Abstract

Shiga toxin 2 (Stx2) is produced by enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) and is known as the major virulence factor of EHEC. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of Stx2 on (i) maternal lethality, (ii) fetuses, (iii) delivery period, and (iv) maternal behavior after delivery. Timed pregnant ICR mice were injected intravenously with Stx2 on day 5 of pregnancy (early stage) or on day 15 (late stage). In early-stage experiments, the number of normal fetuses of mice injected with Stx2 was significantly lower than that of control mice. In late-stage experiments, mothers injected with Stx2 delivered normal numbers of neonates, but could not take care of them. The lethal doses of Stx2 were not different for pregnant and nonpregnant female mice at either stage. We conclude that Stx2 is toxic to the fetus in early pregnancy and affects maternal puerperal behavior in late pregnancy.

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) is known as the etiological agent of diarrhea associated with hemorrhagic colitis (17), hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) (8, 9), and acute encephalopathy (15) in humans. The largest outbreak of EHEC infection threatened the Japanese population in the summer of 1996. The number of patients reached more than 10,000, and the outbreak resulted in 12 deaths. Most of the patients were schoolchildren, and the infection was thought to be transmitted through school lunches. The major virulence factor of EHEC is Shiga toxin (Stx), which has two major subtypes, Stx1 and Stx2. Stx1 and Stx2 inhibit protein synthesis of eukaryotic cells in the same way as Stx produced by Shigella dysenteriae (7). Stx1 is virtually identical to Stx produced by Shigella dysenteriae, while Stx2 shows 56% homology to Stx1 at the amino acid sequence level. Stx1 and Stx2 have been known to bind the glycolipid globotriosylceramide (Gb3) as functional receptors (13). Stxs have been shown to be directly toxic to human vascular endothelial cells in vitro (20). Lingwood (12) reported that the reason why children are most susceptible to infection with EHEC is that Stx binding is found in renal glomeruli only in children, but not in adults.

Maternal infections have been linked to several adverse pregnancy outcomes in humans, including fetal anomalies, intrauterine fetal death, premature labor, premature rupture of the membranes, and abortion (2, 4, 5, 14). Among bacteria, Treponema pallidum and Listeria monocytogenes are well known to cause fetal illness and damage when mothers contract these infections during pregnancy. T. pallidum causes transplacental infection after completion of placental development. Treponemes cross the placenta and cause fetal infection and subsequent tissue damage. L. monocytogenes is a causative agent of food-borne infections (e.g., meningitis and sepsis in humans). When it infects pregnant women, it may induce fetal sepsis and stillbirth, and is the only known causative agent of food poisoning to cause fetal death or abortion in humans.

There is only one case report of EHEC infection in pregnancy (1). Although the patient in question delivered a normal baby at term, it has not been established whether EHEC infection affects pregnancy. In this study, we evaluated the effects of Stx2 on maternal lethality, fetal status, delivery time, and puerperal behavior by injecting Stx2 intravenously into pregnant mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Male and female ICR mice purchased from SLC Experimental Animal Co., Ltd., Shizuoka, Japan, were used throughout these studies for the production of timed pregnant females. Mice were allowed free access to food and water before and during experimentation and were exposed to 12-h-light and 12-h-dark cycles. Mice were bred (one female to one male) for a period of 16 h. The appearance of a vaginal plug was used as a sign of copulation and was termed day 0 of pregnancy. After treatment, the female mice were housed in groups of five each.

Purification of Stx2.

Stx2 was purified from a culture supernatant of E. coli C600 (933W) by the method described by Yutsudo et al. (22). The biological activity of the Stx2 was monitored by cytotoxicity on Vero cells to determine the 50% cytotoxic dose (CD50). The CD50 was 10−6 μg of protein, in which one CD50 is defined as the amount of Stx2 activity required to produce a 50% cytopathic effect in a Vero cell monolayer after 3 days of incubation at 37°C. Stx2 was revealed to be lipopolysaccharide (LPS) free by toxicolor test and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis silver staining.

