Abstract

We tested the hypothesis that γδ T cells are a component of an early immune response directed against preerythrocytic malaria parasites that are required for the induction of an effector αβ T-cell immune response generated by irradiated-sporozoite (irr-spz) immunization. γδ T-cell-deficient (TCRδ−/−) mice on a C57BL/6 background were challenged with Plasmodium yoelii (17XNL strain) sporozoites, and then liver parasite burden was measured at 42 h postchallenge. Liver parasite burden was measured by quantification of parasite-specific 18S rRNA in total liver RNA by quantitative-competitive reverse transcription-PCR and by an automated 5′ exonuclease PCR. Sporozoite-challenged TCRδ−/− mice showed a significant (P < 0.01) increase in liver parasite burden compared to similarly challenged immunocompetent mice. In support of this result, TCRδ−/− mice were also found to be more susceptible than immunocompetent mice to a sporozoite challenge when blood-stage parasitemia was used as a readout. A greater percentage of TCRδ−/− mice than of immunocompetent mice progressed to a blood-stage infection when challenged with five or fewer sporozoites (odds ratio = 2.35, P = 0.06). TCRδ−/− mice receiving a single irr-spz immunization showed percent inhibition of liver parasites comparable to that of immunized immunocompetent mice following a sporozoite challenge. These data support the hypothesis that γδ T cells are a component of early immunity directed against malaria preerythrocytic parasites and suggest that γδ T cells are not required for the induction of an effector αβ T-cell immune response generated by irr-spz immunization.

Malaria continues to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide despite the availability of effective antimalarial drugs and the proven effectiveness of insecticide-treated bed nets in decreasing mortality in children (18, 37). This contradiction demonstrates that current strategies for malaria control have been largely ineffective and strongly encourages the development of alternative measures to control malaria parasites. Along those lines, experimental data suggest that the development of a malaria vaccine is possible (2, 3, 5, 17, 20, 25, 26), and recent promising results have increased our optimism (32). The success of malaria vaccines hinges on a thorough understanding of the immune response directed against malaria parasites. Animal models of malaria infection have pointed out that the immune response generated against malaria parasites is very complex. In addition to a humoral component, a cell-mediated immune response involving the participation of numerous immune cell populations contributes to the control of infection (8). Therefore, an effective malaria vaccine will most likely require the induction of a multicomponent immune response (4). Further characterization of additional immune cells involved in immunity directed against malaria parasites combined with the identification of the antigens they recognize will facilitate the development of an effective malaria vaccine in humans.

Immunization with irradiated sporozoites (irr-spz) generates an immune response directed against preerythrocytic parasites that provides complete sterile protective immunity against a subsequent sporozoite challenge in mice, monkeys, and humans (2, 3, 5, 9, 20). Though impractical as a global vaccine, irr-spz immunization is an excellent model for understanding the generation of a protective immune response directed against preerythrocytic malaria parasites. Through the use of irr-spz immunization in rodent models of malaria infection, the immune effector cells that mediate protective immunity have been largely characterized (8). Antibodies, CD4+ and CD8+ αβ T cells, and γδ T cells have all been shown to contribute to the elimination of preerythrocytic parasites in irr-spz-immunized mice following a sporozoite challenge (23, 28), and CD8+ αβ T cells are required for protective immunity (24, 33). However, much less is known about the immune cells responsible for the induction of the effector immune response generated by irr-spz immunization.

γδ T cells are activated at an early phase of infection with intracellular or extracellular microbes and have been shown to produce cytokines associated with the appropriate T-helper response (7). γδ T cells have also been shown to be required for the induction of a T-helper 2-type immune response in a model of allergic airway inflammation (38). This suggests that γδ T cells may structure an effector immune response by affecting T-helper differentiation through the early production of cytokines (14). As CD4+ αβ+ T-helper cells are required for the induction of protective immunity generated by irr-spz immunization (34), it was of interest to determine if γδ T cells were involved in the induction of an effector immune response generated by irr-spz immunization. If so, the antigens recognized by γδ T cells would need to be incorporated in a subunit malaria vaccine designed to generate a comparable immune response to irr-spz immunization. We used the Plasmodium yoelii-C57BL/6 rodent model of malaria infection to test the hypothesis that γδ T cells are a component of an early immune response directed against preerythrocytic parasites that are required for the induction of an effector αβ T-cell-mediated immune response generated by irr-spz immunization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Female C57BL/6, Tcrd (γδ T-cell-deficient [TCRδ−/−]), and Tcrb (αβ T-cell-deficient [TCRβ−/−]) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Female Abb (Aβb−/−, class II-deficient) and B2M (β2m−/−, class I-deficient) mice were purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, N.Y.). All gene knockout mice were on a C57BL/6 background. All mice were maintained in a specific-pathogen-free facility in microisolator cages with autoclaved food and water.

Isolation of parasites from infected mosquitoes.

P. yoelii (17XNL strain) was used for all experiments. P. yoelii-infected Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes were a generous gift from Stephen Hoffman (Malaria Program, Naval Medical Research Center, Rockville, Md.). Sporozoites were isolated from infected mosquitoes by the method of Pacheco et al. (22) for liver parasite burden experiments. In experiments where blood-stage parasitemia was measured, sporozoites were isolated by dissection of salivary glands from infected mosquitoes. Sporozoites were then released from salivary glands by gentle grinding in a Potter-Elvehjem tissue grinder (VWR Scientific, South Plainfield, N.J.) with the addition of 1 ml of medium 199 (M199) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gemini, Calabasas, Calif.). Sporozoites were counted from a 1:10 dilution of the sporozoite suspension on an improved Neubauer hemacytometer with a Nikon Labphot T-2 phase-contrast microscope at 400× in phase 3 mode.

