Abstract

Across countries in the world, China has the largest population of childhood cancer survivors. Research and care for the childhood cancer survivor population in China is fragmented. We searched studies published in English or Chinese language between January 1, 2000 and June 30, 2021, which examined various aspects of childhood cancer survivorship in China. The existing China‐focused studies were largely based on a single institution, convenient samplings with relatively small sample sizes, restricted geographic areas, cross‐sectional design, and focused on young survivors in their childhood or adolescence. These studies primarily focused on the physical late effects of cancer and its treatment, as well as the inferior psychological wellbeing among childhood cancer survivors, with few studies examining financial hardship, health promotion, and disease prevention, or healthcare delivery in survivorship. Our findings highlight the urgent need for research and evidence‐based survivorship care to serve the childhood cancer survivor population in China.

Keywords: childhood cancer, China, survivorship

This is the first overview of research over the past two decades that examined various aspects of childhood cancer survivorship in China, a country with the largest childhood cancer‐survivor population. We found that the existing China‐focused studies primarily focused on the physical late effects of cancer and its treatment, as well as the inferior psychological wellbeing among childhood cancer survivors, with no studies examining financial hardship, health promotion and disease prevention, or healthcare delivery during survivorship. Our findings highlight the urgent need for research and evidence‐based survivorship care to serve the growing childhood cancer‐survivor population in China.

1. INTRODUCTION

China has the largest child population (ages 0–19 years), accounting for 13% of all children in the world. 1 Cancer is a leading cause of death among children in China. 2 According to the World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer, 27,170 children ages 0–14 years and 9481 adolescents ages 15–19 years were diagnosed with cancer, and 10,553 children and 3574 adolescents died from cancer in China in 2020. 3 The 5‐year prevalent cancer cases among children ages 0–14 years and adolescents ages 15–19 years in China were 92,388 and 27,640, respectively, in 2020, accounting for 14% of the prevalent childhood cancer cases worldwide. 3 Similar to western countries, the most common cancer types among Chinese children and adolescents are leukemia, brain (central nervous system [CNS]), lymphoma, kidney, and liver cancer. 4

The event‐free survival and overall survival of childhood cancer, especially acute lymphoblastic leukemia, have increased in China. 5 , 6 The growing population of childhood cancer survivors resulted from improved survival highlights, the importance of cancer survivorship research in China. Importantly, compared to the U.S. and developed countries in Europe, the survival of childhood cancer patients in China remains inferior. 7 , 8 For example, the overall 5‐year relative survival rate for childhood cancer was 72% in 2000–2010 in China, 4 compared to 83% in 2003–2009 in the U.S. 9 Treatment delay, refusal, and abandonment were found to be contributing factors to the inferior childhood cancer survival in China, 8 , 10 with less data on healthcare delivery and health outcomes post treatment and during survivorship. While cancer survivorship care and research have been evolving in the western world over the past two decades, 11 the concept of cancer survivorship remains new in China, and related research has been fragmented.

To fill this knowledge gap, this study provides an overview of research addressing various aspects of survivorship for childhood cancer survivors in China in the scientific literature published in English or Chinese language. We also discussed implications for childhood cancer care delivery and avenues for future research. The study was deemed exempt by the Ethics Committee of the Center for Health Management and Policy Research at Shandong University prior to commencing this study.

2. DOMAINS OF CANCER SURVIVORSHIP

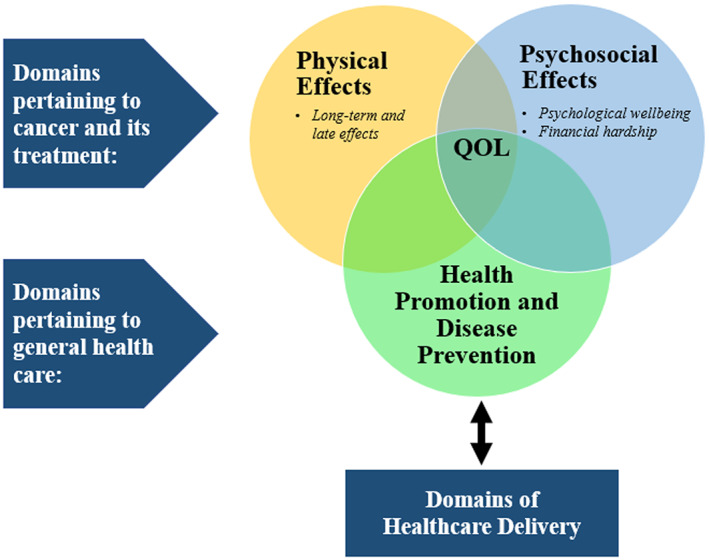

To conceptualize cancer survivorship, we focused on key domains adapted from the Cancer Survivorship Care Quality Framework by Nekhlyudov et al. 12

A major domain pertains to cancer and its treatment, including surveillance of physical sequelae—also called long‐term and late effects—and psychosocial effects of cancer diagnosis and treatment (Figure 1). Late effects (e.g., second cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and lung diseases) often last or occur months or years after cancer treatment is completed. 13 Indicators of psychosocial effects commonly include psychologic well‐being (e.g., distress) and financial hardship. 12 , 14 Financial hardship is often measured in three subdomains: material conditions, psychological responses, and coping behaviors. 15

FIGURE 1.

Domains of cancer survivorship. Notes. Adapted from the Cancer Survivorship Care Quality Framework by Nekhlyudov (2019). QOL, quality of life.

Another domain of cancer survivorship pertains to general health care, including health promotion and disease prevention. Indicators in this domain often include lifestyle behaviors (e.g., alcohol consumption) and preventive services use (e.g., vaccination). 12 Furthermore, cancer survivorship is also influenced by domains of healthcare delivery (e.g., survivorship care workforce, patient‐provider communication and decision‐making, and patients/caregivers experience). 12

All the domains described above ultimately impact survivors' health outcomes including quality of life (QOL). QOL is an individuals' perception of their position in life in the context of their culture and value systems and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns. 16 QOL is multidimensional, and children's QOL is often measured in the physical, emotional, psychological, and social domains.