Experimental design.

In order to examine the effects of Stx2 on maternal lethality, timed pregnant mice were injected with Stx2 (0, 3.13, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, or 100 pg/g of body weight) intravenously on day 5 (early stage) or day 15 (late stage) of pregnancy and were observed until 7 days after delivery. The 50% lethal dose (LD50) of Stx2 for mice was calculated by the Reed-Muench method.

Pregnant mice were injected with less than a lethal dose of Stx2 (0, 3.13, or 6.25 pg/g of body weight) on day 5 to examine the effects of Stx2 on the fetus in the early stage. On day 18 of pregnancy, before the onset of labor, the mice were sacrificed under ether anesthesia to count the numbers of normal fetuses and fetoplacental resorptions and to obtain samples of uteri.

In order to examine the effects of Stx2 on the delivery period and maternal puerperal behavior, timed pregnant mice were injected with Stx2 (0, 6.25, 12.5, or 25 pg/g of body weight) intravenously on day 15 of pregnancy, when placental development is complete (late stage). We recorded the numbers of surviving neonates and puerperal behavior, especially disposition of the placenta, building a nest of neonates and nursing. In a separate experiment, we injected 12.5 pg of either Stx2 or vehicle per g into mice on day 15 of pregnancy, and the mother-neonate pairs were exchanged between control and Stx2-injected groups after delivery. The numbers of neonates were observed for a week.

Pathological study.

To determine the time course of the pathological changes of fetoplacental resorption, 15 mice were injected with 3.13 or 6.25 pg of Stx2 per g on day 7 of pregnancy, and 3 mice each were sacrificed on days 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12.

To detect the initial lesion of fetoplacental resorption, mice were injected with 20, 100, or 200 pg of Stx2 per g on day 7 of pregnancy, and three mice of each group were sacrificed 6, 12, and 24 h after injection to obtain uterine samples. The samples were examined by light microscopy after routine processing of paraffin sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) was performed on paraffin sections (ApopTag peroxidase kit; Oncor, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.). Briefly, paraffin sections were deparaffinized, treated with proteinase K (20 μg/ml; DAKO, Tokyo, Japan), and dipped in 3% hydrogen peroxide to quench endogenous peroxides. Next, digoxigenin-labeled dUTP was bound to the 3′-OH ends of DNA by TdT. Subsequently, sections were exposed to peroxidase-conjugated antidigoxigenin antibody. Development of color was performed with a diaminobenzidine substrate solution containing hydrogen peroxide. Finally, the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and observed by light microscopy.

Statistical analysis.

Comparison of means was performed by analysis of variance with the statistical software package StatView 4.0 (Abacus Concepts). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Effects of Stx2 injection in the early stage of pregnancy. (i) Effects on maternal lethality.

To investigate the effects of Stx2 on maternal lethality, mice were injected with Stx2 on day 5 of pregnancy and observed for maternal lethality until 7 days after delivery. The LD50s of Stx2 were 25.0 pg/g of body weight for ICR female nonpregnant mice and 24.4 pg/g in the early stage of pregnancy (not significant [Table 1]).

TABLE 1.

Effects of Stx2 on lethality for mice of Stx2 injected on day 5 or 15 of pregnancy

| Dose of Stx2 (pg/g of body wt) | No. of deaths/no. of mice injected with Stx2 on:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 5

|

Day 15

|

|||

| Nonpregnant | Pregnant | Nonpregnant | Pregnant | |

| 0 | 0/6 | 0/3 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| 3.13 | 0/6 | 0/4 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| 6.25 | 0/6 | 0/4 | 0/5 | 0/6 |

| 12.5 | 0/8 | 1/3 | 1/6 | 1/6 |

| 25 | 4/8 | 3/4 | 3/6 | 3/6 |

| 50 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 3/5 | 4/5 |

| 100 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| LD50a (pg/g) | 25.0 | 24.4 | 25.0 | 25.0 |

Calculated by the Reed-Muench method.

