Abstract

Flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum L.) is gaining popularity as a superfood due to its health-promoting properties. Mature flax grain includes an array of biologically active cyclic peptides or linusorbs (LOs, also known as cyclolinopeptides) that are synthesized from three or more ribosome-derived precursors. Two flaxseed orbitides, [1–9-NαC]-linusorb B3 and [1–9-NαC]-linusorb B2, suppress immunity, induce apoptosis in a cell line derived from human epithelial cancer cells (Calu-3), and inhibit T-cell proliferation, but the mechanism of LO action is unknown. LO-induced changes in gene expression in both nematode cultures and human cancer cell lines indicate that LOs promoted apoptosis. Specific evidence of LO bioactivity included: (1) distribution of LOs throughout the organism after flaxseed consumption; (2) induction of heat shock protein (HSP) 70A, an indicator of stress; (3) induction of apoptosis in Calu-3 cells; and (4) modulation of regulatory genes (determined by microarray analysis). In specific cancer cells, LOs induced apoptosis as well as HSPs in nematodes. The uptake of LOs from dietary sources indicates that these compounds might be suitable as delivery platforms for a variety of biologically active molecules for cancer therapy.

Keywords: flaxseed, linusorb, cyclic peptide, heat shock protein, apoptosis, anti-cancer

1. Introduction

Linusorbs (LOs) isolated from flaxseed oil are naturally occurring cyclo-oligopeptides (9–11 amino acid residues) with low molecular weights (~1 kDa) [1]. Since 1959 [2], 11 natural LOs have been identified in flaxseed oil, roots, and seed [3,4,5,6], and another 28 have been synthetically produced [7]. These LOs have been investigated for their range of therapeutic bioactivity (e.g., antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer effects) [8,9,10] due to their high stability, potency, and bioavailability [11,12,13]. For instance, [1–9-NαC]-linusorb B3 (LOB3) inhibits cholate uptake in hepatocytes, thus potentially mitigating liver damage [14]. LOB3 also suppresses phosphatase activity and thereby inhibits the activation and proliferation of T-lymphocytes [15,16]. T-lymphocyte inhibition, induced by LOs, has exhibited immunosuppressant effects (e.g., delayed hypersensitivity response, postponed skin allograft rejection, suppressed post-adjuvant arthritis, and suppression of hemolytic anemia) [17,18] and cytoprotective effects [19,20].

The immunomodulatory activity of LOB3 has previously been investigated due to similarities in its nonapeptide sequence to bovine colostrum sequences [15,21]. For example, in vitro and in vivo in tests involving human lymphocyte cell lines and Jerne plaque-forming cell assays revealed immunosuppressive activity of LOB3 in both humoral and cellular immune responses [15,16]. The bioactive effects of LOB3 in in vitro studies showed the ability of this compound in delaying skin allograft rejection, inhibiting human lymphocyte proliferation, and alleviating post-adjuvant polyarthritis and hemolytic anemia in mice [15]. Low concentrations of LOB3 were also capable of inducing T and B cell proliferation, acquisition of activation antigens, and immunoglobulin (Ig) synthesis [16], similar to the biological effect of the immunosuppressant drug cyclosporine (CsA).

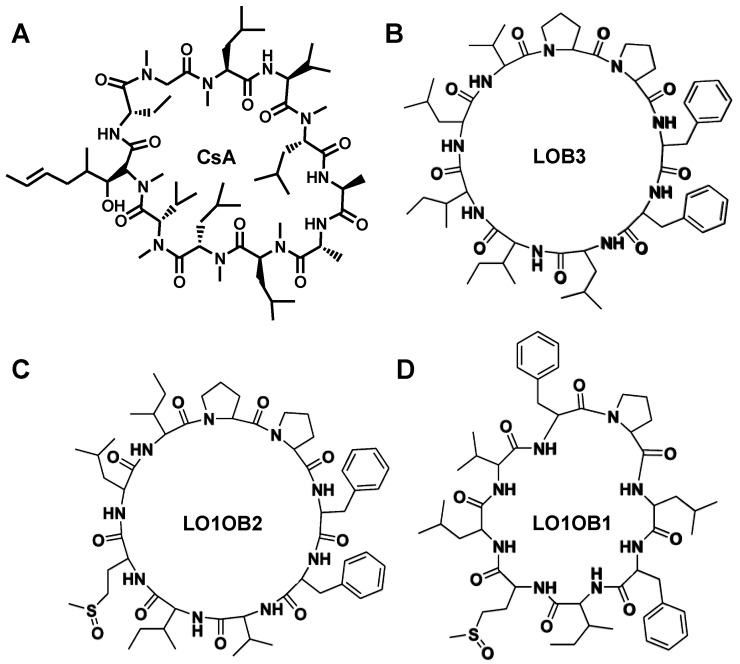

LOB3 has previously demonstrated non-toxic effects in both rats and mice when administered orally and intravenously [18]. The combined characteristics of the strong immunosuppressive activity and low toxicity make LOB3 an immunosuppressive drug candidate. Other LOs and their analogs have also been investigated for their immunosuppressant activity. For example, [1–9-NαC]-linusorb B2 (LOB2, also known as CLB) has also been observed to induce the proliferation of human peripheral blood lymphocytes such as CsA [3]. Similarly, [1–8-NαC], [1-(Rs, Ss)-MetO]-linusorb B1 (LO1OB1, also known as CLE) could also induce lymphocyte proliferation in mice [3]. Interestingly, chemical analogs of LOB3 exhibited immunosuppressant effects as well [18,22,23]. However, LOB3 demonstrated the highest activity [18,22,23]. Nonetheless, the biological activity of these analogs was influenced by their peptide sequence, with the presence of –Pro-Xxx-Phe– sequence, where Xxx denotes a hydrophobic, aliphatic, or aromatic residue contributing to a greater biological response [22,23,24] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of (A) CsA and (B–D) LOs.

