Abstract

One of the most significant threats to global health since the Second World War is the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to COVID-19 widespread social, environmental, economic, and health concerns. Other unfavourable factors also emerged, including increased trash brought on by high consumption of packaged foods, takeout meals, packaging from online shopping, and the one-time use of plastic products. Due to labour shortages and residents staying at home during mandatory lockdowns, city municipal administrations' collection and recycling capacities have decreased, frequently damaging the environment (air, water, and soil) and ecological and human systems. The COVID-19 challenges are more pronounced in unofficial settlements of developing nations, particularly for developing nations of the world, as their fundamental necessities, such as air quality, water quality, trash collection, sanitation, and home security, are either non-existent or difficult to obtain. According to reports, during the pandemic's peak days (20 August 2021 (741 K cases), 8 million tonnes of plastic garbage were created globally, and 25 thousand tonnes of this waste found its way into the ocean. This thorough analysis attempts to assess the indirect effects of COVID-19 on the environment, human systems, and water quality that pose dangers to people and potential remedies. Strong national initiatives could facilitate international efforts to attain environmental sustainability goals. Significant policies should be formulated like good quality air, pollution reduction, waste management, better sanitation system, and personal hygiene. This review paper also elaborated that further investigations are needed to investigate the magnitude of impact and other related factors for enhancement of human understanding of ecosystem to manage the water, environment and human encounter problems during epidemics/pandemics in near future.

Keywords: COVID-19, Environmental concern, Water and air pollution, Environmental imbalance, Health risks

1. Introduction

The historical background of human coronaviruses started in 1965 when Tyrrell and Bynoe discovered a virus called B-814 (Tyrrell and Bynoe, 1965). The virus was present in human embryonic tracheal organ cultures taken from an adult's respiratory tract with common cold symptoms. Hence, it was not surprising when a new, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) appeared in the form of the coronavirus from southern China and spread all around the world with haste in 2002 and 2003 (Drosten et al., 2003; Ksiazek et al., 2003; Peiris et al., 2003). SARS was reported in twenty-nine countries in South America, North America, Asia, and Europe during the 2002-2003 outbreaks. Global virus strain outbreaks from the past 50 years are shown in Table 1 . When a person is in close proximity (within 1 m) to someone who is coughing or sneezing, they are in danger of having their mucosae (mouth and nose) or conjunctiva (eyes) exposed to potentially infectious respiratory droplets. Fomites in the area surrounding the afflicted person may also transmit the disease. As a result, the COVID-19 virus can spread through direct contact with infected people and indirect contact with nearby surfaces or. Droplet transmission refers to the presence of microbes within droplet nuclei, typically particles with a diameter of less than 5 µm. On the other hand, airborne transmission implies that there are microbes in the air that can be transported more than 1 m and infect others (Shah et al., 2022).

Table 1.

Global virus strain outbreaks from the past 50 years.

| Strain/Virus | Year | Patient | Illness | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B814 | 1960 | Youth | Common cold | Tyrrell and Bynoe (1965) |

| 229E | 1962 | Young adult | Minor URI (Upper Respiratory infection) | Hamre and Procknow (1966) |

| OC43 | 1966 | Young adult | URI | McIntosh et al. (1967b) |

| 692 | 1966 | 29 year, male | URI | Kapikian et al. (1973) |

| NL63 | 2004 | 7-month old child | conjunctivitis and bronchiolitis | Fouchier et al. (2004); van der et al. (2004) |

| HKUI | 2005 | 71-year-old man | pneumonia | Woo et al. (2005) |

| SARS-CoV | 2003 | Humans | Respiratory infection | Rota et al. (2003) |

| SARS-CoV-2 | 2019 | More adult than children | Respiratory infection | WHO (2020) |

| SARS Variant Alpha B.1.1.7 |

Sep, 2020 | Variation in Patients | Respiratory infection | WHO (2020) |

| Beta B.1.351 | May, 2020 | Variation in Patients | Respiratory infection | WHO (2020) |

| Gamma P.1 | Nov, 2020 | Variation in Patients | Respiratory infection | WHO (2020) |

| Delta B.1.617.2 | Oct, 2020 | Adult | Respiratory infection | WHO (2020) |

| Omicron B.1..1.529 | Nov, 2021 | Child | Respiratory infection | WHO (2020) |

| Lambda C.37 | Dec, 2020 | Older | Respiratory infection | WHO (2020) |

| Mu B.1.621 | Jan, 2021 | Variation in Patients | Respiratory infection | WHO (2021) |

Data Updated on 6th July 2022 Source: https://covid19.who.int/

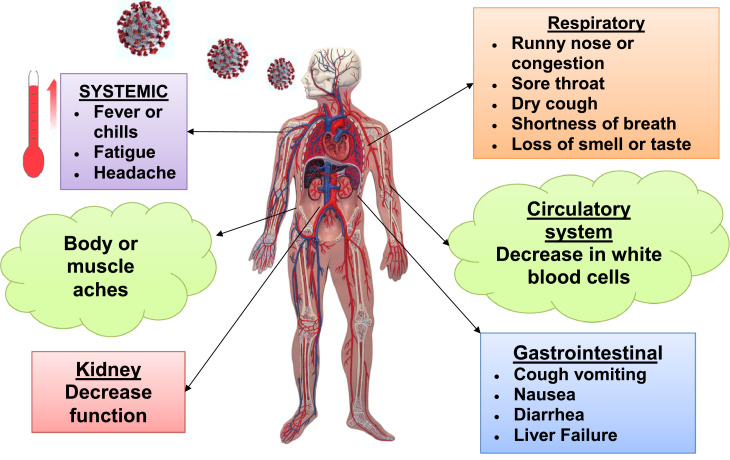

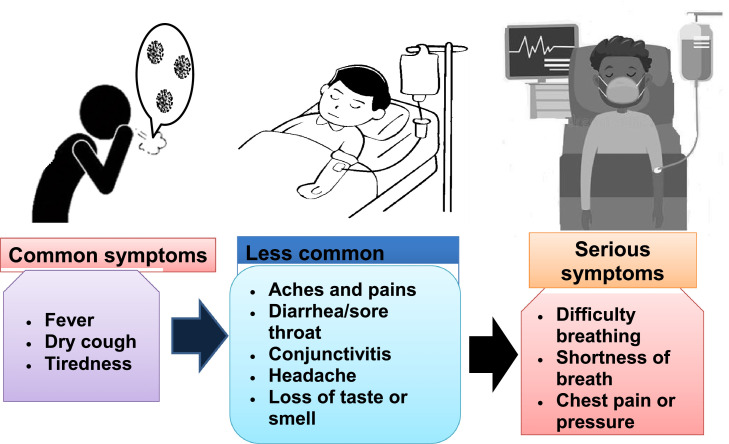

Initially, the novel coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2 was identified in Wuhan, China, and dangerously spread in the large region of Hubei and then across China. At an early stage, the world was informed about the first cases; however, many countries did not expect the immediate health risk the virus presented. At the end of January 2020, a novel disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 was named COVID-19. Later, the World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed that the disease was a public health emergency (Ali et al., 2020) and characterized it as a contagious pandemic on March 11, 2020 (Green, 2020). Globally, 205 million cases and 4.3 million deaths due to COVID-19 were reported on August 10, 2021 (STATISTA 2021). A new variant of the SARS-COVID was reported to the WHO from South Africa on 24th November 2021. Another recent variant was the Delta variant (Omicron), officially designated as B.1.1.529, whose specimen first collected on 9th November 2022 (Fidan et al., 2022). Data on the spread of COVID-19 has been gathered from different countries worldwide. The data showed that the United States had the most significant number of infections, followed by India, Brazil, etc. The latest global statistics on the COVID-19 pandemic can be seen in the supplementary file (Organization, 2020). Individuals with COVID-19 have many symptoms, ranging from mild indications to deadly diseases. One to two days after contact with the virus, symptoms may appear. Individuals with these indications, such as chills or fever, shortness of breath, dry cough, body or muscle aches, fatigue, sore throat, headache, the loss of smell or taste, runny nose or congestion, diarrhoea, vomiting or nausea, may have COVID-19 (Figs. 1 and 2 ).

Fig. 1.

Systematic representation of Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection symptoms of different organs in the human body.

Fig. 2.

Stages of Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection symptoms in humans.

