Abstract

Hypertension affects a significant proportion of the adult and aging population and represents an important risk factor for vascular cognitive impairment and late-life dementia. Chronic high blood pressure continuously challenges the structural and functional integrity of the cerebral vasculature, leading to microvascular rarefaction and dysfunction, and neurovascular uncoupling that typically impairs cerebral blood supply. Hypertension disrupts blood-brain barrier integrity, promotes neuroinflammation, and may contribute to amyloid deposition and Alzheimer pathology. The mechanisms underlying these harmful effects are still a focus of investigation, but studies in animal models have provided significant molecular and cellular mechanistic insights. Remaining questions relate to whether adequate treatment of hypertension may prevent deterioration of cognitive function, the threshold for blood pressure treatment, and the most effective antihypertensive drugs. Recent advances in neurovascular biology, advanced brain imaging, and detection of subtle behavioral phenotypes have begun to provide insights into these critical issues. Importantly, a parallel analysis of these parameters in animal models and humans is feasible, making it possible to foster translational advancements. In this review, we provide a critical evaluation of the evidence available in experimental models and humans to examine the progress made and identify remaining gaps in knowledge.

Keywords: Cognitive impairment, dementia, neurovascular dysfunction, blood-brain barrier, neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration

1. Introduction

Dementia is a leading cause of death and disability. The 2021 Global Status Report on dementia by the World Health Organization estimates that 55.2 million people were living with dementia worldwide in 2019, and this number is projected to increase to 78 and 139 million people by 2030 and 2050, respectively1. The 2020 Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care emphasized that up to 40% of dementia cases can potentially be prevented or delayed by managing the associated risk factors1, 2. Vascular risk factors, including hypertension, play an important role in the pathophysiology of dementia since up to 50% of patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have a mixed pathology at autopsy including cerebrovascular lesions3, 4. Furthermore, it is now well established that midlife hypertension increases the risk for late-life dementia5, independently of genetic risk for dementia6. Thus, identifying the mechanisms underlying the relationship between hypertension and dementia remains a priority. Although studies have suggested promising risk reduction with adequate blood pressure (BP) control7, 8, the effects are mixed and inconclusive9, 10, and the question of whether certain antihypertensive classes provide greater cognitive benefits remains controversial11, 12. New discoveries and particularly novel therapeutic targets are urgently needed to protect cognitive function in hypertensive patients. Furthermore, the early identification of patients at risk could be a valuable preventive strategy to stop, or at least delay, their evolution toward dementia. Advances in neuroimaging methods have enabled the characterization of subtle neuroradiological markers of hypertension-induced brain damage before macroscopic imaging signs become evident13.

In the present review we examine the effects of hypertension on the brain, potential mechanisms involved in the development of cognitive dysfunction, and their translational impact. Furthermore, we will discuss neuroimaging biomarkers that may serve as early predictors of hypertensive brain damage and cognitive impairment, and will underline outstanding questions that remain to be addressed in the field.

2. Hypertension and the cerebral vasculature

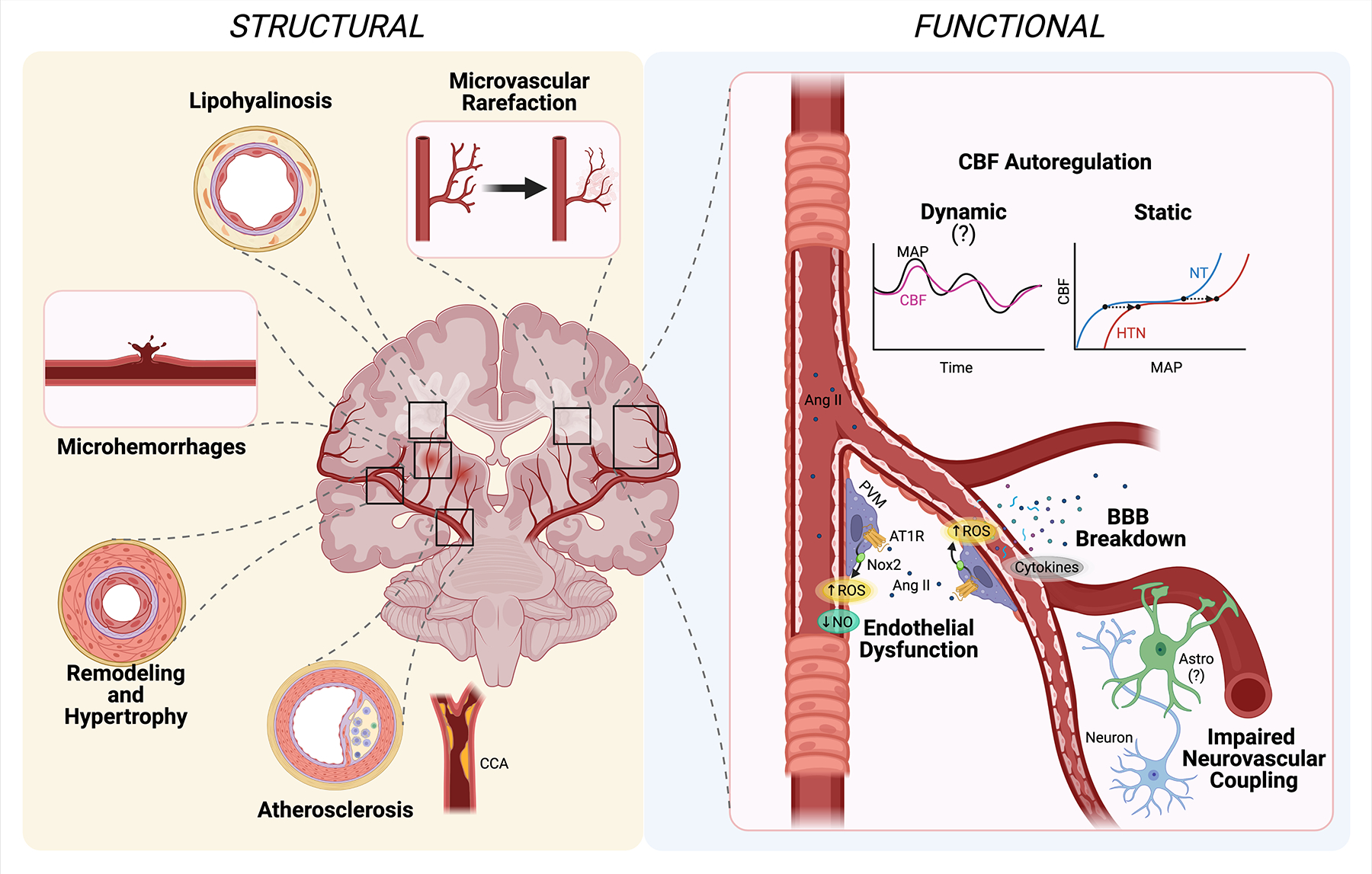

The cerebral vasculature is major target of damage induced by hypertension (Figure 1). In this section, we will examine the impact of hypertension on the structure and function of cerebral blood vessels, and on the resulting neurovascular pathology underlying cognitive impairment.

Figure 1. Hypertension induced cerebrovascular alterations.

Hypertension has profound effects on the structure and function of cerebral blood vessels associated with increased risk for cognitive impairment. Details described in the text. Ang II: angiotensin II; Astro: astrocyte; AT1R: Ang II type 1 receptor; BBB: blood-brain barrier; CCA: common carotid artery; CBF: cerebral blood flow; HTN: hypertension; MAP: mean arterial pressure; NO: nitric oxide; Nox2: NADPH oxidase 2; NT: normotension; PVM: perivascular macrophages; ROS: reactive oxygen species.

a. Effects on cerebrovascular structure

In animal models, as in humans, hypertension has been linked to structural vascular wall alterations14, 15. Hypertension is associated with or preceded by arterial stiffening16, 17, caused by various factors including collagen deposition and elastin fragmentation18. This can increase pulse pressure and mechanical stress being transferred through the cerebrovascular tree resulting in adaptive changes aimed at protecting the downstream microcirculation14. A combination of mechanical, cellular, and molecular factors induce remodeling of the vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC)19. A rearrangement of VSMC organization without changes to the cross-sectional area that results in a reduction in luminal diameter when the vessel is maximally dilated is termed eutrophic remodeling18, while an increase in VSMC cell volume or proliferation that leads to vascular wall thickening and reduction in luminal diameter is termed hypertrophic remodeling20. In various animal models of hypertension, remodeling is typically present in pial and parenchymal arterioles, while stiffening is often observed in larger arteries18. In humans, remodeling has been reported in cerebral small vessels21, and arterial stiffness has been associated with cerebral small vessel disease (SVD), cognitive decline, and dementia22. The mechanisms of remodeling have not been fully elucidated, but include a combination of mechanical, cellular, and molecular factors, such as growth-promoting and pro-inflammatory actions of angiotensin II (AngII), a peptide involved in hypertension19, as well as increased reactive oxygen species (ROS)23 and other factors20.