Heat shock proteins (HSP) are often expressed when stressors denature an organism’s protein. In order to stabilize denaturing proteins, chaperones (e.g., HSPs) are expressed to assist in refolding denatured proteins while facilitating the recycling of irreversibly denatured proteins [25].

The rapid expression of HSPs by Caenorhabditis elegans has been used as a model system to study stress responses [26]. These proteins maintain cell function and survival while playing critical roles in an organism’s ability to adapt to biotic and abiotic stressors and facilitate recovery after the removal of stressors [25,27]. For example, 70 kDa HSP (HSP 70) are highly conserved and ubiquitous chaperones that are involved in preventing protein aggregation and refolding of denatured protein [25] during cellular stress. In part, they regulate heat shock responses through mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling [28]. These HSP proteins have also been well-characterized in C. elegans [26].

The overall focus of this study was to research the unknown biological activities of LOs, including: (i) its effects on HSP 70A expression on C. elegans as an indicator of stress; (ii) tissue distribution following flaxseed consumption; (iii) induction of apoptosis in cancer cell lines; and (iv) its effect on apoptotic gene expression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Whole flaxseed, flaxseed oil, and purified LOs (Table 1; Figure 1) from Linum usitatissimum L. (var. CDC Bethune) were generous gifts from Prairie Tide Diversified Inc. (Saskatoon, SK, Canada). Whole flaxseed was ground using a coffee grinder for 1 min (Model 80335, Hamilton Beach Brands, Inc., Glen Allen, VA, USA), and the flaxseed meal was then used in the feeding experiment, further described below.

Table 1.

Primary structures of select LOs.

| Code a | New Name b |

Literature Name c |

Molecular Weight (Da) |

Chemical Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOB3 | [1–9-NαC]-linusorb B3 | CLA | 1040.34 | C57H85N9O9 |

| LO1OB2 | [1–9-NαC], [1-(Rs, Ss)-MetO]- linusorb B2 |

CLC | 1074.37 | C56H83N9O10S |

| LO1OB1 | [1–8-NαC], [1-(Rs, Ss)-MetO]- linusorb B1 |

CLE | 977.26 | C51H76N8O9S |

a Codes are O for methionine S-oxide; b The systematic nomenclature proposed by Shim et al. (2015) [29]; c Name used in subsequent literature description.

2.2. Conformation of LOs in an Aqueous-DMSO Solution

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy was performed on LO samples using a fresh solution of aqueous-dimethylsulfoxide solution (H2O/DMSO, 3%, v/v). CD measurements were completed using a Pistar 180 spectrometer (Applied Photophysics Ltd., Leatherhead, UK). Sample measurements were conducted at room temperature using a 0.01 cm cuvette (Hellma 106-QSP), and samples were scanned between 200–260 nm at 0.5 nm increments, with a scan rate of 10 nm/min. The instrument was calibrated using (+)-10-camphorsulfonic acid (290.5 nm wavelength). Experiments were performed in triplicate and are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The secondary structure content of the samples was evaluated with the CDNN CD Spectroscopy Deconvolution software version 2.0.3.188 [30]. Molar ellipticities were calculated from molecular masses of 977.26–1074.37 Da for LOs. All spectra were corrected by background subtraction of H2O/DMSO (3%, v/v).

2.3. LOs in Pig and Fish Adipose

Swine and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) samples were obtained from previous dietary studies conducted by Juárez et al. (2010) [31] and Drew et al. (2007) [32], respectively. In trout diets, fish were fed a blend of 35% flaxseed oil with canola oil. The oil blend was included in the diet at 20% of the ration. Swine were fed a diet consisting of 15% flaxseed meal that was combined with other ingredients then extruded. Swine fat samples were taken from an 8 mm biopsy punch at the 10th rib, approximately 5 cm from the backbone [31]. The tissue samples were then extracted with chloroform and the extracts were dried, taken up in acetonitrile, and analyzed via direct loop injections using an Agilent 1100-series high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a time-of-flight mass spectrometer (ToF-MS). Each sample extract was injected at a flow rate of 50 μL/min. The mobile phase consisted of 95% water: methanol containing 0.1% formic acid, and 5% acetonitrile.

