Abstract

Proteins secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis are usually targets of immune responses in the infected host. Here we describe a search for secreted proteins that combined the use of bioinformatics and phoA′ fusion technology. The 3,924 proteins deduced from the M. tuberculosis genome were analyzed with several computer programs. We identified 52 proteins carrying an NH2-terminal secretory signal peptide but lacking additional membrane-anchoring moieties. Of these 52 proteins—the TM1 subgroup—only 7 had been previously reported to be secreted proteins. Our predictions were confirmed in 9 of 10 TM1 genes that were fused to Escherichia coli phoA′, a marker of subcellular localization. These findings demonstrate that the systematic computer search described in this work identified secreted proteins of M. tuberculosis with high efficiency and 90% accuracy.

Proteins released by Mycobacterium tuberculosis to the extracellular environment have been the focus of much of the research directed at identifying antigens that induce protective immunity or those that elicit immune responses of diagnostic value (reviewed in references 2, 11, and 37). Two different experimental approaches have been used. One is analysis of the protein composition of M. tuberculosis culture filtrates. The M. tuberculosis culture filtrate, which contains as many as 200 proteins (29), has been investigated by means of protein purification, by immunological methods, and by screening of expression libraries of M. tuberculosis DNA with anti-culture filtrate sera (for examples, see references 1, 4, 5, 19, 25, 33, and 34). A second, genetic approach involves the screening of libraries of fusions of M. tuberculosis genes to reporter genes encoding enzymes that become active upon translocation across the cell membrane (7, 18). As a result of the combined efforts of several laboratories, more than 30 secreted proteins of M. tuberculosis have been characterized (examples are provided in references 3, 6, 9, 10, 12, 15, 17, 18, 20, 22, 26, 30, 32, and 34). Nevertheless, much of the immunological activity of the culture filtrate of M. tuberculosis remains unaccounted for.

Analysis of the NH2-terminal sequences of proteins purified from the culture filtrate vis-à-vis corresponding deduced amino acid sequences (34, 37) indicates that many proteins of M. tuberculosis are secreted via the general export pathway (GEP). The GEP mediates protein translocation across the cytoplasmic membrane by means of an NH2-terminal secretory signal peptide (24, 28). Following translocation, cleavage of the signal peptide by a signal peptidase releases the mature protein, providing that there are no additional membrane-spanning segments or membrane-anchoring moieties (Fig. 1). The conserved features of signal peptides (length and amino acid composition plus the signal peptidase cleavage site [31]) make them amenable to identification by sequence analysis. Thus, we set out to identify proteins of M. tuberculosis secreted via the GEP by using a bioinformatic approach that takes advantage of the recently released nucleotide sequence of the M. tuberculosis genome (8).

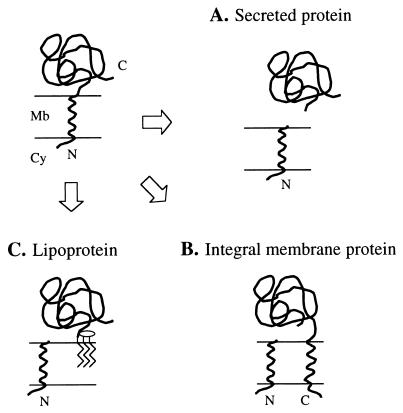

FIG. 1.

Fates of proteins having an NH2-terminal signal peptide. The NH2-terminal signal peptide directs translocation of a protein across the cell membrane (top left panel). Processing of the preprotein by a type I signal peptidase releases the mature protein (A), providing that there are no additional transmembrane domains (B). Translocation of LPPs across the membrane is followed by modification with glycerol and fatty acids of the prolipoprotein and processing by a type II signal peptidase. The lipid moiety anchors the LPP to the membrane (C). Mb, cell membrane; Cy, cytoplasm; N, NH2-terminal end; C, COOH-terminal end.

Prediction of secreted proteins of M. tuberculosis.