Hypertension promotes the development and build-up of atherosclerotic plaques in carotid, vertebral, and intracranial cerebral arteries14, 18. Endothelial dysfunction, discussed below, contributes to the development of atherosclerosis24, due to a combination of shear stress and turbulent flow25, increased free radicals, and reduced nitric oxide (NO) signaling26 that accelerate inflammation and immune cell accumulation27. Extracranial atherosclerosis increases the risk of cognitive decline28, while intracranial atherosclerosis has been associated with AD29. A recent proteomic study in autopsy samples of individuals with AD or mild cognitive impairment with intracranial atherosclerosis identified reduced synaptic regulation and plasticity as well as aberrant myelination as potential signaling mechanisms contributing to cognitive decline30. Importantly, these contributions were found to be independent of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, as well as other brain pathologies, thus unveiling a novel link between atherosclerosis and cognitive impairment in AD.

Hypertension also damages the microvasculature. Microvascular rarefaction, referring to a reduction in vascular density including both capillaries and arterioles, is present in both humans and animal models of hypertension18, 21, and considering the relative paucity of vessels in the white matter (WM), it may contribute to WM lesions. Vascular rarefaction may result from increased pressure being transmitted to the microvascular bed31, but the mechanisms remain to be elucidated. Typical hypertensive microvascular lesions include deposition of a glass-like material in the vessel wall (lipohyalinosis) and microvascular necrosis (fibrinoid necrosis)32, observed predominantly in WM arterioles. Indeed, hypertension is an important culprit in SVD33, a disorder that affects subcortical and periventricular WM arterioles, capillaries, and venules and is recognized as a major cause of cognitive impaiment32. Pathological features of SVD, detectable by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), include white matter hyperintensities (WMHs), lacunes (small WM lesion of less than 15 mm), microhemorrhages and microinfarcts34, and venous collagenosis35. Particularly, cerebral microhemorrhages are associated hypertension36, 37 and worse cognitive function38, and WMH-progression appears to be related to the duration of hypertension and effectiveness of BP control39, 40. Another feature of SVD includes enlargement of the space surrounding intracerebral arteries and veins (perivascular spaces, PVS). This finding has raised the possibility that SVD may also affect the removal of potentially toxic proteins and metabolites from the brain, a process that uses the PVS as a conduit. Still extensively debated, several clearance mechanisms have been proposed to utilize the PVS41, 42. A perivascular pathway is based on retrograde interstitial fluid (ISF) flow out of the brain parenchyma via arterial PVS, or within the wall of cerebral arteries (intramural peri-arterial drainage, IPAD)43. Although still controversial44, a “glymphatic” pathway is based on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow into the brain via arterial PVS, entering the parenchyma through aquaporin-4 channels on astrocytic end-feet and exiting the parenchyma through the same channels via venular and then venous PVS45. While there is evidence that the CSF-ISF flow may be impaired in hypertensive rats46, 47 and in a small cohort of patients with hypertension48, the role of these clearance pathways on SVD pathobiology and on the deleterious cognitive effects of hypertension remains to be defined.

b. Effects on cerebrovascular function

Due to a lack of significant energy storage, the brain is highly dependent on a continuous blood supply to maintain adequate nutrient delivery and waste clearance. The mechanisms involved in cerebral blood flow (CBF) regulation have been thoroughly reviewed previously20, 49–51; thus, we will focus on the effects of high BP on these key regulatory mechanisms.

Cerebrovascular autoregulation is a protective mechanism to ensure adequate brain perfusion despite BP fluctuations by maintaining CBF relatively constant within a certain range, typically ± 20 mmHg of baseline BP51. Static autoregulation is tested by producing stepwise increases or decreases in BP and measuring CBF once steady-state is reached51. In animal models, hypertension shifts the static autoregulatory pressure-flow curve to the right51, significantly increasing the risk for brain ischemia if pressure drops below the lower limit20. The mechanisms underlying hypertension-induced changes in autoregulation in animal models involve a combination of structural alterations to the cerebral vasculature (stiffening and remodeling, discussed above) and changes in VSMC reactivity to increases in transmural pressure (myogenic tone)51. However, the shift appears to be reversible by antihypertensive drugs of various classes52, 53, suggesting that lowering mechanical stress on the vasculature is key to protect cerebral autoregulation. In humans, there is limited data on the upper and lower limits of autoregulation due to the risks of vascular brain injury from excessive raising or lowering BP. In contrast to studies in animals, most studies in patients have reported no rightward shift of the static autoregulatory curve with hypertension51. Only one small study of 32 patients reported a rightward shift of the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation54. Importantly, CBF is maintained constant or even increased with antihypertensive treatment51, 55, including in older adults56, challenging the long-standing theory that lowering BP would lead to cerebral hypoperfusion in hypertensive patients.

The concept of dynamic autoregulation refers to the efficiency and latency of the CBF response to rapid BP changes and is assessed by transcranial doppler flowmetry in large cerebral arteries. Although dynamic autoregulation seems to be preserved in patients with hypertension57, 58, it may become impaired in untreated or malignant hypertension59, 60, as also suggested by a study in which CBF, assessed by arterial spin labelling (ASL)-MRI, was monitored during changes in perfusion pressure induced by the head-down tilt test61. However, since impaired autoregulation appears to be associated with severity of WM injury in hypertensive patients62, future investigation should address the relationship between the timing of autoregulation dysfunction and the development of vascular pathology.

Endothelial cells (EC) participate in vasomotor tone regulation in the brain as in other organs50. Hypertension impairs the ability of the endothelium to regulate CBF20, and is associated with a reduction in NO bioavailability and consequent compromise of NO-mediated vasodilation14, 18. These effects are mediated by impaired eNOS function and reduced NO production4 as well as increased vascular oxidative stress that further limits NO bioavailability63. While direct evaluation of cerebral endothelial function is not easily achieved in humans, an NO synthesis inhibitor failed to reduce retinal arteriolar blood flow in hypertensive patients, suggesting deficient NO signaling and endothelial dysfunction64. Interestingly, impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation in systemic arteries correlates with WMHs65 and microhemorrhages66, raising the possibility that endothelial dysfunction is also present in cerebral microvessels. This hypothesis is supported by studies in post-mortem arterioles from SVD patients showing an impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilator response to acetylcholine67.

EC are also the site of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which determines the bidirectional exchange of molecules between blood and brain68. Hypertension is associated with BBB disruption in several69–74, but not all75, animal models. In humans, BBB breakdown has been proposed as a core mechanism of SVD76, and is an early biomarker of cognitive decline77. Although BBB disruption has been reported in patients with hypertension78, 79, it is often difficult to evaluate the effect of hypertension in the presence of other comorbidities. The mechanisms of BBB disruption in animal models appear to be independent of BP elevation69, 74, and instead mediated by AngII70, 71, 80 and ROS72, even in models not based on direct AngII administration, such as the Dahl salt-sensitive rat71, spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR)80, and transverse aortic coarctation72. In AngII “slow pressor” hypertension, activation of the AngII type 1 receptor (AT1R) in cerebral EC by circulating AngII is necessary to initiate the disruption69. Thus, it is not surprising that the BBB is not disrupted in deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt hypertension75, a model of salt-sensitive hypertension in which circulating AngII is suppressed81. However, given that less than 15% of patients have elevated circulating AngII activity82, the role of endothelial AT1R activation in BBB breakdown in hypertensive patients remain to be determined.

Neurovascular coupling refers to the local CBF increase in response to neural activity, and is mediated by complex mechanisms involving both vascular and brain cells49. With increasing energetic demands during neural activity, the increase in CBF ensures adequate delivery of glucose and oxygen, while also clearing potentially toxic byproducts of metabolic activity49. Neurovascular coupling is attenuated in various mouse models of hypertension4, and similarly, patients with untreated hypertension have reduced regional CBF responses during various cognitive tasks83, 84. In animal model of AngII hypertension, the mechanisms of neurovascular coupling impairment are independent of the rise in BP, given that the impairment cannot be induced by BP elevation with phenylephrine85, and topical application of losartan rescues neurovascular coupling without lowering BP and is also effective in a genetic model of chronic hypertension (BPH mice)86. The molecular mechanisms of neurovascular dysfunction include AngII signaling via the AT1R in perivascular macrophages (PVM)85, as discussed in the section “Immune dysregulation and cognitive impairment in hypertension”. Although AngII augments astrocytic calcium signaling87, 88, the role of astrocyte calcium-dependent signaling in mediating neurovascular coupling remains controversial89. A recent study suggested that impairment of endothelial Kir2.1 channels, implicated in EC hyperpolarization and vasodilation in response to neural activity49, mediates the neurovascular coupling deficits in BPH mice and not AT1R90. However, this involvement was found under conditions of hyperaldosteronism resulting from long-term treatment with losartan and leading to Kir2.1 channel dysfunction, which is consistent with the observation that mineralocorticoid receptor blockade prevents cerebrovascular dysfunction and cognitive impairment in hypertensive mice91. Although elevated aldosterone levels have been associated with impaired cerebrovascular and cognitive function in elderly patients92, considering the beneficial effects of angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) on cognitive function93, 94, ARB-induced hyperaldosteronism (aldosterone breakthrough) is unlikely to be the sole driver of hypertension-induced cognitive impairment in patients. The discrepancy between the involvement of AT1R and mineralocorticoid receptors emphasize the need to investigate their interaction and relative contribution to neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction.

c. Is the neurovascular dysfunction induced by hypertension sufficient to lead to cognitive impairment?