2.4. Induction of HSP 70A in Nematodes

Gene expression of HSP 70A in nematodes was completed as described in Saini et al. (2011) [33]. Briefly, C. elegans N2 strains were cultured in the dark and at room temperature on sterile plates (10 mm; VWR, Edmonton, AB, Canada) containing 10% bacteriological agar (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON, Canada) and autoclaved Baker’s yeast (1%, w/v). C. elegans were sub-cultured every 14 days to fresh plates. Exposure experiments began using C. elegans, which were two weeks old. These cultures were exposed for 2 h to either DMSO (negative control) or various concentrations (0.1, 1.0, 10.0, and 100.0 µM) of LOB3 dissolved in DMSO. After exposure, these organisms were then re-cultured to assess the effects of LOB3 on HSP 70A gene expression. An unamended culture medium was used as the control treatment. After treatment, cultures were centrifuged at 400× g for 10 min at 4 °C. The pellet was retained and stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

2.5. Induction of Apoptosis in Human Lung Cancer Cell Line

2.5.1. Cell Culture

Human bronchial epithelial adenocarcinoma cell line (Calu-3) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Calu-3 cell line was cultured in plastic culture flasks containing Modified Eagle’s Medium (MEM) and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, glutamine (4 mM), and penicillin (100 U/mL)-streptomycin (100 μg/mL) solution. Cells were cultured to a density of 106 cells/mL before adding fresh media (on day 3). The cells were then grown at 37 °C under 5% CO2, and 100% humidity.

2.5.2. Chemical Treatments

Effects of LOs were tested on Calu-3 cells at different concentrations (0–100 μM). Camptothecin (CPT) (4 μM; Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON, Canada) and DMSO were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. CPT is a cytotoxic quinoline alkaloid that has demonstrated anti-cancer effects due to the inhibition of topoisomerase I, an enzyme involved in DNA replication and repair.

2.5.3. Ribonucleic Acid (RNA) Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time Reverse-Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

RNeasy® Mini kits (Qiagen, Mississauga, ON, Canada) were used to extract total RNA from C. elegans lysates, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality was confirmed and quantified using agarose gel electrophoresis and a Nano Drop® spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Ottawa, ON, Canada), respectively. After DNase treatment, mRNA was reverse transcribed using a QuantiTect® Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen, Mississauga, ON, Canada) at 42 °C for 30 min. qRT-PCR was then conducted to record the gene expression for HSP 70A (GenBank Accession No. M18540); p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA, GenBank Accession No. AF354655); and BCL2 alpha (GenBank Accession No. NM_000633). This was accomplished using a Stratagene MX3005P LightCycler (La Jolla, CA, USA). The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (GAPDH; GenBank Accession No. X04818) was used as the reference housekeeping gene for qRT-PCR analyses. The primer pairs used during qRT-PCR are listed in Table 2. qRT-PCR reactions were performed using QuantiFast® SYBR® Green PCR kit (Qiagen, Mississauga, ON, Canada) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The thermocycler conditions included an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s and elongation at 60 °C for 45 s, to amplify the target gene. Relative gene expression levels were corrected against the GAPDH housekeeping gene using MXPro software. All analyses were completed in triplicate.

Table 2.

Primer pairs for investigated genes: PUMA, BCL2 alpha, and GAPDH.

| cDNA | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| PUMA | 5′-ATG AAA TTT GGC ATG GGG TCT-3′ | 5′-GCC TGG TGG ACC GCC C-3′ |

| BCL2 alpha | 5′-ATG GCG CAC GCT GGG AGA AC-3′ | 5′-GCG ACC GGG TCC CGG GAT GC-3′ |

| GAPDH | 5′-ATG GGG AAG GTG AAG-3′ | 5′-GAC AAG CTT CCC GTT CTC-3′ |

2.6. Microarray Analysis of the Individual LOs

Microarray analysis was performed to determine LO effects on the expression of genes involved in regulating apoptosis (i.e., pro- or anti-apoptotic genes) in Calu-3 cells. These analyses were using an Rt2 Profiler PCR Super Array kit (Super Arrays Bioscience Corp., Frederick, MD, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions and were recorded using an MX3005P LightCycler (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software ver. 18.0 (IBM Corp., Somers, NY, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan’s multiple-range tests were used to compare means within treatment groups. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was measured at 95% (p < 0.05) and 99% (p < 0.01).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Conformation of LOs in an Aqueous-DMSO Solution

The conformations of LOs were studied in a solution of aqueous-DMSO, as well as in the presence of the most used co-solvent for stabilizing conformation. CD spectroscopy identified secondary peptide structures present in LOs and showed that the LOs in solution were dominated by unordered structures, thus giving the ability to distinguish between the binding and inhibition of aggregation events. In an aqueous-DMSO solution, CD identified α-helices as the dominant secondary structures in LOs; although, there were more α-helices in this solvent than in other organic solvents (1,4-dioxane and tetrahydrofuran, data not shown). The CD spectra of LOB3 and LO1OB2 (with methionine sulfoxide) suggested high levels of α-helices and lesser amounts of other secondary structures compared to that of LO1OB1 (Table 3). However, overall, LO1OB2 and LO1OB1 with methionine residue still contained >75% of α-helices. The secondary structure of LOB3 was composed of α-helix (99.9%), parallel β-sheet (0.3%), β-turn (0.7%), and random coil conformations (0.1%). These observations were supported by a relatively good fit to the experimental spectra. LOs in aqueous-DMSO solutions indicated large amounts of hydrophobic compounds. However, none of these conformational forms appeared to be stabilized by strong intramolecular hydrogen bonds. The methods described in this study demonstrated greater recovery of hydrophobic cyclic peptides than other conventional methods.

Table 3.