Quantitation of liver stages.

At 42 h following sporozoite challenge, livers were removed and P. yoelii liver-stage parasites were measured by quantification of parasite-specific 18S rRNA in total liver RNA as described elsewhere (1, 15, 36). Livers were homogenized in a Ten Broeck tissue grinder (VWR Scientific) in 4 ml of a denaturing solution (4 M guanidinium thiocyanate, 25 mM sodium citrate [pH 7], 0.5% sarcosyl) made fresh as a working solution (50 ml of denaturing solution, 0.2 M β-2-mercaptoethanol). Total liver RNA was then isolated from the liver homogenate by using the TRIzol reagent (Gibco/BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) as outlined in the product insert. One microgram of RNA was treated with 1.0 U of DNase I (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) and was then converted to cDNA by the Superscript preamplification system for first-strand cDNA synthesis (Gibco/BRL), using random hexamers in a 21-μl total volume as outlined in the product insert.

For quantification of parasite-specific rRNA by quantitative-competitive reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), parasite-specific rRNA was amplified from 5 μl of the cDNA mixture in a PCR master mix containing 46 μl of PCR Supermix (Gibco/BRL), 1 μl each of parasite-specific primers PB1 and PB2 (1) (12 μM, final concentration), 0.2 μl (1 U) of Taq DNA polymerase (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), and 1 μl of a known concentration of competitor plasmid. Then 35 cycles of amplification in a PCR Express (Hybaid, Middlesex, United Kingdom) thermocycler were performed under the following conditions: 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 1 min. An initial denaturation step at 94°C for 2 min and a terminal elongation step at 72°C for 10 min were also included. Target and competitor amplicons were resolved on ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gels and photographed by the Eagle Eye II still video system (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), and the image was stored electronically. Target-to-competitor ratios were then determined using the NIH Image software program. We performed a series of amplifications with different competitor concentrations and used target-to-competitor ratios from each competitor concentration in linear regression analysis to determine the competitor concentration where target and competitor amplicon ratios were equivalent. This concentration was used as a relative measure of liver parasite burden. Equal cDNA synthesis between samples was ensured by amplification of the housekeeping β-actin gene at PCR conditions below saturation.

Parasite-specific 18S rRNA was also measured in some experiments by a Taq Man (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) automated real-time PCR system (36). Briefly, cDNA transcribed from infected mouse liver total RNA was amplified simultaneously using specific primers and fluorescently labeled probes targeted to the 18S rRNA sequence of P. yoelii and the mouse glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) sequence. The threshold cycle, defined as the cycle at which the fluorescence exceeds 10 standard deviations above the starting fluorescence in the system, was converted to a DNA equivalent by reading against standard curves generated by amplifying 10-fold dilutions of plasmids containing the relevant target molecules. A measure of parasite burden was determined by calculating the ratio of the measured plasmid DNA equivalents for the 18S rRNA target (rDNA) over the GAPDH target.

Quantitation of blood stages.

Blood smears were air dried, fixed in methanol for 10 min at room temperature, air dried, and then stained with concentrated Giemsa (Sigma) stain for 5 min. Slides were then briefly washed with deionized water, air dried, and read on a Nikon Labphot T-2 light microscope at 1,000× under oil immersion.

irr-spz immunization.

P. yoelii-infected mosquitoes were irradiated (10,000 rads) in a 137Cs source irradiator, and then sporozoites were isolated by the method of Pacheco et al. (22); 7.5 × 104 irr-spz were then concentrated in 0.2 ml of M199 supplemented with 5% FBS and administered to mice via tail vein injection. As a mock immunization control, a second group of mice received 0.2 ml of M199 supplemented with 5% FBS alone. Seven days following immunization, mice were challenged with 105 sporozoites; 42 h postinfection, liver parasite burden was measured. Percent inhibition was calculated as 1− (immunized mean liver parasite burden/nonimmunized mean liver parasite burden) × 100.

Statistics.

The significance of changes in liver parasite burden were determined by comparison of mean liver parasite burdens between experimental groups of mice by a Student t test. The significance of susceptibility of TCRδ−/− and C57BL/6 mice to a sporozoite infection was compared by logistic regression.

RESULTS

Liver-stage quantitation by quantitative RT-PCR.

P. yoelii liver stages were measured by quantification of parasite-specific 18S rRNA in total liver RNA of sporozoite-infected mice. PCR amplification of parasite-specific rRNA was chosen over parasite-specific gene amplification from total liver DNA due to the greater abundance of parasite rRNA in total liver RNA than of parasite DNA in total liver DNA samples. An 18S rRNA sequence specific to both P. yoelii and P. berghei and not present in murine liver RNA (1) was the target of PCR amplification. Choice of this target sequence eliminated any false-positive amplification of murine sequences that might affect the quantification of liver parasites. We used two different quantitative methods to measure P. yoelii liver stages: quantitative-competitive RT-PCR (1, 15) and 5′ exonuclease PCR (Taq Man assay) (36).

