli, also have attaching and effacing activity (26, 64). We previously reported that EPEC produce and secrete a high-molecular-weight, protease-sensitive factor that selectively inhibits production of interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, IL-5, and gamma interferon by human peripheral and lamina propria mononuclear cells and inhibits proliferation of these cells (35, 36, 41). This inhibitory effect was observed regardless of whether the cells were stimulated by phorbol esters, mitogens, CD3 cross-linking, or antigen. The effect was also seen in macrophage-depleted T-cell populations and in Jurkat cells, indicating that this activity did not require participation of cells other than lymphocytes. Despite the inhibition of lymphocyte function, these cells remain viable, and there is no evidence that they undergo apoptosis (35). We also reported that a cosmid clone isolated from an EPEC genomic library conferred upon a laboratory strain of E. coli the ability to produce a similar effect (36). The purpose of this study was to identify the genes responsible for this lymphocyte inhibitory factor (LIF) activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

E. coli E2348/69 (serotype O127:H6) is a classical EPEC strain isolated during an outbreak of infantile diarrhea and capable of causing diarrhea in adult volunteers (38). E. coli EFC1 was isolated from the feces of a healthy volunteer (46). E. coli EDL933 (serotype O157:H7) is an EHEC strain isolated from an outbreak of hemorrhagic colitis, while EDL933cu is a plasmid-cured derivative of that strain (63). E. coli C600-LK3 is a K-12 strain transformed with the large plasmid of strain EDL933, which had been marked with a Tn801 transposon insertion (32). E. coli DH5α (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) was used for cloning standard plasmids, strain MC1061 (68) was used as a recipient for infection with lambda phage derivatives, strain DH5αλpir (43) was used to propagate suicide vectors, and strain HB101 (pRK2073) was used for triparental mating (14). A collection of enteric bacteria including various pathotypes of E. coli and related species is described in Table 1. All strains were stored at −80°C in 50% Luria broth (LB)–50% glycerol (vol/vol) and were grown in LB or on Luria plates. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 50 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; tetracycline, 15 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 25 μg/ml; and nalidixic acid, 100 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of lifA sequences in strains of E. coli and related organisms

| Species | Strain | Pathotypea | Serotype or serogroup | Attaching and effacing activity | lifA probe results | Reference or sourceb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | 13 | EPEC | O111 | + | + | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 41 | EPEC | O111 | + | + | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 45 | EPEC | O111 | + | + | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 68 | EPEC | O111 | + | + | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 71 | EPEC | O111 | + | + | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 009-271082 | EPEC | O111 | + | + | 30, 31, 49 |

| E. coli | 031-051082 | EPEC | O111 | + | + | 30, 31, 49 |

| E. coli | 031-161182 | EPEC | O111 | + | + | 30, 31, 49 |

| E. coli | 045-291182 | EPEC | O111 | + | + | 30, 31, 49 |

| E. coli | 081-080883 | EPEC | O111 | + | + | 30, 31, 49 |

| E. coli | 2309-77 | EPEC | O111ab:H2 | + | + | 30, 31 |

| E. coli | 2430-78 | EPEC | O111ab:NM | + | + | 5, 16, 30, 31 |

| E. coli | 2198-77 | EPEC | O111ab:NM | + | + | 15, 16 |

| E. coli | 10 | EPEC | O119 | + | − | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 22 | EPEC | O119 | + | − | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 27 | EPEC | O119 | + | − | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 51 | EPEC | O119 | + | − | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 61 | EPEC | O119 | + | − | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 77 | EPEC | O119 | + | − | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 070-210183 | EPEC | O119 | + | − | 30, 31, 49 |

| E. coli | 105-140583 | EPEC | O119 | + | − | 30, 31, 49 |

| E. coli | 34 | EPEC | O119 | + | − | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 0659-79 | EPEC | O119:H6 | + | − | 5, 16, 30 |

| E. coli | 2450-80 | EPEC | O119:H6 | + | − | 5, 30, 31 |

| E. coli | 2395-80 | EPEC | O119:H6 | + | − | 5, 30, 31 |

| E. coli | 023-220982 | EPEC | O126 | + | + | 30, 31, 49 |

| E. coli | 029-261082 | EPEC | O126 | + | + | 30, 31, 49 |

| E. coli | 086-240583 | EPEC | O127 | + | − | 30, 31, 49 |

| E. coli | E2348/69 | EPEC | O127:H6 | + | + | 17, 19, 37, 38 |

| E. coli | 050-250783 | EPEC | O142 | + | + | 30, 31, 49 |

| E. coli | 012-050982 | EPEC | O142 | + | − | 30, 31, 49 |

| E. coli | 042-060983 | EPEC | O142 | + | + | 30, 31, 49 |

| E. coli | 851/71 | EPEC | O142:H6 | + | + | 37, 62 |

| E. coli | 6 | EPEC | O55 | + | + | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 9 | EPEC | O55 | + | + | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 11 | EPEC | O55 | + | − | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 30 | EPEC | O55 | + | + | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 37 | EPEC | O55 | + | + | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 55 | EPEC | O55 | + | + | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 59 | EPEC | O55 | + | + | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 73 | EPEC | O55 | + | + | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 2087-77 | EPEC | O55:H6 | + | + | 5, 16, 30, 31 |