Protein secondary structure estimates for LOs of CD spectra (260–200 nm) in an aqueous-DMSO solution.

| Code | α-Helix (%) | Antiparallel (%) | Parallel (%) | β-Turn (%) | Random Coil (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOB3 | 98.90 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.70 | 0.10 |

| LO1OB2 | 98.90 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.10 |

| LO1OB1 | 75.30 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 6.20 | 18.20 |

3.2. Binding of LOs in Adipose Tissue

Diets containing either flaxseed or flaxseed oil were fed to pigs or rainbow trout, respectively, to investigate the distribution of LOs in these model organisms. After the consumption of extruded flaxseed or flaxseed oil, three LOs were identified by molecular ions in the mass spectra of animal fats (Figure 2). The trace amounts of hydrophobic LOs primarily distributed to the adipose tissues, as inferred by the presence of LO1OB1, LO1OB2, and LOB3. However, it is uncertain if enough LOs were absorbed to exert a biological response.

Figure 2.

Localization of observed LOs (LO1OB1, LO1OB2, and LOB3) in (A) pig and (B) rainbow trout adipose, identified via direct injection on an Agilent 1100-series HPLC-ToF-MS.

3.3. Induction of HSP 70A in Nematodes

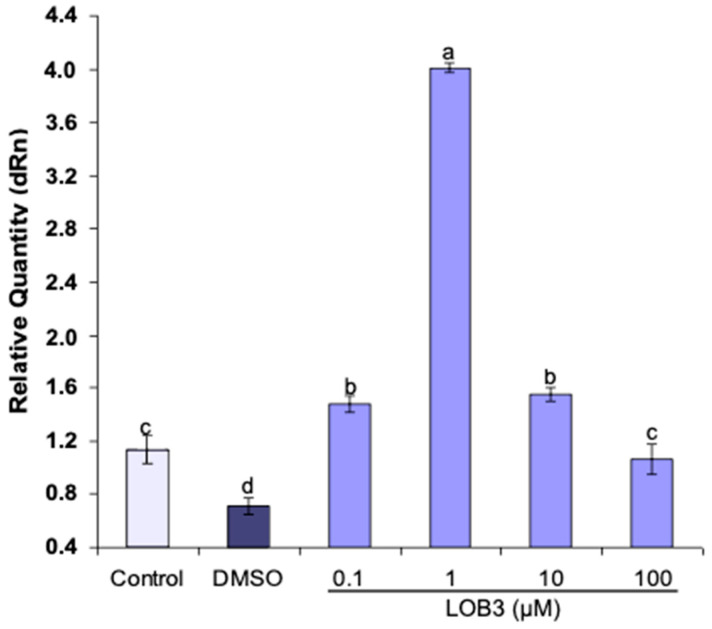

Nematode cultures (C. elegans) were exposed to LOB3 at 0.1 μM, 1.0 μM, 10.0 μM and 100.0 μM for 2 h to monitor the effects of LOB3 on HSP 70A gene expression. At low concentrations (<1.0 μM), LOB3 induced a stress response in C. elegans cultures, signified by the production of HSP 70A (Figure 3). Interestingly, LOB3 illustrated an inverted U-shaped dose-response, in which the addition of either 0.1 µM or 10.0 µM of LOB3 to the culture media of C. elegans resulted in a 30% increase in HSP 70A protein production. With the addition of 1.0 µM LOB3, the production of this protein increased 3.5-fold (Figure 3). However, treatment at the highest concentration (e.g., 100 µM) was lethal. These results further support previous studies where no cytotoxic effects were observed at doses lower than 10 µM in cancer C6 cells and breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 [10]. At concentrations greater than 10.0 µM, cytotoxic effects were observed in C6 cells, including changes in cell shape and a reduction in cell numbers [10]. These findings suggest that structural deformities may have occurred in the highest dose group and thus resulted in mortality. Nonetheless, the administration of LOB3 at concentrations < 10.0 µM induced a strong stress response in C. elegans, inferred by the induction of HSP 70A. These proteins function in a variety of biochemical processes, including protein folding, transportation, and regulation of heat shock response [34]. The activation of the HSP 70 protein can also mediate cellular protection by interfering with the process of apoptotic cell death [35]. This is accomplished by blocking the assembly of a functional apoptosome and preventing apoptosis [35]. Furthermore, during the initial stages of tumorigenesis, HSP 70 can protect cells from oncogenic stress induced by the over-expression of oncogenes [36], as well as suppress cellular senescence, which is an important anti-tumor mechanism [37]. However, HSP 70 is also an essential factor in tumorigenesis [38], promoting tumor cell growth by inhibiting apoptosis and/or stabilizing the lysosomal membrane [39,40]. The expression of HSP 70 is also known to activate innate and adaptive immunity through the production of cytokines [41]. In addition, the increased translocation of HSP 70 into the extracellular milieu has also been observed to enhance the sensitivity of cancer cells to chemotherapies [41]. Due to these properties, it is important to ensure the induction of HSP 70A production by LOs is beneficial in exhibiting anti-cancer effects rather than contributing to tumorigenesis. Nonetheless, the administration of LOs to nematodes resulted in the activation of HSPs, suggesting its importance in elucidating a cellular response in mitigating stressors and maintaining homeostasis. Although, the identification of the regulatory pathways involved in controlling HSP 70A expression and activity should be further investigated [42]. This can lead to enhanced diagnoses or designs in developing new therapeutic strategies to combat cancerous cells, including the inhibition of multiple signaling pathways in cancer cells [41].