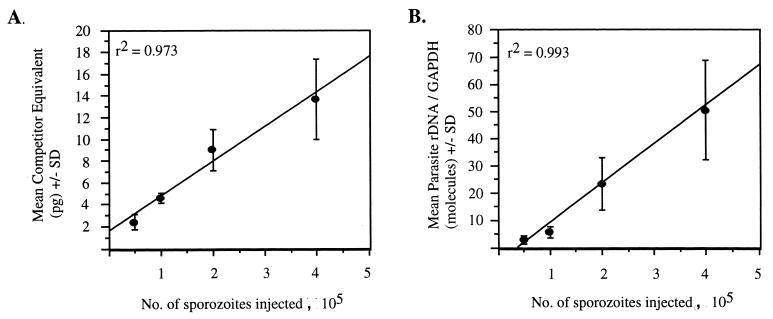

As changes in liver parasite burden were to be measured, it was imperative to choose a challenge dose that was within the linear range of detection by both assays. To determine this dose, groups of C57BL/6 mice were infected with increasing numbers of sporozoites (5.0 × 104 to 4.0 × 105) at twofold increments. At a time of peak parasite amplification in the liver, 42 h postinfection, mice were sacrificed and their livers were removed. Total liver RNA was isolated and converted to cDNA, and then parasite-specific 18S rDNA was measured by quantitative-competitive RT-PCR and the Taq Man assay. As shown in Fig. 1, both assays detected parasite rDNA in the livers of mice injected with the lowest challenge dose, 5.0 × 104 sporozoites. As the number of sporozoites was increased, a corresponding linear increase of parasite rDNA in mouse livers was measured by both assays. Based on this data, challenge doses of 5.0 × 104 or 1.0 × 105 were used for all subsequent experiments.

FIG. 1.

Quantification of P. yoelii 18S rRNA in total liver RNA by two unique assays. Groups of four to five mice were challenged with increasing numbers of sporozoites (5.0 × 104 to 4.0 × 105), and parasite rDNA was measured in total liver cDNA by quantitative-competitive RT-PCR (A) and by 5′ exonuclease PCR (Taq Man) (B). Error bars indicate 1 standard deviation of the mean.

Variability in sporozoite viability and/or infectivity between sporozoite isolations from different batches of infected mosquitoes.

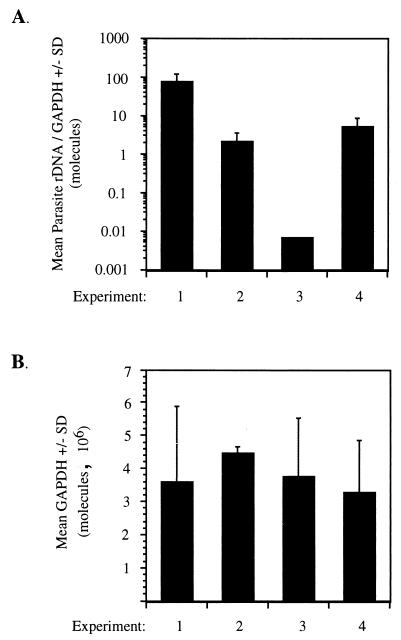

Since in vitro cultivation of sporozoites is currently not possible, sporozoites must be isolated from infected mosquitoes. To determine whether sporozoite viability and/or infectivity was variable between individual sporozoite isolations from different batches of infected mosquitoes, liver parasite burden was compared between four groups of mice, each challenged with 5.0 × 104 sporozoites. The challenge dose given in each group represented a separate sporozoite isolation from a different batch of infected mosquitoes. In the same cDNA synthesis reaction, total liver RNA samples from mice in all groups were individually converted to cDNA, using the same master mix of reagents. This was done to minimize differences in cDNA synthesis within individual samples of a group and between groups. Liver parasite burden was then measured by the Taq Man assay. As shown in Fig. 2A, liver parasite burden varied tremendously, ranging from 6.8 × 10−4 to 7.6 × 101 mean molecules of parasite rDNA/GAPDH, between sporozoite isolations from different batches of infected mosquitoes. These differences could not be attributed to unequal cDNA synthesis between groups of mice, as amplification of the housekeeping gene GAPDH was equivalent within and between groups of mice (Fig. 2B). These data indicated that sporozoite viability and/or infectivity was variable between sporozoite isolations from different batches of infected mosquitoes. Consequently, comparisons of liver parasite burden can be made only between experimental groups of mice, matched for age and sex, that were challenged with the same sporozoites isolated from the same batch of infected mosquitoes.

FIG. 2.

Variability in sporozoite viability and/or infectivity between sporozoites isolated from different batches of infected mosquitoes. Groups of mice were challenged with 5.0 × 104 sporozoites, and liver parasite burden was measured by Taq Man quantification of parasite-specific 18S rDNA at 42 h postinfection (A). Each experiment represents a group of mice challenged with sporozoites isolated from a different batch of infected mosquitoes. Equal cDNA synthesis between groups of mice was ensured by quantification of the housekeeping gene GAPDH (B). Experiment 1 represents data from immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice challenged with 5.0 × 104 sporozoites also displayed in Fig. 1. Experiment 3 represents data from immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice challenged with 5.0 × 104 sporozoites also displayed in experiment 1 of Table 1. Experiment 4 represents data from immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice challenged with 5.0 × 104 sporozoites also displayed in Fig. 4 and experiment 2 of Table 1.

Liver parasite burden in TCRδ−/− mice.

To test the hypothesis that γδ T cells are a component of early immunity directed against preerythrocytic parasites, C57BL/6 mice, rendered deficient in γδ T cells by a targeted mutation in the constant region of the delta chain (11), were challenged with sporozoites, and their liver parasite burden was measured and compared to that of similarly challenged immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice. In three independent experiments, TCRδ−/− mice were challenged with either 5.0 × 104 or 1.0 × 105 sporozoites. Mean liver parasite burden of TCRδ−/− mice was divided by the mean liver parasite burden of immunocompetent control mice to calculate the increase in liver parasite burden in TCRδ−/− mice. The significance of the fold increase in liver parasite burden was determined by a Student t test comparing the two means. As shown in Table 1, increases in liver parasite burden in TCRδ−/− mice ranged from 1.2- to 3.4-fold. However, in only one of three experiments was this increase statistically significant (P < 0.01).

TABLE 1.