| E. coli | 0660-79 | EPEC | O55:H7 | + | + | 5, 16, 30 |

| E. coli | 0036-78 | EPEC | O55:H7 | + | + | 5 |

| E. coli | 2362-75 | EPEC | O55:NM | + | + | 5, 30, 31 |

| E. coli | 38 | EPEC | O86 | + | − | 30, 31, 39 |

| E. coli | 43 | EPEC | + | + | 30, 31, 39 | |

| E. coli | EDL931 | EHEC | O157:H7 | + | − | 16, 64 |

| E. coli | 86-81 | EHEC | O157:H7 | + | − | 16 |

| E. coli | 86-24 | EHEC | O157:H7 | + | − | 27 |

| E. coli | 85-989 | EHEC | O157:H7 | + | − | CVD |

| E. coli | 85-855 | EHEC | O157:H7 | + | − | CVD |

| E. coli | E3787 | EHEC | O26:H11 | + | + | B. Rowe |

| E. coli | 85-707 | EHEC | O26:H11 | + | + | CVD |

| E. coli | 85-0839 | EHEC | O111:NM | + | + | CVD |

| E. coli | RDEC-1 | REPEC | O15:NM | + | + | 10, 11, 30, 70 |

| E. coli | JM221 | EAEC | O78:H33/35 | − | − | 42, 65, 66 |

| E. coli | 17-2 | EAEC | O?:H2 | − | − | 50, 57, 66 |

| E. coli | 042 | EAEC | O44:H18 | − | − | 66 |

| E. coli | 73-1 | EAEC | − | − | CVD | |

| E. coli | E12860/0 | EIEC | O124:H− | − | − | 59 |

| E. coli | E20850/0 | EIEC | O143:H− | − | − | 59 |

| E. coli | E50851/1 | EIEC | O164:H− | − | − | 59 |

| E. coli | E5273/0 | EIEC | O28ac:H− | − | − | 16, 59 |

| E. coli | E1181A | ETEC | O25:H42 | − | − | CVD |

| E. coli | CFID499-2 | ETEC | O6 | − | − | CVD |

| E. coli | M408C1 | ETEC | O6:H16 | − | − | CVD |

| E. coli | H10407 | ETEC | O78:H11 | − | − | 16, 61 |

| E. coli | E44324 | UPEC | O15:H1 | − | − | 53 |

| E. coli | CFT073 | UPEC | − | − | 46 | |

| E. coli | CFT325 | UPEC | − | − | 46 | |

| E. coli | CFT132 | UPEC | − | − | 46 | |

| E. coli | HS | NF | − | − | 21, 37 | |

| E. coli | FN414 | NF | − | − | 46 | |

| E. coli | EFC4 | NF | − | − | 46 | |

| E. coli | EFC1 | NF | − | − | 46 | |

| E. coli | EFC2 | NF | − | − | 46 | |

| Citrobacter freundii | 29219 | − | − | ATCC | ||

| C. rodentium | 4280 | + | + | 58 | ||

| Hafnia alvei | 13337 | − | − | ATCC | ||

| H. alvei | 10457 | + | − | 3 | ||

| H. alvei | 10790 | + | − | 3 | ||

| H. alvei | 19982 | + | − | 2 | ||

| Salmonella enterica serovar enteritidis | 10697 | − | − | CVD | ||

| Salmonella serovar enteritidis | 3319 | − | − | CVD | ||

| Salmonella enterica serovar typhi | Ty2 | − | − | 13, 23 | ||

| Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium | 14028 | − | − | 44, 45, 54 | ||

| Yersinia enterocolitica | 937 | − | − | 48 | ||

| Yersinia pseudotuberculosis | 527-2 | − | − | J. Glenn Morris |

Pathotype refers to the following categories of pathogenic E. coli: REPEC, rabbit enteropathogenic E. coli; EAEC, enteroaggregative E. coli; EIEC, enteroinvasive E. coli; ETEC, enterotoxigenic E. coli; UPEC, uropathogenic E. coli; and NF, normal flora E. coli from the feces of healthy volunteers.

CVD, Center for Vaccine Development; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection.

Assays for localized adherence and attaching and effacing activities of EPEC were performed with HEp-2 cells as previously described (18).

Bacterial genetic techniques.

E. coli MC1061 containing cosmid IV-8-A (36) was grown in LB medium supplemented with 0.2% maltose to a concentration of approximately 3 × 108 CFU/ml (optical density at 600 nm = 0.3) and infected with λ1105 at a multiplicity of infection of 0.3 as described (68). Transfectants were selected on medium containing kanamycin and tetracycline. Plasmids were recovered from pooled transfectants and were used to transform E. coli DH5α to kanamycin and tetracycline resistance.

DNA sequencing of plasmid templates subcloned from cosmids was performed at the University of Maryland Biopolymer Laboratory by using a model 373A sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Both nested deletions and primer-walking techniques were applied. A 1,791-bp EcoRI fragment was used as a gene probe to identify an additional cosmid from an independently constructed cosmid library of the same EPEC strain. Subclones from this cosmid (10-E-5) were used to complete the DNA sequence described herein.

To construct a lifA mutant, a 4,258-bp HindIII fragment internal to the lifA gene was cloned into pACYC184 (12). Digestion with XmaIII and religation resulted in the excision of a 1,980-bp fragment. The aphA-3 gene, together with upstream translational terminators and a downstream ribosome binding site and start codon, was cloned into this XmaIII site from pUC18K (43), such that the downstream start codon was in frame with the 3′ end of the lifA gene. A SphI-XbaI fragment containing this construction was then cloned into positive-selection suicide vector pCVD442 (17) and introduced into EPEC strain E2348/69 by triparental conjugation (14). Allelic exchange, with selection for loss of the suicide vector and wild-type allele on plates containing kanamycin and sucrose, was performed as previously described (20). The resulting mutant, UMD704, was verified by PCR with Taq DNA polymerase using 30 cycles (annealing at 50°C for 30 s, extension at 72°C for 2 min, denaturation at 94°C for 30 s). The primers for this PCR were Donne-280 (CGG AAC AGT AGG TTC ACC TTC) and Donne-281 (AGT GCC CGT GTT CTT GAA CTG), representing nucleotides 8088 to 8068 and 5863 to 5883 of the lifA sequence, respectively.

Colony hybridization was performed as previously described by using an internal EcoRI fragment representing nucleotides 3201 to 4991 of lifA, which had been labeled with [α-32P]dATP by the random priming method (30).

PBMC stimulation and assay for cytokines.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained from healthy volunteers. Whole blood was diluted 1:1 with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) and was centrifuged (400 × g, 25 min, 21°C) over Histopaque 1077 (Sigma Chemicals Co., St. Louis, Mo.). PBMC were aspirated, washed in PBS, and centrifuged (200 × g, 10 min, 21°C). Cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco BRL) with 20 mM HEPES, 50 μg of gentamicin per ml, and 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Gemini Bioproducts Inc., Calabasas, Calif.) (pH 7.4) at a concentration of 106 cells per ml for all experiments. Cultures were maintained in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for up to 2 days. Bacteria were grown overnight in LB medium, were centrifuged (4,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C), were resuspended in PBS, and were lysed in a French press at 20,000 lb/in2. Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation (1,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C). The protein concentration of the lysates was determined by the bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