(ii) Effects on fetus and delivery period.

To investigate the effects of Stx2 on the fetus, mice were injected with less than a lethal dose of Stx2 on day 5 of pregnancy. Mice were sacrificed on day 18 to observe intrauterine fetal growth (Table 2). The numbers of normally grown fetuses of mice injected with 3.13 and 6.25 pg of Stx2 per g were 4.6 ± 3.6 and 3.0 ± 4.0, respectively, and they were significantly lower than those of control mice (14.8 ± 1.5; P < 0.005). There were many fetoplacental resorptions in Stx2-injected pregnant mice (Fig. 1). The numbers of fetoplacental resorptions in Stx2-injected mice (11.1 ± 3.8 and 10.9 ± 4.5, respectively) were significantly higher than that of control mice (0.2 ± 0.4) (P < 0.005). Although the numbers of fetuses were significantly lower in Stx2-treated pregnant mice, some neonates were born at term (18.9 ± 0.4 days of pregnancy) without macroscopic malformation and grew well after delivery.

TABLE 2.

Effects of Stx2 on fetal numbers in pregnant mice with Stx2 injected on day 5 of pregnancy

| Dose of Stx2 (pg/g of body wt) | No. of pregnant mice | No. of fetuses (mean ± SD) | No. of resorptions (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 14.8 ± 1.5 | 0.2 ± 0.4 |

| 3.13 | 7 | 4.6 ± 3.6a | 11.1 ± 3.8a |

| 6.25 | 7 | 3.0 ± 4.0a | 10.9 ± 4.5a |

P < 0.005 versus control.

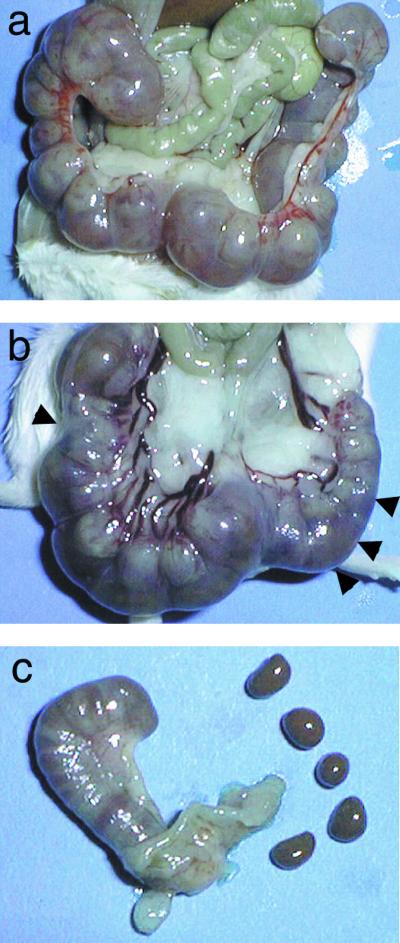

FIG. 1.

(a) Uterus of a pregnant control mouse on day 18 of pregnancy. All of the fetuses are growing normally. (b) Uterus of a pregnant mouse (day 18 of pregnancy) injected with 3.13 pg of Stx2 per g on day 5 of pregnancy. The arrowheads are pointing to fetuses in which growth is retarded. (c) Uterus of a pregnant mouse injected with 6.25 pg of Stx2 per g on day 5. All of the conceptuses have undergone fetoplacental resorption.

(iii) Pathological findings in uteri of pregnant mice.