Starting in China, the virus spread to Thailand, Iran, South Korea, and Japan and then into Europe through air travel (Cereda et al., 2020). Initially, the most affected country in Europe was Italy, especially the region of Lombardy, and the cases started to multiply without much knowledge of what was present. Later, the outbreak entered the America (Cereda et al., 2020). Due to air travel, countries are interconnected and depend on different regions to conduct business. Hence, the virus spread rapidly around the world. The United States' response to the COVID-19 pandemic has caused several unexpected economic and market effects (Nilashi et al., 2020). According to a New York Times report (Gössling et al., 2020). For example, daily life has been disturbed for many months, and a significant portion of the population has more health issues (FITBIT, 2020). Strict action by the government made restrictions such as banning movement (e.g., travel restrictions, curfews, etc.), and the number of daily life opportunities declined (e.g., stores closed, restaurants closed, health/fitness centres closed, etc.). Prices of goods increased or became difficult to obtain (e.g., food). The combined effect increased the negative impact on the environment, daily life (e.g., food security and livelihood), water quality, and the economy at a global level. Social distance and especially hygiene were marked as a standard operating procedure (SOP) for rapid protection against COVID-19 by the WHO. It has brought a number of changes to the environment in different countries. It has been recorded that air pollution has been reduced due to a significant reduction in toxic gas emissions (NOx, CO, and other gases) in most countries with restrictions (Nilashi et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). The pandemic of COVID-19 has also indirectly impacted animal life, especially wildlife. Considering direct or indirect effects, actions are needed to control the impact of COVID-19. Lal et al. (2020a) reported that essential factors such as air pollution, temperature, and humidity are directly affected by the expansion of COVID-19 (Lal et al., 2020).

This study hypothesizes that the COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacts water quality, the environment, land pollution, the sanitation system, and human lives differently. One of the most important factors is the unawareness or lack of information on the impact of COVID-19. Thus, there is a need to study the critical impacts of COVID-19 in detail to generate fundamental knowledge of the factors that affect environmental sustainability in different ways. Finally, the findings of this review paper will help decision-makers and policymakers count the challenges and develop new regulations to achieve environmental sustainability.

2. Methodology

The methodology of this study was to summarise data related to the environment (air, soil, and water), human systems, and COVID-19 and to develop the links between them. The data used for this review has been collected from different sources that provided global information related to COVID-19. The essential literature sites used were Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Research Gate, Science Direct, official updated data by the World Metrology Organization (WMO), and the WHO. The collected data comprised observations, research articles, viewpoints, and information obtained during the pandemic.

3. World region economic cost situation

Table 2 shows that European regions have the maximum number of infected individuals and the highest death rate per 100,000 individuals, followed by the Americas, the Eastern Mediterranean region, and so on (WHO, 2020). At first, the discernment was that COVID-19 would be limited to China, but later on it spread worldwide via individual movements. Financial crises occurred because individuals were advised to remain at home. The seriousness was felt in different economic zones, with travel bans influencing the sports industry, aviation industry, agriculture and mass-crowd prohibition influencing the entertainment and events industries (Larry Elliot, 2020). Amidst the worldwide turbulence, in a primary evaluation, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) anticipated China's economic growth rate to decrease by 0.4% when China's development targeted a 5.6% growth rate. Hence, the worldwide economy decreased by 0.1% (Aguiar et al., 2019). The Chinese economy represents around 16% of the world's Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and it is the most prominent exchange companion of most African nations and Southeast Asia (Aguiar et al., 2019). The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimated the reduction in economic development rates as follows: China will grow at a rate of 4.9% rather than 5.7%, Europe will grow at a rate of 0.8% rather than 1.1%, and the rest of the world will grow at a rate of 2.4% rather than 2.9%, with global GDP falling by 0.41% in the first quarter of 2020. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) stated a downward trend of 5% to 15% in foreign direct investments. On March 23, 2020, the IMF announced that since the beginning of the crisis, investors had pulled back $83 billion from emerging markets (Chepeliev, 2020). The coronavirus occurrence has led numerous governments to compel limitations on unnecessary journeys. Even certain countries set an entire travel prohibition on a wide range of internal and external travel, shutting down all airports in the country. At the peak of the coronavirus outbreak, most aircraft flew approximately devoid of passengers because of mass travel boycotts and prohibition (Jagannathan et al., 2013). The travel limitations forced by governments afterward provoked a lessening enthusiasm for a wide range of travelwhich compelled some companies to briefly suspend activities such as Line of Travel (Rolland et al., 2012), Polish Airlines, Air Baltic, Scandinavian and La Compagnie Airlines. According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), such travel restrictions cost the tourism industry over $200 billion globally, and excluding other income losses for the industry, cost the flying industry $113 billion. US airline companies received $50 billion in bailout money to combat such losses. The Global Business Travel Association (GTBA) estimated that the commercial travel industry would lose $820 billion in revenue due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Table 2.

COVID-19 global pandemic statistics showing the total number of cases, cases per 100,000 people, total deaths, deaths per 100,000 people and major transmission types at the regional level according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

| Region | Total cumulative cases | Cumulative cases per 100,000 people | Total cumulative deaths | Cumulative deaths per 100,000 people | Major transmission type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 9,138,808 | 32,456.9 | 78,140 | 469.54 | Community transmission |

| Americas | 163,881,638 | 26218.1 | 1008832 | 2127 | Community transmission; clusters of cases |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 7,564,704 | 59,129.59 | 158,961 | 651.09 | Community transmission |

| Europe | 230,320,699 | 351,594.09 | 969,779 | 6,346.4 | Community transmission; clusters of cases |

| South-East Asia | 58,692,921 | 8,110.85 | 219,797 | 63.83 | Community transmission; clusters of cases |

| Western Pacific | 64,851,400 | 19,050.85 | 31,685 | 202.19 | Sporadic cases; clusters of cases |

| Others | 745 | 0 | 13 | 0 |

Source: (WHO, 06 July 2022) https://covid19.who.int/table.

The COVID-19 outbreak has also tested the resilience of the agricultural division. Globally, the closing of restaurants and hotels has declined the consumption of agricultural commodities by 20% (Bhosale, 2020). Upon interaction with speculated carriers of the virus, recommendations on self-quarantine will most likely influence the number of available inspectors and distribution staff critical to ensuring affirmation and transportation of products. Besides this, markets have also shuttered down the trading of commodities, drastically influencing The American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) has conveyed anxiety over low levels of animal pharmaceuticals for a couple of large prescription suppliers (Jagannathan et al., 2013). Several hotels in the United Kingdom, the United States, and some European countries announced a temporary exercise halt. It was estimated that 24.3 million jobs will be lost, including 3.9 million in the US alone, because of the reduction in hotel guests during the outbreak. Due to disruption due to self-isolation policies and supply chains, importation problems and staffing insufficiencies were the main issues for businesses (Barro, 2015). The chemical industry is estimated to decrease its global production by 1.2%, and the economy has gone toward a drastic loss (Bentolila et al., 2018). Central chemical manufacturing enterprises like Baden Aniline and Soda Factory (BASF) have been required to defer their production, adding to a slowdown in expected development (Bezemer, 2011). The February 2020 announcement on the Chinese significant workshop action and market manufacturing index that the Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) recorded a minimum at that time (El-Erian, 2020). "China's industrial economy was influenced by an outbreak a month ago," said Zhengsheng Zhong, principal economist at the group Centre for Evidence-based Medicine (CEBM) (Horowit, 2020). While the Chinese labor force is returning to work, the PMIs across East Asia have shown sharp decreases, especially in Taiwan, Japan, Vietnam, and South Korea (Wang et al., 2020). The sports industry was also seriously affected throughout the outbreak. Many other important markets, for instance, oil, coal, and sustainable energy also significantly influenced by the pandemic. The coronavirus occurrence also influenced the supply chain of pharmaceuticals. Before the coronavirus outbreak, 60% of active pharmaceutical components were made in China, and the pandemic caused severe supply chain problems. Therefore, China closed many of its workshops that produce drugs. Hence, every economic sector has been directly and indirectly affected due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

4. Socioeconomic and environmental aspects of COVID-19

Socioeconomic factors have shown that the effect of COVID-19 is not the same for everyone (Collivignarelli et al., 2020). It is difficult to know why COVID-19 varies from person to person and among different socioeconomic populations. The most critical elements affecting an individual's socioeconomic status are their educational level, population density (rural and urban settings), lifestyle, and the size of houses and number of members in a household. Unfortunately, it was found that the spread of cases was higher in poor and less developed regions (Messner, 2020). The current literature on COVID-19 shows that in populations with a lower socioeconomic status, COVID-19 cases are higher with higher infection rates than in populations in higher income areas. The New York City research report showed that less developed residential areas have a significantly higher infection rate than other areas of the same city.