After 2 hours of preincubation with bacterial lysates, PBMC were stimulated with the combination of 10 ng of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) per ml and 5 μg of pokeweed mitogen (PWM) per ml. After further incubation for 6 h, PBMC were lysed in TRIzol reagent (Gibco BRL). Yeast tRNA (10 μg/sample) (Gibco BRL) was added, and mRNA was transcribed in 6.6 μl of reverse transcription buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 375 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2) (Promega, Madison, Wis.); 3.3 μl of dithiothreitol (50 mM); 1.5 μl of murine mammary lymphoma virus reverse transcriptase (200 U/ml) (Gibco BRL); 3.0 μl of oligo(dT)16 (0.5 mg/ml) (Sigma); 1.0 μl of RNase inhibitor (40 U/μl) (Promega); 3.0 μl of acetyl-bovine serum albumin (1 mg/ml) (Gibco BRL); 1.5 μl of a mixture of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP (1 mM each); and 1.5 μl of diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water for 1 h at 39°C. Five microliters of cDNA were amplified in a 45.0-μl PCR mixture consisting of 33.75 μl of H2O, 5 μl of 10× PCR buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 500 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2); 4 μl of a mixture of dATP, dCTP, dTTP, and dGTP (1 mM each); 0.25 μl of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Gibco); and 1.0 μl of each primer (20 μM). The sequences of the primers were as follows: IL-2, 5′(ATG TAC AGG ATG CAA CTC CTG TCT T); IL-2, 3′(GTC AGT GTT GAG ATG ATG CTT TGA C); IL-4, 5′(AAC ACA ACT GAG AAG GAA ACC TTC); IL-4, 3′(GCT CGA ACA CTT TGA ATA TTT CTC); IL-5, 5′(GCT TCT GCA TTT GAG TTT GCT AGC T); IL-5, 3′(TGG CCG TCA ATG TAT TTC TTT ATT AAG); IL-8, 5′(ATG ACT TCC AAG CTG GCC GTG GCT); IL-8, 3′(TGA ATT CTC AGC CCT CTT CAA AAA); gamma interferon, 5′(CAG CTC TGC ATC GTT TTG GGT TCT); gamma interferon, 3′(TGC TCT TCG ACC TTG AAA CAG CAT); hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase, 5′(GGA TTA TAC TGC CTG ACC AAG G); and hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase, 3′(CGA GAT GTG ATG AAG GAG ATG G). Reactions were carried out in a Perkin-Elmer PCR cycler with 30 cycles consisting of a denaturing step at 94°C for 30 s, an annealing step at 60°C for 2 min, and an extension step at 72°C for 3 min. PCR products (15 μl/sample) were mixed with 2.0 μl of gel loading buffer per sample and were electrophoresed in a 3% agarose gel. Gels were stained in a 1% ethidium bromide solution and were examined under UV light.

To assay for cytokine secretion, PBMC were exposed to lysates from E. coli strains, stimulated 2 h later with PMA-PWM, and supernatants were harvested 24 h after stimulation. Cytokine concentrations in the supernatant were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according the manufacturer's specifications (Biosource International, Camarillo, Calif.) after a total of 24 h of incubation. Microtiter plates were read at 450 and 680 nm, and cytokine concentrations were determined with a linear-linear standard curve. Raw data were converted to mean values with standard errors, were normalized, and were expressed as percentages of the positive control by using the following formula: (S−N)/(P−N) × 100%, where S equals the cytokine concentration of the sample, P (positive control) equals the mean concentration of duplicate samples from stimulated cells, and N (negative control) equals the mean concentration of duplicate samples from unstimulated cells. Mean values pooled from duplicate samples of three independent experiments were compared using Student's t test. Two-tailed P values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered significant.

Cell proliferation assays.

Caco-2 human colon carcinoma cells (56) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and gentamicin (50 μg/ml). PBMC and Caco-2 cells (2 × 105 per microtiter well) were incubated with bacterial lysates for 2 h and were stimulated with PMA (10 ng/ml) and PWM (5 μg/ml). Two days later, 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine was added to each well, and the incubation was continued for an additional 4 h. PBMC and trypsin-treated Caco-2 cells were aspirated on fiberglass filter paper and were washed, and incorporated radioactivity was measured in a beta scintillation counter. Data were normalized and analyzed as described for cytokine assays.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported herein was deposited in the EMBL database under accession no. AJ133705.

RESULTS

Identification and characterization of lifA.

To localize the gene(s) encoding the LIF, we subjected a cosmid clone encoding LIF activity to mutagenesis by using a minitransposon. Recombinant E. coli strains containing cosmids with transposon inserts were tested for the ability to inhibit expression of IL-2 mRNA by stimulated PBMC and the locations of the transposon inserts were mapped by restriction endonuclease digestion and PCR. All 15 transposon insertions that disrupted LIF activity mapped to a 9-kb region of the cosmid. In contrast, all 27 transposon insertions that retained LIF activity mapped outside of this region. DNA sequencing of the region revealed an open reading frame (ORF) spanning 9,669 bp, which we designate lifA. A putative ribosome-binding site was identified 8 bp upstream of the start codon. The lifA ORF is predicted to encode a protein of 365,950 Da. The size of the predicted protein is compatible with our previous finding that maximum LIF activity is associated with a fraction containing proteins greater than 100 kDa. A search of the available databases with Gapped BLAST (4) revealed significant similarity (28% identical, 47% similar residues) over its entire length with a hypothetical protein of unknown function predicted to be encoded by ORF L7095 on the large plasmid of EHEC O157:H7 strains EDL933 and RIMD 0509952 (8, 40). This finding is compatible with our earlier observation that EDL933 has LIF activity (36). In addition, a stretch of amino acids near the amino terminus bears significant similarity to a region of approximately 500 amino acids at the amino terminus of the large clostridial cytotoxins. These cytotoxins include toxin A and toxin B of Clostridium difficile, lethal toxin of Clostridium sordellii, and alpha toxin of Clostridium novyi. The large clostridial cytotoxins catalyze the glycosidation of critical threonine residues in members of the Ras family of small GTPases, thereby inactivating them (1, 67). It has previously been shown that a recombinant protein consisting of the amino-terminal 546 amino acids of C. sordellii lethal toxin, the domain with which lifA has homology, possesses full enzymatic activity and is capable of glucosidating Ras and Rho in vitro (28). Finally, the protein predicted by lifA bears significant homology to two hypothetical proteins encoded by adjacent ORFs from the Chlamydia trachomatis genome (60).

Construction and characterization of a lifA mutant of EPEC.