We used domains derived from the Cancer Survivorship Care Quality Framework 12 as a guide to search and select literature (detailed in Appendix S1, S2) and synthesize findings from Chinese childhood cancer survivor populations. Below we presented highlights from studies published between January 1, 2000 and June 30, 2021 in English 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 or Chinese language 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 (Table 1, Appendix S3) to shed light on the gaps in previous literature and opportunities for future research.

TABLE 1.

Summary of articles on childhood cancer survivorship in China

| Survivorship outcome | Citation [Reference #] | Place | Study design | Sample size | Study follow‐up period | Age range at study/interview | Cancer type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English literatures | |||||||

| Long‐term and late effects of cancer treatment | Khalil 2019 17 | Shanghai | Hospital‐based retrospective cohort | 86 survivors | Median 7 years since diagnosis | median follow‐up 84 months (range 24–120 months) | Medulloblastoma |

| Cheung 2011 18 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based case–control | 36 survivors and 20 controls | 1+ years off treatment | 15.6 ± 5.5 yearsRange is not specified | Leukemia | |

| Yu 2013a 19 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based Case–control | 53 survivors and 38 controls | 1+ years off treatment | 18.6 ± 5.1 yearsRange is not specified | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acutemyeloid leukemia, osteosarcoma, Burkitt lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, non‐Hodgkin lymphoma,synovial sarcoma, neuroblastoma and hepatoblastoma | |

| Yu 2013b 20 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based Case–control | 32 survivors and 28 controls | 1+ years off treatment | 19.3 ± 5.4 yearsRange is not specified | Not specified | |

| Li 2019a 21 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based Case–control | 83 survivors and 42 controls | 5+ years off treatment | 15+ years | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Non‐Hodgkin lymphoma, Acute myeloid leukemia, Osteosarcoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, Wilm's tumor,Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor, Ewing Sarcoma, Hepatoblastoma | |

| Li 2019b 22 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based Case–control | 103 survivors and 61 controls | 5+ years off treatment | 25.6 ± 6.1 yearsRange is not specified | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma, Acute myeloid leukemia, Wilms' tumor,Hodgkin's lymphoma, Osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, Clear cell sarcoma of kidney, Ganglioneuroblastoma, Hepatoblastoma, Neuroblastoma, Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor | |

| Xie 2018 23 | Guangzhou, Guangdong Province | Hospital‐based retrospective cohort | 90 survivors | 2.6–9.6 years after diagnosis; off treatment | Not specified | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | |

| Lu 2019 24 | Guangzhou, Guangdong Province | Hospital‐based retrospective cohort | 94 survivors | 5–27 years (median 10 years) after completion of treatment | < 18 years | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | |

| Chung 2014 25 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 128 survivors | 6+ months after completion of treatment | 9–16 years | Leukemia, Lymphoma, Brain tumor, Osteosarcomas, Kidney tumor, Germ‐cell tumor | |

| Peng 2021 26 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 152 survivors | 2+ years off treatment | 23.5 ± 7.2 years | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | |

| Yang 2021a 27 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 200 survivors | 10+ years off treatment | Adult survivors: 26.9 ± 6.4 years;pediatric survivors: 11.1 ± 3.6 years | Hematological malignancy, Leukemia, Lymphomas, CNS tumor, Neuroblastoma Retinoblastoma, Renal tumor, Hepatic tumor, Bone tumor, Soft tissue sarcomas, Germ cell tumor, Others | |

| Psychological wellbeing | Ng 2019 35 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 200 Survivors | 3+ years off treatment | 25.4 ± 5.57 years | hematological cancer, acute lymphoid leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, Wilm's tumor, osteosarcoma, neuroblastoma and others |

| Yuen 2014 28 | Hong Kong | Non‐Government Organization‐based cross‐sectional | 89 survivors | In remission | 17.2–31.3 years | Not specified | |

| Li 2013 29 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 137 survivors and 245 controls | 6+ months after completion of treatment | 9 to 16 years | Leukemia, Lymphoma, Brain tumor, Osteosarcoma,Kidney tumor, Germ cell tumor | |

| Psychological wellbeing and quality of life | Cheung 2019a 31 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 157 survivors | 2+ months after completion of treatment | 7 to 16 years | Brain cancer and other cancers |

| Chan 2014 33 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 614 survivors and 208 sibling controls | 2+ y off treatment | 16 to 39 years | Leukemia, Lymphoma, Bone and soft tissue cancers,Brain and CNS malignancies, and Others | |

| Cheung 2019b 32 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based randomized trial | 60 survivors | 2+ months after completion of treatment | 7–16 yMean = 12.53 (3.18) for experimental group;mean = 13.97 (3.26) for control group | Brain tumors | |

| Li 2018 36 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based randomized trial | 222 survivors | 6+ after completion of treatment | 9–16 years | Leukemia, Lymphoma, Brain tumor, Bone tumor, Neuroblastoma | |

| Quality of life | Chung 2012 37 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 153 survivors | 6+ months after completion of treatment | 9–16 years | Leukemia, Lymphoma, Brain tumor, Osteosarcoma,Kidney tumor, Germ cell tumor |

| Zhang 2018 38 | Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 71 survivors and80 controls | 1+ years after treatment | 5 to 8 years | Etinoblastoma (RB) | |

| Ho 2019 39 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 400 survivors | 6+ after completion of treatment | 7–18 years | Leukemia, Lymphoma, Brain tumor, Osteosarcoma,Kidney tumor, Germ cell tumor | |

| Yang 2021b 41 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 80 survivors | off treatment and 5+ years after diagnosis | 24.4 ± 6.5 years | Leukemia, Brain & CNS tumor, and other solid tumors (refers to germ cell tumor, osteosarcoma, soft tissue sarcoma, and lymphoma) | |

| Health promotion, psychological wellbeing and quality of life | Chan 2020 34 | Hong Kong | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 614 survivors and 208 sibling controls | 2+ y off treatment | 24.0 ± 5.1 years | Leukemia, Lymphoma, bone and soft tissue cancers,Brain and CNS malignancies, and Others |

| Health promotion and quality of life | Zheng 2021 42 | Guangzhou, Guangdong Province | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 181 survivors | Off treatment and 2+ years after diagnosis | 4–18 years | Leukemia, lymphoma, solid tumors |

