Abstract

To localize Haemophilus ducreyi in vivo, human subjects were experimentally infected with H. ducreyi until they developed a painful pustule or for 14 days. Lesions were biopsied, and biopsy samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and cryosectioned. Sections were stained with polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum or H. ducreyi-specific monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) and fluorescently tagged secondary antibodies and examined by confocal microscopy. We identified H. ducreyi in 16 of 18 pustules but did not detect bacteria in the one papule examined. H. ducreyi was observed as individual cells and in clumps or chains. Staining with MAbs 2D8, 5C9, 3B9, 2C7, and 9D12 demonstrated that H. ducreyi expresses the major pilus subunit, FtpA, the 28-kDa outer membrane protein Hlp, the 18-kDa outer membrane protein PAL, and the major outer membrane protein (MOMP) or OmpA2 in vivo. By dual staining with polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum and MAbs that recognize human skin components, we observed bacteria within the neutrophilic infiltrates of all positively staining pustules and in the dermis of 10 of 16 pustules. We were unable to detect bacteria associated with keratinocytes in the samples examined. The data suggest that H. ducreyi is found primarily in association with neutrophils and in the dermis at the pustular stage of disease in the human model of infection.

Haemophilus ducreyi is the causative agent of chancroid, a sexually transmitted genital ulcer disease that facilitates the transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (10). H. ducreyi preferentially infects mucosal epithelial surfaces of the coronal sulcus and foreskin in males and the fourchette and labia in females but also infects stratified squamous epithelium (12). The organism enters the host through microabrasions that occur during intercourse and remains localized primarily in the skin. At the ulcerative stage of disease, H. ducreyi may disseminate to regional lymph nodes (22).

Very little is known about the interactions of H. ducreyi with components of human skin. Localization of H. ducreyi in naturally occurring lesions has been hindered by the fact that most patients do not seek treatment until the ulcerative stage, when the lesions are usually colonized or superinfected with other bacteria. In tissue samples from patients with suspected but not culture-proven chancroid, gram-negative coccobacilli were seen between the polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) in the superficial zone of the ulcer (11, 14, 25). Specimens from patients with culture-proven chancroid contain bacterial structures within the ulcer and in the superficial dermis (20, 23). The bacteria were primarily extracellular, as detected by electron microscopy (21); however, this study did not describe where the bacteria were located in the tissue. None of these studies confirmed that the bacterial structures were H. ducreyi, and none examined bacterial localization at earlier stages of the disease.

H. ducreyi binds to several skin components in vitro, including keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and epithelial cells (2, 9, 18, 19, 30), as well as to extracellular matrix proteins, including types I and III collagen, fibronectin, and laminin (1, 7). However, the relevance of these findings to human disease is unknown.

To study the initial pathogenesis of chancroid, we developed a human model of H. ducreyi infection (6, 28, 29). In this model, volunteers are inoculated on the upper arm with H. ducreyi via puncture wounds made by an allergy-testing device. Features of the model include a low estimated delivered dose (EDD) of bacteria, kinetics of papule and pustule formation that resemble the initial stages of chancroid, and a cutaneous infiltrate of PMN and mononuclear cells that closely mimics the histopathology of naturally occurring ulcers (3, 24, 28). For subject safety considerations, infection is terminated when a subject develops a painful pustule or after 14 days of infection.

In this study, we examined lesions from the human model of infection by immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy. Using antibodies (Ab) that specifically label the bacteria or components of human skin, we localized H. ducreyi at the pustular stage of disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue specimens.

Tissue specimens were obtained from 14 adult volunteers who participated in several parent/mutant trials (see Table 1) (5, 29a, 31; R. S. Young, K. Fortney, E. J. Hansen, and S. M. Spinola, unpublished data). Volunteers were inoculated on the upper arm using an allergy-testing device that punctures the skin with nine tines to a depth of 1.9 mm. Volunteers received EDDs of 30 to 120 CFU of H. ducreyi 35000 or 35000HP and isogenic derivatives of these strains. Sites were observed until the clinical end point, defined as resolution of disease, development of a painful pustule, or 14 days of infection. At the clinical end point, lesions were biopsied with 4- to 6-mm punch forceps, and the specimens were divided longitudinally. One portion of each specimen was homogenized and cultured on chocolate agar plates at 33 to 35°C under 5% CO2.