Liver parasite burden in TCRδ−/− mice

| Expt | No. of sporozoites injected | Fold increase in liver parasite burdena | Significanceb | Liver parasite burden in immunocompetent micec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.0 × 104 | 3.4 | Yes | Low |

| 2 | 5.0 × 104 | 1.2 | No | Intermediate |

| 3 | 1.0 × 105 | 1.8 | No | High |

Calculated as mean liver parasite burden of TCRδ−/− mice divided by the mean liver parasite burden of similarly challenged C57BL/6 mice within the same experiment. Liver parasite burdens were measured by quantitative-competitive RT-PCR.

Determined by a Student t test comparing mean liver parasite burden of TCRδ−/− mice with mean liver parasite burden of C57BL/6 mice. “Yes” was defined as P < 0.05.

Determined by quantification of P. yoelii 18S rDNA by the Taq Man assay. Liver parasite burden, measured in mean molecules of parasite rDNA/GAPDH, from immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice from each experiment was as follows: experiment, 1, 0.007 ± 0.014; experiment 2, 5.22 ± 3.36; and experiment 3, 26.96 ± 28.26. Data shown for experiment 2 are also displayed in Fig. 4. Data shown for experiment 3 are also displayed in Fig. 3.

As shown in Fig. 2, sporozoite viability and/or infectivity varies tremendously between sporozoite isolations from different batches of infected mosquitoes. Consequently, equivalent parasite challenges could not be reproduced between experiments. Therefore, it was of interest to determine if the parasite challenge in experiment 1, where a significant increase in liver parasite burden was observed in TCRδ−/− mice, was equivalent to the parasite challenge given in experiment 2, where no significant increase was detected. Challenge doses of 5.0 × 104 sporozoites were used in both experiments. To address this question, total liver RNA samples from sporozoite-challenged immunocompetent control mice from experiments 1, 2, and 3 were converted to cDNA at the same time, using the same master mix for the cDNA synthesis reaction. This ensured equal cDNA synthesis between individual samples and was confirmed by the amplification of the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Liver parasite burden was then simultaneously measured from each sample by the Taq Man assay. Though mice in experiments 1 and 2 received an equivalent number of sporozoites, liver parasite burden was 3 orders of magnitude less in experiment 1 than in experiment 2. This clearly indicates that the parasite challenge used in experiment 1 was much lower than the parasite challenge used in experiment 2. These data suggest that the contribution of γδ T cells in eliminating preerythrocytic parasites can be discerned only at low parasite challenges.

Sporozoite infectivity in TCRδ−/− mice.

To further confirm the contribution of γδ T cells in the early immune response directed against preerythrocytic malaria parasites, blood-stage parasitemia was also used as a readout to determine the susceptibility of TCRδ−/− mice and C57BL/6 mice to a sporozoite challenge. The preerythrocytic stage of P. yoelii takes 48 h in mice (12), and the complete elimination of preerythrocytic parasites prevents progression to the blood-stage infection. If γδ T cells contributed to the elimination of preerythrocytic parasites in naive mice, as was suggested by the increased liver parasite burden observed in TCRδ−/− mice, TCRδ−/− mice should also be more susceptible to a sporozoite challenge.

To determine the susceptibility of TCRδ−/− mice to a sporozoite challenge, groups of TCRδ−/− mice and C57BL/6 mice were challenged with 50, 25, 10, 5, or 1 sporozoite, and the number of mice that progressed to a blood-stage infection was measured. Two independent experiments were performed. A blood-stage infection was defined as the presence of infected erythrocytes, visualized in Giemsa-stained blood smears, by day 12 following infection. A blood smear was taken from each mouse within a sporozoite challenge group. Blood smears were taken on days 3 to 7, 9, 11, and 13 postchallenge in experiment 1 and on days 7, 9, and 12 postchallenge in experiment 2. In both experiments, mice that progressed to a blood-stage infection in all challenge groups were positive for infected erythrocytes by day 9 (range, 4 to 9 days) following challenge. Due to an error, blood smears from the 25-sporozoite challenge group in experiment 2 were unable to be read on day 12. Blood smears were read by light microscopy at 1,000× magnification under oil immersion. A negative blood smear was defined as the absence of infected erythrocytes in a minimum of 20 1,000× fields. A field contained 247 ± 94 (n = 10) erythrocytes. Therefore, the sensitivity of detection of infected erythrocytes was less than 0.03% parasitemia.

As shown in Table 2, 100% of both TCRδ−/− and C57BL/6 mice were infected when challenged with 50 sporozoites, and similar percentages of mice were infected between the two strains at challenge doses of 25 and 10 sporozoites. However, 75% of TCRδ−/− mice were infected when challenged with five sporozoites, while only 42% of C57BL/6 mice became infected. Similarly, 30% of TCRδ−/− mice but only 15% of C57BL/6 mice became infected when challenged with one sporozoite.

TABLE 2.

Susceptibility of TCRδ−/− mice and immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice to a sporozoite challenge

| No. of sporozoites injected | No. of mice infecteda/no. challenged

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCRδ−/−

|

C57BL/6

|

|||||

| Expt 1 | Expt 2 | Total (%) | Expt 1 | Expt 2 | Total (%) | |

| 50 | 6/6 | ND | 6/6 (100) | 6/6 | ND | 6/6 (100) |

| 25 | 6/6 | 5/10 | 11/16 (68) | 4/5 | 10/15 | 14/20 (70) |

| 10 | 4/6 | ND | 4/6 (67) | 4/5 | ND | 4/5 (80) |

| Total (%) | 21/28 (75) | 24/31 (77) | ||||

| 5 | 4/6 | 8/10 | 12/16 (75) | 1/6 | 10/20 | 11/26 (42) |

| 1 | ND | 3/10 | 3/10 (30) | ND | 3/20 | 3/20 (15) |

| 0.2 | ND | 1/10 | 1/10 (10) | ND | 1/13 | 1/13 (7) |

| Total (%) | 16/36 (44) | 14/59 (24) | ||||

“Infection” was defined as the presence of infected erythrocytes in Giemsa-stained blood smears by day 12 following sporozoite challenge. ND, not determined.