| Quality of life and Caregiver wellbeing | Wang 2017 40 | Chengdu, Sichuan Province | Hospital‐based Case–control | 217 survivors and95 controls | Currently not receiving treatment | 0–2 years | Infantile hemangioma |

| Chinese literatures | |||||||

| Long‐term and late effects of cancer treatment | Jiang 2000 43 | Shanghai | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 31 survivors | 3–14 years off treatment | 10–20 years | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| Chen 2000 44 | Shanghai | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 22 survivors | 4–8.5 years (median 4 year 10 months) after remission | 8–16 years | Acute leukemia | |

| Zhou 2006 47 | Suzhou, Jiangsu Province | Hospital‐based Case–control | 30 survivors and 30 controls | 3+ years after remission | 6–34 years | Acute leukemia | |

| Zhao 2012 46 | Beijing | Hospital‐based Case–control | 70 survivors and 36 controls | Median 64.3 months (15–131 months) since diagnosis | 0.7–14.7 (median 4.5) years | Acute leukemia | |

| Fu 2017 45 | Shanghai | Hospital‐based Case–control | 40 survivors and 40 controls | 5+ years after remission | 7–15 years | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | |

| Zhang 2001 48 | Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 35 survivors | 6–16 years after remission | 8–28 years | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | |

| Psychological wellbeing | Wang 2009a 53 | Jinan, Shandong Province | Hospital‐based Case–control | 19 survivors and 40 controls | 5+ years after remission | 7–16 years | Leukemia |

| Wang 2010a 50 | Jinan, Shandong Province | Hospital‐based Case–control | 20 survivors and 50 controls | 5+ years after remission | 7–16 years | Leukemia | |

| Wang 2010b 51 | Jinan, Shandong Province | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 20 survivors and 30 controls | 5+ years after remission | 7–16 years | Leukemia | |

| Wang 2011 52 | Jinan, Shandong Province | Hospital‐based Case–control | 20 survivors and 50 controls | 5+ years after remission | 7–16 years | Acute leukemia | |

| Sun 2006 54 | Suzhou, Jiangsu Province | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 27 survivors | 3+ years after remission | 7–19 years | Acute leukemia | |

| Li 2021 55 | Beijing | Hospital‐based cross‐sectional | 106 survivors | After remission | 12–28 years | Leukemia | |

| Quality of life | Fan 2007 56 | Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province | Hospital‐based Case–control | 140 survivors and 80 controls | 1+ years after remission | 9–16 years | Lymphoma |

| Liu 2018 57 | Chongqing | Hospital‐based Case–control | 307 survivors | After remission | 2–18 years | Leukemia | |

| Caregiver wellbeing | Wang 2007 58 | Beijing | Hospital‐based Case–control | 68 survivors and 122 controls | After remission | 4–16 years | Leukemia |

| Wang 2009b 49 | Jinan, Shandong Province | Hospital‐based Case–control | 19 survivors and 40 controls | 2–13 years (mean 5.26 years) off treatment | 7–16 years | Acute leukemia | |

| Wang 2010a 50 | Jinan, Shandong Province | Hospital‐based Case–control | 20 survivors and 50 controls | 5+ years after remission | 7–16 years | Leukemia | |

| Fu 2016 59 | Haikou, Hainan Province | Hospital‐based Case–control | 106 survivors | Median 4+ years after remission | Not specified | Leukemia | |

3. RESEARCH ADDRESSING PHYSICAL LATE EFFECTS OF CANCER TREATMENT

Eleven studies published in English language and six studies published in Chinese examined the physical late effects of cancer treatment among childhood cancer survivors in China (Table 1).

We identified several studies conducted in Hong Kong, which reported cardiotoxic side effects of anthracycline chemotherapy among childhood cancer survivors who were off treatment for ≥1 year. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 Yu et al performed a Hong Kong‐based study of 53 adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer, and demonstrated the impairment of global and regional myocardial deformation in three dimensions, reduced torsion, and systolic dyssynchrony after anthracycline therapy. 19 In another Hong Kong‐based study focusing on 32 anthracycline‐treated survivors of childhood cancer, the same research team found reductions in left ventricular transmural circumferential strain and apical rotation gradients in survivors. 20 In a similar study in Hong Kong, Cheung et al reported the impairment of left ventricular twisting and untwisting motion after anthracycline therapy in a cohort of 36 childhood survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). 18 In two recent Hong Kong‐based studies, Li et al investigated cohorts of 83 and 103 survivors of childhood cancer who had been off therapy for ≥5 years, and demonstrated low myocardial strain indices at imaging, abnormal left ventricular and right ventricular systolic functional reserve, and impairment of left ventricular diastolic functional reserve. 21 , 22 A more recent study in Hong Kong followed 152 young survivors of childhood ALL who were treated with chemotherapy and ≥2 years off treatment; this study found that, while the majority of the survivors had a normal cognitive and behavioral function, the impairments were higher than population norms. This study also found that chronic conditions developed after the cancer treatments were associated with multiple measures of behavior problems, such as executive dysfunction and attention problems. 26 Although long‐term and late effects of cancer treatment are common among childhood cancer survivors, another study in Hong Kong found that, among 200 survivors at least 10 years post‐treatment, most were not able to accurately identify the late effects that they were at risk for, 27 suggesting that improvements in health literacy of late effects are warranted among childhood cancer survivors.

