Abstract

Background

To investigate the complications that occurred in neonates born to mothers with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), focusing on neurological and neuroradiological findings, and to compare differences associated with the presence of maternal symptoms.

Methods

Ninety neonates from 88 mothers diagnosed with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) during pregnancy were retrospectively reviewed. Neonates were divided into two groups: symptomatic (Sym-M-N, n = 34) and asymptomatic mothers (Asym-M-N, n = 56). The results of neurological physical examinations were compared between the groups. Data on electroencephalography, brain ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities were collected for neonates with neurological abnormalities.

Results

Neurological abnormalities at birth were found in nine neonates (Sym-M-N, seven of 34, 20.6%). Decreased tone was the most common physical abnormality (n = 7). Preterm and very preterm birth (P < 0.01), very low birth weight (P < 0.01), or at least one neurological abnormality on physical examination (P = 0.049) was more frequent in Sym-M-N neonates. All infants with abnormalities on physical examination showed neuroradiological abnormalities. The most common neuroradiological abnormalities were intracranial hemorrhage (n = 5; germinal matrix, n = 2; parenchymal, n = 2; intraventricular, n = 1) and hypoxic brain injury (n = 3).

Conclusions

Neonates born to mothers with symptomatic COVID-19 showed an increased incidence of neurological abnormalities. Most of the mothers (96.4%) were unvaccinated before the COVID-19 diagnosis. Our results highlight the importance of neurological and neuroradiological management in infants born to mothers with COVID-19 and the prevention of maternal COVID-19 infection.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pregnancy, Newborn, Neuroradiologic manifestations

Introduction

In December 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first identified in Wuhan, China, and spread worldwide thereafter. The World Health Organization declared the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak a global pandemic on March 11, 2020.1 As of August 2022, over 598 million confirmed cases had been reported globally, with approximately 6.4 million deaths.2 Various neonatal impacts, such as intensive care unit (ICU) admission, severe infection, and severe neonatal morbidity indices,3 have been reported.

Pregnancy complicated by COVID-19, and the adverse effects of this disease on mothers and neonates, have recently been of interest.3, 4, 5, 6 Pregnant women are a high-risk group for severe COVID-197 and are at higher risk for ICU admission,8 severe infection, preeclampsia/eclampsia, and maternal death.3 In addition, several factors, including increased maternal age, high body mass index (BMI), and pre-existing maternal comorbidities, increase the risk of maternal death.8

Complications, such as preterm birth, low birth weight, and higher risk of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, have been reported for neonates born to mothers with COVID-193, 4, 5 , 9; however, the neurological complications and neuroradiological features of neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 remain largely unknown. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the complications that occurred in neonates born to mothers with COVID-19, focusing on the neurological findings and neuroradiological features, and to compare differences associated with the presence of maternal symptoms.

Methods

Study design and participants

Between January 2020 and August 2021, all pregnant women were tested for COVID-19 in our hospital, and mothers diagnosed with COVID-19 using real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests during pregnancy were included in this retrospective study. Mothers without clinical information on age, the date of the RT-PCR test, and the presence or absence of symptoms due to COVID-19, were excluded. We divided the mothers into two groups, based on the presence of symptoms: symptomatic (Sym-M) or asymptomatic (Asym-M). The neonates were divided into two groups, based on the presence of maternal symptoms: born to symptomatic (Sym-M-N) and asymptomatic mothers (Asym-M-N).

Standard protocol approvals, registration, and patient consent

We obtained an institutional review board exemption for including cases from our hospital. Data were acquired in compliance with all applicable Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations.

Data collection

The demographic and clinical data of mothers and neonates were extracted from the electronic medical records. Maternal data included maternal age, BMI, oxygen saturation (SpO2) at delivery, previous medical history, complications during pregnancy and delivery, trimester of COVID-19 diagnosis (first: 1 to 12 weeks, second: 13 to 28 weeks, third: 29 to 40 weeks), whether antenatal steroids were given, and associated symptoms. Neonatal data included sex, term of birth (very preterm: <32 weeks’ gestation; preterm: 32 to 37 weeks’ gestation; term: >37 weeks’ gestation), birth weight, 1- and 5-minute Apgar scores (score <7 considered abnormal), respiratory distress, abnormal neurological findings on physical examination at birth, complications at birth, neurological imaging findings (ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging), and the results of COVID-19 PCR tests within two weeks of birth. The physical examinations and assessments were performed by pediatric neurologists who were not blinded to the mothers' COVID-19 statuses during the study period. All the clinical data were retrospectively assessed by a board-certified radiologist under the supervision of a pediatric neurologist. To determine the presence of “neurological abnormalities,” neurological physical examinations were performed at birth, and data on mental status, cranial nerves (pupils, hearing, sucking, and swallowing), motor function, and reflexes (Moro, asymmetric tonic neck reflex, and palmar grasp) were collected.10 Furthermore, data on placental pathology were extracted from the pathology reports.

Radiological analysis

The decision to order a magnetic resonance imaging was made by the examining physician based on the clinical findings in the neonates. All neuroradiological examinations were independently and blindly interpreted by two board-certified radiologists. Any discrepancies between the radiologists were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached.