5. COVID-19 and the global environment

The pandemic has significantly impacted the environment over a short duration. Almost all countries limited international flights to combat the spread of the virus. It has been stated that the resources of a country play an essential role in implementing preventive or control measures (Zhu et al., 2020). However, the situation is worse in developing countries, where the population density is usually high. In such countries, social distancing is minimized due to huge gatherings and a lack of public healthcare services, which cause high infection rates. Similarly, worldwide institutions should have followed strict SOPs to reduce infections and minimize the 2nd and 3rd waves of COVID-19. Historical analysis shows that the 2nd wave of COVID-19 was more prominent and lethal than the 1st wave, even though cases were reduced. The pandemic has changed the world's social life and economic status immensely. Every country has implemented different strategies to combat this pandemic (Debiec-Andrzejewska et al., 2020). However, a short-term shutdown of industry, business, and transportation has reduced the emission of greenhouse gases (GHG) compared to previous years. Air quality is a crucial element of a healthy life; however, about 91% of the world's population lives in places where the low air quality surpasses the allowable limit (Zhang et al., 2017). The report showed that the most influential countries belong to Asia, Africa, and a part of Europe, with an average air quality of 8% (WHO, 2021). It has been reported that GHGs dropped by 40% and 50% in China and New York City, respectively, with a global drop of 25% in GHGs during the 3-month peak of COVID-19 (Gautam, 2020). In another study in Salé (North-Western Morocco), NO2 concentrations decreased by 96% (Ocak and Turalioglu, 2008).

Environmental factors incorporate air pollution, noise pollution, water pollution, depletion of the ozone layer, climate change, groundwater level depletion, arsenic contamination, biodiversity, ecosystem change, etc. (Bremer et al., 2019). Due to the increasing GHG emissions (CO2, N2O, CH4, etc.), global warming occurs, and these gases are also called the driving forces of air pollution (Lyu et al., 2016). The Air Quality Index (AQI) and health breakpoints for different pollutants, along with possible impacts, are presented in Tables 3 and 4 . The presence of NO2, PM10, and SO2 in urban environments causes air pollution and is an indirect cause of severe health issues such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, lung cancer, and hypertension (Koken et al., 2003; Le Tertre et al., 2002). These pollutants emerge from anthropogenic sources including suspended particles from wheel turbulence, street traffic, and industrial activities (He et al., 2019; Thorpe and Harrison, 2008). According to studies, coal combustion produces high air pollutants such as particulate matter (PM), NO2, CO2, SO2, and heavy metals (Munawer, 2018). Additionally, the buildup of these contaminants in the water and air causes a hazard to ecological systems (Raza et al., 2022).

Table 3.

Air Quality Index (AQI) categories and health breakpoints for different pollutant. Pollutants include particulate matter < 10 μm (PM10) and < 2.5 μm (PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), ozone(O3), carbon monoxide (CO), sulfur dioxide (SO2), ammonia (NH3) and lead (Pb).

|

*CO in mg/m3 and other pollutants in µg/m3; 2 hourly average values for PM10, PM2.5, NO2, SO2, NH3 and Pb; 8-hourly values for CO and O3; (The Colour Green to Red shows increasing toxicity level).

Table 4.

Air Quality Index (AQI) and possible health impacts of air standards on human health.

|

(The Colour Green to Red shows increasing toxicity level).

5.1. Nitrogen dioxide (NO2)

Nitrogen dioxide is a significant source of pollution, which is not only injurious to human health-but also significantly affects biodiversity (Reale et al., 2019; Verburg and Osseweijer, 2019). Long-term exposure to high NO2 concentrations disturbs the respiratory system and causes many other harmful lung diseases, asthma, skin problems, etc. (Arden et al., 2004). Short-term exposure to high NO2 concentrations can cause respiratory indications and intensify respiratory maladies. Additionally, it has been recorded that short and long-term exposure increased mortality rates. It has also been stated that about 2.6 million people are affected by bad air quality (Cohen et al., 2017). Nitrogen dioxide and nitrogen monoxide (NO) cause smog and acid rain, damaging the environment (Akimoto, 2003). Nitrogen dioxide is known as a NO marker and is utilized to evaluate stages of environmental pollution (Wang et al., 2018). According to an Environmental Site Assessment (ESA) report, NO2 was reduced by 20-30% in France, Italy, and Spain during lockdown measures. It was also noted that NO2 reduction was higher in Asian countries than in European countries during the lockdown period. Asian countries have dealt with the pandemic uniquely, and Asian countries adopted travel restrictions and lockdown measures much earlier than the rest of the world. It is thought that cases and death rates were lower in Asian countries due to early restrictions compared to European countries. The positive air quality during the pandemic and unwanted lockdown is an indication for individuals and researchers/scientists to improve the quality of the environment by reducing NO2 levels in the air (Zhou et al., 2020).

5.2. Particulate matter (PMx)

Air is considered a medium to transfer viruses, bacteria and other organisms into the environment (Piazzalunga-Expert, 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). Recently, it has been reported that the presence of PM in the air may increase the spread of COVID-19 (Barakat et al., 2020). Particulate matter is an air-suspended mixture of liquid and solid particles which are hazardous to one's health. Their size varies from particle to particle based on the diameter of the matter. The most notable of these sizes are PM10 and PM2.5, with diameters of less than 10 and 2.5 micrometers, respectively (Khan et al., 2019; Zoran et al., 2019). These fine microparticles are categorized as toxic elements for human health and are produced in combustion engines. Particulate matter is small enough to be inhaled and causes severe health-related problems, such as asthma and other lethal effects (Zhang et al., 2019). Particulate matter's toxicity multiplies when it is attached or absorbed to a surface. Worldwide, the relationship between PM2.5 and health is well known. These effects include contagious and chronic respiratory maladies, neurocognitive diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and pregnancy risks (Brook et al., 2004; Hart et al., 2015; Kandari and Kumar, 2021).

China, the UK, Brazil, Italy, and the USA are the most affected countries by COVID-19, and there is a strong link between the level of cases and air pollution. With this background, several studies have been conducted to find the correlation between COVID-19 and air pollution. A positive correlation exists between air quality and COVID-19 infections in Italy. However, this correlation varies from country to country (Comunian et al., 2020). It was concluded that the poor quality of air and the higher PM2.5 caused a high mortality rate. Other studies in Italy found the same relationship (Conticini et al., 2020; Fattorini and Regoli, 2020). It has been recorded that the concentration of PM2.5 and PM10 increased substantially compared to the last four years and reached a chronic level in Northern Italy, where the death rate from COVID-19 also increased. It can be concluded from this paper that air quality was correlated with COVID-19 cases and long-term exposure to such poor air quality increased the spread of the virus and hence, confirmed cases. In the USA, a cross-sectional examination by Kandari and Kumar (2021) showed that an exposure of 1 g m3 PM2.5 for longstanding contact is related to an 8% rise in the mortality rate of COVID-19 patients (Kandari and Kumar, 2021). As a result, increased exposure to PM2.5 increased COVID-19 deaths because it increased PM concentration by 11, causing mortality. Another study reported that within a few days after COVID-19 countermeasures in Salé, Morocco, PM10 concentrations were reduced by 49% (Ocak and Turalioglu, 2008). Mandal and Pal (2020) observed a decline in PM10 concentrations from 189-278 g m3 to 50-60 g m3 in Eastern India (Mandal and Pal, 2020). It is reported that there was a notable decrease of 85.1% in PM2.5 in the most polluted city (Ghaziabad) in India during the three months before restrictions were put in place (Lokhandwala and Gautam, 2020). A decline in PM2.5 and PM10 was generally much lower in urban Europe (8%) than in Wuhan (42%) in both relative change and magnitude (Mahato et al., 2020). During COVID-19 restrictions, PM2.5 concentrations were reduced by 17% across Europe. Lastly, a study by Pansini and Fornacca (2021) found that the USA, China, UK, Germany, France, Spain, Iran, and Italy air quality index showed a statistically positive and significant relationship between COVID-19 infection and the level of pollution in the air. The presence of PM indicates the quality of air and related health issues for future strategies.