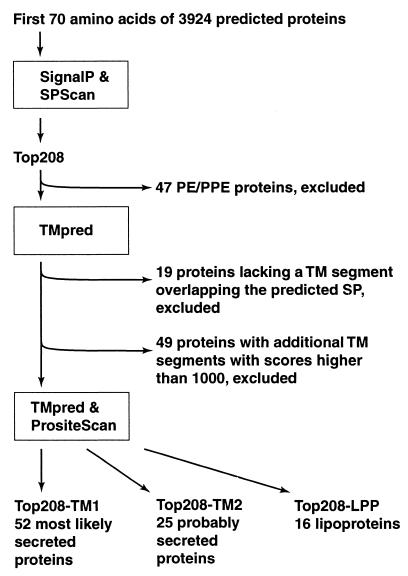

The computer strategy used to identify proteins having secretory signal peptides but lacking additional membrane attachment domains is presented in Fig. 2. The amino acid sequences of 3,924 proteins deduced from the nucleotide sequence of the M. tuberculosis genome were downloaded from the Sanger Center database (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/M_tuberculosis). Segments containing the NH2-terminal 70 amino acid residues of each polypeptide were analyzed for secretory signal peptides with two computer programs, SignalP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP) and SPScan (13). The two programs assigned scores to potential signal peptides for all of the proteins except two (Rv1572c and Rv3599c) that were too short for SPScan analysis. Scores ranged from 0.039 to 0.888 for SignalP predictions and from −3.8 to +14.8 for SPScan predictions (Fig. 3). Cutoff values for the computer predictions were chosen on the basis of scores assigned to nine known secreted proteins of M. tuberculosis that contain a signal peptide (Ag85A, Ag85B, Ag85C, MPT32, MPT51, MPT53, MPT63, MPT64, and MPB70) (34). For these proteins, SignalP scores ranged from 0.425 to 0.758 and SPScan scores ranged from 8 to 11.2. We chose score cutoffs of 0.4 for SignalP and 8.0 for SPScan. Both values are more restrictive than the default cutoff values (0.34 for SignalP and 3.5 for SPScan). Two hundred eight proteins (5% of the proteome) scored above the cutoff with both programs (boxed inset in Fig. 3). This set of proteins is henceforth referred to as the Top208 group.

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the strategy utilized to predict M. tuberculosis secreted proteins. TM, transmembrane; SP, signal peptide; PE/PPE, families of M. tuberculosis proteins containing multiple copies of sequences rich in small-side-chain amino acid residues (8).

FIG. 3.

Correlation between SignalP and SPScan scores. Each circle represents one of the 3,924 deduced proteins of M. tuberculosis. The position of the circle indicates the scores assigned by SignalP and SPScan to the signal peptide. For this study, the two computer programs were set in the mode for gram-positive bacteria. SPScan was used in the adjusted mode, which penalizes signal peptides longer than 45 amino acid residues (i.e., the maximal length for gram-positive bacteria). The boxed area contains the Top208 group of proteins that scored ≥0.4 with SignalP and ≥8 with SPScan. The solid circles within the boxed area represent nine known secreted proteins (Ag85A, Ag85B, Ag85C, MPT32, MPT51, MPT53, MPT63, MPT64, and MPB70) (34) that were used to set cutoff values for SignalP and SPScan scores. The solid circles outside of the boxed area represent four known proteins (MPT46, GroES, GroEL2, and DnaK) containing no signal peptide (34). Also outside of the boxed area is located the 38-kDa antigen, a secreted protein which exhibits an LPP type of signal peptide (14).

Of the proteins in the Top208 group, 47 had been previously annotated as members of the PE and PPE families (8). Proteins in these families contain multiple copies of motifs rich in small-side-chain amino acid residues, such as alanine and glycine. Since a biased amino acid composition and a repetitive primary sequence could lead to unreliable results in sequence analyses, the 47 PE and PPE proteins in the Top208 group were not further analyzed.