We also identified several studies conducted in mainland China, which examined physical late effects among childhood cancer survivors. Several of these studies examined late effects associated with chemotherapy received by children diagnosed with acute leukemia (Table 1). 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 A range of 22–70 children from Suzhou, Wenzhou, Shanghai, or Beijing who were several years off treatment or after remission were included in the studies. These studies generally did not find evidence of late effects on growth, development, or endocrine function; however, a reduction in intelligence quotient was reported in two of the studies in Shanghai. 44 , 45 In addition, two studies in mainland China examined radiotherapy‐induced toxicity and late sequelae of complications. In a study examining 90 children diagnosed with nasopharyngeal carcinoma and treated at a cancer center in Guangzhou, Xie et al followed survivors for 2.6–9.6 years after their receipt of radiotherapy; they found that survivors had decreased pituitary heights and stunted linear growth. 23 In another Guangzhou‐based study, Lu et al identified 94 survivors of childhood and adolescent nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with radiotherapy and followed survivors for a median of 10 years. 24 This study showed the presence of grade 1 and 2 complications (such as xerostomia, hearing loss, and neck fibrosis; graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0) in most survivors who received radiotherapy. 24 This study also reported that the top 10 common long‐term sequela of radiotherapy included xerostomia, hearing loss, neck fibrosis, trismus, caries, dysphagia, impaired memory, tinnitus, lalopathy, and chronic otitis media, with a higher radiation dose associated with higher incidence of severe late sequelae. 24 Lastly, in a Shanghai‐based study following 121 childhood medulloblastoma survivors treated with surgery, radiotherapy, and/or chemotherapy, Khalil et al reported growth suppression in 41.3% survivors, hearing loss in 24% survivors, visual disturbance in 15.7% survivors, neurologic toxicity (including poor concentration, poor memory, and learning difficulties) in 25% survivors, and secondary malignancy in 3.5% survivors. 17

4. RESEARCH ADDRESSING PSYCHOLOGICAL WELLBEING

Eight studies published in English language and six studies in Chinese investigated psychological well‐being of childhood cancer survivors in China (Table 1).

The English articles identified in this domain were all based in Hong Kong. 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 36 Using a convenient sample in an oncology clinic in Hongkong, Li et al interviewed 137 childhood cancer survivors ≥6 months after treatment completion (73% within 2 years post‐treatment). 29 The study showed that childhood cancer survivors had higher risk for depressive symptoms and lower levels of self‐esteem, compared with peers without a cancer history. 29 In a recent study of 77 childhood brain tumor survivors and 80 survivors of other childhood cancers, Li et al reported that brain tumor survivors had the poorest psychological outcomes, assessed by the number of depressive symptoms and the level of self‐esteem. 31 In contrast, using convenient samples of 614 childhood cancer survivors who were off treatment for ≥2 years and 208 sibling controls, Chan et al found no difference in mental, social, or psychological wellbeing between survivors and their siblings. 33 Using the same study subjects, Chan et al also found that unhealthy behaviors such as alcohol drinking and lacking cancer screenings were associated with higher psychological distress among survivors. 34 In a study examining adult survivors of childhood cancers with original tumors not hormone‐dependent, Ng et al examined sexual function, an integral part of both physical and psychosocial wellbeing, and found that 24% survivors reported sexual functioning problems. 35 They also found that survivors with non‐hematological cancers, those treated with surgery, and those with lower health‐related quality of life, lower self‐esteem, and higher levels of body image distress and depression symptoms were more likely to report sexual functioning problems. 35

Psychological wellbeing of childhood cancer survivors has also been studied in mainland China. In a line of research conducted in Jinan, Shandong Province, Wang et al interviewed 20 child survivors of leukemia who were ≥5 years after remission and compared their psychological constructs with healthy children (Table 1). 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 They found that survivors had higher scores on somatization/panic, generalized anxiety, and social phobia and lower scores on self‐concept and happiness, compared with healthy controls, and survivors' psychological scores were correlated with parents' anxiety scores. 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 In another study of 27 child survivors of acute leukemia who were ≥3 years after remission in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, Sun et al reported a high prevalence of learning anxiety (85.7%), a tendency toward being oversensitive and self‐blaming (21.4%), and a tendency toward isolation (7.1%) (Table 1). 54 A recent study of 106 adolescent leukemia survivors in Beijing showed that disease risk, duration of drug withdrawal, and general self‐efficacy were the contributing factors of psychological resilience. 55 Notably, we only identified one study investigating effective intervention strategies toward improving psychosocial outcomes of childhood cancer survivors. 32

5. RESEARCH ADDRESSING QUALITY OF LIFE

Twelve studies published in English language and two studies published in Chinese examined QOL of childhood cancer survivors in China (Table 1).

Studies focusing on QOL of childhood cancer survivors were largely conducted in Hong Kong. In a telephone survey of historical patients treated in three Hong Kong hospitals who were ≥2 years off treatment, young adult survivors (aged 16–39 years) of childhood cancer had inferior health‐related quality of life (HRQOL) compared to their siblings in the physical health components. 33 Among the survivors, older age, female gender, receipt of multiple treatments, and cancers of bone, soft tissue, and CNS cancer were associated with poorer HRQOL. 33 In another series of studies, childhood cancer survivors aged 7–18 years who had completed cancer treatment for at least several months were interviewed in an outpatient clinic setting in Hong Kong. 30 , 31 , 37 , 39 These studies showed that greater symptoms of depression, greater occurrence and severity of fatigue, and a diagnosis of brain tumor were associated with poorer QOL. Another study in Hong Kong showed that alcohol drinking was associated with poorer QOL among young adult survivors of childhood cancers. 34 In two recent randomized controlled trials conducted among Hong Kong children who had completed cancer treatment for at least several months, a one‐year music training program 32 and a 4‐day per week adventure program 36 effectively enhanced QOL for brain tumor survivors and survivors with fatigue symptoms, respectively. One recent study of young adult survivors of childhood cancers in Hong Kong examined life functioning, which is often considered a dimension of QOL, 60 and found that brain tumor survivors and those treated with cranial radiation performed worse in social functioning and worker life functioning. 41

In mainland China, studies on QOL of childhood cancer survivors have been sparse until recently. A Hangzhou‐based study followed childhood retinoblastoma survivors aged 5–8 years seen in an eye center, and showed that survivors' QOL were significantly lower than those of healthy children controls, especially in the dimensions of social and school functioning. 38 The study further showed that bilateral eye disease, earlier age at diagnosis, and low degree of satisfaction with the artificial eyes were associated with worse QOL among survivors. 38 A study conducted at the department of pediatric surgery in a hospital in Chengdu found that children with infantile hemangioma (<2 years off‐treatment) had comparable QOL with healthy controls in all functioning dimensions, except for physical symptoms. 40 Among survivors, hemangioma size, tumor location, children's age, and parents' education level influenced QOL. 40 A more recent study in Guangzhou found that physical and psychosocial domains of QOL in childhood cancer survivors were lower than the norm score assessed in healthy children. 42 Additionally, pick‐eating was associated with lower QOL, and moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity was associated with higher QOL among childhood cancer survivors. 42

Only two eligible studies on QOL of childhood cancer survivors off treatment were identified in the literature published in Chinese language, where QOL of 140 child survivors of lymphoma and 80 healthy controls in Zhanjiang and Shenzhen were included. 56 One study showed that compared with healthy controls, survivors 1‐year post‐remission had worse scores in the domains of role function, social function, economic status, and general health; additionally, survivors 5‐year post‐remission still had worse scores in social function and general health. Another study from Chongqing explored the effect of continuous nursing based on short distance communication mode on the QOL of 307 children with leukemia, and this mode effectively reduced the incidence of infection and improved the quality of life in these survivors. 57

6. RESEARCH ADDRESSING HEALTH PROMOTION

We identified two studies in English that examined health promotion among childhood cancer survivors in China (Table 1).