TABLE 1.

Sources of tissue samples analyzed and culture and microscopic results

| Parent/mutant trial | Subject/siteb | Final outcome | Detection of H. ducreyi bya:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culturec | Microscopyd | |||

| HgbAe | 102/Parent | Pustule | + | + |

| 105/Parent | Pustule | + | + | |

| 107/Parent | Papule | − | − | |

| 110/Parent | Pustule | + | + | |

| MOMPf | 111/Parent | Pustule | + | + |

| 114/Parent | Pustule | + | + | |

| 115/Mutant | Pustule | − | + | |

| STg | 119/Parent | Pustule | + | − |

| CDTh | 121/Parent | Pustule | + | + |

| 121/Mutant | Pustule | + | + | |

| 125/Parent | Pustule | − | − | |

| 126/Parent | Pustule | + | + | |

| 126/Mutant | Pustule | + | + | |

| 127/Parent | Pustule | + | + | |

| 127/Mutant | Pustule | + | + | |

| 128/Parent | Pustule | + | + | |

| 128/Mutant | Pustule | + | + | |

| 129/Parent | Pustule | + | + | |

| 129/Mutant | Pustule | + | + | |

+, H. ducreyi was detected; −, no H. ducreyi was detected.

The numbers given are identification numbers for the volunteers. Parent, sites inoculated with H. ducreyi 35000 or 35000HP; Mutant, sites inoculated with an isogenic mutant.

Results of cultures of specimens.

Results of confocal microscopic examination of sections stained with polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum.

HgbA, hemoglobin receptor (5).

MOMP, major outer membrane protein (29a).

ST, sialyltransferase (31).

CDT, cytolethal distending toxin (Young et al., unpublished).

Specimens for microscopy were fixed for 1.5 to 2.5 h with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (7), washed in PBS, and stored in 0.25% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4°C. Within 1 month of harvest, the samples were cryoprotected in 20% sucrose at 4°C overnight, embedded in optimal cutting temperature medium (Miles, Inc., Elkhart, Ind.), and frozen in liquid N2, and the entire sample was cut into 10-μm sections with a cryostat. Sections were collected on Superfrost Plus microscope slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa.) and stored at −20°C until use. We obtained between 150 and 360 sections from each tissue sample.

Antibodies and stains.

H. ducreyi was detected with rabbit polyclonal antiserum raised against whole H. ducreyi cells (15) or with murine monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) recognizing specific H. ducreyi surface antigens (see Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Reactivity of MAbs with H. ducreyi cells in tissue samples

| MAb | Antigen | Reactivity | Na | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D8 | FtpA | + | 4 | 8 |

| 3B9 | PAL | + | 2 | 26 |

| 5C9 | Hlp | + | 3 | 16 |

| 2C7 | MOMP, OmpA2 | + | 1 | 17, 27 |

| 9D12 | MOMP, OmpA2 | + | 4 | 13, 17 |

| 3F12 | MOMP | − | 2 | 17 |

N indicates the number of specimens probed with each MAb.

MAbs recognizing eukaryotic antigens included anti-neutrophil elastase MAb NP57 (Dako Corp., Carpinteria, Calif.), anti-neutrophil lactoferrin MAb AHN-9 (PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.), anti-multi-cytokeratin MAbs AE1 and AE3 (Novocastra/Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.), and anti-vimentin MAb VIM 3B4 (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.). Eukaryotic cell membranes were stained with tetramethylrhodamine-6-isothiocyanate (TRITC)-labeled Lens culinaris agglutinin (LCA) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.).

Secondary Ab (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, Pa.) included goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G and goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G, which were affinity purified and conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or indodicarbocyanine (Cy5). For dual labeling experiments, we purchased goat anti-mouse Ab that had been preabsorbed with rabbit serum or immunoglobulins to minimize cross-reactivity with rabbit Ab and goat anti-rabbit Ab that had been preabsorbed with mouse serum or immunoglobulins to minimize cross-reactivity with mouse Ab. Normal goat serum was also obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories.