Statistical analysis

Continuous and categorical variables are presented as means with S.D. and rates (%), respectively; they were compared between the Sym-M-N and Asym-M-N groups, or the Sym-M and Asym-M groups, using the t test or Mann-Whitney U test as appropriate. The Shapiro-Wilk test was performed to assess the normality of the distribution of the studied groups before each comparison of the continuous variables. When the odds ratio was calculated between the two groups and either group contained 0, 0.5 was added to both the denominator and the numerator (Haldane-Anscombe correction11). We performed familywise error correction using the false discovery rate approach. Familywise error-corrected two-sided P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.0.0; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Data availability

Data were deidentified before the analysis. The underlying deidentified data can be accessed upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the neonates

A total of 90 neonates, including two pairs of twins, and their 88 mothers with confirmed COVID-19, were included in the analysis. The neonates were divided into Sym-M-N (n = 34; M:F = 20:14) and Asym-M-N groups (n = 56; M:F = 30:26). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the neonates are presented in Table 1 .

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Data for Neonates Born to Mothers With COVID-19

| Total Neonates | Born to Mother With Symptomatic COVID-19 (Sym-M-N Group, n = 34 From 33 Mothers) | Born to Mother With Asymptomatic COVID-19 (Asym-M-N group, n = 56 From 55 Mothers) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (n, %) | ||||

| Male: female | 50: 40 | 20: 14 | 30: 26 | 0.81 |

| Term of birth (n, %) | ||||

| Very preterm (<32 weeks) | 7/90 (7.8%) | 7/34 (20.6%) | 0/56 (0%) | <0.01 |

| Preterm (32−37 weeks) | 24/90 (26.7%) | 13/34 (38.2%) | 11/56 (19.6%) | |

| Normal term | 59/90 (65.6%) | 14/34 (41.2%) | 45/56 (80.4%) | |

| Body weight (g, mean ± S.D.) | 3064 ± 875 | 2766 ± 1156 | 3243 ± 595 | 0.08 |

| Very low birth weight (under 1500 g) | 5/90 (5.6%) | 5/34 (14.7%) | 0/56 (0%) | <0.01 |

| Infant complications (n, %) | ||||

| No complications | 42/90 (46.7%) | 8/34 (23.5%) | 34/56 (60.7%) | <0.01 |

| Abnormal symptoms | ||||

| Fever | 5/90 (5.6%) | 2/34 (5.9%) | 3/56 (5.4%) | >0.99 |

| Vomiting | 9/90 (10.0%) | 7/34 (20.6%) | 2/56 (3.6%) | 0.047 |

| Neurological abnormality | 10/90 (11.1%) | 8/34 (23.5%) | 2/56 (3.6%) | 0.016 |

| Abnormal Apgar score (under 7) | 30/90 (33.3%) | 19/34 (55.9%) | 11/56 (19.6%) | <0.01 |

| 1 minute (mean ± S.D.) | 6.1 ± 2.8 | 4.9 ± 3.3 | 6.9 ± 2.5 | 0.006 |

| 5 minute (mean ± S.D.) | 7.6 ± 2.1 | 6.7 ± 2.3 | 8.2 ± 1.7 | <0.001∗ |

| Meconium aspiration syndrome | 3/90 (3.3%) | 3/34 (8.8%) | 0/56 (0%) | 0.02 |

| Small for gestational age | 7/90 (7.8%) | 3/34 (8.8%) | 4/56 (7.1%) | >0.99 |

| NICU admission | 27/90 (30.0%) | 19/34 (55.8%) | 8/56 (14.3%) | <0.01 |

| Respiratory distress | 23/90 (25.6%) | 17/34 (50.0%) | 6/56 (10.7%) | <0.01 |

| Neuroimaging abnormality | 9/17 (36.8%) | 7/11 (63.6%) | 2/6 (33.3%) | 0.48 |

| Stillbirth | 1/90 (1.1%) | 1/34 (2.9%) | 0/56 (0%) | 0.25 |

| Maternal age at the time of delivery (mean ± S.D.) | 29.6 ± 5.4 | 30.5 ± 3.5 | 29.1 ± 6.3 | 0.73 |

| Term at the diagnosis of COVID-19 (n, %) | ||||

| First trimester (1–12 weeks) | 1/90 (1.1%) | 1/34 (2.9%) | 0/55 (0%) | 0.027 |

| Second trimester (13–26 weeks) | 9/90 (10.0%) | 7/34 (20.6%) | 2/55 (3.6%) | |

| Third trimester (27 to the end of the pregnancy) | 80/90 (88.9%) | 26/34 (76.5%) | 54/55 (98.2%) | |

| Maternal COVID-19 symptom (n, %) | ||||

| Admission | 8/86 (9.3%) | 8/30 (26.7%) | 0/55 (0%) | <0.01 |

| ICU admission | 6/86 (7.0%) | 6/30 (20.0%) | 0/55 (0%) | <0.01 |

| Invasive ventilation | 5/86 (5.8%) | 5/30 (16.7%) | 0/55 (0%) | <0.01 |

| Death | 0/86 (0%) | 0/30 (0%) | 0/55 (0%) | >0.99 |

| Maternal BMI (mean ± S.D.) | 33.8 ± 7.5 | 34.7 ± 8.0 | 33.3 ± 7.2 | 0.76 |

| Maternal past medical history (n, %) | ||||

| Positive smoking history | 12/81 (14.8%) | 8/30 (26.7%) | 4/50 (8.0%) | 0.09 |

| Current smoking | 3/81 (3.7%) | 2/30 (6.6%) | 1/50 (2.0%) | 0.73 |

| Former smoking | 9/81 (11.1%) | 6/30 (20.0%) | 3/50 (1.5%) | 0.12 |

| Chronic hypertension | 6/81 (7.4%) | 4/30 (13.3%) | 2/50 (4.0%) | 0.29 |

| Pre-existing diabetes | 5/81 (6.2%) | 4/30 (13.3%) | 1/50 (2.0%) | 0.11 |

| Maternal complications during pregnancy (n, %) | ||||

| Gestational hypertension | 10/81 (12.3%) | 3/30 (10.0%) | 7/50 (14.0%) | 0.85 |