Proteins that cross the membrane via the GEP are released to the external environment after cleavage of the signal peptide only if they lack membrane-anchoring sequences (Fig. 1). To eliminate from our study those proteins that contain membrane-spanning segments, the remaining 161 proteins in the Top208 group were analyzed with the program TMpred (http: //www.ch.embnet.org/software/TMPRED_form.html) (Fig. 2). The presence of an NH2-terminal transmembrane segment (i.e., the putative signal peptide) was confirmed by TMpred only for 142 proteins. Of these, 49 were putative integral membrane proteins, for they contained transmembrane segments within the mature protein that scored >1,000 (the default cutoff score for TMpred is 500) (Fig. 2). The remaining 93 proteins were analyzed for membrane lipoprotein (LPP) lipid attachment sites with the program PrositeScan (http://www.isrec.isb-sib.ch/software/PSTSCAN_form.html) (LPP motif, PROSITE database entry PS00013). We defined three subgroups based on TMpred and PrositeScan predictions (Fig. 2). The first subgroup, Top208-TM1, comprised 52 proteins that were classified as “most likely secreted.” These proteins contained one transmembrane domain corresponding to the signal peptide, no additional membrane-spanning segments having TMpred scores above 500, and no LPP motifs. The second subgroup, Top208-TM2, consisted of 25 proteins that were classified as “possibly secreted” because the mature proteins contained segments having TMpred scores between 500 and 1,000. The remaining 16 proteins (the Top208-LPP subgroup) were predicted to be LPPs, for they contained a properly positioned LPP motif.

The 52 proteins comprising the Top208-TM1 subgroup are listed in Table 1. Thirty-two of the TM1 proteins were previously unrecognized as secreted proteins (set A in Table 1, column 2), while 13 TM1 proteins had annotations in the Sanger Center database that suggest the presence of NH2-terminal signal peptides (set B in Table 1, column 2). Only seven TM1 proteins were previously known as secreted proteins (Mtb8.4, MTB12, MTC28, MPT32, MPT53, MPT63, and MPT64) (9, 12, 17, 19, 20, 32, 34, 36) (set C in Table 1, column 2). Sixteen of the 52 TM1 proteins were assigned a probable function on the basis of the presence of functional motifs or similarities to proteins with known functions (Table 1, column 6).

TABLE 1.

Top208-Tm1 proteinsa

| Gene name | Set | SPScan score | SignalP score | SPScan-predicted signal peptide sequence | Relevant notes regarding function or identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rv0315* | A | 14.8 | 0.667 | MLMPEMDRRRMMMMAGFGALAAALPAPTAWA ^DP | Glucanase (SCDB) |

| rv3668c* | A | 13.8 | 0.787 | LQTAHRRFAAAFAAVLLAVVCLPANTAAA ^DD | Possible protease (SCDB) |

| rv0477 | B | 13.7 | 0.888 | MKALVAVSAVAVVALLGVSSAQA ^DP | |

| rv0398c | A | 12.6 | 0.71 | MGVIARVVGVAACGLSLAVLAAAPTAGA ^EP | |

| rv3096 | A | 12.4 | 0.621 | VHRRTALKLPLLLAAGTVLGQAPRAAA ^EE | Glycosylhydrolase family 5 signature (PS00659) |