Using survey among 614 survivors and 208 sibling controls in Hong Kong, Chan et al found that survivors were less likely to drink alcohol and to have pap smear tests or breast examinations compared to their siblings. 34 Another study led by Zheng was conducted in Guangzhou, one of the major cities insouthernh mainland China, and found that few Chinese cancer survivors engaged in unhealthy dietary behaviors, such as frequent soft drinks and fast food consumptions; however, many of them were picky eaters and did not meet milk intake and physical activity recommendations. 42 Both studies found a link between unhealthy behaviors and worse QOL. 34 , 42

7. RESEARCH ADDRESSING CAREGIVER WELLBEING

We identified one study in English and four studies in Chinese that examined caregivers' well‐being post cancer treatment in China; all these studies were conducted in mainland China (Table 1).

In a study conducted in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, QOL of parents of 237 children with infantile hemangioma was correlated with mother's education level and patients' QOL. 40 In another study comparing families of 68 children in remission after treatment of leukemia in 4 tertiary hospitals in Beijing with 122 healthy children, Wang et al found that families with a survivor had higher family cohesion and adaptability but less balanced family type. 58 Additionally, in a study including 202 parents of 106 leukemia children in Haikou, Hainan Province, intensive health education reduced the degree of anxiety among parents in the observation group, compared with those receiving routine health education in the control group. 59 Lastly, in two studies in Jinan, Shandong Province, parents of 19 and 20 children with leukemia who were ≥5 years after remission reported higher depression and anxiety scores, compared with parents of 40 and 50 healthy children, respectively. 49 , 50

8. RESEARCH ADDRESSING FINANCIAL HARDSHIP

Despite a thorough search of the literature, we did not find any study conducted in China focusing on the financial hardship of childhood cancer survivors and families in the post‐treatment period. Notably, there were five studies published in Chinese language that estimated care costs associated with cancer treatment among patients actively receiving cancer therapies. 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 As costly cancer therapy is a strong driver of financial hardship during survivorship, we summarized the cost estimation in these studies in Appendix S4.

9. DISCUSSION

In this overview of research addressing childhood cancer survivorship in China, we found that previous literature primarily focused on physical sequelae of cancer therapy. Common physical late effects identified among childhood cancer survivors in China included cardiovascular diseases, second cancers, neurological and cognitive problems, and growth and hormone problems, with wide variation by treatment modality and cancer type. 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 44 , 45 A handful of studies explored the psychosocial effects of cancer therapy among childhood cancer survivors in China, where depression, anxiety, psychological distress, low self‐esteem, and behavioral problems were found to be common psychological problems. 28 , 29 , 30 , 33 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 Childhood cancer survivors often experienced elevated rates of psychological problems and poorer QOL compared with healthy counterparts, with the magnitude of the difference varying by cancer type, age at diagnosis, and dimensions of outcome measures. Among survivors, adverse psychosocial outcomes were correlated with survivors' demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender), clinical factors (e.g., cancer type, survival time, treatment modalities), lifestyle factors (e.g., physical activity), and parental factors. 29 , 33 , 37

These findings highlight several gaps in the existing literature and opportunities to further study childhood cancer survivorship in the Chinese population. According to the Cancer Survivorship Care Quality Framework, 12 prior studies have exclusively focused on domains pertaining to cancer and its treatment. Notably, these studies were largely based on a single institution, cross‐sectional design, convenient samplings with relatively small sample sizes, and restricted geographic area (i.e., Hong Kong or economically developed metropolitan cities of mainland China), potentially limiting the generalizability of findings. Further, very few studies had long‐term follow‐up after survivors completed cancer therapy; the median follow‐up time was less than a decade. Consequently, most studies focused on young survivors in their childhood or adolescence. Additionally, evidence on intervention strategies that improve long‐term physical and psychosocial sequelae of cancer and its treatment is sparse. These are also common limitations in the existing studies focusing on childhood cancer survivorship in other resource‐limited countries. 66 , 67 Together, future population‐based studies that allow longitudinal follow‐up of long‐term survivors of childhood cancer and new initiatives that enhance data infrastructure are needed in China to advance understanding of long‐term consequences of childhood cancer and its treatment, and to inform interventions toward prevention and early detection of late effects.

The well‐being and health of caregivers has been an active area of research in western countries; 68 however, relevant data are lacking in China. Only four studies based in China examined caregivers of childhood cancer survivors, and generally found deteriorating mental health or family function problems of parents taking care of a child survivor; 40 , 49 , 50 , 58 yet, few examined caregivers' QOL nor the risk factors of their health and well‐being. Thus, more analyses are needed to assess various outcome domains, particularly QOL, among survivors' caregivers in China, and to identify effective interventions toward improving caregivers' health and well‐being. Several China‐based studies have explored effective strategies while children were under treatment, including tailored nursing models, mutual help groups for parents, or mHealth supportive care intervention, 69 , 70 , 71 to buffer the effect of cancer diagnosis and treatment on their caregivers. These strategies could potentially be applied to caregivers of survivors off treatment.