Staining sections and confocal microscopy.

Sections were stained and examined by confocal microscopy as previously described (4). Briefly, sections were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min, washed three times for 2 min each in PBS, and blocked with 5% normal goat serum in PBS for 30 min. The sections were stained with primary Ab in PBS for 2 h, blocked with 5% normal goat serum in PBS for 30 min, and incubated with fluorescently labeled secondary Ab for 1 h. They were washed three times for 2 min each in PBS after each incubation and for 2 min in H2O after the final incubation. When used, TRITC-LCA was added simultaneously with the secondary Ab. Samples were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories) and examined under a Bio-Rad MRC 1024 confocal laser-scanning microscope. Images were collected separately for FITC, TRITC, and Cy5 signals, and the images were colorized and combined using MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging Corp., West Chester, Pa.).

Negative controls included omitting each primary Ab, omitting each secondary Ab, and staining sections of uninfected upper arm skin obtained from a healthy adult volunteer. No bacterial structures were found when the primary Ab was omitted during staining of infected tissue. When the secondary Ab was omitted, a background of autofluorescence of the tissue was observed in the FITC channel; however, no bacterial structures were seen in any channel used. No bacterial structures were observed when the anti-H. ducreyi primary Ab were used to stain sections of uninfected skin.

RESULTS

In vivo immunodetection of H. ducreyi.

We examined 19 tissue specimens obtained by biopsy from 14 volunteers who participated in one of four parent/mutant trials using the human model of H. ducreyi infection (Table 1) (5, 29a, 31; Young et al., unpublished). The specimens were obtained from sites inoculated with EDDs of 30 to 120 CFU of H. ducreyi 35000 or 35000HP and their isogenic derivatives (Table 1). A portion of each specimen was cultured on nonselective medium. Most were culture positive for H. ducreyi (Table 1). No other bacteria were recovered from any specimen.

To screen for H. ducreyi in these lesions, every 30th section of each specimen was stained with polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum and FITC-labeled secondary Ab and examined by confocal microscopy. Thus, 5 to 12 sections were screened per specimen. Bacteria were seldom detected in all sections stained from a given specimen. However, when found, they were always present in at least two consecutively analyzed sections. Therefore, if no bacteria were seen in every 30th section, the tissue was scored as negative for H. ducreyi by microscopy (Table 1). We observed positively staining bacterial structures in 16 of 19 specimens examined, including 15 of 16 culture-positive specimens and 1 of 3 culture-negative specimens (Table 1). We found bacteria in 16 of 18 pustules but not in the one papule examined (Table 1). For each section screened, a serial section was stained identically except that the primary Ab was omitted. No bacterial structures were ever observed in these sections.

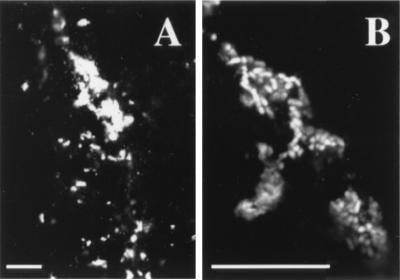

The bacteria had a morphology characteristic of H. ducreyi, including rod-shaped cells occurring singly or in chains or clusters (Fig. 1). We frequently observed clumps of brightly staining material (Fig. 1A). When visualized under higher magnification and with a narrower focal plane, these were found to be made up of numerous coccobacilli (Fig. 1B). The coccobacilli were estimated to be 1 to 2.5 μm long, consistent with the size range described for H. ducreyi.

FIG. 1.

Bacterial structures detected in vivo. The section was stained with polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum and FITC-labeled secondary Ab (white). (A) Bacteria within the epidermal pustule of a lesion. (B) Higher-magnification view of the clumps in panel A. Bars, 10 μm.

We also examined sections from four specimens that had been harvested, fixed, and stored, as described above, for 5 to 6 months prior to sectioning. All were culture-positive pustules. No bacteria were found in these specimens (data not shown), indicating that sectioning soon after harvest may be required to retain bacterial antigenicity. Once sectioned, however, stored specimens retained antigenicity as long as 11 months after sectioning (data not shown).

