Abstract

The toxicity induced by the persistent organic pollutants per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) is dependent on the length of their polyfluorinated tail. Long-chain PFASs have significantly longer half-lives and profound toxic effects compared to their short-chain counterparts. Recently, production of a short-chain PFAS substitute called ammonium 2,3,3,3-tetrafluoro-2-(heptafluoropropoxy) propanoate, also known as GenX, has significantly increased. However, the adverse health effects of GenX are not completely known. In this study, we investigated the dose-dependent effects of GenX on primary human hepatocytes (PHH). Freshly isolated PHH were treated with either 0.1, 10, or 100 μM of GenX for 48 and 96 hours; then, global transcriptomic changes were determined using Human Clariom™ D arrays. GenX-induced transcriptional changes were similar at 0.1 and 10 μM doses but were significantly different at the 100 μM dose. Genes involved in lipid, monocarboxylic acid, and ketone metabolism were significantly altered following exposure of PHH at all doses. However, at the 100 μM dose, GenX caused changes in genes involved in cell proliferation, inflammation and fibrosis. A correlation analysis of concentration and differential gene expression revealed that 576 genes positively (R > 0.99) and 375 genes negatively (R < −0.99) correlated with GenX concentration. The upstream regulator analysis indicated HIF1α was inhibited at the lower doses but were activated at the higher dose. Additionally, VEGF, PPARα, STAT3, and SMAD4 signaling was induced at the 100 μM dose. These data indicate that at lower doses GenX can interfere with metabolic pathways and at higher doses can induce fibroinflammatory changes in human hepatocytes.

Keywords: PFAS, GenX, Toxicogenomics, Primary Human Hepatocytes, Inflammation, Proliferation

1. Introduction

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are persistent organic pollutants with a myriad of adverse health effects, including immune, developmental, and liver toxicity (Bassler et al. 2019; Das et al. 2015; Gaballah et al. 2020; Peden-Adams et al. 2008). PFAS are anthropogenic chemicals with a prolonged half-life in humans on the magnitude of years (Stein et al. 2016; Suja et al. 2009) and exhibit significant bioaccumulation. These compounds are structurally similar to fatty acids, which both consist of a charged functional group coupled to a carbon backbone. However, fatty acids have a hydrocarbon backbone, while PFAS contains an aliphatic fluorocarbon. Due to this fluorination, PFAS are extremely stable, making them useful in a variety of products that range from food packaging, waterproof fabrics, firefighting foams, and nonstick pans (Lindstrom et al. 2011).

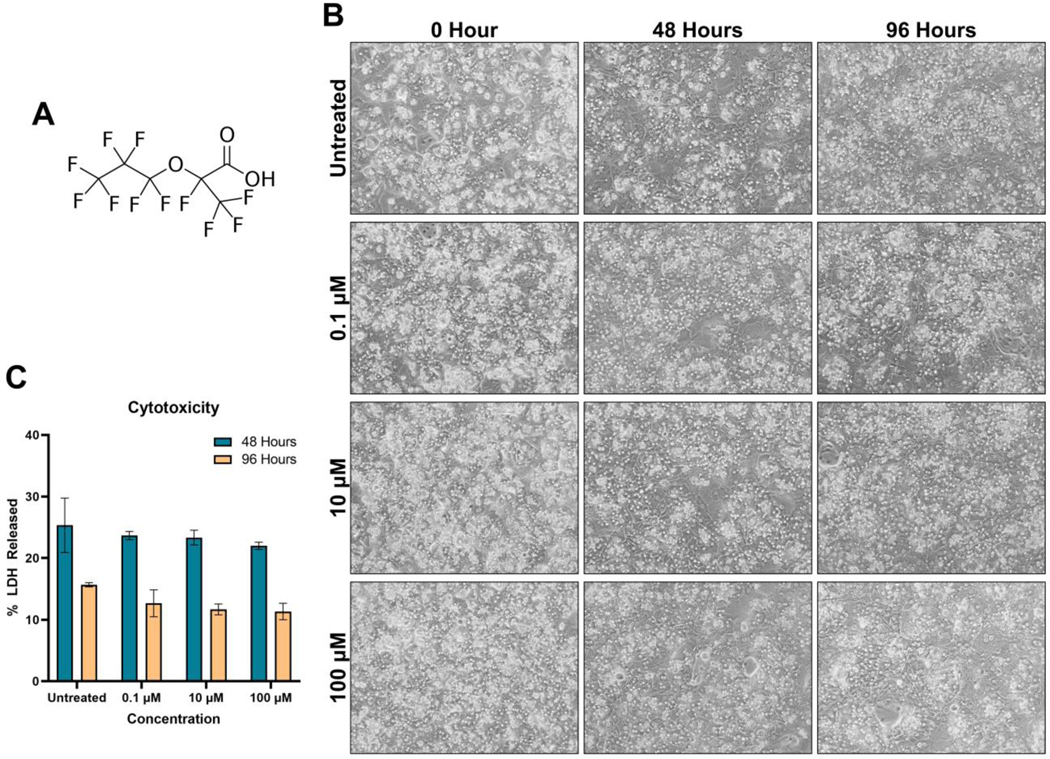

Studies show that the length of the fluorocarbon backbone of these compounds correlates with their half-lives and toxicity (Agency 2006; Jensen and Warming 2015). PFAS with a carboxylic acid functional group with a number of carbons ≥ 7 are considered long-chain while compounds with < 7 carbons are considered short-chain (Brendel et al. 2018). In general, long-chain PFAS have a significantly longer half-life in humans than in rodents (Li et al. 2018; Olsen et al. 2007; Wong et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2013). Serum concentrations are inclined to be higher in older human subjects than in younger individuals. In humans, PFAS have a shorter half-life in young females (0.5 to 10 years) compared to males and older females (1.2 to 90 years) (Zhang et al. 2013). In addition, studies show there is significantly higher elimination through renal and menstrual clearance in young females, which may help explain the shorter half-life of PFAS in this population (Fu et al. 2016; Harada et al. 2005). The short-chain PFAS have less bioaccumulation and are presumed to be less toxic (Buck et al. 2011; Conder et al. 2008). This has given rise to the increased production of short-chain replacements, such as ammonium 2,3,3,3-tetrafluoro-2-(heptafluoropropoxy) propanoate (GenX; CAS number: 62037–80-3) (Fig. 1A) (Blake et al. 2020; Brendel et al. 2018; Kancharla et al. 2022). GenX was originally developed to aid in the manufacture of fluoropolymers because of its water-solubility at pH>2.84 and is now used as an oil-repellent coating. It has also become the replacement for the long-chain PFAS perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) (Heidari et al. 2021; Paul Douglas Brothers et al. 2009). Due to the ether residing in the backbone of GenX and its proximity to the carboxylic acid, GenX adsorption is significantly less than PFOA, and the ether does not contribute to water solubility due to steric hindrance from H2O interactions (Wang et al. 2019).

Figure 1. No cell death or morphological changes after GenX treatment.

(A) Chemical structure of GenX. (B) Phase-contrast images of PHH treated with either 0.1, 10, or 100 μM for 48 or 96 hours at 100x magnification. (C) LDH cytotoxicity assay for both 48 and 96 hours after GenX treatment indicating at these concentrations, GenX does not induce cell death (n of 4 per group). Bars represent mean ± SEM.

Like most PFAS, GenX is persistent in the environment and has been shown to cause adverse effects in animal models (Brendel et al. 2018; Chambers et al. 2021; Joerss et al. 2020). In rodents, GenX is rapidly absorbed and eliminated exclusively through the urine. Male and female rats have a beta phase elimination half-life of 72.2 and 67.4 hours, respectively. In mice, the beta phase elimination half-life is 36.9 hours for males and 24.2 hours for females (Gannon et al. 2016). Studies using rat primary brain capillary cells and human cell lines (NCI/ADR-RES and MX-MCF-7) showed that GenX inhibits p-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) (Cannon et al. 2020). However, the half-life of GenX in humans remains unknown.

Recent studies have shown increasing accumulation of GenX in the environment. For example, GenX was found in the Lower Cape Fear River basin in North Carolina, the primary source of drinking water for surrounding towns, leading to human exposure (Guillette et al. 2020; Hopkins et al. 2018). In the Netherlands, GenX was found in the drinking water for multiple towns, including Zwijndrecht and Papendrecht (Gebbink and van Leeuwen 2020). Whereas significant data exist on serum concentrations of the long-chain legacy PFAS (PFAS perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) and PFOA) in occupational workers (Beggs et al. 2016; Chang et al. 2014; Olsen et al. 2007), on limited data exist for the levels of GenX in the serum of humans. A recent report by the Chemours Company measured the concentration of GenX in 24 human plasma samples, finding concentrations ranging from 1–51.2 ng/mL (0.0029–0.15 μM) (2021b). However, there was no other information in the study about the demographics or exposure time of the participants. Further, even less is known about the health effects of GenX exposure in humans. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) has set the oral reference doses (RfDs) for sub-chronic and chronic exposures to 0.00003 and 0.000003 mg/kg-day, respectively (2021a).