5.3. Sulfur dioxide (SO2)

Sulfur dioxide is an important air pollutant linked with coal, oil, and chemical emissions, and it is the main indication for the formation of different hazardous particles in the atmosphere. These particles are continuously rising due to human activities which are abundant in urban areas (Kulmala et al., 2004). A study in Salé, Mo, reported that SO2 concentrations were reduced by 49% during three months under Covid-19 restrictions. During January, February, and March of 2020, based on data collected by Xu et al. (2020) from the three cities, Wuhan, Enshi, and Jingmen in China, the average SO2 concentration decreased by 45%, 30%, 33% compared to the same months from 2017 to 2019 (Yang et al., 2018). The US and Spain experienced a similar outcome. In Korea and Germany, SO2 concentrations were reduced by about 20 to 30% compared to the same month in 2019 (Doumbia et al., 2021).

5.4. Carbon monoxide and dioxide (CO/CO2)

Carbon monoxide is one of the significant markers of air pollutants created by incomplete combustion, such as automobile exhaust and fuel combustion. Thus, carbon emissions are divided into two categories; one is direct sources due to energy use like combustion, and the second is indirect sources due to the usage of non-energy products (Guo et al., 2018). Indirect sources play a more prominent role in carbon emissions than direct sources (Clarke et al., 2017; Geng et al., 2011). High CO concentrations represent a significant risk to human health and can rapidly cause hypoxia in humans, prompting giddiness and even death (Li et al., 2017). Based on the data collected by Xu et al. (2020) from 2017-2019 in the three cities of Wuhan, Enshi, and Jingmen, China (January, February, and March 2020), the average CO concentration was reduced by 28.8%, 20.3%, and 27.9%, respectively. Carbon dioxide occurs naturally in the atmosphere, with its primary anthropic drivers being deforestation and fossil fuel burning, such as coal and oil. Carbon dioxide harms air pollution and the greenhouse effect, trapping heat in the atmosphere. According to Le Quéré et al. (2020), global emissions of CO2 were reduced by 17% during early April 2020, the peak three months of COVID-19 as compared to April 2019 levels, which might have been caused by the reduction in transportation like vehicle and flight shutdowns (Le Quéré et al., 2020). The are many direct and indirect methods, but the Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index (LMDI) is one of the best and most popular methods to measure carbon emissions (Zhang et al., 2020). Thus, carbon emissions can be measured easily during certain times, like in a pandemic.

5.5. Ozone (O3)

Ozone (O3) is an essential helpful greenhouse gas produced from anthropogenic activities (Such as power plants, fossil fuel emissions, and industrial exhaust), which has increased the level of O3 in the atmosphere (Logan et al., 1981; Ryerson et al., 2001). High air humidity, solar radiation, expanded Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), and NOx in the environment stimulate the photochemical reaction and increase O3 levels. Based on the data collected by Xu et al. (2020) from the three cities, Wuhan, Jingmen, and Enshi, China, for three months (January, February, and March 2020), the average O3 concentration was elevated by 12.7%, 14.3%, and 11.6% compared to 2017-2019, respectively. According to Sicard et al. (2020), during the lockdown in 2020, the daily O3 level was raised by 36% in Wuhan, 27% in Turin, 14% in Rome, 24% in Nice, and 2.4% in Valencia as compared to 2017-2019 period (Sicard et al., 2020). The lockdown impact on the production of O3 was 38% higher in Wuhan and 10% higher in Southern Europe than the weekend effect.

As indicated in the previous paragraph, O3 levels are firmly linked to VOCs and NO2. When the concentration of NOx is low, NOx supports the O3 concentration, and the formation of VOCs has little impact on O3. NOx concentrations negatively correlate with O3 production when low VOC concentrations (Chameides et al., 1992). In photochemical reactions, NO2 acts as a precursor under adequate solar radiation power and is first dissociated into O3 and NO. Overall, urban O3 and NOx have negative association features, mainly in winter. This is because in summer, because of the extreme sun-based radiation and the predominant photochemical responses, the environment is increasingly suitable for the build-up of O3. The photochemical response during winter is moderately low. Therefore, under higher concentrations of NO2, a distinct range of O3 is vital to building up. During peak days of COVID-19, a lower concentration of NO2 causes more formation of O3, which cannot change into another element (Biswas et al., 2019).

5.6. Water pollution

Water plays a fundamental role in daily life and is considered essential for all life (Postel et al., 1996). Drinking water sometimes contains numerous chemical, biological, or physical impurities, which cause chronic human issues or even death. Water pollution occurs when microorganisms, poisonous synthetic compounds from industries, and local waste interact with water bodies, overflow, or filter into freshwater or groundwater assets. As reported by WHO in 2017, almost two billion people drink contaminated water worldwide. Different types of diseases spread, such as cholera, polio, dysentery, and typhoid, from contaminated water (Chen et al., 2019). The estimated death toll is about 485.000 yearly from diarrheal diseases alone, as reported by the WHO (Liu et al., 2018). Additionally, around 5.000.000 child deaths happen in developing countries due to polluted drinking water supplies (Holgate, 2000). Almost 60% of infant deaths occur due to water-related diarrhea in Pakistan alone, the most elevated proportion in Asia (Yousafzai et al., 2020). The rise of urban areas and industrialization put enormous pressure on water resources, and the release of wastewater into natural water resources decreases the quality of surface and groundwater. Thus, to understand water pollution during the peak days of the lockdown, scientists and researchers need to assess the impact of COVID-19’s short- and long-term impact on the hydrosphere, such as groundwater, oceans, rivers, and lakes.

During the COVID-19 lockdown, most industries were closed, or if open, their manufacturing demand was reduced due to a decrease in demand and the economy. Thus, lockdown may save our surface water resources like lakes and rivers, as contamination of water resources has decreased. During a lockdown, the most affected industries included plastic, crude oil, wastewater disposal, and heavy metals (Häder et al., 2020). The news media in Italy reported that the Grand Canal turned into clear water during the lockdown and aquatic life reappeared and flourished (Yunus et al., 2020). Due to the lockdown, 22 drains that disposed of sewage into the Ganga River were sealed, thereby making the Ganga River cleaner. Specialists and researchers revealed that the water of the Ganga, from Devprayag to Harki Paudi, fell beneath the 'A' category considered by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB). This suggests that water is suitable for drinking in 2020 (Mani, 2020). The biochemical oxygen level fell under 3 mg/liter, which indicates good water quality (Gautam et al., 2020). An examination by Yunus et al. (2020) reported that during the lockdown period, the Suspended Particulate Matter (SPM) concentration was reduced by 15.9% on average (range: -10.3% to 36.4%, up to 8 mg/l decreases) in the freshwater Indian Vembanad Lake compared with the pre-lockdown period (Yunus et al., 2020). Compared to previous years, the rate of SPM declined by 34% in April 2020. To stop the spread of coronavirus through the wastewater, China has developed wastewater treatment plants to reinforce its decontamination (fundamentally through expanded chlorine usage). However, there is no proof of the existence of the coronavirus in wastewater or drinking water (La Rosa et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the abundance of chlorine in the water could harm human and animal health (Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020).

5.7. Noise pollution

Environmental noise is one of the leading causes of environmental distress, health problems, and changes in the ecosystem's natural conditions (Zambrano-Monserrate and Ruano, 2019). Noise pollution is an unwanted sound due to anthropogenic activities, either commercial or industrial activities. Introduction to submerged noise pollution from transportation is known to cause a variety of harmful effects in invertebrates, including the brittle star (Amphiura filiformis), the decapod (Nephrops norvegicus), clams (Ruditapes philippinarum), fish, and marine mammals (whales). These effects include the disruption of the behavior (Weilgart, 2018; Wisniewska et al., 2018), augmented level of physiological stress (Debusschere et al., 2016; Rolland et al., 2012), and masking of acoustic communication (Putland et al., 2018; Stanley et al., 2017). High noise levels can also cause cardiovascular impacts in people and elevated rates of Coronary Heart Disease (Brunekreef, 2006; Münzel et al., 2018). Due to restrictions, transportation from small to large vehicles was reduced significantly. Meanwhile, the activities at the commercial level were entirely stopped. Most of the road networks were found to be predominantly empty, therefore was no noise of vehicle engines, no honking, no commercial and sporting events, no loud echo of speakers, and no noise from factories (Espejo et al., 2020). Globally, shipping, imports, and exports were significantly reduced. Due to COVID-19, the load of isolating restrictions by many governments made individuals stay at home. Therefore, shipping and public and private transport were reduced significantly. Almost wholly, business activities were also halted (Wang et al., 2020).