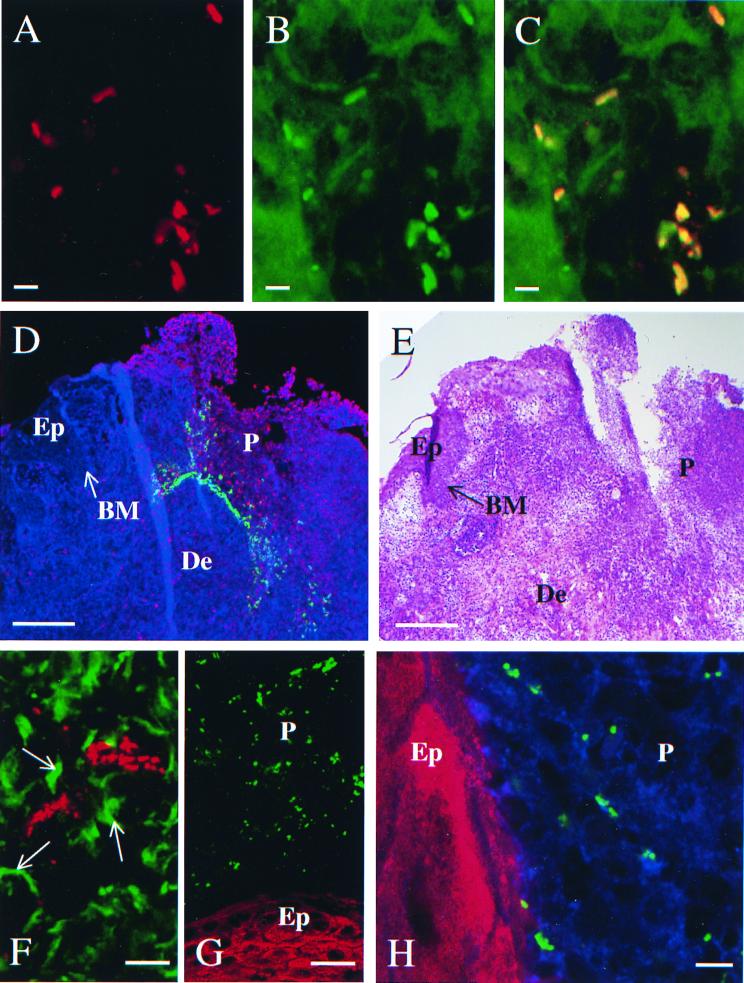

To confirm that the bacteria identified by the polyclonal antiserum were H. ducreyi, we stained sections with a panel of MAbs that recognize H. ducreyi surface antigens followed by FITC-labeled secondary Ab. Bacteria were recognized by five of six MAbs tested (Table 2). In dual labeling experiments, sections were stained simultaneously with an anti-H. ducreyi MAb and polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum followed by FITC-labeled anti-mouse and Cy5-labeled anti-rabbit secondary Ab. Figure 2 shows the results with MAb 5C9, which specifically recognizes H. ducreyi but no other Haemophilus species or any other genera tested (16). Bacteria were identified with each primary Ab (Fig. 2A and B), and when combined, the two signals colocalized to the same structures (Fig. 2C). Similar results were obtained with MAb 2D8, reported previously (4), and with MAbs 2C7, 3B9, and 9D12 (data not shown). No bacteria were identified by MAbs or polyclonal antiserum in uninfected control tissue. We concluded that the structures identified by the polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum in these tissue specimens were H. ducreyi and that FtpA, PAL, Hlp, and the major outer membrane protein (MOMP) or OmpA2 or both are expressed in vivo.

FIG. 2.