Several rodent studies indicate that the liver, specifically the hepatocytes, is a primary target of PFAS (Berthiaume and Wallace 2002; Chappell et al. 2020; Conley et al. 2019; Cui et al. 2009). Rodents exposed to GenX exhibited dose-dependent liver hypertrophy and transcriptomic changes in lipid metabolism, peroxisome processes, and xenobiotic metabolism (Chappell et al. 2020). In addition, female mice exposure to GenX during gestation caused hepatotoxicity and induction of the inflammatory pathways mediated by the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) in the liver, indicating that GenX is hepatotoxic and proinflammatory in rodents (Xu et al. 2022). However, adverse effects and the underlying mechanisms of GenX on human hepatocytes are not known. Here, we report the adverse effects of GenX on freshly isolated primary human hepatocytes (PHH) identified using global transcriptomic analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Primary Human Hepatocytes Isolating and Culture

Primary Human Hepatocytes (PHH) were isolated from human liver donors by the Cell Isolation Core at the University of Kansas Medical Center, as previously described (Xie et al. 2014). All human liver tissues were obtained with informed consent in accordance with the ethical and institutional guidelines. All studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of KUMC. PHH from four separate human liver donors were used in this study. Briefly, the livers were perfused first with EGTA (ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid) (1 mM) to chelate the calcium. This was followed by a collagenase (0.1 mg/ml) and protease (0.02 mg/ml) perfusion. The Glisson capsule of the liver was then severed to release the contained hepatocytes in ice-cold, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). A 50 g centrifugation was performed on the cells to purify the PHH from the other non-parenchymal cells. The PHH were then seeded at 1 × 106 cells per well on collagen-coated, 6-well plates and were cultured with phenol red-free Williams’ Medium E media (ThermoFisher cat # A1217601), supplemented to a final concentration of 10 mM HEPES buffer (ThermoFisher cat # 15630080) and 2 mM GlutaMAX™ (ThermoFisher cat # 35050061) by using the primary hepatocyte maintenance supplement kit (ThermoFisher cat # CM4000). The cells were allowed to attach overnight in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C.

2.2. PHH GenX Exposure

GenX (Synquest Laboratories cat # 2122-3-09) was dissolved in the culturing media to obtain a final concentration of 100 mM. The 100 mM stock was diluted in culturing media to 0.1 μM, 10 μM, and 100 μM concentrations. PHH were treated for either 48 hours or 96 hours at 37°C with 5% CO2. The media was changed every 48 hours. Studies included 4 biological replicates (PHH from four separate human livers) with 3 technical replicates per biological replicate. The 96-hour timepoint was selected as the longest timepoint to avoid complications associated with spontaneous dedifferentiation of PHH in culture. The treatment concentrations were selected for two observations. First, a study by the Chemours Company reported human serum concentrations within the range used (0.15 μM) (2021b). Second, past studies showed that occupational workers had PFOA and PFOS serum levels of 12.3 and 7.0 μM, respectively (Beggs et al. 2016). Given these findings, GenX serum levels in humans could be between 0.1 to 100 μM.

2.3. Lactate Dehydrogenase Activity

The lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay is a well-established method to measure cell death in hepatocytes (McGill et al. 2011; Rowan-Carroll et al. 2021; Xie et al. 2015; Yan et al. 2010). This assay is known to provide robust and reproducible results for determining toxicity (Kaja et al. 2017; Kumar et al. 2018). Additionally, LDH has the capacity to detect low levels of cell membrane damage compared to other assays (Allen et al. 1994; McGill et al. 2011). Given these factors, an LDH assay was used to establish GenX cytotoxicity, as previously described (Bajt et al. 2004; McGill et al. 2011). LDH was measured in both cell lysate and media. Briefly, 0.154 mg of NADH was added to 1 mL of Potassium Phosphate Pyruvate Buffer (KPP Buffer; KH2PO4 9.6 mM, K2HPO4 50.4 mM, Pyruvate 0.9 mM, pH 7.5) and was prewarmed to 37°C. Then, 5 μL of hepatocyte lysate and 15 μL of media were used to determine the amount of LDH in each fraction. Each was loaded into separate wells of a 96-well microplate, and 100 μL of NADH KPP buffer was added to each well. The absorbance was measured at 340 nm for 4 minutes to measure the loss of NADH. Concentrations were determined utilizing Beer– Lambert’s Law. The ratio of LDH concentration in the media and the total LDH concentration (amount of LDH in the media and cell lysate) were then calculated to determine the percent of LDH released for each sample.

2.3. Microarray Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from untreated and GenX-exposed cells using the TRIzol method, as previously stated (Robarts et al. 2022; Sandoval et al. 2019). An assessment of the quality and quantity of the RNA was made using the Agilent TapeStation 4200. All samples had an RNA integrity number equivalent (RINe) score greater than 9.8. As previously stated, microarray analysis was performed on pooled samples from the control, 0.1, 10 and 100 μM groups 96 hours after exposure (n of 3 -biological replicates, derived from separate liver donors) using the Human Clariom™ D Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) at the University of Kansas Medical Center Genomics Core (Borude et al. 2018). The raw microarray CEL data files were normalized and analyzed with Transcriptome Analysis Console software to produce fold change values (ThermoFisher, Version 4.0). The raw data were deposited into the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (GSE187633).

2.4. Pathway Analysis

To ascertain altered pathways, the Metascape tool (https://metascape.org/) was used on genes with a ±2-fold change cutoff (Zhou et al. 2019). This tool included the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Gene Ontology (GO), and REACTOME databases. Enriched pathway networks were constructed using the Cytoscape software (Shannon et al. 2003). Next, these genes were uploaded into the Qiagen’s Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) where functional pathways, tox function, canonical pathways, and upstream regulator analysis were performed, as previously stated (Bhushan et al. 2020; Robarts et al. 2022). The pathways with a p-value ≤ 0.05 and an absolute z-score ≥ 2 were considered significantly altered.

2.5. Determining Linear Concentration Response

A Pearson correlation was performed across all treatment groups for each gene, using both concentration and gene fold-change in RStudio (R version 4.0.3; RStudio Team). This was only performed if one or more of the treatment groups displayed a ±2-fold change of that gene. Genes that had a correlation coefficient greater than 0.99 or less than −0.99 were considered concentration-dependent genes. The concentration-dependent genes were then uploaded into the IPA software to determine concentration-dependent altered pathways.

2.6. Venn Diagram and Heatmap Construction

Heatmaps were generated using RStudio (R version 4.0.3; RStudio Team) with the heatmap.plus (Version 1.3), RcolorBrewer (Version 1.1–2), and gplots (Version 3.1.1) packages, as previously stated (Gunewardena et al. 2022). Colors were based on either -log10(p-value), z-score, or log2(fold-change); orange indicated upregulation, and blue indicated downregulation of gene expression. Euclidean distance with Ward linkage was used on rows to determine clustering. Venn Diagrams were generated using the package VennDiagram (Version 1.6.20), and colors were generated by using the RColorBrewer package.

2.7. Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

The total RNA isolated from each sample (3 biological replicates per group), that was concurrently used for the microarray, was also used for real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). The RNA concentrations were determined using the Implen NanoPhotometer® NP50. Four μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed to complementary DNA (cDNA) for each sample, using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (ThermoFisher, cat # 4368814). PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix was utilized to measure cDNA levels of various genes using a total of 100 ng of cDNA per reaction and a final forward and reverse primer concentration of 250 nM (ThermoFisher, cat # A25742). Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) produced and formulated all qPCR primers. The list of forward and reverse primer sequences is shown in Table S1. A 384-well plate setup was utilized for all qPCR reactions using the BioRad CFX384. These qPCR reactions were then analyzed in the CFX Maestro Software (Version 4.1.2433.1219). All cycle threshold (Ct) values were normalized to the Ct of 18S and then to the untreated group, using the 2–ΔΔCt method as previously described in depth (Livak and Schmittgen 2001).