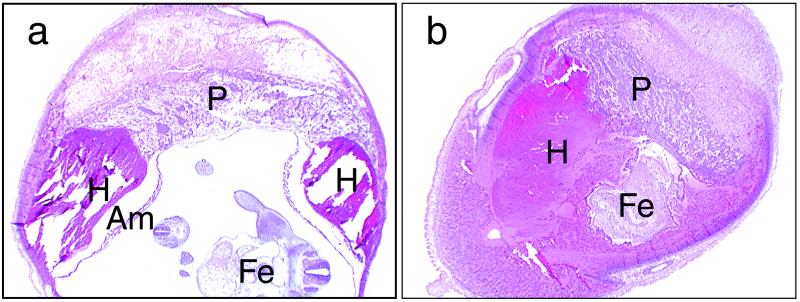

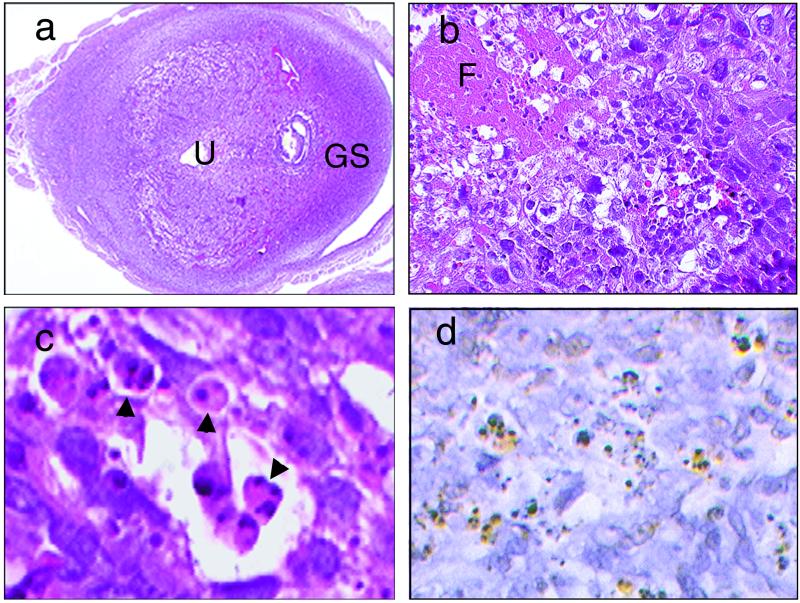

Day 5 of pregnancy was too early to observe subtle pathological changes due to Stx2 injection. Therefore, 15 mice were injected with 3.13 or 6.25 pg of Stx2 per g on day 7 of pregnancy, and 3 each were sacrificed on days 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12. Hemorrhages in the space between amnion and placenta could be seen by day 11 of pregnancy (Fig. 2a), accompanied by fetoplacental resorption; in a severe case, the spaces between the amnion and placenta were filled with hemorrhages (Fig. 2b). Finally, the fetoplacental tissues were involved by the hematoma, which we called fetoplacental resorption. Injection of 6.25 pg of Stx2 per g resulted in more severe lesions than 3.13 pg of Stx2 per g did. The initial lesion was detected by an experiment with a high dose of Stx2 (200 pg/g). Focal fibrin deposition accompanied by neutrophilic infiltration was observed in the decidua between the gestational sac and uterine cavity 24 h after injection (Fig. 3a and b). Fragmented nuclei of trophoblasts were also noted in the lesions (Fig. 3c, arrowheads). Apoptosis of trophoblasts was confirmed by the TUNEL method, suggesting apoptotic cell death of the trophoblasts (Fig. 3d, brownish cells).

FIG. 2.

Pathological findings from the pregnant uterus of mice injected with 3.13 (a) or 6.25 (b) pg of Stx2 per g on day 7 of pregnancy. The uterus on day 11 of pregnancy was observed by hematoxylin and eosin staining. (a) Hemorrhages (H) between the amnion (Am) and placenta (P) can be observed. (b) The hemorrhage extends between the amnion and placenta, and the spaces between amnion and placenta were filled with the hemorrhage. Fe, fetus.

FIG. 3.