Detection (A through C) and localization (D through H) of H. ducreyi. (A) Bacteria stained with polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum, detected with Cy5-labeled secondary Ab (red). (B) Bacteria stained with MAb 5C9, detected with FITC-labeled secondary Ab (green). (C) Combined images of A and B, demonstrating colocalization (yellow/orange) of the two primary Abs. Bars, 2.5 μm. (D) Section stained with anti-neutrophil lactoferrin, detected with FITC-labeled secondary Ab (red); polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum, detected with Cy5-labeled secondary Ab (green); and TRITC-LCA (blue). BM, basement membrane (arrow); De, dermis; Ep, epidermis; P, pustule. Bar, 200 μm. Note that the neutrophil infiltrate of the pustule disrupts and replaces the epidermis and that H. ducreyi is found primarily within the pustule and also in the dermis. (E) Hematoxylin-eosin stained serial section of panel D to provide orientation. Bar, 200 μm. (F) Section stained with anti-vimentin, detected with FITC-labeled secondary Ab (green), and polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum, detected with Cy5-labeled secondary Ab (red). Arrows indicate fibroblasts stained with vimentin; the image confirms that some bacteria are found in the dermis. Bar, 20 μm. (G) Bacteria were stained with polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum, detected with Cy5-labeled secondary Ab (green); keratinocytes were stained with anti-cytokeratins, detected with FITC-labeled secondary Ab (red). Bar, 20 μm. Note that the anti-cytokeratin is staining the keratinocytes of the epidermis (Ep) and that H. ducreyi is found within the adjacent pustule (P). (H) Higher-power view of serial section stained as in panel G and with TRITC-LCA (blue). Note that the lectin stains the plasma membranes of the neutrophils within the epidermal pustule (P) and that the bacteria are present among the neutrophils but not on the keratincytes of the epidermis (Ep). Bar, 5 μm.

Localization of H. ducreyi in lesions.

To localize H. ducreyi, we stained sections simultaneously with polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum and MAbs recognizing eukaryotic components of the lesions followed by Cy5-labeled anti-rabbit and FITC-labeled anti-mouse secondary Ab. The lectin LCA was used as a plasma membrane stain to show the general architecture of the section and the presence of eukaryotic cells in otherwise unstained fields. For these studies, we examined sections from all 16 specimens in which bacteria were found (Table 1). Figure 2D shows a section of a typical tissue specimen stained with anti-PMN lactoferrin and polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum, in which the bacteria were widely distributed throughout the epidermal pustule, heavily concentrated at its base, and found in the surrounding dermis. Figure 2E shows a serial section stained with hematoxylin and eosin to provide orientation.

Sections doubly stained with anti-PMN elastase and polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum confirmed that numerous H. ducreyi cells were found in the pustule, mainly associated with the PMN (data not shown). All 16 specimens contained bacteria in the pustule.

Vimentin is an intermediate filament present in fibroblasts and leukocytes. An anti-vimentin MAb stained many cells in the dermis and few cells in the epidermis. Dual staining with the anti-vimentin MAb and polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum demonstrated that H. ducreyi was located in the subpustular dermis in 10 of 16 specimens (Fig. 2F). Only the samples with abundant H. ducreyi in the pustule also contained bacteria in the dermis. While some bacteria appeared to be associated with vimentin-containing structures, they were frequently found in the intercellular, unstained spaces (Fig. 2F).

To examine whether H. ducreyi was associated with keratinocytes at the pustular stage of disease, we doubly stained sections with a mixture of two anti-cytokeratin MAbs and with polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum. The mixture of anti-cytokeratin MAbs stains keratinocytes at all stages of differentiation. No bacteria were found associated with keratinocytes in these samples. Figure 2G shows an area in which the pustule borders keratinocyte layers in the epidermis. Bacteria were numerous within the pustule but were absent from the keratinocyte layers. As seen at higher magnification and stained additionally with TRITC-LCA, the bacteria associated mainly with the cells in the pustule and only rarely neared the edges of the keratinocytes (Fig. 2H).

Several specimens that had been inoculated with isogenic mutants from the parent/mutant trials were examined (Table 1). These mutants formed pustules that were clinically and histologically similar to disease caused by their isogenic parents (29a; Young et al., unpublished). The mutants localized to the pustule and dermis in a similar distribution to that of the parent strains.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we developed an assay to immunodetect H. ducreyi in vivo. We used this technique to localize H. ducreyi within specimens collected from the human model of H. ducreyi infection. The model is advantageous for localization studies in that it provides lesions from sites known to be inoculated with live H. ducreyi and no other ulcer-causing pathogens. Additionally, the lesions do not contain recoverable bacteria other than H. ducreyi. We found H. ducreyi in the pustule and dermis of lesions at the pustular stage of disease. We could not find H. ducreyi associated with keratinocytes in these lesions. To our knowledge, this represents the first localization study of chancroid in which the bacteria were specifically identified as H. ducreyi.