2.8. Protein extraction and Western Blot Analysis

Hepatocytes were lysed in 300 μL of RIPA buffer (ThermoFisher cat # 89901) containing 1x Halt™ Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (ThermoFisher cat #78438) and 1x Halt™ Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (ThermoFisher cat # 78427). Protein concentration was measured using a Pierce™ Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Protein Assay Kit, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (ThermoFisher cat # 23225). The protein extracts were then diluted to 2 μg/μL in 1x Invitrogen™ NuPAGE™ LDS Sample Buffer (Fisher Scientific cat # NP0007) and 1x Invitrogen™ NuPAGE™ Antioxidant (Fisher Scientific cat # NP0005). The protein was loaded (20 μg total per sample) into a “NuPAGE™ 4 to 12%, Bis-Tris, 1.0–1.5 mm, Mini Protein Gels” (Fisher Scientific cat # NP0323BOX) and run at 140 volts for 1 hour and 45 minutes (3 biological replicates per group). The protein was then transferred into a MilliporeSigma™ Immobilon™-P PVDF Transfer Membrane (Millipore Sigma cat # IPVH00010) for 1 hour at 30 volts, followed by 30 minutes at 35 volts.

The primary antibodies used in this study include CDK4 (Cell Signaling cat # 12790), PCNA (Cell Signaling cat # 13110), phosphorylated-retinoblastoma (p-RB) (Cell Signaling cat # 8516), Ki67 (Cell Signaling cat # 9449), and GAPDH (Cell Signaling cat # 5174) and were used at a 1:1000 concentration diluted in 2% BSA. The secondary antibodies include horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated anti-mouse (Cell Signaling cat # 7076) or anti-rabbit (Cell Signaling cat # 7074) diluted at a 1:5000 concentration in 2% BSA. The blots were imaged on a Li-Cor Odyssey FC using the SuperSignal™ West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (ThermoFisher cat # PI34578). The densitometries of the bands of the western blots were calculated using the Image Studio Software (Version 5.2). The raw densitometry values were normalized to the densitometry of their respective loading control (GAPDH) and then to the normalized values of the respective paired, untreated PHH group.

2.9. Graphing and Statistical Analysis

The bar graphs were produced in GraphPad Prism (Version 9.1.2), with bars representing the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was tested between multiple groups using an ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s multiple comparison test. The difference between each group was considered significant if the p-value was less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. No cell death or morphological changes after GenX treatment

GenX exposure caused no significant morphological changes in the hepatocyte at any time point (Fig. 1B). To assess GenX cytotoxicity, we performed an LDH activity assay on the cellular fraction and the supernatant fraction after GenX exposure. There were no statistical differences between the untreated, 0.1 μM, 10 μM, and 100 μM groups at either 48 hours or 96 hours, indicating that there was no cytotoxicity at any dose (Fig. 1C). However, there was a concentration-dependent downward trend of LDH released in the GenX treatment groups (Fig. 1C).

3.2. GenX treatment caused significant gene transcriptional changes in PHH

Global transcriptomic analysis, using a Human Clariom™ D microarray array, showed significant gene expression changes 96 hours after GenX treatment (Table S2.). After a ±2-fold expression cutoff, a total of 831 genes (351 upregulated and 480 downregulated) were significantly changed in the 0.1 μM group, 1366 genes (453 upregulated and 913 downregulated) were significantly changed in the 10 μM group, and 1364 genes (826 upregulated and 538 downregulated) were significantly changed in the 100 μM groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of genes significantly altered upon GenX 96-hour treatment using a ±2 fold-change cutoff relative to the untreated PHH.

| Treatment | Upregulated | Downregulated |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 0.1 μM | 351 | 480 |

| 10 μM | 453 | 913 |

| 100 μM | 826 | 538 |

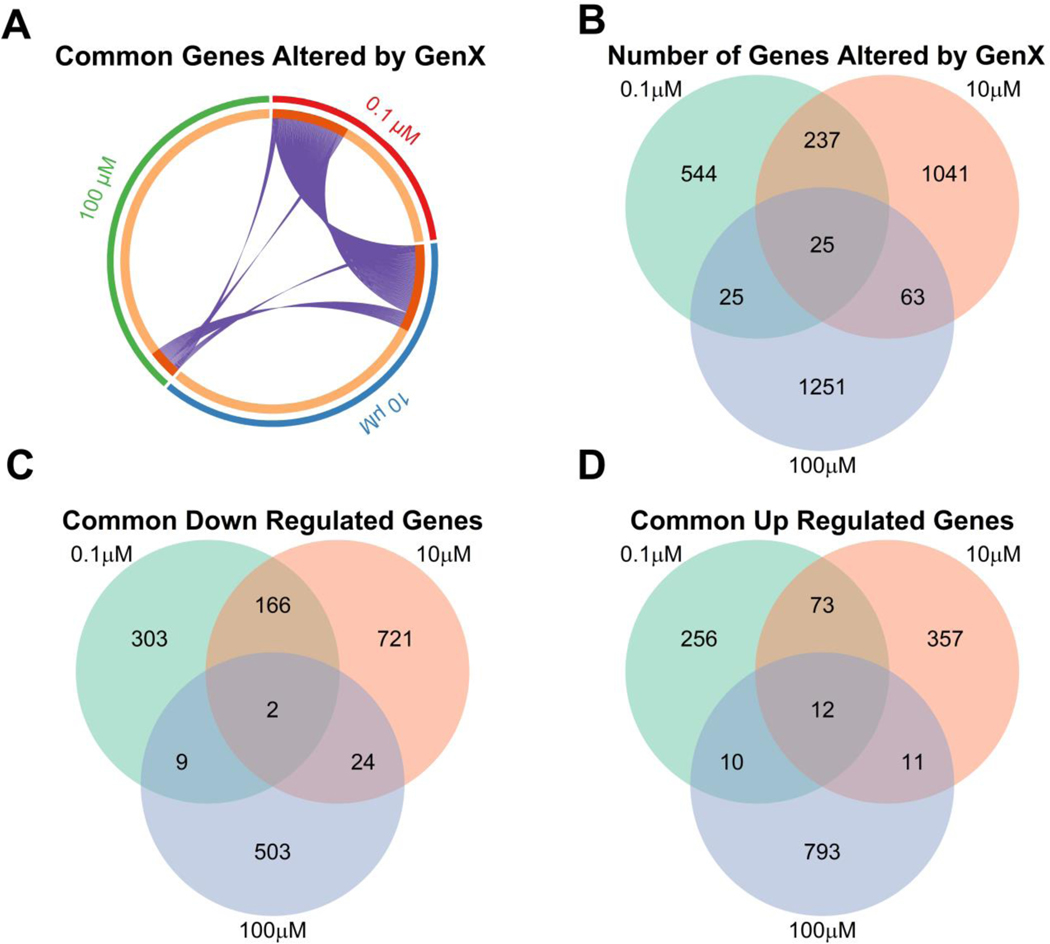

Overall, the 0.1 μM and 10 μM treatments showed similar altered gene expression profiles when compared to the 100 μM treatment, as shown by the chord plot and the Venn diagram (Fig. 2A–B). Among the downregulated genes, 166 were uniquely common between the 0.1 μM and 10 μM treatments, 24 were uniquely common between the 10 μM and 100 μM treatments, and 9 were uniquely common between the 0.1 μM and 100 μM treatments (Fig. 2C). Only two genes, Histone H2A type 1-B/E (HIST1H2AE) and UDP Glucuronosyltransferase Family 2 Member B10 (UGT2B10), were commonly downregulated between all three treatments (Fig. 2C, Table 2). Of the upregulated genes, 73 were uniquely common between 0.1 μM and 10 μM, 11 were uniquely common between 10 μM and 100 μM, and 10 were uniquely common between 0.1 μM and 100 μM (Fig. 2D). A total of 12 genes were commonly upregulated between all treatments (Fig. 2D, Table 3).

Figure 2. Significantly altered genes in PHH following 0.1, 10, and 100 μM GenX exposure.

(A) Cord plot of all genes for each group that had a ± 2-fold change (0.1 μM = red, 10 μM = blue, and 100 μM = green), where each purple line represents a shared gene between two groups. Venn diagrams of (B) all significant altered genes, (C) significantly downregulated, and (D) significantly upregulated genes using a ± 2-fold-change cutoff.

Table 2.

Common downregulated genes between 0.1, 10, and 100 μM treatments with corresponding fold change relative to the untreated PHH.

| Gene Symbol | 0.1μM | 10 μM | 100 μM |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| HIST1H2AE | −4.86 | −2.25 | −2.15 |

| UGT2B10 | −2.08 | −10.13 | −2.17 |

Table 3.