Although it is established that high BP targets both the large and small cerebral vasculature, contributing to different types of structural and functional alterations, whether these are enough to induce cognitive impairment cannot be concluded. Impairment of hemodynamic CBF regulation and BBB damage undermine the homeostasis of the brain microenvironment, but their progression and mechanistic association with cognitive decline remains to be established. Relevant to cognitive health, it is important to highlight that aging exacerbates the microvascular damage induced by hypertension and the profound impact of brain aging on cognitive outcomes cannot be underestimated95, 96. Evidence of altered WM cerebrovascular reactivity preceding the development of WMHs97 highlights the importance of CBF regulation in the pathogenesis of hypertensive brain injury. Although antihypertensive therapy may rescue CBF56, 98, cognition is not always improved9, 10, 12, suggesting that other factors may play a role. Inflammation and oxidative stress have been highlighted as crucial factors in the pathogenesis of cerebrovascular alterations induced by hypertension, but the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms have not yet been fully elucidated. Consequently, studies investigating the molecular impact of hypertension at the single-cell level in both animal99 and human brain vasculature100 would be highly valuable.

3. Hypertension, immune dysregulation and cognitive impairment

Cytokines, both in the circulation and in the brain, may affect cerebrovascular and cognitive function. Although IL-6 alone does not induce endothelial dysfunction101, IL6-deficient mice are protected from the endothelial dysfunction induced by AngII hypertension in the carotids101, while the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 can preserve endothelial function102. Circulating IL-17, elevated in both humans and animal models of hypertension and high dietary salt, may play an important role in BP elevation103, cerebrovascular dysfunction104, and cognitive impairment105. IL-17 deficient mice have a blunted hypertensive response to AngII106, and anti-IL-17 antibodies lower BP in various models of hypertension107, 108. However, the BP lowering effects of anti-IL17 antibodies are not always consistent109, and IL-17 deficient mice are not protected from hypertension induced by DOCA + AngII110. IL-17 can influence the vasculature, as shown by the finding that chronic infusion of IL-17 induces endothelial dysfunction in aortic rings111, and IL-17 deficient mice are protected from AngII-induced aortic stiffening112. Interestingly, IL-17 can induce cerebral endothelial dysfunction and lead to cognitive impairment independently of hypertension, supporting a direct effect on the cerebral vasculature104. The contribution of IL-17 to cognitive impairment remains an important topic of investigation105, and particularly its role in hypertension-induced brain injury and cognitive decline remains to be established.

a. Brain resident immune cells

Animal studies suggest that brain resident immune cells also contribute to the cerebrovascular and cognitive effects of hypertension. Hypertensive stimuli promptly activate microglial cells113–115 which may contribute not only to BP regulation115, but also to neuroinflammation and cerebrovascular dysfunction113, 114. In patients, a positron emission tomography (PET) imaging indicator of microglial activation was associated with hypertensive SVD116. Although the contribution of microglia to hypertension-induced cognitive impairment has not been determined, a different brain resident myeloid cell, the PVM, has been implicated in its development. PVM reside in the perivascular space closely apposed to cerebral arterioles and venules and have been linked to various brain diseases117. PVM are a major source of ROS, mediate both cerebrovascular and cognitive dysfunction in animal models of hypertension85 and contribute to the BBB disruption69. Although cerebral endothelial AT1R are sufficient to initiate the disruption (discussed above), their presence on PVM is necessary for the full expression of the BBB dysfunction69 and cognitive impairment85. Furthermore, pharmacological depletion of both microglia and PVM with a colony stimulating factor 1 receptor inhibitor protected hypertensive mice against cognitive impairment113.

b. How to target the immune system in hypertension?

Given the important role of immune dysregulation in the pathobiology of hypertension, the idea of targeting the immune system to lower BP is actively being investigated118. Whether immunotherapies would prove beneficial on hypertension-induced brain injury and cognitive impairment has received far less attention and remains an area of great translational importance. For example, targeting inflammatory mediators and ROS in brain myeloid cells, particularly PVM, could be a potential therapeutic approach. However, the use of immunomodulatory drug in large populations is still controversial due to the increased risk of secondary infections among the immunosuppressed118. Therefore, it is important to identify and select permissible targets among the patients at greatest risk of developing cognitive impairment.

4. Hypertension and neurodegeneration

In addition to the cerebrovascular alterations induced by hypertension, studies have focused on the contribution of hypertension to neurodegenerative pathology, specifically deposition of the amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide, the main component of amyloid plaques and a key pathological signature of AD. In rodent models of brain amyloid accumulation, AngII-induced hypertension enhances Aβ deposition119–121, increases microhemorrhage burden122, and accelerates cognitive decline123, 124. In wild-type mice, hypertension has also been associated with Aβ deposition both in the brain parenchyma114, 125, 126 and surrounding cerebral vessels127. The underlying mechanisms have not been fully elucidated, but AngII has been suggested to increase both β-119 and γ- secretase128 activity, enzymes responsible for cleaving Aβ from the amyloid precursor protein. Interestingly, AT1R deficiency decreases Aβ generation and plaque formation128, and ARBs ameliorate amyloid pathology in both mouse models129, 130 and humans93.

Cerebral amyloid accumulation in sporadic AD is mainly caused by impaired Aβ clearance from the brain131. In addition to perivascular, paravascular, and intramural clearance pathways41, 132, 133, endothelial Aβ clearance may also occur through receptor-mediated transport across the BBB134. One such receptor is the Receptor for Advanced Glycation End products (RAGE)135. Like in AD135, hypertension may activate RAGE to induce brain Aβ accumulation and cognitive impairment in animal models126. RAGE has also been suggested to mediate Aβ deposition by modulating β- and γ-secretase activity136 and, when engaged by Aβ, to disrupt the BBB137. However, it remains unclear if these Aβ clearance pathways play a role in the cognitive impairment associated with hypertension in humans. Interestingly, plasma extracellular RAGE binding protein (EN-RAGE) levels have also been associated with increased risk of cognitive decline in a subset of participants from the Rotterdam Study138, but the link with hypertension remains to be determined.

a. Does hypertension increase Alzheimer pathology?

Besides provoking ischemic-hypoxic damage in susceptible WM regions, hypertension may contribute to the development of typical signs of AD-like neuropathology, including amyloid plaques and/or tau neurofibrillary tangles. Early studies found an association between midlife elevated BP and the presence of neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles at autopsy139. Recent studies with amyloid PET show that while amyloid deposition itself is not associated with hypertension140, its presence among hypertensive patients is closely associated with memory impairment141. Elevated levels of CSF phosphorylated tau, a biomarker of AD pathology, is associated with hypertension142, increased pulse pressure143, and elevated BP variability144. Aortic stiffness and elevated pulse pressure in older adults are also associated with higher tau burden, but not amyloid burden145. Furthermore, hypertension is associated with worse cognitive function in AD patients146. These findings raise the question of a synergistic relationship between cerebrovascular damage and AD pathology in mediating the cognitive impairment in hypertension. Although animal studies suggest this may be the case, evidence from patients is inconclusive. For example, a recent analysis of hypertensive patients enrolled in the SPRINT trial found no evidence for altered circulating biomarkers for AD, including Aβ and tau147. Thus, the question remains whether blood and/or CSF biomarkers will prove useful for early identification of hypertensive patients at risk of developing cognitive impairment.