We examined lesions from sites inoculated with H. ducreyi during parent/mutant trials in human subjects. In addition to 10 sites inoculated with the parent strains 35000 or 35000HP, we examined 6 sites inoculated with isogenic mutants of H. ducreyi. These mutants caused disease that was similar to disease caused by the parent strains, and they localized to the same sites as the parents. We therefore considered the parent and mutant sites together in our analysis.

Immunodetection by confocal microscopy provided a sensitive and specific method of detection. The sensitivity was similar to that of culture, with only two discrepancies between the two detection methods in 19 lesions tested. These discrepancies may be explained by the nonuniform distribution of H. ducreyi observed within each specimen. This method also allowed us to immunologically identify bacteria in lesions as H. ducreyi. We concluded that the structures recognized by the polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum were H. ducreyi because (i) the polyclonal antiserum bound only to bacteria recognized by the H. ducreyi-specific MAb 5C9 and a panel of other MAbs that bind to H. ducreyi; (ii) the polyclonal antiserum did not bind to any structures in uninfected tissue, ruling out the possibility that the structures are part of healthy skin or members of the normal flora; and (iii) no bacteria other than H. ducreyi were recovered in nonselective cultures of the tissues, indicating that few, if any, bacteria other than H. ducreyi were present in these lesions. Additionally, the bacteria were consistent in size and morphology with H. ducreyi.

The dual staining experiments with the panel of MAbs that recognize H. ducreyi surface antigens also demonstrated in vivo expression of these surface proteins. We reported previously that FtpA is expressed in vivo (4); these studies extend those observations to include two outer membrane lipoproteins, PAL and Hlp (Table 2). MAbs recognizing epitopes common to MOMP and OmpA2 gave positive signals, indicating that one or both of these proteins are expressed in vivo. However, 3F12, which binds MOMP but not OmpA2, was nonreactive (Table 2). This could indicate that MOMP is not expressed or may simply mean that the epitope is occluded in vivo or in fixed sections.

H. ducreyi was found in the pustule and the dermis in these samples. In the pustule, bacteria were generally found associated with the surface of PMN, indicating that there may be a specific interaction with these cells. In contrast, bacteria in the dermis did not consistently associate with cellular structures, indicating they may be interacting with other dermal components such as extracellular matrix proteins. We are currently examining the interactions of H. ducreyi with PMN and extracellular matrix proteins in greater detail, including investigating whether the bacteria are intracellular.

One limitation of the model for localization studies is the artificial route of inoculation. The epidermis of upper-arm skin from five uninfected sites or sites inoculated with heat-killed H. ducreyi measured 0.03 to 0.145 mm (data not shown). The allergy-testing device penetrates the skin to a depth of 1.9 mm. The device, therefore, should deliver bacteria along its tines throughout the epidermis and upper dermis and into the deep dermis. The depth of the microabrasions required for H. ducreyi transmission is unknown. Thus, the device may or may not deliver bacteria to deeper sites than are required for normal transmission.

Other limitations of the human model of infection include the facts that we cannot infect volunteers past the pustular stage of disease and that we do not infect mucosal epithelium. However, chancroid readily occurs on stratified squamous epithelial surfaces, including the shaft of the penis, thighs, and buttocks. In a study conducted during a chancroid outbreak in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, 16 of 101 male and 10 of 34 female chancroid patients had lesions on nonmucosal surfaces (12). Additionally, extragenital infection does occur (12, 22). Therefore, localizing H. ducreyi in stratified squamous epithelium is relevant to naturally occurring disease. However, it should be emphasized that our findings are limited to the pustular stage of disease.