Uterus of a pregnant mouse after Stx2 injection (200 pg/g) on day 7 of pregnancy. (a, b, and c) Hematoxylin and eosin staining. (d) TUNEL staining. (a) Fibrin deposition accompanied with neutrophilic infiltration can be observed in the area between the gestational sac (GS) and uterine cavity (U). Panel b is the same as panel a, but at high magnification. Fibrin deposition (F) with neutrophilic infiltration is visible in the tissues, including trophoblasts and adjacent decidua. (c) Fragmented nuclei of trophoblasts (arrowheads). (d) TUNEL-positive cells, shown as brownish cells which correspond to trophoblasts exhibiting nuclear fragmentation.

Effects of Stx2 injection in the late stage of pregnancy. (i) Effect on maternal lethality.

When Stx2 was injected on day 15 of pregnancy, the LD50 of Stx2 for the pregnant mice was 25.0 pg/g, which was not different from those of the early-stage or nonpregnant mice (Table 1).

(ii) Effects on fetuses and delivery period.

The delivery periods of pregnant mice injected on day 15 of pregnancy with 6.25, 12.5, and 25 pg of Stx2 per g were 19.0 ± 0.3, 19.0 ± 0.4, and 18.9 ± 0.3 days of pregnancy, respectively, which were not statistically different from that of control pregnant mice (18.9 ± 0.4 days of pregnancy). All mice injected with Stx2 delivered normally grown neonates with no macroscopic malformation.

(iii) Effects on neonates and maternal behavior.

After Stx2 injection on day 15 of pregnancy, maternal behavior and neonatal numbers were observed until 7 days after delivery. At the time of delivery, the neonatal numbers of the mice injected with 6.25, 12.5, and 25 pg/g of Stx2 on day 15 of pregnancy were 13.0 ± 2.9, 13.0 ± 2.0, and 13.3 ± 3.3, respectively, which were not statistically different from that of control mice (14.0 ± 2.9). Although the control mice built a nest of neonates and performed arched-back nursing, Stx2-injected mice did not perform such maternal behavior. Seven days after the delivery, the neonatal numbers of mice injected with 6.25, 12.5, and 25 pg of Stx2 per g decreased to 5.3 ± 6.0, 2.4 ± 5.4, and 3.7 ± 6.4, respectively, which were significantly lower than that of the control mice (14.0 ± 2.9; P < 0.05).

In order to investigate whether mothers or neonates were responsible for the decrease in neonatal survival, we exchanged mother-neonate pairs between control and Stx2-injected groups and observed the numbers of neonates for a week (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Effects of Stx2 on neonatal survival in mother-neonate exchange experiment

| Pair examined

|

No. of mother mice used | No. of neonates (mean ± SD)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother | Neonates | Before exchange | 7 days after exchange | |

| Control | Control | 6 | 13.7 ± 3.2 | 12.0 ± 6.2 |

| Stx2a | Control | 7 | 14.4 ± 2.0 | 7.4 ± 7.0b |

| Control | Stx2c | 7 | 12.0 ± 2.0 | 11.7 ± 1.8 |

Mothers were injected with 12.5 pg of Stx2 per g on day 15 of pregnancy.

P < 0.05 versus before exchange.

Neonates born to mothers injected with Stx2 (12.5 pg/g of body weight) on day 15 of pregnancy.

When nursed by control mothers, the numbers of neonates born to either control or Stx2-injected mothers did not decrease after delivery (13.7 ± 3.2 to 12.0 ± 6.2, 12.0 ± 2.0 to 11.7 ± 1.8, respectively). In contrast, when Stx2-injected mothers nursed neonates born to control mothers, the neonatal numbers significantly decreased (14.4 ± 2.0 to 7.4 ± 7.0 [Table 3]).