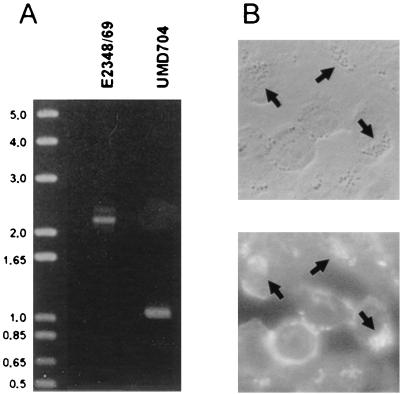

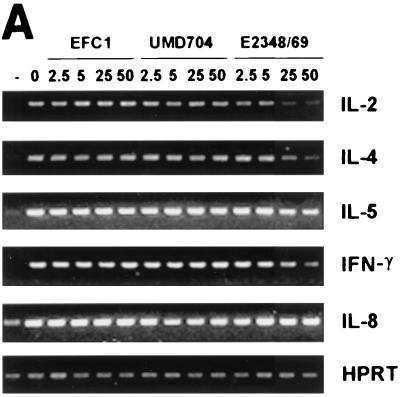

To determine whether the product of lifA is required for the LIF activity of wild-type EPEC, we constructed a mutant of EPEC strain E2348/69 that has a 1,980-bp internal deletion of the lifA sequence. The mutation was confirmed by PCR (Fig. 1A). We analyzed the mutant, designated UMD704, for phenotypes characteristic of EPEC. Like the wild-type EPEC strain from which it was derived, the lifA mutant exhibited autoaggregation when grown in tissue culture medium (data not shown), was capable of localized adherence to epithelial cells, and was able to induce the attaching and effacing effect in infected cells (Fig. 1B). Thus, the disruption of lifA did not affect known EPEC virulence attributes. To assess LIF activity, the levels of IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, and gamma interferon messenger RNA in stimulated PBMC were assayed by reverse transcription-PCR. The levels of mRNA for IL-2, IL-4, and gamma interferon were markedly reduced in a dose-dependent fashion when the cells were incubated in the presence of lysates from the wild-type EPEC strain. The reduction for IL-5 mRNA was less pronounced and was only observed in high concentrations of wild-type EPEC lysate. In the presence of lysates from the lifA mutant or with lysates from a commensal E. coli strain, no lymphokine inhibition was observed. The decrease in mRNA concentrations of IL-2, IL-4, and gamma interferon suggests a transcriptional regulation of lymphokine expression. In contrast, there was no detectable effect on IL-8 mRNA levels (Fig. 2A) even in the highest concentrations of bacterial lysates tested. To quantitate the decrease in lymphokine expression, cell supernatants were assayed after 24 h of incubation by using ELISA. IL-2, IL-4, and gamma interferon protein concentrations were reduced in a dose-dependent fashion in cells treated with lysates from wild-type EPEC in comparison to cells treated with lysates from the lifA mutant and from the commensal E. coli strain (Fig. 2B). The differences between the wild type and lifA mutant in ability to suppress IL-2, IL-4, and gamma interferon protein expression were statistically significant at concentrations greater than or equal to 2.5, 25, and 5 μg/ml, respectively. There was no significant difference between the wild-type strain and the lifA mutant in ability to suppress IL-5 protein expression, although there appeared to be some suppression at higher doses. There was no difference between the lifA mutant strain and the commensal strain in ability to suppress expression of IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, or gamma interferon at any dose, with one exception. At doses less than or equal to 5 μg/ml, there was significantly more IL-2 produced by cells exposed to lysates from the lifA mutant than by cells exposed to lysates from the commensal strain.

FIG. 1.

A lifA mutant of EPEC retains the ability to perform localized adherence and attaching and effacing activities. By allelic exchange, the wild-type lifA locus of EPEC strain E2348/69 was replaced with an allele that contains an 1,890-bp deletion, at which site a nonpolar kanamycin resistance cassette was inserted, to create the lifA mutant strain UMD704. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of the products of a PCR targeting a portion of the lifA gene. The product from mutant strain UMD704 is approximately 1,130-bp smaller than that from the wild-type strain E2348/69, confirming the replacement of the 1,980-bp fragment with the 850-bp aphA-3 gene cassette. The sizes (in kilobase pairs) of molecular standards are indicated on the left. (B) Phase-contrast micrograph (top) and corresponding fluorescein isothiocyanate-phalloidin fluorescence micrograph (bottom) of HEp-2 cells infected the lifA mutant UMD704. Arrows show microcolonies of bacteria associated with accumulations of filamentous actin that are characteristic of the localized adherence and attaching and effacing phenotypes.

FIG. 2.

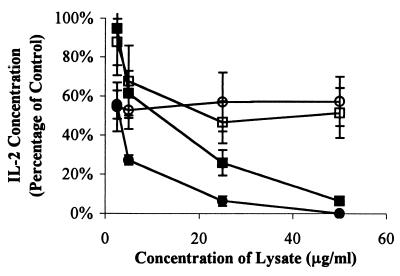

Lymphostatin is required for EPEC-mediated inhibition of lymphokine expression by PBMC. (A) Effect of bacterial lysates on lymphokine mRNA expression. PBMC were incubated in the absence of bacterial lysates and were left unstimulated (−) or exposed to 0, 2.5, 5, 25, or 50 μg/ml of bacterial lysates from commensal E. coli EFC1, lifA mutant EPEC strain UMD704, or wild-type EPEC stain E2348/69 as indicated and were stimulated with PMA-PWM. Expression of IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), IL-8, and hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase mRNA were assessed by reverse transcription-PCR. (B) Effect of bacterial lysates on lymphokine protein expression. PBMC were incubated with lysates from wild-type EPEC strain E2348/69 (circles), EPEC lifA mutant UMD704 (squares), or commensal E. coli EFC1 (triangles) and were stimulated as indicated in the legend to panel A. Values were calculated as described in Materials and Methods as percentages of concentrations measured in cells stimulated in the absence of lysates and are pooled from duplicate values of three independent experiments. Error bars represent standard errors of the means (SEMs). The absolute mean values (± SEMs) for cells stimulated in the absence of lysates were 4.38 ± 1.18 ng/ml for IL-2, 37.2 ± 4.8 pg/ml for IL-4, 99.7 ± 34.6 pg/ml for IL-5, and 1.84 ± 0.25 ng/ml for gamma interferon.