Common upregulated genes between 0.1, 10, and 100 μM treatments with corresponding fold change relative to the untreated PHH.

| Gene Symbol | 0.1 μM | 10 μM | 100 μM |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| DKCl | 2.31 | 3.11 | 2.06 |

| IGFBPl | 2.12 | 3.03 | 3.21 |

| LAMBl | 2.89 | 4.19 | 2.51 |

| LYVEl | 2.72 | 2.49 | 2.49 |

| MIR5580 | 2.25 | 2.25 | 2.32 |

| PLIN2 | 2.30 | 2.31 | 2.77 |

| RPll-436F23.1 | 2.11 | 2.07 | 3.45 |

| RRAGC | 2.06 | 2.25 | 2.19 |

| SNORA33 | 4.11 | 3.43 | 2.24 |

| SNORA4S | 2.48 | 2.57 | 3.29 |

| SNORD93 | 2.51 | 2.16 | 2.3 |

| VPS53 | 2.04 | 2.04 | 2.43 |

3.3. Metabolic pathway alterations after GenX treatment

To determine pathways impacted by the GenX treatment, we performed GO, REACTOME, and KEGG pathway analyses on significantly changed genes in 0.1, 10, and 100 μM-treated PHH. In all three treatment groups, “regulation of biological processes,” “metabolic processes,” and “cellular component organization” were significantly altered (Fig. 3A). “Cell proliferation” was predicted to be altered only in the 0.1 μM and 10 μM-treated PHH. Pathways impacted in only the 0.1 μM and 100 μM- treated PHH included “immune system process,” “signaling,” and “growth and biological adhesions” (Fig. 3A). Enrichment analysis revealed multiple impacted metabolic pathways (Fig. 3B). In all groups, “metabolism of lipids,” “regulation of lipid metabolic processes,” and “monocarboxylic acid metabolic process and biological oxidations” were significantly altered, indicating that GenX interferes with lipid metabolism. Pathways associated with cell proliferation, such as “cell cycle,” “phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase-protein kinase B (PI3K-Akt) signaling pathway,” and “small cell lung cancer” were enriched in the 0.1 μM and 100 μM-treated PHH. Further, genes involved in “mitotic prometaphase” were enriched in the 10 μM treatment group. The 0.1 μM and 10 μM groups had significant changes in “drug metabolism,” “positive regulation of locomotion,” and “SUMOylation” (Fig. 3B). To visualize the relationship between these enriched pathways, a network was constructed using the number of significantly impacted genes within the pathways and the similarity score produced by Cytoscape. Clusters were determined by using the MCODE algorithm to group pathways relative to their function. This revealed a large cluster across all three treatments for cell cycle, cell proliferation, and metabolism (Fig. 3C–D, Fig. S1A). Taken together, these data demonstrate that GenX at all doses impacts lipid metabolism and cell proliferation.

Figure 3. Gene Ontology (GO) analysis revealed metabolic changes in PHH treated with GenX.

(A) Biological pathways and (B) top enriched pathways in 0.1, 10, and 100 μM treated PHH. Euclidean distance and ward linkage was used to generate clustering. Color represents log10(p-value) for the impacted pathway with grey indicating no p-value. (C) Network analysis of altered pathways and (D) pie chart network of which treatment group altered within that pathway. The size of the dot represents the number of genes within the pathway that was significantly altered, where larger diameter equates to more impacted genes. The edges signify the similarity score produced by Cytoscape, where bolder means higher similarity score. Orange and green ovals represent metabolic and cell proliferation clusters, respectively.

3.4. 100 μM treatment caused significant alterations in inflammatory and fibrosis upstream regulators

We performed an upstream regulator analysis using the IPA software, which predicts the major signaling nodes activated based on the gene expression data provided. This analysis predicted that retinoblastoma transcriptional corepressor 1 (RB1) was significantly activated in the 0.1 μM treatment (Fig. 4A). Conversely, the regulators ribonucleoprotein 1 translational regulator (LARP1), Raf-1 Proto-Oncogene (RAF1), hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha (HIF1A), and Cyclin D1 (CCND1) were inhibited (Fig. 4A). In the 10 μM dose, Musculin (MSC), homeobox B13 (HOXB13), hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 alpha (HNF1A), HIF1A, hypoxia-inducible factor 2-alpha (EPAS1/HIF2A), and D-box binding PAR BZIP transcription factor (DBP) showed a substantial inhibition, accompanied with a significant increase in the predicted activity of lysine-specific demethylase, KDM5B (Fig. 4B). These data indicate that in the lower GenX concentrations, stress proteins and proliferation pathways are inactivated.

Figure 4. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) revealed extensive upstream regulator alterations.

Dot plots of (A) 0.1 μM, (B) 10 μM, and (C) 100 μM altered upstream regulators, exported from the IPA software using a z-score of a ± 2 cutoff. The red dash indicates a Z-Score of 0. The size of the dot indicates the number of altered genes within that pathway. Color represents the p-value.

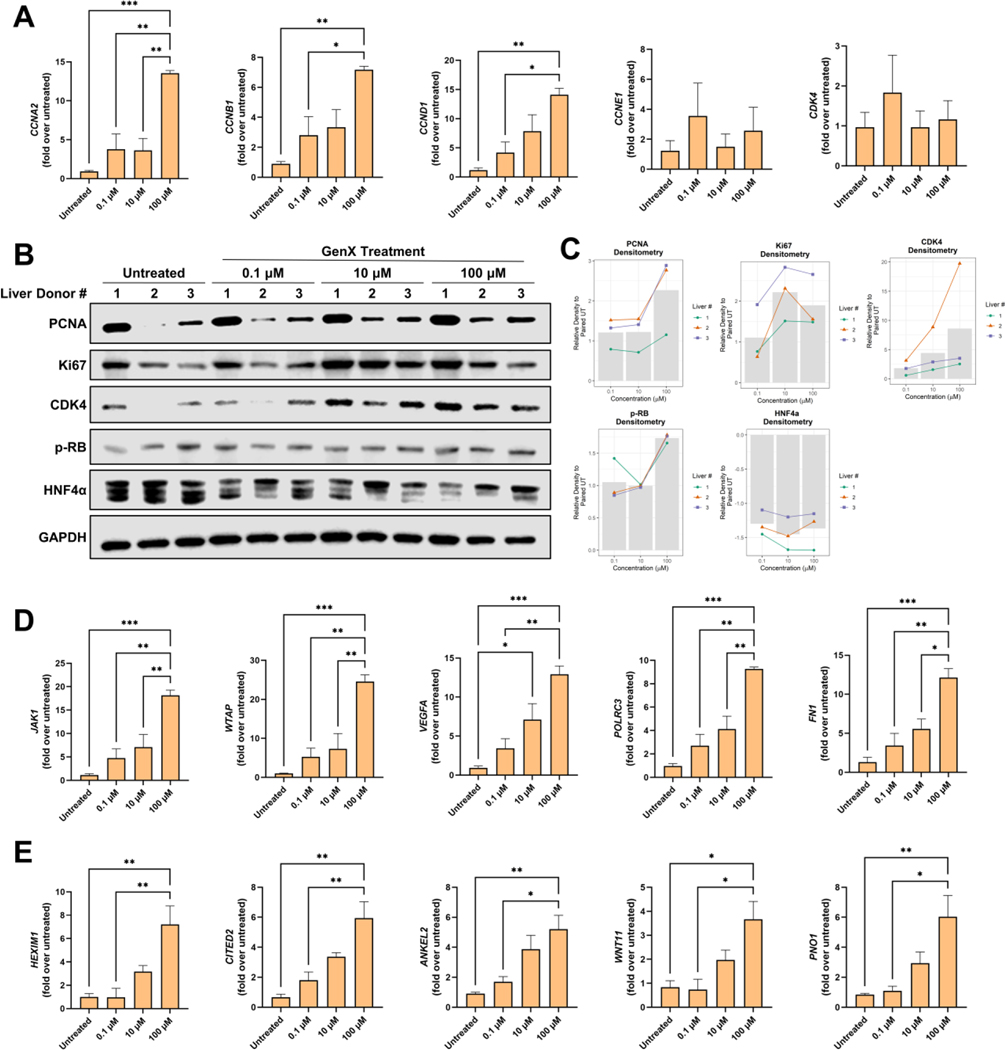

Compared to the 0.1 μM and 10 μM-treated PHH, the 100 μM treatment had more altered pathways. Pro-proliferative growth pathways such as hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src (SRC), and mitogen-activated protein kinase 1/2 (MAP2K1/2) were significantly activated (Fig. 4C). To further investigate the effects of GenX on proliferation, qPCR was used to measure the gene expression of promitogenic genes such as Cyclin A2 (CCNA2), Cyclin B1 (CCNB1), Cyclin D1 (CCND1), Cyclin E1 (CCNE1), and Cyclin Dependent Kinase 4 (CDK4) (Fig. 5A). qPCR analysis showed significant induction of proliferation in the 100 μM treatment group and an increasing trend in the 0.1 μM and 10 μM treatment groups. Western blot analysis of the promitogenic proteins, including proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), Ki67, CDK4, and phosphorylated-retinoblastoma (p-RB), showed an induction of these proliferative markers upon treatment, particularly PCNA, CDK4, and Ki67 (Fig. 5B–C). Conversely, Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4 Alpha (HNF4α), a nuclear receptor critical for hepatocyte differentiation and inhibition of proliferation (Huck et al. 2019; Walesky and Apte 2015), was decreased upon GenX exposure (Fig. 5B–C).