Figure 3.

Induction of HSP 70A mRNA expression in C. elegans by LOB3 at different concentrations. The different letters (a–d) represent significance at p < 0.01. All samples were normalized to GAPDH expression. An Unamended culture medium and DMSO were used as the control treatment and negative control, respectively. Mean HSP 70 values and SDs from three repetitions shown. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test. Values not sharing a common letter are significantly different (p < 0.01).

3.4. Induction of Apoptosis in Human Lung Cancer Cell Lines with LOs

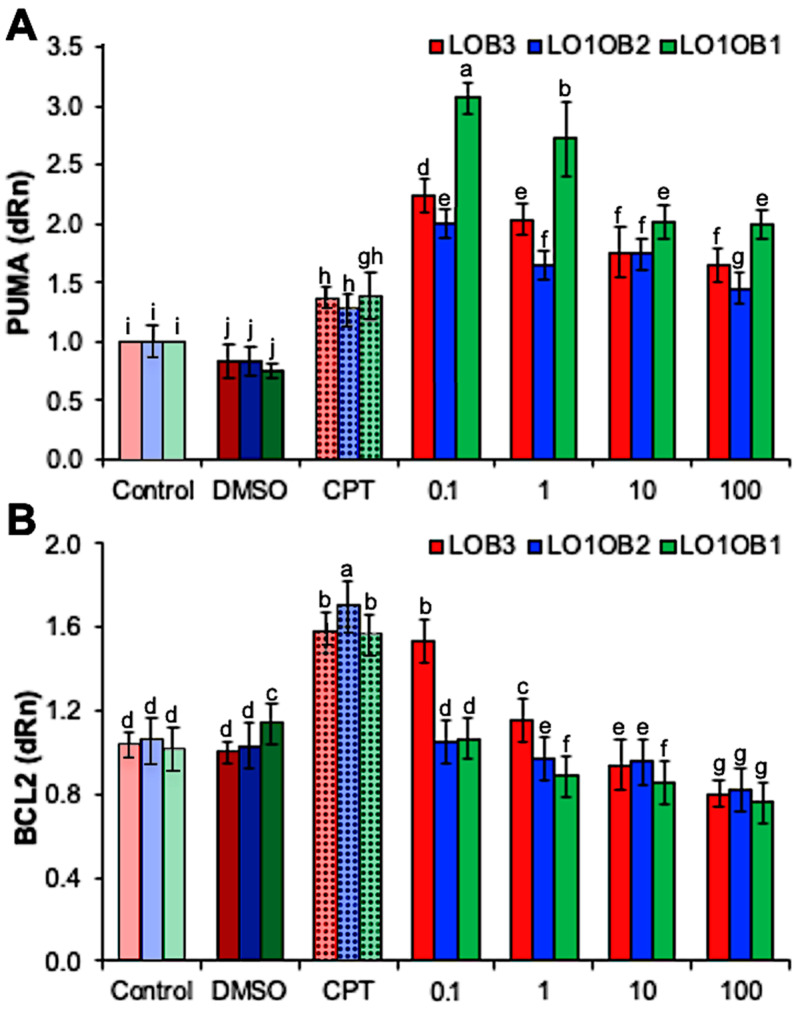

The expressions of PUMA and the anti-apoptotic gene BCL2 both decreased with increasing concentrations (0.1–100 µM) of each of the three LOs (p < 0.05) (Figure 4). These results suggest that the gene expression of the pro-apoptotic gene PUMA was influenced by LOs. This supports earlier studies where cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors and tumor-suppressor proteins were upregulated in the presence LOs [43], which can demonstrate anti-cancer properties, such as preventing the over-proliferation of cancer cells or mediating p53-induced cell death [44]. Interestingly, the expression of the anti-apoptotic gene BCL2 significantly declined with increased LO concentration than in CPT as a positive control (p < 0.05) (Figure 4B). Similar results have been observed in adenocarcinoma cells where the expression of Bax was upregulated while BCL2 expression was down-regulated in a dose-dependent manner [45]. Altogether, the up-regulation of apoptotic genes, and down-regulation of BCL2, induced by LOs, indicate potential applications of these compounds as chemotherapy agents due to their anti-cancer properties.

Figure 4.

Gene expressions of (A) PUMA and (B) BCL2 after LO treatments. DMSO is a common negative control and is used as a solvent for dissolving LOs as LOs do not dissolve in water. CPT (positive control) is a cytotoxic quinoline alkaloid that inhibits the DNA enzyme topoisomerase I and has shown remarkable anti-cancer activity. The different letters (a–j) represent significance at p < 0.05.

3.5. Microarray Analysis of the Individual LOs

Gene expression in human lung adenocarcinoma cells exposed to LOs was investigated by microarray analyses to determine effects on gene regulation and induction of apoptosis (Table 4). The results further supported our findings of the upregulation of apoptotic genes combined with the suppression of anti-apoptotic genes (i.e., BCL2). Comparatively, gene expression profiling of human lung epithelial cells (e.g., Calu-3) treated with RGDSK/K-RNT (5:50 mM) for 4 h induced over-expression of pro-apoptotic genes. Increased expression of BAK1, BCL2, CASP10, CIDEB, TP53BP2, Fas, TNF, and FasL suggest that p38 MAPK regulates RGDSK/K-RNT-induced apoptosis in Calu-3 cells. Furthermore, flaxseed administration has been demonstrated to reduce phosphorylated levels of MAPKs and suppress the expression of cytokines [24]. This suggests that LOs may be involved in the MAPK/AP-1 kinase signaling pathway and can be used in mitigating stressors. Although only LO1OB1, LO1OB2, and LOB3 were investigated in this study, it would be of interest to investigate the bioactive properties of other LOs. Nonetheless, the physicochemical and nutraceutical properties of LOs demonstrate the novelty of employing LOs for a variety of potential applications, including pharmaceutical, medicinal, and food supplement uses.