| Gestational diabetes | 5/81 (6.2%) | 4/30 (13.3%) | 1/50 (2.0%) | 0.11 |

| Maternal SpO2 (%) at the time of delivery | 98.3 ± 2.2 | 97.3 ± 3.0 | 98.9 ± 1.2 | 0.07 |

| Maternal complications at the time of delivery (n, %) | ||||

| Chorioamnionitis | 6/81 (7.4%) | 3/30 (10.0%) | 3/50 (6.0%) | 0.59 |

| Placental abruption | 3/81 (3.7%) | 1/30 (3.3%) | 2/50 (4.0%) | >0.99 |

| Preeclampsia | 10/81 (12.3%) | 4/30 (13.3%) | 6/50 (12.0%) | >0.99 |

Abbreviations:

BMI = Body mass index

COVID-19 = Coronavirus disease 2019

ICU = Intensive care unit

NICU = Neonatal intensive care unit

SpO2 = Oxygen saturation

Neurological abnormalities were significantly more frequent in the Sym-M-N group (seven of 34, 20.6%) than in the Asym-M-N group (two of 56, 3.6%, P = 0.049). The most common abnormality was decreased tone (seven of nine, 77.8%), followed by delayed or absent reflexes (five of nine, 55.6%). The neurological characteristics of these nine neonates are summarized in Table 2 . Of the neonates with neurological abnormalities, six (66.7%) were born preterm or very preterm and five (55.6%) were born by emergency Caesarean section. Two neonates had status epilepticus needing three antiseizure medications. Of the neonates with neurological abnormalities, those with decreased sulcation (patient 3) and holoprosencephaly (patient 5) were considered unrelated to their mothers’ COVID-19 infection since these abnormalities start early in the first trimester. Of the nine neonates with neurological abnormalities, electroencephalography was performed in six.

TABLE 2.

Patient Characteristics

| Gestational Age | Sex | Body Weight, g | Infant Comorbidities | Mother's COVID-19 Symptoms and Other Comorbidities | Emergency C Section | Mother's past Medical History | Time from COVID-19 Diagnosis to Delivery, days | Apgar Score, 1 min, 5 min | Neurological Physical Examinations at Birth | EEG | Purpose of MRI | Neuroradiological Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24 w 0 d | M | 680 | Very preterm, respiratory distress syndrome, extremely low birth weight | Symptomatic (cough, sneezing, headache, and vomiting) | - | Diabetes | 17 | 4, 8 | Decreased tone and activity | n/a | n/a | US (day 1) = grade 1 germinal matrix hemorrhage |

| 2 | 28 w 0 d | F | 975 | Very preterm, respiratory distress syndrome, extremely low birth weight | Symptomatic (septic shock and acute organ dysfunction) requiring ICU admission | + | Chronic hypertension | 11 | 1, 6 | Decreased tone and activity | n/a | n/a | US (day 1) = grade 1 germinal matrix hemorrhage |

| 3 | 31 w 1 d | F | 1650 | Very preterm, respiratory distress syndrome, low birth weight, MD twin, IUGR | Symptomatic (shortness of breath, nasal congestion, and tachycardia) | + | None | 51 | 2, 4 | Hypotonic and floppy, intermittent extremity flexion | Standard HIE cEEG protocol; + status epilepticus requiring three antiseizure medications; background attenuated with severe encephalopathy | n/a | US (day 1) = asymmetric ventriculomegaly, decreased sulcation |

| 4 | 31 w 1 d | F | 1985 | Very preterm, respiratory distress syndrome, low birth weight, shoulder dystocia, Pfeiffer syndrome, MD twin, IUGR, meconium aspiration syndrome, cloverleaf deformity, low birth weight, HIE | Symptomatic (shortness of breath, nasal congestion, and tachycardia) | + | None | 51 | 2, 4 | Minimal constriction to light, poor grasp reflex | 2-day cEEG for event capture due to concern for seizurelike activity; focal epileptiform activity without seizures; background mildly encephalopathic | Clinically suspected HIE | MRI (day 5) = restricted diffusion in the bilateral parietal and temporal regions with cortical laminar necrosis |

| 5 | 35 w 1 d | M | 3015 | Preterm, respiratory failure with hypoxia and hypercapnia, multiple congenital anomalies including semilobar holoprosencephaly, preductal coarctation of the aorta, VSD | Symptomatic (acute bronchitis) | - | Diabetes, preeclampsia, BMI >35 kg/m2 | 44 | 4, 7 | Delayed reflex plantar stimulation, decreased sucking reflex, hypotonia | n/a | Prenatally diagnosed hydrocephalus | MRI (day 1) = semilobar holoprosencephaly, ventriculomegaly right frontal lobe hematoma |

| 6 | 35 w 6 d | F | 2440 | Preterm infant, neonatal asphyxia, respiratory failure that required intubation, severe metabolic acidosis, HIE | Asymptomatic, placental abruption | - | Current smoker | 1 | 1, 1 | Decreased tone and activity | Prolonged HIE cEEG protocol due to ongoing seizures (9 days); status epilepticus needing three antiseizure medications; background profoundly suppressed, initially with prolonged interburst interval (burst suppression pattern) that became more continuous toward the end of the study | Clinically suspected HIE | MRI (day 4) = diffuse diffusion restriction in cerebral white matter, intraventricular hemorrhage |