Figure 5. GenX-induced changes in genes involved in proliferation, inflammation and fibrosis.

(A) qPCR of genes related to cell proliferation, including Cyclin A1, B1, D1, E1, and CDK4. (B) Western blot analysis of cell proliferation regulators, derived from the three liver donors, for PCNA, Ki67, CDK4, p-RB, HNF4α, and GAPDH. (C) Bar graphs showing densitometric analysis of the western blots. In the bar graphs, green circles, orange triangles, and blue squares represent the liver donors 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The gray bar represents the mean of the normalized densitometry for each treatment group. qPCR of (D) inflammatory genes (SKG1, FN1, VEGFA, WTAP, JAK1, and POLRC3) and (E) fibrosis genes (HEXIM1, CITED2, ANKEL2, WNT11, and PNO1) identified in the IPA analysis. For qPCR, genes were normalized to the housekeeping gene 18s. All groups (n of 3 per group) were normalized to the untreated group. Bars represent mean ± SEM. ANOVA was performed followed by a Tukey’s post hoc test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001.

Activation of the inflammatory pathways, such as signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), were predicted to be significantly activated (Fig. 4C). Genes regulated by the proinflammatory upstream regulators STAT3 and Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) were identified in the IPA analysis. To validate this finding, representative genes contributing to the predicted activation of these proinflammatory pathways were measured by qPCR. GenX treatment resulted in dose-dependent induction of Serum/Glucocorticoid Regulated Kinase 1 (SGK1), fibronectin-1 (FN1), Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A (VEGFA), RNA Polymerase III Subunit C 3 (POLRC3), Janus Kinase 1 (JAK1), and WT1 Associated Protein (WTAP) (Fig. 5D). Additionally, the fibrosis pathways transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFB1) and mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4 (SMAD4) were activated in the 100 μM-treated PHH (Fig. 4C). To validate this finding, qPCR was performed (Fig. 5E). HEXIM P-TEFb Complex Subunit 1 (HEXIM1), Cbp/P300 Interacting Transactivator with Glu/Asp Rich Carboxy-Terminal Domain 2 (CITED2), Ankyrin Repeat and LEM Domain Containing 2 (ANKEL2), Wnt Family Member 11 (WNT11), and Partner of NOB1 Homolog (PNO1) were significantly increased and followed a dose-response (Fig. 5E). Accompanying this fibroinflammatory response, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha (PPARα), a known fatty acid metabolism regulator, was also activated in the 100 μM-treated PHH (Fig. 4C).

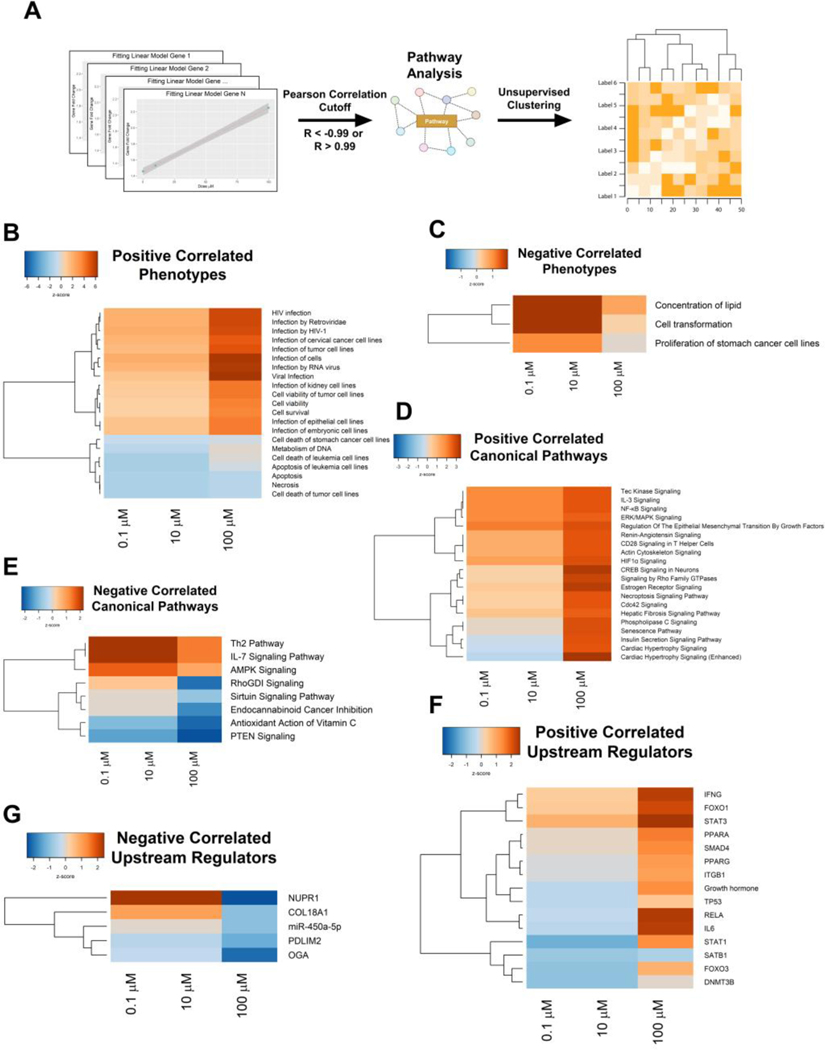

3.5. Inflammatory pathways followed a GenX concentration-dependent activation

To determine if transcriptional changes were occurring in a linear, concentration-dependent manner, we performed Pearson correlation analyses using the GenX concentrations and the fold changes of the genes (Fig. 6A). A total of 576 genes had at least one gene that had a ±2-fold change across any of the PHH treatment groups and had a correlation coefficient below −0.99 or above 0.99 (Fig. S2A–C, Table S3). These genes were then uploaded into the IPA software to determine dose-dependent pathway alterations. IPA analysis of these 576 genes showed that with increasing doses, GenX induced genes involved in “viral infection,” “inflammation,” and “cell survival/viability” (Fig. 6B). Similarly, genes involved in lipid metabolism and cell transformation exhibited a negative correlation with increasing doses of GenX (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, canonical pathways and upstream regulators related to inflammation were activated in a concentration-dependent manner, including interleukin 3 (IL3), nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB), Interferon Gamma (IFNG), STAT3, interleukin 6 (IL6), and Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 1 (STAT1) (Fig. 6D, F). The pathways such as phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), sirtuin signaling, and nuclear protein 1 (NUPR1) showed a negative correlation with the concentration of GenX (Fig. 6E, G). Representative genes identified in the dose-dependent IPA analysis were used to confirm the activities of the inflammatory pathways STAT3 (DTX3, VIM, and PGK1) and IL6 (THBS1, MERTK, and LY96). Lastly, qPCR analysis was performed on these representative genes and confirmed a dose-dependent trend (Fig. S2DE). Collectively, this indicates that GenX induces transcriptional changes associated with inflammation in a concentration-dependent manner.

Figure 6. GenX alters inflammatory pathways in a concentration-dependent manner.

Altered genes induced by GenX treatment that were either positively or negatively correlated were uploaded into IPA to determine concentration-dependent pathways. (A) Heatmaps of positively and (B) negatively correlated phenotypes that resemble those transcriptional profiles. (C) Heatmaps of positively and (D) negatively correlated canonical pathways. Upstream regulators that were (E) positively and (F) negatively correlated. Color represents Z-Score with Euclidean distance and ward linkage clustering.

4. Discussion

4.1. Cytotoxicity of GenX

Our objective in these studies was to define molecular hepatotoxicity of GenX over a broad dose range using human hepatocytes. One of the major concerns was if GenX would be overtly cytotoxic and lethal at any of the doses. Previous studies in NCI/ADR-RES, MX-MCF-7, and A549 cell lines had found that GenX was not cytotoxic at a 10 μM dose (Cannon et al. 2020; Jabeen et al. 2020). In other studies, GenX was shown to be cytotoxic at concentrations ranging from 0.003 to 2.9 μM in the Fischer rat thyroid cell line 5 (FRTL-5) (Coperchini et al. 2020). However, no data existed on the cytotoxicity on primary human hepatocytes. Our studies are the first to determine cytotoxicity of GenX on freshly isolated human hepatocytes. Our results are consistent with previous studies in NCI/ADR-RES and MX-MCF-7 cell lines, where no cytotoxicity and lethality were exhibited at 0.1, 10, and 100 μM for 48 and 96 hours.