Differences between the two strains of mice were compared for statistical significance by logistic regression. The number of mice that became infected in either strain varied directly with the number of sporozoites injected. As shown in Table 2, as the challenge dose was decreased, the number of mice infected in either strain was also decreased. Logistic regression compares the statistical significance of the difference in this trend between the two strains of mice. By this analysis, TCRδ−/− mice were found to be twofold more susceptible (odds ratio = 2.35, P = 0.06) to a sporozoite challenge with five or fewer sporozoites. The trend in these data may also be described by calculating the infectious dose where half the mice became infected (the sporozoite ID50). The sporozoite ID50 was calculated from an equation of the trend line derived from scatter plots comparing the percentage of infected mice by challenges with 5 sporozoites, 1 sporozoite, and 0.2 sporozoite for each mouse strain. The sporozoite ID50 for C57BL/6 mice was six sporozoites (y = 7.12x + 6.625, r2 = 0.9959), while the sporozoite ID50 for TCRδ−/− mice was three sporozoites (y = 12.80x + 11.875, r2 = 0.978). These data suggest that TCRδ−/− mice are more susceptible to a sporozoite challenge.

Liver parasite burden in TCRδ−/− mice receiving a single irr-spz immunization.

TCRδ−/− and C57BL/6 mice were given a single immunization with 7.5 × 104 irr-spz and challenged with 105 sporozoites 7 days later. Following sporozoite challenge, liver parasite burden was measured. A single irr-spz immunization was chosen over multiple irr-spz immunizations to minimize the possible activation of other immune cells, e.g., B cells, that might mask the early contribution of γδ T cells to the induction of an αβ T-cell effector immune response. A single immunization does not induce high antibody titers against sporozoites (29).

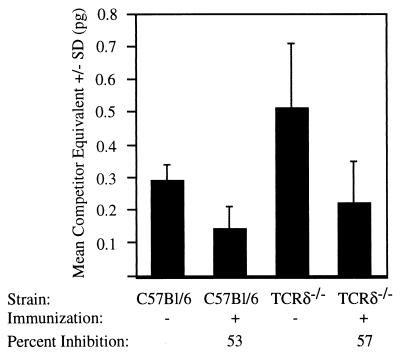

As shown in Fig. 3, C57BL/6 mice receiving a single irr-spz immunization showed a significant (P < 0.02) decrease in liver parasite burden following a sporozoite challenge compared to similarly challenged nonimmunized C57BL/6 mice. Immunized TCRδ−/− mice showed elevated liver parasite burden compared to immunized C57BL/6 mice but also showed a significant decrease in liver parasite burden (P = 0.05) compared to similarly challenged nonimmunized TCRδ−/− mice. Immunization with irr-spz reduced the liver parasite burden by equivalent percentages (53 and 57%) in C57BL/6 and TCRδ−/− mice, respectively. This suggests that γδ T cells do not contribute to the induction of an effector αβ T-cell immune response generated by irr-spz immunization. In the presence or the absence of γδ T cells, irr-spz immunization generates an effector αβ T-cell immune response which reduces liver parasite burden following a sporozoite challenge.

FIG. 3.

Liver parasite burden in γδ T-cell-deficient mice receiving a single irr-spz immunization. TCRδ−/− and C57BL/6 mice received a single irr-spz immunization with 7.5 × 104 sporozoites and were challenged with 105 sporozoites 7 days later. As a mock immunization control, some groups of mice were given an equivalent volume of medium alone. Liver parasite burden was measured by quantitative-competitive RT-PCR amplification of parasite-specific 18S rDNA in total liver cDNA at 42 h postinfection. Error bars indicate 1 standard deviation of the mean.

Liver parasite burden in αβ T-cell-deficient mice.

Data from the previous experiments suggested that the functional role of γδ T cells in the preerythrocytic immune response could be as an early-responding immune cell population responsible for controlling initial preerythrocytic parasitemia while an effector immune response develops. To determine whether this role was unique to γδ T cells, the contribution of αβ T cells in the early immune response directed against preerythrocytic parasites was also evaluated.

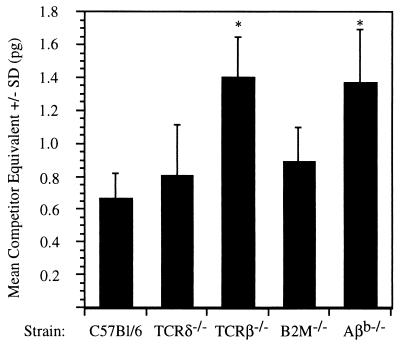

TCRβ−/− mice were challenged with 5.0 × 104 sporozoites, and their liver parasite burden was measured by quantitative-competitive RT-PCR and compared to the liver parasite burden of immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice. As shown in Fig. 4, TCRβ−/− mice showed a significant (P < 0.01) twofold increase in liver parasite burden compared to similarly challenged C57BL/6 mice. TCRδ−/− mice showed a minor but not significant increase in liver parasite burden in this experiment. To determine the probable subset of αβ T cells contributing to the early elimination of preerythrocytic parasites, B2M−/− mice that lack CD8+ αβ T cells and major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC I) presentation and Aβb−/− mice that lack CD4+ αβ T cells and MHC II presentation were also challenged. While B2M−/− mice did not show a significant increase in liver parasite burden compared to similarly challenged C57BL/6 mice, MHC II-deficient mice showed a significant (P = 0.01) twofold increase in liver parasite burden that was comparable to the increase seen in TCRβ−/− mice.