Table 4.

Curated list of genes up- or down-regulated in Calu-3 exposed to LOs.

| Symbol | Description | LOB3 | LO1OB2 | LO1OB1 | Role in Carcinogenesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAK1 | BCL2 antagonist/killer 1 | + a | NE b | NE | Brassinosteroid signaling, light responses, cell death, and plant innate immunity [46] |

| BCL2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 | + | – | – c | Caspase activation, regulation of apoptosis [47] |

| CASP10 | Caspase 10 | NE | + | NE | Aspartate-specific cysteine protease that participates in the apoptotic pathway [48] |

| CIDEA | Cell death-inducing DFFA- like effector A |

NE | + | + | Apoptotic gene [49] |

| CIDEB | Cell death-inducing DFFA- like effector B |

+ | + | + | Apoptotic gene [49] |

| HRK | Harakiri | NE | + | + | Activates and regulates apoptosis, pro-apoptotic gene [50] |

| Fas | TNF receptor superfamily member 6 |

+ | + | + | Induces apoptosis [51] |

| FasL | Fas ligand | + | NE | NE | Regulation of cell death [52] |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor | + | + | + | Cytokine that contributes to both physiological and pathological processes [53] |

| TP53 | Tumor protein p53 | + | + | NE | Tumor suppressor protein involved in preventing cancer [54] |

| TP53BP2 | Tumor protein p53 binding protein 2 |

+ | + | + | Regulates the proliferation, apoptosis, autophagy, migration, of tumor cells [55] |

a +: genes over-expressed; b NE: not expressed; c –: genes under-expressed.

4. Conclusions

LOs are bioactive compounds isolated from flaxseed oil that can have significant potential for therapeutic applications. These compounds can be readily obtained as an added-value natural flaxseed product and have demonstrated significant immunosuppressing activities, including anti-cancer effects. This study further identified broad-spectrum bioactivities associated with LOs, including induction of HSP 70A production in C. elegans and apoptosis in human lung epithelial cancer lines. LOs were additionally involved in modulating regulatory genes associated with apoptosis in human lung epithelial cancer lines, suggesting their anti-cancer properties. Therefore, the regulation of apoptosis genes by LOs indicates the possibility of applying these compounds as a form of chemotherapy agent.

Acknowledgments

Whole flaxseed, flaxseed oil, and LOs were kindly provided by Prairie Tide Diversified Inc. (Saskatoon, SK, Canada). Academic support for the research project was obtained from the Team Phat research group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.T.R.; Validation, Y.Y.S., T.J.T. and Y.J.K.; Data Curation; Y.J.K.; Formal Analysis, A.K.S.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Y.Y.S.; Writing—Review and Editing, T.J.T., Y.J.K. and M.J.T.R.; Visualization, Y.Y.S.; Supervision, M.J.T.R.; Project Administration, Y.Y.S. and Y.J.K.; Funding Acquisition, Y.Y.S. and M.J.T.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data of the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

M.J.T.R. is the founder of, and has an equity interest in, Prairie Tide Diversified Inc. (PTD, Saskatoon, SK, Canada). Y.Y.S. is the Korea Branch Representative for PTD in Korea. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by the University of Saskatchewan in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policies. Other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