| 7 | 40 w 3 d | M | 3800 | Meconium aspiration syndrome | Symptomatic (tachycardia and ache days) | + | Former smoker | 14 | 1, 3 | Decreased consciousness, sluggish pupils, no Moro reflex, no gag reflex | Standard HIE cEEG protocol; multifocal epileptiform discharges without seizures; background with moderate encephalopathy due to excessive discontinuity and paucity of normal state cycling | Neurological symptoms | MRI (day 6) = decreased NAA/Cr ratio on MRS |

| 8 | 40 w 5 d | M | 5440 | Meconium aspiration syndrome, respiratory failure, HIE | Symptomatic | - | Gestational diabetes | 5 | 1, 5 | Decreased tone and activity, constricted pupils, no gag reflex, no sucking reflex | Standard HIE cEEG protocol; multifocal epileptiform discharges without seizures; background profoundly suppressed, initially with prolonged interburst interval (burst suppression pattern) that became more continuous toward the end of the study; bursts asymmetric, suggesting worse right neuronal function | Clinically suspected HIE | MRI (day 12) = tiny foci of prior ischemic change in the periventricular and deep white matter |

| 9 | 40 w 6 d | M | 3165 | Respiratory failure | Asymptomatic, chorioamnionitis | + | None | 3 | 1, 3 | Lower extremity tone poor, weakness of suck | Standard HIE cEEG protocol; multifocal epileptiform discharges without seizures; background continuous with good state modulation and variability | Neurological symptoms | MRI (day 5) = decreased NAA/Cr ratio on MRS |

Abbreviations:

BMI = Body mass index

C Section = Caesarean section

cEEG = Continuous EEG

COVID-19 = Coronavirus disease 2019

Cr = Creatine

EEG = Electroencephalography

F = Female

HIE = Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

ICU = Intensive care unit

IUGR = Intrauterine growth restriction

M = Male

MD = Monochorionic diamniotic

MRI = Magnetic resonance imaging

MRS = Magnetic resonance spectroscopy

n/a = Not applicable

NAA = N-acetylaspartate

US = Ultrasonography

VSD = Ventricular septal defect

Abnormal Apgar scores (i.e., score <7; P < 0.01), very preterm and preterm births (P < 0.01), NICU admission (P < 0.01), respiratory distress (P < 0.01), very low birth weight (P < 0.01), and meconium aspiration syndrome (P = 0.049) were significantly more common in the Sym-M-N group than in the Asym-M-N group. One neonate, born to a mother who had a cytokine storm in the Sym-M group and was given antenatal steroids, was born preterm, with low birth weight.

COVID-19 testing of the neonates

RT-PCR tests for COVID-19 infection were performed in 54 neonates, and three of the 18 neonates in the Sym-M-N group and one of the 36 neonates in the Asym-M-N group tested positive. All neonates with neurological abnormalities underwent RT-PCR testing for COVID-19 and showed negative results.

Maternal demographic and clinical characteristics

The gestational week in which the COVID-19 diagnosis was made was significantly earlier in the Sym-M group than in the Asym-M group (1 vs 0, 7 vs 2, and 26 vs 54 in the first, second, and third trimesters, respectively; P < 0.01). In the Sym-M group, eight of the 30 mothers (26.7%) were admitted, and five (16.7%) required invasive ventilation. The mothers' age and BMI at the time of delivery, the term at the date of COVID-19 diagnosis, past medical history (smoking history or pre-existing diabetes), and complications (gestational hypertension or diabetes, chorioamnionitis, placental abruption, and preeclampsia) were not statistically different between the two groups. In 25 of the 31 preterm birth mothers, including one mother who had a cytokine storm, antenatal steroids were given for anticipated preterm birth. Of the mothers with a known vaccination status (31 of 33 mothers in the Sym-M group and 52 of 55 mothers in the Asym-M group), all the mothers in the Sym-M group and all but three mothers in the Asym-M group were not vaccinated (vaccinated, three of 83 [3.6%]; unvaccinated, 80 of 83 [96.4%]). Data on placental pathology were available for 55 mothers (20 of 33 in the Sym-M group and 35 of 55 in the Asym-M group). Among the 55 mothers, SARS-CoV-2 RNA in situ hybridization was tested in 13 mothers’ placental tissues (four symptomatic mothers and nine asymptomatic mothers). All but one placental tissue showed negative results. One placenta in the Asym-M group showed rare positive cells as well as acute chorioamnionitis. The neonate born to this mother was normal and healthy.

Neuroradiological findings in neonates born to mothers with COVID-19

All the nine neonates with neurological abnormalities had abnormal neuroradiological findings. The neuroradiological characteristics of the nine neonates are summarized in Table 2. Of the nine neonates with neuroradiological abnormalities, seven were in the Sym-M-N group. All the neonates with neurological abnormalities developed respiratory failure that needed NICU admission. Of these, four (44.4%) were very preterm and two (22.2%) were preterm. The most common imaging feature was intracranial hemorrhage (germinal matrix hemorrhage, n = 2 [22.2%]; parenchymal hemorrhage, n = 2 [22.2%]; intraventricular hemorrhage, n = 1 [11.1%]), followed by hypoxic brain injury (diffuse white matter and magnetic resonance spectroscopy abnormalities, n = 2 [22.2%] each; FIGURE 1, FIGURE 2, FIGURE 3 ). Patient 5, with a right frontal lobe hematoma, was diagnosed with holoprosencephaly, and patient 6, with hypoxic-ischemic injury (HIE), was born to a mother with placental abruption.