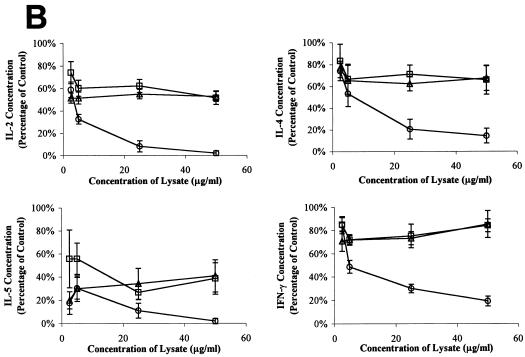

To determine whether the product of lifA is required for inhibition of lymphocyte proliferation, we measured the effect of E. coli lysates on incorporation of [3H]thymidine into stimulated PBMC. PBMC proliferation was markedly inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by the cell lysate of wild-type EPEC, but not by the lysates of the commensal E. coli strain or the lifA mutant (Fig. 3A). The difference between the wild-type strain and the lifA mutant was statistically significant at all concentrations of bacterial lysate tested. In contrast, none of the lysates from the three bacterial strains tested inhibited proliferation of human intestinal Caco-2 cells (Fig. 3B). In these experiments, there was a large variation in the effect of lysates from the commensal E. coli strain on Caco-2 proliferation, due in part to the relatively small difference in proliferation between unstimulated Caco-2 cells and those stimulated with PWM-PMA. However, the results with the wild-type strain and the lifA mutant were very similar and reproducible, indicating that the product of this gene has no effect on Caco-2 cell proliferation. Given the sequence homology between the product of lifA and the large clostridial cytotoxins, which disrupt the actin cytoskeleton and cause cell rounding by inactivating Rho family GTPases (67), we investigated whether EPEC lysates had any effect on actin distribution in tissue culture cells. We observed no effect of lysates of either the wild-type EPEC strain or the lifA mutant on the distribution of actin in HEp-2 cells or on cell morphology as assessed by fluorescence microscopy using fluorescein isothiocyanate-phalloidin (data not shown). Since the lifA gene product specifically inhibits lymphokine production and lymphocyte proliferation, we have named this protein lymphostatin.

FIG. 3.

Lymphostatin is required for inhibition of lymphocyte but not epithelial cell proliferation by EPEC. PBMC (A) or Caco-2 cells (B) were incubated with lysates from wild-type EPEC strain E2348/69 (circles), EPEC lifA mutant UMD704 (squares), or commensal E. coli strain EFC1 (triangles), stimulated with PMA-PWM, and incorporation of thymidine was measured by scintillation counting after 2 days. Values were calculated as percentages of controls as described in Materials and Methods. Data shown represent the mean percentages ± SEMs from quadruple determinations of two independent experiments.

Prevalence of lifA sequences among enteric bacteria and correlation with LIF activity.

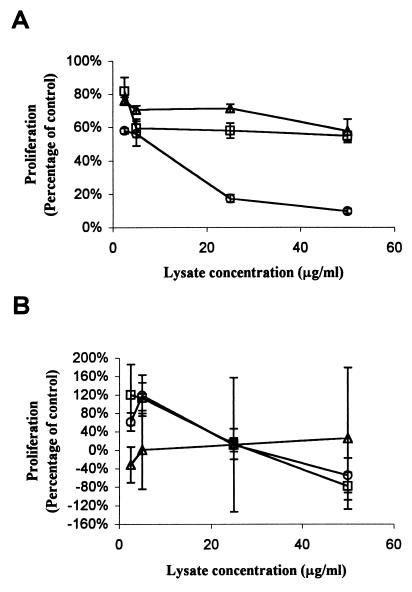

To determine the distribution of the lifA gene among enteric bacteria, we used a 1,791-bp internal EcoRI fragment as a DNA probe to detect lifA sequences in a panel of E. coli strains and related species by colony hybridization. A strong positive signal was detected in 35 of 60 strains of E. coli and related species capable of attaching and effacing activity, but was detected in 0 of 29 strains incapable of attaching and effacing (P < 0.001, χ21 test) (Table 1). Among EPEC strains, more O111 strains (13 of 13) and O55 strains (11 of 12) than O119 strains (0 of 12) were probe positive. All five strains tested and found to have LIF activity yielded a strong hybridization signal with the lifA probe. In contrast, all five strains tested that lacked LIF activity, including O119:H6 EPEC strain 0659-79, were probe negative (P = 0.008, Fisher's exact test). As expected, the EHEC O157:H7 strains tested did not hybridize with the probe, since there is insufficient DNA similarity between lifA and the ORF L7095 on the large plasmid of EHEC to yield a positive probe signal under stringent conditions. To determine whether ORF L7095 of EHEC could potentially encode the LIF activity found in O157:H7 strains, we compared the ability of EHEC strain EDL933 to inhibit IL-2 expression with that of a plasmid-cured derivative of that strain (EDL933cu). Whereas lysates of strain EDL933 inhibited IL-2 production by PBMC in a dose-dependent fashion, there was no effect of lysates of strain EDL933cu on IL-2 expression (Fig. 4). The difference in ability to suppress IL-2 expression between strains EDL933 and EDL933cu were statistically significant at lysate protein concentrations greater than or equal to 5 μg/ml. Moreover, lysates of a recombinant E. coli K-12 strain into which the large plasmid of EHEC had been introduced inhibited IL-2 production while lysates of the same strain without the plasmid did not. This difference was significant at concentrations of 25 μg/ml and higher. This result indicates that a factor encoded on the EHEC plasmid is required for LIF activity in E. coli O157:H7. The best candidate for this factor is the product of ORF L7095.

FIG. 4.

The large plasmid of E. coli O157:H7 encodes a factor that is required for inhibition of IL-2 expression by PBMC. PBMC were exposed to various concentrations of bacterial lysates from EHEC wild-type strain EDL933 (closed circles), the plasmid-cured derivative EDL933cu (open circles), E. coli K-12 strain C600 (open squares), or strain C600-LK3 (transformed with the large EHEC plasmid, closed squares). Cells were stimulated 2 h later with the PMA-PWM combination, and supernatants were harvested after a total of 24 h. Concentrations of IL-2 in the supernatant were measured by ELISA. Values were calculated as described in Materials and Methods as percentages of concentrations measured in cells stimulated in the absence of lysates and are pooled from duplicate values of three independent experiments. Error bars represent SEMs. The absolute mean value (±SEM) for cells stimulated in the absence of lysates was 3.78 ± 1.48 ng/ml.