The authors acknowledge the kind contribution of LOs from Prairie Tide Diversified Inc. (Saskatoon, SK, Canada). This research was supported by Brain Pool Program (2019H1D3A2A01102248 and 2020H1D3A2A02110965) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Shim Y.Y., Gui B., Arnison P.G., Wang Y., Reaney M.J.T. Flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum L.) bioactive compounds and peptide nomenclature: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014;38:5–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2014.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaufmann H.P., Tobschirbel A. Über ein Oligopeptid aus Leinsamen. Chem. Ber.-Recl. 1959;92:2805–2809. doi: 10.1002/cber.19590921122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morita H., Shishido A., Matsumoto T., Takeya K., Itokawa H., Hirano T., Oka K. A new immunosuppressive cyclic nonapeptide, cyclolinopeptide B from Linum usitatissimum. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1997;7:1269–1272. doi: 10.1016/S0960-894X(97)00206-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morita H., Kayashita T., Takeya K., Itokawa H., Shiro M. Conformation of cyclic heptapeptides: Solid and solution state conformation of yunnanin A. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:1607–1616. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(96)01098-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morita H., Shishido A., Matsumoto T., Itokawa H., Takeya K. Cyclolinopeptides B-E, new cyclic peptides from Linum usitatissimum. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:967–976. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(98)01086-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morita H., Shishido A., Matsumoto T., Itokawa H., Takeya K. Cyclolinopeptides F-I, cyclic peptides from linseed. Phytochemistry. 2001;57:251–260. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00442-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shim Y.Y., Song Z., Jadhav P.D., Reaney M.J.T. Orbitides from flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum L.): A comprehensive review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019;93:197–211. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2019.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharav O., Shim Y.Y., Okinyo-Owiti D.P., Sammynaiken R., Reaney M.J.T. Effect of cyclolinopeptides on the oxidative stability of flaxseed oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014;62:88–96. doi: 10.1021/jf4037744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ratan Z.A., Jeong D., Sung N.Y., Shim Y.Y., Reaney M.J.T., Yi Y.S., Cho J.Y. LOMIX, a mixture of flaxseed linusorbs, exerts anti-inflammatory effects through Src and Syk in the NF-kappaB pathway. Biomolecules. 2020;10:859. doi: 10.3390/biom10060859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sung N.Y., Jeong D., Shim Y.Y., Ratan Z.A., Jang Y.-J., Reaney M.J.T., Lee S., Lee B.-H., Kim J.-H., Yi Y.-S., et al. The anti-cancer effect of linusorb B3 from flaxseed oil through the promotion of apoptosis, inhibition of actin polymerization, and suppression of Src activity in glioblastoma cells. Molecules. 2020;25:5881. doi: 10.3390/molecules25245881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zorzi A., Deyle K., Heinis C. Cyclic peptide therapeutics: Past, present, and future. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2017;38:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bock J.E., Gavenonis J., Kritzer J.A. Getting in shape: Controlling peptide bioactivity and bioavailability using conformational constraints. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013;8:488–499. doi: 10.1021/cb300515u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thell K., Hellinger R., Sahin E., Michenthaler P., GoldBinder M., Haider T., Kuttke M., Liutkeviciute Z., Göransson U., Grundemann C., et al. Oral activity of a nature-derived cyclic peptide for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:3960–3965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519960113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler H., Klein M., Muller A., Wagner K., Bats J.W., Ziegler K., Frimmer M. Conformational prerequisites for the in vitro inhibition of cholate uptake in hepatocytes by cyclic analogs of antamanide and somatostatin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1986;25:997–999. doi: 10.1002/anie.198609971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wieczorek Z., Bengtsson B., Trojnar J., Siemion I.Z. Immunosuppressive activity of cyclolinopeptide A. Pept. Res. 1991;4:275–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Górski A., Kasprzycka M., Nowaczyk M., Wieczoreck Z., Siemion I.Z., Szelejewski W., Kutner A. Cyclolinopeptide: A novel immunosuppressive agent with potential anti-lipemic activity. Transplant. Proc. 2001;33:553. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(00)02139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaymes T.J., Cebrat M., Siemion I.Z., Kay J.E. Cyclolinopeptide A mediates its immunosuppressive activity through cyclophilin-dependent calcineurin inactivation. FEBS Lett. 1997;418:224–227. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)01345-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siemion I.Z., Cebrat M., Wieczorek Z. Cyclolinopeptides and their analogs—A new family of peptide immunosuppressants affecting the calcineurin system. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 1999;47:143–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossi F., Bianchini E. Synergistic induction of nitric oxide by beta-amyloid and cytokines in astrocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;225:474–478. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler H., Gehrke M., Haupt A., Klein M., Müller A., Wagner K. Common structural features for cytoprotection activities of somatostatin, antamanide and related peptides. Klin. Wochenschr. 1986;64:74–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubik W., Kliś A., Szewczuk Z., Siemion I.Z. Proline-rich polypeptide (prp)-a new peptide immunoregulator and its partial sequences. Peptides. 1984;31:457–460. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benedetti E., Pedone C. Cyclolinopeptide A: Inhibitor, immunosuppressor or other? J. Pept. Sci. 2005;11:268–272. doi: 10.1002/psc.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Picur B., Cebrat M., Zabrocki J., Siemion I.Z. Cyclopeptides of Linum usitatissimum. J. Pept. Sci. 2006;12:569–574. doi: 10.1002/psc.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shim Y.Y., Kim J.H., Cho J.Y., Reaney M.J.T. Health benefits of flaxseed and its peptides (linusorbs) Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022:1–20. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2119363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parsell D.A., Lindquist A.S. Heat shock proteins and stress responses. In: Morimoto R.I., Tissieres A., Georgopoulos C., editors. The Biology of Heat Shock Proteins and Molecular Chaperones. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York, NY, USA: 1994. pp. 457–494. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heschl M.F., Baillie D.L. Characterization of the hsp70 multigene family of Caenorhabditis elegans. DNA. 1989;8:233–243. doi: 10.1089/dna.1.1989.8.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vierling E: The roles of heat shock proteins in plants. Ann. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1991;42:579–620. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.42.060191.003051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suri S.S., Dhindsa R.S. A heat-activated MAP kinase (HAMK) as a mediator of heat shock response in tobacco cells. Plant Cell Environ. 2008;31:218–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shim Y.Y., Young L.W., Arnison P.G., Gilding E., Reaney M.J.T. Proposed systematic nomenclature for orbitides. J. Nat. Prod. 2015;78:645–652. doi: 10.1021/np500802p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bohm G., Muhr R., Jaenicke R. Quantitative analysis of protein far UV circular dichroism spectra by neural networks. Protein Eng. 1992;5:191–195. doi: 10.1093/protein/5.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juárez M., Dugan M.E.R., Aldai N., Aalhus J.L., Patience J.F., Zijlstra R.T., Beaulieu A.D. Feeding co-extruded flaxseed to pigs: Effects of duration and feeding level on growth performance and backfat fatty acid composition of grower-finisher pigs. Meat Sci. 2010;84:578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drew M.D., Ogunkoya A.E., Janz D.M., Van Kessel A.G. Dietary influence of replacing fish meal and oil with canola protein concentrate and vegetable oils on growth performance, fatty acid composition and organochlorine residues in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Aquaculture. 2007;267:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2007.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saini A.R.K., Tyler R.T., Shim Y.Y., Reaney M.J.T. Allyl isothiocyanate induced stress response in Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Res. Notes. 2011;4:502. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hartl F.U., Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in the cytosol: From nascent chain to folded protein. Science. 2002;295:1852–1858. doi: 10.1126/science.1068408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beere H.M., Wolf B.B., Cain K., Mosser D.D., Mahboubi A., Kuwana T., Tailor P., Morimoto R.I., Cohen G.M., Green D.R. Heat-shock protein 70 inhibits apoptosis by preventing recruitment of procaspase–9 to the Apaf-1 apoptosome. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:469–475. doi: 10.1038/35019501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goloudina A.R., Demidov O.N., Garrido C. Inhibition of HSP70: A challenging anti-cancer strategy. Cancer Lett. 2012;325:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Afanasyeva E.A., Komarova E.Y., Larsson L.-G., Bahram F., Margulis B.A., Guzhova I.V. Drug-induced Myc-mediated apoptosis of cancer cells is inhibited by stress protein Hsp70. Int. J. Cancer. 2007;121:2615–2621. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Min J.-A., Whaley R.A., Sharpless N.E., Lockyer P., Portbury A.L., Patterson C. CHIP deficiency decreases longevity, with accelerated aging phenotypes accompanied by altered protein quality control. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;28:4018–4025. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00296-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nylandsted J., Gyrd-Hansen M., Danielewicz A., Fehrenbacher N., Lademann U., Høyer-Hansen M., Weber E., Multhoff G., Rohde M., Jäättelä M. Heat shock protein 70 promotes cell survival by inhibiting lysosomal membrane permeabilization. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:425–435. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xanthoudakis S., Nicholson D.W. Heat-shock proteins as death determinants. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:E163–E165. doi: 10.1038/35023643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elsner L., Muppala V., Gehrmann M., Lozano J., Malzahn D., Bickeböller H., Brunner E., Zientkowska M., Herrmann T., Walter L., et al. The heat shock protein HSP70 promotes mouse NK cell activity against tumors that express inducible NKG2D ligands. J. Immunol. 2007;179:5523–5533. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zorzi E., Bonvini P. Inducible HSP70 in the regulation of cancel cell survival: Analysis of chaperone induction, expression and activity. Cancers. 2003;3:3921–3957. doi: 10.3390/cancers3043921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zou X.-G., Shim Y.Y., Cho J.Y., Jeong D., Yang J., Deng Z.-Y., Reaney M.J.T. Flaxseed orbitides, linusorbs, inhibit LPS-induced THP-1 macrophage inflammation. RSC Adv. 2020;10:22622–22630. doi: 10.1039/C9RA09058D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakano K., Vousden K.H. PUMA, a novel proapoptotic gene, is induced by p53. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:683–694. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zou X.-G., Li J., Sun P.-L., Fan Y.-W., Yang J.-Y., Deng Z.-Y. Orbitides isolated from flaxseed induce apoptosis against SGC-7901 adenocarcinoma cells. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020;71:929–939. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2020.1750573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chinchilla D., Shan L., He P., de Vries S., Kemmerling B. One for all: The receptor-associated kinase BAK1. Trends Plant Sci. 2009;14:535–541. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cory S., Adams J.M. The Bcl2 family: Regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:647–656. doi: 10.1038/nrc883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pérez E.M., Shephard J.L.V., García-Morato M.B., Marhuenda Á.R., Nodel E.M.-O., Bozano G.P., Casado I.G., Fresno L.S., Echevarria A.M., del Rosal Rabes T., et al. Variants in CASP10, a diagnostic challenge: Single center experience and review of the literature. Clin. Immunol. 2021;230:108812. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2021.108812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu X., Lee E.M., Hammack C., Robotham J.M., Basu M., Lag J., Brinton M.A., Tang H. Cell death-inducing DFFA-like effector b is required for hepatitis C. virus entry into hepatocytes. J. Virol. 2015;88:8433–8444. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00081-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Namakura M., Shimada K., Konishi N. The role of HRK gene in human cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:S105–S113. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baker S.J., Reddy E.P. Modulation of life and death by the TNF receptor superfamily. Oncogene. 1998;17:3261–3270. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Volpe E., Sambucci M., Battistini L., Borsellino G. Fas-Fas ligand: Checkpoint of T cell functions in multiple sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2016;7:382. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chu W.-M. Tumor necrosis factor. Cancer Lett. 2013;328:222–225. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Woods D.B., Vousdon K.H. Regulation of p53 function. Exp. Cell Res. 2001;264:56–66. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huo Y., Cao K., Kou B., Chai M., Dou S., Chen D., Shi Y., Liu X. TP53BP2: Roles in suppressing tumorigenesis and therapeutic opportunities. Genes Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2022.08.014. in press . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data of the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.