5. Neuroimaging assessment of hypertensive brain damage

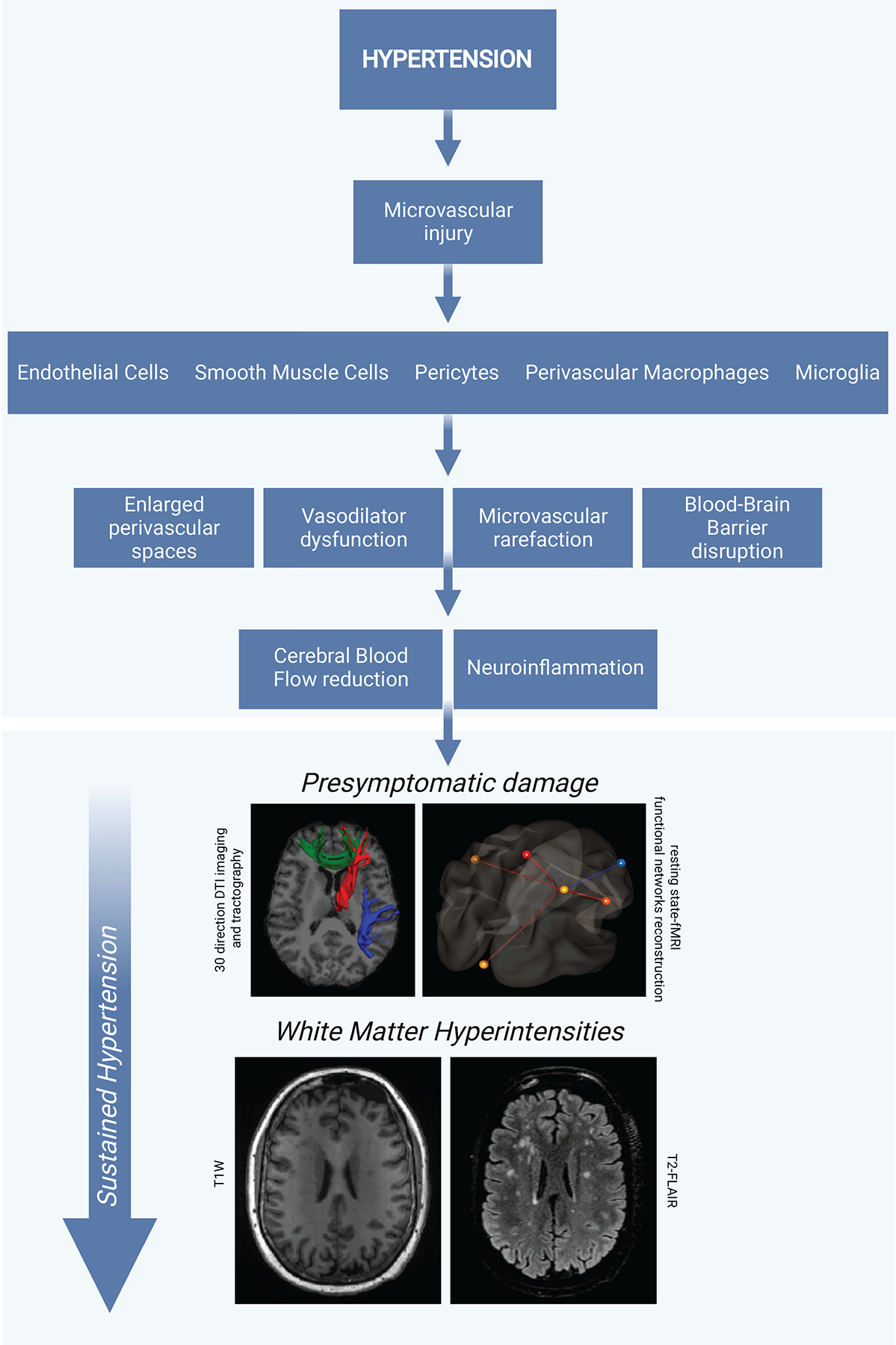

Considering the overwhelming impact of chronic hypertension on the brain and its vasculature, it is fundamental to identify early biomarkers of disease progression. Advanced brain imaging techniques, discussed below, can provide valuable tools applicable to both humans and animal models. MRI is the predominant imaging modality utilized to estimate the various manifestations of brain damage associated with hypertension. Hence, standards for MRI acquisition, interpretation, and reporting have been defined using consistent terminology characterizing the various manifestations and stages of hypertensive brain damage148. In humans, hypertension-induced brain injury is typically characterized by progression of WMHs149, microstructural150, 151 and functional alterations152, that correlate with worsening of cognitive function153 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Radiological manifestations of progressive hypertension-induced brain damage.

Hypertension promotes microvascular injury, including damage to vascular and immune cells. These effects lead to impaired vasodilation, BBB dysfunction, arterial stiffening, neuroinflammation. This progressive damage is visible on MRI scans with different levels of analysis. Microstructural damage of WM and functional altered connectivity of the brain is detectable on 30 direction DTI imaging sequences and tractography and resting state-fMRI functional networks reconstruction in a representative hypertensive patient without signs of WM matter damage evidenced at macrostructural MRI. WMH in a representative patient with sustained untreated hypertension. WM damage is barely visible as hypodense spots on T1W imaging (left) and noticeable as hyperintense spots on T2-FLAIR (right).

It is a well-established notion that WMH represents a macroscopic hallmark of advanced hypertensive brain damage14, thus neuroimaging techniques have been developed in the search for early markers of injury to identify subtle vascular changes in normal-appearing brain tissue on conventional scans. For example, the brain microstructural tissue integrity of hypertensive patients has been examined through diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), which exploits the principle of water diffusion in WM and allows estimating the direction and magnitude of diffusion by providing quantitative metrics of WM microstructural integrity154, 155. This technique makes it possible to define specific patterns of alterations that anticipate macroscopic damage and correlate with cognitive dysfunction150, 156. Another technique, dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE)-MRI, has been extensively used in patients with SVD to detect subtle regional changes in BBB integrity157.

Resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI), a sensitive tool to detect changes in brain activity using the blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) contrast, has proven effective in evidencing alterations in the functional connectivity among specific regions associated with subtle cognitive impairment in hypertension152. Another technique, ASL-MRI, enables noninvasive regional CBF quantification158, and has detected focal or global reductions in resting CBF in hypertensive patients159, 160, consistent with previous reports using other methods, such as phase-contrast MRI98, single photon emission computed tomography161, and PET162. ASL-MRI may also identify early markers potentially predictive of hypertensive brain injury, such as higher retrograde venous blood flow in the internal jugular veins of hypertensive patients163. The possibility to assess the same imaging paradigms in experimental models further corroborate the translational relevance of searching for composite biomarkers that account for cardiovascular phenotypes, brain alterations, and behavioral profiles relevant in humans.

a. Will current biomarkers identify individuals at risk of cognitive impairment early?

Early identification of signs prodromal of late-life dementia could greatly improve the management of cognitive health in hypertensive patients. Advancements in neuroradiological and analytical tools for brain imaging, in combination with the expansion of blood and CSF biomarkers, will be fundamental to provide new directions for clinicians and instruct on how to identify and manage patients at risk. The MarkVCID Consortium aims to identify and validate useful biomarkers for SVD and vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia. In addition to blood and CSF biomarkers164, they also employ neuroimaging techniques including various MRI protocols and optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA)165, a technique that visualizes retinal capillaries as a marker of cerebral capillaries. These will be powerful next steps, in addition to the ongoing Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, which has already identified cerebrovascular dysfunction as an early biomarker of AD166, and described the association between CSF phosphorylated tau and hypertension142 and increased pulse pressure143. Subgroup analyses from both these datasets may aid in the identification of hypertension-specific biomarkers.

6. Conclusions

Data reviewed here show that, despite significant advances in antihypertensive therapy, hypertension still represents one of most insidious conditions that challenge brain health. The profound effects of chronically elevated BP on the cerebral vasculature and parenchyma substantially contribute to the increased risk of dementia observed in hypertensive patients167. As discussed above, several questions remain about the development and progression of hypertension-induced cognitive impairment, the underlying mechanisms, and potential treatment strategies.

One of the most important remaining questions is whether adequate BP management provides relevant risk reduction? From a clinical perspective, intense efforts have been devoted to assessing the optimum BP threshold for therapy initiation, duration, drug class, and intensity of treatment. If BP management does improve cognitive outcomes, are certain antihypertensive drug classes superior to others? The AngII hypothesis suggests that greater neuroprotection is provided by antihypertensives that increase AT2 and AT4 activity (such as ARBs) versus those that decrease it (such as angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors [ACEi]). A recent report found reduced risk for dementia with AngII-stimulating drugs compared to AngII-inhibiting drugs among community-dwelling individuals168, a finding corroborated by new secondary analysis of a cohort of SPRINT trial participants169. Additionally, ARB but not ACEi use is associated with lower amyloid and tau170, 171, and reduced dementia risk172. The BBB permeability of antihypertensive drugs remains a topic of exploration, with a recent report suggesting potential superiority of BBB-permeable ARBs173. Another important question is whether intensive vs standard BP control will provide greater protection? This problem is being addressed by various secondary analyses of SPRINT9, 39 and PRESERVE155 trial data.

Because we cannot successfully identify patients at risk to subsequently treat and prevent hypertension-induced brain injury, extensive investigation on the molecular mechanisms underlying the cerebrovascular and neuropathological damage induced by hypertension is still needed. Considering no definitive conclusion on how to maximize benefits and reduce risks, novel therapeutic strategies are urgently needed to manage the risk of hypertension-induced brain injury and cognitive decline. These may include strategies targeting CBF regulation, the immune system, and/or clearance pathways in the brain, which can be combined with already existing antihypertensive therapy. A personalized precision medicine approach is likely to hold the key to prevent hypertension-induced cognitive decline, utilizing a combined assessment of early markers of disease, inflammatory status, vascular and metabolic comorbidities, and demographic and genetic factors.