DISCUSSION

In earlier studies, we described a LIF produced by EPEC and related pathogens that blocks cytokine expression and lymphocyte proliferation without inducing apoptosis or otherwise killing cells (35, 36, 41). In the present study, we report the identification of the lifA gene of EPEC strain E2348/69 isolated from a cosmid clone that expresses inhibitory activity. To test the role of lifA in lymphocyte activation, we generated a nonpolar, in-frame mutation of the gene. Lysates of this mutant lacked the ability of wild-type EPEC lysates to inhibit expression of IL-2, IL-4, and gamma interferon mRNA and protein in mitogen-stimulated lymphocytes. The expression of IL-8 was unaffected. Furthermore, lysates from wild-type EPEC caused a dose-dependent decrease in lymphocyte proliferation; a normal proliferative response was observed in mitogen-stimulated lymphocytes exposed to the lysates from the lifA mutant. Epithelial cells were unaffected and did not show a decreased proliferative response or cytoskeletal disruption. We therefore conclude that lifA is required for the inhibitory activity observed in mitogen-stimulated lymphocytes exposed to lysates of wild-type EPEC.

The lifA gene spans 9,669 bp and is thus the largest reported gene in E. coli. Its putative product, lymphostatin, has a molecular mass of 366 kDa, making it one of the largest bacterial toxins known. Lymphostatin bears significant homology to the large clostridial cytotoxins in a stretch of approximately 500 amino acid residues located near the amino terminus. This region of the C. difficile toxin B possesses full enzymatic activity, but only when microinjected into cells, suggesting that the rest of the molecule, with which lymphostatin lacks homology, contains sequences for cell binding and translocation (29). Interestingly, in EPEC and Clostridium, this conserved stretch of DNA contains nucleotides encoding for a “D-X-D motif”. This D-X-D motif has been implicated to be the enzymatically active site of a glucohydrolase-glycosyltransferase activity (9). Large clostridial cytotoxins have been shown to glycosylate small GTP-binding proteins, like Rho, Rac, or Cdc42, at a conserved threonine site, thereby inactivating them (67). Glycosylation of small GTP-binding proteins leads to profound changes in the actin cytoskeleton with characteristic rounding of epithelial cells. However, in our experiments, lifA was associated with a profound effect on lymphokine expression but did not cause changes in the epithelial cell cytoskeleton, suggesting a different mechanism of action. It is possible that lymphostatin glycosylates other small GTP-binding proteins, exhibits specificity for host cell receptors, or works through an unidentified mechanism altogether. Elucidation of the mechanism by which lymphostatin functions awaits further investigation. Although we have shown that the lifA gene is required for inhibitory activity, we have not proven that lymphostatin is sufficient for this activity. To do so will require purified protein, which has been difficult to obtain since it appears to be produced in small amounts and to be labile (data not shown).

Colony hybridization with an internal lifA probe identified the presence of a similar gene in other EPEC strains, in EHEC strains of serotypes other than O157:H7, and in Citrobacter rodentium. Thus, DNA sequences similar to lifA are common in bacteria that perform the attaching and effacing lesions on host epithelial cells, but were not found in other E. coli and related organisms. The attaching and effacing effect is encoded by a large pathogenicity island known as the locus of enterocyte effacement. However, at least in EPEC strain E2348/69 and EHEC strain EDL933, lifA is not part of this pathogenicity island (22, 52).

In the present study, we found that EHEC O157:H7 strains do not yield a positive signal in hybridization experiments, yet we determined that the large plasmid of strain EDL933 is necessary and sufficient for lymphocyte inhibition. The most likely candidate for the gene encoding the inhibitory activity is ORF L7095, which is predicted to encode a protein that has similarity (28% identical, 47% similar residues) to lymphostatin. This low level of similarity possibly accounts for the lack of a positive hybridization signal. Studies are in progress to isolate and clone this gene to determine whether alone it can confer inhibitory activity to a recombinant E. coli strain.

Interestingly, a notable characteristic of attaching and effacing pathogens is their ability to colonize their hosts for prolonged periods. EPEC is a leading cause of both acute and chronic diarrhea in developing countries, while O157:H7 EHEC strains cause life-threatening hemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic-uremic syndrome and can colonize patients for prolonged periods of time (6, 7, 33, 51). One potential consequence of lymphostatin expression might be the suppression of an immune response to the bacteria, prolonging the infection and increasing the opportunity for transmission to new hosts. Enteric bacterial products similar to lymphostatin could also play a role in deregulating cytokine production in chronic inflammatory syndromes such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. The further finding of sequences related to lymphostatin in Chlamydia suggests that similar proteins may contribute to chronic infections that lead to blindness, infertility, and perhaps atherosclerosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

J.-M.A.K. and I.C.A.S. contributed equally to this work.

We thank James Kaper for providing an EPEC cosmid library.