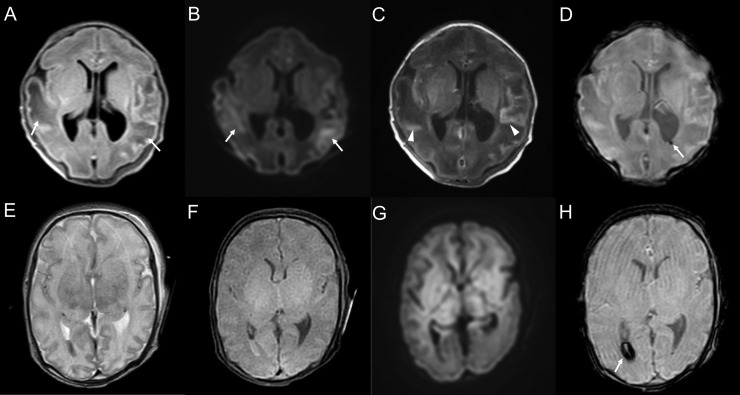

FIGURE 1.

Representative cases with ultrasound abnormalities. A 28-weeks-and-0-day-old female born to a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) symptomatic mother (patient 2). The neonate had very low birth weight and respiratory distress syndrome. She showed decreased muscle tone and decreased activity. Ultrasound on the first day after birth shows a high-echoic lesion in the left caudate nucleus, indicating a grade 1 germinal matrix hemorrhage (A and B; arrows). A 31-weeks-and-1-day-old female, born to a COVID-19 symptomatic mother (patient 3). The neonate had meconium aspiration syndrome and low birth weight. She was hypotonic and floppy. Ultrasound on the first day after birth shows decreased sulcation indicating prematurity and ventriculomegaly (C and D). A 24-weeks-and-0-day-old male born to a COVID-19 symptomatic mother (patient 1). The neonate had neurobehavioral instability. Ultrasound on the first day of birth shows a high-echoic lesion, indicating hemorrhage in the right caudate nucleus (E, arrow) and germinal matrix (F, arrows).

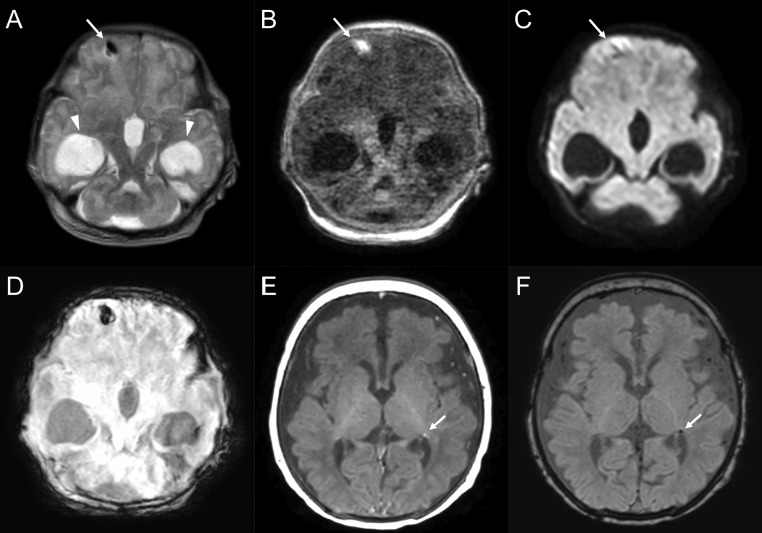

FIGURE 2.

Cases with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. A 31-weeks-and-1-day-old female born to a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) symptomatic mother. The neonate had minimal reaction to physical examination and a cloverleaf skull deformity (patient 4). Magnetic resonance imaging on the fifth day after birth shows bilateral diffuse white matter abnormalities on a fluid-attenuated inversion recovery image (A, arrows), diffusion-weighted image (B, arrows), and T1-weighted image (C, arrows) with cortical T1 hyperintensity corresponding to cortical laminar necrosis (arrowheads). On the susceptibility-weighted image, a microbleed is observed in the left periventricular white matter (D, arrow). A 35-weeks-and-6-day-old female born to a COVID-19 asymptomatic mother who had a placental abruption (patient 6). The neonate had decreased muscle tone and activity. Diffuse signal abnormality in bilateral deep nuclei and white matter is observed on a T2-weighted image (E), T1-weighted image (F), and diffusion-weighted image (G). Intraventricular hemorrhage is observed in the dorsal horn of the right lateral ventricle (H; arrow; susceptibility-weighted image).

FIGURE 3.

Cases with intraparenchymal hemorrhage. A 35-weeks-and-1-day-old male born to a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) symptomatic mother (patient 5). The neonate had delayed bilateral Babinski reflexes, neurobehavioral instability, and hypotonia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on the first day after birth shows bilateral ventriculomegaly (arrowheads), semilobar holoprosencephaly, and intraparenchymal hemorrhage in the right frontal lobe (short arrows; A: T2-weighted image, B: T1-weighted image, C: diffusion-weighted image, D: susceptibility-weighted imaging). A 40-weeks-and-5-day-old male born to a COVID-19 symptomatic mother (patient 8). The neonate had pinpoint pupils and decreased muscle tone, with concern for hypoxemic-ischemic encephalopathy in the setting of meconium aspiration syndrome. MRI on the twelfth day after birth shows a tiny focus of prior ischemic change in the left periventricular white matter (arrows; E: T1-weighted image, F: susceptibility-weighted image).