Acknowledgements

Figures were created with BioRender.com. The support from the Leon Levy Fellowship in Neuroscience (MMS) and the Feil Family Foundation is gratefully acknowledged.

Source of Funding

M.M. Santisteban is a recipient of NIH grant NS123507 (NINDS/NIA).

Footnotes

Disclosures

C. Iadecola serves on the strategic advisory board of Broadview Ventures. The other authors report no conflicts.

References

- 1.WHO. Global status report on the public health response to dementia. World Health Organization; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the lancet commission. Lancet. 2020;396:413–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azarpazhooh MR, Avan A, Cipriano LE, Munoz DG, Sposato LA, Hachinski V. Concomitant vascular and neurodegenerative pathologies double the risk of dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:148–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santisteban MM, Iadecola C. Hypertension, dietary salt and cognitive impairment. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38:2112–2128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGrath ER, Beiser AS, DeCarli C, Plourde KL, Vasan RS, Greenberg SM, et al. Blood pressure from mid- to late life and risk of incident dementia. Neurology. 2017;89:2447–2454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Littlejohns TJ, Collister JA, Liu X, Clifton L, Tapela NM, Hunter DJ. Hypertension, a dementia polygenic risk score, apoe genotype, and incident dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2022. doi: 10.1002/alz.12680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williamson JD, Pajewski NM, Auchus AP, Bryan RN, Chelune G, Cheung AK, et al. Effect of intensive vs standard blood pressure control on probable dementia: A randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2019;321:553–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes D, Judge C, Murphy R, Loughlin E, Costello M, Whiteley W, et al. Association of blood pressure lowering with incident dementia or cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2020;323:1934–1944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rapp SR, Gaussoin SA, Sachs BC, Chelune G, Supiano MA, Lerner AJ, et al. Effects of intensive versus standard blood pressure control on domain-specific cognitive function: A substudy of the sprint randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:899–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du XL, Simpson LM, Osani MC, Yama JM, Davis BR. Risk of developing alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in allhat trial participants receiving diuretic, ace-inhibitor, or calcium-channel blocker with 18 years of follow-up. J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism. 2022;12 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters R, Yasar S, Anderson CS, Andrews S, Antikainen R, Arima H, et al. Investigation of antihypertensive class, dementia, and cognitive decline: A meta-analysis. Neurology. 2020;94:e267–e281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding J, Davis-Plourde KL, Sedaghat S, Tully PJ, Wang W, Phillips C, et al. Antihypertensive medications and risk for incident dementia and alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis of individual participant data from prospective cohort studies. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:61–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Roos A, van der Grond J, Mitchell G, Westenberg J. Magnetic resonance imaging of cardiovascular function and the brain: Is dementia a cardiovascular-driven disease? Circulation. 2017;135:2178–2195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iadecola C, Gottesman RF. Neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction in hypertension: Epidemiology, pathobiology and treatment. Circ Res. 2019;124:1025–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webb AJS, Werring DJ. New insights into cerebrovascular pathophysiology and hypertension. Stroke. 2022;53:1054–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaess BM, Rong J, Larson MG, Hamburg NM, Vita JA, Levy D, et al. Aortic stiffness, blood pressure progression, and incident hypertension. Jama. 2012;308:875–881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Humphrey JD, Harrison DG, Figueroa CA, Lacolley P, Laurent S. Central artery stiffness in hypertension and aging: A problem with cause and consequence. Circ Res. 2016;118:379–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu X, De Silva TM, Chen J, Faraci FM. Cerebral vascular disease and neurovascular injury in ischemic stroke. Circ Res. 2017;120:449–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiffrin EL. Mechanisms of remodelling of small arteries, antihypertensive therapy and the immune system in hypertension. Clin Invest Med. 2015;38:E394–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pires PW, Dams Ramos CM, Matin N, Dorrance AM. The effects of hypertension on the cerebral circulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H1598–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rizzoni D, De Ciuceis C, Porteri E, Paiardi S, Boari GE, Mortini P, et al. Altered structure of small cerebral arteries in patients with essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 2009;27:838–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Sloten TT, Protogerou AD, Henry RM, Schram MT, Launer LJ, Stehouwer CD. Association between arterial stiffness, cerebral small vessel disease and cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;53:121–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan SL, Baumbach GL. Deficiency of nox2 prevents angiotensin ii-induced inward remodeling in cerebral arterioles. Front Physiol. 2013;4:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu S, Ilyas I, Little PJ, Li H, Kamato D, Zheng X, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases and beyond: From mechanism to pharmacotherapies. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73:924–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tabas I, García-Cardeña G, Owens GK. Recent insights into the cellular biology of atherosclerosis. J Cell Biol. 2015;209:13–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Horke S, Förstermann U. Vascular oxidative stress, nitric oxide and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2014;237:208–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansson GK, Hermansson A. The immune system in atherosclerosis. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:204–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gardener H, Caunca MR, Dong C, Cheung YK, Elkind MSV, Sacco RL, et al. Ultrasound markers of carotid atherosclerosis and cognition: The northern manhattan study. Stroke. 2017;48:1855–1861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arvanitakis Z, Capuano AW, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Relation of cerebral vessel disease to alzheimer’s disease dementia and cognitive function in elderly people: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:934–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wingo AP, Fan W, Duong DM, Gerasimov ES, Dammer EB, Liu Y, et al. Shared proteomic effects of cerebral atherosclerosis and alzheimer’s disease on the human brain. Nat Neurosci. 2020;23:696–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ungvari Z, Toth P, Tarantini S, Prodan CI, Sorond F, Merkely B, et al. Hypertension-induced cognitive impairment: From pathophysiology to public health. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2021;17:639–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wardlaw JM, Smith C, Dichgans M. Small vessel disease: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:684–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lammie GA. Hypertensive cerebral small vessel disease and stroke. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:358–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ter Telgte A, van Leijsen EMC, Wiegertjes K, Klijn CJM, Tuladhar AM, de Leeuw FE. Cerebral small vessel disease: From a focal to a global perspective. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:387–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keith J, Gao FQ, Noor R, Kiss A, Balasubramaniam G, Au K, et al. Collagenosis of the deep medullary veins: An underrecognized pathologic correlate of white matter hyperintensities and periventricular infarction? J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2017;76:299–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romero JR, Preis SR, Beiser A, DeCarli C, Viswanathan A, Martinez-Ramirez S, et al. Risk factors, stroke prevention treatments, and prevalence of cerebral microbleeds in the framingham heart study. Stroke. 2014;45:1492–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ungvari Z, Tarantini S, Kirkpatrick AC, Csiszar A, Prodan CI. Cerebral microhemorrhages: Mechanisms, consequences, and prevention. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;312:H1128–h1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poels MM, Ikram MA, van der Lugt A, Hofman A, Niessen WJ, Krestin GP, et al. Cerebral microbleeds are associated with worse cognitive function: The rotterdam scan study. Neurology. 2012;78:326–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nasrallah IM, Pajewski NM, Auchus AP, Chelune G, Cheung AK, Cleveland ML, et al. Association of intensive vs standard blood pressure control with cerebral white matter lesions. Jama. 2019;322:524–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verhaaren BF, Vernooij MW, de Boer R, Hofman A, Niessen WJ, van der Lugt A, et al. High blood pressure and cerebral white matter lesion progression in the general population. Hypertension. 2013;61:1354–1359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carare RO, Aldea R, Agarwal N, Bacskai BJ, Bechman I, Boche D, et al. Clearance of interstitial fluid (isf) and csf (clic) group-part of vascular professional interest area (pia): Cerebrovascular disease and the failure of elimination of amyloid-β from the brain and retina with age and alzheimer’s disease-opportunities for therapy. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12:e12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wardlaw JM, Benveniste H, Nedergaard M, Zlokovic BV, Mestre H, Lee H, et al. Perivascular spaces in the brain: Anatomy, physiology and pathology. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16:137–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nimmo J, Johnston DA, Dodart JC, MacGregor-Sharp MT, Weller RO, Nicoll JAR, et al. Peri-arterial pathways for clearance of α-synuclein and tau from the brain: Implications for the pathogenesis of dementias and for immunotherapy. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12:e12070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mestre H, Mori Y, Nedergaard M. The brain’s glymphatic system: Current controversies. Trends Neurosci. 2020;43:458–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hablitz LM, Nedergaard M. The glymphatic system: A novel component of fundamental neurobiology. J Neurosci. 