| rv3354* | A | 12.4 | 0.672 | MNLRRHQTLTLRLLAASAGILSAAAFAAPAQA ^NP | |

| rv1291c | B | 12 | 0.663 | MFTRRFAASMVGTTLTAATLGLAALGFAGTASA ^SS | |

| rv0559c | B | 11.9 | 0.873 | MKGTKLAVVVGMTVAAVSLAAPAQA ^DD | |

| rv1891 | A | 11.7 | 0.53 | MIRELVTTAAITGAAIGGAPVAGA ^DP | |

| rv3333c | A | 11.5 | 0.538 | MFTGIASHAGALGAALVVLIGAAILHDGPAAA ^DP | |

| rv0040c | C | 11.4 | 0.7 | MIQIARTWRVFAGGMATGFIGVVLVTAGKASA ^DP | MTC28 (19) |

| rv1269c* | A | 11.4 | 0.73 | MTTMITLRRRFAVAVAGVATAAATTVTLAPAPANA ^AD | |

| rv2253 | B | 11.3 | 0.824 | MSGHRKKAMLALAAASLAATLAPNAVAA ^AE | |

| rv1860 | C | 11.2 | 0.627 | MHQVDPNLTRRKGRLAALAIAAMASASLVTVAVPATANA ^DP | MPT32 (17) |

| rv0455c | B | 11 | 0.661 | MSRLSSILRAGAAFLVLGIAAATFPQSAAA ^DS | |

| rv1268c* | A | 10.9 | 0.779 | MTTSKIATAFKTATFALAAGAVALGLASPADA ^AA | Cys proteases histidine active site (PS00639) |

| rv1174c | C | 10.6 | 0.579 | MRLSLTALSAGVGAVAMSLTVGAGVASA ^DP | Mtb8.4SA-5K (9, 12) |

| rv2376c | C | 10.5 | 0.438 | MAGGPVVYQMQPVVFGAPLPLDPASA ^PD | MTB12 (32) |

| rv2450c* | B | 10.5 | 0.697 | LKNARTTLIAAAIAGTLVTTSPAGIANA ^DD | Putative pheromone (23) |

| rv1271c | A | 10.2 | 0.592 | MLSPLSPRIIAAFTTAVGAAAIGLAVATAGTAGA ^NT | |

| rv1980c | C | 10.2 | 0.83 | VRIKIFMLVTAVVLLCCSGVATA ^AP | MPT64 (36) |

| rv0617 | A | 10 | 0.458 | VTVLLDANVLIALVVAEHVHH ^DA | |

| rv0674 | A | 10 | 0.635 | MPAMTARSVVLSVLLGAHPAWA ^TA | |

| rv1906c* | A | 10 | 0.753 | MRLKPAPSPAAAFAVAGLILAGWAGSVGLAGA ^DP | |

| rv1006 | A | 9.9 | 0.432 | MVLRSRKSTLGVVVCLALVLGGPLNGCSSSA ^SH | |

| rv2389c | A | 9.5 | 0.842 | MFVALLGLSTISSKA ^DD | Putative pheromone (23) |

| rv2878c | C | 9.4 | 0.581 | MSLRLVSPIKAFADGIVAVAIAVVLMFGLANTPRAVA ^AD | MPT53, DsbE (34) |

| rv3036c | B | 9.4 | 0.598 | MRYLIATAVLVAVVLVGWPAAGA ^PP | Similar to MPT64 (SCDB) |

| rv1566c* | B | 9.2 | 0.55 | MKRSMKSGSFAIGLAMMLAPMVAAPGLAAA ^DP | Similar to Listeria invasion-associated p60 (SCDB) |

| rv1974 | A | 9.2 | 0.557 | VQRQSLMPQQTLAAGVFVGALLCGVVTA ^AV | |

| rv1419 | A | 9.1 | 0.695 | MGELRLVGGVLRVLVVVGAVFDVAVLNAGAASA ^DG | |

| rv3106 | A | 9.1 | 0.494 | MRPYYIAIVGSGPSAFFA ^AA | FprA, NADPH ferredoxin reductase? (SCDB) |

| rv1813c | A | 8.9 | 0.584 | MITNLRRRTAMAAAGLGAALGLGILLVPTVDAHL ^AN | |

| rv3013 | A | 8.9 | 0.543 | VRSYLLRIELADRPGSLGSLAVALGSVGA ^DI | |

| rv0199 | A | 8.8 | 0.537 | MFSTYGIASTLLGVLSVAAVVLGAMIWSAHR ^DD | |

| rv0867c | B | 8.8 | 0.616 | MSGRHRKPTTSNVSVAKIAFTGAVLGGGGIAMA ^AQ | Putative pheromone (23) |