6. Human health affected by COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic severely threatens human health worldwide by causing anxiety, mental stress, depression, and many other negative behaviors (Shigemura et al., 2020). Globally, all countries were affected by it; however, there is minimal information and data on human health except for COVID-19-infected cases. Mental health is one of the major issues that was more pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Human mental performance is strongly influenced due to serious human tragedies and natural disasters (Ćosić et al., 2020). Besides the pandemic, health issues cause enormous economic loss. It has been reported that16.4 trillion dollars will be spent globally on mental health care from 2010 to 2030 (Mari and Oquendo, 2020). It is also reported that many human stresses are highly associated with large-scale disasters like pandemics. The pandemic of COVID-19 has significantly impacted human health and created several health and mental complications, such as uncertainty in body performance and enormous unemployment (Inkster, 2021; Reeves et al., 2014). According to a report, when asked by the health minister of Afghanistan about the emotional condition during the Afghan war in 2001, he said that about 60% of people suffered mental and health issues (Ćosić et al., 2012). The FAO stated that almost 37 million people in Europe generally suffer from anxiety and 44 million from depression (Dubey, 2020). Almost every person is unexpectedly disturbed with negative emotions, emotional traumas, and other kinds of mental and health disordered due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Confirmed COVID-19 cases suggest that almost 200 countries will face severe health challenges (STATISTA). Among the challenges, unemployment and health were in most of the report. According to a report, almost 3.0 million people claimed unemployment in the USA only during March 2020. The published report estimated that GDP declined in developing and developed industrial countries and benchmarked for a world with rates of 2.5%, 1.8%, and 4%, respectively, due to the COVID-19 outbreak (Maliszewska et al., 2020). Besides spreading the virus, treatments and the development of vaccines were addressed widely; however, there is a need for awareness of the long term effect on health and mental issues in global communities.

Due to economic uncertainty and public health, it is well known that mental health is seriously affected due to the threat of COVID-19. A report by the WHO addressed that anxiety and stress are highly associated with this pandemic (WHO, 2020). Reports have also stated that the rate of other activities such as level of loneliness, abuse of alcohol and drugs and depression have increased in the affected individual. Similarly, many other concerns like fear, negative social behavior, health consciousness, and medical checkups increased significantly (Shigemura et al., 2020). It is reported that almost 32% of adults in China worried and were stressed continuously about COVID-19, and almost 14% were severely affected by mental health issues during March 2020 (Hamel et al., 2020). Therefore, taking action and creating awareness among societies is indispensable to reducing the mental damage due to fear of the COVID-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, there is a need to find a way in national and international policies to address the health concern due to pandemics and other disasters. Omicron, Delta, and Gamma variants have been associated with the same symptoms developed by patients in the early COVID-19 variant. However, Omicron is less severe than any other strain as it does not cause severe pneumonia and alveoli destruction. Meanwhile, very few people are associated with losing taste or smell (Monajjemi et al., 2022).

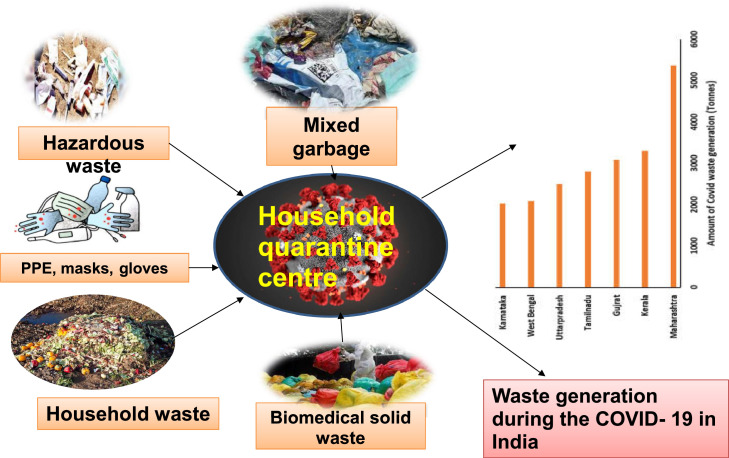

6.1. Medical waste due to COVID-19

This review identifies the relationship between solid wastes generated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, these investigations could be used to evaluate the quantity and variation in waste production during the COVID-19 pandemic. This work can also provide the basis of more research on the sustainable management of waste during pandemics. The pandemic of COVID-19 has created a number of environmental challenges such as biomedical waste and municipal waste. The North American Association for Solid Waste described how COVID-19 lockdown has increased the sources and volume of waste to reduce disease exposure. Similarly, in Hubei, China, according to a press release on March 11, 2020, municipal waste was reduced by almost 30% and medical waste increased by 370% during the peak days of COVID-19 (Kleme et al., 2020). It has been stated that generated medical waste accounts for more than 80% of infectious waste disposed of by municipalities (WHO, 2020).

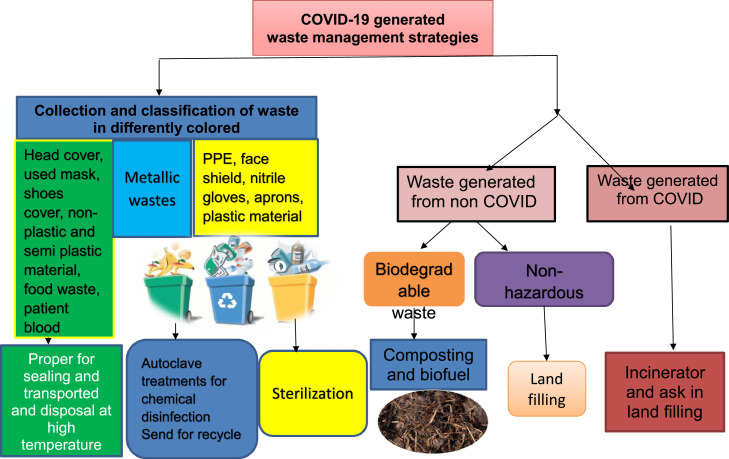

Among the number of unexpected impacts of COVID-19, management of municipal waste has become a potential concern due to its increasing mass (Smart Waste report, European Union, 2020). To protect themselves from COVID-19 infection, individuals are competing to purchase face masks, particularly medical masks (Secon, 2020). It has prompted a clinical mask scarcity for individuals in need and may bring about a scarcity of clinical masks around the globe (Miller, 2020). As reported in previous studies (Johnson and Morawska, 2009), the mouth is the key source of a respiratory virus that spreads into the air by coughing and speech. Additionally, it has described that common cloth (70% cotton and 30% polyester) and towel (100% cotton) masks exhibited 40–60% filtration efficacy for particles (Rengasamy et al., 2010). For the safe disposal of face masks and other clinical waste, individuals need guidelines and protection for safe disposal (Phan and Ching, 2020). The workers responsible for collecting trash often dump the material in the open environment, which creates danger and an unfavorable environment. Employees or individuals who are responsible for the cleanliness of urban communities need to perform their duties regularly, which reduces the spread of the virus by waste. Masks are manufactured with liquid resistant plastic building materials and are long-lived. Consequently, they are castoffs and end up in landfills or the ocean. Aside from clinical masks, hand sanitizer, gloves, and tissue paper have been increasingly used and build up clinical waste in nature. It was reported that a 100 m stretch of beach in the Soko islands, Hong Kong has a massive buildup of masks, as reported by Ocean Asia. Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, 7 million individuals unexpectedly began wearing single-use gloves, one or several masks every day, hand sanitizers, and thus, and the quantity of trash delivered was significant. During the outbreak, an average of 240 metric tons of medical waste was produced by hospitals in Wuhan per day when compared with their past average of fewer than 50 metric tons. There has also been an upsurge in trash from personal protective equipment (PPE) such as gloves and masks in other countries such as the USA (Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020). Waste generation during the COVID-19 global pandemic has seen a sharp increase due to huge safety measures and daily consumption (Fig. 3 ). It has reported that plastic use in COVID has increased (Nghiem et al., 2020). The management of clinical waste could be a major problem as coronavirus is rapidly spreading around the world. Waste management companies and medical health organizations have developed different strategies for the purification of coronavirus from waste streams. Recycling of waste has consistently been a key environmental issue and is important for countries (Liu et al., 2020). Recycling is a common and compelling approach to stopping pollution, conserving natural resources and saving energy (Ma et al., 2019). As specialists have been worried about the danger of spreading COVID-19 in recycling hubs, countries like the USA have quit recycling programs in a portion of their urban areas. Management of waste has been restricted in mainly developed countries. Furthermore, the industry has reduced the production of dispensable bags, and on the other hand, single-use plastics can even hold bacteria and viruses (Bir, 2020). A possible waste management strategy for citizens to overcome these issues with environmental concerns depicted in Fig. 4 . Thus, waste management, either municipal or clinical, is a very important part of health services and it needs to be highly considered even before the pandemic. Management of this waste reduces the risk associated with waste handling and transmission among people.