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study found that neurological abnormalities occurred significantly more frequently in neonates born to mothers with symptomatic COVID-19 compared with those born to asymptomatic mothers (seven of 34 [20.6%] vs two of 56 [3.6%]; P = 0.049). The most common neuroradiological abnormality in the symptomatic newborns born to mothers with COVID-19 infection was intracranial hemorrhage, followed by hypoxic brain injury. Conversely, other clinical features, including age, BMI, past medical history, previous or pregnancy-related complications, and complications at the time of delivery were not statistically different between the two maternal groups. The present study was the first to evaluate and compare the symptoms of the neonates by focusing on the presence or absence of symptoms in the mothers with COVID-19 during pregnancy. The results indicated the increased risk for prematurity and neurological findings in the neonates born to symptomatic mothers.

Given that neurological abnormalities were significantly more common in the Sym-M-N group, symptomatic COVID-19 infection during pregnancy may have resulted in neonatal neurological abnormalities at birth. We suggest that there are two reasons for this: preterm birth and low birth weight and/or the systemic inflammatory response induced by maternal COVID-19 infection.

Increased risks for complications related to COVID-19 and severe COVID-19 infection in pregnant women, compared with nonpregnant women, have been reported.6, 7, 8 , 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 The risk of ICU admission (1.1% to 4.2%) and the need for invasive mechanical ventilation (0.2% to 3%) were reported to be significantly higher among pregnant women.7 , 8 , 13 , 14 For neonates born to mothers with COVID-19, increased risks of complications, such as stillbirth (0.5% to 1.6%), preterm birth (21% to 37.7%), and NICU admission (23.2% to 46.2%), have been reported.6 , 8 , 12 , 14, 15, 16, 17 Previous systematic reviews have reported that 16.6% low birth weight,12 8.1% to 8.3% small for gestational age,6 , 18 1.8% to 13.2% birth asphyxia,12 , 18 and 6.4% respiratory distress syndrome18 occurred among neonates born to mothers with COVID-19. The high incidence of preterm and very preterm birth (31 of 90, 34.5%) and emergency Caesarean delivery (12 of 90, 13.3%) in our population was consistent with the results of a previous meta-analysis8; therefore we considered that there were associations between maternal COVID-19 and increased incidences of preterm and very preterm birth and Caesarean delivery. Moreover, the high frequency of very-low-birth-weight neonates in the Sym-M-N group in the present study (14.7%) was consistent with previous studies, and might be the result of affected fetal growth by maternal infection, as reported in severe acute respiratory syndrome caused by SARS-CoV-1, which is genetically close to SARS-CoV-2.19 , 20 A previous report of 201 neonates born to (mostly symptomatic) mothers with a confirmed diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 showed slightly low Apgar scores at 1 minute.21 In contrast to these studies, respiratory distress syndrome (23 of 90 [25.6%]) and abnormal Apgar scores (30 of 90 [33.3%]) were much more frequent in the present study. These increased frequencies could be partly attributable to the patient population, which included more severe cases, represented by higher ICU admission rates, (six of 86 [7%]) in the current study compared with previous studies. Another possible explanation for this discrepancy is that the previous studies were based on data before the emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B.1.617.2 lineage),22 which has higher hospital admission and emergency care attendance risk23 and lower efficacy of vaccines,24 compared with the alpha variant.

Maternal inflammation during pregnancy may affect fetal brain development and may lead to neuronal dysfunction and behavioral abnormalities.25 COVID-19 is known to induce a cytokine storm and subsequent multiple organ inflammation, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome.26, 27, 28, 29, 30 In the present study, one mother in the Sym-M group was diagnosed with a cytokine storm, and the neonate born to this mother was preterm and had a low birth weight (appropriate for gestational age). Cases with pathologically proven placental vasculopathy complicated with chronic villitis31 and direct placental SARS-CoV-2 infection24 have also been reported; however, no conclusive evidence of vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to the fetus has been found. These findings indicate that inflammation in the maternal body caused by COVID-19 may have adverse implications for the development of the fetus due to increased cytokine activation and/or viral infection at the maternal-fetal interface.

Reports about the neurological and neuroradiological features of neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 are limited. A prospective cohort study from Sweden observed moderate to severe HIE in three of the 2323 infants (0.1%) born to mothers with COVID-19, and severe brain injury, including intraventricular hemorrhage grades 3 to 4 or cystic periventricular leukomalacia, was observed in one of the 34 infants with very preterm births (2.9%)32; however, information on the severity of the illness in their mothers was not available. Sukhikh et al. reported on the case of a 27-year-old woman, diagnosed with COVID-19 in the twenty-first week of pregnancy, who was admitted to the hospital with moderate symptoms (fever and bilateral pneumonia).33 Neurosonography in the twenty-fifth week of pregnancy revealed periventricular leukomalacia, intraventricular hemorrhage, and partial agenesis of the corpus callosum. The neonate died two days after birth, and the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in placental tissue and umbilical cord blood was indicated. Placental pathology revealed extensive infarctions of the placenta on the maternal and fetal surfaces.