DISCUSSION

We evaluated the effects of Stx2 on maternal lethality, fetuses, delivery period, and maternal behavior after delivery in mice. An intravenous Stx2 injection (3.13 or 6.25 pg/g) on day 5 of pregnancy (early stage) induced fetoplacental resorption with intrauterine hematoma. Higher doses of Stx2 (200 pg/g) caused fibrin deposition and neutrophil infiltration (Fig. 3b), which were thought to result from the inflammatory reaction, possibly accompanied by vascular endothelial injury. It is thought that, not only apoptosis, as evidenced by nuclear fragmentation (Fig. 3c) and TUNEL staining (Fig. 3d), but also necrosis caused such pathologic changes in trophoblastic cells. Stxs have been reported to induce apoptosis in Vero cells (6) and in human renal tubular epithelial cells (10). It is possible that the low dose of Stx2 injures the trophoblasts so gradually that we could not successfully detect the initial pathological changes in the fetoplacental unit.

Silver et al. (19) reported that systemic administration of LPS caused fetal death in a dose-dependent fashion. They observed two types of changes in fetuses, i.e., intrauterine fetal death and fetoplacental resorption. Fetal deaths were recognized as involving formed fetuses and placentas, and resorptions were quite small and had no identifiable fetuses. In this study, we could observe only fetoplacental resorption induced by Stx2 intoxication, which resembled LPS-induced resorption shown by Silver et al. (19).

Structural completion of the murine placenta occurs on day 11 of pregnancy. Our results suggest that Stx2 toxemia in maternal blood injures trophoblasts and causes intrauterine hemorrhage prior to this time in pregnant mice. In the late stage of pregnancy, however, Stx2 did not affect fetal viability (Table 3). Instead, Stx2-injected mothers did not perform normal maternal behaviors, leading to neonatal demise. This was true in the mother-neonate pair exchange study as well. Therefore, we conclude that the mothers, but not neonates, were affected by Stx2 at the late stage of pregnancy. There are other examples of chemically induced alterations of maternal behavior by exazepam or benzodiazepine (11).

Stx2 injection in both the early and late stages of pregnancy in mice did not affect the time to delivery. From our results, we conclude that EHEC infection may not be a risk factor for preterm labor. In contrast, there have been many reports showing LPS-induced preterm parturition in animal models. Fidel et al. (3) injected pregnant C3H/HeN mice with 50 μg of LPS intraperitoneally on day 15 of pregnancy. The injection-to-delivery interval was shorter in mice injected with LPS (median, 15.5 h; range, 10 to 105 h) than in phosphate-buffered saline solution-treated mice (median, 88.5 h; range, 53 to 105 h).

Pregnancy did not alter maternal lethality due to Stx2. However, it remains to be elucidated whether pregnancy is a risk factor for development of HUS or acute encephalopathy in humans.

Data from humans suggest that Stx2 is a more important virulence factor than Stx1 for progression of E. coli O157:H7 infection to HUS (16, 18, 21), and mouse models support this observation. We therefore injected Stx2 into mice in this experiment.