Fig. 3.

Potential waste generation during the COVID- 19 global pandemic.

Fig. 4.

Waste management strategies for a green and clean environment to be adopted by populations in developing country.

6.2. Agricultural and food systems

Food is a basic necessity of health and countries try to ensure the security of food during a time of difficulty (Raheel et al., 2021) as is the case in the pandemic (Mwalupaso et al., 2019; Skaf et al., 2019). Similarly, water security is also a critical issue during times of difficulties and its security is necessary to satisfy the standard of a healthy life (Cai et al., 2020). Influence on food security and disruption to food systems is of immediate concern. Globally, food supply and revenue collection have been disturbed profoundly. There was extensive mass media attention given to the unexpected decrease in food security because of market disruptions, closures or lessened institution capacity ultimately vegetables, milk and fruits wastage, etc. (Torero, 2020). A number of restrictions have firmly been recommended from the 1st day of the pandemic. Most countries banned the travelling, import and export of goods at international and national levels to control the spread of the virus, which abruptly disturbed the socio-economic status of many countries. Meanwhile, it also influenced the agro-food system all over the world. The indirect impact of COVID-19 is well known on the daily life system. The demands for food and its services at commercial and restaurant levels decreased many times due to restrictions in the food processing system, unavailability of labour and storage problems at the farm and industry levels. Quarantine strictly affected the availability of labour for agriculture like sowing or maturity/ harvesting stages of fruits, grains and vegetables. During the peak days of COVID-19, the impact of food issues become more prominent and expanded from agricultural production (Torero, 2020). There are a number of reasons behind the food insecurity during the pandemic and the most notable were the loss of jobs and workers’ income, which reduced the ability to purchase food supplies. Similarly, quarantine bounded to stay at home reduces selling and buying capacities of food items. It has also reduced the gathering activities of people to go out for fast food and hence, the food market is affected. The market of food was severely affected as the central distribution system of many supermarkets was hindered due to an imbalance in supply and demand for food items. The stock of milk, perishable fruit and vegetable was wasted due to transportation issues from the place of production to the local market.

The second most important factor that impacted the agro-food system was the availability of labour (Jiang et al., 2017). Because of isolation measures and workforce loss from COVID-19 deaths and severe illness, labour has been unexpectedly limited in many regions. In global work movements and worker programs, there have been substantial limitations that are dangerous to the production of agriculture in some zones or that have caused bottlenecks. The COVID-19 outbreak is influencing global relations a long way past the agri-food division's work power. All the agricultural practices either livestock/agricultural production or planting/harvesting are laborious. The availability of labour has affected all these services and therefore, the food and agricultural system of most countries has been disrupted. Similarly, the border closure banned the import and export of agricultural commodities across the world, which is another factor that reinforces the impact of COVID-19 on the agro-food system. Thirdly, the resilience of the food system considers the important domain that impacted it during the time of the crisis. Most importantly, connectivity among the agro-food system was disturbed and ultimately the global agro-food market and trade were affected intensively (Laborde, 2020). As the global trade (Import and export) depended on the connectivity of borders, due to the shutdown of ports and commercial flights, the activity of agricultural and food goods was disrupted (Ivanov, 2020; Laborde, 2020). It incorporates the declarations of export constraints across numerous countries that restrict worldwide agri-food exchange and access to the market (Laborde, 2020). Internationally, the agri-food zone is vastly linked. Ports that reduce or shut down movements, for agricultural goods massively decreased freight volume on business flights and other wide international supply chain distractions because of the COVID-19 emergency (Ivanov, 2020) can restrict basic access to agrarian efforts and markets. These undermined the impact of COVID-19 dramatically influencing the global food chain system for an unknown period. This may harmfully influence agrarian output for present and upcoming periods.

6.3. Forest sector

Forest protection is an important strategy for mitigation of climate change (Foley et al., 2011) and is always acknowledged because it sequesters a significant amount of carbon (Elisa et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2011). Furthermore, forests are biologically important and eco-friendly for nature and offer many significant services to maintain the ecosystem (Syed et al., 2022). Like other industries, COVID-19 has destroyed the woodland-related industry as a sharp drop in imports and exports of wood products occurred all over the globe. Worldwide interest in wood and wood items, including wood furniture, tropical timber and graphic paper has collapsed. Meanwhile, woodland-connected industries have not been capable to carry on working at full capacity. On the opposite side, there have been steady or even expanded requests for other woodland-based items, including wooden pallets, wrapping materials and tissue for masks and lavatory paper. At the start of the outbreak, requests for toilet paper increased many folds around the world and in some European countries, it increased by nearly 200% per week. The predictable development of the e-commerce industry is probably getting attention for wrapping materials. Despite the capability of the sector to endorse employment and development, the tenacious work shortages have deteriorated by the outbreak. Worldwide, numerous occupations have been forgotten and a lot more are still in danger, as enterprises have confronted difficulties in holding their labour force around the world and meeting financial obligations, leaving people jobless or furloughed. Steady advancement has been made to date to uplift women by supporting their contribution to legitimate and sustainable fuelwood and charcoal production. However, the COVID-19 outbreak is assessed to get expanding trouble on forest assets through unlawful production of charcoal where living dependent on lawful exercises is forfeited in favour of rapid economic gains (Organisation, 2020). The irresistible increase in the population of humans leads to deforestation for industrial means and land for grazing or agriculture (Afelt et al., 2018). Afforestation is an important element of sustainability and its changes during the days of social transformation like a pandemic. Evidence reported that during COVID-19, the illegal clearing of forests and threats to the ecosystem have increased. Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) has reported that almost 9,583 km2 of deforestation around the tropical during peak months of lockdown to control the spread of the virus (COVID-19), which was double that of 2019 (Brancalion et al., 2020). Deforestation is also associated with various types of fowls and diseases such as Zoonotic a bat-borne viral outbursts (Olivero et al., 2017; Smith and Olesen, 2010).

Lastly, it has reported that in deforestation regions, outbreaks of viral diseases spread at a higher rate (Shah et al., 2019). It is stated that COVID-19 proposed many negative impacts on food security, increased deforestation and many other zoonotic diseases. In the pandemic scenario, it will be very challenging for governments to save lives and forests in tropical areas and support communities serving on a cash economy (Ferrante and Fearnside, 2020) and such a situation gives birth to a new pandemic (Everard et al., 2020).

6.4. Biodiversity

The pandemic resulted in many extreme challenges that threaten biodiversity. The richness of a different animal and plant species in a habitat are referred to as biodiversity (Verma and Prakash, 2020). Nature always develops and promotes balance among the entire living organism by providing a natural environment. All unexpected environmental threats are associated with humans in some way. COVID-19 is also considered as a result of an imbalance in biodiversity such as bat populations. It is noted this time that there is a relationship exists between pandemic (Verma and Prakash, 2020) and biodiversity. It is observed that a number of diseases are associated with animals and birds. With regards to COVID-19, bats and rats got major attention. Due to fear of COVID-19, humans disturbed the natural environment of biodiversity. It is cited that for healthy growth of humans and the economy, a healthy environment is a critically important (Chakraborty and Maity, 2020).

Due to the pandemic, the number of anthropogenic activities were reduced. When human activity decreases due to quarantine, the surrounding biodiversity increases and the surrounding environment emerges as green and clean (Verma and Prakash, 2020). It was also recorded that the water quality improved and aquatic organisms, especially the fish population, flourished during the days of lockdown (Cooke et al., 2021; Verma and Prakash, 2020). COVID-19 outbreak can cause serious consequences on biodiversity and protection upshots. This virus arose because of wildlife misuse (Zhou et al., 2020) and with environmental degradation, the hazard of new diseases rises (Keesing et al., 2010). Previous events for instance pandemics, financial crises and wars have also activated measurable environmental changes (Pongratz et al., 2011; Sayer et al., 2012). There may be problems but on a recent indication, practical conservation seems to be ongoing in several spots. There have even been episodic information on diminished human stresses on wild species. Drops in visitor numbers triggered by travel limitations and park closures have decreased pressures on sensitive animals and crushing weight on popular trails in protected areas. In protected areas, conservation develops a lot of its community support from the wild nature availability but for sensitive species, decreased human weight in the most well-known parks will be acceptable. We have likewise observed reports of wild species wandering into urban and rural regions, including beaches and parks, where they have not been seen for a long time, as traffic and other human movement decays. In zones where protected areas remain open and travel is still possible, vegetation has often significantly expanded reflecting extensive feeling that movement in a natural location is both a mental and physical remedy to the pressure of the outbreak (Corlett et al., 2020).