4.2. Evidence that GenX activates PPARα

Activation of PPARα is a common mode of action for many PFAS, including GenX. Mice exposed to 1 and 5 mg/kg of GenX exhibited increased liver weight and hepatocellular hypertrophy (MacKenzie 2010; Wang et al. 2017). RNA sequencing of these livers revealed PPARα activation with increased fatty acid oxidation and lipogenesis in both male and female mice (Chappell et al. 2020). Consistent with this, our results also show that GenX induces concentration-dependent PPARα activation in PHH. GO analysis showed altered lipid metabolism at all three doses, which was confirmed by the IPA analysis. Metabolism of monocarboxylic acid, also regulated by PPARα, was also changed in all three treatment groups (Konig et al. 2010; Konig et al. 2008). Taken together, these data indicate that PPARα is activated by GenX. Further, these data suggests that a large metabolic remodeling occurs in PHH after GenX exposure. The relevance of GenX-induced PPARα is not clear given the relatively low level of PPARα expression in human livers, and the current thinking that it is a non-human relevant mechanism of toxicity (Choudhury et al. 2000; Hall et al. 2012; Palmer et al. 1998).

4.3. Inflammatory and Profibrotic Pathways are Activated by GenX

One of the most striking observations of our studies is the prominent activation of genes involved in both inflammation and fibrosis following high dose GenX exposure. While lower concentrations of GenX mainly perturbed lipid metabolism, the highest dose of GenX resulted in induction of several proinflammatory and profibrotic pathways, including IL3, IL6, IFNG, NF-κB and TGFβ.

The role of the TGFβ signaling pathway in inducing pro-fibrotic gene expression is well known (Fabregat and Caballero-Diaz 2018). The canonical pathway of TGFβ signaling involves binding TGFβ to the TGFβ2 receptor which heterodimerizes and activates the TGFβ1 receptor. TGFβ1 then phosphorylates SMAD2 and SMAD3, which then forms a complex with SMAD4. This complex translocates to the nucleus to upregulate its target genes (Xu et al. 2020). In addition, the a proinflammatory cytokine IL6 binds to the IL6 receptor, activating the STAT3 signaling pathway in cell proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Liu et al. 2014). Once activated, STAT3 promotes the expression of its target gene, Twist Family Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Transcription Factor 1 (TWIST1), a transcription factor with a significant role in the EMT (Cho et al. 2013). We observed a concentration-dependent activation in TGFβ1, IL6, STAT3, and TWIST1 signaling, indicating that at high concentrations GenX may promote fibrosis, inflammation, and EMT. Previous studies have shown that GenX induces inflammation through TLR4 by promoting lipopolysaccharides (LPS) leaking from the intestine (Xu et al. 2022). Our data indicate that GenX causes the activation of inflammatory pathways in PHH independent of LPS. Further studies are needed to determine the mechanism by which GenX induces TGFβ1 and IL6 signaling. These signaling pathways play a vital role in liver inflammation and fibrosis in chronic liver diseases, including nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and alcohol-associated steatohepatitis (ASH) (Gressner et al. 2002). While, there are no reports on the association between GenX and liver inflammatory diseases at this time, other PFAS, including PFOA, are known to cause liver inflammation and promote NASH (Jin et al. 2020; Marques et al. 2020; Sen et al. 2022; Yang et al. 2014). Our data warrant further studies on the role of GenX in fibroinflammatory liver diseases.

4.4. GenX Induces Cell Proliferation

Induing hepatocyte proliferation in rodents is a hallmark of PFAS. Several PFAS, including PFOA, PFOS, and perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) promote hepatocyte proliferation (Beggs et al. 2016; Buhrke et al. 2015). Rat studies have demonstrated that GenX increases mitotic figures in hepatocytes, indicating initiation of proliferation (Thompson et al. 2019). GenX also induced proliferation in human lung carcinoma cell lines at concentrations greater than 50 μM (Jabeen et al. 2020). In our studies, GenX induced pro-mitogenic pathways such as HGF, VEGF, SRC, MAP2K1/2, and Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 (FGF2) at the highest tested concentration (100 μM). HGF is a primary mitogen for hepatocytes, that activates multiple signaling pathways, including phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), SRC, phospholipase C-gamma (PLCγ), STAT3, and others via its receptor MET. Both HGF and MET are induced and activated in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (Block et al. 1996; Bowen et al. 2014; Cecchi et al. 2011; Michalopoulos and Bhushan 2021; Wang et al. 2020). Altogether, our findings show that GenX induces hepatocyte proliferation at high doses and corroborate previous data (Chappell et al. 2020; Jabeen et al. 2020). Further, we observed a dose dependent decrease in protein levels of HNF4α, the master regulator of hepatic differentiation (Walesky and Apte 2015; Walesky et al. 2013). Studies from our laboratory have shown that HNF4α inhibits hepatocyte proliferation, and the loss of HNF4α is a key feature in chronic liver diseases, including HCC (Gunewardena et al. 2022). These data indicate that at concentrations, GenX may stimulate promitogenic pathways and may inhibit anti-mitogenic and pro-differentiation pathways in hepatocytes.

5. Conclusion

In summary, our data have highlighted the molecular effects of GenX on PHH over a broad range of doses. We found that GenX disrupts lipid metabolism at lower concentrations and can induce fibroinflammatory signaling in hepatocytes. Our data shows that GenX could have major implications in liver diseases that involve significant inflammation and proliferation, such as NAFLD and hepatocellular carcinoma. As human exposure to GenX increases, it is critical to understand the effects on human health. Our studies highlight the critical need to determine the effects of GenX on human hepatocytes. Given the history of liver toxicity of previous PFAS (including PFOA, PFOS, and others), it is important to proactively investigate adverse effects of GenX on the liver and identify the underlying mechanisms.

Supplementary Material

Financial Support:

These studies were supported by NIH-COBRE (P20 RR021940–03, P30 GM118247, P30 GM122731), NIH S10OD021743, NIH R01 DK0198414 and NIH R56 DK112768

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 2021a. Fact Sheet: Human Health Toxicity Assessment for GenX Chemicals. In: Water O.o. (Ed), United States Enviromental Protection Agency. [Google Scholar]

- 2021b. Human Health Toxicity Values for Hexafluoropropylene Oxide (HFPO) Dimer Acid and Its Ammonium Salt (CASRN 13252–13-6 and CASRN 62037–80-3). In: W O.o. (4304T) (Ed), U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, p. 212. [Google Scholar]