2021;41:7698–7711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koundal S, Elkin R, Nadeem S, Xue Y, Constantinou S, Sanggaard S, et al. Optimal mass transport with lagrangian workflow reveals advective and diffusion driven solute transport in the glymphatic system. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mortensen KN, Sanggaard S, Mestre H, Lee H, Kostrikov S, Xavier ALR, et al. Impaired glymphatic transport in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Neurosci. 2019;39:6365–6377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Y, Zhang R, Ye Y, Wang S, Jiaerken Y, Hong H, et al. The influence of demographics and vascular risk factors on glymphatic function measured by diffusion along perivascular space. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:693787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schaeffer S, Iadecola C. Revisiting the neurovascular unit. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24:1198–1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ashby JW, Mack JJ. Endothelial control of cerebral blood flow. Am J Pathol. 2021;191:1906–1916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Claassen J, Thijssen DHJ, Panerai RB, Faraci FM. Regulation of cerebral blood flow in humans: Physiology and clinical implications of autoregulation. Physiol Rev. 2021;101:1487–1559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vorstrup S, Barry DI, Jarden JO, Svendsen UG, Braendstrup O, Graham DI, et al. Chronic antihypertensive treatment in the rat reverses hypertension-induced changes in cerebral blood flow autoregulation. Stroke. 1984;15:312–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dupuis F, Atkinson J, Limiñana P, Chillon JM. Captopril improves cerebrovascular structure and function in old hypertensive rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144:349–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strandgaard S Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in hypertensive patients. The modifying influence of prolonged antihypertensive treatment on the tolerance to acute, drug-induced hypotension. Circulation. 1976;53:720–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dolui S, Detre JA, Gaussoin SA, Herrick JS, Wang DJJ, Tamura MK, et al. Association of intensive vs standard blood pressure control with cerebral blood flow: Secondary analysis of the sprint mind randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79:380–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Rijssel AE, Stins BC, Beishon LC, Sanders ML, Quinn TJ, Claassen J, et al. Effect of antihypertensive treatment on cerebral blood flow in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2022;79:1067–1078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Traon AP, Costes-Salon MC, Galinier M, Fourcade J, Larrue V. Dynamics of cerebral blood flow autoregulation in hypertensive patients. J Neurol Sci. 2002;195:139–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eames PJ, Blake MJ, Panerai RB, Potter JF. Cerebral autoregulation indices are unimpaired by hypertension in middle aged and older people. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16:746–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Müller M, Österreich M, Lakatos L, Hessling AV. Cerebral macro- and microcirculatory blood flow dynamics in successfully treated chronic hypertensive patients with and without white mater lesions. Sci Rep. 2020;10:9213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Immink RV, van den Born BJ, van Montfrans GA, Koopmans RP, Karemaker JM, van Lieshout JJ. Impaired cerebral autoregulation in patients with malignant hypertension. Circulation. 2004;110:2241–2245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seiller I, Pavilla A, Ognard J, Ozier-Lafontaine N, Colombani S, Cepeda Ibarra Y, et al. Arterial hypertension and cerebral hemodynamics: Impact of head-down tilt on cerebral blood flow (arterial spin-labeling-mri) in healthy and hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2021;39:979–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matsushita K, Kuriyama Y, Nagatsuka K, Nakamura M, Sawada T, Omae T. Periventricular white matter lucency and cerebral blood flow autoregulation in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 1994;23:565–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paravicini TM, Sobey CG. Cerebral vascular effects of reactive oxygen species: Recent evidence for a role of nadph-oxidase. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2003;30:855–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Delles C, Michelson G, Harazny J, Oehmer S, Hilgers KF, Schmieder RE. Impaired endothelial function of the retinal vasculature in hypertensive patients. Stroke. 2004;35:1289–1293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hoth KF, Tate DF, Poppas A, Forman DE, Gunstad J, Moser DJ, et al. Endothelial function and white matter hyperintensities in older adults with cardiovascular disease. Stroke. 2007;38:308–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nezu T, Hosomi N, Aoki S, Kubo S, Araki M, Mukai T, et al. Endothelial dysfunction is associated with the severity of cerebral small vessel disease. Hypertens Res. 2015;38:291–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bagi Z, Brandner DD, Le P, McNeal DW, Gong X, Dou H, et al. Vasodilator dysfunction and oligodendrocyte dysmaturation in aging white matter. Ann Neurol. 2018;83:142–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sweeney MD, Zhao Z, Montagne A, Nelson AR, Zlokovic BV. Blood-brain barrier: From physiology to disease and back. Physiol Rev. 2019;99:21–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Santisteban MM, Ahn SJ, Lane D, Faraco G, Garcia-Bonilla L, Racchumi G, et al. Endothelium-macrophage crosstalk mediates blood-brain barrier dysfunction in hypertension. Hypertension. 2020;76:795–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vital SA, Terao S, Nagai M, Granger DN. Mechanisms underlying the cerebral microvascular responses to angiotensin ii-induced hypertension. Microcirculation. 2010;17:641–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pelisch N, Hosomi N, Ueno M, Nakano D, Hitomi H, Mogi M, et al. Blockade of at1 receptors protects the blood-brain barrier and improves cognition in dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:362–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Poulet R, Gentile MT, Vecchione C, Distaso M, Aretini A, Fratta L, et al. Acute hypertension induces oxidative stress in brain tissues. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:253–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fan Y, Lan L, Zheng L, Ji X, Lin J, Zeng J, et al. Spontaneous white matter lesion in brain of stroke-prone renovascular hypertensive rats: A study from mri, pathology and behavior. Metab Brain Dis. 2015;30:1479–1486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Biancardi VC, Son SJ, Ahmadi S, Filosa JA, Stern JE. Circulating angiotensin ii gains access to the hypothalamus and brain stem during hypertension via breakdown of the blood-brain barrier. Hypertension. 2014;63:572–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rodrigues SF, Granger DN. Cerebral microvascular inflammation in doca salt-induced hypertension: Role of angiotensin ii and mitochondrial superoxide. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:368–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wardlaw JM, Makin SJ, Valdés Hernández MC, Armitage PA, Heye AK, Chappell FM, et al. Blood-brain barrier failure as a core mechanism in cerebral small vessel disease and dementia: Evidence from a cohort study. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:634–643 [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nation DA, Sweeney MD, Montagne A, Sagare AP, D’Orazio LM, Pachicano M, et al. Blood-brain barrier breakdown is an early biomarker of human cognitive dysfunction. Nat Med. 2019;25:270–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dankbaar JW, Hom J, Schneider T, Cheng SC, Lau BC, van der Schaaf I, et al. Age- and anatomy-related values of blood-brain barrier permeability measured by perfusion-ct in non-stroke patients. J Neuroradiol. 2009;36:219–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Muñoz Maniega S, Chappell FM, Valdés Hernández MC, Armitage PA, Makin SD, Heye AK, et al. Integrity of normal-appearing white matter: Influence of age, visible lesion burden and hypertension in patients with small-vessel disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37:644–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mowry FE, Peaden SC, Stern JE, Biancardi VC. Tlr4 and at1r mediate blood-brain barrier disruption, neuroinflammation, and autonomic dysfunction in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Pharmacol Res. 2021;174:105877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Basting T, Lazartigues E. Doca-salt hypertension: An update. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2017;19:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alderman MH, Cohen HW, Sealey JE, Laragh JH. Plasma renin activity levels in hypertensive persons: Their wide range and lack of suppression in diabetic and in most elderly patients. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jennings JR, Muldoon MF, Ryan C, Price JC, Greer P, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. Reduced cerebral blood flow response and compensation among patients with untreated hypertension. Neurology. 2005;64:1358–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jennings JR, Muldoon MF, Ryan CM, Mintun MA, Meltzer CC, Townsend DW, et al. Cerebral blood flow in hypertensive patients: An initial report of reduced and compensatory blood flow responses during performance of two cognitive tasks. Hypertension. 1998;31:1216–1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Faraco G, Sugiyama Y, Lane D, Garcia-Bonilla L, Chang H, Santisteban MM, et al. Perivascular macrophages mediate the neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction associated with hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:4674–4689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kazama K, Wang G, Frys K, Anrather J, Iadecola C. Angiotensin ii attenuates functional hyperemia in the mouse somatosensory cortex. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1890–1899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Diaz JR, Kim KJ, Brands MW, Filosa JA. Augmented astrocyte microdomain ca(2+) dynamics and parenchymal arteriole tone in angiotensin ii-infused hypertensive mice. Glia. 2019;67:551–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Boily M, Li L, Vallerand D, Girouard H. Angiotensin ii disrupts neurovascular coupling by potentiating calcium increases in astrocytic endfeet. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e020608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Del Franco AP, Chiang PP, Newman EA. Dilation of cortical capillaries is not related to astrocyte calcium signaling. Glia. 2022;70:508–521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Koide M, Harraz OF, Dabertrand F, Longden TA, Ferris HR, Wellman GC, et al. Differential restoration of functional hyperemia by antihypertensive drug classes in hypertension-related cerebral small vessel disease. J Clin Invest. 