In coastal areas, beaches are one of the most significant natural resources (Zambrano-Monserrate and Ruano, 2019). They offer services (sand, land, tourism and recreation) that are important to the coastal communities’ survival and hold essential qualities that must be secure from overutilization (Lucrezi et al., 2016). However, individuals have made numerous beaches contamination problems in the world by non-responsible use (Partelow et al., 2015). Social distancing actions because of the COVID-19 disease results in the tourist's lack that has instigated a prominent alteration in the look of many beaches of the world. Such seashores like those of Salinas (Ecuador), Acapulco (Mexico) or Barcelona (Spain), currently look cleaner and with precious stone clear waters.

6.5. Soil health

This article demonstrates the importance of soil restoration and management to mitigate COVID-19 adverse impacts through improving soil health and improving the production system. Removing the communication gap among policymakers, soil scientists, and people through distance learning may be helpful for the restoration of COVID-19 impacts.

The pandemic of COVID-19 has globally disturbed the food system and increased food insecurity. The lockdown has significantly increased the price of commodities like wheat and rice, which increased by 8 and 25% during March 2019, respectively (Torero, 2020). The pandemic influenced fruit, vegetables, crops, legumes and oil commodities (Lal et al., 2020). Perishable food items were significantly affected due to a shortage of labour. Food security is drastically affected due to the challenges of transportation and the irregular supply of food items to be stored (Deaton and Deaton, 2020). Keeping in view the global agriculture importance, soil plays a very important role in crop production, and serves as a key condition for crop production and resilience during times of crisis. Soil management played a very important role in achieving yield and soil health sustainability during the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the peak of the pandemic, the demand for food reduced and production increased. This imbalance created a surplus, which led to the disposal and wastage of food due to the reduction in demand. It is also recorded that in the USA during March-May 2020, meat consumption declined and the bulk of meat products expired. Ultimately, the market decided to dump the waste into the soil and disturbed the soil health (Lal et al., 2020). Similarly, a reduction in the use of perishable foods like tomatoes and potatoes created waste in an open environment (Lal et al., 2020). During the peak of COVID-19, the amount of milk that was bought dropped significantly, and millions of tons of milk were thrown away daily. Different types of waste produce pollution and toxicity for the soil and disturb soil physiochemical and biological properties and therefore, soil health is significantly affected (FAO, 2015). Similarly, the leaching of heavy metals (Raza et al., 2021) and toxic substances from the disposal of medical waste, detergents, and chemicals used during COVID-19 has increased the toxic impact on soil health.

The functionality and restoration of soil quality could be accelerated by the application of modern techniques that improve the local system of food production and improve the quality of the ecosystem to recover the pandemic (Moran et al., 2020). Soil can be used for the disposal of waste but safe disposal should be kept in mind to maintain soil health. Viruses may be transfer of different processes occurring in soil and therefore, there is a need to understand microorganism movement through the different processes such as pedogenic processes occurring in the soil. The understanding of human and COVID-19 interconnectivity is very important to comprehend but the functionality and health of soil cannot minimized (Heffron et al., 2021).

7. Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic is spreading rapidly and consistently across the globe and there is an immediate misfortune to the worldwide economy. Climate change is one of the most significant and crucial difficulties of the 21st century. Despite many endeavors to re-establish nature during the most recent decades, humans could just push a couple of strides ahead. COVID-19 created both positive and negative backhanded impacts on the environment. The current study shows that population movements may cause the spread of the virus (COVID-19) nationally and internationally. Evaluation of the literature showed that a particular matter (PM) also plays a role in the viral spread. Globally, roads are the primary means of transportation and movement, and in many countries, unsafe roads lead to several injuries and deaths. It has been discovered that the amount and frequency of road traffic varied from country to country during the lockdown. In many countries, the traffic level has reached zero, while road traffic has not changed in others. However, compared with 2018, road accidents, deaths and injuries decreased by half during the lockdown. Similarly, handling municipal and medical waste during the pandemic is very important to assess. There is a need to evaluate management services and personal safety during the lockdown because poor sanitation also responds to COVID-19. There is an utmost need for urgent environmental investigations because the surveillance of the COVID-19 virus is high in wastewater. Thus, there is a need for the treatment of wastewater to reduce the abundance of the virus in water.

On the other hand, there is evidence that the spread of the virus has been reducing air (NOx, PMX and SOX), water and noise pollution and most likely is even saving lives due to a cleaner environment. However, the O3 concentration in the atmosphere has been increasing due to low NOx. The chlorine excess in the water could damage individuals' health. Climate characteristics assumed a vital role in the infection during the initial phase, the temperate regions being more susceptible than the dry or tropical areas. Covid-19′s influence on disrupting the food systems and security is also of immediate concern. The pandemic has the potential to activate significant impacts on biodiversity and preservation. National governments and intergovernmental organizations should implement clear policies to protect biodiversity. Medical waste has not been addressed by pollution control under environmental pollution control authorities. This is an excellent hazard for human beings and the environment, and there is a need to take simultaneous action to mitigate the environment. Medium and longer-term planning require for how the economy is re-stabilized and re-empowered after this emergency. Thus, there is a need for immediate action to evaluate the social activities, environmental impacts and economic status during public health tragedies.

Ethical approval

All the authors have agreed to submit it.

Consent to participate

Before the submission of the paper all the authors have given consent to publish.

Consent to publish

All the authors have given consent to publish.

Availability of data and materials

The information is a compilation from different databases.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Taqi Raza: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. Muhammad Shehzad: Methodology, Validation. Mazahir Abbas: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Neal S. Eash: Writing – review & editing. Hanuman Singh Jatav: Data curation, Writing – original draft. Mika Sillanpaa: Writing – review & editing. Trevan Flynn: Data curation, Writing – original draft.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Reference

- Afelt A., Frutos R., Devaux C. Bats, coronaviruses, and deforestation: toward the emergence of novel infectious diseases? Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:702. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimoto H. Global air quality and pollution. Science. 2003;302:1716–1719. doi: 10.1126/science.1092666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremer S., Schneider P., Glavovic B. Climate change and amplified representations of natural hazards in institutional cultures. Oxford Res. Encycl. Nat. Hazard Sci. 2019 doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199389407.013.354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fidan O., Mujwar S., Kciuk M. Discovery of adapalene and dihydrotachysterol as antiviral agents for the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 through computational drug repurposing. Mol. Divers. 2022:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11030-022-10440-6. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11030-022-10440-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar A., Chepeliev M., Corong E., McDougall R., van der Mensbrugghe D. The GTAP data base: version 10. J. Glob. Econ. Anal. 2019;4(1):1–27. doi: 10.21642/JGEA.040101AF. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S.A., Baloch M., Ahmed N., Ali A.A., Iqbal A. The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—an emerging global health threat. J. Infect. Public Health. 2020;13(4):644–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arden C., Iii P., Burnett T., Thurston D., Michael S., Thun J., Calle E.E., Krewski P.D., Godleski J. Cardiovascular mortality and long-term exposure to particulate air pollution epidemiological evidence of general pathophysiological pathways of disease. Circulation. 2004;109(1):71–77. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000108927.80044.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat T., Muylkens B., Su B.-L. Is particulate matter of air pollution a vector of COVID-19 pandemic? Matter. 2020;3(4):977–980. doi: 10.1016/j.matt.2020.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barro R.J. Convergence and modernisation. Econ. J. 2015;125(585):911–942. doi: 10.1111/ecoj.12247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bentolila S., Jansen M., Jiménez G. When credit dries up: job losses in the great recession. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2018;16(3):650–695. doi: 10.1093/jeea/jvx021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bezemer D.J. The credit crisis and recession as a paradigm test. J. Econ. Issues. 2011;45(1):1–18. doi: 10.2753/JEI0021-3624450101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bir, B. 2020. Single-use items not safest option amid COVID-19. Coronavirus leads to rise in all sorts of plastic bags as well as including single-use items, says environmentalists. Retrieved from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/health/single-use-items-not-safest-option-amid-COVID-19/1787067 (Accessed date, 26.).