In conclusion, Stx2 injection in pregnant mice before or after completion of placental development induced abortion or disorders in maternal puerperal behavior, respectively. Although there are no reports of Stx-mediated fetal loss or damage in humans, we speculate that EHEC infection during early pregnancy could be detrimental to the fetus. Further investigations are necessary to understand whether pregnancy is a risk factor for development of a serious state of EHEC infection in humans and whether EHEC infection is an important cause of loss in early pregnancy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Emmet Hirsch of the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons for helpful comments and critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi E, Tanaka H, Toyoda N, Takeda T. Detection of bactericidal antibody in the breast milk of a mother infected with enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 1999;73:451–456. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.73.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buendia A J, Sánchez J, Martinez M C, Cámara P, Navarro J A, Rodolakis A, Salinas J. Kinetics of infection and effects on placental cell populations in a murine model of Chlamydia psittaci-induced abortion. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2128–2134. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2128-2134.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fidel P L, Jr, Romero R, Wolf N, Cutright J, Ramirez M, Araneda H, Cotton D B. Systemic and local cytokine profiles in endotoxin-induced preterm parturition in mice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:1467–1475. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibbs R S, Duff P. Progress in pathogenesis and management of clinical intraamniotic infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:1317–1326. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90707-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hillier S L, Martius J, Krohn M, Kiviat N, Holmes K K, Eschenbach D A. A case-control study of chorioamnionic infection and histologic chorioamnionitis in prematurity. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:972–978. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810133191503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inward C D, Williams J, Chant I, Crocker J, Milford D V, Rose P E, Taylor C M. Verocytotoxin-1 induces apoptosis in vero cells. J Infect. 1995;30:213–218. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(95)90693-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karmali M A. Infection by verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2:15–38. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karmali M A, Petric M, Lim C, Fleming P C, Arbus G S, Lior H. The association between idiopathic hemolytic uremic syndrome and infection by verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:775–782. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.5.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karmali M A, Steele B T, Petric M, Lim C. Sporadic cases of haemolytic-uraemic syndrome associated with faecal cytotoxin and cytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli in stools. Lancet. 1983;1:619–620. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91795-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiyokawa N, Taguchi T, Mori T, Uchida H, Sato N, Takeda T, Fujimoto J. Induction of apoptosis in normal human renal tubular epithelial cells by Escherichia coli Shiga toxins 1 and 2. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:178–184. doi: 10.1086/515592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laviola G, Petruzzi S, Rankin J, Alleva E. Induction of maternal behavior by mouse neonates: influence of dam parity and prenatal oxazepam exposure. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;49:871–876. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lingwood C A. Verotoxin-binding in human renal sections. Nephron. 1994;66:21–28. doi: 10.1159/000187761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lingwood C A, Law H, Richardson S, Petric M, Brunton J L, De Grandis S, Karmali M. Glycolipid binding of purified and recombinant Escherichia coli produced verotoxin in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:8834–8839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLauchlin J. Human listeriosis in Britain, 1967–85, a summary of 722 cases. 2. Listeriosis in non-pregnant individuals, a changing pattern of infection and seasonal incidence. Epidemiol Infect. 1990;104:191–201. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800059355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison D M, Tyrrell D L, Jewell L D. Colonic biopsy in verotoxin-induced hemorrhagic colitis and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) Am J Clin Pathol. 1986;86:108–112. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/86.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ostroff S M, Kobayashi J M, Lewis J H. Infections with Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Washington State. The first year of statewide disease surveillance. JAMA. 1989;262:355–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riley L W, Remis R S, Helgerson S D, McGee H B, Wells J G, Davis B R, Hebert R J, Olcott E S, Johnson L M, Hargrett N T, Blake P A, Cohen M L. Hemorrhagic colitis associated with a rare Escherichia coli serotype. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:681–685. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198303243081203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scotland S M, Willshaw G A, Smith H R, Rowe B. Properties of strains of Escherichia coli belonging to serogroup O157 with special reference to production of Vero cytotoxins VT1 and VT2. Epidemiol Infect. 1987;99:613–624. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800066462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silver R M, Edwin S S, Trautman M S, Simmons D L, Branch D W, Dudley D J, Mitchell M D. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide-mediated fetal death. Production of a newly recognized form of inducible cyclooxygenase (COX-2) in murine decidua in response to lipopolysaccharide. J Clin Investig. 1995;95:725–731. doi: 10.1172/JCI117719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tesh V L, Samuel J E, Perera L P, Sharefkin J B, O'Brien A D. Evaluation of the role of Shiga and Shiga-like toxins in mediating direct damage to human vascular endothelial cells. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:344–352. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas A, Chart H, Cheasty T, Smith H R, Frost J A, Rowe B. Vero cytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli, particularly serogroup O 157, associated with human infections in the United Kingdom: 1989–91. Epidemiol Infect. 1993;110:591–600. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800051013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yutsudo T, Nakabayashi N, Hirayama T, Takeda Y. Purification and some properties of a Vero toxin from Escherichia coli O157:H7 that is immunologically unrelated to Shiga toxin. Microb Pathog. 1987;3:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]