With rising costs of cancer care, medical financial hardship and the consequent non‐medical financial sacrifices have become a major concern for survivors and families. 15 , 72 , 73 To date, however, no studies have examined the financial hardship of long‐term survivors of childhood cancers and their families in China. In the existing studies focusing on costs of cancer treatments the and financial burden on families with a child actively receiving therapies, all used relatively small samples of leukemia children from a single hospital, with wide variation and limited generalizability (Appendix S4). In the U.S. and European countries, a series of studies—based on longitudinal follow‐up of 5‐year survivors or national survey databases—have shown an elevated risk for facing high out‐of‐pocket medical expenses, having difficulties with obtaining health insurance and paying medical bills, considering filing for bankruptcy, and lacking the ability to work among adult survivors of childhood cancer as compared to siblings or healthy controls. 74 , 75 It is critical to extend this research to China. Notably, when studying financial hardship for the growing population of childhood cancer survivors and their families in China, unique challenges stemming from the healthcare system in the country should be considered. Particularly, despite the recently achieved “universal health coverage” in China, out‐of‐pocket expenses still account for nearly 40% of total medical expenses. 76 In addition, pediatric oncology care resources are concentrated only in a few metropolitan cities, leading to considerable costs associated with transportation and lodging for survivors residing in other areas.

There are only two recent studies in China on health promotion or disease prevention among survivors off childhood cancer treatment, an important area that merits future research. Relevant research topics would include assessment of lifestyle behaviors (e.g., smoking, alcohol use, illicit drug use, and physical activity), vaccination, and adherence to surveillance for late effects, which are vital indicators for cancer survivorship quality. 12 Data from western countries have demonstrated that young cancer survivors are often inactive, 77 continue to smoke, 78 and have higher rates of alcohol use 79 and less HPV vaccine initiation than those without cancer. 80 Such vulnerabilities may be exacerbated among survivors in China, where smoking and harmful drinking behaviors are highly prevalent, 81 and the fee‐for‐service delivery system often incentivizes treatments over preventive care; 82 but this question has yet to be explored in the country.

Importantly, we are not aware of any study based in China that examine access to and delivery of survivorship care. This finding may be explained, at least partially, by the fact that in China, survivorship care has not been fully accepted as standard care for cancer survivors. 83 As recognized in an expert survey of a panel of Chinese Children Cancer Group, there are major barriers to implementing survivorship programs, including unawareness of the health issues related to cancer therapy and concerns about privacy issues in survivors and families, as well as a lack of support and resources to provide follow‐up care for clinicians. 84 Furthermore, in North American countries, risk‐based survivorship care is recommended for all childhood cancer survivors, 85 and evidence‐based guidelines have been developed for the surveillance of late and long‐term effects. 86 , 87 However, in China, a lack of standardized guidance for monitoring late effects in survivors is another barrier to implementing cancer survivorship programs. 84 To inform survivorship care practice in China, more China‐based studies are urgently needed to understand childhood cancer survivors' needs—including their awareness of potential long‐term health issues and risks—and Chinese pediatric oncologists' perceptions about the barriers and facilitators to implementing survivorship care. This line of future research will be a critical step toward developing survivorship care models that are practical and acceptable in China's unique historical and cultural context.

This is the very first, comprehensive overview of childhood cancer survivorship in the Chinese population on the basis of the scientific literature in English or Chinese languages. Our findings highlight the urgent need for research to address the gaps in knowledge about childhood cancer survivorship in China, and to develop evidence‐based consensus and guidelines for survivorship care practice and delivery, in order to meet the complex physical and psychosocial needs of the large and growing childhood cancer survivor population in the country.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Xu Ji, Xiaojie Sun, and Xuesong Han: Conceptualization, visualization, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review, and editing. Jun Sun, Xinyu Liu, Ziling Mao, Wenjing Zhang, and Jinhe Zhang: Methodology, literature review and organization, writing—review, and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supporting information

Appendix

Ji X, Su J, Liu X, et al. Childhood cancer survivorship in China: An overview of the past two decades. Cancer Med. 2022;11:4588‐4601. doi: 10.1002/cam4.4831

Funding information

Dr. Xiaojie Sun is supported by the Shandong University Multidisciplinary Research and Innovation Team of Young Scholars (2020QNQT019).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. The World Bank . Data: population ages 0–14, total. Accessed September 25, 2020. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.0014.TO

- 2. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation . Global health data exchange. Accessed September 25, 2020. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd‐results‐tool

- 3. International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization . Cancer today. Accessed September 25, 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/online‐analysis‐table