The neuroradiological abnormalities found in the present study can be classified into the following categories: hypoxic/ischemic, hemorrhagic (germinal matrix, intraparenchymal), hypoplasia/aplasia, and others. The mechanisms of these abnormalities may be complicated by multiple contributing factors. Neonatal HIE and germinal matrix hemorrhage are typically caused by severe asphyxia and decreased gestational age, respectively.34 The incidence of HIE is 1.5 per 1000 live births.35 The overall incidence of germinal matrix hemorrhage ranges from 20% to 25% among preterm infants.36 The incidence of HIE (Sym-M-N group, two of 34; Asym-M-N group, one of 56; 3.0% in total) and germinal matrix hemorrhage among very-low-birth-weight infants (Sym-M-N group, two of five [40%]) was higher in the present study when compared with what was reported in the literature on neonates born to mothers irrespective of COVID-19 diagnosis.37 , 38 However, the number of the present study is small, and we cannot conclude that there is a statistically significant difference. Regarding patient 5, with right frontal lobe hematoma and holoprosencephaly, and patient 6 with HIE and maternal placental abruption, the neurological and neuroradiological sequelae might not be associated with maternal COVID-19 infection. The incidence of HIE in the neonates in the present study was 3.0% (three of 90 neonates: one term neonate in the Sym-M-N group, one preterm neonate in the Asym-M-N group, and one very preterm neonate in the Sym-M-N group). Although this incidence was higher than that in the term population (0.1% to 0.2%39), the high incidence of preterm and very preterm births in the present study (26.7% and 7.8%, respectively) might have affected the result. Nayak et al. reported a similar incidence of neonatal HIE (3.6%) in neonates born to mothers with COVID-19; however, whether the neonates with HIE were term or not was not described in their study.37 Further study is necessary to clarify whether maternal COVID-19 infection increases the incidence of HIE in term, preterm, and very preterm neonates. Given the significantly higher occurrence of very preterm, preterm, and very-low-birth-weight neonates in the Sym-M-N group, a higher occurrence of germinal matrix hemorrhage is expected due to decreased gestational age and birth weight. Two neonates in the Sym-M-N group showed ventriculomegaly in the present study (patients 3 and 5). Although ventriculomegaly, secondary to holoprosencephaly, is likely unrelated to maternal COVID-19 infection as mentioned earlier, ventriculomegaly in patient 3 could be associated with maternal COVID-19 infection, similar to the previous reported cases.38 , 40

The results of the present study indicate that symptomatic maternal COVID-19 infection may increase the risk of neurological adverse events in neonates. To reduce the risk of unfavorable outcomes in neonates, various measures to prevent maternal COVID-19 infection should be taken, and pregnant women should seek prompt medical care if they are infected. Recent studies have shown that receiving an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine before conception or during pregnancy is not associated with an increased risk of adverse effects on pregnancy course and outcomes.41 , 42 Since vaccinations are highly effective in preventing symptomatic and asymptomatic COVID-19 infections,43 clear communication to improve mothers’ awareness of the safety and efficacy of vaccination is important.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a single-center retrospective study with a small number of patients. Second, the risk of including cases with false-positive COVID-19 RT-PCR test results and excluding cases with false-negative test results exists in both groups. Third, information about the virus variants could not be obtained. Since the delta variant is a more contagious virus that may cause more severe illness,23 determining the correlation between neurological outcomes and the type of virus variants is desirable. Fourth, the possibility that the neurological abnormalities of the neonates were not related to the mothers’ COVID-19 but accidental complications cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, the correlation and independence of each abnormality has not been elucidated due to the lack of a sufficient number of cases. Fifth, the frequency of the neuroradiological findings might have been affected by selection bias since neuroradiological examinations were performed only in symptomatic neonates. The neuroradiological abnormalities were considered to be associated with neurological symptoms, so their frequencies were not independent of each other, but correlated. Sixth, since almost all the mothers were not vaccinated in the present study, the difference in maternal and neonatal outcomes between vaccinated and unvaccinated pregnant women is unknown. Further studies are necessary to address this issue. Seventh, we only collected data on SpO2 at the time of delivery. Continuous SpO2 monitoring may have provided a better understanding of the relationship between maternal oxygenation status and neonatal neurological outcomes.

In conclusion, the Sym-M-N group tended to have more neurological and associated neuroradiological abnormalities than the Asym-M-N group. Very preterm and preterm birth, very low birth weight, low Apgar score, NICU admission, and respiratory distress were frequently found in both groups. Almost all the mothers (96.4%) were not vaccinated before COVID-19 infection. These results highlight the importance of neurological and physical assessment, including neuroradiological examinations, in neonates born to mothers with COVID-19, as well as the importance of prevention of maternal COVID-19 infection.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations of interest: None.

References

- 1.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 – 31 August 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19--31-August-2022