FIG. 4.

Increased liver parasite burden in αβ T-cell-deficient mice. Groups of five C57BL/6, TCRδ−/−, TCRβ−/−, class I-deficient (B2M−/−), and class II-deficient (Aβb−/−) mice were challenged with 5.0 × 104 sporozoites, and liver parasite burden was measured by quantitative-competitive RT-PCR of parasite-specific 18S rDNA. Error bars indicate 1 standard deviation of the mean. ∗, significant increase (P < 0.05) in liver parasite burden compared to the liver parasite burden of C57BL/6 mice.

These data suggest that CD4+ αβ T cells also contribute to an early immune response directed against preerythrocytic parasites. In addition, TCRβ−/− mice showed a significant increase in liver parasite burden at a parasite challenge dose where the contribution of γδ T cells could not be discerned. This suggests that the contribution of γδ T cells in eliminating preerythrocytic parasites is secondary to the contribution of CD4+ αβ T cells.

DISCUSSION

We have observed that γδ T-cell-deficient mice show increased liver parasite burden compared to similarly challenged immunocompetent mice at 42 h postinfection. In addition, γδ T-cell-deficient mice were found to be more susceptible than immunocompetent mice to a challenge with fewer than five sporozoites. Both observations suggest that γδ T cells contribute to the immune response directed against preerythrocytic malaria parasites at a very early phase of the P. yoelii infection. Though evidence from other models of infection (7) and allergic inflammation (38) has suggested that early-responding γδ T cells may play an important role in the induction of an appropriate T-helper response, we have not observed a requirement for γδ T cells in the induction of T-helper-dependent (34) immunity generated by irr-spz immunization. Both γδ T-cell-deficient mice and immunocompetent mice given a single irr-spz immunization showed similar inhibition of preerythrocytic parasites following a sporozoite challenge.

Our data also show that CD4+ αβ T cells contribute to the early immune response directed against preerythrocytic parasites. This finding was surprising and is in contrast to the distinct roles that αβ and γδ T cells play in peritoneal Listeria monocytogenes infections (10). Like P. yoelii, Listeria monocytogenes is an intracellular pathogen. However, in Listeria infections, γδ T cells show increased kinetics of activation (10, 13) and infiltration (21) over αβ T cells. As γδ T cells cannot alone resolve the infection (10), it has been suggested that γδ T cells control the primary infection whereas αβ T cells are activated and expanded to resolve the infection. The early contribution of CD4+ αβ T cells in P. yoelii infections might be explained by unique antigen presentation resulting from the complex life cycle of the parasite. Kupffer cells, resident macrophages of the liver, phagocytose sporozoites (31) and may present parasite antigens. In addition, indirect evidence suggests that hepatocytes may present parasite antigens via MHC II (27). Presentation of parasite antigens by these antigen-presenting cells may activate CD4+ αβ T cells with increased kinetics.

In addition, the sporozoite challenge dose used in this experiment resulted in a liver parasite burden much higher than that observed in previous experiments. At this high liver parasite burden, the contribution of αβ T cells was observed whereas the contribution of γδ T cells could not be discerned. This may suggest that the contribution of αβ T cells in the early elimination of preerythrocytic parasites may be greater than the contribution of γδ T cells. A strong contribution of αβ T cells in eliminating preerythrocytic parasites in naive mice might explain why it was so difficult to show the contribution of γδ T cells in eliminating preerythrocytic parasites under certain challenge conditions. TCRδ−/− mice undergo normal development of αβ T cells (11). Consequently, by comparing the liver parasite burden of TCRδ−/− mice to the liver parasite burden of immunocompetent mice, the contribution of γδ T cells in eliminating preerythrocytic parasites must be distinguished from the strong contribution of αβ T cells in eliminating preerythrocytic parasites seen in both TCRδ−/− mice and immunocompetent mice.

In our experiments, sporozoite viability and/or infectivity varied tremendously between sporozoites isolated from different batches of infected mosquitoes. Consequently, sporozoite counts were not an effective measurement of an equivalent parasite challenge. This was problematic, as it was not possible to reproduce experiments with equivalent parasite challenge doses. Only one of three experiments in which liver parasite burden was measured showed a significant increase in liver parasite burden in γδ T-cell-deficient mice. However, an association was seen between the level of liver parasite burden in immunocompetent mice, a quantitative measurement of the parasite challenge, and increased liver parasite burden in TCRδ−/− mice. In the experiment where γδ T-cell-deficient mice showed greater liver parasite burden than control mice, the parasite challenge was 3 to 4 orders of magnitude lower than the parasite challenge in the two subsequent experiments where no increase in liver parasite burden in TCRδ−/− was detected. Therefore, the inability to reproduce the increased liver parasite burden in TCRδ−/− mice may have been due to the magnitude of the parasite challenge dose used in subsequent experiments. A similar effect of parasite challenge dose was also observed in experiments where blood-stage parasitemia was used as a readout to determine the susceptibility of γδ T-cell-deficient mice and immunocompetent mice to a sporozoite challenge. The increased susceptibility of γδ T-cell-deficient mice to a sporozoite challenge was also observed only at very low challenge doses.

Whether γδ T cells act on sporozoites or liver parasites remains to be determined. γδ T cells have been shown to recognize antigens directly and independent of MHC restriction (16), similarly to B cells, and were shown to directly inhibit the development of Plasmodium falciparum in vitro by a proposed direct recognition of merozoites (6). Therefore, γδ T cells may recognize sporozoites in peripheral blood and inactivate them. However, considering the small number of γδ T cells in the peripheral blood of mice and the fact that sporozoites are in the bloodstream for a very short period of time, a chance interaction between sporozoites and parasite-specific γδ T cells seems highly improbable.