Given the number of studies reporting H. ducreyi adherence to keratinocytes in vitro, we were surprised that H. ducreyi did not associate with keratinocytes in vivo in our study. This observation, coupled with detection of the bacteria in the dermis, is consistent with reports that H. ducreyi cannot infect intact skin but requires some abrasion to initiate infection. Alternatively, keratinocyte involvement may occur at earlier or later stages of infection than the pustular stage examined here. These results could also be explained if bacteria are not initially exposed to keratinocytes by the artificial route of inoculation described above. However, preliminary analysis of tissue obtained by biopsy immediately after inoculation suggests that bacteria are being deposited in the epidermis and have access to keratinocytes (data not shown). Possibly, H. ducreyi does not bind to keratinocytes in vivo but binds to dermal targets to initiate infection.

In summary, we have developed a sensitive and specific method to localize H. ducreyi in vivo. Using this method with lesions obtained from the human model of infection, we showed that H. ducreyi localizes to the pustule and dermis at the pustular stage of disease. We do not know the relevance of this work to naturally occurring chancroid; however, the time course of disease and histology of the model resemble naturally occurring infection. We are currently localizing H. ducreyi in naturally occurring chancroidal ulcers and performing a longitudinal study to localize H. ducreyi at earlier stages of disease in the human model of H. ducreyi infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mike Apicella, Meg Ketterer, and Ruben Sandoval for many helpful suggestions and protocols for immunofluorescence staining procedures and for training on the use of the confocal microscope and imaging techniques. We thank Byron Batteiger, Antoinette Hood, and Robert Throm for helpful review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI27863 and AI31494 from the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). M.E.B. was supported by Public Health Service grant AI09971 from the NIAID. The clinical samples used in this study were obtained from clinical trials supported by the Sexually Transmitted Diseases Clinical Trials Unit, through contract NO1-AI75329 from the NIAID, and by Public Health Service grants AI40263, AI38444, and AI32011 from the NIAID.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abeck D, Johnson A P, Mensing H. Binding of Haemophilus ducreyi to extracellular matrix proteins. Microb Pathog. 1992;13:81–84. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90034-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfa M J, Degagne P, Hollyer T. Haemophilus ducreyi adheres to but does not invade cultured human foreskin cells. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1735–1742. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1735-1742.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Tawfiq J, Harezlak J, Katz B P, Spinola S M. Cumulative experience with Haemophilus ducreyi in the human model of experimental infection. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27:111–114. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200002000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Tawfiq, J. A., M. E. Bauer, K. R. Fortney, B. P. Katz, A. F. Hood, M. Ketterer, M. A. Apicella, and S. M. Spinola. A pilus-deficient mutant of Haemophilus ducreyi is virulent in the human model of experimental infection. J. Infect. Dis., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Al-Tawfiq, J. A., K. R. Fortney, B. P. Katz, C. Elkins, and S. M. Spinola. An isogenic hemoglobin receptor-deficient mutant of Haemophilus ducreyi is attenuated in the human model of experimental infection. J. Infect. Dis., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Al-Tawfiq J A, Thornton A C, Katz B P, Fortney K R, Todd K D, Hood A F, Spinola S M. Standardization of the experimental model of Haemophilus ducreyi infection in human subjects. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1684–1687. doi: 10.1086/314483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauer M E, Spinola S M. Binding of Haemophilus ducreyi to extracellular matrix proteins. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2649–2653. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2649-2652.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brentjens R J, Ketterer M, Apicella M A, Spinola S M. Fine tangled pili expressed by Haemophilus ducreyi are a novel class of pili. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:808–816. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.808-816.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brentjens R J, Spinola S M, Campagnari A A. Haemophilus ducreyi adheres to human keratinocytes. Microb Pathog. 1994;16:243–247. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleming D T, Wasserheit J N. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75:3–17. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freinkel A L. Histological aspects of sexually transmitted genital lesions. Histopathology. 1987;11:819–831. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1987.tb01885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammond G W, Slutchuk M, Scatliff J, Sherman E, Wilt J C, Ronald A R. Epidemiologic, clinical, laboratory, and therapeutic features of an urban outbreak of chancroid in North America. Rev Infect Dis. 1980;2:867–879. doi: 10.1093/clinids/2.6.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen E J, Loftus T A. Monoclonal antibodies reactive with all strains of Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1984;44:196–198. doi: 10.1128/iai.44.1.196-198.