- 3.Villar J., Ariff S., Gunier R.B., et al. Maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality among pregnant women with and without COVID-19 infection: the INTERCOVID multinational cohort study. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:817–826. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L., Li Q., Zheng D., et al. Clinical characteristics of pregnant women with Covid-19 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e100. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karasek D., Baer R.J., McLemore M.R., et al. The association of COVID-19 infection in pregnancy with preterm birth: a retrospective cohort study in California. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2021.100027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neef V., Buxmann H., Rabenau H.F., Zacharowski K., Raimann F.J. Characterization of neonates born to mothers with SARS-CoV-2 infection: review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Neonatol. 2021;62:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zambrano L.D., Ellington S., Strid P., et al. Update: characteristics of symptomatic women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status - United States, January 22-October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1641–1647. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6944e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allotey J., Stallings E., Bonet M., et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m3320. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei S.Q., Bilodeau-Bertrand M., Liu S., Auger N. The impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2021;193:E540–E548. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.202604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang M. Newborn neurologic examination. Neurology. 2004;62:E15–E17. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.7.e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawson R. Small sample confidence intervals for the odds ratio. Commun Stat Simulat Comput. 2004;33:1095–1113. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lassi Z.S., Ana A., Das J.K., et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of data on pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19: clinical presentation, and pregnancy and perinatal outcomes based on COVID-19 severity. J Glob Health. 2021;11 doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.05018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan D.S.A., Pirzada A.N., Ali A., Salam R.A., Das J.K., Lassi Z.S. The differences in clinical presentation, management, and prognosis of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 between pregnant and non-pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:5613. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ko J.Y., DeSisto C.L., Simeone R.M., et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes, maternal complications, and severe illness among US delivery hospitalizations with and without a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) diagnosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:S24–S31. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mullins E., Hudak M.L., Banerjee J., et al. Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes of COVID-19: coreporting of common outcomes from PAN-COVID and AAP-SONPM registries. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;57:573–581. doi: 10.1002/uog.23619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matar R., Alrahmani L., Monzer N., et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of pregnant women with coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:521–533. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jafari M., Pormohammad A., Sheikh Neshin S.A., et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women with COVID-19 and comparison with control patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. 2021;31:1–16. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoon S.H., Kang J.M., Ahn J.G. Clinical outcomes of 201 neonates born to mothers with COVID-19: a systematic review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:7804–7815. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202007_22285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lam C.M., Wong S.F., Leung T.N., et al. A case-controlled study comparing clinical course and outcomes of pregnant and non-pregnant women with severe acute respiratory syndrome. BJOG. 2004;111:771–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong S.F., Chow K.M., Leung T.N., et al. Pregnancy and perinatal outcomes of women with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:292–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chamseddine R.S., Wahbeh F., Chervenak F., Salomon L.J., Ahmed B., Rafii A. Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a systematic review. J Pregnancy. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/4592450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheikh A., McMenamin J., Taylor B., Robertson C. Public Health Scotland and the EAVE II Collaborators. SARS-CoV-2 Delta VOC in Scotland: demographics, risk of hospital admission, and vaccine effectiveness. Lancet. 2021;397:2461–2462. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01358-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Twohig K.A., Nyberg T., Zaidi A., et al. Hospital admission and emergency care attendance risk for SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) compared with alpha (B.1.1.7) variants of concern: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:35–42. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00475-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tao K., Tzou P.L., Nouhin J., et al. The biological and clinical significance of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat Rev Genet. 2021;22:757–773. doi: 10.1038/s41576-021-00408-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mor G., Aldo P., Alvero A.B. The unique immunological and microbial aspects of pregnancy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:469–482. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marini J.J., Gattinoni L. Management of COVID-19 respiratory distress. JAMA. 2020;323:2329–2330. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conti P., Ronconi G., Caraffa A., et al. Induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1 and IL-6) and lung inflammation by Coronavirus-19 (COVI-19 or SARS-CoV-2): anti-inflammatory strategies. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2020;34:327–331. doi: 10.23812/CONTI-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basu S., Agarwal P., Anupurba S., Shukla R., Kumar A. Elevated plasma and cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha concentration and combined outcome of death or abnormal neuroimaging in preterm neonates with early-onset clinical sepsis. J Perinatol. 2015;35:855–861. doi: 10.1038/jp.2015.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sherer M.L., Lei J., Creisher P.S., et al. Pregnancy alters interleukin-1 beta expression and antiviral antibody responses during severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:301.e1–301.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia-Flores V., Romero R., Xu Y., et al. Maternal-fetal immune responses in pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2. Nat Commun. 2022;320:13. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27745-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsu A.L., Guan M., Johannesen E., et al. Placental SARS-CoV-2 in a pregnant woman with mild COVID-19 disease. J Med Virol. 2021;93:1038–1044. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norman M., Navér L., Söderling J., et al. Association of maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy with neonatal outcomes. JAMA. 2021;325:2076–2086. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.5775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sukhikh G., Petrova U., Prikhodko A., et al. Vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in second trimester associated with severe neonatal pathology. Viruses. 2021;447:13. doi: 10.3390/v13030447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan A.P., Svrckova P., Cowan F., Chong W.K., Mankad K. Intracranial hemorrhage in neonates: a review of etiologies, patterns and predicted clinical outcomes. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2018;22:690–717. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurinczuk J.J., White-Koning M., Badawi N. Epidemiology of neonatal encephalopathy and hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parodi A., Govaert P., Horsch S., Bravo M.C., Ramenghi L.A., eurUS.brain group Cranial ultrasound findings in preterm germinal matrix haemorrhage, sequelae and outcome. Pediatr Res. 2020;87:13–24. doi: 10.1038/s41390-020-0780-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nayak M.K., Panda S.K., Panda S.S., Rath S., Ghosh A., Mohakud N.K. Neonatal outcomes of pregnant women with COVID-19 in a developing country setup. Pediatr Neonatol. 2021;62:499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2021.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Düppers A.L., Bohnhorst B., Bültmann E., Schulz T., Higgins-Wood L., von Kaisenberg C.S. Severe fetal brain damage subsequent to acute maternal hypoxemic deterioration in COVID-19. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;58:490–491. doi: 10.1002/uog.23744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gopagondanahalli K.R., Li J., Fahey M.C., et al. Preterm hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Front Pediatr. 2016;4:114. doi: 10.3389/fped.2016.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Archuleta C., Wade C., Micetic B., Tian A., Mody K. Maternal COVID-19 infection and possible associated adverse neurological fetal outcomes, two case reports. Am J Perinatol. 2022;39:1292–1298. doi: 10.1055/a-1704-1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wainstock T., Yoles I., Sergienko R., Sheiner E. Prenatal maternal COVID-19 vaccination and pregnancy outcomes. Vaccine. 2021;39:6037–6040. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blakeway H., Prasad S., Kalafat E., et al. COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy: coverage and safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226:236.e1–236.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haas E.J., Angulo F.J., McLaughlin J.M., et al. Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: an observational study using national surveillance data. Lancet. 2021;397:1819–1829. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00947-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data were deidentified before the analysis. The underlying deidentified data can be accessed upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.