| rv2576c | A | 8.8 | 0.669 | MTSVRTVPSAVALVTFAGAALSGVIPAIARA ^DP | |

| rv3170 | A | 8.8 | 0.444 | VTNPPWTVDVVVVGAGFAGLAAA ^RE | Probable monoamine oxidase (SCDB) |

| rv3572 | A | 8.7 | 0.578 | MTRLIPGCTLVGLMLTLLPAPTSAA ^GS | |

| rv0592 | B | 8.6 | 0.413 | MSTIFDIRSLRLPKLSAKVVVVGGLVVVLAVVAAA ^AG | Part of mce-2 operon (SCDB) |

| rv1352 | A | 8.6 | 0.592 | MARTLALRASAGLVAGMAMAAITLAPGARA ^ET | |

| rv1242 | A | 8.5 | 0.555 | VIIPDINLLLYAVITGFPQHRRAHA ^WW | |

| rv0309 | A | 8.4 | 0.537 | MSRLLALLCAAVCTGCVAVVLAPVSLAVVNPWFA ^NS | Heavy-metal-associated domain (PS01047) |

| rv0360c | A | 8.4 | 0.412 | VTKRTITPMTSMGDLLGPEPILLPGDSDAEAELLANESPSIVAA ^AH | |

| rv1804c | A | 8.4 | 0.631 | MRVVSTLLSIPLMIGLAVPAHA ^GP | |

| rv2223c* | B | 8.4 | 0.679 | MAAMWRRRPLSSALLSFGLLLGGLPLAAPPLAGA ^TE | Lipase, serine active site (SCDB) |

| rv1488 | A | 8.3 | 0.721 | VQGAVAGLVFLAVLVIFAIIVVAKSVALIPQAEA ^AV | Hemopexin domain signature (PS00024) |

| rv2290* | B | 8.3 | 0.424 | LTDPRHTVRIAVGATALGVSALGATLPACSAHS ^GP | LppO, similar to 19-kDa antigen (SCDB) |

| rv3207c | A | 8.3 | 0.469 | VSTYGWRAYALPVLMVLTTVVVYQTVTGTSTPRPAAA ^QT | Zn protease (SCDB) |

| rv0203 | B | 8.2 | 0.485 | MKTGTATTRRRLLAVLIALALPGAAVALLAEPSATG ^AS | |

| rv0603 | A | 8.2 | 0.466 | MNRIVQFGVSAVAAAAIGIGAGSGIAAA ^FD | |

| rv1926c* | C | 8 | 0.57 | MKLTTMIKTAVAVVAMAAIATFAAPVALA ^AY | MPT63 (20) |

The 52 proteins of M. tuberculosis in the Top208-TM1 subgroup are sorted by decreasing SPScan scores. Genes analyzed by phoA′ fusion technology are marked with asterisks. Set A includes 32 proteins that had no annotations in the Sanger Center database (SCDB) referring to protein topology or subcellular localization, set B includes 13 proteins that were annotated as “probably secreted, or exported, or having a putative signal sequence, or a hydrophobic amino acid stretch at the NH2-terminus,” and set C includes seven proteins known to be secreted by a signal peptide-dependent mechanism (see text). The position of the predicted cleavage site is indicated by a caret. Relevant notes regarding function or identity are based on previously published reports, Sanger Center database annotations, or Blast and PrositeScan searches.

Analysis of TM1 proteins by phoA′ fusion technology.

A method to study protein topology with respect to the cell membrane is to analyze the enzymatic activity of a hybrid consisting of the test protein and the reporter Escherichia coli PhoA protein devoid of its original signal peptide (21). To test the prediction that the proteins in the TM1 subgroup contained a single transmembrane domain, the signal peptide (Fig. 1), fusions were constructed between phoA′ and full-length M. tuberculosis TM1 coding sequences. To introduce a minimum of bias in these experiments, we chose 10 proteins at random from the TM1 subgroup. These 10 proteins (marked with asterisks in Table 1, column 1) represented a broad range of SPScan scores (8.3 to 14.8) and SignalP scores (0.469 to 0.787) and were equally divided between those having (set B) and those not having (set A) database annotations with reference to topology or localization.