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heyman A, Beeson P B, Sheldon W H. Diagnosis of chancroid. JAMA. 1945;129:935–938. doi: 10.1001/jama.1945.02860480015004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiltke T J, Bauer M E, Klesney-Tait J, Hansen E J, Munson R S, Jr, Spinola S M. Effect of normal and immune sera on Haemophilus ducreyi 35000HP and its isogenic MOMP and LOS mutants. Microb Pathog. 1999;26:93–102. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1998.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiltke T J, Campagnari A A, Spinola S M. Characterization of a novel lipoprotein expressed by Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5047–5052. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5047-5052.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klesney-Tait J, Hiltke T J, Maciver I, Spinola S M, Radolf J D, Hansen E J. The major outer membrane protein of Haemophilus ducreyi consists of two OmpA homologs. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1764–1773. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1764-1773.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lagergard T, Purven M, Frisk A. Evidence of Haemophilus ducreyi adherence to and cytotoxin destruction of human epithelial cells. Microb Pathog. 1993;14:417–431. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1993.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lammel C J, Dekker N P, Palefsky J, Brooks G F. In vitro model of Haemophilus ducreyi adherence to and entry into eukaryotic cells of genital origin. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:642–650. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.3.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magro C M, Crowson A N, Alfa M, Nath A, Ronald A, Ndinya-Achola J O, Nasio J. A morphological study of penile chancroid lesions in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive and -negative African men with a hypothesis concerning the role of chancroid in HIV transmission. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:1066–1070. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90285-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marsch W C, Haas N, Stuttgen G. Ultrastructural detection of Haemophilus ducreyi in biopsies of chancroid. Arch Dermatol Res. 1978;263:153–157. doi: 10.1007/BF00446436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morse S A. Chancroid and Haemophilus ducreyi. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2:137–157. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ortiz-Zepeda C, Hernandez-Perez E, Marroquin-Burgos R. Gross and microscopic features in chancroid: a study in 200 new culture-proven cases in San Salvador. Sex Transm Dis. 1994;21:112–117. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199403000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmer K L, Schnizlein-Bick C T, Orazi A, John K, Chen C-Y, Hood A F, Spinola S M. The immune response to Haemophilus ducreyi resembles a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction throughout experimental infection of human subjects. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1688–1697. doi: 10.1086/314489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheldon W H, Heyman A. Studies on chancroid. I. Observations on the histology with an evaluation of biopsy as a diagnostic procedure. Am J Pathol. 1946;22:415–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spinola S M, Griffiths G E, Bogdan J A, Menegus M A. Characterization of an 18,000-molecular-weight outer membrane protein of Haemophilus ducreyi that contains a conserved surface-exposed epitope. Infect Immun. 1992;60:385–391. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.2.385-391.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spinola S M, Griffiths G E, Shanks K L, Blake M S. The major outer membrane protein of Haemophilus ducreyi is a member of the OmpA family of proteins. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1346–1351. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1346-1351.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spinola S M, Orazi A, Arno J N, Fortney K, Kotylo P, Chen C-Y, Campagnari A A, Hood A F. Haemophilus ducreyi elicits a cutaneous infiltrate of CD4 cells during experimental human infection. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:394–402. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spinola S M, Wild L M, Apicella M A, Gaspari A A, Campagnari A A. Experimental human infection with Haemophilus ducreyi. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1146–1150. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Throm, R. E., J. A. Al-Tawfig, K. R. Fortney, B. P. Katz, A. F. Hood, C. A. Slaughter, E. J. Hansen, and S. M. Spinola. Evaluation of an isogenic major outer membrane protein-deficient mutant in the human model of Haemophilus ducreyi infection. Infect. Immun., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Totten P A, Lara J C, Norn D V, Stamm W E. Haemophilus ducreyi attaches to and invades human epithelial cells in vitro. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5632–5640. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5632-5640.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young R S, Fortney K, Haley J C, Hood A F, Campagnari A A, Wang J, Bozue J A, Munson R S, Jr, Spinola S M. Expression of sialylated or paragloboside-like lipooligosaccharides are not required for pustule formation by Haemophilus ducreyi in human volunteers. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6335–6340. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6335-6340.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]