- Agency, E.P. 2006. 2010/2015 PFOA Stewardship Program. In: E.P. Agency; (Ed), Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Allen M, Millett P, Dawes E. and Rushton N. 1994. Lactate dehydrogenase activity as a rapid and sensitive test for the quantification of cell numbers in vitro. Clin Mater 16, 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt ML, Knight TR, Lemasters JJ and Jaeschke H. 2004. Acetaminophen-induced oxidant stress and cell injury in cultured mouse hepatocytes: protection by N-acetyl cysteine. Toxicol Sci 80, 343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassler J, Ducatman A, Elliott M, Wen S, Wahlang B, Barnett J. and Cave MC 2019. Environmental perfluoroalkyl acid exposures are associated with liver disease characterized by apoptosis and altered serum adipocytokines. Environ Pollut 247, 1055–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beggs KM, McGreal SR, McCarthy A, Gunewardena S, Lampe JN, Lau C. and Apte U. 2016. The role of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4-alpha in perfluorooctanoic acid- and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid-induced hepatocellular dysfunction. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 304, 18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthiaume J. and Wallace KB 2002. Perfluorooctanoate, perflourooctanesulfonate, and N-ethyl perfluorooctanesulfonamido ethanol; peroxisome proliferation and mitochondrial biogenesis. Toxicol Lett 129, 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan B, Gunewardena S, Edwards G. and Apte U. 2020. Comparison of liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy and acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: A global picture based on transcriptome analysis. Food Chem Toxicol 139, 111186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake BE, Cope HA, Hall SM, Keys RD, Mahler BW, McCord J, Scott B, Stapleton HM, Strynar MJ, Elmore SA and Fenton SE 2020. Evaluation of Maternal, Embryo, and Placental Effects in CD-1 Mice following Gestational Exposure to Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) or Hexafluoropropylene Oxide Dimer Acid (HFPO-DA or GenX). Environ Health Perspect 128, 27006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block GD., Locker J., Bowen WC., Petersen BE., Katyal S., Strom SC., Riley T., Howard TA. and Michalopoulos GK. 1996. Population expansion, clonal growth, and specific differentiation patterns in primary cultures of hepatocytes induced by HGF/SF, EGF and TGF alpha in a chemically defined (HGM) medium. J Cell Biol 132, 1133–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borude P, Bhushan B, Gunewardena S, Akakpo J, Jaeschke H. and Apte U. 2018. Pleiotropic Role of p53 in Injury and Liver Regeneration after Acetaminophen Overdose. Am J Pathol 188, 1406–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen WC, Michalopoulos AW, Orr A, Ding MQ, Stolz DB and Michalopoulos GK 2014. Development of a chemically defined medium and discovery of new mitogenic growth factors for mouse hepatocytes: mitogenic effects of FGF1/2 and PDGF. PLoS One 9, e95487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendel S, Fetter E, Staude C, Vierke L. and Biegel-Engler A. 2018. Short-chain perfluoroalkyl acids: environmental concerns and a regulatory strategy under REACH. Environ Sci Eur 30, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck RC, Franklin J, Berger U, Conder JM, Cousins IT, de Voogt P, Jensen AA, Kannan K, Mabury SA and van Leeuwen SP 2011. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: terminology, classification, and origins. Integr Environ Assess Manag 7, 513–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrke T, Kruger E, Pevny S, Rossler M, Bitter K. and Lampen A. 2015. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) affects distinct molecular signalling pathways in human primary hepatocytes. Toxicology 333, 53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon RE, Richards AC, Trexler AW, Juberg CT, Sinha B, Knudsen GA and Birnbaum LS. 2020. Effect of GenX on P-Glycoprotein, Breast Cancer Resistance Protein, and Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein 2 at the Blood-Brain Barrier. Environ Health Perspect 128, 37002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchi F, Rabe DC and Bottaro DP 2011. The Hepatocyte Growth Factor Receptor: Structure, Function and Pharmacological Targeting in Cancer. Curr Signal Transduct Ther 6, 146–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers WS, Hopkins JG and Richards SM 2021. A Review of Per- and Polyfluorinated Alkyl Substance Impairment of Reproduction. Front Toxicol 3, 732436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang ET, Adami HO, Boffetta P, Cole P, Starr TB and Mandel JS 2014. A critical review of perfluorooctanoate and perfluorooctanesulfonate exposure and cancer risk in humans. Crit Rev Toxicol 44 Suppl 1, 1–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell GA, Thompson CM, Wolf JC, Cullen JM, Klaunig JE and Haws LC 2020. Assessment of the Mode of Action Underlying the Effects of GenX in Mouse Liver and Implications for Assessing Human Health Risks. Toxicol Pathol 48, 494–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho KH, Jeong KJ, Shin SC, Kang J, Park CG and Lee HY 2013. STAT3 mediates TGF-beta1-induced TWIST1 expression and prostate cancer invasion. Cancer Lett 336, 167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury AI, Chahal S, Bell AR, Tomlinson SR, Roberts RA, Salter AM and Bell DR 2000. Species differences in peroxisome proliferation; mechanisms and relevance. Mutat Res 448, 201–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conder JM, Hoke RA, De Wolf W, Russell MH and Buck RC 2008. Are PFCAs bioaccumulative? A critical review and comparison with regulatory criteria and persistent lipophilic compounds. Environ Sci Technol 42, 995–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley JM, Lambright CS, Evans N, Strynar MJ, McCord J, McIntyre BS, Travlos GS, Cardon MC, Medlock-Kakaley E, Hartig PC, Wilson VS and Gray LE Jr. 2019. Adverse Maternal, Fetal, and Postnatal Effects of Hexafluoropropylene Oxide Dimer Acid (GenX) from Oral Gestational Exposure in Sprague-Dawley Rats. Environ Health Perspect 127, 37008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coperchini F, Croce L, Denegri M, Pignatti P, Agozzino M, Netti GS, Imbriani M, Rotondi M. and Chiovato L. 2020. Adverse effects of in vitro GenX exposure on rat thyroid cell viability, DNA integrity and thyroid-related genes expression. Environ Pollut 264, 114778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L, Zhou QF, Liao CY, Fu JJ and Jiang GB 2009. Studies on the toxicological effects of PFOA and PFOS on rats using histological observation and chemical analysis. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 56, 338–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das KP, Grey BE, Rosen MB, Wood CR, Tatum-Gibbs KR, Zehr RD, Strynar MJ, Lindstrom AB and Lau C. 2015. Developmental toxicity of perfluorononanoic acid in mice. Reprod Toxicol 51, 133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabregat I. and Caballero-Diaz D. 2018. Transforming Growth Factor-beta-Induced Cell Plasticity in Liver Fibrosis and Hepatocarcinogenesis. Front Oncol 8, 357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Gao Y, Cui L, Wang T, Liang Y, Qu G, Yuan B, Wang Y, Zhang A. and Jiang G. 2016. Occurrence, temporal trends, and half-lives of perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) in occupational workers in China. Sci Rep 6, 38039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaballah S, Swank A, Sobus JR, Howey XM, Schmid J, Catron T, McCord J, Hines E, Strynar M. and Tal T. 2020. Evaluation of Developmental Toxicity, Developmental Neurotoxicity, and Tissue Dose in Zebrafish Exposed to GenX and Other PFAS. Environ Health Perspect 128, 47005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon SA., Fasano WJ., Mawn MP., Nabb DL., Buck RC., Buxton LW., Jepson GW. and Frame SR. 2016. Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and kinetics of 2,3,3,3-tetrafluoro-2-(heptafluoropropoxy)propanoic acid ammonium salt following a single dose in rat, mouse, and cynomolgus monkey. Toxicology 340, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebbink WA and van Leeuwen SPJ 2020. Environmental contamination and human exposure to PFASs near a fluorochemical production plant: Review of historic and current PFOA and GenX contamination in the Netherlands. Environ Int 137, 105583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R, Breitkopf K. and Dooley S. 2002. Roles of TGF-beta in hepatic fibrosis. Front Biosci 7, d793–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillette TC, McCord J, Guillette M, Polera ME, Rachels KT, Morgeson C, Kotlarz N, Knappe DRU, Reading BJ, Strynar M. and Belcher SM 2020. Elevated levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in Cape Fear River Striped Bass (Morone saxatilis) are associated with biomarkers of altered immune and liver function. Environ Int 136, 105358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunewardena S, Huck I, Walesky C, Robarts D, Weinman S. and Apte U. 2022. Progressive loss of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha activity in chronic liver diseases in humans. Hepatology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hall AP, Elcombe CR, Foster JR, Harada T, Kaufmann W, Knippel A, Kuttler K, Malarkey DE, Maronpot RR, Nishikawa A, Nolte T, Schulte A, Strauss V. and York MJ 2012. Liver hypertrophy: a review of adaptive (adverse and non-adverse) changes-conclusions from the 3rd International ESTP Expert Workshop. Toxicol Pathol 40, 971–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada K, Inoue K, Morikawa A, Yoshinaga T, Saito N. and Koizumi A. 2005. Renal clearance of perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluorooctanoate in humans and their species-specific excretion. Environ Res 99, 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidari H, Abbas T, Ok YS, Tsang DCW, Bhatnagar A. and Khan E. 2021. GenX is not always a better fluorinated organic compound than PFOA: A critical review on aqueous phase treatability by adsorption and its associated cost. Water Res 205, 117683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins ZR, Sun M, DeWitt JC and Knappe DRU 2018. Recently Detected Drinking Water Contaminants: GenX and Other Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Ether Acids. Journal - AWWA 110, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Huck I, Gunewardena S, Espanol-Suner R, Willenbring H. and Apte U. 2019. Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4 Alpha Activation Is Essential for Termination of Liver Regeneration in Mice. Hepatology 70, 666–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabeen M, Fayyaz M. and Irudayaraj J. 2020. Epigenetic Modifications, and Alterations in Cell Cycle and Apoptosis Pathway in A549 Lung Carcinoma Cell Line upon Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances. Toxics 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AA and Warming M. 2015. Short-chain Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS).