2021;131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Diaz-Otero JM, Yen TC, Fisher C, Bota D, Jackson WF, Dorrance AM. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism improves parenchymal arteriole dilation via a trpv4-dependent mechanism and prevents cognitive dysfunction in hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018;315:H1304–h1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hajjar I, Hart M, Mack W, Lipsitz LA. Aldosterone, cognitive function, and cerebral hemodynamics in hypertension and antihypertensive therapy. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:319–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hajjar I, Levey A. Association between angiotensin receptor blockers and longitudinal decline in tau in mild cognitive impairment. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:1069–1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nation DA, Ho J, Yew B. Older adults taking at1-receptor blockers exhibit reduced cerebral amyloid retention. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;50:779–789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Toth P, Tucsek Z, Sosnowska D, Gautam T, Mitschelen M, Tarantini S, et al. Age-related autoregulatory dysfunction and cerebromicrovascular injury in mice with angiotensin ii-induced hypertension. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:1732–1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Toth P, Tarantini S, Springo Z, Tucsek Z, Gautam T, Giles CB, et al. Aging exacerbates hypertension-induced cerebral microhemorrhages in mice: Role of resveratrol treatment in vasoprotection. Aging Cell. 2015;14:400–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sam K, Crawley AP, Conklin J, Poublanc J, Sobczyk O, Mandell DM, et al. Development of white matter hyperintensity is preceded by reduced cerebrovascular reactivity. Ann Neurol. 2016;80:277–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Muller M, van der Graaf Y, Visseren FL, Mali WP, Geerlings MI. Hypertension and longitudinal changes in cerebral blood flow: The smart-mr study. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:825–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vanlandewijck M, He L, Mae MA, Andrae J, Ando K, Del Gaudio F, et al. A molecular atlas of cell types and zonation in the brain vasculature. Nature. 2018;554:475–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Winkler EA, Kim CN, Ross JM, Garcia JH, Gil E, Oh I, et al. A single-cell atlas of the normal and malformed human brain vasculature. Science. 2022:eabi7377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schrader LI, Kinzenbaw DA, Johnson AW, Faraci FM, Didion SP. Il-6 deficiency protects against angiotensin ii induced endothelial dysfunction and hypertrophy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2576–2581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Didion SP, Kinzenbaw DA, Schrader LI, Chu Y, Faraci FM. Endogenous interleukin-10 inhibits angiotensin ii-induced vascular dysfunction. Hypertension. 2009;54:619–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Higaki A, Mahmoud AUM, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Role of interleukin-23/interleukin-17 axis in t-cell mediated actions in hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;117:1274–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Faraco G, Brea D, Garcia-Bonilla L, Wang G, Racchumi G, Chang H, et al. Dietary salt promotes neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction through a gut-initiated th17 response. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:240–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cipollini V, Anrather J, Orzi F, Iadecola C. Th17 and cognitive impairment: Possible mechanisms of action. Front Neuroanat. 2019;13:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Madhur MS, Lob HE, McCann LA, Iwakura Y, Blinder Y, Guzik TJ, et al. Interleukin 17 promotes angiotensin ii-induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Hypertension. 2010;55:500–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Saleh MA, Norlander AE, Madhur MS. Inhibition of interleukin 17-a but not interleukin-17f signaling lowers blood pressure and reduces end-organ inflammation in angiotensin ii-induced hypertension. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2016;1:606–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Amador CA, Barrientos V, Pena J, Herrada AA, Gonzalez M, Valdes S, et al. Spironolactone decreases doca-salt-induced organ damage by blocking the activation of t helper 17 and the downregulation of regulatory t lymphocytes. Hypertension. 2014;63:797–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Markó L, Kvakan H, Park JK, Qadri F, Spallek B, Binger KJ, et al. Interferon-γ signaling inhibition ameliorates angiotensin ii-induced cardiac damage. Hypertension. 2012;60:1430–1436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Krebs CF, Lange S, Niemann G, Rosendahl A, Lehners A, Meyer-Schwesinger C, et al. Deficiency of the interleukin 17/23 axis accelerates renal injury in mice with deoxycorticosterone acetate+angiotensin ii-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2014;63:565–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nguyen H, Chiasson VL, Chatterjee P, Kopriva SE, Young KJ, Mitchell BM. Interleukin-17 causes rho-kinase-mediated endothelial dysfunction and hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;97:696–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wu J, Thabet SR, Kirabo A, Trott DW, Saleh MA, Xiao L, et al. Inflammation and mechanical stretch promote aortic stiffening in hypertension through activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Circ Res. 2014;114:616–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kerkhofs D, van Hagen BT, Milanova IV, Schell KJ, van Essen H, Wijnands E, et al. Pharmacological depletion of microglia and perivascular macrophages prevents vascular cognitive impairment in ang ii-induced hypertension. Theranostics. 2020;10:9512–9527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Carnevale D, Mascio G, Ajmone-Cat MA, D’Andrea I, Cifelli G, Madonna M, et al. Role of neuroinflammation in hypertension-induced brain amyloid pathology. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:205 e219–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Shen XZ, Li Y, Li L, Shah KH, Bernstein KE, Lyden P, et al. Microglia participate in neurogenic regulation of hypertension. Hypertension. 2015;66:309–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Low A, Mak E, Malpetti M, Passamonti L, Nicastro N, Stefaniak JD, et al. In vivo neuroinflammation and cerebral small vessel disease in mild cognitive impairment and alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;92:45–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kierdorf K, Masuda T, Jordao MJC, Prinz M. Macrophages at cns interfaces: Ontogeny and function in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2019;20:547–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Murray EC, Nosalski R, MacRitchie N, Tomaszewski M, Maffia P, Harrison DG, et al. Therapeutic targeting of inflammation in hypertension: From novel mechanisms to translational perspective. Cardiovasc Res. 2021;117:2589–2609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Faraco G, Park L, Zhou P, Luo W, Paul SM, Anrather J, et al. Hypertension enhances abeta-induced neurovascular dysfunction, promotes beta-secretase activity, and leads to amyloidogenic processing of app. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36:241–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Diaz-Ruiz C, Wang J, Ksiezak-Reding H, Ho L, Qian X, Humala N, et al. Role of hypertension in aggravating abeta neuropathology of ad type and tau-mediated motor impairment. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol. 2009;2009:107286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Cao C, Hasegawa Y, Hayashi K, Takemoto Y, Kim-Mitsuyama S. Chronic angiotensin 1–7 infusion prevents angiotensin-ii-induced cognitive dysfunction and skeletal muscle injury in a mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;69:297–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Nyúl-Tóth Á, Tarantini S, Kiss T, Toth P, Galvan V, Tarantini A, et al. Increases in hypertension-induced cerebral microhemorrhages exacerbate gait dysfunction in a mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. Geroscience. 2020;42:1685–1698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Cifuentes D, Poittevin M, Dere E, Broquères-You D, Bonnin P, Benessiano J, et al. Hypertension accelerates the progression of alzheimer-like pathology in a mouse model of the disease. Hypertension. 2015;65:218–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kruyer A, Soplop N, Strickland S, Norris EH. Chronic hypertension leads to neurodegeneration in the tgswdi mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. Hypertension. 2015;66:175–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bueche CZ, Hawkes C, Garz C, Vielhaber S, Attems J, Knight RT, et al. Hypertension drives parenchymal β-amyloid accumulation in the brain parenchyma. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2014;1:124–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Carnevale D, Mascio G, D’Andrea I, Fardella V, Bell RD, Branchi I, et al. Hypertension induces brain β-amyloid accumulation, cognitive impairment, and memory deterioration through activation of receptor for advanced glycation end products in brain vasculature. Hypertension. 2012;60:188–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Gentile MT, Poulet R, Di Pardo A, Cifelli G, Maffei A, Vecchione C, et al. Beta-amyloid deposition in brain is enhanced in mouse models of arterial hypertension. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:222–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Liu J, Liu S, Matsumoto Y, Murakami S, Sugakawa Y, Kami A, et al. Angiotensin type 1a receptor deficiency decreases amyloid β-protein generation and ameliorates brain amyloid pathology. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wang J, Ho L, Chen L, Zhao Z, Zhao W, Qian X, et al. Valsartan lowers brain beta-amyloid protein levels and improves spatial learning in a mouse model of alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3393–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kurata T, Lukic V, Kozuki M, Wada D, Miyazaki K, Morimoto N, et al. Telmisartan reduces progressive accumulation of cellular amyloid beta and phosphorylated tau with inflammatory responses in aged spontaneously hypertensive stroke resistant rat. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:2580–2590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Mawuenyega KG, Sigurdson W, Ovod V, Munsell L, Kasten T, Morris JC, et al. Decreased clearance of cns beta-amyloid in alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2010;330:1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.van Veluw SJ, Hou SS, Calvo-Rodriguez M, Arbel-Ornath M, Snyder AC, Frosch MP, et al. Vasomotion as a driving force for paravascular clearance in the awake mouse brain. Neuron. 