Another possibility is that γδ T cells exert their antiparasitic activity against the infected hepatocyte. Data suggest that infected hepatocytes present parasite antigens via MHC I (35) and possibly MHC II (27), making them an ideal target for immune effector cells. The γδ T-cell clone 291-H4, derived from irr-spz-immunized αβ T-cell-deficient mice, exhibited antiparasitic activity against malaria preerythrocytic parasites when transferred into naive mice that were subsequently challenged with sporozoites (28, 30). We have also shown that this clone independently inhibits the development of liver-stage parasites in sporozoite-infected primary hepatocyte cultures (data not shown). This indicates that 291-H4 directly eliminates liver stage parasites or inhibits parasite development within hepatocytes. Therefore, γδ T cells may decrease liver parasite burden in vivo by acting on liver stages directly.

A third possibility that could also explain increased liver parasite burden in TCRδ−/− mice is impaired monocyte function. Macrophages from TCRδ−/− mice were impaired in the ability to produce tumor necrosis factor alpha when stimulated with lipopolysaccharide in vitro (19). This suggests that γδ T cells regulate macrophage function. Kupffer cells are a resident macrophage population in the liver, and their depletion results in increased liver parasite burden when naive rats are challenged with P. berghei sporozoites (31). If γδ T cells regulate Kupffer cells, the impairment of Kupffer cell function could also explain the observed increased liver parasite burden in TCRδ−/− mice. It would also explain the observation that naive BALB/c mice challenged with P. yoelii sporozoites show little to no cellular infiltration of the liver during parasite development in hepatocytes (12), as parasite elimination by Kupffer cells occurs prior to the infection of hepatocytes.

In conclusion, our data support a role of γδ T cells in the early elimination or inhibited development of preerythrocytic parasites. Previously, Tsuji et al. (28) showed that γδ T cells contribute to the elimination of preerythrocytic parasites in irr-spz-immunized αβ T-cell-deficient mice. Based on these findings combined with the data presented here, we suggest that γδ T cells are an immune population induced by irr-spz immunization that is capable of decreasing preerythrocytic parasite burden and may represent a significant effector population that can be induced by vaccination.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Robert Freund for critical review of the manuscript and Shui Cao for excellent technical assistance.

This work was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants AI 17828 and AI 43006) and the Naval Medical Research and Development Command (work units STO F 6.161102AA0101BFX, STO F 6.262787A00101EFX, and STEP C611102A0101BCX).