- Jin R., McConnell R., Catherine C., Xu S., Walker DI., Stratakis N., Jones DP., Miller GW., Peng C., Conti DV., Vos MB. and Chatzi L. 2020. Perfluoroalkyl substances and severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver in Children: An untargeted metabolomics approach. Environ Int 134, 105220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joerss H, Xie Z, Wagner CC, von Appen WJ, Sunderland EM and Ebinghaus R. 2020. Transport of Legacy Perfluoroalkyl Substances and the Replacement Compound HFPO-DA through the Atlantic Gateway to the Arctic Ocean-Is the Arctic a Sink or a Source? Environ Sci Technol 54, 9958–9967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaja S, Payne AJ, Naumchuk Y. and Koulen P. 2017. Quantification of Lactate Dehydrogenase for Cell Viability Testing Using Cell Lines and Primary Cultured Astrocytes. Curr Protoc Toxicol 72, 2 26 21–22 26 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kancharla S, Choudhary A, Davis RT, Dong D, Bedrov D, Tsianou M. and Alexandridis P. 2022. GenX in water: Interactions and self-assembly. J Hazard Mater 428, 128137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig B, Fischer S, Schlotte S, Wen G, Eder K. and Stangl GI 2010. Monocarboxylate transporter 1 and CD147 are up-regulated by natural and synthetic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha agonists in livers of rodents and pigs. Mol Nutr Food Res 54, 1248–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig B, Koch A, Giggel K, Dordschbal B, Eder K. and Stangl GI 2008. Monocarboxylate transporter (MCT)-1 is up-regulated by PPARalpha. Biochim Biophys Acta 1780, 899–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Nagarajan A. and Uchil PD 2018. Analysis of Cell Viability by the Lactate Dehydrogenase Assay. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li Y, Fletcher T, Mucs D, Scott K, Lindh CH, Tallving P. and Jakobsson K. 2018. Half-lives of PFOS, PFHxS and PFOA after end of exposure to contaminated drinking water. Occup Environ Med 75, 46–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom AB, Strynar MJ and Libelo EL 2011. Polyfluorinated compounds: past, present, and future. Environ Sci Technol 45, 7954–7961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RY, Zeng Y, Lei Z, Wang L, Yang H, Liu Z, Zhao J. and Zhang HT 2014. JAK/STAT3 signaling is required for TGF-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung cancer cells. Int J Oncol 44, 1643–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie SA 2010. DuPont-18405–1307: H-28548: Subchronic Toxicity 90-Day Gavage Study in Mice. OECD Guideline 408. E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, Newark, Delaware. [Google Scholar]

- Marques E., Pfohl M., Auclair A., Jamwal R., Barlock BJ., Sammoura FM., Goedken M., Akhlaghi F. and Slitt AL. 2020. Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) administration shifts the hepatic proteome and augments dietary outcomes related to hepatic steatosis in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 408, 115250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill MR, Yan HM, Ramachandran A, Murray GJ, Rollins DE and Jaeschke H. 2011. HepaRG cells: a human model to study mechanisms of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Hepatology 53, 974–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalopoulos GK and Bhushan B. 2021. Liver regeneration: biological and pathological mechanisms and implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 18, 40–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen GW, Burris JM, Ehresman DJ, Froehlich JW, Seacat AM, Butenhoff JL and Zobel LR 2007. Half-life of serum elimination of perfluorooctanesulfonate,perfluorohexanesulfonate, and perfluorooctanoate in retired fluorochemical production workers. Environ Health Perspect 115, 1298–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer CN, Hsu MH, Griffin KJ, Raucy JL and Johnson EF 1998. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-alpha expression in human liver. Mol Pharmacol 53, 14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul Douglas Brothers, Leung LH and Gangal SV. 2009. Abatement of Fluoroether Carboxylic Acids or Salts Employed in Fluoropolymer Resin Manufacture. In: E.I.D.P.D.N.A. Company; (Ed), Worldwide applications. [Google Scholar]

- Peden-Adams MM, Keller JM, Eudaly JG, Berger J, Gilkeson GS and Keil DE 2008. Suppression of humoral immunity in mice following exposure to perfluorooctane sulfonate. Toxicol Sci 104, 144–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robarts DR, McGreal SR, Umbaugh DS, Parkes WS, Kotulkar M, Abernathy S, Lee N, Jaeschke H, Gunewardena S, Whelan SA, Hanover JA, Zachara NE, Slawson C. and Apte U. 2022. Regulation of Liver Regeneration by Hepatocyte O-GlcNAcylation in Mice. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rowan-Carroll A., Reardon A., Leingartner K., Gagne R., Williams A., Meier MJ., Kuo B., Bourdon-Lacombe J., Moffat I., Carrier R., Nong A., Lorusso L., Ferguson SS., Atlas E. and Yauk C. 2021. High-throughput transcriptomic analysis of human primary hepatocyte spheroids exposed to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) as a platform for relative potency characterization. Toxicol Sci. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sandoval K, Umbaugh D, House A, Crider A. and Witt K. 2019. Somatostatin Receptor Subtype-4 Regulates mRNA Expression of Amyloid-Beta Degrading Enzymes and Microglia Mediators of Phagocytosis in Brains of 3xTg-AD Mice. Neurochem Res 44, 2670–2680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen P, Qadri S, Luukkonen PK, Ragnarsdottir O, McGlinchey A, Jantti S, Juuti A, Arola J, Schlezinger JJ, Webster TF, Oresic M, Yki-Jarvinen H. and Hyotylainen T. 2022. Exposure to environmental contaminants is associated with altered hepatic lipid metabolism in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 76, 283–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B. and Ideker T. 2003. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 13, 2498–2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein CR, McGovern KJ, Pajak AM, Maglione PJ and Wolff MS 2016. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances and indicators of immune function in children aged 12–19 y: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Pediatr Res 79, 348–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suja F, Pramanik BK and Zain SM 2009. Contamination, bioaccumulation and toxic effects of perfluorinated chemicals (PFCs) in the water environment: a review paper. Water Sci Technol 60, 1533–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CM, Fitch SE, Ring C, Rish W, Cullen JM and Haws LC 2019. Development of an oral reference dose for the perfluorinated compound GenX. J Appl Toxicol 39, 1267–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walesky C. and Apte U. 2015. Role of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha (HNF4alpha) in cell proliferation and cancer. Gene Expr 16, 101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walesky C, Gunewardena S, Terwilliger EF, Edwards G, Borude P. and Apte U. 2013. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha in adult mice results in increased hepatocyte proliferation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 304, G26–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Rao B, Lou J, Li J, Liu Z, Li A, Cui G, Ren Z. and Yu Z. 2020. The Function of the HGF/c-Met Axis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol 8, 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Wang X, Sheng N, Zhou X, Cui R, Zhang H. and Dai J. 2017. RNA-sequencing analysis reveals the hepatotoxic mechanism of perfluoroalkyl alternatives, HFPO2 and HFPO4, following exposure in mice. J Appl Toxicol 37, 436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Mi X., Zhou Z., Zhou S., Li C., Hu X., Qi D. and Deng S. 2019. Novel insights into the competitive adsorption behavior and mechanism of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances on the anion-exchange resin. J Colloid Interface Sci 557, 655–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong F, MacLeod M, Mueller JF and Cousins IT 2015. Response to Comment on “Enhanced Elimination of Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid by Menstruating Women: Evidence from Population-based Pharmacokinetic Modeling”. Environ Sci Technol 49, 5838–5839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, McGill MR, Dorko K, Kumer SC, Schmitt TM, Forster J. and Jaeschke H. 2014. Mechanisms of acetaminophen-induced cell death in primary human hepatocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 279, 266–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Woolbright BL, Kos M, McGill MR, Dorko K, Kumer SC, Schmitt TM and Jaeschke H. 2015. Lack of Direct Cytotoxicity of Extracellular ATP against Hepatocytes: Role in the Mechanism of Acetaminophen Hepatotoxicity. J Clin Transl Res 1, 100–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu LL, Chen YK, Zhang QY, Chen LJ, Zhang KK, Li JH, Liu JL, Wang Q. and Xie XL 2022. Gestational exposure to GenX induces hepatic alterations by the gut-liver axis in maternal mice: A similar mechanism as PFOA. Sci Total Environ 820, 153281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Sun X, Zhang R, Cao T, Cai SY, Boyer JL, Zhang X, Li D. and Huang Y. 2020. A Positive Feedback Loop of TET3 and TGF-beta1 Promotes Liver Fibrosis. Cell Rep 30, 1310–1318 e1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan HM, Ramachandran A, Bajt ML, Lemasters JJ and Jaeschke H. 2010. The oxygen tension modulates acetaminophen-induced mitochondrial oxidant stress and cell injury in cultured hepatocytes. Toxicol Sci 117, 515–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Zou W, Hu Z, Liu F, Zhou L, Yang S, Kuang H, Wu L, Wei J, Wang J, Zou T. and Zhang D. 2014. Involvement of oxidative stress and inflammation in liver injury caused by perfluorooctanoic acid exposure in mice. Biomed Res Int 2014, 409837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Beesoon S, Zhu L. and Martin JW 2013. Biomonitoring of perfluoroalkyl acids in human urine and estimates of biological half-life. Environ Sci Technol 47, 10619–10627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Zhou B., Pache L., Chang M., Khodabakhshi AH., Tanaseichuk O., Benner C. and Chanda SK. 2019. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun 10, 1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.