Recombinant plasmids bearing fusions of phoA′ with M. tuberculosis TM1 genes were constructed in E. coli. Clones carrying the fusions were evaluated for alkaline phosphatase activity by plating on Luria-Bertani agar containing the chromogenic substrate 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP). On indicator plates, alkaline phosphatase activity is seen as blue-green colonies. The colony color phenotype of one representative clone for each fusion is shown in Fig. 4. Nine of 10 fusions exhibited alkaline phosphatase activity. The only phoA′ fusion that yielded a weak, albeit detectable, blue-green colony color was that with Rv3354 (clone 12 in Fig. 4). All of the hybrid proteins, except that encoded by the Rv3354::phoA′ fusion, were detected by Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates with anti-PhoA antibodies (data not shown). These results suggest that the hybrid protein encoded by the Rv3354::phoA′ fusion is either synthesized at low levels or rapidly degraded. The finding that 9 of 10 mycobacterial protein hybrids directed export of the PhoA moiety provides strong evidence that proteins in the Top208-TM1 subgroup are bona fide secreted proteins.

FIG. 4.

Alkaline phosphatase activity of 10 M. tuberculosis TM1 proteins fused to PhoA. phoA′ fusions were constructed in E. coli plasmid pUCCMPHOA (16), a pUC18 derivative that carries phoA′ downstream of codon 18 of lacZ. phoA′ lacks the nucleotide sequences coding for the NH2-terminal signal peptide and the first 11 amino acid residues of the mature PhoA protein. Hybrid gene expression in pUCCMPHOA utilizes the lac promoter and the lacZ ribosome binding site and start codon. Full-length M. tuberculosis coding sequences (Mtcds) were synthesized from chromosomal DNA by PCR, cloned into plasmid pCR2.1 (Invitrogen), and subsequently transferred into pUCCMPHOA using appropriate restriction endonuclease sites to obtain in-frame lacZ-Mtcds-phoA′ fusions. Recombinant plasmids were characterized by nucleotide sequence analysis of the DNA junctions. E. coli clones bearing vector pUCCMPHOA and 12 different phoA fusions were tested for alkaline phosphatase activity on Luria-Bertani agar plates containing BCIP at 40 μg ml−1. Plate sectors: 1, pUCCMPHOA (negative control); 2, B. subtilis membrane protein ComP (positive control) (27); 3, secreted protein MPT63 of M. tuberculosis (positive control—also one of the TM1 proteins) (20); 4, Rv0315; 5, Rv1268c; 6, Rv1269c; 7, Rv1566c; 8, Rv1906c; 9, Rv2223c; 10, Rv2290; 11, Rv2450c; 12, Rv3354; 13, Rv3668c.

In summary, 52 proteins (the Top208-TM1 subgroup) were identified by computer-based analyses as most likely secreted. The computer predictions were confirmed in 90% of the TM1 proteins tested by E. coli phoA′ gene fusion methods. Only 7 of the 52 TM1 proteins had been previously reported to be secreted proteins. Thus, the bioinformatic method used in the present paper is highly efficient and accurate. The high accuracy is explained by the use of stringent selection criteria (i.e., high cutoff scores for SignalP, SPScan, and TMpred).