REFERENCES

- 1.Briones M R S, Tsuji M, Nussenzweig V. The large difference in infectivity for mice of Plasmodium berghei and Plasmodium yoelii sporozoites can not be correlated with their ability to enter hepatocytes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;77:7–17. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02574-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clyde D F, McCarthy V C, Miller R M, Hornick R B. Specificity of protection of man immunized against sporozoite induced falciparum malaria. Am J Med Sci. 1973;266:398–403. doi: 10.1097/00000441-197312000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clyde D F, Most H, McCarthy V C, Vanderberg J P. Immunization of man against sporozoite-induced falciparum malaria. Am J Med Sci. 1973;266:169–177. doi: 10.1097/00000441-197309000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doolan D L, Hoffman S L. Multi-gene vaccination against malaria: a multistage, multi-immune response approach. Parasitol Today. 1997;13:171–178. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)01040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edelman R, Hoffman S L, Davis J R, Beier M, Sztein M B, Lesonsky G, Herrington D A, Eddy H A, Hollingdale M R, Gordon D M, Clyde D F. Long-term persistence of sterile immunity in a volunteer immunized with X-irradiated Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1066–1070. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.4.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elloso M M, van der Heyde H C, vande Waa J A, Manning D D, Weidanz W P. Inhibition of Plasmodium falciparum in vitro by human γδ T-cells. J Immunol. 1994;153:1187–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrick D A, Schrenzel M D, Mulvania T, Hsieh B, Ferlin W G, Lepper H. Differential production of interferonγ and interleukin-4 in response to Th1 and Th2 stimulating pathogens by γδ T-cells in vivo. Nature. 1995;373:255–257. doi: 10.1038/373255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Good M F, Doolan D L. Immune effector mechanisms in malaria. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:412–419. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(99)80069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gwadz R W, Cochrane A H, Nussenzweig V, Nussenzweig R S. Preliminary studies on vaccination of rhesus monkeys with irradiated sporozoites of Plasmodium knowlesi and characterization of surface antigens of these parasites. Bull W H O. 1979;57(Suppl. 1):165–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiromatsu K, Yoshikai Y, Matsuzaki G, Ohga S, Muramori K, Matsumoto K, Bluestone J A, Nomoto K. A protective role of γ/δ T-cells in primary infection with Listeria monocytogenes in mice. J Exp Med. 1992;175:49–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Itohara S, Mombaerts P, Lafaille J, Iacomini J, Nelson A, Clark A R, Hooper M L, Farr A, Tonegawa S. T cell receptor delta gene mutant mice: independent generation of alpha and beta T cells and programmed rearrangements of gamma delta TCR genes. Cell. 1993;72:337–348. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan Z M, Vanderberg J P. Role of host cellular response in differential susceptibility of nonimmunized BALB/c mice to Plasmodium berghei and Plasmodium yoelii sporozoites. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2529–2534. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2529-2534.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lahn M, Kalatrdi H, Mittelstadt P, Pflum E, Vollmer M, O'Brien R, Born W. Early preferential stimulation of γδ T-cells by TNF-α. J Immunol. 1998;160:5221–5230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mak T W, Ferrick D A. The γδ T-cell bridge: linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat Med. 1998;4:764–765. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKenna, K. C., and M. R. S. Briones. Liver-stage quantitation by competitive RT-PCR. In D. L. Doolan (ed.), Malaria methods and protocols, methods in molecular medicine, in press. Humana Press, Totowa, N.J. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Morita C T, Beckman E M, Buckowski J F, Tanaka Y, Band H, Bloom B R, Golan D E, Brenner M B. Direct presentation of nonpeptide prenyl pyrophosphate antigens to human γδ T-cells. Immunity. 1995;3:495–507. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulligan H W, Russell P, Mohan B. Active immunization of fowls against Plasmodium gallinaceum by injections of killed homologous sporozoites. J Malar Inst India. 1941;4:25. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nchinda T C. Malaria: a reemerging disease in Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:398–403. doi: 10.3201/eid0403.980313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishimura H, Emoto M, Hiromatsu K, Yamamoto S, Matsuura K, Gomi H, Ikeda T, Itohara S, Yoshikai Y. The role of gamma delta T-cells in priming macrophages to produce tumor necrosis factor alpha. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1465–1468. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nussenzweig R S, Vanderberg J P, Most H, Orton C. Specificity of protective immunity produced by X-irradiated Plasmodium berghei sporozoites. Nature. 1969;222:488–489. doi: 10.1038/222488a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohga S, Yoshikai Y, Takeda T, Hiromatsu K, Nomoto K. Sequential appearance of γ/δ and α/β T-cells in the peritoneal cavity during an i.p. infection with Listeria monocytogenes. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:533–538. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pacheco N D, Strome C P, Mitchell F, Bawden M P, Beaudoin R L. Rapid large scale isolation of Plasmodium berghei sporozoites from infected mosquitoes. J Parasitol. 1979;65:414–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez M, Nussenzweig R S, Zavala F. The relative contribution of antibodies, CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells to sporozoite induced protection against malaria. Immunology. 1993;80:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schofield L, Villaquiran J, Ferreira A, Schellekens H, Nussenzweig R S, Nussenzweig V. γInterferon, CD8+ T-cells and antibodies required for immunity to malaria sporozoites. Nature. 1987;330:664–666. doi: 10.1038/330664a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stoute J A, Slaoui M, Heppner D G, Monin P, Kester K E, Desmons P, Wellde B T, Garcon N, Kryzych U, Marchand M, Ballou W R, Cohen J D. A preliminary evaluation of a recombinant circumsporozoite protein vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:86–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701093360202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stoute J A, Kester K E, Krych U, Wellde B T, Hall T, White K, Glenn G, Ockenhouse C F, Garcon N, Schwenk R, Lanar D E, Sun P, Momin P, Wirtz R A, Golenda C, Slaoui M, Wortmann G, Holland C, Dowler M, Cohen J, Ballou W R. Long-term efficacy and immune responses following immunization with the RTS, S malaria vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1139–1144. doi: 10.1086/515657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsuji M, Romero P, Nussenzweig R S, Zavala F. CD4+ cytolytic T cell clone confers protection against murine malaria. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1353–1357. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.5.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsuji M, Mombaerts P, Lefrancois L, Nussenzweig R S, Zavala F, Tonegawa S. γδ T-cells contribute to immunity against the liver stages of malaria in γδ T-cell deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:345–349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsuji M, Miyahira Y, Nussenzweig R S, Aguet M, Reichel M, Zavala F. Development of antimalarial immunity in mice lacking IFNγ receptor. J Immunol. 1995;154:5338–5344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsuji M, Eyster C L, O'Brien R L, Born W K, Bapna M, Reichel M, Nussenzweig R S, Zavala F. Phenotypic and functional properties of murine γδ T-cell clones derived from malaria immunized αβ T cell-deficient mice. Int Immunol. 1996;8:359–366. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vrenden S G S, Sauerwein R W, Verhave J P, van Rooijen N, Meuwissen J H E, van der Broeck M F. Kupffer cell elimination enhances development of liver schizonts of Plasmodium berghei in rats. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1936–1939. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1936-1939.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang R, Doolan D L, Le T P, Hedstrom R C, Coonan K M, Charoenvit Y, Jones T R, Hobart P, Margalith M, Ng J, Weiss W R, Sedegah M, de Taisne C, Norman J A, Hoffman S L. Induction of antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in humans by a malaria DNA vaccine. Science. 1998;282:476–480. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5388.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss W, Sedegah M, Beudoin R L, Miller L H, Good M F. CD8+ T-cells (cytotoxic/suppressors) are required for protection in mice immunized with malaria sporozoites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:573–576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss W R, Sedegah M, Berzofsky J A, Hoffman S L. The role of CD4+ T-cells in immunity to malaria sporozoites. J Immunol. 1993;151:2690–2698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White K L, Snyder H L, Krzych U. MHC class I-dependent presentation of exoerythrocytic antigens to CD8+ T lymphocytes is required for protective immunity against Plasmodium berghei. J Immunol. 1996;156:3374–3381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witney, A., and D. Carucci. Automated quantitation of liver-stages. In D. L. Doolan (ed.), Malaria methods and protocols, methods in molecular medicine, in press. Humana Press, Totowa, N.J.

- 37.World Health Organization. World malaria situation in 1994. Weekly Epidemiol Rec. 1997;72:269–274. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zuany-Amorim C, Ruffie C, Haile S, Vargaftig B B, Pereira P, Pretolani M. Requirement for γδ T-cells in allergic airway inflammation. Science. 1998;280:1265–1267. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5367.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]