2020;105:549–561.e545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Rajna Z, Mattila H, Huotari N, Tuovinen T, Krüger J, Holst SC, et al. Cardiovascular brain impulses in alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2021;144:2214–2226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Deane R, Wu Z, Zlokovic BV. Rage (yin) versus lrp (yang) balance regulates alzheimer amyloid beta-peptide clearance through transport across the blood-brain barrier. Stroke. 2004;35:2628–2631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Deane R, Du Yan S, Submamaryan RK, LaRue B, Jovanovic S, Hogg E, et al. Rage mediates amyloid-beta peptide transport across the blood-brain barrier and accumulation in brain. Nat Med. 2003;9:907–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Fang F, Yu Q, Arancio O, Chen D, Gore SS, Yan SS, et al. Rage mediates aβ accumulation in a mouse model of alzheimer’s disease via modulation of β- and γ-secretase activity. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27:1002–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kook SY, Hong HS, Moon M, Ha CM, Chang S, Mook-Jung I. Aβ₁₋₄₂-rage interaction disrupts tight junctions of the blood-brain barrier via ca2+-calcineurin signaling. J Neurosci. 2012;32:8845–8854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Chen J, Mooldijk SS, Licher S, Waqas K, Ikram MK, Uitterlinden AG, et al. Assessment of advanced glycation end products and receptors and the risk of dementia. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2033012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Petrovitch H, White LR, Izmirilian G, Ross GW, Havlik RJ, Markesbery W, et al. Midlife blood pressure and neuritic plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and brain weight at death: The haas. Honolulu-asia aging study. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:57–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Lane CA, Barnes J, Nicholas JM, Sudre CH, Cash DM, Parker TD, et al. Associations between blood pressure across adulthood and late-life brain structure and pathology in the neuroscience substudy of the 1946 british birth cohort (insight 46): An epidemiological study. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:942–952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Smith EE, Muzikansky A, McCreary CR, Batool S, Viswanathan A, Dickerson BC, et al. Impaired memory is more closely associated with brain beta-amyloid than leukoaraiosis in hypertensive patients with cognitive symptoms. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0191345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Guo T, Landau SM, Jagust WJ. Age, vascular disease, and alzheimer’s disease pathologies in amyloid negative elderly adults. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2021;13:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Nation DA, Edmonds EC, Bangen KJ, Delano-Wood L, Scanlon BK, Han SD, et al. Pulse pressure in relation to tau-mediated neurodegeneration, cerebral amyloidosis, and progression to dementia in very old adults. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:546–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Sible IJ, Nation DA. Visit-to-visit blood pressure variability and csf alzheimer disease biomarkers in cognitively unimpaired and mildly impaired older adults. Neurology. 2022;98:e2446–e2453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Cooper LL, O’Donnell A, Beiser AS, Thibault EG, Sanchez JS, Benjamin EJ, et al. Association of aortic stiffness and pressure pulsatility with global amyloid-β and regional tau burden among Framingham heart study participants without dementia. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79:710–719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Moonga I, Niccolini F, Wilson H, Pagano G, Politis M. Hypertension is associated with worse cognitive function and hippocampal hypometabolism in alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24:1173–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Pajewski NM, Elahi FM, Tamura MK, Hinman JD, Nasrallah IM, Ix JH, et al. Plasma amyloid beta, neurofilament light chain, and total tau in the systolic blood pressure intervention trial (SPRINT). Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18:1472–1483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Wardlaw JM, Smith C, Dichgans M. Mechanisms of sporadic cerebral small vessel disease: Insights from neuroimaging. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:483–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Nam KW, Kwon HM, Jeong HY, Park JH, Kwon H, Jeong SM. Cerebral small vessel disease and stage 1 hypertension defined by the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines. Hypertension. 2019;73:1210–1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Carnevale L, D’Angelosante V, Landolfi A, Grillea G, Selvetella G, Storto M, et al. Brain mri fiber-tracking reveals white matter alterations in hypertensive patients without damage at conventional neuroimaging. Cardiovasc Res. 2018;114:1536–1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Maillard P, Seshadri S, Beiser A, Himali JJ, Au R, Fletcher E, et al. Effects of systolic blood pressure on white-matter integrity in young adults in the framingham heart study: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:1039–1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Carnevale L, Maffei A, Landolfi A, Grillea G, Carnevale D, Lembo G. Brain functional magnetic resonance imaging highlights altered connections and functional networks in patients with hypertension. Hypertension. 2020;76:1480–1490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Jiménez-Balado J, Riba-Llena I, Abril O, Garde E, Penalba A, Ostos E, et al. Cognitive impact of cerebral small vessel disease changes in patients with hypertension. Hypertension. 2019;73:342–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Gons RA, de Laat KF, van Norden AG, van Oudheusden LJ, van Uden IW, Norris DG, et al. Hypertension and cerebral diffusion tensor imaging in small vessel disease. Stroke. 2010;41:2801–2806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Markus HS, Egle M, Croall ID, Sari H, Khan U, Hassan A, et al. Preserve: Randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood pressure control in small vessel disease. Stroke. 2021;52:2484–2493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Shen J, Tozer DJ, Markus HS, Tay J. Network efficiency mediates the relationship between vascular burden and cognitive impairment: A diffusion tensor imaging study in uk biobank. Stroke. 2020;51:1682–1689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Chagnot A, Barnes SR, Montagne A. Magnetic resonance imaging of blood-brain barrier permeability in dementia. Neuroscience. 2021;474:14–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.van Dalen JW, Mutsaerts HJ, Petr J, Caan MW, van Charante EPM, MacIntosh BJ, et al. Longitudinal relation between blood pressure, antihypertensive use and cerebral blood flow, using arterial spin labelling mri. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2021;41:1756–1766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Dai W, Lopez OL, Carmichael OT, Becker JT, Kuller LH, Gach HM. Abnormal regional cerebral blood flow in cognitively normal elderly subjects with hypertension. Stroke. 2008;39:349–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Deverdun J, Akbaraly TN, Charroud C, Abdennour M, Brickman AM, Chemouny S, et al. Mean arterial pressure change associated with cerebral blood flow in healthy older adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;46:49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Waldstein SR, Lefkowitz DM, Siegel EL, Rosenberger WF, Spencer RJ, Tankard CF, et al. Reduced cerebral blood flow in older men with higher levels of blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2010;28:993–998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Beason-Held LL, Moghekar A, Zonderman AB, Kraut MA, Resnick SM. Longitudinal changes in cerebral blood flow in the older hypertensive brain. Stroke. 2007;38:1766–1773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Rodrigues JCL, Strelko G, Warnert EAH, Burchell AE, Neumann S, Ratcliffe LEK, et al. Retrograde blood flow in the internal jugular veins of humans with hypertension may have implications for cerebral arterial blood flow. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:3890–3899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Wilcock D, Jicha G, Blacker D, Albert MS, D’Orazio LM, Elahi FM, et al. Markvcid cerebral small vessel consortium: I. Enrollment, clinical, fluid protocols. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17:704–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Lu H, Kashani AH, Arfanakis K, Caprihan A, DeCarli C, Gold BT, et al. Markvcid cerebral small vessel consortium: Ii. Neuroimaging protocols. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17:716–725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Iturria-Medina Y, Sotero RC, Toussaint PJ, Mateos-Pérez JM, Evans AC. Early role of vascular dysregulation on late-onset alzheimer’s disease based on multifactorial data-driven analysis. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Levine DA, Springer MV, Brodtmann A. Blood pressure and vascular cognitive impairment. Stroke. 2022;53:1104–1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.van Dalen JW, Marcum ZA, Gray SL, Barthold D, Moll van Charante EP, van Gool WA, et al. Association of angiotensin ii-stimulating antihypertensive use and dementia risk: Post hoc analysis of the prediva trial. Neurology. 2021;96:e67–e80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Marcum ZA, Cohen JB, Zhang C, Derington CG, Greene TH, Ghazi L, et al. Association of antihypertensives that stimulate vs inhibit types 2 and 4 angiotensin ii receptors with cognitive impairment. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2145319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Ouk M, Wu CY, Rabin JS, Edwards JD, Ramirez J, Masellis M, et al. Associations between brain amyloid accumulation and the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors versus angiotensin receptor blockers. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;100:22–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Glodzik L, Rusinek H, Kamer A, Pirraglia E, Tsui W, Mosconi L, et al. Effects of vascular risk factors, statins, and antihypertensive drugs on pib deposition in cognitively normal subjects. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2016;2:95–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Scotti L, Bassi L, Soranna D, Verde F, Silani V, Torsello A, et al. Association between renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of dementia: A meta-analysis. Pharmacol Res. 2021;166:105515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Ho JK, Moriarty F, Manly JJ, Larson EB, Evans DA, Rajan KB, et al. Blood-brain barrier crossing renin-angiotensin drugs and cognition in the elderly: A meta-analysis Hypertension. 2021;78:629–643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]