The computer-based approach that we have used to identify secreted proteins differs in several important ways from genetic screening methods employing random fusions to phoA′ or bla, markers of extracellular localization. First, methods that employ random fusions do not allow distinction between secretory signal peptides and transmembrane domains of membrane-bound proteins (reference 35 and references therein). Second, expression of alkaline phosphatase activity by clones generated by random insertion of phoA-coupled transposons critically depends on the strength of promoters located upstream of the transposition site (21). The same limitation applies to the screening of random fusion libraries in promoterless plasmids. Third, gene fusion library screening methods often yield multiple hits in the same genes, thus making the process of gene identification labor intensive (7). A disadvantage of the computer-based approach is that it is limited to only those proteins secreted via the GEP. While many secreted antigens of M. tuberculosis fall into this category, the presence in culture filtrates of proteins lacking secretory signal peptides (e.g., ESAT-6, SodA, GlnA, and KatG [15, 29, 30, 38]) suggests the existence of other, still undefined, mechanisms of protein secretion that operate in M. tuberculosis.

The identification of novel secreted proteins of M. tuberculosis opens the way to studies on their subcellular localization in M. tuberculosis and to the immunological characterization of these proteins to define their potential for immunological diagnosis of tuberculosis or vaccine design.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Dubnau for providing plasmid pUCCMPHOA and Carol Lusty and Karl Drlica for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by NIH grant AI-36989 (M.L.G.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Amara R R, Satchidanandam V. Analysis of a genomic DNA expression library of Mycobacterium tuberculosis using tuberculosis patient sera: evidence for modulation of host immune response. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3765–3771. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3765-3771.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen A B, Brennan P. Proteins and antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In: Bloom B R, editor. Tuberculosis: pathogenesis, protection, and control. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 307–327. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen A B, Hansen E B. Structure and mapping of antigenic domains of protein antigen b, a 38,000-molecular-weight protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2481–2488. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.8.2481-2488.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen P, Askgaard D, Gottschau A, Bennedsen J, Nagai S, Heron I. Identification of immunodominant antigens during infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol. 1992;36:823–831. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1992.tb03144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersen P, Askgaard D, Ljungqvist L, Bennedsen J, Heron I. Proteins released from Mycobacterium tuberculosis during growth. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1905–1910. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.1905-1910.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashbridge K R, Booth R J, Watson J D, Lathigra R B. Nucleotide sequence of the 19 kDa antigen gene from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:1249. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.3.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chubb A J, Woodman Z L, da Silva Tatley F M, Hoffmann H J, Scholle R R, Ehlers M R. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis signal sequences that direct the export of a leaderless beta-lactamase gene product in Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 1998;144:1619–1629. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-6-1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry C E, 3rd, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Barrell B G, et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coler R N, Skeiky Y A, Vedvick T, Bement T, Ovendale P, Campos-Neto A, Alderson M R, Reed S G. Molecular cloning and immunologic reactivity of a novel low molecular mass antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1998;161:2356–2364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Content J, de la Cuvellerie A, De Wit L, Vincent-Levy-Frebault V, Ooms J, De Bruyn J. The genes coding for the antigen 85 complexes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis BCG are members of a gene family: cloning, sequence determination, and genomic organization of the gene coding for antigen 85-C of M. tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3205–3212. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3205-3212.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper A M, Flynn J L. The protective immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:512–516. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freer G, Florio W, Dalla Casa B, Bottai D, Batoni G, Maisetta G, Senesi S, Campa M. Identification and molecular cloning of a novel secretion antigen from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Res Microbiol. 1998;149:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(98)80302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genetics Computer Group. Wisconsin Package Version 9.1. Madison, Wis: Genetics Computer Group; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harboe M, Wiker H G. The 38-kDa protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a review. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:874–884. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.4.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harth G, Clemens D L, Horwitz M A. Glutamine synthetase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: extracellular release and characterization of its enzymatic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9342–9346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inamine G S, Dubnau D. ComEA, a Bacillus subtilis integral membrane protein required for genetic transformation, is needed for both DNA binding and transport. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3045–3051. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3045-3051.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laqueyrerie A, Militzer P, Romain F, Eiglmeier K, Cole S, Marchal G. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the apa gene coding for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis 45/47-kilodalton secreted antigen complex. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4003–4010. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.4003-4010.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim E M, Rauzier J, Timm J, Torrea G, Murray A, Gicquel B, Portnoi D. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA sequences encoding exported proteins by using phoA gene fusions. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:59–65. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.59-65.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manca C, Lyashchenko K, Colangeli R, Gennaro M L. MTC28, a novel 28-kilodalton proline-rich secreted antigen specific for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4951–4957. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.4951-4957.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manca C, Lyashchenko K, Wiker H G, Usai D, Colangeli R, Gennaro M L. Molecular cloning, purification, and serological characterization of MPT63, a novel antigen secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:16–23. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.16-23.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manoil C. Analysis of membrane protein topology using alkaline phosphatase and beta-galactosidase gene fusions. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;34:61–75. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61676-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsumoto S, Matsuo T, Ohara N, Hotokezaka H, Naito M, Minami J, Yamada T. Cloning and sequencing of a unique antigen MPT70 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv and expression in BCG using E. coli-mycobacteria shuttle vector. Scand J Immunol. 1995;41:281–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1995.tb03565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukamolova G V, Kaprelyants A S, Young D I, Young M, Kell D B. A bacterial cytokine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8916–8921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy C K, Beckwith J. Export of proteins to the cell envelope in Escherichia coli. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Low K B, Magasanik B, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1987. pp. 967–978. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagai S, Wiker H G, Harboe M, Kinomoto M. Isolation and partial characterization of major protein antigens in the culture fluid of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:372–382. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.372-382.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohara N, Kitaura H, Hotokezaka H, Nishiyama T, Wada N, Matsumoto S, Matsuo T, Naito M, Yamada T. Characterization of the gene encoding the MPB51, one of the major secreted protein antigens of Mycobacterium bovis BCG, and identification of the secreted protein closely related to the fibronectin binding 85 complex. Scand J Immunol. 1995;41:433–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1995.tb03589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piazza F, Tortosa P, Dubnau D. Mutational analysis and membrane topology of ComP, a quorum-sensing histidine kinase of Bacillus subtilis controlling competence development. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4540–4548. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4540-4548.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pugsley A P. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:50–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.50-108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sonnenberg M G, Belisle J T. Definition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture filtrate proteins by two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, N-terminal amino acid sequencing, and electrospray mass spectrometry. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4515–4524. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4515-4524.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sorensen A L, Nagai S, Houen G, Andersen P, Andersen A B. Purification and characterization of a low-molecular-mass T-cell antigen secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1710–1717. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1710-1717.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watson M E E. Compilation of published signal sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:5145–5164. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.13.5145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Webb J R, Vedvick T S, Alderson M R, Guderian J A, Jen S S, Ovendale P J, Johnson S M, Reed S G, Skeiky Y A. Molecular cloning, expression, and immunogenicity of MTB12, a novel low-molecular-weight antigen secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4208–4214. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4208-4214.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weldingh K, Rosenkrands I, Jacobsen S, Rasmussen P B, Elhay M J, Andersen P. Two-dimensional electrophoresis for analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture filtrate and purification and characterization of six novel proteins. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3492–3500. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3492-3500.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiker H G, Michell S L, Hewinson R G, Spierings E, Nagai S, Harboe M. Cloning, expression and significance of MPT53 for identification of secreted proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microb Pathog. 1999;26:207–219. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1998.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Worley M J, Stojiljkovic I, Heffron F. The identification of exported proteins with gene fusions to invasin. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1471–1480. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamaguchi R, Matsuo K, Yamazaki A, Abe C, Nagai S, Terasaka K, Yamada T. Cloning and characterization of the gene for immunogenic protein MPB64 of Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Infect Immun. 1989;57:283–288. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.1.283-288.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Young D B, Kaufmann S H, Hermans P W, Thole J E. Mycobacterial protein antigens: a compilation. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:133–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Lathigra R, Garbe T, Catty D, Young D. Genetic analysis of superoxide dismutase, the 23 kilodalton antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:381–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]