- Biswas M.S., Ghude S.D., Gurnale D., Prabhakaran T., Mahajan A.S. Simultaneous observations of nitrogen dioxide, formaldehyde and ozone in the indo-gangetic plain. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2019;19(8):1749–1764. doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2018.12.0484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhosale J. Vol. 19. The Economic Times; 2020. (Prices of Agricultural Commodities Drop 20% Post COVID-19 Outbreak). [Google Scholar]

- Brancalion P.H., Broadbent E.N., de-Miguel S., Cardil A., Rosa M.R., Almeida C.T., Almeida D.R., Chakravarty S., Zhou M., Gamarra J.G. Emerging threats linking tropical deforestation and the COVID-19 pandemic. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 2020;18(4):243–246. doi: 10.1016/j.pecon.2020.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook R.D., Franklin B., Cascio W., Hong Y., Howard G., Lipsett M., Luepker R., Mittleman M., Samet J., Smith S.C., Jr Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the expert panel on population and prevention science of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004;109(21):2655–2671. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128587.30041.C8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunekreef B. Traffic and the heart. Eur. Heart J. 2006;27(22):2621–2622. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J., He Y., Xie R., Liu Y. A footprint-based water security assessment: an analysis of Hunan province in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;245 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cereda, D., Tirani, M., Rovida, F., Demicheli, V., Ajelli, M., Poletti, P., Merler, S., 2020. The early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.09320. 10.48550/arXiv.2003.09320.

- Chakraborty I., Maity P. COVID-19 outbreak: migration, effects on society, global environment and prevention. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chameides W., Fehsenfeld F., Rodgers M., Cardelino C., Martinez J., Parrish D., Lonneman W., Lawson D., Rasmussen R.A., Zimmerman P., Greenberg J., Mlddleton P., Wang T. Ozone precursor relationships in the ambient atmosphere. J. Geophys. Res. 1992;97:6037. doi: 10.1029/91JD03014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Wang M., Duan M., Ma X., Hong J., Xie F., Zhang R., Li X. In search of key: protecting human health and the ecosystem from water pollution in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;228:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chepeliev M. Center for Global Trade Analysis, Department of Agricultural Economics, Purdue University; 2020. Development of the Non-CO2 GHG Emissions Database for the GTAP Data Base Version 10A (No. 5993) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke J., Heinonen J., Ottelin J. Emissions in a decarbonised economy? Global lessons from a carbon footprint analysis of Iceland. J. Clean. Prod. 2017;166:1175–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A.J., Brauer M., Burnett R., Anderson H.R., Frostad J., Estep K., Balakrishnan K., Brunekreef B., Dandona L., Dandona R. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet N. Am. Ed. 2017;389(10082):1907–1918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30505-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collivignarelli M.C., Abbà A., Bertanza G., Pedrazzani R., Ricciardi P., Miino M.C. Lockdown for CoViD-2019 in Milan: what are the effects on air quality? Sci. Total Environ. 2020;732 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comunian S., Dongo D., Milani C., Palestini P. Air pollution and COVID-19: the role of particulate matter in the spread and increase of COVID-19′s morbidity and mortality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(12):4487. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conticini E., Frediani B., Caro D. Can atmospheric pollution be considered a co-factor in extremely high level of SARS-CoV-2 lethality in Northern Italy? Environ. Pollut. 2020;261 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke S.J., Twardek W.M., Lynch A.J., Cowx I.G., Olden J.D., Funge-Smith S., Lorenzen K., Arlinghaus R., Chen Y., Weyl O.L. A global perspective on the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on freshwater fish biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 2021;253 doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corlett R.T., Primack R.B., Devictor V., Maas B., Goswami V.R., Bates A.E., Koh L.P., Regan T.J., Loyola R., Pakeman R.J. Impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on biodiversity conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2020;246 doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ćosić K., Popović S., Šarlija M., Kesedžić I. Impact of human disasters and COVID-19 pandemic on mental health: potential of digital psychiatry. Psychiatr. Danub. 2020;32(1):25–31. doi: 10.24869/psyd.2020.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ćosić K., Srbljinović A., Popović S., Wiederhold B.K., Wiederhold M.D. Emotionally based strategic communications and societal stress-related disorders. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012;15(11):597–603. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaton B.J., Deaton B.J. Food security and Canada's agricultural system challenged by COVID-19. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2020;68(2):143–149. doi: 10.1111/cjag.12227. /Revue canadienne d'agroeconomie. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Debiec-Andrzejewska K., Krucon T., Piatkowska K., Drewniak L. Enhancing the plants growth and arsenic uptake from soil using arsenite-oxidizing bacteria. Environ. Pollut. 2020;264 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debusschere E., Hostens K., Adriaens D., Ampe B., Botteldooren D., De Boeck G., De Muynck A., Sinha A.K., Vandendriessche S., Van Hoorebeke L. Acoustic stress responses in juvenile sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax induced by offshore pile driving. Environ. Pollut. 2016;208:747–757. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumbia T., Granier C., Elguindi N., Bouarar I., Darras S., Brasseur G., Gaubert B., Liu Y., Shi X., Stavrakou T. Changes in global air pollutant emissions during the COVID-19 pandemic: a dataset for atmospheric chemistry modeling. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2021:1–26. doi: 10.5194/essd-13-4191-2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drosten C., Günther S., Preiser W., Van Der Werf S., Brodt H.-R., Becker S., Rabenau H., Panning M., Kolesnikova L., Fouchier R.A. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348(20):1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey, A.K., 2020. Impact of Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on personal relationship of human being.

- El-Erian M. The coming coronavirus recession and the uncharted territory beyond. Foreign Aff. 2020 doi: 10.5194/essd-2020-348. Accessed 27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elisa P., Alessandro P., Andrea A., Silvia B., Mathis P., Dominik P., Manuela R., Francesca T., Voglar G.E., Tine G. Environmental and climate change impacts of eighteen biomass-based plants in the alpine region: a comparative analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;242 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espejo W., Celis J.E., Chiang G., Bahamonde P. Environment and COVID-19: pollutants, impacts, dissemination, management and recommendations for facing future epidemic threats. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;747 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everard M., Johnston P., Santillo D., Staddon C. The role of ecosystems in mitigation and management of COVID-19 and other zoonoses. Environ. Sci. Policy. 2020;111:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2020.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO I. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and Intergovernmental Technical Panel on Soils; Rome, Italy: 2015. Status of the World's Soil Resources (SWSR)–technical summary. [Google Scholar]

- Fattorini D., Regoli F. Role of the chronic air pollution levels in the COVID-19 outbreak risk in Italy. Environ. Pollut. 2020;264 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante L., Fearnside P.M. Protect Indigenous peoples from COVID-19. Science. 2020;368(6488):251. doi: 10.1126/science.abc0073. 251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FITBIT, B., 2020. FITBIT news: the impact of coronavirus on global activity [Internet].

- Foley J., Ramankutty N., Brauman K., Cassidy E., Gerber J., Johnston M., Zaks D. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature. 2011;478:7369. doi: 10.1038/nature10452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam M., Kumari S., Gautam S., Singh R.K., Kureel R. The novel coronavirus disease-COVID-19: pandemic and its impact on environment. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020;39(17):13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam S. COVID-19: air pollution remains low as people stay at home. Air Qual. Atmos. Health. 2020;13:853–857. doi: 10.1007/s11869-020-00842-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Y., Tian M., Zhu Q., Zhang J., Peng C. Quantification of provincial-level carbon emissions from energy consumption in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011;15(8):3658–3668. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling S., Scott D., Hall C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020;29(1):1–20. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green M.S. Did the hesitancy in declaring COVID-19 a pandemic reflect a need to redefine the term? Lancet N. Am. Ed. 2020;395(10229):1034–1035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30630-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J., Zhang Y.J., Zhang K.B. The key sectors for energy conservation and carbon emissions reduction in China: evidence from the input-output method. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;179:180–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.01.080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Häder D.-P., Banaszak A.T., Villafañe V.E., Narvarte M.A., González R.A., Helbling E.W. Anthropogenic pollution of aquatic ecosystems: emerging problems with global implications. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;713 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30630-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel L., Lopes L., Muñana C., Kates J., Michaud J., Brodie M. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2020. KFF Coronavirus Poll: March 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monajjemi, M., Kandemirli, F., Mollaamin, F., & Küçük, Ö., 2022. An overview on nature function in relation with spread of Omicron-COVID-19: where will the next pandemic begin and why the amazon forest offers troubling clues. 10.33263/BRIAC133.225.

- Hart J.E., Liao X., Hong B., Puett R.C., Yanosky J.D., Suh H., Kioumourtzoglou M.-A., Spiegelman D., Laden F. The association of long-term exposure to PM 2.5 on all-cause mortality in the nurses’ health study and the impact of measurement-error correction. Environ. Health. 2015;14(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12940-015-0027-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]