- 4. Zheng R, Peng X, Zeng H, et al. Incidence, mortality and survival of childhood cancer in China during 2000‐2010 period: a population‐based study. Cancer Lett. 2015;363(2):176‐180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen SL, Zhang H, Gale RP, et al. Toward the cure of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children in China. JCO Glob Oncol. 2021;7:1176‐1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cui L, Li ZG, Chai YH, et al. Outcome of children with newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with CCLG‐ALL 2008: the first nation‐wide prospective multicenter study in China. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(7):913‐920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bonaventure A, Harewood R, Stiller CA, et al. Worldwide comparison of survival from childhood leukaemia for 1995‐2009, by subtype, age, and sex (CONCORD‐2): a population‐based study of individual data for 89 828 children from 198 registries in 53 countries. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(5):e202‐e217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bao PP, Zheng Y, Wu CX, et al. Population‐based survival for childhood cancer patients diagnosed during 2002‐2005 in Shanghai. China Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59(4):657‐661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):83‐103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang YR, Jin RM, Xu JW, Zhang ZQ. A report about treatment refusal and abandonment in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in China, 1997‐2007. Leuk Res. 2011;35(12):1628‐1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yabroff KR, Zheng Z, Han X. Cancer survivorship. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1380‐1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nekhlyudov L, Mollica MA, Jacobsen PB, Mayer DK, Shulman LN, Geiger AM. Developing a quality of cancer survivorship care framework: implications for clinical care, research, and policy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(11):1120‐1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572‐1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ji X, Cummings JR, Gilleland Marchak J, Han X, Mertens AC. Mental health among nonelderly adult cancer survivors: a national estimate. Cancer. 2020;126(16):3768‐3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker‐Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(2):djw205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(10):1403‐1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khalil J, Qing Z, Chuanying Z, Belkacemi Y, Benjaafar N, Mawei J. Twenty years experience in treating childhood medulloblastoma: between the past and the present. Cancer Radiother. 2019;23(3):179‐187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cheung YF, Li SN, Chan GC, Wong SJ, Ha SY. Left ventricular twisting and untwisting motion in childhood cancer survivors. Echocardiography. 2011;28(7):738‐745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yu HK, Yu W, Cheuk DK, Wong SJ, Chan GC, Cheung YF. New three‐dimensional speckle‐tracking echocardiography identifies global impairment of left ventricular mechanics with a high sensitivity in childhood cancer survivors. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26(8):846‐852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yu W, Li SN, Chan GC, Ha SY, Wong SJ, Cheung YF. Transmural strain and rotation gradient in survivors of childhood cancers. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14(2):175‐182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li VW, Liu AP, So EK, et al. Two‐ and three‐dimensional myocardial strain imaging in the interrogation of sex differences in cardiac mechanics of long‐term survivors of childhood cancers. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;35(6):999‐1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li VWY, Liu APY, Wong WHS, et al. Left and right ventricular systolic and diastolic functional reserves are impaired in anthracycline‐treated long‐term survivors of childhood cancers. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2019;32(2):277‐285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xie C, Li J, Weng Z, et al. Decreased pituitary height and stunted linear growth after radiotherapy in survivors of childhood nasopharyngeal carcinoma cases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lu S, Wei J, Sun F, et al. Late sequelae of childhood and adolescent nasopharyngeal carcinoma survivors after radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;103(1):45‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chung OK, Li HC, Chiu SY, Ho KY, Lopez V. The impact of cancer and its treatment on physical activity levels and behavior in Hong Kong Chinese childhood cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2014;37(3):E43‐E51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Peng L, Yang LS, Yam P, et al. Neurocognitive and behavioral outcomes of Chinese survivors of childhood lymphoblastic leukemia. Front Oncol. 2021;11:655669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yang LS, Ma CT, Chan CH, et al. Awareness of diagnosis, treatment and risk of late effects in Chinese survivors of childhood cancer in Hong Kong. Health Expect. 2021;24(4):1473‐1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yuen AN, Ho SM, Chan CK. The mediating roles of cancer‐related rumination in the relationship between dispositional hope and psychological outcomes among childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2014;23(4):412‐419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li HC, Lopez V, Joyce Chung OK, Ho KY, Chiu SY. The impact of cancer on the physical, psychological and social well‐being of childhood cancer survivors. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17(2):214‐219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li HC, Chung OK, Ho KY, Chiu SY, Lopez V. A descriptive study of the psychosocial well‐being and quality of life of childhood cancer survivors in Hong Kong. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35(6):447‐455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cheung AT, Li WHC, Ho LLK, et al. Impact of brain tumor and its treatment on the physical and psychological well‐being, and quality of life amongst pediatric brain tumor survivors. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2019;41:104‐109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cheung AT, Li WHC, Ho KY, et al. Efficacy of musical training on psychological outcomes and quality of life in Chinese pediatric brain tumor survivors. Psychooncology. 2019;28(1):174‐180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chan CW, Choi KC, Chien WT, et al. Health‐related quality‐of‐life and psychological distress of young adult survivors of childhood cancer in Hong Kong. Psychooncology. 2014;23(2):229‐236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chan CWH, Choi KC, Chien WT, et al. Health behaviors of Chinese childhood cancer survivors: a comparison study with their siblings. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(17):6136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ng CF, Hong CYL, Lau BSY, et al. Sexual function, self‐esteem, and general well‐being in Chinese adult survivors of childhood cancers: a cross‐sectional survey. Hong Kong Med J. 2019;25(5):372‐381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li WHC, Ho KY, Lam KKW, et al. Adventure‐based training to promote physical activity and reduce fatigue among childhood cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;83:65‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chung OK, Li HC, Chiu SY, Lopez V. Predisposing factors to the quality of life of childhood cancer survivors. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2012;29(4):211‐220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang L, Gao T, Shen Y. Quality of life in children with retinoblastoma after enucleation in China. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(7):e27024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ho KY, Li WHC, Lam KWK, et al. Relationships among fatigue, physical activity, depressive symptoms, and quality of life in Chinese children and adolescents surviving cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2019;38:21‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang C, Li Y, Xiang B, et al. Quality of life in children with infantile hemangioma: a case control study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yang H, Fong S, Chan P, et al. Life functioning in Chinese survivors of childhood cancer in Hong Kong. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2021;10(3):326‐335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zheng J, Zhou X, Cai R, Yu R, Tang D, Liu K. Dietary behaviours, physical activity and quality of life among childhood cancer survivors in mainland China: a cross‐sectional study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2021;30(1):e13342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jiang H, Lu Z, Jing H. Quality of life in 31 patients with acute leukemia after drug withdrawal. Chin J Pediatr. 2000;16(12):772. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen J, Gu L, Yao H. Evaluation of long‐term disease‐free quality of life in 22 children with acute leukemia. Chin J Pediatr. 2000;38(2):111‐112. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fu X, Xie X, Zhao Y. Neurocognitive function of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and long‐term disease‐free survival and related influencing factors. Chin J Contemp Pediatr. 2017;19(8):899‐903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhao W, Hua Y, Lu X, Sun G, Li Q, Yu Z. Analysis of follow ‐ up of therapeutic effectiveness in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia J Appl Clin Pediatr 2012(3):192‐193,202. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhou J, Chai Y. Analysis of growth and development and endocrinosity in 30 acute leukemic children of long‐term disease‐free survival. J China Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;11(5):248‐251. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang J, Ruan J, Li Y, Shen S, Wang H. A survey of the long‐term survival quality for children with acute lymphocytic leukemia. J Wenzhou Med College. 2001;31(4):232‐233. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang H, Chen L, Chen W, Ren W. A controlled study on the psychological characteristics of children with leukemia and their parents. Chin J Pract Pediatr. 2009;24(10):791‐794. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wang H, Chen L, Gao F, Ren W, Chen W. Study on the psychological characteristics of children with leukemia and their parents. J China Pediatr Blood Cancer 2010;15(4):152–156,166. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang H, Ren W, Zhang Y, Chen L. A controlled study on the psychological characteristics of long‐term survivors of childhood leukemia and newly diagnosed leukemia patients. J Clin Pediatr. 2010;28(5):433‐437. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang H, Zhang Y, Chen W, et al. Effects of parental anxiety and depression on the feelings and self‐concept of children with leukemia. Cancer Res Clin. 2011;23(7):483‐486. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wang H, He S, Chen L, Chen W, Ren W. A controlled study on the psychological characteristics of long‐term survivors of childhood leukemia. Chin J Behav Med Brain Sci. 2009;18(5):412‐414. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sun Y, Chai Y, He H, Li J, Gu G, Li Y. Investigation and analysis of the intelligence and mentality in children with acute leukemia after long‐term chemotherapy. J China Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;11(6):297‐300. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Li H, Wang X, Wu X, Qu J, Xu X. Current status and influencing factors of psychological resilience in adolescent leukemia survivors. Chin J Modern Nurs. 2021;27(25):3432‐3437. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fan Z, Guo W. Investigation into quality of life in long‐term survival children with malignant lymphomas. Mil Med J South China. 2007;21(4):50‐51. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Liu Y, Ma L, Mo L, Zhang C. Application of short distance communication mode on continuous nursing for children with leukemia. Nurs J Chin People's Liberation Army. 2018;35(13):49‐53. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wang L, Hong D. Investigation on family cohesion and adaptability of leukemia children during remission period. J Nurs Sci. 2007;22(23):25‐26. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fu H, Li C, Zhou L, Wang Y, Wu X, Tao S. Effects of intensive health education KAP and psychological status of leukemia patients' families. J China Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;21(4):198‐210. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Post MW. Definitions of quality of life: what has happened and how to move on. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2014;20(3):167‐180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhao G. Study on the Economic Burden of Leukemia Children and the Compensation Effect of Charity Medical Assistance ‐‐ A Case Study of Z Project [M]. Shandong Univeristy; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ren Y, Ji Q, Zhang J, Zhang L, Li X. The disease‐related burden of families with children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Chin Gen Pract. 2015;1:19‐21. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Huang X, Zhang H, Yang M, et al. Investigation on family economic burden and objective social support of children with acute leukemia. Health Econ Res. 2019;36(7):38‐40. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wang J, Zhang F. Study on the effect of nosocomial infection on hospitalization expenses——taking children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia as an example. Health Econ Res. 2019;36(1):26‐28. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Chang R, Chen Z, Xi Y, Wu S, Chen W, Li Z. Analysis of direct economic burden in hospitalized leukemia children from 2003 to 2012, Gansu Province. Chin Gen Pract. 2015;18(5):569‐572. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Marinho DH, Ribeiro LL, Nichele S, et al. The challenge of long‐term follow‐up of survivors of childhood acute leukemia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in resource‐limited countries: a single‐center report from Brazil. Pediatr Transplant. 2020;24(4):e13691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rossell N, Olarte‐Sierra MF, Challinor J. Survivors of childhood cancer in Latin America: role of foundations and peer groups in the lack of transition processes to adult long‐term follow‐up. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2021;e1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Geng HM, Chuang DM, Yang F, et al. Prevalence and determinants of depression in caregivers of cancer patients: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(39):e11863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wang X, Fan L. Application of family centered nursing in children with leukemia and its influence on hope level of family members, psychological resilience and quality of life of children. Lab Med Clin. 2018;15(24):3752‐3755. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wu L, Liu L, He J, Jin T, Liu Y. Effect evaluation on establishment of support system of parents of children with leukemia. Chin Nurs Res. 2014;28(8):964‐965. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jiang Y, Zhen H, Zhang M, Zhao Z, Luo H, Lin L. Influence of individualized nursing based on IKAP model on anxiety and depression status of family members of children with leukemia. J Int Psychiatry. 2018;45(4):765‐768. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Yabroff KR, Zhao J, Zheng Z, Rai A, Han X. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States: what do we know? What do we need to know? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(12):1389‐1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Han X, Zhao J, Zheng Z, de Moor JS, Virgo KS, Yabroff KR. Medical financial hardship intensity and financial sacrifice associated with cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29(2):308‐317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Frobisher C, Lancashire ER, Jenkinson H, et al. Employment status and occupational level of adult survivors of childhood cancer in Great Britain: the British childhood cancer survivor study. Int J Cancer. 2017;140(12):2678‐2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Nipp RD, Kirchhoff AC, Fair D, et al. Financial burden in survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(30):3474‐3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tao W, Zeng Z, Dang H, et al. Towards universal health coverage: achievements and challenges of 10 years of healthcare reform in China. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(3):e002087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wilson CL, Stratton K, Leisenring WL, et al. Decline in physical activity level in the childhood cancer survivor study cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(8):1619‐1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Gibson TM, Liu W, Armstrong GT, et al. Longitudinal smoking patterns in survivors of childhood cancer: an update from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer. 2015;121(22):4035‐4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ji X, Cummings J, Mertens A, Wen H, Effinger K. Substance use, substance use disorders, and treatment in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors – results from a National Survey. Cancer. 2021;127(17):3223‐3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Klosky JL, Hudson MM, Chen Y, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination rates in young cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(31):3582‐3590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wang M, Luo X, Xu S, et al. Trends in smoking prevalence and implication for chronic diseases in China: serial national cross‐sectional surveys from 2003 to 2013. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(1):35‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Li X, Krumholz HM, Yip W, et al. Quality of primary health care in China: challenges and recommendations. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1802‐1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Sun L, Yang Y, Vertosick E, Jo S, Sun G, Mao JJ. Do perceived needs affect willingness to use traditional Chinese Medicine for survivorship care among Chinese cancer survivors? A cross‐sectional survey. J Glob Oncol. 2017;3(6):692‐700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Cheung YT, Zhang H, Cai J, et al. Identifying priorities for harmonizing guidelines for the long‐term surveillance of childhood cancer survivors in the Chinese children cancer group (CCCG). JCO Glob Oncol. 2021;7:261‐276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Council NR . Childhood cancer survivorship: improving care and quality of life. 2003. [PubMed]

- 86. Mertens AC, Cotter KL, Foster BM, et al. Improving health care for adult survivors of childhood cancer: recommendations from a delphi panel of health policy experts. Health Policy. 2004;69(2):169‐178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Long‐Term Follow‐up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers Version 5.0. Children's Oncology Group Statistics and Data Center; 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data were created or analyzed in this study.