This work was supported by Public Health Service award DK-47708 from the National Institutes of Health and by a fellowship award (J.-M.A.K.) from the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aktories K. Rho proteins: targets for bacterial toxins. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:282–288. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert M J, Alam K, Islam M, Montanaro J, Rahman A S M H, Haider K, Hossain M A, Kibriya A K M G, Tzipori S. Hafnia alvei, a probable cause of diarrhea in humans. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1507–1513. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.4.1507-1513.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albert M J, Faruque S M, Ansaruzzaman M, Islam M M, Haider K, Alam K, Kabir I, Robins-Browne R. Sharing of virulence-associated properties at the phenotypic and genetic levels between enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and Hafnia alvei. J Med Microbiol. 1992;37:310–314. doi: 10.1099/00222615-37-5-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schäffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldini M M, Nataro J P, Kaper J B. Localization of a determinant for HEp-2 adherence by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1986;52:334–336. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.334-336.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell B P, Goldoft M, Griffin P M, Davis M A, Gordon D C, Tarr P I, Bartleson C A, Lewis J H, Barrett T J, Wells J G, Baron R, Kobayashi J. A multistate outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7-associated bloody diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome from hamburgers: the Washington experience. JAMA. 1994;272:1349–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bender J B, Hedberg C W, Besser J M, Boxrud D J, Macdonald K L, Osterholm M T. Surveillance for Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections in Minnesota by molecular subtyping. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:388–394. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708073370604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burland V, Shao Y, Perna N T, Plunkett G, Sofia H J, Blattner F R. The complete DNA sequence and analysis of the large virulence plasmid of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:4196–4204. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.18.4196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busch C, Hofmann F, Selzer J, Munro S, Jeckel D, Aktories K. A common motif of eukaryotic glycosyltransferases is essential for the enzyme activity of large clostridial cytotoxins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19566–19572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantey J R, Inman L R. Diarrhea due to Escherichia coli strain RDEC-1 in the rabbit: the Peyer's patch as the initial site of attachment and colonization. J Infect Dis. 1981;143:440–446. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantey J R, Lushbaugh W B, Inman L R. Attachment of bacteria to intestinal epithelial cells in diarrhea caused by Escherichia coli strain RDEC-1 in the rabbit: stages and role of capsule. J Infect Dis. 1981;143:219–229. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang A C Y, Cohen S N. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chatfield S N, Fairweather N, Charles I, Pickard D, Levine M, Hone D, Posada M, Strugnell R A, Dougan G. Construction of a genetically defined Salmonella typhi Ty2 aroA, aroC mutant for the engineering of a candidate oral typhoid-tetanus vaccine. Vaccine. 1992;10:53–60. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(92)90420-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chikami G K, Fierer J, Guiney D G. Plasmid-mediated virulence in Salmonella dublin demonstrated by use of a Tn5-oriT construct. Infect Immun. 1985;50:420–424. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.2.420-424.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cleary T G, Mathewson J J, Faris E, Pickering L K. Shiga-like cytotoxin production by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli serogroups. Infect Immun. 1985;47:335–337. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.1.335-337.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donnenberg M S, Donohue-Rolfe A, Keusch G T. Epithelial cell invasion: an overlooked property of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) associated with the EPEC adherence factor. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:452–459. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. Construction of an eae deletion mutant of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by using a positive-selection suicide vector. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4310–4317. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4310-4317.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donnenberg M S, Nataro J P. Methods for studying adhesion of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1995;253:324–336. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(95)53028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donnenberg M S, Tacket C O, James S P, Losonsky G, Nataro J P, Wasserman S S, Kaper J B, Levine M M. The role of the eaeA gene in experimental enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection. J Clin Investig. 1993;92:1412–1417. doi: 10.1172/JCI116717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donnenberg M S, Yu J, Kaper J B. A second chromosomal gene necessary for intimate attachment of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to epithelial cells. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4670–4680. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.15.4670-4680.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DuPont H L, Formal S B, Hornick R B, Synder M J, Libonati J P, Sheahan D G, LaBrec E H, Kalas J P. Pathogenesis of Escherichia coli diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197107012850101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elliott S J, Wainwright L A, McDaniel T K, Jarvis K G, Deng Y, Lai L-C, McNamara B P, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. The complete sequence of the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) of enteropathogenic E. coli E2348/69. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elsinghorst E A, Baron L S, Kopecko D J. Penetration of human intestinal epithelial cells by Salmonella: molecular cloning and expression of Salmonella typhi invasion determinants in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5173–5177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fagundes Neto U, Ferreira V, Patricio F R S, Mostaço V L, Trabulsi L R. Protracted diarrhea: the importance of the enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) strains and Salmonella in its genesis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1989;8:207–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finlay B B, Falkow S. Common themes in microbial pathogenicity revisited. Microbiol Rev. 1997;61:136–169. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.2.136-169.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Francis D H, Collins J E, Duimstra J R. Infection of gnotobiotic pigs with an Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain associated with an outbreak of hemorrhagic colitis. Infect Immun. 1986;51:953–956. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.3.953-956.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffin P M, Ostroff S M, Tauxe R V, Greene K D, Wells J G, Lewis J H, Blake P A. Illnesses associated with Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections: a broad clinical spectrum. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:705–712. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-9-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofmann F, Busch C, Aktories K. Chimeric clostridial cytotoxins: identification of the N-terminal region involved in protein substrate recognition. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1076–1081. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1076-1081.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofmann F, Busch C, Prepens U, Just I, Aktories K. Localization of the glucosyltransferase activity of Clostridium difficile toxin B to the N-terminal part of the holotoxin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11074–11078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jerse A E, Gicquelais K G, Kaper J B. Plasmid and chromosomal elements involved in the pathogenesis of attaching and effacing Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3869–3875. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.3869-3875.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jerse A E, Yu J, Tall B D, Kaper J B. A genetic locus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli necessary for the production of attaching and effacing lesions on tissue culture cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7839–7843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karch H, Heesemann J, Laufs R, O'Brien A D, Tacket C O, Levine M M. A plasmid of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 is required for expression of a new fimbrial antigen and for adhesion to epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1987;55:455–461. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.2.455-461.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karch H, Rüssmann H, Schmidt H, Schwarzkopf A, Heesemann J. Long-term shedding and clonal turnover of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 in diarrheal diseases. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1602–1605. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1602-1605.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khoshoo V, Bhan M K, Mathur M, Raj P. A fatal severe enteropathy associated with enteropathogenic E. coli. Indian Pediatr. 1988;25:308–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klapproth J-M, Donnenberg M S, Abraham J M, James S P. Products of enteropathogenic E. coli inhibit lymphokine production by gastrointestinal lymphocytes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1996;271:G841–G848. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.271.5.G841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klapproth J-M, Donnenberg M S, Abraham J M, Mobley H L T, James S P. Products of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli inhibit lymphocyte activation and lymphokine production. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2248–2254. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2248-2254.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levine M M, Bergquist E J, Nalin D R, Waterman D H, Hornick R B, Young C R, Sotman S, Rowe B. Escherichia coli strains that cause diarrhoea but do not produce heat-labile or heat-stable enterotoxins and are non-invasive. Lancet. 1978;i:1119–1122. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levine M M, Nataro J P, Karch H, Baldini M M, Kaper J B, Black R E, Clements M L, O'Brien A D. The diarrheal response of humans to some classic serotypes of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is dependent on a plasmid encoding an enteroadhesiveness factor. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:550–559. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.3.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levine M M, Prado V, Robins-Browne R, Lior H, Kaper J B, Moseley S L, Gicquelais K, Nataro J P, Vial P, Tall B. Use of DNA probes and HEp-2 cell adherence assay to detect diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:224–228. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Makino K, Ishii K, Yasunaga T, Hattori M, Yokoyama K, Yutsudo C H, Kubota Y, Yamaichi Y, Iida T, Yamamoto K, Honda T, Han C G, Ohtsubo E, Kasamatsu M, Hayashi T, Kuhara S, Shinagawa H. Complete nucleotide sequences of 93-kb and 3.3-kb plasmids of an enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 derived from Sakai outbreak. DNA Res. 1998;5:1–9. doi: 10.1093/dnares/5.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malstrom C, James S. Inhibition of murine splenic and mucosal lymphocyte function by enteric bacterial products. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3120–3127. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3120-3127.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mathewson J J, Johnson P C, DuPont H L, Satterwhite T K, Winsor D K. Pathogenicity of enteroadherent Escherichia coli in adult volunteers. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:524–527. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.3.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ménard R, Sansonetti P J, Parsot C. Nonpolar mutagenesis of the ipa genes defines IpaB, IpaC, and IpaD as effectors of Shigella flexneri entry into epithelial cells. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5899–5906. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.18.5899-5906.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michetti P, Mahan M J, Slauch J M, Mekalanos J J, Neutra M R. Monoclonal secretory immunoglobulin A protects mice against oral challenge with the invasive pathogen Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1786–1792. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.5.1786-1792.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller S I, Pulkkinen W S, Selsted M E, Mekalanos J J. Characterization of defensin resistance phenotypes associated with mutations in the phoP-virulence regulon of Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3706–3710. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3706-3710.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mobley H L T, Green D M, Trifillis A L, Johnson D E, Chippendale G R, Lockatell C V, Jones B D, Warren J W. Pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli and killing of cultured human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells: role of hemolysin in some strains. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1281–1289. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.5.1281-1289.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moon H W, Whipp S C, Argenzio R A, Levine M M, Giannella R A. Attaching and effacing activities of rabbit and human enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in pig and rabbit intestines. Infect Immun. 1983;41:1340–1351. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.3.1340-1351.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morris J G, Jr, Prado V, Ferreccio C, Robins-Browne R M, Bordun A M, Cayazzo M, Kay B A, Levine M M. Yersinia enterocolitica isolated from two cohorts of young children in Santiago, Chile: incidence of and lack of correlation between illness and proposed virulence factors. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2784–2788. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.12.2784-2788.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nataro J P, Baldini M M, Kaper J B, Black R E, Bravo N, Levine M M. Detection of an adherence factor of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli with a DNA probe. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:560–565. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nataro J P, Deng Y, Maneval D R, German A L, Martin W C, Levine M M. Aggregative adherence fimbriae I of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli mediate adherence to HEp-2 cells and hemagglutination of human erythrocytes. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2297–2304. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2297-2304.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Orr P, Milley D, Colby D, Fast M. Prolonged fecal excretion of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli following diarrheal illness. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:796–797. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.4.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perna N T, Mayhew G F, Pósfai G, Elliott S J, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B, Blattner F R. Molecular evolution of a pathogenicity island from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3810–3817. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3810-3817.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Phillips I, Eykyn S, King A, Gransden W R, Rowe B, Frost J A, Gross R J. Epidemic multiresistant Escherichia coli infection in West Lambeth health district. Lancet. 1988;i:1038–1041. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pulkkinen W S, Miller S I. A Salmonella typhimurium virulence protein is similar to a Yersinia enterocolitica invasion protein and a bacteriophage Lambda outer membrane protein. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:86–93. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.1.86-93.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rothbaum R, McAdams A J, Giannella R, Partin J C. A clinicopathological study of enterocyte-adherent Escherichia coli: a cause of protracted diarrhea in infants. Gastroenterol. 1982;83:441–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rousset M. The human colon carcinoma cell lines HT-29 and Caco-2: two in vitro models for the study of intestinal differentiation. Biochimie (Paris) 1986;68:1035–1040. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(86)80177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Savarino S J, Fasano A, Robertson D C, Levine M M. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli elaborate a heat-stable enterotoxin demonstrable in an in vitro rabbit intestinal model. J Clin Investig. 1991;87:1450–1455. doi: 10.1172/JCI115151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schauer D B, Falkow S. The eae gene of Citrobacter freundii biotype 4280 is necessary for colonization in transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4654–4661. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4654-4661.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith H R, Scotland S M, Chart H, Rowe B. Vero cytotoxin production and presence of VT genes in strain of Escherichia coli and Shigella. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;42:173–177. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stephens R S, Kalman S, Lammel C, Fan J, Marathe R, Aravind L, Mitchell W, Olinger L, Tatusov R L, Zhao Q X, Koonin E V, Davis R W. Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science. 1998;282:754–759. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tacket C O, Losonsky G, Link H, Hoang Y, Guesry P, Hilpert H, Levine M M. Protection by milk immunoglobulin concentrate against oral challenge with enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1240–1243. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198805123181904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tzipori S, Gibson R, Montanaro J. Nature and distribution of mucosal lesions associated with enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli in piglets and the role of plasmid-mediated factors. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1142–1150. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1142-1150.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tzipori S, Karch H, Wachsmuth K I, Robins-Browne R M, O'Brien A D, Lior H, Cohen M L, Smithers J, Levine M M. Role of a 60-megadalton plasmid and Shiga-like toxins in the pathogenesis of infection caused by enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in gnotobiotic piglets. Infect Immun. 1987;55:3117–3125. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.12.3117-3125.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tzipori S, Wachsmuth I K, Chapman C, Birner R, Brittingham J, Jackson C, Hogg J. The pathogenesis of hemorrhagic colitis caused by Escherichia coli O157:H7 in gnotobiotic pigs. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:712–716. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.4.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vial P A, Mathewson J J, DuPont H L, Guers L, Levine M M. Comparison of two assay methods for patterns of adherence to HEp-2 cells of Escherichia coli from patients with diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:882–885. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.5.882-885.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vial P A, Robins-Browne R, Lior H, Prado V, Kaper J B, Nataro J P, Maneval D, Elsayed A, Levine M M. Characterization of enteradherent-aggregative Escherichia coli, a putative agent of diarrheal disease. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:70–79. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Von Eichel-Streiber C, Boquet P, Sauerborn M, Thelestam M. Large clostridial cytotoxins--a family of glycosyltransferases modifying small GTP-binding proteins. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:375–382. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)10061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Way J C, Davis M A, Morisato D, Roberts D E, Kleckner N. New Tn10 derivatives for transposon mutagenesis and for construction of lacZ operon fusions by transposition. Gene. 1984;32:369–379. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilson M, Seymour R, Henderson B. Bacterial perturbation of cytokine networks. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2401–2409. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2401-2409.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wolf M K, Andrews G P, Fritz D L, Sjogren R W, Jr, Boedeker E C. Characterization of the plasmid from Escherichia coli RDEC-1 that mediates expression of adhesin AF/R1 and evidence that AF/R1 pili promote but are not essential for enteropathogenic disease. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1846–1857. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.1846-1857.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]